Why Does Coaching Work? An Evidence-Based Perspective

Coaching facilitates psychological capital..

Posted December 27, 2022 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Coaching?

- Take our Burnout Test

- Find a life coach near me

- Leader and executive coaching is a common approach to self-development in the workplace.

- A common question asked by those considering coaching is how exactly it changes one's behavior.

- Evidence across social science research suggests that the reason coaching changes behavior is through what's called psychological capital.

Those of us who believe in the power of coaching sometimes have a hard time explaining why exactly coaching is helpful. Whether we’re the coach or the coachee, we tend to draw from one-off stories of success to explain its utility. This isn’t enough. Those interested in coaching, being coached, or implementing organization-wide coaching programs need to be able to explain what exactly is changing in the minds and hearts of coachees as they spend time interacting with coaches.

Research has finally begun to make this connection clearer. Across several recent studies, findings suggest that coaching facilitates what’s called “ psychological capital ” (PsyCap for short). In what follows, I outline the four dimensions of PsyCap and explain why coaching has the capacity to facilitate this positive development state.

Self-Efficacy

The first dimension of PsyCap is self-efficacy , which is the belief and confidence in one’s capabilities. Self-efficacy increases when individuals set goals as well as when they reflect on successful experiences. Indeed, a key part of the coaching process entails developing goals with coachees, holding them accountable for goal pursuit, and reflecting upon and celebrating successes stemming from goal attainment.

The second dimension is hope, a motivational state characterized by a sense of agency toward achieving goals. Hope manifests as two interrelated components: having a sense of agency and an understanding of how to enact change. Coaches help in both regards. Coaches encourage and promote solution-focused thinking, helping coachees focus on what’s feasible and how to approach and implement change. Coaches are also responsible for ensuring that coachees engage in self-reflection, and in doing so, it ensures that coachees maintain a sense of determination by focusing on possible pathways to success.

The third dimension is optimism , which entails a positive attribution about the future. As stated by PsyCap researchers Youssef and Luthans, optimism entails having a “leniency for the past, appreciation for the present, and opportunity seeking for the future.” Research suggests that coaches unlock this mindset while working with their coachees through interventions that focus on being one’s best possible self. We have a tendency to get discouraged when things get tough, but coaches have the capacity to put things back in perspective.

The last dimension is resilience , which is the ability to bounce back quickly and effectively from adverse circumstances. Resilience is present when one proactively seeks out helpful resources as well as positively manages their circumstances. Coaches facilitate both behaviors in that they act as a consistent and stable sounding board as well as help coachees cope through cognitive reappraisal.

Explaining Why Coaching Works

No longer will coaches or coachees need to resort to anecdotes to explain the value of coaching. The evidence is clear. The reason coaching leads to success is that it facilitates psychological capital, a positive psychological resource that coachees can apply to their day-to-day work experiences. It is this psychological capital that acts as the linking mechanism between coaching interventions and a host of beneficial outcomes, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job performance.

Scott B. Dust, Ph.D., is a management professor at the University of Cincinnati. His writings offer evidence-based perspectives on leading oneself and others.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Coaching for Change

- Richard E. Boyatzis,

- Melvin Smith,

- Ellen Van Oosten

How to help employees reach their potential

Whether you’re a boss, a colleague, or a friend, you can help the people around you make important life-enhancing changes. But the way to do that isn’t by setting targets for them and fixing their problems; it’s by coaching with compassion, an approach that involves focusing on their dreams and how they could achieve them. Instead of doling out advice, a good coach will ask exploratory, open-ended questions and listen with genuine care and concern. The idea is to have coachees envision an ideal self (who they wish to be and what they wish to do), explore the real self (not just the gaps they need to fill but the strengths that will help them do so), set a learning agenda, and then experiment with and practice new behaviors and roles. The coach is there to provide support as they strive to spot their learning opportunities, set the groundwork to achieve change, and then see things through.

Change is hard. Ask anyone who has tried to switch careers, develop a new skill, improve a relationship, or break a bad habit. And yet for most people change will at some point be necessary—a critical step toward fulfilling their potential and achieving their goals, both at work and at home. They will need support with this process. They’ll need a coach.

- RB Richard E. Boyatzis is a professor in the departments of Organizational Behavior, Psychology, and Cognitive Science at the Weatherhead School of Management and Distinguished University Professor at Case Western Reserve University. He is a cofounder of the Coaching Research Lab and coauthor of Helping People Change (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

- MS Melvin Smith is a professor of organizational behavior at Case Western. He is a cofounder of the Coaching Research Lab and coauthor of Helping People Change (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

- EO Ellen Van Oosten is an associate professor of organizational behavior at Case Western. She is a cofounder of the Coaching Research Lab and coauthor of Helping People Change (Harvard Business Review Press, 2019).

Partner Center

Coaching Philosophy: What It Is and How to Develop Your Own

Fortunately, most coaches get into the business to serve others, and with that heart of service comes a pathway to a personal coaching philosophy.

Personal values and integrity in the field are essential steps in understanding the benefits that coaching brings to the world.

If you’re lucky, your trainer will help to develop this coaching philosophy well during training. Coaches are responsible for how they show up to serve their clients, and being mindful and self-aware is an integral part of that service.

Come along to read more about coaching philosophy and how it can add value to any coaching practice.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is a coaching philosophy, developing your coaching philosophy, 3 examples of coaching philosophies, a look at some examples of life coaching philosophy, inspiring quotes, a take-home message.

Having a well-defined approach for the way each client is served is a crucial part of being a coach. As coaching is used in a wide variety of areas, so too will there be a wide variety of coaching philosophies. The development of a coaching philosophy is a way to set expectations for the coach and the client.

A coaching philosophy is a coaching tool to help guide coaches in their process of coaching. Having a philosophy gives a coach clear guidance on the objectives that should be pursued and how to achieve them. While adhering to values, a coach can make consistent decisions and broader life coaching questions by sticking with their philosophy.

The International Coaching Federation (ICF) has a code of ethics for credentialed coaches, and the coaching philosophy is a part of this code. True coaching involves holding space for a client to allow their personal growth to lead the coaching conversation. Coaches are not advisers, but rather active listeners who are not wedded to the outcome of any coaching conversation.

Becoming well versed in the ICF Code of Ethics will aid coaches in developing the personal standards by which their clients are well served.

A coach’s stand is a great way for a coach to begin effectively determining their coaching philosophy. Through utilizing the commitment portion of the coach’s position, what one stands for clears the way for a well-served client. Unconditional positive regard is a big part of this, but a clear philosophy can be fully developed through a deep understanding of core values.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

The development of your coaching philosophy should start with core values. Do some self-evaluation with values clarification tools , to discover your core values.

Your coaching philosophy should reflect your values, moral standards as well as your integrity. To show up as your best self for your clients, you should have a deep understanding of why you got into the profession in the first place.

Here are a few questions to ask when discovering that “why.”

- What is my motivation for coaching?

- What type of coach do I want to be?

- Why is coaching the right fit for me?

- What is it that I would like to achieve with my clients?

- What will I achieve for myself?

All coaches tells themselves stories that may bring forth the commitments that will undermine the effectiveness of the coaching. Self-awareness in coaching is vital in delivering effective service to clients.

Here are a few examples of what a coach might unintentionally be committed to that hold them back from their philosophy and power as a coach (Lasley, Kellogg, Michaels, & Brown, 2015).

- The need to be admired

- Ensuring the process is being done “right”

- The need to highlight personal knowledge

- Being consumed with the client’s level of comfort

- Being too polite

To be an effective coach, one must step into the shoes of someone whose focus is not on the self. Most coaching philosophies are “others” focused, which allows for coaching environments where creativity and collaboration can flourish.

Here are a few questions to ask yourself in developing that coaching stand.

- Can my clients expect that I bring my best self to each and every session?

- Do I speak to my client’s excellence and accept nothing less than that?

- Am I problem solving? Or am I tapping into my client’s resourcefulness?

- Are the coaching questions I ask in tune with the client’s agenda?

- Am I actively listening ?

- Am I in tune with my intuition?

- Am I bringing my whole self to each and every coaching conversation?

When a coach chooses the style in which they’ll serve their clients, there are perspectives on growth that must be acknowledged. The model or personal style of coaching can be developed by answering these questions. Expand upon the training you’ve already received to more intensely focus on the personal integration necessary for effective coaching to occur.

- What type of client will you choose to serve?

- What personal view of the process of change do you have?

- What objectives does this personal view require for growth?

- How is accountability established for yourself and your client?

- What personal standards will you bring to each client?

A coaching philosophy will directly impact the coach, their clients, and the world around them. Developing this philosophy allows for a type of “standard of care.” Though each conversation will be creative and unique, having a philosophy for the approach will allow the coach to show up in the same way for each person served.

Coaching conversations can shift and change direction. A coach who deeply understands their coaching philosophy can approach each of these conversations with curiosity and ensure their values are respected in the process. When fully in service, a coach will create space for a client to explore possibilities fully.

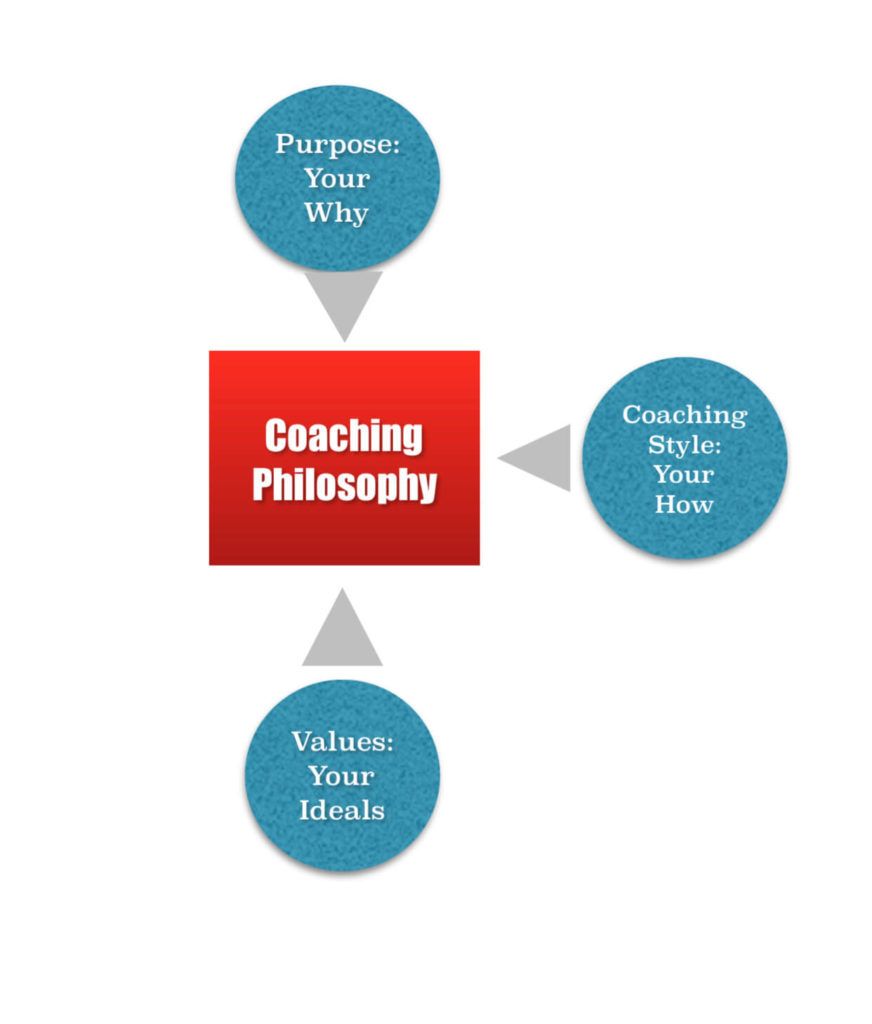

Here is a graphic to follow in developing your coaching philosophy.

1. Identify your values.

- List three or more specific values. For example: mutual respect, organization, and integrity.

2. Develop a personal belief system by developing actions for each value.

- Mutual respect — Always approach clients with unconditional positive regard.

- Organization — Always be organized with meeting times, administration, and keeping track of progress and discussions.

- Integrity — Always honor the trust and confidence of your clients.

3. Build a mission statement from the answers to the second part on the path.

To be a source of open-minded support for clients as an organized, safe, and honest coach, providing collaborative and creative space to explore personal growth.

1. Sports coaching

When you say the word ‘coach’ to most people, an image of someone with a clipboard and a whistle often comes to mind.

Though athletic coaches have an alternative role to other types of coaches, many of the philosophies are similar. A coaching philosophy may be developed by acknowledging the objectives of the athletes and the team, followed by the type of coach you want to be, and completed with your personal ideals.

The head football coach of the LSU Tigers, Ed Orgeron, developed his coaching philosophy by channeling Pete Carroll of the NFL (Crewe, 2016). The two are wildly successful leaders of young men in the sport. They are clear about why they are serving their athletes and how they are going to build their team into the best possible versions. They stay true to their values in the process of doing so.

Coach Orgeron’s use of Carroll’s mantra, “ Always Compete,” highlights his mentality toward coaching. He considers himself always improving and learning from mistakes. He brings his whole self to how he coaches, and the results are evident in LSU’s 2019 record. Mr. Orgeron’s coaching philosophy has played a large part in the team’s success.

Prefer Uninterrupted Reading? Go Ad-free.

Get a premium reading experience on our blog and support our mission for $1.99 per month.

✓ Pure, Quality Content

✓ No Ads from Third Parties

✓ Support Our Mission

2. Executive/Business coaching

The relationship between executive coaches and the businesses they serve should be similar to an individual coaching relationship. The personal coaching philosophy can serve as a mission statement for the way a coach approaches coaching in business.

Creating a clear vision of the type of client served and the way they’ll be served will allow the process of coaching to reach exponential growth.

Here are some examples of coaching philosophies from several coaches established in the field:

Coaching is a relationship of equals, where accountability for moving oneself forward lies with the individual being coached, and responsibility for providing the insightful and challenging coaching to support that happening for the client lies with the coach.

Dave McKeon

We exist to make the world a better place – one courageous conversation, one liberating truth, one great leader at a time. We partner with individuals, teams and organizations to help leaders and their teams enjoy the journey.

Greg Salciccioli of Coachwell.com

3. Health coaching

Everyone’s health is important. What health coaches hold true is that nobody is the same. Coaching philosophy in this area of coaching must acknowledge that a “one-size-fits-all” mentality won’t work for improving health or supporting someone going through a health crisis.

Here is an example of a possible health coaching philosophy that could serve clients well.

They recognize that everyone is unique and different, so no one diet, exercise, or way of life will work for everyone. Health coaches tailor recommendations and plans for each individual based on the individual. It’s personalized information for you.

How to create your own coaching philosophy – Coach Ajit x Evercoach

Life coaches are similar to personal trainers. There is an element of motivation that is harnessed within a positive coach–client relationship. A life coach’s philosophy will usually align with the ignition of personal responsibility and action toward desired outcomes.

Life coaching can be seen as an umbrella term for coaching. Beneath this umbrella, life coaches can coach in the following areas: personal growth, career, business, health, and relationships, among others. It is a powerful process through trained, skillful interpersonal interaction.

Motivation is followed by strategic planning, which is generated by the client through open-ended questioning. Once a plan is forged, a life coach will then create space to explore how the client wants to be held accountable. The process can be therapeutic, though it is not therapy. It can also bring clarity and greater illumination of purpose.

The Flourishing Center trains positive psychology coaches who may serve others as life coaches, in addition to other areas of coaching. The philosophy taught in this Applied Positive Psychology Coaching certification is one of “purna.” The word means ‘complete,’ and in this training, it is the understanding that both the coach and the client are whole and resourceful. The philosophy taught in this certification program is as follows:

I have within me all that I need. All that I have, I need. They have within them all that they need. All that they have, they need.

This philosophy allows for trained coaches to view clients as whole and resourceful. It keeps the coach working in an approach that is not advising or mentoring but instead attached to intuitive questioning.

This philosophy enables the coach and client to create a collaborative space for personal growth. It allows coaches to adhere to ICF core competencies and stick to the ICF Code of Ethics with a mindset that can approach each client in the same way.

Each client is seen as the expert in their own life. With mutual respect, integrity, and commitment, coaches can serve their clients in reaching their best selves, as determined by the clients themselves. Not all life coaches are created the same, and a solid coaching philosophy will make all the difference.

This informative article outlines the differences between life coaching and positive psychology coaching .

At Positive Acorn , coaches are offered training in developing a personal coaching philosophy. Though the coaching profession is highly unregulated, training opportunities adhering to ICF standards are creating quality in the profession. Coaches who are taught to develop their personal coaching philosophy will serve their clients with increased self-awareness, confidence, and ethical integrity.

Here are some principles that every coach, in every modality, should hold true for themselves and their practice:

- Living life well is a responsibility to the gift of life itself. Purpose is found in the pursuit of a life well lived. Serving others in this pursuit should be the foundation of every coaching conversation.

- The pursuit of a well-lived life cannot come at the expense of another. The pursuit of our personal best should never deprive another of the pursuit of theirs.

- Coaching does not exist to change or fix others. It is about helping others become fully functional in the pursuit of their higher selves in any arena.

- Life well lived requires interconnection. To achieve it, one must serve others in pursuit toward their best selves. Meaning and purpose are illuminated when this service releases ego in favor of abundance and calling.

Related: Mental Health Coaching Software Solutions

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

The only place that success comes before work is in the dictionary.

Vince Lombardi

A coach should never be afraid to ask questions of anyone he could learn from.

Bobby Knight

If we were supposed to talk more than we listen we would have two mouths and one ear.

You must expect great things of yourself before you can do them.

Michael Jordan

The first thing successful people do is view failure as a positive signal to success.

Brendon Burchard

A life coach does for the rest of your life what a personal trainer does for your health and fitness.

Elaine MacDonald

If you enjoyed these, we have 54 more inspiring Coaching Quotes for you to enjoy.

When a coach develops and embraces their personal coaching philosophy, fear becomes irrelevant. A coach who embodies the principles of leadership that allow their clients to show up at their best will serve to improve the world around them. A coach who knows and lives with their values will show up for clients at their best for every conversation.

Everyone deserves the gift that is the creative process of coaching. It opens people to their potential and ignites them in that pursuit. When searching for a coach, be sure to ask them about their coaching philosophy.

Thanks for reading!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Crewe, P. (2016, October 30). Building a program in his own image. SBNation . Retrieved from https://www.andthevalleyshook.com/2016/10/30/13401740/building-a-program-in-his-own-image-how-ed-orgeron-is-flexing-pete-carroll-s-philosophies-at-lsu

- Lasley, M., Kellogg, V., Michaels, R., & Brown, S. (2015). Coaching for transformation . Discover Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you so much for this wonderful and insightful article. I have much to think about and consider.

This is an excellent article and I find myself agreeing with a lot of points made by Kelly. I think it is essential for every coach ask WHY when they think of becoming a coach. The drive, motivation and ambition behind those thoughts are key. It could also help to take some assessments and determine if they are on the right track. Another point over coaching philosophy is it helps potential clients realise who are going to interact with and the benefits they will get along with assurance of safe environment they need to learn and grow.

Kelly Miller what is your coaching philosophy? Thank you.

Loved reading this, super helpful! Thanks so much for sharing <3

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Become an ADHD Coach: 5 Coaching Organizations

The latest figures suggest that around 1 in 20 people globally has ADHD, although far fewer are actively diagnosed (Asherson et al., 2022). Attention-deficit hyperactivity [...]

Personal Development Goals: Helping Your Clients Succeed

In the realm of personal development, individuals often seek to enhance various aspects of their lives, striving for growth, fulfillment, and self-improvement. As coaches and [...]

How to Perform Somatic Coaching: 9 Best Exercises

Our bodies are truly amazing and hold a wellspring of wisdom which, when tapped into, can provide tremendous benefits. Somatic coaching acknowledges the intricate connection [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (54)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (27)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (46)

- Optimism & Mindset (35)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (48)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (20)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (40)

- Self Awareness (22)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (33)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (35)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

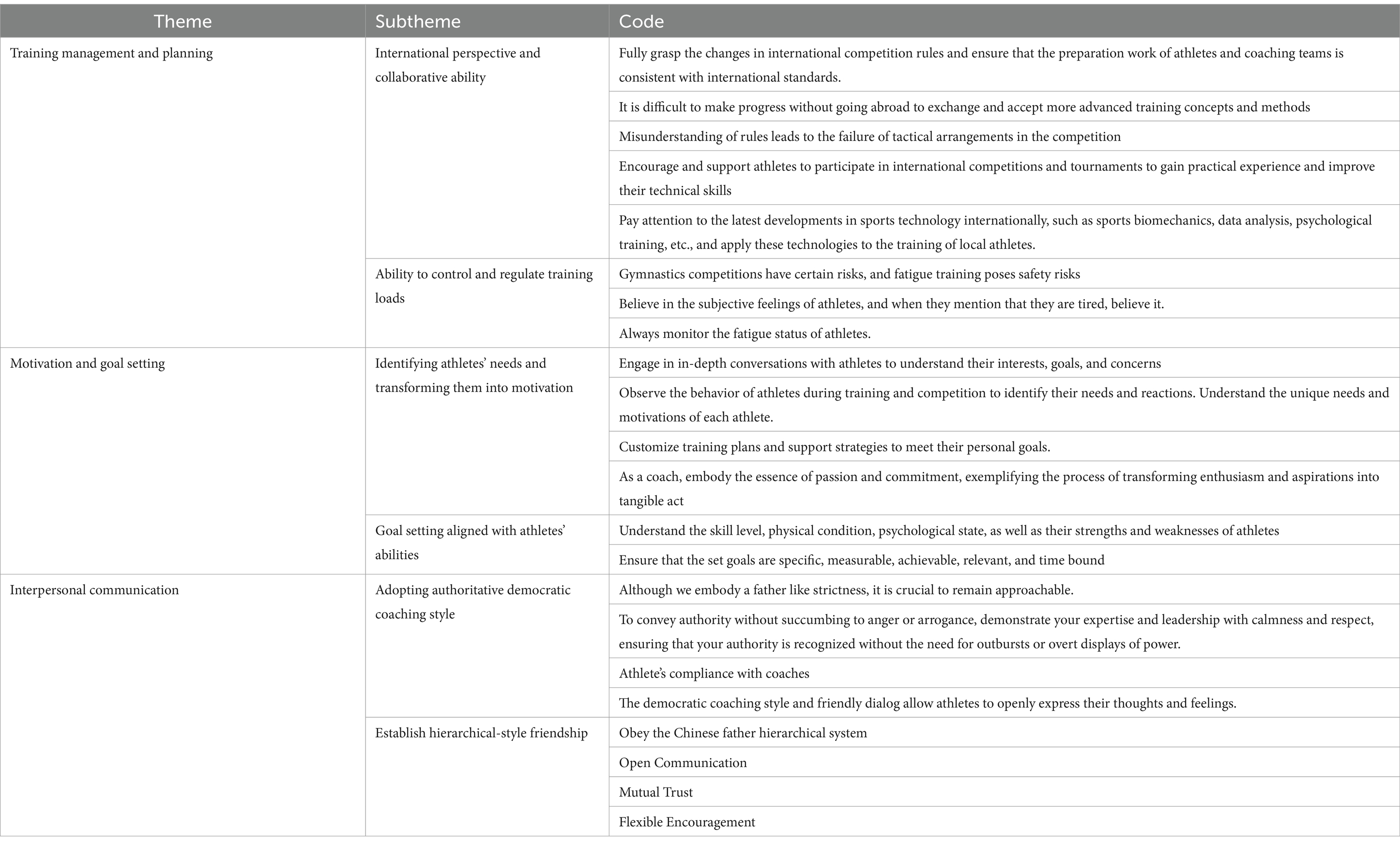

Coaching Experience in Sport Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

In sports, coaching has been fundamental tool managers use to enhance the development of team members. Each coach has given principles and ethics they utilize to achieve the desired outcome. Before commencing the training practices, the experienced must identify key areas that require improvement. Upon identifying the personal needs of a player, the manager formulates the most appropriate techniques that will enable the respective players to gain the necessary professional development. Since teams consist of many individuals, the coaches usually employ various coaching styles, which include democratic, autocratic, and holistic, based on the objective intended to be achieved. Despite the number of players in the team, sports managers ensure each person is respected and treated with the utmost respect. The aim is to make sure the possible ego of the coach remains invisible and the interest of the players is met. The aspect of coaching is an all-around practice that requires the leaders to have different abilities, including motivating, advising, analyzing, and coordinating relevant training programs to meet the development needs of all players in the team.

My Experience with Rugby Team Coaches

At the age of 15 when I was in grade 10, I developed an interest in playing rugby. The school head coach was one of the educators with whom I interacted frequently during class lessons. Following my physical fitness and the urge to enroll in the team, I applied for the chance to join division three of the rugby team. During this time, I had limited skills and competencies required to be an excellent player. In the category, several other individuals did not have the relevant abilities as well. The school had three coaches responsible for the training and development of each of the teams. After some duration and subsequent tests, I managed to break through to division two and then to the main team where I became one of the recognized players. The success of the processes was significantly influenced by the various head coaches. They undertook different roles and commitments to ensure they impart relevant skills to enhance the professional growth of each player. The managers used various coaching techniques that allowed the development to be easier and more achievable.

Coaching Process

Since coaching entails a series of events, the leaders ensure that the players derive maximum professional development to enhance their practices. Generally, it was the duty of the head coach to ensure all the multi-disciplinary approaches are utilized together to facilitate effective engagement. Before setting the goals and objectives for the team, the frontrunner used to take a close observation of each player, especially during training sessions (Sullivan et al., 2021). Afterward, the individual team member was contacted by the trainers to discuss the possible areas that require immediate adjustments. The coaching process was deeply dependent on the philosophy and coaching ethics used in the team.

Coaching Philosophy

The team’s head coach had an outstanding coaching philosophy that applied to the whole training program. According to the manager’s idea, he believed that knowledge and skills are transferable from one person to the other (Cahill, 2022). Based on this perspective, the frontrunner maintained that through effective coaching practices, using appropriate and reliable approaches each player has the potential to improve their talents in sports. Furthermore, the manager acknowledged that through playing games, there is strong character development and confidence which is essential for the growth of an individual. The key components of the philosophy included the objective, the technique used to coach players, and the principles applied.

Before commencing the training session, the coach used to come up with an already prepared objective that the team must aim towards. The trainer first communicates his purpose and expectations once the practice is over. To warrant that the training program is conducted effectively, the manager ensures the atmosphere is positive and accommodating for all the players and the support staff. The approach proved effective because each team member understood the primary reason for the coaching exercise, and thus they worked accordingly towards achieving them. For instance, when engaging in physical activities, the coach always alerted players before preparing them psychologically. The technique proved vital in developing the required attitude for participating in the game. Therefore, it was important to set a clear objective and make it known to the players to facilitate their concentration and commitment to professional development.

To have an effective coaching process, several principles must be applied to facilitate engagement. By definition, sports coaching is known as the training that focuses on individual improvement and that of the whole team members while considering both specific and general performances. Some key principles the rugby coach applies are an emphasis on behaviors, proper order during the training session, rapid correction and instructions, provision of immediate feedback, and use of questions and clarifications. While relying heavily on the stated values, the manager made it easier to handle any possible challenge that could occur to team members. Players as well adapted to the approach, which further simplified the process and created harmony and deep understanding amongst the trainees and the staff members.

Coaching Ethics

Sports attract the interest of individuals from different cultural backgrounds and have varied perspectives. To coordinate and maintain an effective team, coaching morals is a necessary tool. During my time with the school rugby team, the head coach was always applauded, following the respect he accorded the players and the supporting staff. The manager understood that people have different values and beliefs. Furthermore, he considered role differences, ethnicity, age, language, sexual orientation, origin, and socioeconomic status to ensure each player is not treated differently from the others based on attributes (Sabzi et al., 2022). The team reported no case of prejudice and immoral conduct portrayed by the head coach and the assistant. He valued the rights and dignity of all participants, which made the training environment welcoming and accommodating for the various players. In addition, the management set several rules that guide participants’ behaviors in and out of the training sessions. Most of the time, the team was encouraged to respect and uphold practices that embrace moral conduct. For instance, performers were frequently advised to take responsibility, remain fair and apply integrity in every situation they might encounter.

My Experience as a Sports Coach

I have been involved in coaching activities engaging people from different groups, ages, clubs, and gender. I have been exposed to the practice for a couple of years, leading to significant experience in the field. Currently, I am training girls below the age of 16 years to touch rugby and contact rugby as well. In addition, I am the chief instructor for Kids Outdoor Adventure Company, where I coach boys and girls between the ages of 6 to 12 years. Furthermore, I am a certified personal trainer and a CrossFit coach. The mentioned involvements have given me relevant encounters in coaching practices. Since I have been dealing with different individuals, I opted to use the long-term athlete development model as a tool to enhance the ability to improve specific and general improvements among the groups I train.

Long-Term Athlete Development

The long-term athlete development (LTAD) model is a framework created to enhance the quality of physical activity in sports and to allow the players to fully realize their potential and possible ways of exploring them effectively. Coaching is a dynamic program that requires the coach to constantly keep formulating and implementing new training methods that best suit the needs of the performers being trained (Costa et al., 2021). To ensure all my players in their respective groups attain their potential, I employed the LTAD approach to establish the required solution. By definition, LTAD is a properly planned and progressive system that assists in developing individual players. The tool is essential, especially for coaching juniors who are still undergoing various body developments. I used the LTAD to know what to do at any stage of performers’ advancement to enhance their engagement in healthy physical activities. It further provides solutions for handling the players with the talent and drives to succeed in games.

In general, LTAD aims to provide what seems best for the team throughout the training period. It promotes a positive experience for the participants, limiting possible shortcomings that might hinder the engagement of players in physical activities. I adopted the use of the LTAD model because it is applicable in all stages, right from childhood to adulthood. Being that I am dealing with teenagers and some adults, the system provides a proper approach to handling each group effectively. The LTAD framework has seven critical stages that give the coach a platform to guide the training, participation, and recovery process during the involvement (Costa et al., 2021). LTAD is useful since it recognizes involvement and performance-oriented tracks in sports. In addition, the model encompasses fun-based physical literacy necessary for teams aged between 6 to 12 years. The key phases that are making coaching practices include active start, fundamentals, learn to train, train to train, train to compete, training to win, and active for life.

Before applying the LTAD model, as a coach, I considered several factors to ensure that participation, training, and competition were successful. The aspects include physical literacy, specialization, trainability, age, emotional development, periodization, competition, system alignment, excellent task time, and continuous improvement. Each of the mentioned elements significantly benefits the participants and ensures they advance their specific and general physical, intellectual, and mental development.

Periodization Planning

When conducting training activities, I have depended on periodization planning to ensure I deliver the services on time. Since the coaching process entails different activities, it is important to structure and formulates the right period for each training exercise. In most cases, I break the coaching activities into components to be done in sessions, days, and weeks. The approach enables me to be situation specific whereby I bring the required training to enhance the necessary improvement in the team.

Goal Setting

Generally, the participants have different abilities and potentials in the team. To ensure all the performers are engaged and improve their professional development, I create objectives that cover process, performance, and outcome. This is because coaching is a sequential program geared towards unlocking the potential of each player in the team (Cronin et al., 2022). When making developing the goals, I ensure they are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. The technique has made it easier to impart new skills to the participants in an effective manner.

Coaching Roles and Responsibilities

Coaching is an involving practice that comes with several responsibilities to be performed. Generally, team managers are responsible for planning, organizing, and providing different sports programs to enhance the physical fitness of the team members (Cho et al., 2021). Some of the key roles I play include teaching performers various relevant skills to enhance their abilities in rugby. Similarly, I train different tactics and techniques that players can use during competition. Apart from focusing on physical development, I frequently monitor and promote the overall performance by encouraging the individual participant and issuing positive feedback. In addition, I evaluate and identify the strengths and weaknesses of team members to plan for needed adjustments. Since health is a concern when it comes to sports, I advise the performers and their parents on ways to maintain a good lifestyle throughout their life. Other activities are creating appropriate training programs that suit the demands of players and other support staff.

Coaching Styles

As a coach, the most fundamental aspect of coaching is the style being used. When the approach is ineffective, the overall outcome of the involvement will be insignificant. It is necessary to apply the style that best tackles various cultures and behaviors that might prevent the development of each player (Samson & Bakinde, 2021). I have been using the democratic style to enhance the training of teams. The technique is aimed at making the athletes contribute to every aspect of the training program (Kim et al., 2021). Since I deal with people from different age groups, I usually apply the method to individuals aged 12 and above because they understand what is appropriate for them. The coaching technique enables performers to focus on the objectives outlined by the training program which is essential for their physical development.

Teaching Skills

Coaching a team focuses on skill development and each performer is required to gain the necessary abilities that improve their talents. I subject the players to six levels of training to enhance their competencies in sports. Initially, the player learns the relevant skill by engaging in the learning process (Newman et al., 2021). It is then followed by the aspect of skill mastery through a continuous repeat of the technique. The third phase encompasses adding speed to the already known skill to enhance faster execution. The next step is adding fatigue to enable the participants to understand the impact of tiredness on their accuracy and quality. The fifth stage involves adding pressure to make sure the player can apply their abilities when under pressure. The last level entails decision-making; the performer must be able to make the right decision fast during the execution process.

Coaching is an effective process that allows coaches to teach the players relevant skills to enhance their professional development. It is fundamental for the trainers to understand the needs of each performer before planning and structuring the required training programs. Coaching philosophies and the whole process is vital in ensuring the expected outcome is achieved. By applying the LTAD model, it is easier for the coach to provide proper training for the participants while considering various factors such as age, trainability, and physical literacy. In addition, the coaching style promotes the ability of trainees to execute the instructions. The democratic approach has proved player-centered thus making them remain active.

Cahill, G. (2022). Coaching philosophy:” Why we do things the way we do?” ITF Coaching & Sport Science Review , 30 (86), 7-9.

Cho, H., Kim, S., & Lee, Y. H. (2021). Sport coaches’ positive emotions, task performance, and well-being: The mediating role of work satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching , 16 (6), 1247-1258.

Costa, M. J., Marinho, D. A., Santos, C. C., Quinta-Nova, L., Costa, A. M., Silva, A. J., & Barbosa, T. M. (2021). The coaches’ perceptions and experience implementing a long-term athletic development model in competitive swimming. Frontiers in Psychology , 1626.

Cronin, L., Ellison, P., Allen, J., Huntley, E., Johnson, L., Kosteli, M. C., Hollis, A., & Marchant, D. (2022). A self-determination theory based investigation of life skills development in youth sport. Journal of Sports Sciences , 40 (8), 886-898.

Kim, S., Park, S., Love, A., & Pang, T. C. (2021). Coaching style, sport enjoyment, and intent to continue participation among artistic swimmers. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching , 16 (3), 477-489.

Newman, T., Black, S., Santos, F., Jefka, B., & Brennan, N. (2021). Coaching the development and transfer of life skills: A scoping review of facilitative coaching practices in youth sports. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology , 1-38.

Sabzi, A. H., Golzadeh, F., Aghazadeh, A., & Heidarian Baei, E. (2022). Explaining of correlational model of organizational ethical culture with professional ethics in sport coaches. Sport Psychology Studies (ie, mutaleat ravanshenasi varzeshi) , 11 (39), 195-218. Web.

Samson, A. B., & Bakinde, S. T. (2021). Relationship between Coaches’ Leadership Style and Athletes’ Performance in Kwara State Sports Council. THE SKY-International Journal of Physical Education and Sports Sciences (IJPESS) , 5 (1), 91-104. Web.

Sullivan, M. O., Woods, C. T., Vaughan, J., & Davids, K. (2021). Towards a contemporary player learning in development framework for sports practitioners. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching , 16 (5), 1214-1222.

- The Principle of Specificity in Sports

- Athlete Development: Early and Late Specialization

- Sports Coaching Philosophy and Types

- Leadership in the "Invictus" Movie

- Main Sports in Australia

- Detrimental Effects of Skateboarding Ban

- Juggling: The 4-Week Motor Learning Intervention

- Personal Leadership Philosophy in the Sports Industry

- The Case of Gregg Popovich Analysis

- The Pandemic Impact on Sport in New Zealand

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, August 19). Coaching Experience in Sport. https://ivypanda.com/essays/coaching-experience-in-sport/

"Coaching Experience in Sport." IvyPanda , 19 Aug. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/coaching-experience-in-sport/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Coaching Experience in Sport'. 19 August.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Coaching Experience in Sport." August 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/coaching-experience-in-sport/.

1. IvyPanda . "Coaching Experience in Sport." August 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/coaching-experience-in-sport/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Coaching Experience in Sport." August 19, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/coaching-experience-in-sport/.

Becoming An Effective Coach Essay

The athletecoach relationship has an important role in the athlete’s development, both as a performer and as a person (Jowett). As a performer, having a positive relationship with your coach helps build self confidence immensely while performing. Trusting the coach and what they are teaching will have a more positive effect on performers than those who don’t trust their coach. Not only does a positive coach relationship help as a performer, but also as a person. Coaches can teach many important concepts about becoming an incredible athlete, but also an incredible person.

Another essential aspect of a successful team is commitment and communication. Jeanie Molyneux researched a team in Northeast England on how and why their team works so well together. Although there were many brief components to making this team successful, the two main themes that emerged from this study were: commitment of each athlete and communication within the team. Coaches need to inform their athletes of the commitment that is going to be required to be on a team. Before athletes join a team, they need to realize there are many things they need to be willing to sacrifice.

Athletes who fully commit themselves are willing to give up certain things that may seem important at the time, but aren’t as important as what they are trying to accomplish in the long term. Just as it is for athletes, the coach needs to be entirely committed to their team as well. Coaches who aren’t fully committed will not produce a successful team and will eventually just give up coaching. For example, approximately 35 percent of swim coaches discontinue their job because they say coaching is to consuming and demanding. Before coaches commit to their job, they need to consider everything necessary for coaching and fully commit themselves.

To export a reference to this essay please select a referencing style below:

Related essays:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Future of Coaching: A Conceptual Framework for the Coaching Sector From Personal Craft to Scientific Process and the Implications for Practice and Research

Jonathan passmore.

1 CoachHub GmbH, Berlin, Germany

2 Henley Business School, University of Reading, Reading, United Kingdom

Rosie Evans-Krimme

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

This conceptual paper explores the development of coaching, as an expression of applied positive psychology. It argues that coaching is a positive psychology dialogue which has probably existed since the emergence of sophisticated forms of language, but only in the past few 1000years, has evidence emerged of its use as a deliberate practice to enhance learning. In the past 50years, this dialectic tool has been professionalised, through the emergence of professional bodies, and the introduction of formal training and certification. In considering the development of the coaching industry, we have used Rostow’s model of sector development to reflect on future possible pathways and the changes in the coaching industry with the clothing sector, to understand possible futures. We have offered a five-stage model to conceptualise this pathway of development. Using this insight, we have further reviewed past research and predicted future pathways for coaching research, based on a new ten-phase model of coaching research.

Introduction

Coaching is often considered an applied aspect of positive psychology. Both emerged from humanistic psychology, with its focus on the flourishing of the individual, and how individuals, teams and society can create the right conditions for this to be achieved. In this paper, we explore the nature of coaching, as an applied aspect of positive psychology, the journey so far and where practice and research may be heading over the coming 30years.

It would seem only prudent at the start of this paper that we note the challenges of predicting the future direction of any industry and of research in general. We acknowledge the future is ‘trumpet-shaped’, emerging from the point of singularity (now) to multiple possible futures. Any attempt to accurately ‘predict’ the future is challenged by inevitable unforeseen events, their timing and the interaction between foreseen and unforeseen events. We have tried to improve our predictions by drawing on a previously published framework, which we have adapted. However, we ask the reader to note this is just one possible future.

What Is Coaching?

The clear link between coaching as lived positive psychology has been focused on by many writers ( Lomas et al., 2014 ). However, just how much of a driving force positive psychology was in the maturation of coaching is yet to be discussed. In order to establish the role positive psychology played in the maturation of the coaching sector, this section will review their shared historical roots and focus on the influence positive psychology research had on the evolution of coaching definitions.

Coaching and positive psychology’s histories are dynamic and rooted across multiple disciplines, yet they are both born out of the Human Potential Movement of the 1960s. This led to the popularisation of personal and professional growth and development, through pioneers such as Werber Erhard. Brock’s (2010) review of the development of coaching notes the humanistic tradition and the work of Carl Rogers’ of particular significance. Rogers’ focus on the relation and the needs of the clients’ and the potential to find their own way forward have become central features of coaching. Coaching rise coincided with a shift in the perspective about illness and wellbeing. This was the move from the medical model that focused on pathologies to the wellbeing model, which encouraged greater attention towards what individual’s strengths.

Interestingly, coaching psychology (CP) launched in the same year as positive psychology. Atad and Grant (2021) described how coaching psychology was a ‘grassroots’ movement, led by founders of the Coaching Psychology Unit at the University of Sydney and the Special Interest Group in Coaching Psychology in the British Psychological Society (BPS) including psychologists like Stephen Palmer, Jonathan Passmore and Alison Whybrow.

While positive psychology and coaching psychology both focus on the cultivation of optimal functioning and wellbeing ( Green and Palmer, 2019 ), often through the use of personal strengths development, Atad and Grant (2021) reported key differences. The first is that approaches like solutions-focused cognitive-behavioural coaching also aim to help clients define and attain practical solutions to problems. A second difference is the characteristics of the interventions used in each discipline. In coaching psychology interventions, the coach-coachee relationship is central to the coachees development of self-regulated change, whereas Positive Psychology Interventions (PPI’s) typically apply a self-help format.

Since its foundation, positive psychology (PP), the ‘ scientific study of positive human functioning and flourishing intra-personally (e.g. , biologically, emotionally, cognitively ) , inter-personally (e.g. , relationally ) , and collectively (e.g. , institutionally, culturally, and globally )’ ( Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ; Oades et al., 2017 ), has grown into a field of applied science ( Atad and Grant, 2021 ).

The field covers an array of topics, most commonly focused on life satisfaction, happiness, motivation, achievement, optimism and organisational citizenship and fairness ( Rusk and Water, 2013 ). Gable and Haidt (2005 , p. 103) defined positive psychology as ‘ The study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing ( wellbeing ) or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions ’. A vast number of PPI’s have been developed and validated ( Donaldson et al., 2014 ), with the aim to enhance subjective or psychological wellbeing or to cultivate positive feelings, behaviours, or cognitions ( Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009 ).

Strength development is viewed as a key process in positive psychology due to the shift from a deficit-based approach towards human functioning: a move from ‘what’s wrong and how can we fix it’, to ‘what’s right and how can we strengthen it’. McQuaid (2017 , p. 285–284) simply describes strengths as, ‘ the things you are good at and enjoy doing ’, which is reflective of Linley and Harrington’s (2006) definition of strengths as ‘ a natural capacity for behaving, thinking, or feeling in a way that allows optimal functioning and performance in the pursuit of valued outcomes ’. Strength-based interventions that aim to promote the awareness, cultivation and application of personal strengths have been reported to have many positive individual and organisational outcomes ( McQuaid, 2017 ). Strengths research is one of the most integrated concepts from positive psychology into coaching psychology.

Interestingly, coaching psychology (CP) also launched in the same year as positive psychology. Atad and Grant (2021) described how coaching psychology was a ‘grassroots’ movement, led by founders of the Coaching Psychology Unit at the University of Sydney and the Special Interest Group in Coaching Psychology in the BPS in the United Kingdom. CP also experienced its own rapid growth in research and practice ( Green and Palmer, 2019 ), which is discussed below.

At the heart of coaching, noted by multiple coaching writers, was its facilitative nature ( Passmore and Lai, 2019 ). Coaching pioneer John Whitmore’s working with Graham Alexander and Alan Fine in the later 1970s and 1980s, and informed by the work of Tim Gallwey (1986) , focused on the self-awareness and personal responsibility which coaching created. This led to Whitmore (1992) defining coaching as having the potential to maximise a person’s performance by adopting a facilitation approach to learning rather than teaching.

This has direct parallels with Deci and Ryan’s (1985) work on self-determination theory (SDT). SDT identifies the conditions that elicit and sustain motivation, focusing on self-regulated intrinsic motivation. These include the needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness ( Deci and Ryan, 1985 ). While Whitmore never formally engaged with SDT Whitmore’s definition of coaching can be seen as a direct application of Deci and Ryan’s (1985) SDT theory and therefore an early indicator of coaching as an applied aspect of positive psychology.

In Brock’s (2010) reflection on the common themes, the facilitative nature of coaching is the strongest similarity across definitions. Brock (2010) also emphasised the interpersonal interactive process that places the coaching relationship at the centre of the facilitation and essential for positive behavioural change. This perspective was maintained in later definitions, which introduced the purpose of coaching to drive positive behavioural changes ( Passmore and Lai, 2019 ) For example, Lai (2014) reported that this was driven by the reflective process between coaches and coachees and continuous dialogue and negotiations that aimed to help coachees’ achieve personal or professional goals.

In summary, in spite of the complementary nature of PP and CP, the fields remain sisters as opposed to fully integrated areas of practice, with coaching psychology drawing from the well of positive psychology, alongside wells of neuroscience and industrial and organisational psychology.

A Conceptual Model for Coaching Development

To date, little has been written about the development of the coaching sector, as a specific industry. This may reflect in part the relative immaturity of the industry, but a wider review of industrial literature reveals the categorisation of sector development is limited. One of the few conceptual models is Rostow’s (1959) generalised model of the six stages of economic growth. This offered a linear model of development, which reviews traditional society; the preconditions for take-off; the take-off; the drive to maturity; the age of high mass consumption; and beyond consumption (the search for quality). The model is summarised in Table 1 .

Rostow’s stages of economic growth.

| Stage | Key characteristics | Key manifestations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The traditional society | Subsistence economy Primary sector economy No surplus Lacks modern technology Poor economic mobility No centralised system for growth | Small technological advancements that improve processes |

| 2 | The preconditions for take-off | Shift towards an industrial society: modern alternatives to traditional approaches Advancements driven by technology and science Wholly primary sector economy | Increased demand for key industries or sectors Improvement of conditions for productivity and trade, including investment. Creation of industrial markets Reduction of waste surplus |

| 3 | The take-off | Rapid self-sustained growth Secondary economy expands Industrialisation continues to dominate Urbanisation increases | Growth limited to key sectors Sectors become resilient |

| 4 | The drive to maturity | Diversification of sector development Shift to consumer-driven investment | Acceleration of new sectors and deceleration of old sectors Significant investment into transportation and social infrastructures |

| 5 | The age of mass consumption | Enabling of widespread consumption of consumer goods Expansion of tertiary sector | Increase in urbanisation Hypergrowth across secondary and tertiary sectors Population has growing disposable income (Increased inequalities between high and low socio-economic countries) Application of scientific insights and research |

| 6 | Beyond consumption (the search for quality) | Impact of high consumption changes consumer behaviour/mindset: seeks for durability and sustainability | Resources are draining Natural and man-made disasters having an impact of the economy |

Rostow argued that these stages captured the dynamic nature of economic growth, reflecting the nature of consumption, saving, investment and the social trends that impact it. Rostow’s framework offered insight into the triggers for change at each stage. However, as a generalised model, it is unlikely that all industries or sectors follow the same pathway. Some may never take-off, and others remain as mass consumption. It is also important to note that Rostow’s model is based on observations from a predominantly Western economic perspective situated within a capitalist economic model of growth.

We believe this model provides a heuristic guide, a map, for those observing the development of coaching, and offers an opportunity to predict, based on trends in other industries, how coaching may develop over the coming few decades. In undertaking an analysis of the model, it may be helpful to explore it through a specific sector. The example we selected was clothing manufacture, as being a process which like language, dates back to the prehistory, but which has also changed and developed over the centuries.

The Clothing Sector

The clothing sector has undergone a transformation over the past 10,000years. We might start by considering ‘the sector’ at the time of the Neolithic Revolution, as humans transitioned from hunter gathers to farmers. In hunter-gatherer societies, clothing was primarily a form of protection: protection from cold, plants, animals and battles with fellow tribes. Although given evidence from modern day hunter-gatherer societies, there are also limited examples of parts of clothing being used for status, for example Native American head-wear ( Grinnell, 2008 ). As humans settled, this too started evolve with the emergence of greater status divisions and the development in manufacturing of items, allowing greater differentiation of objects. In the earliest period, most people will have collected the raw materials, engaging as a group in killing an animal. They will have prepared the materials in small groups, stripping the flesh and processing the hide and finished the item will individuals sewing to weaving items together to form the clothing.

As food surpluses emerged as a result of the shift towards settled farming, specialisms started to also emerge. Clothing production shifted from the collective task for small groups and individuals, to the one or more specialists, such as a tailor. This process of specialisation continued with the emergence of training and the development of trades: where individuals could progress over several years of training form apprentice through journeyman to master craftsman. Alongside, this came trade bodies and guilds in the 12th and 13th centuries, to represent the profession and to protect members rights ( Ogilvie, 2011 ). The industrial revolution brought further change with production moving from cottage industries, small shops or upstairs of building used as part home and part clothing ‘factory’ to formal factory production using mechanisation to increase consistency and reduce costs. This process has continued with continued development of automation and over the past 30 years through the digital revolution, which has witnessed a shift from individual’s controlling machines to machines controlling machines. Table 2 summarises the transformation of the clothing sector and demonstrates how Rostow’s model could be applied.

Model of clothing sector development based on Rostow’s model.

| Stage | Key characteristics | Key manifestations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The traditional society | Subsistence lifestyle Need for survival (stay warm and dry) | Humans wrapped furs, leathers, and plants around their bodies |

| 2 | The preconditions for take-off | Specialisation revolution Need for trade Cottage industry Labour intensive | Foundational technology for modern day clothing production was discovered, basic sewing needles Master craftsmen specialised in tailoring, which enabled trade |

| 3 | The take-off | Labour revolution Need to productivity Basic clothing production practices developed and defined Trading of materials and clothing Clothing manufacturing as a personal craft | Tailors master their craft Workers employed to produce materials for textiles and clothing Technological innovations increased productivity and efficiency of producing key textiles, such as cotton Surplus materials and clothing could be traded. |

| 4 | The drive to maturity | Industrial revolution Shift from craft into a service Automated production Need for expansion Clothing manufacturing as a technical process | Application of technology to transform textiles into mass-produced, consumer goods Factories specialised in production and manufacturing of certain products and clothing Master craftsmen (i.e., designers) become highly specialised and desired Emergence of sector bodies to represent the profession and protect members’ rights, guilds, and trade bodies |

| 5 | The age of mass consumption | Diversification revolution Shift to consumer-driven market Need to reduce production costs and increase profits | Globalisation increased trade and exchange of clothing goods Increased accessibility of lower labour and production costs, often due to automation of machinery and processes Population has a growing disposable income and consumers demand access to fashion items Increased availability of high street and cheap, fast-fashion brands; clothing not designed for life-time use. |

| 6 | Beyond consumption (the search for quality) | Decline and fall: impact of sector practices and society on sector, people, and environment Clothing production and manufacturing as human rights and climate emergency | Human rights violations against factory workers in low-economic countries in order to meet demands from consumers in high-economic countries Rise in sustainable fashion practices to negate the impact clothing production and throw-away society has on the environment |

Coaching: The Future of Research and Practice

We argue that coaching can learn from the evolution of these other sectors and from the wider conceptual model proposed by Rostow, to better understand the future direction of the coaching and its implications for practice and research.

We start by suggesting that coaching is likely to have a prehistory past. While some argue that coaching was born in 1974 ( Carter-Scott, 2010 ), we believe it is almost certain hunter gathers will have engaged in the use of listening, questioning and encouraging reflective practice to help fellow members of their tribe to improve their hunting skills or their sewing. There is some evidence from Maori people, in New Zealand, that such questioning styles have been used for centuries to aid learning ( Stewart, 2020 ). However, the spoken word leaves no trace for archaeologists to confirm the development of these practices.

While the clothing sector developed in full sight, leaving traces for archaeologists in graves and wall paintings, coaching remained a hidden communication form, until its emergence in societies where written records documented different forms of learning. At that moment, the Socratic form was born. It is often this moment which until now has been regarded as the birth of the positive psychology practice of coaching. It has taken a further 2,500years for coaching to move from a learning technique used by teachers to a specialisation increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few, which requires training, credentials, supervision and ongoing membership of a professional body. While there is good evidence of individuals using coaching in the 1910s ( Trueblood, 1911 ), 1920’s ( Huston, 1924 ; Griffith, 1926 ) and 1930’s ( Gordy, 1937 ; Bigelow, 1938 ), the journey of professionalisation started during the 1980s and 1990s, with the emergence of formal coach training programmes and the formation of professional bodies, such as the European Mentoring and Coaching Council in 1992 and International Coaching Federation in 1995. The trigger for this change is difficult to exactly identify, but the growth of the human potential movement during the 1960s and 1970s and its focus on self-actualisation, combined with the growing wealth held by organisations and individuals meant a demand for such ‘services’ started to emerge from managers and leaders as part of the wider trends in professional development which started in the 1980’s.

This trend of professionalisation has continued for the last three decade. The number of coaches has grown to exceed some 70,000 individuals who are members of professional bodies and industry, although given data from recent studies which reveal that over 30% of coaches have no affiliations, we estimate over 100,000 people earn some or all of their income from coaching ( Passmore, 2021 ). In terms of scale, the industry is estimated to be worth $2.849 billion U.S. dollars (International Coaching Federation, 2020), but in many respects, it has remained a cottage industry, dominated by sole traders and small collectives, with little consolidation of services by larger providers, with little use of technology and science to drive efficiencies or improve outcomes.

Given model and recent developments in technology and the growth of coaching science over the past 10years is coaching reaching a tipping point? Is coaching about to enter the next phase of sector development? Is coaching about to begin the transition from professional service delivered by a limited number of high-cost specialists to an industrial process capable of being delivering low-cost coaching for the many with higher standards in product (service) consistency?

What makes this change likely? There are three factors in our view propelling coaching towards its next stage in development. Firstly, the growth of online communications platforms, such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom and Google Hangout, are enabling individuals to connect with high-quality audio and video images. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020–21 has seen the development these platforms now reach almost universal adoption. At the same time, a growing number of employees have switched from ‘always in the office’ modes of working to either working from home or hybrid working, working 2, 3 or 4days a week from home ( Owen, 2021 ). Such models provide lower costs for employers, and evidence suggests many employees favour the flexibility working from home provides.

Secondly, the period 2010–2020 witnessed a growth in the science connected with positive psychology and coaching, proving practitioners with a good understanding of the theory and research. Access to this research has been enhanced by an increasing move to Open Access journals, the emergence of research platforms, such as ResearchGate, sharing published papers and tools such as Sci-Hub, granting access to published science, alongside search tools such as Google Scholar allowing efficient discovery of relevant material by practitioners, as well as academics with access to university library databases. In combination, these online tools are democratising the science of coaching and are stimulating the next phase of development.

The third factor is the growth of investor interest in digital platforms, which have seen significant growth during the 2010–2020 period, enabling start-ups to secure the investment need for the development of products, from online mental health (Headspace) to online learning (Lyra Learning - LinkedIn Learning).

The next phase we predict will be an emergence, growth and ultimately domination of coaching by online large-scale platforms, who offer low-cost and on-demand access to coaching services informed by science, in multiple languages and to a consistently high-quality standard. Echoing the changes in clothing production, with mechanisation using machines like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, and Arkwright’s spinning machine which revolutionised clothing production.

We have developed Rostow’s model and propose a 5P’s model for the coaching industry development. This is summarised in Table 3 . A journey from unconscious practice used by hunter-gatherer societies, through formal use in learning, to specialisation and professionalisation, to the deployment of technology and onwards towards a more conscious use across society of positive psychology approaches, including coaching as a tool to enhance self-awareness and self-responsibility, embedded in technology.

5P’s model of coaching industry development.

| Stages | Characteristics | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Peoplisation: (50,0000–5,000years ago) | Coaching as unconscious conversational tool, part of daily dialogue: | Coaching emerges as part of sophisticated language |

| Stage 2: Purposisation: (5000–50years ago) | Coaching with explicit learning goals | Coaching adopted by specialists, such as Greek Philosophers and others, to enhance learning |

| Stage 3: Professionalisation: (50years ago to today) | Specialist coach training, standards and certification | Emergence of professional bodies setting standard, training and accreditation leading to the creation of a profession |

| Stage 4: Productisation: (Mid 2020s onwards) | Coaching with science and technology | Emergence of specialist companies combining technology and science to offer lower cost, consistent and high-quality coaching process and outcomes |

| Stage 5: Popularisation | Many streams of coaching emerge | Coaching continues as a niche upmarket service by professionals, as an industrial process for the many at work and consciously adopted for use in personal encounters as part of daily dialogue for all encounters embedded in technology |

It is worth noting that across sectors the move from one stage to the next created disruption and negative consequences in uncontrolled markets. In agriculture, shifts in production, such as land enclosures, and introduction of mechanisation led to landlessness and starvation, in clothing manufacturing production disruptions lead to low pay and exploitation. These changes also stimulated agricultural revolts and the emergence of Luddites, as workers affected by change pushed back against these change in their daily work patterns, income levels or status.

In coaching, we can see similar push back from some in coaching, who fear the negative impacts of research and technology, as coaching starts to move away from being a cottage industry, where fee rates are unrelated to training, qualifications or other measurable indicators ( Passmore et al., 2017 ) towards providing greater consistency, evidence driven practice. Such push back is likely not only to be from individuals but also guilds (professional bodies) wo see their power being undermined by the rise of large-scale, Google-LinkedIn, providers, who’s income, corporate relationships and global reach will shift the power balance in the industry.

Given this awareness of the risks of change, it is beholden on the new technology firms to be sensitive to the needs of all stakeholders. We advocate a Green Ocean strategy ( Passmore and Mir, 2020 ). Under such a strategy, the focus is on collaboration, seeking sustainable win-win outcomes, which benefit all stakeholders, and take at their heart environmental considerations and ethical management, balancing such needs against the drive for quarterly revenues.

The Implications for Positive Psychology - Coaching Research

In previous papers, we have proposed a model reviewing the journey of positive psychology coaching research ( Passmore and Fillery-Travis, 2011 ). This offered a series of broad phases, noting the journey of published papers from case studies to more scientific methods, such as randomised control trials, between the 1980s and 2010. The past decade, 2011–21, has witnessed a continued development along the scientific pathway, thanks to the work of researchers such as Anthony Grant, Rebecca Jones, Erik de Haan and Carsten Schermuly.

Specifically, the publication of randomised control trials has grown from a handful of papers in 2011 to several dozen by 2021, while still limited in comparison to areas of practice such as motivational interviewing ( Passmore and Leach, 2021 ), the expanded data set has provided evidence for systematic literature reviews and combination studies, such as meta-analysis. These papers have provided evidence that coaching works, with an effect size broadly similar to other organisational interventions, as well as giving insights at to the most important ingredients of the coaching process.

It is this blossoming of higher quality, quantitative studies, which has led us to believe the science in coaching is maturing. While much work still needs to be done over the coming decade, the insights to date can be used to inform practice at a scale leading to Stage 4 in our 5P coaching sector model.

The coming decade may see opportunities for greater collaboration between coach service providers, as these organisations increase in scale and profitability, and university researchers, keen to access large data sets enabled by the greater use of technology and the global scale of the new coach service providers.

Reflecting these industry changes and the proliferation of research, we have also updated the research journey model, reflecting these developments. We suggested the emergence of new phase of research exploring individual, exceptions and negative effects of coaching ( Passmore, 2016 ; Passmore and Theeboom, 2016 ). This has started to happen with work by Schermuly and Grabmann (2018) and De Hann (2021) . We have linked research papers to the model of coach development in Table 4 and have extended it to create 10 phases.

10-phase model of coaching research.

| Phases | Examples of study |

|---|---|

| Phase 0 - Pre-science | ; ; ; |

| Phase 1: Case study and surveys | ; |

| Phase 2: Qualitative studies – theory generation | |

| Phase 3: Small sample RCT’s and theory testing | |

| Phase 4: Large sample RCT’s | |

| Phase 5: Meta-Analysis studies | ; ; |

| Phase 6: Systematic Literature Review | ; ; |

| Phase 7: Identifying the active ingredients | |

| Phase 8: Exploring difference and exceptions | ; |

| Phase 9: The coaching assignment | Research questions might include: How does homework impact on outcomes across the coaching assignment? How does a tripartite commissioning, review and evaluation impact on coaching outcomes? |

| Phase 10: The System | How does coaching impact on the wider system of stakeholders? How does team coaching differ in its relationship, active agreements and outcomes from 1–1 coaching? |