The Chinese Exclusion Act: Annotated

The passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 marked the first time the United States prohibited immigration based on ethnicity and national origin.

The passage and signing of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act set a number of precedents in United States immigration law. First, it barred an entire nation’s population from entering the US, as well as from obtaining citizenship, based on ethnic (then “racial”) origin. Secondly, it superseded any and all laws regarding Chinese immigration, some of which had been passed by individual states (most notably California). The period of exclusion of Chinese immigrants by the US didn’t truly end until 1965.

For Asian American and Pacific Island History Month, JSTOR Daily has annotated the Exclusion Act with scholarship that examines the political, social, and economic forces in play preceding and following the escalation of anti-Chinese legislation and violence in the US, a period roughly beginning during the California Gold Rush of 1848. All articles are free to read and access, and we hope this illuminates a sometimes obscured and shameful part of American history for our readers, students, and teachers.

________________________________________________________________

An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese.

Whereas in the opinion of the Government of the United States the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory thereof: Therefore,

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled , That from and after the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and until the expiration of ten years next after the passage of this act, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States be, and the same is hereby, suspended; and during such suspension it shall not be lawful for any Chinese laborer to come, or having so come after the expiration of said ninety days to remain within the United States.

SEC. 2. That the master of any vessel who shall knowingly bring within the United States on such vessel, and land or permit to be landed, any Chinese laborer, from any foreign port or place, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not more than five hundred dollars for each and every such Chinese laborer so brought, and maybe also imprisoned for a term not exceeding one year.

SEC. 3. That the two foregoing sections shall not apply to Chinese laborers who were in the United States on the seventeenth day of November, eighteen hundred and eighty , or who shall have come into the same before the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and who shall produce to such master before going on board such vessel, and shall produce to the collector of the port in the United States at which such vessel shall arrive, the evidence hereinafter in this act required of his being one of the laborers in this section mentioned; nor shall the two foregoing sections apply to the case of any master whose vessel, being bound to a port not within the United States, shall come within the jurisdiction of the United States by reason of being in distress or in stress of weather, or touching at any port of the United States on its voyage to any foreign port or place: Provided, That all Chinese laborers brought on such vessel shall depart with the vessel on leaving port.

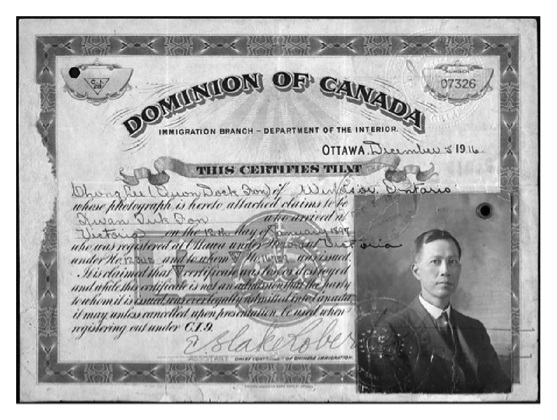

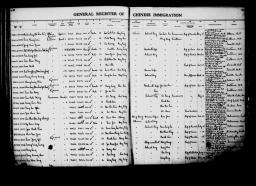

SEC. 4. That for the purpose of properly identifying Chinese laborers who were in the United States on the seventeenth day of November eighteen hundred and eighty, or who shall have come into the same before the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and in order to furnish them with the proper evidence of their right to go from and come to the United States of their free will and accord, as provided by the treaty between the United States and China dated November seventeenth, eighteen hundred and eighty, the collector of customs of the district from which any such Chinese laborer shall depart from the United States shall, in person or by deputy, go on board each vessel having on board any such Chinese laborers and cleared or about to sail from his district for a foreign port, and on such vessel make a list of all such Chinese laborers, which shall be entered in registry-books to be kept for that purpose, in which shall be stated the name, age, occupation, last place of residence, physical marks of peculiarities, and all facts necessary for the identification of each of such Chinese laborers, which books shall be safely kept in the custom-house.; and every such Chinese laborer so departing from the United States shall be entitled to, and shall receive, free of any charge or cost upon application therefor, from the collector or his deputy, at the time such list is taken, a certificate, signed by the collector or his deputy and attested by his seal of office, in such form as the Secretary of the Treasury shall prescribe, which certificate shall contain a statement of the name, age, occupation, last place of residence, persona description, and facts of identification of the Chinese laborer to whom the certificate is issued , corresponding with the said list and registry in all particulars. In case any Chinese laborer after having received such certificate shall leave such vessel before her departure he shall deliver his certificate to the master of the vessel, and if such Chinese laborer shall fail to return to such vessel before her departure from port the certificate shall be delivered by the master to the collector of customs for cancellation. The certificate herein provided for shall entitle the Chinese laborer to whom the same is issued to return to and re-enter the United States upon producing and delivering the same to the collector of customs of the district at which such Chinese laborer shall seek to re-enter; and upon delivery of such certificate by such Chinese laborer to the collector of customs at the time of re-entry in the United States said collector shall cause the same to be filed in the custom-house anti duly canceled.

SEC. 5. That any Chinese laborer mentioned in section four of this act being in the United States, and desiring to depart from the United States by land, shall have the right to demand and receive, free of charge or cost, a certificate of identification similar to that provided for in section four of this act to be issued to such Chinese laborers as may desire to leave the United States by water; and it is hereby made the duty of the collector of customs of the district next adjoining the foreign country to which said Chinese laborer desires to go to issue such certificate, free of charge or cost, upon application by such Chinese laborer, and to enter the same upon registry-books to be kept by him for the purpose, as provided for in section four of this act.

SEC. 6. That in order to the faithful execution of articles one and two of the treaty in this act before mentioned, every Chinese person other than a laborer who may be entitled by said treaty and this act to come within the United States, and who shall be about to come to the United States, shall be identified as so entitled by the Chinese Government in each case , such identity to be evidenced by a certificate issued under the authority of said government, which certificate shall be in the English language or (if not in the English language) accompanied by a translation into English, stating such right to come, and which certificate shall state the name, title or official rank, if any, the age, height, and all physical peculiarities, former and present occupation or profession, and place of residence in China of the person to whom the certificate is issued and that such person is entitled, conformably to the treaty in this act mentioned to come within the United States. Such certificate shall be prima-facie evidence of the fact set forth therein, and shall be produced to the collector of customs, or his deputy, of the port in the district in the United States at which the person named therein shall arrive.

SEC. 7. That any person who shall knowingly and falsely alter or substitute any name for the name written in such certificate or forge any such certificate, or knowingly utter any forged or fraudulent certificate, or falsely personate any person named in any such certificate, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor ; and upon conviction thereof shall be fined in a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisoned in a penitentiary for a term of not more than five years.

SEC. 8. That the master of any vessel arriving in the United States from any foreign port or place shall, at the same time he delivers a manifest of the cargo, and if there be no cargo, then at the time of making a report of the entry of the vessel pursuant to law, in addition to the other matter required to be reported, and before landing, or permitting to land, any Chinese passengers, deliver and report to the collector of customs of the district in which such vessels shall have arrived a separate list of all Chinese passengers taken on board his vessel at any foreign port or place, and all such passengers on board the vessel at that time. Such list shall show the names of such passengers (and if accredited officers of the Chinese Government traveling on the business of that government, or their servants, with a note of such facts), and the names and other particulars, as shown by their respective certificates; and such list shall be sworn to by the master in the manner required by law in relation to the manifest of the cargo. Any willful refusal or neglect of any such master to comply with the provisions of this section shall incur the same penalties and forfeiture as are provided for a refusal or neglect to report and deliver a manifest of the cargo.

SEC. 9. That before any Chinese passengers are landed from any such line vessel, the collector, or his deputy, shall proceed to examine such passenger, comparing the certificate with the list and with the passengers ; and no passenger shall be allowed to land in the United States from such vessel in violation of law.

SEC.10. That every vessel whose master shall knowingly violate any of the provisions of this act shall be deemed forfeited to the United States, and shall be liable to seizure and condemnation in any district of the United States into which such vessel may enter or in which she may be found.

SEC. 11. That any person who shall knowingly bring into or cause to be brought into the United States by land, or who shall knowingly aid or abet the same, or aid or abet the landing in the United States from any vessel of any Chinese person not lawfully entitled to enter the United States, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall, on conviction thereof, be fined in a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisoned for a term not exceeding one year.

SEC. 12. That no Chinese person shall be permitted to enter the United States by land without producing to the proper officer of customs the certificate in this act required of Chinese persons seeking to land from a vessel. And any Chinese person found unlawfully within the United States shall be caused to be removed therefrom to the country from whence he came , by direction of the President of the United States, and at the cost of the United States, after being brought before some justice, judge, or commissioner of a court of the United States and found to be one not lawfully entitled to be or remain in the United States.

SEC. 13. That this act shall not apply to diplomatic and other officers of the Chinese Government traveling upon the business of that government, whose credentials shall be taken as equivalent to the certificate in this act mentioned, and shall exempt them and their body and household servants from the provisions of this act as to other Chinese persons.

SEC. 14. That hereafter no State court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship; and all laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.

SEC.15. That the words “Chinese laborers”, wherever used in this act shall be construed to mean both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.

Approved, May 6, 1882 .

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

More Stories

- Power over Presidential Records

- A Utopia—for Some—in India

- Islands in the Cash Stream

Wooden Kings and Winds of Change in Tonga

Recent posts.

- Ice, Art, and a Living Earth

- In the Mood for “Fake” Music?

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Causes and effects

What is the Chinese Exclusion Act?

How did the chinese exclusion act affect chinese immigrants who were already in the united states, why was the chinese exclusion act repealed, how did the chinese exclusion act affect america.

Chinese Exclusion Act

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Archives - Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

- The Canadian Encyclopedia - Chinese Immigration Act

- Office of the Historian - Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 1943

- Yale Law School - Lillian Goldman Law Library - The Avalon Project - Chinese Exclusion Act; May 6, 1882

- GlobalSecurity.org - Chinese Exclusion Act

- CNN - On this day 141 years ago, a new law began reshaping America. More than a century later, Congress apologized for it

- Bill of Rights Institute - The Chinese Exclusion Act

- Densho Encyclopedia - Chinese Exclusion Act

- Chinese Exclusion Act - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The Chinese Exclusion Act (formally Immigration Act of 1882) was a U.S. federal law that was the first and only major federal legislation to explicitly suspend immigration for a specific nationality. The basic exclusion law prohibited Chinese labourers—defined as “both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining”—from entering the United States . The passage of the act represented the outcome of years of racial hostility and anti-immigrant agitation by white Americans.

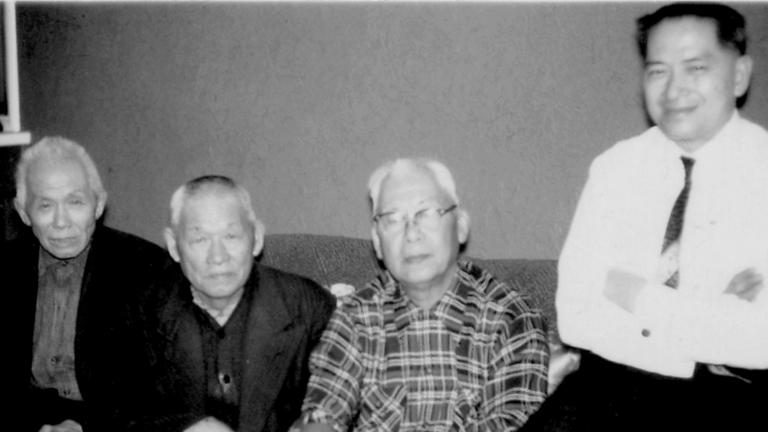

Chinese communities in the United States underwent dramatic change because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Families were forced apart, and businesses were closed down. Because of the severe restrictions on female immigrants and the pattern of young men migrating alone, a largely bachelor society emerged. Under the continuing anti-Chinese pressure, Chinatowns were established in urban cities where the Chinese could retreat into their own cultural and social colonies.

When did the Chinese Exclusion Act end?

The Chinese Exclusion Act ended in 1943 when it was repealed with the passage of the Magnuson Act, which permitted an annual quota of 105 Chinese immigrants.

Various factors contributed to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, such as the calming of the anti-Chinese sentiment of previous decades, the establishment of quota systems for immigrants of other nationalities who had rapidly increased in the United States, and the political consideration that the United States and China were allies in World War II .

The Chinese Exclusion Act significantly decreased the number of Chinese immigrants in the United States : according to the U.S. national census, there were 105,465 in 1880, compared with 89,863 by 1900 and 61,639 by 1920. It signaled the shift from a previously open immigration policy to one where criteria were set regarding who—in terms of ethnicity, gender, and class—could be admitted. Immigration patterns, immigration communities, and racial identities and categories were significantly affected.

Chinese Exclusion Act , U.S. federal law that was the first and only major federal legislation to explicitly suspend immigration for a specific nationality. The basic exclusion law prohibited Chinese labourers—defined as “both skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining”—from entering the country. Subsequent amendments to the law prevented Chinese labourers who had left the United States from returning. The passage of the act represented the outcome of years of racial hostility and anti-immigrant agitation by white Americans, set the precedent for later restrictions against immigration of other nationalities, and started a new era in which the United States changed from a country that welcomed almost all immigrants to a gatekeeping one.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed by Congress and signed by Pres. Chester A. Arthur in 1882. It lasted for 10 years and was extended for another 10 years by the 1892 Geary Act, which also required that people of Chinese origin carry identification certificates or face deportation . Later measures placed a number of other restrictions on the Chinese, such as limiting their access to bail bonds and allowing entry to only those who were teachers, students, diplomats, and tourists. Congress closed the gate to Chinese immigrants almost entirely by extending the Chinese Exclusion Act for another 10 years in 1902 and making the extension indefinite in 1904.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943 with the passage of the Magnuson Act, which permitted a quota of 105 Chinese immigrants annually. Various factors contributed to the repeal, such as the quieted anti-Chinese sentiment , the establishment of quota systems for immigrants of other nationalities who had rapidly increased in the United States, and the political consideration that the United States and China were allies in World War II .

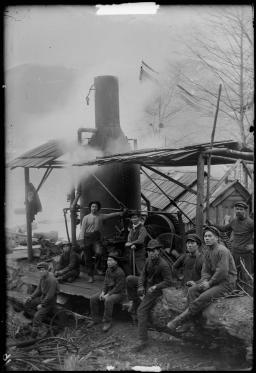

Many scholars explain the institution of the Chinese Exclusion Act and similar laws as a product of the widespread anti-Chinese movement in California in the second half of the 19th century. The Chinese had constituted a significant minority on the West Coast since the middle of the 19th century. Initially, they laboured in gold mines, where they showed a facility for finding gold. As a result, they encountered hostility and were gradually forced to leave the field and move to urban areas such as San Francisco , where they were often confined to performing some of the dirtiest and hardest work. Americans in the West persisted in their stereotyping of the Chinese as degraded, exotic, dangerous, and competitors for jobs and wages. Sen. John F. Miller of California, a proponent of the Chinese Exclusion Act, argued that the Chinese workers were “machine-like…of obtuse nerve, but little affected by heat or cold, wiry, sinewy, with muscles of iron.” Partly in response to that stereotype , organized labour in the West made restricting the influx of Chinese into the United States one of its goals. In other words, the exclusion was the result of a grassroots anti-Chinese sentiment. Other scholars have argued that the exclusion should be blamed on top-down politics rather than a bottom-up movement, explaining that national politicians manipulated white workers to gain an electoral advantage. Still others have adopted a “national racism thesis” that focuses on endemic anti-Chinese racism in early American national culture .

The exclusion laws had dramatic impacts on Chinese immigrants and communities . They significantly decreased the number of Chinese immigrants into the United States and forbade those who left to return. According to the U.S. national census in 1880, there were 105,465 Chinese in the United States, compared with 89,863 by 1900 and 61,639 by 1920. Chinese immigrants were placed under a tremendous amount of government scrutiny and were often denied entry into the country on any possible grounds. In 1910 the Angel Island Immigration Station was established in San Francisco Bay . Upon arrival there a Chinese immigrant could be detained for weeks to years before being granted or denied entry. Chinese communities underwent dramatic changes as well. Families were forced apart, and businesses were closed down. Because of the severe restrictions on female immigrants and the pattern of young men migrating alone, there emerged a largely bachelor society. Under the continuing anti-Chinese pressure, Chinatowns were established in urban cities, where the Chinese could retreat into their own cultural and social colonies.

The excluded Chinese did not passively accept unfair treatment but rather used all types of tools to challenge or circumvent the laws. One such tool was the American judicial system . Despite having come from a country without a litigious tradition, Chinese immigrants learned quickly to use courts as a venue to fight for their rights and won many cases in which ordinances aimed against the Chinese were declared unconstitutional by either the state or federal courts. They were aided in their legal battles by Frederick Bee , a California entrepreneur and attorney who was one of the principal American advocates of the civil rights of Chinese immigrants and who represented many of them in court from 1882 to 1892. They also protested against racial discrimination through other venues , such as the media and petitions.

Some Chinese simply evaded the laws altogether by immigrating illegally. In fact, the phenomenon of illegal immigration became one of the most significant legacies of the Chinese-exclusion era in the United States. Despite the disproportionate time and resources spent by U.S. immigration officials to control Chinese immigration, many Chinese migrated across the borders from Canada and Mexico or used fraudulent identities to enter the country. A common strategy was that of the so-called “ paper son ” system, in which young Chinese males attempted to enter the United States with purchased identity papers for fictional sons of U.S. citizens (people of Chinese descent who had falsely established the identities of those “sons”). Thus, Chinese exclusion was not only an institution that produced and reinforced a system of racial hierarchy in immigration law, but it was also a process that both immigration officials and immigrants shaped and a realm of power dominance, struggle, and resistance.

The impact of the exclusion laws went beyond restricting, marginalizing , and, ironically, activating the Chinese. It signaled the shift from a previously open immigration policy in the United States to one in which the federal government exerted control over immigrants. Criteria were gradually set regarding which people—in terms of their ethnicity , gender, and class—could be admitted. Immigration patterns, immigration communities, and racial identities and categories were significantly affected. The very definition of what it meant to be an American became more exclusionary. Meanwhile, Chinese-exclusion practices shaped immigration law during that time period. Believing that courts gave too much advantage to the immigrants, the government succeeded in cutting off Chinese access to the courts and gradually transferred administration of Chinese-exclusion laws completely to the Bureau of Immigration, an agency operating free from court scrutiny. By 1910 the enforcement of the exclusion laws had become centralized, systematic, and bureaucratic .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Chinese Exclusion Act

By: History.com Staff

Updated: August 9, 2022 | Original: August 24, 2018

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first significant law restricting immigration into the United States. Many Americans on the West Coast attributed declining wages and economic ills to Chinese workers. Although the Chinese composed only 0.002 percent of the nation's population, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act to placate worker demands and assuage concerns about maintaining white "racial purity."

Chinese Immigration in America

The Opium Wars (1839-42, 1856-60) of the mid-nineteenth century between Great Britain and China left China heavily in debt. Additionally, floods and drought contributed to an exodus of peasants from their farms, and many left the country to find work. When gold was discovered in the Sacramento Valley of California in 1848, a large uptick in Chinese immigrants entered the United States to join the California Gold Rush .

Following an 1852 crop failure in China, over 20,000 Chinese immigrants came through the custom house in San Francisco (up from 2,716 the previous year) looking for work. Violence soon broke out between white miners and the new arrivals, much of it racially charged. In May 1852, California imposed a Foreign Miners License Tax of $3 month meant to target Chinese miners, and crime and violence escalated.

An 1854 California Supreme Court case, People v. Hall , ruled that the Chinese, like Black Americans and Native Americans , were not allowed to testify in court, making it effectively impossible for Chinese immigrants to seek justice against the mounting violence. By 1870, Chinese miners had paid $5 million to the state of California via the Foreign Miners License Tax, yet they faced continuing discrimination at work and in their camps.

Purpose of the Chinese Exclusion Act

Meant to curb the influx of Chinese immigrants to the United States—particularly California—the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 suspended Chinese immigration for ten years and declared Chinese immigrants ineligible for naturalization.

President Chester A. Arthur signed it into law on May 6, 1882. Chinese-Americans already in the country challenged the constitutionality of the discriminatory acts, but their efforts failed.

Geary Act of 1892

Proposed by California congressman Thomas J. Geary , the Geary Act went into effect on May 5, 1892. It reinforced and extended the Chinese Exclusion Act’s ban on Chinese immigration for an additional ten years. It also required Chinese residents in the United States to carry special documentation—certificates of residence—from the Internal Revenue Service .

Immigrants who were caught not carrying the certificates were sentenced to hard labor and deportation, and bail was only an option if the accused were vouched for by a “credible white witness.”

China’s government protested these discriminatory laws, but with anti-immigrant sentiment at fever pitch in the United States, there was little they could do. Chinese Americans were finally allowed to testify in court after the 1882 trial of laborer Yee Shun , though it would take decades for the immigration ban to be lifted.

Impact of Chinese Exclusion Act

The Supreme Court upheld the Geary Act in Fong Yue Ting v. United States in 1893, and in 1902 Chinese immigration was made permanently illegal. The legislation proved very effective, and the Chinese population in the United States sharply declined.

American experience with Chinese exclusion spurred later movements for immigration restriction against other "undesirable" groups such as Middle Easterners, Hindu and East Indians and the Japanese with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 .

Chinese immigrants and their American-born families remained ineligible for citizenship until 1943 with the passage of the Magnuson Act . By then, the U.S. was embroiled in World War II and sought to improve relations with an important Asian ally.

READ MORE: Before the Chinese Exclusion Act, This Anti-Immigrant Law Targeted Asian Women

Chinese Immigrants and the Gold Rush. PBS . Chinese Immigration and the Chinese Exclusion Acts. The State Department .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Learning Resources

The chinese exclusion act:, read for understanding.

In 2020 the United Nations reported a rise in Anti-Asian racism and Xenophobia during the COVID-19 flu pandemic. As you explore these learning resources, you will learn more about the role Chinese Americans have played in shaping our nation's past, and the ways in which American policies and discrimination have limited immigrants past and present.

Key Vocabulary

How have u.s. policies limited asian-american citizenship, statue of liberty.

commons.wikimedia.org

- Look for patterns in your list. What do some or all of your words have in common?

- What does your list tell you about how you view the Statue of Liberty?

A Chinese Immigrant Reacts to the Statue of Liberty

This letter, originally published in the New York Sun in 1885, was written by Saum Song Bo in response to a fund-raising campaign for the building of a pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. Three years earlier, Congress had passed the Chinese Exclusion Act.

shec.ashp.cuny.edu

A CHINESE IMMIGRANT’S VIEW -- Read this letter written in 1885 by a Chinese immigrant to a New York newspaper, three years after Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This act suspended Chinese immigration to the U.S. for 10 years and denied Chinese immigrants the right to become naturalized citizens . As you read, your teacher may provide you a copy of this “4 C’s” graphic organizer , adding at least 1 idea for each category.

"The 4 C's" Organizer

docs.google.com

- What shaped Chinese immigrant Saum Song Bo’s view of the Statue of Liberty and of being an American citizen?

- How does this example show how a U.S. policy limited Asian-American citizenship?

- How did Americans try to purge Chinese-Americans from the U.S.?

American Panorama - Foreign Born

dsl.richmond.edu

Examine Chinese immigration in the 1800s by making a copy and completing this Data Organizer .

NAH Data Organizer for "Foreign-Born Population" map

- From 1850 to 1900, how would you describe the changes in the Chinese-born population in the U.S.?

- Click on the 1880 vertical line in the “Population over Time” timeline. In your own words, summarize the story box in the lower right-hand corner.

- How did the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 affect the number of Chinese-born people in the 30 years after the act was passed?

- Conduct online research to answer these questions, based on the data: What accounts for the changes in the Chinese-born population from 1850 to 1900? (What was going on in China from 1850 to 1900? What was going on in the U.S.?)

Here are some suggestions for trustworthy sites: PBS: The Story of China , BBC China Timeline , Library of Congress Timeline of U.S. History

Home | Story of China | PBS

www.pbs.org

China profile - Timeline

A chronology of key events in the history of China

www.bbc.com

Printable Timeline | 1850 to 1899 | Timeline | Articles and Essays | Library of Congress

www.loc.gov

A STORY OF GOLD, JOBS, AND RACISM: Many Chinese immigrants escaped instability in China and moved to the western U.S. in the 1800s in search of gold, factory jobs, or work building the American rail system. Read this Bunk article excerpt called “The Forgotten History of the Campaign to Purge Chinese from America” .

The Forgotten History of the Campaign to Purge Chinese from America

The surge in violence against Asian-Americans is a reminder that America’s present reality reflects its exclusionary past.

www.bunkhistory.org

After you read, complete a separate “4 C’s” organizer and share your ideas from each column of the chart in your small groups.

- How does the data you examined fit into the story of Asian-Americans in the U.S.?

What prompted the Chinese Exclusion Act, and what have been its lasting consequences?

In the shadow of chinese exclusion — backstory archive.

Imagine living in a country without the ability to become a citizen. Meanwhile, you endure discrimination and outright hostility on a daily basis because of your ethnicity. This was the struggle of Chinese people living in the U.S. for decades. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred immigration for Chinese laborers and declared the Chinese ineligible for citizenship.

backstory.newamericanhistory.org

- What is the most important point?

- What are you finding challenging, puzzling or difficult to understand?

- What question would you most like to discuss?

- What is something you found interesting?

NAH "Take Note" Listening Guide - Chinese Exclusion Act

BEFORE EXCLUSION BECAME LAW: Laws can sometimes be the product of a place’s developed norms or attitudes. How did the attitudes and actions toward Chinese-Americans in California and the American West in the mid-1800s lead to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882?

The California Klan’s Anti-Asian Crusade

Whereas southern Klansmen assaulted Black Americans and their white allies, western vigilantes targeted those they deemed a greater threat: Chinese immigrants.

The Bloody History of Anti-Asian Violence in the West

One of the largest mass lynchings in the United States targeted Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles.

- What were the attitudes and events that led to the Chinese Exclusion Act, and what has been the lasting legacy of the Act?

How could we compare and contrast the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the history of Jim Crow laws in America?

Racism has always been part of the asian american experience.

If we don’t understand the history of Asian exclusion, we cannot understand the racist hatred of the present.

Read the Bunk excerpt, “ Racism Has Always Been Part of the Asian American Experience ”. Make a copy, or your teacher will provide you a copy of this Reading Guide that contains a Summary Sentence and the 4 C’s thinking routine .

NAH Reading Guide - Summary & "The 4 C's"

After you complete the Reading Guide, answer this question: Compare the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the history of Jim Crow laws. To do that, complete the Comparison Research Guide to organize your findings. Use the Bank of Sources on the guide to build your answer.

NAH Comparison Research Guide

STEP #1 Use the Bank of Sources below to answer this question: Compare the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act and the history of Jim Crow laws. Skim through the sources. Use their information to complete the chart below. BANK OF SOURCES Guo, Jeff. “The Real Reasons the U.S. Became Less Rac...

Your teacher may ask you to record your answers on an exit ticket.

What can Americans today learn from the Chinese Exclusion Act?

Nah reflection guide.

Rewiring American History

- Why do you think the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act matters today?

- What lessons should we Americans draw from it?

“A Chinese Immigrant Reacts to the Statue of Liberty · SHEC: Resources for Teachers.” Social History for Every Classroom. American Social History Productions, Inc. - City University of New York. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/950 .

Luo, Michael. “The Forgotten History of the Campaign to Purge Chinese from America.” The New Yorker. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/the-forgotten-history-of-the-purging-of-chinese-from-america .

Nelson, R. K., Nesbit, S., Ayers, E. L., Madron, J., & Ayers, N. (n.d.). “Foreign Born” in American Panorama, ed. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/foreignborn/#decade=2010 .

“Project Zero's Thinking Routine Toolbox.” PZ's Thinking Routines Toolbox | Project Zero, www.pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines .

“To Be a Citizen?” BackStory. Virginia Humanities. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.backstoryradio.org/shows/to-be-a-citizen/#segment-in-the-shadow-of-chinese-exclusion .

Waite, Kevin. “The Forgotten History of the Western Klan.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, April 6, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/04/california-klans-anti-asian-crusade/618513/ .

Waite, Kevin. “The Bloody History of Anti-Asian Violence in the West.” History & Culture - Race in America. National Geographic, May 10, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/the-bloody-history-of-anti-asian-violence-in-the-west .

This work by New American History is licensed under a Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) International License . Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at newamericanhistory.org.

Comments? Questions?

Let us know what you think about this Learning Resource. We’d also love to hear other ideas or answer questions from you!

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Chan, Arlene. "Chinese Immigration Act". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 30 May 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act. Accessed 25 June 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 30 May 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act. Accessed 25 June 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Chan, A. (2023). Chinese Immigration Act. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Chan, Arlene. "Chinese Immigration Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published March 07, 2017; Last Edited May 30, 2023.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published March 07, 2017; Last Edited May 30, 2023." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Chinese Immigration Act," by Arlene Chan, Accessed June 25, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Chinese Immigration Act," by Arlene Chan, Accessed June 25, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/chinese-immigration-act" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Chinese Immigration Act

Article by Arlene Chan

Updated by Clayton Ma

Published Online March 7, 2017

Last Edited May 30, 2023

The anti-Chinese movement took root after the first wave of Chinese immigrants began arriving in British Columbia for the gold rush of 1858. The second major Chinese influx to the province came as labourers for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (1881–85), a labour force much needed for the development of Western Canada but not desirable as citizens for a “White Canada forever.” This popular phrase among politicians and the media was derived from the White Canada policy laid down in the Immigration Act of 1910. While the act did not name any racial or ethnic groups, it did allow for the restriction of “immigrants belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada,” the ethnic basis for Canadian immigration policy until 1967 ( see Prejudice and Discrimination ).

After the completion of the CPR, agitation against the “yellow peril” gathered momentum, resulting in over 100 provincial laws and policies that restricted the rights of Chinese residents. (The “yellow peril” reference to Chinese and Japanese people originated in the late 1800s after they arrived as labourers in the United States and Canada; it expressed Western prejudice towards East Asian immigrants.) The Canadian government’s most racist and exclusionary law, however, was the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885. Under that law, a $50 head tax was levied on all Chinese immigrants. The head tax was increased to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903. It became clear that this punitive entry fee did not discourage Chinese immigration , as intended. The Chinese population tripled during the head-tax era, from 13,000 in 1885 to 39,587 in 1921. A harsher solution was required: exclusion.

On 1 July 1923, Dominion Day, now called Canada Day , the Chinese Immigration Act , a new law with the same name, was passed. The Chinese in Canada referred to this day as “Humiliation Day” and refused to join in its celebrations for many years.

Community Life

From the government’s point of view, the Chinese Immigration Act was an overwhelming success. During the exclusionary period, fewer than 50 Chinese immigrants were allowed entry. The population decreased by 25 per cent, from 39,587 in 1921 to 32,528 by 1951. Not only did the law ban Chinese immigration , it also intentionally disrupted family life and stunted community growth.

In 1941 there were 29,033 Chinese men in Canada, over 80 per cent of whom were married with wives and children left behind in China. Enduring this family separation, these “married bachelors” lived alone. A mere handful had the financial means to make a trip to China a few times during the exclusionary years to either marry or visit their wives and children. Whether or not they were Canadian-born or naturalized, they were not allowed to sponsor family members to join them in Canada.

With the absence of family life, the Chinese community found support through their traditional associations, not only for socialization and relaxation, but also for financial aid, banking services, social services and employment and housing assistance. These organizations, some of the membership of which was based on shared surnames, some on common place of origin, provided a haven for the bachelor society.

Political associations, on the other hand, were competitive in signing up members, regardless of surnames and place of birth. Differences in political ideologies resulted in conflicting views about events unfolding in China. There were rare instances, however, that brought disparate groups together. The passing of the Chinese Immigration Act was one such occasion. A national federation of Chinese organizations was one of many that exhausted all legal and political avenues to repeal the Act, which they named the “forty-three harsh regulations.”

Economic Life

At the onset of the Chinese Immigration Act , prejudice and discrimination were already well entrenched. Chinese people were reduced to second-class status as an inferior race ( see Racism ). Legislation barred them from the right to vote , to hold public office or to own property, limited employment and housing and imposed many other restrictions. Protests from White workers and labour unions hampered their ability to earn a living. Still burdened by paying off debts incurred by the head tax , they also earned lower wages. Bearing such harsh conditions, Chinese people retreated into small businesses such as laundries, restaurants and grocery stores. Employment as cooks and servants, domestic work that was undesirable to White workers due to the low pay and social status, was also willingly endured rather than the alternative of returning to China and sacrificing the earnings that supported their families there.

The urgency to earn money for families in China was so great that desperate times called for desperate solutions. An illegal immigration scheme gathered momentum from the head-tax era, one that arranged for people, mostly males, to come to Canada with fraudulent papers claiming false identities. These “paper sons” adopted new surnames, then came under the identity of someone who was entitled to return to Canada but did not. The price was high, not only for the cost of the fake identity, but also the subsequent years of living in fear of being deported back to China and keeping secret their real names, even from their descendants.

The Great Depression (1929–39) added an additional layer of hardship. The Chinese unemployment rate soared as high as 80 per cent in Vancouver , a sharp contrast to the city’s overall jobless rate of 30.2 per cent in 1931. Loss of face was a deeply entrenched cultural value and a hindrance to seeking help outside of their community. Although most Chinese people turned to their traditional associations for financial assistance, those who had to rely on the government received less money than expected. Relief payments of $1.12 per week to Chinese people in Alberta , as an example, were less than half of what was given to other Albertans.

The War Years, 1937–45

News from China did not bring any comfort during the exclusionary years. Civil wars pitted the ruling Nationalist Party ( Guomindang ) against military warlords and rising Communist forces. Beyond these internal conflicts were external threats from Japan, starting with small-scale incidents that escalated to the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and the occupation of China. The flow of letters and remittances (money sent home) was interrupted, particularly after the Japanese captured Hong Kong , a major communication hub between China and North America. The safety and well-being of family members in China was unknown.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 marked a turning point in Chinese Canadian history. The war provided an opportunity to volunteer for service, ultimately to prove one’s loyalty and patriotism and gain the right to vote . The issue, however, polarized the Chinese community into two factions: “Serve first, demand rights after” versus “No vote, no fight.”

The declaration of war against Japan in 1941 was another tipping point. Canada and China were now allied, fighting together against a common enemy. The military policy of barring Chinese recruits was reversed in 1944 in an amendment to the National Resources Mobilization Act of 1940. An estimated 600 Chinese people, including several women, enlisted in all three branches of the Canadian Armed Forces .

The war’s end in 1945 brought lessening hostility, favourable media coverage and growing esteem for the Chinese community’s war effort in military service, fundraising and Victory Loan drives. Politicians, labour unions and war veterans joined church leaders in demanding the Canadian government repeal its anti-Chinese legislation. An additional pressure point in 1945 was the United Nations ’ Charter of Human Rights and subsequent Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Canada, as a signatory country, contravened these new universal rights with its anti-Chinese policies.

In 1947, Canada repealed the Chinese Immigration Act . As much as the language of exclusion was removed, Chinese immigrants were still treated inequitably due to Order-in-Council , P.C. 2115. This order stipulated that entrance was limited to only spouses and children (under the age of 18) of Canadian citizens at a time when only 8 per cent of Chinese-born residents were naturalized citizens. For other immigrants, there were no such restrictions. Delegations of Chinese and non-Chinese individuals made annual visits to Ottawa to lobby for an immigration policy that would ease family reunification. Men in the bachelor society who dreamed of bringing their families to Canada were largely disappointed for another 20 years.

In 1967, immigration restrictions on the basis of race and national origin were finally removed. Chinese immigrants could now apply for entry on equal footing with other applicants.

Apology and Redress

Nationwide campaigns lobbied the federal government for over 20 years to apologize for the injustices of its past anti-Chinese immigration policies . On 22 June 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper formally apologized for the head tax (1885–1923) and exclusionary legislation (1923–47). Symbolic payments were made to surviving head-tax payers and to the spouses of deceased payers. A community fund was designated for projects to commemorate and educate Canadians about the past injustices endured by the Chinese Canadian community. An apology by Christy Clark , premier of British Columbia , followed on 15 May 2014, and a $1 million legacy fund was promised for educational initiatives.

In 2023, the federal government recognized the exclusion of Chinese immigrants from Canada from 1923 to 1947 as an event of historical significance.

Significance

The Chinese Immigration Act successfully halted the influx of Chinese immigrants into Canada and severely restricted economic, social and community development for 24 years. After the Second World War , the repeal of this discriminatory legislation, the gaining of the right to vote and the establishment of the Canadian Citizenship Act in 1947 were the first steps to increased and more equitable inclusion into Canadian life. The Chinese in Canada could now assume their rightful place as valued Canadian citizens .

- immigration

- Chinese Canadians

- racial discrimination

Further Reading

Peter Li, The Chinese in Canada (1998)

Lisa Mar, Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada’s Exclusion Era, 1885-1945 (2010)

Anthony B. Chan, Gold Mountain: The Chinese in the New World (1983)

Harry Con, Ronald J. Con, Graham Johnson, Edgar Wickberg and William E. Willmott, From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada (1982)

External Links

Exclusion of Chinese Immigrants (1923-1947) National Historic Event

Recommended

Chinese head tax in canada, internment of japanese canadians, child migration to canada.

Make a gift to PBS News Hour and your donation will be doubled !

Support Intelligent, In-Depth, Trustworthy Journalism.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Adrian De Leon, The Conversation Adrian De Leon, The Conversation

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/the-long-history-of-racism-against-asian-americans-in-the-u-s

The long history of racism against Asian Americans in the U.S.

In a recent Washington Post op-ed , former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang called upon Asian Americans to become part of the solution against COVID-19.

In the face of rising anti-Asian racist actions – now at about 100 reported cases per day – Yang implores Asian Americans to “wear red, white, and blue” in their efforts to combat the virus.

Optimistically, before Donald Trump declared COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” Yang believed that “getting the virus under control” would rid this country of its anti-Asian racism. But Asian American history, my field of research , suggests a sobering reality.

A history of anti-Asian racism

Up until the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, the prevailing narrative about Asian Americans was one of the model minority.

The model minority concept, developed during and after World War II, posits that Asian Americans were the ideal immigrants of color to the United States due to their economic success.

But in the United States, Asian Americans have long been considered as a threat to a nation that promoted a whites-only immigration policy. They were called a “yellow peril”: unclean and unfit for citizenship in America .

In the late 19th century, white nativists spread xenophobic propaganda about Chinese uncleanliness in San Francisco. This fueled the passage of the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act , the first law in the United States that barred immigration solely based on race. Initially, the act placed a 10-year moratorium on all Chinese migration.

In the early 20th century, American officials in the Philippines, then a formal colony of the U.S., denigrated Filipinos for their supposedly unclean and uncivilized bodies . Colonial officers and doctors identified two enemies: Filipino insurgents against American rule, and “tropical diseases” festering in native bodies. By pointing to Filipinos’ political and medical unruliness, these officials justified continued U.S. colonial rule in the islands.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 to incarcerate people under suspicion as enemies to inland internment camps.

While the order also affected German- and Italian-Americans on the East Coast, the vast majority of those incarcerated in 1942 were of Japanese descent. Many of them were naturalized citizens, second- and third-generation Americans. Internees who fought in the celebrated 442nd Regiment were coerced by the United States military to prove their loyalty to a country that locked them up simply for being Japanese.

In the 21st century, even the most “multicultural” North American cities, like my hometown of Toronto, Canada, are hotbeds for virulent racism. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, Toronto saw a rise of anti-Asian racism , much like that of today.

In her 2008 study, sociologist Carrianne Leung highlights the everyday racism against Chinese and Filipina health care workers in the years that followed the SARS crisis. While publicly celebrated for their work in hospitals and other health facilities, these women found themselves fearing for their lives on their way home.

No expression of patriotism – not even being front-line workers in a pandemic – makes Asian migrants immune to racism .

Making the model minority

Over the past decade, from Pulitzer Prizes to popular films , Asian Americans have slowly been gaining better representation in Hollywood and other cultural industries.

Whereas “The Joy Luck Club” had long been the most infamous depiction of Asian-ness in Hollywood, by the 2018 Golden Globes, Sandra Oh declared her now famous adage: “It’s an honor just to be Asian.” It was, at least at face value, a moment of cultural inclusion.

However, so-called Asian American inclusion has a dark side.

In reality, as cultural historian Robert G. Lee has argued , inclusion can and has been used to undermine the activism of African Americans, indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups in the United States. In the words of writer Frank Chin in 1974, “Whites love us because we’re not black.”

For example, in 1943, a year after the United States incarcerated Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act. White liberals advocated for the repeal not out of altruism toward Chinese migrants, but to advocate for a transpacific alliance against Japan and the Axis powers .

By allowing for the free passage of Chinese migrants to the United States, the nation could show its supposed fitness as an interracial superpower that rivaled Japan and Germany. Meanwhile, incarcerated Japanese Americans in camps and African Americans were still held under Jim Crow segregation laws.

In her new book, “ Opening the Gates to Asia: A Transpacific History of How America Repealed Asian Exclusion ,” Occidental College historian Jane Hong reveals how the United States government used Asian immigration inclusion against other minority groups at a time of social upheaval.

For example, in 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration signed the much-celebrated Hart-Celler Act into law. The act primarily targeted Asian and African migrants, shifting immigration from an exclusionary quota system to an merit-based points system. However, it also imposed immigration restrictions on Latin America.

Beyond model minority politics

As history shows, Asian American communities stand to gain more working within communities and across the lines of race, rather than trying to appeal to those in power.

Japanese American activists such as the late Yuri Kochiyama worked in solidarity with other communities of color to advance the civil rights movement.

A former internee at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas, Kochiyama’s postwar life in Harlem, and her friendship with Malcolm X, inspired her to become active in the anti-Vietnam War and civil rights movements. In the 1980s, she and her husband Bill, himself part of the 442nd Regiment, worked at the forefront of the reparations and apology movement for Japanese internees. As a result of their efforts, Ronald Reagan signed the resulting Civil Liberties Act into law in 1988 .

Kochiyama and activists like her have inspired the cross-community work of Asian American communities after them.

In Los Angeles, where I live, the Little Tokyo Service Center is among those at the forefront of grassroots organizing for affordable housing and social services in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood . While the organization’s priority area is Little Tokyo and its community members, the center’s work advocates for affordable housing among black and Latinx residents, as well as Japanese American and other Asian American groups.

To the northwest in Koreatown, the grassroots organization Ktown for All conducts outreach to unhoused residents of the neighborhood, regardless of ethnic background.

The coronavirus sees no borders. Likewise, I think that everyone must follow the example of these organizations and activists, past and present, to reach across borders and contribute to collective well-being.

Self-isolation, social distancing and healthy practices should not be in the service of proving one’s patriotism. Instead, these precautions should be done for the sake of caring for those whom we do and do not know, inside and outside our national communities.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Adrian De Leon is an assistant professor of American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California – Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Support PBS News:

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Unit 4 Immigration, Migration, Refugees

Chapter 4 chinese immigration, educator tools.

Ask yourself:

- Why did the federal government discriminate against a single ethnic group?

- What debt, if any, do Canadians owe to those who were victims of injustice in the past?

- Is exclusion ever fair? Why would one group exclude another?

Dr. Joseph Wong talks about the Chinese Head Tax

On this page you will have the opportunity to consider the concept of exclusion and by examining a timeline you will learn about the prejudice and discrimination faced by Chinese immigrants beginning at the end of the nineteenth century. You will share your views of how the government could respond to demands to redress injustices such as the head tax.

This really happened

Between the years 1881 and 1885, almost 15,000 men were recruited from China to help build the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). As soon as the railroad was completed, the Chinese were considered an employment threat to Canadian workers, so the federal government moved to restrict Chinese immigration to Canada. Chinese immigration started in 1885 in response to the gold rush in British Columbia. The first federal anti-Chinese bill was passed in 1885, imposing a $50 head tax upon every person of Chinese origin entering the country. No other ethnic group was targeted this way.

By 1903, the head tax was increased to $500 and the government was able to collect $23 million from the Chinese through this policy. Meanwhile, Chinese immigrants continued to come to Canada. In 1923, Parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act (aka Chinese Exclusion Act ) excluding all but a few Chinese immigrants from entering Canada. When the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947, a number of activists campaigned against the federal government to seek redress for the head tax. Since 1993, the House of Commons attempted to make offers to repay the Chinese. Finally, in 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper made an apology for the policy and offered repayment to those Chinese citizens who were penalized with the head tax. There were only approximately 20 Chinese Canadians alive in 2006 who had paid the head tax.

It is interesting to note that the Chinese population in the past few decades has increased favourably. In recent years, Chinese top the list of immigrants moving to Canada.

| Events | |

|---|---|

| took the form of a head tax of $50 imposed, with few exceptions, upon every person of Chinese origin entering Canada. Captains of ships bringing Chinese immigrants to Canada had to collect the tax before departure. | |

| , better known as was passed excluding those of Chinese origin from entering Canada. The act was passed on July 1, known as Dominion Day by Canadians but called “Humiliation Day” by the Chinese. | |

Creating a Visual Timeline

Each of the events highlighted in the timeline would have been reported by journalists throughout the country. Choose one of the events and create an illustration that might have appeared on the front page of the newspaper. What headline would accompany the illustration? You may choose to present your drawing in the form of a political cartoon.

Once completed, the class can arrange visual images in sequential order by creating a display or PowerPoint presentation.

Reporting events

Imagine that you are a journalist reporting on the event. What information would you offer your readers about the Chinese immigration experience? How might your report include the 5 W’s of reporting? Who? What? Where? When and Why? How does this event tell part of the story of immigration? What point of view might you use to present your article?

Responding to the Story of Chinese Immigration

Working in groups of three, record your reactions about a topic or issue and consider the views of others. Share your responses with two others to discover whether their opinions are similar or different from your opinion.

› Questions to Consider

- How did you react to the story of Chinese immigration? What surprised you?

- What are your opinions about any form of exclusion?

- Why do you think a federal government would discriminate in such a way? Was there any sound reasoning to imposing a head tax on the Chinese?

- Do you think apologies and payments are enough to compensate for the treatment of the Chinese?

› Take a blank piece of paper and fold it twice, to make four rectangles. Number the spaces #1, #2, #3, #4.

| #1 | #2 |

| #3 | #3 |

- In #1, write your response to one of the questions to consider connected to the issue of Chinese immigration. You might share your gut reaction, give an opinion, raise questions, or make a connection.

- Exchange papers with another person in the group. Read the response that is written in #1. Then, write your response to it in space #2. What did the response in space #1 invite you to think about?

- Repeat the activity one more time. Read both responses on the sheet you receive, and write a response to both in #3.

- The sheet is returned to the person who wrote the first response. Read all three responses on your sheet, and then write a new response in #4.

- As a follow up, the group can discuss the topic of Chinese immigration. Groups can share responses in a whole class discussion.

A Personal Response to Exclusion

A. Complete the following statements:

- For me, the word exclusion means . . .

- A story I know about exclusion is . . .

- One way to make up for an exclusion is . . .

B. Work in groups to share your responses. The following questions can guide your discussion:

- Is being excluded ever fair?

- Why might someone (or a group) exclude others?

- What does the story of exclusion of Chinese Immigrants remind you of – both personally and globally?

How Should Government Respond to a Past Injustice?

Key concepts › redress.

1. a. A relief from distress

1. b. A means or possibility of seeking a remedy

2. Compensation for a wrong or loss: reparation

Source : Merriam-Webster

Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act: Addressing the Issue of Redressing

After the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947, a number of activists, including Wong Foon Sien, began campaigning the federal government to seek redress for the head tax. But it took almost 60 years until an apology was offered. Why did it take so long?

During the 1980s, over 4,000 head tax payers and their family members approached the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) to register their head tax certificates. A redress campaign unfolded that included meetings, increased media profiles, research, publications and presentations in many communities. Although Prime Minister Brian Mulroney made an offer of individual medallions, a museum wing and other measures, these offers were rejected outright by the Chinese Canadian groups. In 1993, Jean Chretien’s cabinet openly refused to provide an apology or redress. The CCNC persevered raising the issue wherever they could, including a submission to the United Nations Human Rights Commission. In 2001, an Ontario court declared that the Canadian government had no obligation to redress the head tax levied on Chinese immigrants.

It was not until 2003, when Paul Martin was appointed prime minister, that there was a sense of urgency since there were only a few dozen surviving Chinese head tax payers. The issue continued to be a hot topic that was brought forth by politicians during federal elections. As part of his conservative party platform, Stephen Harper promised to work with the Chinese community on redress, a promise that he kept when elected in 2006. He stated, “Chinese Canadians are making an extraordinary impact on the building of our country. They’ve also made a significant historical contribution despite many obstacles . . . The Chinese community deserves an apology for the head tax and appropriate acknowledgement and redress.”

June 22, 2006—House of Commons

Finally, in a speech to the House of Commons on June 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology for the head tax. In his speech, Harper said, “We feel compelled to right this historic wrong for the simple reason it is the decent thing to do . . . a characteristic to be found at the core of the Canadian soul.”

Harper’s government offered symbolic payments of $20,000 to living head tax payers as well as to living spouses of deceased payers. Only an estimated 20 Chinese Canadians who paid the tax were still alive in 2006.

Funds were also established for community projects to educate Canadians about the impact of past wartime measures and restrictions.

Statements from the Calgary Chinese Culture Centre tell us how Chinese people reacted to the Harper apology.

Alex Louie, a Chinese veteran said, “All I ever wanted was an apology for the government to set the record straight.” Another early pioneer, Mary Mah, stated, “The sorrow and the hardship cannot be erased. But we can now begin to feel, in truth, I did not expect to see this, I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling very Canadian.”

Knowing that the Harper government extended an apology and compensation to the Chinese, we still need to consider whether an apology is enough (see unit three: The Komagata Maru ). In order to fight against all forms of discrimination today, are we not obliged to keep alive the memory of past forms of discrimination? History is something that cannot be changed and a past injustice is not a wound that can be healed—or can it?

Writing a Position Paper

- What do you think can be learned from the Chinese Canadian experience?

- Do you think a group or the government owe a debt to someone for a past injustice?

For this activity you will have an opportunity to share your views on the concept of redressing an injustice. Write a position paper in which you support or oppose the responsibility of the Canadian government to apologize and respond in some manner to the wrongs committed by the governments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

› Consider one or more of the following points that could be included in your paper.

- What would be considered a fair government response to victims and their children?

- What suggestions can you offer about how Canadians should best respond to the head tax?

- Does a government response to the Chinese set an unrealistic precedent for complaints for other injustices?

- How does a redress serve a useful social purpose? What is the best path to inclusion for all minority groups in Canada?

- What differences exist between our ideas of right and wrong in today’s society compared to those that existed in the past 100 years on the topic of immigration?

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Other chapters on Immigration, Migration, Refugees:

- Overview: Who Gets In? Who Does Not?

- Chapter 1: The MS St. Louis

- Chapter 2: Vietnamese Boat People

- Chapter 3: Italian and Irish Immigration

- Chapter 5: Migration and Refugees

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Chinese Culture — The Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act

- Categories: Chinese Culture

About this sample

Words: 1180 |

Published: Mar 3, 2020

Words: 1180 | Pages: 3 | 6 min read

Works Cited

- Chan, A. (2004). Chinese Canadian National Council: Historical Background. In Beyond Golden Mountain: Chinese Cultural Communities in Canada. University of British Columbia Press.

- Lamb, W. K. (2007). Chinese Canadians and the Chinese Exclusion Act: A Long History of Discrimination. In Asian Americans and the Media. Polity Press.

- Li, P. S. (2016). The Chinese in Canada (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- McKenzie, A. M. (1999). Hidden Regime: China's Ban on Chinese Immigration to Canada, 1923-1947. In A Gentleman of Substance: The Life and Legacy of John Redpath (1796-1869). McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Rekai, C. (1997). The Chinese Exclusion Act: A Reference Guide. ABC-CLIO.

- Roy, P. (2007). The Chinese in British Columbia: From Racial Exclusion to Multiculturalism. University of British Columbia Press.

- Sunahara, A. (1988). The politics of racism: The uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. Lorimer.

- Tung, C. (1999). Redress and the Japanese Canadian community: The road to justice. University of Toronto Press.

- Yee, P. (2015). The Chinese Labour Corps: Forgotten Workers in the First World War. In Moving the Mountain: Beyond Ground Zero to a New Vision of Islam in America. Lexington Books.

- Zhang, L., & Li, P. S. (2010). Building the Pacific Railway: The Chinese and the Making of the Canadian State. Fernwood Publishing.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1340 words

1 pages / 1367 words

1 pages / 1814 words

3 pages / 1348 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Chinese Culture

Chess is boring, right? Most students my age wouldn't think it could be used in making life decisions, but not for main character Waverly in the Amy Tan short story, “Rules Of The Game”. In this story, the author uses the [...]

Tan, Amy. 'Rules of the Game.' The Joy Luck Club, Vintage Books, 1989, pp. 158-166.

Carron, A. V. (2017). Group dynamics in sport. Routledge.Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. Anchor.Hsu, C. (2001). Confucianism and Modernization: Industrialization and Democratization of the Confucian Regions. Journal of [...]

Mulan is a Disney movie that debuted in 1998. The movie is set in China during the time of the Hun invasion. Mulan does not like to conform to the traditional Chinese daughter and is somewhat a tomboy. Therefore, Mulan takes it [...]

The "Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee," revolved around a very prominent district magistrate named Judge Dee Goong An, a man famous for his ability to solve mysterious cases. Judge Dee digs deep to solve each case and was [...]

Manhattan's Chinatown stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Chinese immigration to the United States. Established in the 1870s, this vibrant neighborhood has evolved into one of the largest and oldest Chinese ethnic [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Handout A: Background Essay – The History of Immigration Law in the United States

Background Essay—The History of Immigration Law in the United States

Directions: Read the background essay and answer the critical thinking questions at the end. In addition, formulate your own questions about the content discussed.

In the modern era, nation-states are defined as much by their borders as by their unique laws, forms of government, and distinct national cultures. Since the early years of the United States’ history, the federal government has sought, with varying degrees of success, to limit and define the nature and scale of immigration into the country. In the first seventy years of the nation’s history, immigration was left largely unchecked; Congress focused its attention on defining the terms by which immigrants could gain the full legal rights of citizenship. Beginning in the 1880s, however, Congress began to legislate on the national and ethnic makeup of immigrants. Lawmakers passed laws forbidding certain groups from entering the country, and restricted the number of people who could enter from particular nations. In the 1920s, Congress enacted quotas based upon immigrants’ national origin, limiting the number of immigrants who could enter from non-Western European countries. In the 1960s, immigration policy was radically transformed and the policies of the preceding generations were abolished. Through these reforms, which still determine the United States’ immigration policy today, greater numbers of Asians, Africans, and Latin Americans are permitted to enter the country than immigrants of European background, giving preferred status to these immigrant groups.

Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution empowers the Congress to “Establish a Uniform Rule of Naturalization.” The first national law concerning immigration was the Naturalization Act of 1790, which stated that any free white person who had resided in the U.S. for at least two years could apply for full citizenship. Congress also required applicants to demonstrate “good character” and swear an oath to uphold the Constitution. Blacks were ineligible for citizenship.