Think you can get into a top-10 school? Take our chance-me calculator... if you dare. 🔥

Last updated March 22, 2024

Every piece we write is researched and vetted by a former admissions officer. Read about our mission to pull back the admissions curtain.

Blog > Common App , Essay Advice , Personal Statement > How to Write a College Essay About ADHD

How to Write a College Essay About ADHD

Admissions officer reviewed by Ben Bousquet, M.Ed Former Vanderbilt University

Written by Ben Bousquet, M.Ed Former Vanderbilt University Admissions

Key Takeaway

ADHD and ADD are becoming more prevalent, more frequently diagnosed, and better understood.

The exact number of college students with ADHD is unclear with estimates ranging wildly from just 2% to 16% or higher.

Regardless of the raw numbers, an ADHD diagnosis feels very personal, and it is not surprising that many students consider writing a college essay about ADHD.

If you are thinking about writing about ADHD, consider these three approaches. From our experience in admissions offices, we’ve found them to be the most successful.

First, a Note on the Additional Information Section

Before we get into the three approaches, I want to note that your Common App personal statement isn’t the only place you can communicate information about your experiences to admissions officers.

You can also use the additional information section.

The additional information section is less formal than your personal statement. It doesn’t have to be in essay format, and what you write there will simply give your admissions officers context. In other words, admissions officers won’t be evaluating what you write in the additional information section in the same way they’ll evaluate your personal statement.

You might opt to put information about your ADHD (or any other health or mental health situations) in the additional information section so that admissions officers are still aware of your experiences but you still have the flexibility to write your personal statement on whatever topic you choose.

Three Ways to Write Your College Essay About ADHD

If you feel like the additional information section isn’t your best bet and you’d prefer to write about ADHD in your personal statement or a supplemental essay, you might find one of the following approaches helpful.

1) Using ADHD to understand your trends in high school and looking optimistically towards college

This approach takes the reader on a journey from struggle and confusion in earlier years, through a diagnosis and the subsequent fallout, to the present with more wisdom and better grades, and then ends on a note about the future and what college will hold.

If you were diagnosed somewhere between 8th and 10th grade, this approach might work well for you. It can help you contextualize a dip in grades at the beginning of high school and emphasize that your upward grade trend is here to stay.

The last part—looking optimistically towards college—is an important component of this approach because you want to signal to admissions officers that you’ve learned to manage the challenges you’ve faced in the past and are excited about the future.

I will warn you: there is a possible downside to this approach. Because it’s a clear way to communicate grade blips in your application, it is one of the most common ways to write a college essay about ADHD. Common doesn’t mean it’s bad or off-limits, but it does mean that your essay will have to work harder to stand out.

2) ADHD as a positive

Many students with ADHD tell us about the benefits of their diagnosis. If you have ADHD, you can probably relate.

Students tend to name strengths like quick, creative problem-solving, compassion and empathy, a vivid imagination, or a keen ability to observe details that others usually miss. Those are all great traits for college (and beyond).

If you identify a strength of your ADHD, your essay could focus less on the journey through the diagnosis and more on what your brain does really well. You can let an admissions officer into your world by leading them through your thought processes or through a particular instance of innovation.

Doing so will reveal to admissions officers something that makes you unique, and you’ll be able to write seamlessly about a core strength that’s important to you. Of course, taking this approach will also help your readers naturally infer why you would do great in college.

3) ADHD helps me empathize with others

Students with ADHD often report feeling more empathetic to others around them. They know what it is like to struggle and can be the first to step up to help others.

If this rings true to you, you might consider taking this approach in your personal statement.

If so, we recommend connecting it to at least one extracurricular or academic achievement to ground your writing in what admissions officers are looking for.

A con to this approach is that many people have more severe challenges than ADHD, so take care to read the room and not overstate your challenge.

Key Takeaways + An Example

If ADHD is a significant part of your story and you’re considering writing your personal statement about it, consider one of these approaches. They’ll help you frame the topic in a way admissions officers will respond to, and you’ll be able to talk about an important part of your life while emphasizing your strengths.

And if you want to read an example of a college essay about ADHD, check out one of our example personal statements, The Old iPhone .

As you go, remember that your job throughout your application is to craft a cohesive narrative —and your personal statement is the anchor of that narrative. How you approach it matters.

Liked that? Try this next.

The Incredible Power of a Cohesive College Application

How A Selective Admissions Office Reads 50k Applications In A Season

12 Common App Essay Examples (Graded by Former Admissions Officers)

How to Write a Personal Statement for Colleges

"the only actually useful chance calculator i’ve seen—plus a crash course on the application review process.".

Irena Smith, Former Stanford Admissions Officer

We built the best admissions chancer in the world . How is it the best? It draws from our experience in top-10 admissions offices to show you how selective admissions actually works.

Need help? Call us at (833) 966-4233

Thriveworks has earned 65+ awards (and counting) for our leading therapy and psychiatry services.

We’re in network with most major insurances – accepting 585+ insurance plans, covering 190 million people nationwide.

Thriveworks offers flexible and convenient therapy services, available both online and in-person nationwide, with psychiatry services accessible in select states.

Find the right provider for you, based on your specific needs and preferences, all online.

If you need assistance booking, we’ll be happy to help — our support team is available 7 days a week.

Discover more

ADHD is my superpower: A personal essay

Our clinical and medical experts , ranging from licensed therapists and counselors to psychiatric nurse practitioners, author our content, in partnership with our editorial team. In addition, we only use authoritative, trusted, and current sources. This ensures we provide valuable resources to our readers. Read our editorial policy for more information.

Thriveworks was established in 2008, with the ultimate goal of helping people live happy and successful lives. We are clinician-founded and clinician-led. In addition to providing exceptional clinical care and customer service, we accomplish our mission by offering important information about mental health and self-improvement.

We are dedicated to providing you with valuable resources that educate and empower you to live better. First, our content is authored by the experts — our editorial team co-writes our content with mental health professionals at Thriveworks, including therapists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and more.

We also enforce a tiered review process in which at least three individuals — two or more being licensed clinical experts — review, edit, and approve each piece of content before it is published. Finally, we frequently update old content to reflect the most up-to-date information.

A Story About a Kid

In 1989, I was 7 years old and just starting first grade. Early in the school year, my teacher arranged a meeting with my parents and stated that she thought that I might be “slow” because I wasn’t performing in class to the same level as the other kids. She even volunteered to my parents that perhaps a “special” class would be better for me at a different school.

Thankfully, my parents rejected the idea that I was “slow” out of hand, as they knew me at home as a bright, talkative, friendly, and curious kid — taking apart our VHS machines and putting them back together, filming and writing short films that I’d shoot with neighborhood kids, messing around with our new Apple IIgs computer!

The school, however, wanted me to see a psychiatrist and have IQ tests done to figure out what was going on. To this day, I remember going to the office and meeting with the team — and I even remember having a blast doing the IQ tests. I remember I solved the block test so fast that the clinician was caught off guard and I had to tell them that I was done — but I also remember them trying to have me repeat numbers back backwards and I could barely do it!

Being Labeled

The prognosis was that I was high intelligence and had attention-deficit disorder (ADD). They removed the hyperactive part because I wasn’t having the type of behavioral problems like running around the classroom (I’ll cover later why I now proudly identify as hyperactive). A week later, my pediatrician started me on Ritalin and I was told several things that really honestly messed me up.

I was told that I had a “learning disability” — which, to 7-year-old me, didn’t make any sense since I LOVED learning! I was told that I would take my tests in a special room so that I’d have fewer distractions. So, the other kids would watch me walk out of the classroom and ask why I left the room when tests were happening — and they, too, were informed that I had a learning disability.

As you can imagine, kids aren’t really lining up to be friends with the “disabled” kid, nor did they hold back on playground taunts around the issue.

These were very early days, long before attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was well known, and long before people had really figured out how to talk to kids with neurodiversities . And as a society, we didn’t really have a concept that someone who has a non-typical brain can be highly functional — it was a time when we didn’t know that the world’s richest man was on the autism spectrum !

Growing Past a Label

I chugged my way through elementary school, then high school, then college — getting consistent B’s and C’s. What strikes me, looking back nearly 30 years later, is just how markedly inconsistent my performance was! In highly interactive environments, or, ironically, the classes that were the most demanding, I did very well! In the classes that moved the slowest or required the most amount of repetition, I floundered.

Like, I got a good grade in the AP Biology course with a TON of memorization, but it was so demanding and the topics were so varied and fast-paced that it kept me engaged! On the opposite spectrum, being in basic algebra the teacher would explain the same simple concept over and over, with rote problem practice was torturously hard to stay focused because the work was so simple.

And that’s where we get to the part explaining why I think of my ADHD as a superpower, and why if you have it, or your kids have it, or your spouse has it… the key to dealing with it is understanding how to harness the way our brains work.

Learning to Thrive with ADHD

Disclaimer : What follows is NOT medical advice, nor is it necessarily 100% accurate. This is my personal experience and how I’ve come to understand my brain via working with my therapist and talking with other people with ADHD.

A Warp Speed Brain

To have ADHD means that your brain is an engine that’s constantly running at high speed. It basically never stops wanting to process information at a high rate. The “attention” part is just an observable set of behaviors when an ADHD person is understimulated. This is also part of why I now openly associate as hyperactive — my brain is hyperactive! It’s constantly on warp speed and won’t go any other speed.

For instance, one of the hardest things for me to do is fill out a paper check. It’s simple, it’s obvious, there is nothing to solve, it just needs to be filled out. By the time I have started writing the first stroke of the first character, my mind is thinking about things that I need to think about. I’m considering what to have for dinner, then I’m thinking about a movie I want to see, then I come up with an email to send — all in a second.

I have to haullll myself out of my alternate universe and back to the task at hand and, like a person hanging on the leash of a horse that’s bolting, I’m struggling to just write out the name of the person who I’m writing the check to! This is why ADHD people tend to have terrible handwriting, we’re not able to just only think about moving the pen, we’re in 1,000 different universes.

On the other hand, this entire blog post was written in less than an hour and all in one sitting. I’m having to think through a thousand aspects all at once. My dialog: “Is this too personal? Maybe you should put a warning about this being a personal discussion? Maybe I shouldn’t share this? Oh, the next section should be about working. Should I keep writing more of these?”

And because there is so much to think through and consider for a public leader like myself to write such a personal post, it’s highly engaging! My engine can run at full speed. I haven’t stood up for the entire hour, and I haven’t engaged in other nervous habits I have like picking things up — I haven’t done any of it!

This is what’s called hyperfocus, and it’s the part of ADHD that can make us potentially far more productive than our peers. I’ve almost arranged my whole life around making sure that I can get myself into hyperfocus as reliably as possible.

Harnessing What My Brain Is Built For

Slow-moving meetings are very difficult for me, but chatting in 20 different chat rooms at the same time on 20 different subjects is very easy for me — so you’ll much more likely see me in chat rooms than scheduling additional meetings. Knowing what my brain is built for helps me organize my schedule, work, and commitments that I sign up for to make sure that I can be as productive as possible.

If you haven’t seen the movie “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” and you are ADHD or love someone who is, you should immediately go watch it! The first time I saw it, I loved it, but I had no idea that one of its writers was diagnosed with ADHD as an adult , and decided to write a sci-fi movie about an ADHD person! The moment I read that it was about having ADHD my heart exploded. It resonated so much with me and it all made sense.

Practically, the only real action in the movie is a woman who needs to file her taxes. Now, don’t get me wrong — it’s a universe-tripping adventure that is incredibly exciting, but if you even take a step back and look at it, really, she was just trying to do her taxes.

But, she has a superpower of being able to travel into universes and be… everywhere all at once. Which is exactly how it feels to be in my mind — my brain is zooming around the universe and it’s visiting different thoughts and ideas and emotions. And if you can learn how to wield that as a power, albeit one that requires careful handling, you can do things that most people would never be able to do!

Co-workers have often positively noted that I see solutions that others miss and I’m able to find a course of action that takes account of multiple possibilities when the future is uncertain (I call it being quantum brained). Those two attributes have led me to create groundbreaking new technologies and build large teams with great open cultures and help solve problems and think strategically.

It took me until I was 39 to realize that ADHD isn’t something that I had to overcome to have the career I’ve had — it’s been my superpower .

Keep up-to-date on the latest in mental health

Tap into the wisdom of our experts — subscribe for exclusive wellness tips and insights.

Blog signup for Active Campaign (blog page)

- Email Address

Published Jul 15, 2022

The information on this page is not intended to replace assistance, diagnosis, or treatment from a clinical or medical professional. Readers are urged to seek professional help if they are struggling with a mental health condition or another health concern.

If you’re in a crisis, do not use this site. Please call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or use these resources to get immediate help.

How to Tackle an Essay (an ADHD-friendly Guide)

6 steps and tips.

Most of the college students I work with have one major assignment type that gets them stuck like no other: the dreaded essay. It has become associated with late nights, requesting extensions (and extensions on extensions), feelings of failure, and lots of time lost staring at a screen. This becomes immensely more stressful when there is a thesis or capstone project that stands between you and graduation.

The good news?

An essay doesn’t have to be the brick wall of doom that it once was. Here are some strategies to break down that wall and construct an essay you feel good about submitting.

Step 1: Remember you’re beginning an essay, not finishing one.

Without realizing it, you might be putting pressure on yourself to have polished ideas flow from your brain onto the paper. There’s a reason schools typically bring up having an outline and a rough draft! Thoughts are rarely organized immediately (even with your neurotypical peers, despite what they may say). Expecting yourself to deliver a publishing-worthy award winner on your first go isn’t realistic. It’s allowed to look messy and unorganized in the beginning! There can be unfinished thoughts, and maybe even arguments you aren’t sure if you want to include. When in doubt, write it down.

Step 2: Review the rubric

Make sure you have a clear understanding of what the assignment is asking you to include and to focus on. If you don’t have an understanding of it, it’s better to find out in advance rather than the night before the assignment is due. The rubric is your anchor and serves as a good guide to know “when you can be done.” If you hit all the marks on the rubric, you’re looking at a good grade.

I highly recommend coming back to the rubric multiple times during the creative process, as it can help you get back on track if you’ve veered off in your writing to something unrelated to the prompt. It can serve as a reminder that it’s time to move onto a different topic - if you’ve hit the full marks for one area, it’s better to go work on another section and return to polish the first section up later. Challenge the perfectionism!

Step 3: Divide and conquer

Writing an essay is not just writing an essay. It typically involves reading through materials, finding sources, creating an argument, editing your work, creating citations, etc. These are all separate tasks that ask our brain to do different things. Instead of switching back and forth (which can be exhausting) try clumping similar tasks together.

For example:

Prepping: Picking a topic, finding resources related to topic, creating an outline

Gathering: reading through materials, placing information into the outline

Assembling: expanding on ideas in the outline, creating an introduction and conclusion

Finishing: Make final edits, review for spelling errors and grammar, create a title page and reference page, if needed.

Step 4: Chunk it up

Now we’re going to divide the work EVEN MORE because it’s also not realistic to expect yourself to assemble the paper all in one sitting. (Well, maybe it is realistic if you’re approaching the deadline, but we want to avoid the feelings of panic if we can.) If you haven’t heard of chunking before, it’s breaking down projects into smaller, more approachable tasks.

This serves multiple functions, but the main two we are focusing on here is:

- it can make it easier to start the task;

- it helps you create a timeline for how long it will take you to finish.

If you chunk it into groups and realize you don’t have enough time if you go at that pace, you’ll know how quickly you’ll need to work to accomplish it in time.

Here are some examples of how the above categories could be chunked up for a standard essay. Make sure you customize chunking to your own preferences and assignment criteria!

Days 1 - 3 : Prep work

- Day 1: Pick a topic & find two resources related to it

- Day 2: Find three more resources related to the topic

- Day 3: Create an outline

Days 4 & 5 : Gather

- Day 4: Read through Resource 1 & 2 and put information into the outline

- Day 5: Read through Resource 3 & 4 and put information into the outline

Days 6 - 8 : Assemble

- Day 6: Create full sentences and expand on Idea 1 and 2

- Day 7: Create full sentences and expand on Idea 3 and write an introduction

- Day 8: Read through all ideas and expand further or make sentence transitions smoother if need be. Write the conclusion

Day 9: Finish

- Day 9: Review work for errors and create a citation page

Hey, we just created an outline about how to make an outline - how meta!

Feel like even that is too overwhelming? Break it down until it feels like you can get started. Of course, you might not have that many days to complete an assignment, but you can do steps or chunks of the day instead (this morning I’ll do x, this afternoon I’ll do y) to accommodate the tighter timeline. For example:

Day 1: Pick a topic

Day 2: Find one resource related to it

Day 3: Find a second resource related to it

Step 5: Efficiently use your resources

There’s nothing worse than stockpiling 30 resources and having 100 pages of notes that can go into an essay. How can you possibly synthesize all of that information with the time given for this class essay? (You can’t.)

Rather than reading “Article A” and pulling all the information you want to use into an “Article A Information Page,” try to be intentional with the information as you go. If you find information that’s relevant to Topic 1 in your paper, put the information there on your outline with (article a) next to it. It doesn’t have to be a full citation, you can do that later, but we don’t want to forget where this information came from; otherwise, that becomes a whole mess.

By putting the information into the outline as you go, you save yourself the step of re-reading all the information you collected and trying to organize it later on.

*Note: If you don’t have topics or arguments created yet, group together similar ideas and you can later sort out which groups you want to move forward with.

Step 6: Do Some Self-Checks

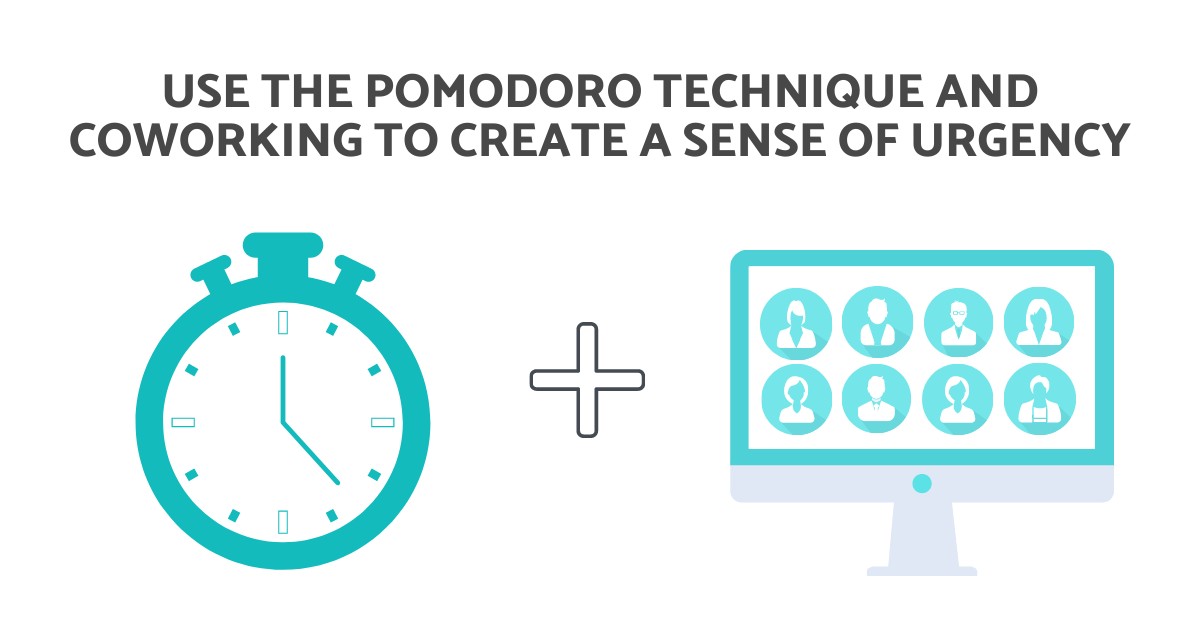

It can be useful to use the Pomodoro method when writing to make sure you’re taking an adequate number of breaks. If you feel like the 25 min work / 5 min break routine breaks you out of your flow, try switching it up to 45 min work / 15 min break. During the breaks, it can be useful to go through some questions to make sure you stay productive:

- How long have I been writing/reading this paragraph?

- Does what I just wrote stay on topic?

- Have I continued the "write now, edit later" mentality to avoid getting stuck while writing the first draft?

- Am I starting to get frustrated or stuck somewhere? Would it benefit me to step away from the paper and give myself time to think rather than forcing it?

- Do I need to pick my energy back up? Should I use this time to get a snack, get some water, stretch it out, or listen to music?

General Tips:

- If you are having a difficult time trying to narrow down a topic, utilize office hours or reach out to your TA/professor to get clarification. Rather than pulling your hair out over what to write about, they might be able to give you some guidance that speeds up the process.

- You can also use (and SHOULD use) office hours for check-ins related to the paper, tell your teacher in advance you’re bringing your rough draft to office hours on Thursday to encourage accountability to get each step done. Not only can you give yourself extra pressure - your teacher can make sure you’re on the right track for the assignment itself.

- For help with citations, there are websites like Easybib.com that can help! Always double check the citation before including it in your paper to make sure the formatting and information is correct.

- If you’re getting stuck at the “actually writing it” phase, using speech-to-text tools can help you start by transcribing your spoken words to paper.

- Many universities have tutoring centers and/or writing centers. If you’re struggling, schedule a time to meet with a tutor. Even if writing itself isn’t tough, having a few tutoring sessions scheduled can help with accountability - knowing you need to have worked on it before the tutoring session is like having mini deadlines. Yay, accountability!

Of course, if writing just isn’t your jam, you may also struggle with motivation . Whatever the challenge is, this semester can be different. Reach out early if you need help - to your professor, a tutor, an ADHD coach , or even a friend or study group. You have a whole team in your corner. You’ve got this, champ!

Explore more

Mastering the Interview Game With ADHD

Top Tips from Our ADHD Coaches & Perspectives from Coachees

5 Womxn in ADHD Research That You Should Know About

Menopause & Adult ADHD

ADHD and Graduate Writing

What this handout is about.

This handout outlines how ADHD can contribute to hitting the wall in graduate school. It describes common executive function challenges that grad students with ADHD might experience, along with tips, strategies, and resources for navigating the writing demands of grad school with ADHD.

Challenges for graduate students with ADHD

Many graduate students hit the wall (lose focus, productivity, and direction) when they reach the proposal, thesis, or dissertation phase—when they have a lot of unstructured time and when their external accountability system is gone. Previously successful strategies aren’t working for them anymore, and they aren’t making satisfactory progress on their research.

In many ways, hitting the wall is a normal part of the grad school experience, but ADHD, whether diagnosed or undiagnosed, can amplify the challenges of graduate school because success depends heavily on executive functioning. ADHD expert Russell Barkley explains that people with ADHD have difficulty with some dimensions of executive function, including working memory, motivation, planning, and problem solving. For grad students, those difficulties may emerge as these kinds of challenges:

- Being forgetful and having difficulty keeping things organized.

- Not remembering anything they’ve read in the last few hours or the last few minutes.

- Not remembering anything they’ve written or the argument they’ve been developing.

- Finding it hard to determine a research topic because all topics are appealing.

- Easily generating lots of new ideas but having difficulty organizing them.

- Being praised for creativity but struggling with coherence in writing, often not noticing logical leaps in their own writing.

- Having difficulty breaking larger projects into smaller chunks and/or accurately estimating the time required for each task.

- Difficulty imposing structure on large blocks of time and finishing anything without externally set deadlines.

- Spending an inordinate amount of time (like 5 hours) developing the perfect plan for accomplishing tasks (like 3 hours of reading).

- Having trouble switching tasks—working for hours on one thing (like refining one sentence), often with no awareness of time passing.

- Conversely, having trouble focusing on a single task–being easily distracted by external or internal competitors for their attention.

- Being extremely sensitive to or upset by criticism, even when it’s meant to be constructive.

- Struggling with advisor communications, especially when the advisors don’t have a strict structure, e.g., establishing priorities, setting clear timelines, enforcing deadlines, providing timely feedback, etc.

If you experience these challenges in a way that is persistent and problematic, check out our ADHD resources page and consider talking to our ADHD specialists at the Learning Center to talk through how you can regain or maintain focus and productivity.

Strategies for graduate students with ADHD

Writing a thesis or dissertation is a long, complex process. The list below contains a variety of strategies that have been helpful to grad students with ADHD. Experiment with the suggestions below to find what works best for you.

Reading and researching

Screen reading software allows you to see and hear the words simultaneously. You can control the pace of reading to match your focus. If it’s easier to focus while you’re physically active, try using a screen reader so you can listen to journal articles while you take a walk or a run or while you knit or doodle–or whatever movement helps you focus. Find more information about screen readers and everything they can do on the ARS Technology page .

Citation management systems can help you keep your sources organized. Most systems enable you to enter notes, add tags, save pdfs, and search. Some allow you to annotate pdfs, export to other platforms, or collaborate on projects. See the UNC Health Sciences Library comparison of citation managers to learn more about options and support.

Synthesis matrix is a fancy way of saying “spreadsheet,” but it’s a spreadsheet that helps you keep your notes organized. Set the spreadsheet up with a column for the full citations and additional columns for themes, like “research question,” “subjects,” “theoretical perspective,” or anything that you could productively document. The synthesis matrix allows you to look at all of the notes on a single theme across multiple publications, making it easier for you to analyze and synthesize. It saves you the trouble of shuffling through lots of highlighted articles or random pieces of paper with scribbled notes. See these example matrices on Autism , Culturally Responsive Pedagogy , and Translingualism .

Topic selection

Concept maps (also called mind maps) represent information visually through diagrams, flowcharts, timelines, etc. They can help you document ideas and see relationships you might be interested in pursuing. See examples on the Learning Center’s Concept Map handout . Search the internet for “concept-mapping software” or “mind-mapping software” to see your many choices.

Advisor meetings can help you reign in all of the interesting possibilities and focus on a viable, manageable project. Try to narrow the topics down to 3-5 and discuss them with your advisor. Be ready to explain why each interests you and how you would see the project developing. Work with your advisor to set goals and a check-in schedule to help you stay on track. They can also help you sort what needs to be considered now and what’s beyond the scope of the dissertation—tempting though it may be to include everything possible.

Eat the elephant one bite at a time. Break the dissertation project down into bite-sized pieces so you don’t get overwhelmed by the enormity of the whole project. The pieces can be parts of the text (e.g., the introduction) or the process (e.g., brainstorming or formatting tables). Enlist your advisor, other grad students, or anyone you think might help you figure out manageable chunks to work on, discuss reasonable times for completion, and help you set up accountability systems.

Tame perfectionism and separate the processes . Writers with ADHD will often try to perfect a single sentence before moving on to the next one, to the point that it’s debilitating. Start with drafting for ideas, knowing that you’re going to write a lot of sentences that will change later. Allow the ideas to flow, then set aside times to revise for ideas and to polish the prose.

List questions you could answer as a way of brainstorming and organizing information.

Make a slideshow of your key points for each section, chapter, or the entire dissertation. Hit the highlights without getting mired in the details as you draft the big picture.

Give a presentation to an imaginary (or real) audience to help you flesh out your ideas and try to articulate them coherently. The presentation can be planned or spontaneous as a brainstorming strategy. Give your presentation out loud and use dictation software to capture your thoughts.

Use dictation software to transcribe your speech into words on a screen. If your brain moves faster than your fingers can type, or if you constantly backspace over imperfectly written sentences, dictation software can capture the thoughts as they come to you and preserve all of your phrasings. You can review, organize, and revise later. Any device with a microphone (like your phone) will do the trick. See various speech to text tools on the ARS Technology page .

Turn off the monitor and force yourself to write for five, ten, twenty minutes, or however long it takes to dump your brain onto the screen. If you can’t see the words, you can’t scrutinize and delete them prematurely.

Use the Pomodoro technique . Set a timer for 25 minutes, write as much as you can during that time, take a five-minute break, and then do it again. After four 25-minute segments, take a longer break. The timer puts a helpful limit on the writing session that can motivate you to produce. It also keeps you aware of the passage of time, helping you stay focused and keeping your time more structured.

Sprints or marathons? Some people find it helpful to break down the writing process into smaller tasks and work on a number of tasks in smaller sprints. However, some people with ADHD find managing a number of tasks overwhelming, so for them, a “marathon write” may be a good idea. A marathon write doesn’t have to mean last-minute writing. Try to plan ahead, stock up on food for as many days as you plan to write, and think about how you’ll care for yourself during the long stretch of writing.

Minimize distractions . Turn off the internet, find a suitable place (quiet, ambient noise, etc.), minimize disruptions from other people (family, office mates, etc.), and use noise-canceling headphones or earplugs if they help. If you catch your thoughts wandering, write down whatever is distracting and you can attend to it later when you finish.

Seek feedback for clarity . Mind-wandering is a big asset for people with ADHD as it boosts creativity. Expansive, big-picture thinking is also an asset because it allows you to imagine complex systems. However, these things can also make graduate students with ADHD struggle with maintaining logical coherence. When you ask for feedback, specify logical coherence as a concern so your reader has a focus. If you’d like to look at your logic before you seek feedback, see our 2-minute video on reverse outlining .

Seek feedback for community . Talking to people about your ideas for writing will help you stay connected at a time when it’s easy to fade into a dark hole. Check out this handout on getting feedback .

Time management and accountability

Enlist your advisor . Graduate students with ADHD might worry about the perception that they’re “gaming the system” if they disclose their ADHD. Or they might struggle with an advisor with a more hands-off mentoring style. It will be helpful to be explicit about your neurodiversity and your potential need for a structure. Ask your advisor to clarify the expectations specifically (even quantify them), and work with them to come up with a clear timeline and a regular check-in schedule.

Enlist other mentors . Your advisor may be less understanding and/or may not be able to provide enough structure, or you may think it’s a good idea to have more than one person on your structure team. Look for other mentors on your faculty (inside or outside of your committee), and talk to senior grad students about their strategies.

Pay attention to your body rhythms . When do you feel most creative? Most focused? Most energetic? Or the least creative, focused, energetic? What activities could you engage in during those times? How can you do them consistently?

Think about task vs. time . It can be difficult to estimate how long a task is going to take, so think about setting a time limit for working on something. Set a timer, work for that amount of time, and change tasks when the time is over.

Tame hyperfocus . If you have trouble switching tasks, ask a friend or colleague to “interrupt” you, or figure out a system you can use to interrupt yourself. For example, when you find yourself trying to fix a sentence for 30 minutes, you can call a friend for a brief conversation about another topic. People with ADHD often find this helps them to look at the work from a more objective perspective when they return to it.

Set SMART goals . Check out the handout on setting SMART goals to help you set up a regular research and writing routine.

Set up a reward system . Tie your research or writing goal to an enjoyable reward. Note that it can also be pre-ward – something you do beforehand that will help you feel refreshed and motivated to work.

Find accountability buddies . These can be people you update on your progress or people you meet with to get work done together. Oftentimes, the simple presence of other people is able to motivate and keep us focused. This “body-doubling” strategy is particularly helpful for people with ADHD. Look for events like the Dissertation Boot Camp or IME Writing Wednesdays .

Find virtual accountability partners . There are a number of online platforms to connect you with virtual work partners. See this article on strategies and things to consider.

Use productivity and focus apps . Check out some recommendations among the Learning Center’s ADHD/LD Resources . To find the best options for you, try Googling “Apps for focus and productivity” to find reviews of timers and other focus apps.

Learn more about accountability . See the Learning Center’s Accountability Strategies page for great information and resources.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Barkley, R. (2022, July 11). What is executive function? 7 deficits tied to ADHD . ADDitude: Inside the ADHD Mind. https://www.additudemag.com/7-executive-function-deficits-linked-to-adhd/

Hallowell, E. and Ratey, J. (2021). ADHD 2.0: New science and essential strategies for thriving with distraction—from childhood through adulthood . Random House Books.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

P: 323-325-1525 | E: [email protected]

- ADHD Coworking Sessions

- ADHD Coaching

- ADHD Coaching For College Students

- Strengths-Based Approach

- How To Get Started

ADHD College Students: Use This Strategy To Write Papers

ADHD College Students : Here at ADHD Collective, we love highlighting the experiences and perspectives of like-minded people with ADHD. Izzy Walker started attending the weekly coworking sessions we launched in March 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic began. She showed up week after week and put in the hard work as she neared the semester’s end at University. When she accepted my invitation to share what she learned with our readers, I was thrilled, and I know you will be too. Please share Izzy’s helpful tips in your social circles, if you know a college student with ADHD who could benefit.

ADHD and College

Making it to university was a milestone I often thought I would never make. However, my experience was gloomy. Everything was disproportionately difficult, lectures were a confusing din, and every assignment was a mammoth struggle.

I changed university naively thinking it would be different somewhere else. It wasn’t. But it was there at my new university that my story of hope began, as one friend saw the immense struggle I was having and suggested that it could be ADHD.

This conversation was a catalyst for change, and set the ball rolling for me in my journey. It led to a heck of a lot of personal research, but also a meeting with an Educational Psychologist who after a series of testing gave me the diagnosis of ADHD and Dyspraxia .

When I read these words I felt an odd, overwhelming sense of relief. I wasn’t dumb, lazy, incapable, or ‘just not cut out to study’.

School reports year after year would echo the words, ‘distracted and distracting’, ‘capable but often off-task’, and ‘constantly questioning’. On paper I was doing well, the product of my work was good, so no flags had been raised, but deep down behind closed doors I was not doing well, the process was far from good. This has been the case throughout the whole of my education, and I just put it down to my capability.

Since diagnosis I have finished my 1 st assignment, and then my 2 nd , and then my 3 rd , and I am now looking onwards to my final year before being a qualified teacher. This time with hope and acceptance of who I am and who I can be with the right strategies and support in place.

Here are some that I have found the most game-changing when working on projects/assignments:

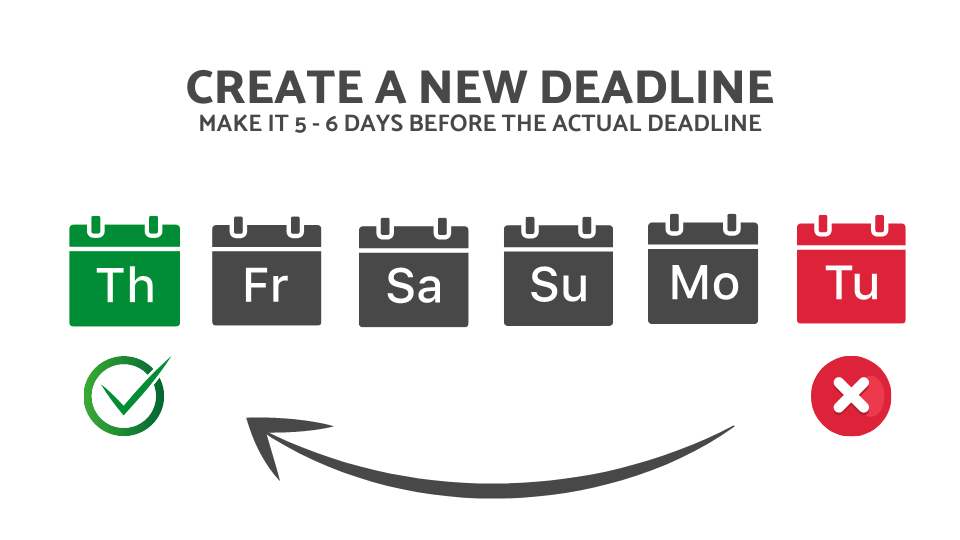

Give Yourself a New Deadline

I set myself a deadline a few days (at least) before the actual one. I have a real tendency to be scrambling right to the last minute and this helps avoid a lot of stress.

The whole point of this was to prevent a lot of unnecessary scrambling and stress. This also gave me time to edit (more on that later).

As much as you can, it’s helpful to treat this earlier date as your actual deadline. One way I did this was only scheduling this earlier date on the calendar so it felt more real.

By finishing 5-6 days early, it offered me a window of time for editing and getting it ready to turn in. It also gave time to improve the paper should I have any middle of the night revelations…which I so often do!

Break Your Paper Down into Smaller Pieces

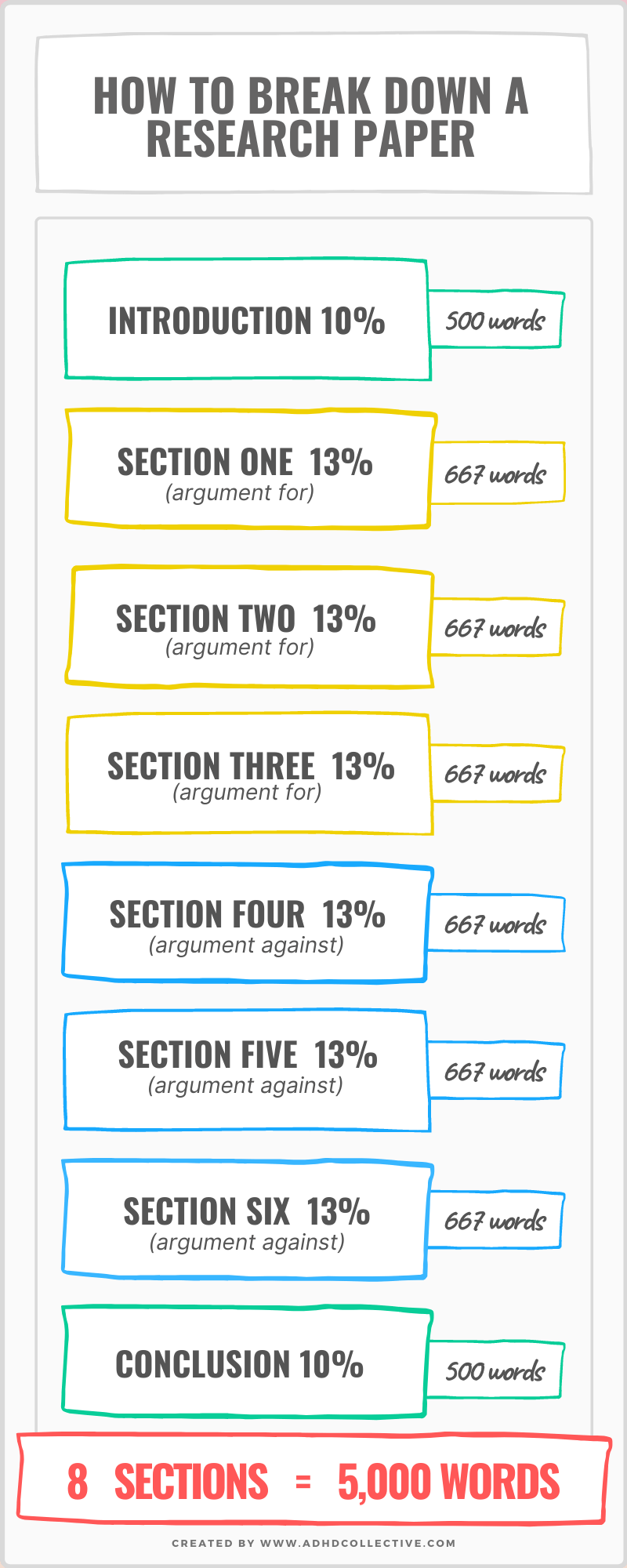

When I was presented with a 5,000 word assignment I felt immediately overwhelmed. I broke the assignment down into sections and assigned a word count to each one.

when I considered what my paper actually entailed, it didn’t seem so bad. Here's what the requirements consisted of:

- Introduction - 1 section

- Argument FOR - 3 sections

- Argument AGAINST - 3 sections

- Conclusion - 1 Section

- Total length of the paper had to be 5,000 words.

It may seem very overly meticulous, but by spending 30 minutes doing this prevented what could have been HOURS of cutting back word count in the editing stages, and could also run the risk of having no clear structure.

I am a waffler, so without this structure, I would probably have gone WAY over the word limit anyway.

I also went one step further by writing a title for each of the points (on my plan only) and any key things I wanted/needed to mention.

For example, in an assignment on why outdoor learning should be a part of the primary curriculum, my points would be titled ‘educational benefits’, ‘health benefits’ and ‘social benefits’.

The contrary points could be titled ‘behavioural issues’, ‘lack of funding’, and ‘lack of training’. By breaking it down into bite size chunks I felt it was much more manageable.

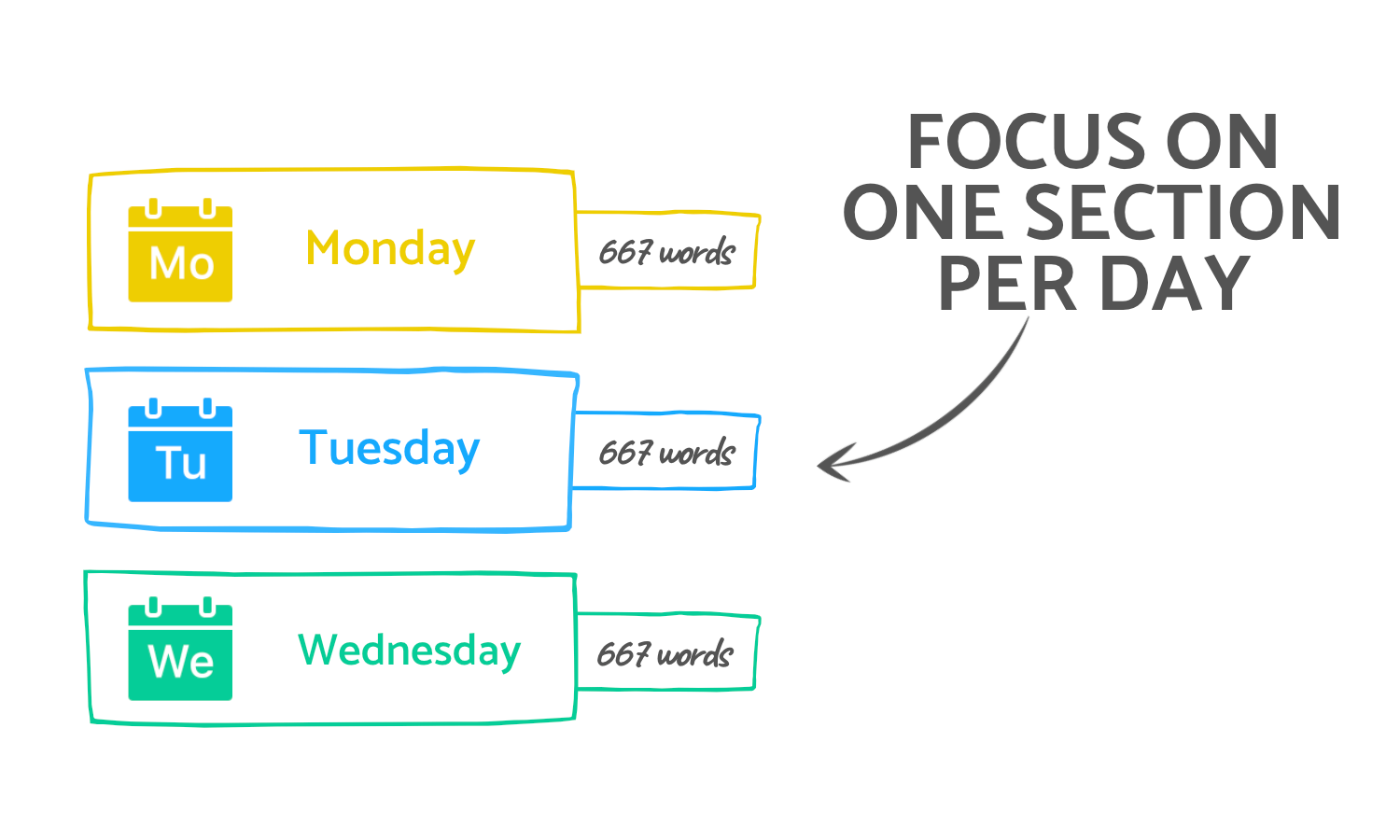

Focus on One Section a Day

After breaking it down, I dedicated a day to each of the sections. For example, intro – Monday, section 1 – Tuesday, etc.

From my experience, I have found that having a specific measurable target makes it almost like a game. I found it very motivating watching the word count for that section going down as I typed.

By scheduling the sections out and putting them in my calendar, it allowed me to know when this assignment could realistically be finished by, rather than taking a guess and hoping for the best.

When I woke up, I was thinking, 'I have to write 650 words today!’ rather than ‘oh my goodness 5,000 words!?

I would recommend doing this step as soon as you get the assignment and the deadline date…even if you do nothing else towards it, so that you know when you must start.

Set a Mid-Way Checkpoint

it will save you a LOT of time in the editing stages if you do a little editing as you go along.

With the word count on this particular assignment being so big, I thought it would be wise to set a mid-way checkpoint to read through everything so far and make changes as necessary.

Normally, this would be done at the end but I knew I would have lost all interest and motivation by this point…so it would be better to save myself such a huge job. This also filled me with confidence because when I was writing the second half of the assignment and needed the extra boost, I knew that the first half was to a good standard.

Do Something Every Day (No Matter How Small)

I’m not going to lie, not everyday was as straightforward as ‘write one section a day’.

Some days I was crippled by demotivation, lethargy and not wanting to do ANYTHING.

The key times I noticed this was if I had worked too hard the previous day or if I had hit a difficult part. Believe me, working TOO hard is a THING.

My biggest piece of advice is…know your limits!

I’m no ADHD scientist, but I find my brain must be working harder because of the increased effort I am investing to even stand a chance of being able to concentrate.

Whilst I may feel just about fine at the time, the next day it takes its toll…big time…and maybe the work I did in my ‘overtime’ wasn’t even of the best quality anyway.

"If you just aren’t feeling it, do just one sentence, or find just one piece of theory. Just do one something ..."

This is another reason why my structured plan was really useful because it prevented me from unnecessarily going overboard…and meant that there was no real reason to anyway as I was already on track to finish on time.

If it’s the latter reason, that I’ve hit a difficult part, then there is nothing worse than putting it off another day because this ‘mental wall’ will just get HIGHER.

What did I find useful? If you just aren’t feeling it…do just ONE sentence, or find just ONE piece of theory you just use. Just do ONE something…so then you can feel at least partially accomplished and it’s not a blank section for when you do get back to it.

Best case scenario…that ONE something, could roll into TWO or THREE or FOUR somethings…and before you know it that section is done. Often it is just starting that is the difficult bit.

But worse case scenario…you tried and you can give it another shot tomorrow when your brain is a bit fresher. Productive days happen, utilise these and ride the waves…as do unproductive days…don’t allow the guilt to creep in.

Declutter Your Workspace

I even went to the extreme of removing the pen pot off the desk…in front of me all I had was paper, 1 pen, my lamp, and my laptop.

Minimalism has been a saviour for me during this time of discovering what works for me and what doesn’t. I’ve come to the conclusion that reducing physical clutter consequently reduces mental clutter. I also found the inverse to be true too, clearing my physical space gave me mental clarity.

Whilst this is a visible practice in much of my life, it is especially apparent with my workspace . You’d be amazed what I can get distracted by when writing an assignment…even something as small and monotonous as a pen pot!

Firstly…I would recommend to ALWAYS have a work station with a proper chair when you are writing an assignment and never work from your bed. You must set yourself up for success.

Secondly, I have only the bare essentials in front of me…a pen, a lamp, paper, and my laptop. By keeping it minimal it also means it is easily portable if you want to ‘hot seat’ in your own house if you get bored of that scenery!

Use ADHD Coworking Sessions (and the Pomodoro Technique)

At the start of lockdown I stumbled upon a weekly coworking group ran by Adam from ADHD Collective. I can honestly put down a lot of my success to this…it was amazing!

Firstly, I felt so understood because the group was aimed at people with ADHD. This meant that everyone could share their experiences and not feel judged, but instead find themselves in a supportive community where they could also ask advice.

Each session was 2 hours long and attracted between 4 and 12 people, depending on the week.

It would start with each person sharing (with specifics) what task they wanted to achieve within the next 25 minute block.

By being specific it allowed for a strong element of accountability because at the end of the block, Adam, the ADHD coach and group host would check your progress and whether you had achieved what you wanted to achieve.

Working in 25 minute blocks is often referred to as the Pomodoro Technique . Whilst everyone else in the group is sharing their progress, it gives your brain the opportunity for a short break before starting the next block.

By having short bursts of activity I was able to concentrate and thus achieve more than I would have done if I tried to work for hours without breaks.

Additionally, having the accountability was an incentive for me because it was motivation and almost turned it into a game to try and get the activity finished in time.

I hope these college writing tips give you several options that might help you with your ADHD experience.

Now over to you!

Share the tools, strategies, and tips in the comments below that have helped you in your own journey with ADHD and college writing!

Izzy Walker

Izzy Walker is a trainee teacher in her final year at University in Newcastle, UK. When not studying, she can be found on spontaneous adventures, and meeting new people! To follow her as she navigates through the adventures of ADHD, student life, and teacher...find her on Instagram at @if.walker

Thank you so much.

I am an over 50 returning student trying to finish my undergraduate degree. I never knew I had ADHD until I started taking classes that required retention, organizing, and WRITING. At times, I even wondered if I lacked the skills to even finish. I, at times, self sabotage myself of success because of my struggles. I truly appreciate you sharing your experience. I’ve become desperate and will try anything at this point. I’m just glad to know that others understand my journey. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for this! In addition to these, I also find it really helpful to keep a “Random thoughts” notepad near me to jot down unrelated urges as I have them. Things like “refill water bottle” or “text Casey back” will still be there in 25 minutes, and knowing in advance that thoughts like ‘this will only take a second’ are lies makes them easier to put on the back burner.

Wow. Thank you, so much, Izzy. I developed ADHD only 3 years ago from a medication. I also decided to go back to college as a mom of 3 boys and the mental exhaustion and burnout is no joke. Papers have been the most challenging and this is the single most helpful tool I’ve found yet. I could feel the relief wash over me as I read through your guide. I feel inspired to tackle my papers in a new way now.

Hi, I am a mid-career student here going back for an MA part-time, while also working. I’ve never been formally diagnosed, but I tick all the boxes and I know now it is why I struggled with papers in college the first time around and why I developed so many systems to be organized in my work life. Was feeling a little burned out today while writing an academic paper and was looking for advice. I was amazed to see that your system is very similar to what I’ve been doing for myself to get through paper-writing! It’s reinforcing in a very good way. Thank you for sharing this. Best of luck to everyone with finding the solutions and tricks that work for them.

Hi Espy, appreciate the comment. Very cool to hear your intuitive system is similar (nice intuition!). If an additional accountability/community component would ever be useful, you’re always invited to our Wednesday ADHD Coworking Sessions. They’re free and we do them every Wednesday (you can sign up for upcoming sessions here: https://adhdcollective.com/adhd-coworking-session-online/ ). Would love to have you, Espy!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

7 Tips for College Students With ADHD

Verywell / Laura Porter

Qualities for Student Success

- ADHD and College

- Academic Tips

- Social Tips

Every autumn, thousands of students move away from the structure and safety of home to the freedoms of college life. While it's an exciting time filled with many possibilities for learning and growth, it can also be challenging academically and socially—especially for college students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Learn some of the challenges that college students with ADHD face, as well as strategies that can be used to overcome these obstacles. This includes learning how to study with ADHD and taking certain actions to foster friendships with other students.

Sarah D. Wright , ADHD coach and author of "Fidget to Focus: Outwit Your Boredom—Sensory Strategies for Living with ADD," explains that successful students usually have four qualities that help them achieve their goals:

- Sticking with things even when the going gets tough (perseverance)

- Ability to delay gratification and focus on the big picture

- Time management and organizational skills

- Striking the right balance between fun and work

These particular skills, however, don’t come easily to people with ADHD. One of the hallmarks of this mental health condition is impaired executive functioning . This means that students with ADHD may struggle with staying organized, sticking to a plan, and managing time effectively.

How ADHD Affects College Students

College students often face more responsibilities, less structured time, increased distractions, and new social situations—all while lacking access to many of the support systems they had in high school. Impaired executive functioning can make handling these changes a bit harder for students with ADHD, resulting in:

- Poor academic performance and achievement : Students with ADHD frequently report feeling dissatisfied with their grades. They may struggle in their classes due to difficulties starting and completing tasks, disorganization, problems remembering assignments, difficulty memorizing facts, and trouble working on lengthy papers or complex math problems .

- Troubles with time management : Students with ADHD often have irregular lifestyles that result from poor time management. This can create problems with being on time, preparing and planning for the future, and prioritizing tasks.

- Difficulty regulating and managing emotions : Students with ADHD also often struggle with social issues, negative thoughts, and poor self-esteem. Some ADHD symptoms can make friendships and other relationships more challenging while worrying about these issues contributes to poor self-image.

The good news is that these areas of executive function can be improved. For most college students with ADHD, the problem isn’t in knowing what to do, it's getting it done. Developing strategies that focus on this goal can lead to positive academic and social effects.

Tips for Succeeding in College With ADHD

There are several strategies you can use to help stay on track if you are a college student with ADHD. Here are seven that Wright suggests.

1. Take Steps to Start the Day on Time

There are three main factors that contribute to being late in the morning: Getting up late, getting sidetracked, and being disorganized.

If Getting Up Late Is an Issue

Set two alarms to go off in sequence. Put the first alarm across the room so you have to get out of bed to turn it off. Put the second where you know it will bother your roommates, increasing the consequences if you don’t get out of bed and turn it off. Set both alarms to go off early so you can take your time getting ready.

If Getting Sidetracked Is an Issue

If certain actions tend to derail you, like checking your email or reading the news, make it a rule that those activities must wait until later in the day so you can stay on task . Also, figure out how much time you need to dress, eat, and get organized, then set alarms or other reminders to cue these tasks.

Three options are:

- Use a music mix as a timer . If you have 30 minutes to get ready, the schedule might look like this: wash and dress to songs 1 to 3, eat breakfast to songs 4 to 6, get your stuff together during song 7, and walk out the door by song 8. This option works best if you use the same mix every morning.

- Use your phone or buy a programmable reminder watch so your alarms are always nearby.

- Put a big wall clock in your room where you can easily see it . If your room is part of a suite with a common room and bathroom, put wall clocks in those spaces as well.

If Being Disorganized Is the Issue

Create a "launch pad" by your door. Collect all of the things you’ll need the next day the night before (like your backpack and keys), and put them on the pad so you can grab them and go. Include a note to help you remember important events for the day, such as an appointment or quiz.

2. Work With Your Urge to Procrastinate

Though it may sound counterproductive, if you feel the urge to procrastinate , go with it. When you have ADHD, sometimes things only get done right before they're due. At that point, nothing has higher priority, increasing the urgency and consequences if you don’t do them now. These qualities are what can finally make a task doable, so work with them.

If you plan to procrastinate, it's important to stack the deck so you can pull it off. For example, if you have to write a paper, make sure you’ve done the reading or research in advance and have some idea of what you want to write. Next, figure out how many hours you’ll need, block those hours out in your schedule, and then, with the deadline in sight, sit down and do it.

Understanding your tendency to procrastinate with ADHD can help you plan ahead so you won't be left scrambling to finish projects at the last minute.

3. Study Smarter, Not Harder

Boredom and working memory issues can make studying a bit more challenging for students with ADHD. Rather than trying harder to force the information into your head, get creative with the learning process.

If you're wondering how to study with ADHD, research shows that multi-modal learning or learning via a variety of different methods can be helpful. Ideas include:

- Highlight text with different-colored pens.

- Make doodles when taking notes.

- Record notes as voice memos and listen to them as you walk across campus.

- Use mnemonics to create funny ways to remember facts.

- Stand up while you study.

- Read assignments aloud using an expressive (not boring) voice.

- If you can, get the audio version of a book you need to read and listen to it while you take notes and/or exercise.

- Work with a study buddy.

These won't all work for every person, but try mixing up your strategies and see what happens. Taking study breaks every couple of hours and getting enough sleep are also part of studying smarter, not harder.

Sleep impacts learning in two main ways. First, sleep deprivation has a negative impact on short-term memory , which is what you use to learn the materials when you study. Second, sleep is needed to move short-term memories into long-term memory, which is what you rely on when it's time to take the test.

Sleep is important for both short- and long-term memory, making it critical for both learning new material and recalling what you've learned.

4. Schedule Your Study Time

Many students with ADHD are highly intelligent. They can pull off a passing grade, or even a good one, in high school by cramming their studies in the night before a test.

This strategy doesn't work as well in college since cramming reduces your ability to retain what you've learned long-term . This can make it harder to remember what you need to know once you enter your field of choice.

One good rule of thumb for college students is to study two to two-and-a-half hours per week for every course credit hour. Put this time into your schedule to make sure you have it.

5. Plan and Prioritize Your Time

It may sound strange, but it's important to plan time to plan. If you don’t develop this habit, you may find yourself always being reactive with your day rather than proactive—the latter of which can help you take more control over your schedule .

Set aside time on Monday mornings to develop a high-level plan for the week, using Friday mornings to plan for the weekend. In addition, do a daily review of your plan over breakfast—possibly adding pertinent details—to make sure you know what’s coming your way that day.

When making your plans, differentiate between what you need to do and everything that can or should be done. Prioritize what needs to be done first, taking care of these items before moving on to lower-priority tasks on your list.

6. Implement Strategies to Stick to Your Plan

With ADHD, sticking to a plan is often difficult. If you like rewards, use them to assist with this. For instance, you might tell yourself, "I’ll read for two hours, then go to the coffee house." Having something to look forward to can make it easier to muster through your studies.

If you’re competitive, use this personality trait instead. Pick another student in your class whom you want to do better than and go for it. If you know that you respond to social pressure, make plans to study with classmates so you won’t let them down. Or hire a tutor so you have structured study time.

Research suggests that focusing on skills related to time management , target planning, goal setting, organization, and problem-solving can all be helpful for students with ADHD.

Hiring a coach can also be beneficial. There is growing evidence, both research-based and anecdotal, that supports ADHD coaching as a vital strategy in helping students learn to plan, prioritize, and persist in following their plans.

This type of coaching is sometimes described as a form of life coaching influenced by cognitive behavioral-type therapy , which helps people develop behaviors, skills, and strategies to better deal with ADHD symptoms. It can lead to greater self-determination and direction, reduced feelings of overwhelm and anxiety, and increased self-confidence and self-sufficiency.

7. Manage Your Medication

One study found that only around 53% of college students with ADHD adhere to their medication plan. Poor medication adherence can have serious consequences, contributing to poor academic performance and decreased graduation rates.

Steps you can take to stay on top of your ADHD medications include:

- Find a local healthcare provider : Regularly monitoring your medications helps ensure that you are at the best dosage for you. If you're going to school a long way from home, find a local healthcare provider to meet with regularly. You can also schedule regular visits with your university's health services.

- Find a local pharmacy : Determine where you'll order and pick up your medication. Set reminders on your phone so you know when to refill your prescription. You may also be able to sign up for text reminders.

- Store medications safely : Abuse of ADHD medications is on the rise on college campuses, even though this can result in high blood pressure, increased feelings of anger and distrust, trouble sleeping, and even strokes. Keep your ADHD medications in a safe location and never share them with others.

- Set reminders to take your medication : If you are struggling to take your medication as prescribed, consider using a reminder app or setting reminders on your phone.

Research points to medication as the most effective and available ADHD treatment option. However, it's important to talk to your care provider to decide the best treatment approach for your individual situation and needs.

Social Strategies for Students With ADHD

Interpersonal challenges are also common for college students with ADHD. While being out on your own for the first time can be exciting, this mental health condition can lead to difficulties in building and maintaining friendships .

CHADD—which stands for Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, an organization funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—offers these tips:

- Remember that you aren't the only one who feels the way you do . Other students may be feeling just as excited (and overwhelmed) as you. During orientation, help them feel more comfortable by being friendly and listening when they share their concerns.

- Look for opportunities to meet and interact with others . You might make new friends in class, in your dorm, at the school cafeteria, or at other places on campus. View each of these locations as an opportunity to expand your social network .

- Find activities or clubs to join. Colleges and universities are great places to explore hobbies and meet people who share your interests. Check out bulletin boards on campus or look at your school's website to learn more about the options that are available.

- Stay in contact with your current friends . Don't let your high school friendships fade into the background just because you're at college. While you're busy with new things and might not see each other every day, stay in touch by phone, text, social media, or email. Your current friends can be great sources of social support .

A Word From Verywell

Being proactive and getting strategies in place early on can increase your success as a college student with ADHD, both academically and socially. This can help make your transition to college life a happy, successful, and productive time.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. College students with ADHD .

Pineda-Alhucema W, Aristizabal E, Escudero-Cabarcas J, Acosta-López JE, Vélez JI. Executive function and theory of mind in children with ADHD: a systematic review . Neuropsychol Rev . 2018;28:341-358. doi:10.1007/s11065-018-9381-9

Kwon SJ, Kim Y, Kwak Y. Difficulties faced by university students with self-reported symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative study . Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health . 2018;12(12). doi:10.1186/s13034-018-0218-3

Ward N, Paul E, Watson P, et al. Enhanced learning through multimodal training: Evidence from a comprehensive cognitive, physical fitness, and neuroscience intervention . Sci Rep . 2017;7(1):5808. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06237-5

Rommelse N, van der Kruijs M, Damhuis J, et al. An evidence-based perspective on the validity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of high intelligence . Neurosci Biobehav Rev . 2016;71:21-47. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.032

Walck-Shannon EM, Rowell SF, Frey RF. To what extent do study habits relate to performance? CBE Life Sci Educ . 2021;20(1):ar6. doi:10.1187/cbe.20-05-0091

Wennberg B, Janeslätt G, Kjellberg A, Gustafsson P. Effectiveness of time-related interventions in children with ADHD aged 9-15 years: a randomized controlled study . Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2018;27:329-342. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-1052-5

Prevatt F. Coaching for college students with ADHD . Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2016;18(12):110. doi:10.1007/s11920-016-0751-9

ADHD medication adherence in college students-a call to action for clinicians and researchers: Commentary on 'transition to college and adherence to prescribed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication': erratum . J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2018;39(3):269. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000568

Hall CL, Valentine AZ, Groom MJ, et al. The clinical utility of the continuous performance test and objective measures of activity for diagnosing and monitoring ADHD in children: a systematic review . Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2016;25:677-699. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0798-x

Stanford Medicine. Abuse of prescription ADHD medicines rising on college campuses .

Caye A, Swanson JM, Coghill D, Rohde LA. Treatment strategies for ADHD: an evidence-based guide to select optimal treatment . Mol Psychiatry . 2019;24:390-408. doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0116-3

McKee TE. Peer relationships in undergraduates with ADHD symptomatology: selection and quality of friendships . J Atten Disord . 2017;21(12):1020-1029. doi:10.1177/1087054714554934

CHADD. Succeeding in college with ADD .

Rotz R, Wright SD. Fidget to focus: Outwit your boredom: Sensory strategies for living with ADD .

By Keath Low Keath Low, MA, is a therapist and clinical scientist with the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities at the University of North Carolina. She specializes in treatment of ADD/ADHD.

What Happens When ADHD Goes to College?

Here's how to plan for success..

Posted June 24, 2022 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- What Is ADHD?

- Take our ADHD Test

- Find a therapist to help with ADHD

- A UK group published a consensus statement with recommendations for supporting college students with ADHD.

- The key points encourage adequate screening, assessment, and treatment and education of on-campus staff and educators about the nature of ADHD.

- Existing medical and psychosocial treatments are increasingly targeting the unique stressors facing college students with ADHD.

- Adult ADHD-focused therapies focused on the immediate goals of navigating college will generalize to later adult roles.

A group of colleagues in the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN) recently published a consensus statement about supporting college students with ADHD. 1 The author list for the consensus statement is comprised mostly, if not completely, of researchers who also provide clinical services, and thus they know what university students with ADHD (and other young adults with ADHD) are up against as they assume adult roles.

Recalling the early days of the University of Pennsylvania Adult ADHD Treatment and Research Program, I’d estimate that college students comprised two-thirds of our initial cohort of clients. These were students who were only identified with ADHD after facing significant difficulties in college far and above any typical adjustment issues. They often reported simmering difficulties in earlier levels of school that were masked by intelligence (combined with less demanding work), support of family who ensured homework completion, more structure at home and school, or simply doing enough in high school to get by. Once they got to college, however, many of these students faced newfound levels of stress and difficulty that shed light on these heretofore veiled difficulties that could now be understood as undiagnosed ADHD. (There were some other students with ADHD who had been diagnosed before college but sought services as part of their continuity of care in college.)

General Recommendations from the College Students with ADHD Consensus Statement

The main takeaways from the UKAAN review and recommendations are:

- ADHD should be a separate category for disability determination, not as a learning or other difference.

- Screenings for ADHD should be performed for students presenting for disability services with specific learning differences or autistic spectrum issues or who seek help for depression and/or anxiety with learning problems.

- Staff training about the nature of ADHD and its assessment, treatment, and effects on learning is needed to heighten awareness and reduce stigma .

- Rapid access to services is a serious issue in terms of long waits for ADHD-related services via the NHS that needs to be addressed.

- Higher- education specialists also need training on the screen and diagnostic assessment of ADHD in college-aged adults in order to facilitate identification and referral for specialized treatments.

- The use of evidence-supported, multimodal treatment options, including psychoeducation, environmental adjustments/academic accommodations, medication treatments, academic coaching , psychosocial treatments and counseling (cognitive-behavior/dialectical-behavior therapies), and mindful interventions are helpful for young adults.

Facing College With ADHD: It Is More Than Just the Classroom

Our program’s early experiences with college students with ADHD also shed light on the college transition being as much if not more of a test of students’ time management and organizational skills as it was about knowledge and intellect. Unfortunately, difficulties with the former often undermine abilities in the latter. What’s more, most college students move away from home to attend college and must take on many more roles and responsibilities for managing their affairs and dealing with various distractions, temptations, and the stress of emerging adulthood at the same time they face a new level of education.

Help for College Students With ADHD

Encouragingly, there has been increased awareness of the effects of ADHD in college students, as well as other learning and mental health issues. Ever more treatments for ADHD are being adapted to the unique needs of college students with ADHD. As always with ADHD, medications can be highly effective. To date, I don’t think there is a medication that will make you want to read Beowulf , though. Psychosocial treatments, such as cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), are helpful for the implementation of coping strategies as well as dealing with stress and other emotional aspects of adjusting to and handling college. ADHD coaching is another option well-suited to supporting college students.

On-campus learning centers often offer support in the form of organization and time management strategies and other, more specific learning strategies in both group and individual settings. Targeted tutoring for particular subjects can also be helpful. Specific psychoeducation evaluations are required to petition campus disability services offices for formal academic accommodations based on documented learning disabilities, as the diagnosis of ADHD alone is not deemed sufficient justification, at least for schools that strictly follow Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines for postsecondary education. Nonetheless, there are informal coping steps that students can take, such as sitting near the front in large lectures, making use of instructor and teaching assistant office hours, and resources and regular meetings at the campus learning center.

In addition to an evidence-based CBT program for college students 2 , rumor has it that several other respected clinician-researchers in the ADHD community are developing materials designed to support college students with ADHD. A benefit of addressing ADHD in college is that every day provides an opportunity to implement and practice the coping strategies with academics, but that generalizes to other areas of life. As I had said about our program’s clinical experience with college students with ADHD, we provided early intervention for adult ADHD.

1 Sedgwick-Müller et al. (2022). University students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a consensus statement from the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN). BMC Psychiatry, 22 , 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03898-z

2 Anastopoulos et al. (2020). CBT for college students with ADHD: A clinical guide to ACCESS . Springer.

J. Russell Ramsay, Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist with an independent virtual practice. He is retired as a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain