- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Medical Education Systems in China: Development, Status, and Evaluation

Liu, Xihan MD 1 ; Feng, Jie MD 2 ; Liu, Chenmian MD 3 ; Chu, Ran MD 4 ; Lv, Ming MD 5 ; Zhong, Ning MD 6 ; Tang, Yuchun MD 7 ; Li, Li MD 8 ; Song, Kun MD 9

1 X. Liu is a student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

2 J. Feng is a student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

3 C. Liu is a student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

4 R. Chu is a student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

5 M. Lv is director, Department of Education, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

6 N. Zhong is associate professor, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

7 Y. Tang is associate professor, Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, and deputy director, Office of Scientific Research and International Affairs, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

8 L. Li is associate director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China.

9 K. Song is director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 .

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the educational reform and research project of Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University (grant number qlyxjy-201707 and grant number qlyxjy-201880), and the educational reform and research project of Qilu Hospital, Shandong University (grant number 2016QLJY11).

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: All participants provided written informed consent, and the Ethics Committee of Shandong University approved the study (KYLL-202111-072).

The authors have informed the journal that they agree that X. Liu, J. Feng, and C. Liu completed the intellectual and other work typical of the first author.

Correspondence should be addressed to Kun Song, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, 107 Wenhua Xi Rd., Jinan, Shandong 250012, P.R. China; email: [email protected] .

Since 1949, China has made many changes to develop its medical education system and now has a complex array of medical degrees. The current system comprises a 3-year junior college medical program, 5-year medical bachelor’s degree program, “5 + 3” medical master’s degree program, and 8-year medical doctoral degree program; these programs each provide a different path to earning a medical degree. The advantages and drawbacks of such complexity are open to discussion. Since the government set a strategic goal of “Healthy China” in 2019, it has sought to increase the training capacity of its medical education system to establish a high-quality health service system. This article reviews medical education reform in China, discusses the current medical education system, and presents evaluations of medical education programs based on assessments by 1,025 participants (medical students and doctors) recruited from 31 provinces of China. These assessments were compiled via a multicenter self-reported questionnaire administered July 1 to 5, 2021. Participants were training for a medical degree or practicing doctors trained in the 5-year program, “5 + 3” program, 8-year program, or “4 + 4” program. The authors assessed the medical education system to which each of the participants belong and their career stage and career satisfaction, and they requested that participants name the 3 most promising programs. The 8-year program ranked first in work satisfaction (7.92/10), education program satisfaction (7.78/10), and potential (1.91/2). Scores of the 5-year program and “5 + 3” programs were 7.25 and 7.17 for system satisfaction, respectively, and the “4 + 4” program (7.00/10) ranked the next highest. The innovations that have occurred in the Chinese medical education system have offered opportunities to meet the needs of more patients, but the lack of consistency has also posed challenges. Currently, Chinese medical education is becoming more uniform and standardized.

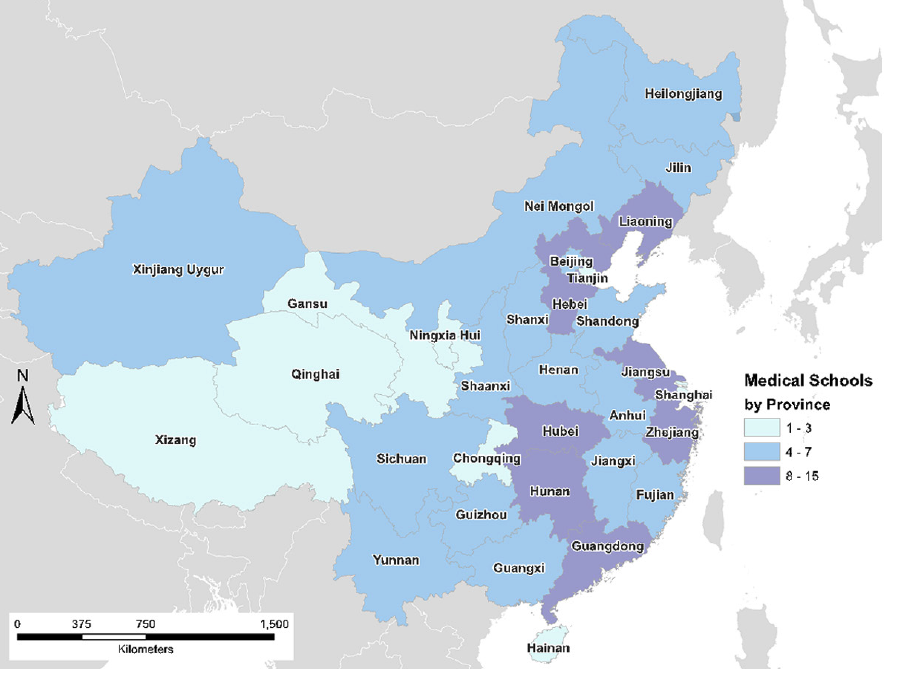

From 1949 to 2020, China invested in modern medical education. When the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, only 22 medical colleges existed, with 3,800 students enrolled per year. 1 By September 2020, this number had increased to more than 200 medical colleges, with approximately 800,000 students enrolled per year. 1

China has great complexity in the levels of programs designed to train doctors. The current system comprises a 3-year junior college medical program, 5-year medical bachelor’s degree program, “5 + 3” medical master’s degree program, and 8-year medical doctoral degree program. These 4 programs were developed in response to the shortage of doctors in China from 1949 to 1976 and the lack of high-level medical talent in the late 1990s, and they have been enabled by technology and economic and social progress. 2

The diversity of the medical education system in China is largely due to historical changes. In the early 1970s, China emphasized enlarging the scale of medical education and shortened the medical education period to meet the increasing demand for health care. 3 , 4 To enhance the quality of medical education in the 21st century, longer-term programs, such as the “5 + 3” and 8-year programs, were implemented to enhance the quality of medical education. 5 In 2018, the Peking Union Medical College launched a “4 + 4” program, allowing talented college graduates from top institutions worldwide and with diverse undergraduate academic backgrounds to pursue medical careers. 6

Multiple programs coexist within the modern Chinese medical education system, but the characteristics, degree of satisfaction, and future development of each program have not been thoroughly evaluated. In this study, we examined the historical development of Chinese medical education, identified the differences and specialties of each medical education program, and conducted a multicenter survey to evaluate the programs. We also considered possible future directions for medical education in China. Specifically, we forecast that a more uniform and standardized medical system unique to China will soon be developed.

Historical Background of the Medical Education System in China

We searched MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, PubMed, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Web of Science, and Wanfang Data, to identify articles published on the historical development of China’s medical education system from inception to December 2020. Additionally, we searched the official websites of colleges and the Chinese Ministry of Education to obtain official information. We used the following search terms and medical subject headings: “Chinese medical education,” “reform,” “changes,” “development,” “junior college medical education,” “5-year program,” “4 + 4,” “5 + 3,” “medical educational system,” and “length of schooling.” Reference formats included research articles, websites, and official files. Subsequently, we reviewed the reference lists of the articles we found to identify and include additional eligible articles.

Reforms in Chinese medical education programs since 1949

The development of modern medical education in China can be divided into 4 stages. The first stage occurred from 1949 to 1966, when the Chinese medical education system was initially established based on the Soviet Union’s medical education system. The second stage (1966 to 1976) was a period of stagnation that saw the abolishment of the college entrance examination system. The third stage (1976 to 2012) was marked by rapid changes in medical education policy, and medical education gradually transformed into multilevel and multispecialty areas of practice. The fourth stage (2012 to the present) is characterized by a focus on high-quality medical education. 4 Figure 1 shows the major events and policy changes over this timespan.

Before 1949, the Chinese medical education system was based on the 3-level degree system. 7 Starting in 1949, the Chinese government implemented reforms to build a new medical education system. 8 In 1952, public medical colleges were established and assumed the task of cultivating medical students. At this time, medical education mainly comprised intermediate and higher training conducted by secondary medical schools and universities. 9 College students earned a medical degree in 5 years by completing 3 years of basic science, 1 year of clinical teaching, and 1 year of practice. 4 Graduates could enter clinical practice directly after completing their education. However, this extensive course of education led to an extreme shortage of medical personnel. From 1953 to 1957, the country had 25,918 medical graduates while its population was more than 614 million. 1

In 1966, to cultivate more doctors to meet the country’s rising health care needs, the Ministry of Education shortened the length of medical education from 5 years to 3 years. 10 , 11 Around this same time period, the Ministry of Health also shifted the focus of medical care to the countryside, which spawned a rural doctor system that lasted from 1965 to 1975. 12 The aim of the rural doctor system was to produce a large number of workers with medical knowledge to provide preventive health care and treat basic health problems. Rural doctors were trained to play an essential role in providing basic care to the rural population; however, their training was brief and very limited. 12 , 13

After 1976, China again refocused its medical education system, and in 1981, the country began to standardize medical degrees. The Ministry of Education promulgated the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Academic Degree” and established a 3-level medical degree system: bachelor, master, and doctor of medicine (MD). 14 In this 3-level system, students must earn a previous degree to apply for a higher degree. For example, a medical doctoral student must complete 5 years of undergraduate study for a bachelor’s degree and 3 years for a master’s degree before proceeding to 4 years of doctoral study. After 1988, some schools were allowed to admit long-term medical students and get higher degrees directly; for example, in these schools, 8-year medical students can earn a doctorate without a master’s degree.

In 1988, 15 schools were approved to conduct the 7-year program that awarded a master’s degree in medicine. In 2001, the Ministry of Education stated that medical education should gradually expand the scale. 15 In the same year, the Peking Union Medical College began to recruit students for the 8-year MD degree. In 2004, the Ministry of Education officially approved 9 universities to award the MD degree. 16

The number of medical university graduates increased rapidly, especially once university enrollment expanded in 1999. To standardize medical services, in the same year, China formally passed the Law on Medical Practitioners and established national medical licensing examination (NMLE) systems. 17

In 2010, the International Medical Education Expert Committee called for a third medical education reform to meet the global health requirements, 18 and in 2012, the Ministry of Health proposed the “Excellent Doctor Education and Training Program.” 19 This reform focused on improving the quality of doctors graduating from Chinese universities and cultivating humanistic clinicians capable of conducting scientific research. In 2014, China formally established a national standard residency training system. 20 Chinese doctors were required at minimum to obtain a medical degree, pass the medical practitioner qualification examination, and finish standardized residency training. 21 In 2015, the “5 + 3” integrated training model completely replaced the prior 7-year master’s level medical degree. 22 The new model allows graduates to obtain a medical master’s degree and certificate of standardized residency training. At present, postgraduate education in China includes standardized residency, general practitioner training, and specialist training. 23

Description of different medical education programs in China

Table 1 provides an overview of different medical education programs that have been offered in China since 1949. The major medical training program in China today is the 5-year bachelor’s degree program, with 132 colleges offered this program in 2021. Figure 2 provides a comparison of the various cycles for cultivating doctors in China.

Medical education in junior colleges.

Junior colleges train practical medical professionals for primary medical services; they include secondary technical schools and junior medical colleges. Generally, the length of schooling is 3 years. In 2012, the government introduced a “3 + 2” program, which comprises the 3-year junior college medical education plus a 2-year general practitioner training. 19 Junior college medical education has a lower entry threshold and shorter training period compared with other medical education programs. This program has trained many clinicians for primary health care and heavily contributes to China’s primary medical services.

The 5-year medical education program.

The 5-year clinical medical major program is the basis of clinical medicine education. It is designed to produce qualified practicing doctors. 8 The training plan includes basic and clinical medicine courses and internships. Graduates can take the NMLE 1 year after participating in clinical work at medical institutions, and they need to complete 3 years of standardized residency training to become doctors.

With the increase in the number of 5-year medical education graduates, the requirements for working in top-ranked hospitals have become more stringent. An increasing number of undergraduates continue their studies to earn a master’s or doctoral degree for better employment opportunities. 24

The “5 + 3” medical education program.

The “5 + 3” model is designed for training high-level clinicians. 25 It combines the 5-year medical undergraduate education, 3-year standardized residency training, and postgraduate education. Qualified graduates obtain a certificate of standardized residency training and a professional master’s degree. 22 Compared with other medical students, the greatest advantage for students in this program is their ability to simultaneously participate in standardized residency training and postgraduate education.

The 8-year medical education program.

To date, 14 colleges have qualified for the 8-year medical education program in China. 16 This program aims to equip students with a humanistic spirit, extensive social and natural science knowledge, solid medical knowledge, and clinical practice skills.

The training program varies but mainly includes basic science and medical education together with scientific research training. After graduation, most students obtain an MD degree. Peking University awards a small number of excellent graduates with MD and Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degrees. 26

Recent practice in medical education in China.

Medical education in China is becoming internationalized. The Ministry of Education pushed forward a reform of integrative-curriculum education, applied new teaching methods, such as problem-based learning, and implemented the “4 + 4” and 9-year programs.

The “4 + 4” medical education program has emerged in China in recent years. 6 Only 3 universities have adopted this program, which provides training to meet the public’s increasingly high expectations for health care services. 5 The students selected for this program are talented college graduates with multidisciplinary academic backgrounds from top institutions worldwide. Students need to complete the medical curriculum, internships, and doctoral dissertations within 4 years. Those who fail the exam are transferred to a PhD or Master of Science training program. 27

In 2019, Nanjing Medical University established a 9-year medical education program. In this model, undergraduate, graduate, doctoral education, and standardized residency training are integrated and completed within 9 years total. 28 Graduates earn an MD degree and can become qualified doctors instantly after graduation. 28 It offers the shortest cycle from start to finish among all the medical education programs.

Evaluation of Medical Education Programs in China

To learn more about today’s medical education system in China, we invited 1,025 medical students, residents, and doctors who had joined a medical education program in 79 hospitals in 31 provinces of China to participate in a self-administered questionnaire survey that took 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Participation was limited to individuals who had trained in Western medicine curriculum.

We contacted directors of hospital education departments to assist in recruiting participants and in coordinating meetings to complete questionnaires onsite. All 1,025 questionnaires were completed and collected, and the completed questionnaires were then input into our computer system for analysis.

We collected basic information for all 1,025 participants, including age, graduate school, medical program, affiliation, highest educational attainment, and current career stage. We measured job satisfaction and program satisfaction using a scoring system that ranged from 0 to 10 and calculated each program’s average score. We requested participants choose the 3 programs with the most potential, and we calculated the average weighted scores. All statistical computations were performed using the online Questionnaire Star application ( https://www.wjx.cn ). All participants provided written informed consent, and the Ethics Committee of Shandong University approved the study. Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 displays information about the questionnaire used in this study.

Of the 1,025 total respondents, 578 (56.39%) were from universities and hospitals in the Shandong province. The rest were from Jilin (68, 6.63%), Beijing (61, 5.95%), Chongqing (54, 5.27%), and others (264, 25.76%), including 31 provinces of China (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ).

Participants were uniformly distributed by career stages. The total number of students was 380 (37.07%), comprising 101 (9.9%) undergraduates, 181 (17.66%) standardized resident trainees pursuing a master’s degree, 85 (8.29%) students pursuing a doctor’s degree, and 13 (1.27%) students pursuing a postdoctoral degree. The total number of doctors was 645 (62.93%), comprising 166 (16.20%) attending doctors, 213 (20.78%) associate (deputy) chief doctors, and 266 (25.95%) chief doctors (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ). Of the 1,025 total participants, 809 (78.93%) attended a 5-year program, 166 (16.20%) completed the “5 + 3” program, 40 (3.90%) completed the 8-year program, and 10 (0.98%) attended the “4 + 4” program (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ).

When asked about the program with the highest development potential, most of the 1.025 participants chose the 8-year program. This program received the highest average weighted score of 1.91, followed by the “5 + 3” program, with a score of 1.87. The 5-year programs and “4 + 4” program scored 0.86 and 0.76, respectively (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 5 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ). We requested participants to rate their career and system satisfaction on a scale of 0 to 10. Participants of the 8-year and “4 + 4” programs gave nearly equal marks in career satisfaction, with average scores of 7.92 and 7.9, respectively. The “5 + 3” program obtained the lowest average score of 7.25 in career satisfaction (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 6 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ). As for the most satisfying medical education program in China, the 8-year program obtained the highest average score of 7.78, followed by the 5-year (7.25), “5 + 3” (7.17), and “4 + 4” (7.00) programs (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 7 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ).

A correlation analysis of the results revealed that students with a doctorate degree and chief doctors had generally high career satisfaction scores, averaging 7.65 and 8.24, respectively. However, postdoctors (doctors with a PhD degree who are pursuing postdoctoral training) had the lowest career satisfaction score (6.62), possibly because of the long medical schooling cycle they have to go through (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 8 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ).

Next, we discovered that the 5-year program cultivated the most chief doctors. This result may be affected by bias because the 5-year program is the oldest (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 9 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ). Finally, participants were asked to make suggestions for improving the current Chinese medical education system. In all, 316 participants made a suggestion; the most frequent suggestions were increasing clinical practice hours (n = 57), unifying the length of schooling (n = 34), developing individualized teaching (n = 23), and strengthening scientific and humanities education (n = 22; see Supplemental Digital Appendix 10 at https://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B323 ).

The Chinese medical education system is complex and diverse. Assessing these various education programs could help in addressing their shortcomings and in developing a more mature and effective system for training doctors.

The 8-year program aims to develop the scientific thinking and clinical skills of students to help them become medical scientists and physicians. As our study showed, many medical students in China consider this program the most promising path to becoming a doctor. However, the students enrolled in this program generally have a shorter time (3-year course) to obtain a doctorate degree compared with students in the normal MD–PhD programs who must complete a 3-year master’s course and 4-year doctoral course. The shorter duration of the 8-year program is problematic as students may not obtain sufficient scientific and clinical training compared with those studying for an MD or PhD degree.

The “5 + 3” program is another newly founded long-duration system. Students of this program participate in 3-year standardized residency training while pursuing a Master of Medicine degree. However, as these students do not receive integrated scientific training during heavy clinical work, they generally do not develop competitive scientific capacity in the working environment unless they continue with further studies. 29 Moreover, the 3-year residency in college hospitals restricts them from obtaining educational opportunities in medical schools of better quality. 30 This could be the reason that the students report relatively low system and career satisfaction for this program.

The 5-year program is a part of the traditional Chinese medical education system. Of the 1,025 participants in our survey, 809 graduated from the 5-year program. Of the 266 who were chief doctors, 253 graduated from the 5-year program (95.11%), and of the 213 associate (deputy) chief doctors, 176 graduated from the 5-year program (82.63%)—indicating that this program has cultivated many medical talents. 6

The “4 + 4” program was recently launched and closely matches the current international medical education system. As annual enrollment in this program is still quite low, we can only predict the program’s future. Students in the “4 + 4” program are cultivated to have a wider range of knowledge and interdisciplinary thinking, which could confer graduates from this program with unique advantages. This program holds important development potential for the future of Chinese medicine.

Our study to assess the development and current status of China’s medical education programs had some limitations. First, the number of medical students from each program differed based on the launch date of the different programs. Most study participants were from the more established 5-year and 8-year programs, and there were fewer respondents from the more recently established “4 + 4” program. Second, our study findings were based on the participants’ subjective evaluation, not objective indicators. Various work environments, age, education, and job experiences may have influenced the respondents’ opinions.

In conclusion, the development of medical education in China can be summarized by 5 major milestones: construction of the “5 + 3” program, exploration of the “3 + 2” training mode of rural medical program, promulgation of the clinical medicine professional certification system, in-depth training of health personnel in the “5 + 3” program, and the recent launch of the “4 + 4” program. 31 , 32

The innovations occurring in the medical education system in China offer opportunities and pose challenges. Training programs are designed to be both student-centered and competency-oriented. They integrate interdisciplinary learning methods to develop independent thinkers with a professional spirit. We believe that the current work happening in medical education in China will eventually lead to a system that effectively develops doctors who are well-trained and prepared to meet the needs of their patients.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Editage ( www.editage.com ) for English-language editing.

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

References cited in Table 1 only

Supplemental digital content.

- ACADMED_2022_08_02_SONG_AcadMed-D-21-02263_SDC1.pdf; [PDF] (514 KB)

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

A call to improve health by achieving the learning health care system, trends in nih funding to medical schools in 2011 and 2020, easing the transition from undergraduate to graduate medical education, blue skies with clouds: envisioning the future ideal state and identifying..., the undergraduate to graduate medical education transition as a systems....

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.12(6); 2020 Dec

Medical Education Reform in China: The Shanghai Medical Training Model

Jialin c. zheng.

Professor and Dean, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Professor, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, Nebraska Medical Center

MD graduate, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

PhD graduate, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Zenghan Tong

PhD graduate, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, and Member of Asia Pacific Rim Development Program, University of Nebraska Medical Center

MD graduate, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Matthew S. Mitchell

Member of Asia Pacific Rim Development Program, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Xiaoting Sun

PhD graduate, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Yuhong Yang

MD graduate, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Professor and Director, Scientific Research and Education Division, Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, Shanghai, China

Secretary, Scientific Research and Education Division, Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, Shanghai, China

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Former Dean, The Alpert Medical School, Brown University

In China, a growing and aging population has challenged the health care system. It is expected that China's population over 65 years old will reach 487 million, or nearly 35% of inhabitants, in 2050. 1 The burden on the health care system will be exacerbated by difficulty in accessing medical resources, especially in rural areas. The training of physicians who are qualified, respected, and trusted to serve in rural and urban communities must be increased to meet this need.

The concept of graduate medical education is relatively new in China. Traditionally, medical school graduates work directly as junior physicians without residency training after finishing medical school. With theoretical knowledge and clinical clerkships obtained in medical school, junior physicians' practical skills and knowledge were gradually acquired through an apprenticeship model, learning from senior physicians in the same department over an indefinite number of years. The training experience is variable in terms of length and quality, as there is no standardization or oversight.

This inconsistency has led to a devaluation of physicians practicing in the community, away from teaching hospitals. Many patients prefer to be treated in tertiary centers as the physicians there learned from the experts. 2 Patients may self-refer to specialists or physicians with more experience, resulting in an overloading of tertiary hospitals and underutilization of physicians practicing in community and rural areas. Given this social stigma, early career physicians tend to choose tertiary hospitals at the start of their medical career and are reluctant to work in community health care centers or regional hospitals, because they have insufficient social recognition and resources. 3 , 4 Thus, reform in health care service delivery, particularly in the medical education system, is warranted to cultivate more primary care physicians and community-based and rural providers through standardized medical training. 5 These reforms would need to incorporate improved standardization and quality while being timely and cost-effective to encourage institutional implementation and student recruitment.

In 2009, the Chinese government launched a national health care reform policy, of which medical education reform is a key part. 6 In 2010, Shanghai was chosen to be the pilot city for the national reform because it had relatively mature medical and educational resources. Several local health and education departments united and formed a special health reform leadership group to formulate plans and supervise the implementation. Shanghai's reform aims to create a better physician training system, enhance professional prestige, and promote a more harmonious medical care environment with better physician-patient relationships and improved learning environments for trainees. The 2 pillars of Shanghai's medical education reform are standardized residency training and standardized specialist training, with the aim of cultivating medical personnel of homogenized quality and high-level standards through a well-functioning postgraduate medical education system. There are 5 essential parts to Shanghai's health care reform: the “5+3+3” model (5-year bachelor's degree in medical school, plus 3-year residency training, plus 3-year specialty training), a standardized residency training, a primary care system, a health information project, and vertical integration of medical resources. 7 , 8 After graduation from the standardized residency training (SRT), trainees obtain a certificate that is recognized throughout the country, indicating that they have completed residency training and can be recruited by health care institutes of different levels all over the nation as registered physicians. In this article, we describe the 5+3+3 model and its potential for dissemination throughout China's medical education system.

Current Status of Medical Education in China

After graduation from high school, all students intending to continue their education take a national college entrance examination. It is a general examination for all majors and universities, not specific to medical school. The results of this examination largely determine which school and program students attend after high school. 9

Currently, medical education in China is highly heterogeneous, including 5-year, 6-year, 7-year, and 8-year medical education programs. Different medical schools nationwide have adopted variable curricula and distinct continuing medical education paradigms ( Table ). These various systems have been based on medical education principles from the former Soviet Union and Britain. With various instructional methods and standards to evaluate the competency of the trainees, it is likely these programs would lead to discrepancies in the quality of training.

Current Medical Education Programs in China

| 5-year | Bachelor of Medicine | > 300 medical schools and universities | Graduates typically work in hospitals either as primary care providers or specialists (after further training) |

| 6-year | Bachelor of Medicine | Replaced by the 7-year program | 5-year program + 1 year of foreign language curriculum |

| 7-year | Master of Medicine | 42 universities | All enrollment stopped since 2015, replaced by the “5+3” combined program |

| 8-year MD | MD/Doctor of Medicine | 15 universities | 1 year of basic college education, 4 years of preclinical and clinical medical education, and 3 years of clinical skill training in a hospital setting |

| “5+3” combined | Master of Medicine | > 300 medical schools and universities | 5-year program + 3 years of combined standardized residency training and mastery curriculum |

New Medical Education System in Shanghai

In order to meet the national goal of “Health China 2030,” China has urgently called for a reform of the primary and continuing medical educational training systems. In the United States, the model of 4 years of medical school plus a standardized length of time for each specialty's training is well-established, evidence-based, and has been adopted nationwide. 11 However, this system cannot be copied mechanically in China. The cost of a general college education before medical school could be a major financial burden for most students from lower- or middle-income families. This, in addition to the generally lower compensation for physicians in China compared with that in the United States, would be a strong disincentive for pursuing an MD training. Furthermore, China's large aging population and its urgent shortage of qualified physicians make the lengthy US model of medical education largely impractical.

To mitigate these problems, Shanghai has attempted to implement a standardized residency program aiming at training highly qualified physicians, diminishing public distrust, 3 and more importantly, improving the accessibility and affordability of medical services. Shanghai City introduced a new medical education program in 2010, 8 which includes the broad 5-year undergraduate medical education, a 3-year SRT program, and a 3-year specialized training program, also referred to as the 5+3+3 model program. Figure 1 illustrates the differences between the physician training system in the United States and the Shanghai model.

Physician Training System in the United States (a) and Under the Shanghai Model (b)

Phase 1: Standardized 5-Year Medical School Training

The degree granted after this 5-year program is Bachelor of Medicine. In the first 2 years, students study humanities, medical ethics, basic science, and basic medical courses such as medical history, biochemistry, anatomy, immunology, and physiology. In the next 2 years, students take clinical courses in specialties, including surgery, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, family medicine, emergency medicine, and traditional Chinese medicine. During these 4 years, students take several nationally standardized assessments to determine their progress. In their fifth year, students complete a 1-year clinical rotation, followed by a 2-part final examination that evaluates basic clinical knowledge and clinical skills. Graduates must then take a national medical licensing examination before they can apply for a medical license.

Phase 2: Standardized Residency Training Program

Phase 2 of the 5+3+3 model builds on the existing model for residency training in Shanghai. In 1988, various specialties and institutions began to train residents as hospital employees. In 2000, Shanghai started to standardize the program and widely implemented it in 2006. In 2009, after the national health care reform, Shanghai piloted the SRT program in tertiary hospitals, where all graduates received a standardized training program before employment. The training criteria in different tertiary hospitals were gradually established and standardized. 12

Medical school graduates holding Bachelor of Medicine, Master of Medicine (basic science), and PhD degrees who desire to become practicing physicians are required to apply for one of these 3-year programs in qualified educational hospitals (the 64 authorized teaching hospitals in the city as of 2018).

The SRT program comprises 5 specialties: surgery, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and family medicine, each with standardized rotation schedules. Residents choose one to train in and are assessed throughout their training by annual evaluations and comprehensive examinations, including an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). After residency, the National Qualification Examination for Doctors is mandatory for trainees to be registered as a physician at their practicing institution. 13

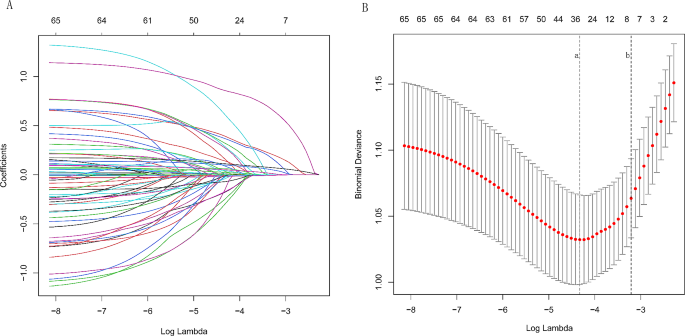

Our survey in collaboration with the Research and Education Division of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission found that in 2011, 1 year after the implementation of the SRT program, only 100 trainees had completed the program. By 2018, there were 14 597 trainees who had completed the program and acquired a certification. In a 2014 survey of the Shanghai SRT program recruitment, the number of residents enrolled in the SRT program increased from 1841 in 2010 to 3400 in 2017. Graduates with a masters' or doctorate degrees accounted for more than half of the new residents.

The SRT program is gaining momentum. By 2018, 23 318 trainees had been recruited into the Shanghai SRT program, along with the 14 597 trainees who had successfully completed the program ( Figure 2 ).

Recruitment and Student Background of Standardized Residency Training in Shanghai (2010–2018)

Phase 3: Further Training

In order to acquire the SRT certification, trainees need to pass the National Medical Licensing Examination and SRT completion examination, which are both nationally standardized. Therefore, after the SRT program, trainees are well qualified to provide safe care to most patients in their specialty and understand when to transfer them for subspecialty care, especially if practicing in areas with less consulting physician support or resources. However, in the Shanghai model, the post-residency medical education programs include the Standardized Specialty Training (SST) and PhD programs.

In January 2016, the Ministry of Health announced plans to initiate a pilot SST program. In this program, participants can pursue 2 to 4 years of training in any specialty after completion of the SRT program. Those who complete the SST program will receive a Doctor of Medicine degree, a demonstration of the holder's knowledge and skill in clinical medicine, which is equivalent to a doctorate degree in other subjects. 4 , 14 However, this program has received complaints from medical students and junior doctors in China for fear of the lengthy process and limited compensation during SST.

Next Steps and Remaining Challenges

The continuing educational programs of the 5+3+3 model will gradually standardize the medical education and professional training for qualified physicians and physician-scientists in China. This is a breakthrough for Chinese medical care and brings a promising future to China's overburdened medical care system. Shanghai's reform has already led to a remodeling of the medical education system in China. In early 2014, the National Health and Family Planning Commission of China issued “Guiding Opinions on Establishing a Nationwide Standardized Resident Training System,” which proposes that by 2015, all provinces and regions will initiate SRT, and by 2020, all newly graduated clinicians with a bachelor's degree or above should receive SRT before practicing in medical facilities.

Nevertheless, there are challenges during the national adoption of this new educational system. Not every hospital likely has enough faculties to support the educational program. Since teaching hospitals in China are generally burdened with high outpatient and inpatient volumes, it is difficult for faculty to deliver effective teaching to residents, especially when there is not a good incentive mechanism in place. Residents in some of the leading programs reported issues such as variations in teaching quality and insufficient supervision. 15 , 16 Currently, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education in China design and evaluate the curricula, which undergoes continual improvement. For example, an investigation on internal medicine programs found that case discussions most often occurred only once a week or less, which is likely too infrequent to provide an environment conducive to learning. 17

Since a sophisticated competency framework to guide resident education is currently lacking in the Chinese graduate medical education system, 18 it is essential to set up a nationwide standardized evaluation system with the involvement of third-party institutes, such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–International (ACGME-I). The ACGME's 6 core competencies and their associated subcompetencies are useful guiding tools in terms of building and evaluating the full scope of a physician's practice of medicine. As of late 2018, Tongji University School of Medicine (TJSM) had started the process of ACGME-I accreditation in its affiliated hospitals, the first to introduce this accreditation system in mainland China. The aim of this campaign is to apply the well-recognized criteria to the Shanghai SRT program to make it more rigorous and comparable to its counterparts elsewhere. 19 Moreover, with the ongoing efforts and progress made via undergraduate curriculum reconstruction and residency training standardization (including ACGME-I accreditation), TJSM is also trying to promote a new “5+3” program of training high-quality primary care providers, which grants them with an MD degree without having to complete the SST component of the model. Together with the societal efforts of raising the prestige of the profession and financial compensation for young physicians, these solutions are aimed to optimize training length and quality, and hopefully therefore the attractiveness of and recruitment into the profession.

Conclusions

Despite challenges, Shanghai's 5+3+3 system has thus far shown promise in solving some of China's most urgent health care needs via a reformulated training model. A more reliable accreditation and oversight from an outside agency with international criteria is crucial for the persistence of the system's quality and its spread to other areas of the country.

The authors would like to thank Hong Huang, Xiaochu Shen, Jianguang Xu, and Tiefeng Xu from Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning; Gang Pei from Tongji University; and Gang Huang from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for suggestions and support. They would also like to thank Lenal Bottoms and Jaclyn Ostronic for providing outstanding administrative support.

Contributor Information

Jialin C. Zheng, Professor and Dean, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. Professor, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, Nebraska Medical Center.

Han Zhang, MD graduate, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China.

Beiqing Wu, PhD graduate, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Zenghan Tong, PhD graduate, Department of Pharmacology & Experimental Neuroscience, and Member of Asia Pacific Rim Development Program, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Yingbo Zhu, MD graduate, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Matthew S. Mitchell, Member of Asia Pacific Rim Development Program, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Xiaoting Sun, PhD graduate, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Yuhong Yang, MD graduate, University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Kan Zhang, Professor and Director, Scientific Research and Education Division, Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, Shanghai, China.

Lv Fang, Secretary, Scientific Research and Education Division, Shanghai Municipal Health Commission, Shanghai, China.

Eli Adashi, Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Former Dean, The Alpert Medical School, Brown University.

News from Brown

Chinese medical education rising unevenly from cultural revolution rubble.

A new research review chronicling the history and current state of medical education in China finds that the country’s quest to build up a medical education system to serve its massive population has produced a rapid, if uneven, result.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — For scores of years after the first medical school opened in China in 1886, the country progressed in building a medical education system for its fast-growing population. Then 50 years ago, it not only came to a screeching halt, but to a full reversal with the Cultural Revolution.

“Indeed, throughout the decade in question (1966 to 1976), all extant medical schools were effectively shuttered and their faculty disbanded,” write the authors of a new paper describing the history and current status of China’s medical education system. “It was only in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and the passing of Chairman Mao Zedong in 1976 that the medical education enterprise embarked on a slow recovery process during which some of the schools affected were allowed to reopen.”

Since then, the pace has quickened considerably to the point where the country has more than 2.1 million practicing physicians and more than 167 civilian medical schools enrolling about 64,000 students. The restoration of a large national system for undergraduate medical education in just 40 years is remarkable, said study corresponding author Dr. Eli Adashi, former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University.

“They had to go from 0 to 60 in three seconds,” said Adashi, who has visited China many times since 2008, often to study and to advise colleagues within the system. “They had to cover a lot of ground, and since they are trying to catch up to the rest of the world, they had to go about it fairly quickly. For the hardships and difficulties and hugeness that characterizes China, they’ve done pretty well on the medical school part.”

In addition to Adashi, the authors of the paper in the American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics and Gynecology are Dr. Nan Du, a graduate of Brown University’s Alpert Medical School now at Yale, and Dr. Huanling Zhang of Fudan University in Shanghai.

Peculiar paths

Despite China’s overall progress, two overarching peculiarities remain in the system by which China’s Ministry of Education produces its physicians, Adashi said. One is the complex diversity of paths an aspiring doctor can follow to gain medical training and become a practicing doctor. The other, which Adashi said is a more serious concern, is a near-complete lack of standardized residency programs, or graduate medical education.

Chinese students can follow many paths to becoming a doctor, including curricula lasting three, five, seven or eight years. As in most places around the world (except the U.S.) enrollment in a medical education program occurs in lieu of obtaining a four-year non-medical undergraduate college education.

Instead, the vast majority of Chinese medical students (about 58,000) attend a five-year program after high school to earn a bachelor’s degree. Then they serve in a one-year clinical internship before taking the nation’s standardized medical licensure exams, which measure both knowledge and clinical skills. Upon passage, they can register as medical practitioners.

Those who pursue the more elite seven- or eight-year curricula gain additional training and research experience and earn more prestigious degrees (master’s or doctorate respectively), before taking the same licensure exams as their bachelor’s degree-earning colleagues.

Though the varied tracks offer differing levels of rigor in the classroom, Adashi said the consistency of the licensing exam requirements ensures a baseline of training and competency across the profession.

“If everybody takes the same licensing examination, I think it really doesn’t matter if you do it in eight years, or seven years or five years,” Adashi said. “If you have an equating national benchmark that allows you to compare students from anywhere in the country then you are in reasonably good shape.”

In addition, China appears to be working toward winnowing the number of different paths into the profession, Adashi said. The seven-year programs have been left out of several recent ministry reports on the future of medical education.

Residency difficulties

Where China’s medical education system urgently needs more development, Adashi said, is in creating residency programs like those pioneered in, and required in, the U.S. Residency, after all, is where newly credentialed doctors grow into truly experienced hospital physicians by way of the structured evaluation and guidance of seasoned supervising doctors.

“It’s essential to the patient to know that the doctors who are training, for instance to do surgical procedures, are carefully supervised, their progression is monitored, they take exams to prove their competence, and they acquire graduated responsibilities as they proceed,” Adashi said.

After many false starts over decades, China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission has recently defined requirements of between one and three years of graduate medical education, depending on undergraduate training and desired specialty. But the standards of evaluation vary widely by region, Adashi and his co-authors wrote. Adashi said they do not yet amount to a rigorous, nationally reliable standard.

“Their residency program is their challenge,” Adashi said. “It is unstructured and non-uniform. It is everything you don’t want it to be.”

China is clearly keen to continue building a robust residency system for its aging population of 1.4 billion, Adashi said.

“They understand the importance,” Adashi said, “but they have barely gotten underway.”

- Doctors and Medical Education in China

Doctors are one of the most respected professions in the world. They use their extensive knowledge in the field of medicine to assist and improve patients' well-being and improve health-care facilities. Together with other medical practitioners, they are heroes in fighting against diseases especially during a pandemic like Covid-19. Doctors across the world continue to work hard to contain the spread of the new coronavirus.

Since the outbreak began in Wuhan, Hubei Province in China, in December 2019, more than 40,000 medical practitioners came together from every corner of China to help Hubei. They worked around the clock to battle the coronavirus outbreak and finally bringing the epidemic under control. There were more than 3000 medical practitioners infected with some, sadly, succumbing to the virus.

To cope with the increasing health-care demand, the Chinese government launched the “Excellent Doctor Training Program” in 2012 aiming to train more doctors for the next 10 years. Most medical schools in China offer courses in English, where foreign nationals are welcome to China for higher education. Today, you will find many international students studying medicine in China.

The Typical Process to Become a Doctor in China

To pursue a career as a doctor has become a very competitive and comprehensive process. The number of years and steps involved will depend on the course and specialty you choose to pursue.

To become a doctor in China, a student must pass the standardized national exams in high school, complete seven years (or eight years for two medical schools) of medical studies, and undergo an internship. Students undertake basic science, liberal arts, and clinical science courses in the program. The program also requires mandatory hours of volunteer work.

Medical students spend the first two years of their typical seven-year program studying liberal arts and basic science courses. Medical schools compress clinical science courses into a two-year program that spans the third and fourth years of study. After that, students must undertake compulsory hours of internship. The duration of the internship differs across different universities. However, students must complete an internship and a clerkship before they graduate their seventh year.

When is Chinese Doctors' Day?

19th of August is designated the observance of Doctor’s Day in China, which marks the significance of doctors in safeguarding people's health. Doctor's Day was first celebrated on August 19, 2018.

What Is a “Barefoot Doctor” ?

“Barefoot doctors” first existed in China during the Cultural Revolution(1966-1976). The farmers who received training worked in their rural villages to bring basic health-care to areas in which urban-trained doctors would not settle. They promote basic preventive health-care, family planning, and treat common illnesses. The name "Barefoot doctor" originates from southern farmers, who would often work barefoot in the rice paddies.

Barefoot doctors act as primary health-care providers at the grass-roots level. Often, they grow their herbal medicine in their backyard. They often spend 50% of their time farming, and as a result, rural farmers perceived them as peers and respect their advice. They were also integrated into a system where they can refer seriously ill patients to the township and county hospitals.

The Pantheon of Modern Medicine in China

1. dr. wu lien-teh - the father of modern medicine in china.

Dr. Wu Lien-Teh was born in Penang in 1879. He was the first of Chinese descent to graduate as a medical doctor from the University of Cambridge.

Dr. Wu was a physician renowned for his work in public health and particularly, as the 'Plague Fighter' who stamped out the Northeastern China plague of 1910–11. He was also the first Malayan and the first Chinese-heritage person nominated to receive the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1935.

In 1915, the National Medical Association was formed to promote western medicine in China. Wu was elected Secretary in 1915, and President in 1916–1920.

In 1930, the Chinese government created the National Quarantine Service (NQS) and appointed Wu as its first director. Headquartered in Shanghai and staffed by Chinese personnel, NQS enabled the Chinese government to regain quarantine control of all major ports in China.

His other claim to fame is as the inventor of the Wu mask, the precursor of today's N95 mask.

Source: http://drwulienteh.com/

2. Dr. Qiu Fazu-The Father of Modern Surgery in China

Qiu Fazu was born in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, in December 1914. He studied medicine as his mother had died after maltreatment of appendicitis. After his finals at the German School of Medicine in Shanghai, he went to Munich after gaining a Humboldt scholarship, graduating from the medical faculty, and receiving a German MD in 1939.

Back in China, Qiu introduced modern surgical techniques, and with his experience from Germany helped in establishing medical schools. Promoting the development of abdominal and general surgery, he is considered a surgical pioneer and the main founder of organ transplantation surgery in China. In the 1970s he began the earliest research program on liver transplantation—from experimental study to clinical treatment—founding the first institute of organ transplantation in China.

Qiu Fazu was the first Asian to receive the highest German honor, the Federal Cross of Merit, in 1985.

3. Dr. HuangJiasi -Pioneer of the Chinese Thoracic Surgery

Graduated from the Peking Union Medical College, Huang became the leading thoracic surgery specialist and medical educationalist in China. Huang went to the University of Michigan Medical School in 1941, where he was instructed by Dr. John Alexander (Michigan’s first Director of Thoracic Surgery). Huang graduated from the school with a Master of Surgery Degree in 1943. Huang returned to China in 1945 and became a Professor at the Shanghai Medical College. During his position in Shanghai, Huang helped founded the Shanghai Chest Hospital and served as the first Dean of the Hospital. After his appointment, Huang moved to Beijing, where he became President of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and President of the Peking Union Medical College from 1958 to 1983. Huang’s endeavor in his career as a medical practitioner and educator helped China through the development of Thoracic Science and produced a significant number of thoracic surgeons for the country.

4. Dr. WuJieping- Pioneer of Urology in China

Born in January 1917 in Changzhou, Jiangsu, Wu studied medicine after his father said that an intellectual should strive to be either a good prime minister or an excellent doctor. Wu earned his Ph.D. in 1942 from the Peking Union Medical College, a world-class medical school at the time. He then worked at the Zhonghe Hospital before heading off to further his skills in urology at the University of Chicago in 1947. In the United States, he was instructed by Professor Charles Brenton Huggins, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1966. Wu was also the first person on the mainland to carry out kidney transplant surgery.

5. Dr. Wu Mengchao-Father of Chinese Hepatobiliary Surgery

Wu was born in Minqing County, Fujian, in southern China, and spent a few years in East Malaysia where his father worked, returning to China for education in 1940. Wu graduated from the School of Medicine of Tongji University in July 1949 and was elected the academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1991.

During his 50 years as a hepatic surgeon, Wu has performed surgery almost every day. Until June 2011, Wu had performed over 14,000 hepatic surgeries, including more than 9,300 liver tumor resections. His success rate stood at 98.5 percent. Wu maintained a steady record of more than 200 surgeries each year.

Wu was given the honor of "Leading Medical Expert" by the Central Military Commission in 1996 and was presented the 2005 National Science and Technology Award in 2006.

He served as Director of the Research Institute for Hepatobiliary Surgery and Director of the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery of Changhai Hospital under the Second Military Medical University, and Vice President of the Second Military Medical University.

6. Dr. Lin Qiaozhi (1901-1983) - China's Pioneer Gynecologist

Known as “the Mother of Ten-Thousand Babies” and “Angel of Life,” Lin Qiaozhi, a famed obstetrician and gynecologist in China, delivered over 50,000 babies in her career, though she didn’t marry or have any children.

Born at Gulangyu Island, in Xiamen, Fujian Province in southern China in December 1901, in 1921 she entered Peking Union Medical College(PUMC). She received her Doctor of Medicine degree and became a doctor in the PUMC hospital in 1929. Lin was later sent to London and Manchester in Britain in 1932 and Vienna in Austria in 1933 for advanced training. She then entered Chicago University Medical School for further study in 1939 and was later named an honorary member of the Chicago Academy of Nature in 1940. She was elected academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 1959.

7. Dr. YanFuqing-Pioneer of Modern Medical Education in China

Born in Shanghai in 1882, he graduated from Yale Medical School with a doctorate in medicine in 1909. That same year, he was elected a member of the American Natural Sciences Association. Upon completion of his studies, Yen made his way to the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in Liverpool, England for one semester's advanced study. For his work, Yen earned a certificate of study.

Yen returned to Shanghai in the winter of 1910 on a two-year Yale-China Association contract, where he worked with Dr. Edward H. Hume. His presence as a Chinese doctor in the leadership of a Western medical organization inspired confidence and interest among other Chinese medical practitioners.

In 1914, he founded the Xiangya Medical College (now part of the Central South University) in Changsha and served as the first principal. In 1926, Yen also co-founded and became the first Dean of the Institution that would ultimately become the Fudan University Medical School. He would go on to spearhead the opening of the Shanghai Medical Center and the establishment of the Hunan-Yale Medical School.

8. Tang Fei-fan (1897-1958)- Pioneer of the Vaccine in China

Born in Liling County, Hunan Province in 1897, he graduated from the Xiangya College of Medicine (now Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University) in 1921. In 1925 he went to the United States to study bacteriology under Professor Hans Zinsser at Harvard University. He returned to China in 1929 and became a Professor at the Medical School of National Central University. In 1935 he was recruited as a researcher at the British National Institute for Medical Research, a position in which he remained until 1937.

After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, he founded the Central Epidemic Prevention Laboratory in Kunming, capital of southwest China's Yunnan Province, and served as its director. He made China's first batch of penicillin vaccines and serum with his team for the soldiers at the frontline. After the war, he established China's first antibiotic research and penicillin production workshop, as well as the BCG vaccine laboratory.

In 1950, a terrible plague hit northern China, he developed an attenuated live vaccine of Yersinia pestis. He also developed China's yellow fever vaccine which helped eradicate smallpox in China in 1960.

In 1955, he first cultured the Chlamydia trachomatis agent in the yolk sacs of eggs.

Medical Education in China

Medical School in China is entered from high school, whereas in the US it is entered after an undergraduate degree that is usually 4 years in length.

Medical school in China takes a minimum of 5 years leading to an MBBS, sometimes followed by a 3 year MM or Master of Medicine. Another route is the 8 year MD route leading to a Doctor of Medicine that is given mainly at the top medical schools in China. In the 8-year MD program, students will typically do 3 years of “pre-med” followed by 2–3 years of “pre-clinical” and then 2-3 years of “clinical” training. Many academic physicians will later do a 3 year PhD after their MBBS or MM.

Top 7 Medical Schools in China

1. peking union medical college.

The top medical school in China, it was founded in 1917 and one of the most difficult to be admitted. For students that are pursuing university degrees in China with a focus on medicine, Peking Union Medical College is one of the top institutions to attend. Peking Union Medical College was the first medical school in China to introduce the eight-year M.D. program.

2. Peking University – Health Science Center (HSC)

Peking University Health Science Center (PUHSC) is one of the nation’s leading institutions of modern medical education in China and is recognized as a renowned medical school both at home and abroad. Established in 1912 as the first public western medical school in China, its former name was Peking National Medical School, and then Beijing Medical University, which successfully developed into a multi-disciplinary comprehensive health science center.

3. Fudan University – Shanghai Medical College (SMC)

Founded in 1927 by Dr. Fuqing Yan—a dedicated Chinese medical educator and scholar in public health, Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University (SMCFU) has a long-standing reputation of excellence in medical teaching, research training for medical professionals. Ranked among the nations leading medical universities since its establishment under the name of Shanghai Medical University, it aims high for academic excellence in addition to the advocation of integrity, devotion, and commitment of society and human beings as a whole. Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University was inaugurated since its merge with Fudan University in 2000.

4. Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU)–School of Medicine

Previously known as the Shanghai Second Medical College which was established in 1952 the name was changed in 1985 to the Shanghai Second Medical University. It is comprised of Medical School of Aurora University (Shanghai), Medical School of Saint John's University, Shanghai, and Tong De Medical College. It was merged with Shanghai Jiao Tong University in 2005 and was named Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

5. Sun Yat-Sen University (SYSU)–Zhongshan School of Medicine

Sun Yat-sen University Zhongshan School of Medicine originated in 1957. It can be dated back to Boji Medical School founded in 1866 -- the oldest school of western medicine established in China. Zhongshan's reputation for quality education, science innovation, and social services have attracted outstanding and diverse teachers and student body with over 18,000 full-time faculties and clinicians, and 8,915 medical and health science undergraduates and post-graduate students including over 400 international students from 28 countries.

6. Central South University (CSU)–Xiangya School of Medicine

Central South University Xiangya School of Medicine dates from the specialized Xiangya Medical School, founded by the Hunan Institute of Education and the Yale-China Association of America in 1914. It is a pioneer of western medical education in China. Through a century's development, it has 8 national key disciplines, 13 provincial key disciplines and 10 undergraduate programs all top-level in China.

7. Sichuan University–West China College of Medicine(WCCM)

The West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, was founded in 1910 as a private medical school, then named HuaxiXiehe College (West China Union College). It was established by five Christian missionary groups from the US., UK, and Canada, with disciplines in stomatology, bio-medicine, basic medicine, and clinical medicine. At present, it consists of 5 Divisions: Clinical Medicine, Laboratory Medicine, Higher Nursing Education, Maternity and Child Hygiene, and Allied Health Professions. More than 1,500 students are studying for a bachelor's degree and over 1,500 students for Masters or Doctorate. There are 165 foreign student placements to study medicine in the school. Over the last five decades, it has been regarded as one of the top 5 medical schools in the country.

- Chinese Healthcare System

- Hospitals in China

- Chinese Healthcare Insurance

8 Top Medical Schools In China For International Students in 2023

Chinese medical schools have gained the world’s attention for their excellent medical facilities, numerous scholarship offerings and well-trained, international medical faculty.

Majority of medical universities in China are recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) and are in the World Directory of Medical Schools. Compared to medical schools in the west, Chinese medical schools have easy entry requirements and lower tuition fees.

In addition, the cost of living in China is much lower, so many foreign students are attracted to study medicine in China. So what are the top medical schools in China for international students?

Best Medical Universities In China in 2023

China has 45 medical schools that are allowed to offer English-medium MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) programs. But these are the 8 best medical schools in China for MBBS .

1. Shantou University Medical College (SUMC)

Shantou University Medical College is located in Shantou, a beautiful coastal city in the Guangdong province. Most MBBS programs in China take 6 years but the MBBS at SUMC only takes 5 years. Read: 15 Reasons to Study MBBS at SUMC .

SUMC has 2 campuses. One where you spend your first few years as a medical student and a second one where your are trained for clinical skills. Shantou boasts of a simulated medical center where you can practice your skills with the aid of virtual learning resources shared by University of Alberta and Stanford University.

Apart from medical theory, you will also get medical training at the Pearl River Delta and Hainan. The curriculum also includes units that help students learn Chinese language and culture.

| September every year (only one intake per year) | |

| Mid-July | |

| • Physically and mentally healthy • Must speak, read and write English well • Valid passport • Clean criminal record | |

| US$6,186 per year | |

| Outstanding Foreign Student Scholarship |

Apply for the MBBS program at SUMC .

2. Nanjing Medical University (NJMU)

NJMU is located in Nanjing, a city rich in Chinese history and culture. The medical university has two campuses: Wutai and Jiangning. The MBBS program takes 6 years to complete, with only 100 students enrolled for the intake. Students can do their internship in any of the following facilities:

– The First Affiliated Hospital of NMU – The Second Affiliated Hospital of NMU – Nanjing First Hospital – Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital

| September every year (only one intake per year) * | |

| End of June | |

| • Must be 18 to 25 years old • Must of good physical and mental health • Outstanding grades | |

| US$5,252 per year | |

| Jasmine Jiangsu Government Scholarship |

*The application can be closed earlier if the targeted number of students is reached earlier. Feedback for the application is usually given within 4 to 6 weeks after application.

Apply for the MBBS program at NJMU .

3. Zhejiang University School of Medicine (ZUSM)

In Hangzhou, one of the most visited places by tourist, lies Zhejiang University. The School of Medicine offers an MBBS program that is recognized internationally. The program takes 6 years to complete including 5 years of classroom teaching and 1 year of internship.

As a student, you will go through three stages of the course which include:

– Pre-med for 1 year – Pre-clinic for 2 years – Clinic for 3 years – Internship for 1 year (you will be supervised by doctors)

| September every year (only one intake per year) | |

| Mid-July | |

| • Must be 18 to 25 years old • Must of good physical and mental health • Outstanding grades | |

| US$6,619 per year | |

| Chinese Government Scholarship |

Apply for the MBBS program at Zhejiang University .

4. Shanghai Medical College of Fudan University (SHMC)

Shanghai Medical College is part of Fudan University, one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in China. SHMC is located in Xujiahui, a commercial district in Shanghai. The MBBS program at SHMC takes 6 years to complete.

You can choose to do your internship in China, your home country or another country. The school will help you find a suitable hospital to do your internship.

If you choose to do your internship in China, you must pass HSK 5 before the internship so that you can communicate with patients effectively. Some hospitals affiliated with Shanghai Medical College include:

– Huadong Hospital – Shanghai Cancer Center – Eye and ENT hospital – Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center

| September every year (only one intake per year) | |

| Mid-July | |

| • Native English speaker • Studied a degree in English before • Have passed IELTS level 6, TOEFL qualification | |

| US$11,598 per year | |

| Outstanding Foreign Student Scholarship |

Apply for the MBBS program at Fudan University .

5. Guangzhou Medical University (GMU)

Guangzhou Medical University is located in Guangzhou, one of the three largest cities in China. It has an amazing campus that is suitable teachers and students. The MBBS program at GMU takes 6 years to complete.

| September every year | |

| First week of July | |

| • Non-Chinese citizen • Good physical and mental health • High school graduate | |

| US$4,639 per year | |

| Chinese Government Scholarship Guangzhou Government Scholarship |

Apply for the MBBS program at GMU .

6. Capital Medical University (CCMU)

Capital Medical University is located in Beijing, China. CCMU has one of the most advanced equipment and international faculty of 994 associate professors and 548 professors. The MBBS at CCMU takes 6 years to complete:

– 1 year of foundation – 2 years of basic medicine – 2 years of clinical medicine – 1 year internship

Students can do their internship in the 14 hospitals the university is affiliated with. CCMU has outstanding reputation in scientific research including traditional Chinese medicine and basic medicine.

CCMU also has partnerships with international education institutions in more than 20 countries and many student exchange programs.

| September every year | |

| First week of June | |

| • Pre-med course which takes 1 semester to complete (2 intakes, March and in June) • Must be between 18 to 40 years old • High school graduate • Must be English proficient | |

| US$7,732 per year | |

| Beijing Government Scholarship |

Apply for the MBBS program at CCMU .

7. Tongji University School of Medicine (TUSM)

Tongji University School of Management is located in Shanghai, the financial capital of China. The MBBS at TUSM takes 6 years to complete.

At TUSM, you will study with dedicated faculty members, undertake research and clinical rotations with national top research teams and affiliated hospitals, and receive a globally recognized medical degree.

You will also enjoy a dynamic campus life and meet students from all over the world. TUSM’s ultimate goal is to train doctors who are competent in the delivery of effective and ethical medical care in today’s rapidly changing health-care environment.

| September every year | |

| May | |

| • Have passed IELTS level 6, TOEFL qualification • Must be between 18 to 25 years old • High school graduate | |

| US$6,959per year | |

| Entry Scholarship Dean Scholarship Tongji Presidential Scholarship Shanghai Government Scholarship (Class C) |

Apply for the MBBS program at TUSM .

8. Jinzhou Medical University (JZMU)

Jinzhou Medical University is located in northeastern China in the city of Jinzhou. The MBBS program at JZMU takes 6 years to complete, inclusive of one year of internship. Internship is done at the First Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning Medical University (LMU).

| September every year | |

| End of August | |

| • Physically and mentally fit • Must be between 18 to 25 years old • High school graduateNo criminal record | |

| US$5,412 per year | |

| Chinese Government Scholarships |

Apply for the MBBS program at JZMU .

Apply for MBBS in China!

Studying MBBS in China is something you will never regret. Read our MBBS guide , choose a university, apply for the next MBBS intake and get your medical career started.

- Recent Posts

- Study MBBS in China: Admissions Guide for 2024! - June 12, 2024

- 8 Universities in China with the Best Online Chinese Programs for 2024 - June 2, 2024

- Introducing The Sino-British College, USST (SBC) - June 1, 2024

Join 180,000+ international students and get monthly updates

Receive Admissions, Scholarships & Deadlines Updates from Chinese Universities. Unsubscribe anytime.

- Online Programs

- Chinese Programs

- Foundation Programs

- Medicine – MBBS

- Chinese Language

- Business (BBA)

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- Business Management

- See All PhD Programs

- How to Choose Programs

- Learning Chinese & HSK

- Internships in China

- Browse All Programs

- University Rankings

- Most Popular Universities in China

- Top 16 Chinese Universities

- See All Universities

- Online Classes

- Register an account

- Ask a question

- Join the Wechat Group

- Moving to China

- Jobs / Careers

- Studying in China

- Universities

- Fees & Finances

- Scholarships

- Why China Admissions?

- Our Services

- Book a Call with Us

- Testimonials

Request Information

Download your free guide and information. Please complete the form below so we can best support you.

- What language would you like to study in? * Select English Chinese

- What is your highest education level? * Select Secondary School High School Bachelor’s Master’s PhD

- How are your grades? * Select Below Average Average Above Average Exceptional

- How is your English level? * Select None Beginner Fluent Advanced Native

- How is your Chinese level? * Select None Beginner Fluent Advanced Native