- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Writing Can Help Us Heal from Trauma

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo

Three prompts to get started.

Why does a writing intervention work? While it may seem counterintuitive that writing about negative experiences has a positive effect, some have posited that narrating the story of a past negative event or an ongoing anxiety “frees up” cognitive resources. Research suggests that trauma damages brain tissue, but that when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain. This matters, both personally and professionally. In a moment still permeated with epic stress and loss, we need to call in all possible supports. So, what does this look like in practice, and how can you put this powerful tool into effect? The author offers three practices, with prompts, to get you started.

Even as we inoculate our bodies and seemingly move out of the pandemic, psychologically we are still moving through it. We owe it to ourselves — and our coworkers — to make space for processing this individual and collective trauma. A recent op-ed in the New York Times Sunday Review affirms what I, as a writer and professor of writing, have witnessed repeatedly, up close: expressive writing can heal us.

- Deborah Siegel-Acevedo is an author , TEDx speaker, and founder of Bold Voice Collaborative , an organization fostering growth, resilience, and community through storytelling for individuals and organizations. An adjunct faculty member at DePaul University’s College of Communication, her writing has appeared in venues including The Washington Post, The Guardian, and CNN.com.

Partner Center

Therapeutic Writing Groups

Therapeutic writing offers a unique opportunity for self-discovery and healing by creatively engaging the inner world..

Or call me: (805) 269 6644

Read an Interview with Chantal about Writing Therapy

featured in the newsletter of the Santa Barbara chapter of the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapy.

What Are Therapeutic Writing Groups?

The aim of the therapeutic writing group is to help members foster insight and self-awareness as well as to generate support from others through the process of writing.

The writing process allows unknown or repressed material to emerge into the conscious mind. That is why we begin the writing periods with journaling prompts, which serve as a tool to prod the unconscious. This process is further supported by the technique of stream-of-consciousness writing, which serves to circumvent our natural tendency to censor our thoughts and feelings. Engaging with oneself on the page in this way can help bring about new insights and meaning–old stories are often told in new ways.

The Therapeutic Writing Group Environment

The therapeutic writing group environment, protected by principles of confidentiality and non-judgement, creates a uniquely safe space for vulnerable, hidden/edited material to find expression. Paying attention to what the writing reveals and then further validating and processing it within the group has a powerfully beneficial therapeutic effect.

An added benefit of group therapy is that people can discover that there is a universal quality to our most vulnerable and private perceptions and impulses. This insight can reduce a sense of isolation, shame, anxiety, and depression; it fosters a deeper sense of connection with others as well as, ultimately, with oneself.

Do I Need Experience as a Writer/Creative Writer?

No experience needed. The idea is to use writing as a tool to facilitate self-awareness, it’s not intended to be performative. The group avoids critique and pays no attention to grammar, spelling or structure. In fact, the intention is to leave all that behind.

How Do I Know That The Therapeutic Writing Group is Right for Me?

The group is suitable for individuals who wish to know themselves more deeply through the process of writing therapeutically. In order to determine whether the group is an appropriate fit and to learn more about individual needs and expectations, I meet with each potential participant before admitting them to the group.

join the list

Join 7,000+ ambitious women ready to redefine success and put an end to toxic hustle culture. , get on the list.

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and tap into a slower life that prioritizes your energy and peace

Ultimate Guide to Creative Writing Therapy (with Writing Therapy Prompts)

March 22, 2023

I believe that taking care of yourself should always come first. So, my job is to help you create a slow and mindful life that aligns with your values and goals so you can finally go from a state of constantly doing to peacefully being.

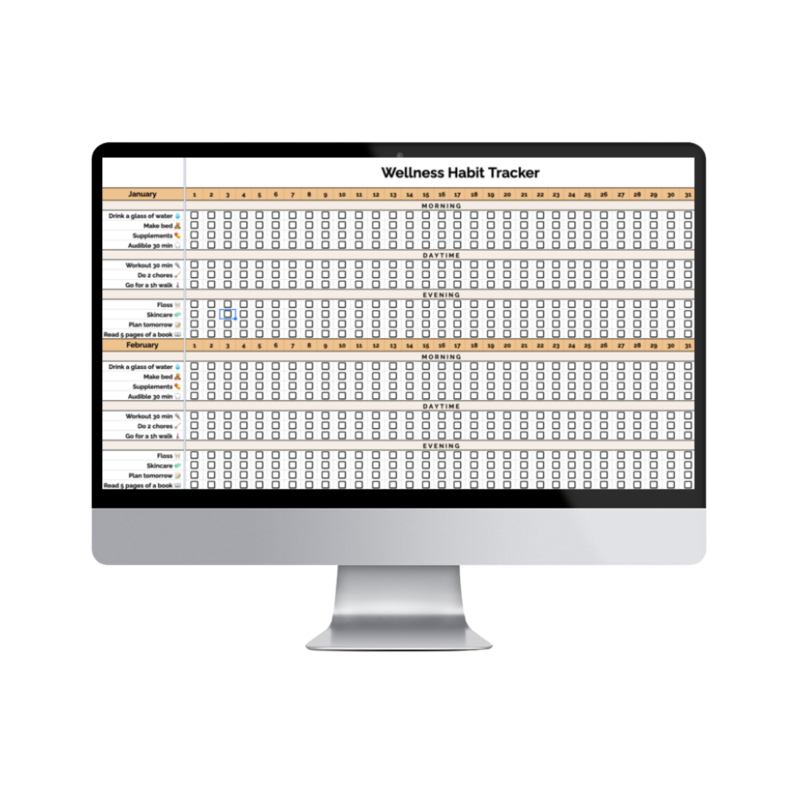

5-Minute Wellness Habit Tracker That *Actually* Works

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is specifically designed to help you protect your time, have blissful boundaries, achieve your goals, and be extra productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes/day.

join the movement

Sign up to get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can tap into a slower life and go from constantly doing to peacefully being.

Creative writing therapy, or therapeutic writing is a form of therapeutic intervention that uses writing as the tool to explore and express your thoughts, feelings and emotions. It’s also known as journal therapy – and it’s essentially the art of writing in a journal to heal yourself.

Writing therapy can be a useful tool for people who struggle with mental health, have experienced trauma or grief, or are simply looking for a creative outlet to process their thoughts and feelings. Today we’re going to explore what creative writing therapy is, how it works, and the potential benefits of writing therapy. We’ll also share writing therapy prompts to help you get started and explore writing therapy today.

Please keep in mind that there is no true substitute for seeing a licensed therapist, and if you feel like you could benefit from talking to someone and getting help with what you’re going through – you’re not alone! There are tons of incredible therapists out there to help you. Here at Made with Lemons we’re big advocates for therapy and if you’d like a more inside scoop to our own journey with therapy, join On Your Terms . It’s a wellness newsletter that shares a more inside look to our own wellness journey as well as tools to help you along yours. Learn more about On Your Terms here.

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from “busy” to “present” and show up as your best self.

What is Creative Writing Therapy?

Writing therapy, also known as therapeutic writing, is a form of creative and expressive therapy that involves writing about your personal experiences, thoughts and feelings. It can take many forms, including journaling, poetry, creative writing, letter writing, or memoirs. Writing therapy can be done individually or in a group setting. It can also be facilitated by a therapist, counselor or writing coach.

The purpose of creative writing therapy is to help you express and process your emotions in a safe and supportive environment. It’s helpful to be able to write out your thoughts and feelings that might be hard to articulate in other ways.

You might also see therapeutic writing used to help explore issues that are difficult to discuss in traditionally talking therapy sessions. And when your therapist invites you to try writing therapy, it’s also used in conjunction with other forms of therapy, such as trauma-focused therapy, to enhance its effectiveness.

An example of creative writing therapy could be writing a letter to a person who hurt you, and then shredding or burning the letter to release some of the hurt and anger.

How Does Therapeutic Writing Work?

Writing therapy works by allowing individuals to express their thoughts and feelings in a way that is both private and creative. The act of writing can help you organize your thoughts and gain clarity on your emotions. Writing can also be a way to release pent-up emotions and relieve stress.

For example, if you’re feeling stressed after a long day of work, taking a few moments to write down what’s stressing you out and allowing yourself to let it go, can help you have a calm and more relaxing evening.

Writing therapy should be a truly non judgemental space. It’s a time to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. The goal here is to let words flow freely, without judgment or criticism. Creative writing therapy sessions can be structured or unstructured, and sometimes it’s helpful to use prompts or exercises to help you get started. (i.e. what in your life is bringing you the most anxiety, or writing a letter to your friend to express ___________ hurt you when they said that.)

Oftentimes we find it easier to write about our hurt, our pain and the experiences that caused that, as opposed to opening up to talk about those things. In this way, writing can be a way to explore and process complex emotions such as grief or anger in a safe and supportive environment, where no one can get hurt further by what’s being felt and expressed.

Potential Benefits of Writing Therapy

Now let’s talk about some of the benefits of therapeutic writing.

Improved mental health

Writing therapy can be a tool that helps you manage symptoms of depression, anxiety and other mental health conditions. You can use journaling therapy to express and process difficult emotions, which over time can lead to improved mental regulation and a better sense of control over your thoughts and feelings.

Increased self-awareness

Creative writing therapy can help you gain a better insight into your thoughts and behaviors. By reflecting on your experiences through writing, you can start to identify patterns and gain an understanding of yourself.

Stress relief

Therapeutic writing can be a way to relieve stress and reduce anxiety. Writing is often cathartic, allowing you to release pent-up emotions and start to feel relief from things that would otherwise feel overwhelming.

Improved communication skills

Journal therapy can also help you improve your overall communication skills. When you practice expressing yourself through writing, you can develop more confidence to communicate more effectively in both your personal and professional relationships. In essence, writing your feelings can help you communicate them better when needed.

Increased creativity

Lastly, creative writing therapy can also be a way to tap into your creativity and imagination. We talk a lot about your inner child around here, and journal therapy can be another helpful way you can interact with your inner child. Through writing you can explore new ideas and perspectives, leading to your own personal growth.

How to try Creative Writing Therapy Today

Now let’s talk about how you can try therapeutic writing for yourself today. These tips are going to help you get started with writing therapy from home, as a personal activity to help heal yourself.

Set aside dedicated time for writing therapy

Like most self improvement and self care techniques, it helps to set aside a dedicated time to write regularly. We know this can be a challenging task, especially if you’re struggling with mental health issues or challenges in your life. A good place to start is to set aside a few minutes each evening to write and decompress from your day. It can be just 2 minutes before bed. Remember, therapeutic writing is a non judgemental activity, so the amount of time you dedicate isn’t important, it’s just important to show up for yourself.

Find a quiet and comfortable space

Find a place that’s quiet and comfortable, and where you can write without interruptions. Some people find it helpful to create a writing ritual, such as lighting a candle or playing soft music to create a sense of calm and focus. Find what works for you, in a space where you can be alone for a few minutes.

Choose a writing therapy prompt or topic

At the end of this guide we’re going to share writing therapy prompts to help you explore creative writing therapy and give you a starting point. You can also talk to your therapist to get prompts, or find some online. Prompts can be general, such as “write about what makes you grateful or happy”, while others can be more specific, such as “write about a time that you felt overwhelmed.”

Write freely and without judgment

The most important thing about writing therapy is to write freely, without judging yourself. Allow yourself to write without worrying about grammar, punctuation or spelling. Don’t put a time limit on your writing, or feel like you have to write a certain number of words or pages. The goal here is to allow your thoughts and emotions to flow freely without any judgment at all.

Write honestly and openly

Along with being judgment free, it’s also so important that you write honestly and openly. Writing therapy is a space for honesty and openness. This space is created for you to share your thoughts and emotions, even if they're difficult or uncomfortable to confront. Just be open to exploring them, and remember that you don’t have to share this with anyone, so it’s a space where you can be fully honest with yourself.

Reflect on your writing

After writing, you can take a few moments to reflect on what you have written. It might even be helpful to come back to what you have written at another time, when you have a clear head or have left the emotions behind. This can help you consider the emotions and patterns that you have expressed. Doing this reflection can help you gain more insight into your thinking patterns and emotions for future sessions.

Consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor

Lastly, consider sharing your writing with a therapist or counselor. They can help you process emotions and gain a deeper understanding of yourself. Sharing your writing can also help you feel less alone in your struggles and provide important validation for your experiences.

20 Writing Therapy Prompts

- When do I feel the most like myself?

- How do I feel at this moment?

- What do I need more of in my life?

- What do I look forward to every day?

- What is a lesson that I had to learn recently?

- Based on my daily routine, where do I see myself in 5 years?

- What don’t I regret?

- What would make me happy right now?

- What has been the hardest thing to forgive myself for?

- What’s bothering me? And why?

- What do I love about myself?

- What are my priorities right now?

- What does my ideal day look like?

- What does my ideal morning look like? Evening?

- Make a list of 30 things that make you smile

- Make a gratitude list

- The words I’d like to live by are…

- I really wish others knew this about me…

- What always brings tears to my eyes?

- What do I need to get off my chest today?

Creative writing therapy can be a powerful tool for exploring and processing thoughts and emotions. When you set aside a dedicated time to write, and create a safe and supportive space for yourself, you can gain insight into your emotions and develop better tools to manage them. With practice and commitment, writing therapy can become a habit for your self care routine.

If you’d like to build the habit of writing therapy in your own life, then we’d like to invite you to download our habit tracker. It’s super easy to use, beautifully designed and completely free. All you need is a google account to access it. Grab a copy of our habit tracker here.

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment

How to Create the Perfect Anti “That Girl” Morning Routine in Less Than One Hour »

« Revamp Your Life This Spring: The Ultimate Spring Reset Guide

Previous Post

back to blog home

Test & Tried Strategies for Working Women to Enhance Health and Well-being

How To Make Your Self Care Plans Align With Your Business Goals

Summer of Self-Care (60 Solo Date Ideas for Summer 2023)

How to Live a Sober Life (70 Ways to Practice Sober Self-Care)

A Complete Guide to Mushroom Microdosing

Self Love Ideas Based on Your Love Language

so hot right now

This super customizable and in-depth wellness habit tracker is designed to help you protect your time, achieve your goals, and be more productive every day so you can finally go from overwhelmed to organized in just 5 minutes.

Wellness Habit Tracker

Ready to success and put an end to toxic hustle culture?

Get productivity, intentional living and self-care tips so you can go from "busy" to "present" and show up as your best self in life and business in this weekly newsletter.

Do you sleep 7-8+ hours but feel exhausted? Does resting feel selfish and unproductive? Get your free download to find out about the 7 types of rest and why you'll burnout without it.

7 Types of Rest You Need

FREE DOWNLOAD

3 Steps to Avoid Burnout & Create More Intentionality in Your Life and Business

free class!

Come say hi on the 'gram!

apply for 1:1 coaching

GET my newsletter

© MADE WITH LEMONS 2020- 2024 | Privacy Policy | Terms & CONDITIONS | Design by Tonic

London-based multi-passionate Lifestyle designer for busy female entrepreneurs, lover of Golden Retrievers, skin care obsessed, & proud plant mom.

Learn from me

@onyourtermsco

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time. By submitting this form you confirm you have read our privacy policy and you accept our terms and conditions

Join the anti-hustle movement!

Your Information is 100% Secure And Will Never Be Shared With Anyone. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Submit your details to get your report

Dummy Text. Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) numbers among the greatest philosophers.

Email Address

Remember me

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Writing therapy: types, benefits, and effectiveness, thc editorial team august 7, 2021.

In this article

What Is Writing Therapy?

How does writing therapy work, types of writing therapy, potential benefits of writing therapy, conditions treated by writing therapy, summary and outlook.

Writing therapy, or “expressive writing,” is a form of expressive therapy in which clients are encouraged to write about their thoughts and feelings—particularly those related to traumatic events or pressing concerns—to reap benefits such as reduced stress and improved physical health. 1 Writing therapy may be used in many environments, including in person or online . It may be supervised by a mental health professional or even occur with little or no direct influence from a counselor. There are several types of writing therapy, including, but not limited to narrative therapy, interactive journaling, focused writing, and songwriting. Although traditional psychotherapy , or talk therapy, has been standard practice in many therapeutic and counseling environments, evidence shows that writing therapy has many potential physical and psychological health benefits. 2

What Is the History of Therapeutic Writing / Expressive Writing?

Humans have expressed belief in the healing power of the written word since ancient times. For example, in the fourth century B.C.E., certain groups in Egypt believed that ingesting meaningful words written on papyrus would bring about health benefits. Words were thought to have medicinal and magical healing powers, so much so that inscribed above Egypt’s famed library of Alexandria was the phrase “The Healing Place of the Soul.” 1

However, the roots of modern therapeutic writing may be found in bibliotherapy , a form of therapy that employs literature and reading to help people deal with challenges in their own lives. 3 This practice dates back to the fifth century B.C.E. when it was thought to cure a condition called melancholia, or a deeply experienced depression .

More recently, writing therapy gained momentum in the United States in the early 19th century, 1 and it was popularized in the early 20th century with psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud’s Creative Writers and Day Dreaming. Though talk therapy was still the go-to approach, writing therapy gained steam in the 1930s and 1940s as creative therapies involving the arts , such as music, dance, and writing grew. The 1965 American Psychological Association (APA) convention, held in Chicago, Illinois, hosted a symposium that focused on written communications with clients. This symposium, organized by a division of the APA called Psychologists Interested in the Advancement of Psychotherapy, generated a boom in writing therapy research in the 1970s. 1

In the 1980s, social psychologist James Pennebaker emerged as a leading advocate and researcher of writing therapy. His research focused on the benefits of writing about or discussing one’s emotional disturbances, including reduced stress and improved immune function. He also claimed that writing about traumatic events could help people cope. His work helped propel writing therapy into the mainstream of psychotherapeutic practice. 1

There are two main theories as to how writing therapy works. The first posits that inhibition or suppression of emotions , traumatic events, or aspects of one’s identity constitutes a long-term, low-level stressor and has adverse health effects, such as an increased likelihood of becoming ill. Writing therapy can serve as an act of disclosure, and of written emotional expression, and therefore remove the stressor. However, this theory has become less accepted because research has shown that different acts of expression do not reap the same health benefits as writing therapy. 4

For example, Pennebaker conducted a study in 1996 in which one group of participants was asked to express a traumatic experience through physical movement, and another group was asked to express themselves through both physical movement and writing. Only the group that used both movement and writing showed significant physical health improvements. Pennebaker found that the specific language used while writing is associated with the physical and mental health benefits. When people’s emotional writing compositions were analyzed by judges and by the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software, positive emotion words like “happy” and a moderate number of negative emotion words like “sad” were associated with good physical health, while high and low levels of negative emotion words were associated with poor physical health. Compositions that showed an increase in causal words like “reason” and insight words like “realize” showed the most improved physical health in their writers. 4

When engaging in writing therapy, clients are asked to write about a traumatic experience. A standard practice might involve writing for 15 to 20 minutes for three consecutive days. 5 A 2002 study published in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine found that of three groups assigned to journal for one month, the group asked to write about “cognitions and emotions related to a trauma or stressor” enjoyed the most benefits of writing therapy; they had a better perspective on the stressful experience about which they wrote. 6

Sometimes this practice is self-generated. The act of journaling has increased in popularity, especially with the growth of aesthetic practices such as bullet journaling, which combines a journal, calendar, and planner. 7

Photo by Brent Gorwin on Unsplash

There are several types of writing therapy, which generally fall into two categories: writing therapy conducted with the guidance of a mental health counselor and self-motivated writing therapy, the latter of which anyone can take up at their own pace.

A counselor or mental health professional might use writing therapy with clients who find it difficult to verbalize their thoughts or emotions. Narrative therapy, a form of writing therapy that clients and therapists can use together, is often helpful in this situation. 8 Narrative therapy involves the client and mental health professional “reauthoring” a traumatic or problematic story from the client’s life. 9 This method helps the client recontextualize their experience by removing the assumptions and context they have assigned to it to see it from a more objective perspective. 8

Another common format, which can be practiced with or without the guidance of a mental health professional, is called interactive journaling. It combines aspects of writing therapy and bibliotherapy. In interactive journaling, clients are provided with a journal prompt, or a starting point, which they then use to inform their writing. This method is especially effective in substance abuse treatment because it can educate patients and promote reflection and exploration of their experiences. It can also benefit students in the health care field because it can help them empathize with and understand their clients’ experiences. 1

Two other types of writing therapy are focused writing and songwriting. Focused writing incorporates worksheets that educate and guide clients, 10 and songwriting combines music therapy and writing therapy to provide clients with an avenue to reminisce and express their emotions. 11

Researchers have found that expressive, or therapeutic writing, can have numerous physical and psychological health benefits, some of which include: 1

- better immune function

- fewer doctor visits

- less stress

- improved grades in school

- reduced emotional and physical distress

- decreased depression symptoms

- lower blood pressure

- improved liver function

- fewer missed days of work

- strengthened memory

In addition to its general benefits, writing therapy has been an easily accessible resource to treat people with many different conditions and stressful or traumatic experiences.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Evidence suggests that writing therapy can posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and the symptoms of depression often associated with PTSD. The potential effectiveness of writing therapy in helping people cope with trauma makes it a useful alternative when more traditional modes of therapy are ineffective or impossible to access. 12

For example, a study published in 2013 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine used writing therapy to treat 70 women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse. Researchers asked the women to write about trauma or sexual schema (the “cognitive generalizations” someone has about their sexual selves, informed by prior sexual experiences) during five 30-minute sessions, which occurred over up to five weeks. 13 At three different intervals—two weeks, one month, and six months—the study participants were asked to complete interviews and questionnaires regarding their sexual function, PTSD, and depression. Researchers found that between pretreatment and posttreatment, participants reported fewer symptoms of PTSD. According to study findings, participants who wrote about sexual schema were also more likely to recover from sexual dysfunction. 14

Some studies have found that engaging in writing therapy can help reduce anxiety . 15 , 16 In a study conducted in 2020 by faculty of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences in Iran, researchers administered three writing therapy sessions to pregnant women, plus two telephone calls between the sessions and basic pregnancy care, over four to six weeks. During the first session, the women were asked to write about their concerns regarding pregnancy and brainstorm solutions that would help relieve the anxiety they induce, and the phone calls encouraged them to follow through with the solutions. In the second session, researchers employed narrative therapy techniques and asked the women to write a story that outlined their concerns about pregnancy and then applied the solutions they had previously generated. The final session fostered a group discussion between the participants about the previous assignments. The study concluded that the women who engaged in writing therapy had significantly less anxiety than a comparison group who received only the standard pregnancy care. 17

Studies have shown that symptoms of depression decrease among people who utilize writing therapy. For example, in one study published in a 2014 issue of Cognitive Therapy and Research , one group of undergraduate students was tasked with non-emotional writing, or writing that does not focus on difficult or traumatic experiences and feelings, and another group was tasked with expressive writing, writing that does deal with emotional distress and trauma, focused in this case on emotional acceptance . The students in the latter group who experienced low or low to mild symptoms of depression saw a reduction in their symptoms. 18

Another study, conducted by researchers from the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Italy with women who had recently given birth, again divided participants into two groups; one performed expressive writing, and the other simply wrote about neutral topics. The women who used expressive writing had lessened depressive symptoms, whereas those in the neutral writing group saw no significant change. 19

Bereavement

People suffering the loss of a loved one can benefit greatly from writing therapy. It can reduce the number of negative feelings surrounding the event and allow for closure. It promotes self-care and therefore helps the client recover after a loss. 20 Writing therapy can also help reduce the separation anxiety that grief can prompt, gives clients a fresh perspective on their loss, and recognizes their bereavement journey. 21

A 2011 study published in the Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology conducted 10 writing sessions over five weeks with people who had lost pregnancies. The participants were asked to write about their pregnancy loss, write a letter to a friend as if the friend were experiencing the same loss, and write a letter to themselves or to someone who witnessed the loss. The participants’ levels of grief and loss decreased after the writing therapy treatment. 22

Technology has made many forms of therapy more accessible for many people. The internet can connect people in nearly any geographical zone to therapists who may be physically distant. Writing therapy, in particular, transitions easily to the virtual world; most forms don’t require face-to-face meetings at all and can be conducted over email.

In addition, writing therapy is a form of self-help intervention that anyone may practice. Many writing prompts (such as these links from Disability Dame and Dancing through the Rain ) are available online and enable people to immediately begin writing and benefit from this therapy. 23 Whether practitioner- or self-guided, writing therapy is an accessible practice that offers many potential benefits to those who use it.

- Moy, J. D. (2017). Reading and writing one’s way to wellness: The history of bibliotherapy and scriptotherapy. In Higler, S. (Ed.), New Directions in Literature and Medicine Studies (pp. 15–30). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51988-7_2

- Holden, J. D., & Mugerwa, S. (2012). Writing therapy: A new tool for general practice? British Journal of General Practice, 62(605), 661–663. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X659457

- THC Editorial Team. (May 22, 2021). Reading as therapy: Bibliotherapy and mental wellness. The Human Condition. https://thehumancondition.com/reading-as-therapy-bibliotherapy/

- Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science, 8(3), 162–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00403.x

- Qian, J., Sun, S., Sun, X., Wu, M., Yu, X., & Zhou, X. (2020). Effects of expressive writing intervention for women’s PTSD, depression, anxiety, and stress related to pregnancy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research, 288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112933

- Lutgendorf, S. K., & Ullrich, P. M. (2002). Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10

- Normark, M., & Tholander, J. (2020). Crafting personal information: Resistance, imperfection, and self-creation in bullet journaling. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376410

- Goodrich, T., Hancock, E., Kitchens, S., & Ricks, L. (2014). My story: The use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Madigan, S. (2011). Narrative therapy. American Psychological Association.

- McGihon, N. N. (1996). Writing as a therapeutic modality. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 34(6), 31–35. https://doi.org/10.3928/0279-3695-19960601-08

- Ahessy, B. (2017). Song writing with clients who have dementia: A case study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.03.002

- Kamphuis, J. H., Reijntjes, A., & van Emmerik, A. A. P. (2013). Writing therapy for posttraumatic stress: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(2), 82–88.

- Anderson, B. L., & Cyranowski, J. M. (1994). Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1079

- Lorenz, T. A., Meston, C. M., & Stephenson, K. R. (2013). Effects of expressive writing on sexual dysfunction, depression, and PTSD in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse: Results from a randomized clinical trial. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(9), 2177–2189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12247

- Barrett, M. D., & Wolfer, T. A. (2001). Reducing anxiety through a structured writing intervention: A single-system evaluation. The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 82(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.179

- Shen, L., Yang, L., Zhang, J., & Zhang, M. (2018). Benefits of expressive writing in reducing test anxiety: A randomized controlled trial in Chinese samples. PLoS One, 13(2), Article e0191779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191779

- Esmaeilpour, K., Golizadeh, S., Mirghafourvand, M., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S., & Montazeri, M. (2020). The effect of writing therapy on anxiety in pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5812/ijpbs.98256

- Baum, E. S., & Rude, S. S. (2013). Acceptance-enhanced expressive writing prevents symptoms in participants with low initial depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37. 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9435-x

- Camisasca, E., Caravita, S. C. S., Di Blasio, P., Ionio, C., Milani, L., & Valtolina, G. G. (2015). The effects of expressive writing on postpartum depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychological Reports, 117(3), 856–882. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.13.PR0.117c29z3

- Kristjanson, L. J., Loh, R., Nikoletti, S., O’Connor, M., & Willcock, B. (2004). Writing therapy for the bereaved: Evaluation of an intervention. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662103764978443

- Thatcher, C. (2021). Whys and what ifs: Writing and anxiety reduction in individuals bereaved by addiction. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15401383.2021.1924097

- Kersting, A., Kroker, K., Schlicht, S., & Wagner, B. (2011). Internet-based treatment after pregnancy loss: concept and case study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 32(2), 72–78. http://doi.org/10.3109/0167482X.2011.553974

- Wright, J. (2002). Online counselling: Learning from writing therapy. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 30(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/030698802100002326

Related Articles

Art Therapy: Overview and Effectiveness

Problem-Solving Therapy: Overview and Effectiveness

Gestalt Therapy: Background, Principles, and Benefits

Bibliotherapy: Benefits and Effectiveness

Related books & audios.

The Feelings Book Journal

By lynda madison.

The Anxiety Journal

By corinne sweet.

Journal Therapy for Calming Anxiety

By kathleen adams.

The Simple Abundance Journal of Gratitude

By sarah ban breathnach.

Welcoming the Unwelcome

By pema chödrön, related organizations.

- National Coalition of Creative Arts Therapies Associations, Inc. (NCCATA)

Explore Topics

- Relationships

- See All Subtopics

- Tic Disorders

- Energy Therapy

- Creative Arts Therapies

- Spirituality

- Mindfulness

- Forgiveness

- Life and Nature

- Philosophy and Thought

- Technology and Society

- Sadness, Grief and Despair

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

- Self-Report Measures, Screenings and Assessments

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Research Highlights

- Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

- Family Therapy

- Psychotherapy

- Humanness and Emotions

- Mental Health and Conditions

- Mindfulness and Presence

- Spirituality and Faith

Subscribe to our mailing list.

- Mar 11, 2019

Creative Writing Prompts for Mental Health

Updated: Mar 12, 2019

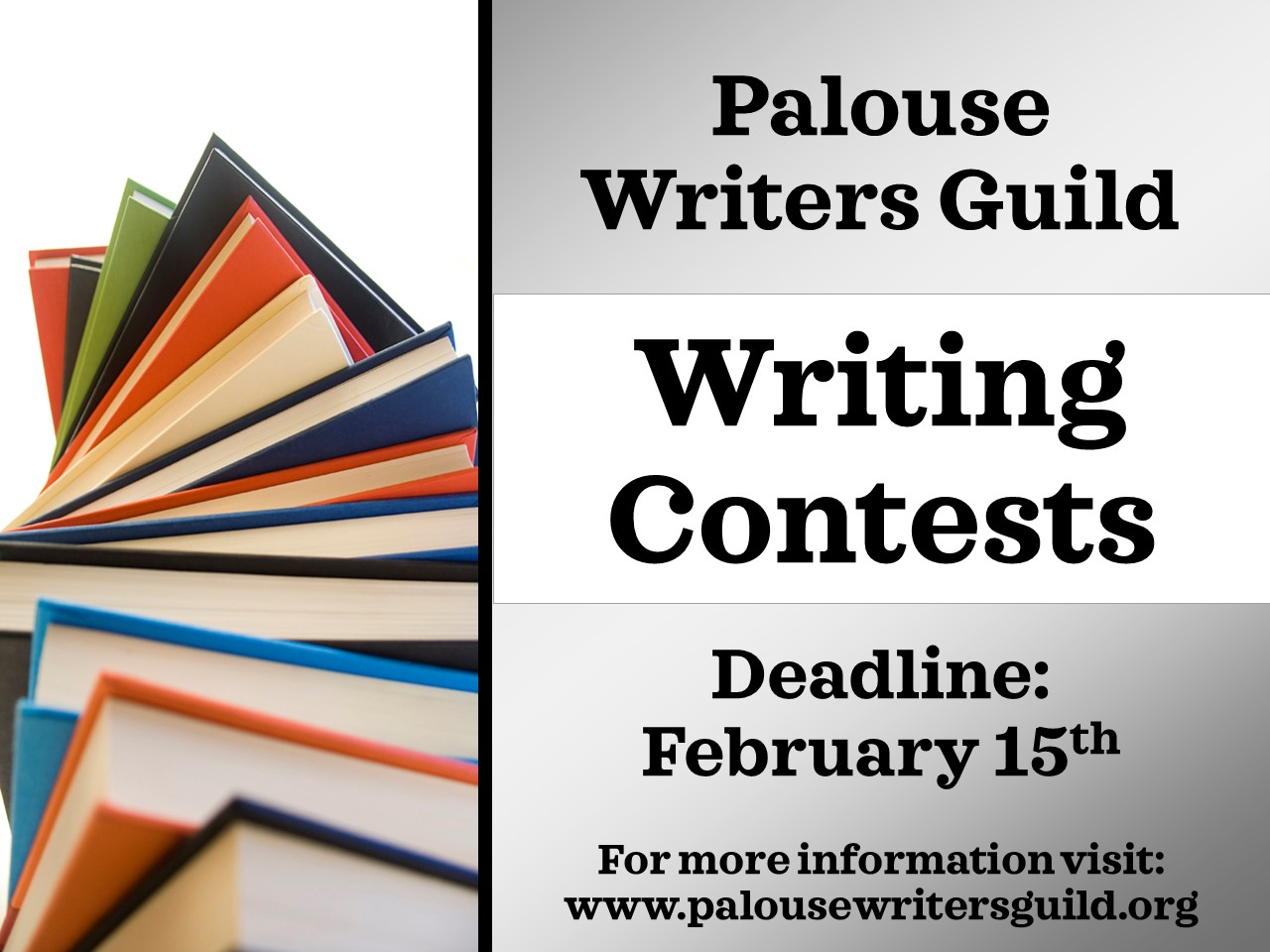

There is plenty of great research proving that journaling and creative writing can improve mental, and even physical health. Writing is a powerful tool that can be used for so many things; making sense of difficult situations, identifying and understanding big emotions, easing loneliness, cultivating meaning, improving self-esteem, learning to forgive...the list goes on!

However, all writers can attest to the anxiety that a blank page can induce. It's a lot of pressure to sit down and figure out how to write something that improves your mental health. If you're not sure where to begin, skim through the following prompts and write to the prompt that speaks to you the mos

Personify your anxiety, panic, depression, or addiction. Give it a name, a voice, a physical form-human or otherwise. When your symptoms are at their worst, what is this being saying to you? What do you want to say back? (For some reason, my anxiety is an insidious green version of Mad Magazine's Spy vs. Spy pictured below. His name is Jeff).

Ten years from now, in a perfect world, who are you and what are you doing with your life?

What positive things are you doing in your life right now that you never get thanked for? How would things change if you started being appreciated for those actions?

Do you have ghosts?

Write about a time you meant to go one place, but ended up somewhere else.

Spend some time thinking about who your alter-ego might be. How does this person look/act/dress? What pieces of yourself does your alter-ego express?

Are there cycles or seasons to your life that you haven't thought about before? How do you know you are in one of these cycles/seasons?

What is terrifying?

What is awe-inspiring?

What are you f---ing mad about?

Here, at the tail end of winter in Denver and Summit County, many of us need a little boost in mood and energy to get us through to those warmer, sunnier summer months. Writing can be a great addition to your self-care practice, which is especially important during the darker, colder times of year.

Recent Posts

4 tips to improve child's experience with online therapy

How to Resolve Relationship Conflict in 5 to 15 Minutes

The Power of Pause: Five ways to press that pause button (big or small)

“Writing by Prescription”: Creative Writing as Therapy and Personal Development

- Open Access

- First Online: 16 December 2020

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Leni Van Goidsenhoven 5 &

- Anneleen Masschelein 6

Part of the book series: New Directions in Book History ((NDBH))

6070 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

This chapter investigates how-to books on creative “life writing” for therapy, transformative learning, and personal development, in short, therapeutic writing. This subgenre of writing advice is situated in two different domains with psychology and pedagogy on the one hand, and life writing and creative writing on the other hand. After a brief overview of the history of therapeutic writing, we focus on Jessica Kingsley Publishers (JKP), a leading international niche publisher in the field of neurological and cognitive differences. JKP offers a combination of popular-science books, memoirs, and self-help publications, as well as a series of how-to books on writing for therapy or personal development. By this specific grouping of genres and formats, JKP turns its readers into writers and also guides the process of writing by setting out standards for narratives about neurological illness and disability, both in content and form. Combining both textual and contextual analysis, we examine the advice oeuvres of three JKP authors, Gillie Bolton, Kate Thompson, and Celia Hunt, to see how they relate to the therapeutic and self-help ethos as well as to more literary forms of creative writing, and how they negotiate the ideas of becoming a writer through craft, therapy, and self-expression.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The poetics of vulnerability: creative writing among young adults in treatment for psychosis in light of Ricoeur’s and Kristeva’s philosophy of language and subjectivity

Narrative, life writing, and healing: the therapeutic functions of storytelling.

Mysteries of Creative Process: Explorations at Work and in Daily Life

- Therapeutic writing

- Life writing

- Literary advice

- Therapeutic culture

- Gillie Bolton, Celia Hunt

- Kate Thompson

- Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Introduction

In The Author is Not Dead (2008), Micheline Wandor extensively cites Gillie Bolton’s writing advice for starting authors, a six-minute freewriting exercise, as an example for what creative writing should not be:

For most creative writing teachers, the tone and content of the above is probably not at all problematic. However, this does not come from a CW textbook. It is taken from a patient’s leaflet in a GP surgery, used to help with ‘anxious’ or ‘depressed’ patients. In that context, it may be couched in the most productive way. But the fact that it is indistinguishable from CW advice, should give us all pause. This extract leads into the heart of CW methodology, which is suspended in an uncomfortable contradiction in the Romantic/therapy axis. (Wandor 2008 , pp. 118–119)

In the eyes of Wandor, and of poet and creative writing scholar Nancy Kuhl, good creative writing is about language and craft, rather than about self-expression. While this may be a legitimate therapeutic aim, it is detrimental for the field of creative writing. Creative writing for therapeutic reasons (hereafter “therapeutic writing” or TW) indiscriminately praises all creative efforts, leading to uncritical, unproductive, and overly self-referential writing. Contrary to Wandor and Kuhl, we consider TW handbooks as a subgenre of the contemporary CW handbooks selections which caters to a “niche” of illness and disability narrative writing, which is increasingly becoming part of the field of memoir writing (Couser 2012 , p. 12). At the same time, we will argue that TW handbooks can potentially reach a surprisingly broad and diverse audience of patients, aspiring writers, counselors, creative writing teachers, and qualitative researchers experimenting with new methods of “writing as inquiry” (Richardson and St. Pierre 2005 ). In the twenty-first century, in the wake of the so-called memoir boom, therapeutic writing has left the therapy room and entered the commercial sphere, as a relatively large and stable market for illness and disability narratives has developed (Rak 2013 ). While Kuhl deplores that the “connection between creativity and psychotherapy is relativist and deeply marketplace oriented” (Kuhl 2005 , p. 10), we seek to draw attention not only to the long history and diversity of TW, but also to the possibilities that it can entail.

In the present chapter, we will focus on three of the most important advice oeuvres in this field. Gillie Bolton has published widely on how every person, especially medical professionals and their patients, can benefit from expressive and exploratory writing. Kate Thompson explicitly focuses on journal writing as a therapeutic tool, and Celia Hunt is the founder of a postgraduate program in creative writing and personal development at the University of Sussex. All three authors have been published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers (JKP), a leading international publisher of professional, academic, and self-help books in the field of neurological and cognitive differences. Combining both textual and contextual analysis, we will investigate how the how-to books relate to the therapeutic and self-help ethos as well as to more literary forms of creative writing, and how they negotiate the ideas of becoming a writer, craft, therapy, and self-expression. We will argue that therapeutic writing advice serves as a formal and ideological framework which allows, guides, and also “coaxes” subjects to talk and think about the self, illness, and disability in a particular way (Van Goidsenhoven and Masschelein 2017 , p. 4). While this can be regarded as constraining, the institutional context of JKP also consistently encourages writers to become authors, and thus, against the explicit advice of its handbook authors, to make their personal writings public.

Therapeutic Writing: A Longstanding History and a Heterogeneous Field

The link between writing and health can be traced back to Antiquity, with Apollo as the god of both poetry and medicine, and with practices such as the Laments of Ancient Greece (Sijakovic 2011 ), and the supplication of the Ancient Egyptian through letter writing to the gods to heal diseases. (Williamson and Wright 2018 ). In his essay “Self Writing,” Michel Foucault shows how writing (and reading) in Greco-Roman culture was associated with meditation and how it functioned as a technique of caring for the self and of sustaining “the art of living” (Foucault 1997 , pp. 208–209). 1 Today, the popularity of creative writing as therapy and as a transformative healing purposes is associated with a society immersed in a culture of self-help, confession, and emotionalism, in which the therapeutic discourse has become a major code to express, shape, and guide self-hood (Illouz 2008 , p. 6; Gilmore 2001 ; McGee 2005 ).

In the past four decades, there has been an explosion of interest in the history and practice of creative writing for therapeutic, transformative, and healing purposes, not only from counselors, clinicians, academics, and writers, but also from researchers, who have examined its psychological, social, and emotional benefits. Thus, TW has become an academic, therapeutic, and creative field in its own right, albeit a heterogeneous one. Even those involved, as Anni Raw et al. argue, conceptualize, perceive, and interpret the practice in many different ways (Raw et al. 2012 , p. 97). 2 As a result, the terminology used to refer to therapeutic writing practices ranges from “creative (life) writing for therapeutic purposes,” to “therapeutic creative writing,” “personal expressive and explorative writing,” “expressive writing,” “programmed writing,” “controlled writing,” and so on. Likewise, the definitions may highlight different aspects: transformational and health outcomes, self-expression, or the dichotomy between creativity and craft. Therapeutic writing involves a variety of professions, sites, approaches, and goals. Workshops can be organized as one-to-one sessions, or as groups, led by a writing facilitator who can also be a professional author, a creative writing teacher, as well as a clinician, a health practitioner such as a nurse, a social worker, or therapist. TW can be embedded within another therapeutic trajectory, or it can serve as a therapy on its own. It can take place anywhere according to the maxim that “you only need pen and paper,” and the structure and principles can be adapted to specific groups: prisoners, refugees, children, psychiatric patients, etc. The approaches of TW workshops range from using narrative and psychodynamic models of counseling, to more informal and intuitive styles of practice. Participants are referred to as patients, clients, or service users. Some methods focus on writing by people with mental illnesses (e.g., depression, anxiety, schizophrenia), or somatic illnesses (e.g., asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, immunity), prioritizing either social or aesthetic outcomes, or a combination of the two. Finally, different genres can be chosen for the writing itself, such as journal writing, autobiography, poetry, song lyrics, drama, and letter writing.

Considering this diversity, it is not surprising that academic research on therapeutic writing is found in various disciplines, especially in journals devoted to the intersection between arts and health, journals focused on different forms of therapy, and journals on life writing. Broadly speaking, there are two approaches of the phenomenon: On the one hand exists the quantitative approach of experimental psychologists, who have conducted randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of TW as a therapeutic tool while on the other hand, within more qualitative-oriented research found in educational studies (and more recently in literary and cultural studies), scholars develop a more holistic view of self-development and creativity. 3

Programmed Versus Non-restrictive Writing

A pioneer of the first type of approach is social psychologist James Pennebaker, who, along with colleagues, experimented with what they call “expressive writing” in relation to psychical and emotional health. In order to measure the effects of expressive writing, the participants’ blood pressure readings, heart rates, and self-reports of mood and physical symptoms are gathered before and after each writing session. Many variations of the Pennebaker procedure have been developed since. 4 The majority of these research projects and therapeutic set-ups work with short writing tasks that are restrictive and highly standardized, hence the term “programmed writing” (L’Abate 2004 ; Smyth 1998 ). The many attempts to systematically prove the effect of therapeutic writing and the preoccupation for quantitative outcomes are likely to go hand in hand with an effort to prove to the effectiveness of art to funding agencies or to more broadly promote its usefulness for society (Swinnen 2016 , p. 1379; Williamson and Wright 2018 ). After years of developing and conducting randomized controlled trials, internationally and across different populations, there seems to be evidence that therapeutic writing produces beneficial effects for patients, although it is not (yet?) clear why this is the case (Hustvedt 2016 , p. 101).

In contrast to the experimental paradigm and its “programmed writing,” a more qualitative approach focuses on so-called non-restrictive writing. The psychological discourse, with its emphasis on empirical evidence and concrete terminology, here gives way to a more humanist and ambiguous vocabulary, using words as such as “soul” (Chavis 2011 , p. 12), “inner picture” (Thompson 2011 , p. 41), “intuition” (Bolton 1999 , p. 35), and phrases like “a page full of tears” (ibid., p. 174), “speaking from the heart” (Moss 2012 , p. 247), and “the art of freefall” (Turner-Vesselago 2013 , p. 37). The research and workshops mostly stem from the idea that the aim of creativity is expression of the self. 5 The rationale follows that writing opens up a “window to the soul” and to the “personal truths” of the sufferer (in this case the person in need of therapy), as Bolton claims: “Writing offers a powerful avenue towards finding out what one thinks, feels, knows, understands, remembers” (Bolton et al. 2006 , p. 3).

Authors in this paradigm favor variable and eclectic writing experiments, indicated as a “multi-faceted” practice (Sampson 2004 , p. 17) or a “multidimensional jigsaw” (Bolton 2011 , p. 9). Workshops are explicitly client-centered and based upon a meaningful relation between client and facilitator, paying attention to imagination and creativity (Bolton, Hunt), to artistic merit in terms of the specific qualities of writing as an act and process (Sampson), and in some cases also to craft (Freely, Hustvedt). Underlying the different approaches, however, is the emphasis on the therapeutic effects of these workshops and on mental and physical well-being they afford. Whereas the experimental approach addresses an academic or specialist audience, the qualitative approaches draw broader audiences of both academics and practitioners, facilitators as well as writers. For this reason, TW advice authors commonly evolve from creating more specialist books (in terms of content) to more popular works such as handbooks. This evolution can be viewed in light of two tendencies: the professionalization of TW, and the pervasiveness of therapeutic culture.

Since the 1980s, in the Anglo-American world TW has been institutionalized by two professional organizations: The National Association for Poetry Therapy (NAPT) in the USA, and The Association for Literary Arts in Personal Development (Lapidus) in the UK. These organizations offer training programs for candidates who boast a double background in psychology (or counseling) and in literature, developing standards, guidelines, and set research agendas. Lapidus is part of the Arts Council policy on literature provision in England, and the academic Journal of Poetry Therapy , edited by Nicholas Mazza, serves as the official mouthpiece of the NAPT. In the twenty-first century, TW as a discipline entered many academic programs in both Medical Humanities 6 and in Narrative Medicine. 7

TW handbooks also fit in with what many studies have described as the “triumph” of therapeutic discourse, usually based on a psychoanalytic understanding of self and society, in the twentieth century. 8 Psychology is not just a body of knowledge produced by formal organizations and experts, and its vocabulary has widely entered into social and cultural life via multiple institutional arenas and mass media. In Saving the Modern Soul, Eva Illouz analyzes the intersections of therapy, self-help, and autobiographical discourse (Illouz 2008 , pp. 7–8). She argues that the combination of popular psychology and the cultural industries has led to the mass-production of objects, like TW handbooks. This has led to the widespread distribution of therapeutic discourse, which has shaped a new qualitative language and interpretative framework to think the self and others (ibid., p. 155). 9 In Illouz’s view, therapeutic culture is a “structure of feeling,” an inchoate, pre-ideological mental structure that is expressed in cultural objects (ibid., p. 156). The problem, according to Illouz, is that the discourse of therapeutic self-help is fundamentally sustained by a “narrative of suffering” (ibid., p. 173). Moreover, it resorts to standardized vocabulary and narrative structures which render it “highly compatible with the cultural industry because narrative pegs can be easily changed […] to renewable consumption of ‘narratives’ and ‘narrative fashions’” (ibid., p. 147).

In her study of self-help literature, Micki McGee ( 2005 ) examines how self-help, one of the most commercial forms of therapeutic discourse, is driven both by an optimistic faith in the perfectibility and capacity for continual improvement of the individual, and by a vicious circularity inherent in the very labels it creates and perpetuates. Therapeutic self-help books are presented as necessary guides to attain the intended realizations of the self, or of the desired achievements possible. While providing a (limited) comfort and improvement for the individual reader, they in fact set in motion a never-ending cycle of “work on the self,” in which suffering and victimhood come to define the self (McGee 2005 , p. 142). In what follows, we seek to draw attention to another type of cycle which may arise from the pervasiveness of therapeutic discourse, i.e., a cycle of consumption and activation, that ultimately allows new voices in the public domain and their (limited) forms of agency. In order to do this, we will take a closer look at the work of niche publisher Jessica Kingsley, that published the majority of TW handbook oeuvres in our corpus.

Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Turning Readers into Writers

Founded in 1987 with a bank loan of £5000, and with eight research books addressing an intended audience of social workers and practitioners, JKP has managed to achieve annual revenue growth for the past 30 years, and now publishes over 250 books a year. Because of their commercial success, they were able to open an office in Philadelphia (USA) in 2004, and have been collaborating with Footprint Books in Warriewood (Australia) as well. Jessica Kingsley herself retired in mid-2018, and sold the company to the multinational publishing house Hachette. Despite this change in management, the company policy remains focused on making specialized knowledge available for non-specialists, and the company still presents itself an independent niche publisher of “books that make a difference” (JKP homepage 2019 ). Although JKP is mainly known for its list on autism spectrum, the company now also plays a leading role in distributing books on neurological difference, healthcare, education, art therapies, social justice, counseling, palliative care, adoption, and parenting, with new areas including gender diversity and Chinese medicine. Across these topics, their catalog features accessible academic research alongside memoirs and handbooks, thus fostering an inclusive and non-hierarchical publishing policy.

Kingsley attributes the company’s commercial success to the combination of a focused and programmatic publishing list, her marketing background, and adherence to a clear policy. At the same time, she does not merely want to conform to the market, but rather their press seeks out new directions in order to counter psychiatric stigmas and negative associations with, for instance, neurological differences (Tivnan 2007 ). For the JKP team, it is key to keep in constant touch with several communities, and by maintaining a close relationship, JKP learns about, and integrates new debates and new voices. As Lisa Clark, editorial director at JKP, states: “Being close to communities and the subject helps with identifying emerging topics and to stay abreast of changing language used around the subject” (Headon 2019 ). This way of working contributes to the emancipatory baseline of JKP’s policy and is visible in their catalog which includes memoirs by people who are traditionally not associated with authorship, even though they report about their lives in narrative forms. In this way, experience transforms into expertise (Van Goidsenhoven and Masschelein 2017 , p. 7).

However, this emancipatory stance has its limits. Although JKP is a niche publisher, it is not an experimental house. Its goal is not only to give voice to authors/communities, but also to create a public, and to sell. This means that JKP is not only looking for existing communities, but also actively creates a community. Today it is common for publishers to invest in reading communities and the construction of a brand profile, but JKP’s efforts to build a community with a highly specific target group are striking. Readers are addressed through intimate issues articulated in a sentimental mode that nonetheless exceeds the personal, and fosters recognition and understanding. 10 What is at stake here, is a form of community where readers are invited to share their experiences in such a way that the line between reading and writing becomes profoundly blurred. On the JKP blog, for instance, author Vanessa Rogers shared her writing tips for aspiring (life writing) authors. The post was accompanied by the straightforward message that “if you’re feeling inspired feel free to send in your proposal to [email protected]” (Rogers 2013 ).

Another manner of blurring reading and writing is through the large portfolio of advice books about creative life writing and therapeutic writing that actively shape the kind of publications that JKP seeks. Finding language to discuss (or even reflect upon) neurological difference or painful events in life is generally difficult, as is writing down your life story. To lower this threshold, JKP offers advice through books about writing, both creative and therapeutic. Twenty-two writing handbooks, published between 1998 and 2016, covering genres like poetry, journal, autobiography, and creative fiction, are included in the Arts Therapies catalog, alongside books on Play Therapy, Drama therapy and Story making, Dance Therapy, Music Therapy, Art Therapy, Mental Health, and Trauma and Wellbeing, addressing professional as well as general audiences. 11 Some of the handbooks are part of a series edited by Gillie Bolton, “Writing for Therapy and Personal Development,” which is framed as “appropriate for therapeutic, healthcare, or creative writing practitioners and facilitators, and for individual writers or courses” (Bolton 2011 , back cover).

The Arts Therapies catalog is dominated by “quest narratives” and “triumph narratives” as the most popular plot structures in the context of illness and disability narratives. 12 The quest story is mostly interpreted as a story that addresses suffering directly, that urges readers to accept failure, illness, or disability, and to use them to their own advantage (Frank 1995 , p. 115). Importantly, the JKP catalog neither focuses on the medical side of the healing process, in which a physician plays the most important role, nor on so-called supercrips, a term for people with an illness or disability who “nonetheless” excel at something like sports or science. Instead, the quest narratives are used to emphasize the positive aspects of being different, to focus on coping strategies in order to overcome obstacles in the interaction between an individual and society, and to highlight the promise of attainable progress and improvement. These formats and storylines are reinforced by paratextual elements, such as the titles that frequently feature phrases like “my way through,” “transformation through,” “healing power of creative expression,” “writing routes,” “writing works,” and “creative solutions for life.” The book covers, glossy and colorful with soft-covers depicting flowers, hearts, upward-leading staircases, writing angels, notebooks, and pens, are strikingly similar to other popular CW handbooks. Their two most recent handbooks, which are more geared toward fiction, both depict drawings of old-fashioned typewriters with colorful letters flying out, suggesting that writing is not just something to do in order to feel better, but also for fun.

The publisher’s explicit foregrounding of formats like the quest and triumph narrative, both in content and in form, can be read as a negotiation with the marketplace, since these stories are more likely to become bestsellers than stories that connote stasis or chaos (Frank 1995 , p. 83). The repetition of formats creates uniformity, which, along with offering a standardized vocabulary for complex and diverse topics, are strategies commonly used by cultural intermediaries like publishers. JKP’s approach nonetheless stands out because it effectively opens up possibilities for new types of voices, who in their writings, to some degree, resist standardization (Van Goidsenhoven and Masschelein 2017 , pp. 15–16). The TW handbooks published by JKP mirror and highlight this ambivalence, and they diverge from other popular CW handbooks in that they are more focused on process than on product: The handbooks encourage subjects to write purely for themselves, not for publication, even though the context of JKP implicitly upholds this as a possibility.

Three Therapeutic Writing Oeuvres: Gillie Bolton, Kate Thompson, and Celia Hunt

Gillie Bolton, a British consultant in therapeutic and reflective writing, works largely but not exclusively, in health care settings. She comes from a background of teaching creative writing, which she combines in her handbooks with pop-psychology and self-help, and has written eight books, five of which are advice books. All published with JKP (three monographs and two edited volumes), those advice books are currently the most popular handbooks in the field of TW, covering genres from journaling, poetry, prose, and autobiography. They are accessible, geared toward a wide audience, and aim to be both informative and practical.

Bolton’s first advice book ( 1999 ) mainly focuses on the connection between theory and practice, but it already contains exercises and practical information. The two following advice books, Writing Works (2006) and Writing Routes ( 2011 ), are co-edited with Victoria Field and Kate Thompson. They are framed as essential roadmaps, containing a huge amount of examples, among which more than seventy clients/patients who share their writings and experiences. Her two latest advice books, Write yourself (2011) and The Writer ’s Key (2014), are designed as traditional literary advice guides, written in a hands-on and directive style wherein the reader/writer is always openly addressed and every chapter ends with Write! , “a menu of suggestions and strategies” to start writing (Bolton 2014 , p. 15). The directive tone is also visible in the text design and typography. Bolton uses, for instance, many lists describing what one must do and capitals letters in order to stress rules or techniques. 13 In all her handbooks, she explicitly states that the book chapters can be read and used in any order, depending on the reader/writer’s needs. All books contain appendices in which the exercises are arranged by genre (e.g., unsent letters, AlphaPoems, Diary), by client group (e.g., cancer patients, children, or the elderly), and by theme (e.g., childhood, illness, color).

At the same time, Bolton’s exercises are also organized in a “developmental way” (Bolton 2014 , p. 15), offering several foundational exercises which are important to begin with writing. One of Bolton’s most popular foundational exercises is, for instance, a CW-based exercise called the “Six Minute Write” (Bolton 2011 , p. 33), a sort of free (intuitive) writing to overcome beginner’s blocks. While Bolton’s main focus is on creating exercises for writing workshops with therapeutic goals, the handbooks also pay attention to writing as “a way of life” (Bolton et al. 2006 , p. 230). Entire passages are devoted to the act of choosing the best place to write or even the ideal notebook or pen: “Writing materials are significant. Different equipment is likely to create different writings with very different impacts” (Bolton 2014 , p. 41). Important for Bolton is that this way of life is attainable for everyone, since everyone can write: “If you trust yourself you cannot write the wrong thing” (Bolton 1999 , p. 11). This is in line with the democratic idea of self-help, a discourse which pervades Bolton’s advice books, for instance, through the use of certain metaphors such as “the key to unlock […] the secrets” and to “open the door” to your “life solutions” (Bolton 2014 , p. 17), or finding the key to help the writer to return “to the relationship with the self in a direct and immediate way” (Bolton et al. 2006 , p. 27). Also typical for the self-help discourse is the circular quest of continual improvement and reflection. Working on the self is presented as an endless process which “goes round and round in circles – excitingly and dramatically” (Bolton 1999 , p. 87). After all, “we keep on facing life changes” (Bolton 2011 , p. 8), and “when life becomes difficult […] the wisest person to turn to is often oneself” (Bolton 2014 , p. 17). Accordingly, the writing facilitator is like a “midwife” or a “helper-on-the-way” (Bolton et al. 2006 , p. 14). who “support(s). the writers in their own personal explorations and expressions” (Bolton 1999 , p. 128).

Together with Bolton and Field, Kate Thompson is the co-editor of Writing Routes and Writing Works . Unlike Bolton, she does not come from a creative writing background, but is a psychotherapist and certified journal therapist, whose main work is clinical private practice (both online and face-to-face counseling) and supervision of other therapists. Therapeutic Journal Writing: An Introduction for Professionals (2011) is her single-authored handbook in which she develops journal writing as a therapeutic tool. Contrary to Bolton’s advice, the book only focuses on journal writing as a genre, based on a protocol trademarked by Thompson.

The first chapters of Therapeutic Journal Writing offer the theoretical background, history, and key concepts of therapeutic journal writing. 14 Once the basics are covered, the focus shifts toward the techniques and protocol, each technique being elaborated in great detail in a separate chapter, illustrated with cases and ending with a “journal prompt” to get the reader started. The techniques are presented in a progressive way from structured to freer techniques, a principle Thompson borrows from Kathleen Adams’s The Way of the Journal ( 1998 ). 15 The reason for this progressive structure is to offer enough encouragement for less-experienced practitioners and more vulnerable clients. 16 Once the entire protocol has been followed, a personal structured repertoire consisting of several techniques can be assembled and used according to the writers’ own judgments as to what methods are appropriate for different times and for different reasons.

While Thompson consistently uses the word “technique,” and emphasizes the importance of formats and structured exercises, journaling, for her, is also an undeniable creative and personal act (Thompson 2011 , p. 15). This allows her to connect the protocol of expressive writing and the open strategy of handbooks, which further advocate writing as lifestyle, symbolized by the appropriate writing implements (ibid., pp. 41, 43). She encourages her readers to personalize the exercises, and reassures them that “you cannot write the wrong thing” (ibid., p. 53). In typical self-help style, the personal dimension of writing is related to her own experiences: “At each stage of my professional journey I have used therapeutic journal writing […] with myself to monitor my own process both in my professional practice and in my life” (ibid., p. 14). In an article on JKP’s blog that offers some advice on writing for yourself and with a group, Thompson also elaborates on her personal experiences:

My own journey from childhood diary writing in the 1960s to journal therapist in the 21 st century has indeed been an almost lifelong process. This journey continues today, propelling me into the modern work of blogs and internet therapy. (Thompson 2012 )

The integration of personal experience enlivens the protocol, but it also clearly frames journal writing as a technology for monitoring the self in terms of continual improvement (change, healing, growth) and a never-ending cycle of work on the self (from childhood until the present), which can even have benefits for someone’s professional career.

JKP’s third handbook author to be discussed, Celia Hunt, is Emeritus Reader in Continuing Education (Creative Writing) at the Centre for Community Engagement at University of Sussex Here, where she has set up the Certificate in Creative Writing as well as an MA program in Creative Writing and Personal Development with an associated research program in 1996. Hunt was also a founding member and first Chair of Lapidus. At the end of the twentieth century, Hunt published two TW advice books with JKP: The Self on the Page: Theory and Practice of Creative Writing in Personal Development (1998, with Fiona Sampson) and Therapeutic Dimensions of Autobiography in Creative Writing (2000). The former is an edited volume with a triple focus of providing an overview of different TW practices, on the application between theory and practice, and on possible exploration frameworks. The second book is based on Hunt’s doctoral dissertation, and gives a account of her trajectory from a more creative writing context to a therapeutic one. This book starts with a description of her work with students enrolled in an academic Creative Writing and Personal Development course, which means that their writings were graded, and that the therapeutic benefit of writing was present “by chance rather than by design” (Hunt 2000 , p. 186), but it led her to connecting creative writing work with writing as a tool in self-therapy or psychotherapy.

Hunt is convinced that literary techniques can stimulate self-knowledge and therapeutic effects: “Fictionalizing from ourselves and finding a satisfactory form for our fictions helps us to engage more deeply with our inner life, opening up possibilities for greater insight and self-understanding” (Hunt and Sampson 1998 , p. 33). The link between creative writing and self-understanding is of course not new. Hunt consistently refers to seminal CW handbooks, like Peter Elbow’s Writing Without Teachers ( 1973 ) and Dorothea Brande’s Becoming a Writer (1981), which claim that writing appeals to one deepest self. If you want to become a writer, so Brande states, it is best to be a balanced person, and the inverse is true as well: when a writer encounters problems with writing, there will be primarily personal problems, rather than a deficit in equipment and technique (Brande 1981 , p. 33). While Brande and Elbow state that writers need to work on themselves in order to become writers, Hunt turns this around and argues that it is important to (learn to) write in order to achieve a healthy and balanced self.

Stylistically, Hunt’s advice books are dense, providing detailed descriptions of writing exercises, 17 alongside psychoanalytic explanations. Contrary to Bolton and Thompson, Hunt offers a theoretical model of therapeutic writing, based on a “Horneyan literary psychoanalytic approach,” which suggests that writing “throw(s) light on the present structure of the psyche through increasing intellectual understanding and emotional experiencing of the defenses in operation” (Hunt 2000 , p. 160). 18 This psychoanalytic background is linked to Hunt’s post-structuralist literary and narratological frameworks, signaled by narratological concepts like “implied author,” “showing,” and “telling,” and references to scholars like Roland Barthes, Norman Friedman, and Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan. This makes her books less accessible, but then again, accessibility is not her primary intention. In Hunt’s view, TW as practice is not suitable for everyone:

Writing of this kind would clearly not be appropriate for use with all patients or clients, as they would need to feel relatively at ease with the written word and preferably to have some familiarity with writing techniques. I would suggest that this approach might be particularly useful for writers who present with writer’s block, or for people who are accustomed to keeping a diary, or are more generally interested in the literary arts. (ibid., p. 181)

Unlike her fellow authors, Hunt’s focus is on enriching TW with insights from creative writing, literary theory, and psychoanalysis.

Our brief characterization of three important TW advice authors and their oeuvres provides insight into the diversity and eclecticism of TW as a field, even in a commercial context such as JKP. Authors connect different traditions and framework, ranging from psychoanalysis, psychology, literary theory, and self-help, to underpin their theory and methods. Despite their diversity, however, they share a strong focus on writing as a process, rather than as product. For Hunt, writing-as-art and writing-as-therapy are not mutually exclusive (Hunt 2000 , p. 185), but they are qualitatively different. Writing a story for therapeutic purposes is first and foremost done to gain more insight in one’s own feelings. It is only by reworking these first drafts, that communication with the writer within can be achieved. Writing to create a literary product is, therefore, a long and laborious work, which is not for everyone. Likewise, Bolton agrees that a text is a construction that must be worked upon in order to achieve a product capable of communicating effectively with the reader/listener (Bolton 2011 , p. 48). The process is what counts, Bolton states, because patients will not benefit from the idea that they are creating a form of art as soon as they pick up a pen. On the contrary, therapeutic writing is primarily a private practice (Bolton 1999 , p. 225; Thompson 2011 , p. 52).