The past, present and future of feminist activism in Pakistan

Interviews conducted by Manal Khan and Sameen Hayat.

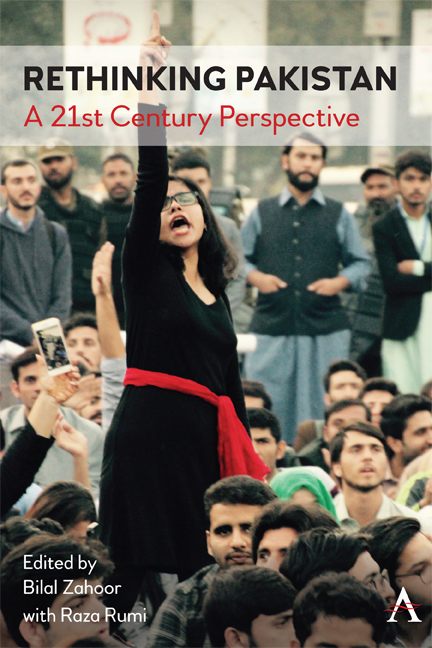

Aurat March 2019 was one of the most exciting feminist events in recent years. Its sheer scale, magnitude, diversity and inclusivity were unprecedented. Women belonging to different social classes, regions, religions, ethnicities and sects came together on a common platform to protest the multiple patriarchies that control, limit and constrain their self-expression and basic rights. From home-based workers to teachers, from transgender to queer — all protested in their unique and innovative ways. Men and boys in tow, carrying supportive placards, the marchers reflected unity within diversity, seldom seen in Pakistan’s polarised and divisive social landscape.

Carried out in many cities across Pakistan, the march took both its supporters and detractors by surprise. No one expected such a big turnout and in so many cities with truth-laden and daring placards. The intensity of the vitriol seen in the backlash to the march testifies to its enormous success — it certainly managed to hit patriarchy where it hurts.

Aurat March 2019 also marks a tectonic shift from the previous articulations of feminism in Pakistan. It would not be far-fetched to say that it has inaugurated a new phase in feminism, qualitatively different from the earlier movements for women rights. While the past expressions of feminism laid the foundation for what we see today, the radical shift of feminist politics from a focus on the public sphere to the private one – from the state and the society to home and family – manifests nothing short of a revolutionary impulse. Feminism in Pakistan has come of age as it unabashedly asserts that the personal is political and that the patriarchal divide between the public and the private is ultimately false.

The social, political and historical context of each previous form of feminism was different and the feminist issues of each era arose from particular moments in national and global histories. In the early years of Pakistan’s formation, the wounds inflicted by the bloodstained Partition were fresh. Women activists were focused on welfare issues, such as the rehabilitation of refugees, because that kind of work had social respectability within the traditional cultural milieu.

Pakistan also inherited many social issues – such as polygamy, purdah, child marriage, inheritance, divorce and the right to education – from the pre-Partition times. Many of the demands for social and legal reforms on these issues were acceptable even within the bounds of religion. So, there was no fear of women upsetting the applecart when they asked for these reforms.

The 1960s saw the proliferation of women’s welfare and development organisations but it was the All Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA) that became the face of the women’s movement in the country in that decade. The passage of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, pushed by APWA, reflected a minor ingress by the state in the private sphere as it placed certain procedural limits on the men’s arbitrary right of divorce and gave women some rights regarding child custody and maintenance. Even the small changes repeatedly stirred public controversy with clerics clamouring for the reversal of the ordinance.

APWA’s approach was characterised by two salient features: one, the focus on social welfare and development work involving girls’ education and income-generation activities; two, the collaboration with the state to achieve its aims. APWA shied away from an overtly political position in that it did not contest dictatorship. It did not ruffle any religious or political feathers and preferred to play it safe even when Fatima Jinnah, a woman, remained the sole campaigner against dictatorship. The cooperation and collaboration of women leaders with the state to attain women’s rights continued during the civilian rule of the Pakistan Peoples Party (1971-1977).

The feminist movement and the women’s rights struggle that arose in the 1980s, spearheaded by Women’s Action Forum (WAF) in the urban areas and Sindhiani Tehreek in rural Sindh, were significant for their overtly political stance. As both these movements were formed in the context of a hypernationalist absolute dictatorship that relied on a particular version of religion for legitimacy, they consistently challenged both the military rule and the incursion of religion in politics. WAF struggled for a democratic, inclusive, plural and secular state while Sindhiani Tehreek strove for an end to feudalism and patriarchy, sought the restoration of democracy and championed the principle of federalism and provincial autonomy.

These movements represent a significant break from the former paradigm of collaboration and cooperation with the state. They challenged patriarchal power in every domain — political, religious and legal. Unlike the welfare and social uplift-oriented movements of the 1960s, the struggles launched by women in the 1980s were essentially political movements anchored in the ideas of democracy, basic rights and sociopolitical change. As they confronted the authoritarian state, women in these movements could ill-afford to play it safe like their predecessors. They, therefore, engaged in frequent street protests and demonstrations. They took risks and were occasionally beaten, jailed, baton-charged and otherwise threatened by the dominant religious-military patriarchies of the time.

WAF had to respond quickly and frequently because of the rapid pace at which the regime was promulgating discriminatory laws and taking anti-women measures. The focus of the WAF members was squarely on the public sphere where the state machinery was utilised to brutally repress anyone who dared to stand up to the dictatorship. The aggressive and intrusive reconstitution of the private sphere, through instruments such as the Hudood Ordinances, had to be resisted at the public level by fighting legal cases, speaking up and protesting on the street.

Given the dizzying pace at which the regime and its religious allies had to be countered, there was little room for internal reflection in WAF. Although most of its founders had a strong feminist background and a feminist lens for unpacking the dominant narratives, the space for interrogating private life had shrunk. WAF members knew that patriarchies work through the bodies of women and write their strictures on those bodies. They also understood that the traditional family, which controls and organises the human body and sexuality, is the mainstay of patriarchies. Yet they were constantly occupied with contesting the state’s laws being drawn from a singular interpretation of religion. In private conversations, the politics of the body in the body politic were often discussed but, publicly, WAF was only engaged in countering the imperious state.

Some of the reasons for the reticence were internal. WAF was composed of a diverse set of organisations and individuals with differing perspectives on religion, culture and tradition. This diversity grew out of the necessity to have maximum numbers to confront a heavy-handed regime. WAF was reluctant to take too radical a stand on the body, sexuality and the family as many of its members were religious, conservative and deeply embedded in traditional family systems. The conversations on the body, sexuality and the freedom to express oneself in one’s own way did not become a part of the official public agenda of WAF.

Ironically, while WAF members avoided public discussions on the body and sexuality, the state and religious clerics had no such qualms; their focus was squarely on the woman’s body — the need to conceal it, cover it, protect it and preserve it for its rightful ‘owner’. The state was consistently referring to sexuality (for example, in laws on fornication, zina), the veil and the four walls of the house — all designed to control the rebellious and potentially dangerous female body capable of irredeemable transgression.

This is where the new feminists break from the older generation and mark a powerful shift in the feminist landscape. Even as new feminism retains many of the older critiques of the state, fundamentalism and militarism and reflects the desire for equality and democracy, it reaffirms the personal and injects it right into the heart of the political. ‘My body, my will’, it tells patriarchy to its crestfallen face. ‘Warm your own food’, ‘I don’t have to warm your bed’, ‘don’t send me dick pics’ — in curt one-liners, the new young feminists reclaim their bodies, denounce sexual harassment, stake a claim to public space and challenge the gender division of labour on which rests the entire edifice of patriarchy.

The new wave of feminism includes people from all classes, genders, religions, cultures and sects without any discrimination or prejudice. The young feminists are diverse, yet inclusive, multiple yet one. There are no leaders or followers — they are all leaders and followers. The collective non-hierarchical manner of working and the refusal to take any funding is similar to the functioning practised by WAF and represents continuity with the past. But the entire framing of the narrative around the body, sexuality, personal choices and rights is new. The young groups of women say openly what their grandmothers could not dare to think and their mothers could not dare to speak.

They say what women have known for centuries but have not been able to voice. They have broken the silences imposed by various patriarchies in the name of religion, tradition and culture. They have torn down so many false barriers including the four walls of morality built to stifle their selves and curb their expression.

The backlash has been swift, fierce and expected. Patriarchy began to shake in its boots and masculine anxiety reached a peak as women hit it where it hurt. The self-appointed guardians of morality, who in the past never touched the issues of violence and inequality, have been quick to condemn the marching women in their television chatter shows, puny little newspaper columns and silly tweets. The blowback from little people is not new for feminists.

The critics certainly cannot stop the marchers. Will money hinder their path? There are questions about the sustainability of the feminist movement given that the young feminists do not take any funding from corporate, government or foreign donors. The tremendous energy and passion generated by the march, however, are enough to ensure that these activists will continue marching into unknown but exciting futures.

Reactions to Aurat March, held on the International Women’s Day on March 8, 2019, ranged from supportive to condemnatory and everything in between. The national conversation that followed raised some important questions not only about the role and status of women in the Pakistani society but also the significance of the issues highlighted by the marchers.

Partaking in this conversation, we devised a set of questions and sent them to different feminist activists, all aged below 30, who had taken part in the march. Our endeavour is aimed at finding – as well as recording – their responses to the criticism of the issues raised by the marchers. It is also an attempt to explore their personal and ideological reasons for joining feminist activism.

The questions follow:

Q1. How and when did feminist activism become relevant to you and why?

Q2. How do you view the evolution of feminism in Pakistan? Do you see any difference between the movement launched for women’s rights during the era of General Ziaul Haq and the contemporary feminist activism?

Q3. There are always social, cultural, religious and even economic costs of being a feminist in Pakistan. How do these challenges impact your activism?

Q4. What else, besides Aurat March, should women activists in Pakistan do to make themselves heard?

Q5. Do you think feminist activism in Pakistan can succeed in securing women’s rights without addressing the divisions caused by class, caste, ethnicity and religion?

Atiya Abbas

A 29-year-old communications expert based in Karachi; a member of Girls at Dhabas, a feminist initiative aimed at claiming public spaces for women

A1. Feminist activism became relevant to me in 2015 when I joined Girls at Dhabas. What became central to my understanding of feminism was the basic and the most tenuous idea that even the ability to breathe freely in a city that has very little space for solitude is a radical act.

A2. Zia-era feminists launched movements to bring changes in laws and policies. Many of those changes were subsequently implemented which is why we enjoy some freedoms. Even asking questions about these freedoms was not easy 30 years ago. Younger feminists are asking such questions everyday — whether these are about unpaid domestic labour, inequality in marriage, sexual harassment at workplace or the right to access the streets without fearing for safety. The tool they wield is social media which is a quick way to disseminate information. That is why conversations around feminism and equality have mushroomed so quickly in our cultural conscience.

A3. I am speaking from a perspective of immense privilege when I say that my father is a feminist and I have a circle of feminist friends who are my source of solace and comfort. Ultimately, I go back to a loving home where I feel safe.

A4. Taking to the streets, marching, protesting, going to talk shows, writing columns, sharing thoughts on social media — women activists are doing a lot to form a feminist discourse in Pakistan. From taking former minister Kashmala Tariq’s tweet that “Good morning messages are also harassment” out of context, to calling women names in the legislative assemblies, to the structure of our courts having misogyny built right into them — it is the male and patriarchal detractors of equality that keep hindering progress. Maybe they should start listening and lean in.

A5. A feminism that is not intersectional is no feminism at all. Aurat March was one way of bringing women from all backgrounds on one platform. There, however, is an unnecessary burden on middle class women to also ensure the empowerment of women from other disenfranchised groups as nothing is being done at the institutional level in this regard. As feminist academic Tooba Syed wrote: “It has been particularly interesting to witness bourgeoisie men engage in an entirely selective class critique when it comes to women — an intellectual inconsistency that has never been more transparent. The critique is particularly insincere because it puts the entire burden of working-class representation on the shoulders of middle-class women [activists] instead of having a nuanced debate about concerted efforts to weaken the left [in] the country’s wider political spectrum.”

Huda Bhurgri

A 26-year-old academic based in Islamabad; a member of the Women Democratic Front, a political association

A1. I was born in a feudal family where men held all the sociopolitical and economic power and privilege. In a way, I myself was privileged — not because who I was or what I had done but only because I was the daughter of someone and belonged to a specific class. This class structure is deeply rooted in patriarchy but I realised that, no matter where a woman is born, she does not exist in a society as a free human being. Her existence is a mere shadow which is directed and cast by men who control her life either as her father, brother, husband or son. Feminist activism became relevant to me after my exposure to experiential reality as a woman born and raised in a patriarchal society.

A2. Feminist movement during Zia’s era focused on resistance politics against tyrannical rule of a despot who tried to control the conduct of women. It helped to awaken collective consciousness about patriarchy and also helped to create debates against the draconian [anti-women] law of evidence [promulgated by Zia]. The contemporary feminist movement, on the other hand, is demanding social, political and economic justice from the society, the state and the judiciary. This home grown feminism is no more for the rights of women alone. It also focuses on the right to self-determination of transgender and non-binary people. The contemporary feminist movement of Pakistan is very inclusive and speaks against both patriarchy and capitalism.

A3. Most of the people are not ready to listen to a woman who speaks for equality so, usually, we have been labelled with derogatory names. But we know that ours is a resistance politics and it can never be easy. No matter what it costs, this resistance against patriarchy is a worthy cause. Obstacles cannot deter the true consciousness of women.

A4. Other than Aurat March, women from the legal fraternity, political parties, academia and media should work on politicising women folk across Pakistan through different channels. There is a dire need for an alternative discourse which supports laws and social and economic policies that are women-friendly. This is not possible if women are not given positions where power resides; women, therefore, have to step outside domestic roles to attain their human rights.

A5. The present feminist movement in Pakistan is not ignoring other contradictions such as the class conflict, casteism, religious extremism and racial differences. Patriarchy draws its power from all these sources, therefore the fight for women’s rights is also a fight against every type of discrimination at all levels of society.

A 24-year-old based in Peshawar; co-founder of Daastan.com, an initiative to promote literary activities

A1. I had just moved out of an all-girls school and shifted to an all-girls college which meant I had more freedom than before to go out, explore and learn about the world. It was during this time that I often saw catcalling, stalking and a lack of opportunities for girls. My rebellion against such behaviour started when I began writing small poems and stories about hypocrisy in our society. Later on, after I had more exposure towards social problems, I came to realise that these had been rooted in our history and I had to fight against them come what may.

A2.I believe social media has helped us come a long way. We have started to speak about personal autonomy, class differences, a more transparent political presentation, equal wages and much more. While feminism in Zia’s era was political, today it is becoming intersectional due to its development both globally and nationally. We have more freedom of speech than the past and the moment is, slowly and gradually, becoming inclusive. It is addressing the rights of all genders.

A3. Life is difficult for feminists in our society. One of the major reasons for this is a lack of awareness in our society. We do not see feminism as a movement that ensures equality but one that will provoke conflict among genders. At Daastan.com, we frequently face backlash for bringing marginalised voices forward. We faced massive threats when we published an e-zine called Outcast. We had to seek legal support against those threats.

At the Peshawar Book Club, we faced heated arguments for presenting a selection of books written by feminists. Those books were disliked. The society had a negative perception about them regardless of their brilliance. Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood’s book, The Handmaid’s Tale, made us face the wrath of some members of the club. They called feminists as delusional for believing that women are oppressed

A4. Aurat March is a brilliant initiative. It should be followed by monthly dialogues, workshops as well as political movements. We need more women in the legislature who are responsive to our demands for gender equality. We need to rally support for all those women who came forward to raise their voices during the march so that they continue doing so all year around. This can help us in building a curriculum for consciousness raising and awareness on a deeply rooted misogyny and its implications.

A5. Pakistan has a pluralistic but a highly stratified society. The problems of every class, caste, ethnicity and gender vary and cannot be seen through a single lens. A more diverse representation of women is needed in the feminist movement to have a better understanding of their problems. We cannot only be the voice of young upper middle class women. We need to expand our activism. Aurat March 2019 has improved on the previous edition of the march by integrating voices of women from all ethnicities, religions and classes but we still have a long way to go. Such an integration can play an enormous role in the growth of the movement and eventually in its impact.

Minahil Baloch

A 19-year-old aspiring film-maker born in Khairpur but studying in Karachi

A1. Two years ago, I did not take much interest in feminist activism or feminism in general but, with time, I realised how I had been conditioned into thinking that it was okay for the society to work in a certain way. When I unlearned this and learnt about how a patriarchal system works, I could see how relevant activism was to my life. I started analysing my life and noticed how a patriarchal system has normalised sexist behaviour in our daily lives. What I heard a lot was: tum baiti naheen ho, baita ho hamara (you are not our daughter but our son). According to parents, this is a very progressive thing to say but it is not. It is not their fault though. They have been conditioned into thinking that way.

The other reason why my interest increased in feminism is that I want to reclaim the freedom Baloch woman have enjoyed historically. There is this stereotypical perception that Baloch women are not independent and free but this is not true. If we see historically, Baloch women have always been free women.

A2. We have evolved a lot [since Zia’s time]. We have become clearer about the problems we face in a typically patriarchal Pakistani society. Feminists under the Zia regime were fighting a battle against the man himself but the contemporary feminist movement is fighting against the mindset that he has left behind. This mindset is now more intense and extreme than what feminists faced then.

Also, opportunities for online activism were not available back then but these are a [big thing] now, making it easier for feminists to educate themselves through the internet — something that itself comes with a lot of cyber bullying, harassment, rape/death threats. The contemporary feminists have to fight online harassment as well along with harassment on the ground.

A3. Why people around us have issues with feminism and feminists is because they have been conditioned into believing that feminism is a ‘western’ concept. We need to understand their mindset in order to change them. That in itself is a fight and a half, and requires a lot of emotional labour to fight. So, yes, there are some challenges but if we understand that people are conditioned to see feminists in a particular way and that we are here to change that mindset, that will make things a lot easier.

A4. As a film student, I feel like films have a huge impact on the minds of their audiences. More films, therefore, should be made that revolve around women’s issues. This will help film audiences change their perspectives on these issues. At the very least, this will help them have a rethink.

A5. A feminist movement cannot succeed without including a struggle against class, caste, ethnicity and religion because these are the ingredients of a typical patriarchal system. For example, religion is often rubbed into our face when we put forward a valid feminism argument. People belonging to the elite class are privileged enough to not have the same problems as those belonging to the middle class have, so I have seen them invalidate the problems of the lower classes. Feminism cannot work without bringing these issues into its framework.

Sana Lokhandwala

A 27-year-old based in Karachi; co-founder of HER Pakistan, a charity working on improving menstrual hygiene awareness

A1. I have always been aware of the strict gender roles and gender bias around me but I have been more a passive feminist than being a ‘feminist activist’. I was never out there fighting for it like a lot of other strong women but I was doing my part quietly in my own way. It was only when HER Pakistan came into being that I realised that there is a need to actively fight against the oppression. Women in Pakistan do not even have the right to make decisions about their own bodies and health. They have to rely on men in their households to procure something as basic as a sanitary pad. Menstruation, which is a natural process, is termed ‘dirty’ and ‘disgusting’ only because it is about a woman’s body.

A2. Feminism has been very much a part of Pakistan since the independence. Fatima Jinnah and Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan struggled for the rights of women in the earliest times. Zia’s era was more challenging. Parts of Hudood Ordinances that pertain to rape and adultery and the impact these had on female rape victims forced feminists of the time to step up and protest for their rights. Present-day feminism, however, is more pluralistic and accepting in terms of gender, sexuality, race, class and religion than its past editions. But, although a number of laws on women’s empowerment, sexual harassment at the workplace, honour killings and even domestic violence have been passed in recent times, Pakistani feminists still need to continue to protest over violence against women, raise awareness about women’s education, work for political, legal and health rights of women and struggle for more women-friendly laws.

A3. The negativity around feminism in Pakistan is frustrating. It takes an emotional toll on everyone who is struggling to create a better society for women, but good things do not come easy. It is a fight worth fighting. Personally, negativity and backlash just give me more strength to keep going. When people tell me there is no need to talk about menstruation in public, I go on and educate 100 more people about it.

A4. Although Aurat March is a relatively new phenomenon in Pakistan, women have always done one thing or the other to get their voices heard. Be it through art or dance or poetry or social media, Pakistani women have never shied away from standing up for their rights. Although a lot of women are doing amazing work in order to create a more balanced Pakistan, I believe all activists should join forces every now and then to create a powerful statement — just like Aurat March did.

A5. Feminism is not only a movement, it is also a way of life. It cannot work in isolation. You cannot solve the problem of gender bias without solving the problems of class, caste, ethnicity and religion. Women of colour and those who come from underprivileged backgrounds have always been exploited. Gender equality is for everyone regardless of their class and race.

Sadia Baloch

A 19-year-old studying at the University of Balochistan, Quetta

A1. I was raised in a society where women are used to being manipulated, exploited and violated. They are considered the property of males in their families, irrespective of which class, ethnicity or religious group they come from. The owner of the property has the right to decide its fate. This concept of men owning women has turned women into a commodity which can be exchanged, bought and sold. In a tribal society like Balochistan’s, a woman’s shame is the shame of her husband; her honour is her man’s honour. A man can do anything and go anywhere but a woman’s leg is broken if she breaks the society’s laws. She is not free to go where she wants. A man can be bad and no one will say anything but everyone knows when a woman is bad. This is what urged me to fight against patriarchy in Balochistan.

A2. There was a time when we had WAF which encouraged feminist activists of a whole generation. On the contrary, in contemporary times, one can see movements in Islamabad, Lahore and Karachi which have a bit of elitist notions of freedom and equality. The sufferings of being a feminist, especially in Balochistan, are still beyond [the pale of the current movement]. There is a need to expose different facets of oppression which women of different classes and oppressed nationalities face on daily basis. Still, I see an umbrella of sisterhood as the only way out.

A3. Women’s freedom is often considered as being against the teachings of Islam as well as against many cultural norms. This is especially so when one is fighting against strict patriarchal norms in a tribal society. The mullahs, the deciders of the fate of women and the self-proclaimed guardians of Islam, have lynched women in order to save Islam. Religion and patriarchy are the toughest enemies of women. They both place women in a subordinate position, allowing men to control their access to material resources as well as to their own sexuality. So, definitely, fighting against such suppression is tough and there are challenges.

A4. To make ourselves heard, we must make noise first. Aurat March was that noise. Now our voices can be heard even by the deaf. No matter what platform we use, everyone will have to pay heed. We should, however, realise that a disciplined struggle under an organisational structure has always proven effective so women should start participating in political activities by joining political parties at every level. Instead of joining mainstream and elite-ruled parties, however, they should join leftist student organisations or they should join women-only groups where they can meet like-minded women with common aims. Women who might find it hard to become a part of political organisations should never forget that they can make a difference even individually. One daring girl can change what thousands might fail to change. So, women should start standing up for themselves at their offices, schools, colleges and even at public places that they usually avoid going to.

Women activists should run awareness campaigns. Women who are political activists and who are knowledgeable should teach other women that there is nothing wrong with them but it is the society and its norms that make them think so, and that they need to join hands and start breaking norms. They should continue doing so until breaking norms becomes a new norm.

A5. As long as women do not realise the need for a social revolution, including for the demolition of patriarchal and tribal tyranny, they will not succeed. For feminist activism in Balochistan to succeed, it is a necessary requirement to end violence against women, to empower them, to break the cycle of their oppression and exploitation. Male members of the society must take a step back from their patriarchal mindset in order to give women the space to enjoy their freedom and have agency in their own lives. Feminist activism both has a place and a role to play in national struggles in political and cultural spheres.

Yusra Amjad

A 25-year-old poet and stand-up comedian based in Lahore

A1. I grew up with an abusive father so I have witnessed the ugliness of patriarchy since childhood. I became more and more confident about owning the label of feminist as I grew older. When I was a teenager, it was much less acceptable to call oneself a feminist than it is now but I have always been staunchly passionate about standing up for, and having solidarity with, other women. I grew up in very women-centric spaces and I found them positive and nurturing for me. In college, I started to write about harassment and the patriarchal elements of institutionalised religion. Then I met Sadia Khatri who got me involved with Girls at Dhabas, a collective focused on reclaiming public spaces for women. I started to become more organised in my activism through that. Since then I have also helped organise Aurat March in Lahore both in 2018 and 2019. Activism is important to me because I want to play a part in levelling the playing field for women in whatever way I can. I am incredibly privileged in multiple ways as well and I consider it my responsibility to use my privilege for the benefit of the marginalised communities.

A2. Feminist activism was a very ‘niche’ thing in the 1980s, pursued by committed individuals. It was not the common talking point than it is today. In its own way, it was also a lot more dangerous back then. The focus back then was on challenging misogynist laws and legislation whereas the current wave of feminism is challenging [other] forms of misogyny — such as social attitudes, the policing of women’s bodies, their movement and their sexuality and social evils such as dowry culture. And, of course, feminist activism now has become a ubiquitous conversation because of the social media which was not the case before.

A3. I really think social media has made life dangerous for feminist activists (though, of course, it is also a great tool for activism). It is a new – and endlessly accessible – platform for violence against women. Think about it: if a dupatta burning protest had happened today, women would have been threatened not just by the state and the police but their social media profiles would have been targeted too. They would have faced a barrage of online rape threats. They would have had their faces photo-shopped onto pornographic images. This, of course, is not to say the challenges the previous generation of feminists faced were any less scary or daunting but, nowadays, the backlash does not end in the physical space. It continues in online spaces. Every feminist I know deals with the backlash in their own unique way. My preferred coping mechanism is wilfully ignoring many of the risks and consequences. Social media is also a democratic space for us to fight back. [Our detractors] can censor print and television media but they cannot, at least so far, stop us from putting up a Facebook status.

A4. Aurat March is aimed purely at women who are socially privileged like myself — who can challenge men in their drawing rooms, who can challenge men in their bedroom and who can challenge men at dinner parties. I am so tired of seeing privileged women sharing #MeToo posts and then inviting harassers to their events and parties just because the said harassers are wealthy, well connected and popular. I am tired of women sharing feminist memes and giggling while their husbands tell women-belong-in-the-kitchen jokes. Listen to working-class women. We are complicit in their oppression. Give them their rights, their minimum wage, their sick leave, their maternity leave. And speak up when someone abuses their servants.

A5. To quote [Dutch feminist writer] Flavia Dzodan, our feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit. In Pakistan, we especially have to consider our Sunni Muslim privilege. That being said, the most financially privileged men will use their faux concern over ‘class politics’ and ‘the proletariat’ to silence issues of gender politics. It is not for privileged men, however leftist they claim to be, to tell any woman how to address intersectionality. If it comes down to it, giving a platform to a privileged woman is still more subversive than giving a platform to a privileged man.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Fate of Feminism in Pakistan

By Bina Shah

- Aug. 20, 2014

KARACHI, Pakistan — On Feb. 12, 1983, 200 women — activists and lawyers — marched to the Lahore High Court to petition against a law that would have made a man’s testimony in court worth that of two women. The Pakistani dictator Gen. Muhammad Zia ul-Haq had already promulgated the infamous Hudood Ordinance, which reflected his extremist vision of Islam and Islamic law. Now, it was clear to many Pakistani women that the military regime was manipulating Islam to rob them of their rights.

General Zia’s days are over, and parts of the Hudood laws pertaining to rape and adultery have been superseded by less objectionable clauses in Pakistan’s Protection of Women Act of 2006. But Pakistani women have yet to achieve what Madihah Akhter, writing in The Feminist Wire, an online magazine, identifies as “political, cultural and economic equality for women and a place in the constant struggle to define their nation.”

The reality of Pakistan’s women continues to confound easy categorization. They have been going to school and university, holding down jobs and earning money for several generations now. Yet they still live with widespread gender-based violence, society’s acceptance of women as property, and a widespread belief that they don’t deserve education, jobs or an existence outside the domestic sphere.

Neither Pakistan’s laws nor its social codes nor its religious mores truly guarantee women a secure place as citizens equal to men; such attitudes are preserved by patriarchal tribal and cultural traditions, as well as the continued twisting of Islamic injunctions to suit the needs of misogynists. Could feminism be the best antidote to this male chauvinism ingrained in modern Pakistani society?

Feminism has been alive in Pakistan since the country was born. During partition of the British Indian Empire in 1947, a Women’s Relief Committee, which oversaw refugee transfers between India and Pakistan, was founded by Fatima Jinnah, the sister of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father. Then Begum Ra’ana Liaqat Ali, the wife of Pakistan’s first prime minister, founded the All-Pakistan Women’s Association in 1949; that organization worked for the moral, social and economic welfare of Pakistani women. Ms. Jinnah ran in the presidential elections in 1965 and was even supported by orthodox religious parties, but lost to the dictator then holding the office, Gen. Ayub Khan.

In the 1980s, the Women’s Action Forum used activism to oppose General Zia’s myopic vision of Islam; today, Pakistani feminist collectives continue to protest violence against women, raise awareness about women’s education and political and legal rights, and lobby policy makers to enact women-friendly laws. The groundbreaking Repeal of Hudood Ordinance, the women’s empowerment bill and anti-honor-killings bill were all moved in Parliament when Sherry Rehman, a former ambassador to the United States and a renowned feminist, held the portfolio of minister for women’s development in the last decade. These and the anti-sexual-harassment bill were all eventually codified in Pakistani law over the next several years.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

Pakistan: A Rising Women’s Movement Confronts a New Backlash

To build justice and peace in a nation vital to security, feminism needs a religious message.

By: Aleena Khan

Publication Type: Analysis

Thousands of women rallied across Pakistan on International Women’s Day this year and demanded an end to violence against women and gender minorities. In the days since, Pakistan’s Taliban movement has escalated the threats facing the women who marched. Opponents of women’s rights doctored a video of the rally to suggest that the women had committed blasphemy—an accusation that has been frequently weaponized against minorities in Pakistan and has resulted in vigilantes killing those who are targeted.

To celebrate this year’s International Women’s Day, Pakistani women held what they call the Aurat (Women)’s March—an annual series of rallies that began in Karachi in 2018. This year’s Aurat March—held in at least seven cities nationwide—included demands for safety from endemic violence, accessible health care in a nation where nearly half of women are malnourished, and the basic economic justice of safe working environments and equal opportunities for women. In Pakistan, as in other countries where women already were most vulnerable, the COVID pandemic has exacerbated their crises, including gender-based violence .

But the extremist backlash —including street protests, a Taliban condemnation of the women for “actively spreading obscenity and vulgarity,” and an organized social media disinformation campaign against the organizers and supporters of Aurat March—underscores how exclusionary, unjust, unsafe and violent Pakistan remains for most of its 101 million women. In the most recent Women, Peace and Security Index —a measure of women's well-being and their empowerment in homes, communities, and societies—Pakistan was ranked among the world’s 12 worst performing countries. The latest Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey estimated that 28 percent of women in Pakistan have “experienced physical violence” by the age of 50. Still, with no real national data, the full scale of Pakistan’s violence against women remains murky. The escalated backlash against women’s activism emphasizes not only the need for their movement but also the need to overcome the dominant patriarchal narrative about religion that falsely portrays feminism as inimical to Islam.

While the suffering of Pakistan’s women is anguishing, this extreme inequity in the world’s fifth most populous nation should concern moralists as well as foreign policy realists for the simple reason that greater inclusion and equality of women make the world more peaceful for all. States with greater gender equality behave less violently amid international disputes, research studies find. Overwhelming evidence also shows that inclusion of women in peace processes makes these processes more sustainable. In Pakistan’s case, achieving gender equality is critical for the country’s long-term evolution as a resilient democracy that can meet its people’s needs, adequately confront violent extremism, resolve its conflicts non-violently and help stabilize a region that poses constant international security threats.

Response to Violence: Reaction, Not Prevention

Recent violence in Pakistan lent particular poignancy to last week’s women’s rights rallies. In September, when a mother ran out of gas while driving her two young children on a highway, two men raped her—and one of Pakistan’s most powerful police officers blamed her for inviting the crime by having driven at night. A storm of protest erupted, focusing national attention on gender-based violence, including a spate of attacks against transgender women.

The highway attack was the latest in atrocities over decades to re-ignite a national discourse on gender-based violence that remains largely reactive in nature. The government passed a new anti-rape ordinance in December, promising harsher punishments like chemical castration for perpetrators and speedier trial of rape cases through special courts. Similarly, the spike in violent attacks on women during COVID has produced demands for measures like national helplines, shelters, legal aid and psycho-social support for victims. As vital as these measures can be, the nation’s response still fails to move to prevention by addressing the causes of violence against women.

Leading Pakistani scholars and advocates on women’s rights assessed those causes last month in a new USIP working group on gender issues in Pakistan. They described the exclusion of women in Pakistan’s social, political and economic institutions as a structural cause of inequity that renders women more vulnerable to violence. The literacy rate among girls and women is 22 percent lower than men. Women are 49 percent of Pakistanis, yet form only about 22 percent of the country’s labor force and receive only 18 percent of its labor income. Women hold only 5 percent of senior leadership positions in the economy. Women vote much less often in both rural and urban areas , and women form only 20 percent of the parliament. Women are less than 2 percent of the police force and are severely under-represented in the country’s superior courts.

A significant source of women’s vulnerability to violence is their financial dependence on their fathers, brothers or husbands. Tradition assigns women all household chores and discourages them from working outside the home. Work environments and public spaces that are hostile to women obstruct them from both the formal and informal economy. The few women who do participate in the workforce largely constitute the informal economy, where wages are abysmally low and economic vulnerability to external shocks like the pandemic is higher . Men’s monopoly over household income and assets, combined with a belief that women should tolerate violence to keep the family together, leaves women not only more vulnerable to violence but also incapable of escape.

Pakistani society’s patriarchal mindsets reinforce these gender disparities, noted the discussants in USIP’s gender working group. Inevitably, these mindsets extend to political and state institutions. The police official’s blaming of the woman raped on the highway reflects the systemic misogyny embedded throughout state institutions and the political environment. Thus, even though federal and provincial legislatures have passed laws to bar child marriage, workplace harassment, domestic violence, “honor” killings and acid attacks against women, they remain largely unenforced.

Way Forward: Reconciling Feminism and Islam

A broader change in gender mindsets is therefore imperative in Pakistan—and is a goal for which the Aurat March has been mobilizing men and women since 2018. While the Aurat March has focused on mobilizing people from marginalized segments of society such as low socio-economic groups and religious minorities, the campaign has remained restricted to select cities. It has yet to gain momentum in rural areas, where gender inequalities are worse .

This month’s backlash by the Taliban and others amplifies intense criticism of the movement from among Pakistan’s news media, religious scholars, established politicians and the public. The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provincial assembly last year formally condemned the Aurat March and politicians have filed complaints against it with police and courts. Critics of the movement accuse it of serving a “western agenda” and of being “un-Islamic.”

The criticism against the Aurat March stems from a simplistic dichotomy that sees feminism and Islam as irreconcilably opposed ideas. This false dichotomy has been cemented by mainstream interpretations of Islam that use a patriarchal cultural lens and systematically exclude feminist narratives available in Islamic traditions. The religious narrative in Pakistan has so fully absorbed patriarchal cultural ideas that those who challenge patriarchy are accused of being irreligious. Such allegations are hard to dismiss when they resonate with the majority of Pakistanis, for whom religion is central to personal and collective identity. Women’s rights movements like the Aurat March are, therefore, likely to remain polarizing, misunderstood and ineffective unless they integrate feminism, modernity and Islam in their narrative, and engage progressive religious scholars. A continued disconnect with religion will hamper the Aurat March from creating a critical mass for gender justice in Pakistan.

This disconnect applies not only to social movements but also to wider advocacy and development efforts. USIP’s initial roundtable discussion on gender inequality and violence also failed to explore religion as a contributor to gender injustice, and more importantly, as a potential tool for reform.

Muslim women in Pakistan and across the globe have been trying to build the bridge between women’s rights and Islam for generations. In Pakistan, Dr. Riffat Hassan and Asma Barlas have made significant contributions to the reinterpretation of Qur’anic texts from a non-patriarchal perspective and have laid down a strong foundation for Islamic feminism in the country. And the story of Afghanistan’s teacher, Islamic scholar and women’s rights activist, Ayesha Aziz , is instructive. Aziz’s successes in advocating women’s rights with Taliban officials by finding common ground in religious values and building relationships of trust underscores the promise that Islamic feminism holds for women’s empowerment in Pakistan.

An immediate next step in fostering gender justice in Pakistan is to build on the work of scholars like Hassan and Barlas, and to publicize feminist narratives about Islam. The longer-term challenge is to systematically address the ever-widening gap between those who understand Islam but do not understand modernity and those who understand modernity but do not understand Islam, as noted by Pakistani-American scholar Fazlur Rahman . Islamic feminism can serve as a starting point by offering a common ground of engagement to both groups, and can help propel the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on its journey to become more gender-equal and, ultimately, peaceful for all.

Related Publications

Toward a Durable India-Pakistan Peace: A Roadmap through Trade

Thursday, June 27, 2024

By: Sanjay Kathuria

Despite a three-year long cease-fire along their contested border, trade and civil society engagement between India and Pakistan has dwindled, exacerbating the fragility of their relationship. With recently re-elected governments now in place in both countries, there is a window of opportunity to rekindle trade to bolster their fragile peace, support economic stability in Pakistan, create large markets and high-quality jobs on both sides, and open doors for diplomatic engagement that could eventually lead to progress on more contentious issues.

Type: Analysis

How Have India’s Neighbors Reacted to Its Election?

Tuesday, June 25, 2024

By: Humayun Kabir; Geoffrey Macdonald, Ph.D. ; Nilanthi Samaranayake ; Asfandyar Mir, Ph.D.

Narendra Modi was sworn in on June 9 for his third consecutive term as India’s prime minister. Public polls had predicted a sweeping majority for Modi, so it came as some surprise that his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost ground with voters and had to rely on coalition partners to form a ruling government. Although India’s elections were fought mainly on domestic policy issues, there were important exceptions and Modi’s electoral setback could have implications for India’s regional and global policies.

Global Elections & Conflict ; Global Policy

What Does Further Expansion Mean for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization?

Thursday, May 30, 2024

By: Bates Gill; Carla Freeman, Ph.D.

Last week, foreign ministers from member-states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) gathered in Astana, Kazakhstan. The nine-member SCO — made up of China, India, Russia, Pakistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan — represents one of the largest regional organizations in the world. And with the SCO’s annual heads-of-state summit slated for early July, the ministers’ meeting offers an important glimpse into the group’s priorities going forward. USIP’s Bates Gill and Carla Freeman examine how regional security made its way to the top of the agenda, China’s evolving role in Central Asia and why SCO expansion has led to frustrations among member states.

Type: Question and Answer

Global Policy

Asfandyar Mir on Balancing Counterterrorism and Strategic Competition

Tuesday, May 21, 2024

By: Asfandyar Mir, Ph.D.

As terror threats emanating from Afghanistan and Pakistan rise, many may see counterterrorism as a distraction from other U.S. priorities, such as competition with China and Russia. But investment in counterterrorism can work “preventively, to shield the strategic competition agenda,” says USIP’s Asfandyar Mir.

Type: Podcast

The rising voices of women in Pakistan

From registering women voters to negotiating rights, women are redefining roles despite resistance from the state, religious institutions, and other women.

SHAHDARA, Pakistan – Bushra Khaliq stood in the middle of a village home, chin up and shoulders back, holding the attention of fifty women around her. Old and young, they wore Pakistani tunics and scarves; some cradled and fed babies, others shushed children who tugged at their sleeves. Sun from the open roof warmed Khaliq’s face as she looked around, holding eye contact with one woman, then another. “Who is going to decide your vote?” she asked. The women clapped and shouted in unison: “Myself!”

Both Sunni and Shia students study at a girls’ school in Minawar, a village near Gilgit in the province of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Bibi Raj, 22, principal of Outliers Girls School in Minawar, graduated with her master's degree in Education in 2018. She teaches biology and chemistry and hopes her students will attend college, even though some of them are already engaged to be married.

Nadia Khan, a 23-year-old Ismaili teacher, sits among her students. Ismailis are known in Pakistan for supporting female education, but they have limited influence outside of the Hunza valley in Gilgit-Baltistan. The only girls’ school in Minawar village, with 24 students between the ages of 14 and 17, still struggles to keep girls in school instead of leaving for marriage at age 15. “It’s a challenge for me,” says Principal Bibi Raj. “All girls should go to school.”

Khaliq, a 50-year-old human rights defender and community organizer, was holding a political participation workshop session, the first of several that day in the rural outskirts of Lahore. The women attendants were local wives and daughters of agricultural laborers. Many were illiterate, though several worked low-income jobs to send their daughters to school. It was the week before Pakistan’s general election, and Khaliq, who runs an organization called Women in Struggle for Empowerment (WISE) , encouraged the women to vote.

Many rural women are not registered for their National Identity Cards , a requirement not only to vote but also to open a bank account and get a driver’s license. In Pakistan, many women in rural and tribal areas have not been able to do these things with or without the card. In accordance with patriarchal customs and family pressures, they live in the privacy of their homes without legal identities.

Yet Pakistan’s July 2018 elections saw an increase of 3.8 million newly registered women voters . The dramatic increase follows a 2017 law requiring at least a 10 percent female voter turnout to legitimize each district’s count. Pakistan has allowed women to vote since 1956, yet it ranks among the last in the world in female election participation.

Teenage girls from Gulmit load up in a van after an all-female soccer tournament meant to promote gender equality in the Hunza valley of northern Pakistan.

All-girl teams from surrounding villages walk onto the field during the soccer tournament.

The Hunza valley in the northern Pakistan borders China’s Xinjiang region and the Wakhan corridor of Afghanistan. The Ismaili Muslims who live there embrace education rates for girls and religious tolerance.

The remote tribal area that borders Afghanistan, formally called the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of northwestern Pakistan, has traditionally been least tolerant of women in public spaces, some women activists say. Yet registration in 2018 increased by 66 percent from 2013. This rise in women’s votes is a victory for women like Khaliq, who are fighting for women’s inclusion and equality in Pakistan, especially among marginalized communities in rural and tribal areas.

Encouraging more women to vote is only the beginning. Women themselves disagree over what their role should be in Pakistani society. The patriarchal, conservative mainstream dismisses feminism as a Western idea threatening traditional social structures. Those who advocate for equality between women and men – the heart of feminism – are fighting an uphill battle. They face pushback from the state, religious institutions, and, perhaps most jarringly, other women.

There are different kinds of activists among women in Pakistan. Some are secular, progressive women like Rukhshanda Naz, who was fifteen years old when she first went on a hunger strike. She was the youngest daughter of her father’s twelve children, and wanted to go to an all-girls’ boarding school against his wishes. It took one day of activism to convince her father, but her family members objected again when she wanted to go to law school. “My brother said he would kill himself,” she said. Studying law meant she’d sit among men outside of her family, which would be dishonorable to him. Her brother went to Saudi Arabia for work. Naz got her law degree, became a human rights lawyer, opened a women’s shelter in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and worked as resident director of the Aurat Foundation, one of Pakistan’s leading organizations for women’s rights. She is also the UN Women head for the tribal areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA.

An Ismaili bride participates in one of many marriage rituals in the Hunza valley. This bride is marrying for love rather than by family arrangement.

The women in Naz’s shelter are survivors of extreme violence whose status as single women makes them highly vulnerable outside of the shelter. When we met, she brought three Afghan sisters whose brother had killed their mother after their father died so he could get her share of the land inheritance after their father died. Naz also had with her a 22-year-old woman from Kabul whose father disappeared into Taliban hands for having worked with the United Nations. The woman had been beaten, kidnapped, and sexually assaulted for refusing marriage to a Taliban member. Women hidden in Naz’s shelter are relatively safe, but outside its walls Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has high incidences of “honor”-based violence. Last June, a jirga (typically all-male tribal council) ordered the “honor” killing of a 13-year-old girl for “running away with men.” At least 180 cases of domestic violence were reported in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2017, according to Human Rights Watch , including 94 women murdered by immediate family.

Others such as Farhat Hashmi represent women from a different perspective. A scholar with a doctoral degree in Islamic studies, Hashmi founded the Al-Huda movement. The group, started in the 1990s, has gained huge traction among upper-middle class Pakistani women as a women’s religious education system that emphasizes conservative Quranic teachings. The Al-Huda schools drew attention after Tashfeen Malik, a former student who became radicalized soon after, carried out a terror attack in San Bernardino, California, in 2015. While there is no proven connection between the Al-Huda movement and any terrorist organization, the group is one of several “piety movements” that has grown in popularity among Pakistani women.

Women of Pakistan’s Wakhi minority make and sell traditional hand-woven carpets in Gulmit village in the Hunza valley.

Zina Parvwen, 52, sits before a display of the Wakhi traditional carpets that she and eleven other women make and sell in Gulmit.

Bibi Farman, a 32-year-old female carpenter, is one of 40 women who work at a carpentry workshop in Karimabad, a village in the Hunza valley. “I am gaining skills,” Farman says. “I am earning money. I support my family and it built up my confidence. Many girls share their problems here. We are a community.”

Women show their hand-embroidered textiles to Tasleem Akhtar, 55, who runs a vocational center in a village near Islamabad. A women’s empowerment organization called Behbud has trained about 300 women who are working here. The women use their earnings to send their children to school.

The role of women in Al-Huda’s teachings is fundamentally different from the position women like Naz and Khaliq are fighting for: Women are taught to obey and submit to their husbands as much as possible, to protect their husbands’ “ honor ,” and never to refuse his physical demands. As Gullalai, director of a women’s organization called Khwendo Kor (“Sister’s Home” in Pashto) puts it, “What they think are women’s rights are not what we think are women’s rights.”

The debate about whether to pursue women’s rights in a secular or religious framework has continued since the 1980s, when progressive feminism first began to gain momentum in Pakistan. Though women’s movements existed in Pakistan from the country’s beginnings, they mobilized in new ways when Zia-ul-Haq’s military dictatorship instituted a fundamentalist form of Islamic law. Under the system, fornication and adultery became punishable by stoning and whipping, murder was privatized under the Qisas and Diyat law (providing a loophole for perpetrators of “honor killings”), and women’s testimony was only worth half of men’s in court.

These laws spurred the formation in 1981 of the Women Action Forum (WAF), a network of activists who lobby for secular, progressive women’s rights. On February 12, 1983, the WAF and Pakistan Women Lawyers’ Association organized a march against the discriminatory laws, only to be attacked, baton charged, and tear gassed by policemen in the streets of Lahore. The date became known as a “black day for women’s rights,” Naz says, and was later declared Pakistan’s National Women’s Day.

Tourists from Karachi pose for a selfie overlooking the Karakoram mountain range in the Hunza valley. The group of young women came to "escape city life," they said.

Since then, Pakistan’s military has grown stronger and more entrenched in its control of both state and economy. The 2018 elections saw the unprecedented inclusion of extremist and militant sectarian groups running for office, including a UN-declared terrorist with a $10 million U.S. bounty on his head. At the same time, hundreds of people were killed or injured by a series of pre-election suicide attacks.

Some conservative movements have become far more popular than the progressive women’s movement. Some scholars explain the appeal of these faith-based organizations as a channel for women to exercise agency and autonomy by pointedly embracing a non-Western form of womanhood. It’s a different definition of empowerment. Its adherents also avoid the shame, pressure, and physical threat that secular feminists regularly face. “They have the support of religion and acceptance in society, so they are in expansion—and we are shrinking,” Naz said.

Days before Pakistan’s general elections, 50-year-old activist and human rights defender Bushra Khaliq encouraged rural women to vote. A longtime campaigner for women’s rights and labor rights, Khaliq has survived social and state-level attacks on her work. In 2017, the Ministry of Interior and home department of Pakistan accused Khaliq’s organization of performing “anti-state activities.” Khaliq took her case to the Lahore High Court and won the right to continue working.

Gulalai Ismail, a 32-year-old Pashtun human rights activist, founded Aware Girls, an organization combatting violence against women, at age 16. The group aims to educate and mobilize girls and women against social oppression, especially in her home province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. At the time of this portrait, Ismail and Aware Girls were charged with blasphemy for undertaking “immoral” activities and for challenging harmful religious traditions.

Gulalai, who chooses to go by one name to protest the custom of taking a man’s name, runs a women’s organization called Khwendo Kor in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. She conducts weekly feminist reading sessions in Peshawar, the capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The meetings bring women teachers, doctors, and nonprofit workers together to read and discuss the intersection of gender, class, economic inequality and nationalism. “Living in this part of the world and being a woman, how can one not be a feminist?” Gulalai said. “There is no other option.”

There is a third group of women in Pakistan who don’t connect with either secular feminism or conservative ideology – women who are just trying to survive, said Saima Jasam, a researcher who focuses on women’s and minority rights in Pakistan at the German Heinrich Böll Foundation . Jasam grew up in a Hindu family that decided to stay in Lahore after partition. She witnessed her parents being stabbed to death in her home when she was 15 years old. “The person who stabbed my father said he’d dreamed that he had to kill Hindus,” Jasam said. Though the rest of her family was in India, Jasam insisted on finishing her studies in Lahore, where she fell in love with a Muslim man and converted to Islam to marry him. A year later, he died in an accident. Jasam was pregnant and lost her child. She was 25 years old. At 27, she began working on women’s issues, eventually writing a book on “honor” killings and doing fieldwork.

Jasam’s way of ignoring criticism and conservative pressure is to focus on protecting the vulnerable. “They are facing a different level of patriarchy: food insecurity, health insecurity. They’re just surviving,” Jasam said. Secular women—which, to secular activists, doesn’t mean anti-religion, but anti-conflation of religion and state—are the ones who have secured legislative change to protect women better over the last 20 years.

Rukhshanda Naz, a lawyer and activist who runs a women’s shelter in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, stands with one of the Afghan women in her shelter. The 23-year-old Afghan woman fled Kabul after being beaten, kidnapped, and sexually assaulted for refusing marriage to a Taliban member. “Women’s solidarity should be without ethnicity or borders,” said Naz. “We want to live a life which our mothers didn’t have a chance and their mothers didn’t have a chance [to live], a life with rights and dignity.”

Gullalai, who is originally from FATA and spends much of her time engaging women in the most tribal and conservative parts of Pakistan, said the gap between feminist beliefs and Pakistani reality requires pragmatic compromise. She works to meet women where they are. It’s easy to convince women that they should have inheritance rights, for example, but there are religious texts which state women should have only half a share. “So women will say, ‘Oh, we want half,’” Gullalai said. Personally, she believes women should have an equal share, but she won’t bring it into conversations in the tribal setting. Gullalai said, “At the moment we are even advocating for half!”

Sometimes Pakistani feminists compromise to engage Jasam’s “third group” of women; other times, those women inspire feminists toward more radical activism.

In the rural Okara district of Punjab province, women have long played a leading role in a farmers’ movement against military land grabs. They have used thappas —wooden sticks used in laundry—to face down brutal Pakistani paramilitary forces that have beaten, murdered, detained, and tortured local farmers and their children. Khaliq openly aligned with this farmers’ movement in 2016, speaking up in solidarity with them. In response, the Ministry of Interior widely circulated a letter accusing her NGO of unspecified activities “detrimental to national/strategic security.”

A memorial to Benazir Bhutto, former Pakistani prime minister, sits at the site of her assassination in December 2007 during a political rally in Rawalpindi, Punjab province. Bhutto was the first woman to rule a democratic Islamic nation and took a stark stance against religious extremism. Throughout her time in politics, she was threatened by the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and local extremist groups.

Members of the Awami National Party (ANP), a leftist Pashtun nationalist party, rally in a rural area of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa during the lead-up to Pakistan’s 2018 election. ANP is one of Pakistan’s most secular, liberal parties. A few days after the rally, ANP leader Haroon Bilous was killed in Peshawar by a suicide attacker. No women were at the rally.

In 2017, Khaliq went to court to defend herself and her organization. Her NGO had been training women to protect themselves against harassment, she argued. How was that detrimental to national security? Khaliq won.

You May Also Like

Why is stomach cancer rising in young women?

Title IX at 50: How the U.S. law transformed education for women

These are the best and worst states for women

Women are Khaliq’s inspiration. “These are ordinary and illiterate women who spend their whole lives in homes, but they stand up and fight against army brutalities,” she says. “They are ahead of the men. I feel my responsibility to go shoulder-to-shoulder with them. Their strength gives us more strength.”

Outside the political-participation meeting house in Shahdara, open gutters spilled onto the village streets, flies buzzing around cows and carts moving through the uneven dirt alleys.

Khaliq first met this group of women six years ago, she said, following her usual method of engaging rural women: knocking on doors one by one, asking for the women, bringing them to weekly meetings, building a sisterhood. In the lead-up to the most recent election, her women’s groups went door-to-door throughout small villages, asking women if they had ID cards and bringing mobile vans to register them if they didn’t. They’d found more than 20,000 women unregistered in one district, Khaliq said, and managed to get identification cards for 7,000 of them.

“Ten years ago, we were not aware of our basic rights. Now we know how to work for our own choices,” said 48-year-old Hafeezah Bibi, standing up in a bright teal scarf. She was the only woman on Shahdara’s local council, which rarely addressed what she called “poor women’s problems”: overflowing garbage dumps, broken sewage systems, and exploitative wages. “They don’t listen to us, but we keep asking and arguing,” she said.

Another woman, Parveen Akhtar, said she’d been stitching shoe straps at home for 300 rupees ($2.45) a day, without knowing what others made or whether she could get a higher wage. After joining the group, she’d learned about labor laws and organizing—and demanded a raise. “I only got 5 rupees higher,” she said, “But we have a long way to go.”

Related Topics

- HUMAN RIGHTS

- FAMILY LIFE

Meet some of the millions of women who migrated recently, risking everything

These women fled Afghanistan. What's at stake for those left behind?

Harriet Tubman, the spy: uncovering her secret Civil War missions

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

This is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality. A new test could change that.

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Last updated 09/07/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Rethinking Pakistan

- > In Search of a Pakistani Feminist Discourse

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Identity, Religion and Radicalisation

- Part II Development, Reform and Governance

- Part III Rights, Repression and Resistance

- Part IV Sex, Gender and Emancipation

- Part V Conflict, Diplomacy and Foreign Policy

- Contributors

- Bibliography

Chapter 20 - In Search of a Pakistani Feminist Discourse

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 January 2022

A burgeoning feminist movement is underway in Pakistan, but it can succeed only when it starts mirroring the makeup of the women and the society for which it operates – and this country is tricky territory for feminists. Open hostility towards feminism persists based on the deliberate misunderstanding put about by conservative politicians and the religious right that feminism is about hatred of men, Western (and therefore alien) values and moral licentiousness. A certain amount of rehabilitation towards the image feminism has to take place in Pakistan before women can truly become cognisant of the perniciousness of the system that they have been conditioned to accept. Pakistan needs a feminism that elegantly marries both the secular and Islamic tendencies because the country, I believe, was created on the basis of both secular and Islamic principles.

Women make up 52 per cent of Pakistan's population, yet even in the twenty-first century many of them are treated as second class citizens. The struggle for women's empowerment is well underway in the country, but much of it is based on economic factors and financial necessities: women are touted as the missing factor in Pakistan's economy and their inclusion in the labour force is seen as the magic bullet that will fix both the country's economy and their unequal standing in the society. But that is not the whole story.

Deliberate feminist action is the mechanism that Pakistan desperately needs to address the gaping disparity between men and women. But before that, certain theoretical dilemmas must be resolved. First, is feminism compatible with Pakistan's official religion, Islam? Second, how can Pakistani feminism overcome entrenched cultural traditions stemming from the patriarchal nature of our particular sociocultural makeup? Third, what should such a feminism look like? This chapter attempts to answer these questions, first by contextualising the problem of gender inequality and illustrating its scope and then by presenting an argument as to why Pakistan needs feminism to embark on the road to progress and prosperity. The latter part of the argument would be approached through real-world examples coupled with a personal testimony.

Is Islam Compatible with Feminism?

Islam embodies many of the principles that feminism fights for: equality, dignity and respect for women.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- In Search of a Pakistani Feminist Discourse

- By Bina Shah

- Bilal Zahoor

- With Raza Rumi

- Book: Rethinking Pakistan

- Online publication: 20 January 2022

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Entanglement of Secularism and Feminism in Pakistan

Amina Jamal is associate professor of sociology at Ryerson University, Toronto. She has authored a monograph, Jamaat-e-Islami Women in Pakistan: Vanguard of a New Modernity? (2013). She writes in the areas of women, Islam and modernity, transnational and postcolonial feminism, violence against women, and Muslim women’s struggles in Pakistan and Canada.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Amina Jamal; The Entanglement of Secularism and Feminism in Pakistan. Meridians 1 October 2021; 20 (2): 370–395. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/15366936-9547932

Download citation file:

- Reference Manager

In many Muslim-majority societies, including Pakistan, liberal progressive subjects who espouse feminism and gender equality do so through the language of universal human rights and political secularism. This brings them into conflict not only with anti-secular rightwing conservatives within their own societies but also with progressive scholarly critics of secularism in other contexts. To clear the space for a nuanced understanding of feminist secularism in Pakistan, the author examines a unique style of politics that may be described as “secular” among middle-class Muslim women interviewed by the author in Karachi and Islamabad. She argues that the espousal of secularism by feminists as a political cultural discourse in South Asia can initiate a politics that challenges hegemonic notions of self, community, and nation that are gaining strength in Pakistan. This position militates against simplistic understandings of secular feminism in this Muslim-majority society as the politics of colonized subjects or as a hegemonic nexus for reproducing the discursive power of Eurocentric and universalist discourses.

Client Account

Sign in via your institution.

Advertisement

Citing articles via

Email alerts, related articles, related topics, related book chapters, affiliations.