- 2023 Lancet Countdown U.S. Launch Event

- 2023 Lancet Countdown U.S. Brief

- PAST BRIEFS

2020 CASE STUDY 3

Promoting food security, resilience and equity during climate-related disasters.

The U.S. is often viewed as a nation of abundance , yet paradoxically, one in ten households were “food insecure” in 2019, meaning that they struggle to get the proper nutrition to keep their family healthy. CS_77

These challenges are not borne equally. Rates of food insecurity were nearly three times higher for low-income and single mother-headed households and nearly twice as high for Black and Latino households than for White households.

Early research has found a doubling of the average food insecurity rate across the U.S. linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, with even greater increases among vulnerable populations. CS_78 , CS_79 , CS_80 , CS_81 Disruptive events, whether climate-related disasters or the COVID-19 pandemic, can exacerbate existing barriers to securing healthy food for vulnerable populations and further widen food and health disparities. CS_82

Food insecurity has clear health implications. Adults who are food-insecure may be at an increased risk of health problems, including obesity, heart disease, diabetes, depression, and increased susceptibility to COVID-19. CS_83 , CS_84 , CS_85 Food insecurity also puts children at a higher risk of asthma, anemia, and obesity, as well as behavioral, developmental, and emotional problems. CS_83 , CS_86

Climate-intensified extreme events are compounding existing food insecurity

Climate change is anticipated to worsen existing food insecurity as climate-related disasters, such as drought and flooding, become more frequent and severe and as agricultural pests become more persistent. CS_72 , CS_87 In 2019, there were fourteen climate-related disasters within the U.S. that each caused over a billion dollars in damages. CS_52

Historic floods in the Midwest destroyed millions of acres of agriculture and caused widespread infrastructure damage ( see the Case Study ). In addition, an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season inundated coastlines with unprecedented rainfall, high winds, and storm surge; and wildfires in California and Alaska caused widespread energy disruptions, compromising the health and well-being of residents. CS_52

The mechanisms of food system disruption

Disasters such as these threaten all aspects of food production, distribution, and accessibility, with subsequent impacts for affordability that can further exacerbate food insecurity for vulnerable populations. When food is not consumed where it is produced, it must be processed, stored, transported, and then sold or donated. These processes involve complex interdependent, and at times, international systems. Roads, bridges, warehouses, airports, energy grids, and other transportation or telecommunication infrastructure are at risk of direct damage from climate change, severely disrupting the food system as a whole. CS_88 , CS_89

For example, following the 2019 floods in the Central states, the flood waters caused more than forty state and federal highways to close, hydroelectric dams to be breached, and threatened nuclear power stations (see Case Study). CS_90 , CS_91 These disturbances limited the movement and storage of goods throughout the region and prevented consumers from accessing food sources. CS_91 , CS_92 In the midst of an extreme fire season in California that same year, utility providers turned off power to millions of homes and businesses, plunging low-income households into hunger and financial crisis as their food spoiled. CS_93

Recent climate disasters decreased food security

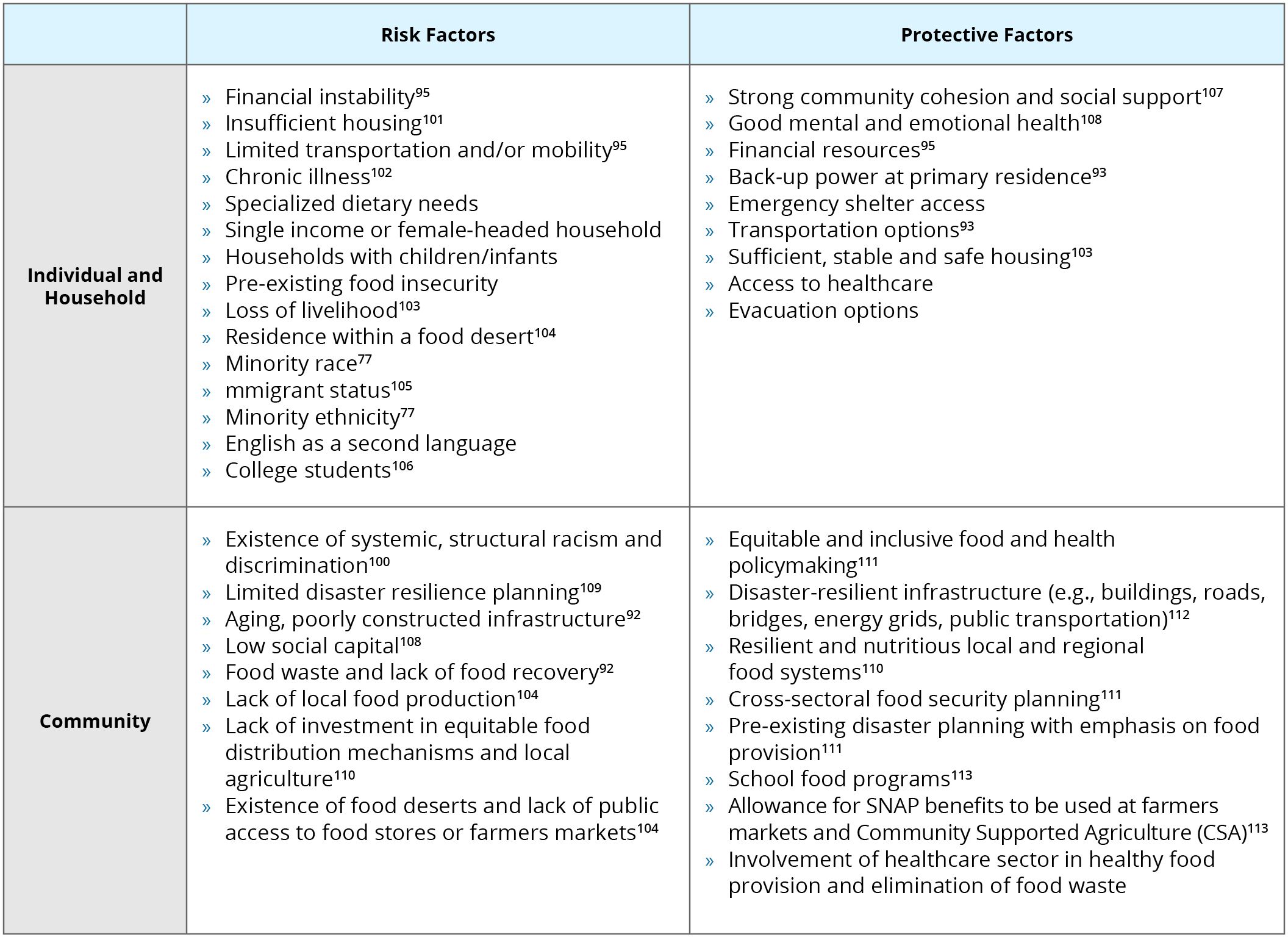

Climate disasters can lead to acute food insecurity in the short-term and exacerbate chronic food insecurity in the long-term (see Table 1). Populations already struggling from chronic insecurity, or those who are only marginally food secure, are particularly vulnerable to the socioeconomic impacts of disasters, such as loss of livelihood, rising food prices, forced migration, loss of social support, and health-related impacts. Data from the aftermath of 2019 disasters is still scarce, but the impacts from previous disasters that are similar in nature are well documented.

Individual, household and community level risk factors to food insecurity following climate-related disasters.

For example, nearly five years after Hurricane Katrina, many of the households heavily impacted by the hurricane in Louisiana and Mississippi remained food insecure. This was especially true for women, Black households, and those living with chronic illness, mental health issues, or low social support. CS_94 Similar impacts were demonstrated in New York City following Hurricane Sandy, where one-third of surveyed households in the heavily impacted Rockaway Peninsula reported difficulty obtaining food due to economic hardship, disruption of public transportation, and long-term closure of grocery stores months after the storm. CS_95

A path towards equitable food security

Learning from baltimore.

In the era of complex disasters, community-level resilience is essential, as federal relief is often too slow and under-equipped to meet the immediate needs of individuals and households. A growing number of U.S. cities are working to protect and improve food security in the aftermath of climate-related disasters and help build climate-resilient local and regional food systems.

For example, officials from Baltimore, Maryland worked with researchers at the Johns Hopkins University in 2017 to assess the resilience of the city’s food supply to climate-related disruptions and to identify ways to support communities at risk of experiencing food insecurity both before and after disasters. CS_96 This is a wonderful example of the power of academic and public partnerships.

Baltimore also designated a food liaison to sit within the Office of Emergency Management during crises. This city received funding from FEMA to coordinate a collaborative regional food and water resilience plan with surrounding jurisdictions. When COVID-19 spread to Baltimore in early 2020 — closing schools and many businesses — the city quickly put its food resilience planning into action and convened a group of food assistance stakeholders to better coordinate responses supporting food access for residents.

Adaptive actions for health and equity

Local and state governments across the country can take similar steps to incorporate food insecurity risk analysis and adaptive planning into emergency management and climate adaptation planning ( see Table 2 ). Local governments and community partners can ensure food assistance programs provide well-balanced meals and are targeted to reach vulnerable individuals and communities.

It is critical to support federal and state assistance programs during non-disaster times, such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and school lunches. As an example, SNAP and WIC services have been pathways to try to meet the rise in food insecurity during the pandemic, and many schools have attempted to continue to provide meals to children most in need. CS_97 , CS_98 Thus, ongoing support can ensure that these programs are even more adaptable, optimally funded, and able to be rapidly mobilized during a disaster of any kind, thus reducing vulnerability and supporting food security in the short- and long-term.

Simultaneously, addressing food insecurity in the wake of disasters goes hand in hand with combating the root causes of food insecurity and health disparities, such as poverty and food deserts. CS_99 Structural racism is also deeply interconnected through complex pathways, including through the creation of disadvantaged social and economic factors that contribute to food insecurity. CS_100 Yet, even when these factors are removed, some evidence suggests food insecurity remains for people of color, highlighting the need for further research. CS_100 Finally, applying a food systems approach to food security after disasters, such as production of and access to healthy foods, and supporting diverse, local, and regional agriculture, is an important long-term strategy with clear benefits for both health and climate change.

Suggested adaptive actions for communities and organizations.

Adaptive actions for communities and organizations.

- Identify and address the impact of systematic racism and discrimination in food insecurity and food distribution systems CS_100 , CS_114

- Assess and consider public access to food for people with limited capacity to travel CS_94

- Promote policies and practices to enhance access to affordability of nutritious foods, including food diversion programs that reduce food waste CS_115

- Increase flexibility and access to emergency food for vulnerable populations (D-SNAP, WIC, food banks, and school meals)

- Screen for food insecurity in the healthcare setting

- Address food sovereignty for tribal and Indigenous people116

- Identify and address food deserts within communities CS_99

- Foster partnerships with local food producers through community cooperatives in order to promote food access and local economic resilience

- Create community collaborations for resource sharing CS_117

- Strengthen social support networks among vulnerable populations CS_117

- Undertake risk assessments to understand climate change threats and the current state of preparedness, specifically with regard to food supply CS_118

- Undertake food vulnerability mapping to understand risk profiles among neighborhoods CS_119

- Promote resilient local and regional agricultural practices, including urban agriculture and community gardens CS_120

- Urban food chain supply resilience CS_121

- Local food system resilience and food insecurity CS_122

- A food systems approach to climate change preparedness CS_103

Introduction Compounding Food Insecurity Mechanisms of Food System Disruption Decreased Food Security A Path Towards Equitable Food Security – Table 1: Food Insecurity Risk Factors Adaptive Actions for Health and Equity – Table 2: Adaptive Actions

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Building food and nutrition resilience in quezon city: a case study on integrated food systems.

Quezon City is at a paradox where some communities suffer from hunger while others are eating too much of the wrong foods. Increasing evidence of the triple burden of malnutrition—undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight/obesity—points to the urgent need for innovative approaches to re-shape urban food environments.

Files available for download

Related topics, more to explore, children eating well in cities: a roadmap for action to support nutritious diets and healthy environments for all children in urban settings, the amsterdam healthy weight approach: investing in healthy urban childhoods: a case study on healthy diets for children, transforming lives with flexible funding.

Timely and flexible funding can save children’s lives today, while helping UNICEF and partners prepare for tomorrow’s threats

Air pollution accounted for 8.1 million deaths globally in 2021, becoming the second leading risk factor for death, including for children under five years

Other content with the tag "Case Study".

The study investigates four Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Mexico, revealing a lack of public information on their implementation and effect

To articulate what it means to take a food systems approach and support policymakers around the world to do so, R4D and City, University of London

Access to Nutrition Initiative (ATNI) has been commissioned to benchmark the world’s 25 largest food and beverage (F&B) companies’ lobbying-rel

Many impact-oriented initiatives are increasingly recognizing the opportunity to support the private sector to empower women in the workplace and g

This study is the result of a landscape analysis undertaken by Action Against Hunger UK for the Global Al

This study was in rural Bangladesh tested the cost effectiveness of a home micronutrient powder food fortification programme for children under the

The Consumer Good Forum (CGF)'s Collaboration for Healthier Lives (CHL) Coalition works to drive collaborative actions through local initiatives to

Almost half of the world’s population – 3 billion people – are directly affected by land degradation.

Nutrition programmes within commodity value chains provide a unique opportunity to improve health outcomes for workers, farmers,

This study looks at research around the implementation of a nutrition programme in a garment factory in Bangladesh.

In 2018, GAIN and HarvestPlus created a partnership with the shared ambition to expand coverage of biofortified nutrient dense foods to at least 20

This study summarises the findings of research undertaken by GAIN and NewForesight to explore the business case for investing in and implementing n

In this research paper, the authors build on nutrition sensitive value chain frameworks and then present an implementation case study that seeks to

As part of the principles of engagement, the global members of the SUN Business Network (SBN) support workforce nutrition commitments (including br

The Partnerships Resource Centre (PrC) conducts research projects to facilitate further knowledge accumulation and learning in the area of sustaina

People’s perception of their ability to meet their needs and the level of autonomy they feel they can exert over their own lives directly correlate

This is an uplifting evidence-based assessment of what it takes to successfully campaign against corporate power.

In this supplement issue of Maternal & Child Nutrition, Helen Keller International ( HKI ) authors have writte

The Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition’s Marketplace for Nutritious Foods program sparks private sector production and marketing of nutritious

This report provides an approach for collaborative policymaking and governance improvement for sustainable food systems.

Ever wondered what it’s like for the people growing your chocolate? Ever thought that they may be children?

The Center for Strategic and International studies have looked at the impact of Feed the Future Investments in Guatemala.

The Center for Strategic and International studies have looked at the impact of Feed the Future Investments in Bangladesh.

The Center for Strategic and International studies have looked at the impact of Feed the Future Investments in Tanzania.

Sight and Life, DSM, and John Hopkin’s Bloomberg School of Public Health have come together to publish lessons from a four decade partnership.

Partnerships for Forests provides financial and technical assistant to help partners do business differently when it comes to land use and preventi

Two page briefing by IBM looking at the causes of supply chain inefficiencies.

Irresponsible resource management does not make business sense – a truism that Kavita Prakash-Mani and Joao Campari at WWF call out in this blog.

Cocoa may not be the most nutritious of agricultural products, but it has huge environmental and economic importance.

This public private partnership in Nigeria demonstrates what can be done to improve crop safety and reduce the non beneficial impacts of toxic crop

Restricted access paper looking at the role for public private partnerships in making agriculture value chains work for smallholder farmers, based

The Demand Engine: Growth Hacking

Partnership between Ipsos – a social market and research company, and The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

FoodSwitch is an example of innovation that is empowering consumers to make smarter nutrition decisions.

Public information on Pepsico's agricultural commodities. For more information on Pepsico’s core business and reporting standards go to our Advanci

Multinationals have the power to change people’s relationship with food – as this short opinion piece demonstrates.

Partnership between Unilever, DSM, Gain, Mondelez, U.N.

The South Asia Food and Nutrition Security Initiative (SAFANSI) is an example of a multi

The cost of a nutritious meal is not fixed and it can be heavily dependent upon the season.

One-page correspondence in the Lancet looking at the benefit of investing in workplace wellness programmes in India.

This report produced by the UK Health Forum provides case studies from around the world to help provide a framework for governing public private in

Realising the potential of workplaces to prevent and control NCDs: How public policy can encourage businesses and governments to work toget

A worksite intervention in South Africa demonstrates the importance of identifying employees with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

China has undergone rapid change in recent years which has impacted on the health of its workforce.

Two-page briefing on a research study by the United Nations International Labour Organisation assessing Chile’s national workforce nutrition progra

An academic paper by the International Food Policy Research Institute looking at expectations that drive formal public private partnerships in agri

This study of agricultural PPPs in Ghana, Malawi, and Kenya calls for governments, donors, and companies to ensure greater participation from small

For anyone interested in the cost-benefit of food fortification as a public health intervention.

This short video shows the successes of public private collaboration in South Africa.

This article has a useful summary of challenges along the food value chain that prevent compliance with national standards.

Nearly half of India’s population suffer from micronutrient deficiency.

Case studies embedded in local political economy, covering: dairy value chains in Afghanistan, milk value chains in Bangladesh, flour fortification

Lindiwe’s personal story leads into an in-depth analysis of supply chain bottlenecks for subsistence farmers.

Companion document to the United States National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Food Service Guidelines in Public Servi

This is the full report from the 2015 Future Fortified Global Summit on Food Fortification - the first ever Global Summit dedicated to large scale

A highly recommended resource on consumer demand from the perspective of public private engagement.

Base of the pyramid typically refers to the largest and poorest socio-economic grouping, and it is estimated that people in this ‘category’ spend u

Improving diets in an era of food market transformation: Challenges and opportunities for engagement between the public and private sectors

Looking outside of the nutrition sector towards the climate change agenda brings a fresh perspective to the issue of incentivising responsible priv

This report, compiled for the European Competitiveness and Sustainable Industrial Policy Consortium, gives a detailed look into the impact of food

Briefing by ActionAid revealing that one in every two dollars of large corporate investment in developing countries is being routed from or a via a

Policy brief by the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition looking at the evidence for gov

Working paper by Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) looking at how corporate social responsibility and supply agree

Dietary Guidelines for Americans set the country’s nutrition policy and help direct over $80 billion federal spending.

This report from FAO and the Food Climate Research Network looks at national dietary guidelines as a practical intervention to improve nutrition an

In this policy brief, the Global Panel makes the case that healthy diets are a foundation underpinning positive progress towards the Sustainable De

Mars have produced a position statement on their contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.

Unilever’s Paul Polman is a Champion 12.3 – part of a global coalition to accelerate action to achieve UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 to half

Report from a workshop on collaborative learning at the Institute of Development Studies in 2017, Brighton, U.K.

This report by the European Union addresses challenges of implementing country cooperation frameworks that fall under the auspices of the New Allia

This report summarizes the findings of a workshop for representatives of the Tanzanian government, development partners, civil society, and private

This 21-page briefing by Society Works summarizes information on 152 social entrepreneurs working on food production, manufacturing, distribution,

Written evidence submitted by Farm Africa and Self Help Africa on December 2012 to the U.K International Development Committee.

Public-Private Partnership Lab: Food and Water is a four-year action research and joint learning initiative to explore the effectiveness of PPPs.

Blog, originally published on Food Security Portal, discussing how global and regional seed companies are working to support smallholder farmers to

This briefing addresses the distinct roles that each partner can play in promoting nutrition under the Comprehensive African Agricultural Developme

Covers a checklist for formal public private partnerships spanning: rationale, design, implementation, sustainability, and the roles for brokers at

A detailed review by the FAO on public private partnerships in agribusiness.

Health gossip is rife in Indonesia.

Presentation for the Wellcome Trust looking at the role of policy on public food choices.

As a systematic and rigorous analysis, this Lancet paper provides perspective on the issue of consumer demand creation by systematically reviewing

The Access to Nutrition Index has produced a 2018 scorecard for Campbell Soup company.

Principles guiding Unilever’s food and beverage marketing communications, including a promise not to direct any marketing communications to childre

A look into how business models can be reshaped to respond to changing consumer preferences.

This is a detailed overview of why people did not take up fortified complementary foods in Ghana, Cote d'Ivoire, India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam.

Alive & Thrive is an initiative that aims to improve infant and young child feeding practices by increasing rates of exclusiv

This paper reviews 41 workforce nutrition interventions published between 1995 and 2006 in the South African Journal of Clinical

Blueprint for Business Action on Health Literacy supports the Europe 2020 strategy and the renewed EU strategy for Corporate Soci

This short report gives an overview of rice fortification literature indexed in PubMed, including examples of successful public private engagement

This lively blog series by Future Fortified - an online platform to explore micronutrient deficiency, covers a range of topics relating to public p

This book examines food fortification in all its forms.

In this synopsis - aimed at business leaders, governments and implementing agencies - IFPRI and Nourishing Millions provide recommendations on how

In 2015 the Nourishing Millions project reviewed literature and case studies to show the evolution of nutrition during the past 50 years.

A concise account of lessons learned on salt and iron iodization by world renowned economists, as part of the costs benefit analysis on leading dev

Written by world renowned economists, this paper highlights the cost efficiency of select nutrition interventions and ranks fortification among the

This report analyses fourteen projects in low and middle income countries working on reducing food loss and waste in food systems.

SNV is a team of advisers that work with business, governments, and implementing agencies.

This presentation is the outcome of a high level policy dialogue in 2015 by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation.

This article by a non-profit called Concordia makes the simple argument that food insecurity and loss can only be addressed by increased collaborat

Recommendations from the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems are targeted at policy makers in low- and middle-income countries

This report looks at supply chain waste based on Feedback's research on export supply chains in Peru, Senegal, South Africa, the UK and a major Eur

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Case studies and evidence based nutrition

Affiliation.

- 1 Fuli Institute of Food Science and Nutrition, Room D437 Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Building, Zijingang Campus, Zhejiang University. [email protected].

- PMID: 24231006

- DOI: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.4.22

Abstract in English, Chinese

The clinical nutrition case study is a neglected area of activity and publication. This may be in part because it is not regarded as a serious contributor to evidence-based nutrition (EBN). Yet it can play a valuable part in hypothesis formulation and in the cross-checking of evidence. Most of all, it is usually a point at which the operationalisation of nutrition evidence is granted best current practice status.

臨床營養之個案研究在施行與出版中是一個被忽視的領域。部分原因可能在 於,它不被視為實證營養學(EBN)之重要貢獻者。然而,它卻在假說成形與交 叉驗證中扮演重要角色。最重要的,在認為營養證據操作化乃是目前最好實 行方式下,個案研究確實有其意義。

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- How evidence-based medicine biases physicians against nutrition. Thomas LE. Thomas LE. Med Hypotheses. 2013 Dec;81(6):1116-9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.10.016. Epub 2013 Oct 30. Med Hypotheses. 2013. PMID: 24238959

- The opportunities and challenges of evidence-based nutrition (EBN) in the Asia Pacific region: clinical practice and policy-setting. Wahlqvist ML, Lee MS, Lau J, Kuo KN, Huang CJ, Pan WH, Chang HY, Chen R, Huang YC. Wahlqvist ML, et al. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(1):2-7. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008. PMID: 18364319 Review.

- Evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines: A valuable resource in the evidence analysis library. Blumberg-Kason S, Lipscomb R. Blumberg-Kason S, et al. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006 Dec;106(12):1935-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.025. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006. PMID: 17126620 No abstract available.

- Seeking the balance between individual and community-based nutritional interventions. Rosser WW. Rosser WW. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005 Aug;59 Suppl 1:S102-5; discussion S106-7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602181. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005. PMID: 16052176 Review. No abstract available.

- Systems for evaluating nutrition research for nutrition care guidelines: do they apply to population dietary guidelines? Myers E. Myers E. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Dec;103(12 Suppl 2):S34-41. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.09.035. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003. PMID: 14666498

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- HEC Press, Healthy Eating Club PTY LTD

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

Creative Steps to Write a Nutrition Case Study

Table of Contents

Nutrition plays a vital role in improving a patient’s health. However, each patient has unique nutritional needs requiring a personalized healthcare approach. That’s where nutrition case studies come in. These case studies comprehensively assess a patient’s nutritional status and help develop an individualized nutrition plan. They also help to monitor and evaluate the patient’s progress toward their health goals over time. In this article, we will provide a step-by-step guide on how to write a nutrition case study . This post will help you understand the importance of nutrition case studies, whether you are a healthcare professional or a student.

What Is a Nutrition Case Study?

A nutrition case study comprehensively reports an individual’s nutritional status, dietary habits, and health outcomes . Healthcare professionals typically use these case studies to evaluate and treat patients. This is with various nutritional concerns, such as obesity, malnutrition, or chronic diseases. If you are a nutrition student or practitioner, learning how to write a nutrition case study is an essential skill to have.

Importance of Nutrition Case Study

Nutrition case studies are a crucial tool for healthcare professionals in nutrition and dietetics. Here are some of the reasons why nutrition case studies are essential:

Provides a Comprehensive Assessment of a Patient’s Nutritional Status

Nutrition case studies involve a detailed analysis of a patient’s dietary intake, medical history, and lifestyle factors that may impact their nutritional status. This information is used to develop a personalized nutrition plan tailored to the patient’s needs.

Develops an Individualized Nutrition Plan

A nutrition case study’s personalized approach to healthcare leads to an individualized nutrition plan. This approach can lead to better patient outcomes, improved health outcomes, and a higher quality of life for the patient.

Monitors and Evaluates Progress Over Time

Nutrition case studies track a patient’s food intake, weight, body composition, and other health outcomes over time. This enables healthcare professionals to monitor and evaluate the patient’s progress toward their health goals and adjust the nutrition plan as needed.

Provides Education About Healthy Eating Habits and Lifestyle Changes

Nutrition case studies can help educate patients about healthy eating habits and lifestyle changes. By providing a detailed assessment of a patient’s nutritional status, healthcare professionals can help patients make sustainable changes to their diet and lifestyle.

Supports Evidence-Based Practice

Nutrition case studies are based on evidence-based practice, meaning the nutrition plan is grounded in scientific research and clinical expertise. This approach ensures that the patient receives the best care based on the latest research and clinical knowledge.

Steps on How to Write a Nutrition Case Study

Selecting the patient.

The first step in writing a nutrition case study is selecting the patient. Typically, the patient has sought out nutritional counseling or treatment for a specific reason. These reasons include weight management, a chronic disease, or a food allergy. The patient should be willing to participate in the case study and provide detailed information about their diet, health history, and lifestyle habits. When selecting a patient, obtaining their written consent to participate in the case study is essential. This should include an explanation of the purpose of the case study and how their information will be used. It should also add any potential risks or benefits of participating. The patient should know that they can stop participating in the research at any moment if they don’t want to.

Gathering Information

The next step in writing a nutrition case study is gathering information about the patient. This includes a comprehensive assessment of their dietary habits, health status, medical history, and lifestyle factors that may impact their nutrition. To gather this information, you may need to conduct a nutrition assessment, which typically includes the following components:

Anthropometric Measurements

This involves measuring the patient’s height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and other body composition measures.

Dietary Intake Assessment

This involves collecting information about the patient’s dietary habits, including food preferences, allergies, and cultural or religious dietary restrictions.

Biochemical Assessment

This involves analyzing the patient’s blood, urine, or other biological samples to assess their nutritional status.

Medical History

This involves collecting information about the patient’s past and current medical conditions, medications, and surgeries.

Lifestyle Assessment

This involves collecting information about the patient’s physical activity, stress, and other lifestyle factors that may impact their nutrition status. Gathering as much information as possible is essential to create a comprehensive nutrition case study. This information will help you develop an individualized nutrition plan addressing the patient’s needs and concerns.

Developing a Nutrition Plan

Once you have gathered all the necessary information, the next step is to develop a nutrition plan for the patient. The nutrition plan should be based on the patient’s dietary needs, health goals, and lifestyle factors. It should also consider any medical conditions or medications that may impact the patient’s nutritional status. The nutrition plan should include the following components:

Macronutrient and Micronutrient Recommendations

This involves recommending specific amounts of carbohydrates, protein, fat, and other essential nutrients the patient should consume daily.

Food Group Recommendations

This involves recommending specific food groups for the patient, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins.

Meal and Snack Recommendations

This involves recommending specific meals and snacks for the patient to meet their nutritional needs throughout the day.

Nutritional Supplements

This involves recommending specific nutritional supplements, such as vitamins, minerals, or protein powders, that may help patients meet their nutritional needs.

Behavioral Recommendations

This involves recommending specific behavioral changes that may impact the patient’s nutrition status, such as increasing physical activity or reducing stress. The nutrition plan should be individualized to the patient’s needs and preferences. It should also be realistic and achievable, considering any barriers the patient may face in following the plan.

Implementing the Nutrition Plan

Once the nutrition plan has been developed, the next step is implementing it with the patient. This may involve educating the patient about healthy eating habits and strategies for making dietary changes. The patient should also be encouraged to track their food intake and monitor their progress toward their health goals. Working collaboratively with the patient throughout the implementation process is essential, as ongoing support and guidance are needed. This may involve regular follow-up appointments or communication via phone or email. The patient should be encouraged to ask questions and share any concerns or challenges they may be experiencing.

Monitoring and Evaluating Progress

The final step in writing a nutrition case study is monitoring and evaluating the patient’s progress. This involves tracking the patient’s food intake, weight, body composition, and other health outcomes. The patient’s progress should be regularly assessed, and adjustments made to the nutrition plan as needed. Objective measures such as laboratory values or body composition assessments are essential to evaluate the patient’s progress. This can help ensure that the nutrition plan is effective and that the patient is progressing toward their health goals.

How to Write a Nutrition Case Study

Once the nutrition plan has been implemented and the patient’s progress has been evaluated, it is time to write the case study. The case study should be organized in a logical and easy-to-read format, and should include the following sections:

Introduction

This should provide an overview of the patient’s case and outline the purpose of the case study.

Patient History

You should provide a comprehensive overview of the patient’s medical history, dietary habits, and lifestyle factors that may impact their nutritional status.

Nutrition Assessment

This should provide a detailed assessment of the patient’s nutritional status, including anthropometric measurements, dietary intake, biochemical markers, and medical history.

Nutrition Plan

This should provide a comprehensive overview of the patient’s individualized nutrition plan. They include macronutrient and micronutrient recommendations, food group recommendations, meal and snack recommendations, nutritional supplement recommendations, and behavioral recommendations.

Implementation and Follow-Up

This should provide an overview of the patient’s progress in implementing the nutrition plan, including any challenges or barriers encountered. It should also outline the follow-up appointments or communication that took place between the patient and healthcare provider.

This should provide an overview of the patient’s progress towards their health goals, including any changes in weight, body composition, or laboratory values.

This should provide an interpretation of the patient’s results, including any limitations or strengths of the case study. It should also provide a summary of the key takeaways and implications for future practice.

Writing a nutrition case study may not be the most exciting task in the world, but it is a crucial one. By following these steps and using a bit of wit and creativity, healthcare professionals can effectively communicate their patient’s nutritional needs . This shows progress toward their health goals. Who knows, maybe writing a nutrition case study will be more fun than you thought!

Abir Ghenaiet

Abir is a data analyst and researcher. Among her interests are artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing. As a humanitarian and educator, she actively supports women in tech and promotes diversity.

Explore All Write A Case Study Articles

How to write a leadership case study (sample) .

Writing a case study isn’t as straightforward as writing essays. But it has proven to be an effective way of…

- Write A Case Study

Top 5 Online Expert Case Study Writing Services

It’s a few hours to your deadline — and your case study college assignment is still a mystery to you.…

Examples Of Business Case Study In Research

A business case study can prevent an imminent mistake in business. How? It’s an effective teaching technique that teaches students…

How to Write a Multiple Case Study Effectively

Have you ever been assigned to write a multiple case study but don’t know where to begin? Are you intimidated…

How to Write a Case Study Presentation: 6 Key Steps

Case studies are an essential element of the business world. Understanding how to write a case study presentation will give…

How to Write a Case Study for Your Portfolio

Are you ready to showcase your design skills and move your career to the next level? Crafting a compelling case…

- Interactivity

- AI Assistant

- Digital Sales

- Online Sharing

- Offline Reading

- Custom Domain

- Branding & Self-hosting

- SEO Friendly

- Create Video & Photo with AI

- PDF/Image/Audio/Video Tools

- Art & Culture

- Food & Beverage

- Home & Garden

- Weddings & Bridal

- Religion & Spirituality

- Animals & Pets

- Celebrity & Entertainment

- Family & Parenting

- Science & Technology

- Health & Wellness

- Real Estate

- Business & Finance

- Cars & Automobiles

- Fashion & Style

- News & Politics

- Hobbies & Leisure

- Recipes & Cookbooks

- Photo Albums

- Invitations

- Presentations

- Newsletters

- Sell Content

- Fashion & Beauty

- Retail & Wholesale

- Presentation

- Help Center Check out our knowledge base with detailed tutorials and FAQs.

- Learning Center Read latest article about digital publishing solutions.

- Webinars Check out the upcoming free live Webinars, and book the sessions you are interested.

- Contact Us Please feel free to leave us a message.

Dietetic and Nutrition Case Studies

Description: dietetic and nutrition case studies, keywords: diet,nutrition, read the text version.

No Text Content!