Business Model Innovation

- First Online: 01 October 2020

Cite this chapter

- Bernd W. Wirtz 2

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Business and Economics ((STBE))

8576 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised. A correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48017-2_22

Business model innovation has received more attention in recent years than nearly all of the other subareas of business model management. In this respect, there is a great interest in literature and practice regarding the conditions, structure and implementation of innovations on the business model level. Since business model innovation is rather abstract compared to product or process innovation, knowledge of the business model concept as well as classic innovation management is necessary in order to better understand it.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

See also for the following chapter Wirtz ( 2010a , 2018a , 2019a ).

Afuah, A. (2004). Business models – A strategic management approach . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Google Scholar

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e-business. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (6), 493–520.

Article Google Scholar

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. Sloan Management Review, 53 (3), 41–49.

Bucherer, E., Eisert, U., & Gassmann, O. (2012). Towards systematic business model innovation: Lessons from product innovation management. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21 (2), 183–198.

Budde, F., Elliot, B. R., Farha, G., & Palmer, C. R. (2000). The chemistry of knowledge. McKinsey Quarterly, 4 , 99–107.

Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Ricart, J. E. (2010). From strategy to business models and to tactics. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 195–215.

Chesbrough, H. (2006). Open business models . Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy & Leadership, 35 (6), 12–17.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 354–363.

Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11 (3), 529–555.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., & West, J. (Eds.). (2006). Open innovation. Researching a new paradigm . Oxford: Oxford University.

Cooper, R. G. (1994). Third-generation new product processes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11 (1), 3–14.

Deloitte. (2002). Business model innovation . New York: Deloitte.

Demil, B., & Lecocq, X. (2010). Business model evolution: In search of dynamic consistency. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 227–246.

Denicolai, S., Ramirez, M., & Tidd, J. (2014). Creating and capturing value from external knowledge: The moderating role of knowledge intensity. R&D Management, 44 (3), 248–264.

Eppler, M. J., & Hoffmann, F. (2012). Does method matter? An experiment on collaborative business model idea generation in teams. Innovations, 14 (3), 388–403.

Gambardella, A., & McGahan, A. M. (2010). Business model innovation: General purpose technologies and their implications for industry structures. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 262–271.

Goffin, K., & Mitchell, R. (2010). Innovation management: Strategy and implementation using the pentathlon framework (2nd ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Günzel, F., & Holm, A. B. (2013). One size does not fit all: Understanding the front-end and back-end of business model innovation. International Journal of Innovation Management, 17 (1), 1–34.

Hamel, G. (2000). Leading the revolution . Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hargadon, A. (2015). How to discover and assess opportunities for business model innovation. Strategy & Leadership, 43 (6), 33–37.

Hauschildt, J., & Salomo, S. (2007). Innovationsmanagement (4th ed.). München: Vahlen.

Hughes, G. D., & Chafin, D. C. (1996). Turning new product development into a continuous learning process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 13 (2), 89–104.

IBM Global CEO Study. (2008). The enterprise of the future: New York . Accessed October 07, 2009, from http://www.935.ibm.com/services/de/bcs/html/ceostudy.html

IBM Institute for Business Value. (2008). Paths to success: Three ways to innovate your business model . http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/index.wss/ibvstudy/gbs/a1028552?cntxt=a1005266 . http://www-935.ibm.com/services/us/index.wss/ibvstudy/gbs/a1028552?cntxt=a1005266

Johnson, M. W., Christensen, C. M., & Kagermann, H. (2008). Reinventing your business model. Harvard Business Review, 89 (12), 50–59.

Keen, P., & Qureshi, S. (2006). Organizational transformation through business models: A framework for business model design. In IEEE Computer Society 2006 (pp. 1–10).

Linder, J. C., & Cantrell, S. (2000). Changing business models: Surveying the landscape. Hamilton.

Lindgardt, Z., Reeves, M., Stalk, G., & Deimler, M. S. (2009). Business model innovation . New York: Boston Consulting Group.

Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80 (5), 86–92.

Mahadevan, B. (2004). A framework for business model innovation. In IMRC (Ed.), IMRC Conference: Bangalore (pp. 16–18).

Malhotra, Y. (2000). Knowledge management and new organization forms: A framework for business model innovation. Information Resources Management Journal, 13 (1), 5–14.

Markides, C. (2006). Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23 (1), 19–25.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wiley.

Porter, M. E. (2004). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance (1st Free Press export ed.). New York: Free Press.

Roberts, E. B. (1987). Generating technological innovation . New York: Oxford University Press.

Rupf, I., & Grief, S. (2002). Automotive components: New business models, new strategic imperatives. Boston.

Schweizer, L. (2005). Concept and evolution of business models. Journal of General Management, 31 (2), 37–56.

Senger, E., & Suter, A. (2007). Wie das Geschäftsmodell innoviert wird. IO New Management, 76 (7–8), 55–58.

Sosna, M., Trevinyo-Rodriguez, N. T., & Velamuri, S. R. (2010). Business model innovation through trial-and-error learning: The naturhouse case. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 383–407.

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 172–194.

Totterdell, P., Leach, D., Birdi, C., & Wall, T. (2002). An investigation of the contents and consequences of major organizational innovations. International Journal of Innovation Management, 6 (4), 343–368.

Voelpel, S. C., Leibold, M., & Tekie, E. B. (2004). The wheel of business model reinvention: How to reshape your business model to leapfrog competitors. Journal of Change Management, 4 (3), 259–276.

Wirtz, B. W. (2000). Electronic business (1st ed.). Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W. (2010a). Business model management: Design – Instrumente – Erfolgsfaktoren von Geschäftsmodellen (1st ed.). Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W. (2011). Business model management: Design – instruments – success factors . Wiesbaden: Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W. (2013a). Business model management: Design, Instrumente, Erfolgsfaktoren von Geschäftsmodellen (3rd ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W. (2018a). Business model management: Design – Instrumente – Erfolgsfaktoren von Geschäftsmodellen (4th ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W. (2019a). Digital business models: Concepts, models, and the alphabet case study. Progress in IS . Cham: Springer.

Wirtz, B., & Daiser, P. (2017). Business model innovation: An integrative conceptual framework. Journal of Business Models, 5 (1), 14–34.

Wirtz, B. W., & Thomas, M.-J. (2014). Design und Entwicklung der business model-innovation. In D. R. A. Schallmo (Ed.), Kompendium Geschäftsmodell-innovation: Grundlagen, aktuelle Ansätze und Fallbeispiele zur erfolgreichen Geschäftsmodell-innovation (pp. 31–47). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Wirtz, B. W., Göttel, V., & Daiser, P. (2016a). Business model innovation: Development, concept and future research directions. Journal of Business Models, 4 (1), 1–28.

Yang, D.-H., You, Y.-Y., & Kwon, H.-j. (2014). A framework for business model innovation using market, component and innovation tool. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 9 (21), 9235–9248.

Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2007). Business model design and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science, 18 (2), 181–199.

Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2010). Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Planning, 43 (2–3), 216–226.

Pohle, George, and Marc Chapman. 2006. “IBM’s global CEO report 2006: business model innovation matters.” Strategy & Leadership 34 (5): 34–40.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chair for Information and Communication Management, German University of Administrative Sciences, Speyer, Germany

Bernd W. Wirtz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Wirtz, B.W. (2020). Business Model Innovation. In: Business Model Management. Springer Texts in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48017-2_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48017-2_9

Published : 01 October 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-48016-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-48017-2

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

How to Identify New Business Models

Systematically exploring alternative approaches to value creation can allow companies to find new opportunities for growth..

- Innovation Strategy

- Business Models

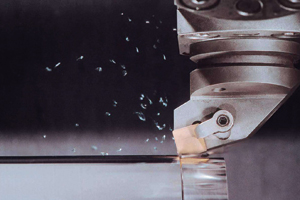

Image courtesy of Kennametal.

Organizations traditionally pursue growth via one or more of three broad paths:

- They invest heavily in product development so they can produce new and better offerings.

- They develop deep consumer insights in order to offer new and better ways to satisfy customers’ needs.

- They concentrate on strategy formulation to grow by acquisition or by moving into new or adjacent markets.

Each of these paths usually involves devoting considerable time and resources to developing a corresponding organizational competency. For example, to build product capability, companies typically invest in in-house research and development departments and/or technology-sourcing expertise. Establishing customer insight capability often requires creating in-house market research units and implementing robust feedback links between the sales force and the developers of product or service lines. And creating a strategy capability generally involves setting up dedicated corporate strategy units and merger and acquisition groups or engaging consultants.

Recently, a fourth path has emerged, one that we might label “business model experimentation”: the pursuit of growth through the methodical examination of alternative business models. At its heart, business model experimentation is a means to explore alternative value creation approaches quickly, inexpensively and, to the extent possible, through “thought experiments.” The process sheds new light on potential competitors and lowers the risk of taking the wrong or a lesser-potential road — all for an initial investment that is typically quite small relative to what can be gained.

Research conducted in the last 10 years has established a link between business model innovation and value creation. 1 To our minds, this research points to the need for organizations to build a competency in business model innovation — that is, in the process of exploring possible business model alternatives that can be pursued to commercialize any given idea prior to going out into the market and expending resources. However, few organizations have successfully conceived and executed a business model different from their current one, fewer still have done it more than once and only a handful have put in place a methodical approach to business model innovation.

Get Updates on Transformative Leadership

Evidence-based resources that can help you lead your team more effectively, delivered to your inbox monthly.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Privacy Policy

Our goal is to demonstrate how an organization’s ability to methodically and routinely examine multiple business model alternatives — in other words, by treating the business model as a variable and not a constant — can serve as a critical enabler of growth, allowing executives to anticipate, adjust to and capitalize on new technologies or customer insights. The approach we describe is based on research over the last two decades into mechanisms of reliable, methodical business model generation as well as our own work helping companies 2 build the capability to create repeatable growth through business model experimentation.

What Is a Business Model?

At a conceptual level, a business model includes all aspects of a company’s approach to developing a profitable offering and delivering it to its target customers. A review of the relevant literature reveals that more than 40 different components — such as target customer, type of offering and pricing approach — have been included in various definitions of business models put forward over the past few decades, with much of the variation stemming from differences between the industries and circumstances in which a definition has been applied. 3

For our purposes, we will explore the concept of a business model by addressing several core questions that the majority of business model researchers deal within their models:

- Who is the target customer?

- What need is met for the customer?

- What offering will we provide to address that need?

- How does the customer gain access to that offering?

- What role will our business play in providing the offering?

- How will our business earn a profit?

In any working business model, the answers to these questions are fixed. But what if they weren’t? What if you considered each of them as a variable? What new opportunities could you capture that you can’t address with your current business model? The answers to these questions form the essence of business model experimentation.

Starting the Process

The first step in the business model exploration process is to create a template to examine possible alternative answers to the questions above. (See “A Business Model Development Template.”) The questions that help to shape a business model represent a series of decisions, each of which has a set of possible outcomes. Our template lays out various possible outcomes within the business model structure. Selecting one possibility from each category and then linking them together forms one potential new way to proceed. And, of course, selecting different combinations creates other possible outcomes.

To see how this works, consider how an airline might use the template to generate alternative business models. Currently, airlines serve a range of customers with the same basic model. For example, regardless of whether the customer is going on vacation with her family, traveling on business or responding to an emergency, airlines use the standard pay-per-seat model with which we are all familiar. Minor levels of customization exist — for example, larger seats and priority boarding for those who pay for them — but the core model is the same for all.

To explore business model innovation, an airline could start by picking a specific customer group and then beginning to explore potential options other than its current model. Answers to the question “How does the customer gain access to the offering?” (which is essentially the same as asking “How will we sell it?”) could include “Through travel agents” or “Through online websites” or “Through self-service kiosks” or “As part of partnerships.” As for where on the value chain the airline might operate, it could be the service provider, but it might also be a wholesaler selling off excess capacity to reduce unprofitable flights. Various profit models would likely start with the traditional pay-per-seat but might expand to include subscription models. The offering itself might be a premium seat, a low-cost seat or maybe even fractional ownership of a plane or chartered use of an aircraft. We experimented with “What we sell” for an airline to show how changing just one variable can result in a substantially different business. (See “Generating New Business Models by Changing One Variable.”)

Working out what elements should be in a business model — and then examining different combinations of them — can be a rapid and robust way to explore the possibilities of business model innovation. This process has the potential, for instance, to uncover combinations that are common in other industries but not in your own. In fact, deliberately applying analogies from other industries (for example, what if a company became the NetJets of agricultural equipment or the Dell of automobiles?) can be highly fruitful. It may also highlight links that create a “systemic” level of competitive advantage in the business concept — much as Apple did with the agreements it made with record labels to distribute songs through its iTunes online music site. Alternatively, the business model innovation process can uncover opportunities to more comprehensively fulfill a customer need than any current competitors do.

A quick run-through of simple combinations of high-level strategic questions can produce a wide range of potential business models. But each of the questions could be examined in more detail in a systematic way to yield deeper insight into some specific aspect of the business. For example, rather than brainstorming various alternatives for the “What we sell” category, a company could break the category down into its constituent parts and ask a series of additional questions such as:

- Should we sell a product or a service?

- Should it be standard or customizable?

- Will its benefits be tangible or intangible?

- Will we sell a generic or branded offering?

- Should it be a durable or a consumable?

We have often found it useful to visualize such choices as switches, or levers, which can be flipped one way or the other. (See “Exploring Offering Options in More Depth.”) You could engage in a similar exercise to systematically explore potential variations in the way a customer might gain access to an offering or the way a customer might pay for it.

Narrowing the Choices

Despite what one might think, these choices are not infinite. In working through possible combinations of variables, it becomes clear that some are inherently interrelated. For example, if the offering is a durable good like a car, it is unlikely that the consumer will need to purchase new ones frequently. Such realizations dramatically reduce the number of options that must be explored.

What’s more, there are likely only a handful of ways that any of these questions can be practically addressed while remaining consistent with the mission of the organization and its “goals and bounds” 4 — that is, what the organization is willing, and not willing, to do. Some answers form a more natural path to making the business more efficient or better able to deliver the existing value proposition. Some will lead to models that are more feasible to implement than others, given the company’s existing competencies and its ability to develop new ones.

In fact, it is possible to use this approach to deliberately align the exploration of alternative business models with wider corporate goals by “locking in” one or more variables as you go about your experimentation. To see how this might work, let’s take a look at two cases in more depth. In the first, a tool manufacturer explores opportunities to enter new lines of business spurred by market trends; in the second, a maker of petroleum additives seeks to identify new ways to employ its core competencies.

Exploring New Customer Needs

Kennametal is a tool manufacturer based in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Faced with an evolving manufacturing environment, a changing customer base and increasing global competition, Kennametal embarked on a business model experimentation initiative to diversify its revenue stream by identifying two to three new businesses in adjacent markets that would leverage core assets. A small team kicked off the initiative with a research effort focused on developing a more comprehensive understanding of potential customers’ frustrations, desires and challenges, in order to populate both the target customer and possible needs categories of the business model template. The research involved a combination of qualitative, quantitative and observational activities. 5

Since the goal was to create diversified revenue streams, Kennametal chose to prioritize needs based on the classic measures of their profit potential: importance to the customer, the customer’s level of dissatisfaction with the offerings currently on the market and the degree to which the need had not already been targeted by other internal efforts. The company then identified three high-potential combinations. For example, one was small “job shops” that had unmet training needs. The next step was to focus on developing the offering and determine how the company would deliver it.

For each possibility, the team methodically reviewed a list of levers for the remaining business model components — for example, “What we sell” and “How we profit” — and articulated multiple options for each lever. By examining more than 30 different levers in multiple combinations, they systematically generated an expansive list of possible business model options. Conceptualizing the different components of a business model as levers forced the team to consider new combinations they likely would have otherwise overlooked. For example, Kennametal has traditionally been a product-centered company that provides service as part of product sales. However, by looking at its service capabilities and examining the options for some “How we profit” levers, the company was able to consider a number of interesting fee-for-service business models. In doing so, Kennametal was essentially exploring ways to monetize the latent wealth of knowledge contained in the organization’s experience, people and knowledge-management systems.

With more than 30 levers, there were literally thousands of possible permutations and, therefore, the last step in the process was to identify the most attractive ones. The team focused on the possibilities that would generate the greatest customer satisfaction, would be the hardest for competitors to copy and were the most feasible to pilot. This process ensured not only that a wide range of options were considered but that the opportunities selected were well matched to customers’ needs, were competitively robust and leveraged existing resources appropriately.

The initiative required a minimal amount of time from a small, multifunctional team over an eight-week period — truly a low-risk way to home in on new growth options. In this way, Kennametal used the business model innovation process to move beyond incremental improvements in its businesses and generate three new opportunities to pursue in adjacent markets. In particular, two of these initiatives formed the foundation of new service-based offerings for Kennametal.

Using Core Competencies to Create New Businesses at Infineum

Infineum, an enterprise based in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, with about 1,600 employees that conducts business in more than 70 countries, is another organization that has used the business model experimentation process. Infineum is one of the leading formulators, manufacturers and marketers of petroleum additives for the fuel and lubricant industry, and its customers are oil and fuel marketers. Infineum’s goal in the business model experimentation process was to leverage its product technology and know-how and create a list of profitable new opportunities that fit with its core competencies.

Since Infineum wished to hold to a strong interpersonal sales model in any initiative it pursued, we locked down the “How we sell” switch and did not consider alternative sales methods. In addition, the company’s goals and boundaries were built into the process by dividing entries under each category into three groups: “desirable,” “discussable” and “unthinkable.” (See “Incorporating Goals and Boundaries into Business Model Experimentation.”)

Given those requirements, within each category each option was considered according to its overall merits. Infineum identified a number of new opportunities, two of which we will now describe in more detail. Both went from inception to commercialization within 18 months, a time frame that is unusual in an industry as asset-intensive as petrochemicals.

Rethinking what we sell. The first example involves additives for the lubrication of high-precision instruments like cameras and robotics. Identifying a commercialization opportunity for this market presented two special challenges to Infineum’s existing business model. First, the amount of lubricant required per instrument is extremely small, so selling the product by the ton, as Infineum usually did, was not appropriate. Second, Infineum was working closely with one particular original equipment manufacturer, which wanted to treat the offerings as a trade secret, whereas Infineum would have normally sought patent protection for its intellectual property.

To address these challenges, a new business model was devised having two key new elements in the “What we sell” and “How we profit” categories. The first element was to charge a regular fee (typically, twice yearly) for work resulting in meeting R&D targets. This fee was charged on the basis of value to the OEM in meeting technical challenges, rather than bearing any relationship to the cost of the R&D, and as such can be considered as the direct monetization of the value of the R&D work. The second element involved licensing the necessary know-how to the OEM and charging royalties linked to the OEM’s use of that know-how, based on the OEM’s unit sales. Revenue from these elements, together with the sales price of additives sold to the OEM, created three distinct income streams, which led to a viable business model for Infineum that was also acceptable to the OEM.

Changing places. The second example shows what can happen when you look at different roles your company might play in the industry value chain. Infineum normally sold diesel and heavy-fuel-oil additives to refineries, with a value proposition based on a combination of high levels of technical performance, lowering costs and a responsive supply chain to deal with fuel-specific requirements. In the new business opportunity, additives are mixed into the fuel after it has left the refinery, typically when it is on board a ship in the port of delivery. Here, the main emphasis is on high levels of responsiveness and very short lead times to minimize the turnaround time of vessels in port.

In this business model, Infineum was operating further along the supply chain than usual, with a very different value proposition. In this case, in order to gain access to the distribution channel, Infineum partnered with a transportation service provider familiar with operating further along the supply chain in this specific market. By holding inventory of product close to the partner’s supply points, Infineum was able to meet the challenge of very short lead times.

Neither of these opportunities could have been captured and commercialized within Infineum’s normal business models. They involved the development of not only new value propositions but new ways to turn a profit and new ways to position the company within the industry value chain. So beyond improving business results by opening new avenues to revenue, these initiatives stretched the organization’s ability to think beyond its traditional competencies.

The Bottom Line

By engaging in business model experimentation with a small, focused team, companies can accomplish three important goals. First, they can understand the implications of different business models and make clearer, better informed decisions about where and how they want to compete. Second, they can identify the business models that will create the most value for customers and themselves and appropriately leverage their existing resources. And third, they can use business model innovation to extract the maximum potential from other growth-focused activities — their technical R&D, customer insight and strategic development efforts. Given the high potential of business model innovation and how few companies have mastered it, we see business model experimentation as a potent source of competitive advantage.

About the Authors

Joseph V. Sinfield is an associate professor of civil engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, and a senior partner at the innovation and strategy consulting firm Innosight. Edward Calder, a principal at Innosight, is based in the firm’s Lexington, Massachusetts, headquarters. Bernard McCon-nell is vice president of WIDIA Products Group at Kennametal, based in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. Steve Colson is a company coach at Open Water Development Ltd. and a former general manager of growth initiatives at petroleum-additive maker Infineum in the United Kingdom.

1. See T.W. Malone, P. Weill, R.K. Lai, V.T. D’Ursio, G. Herman, T.G. Apel and S.L. Woerner, “Do Some Business Models Perform Better Than Others? “Working paper 4615-06, MIT Sloan School of Management, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2006) May 16; S.M. Shafer, H.J. Smith and J.C. Linder, “The Power of Business Models,” Business Horizons 48, no. 3, (2005): 199-207; E. Giesen, S.J. Berman, R. Bell and A. Blitz, “Three Ways to Successfully Innovate Your Business Model,” Strategy & Leadership 35, no. 6 (2007): 27-33; and M.W. Johnson, C.M. Christensen and H. Kagermann, “Reinventing Your Business Model,” Harvard Business Review, 86, no. 12 December 2008: 51-59. In a study of 1,000 of the largest U.S. firms, for example, Malone et al. called attention to the link and mapped out a comprehensive classification system that can be employed both to categorize and to develop business models. Shafer et al. described the benefits General Motors gained by employing business model innovation in the development of OnStar, and contrasted this success story with the narrow and less innovative approach employed to define the business model for eToys in the late 1990s. Giesen et al. examined 35 financially successful enterprises and outlined three distinct paths to business model innovation — industry, revenue and enterprise model innovation — that were at the core of their success. Further, Johnson et al. explored the stories of P&G, Tata, Hilti and Dow Corning to emphasize the financial and long-term competitive differentiation benefits that companies can achieve through business model innovation.

2. Johnson et al., “Reinventing Your Business Model.”

3. Shafer et al., “The Power of Business Models”; and M. Morris, M. Schindehutte and J. Allen, “The Entrepreneur’s Business Model: Toward a Unified Perspective,” Journal of Business Research 58, no. 6 (June 2005): 726-735.

4. J.V. Sinfield and S.D. Anthony, “Constraining Innovation: How Developing and Continually Refining Your Organization’s Goals and Bounds Can Help Guide Growth,” Strategy & Innovation 4, no. 6 (November-December 2006): 1, 6-9.

5. For more on conducting research into discovering such needs see, for example, C.M. Christensen and M.E. Raynor, “The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Press, 2003); and S.D. Anthony and J.V. Sinfield, “Product for Hire: Master the Innovation Life Cycle With a Jobs-to-be-done Perspective of Markets,” Marketing Management 16, no. 2 (March-April, 2007): 18-24.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (8)

Ghislain paradis, shengzhou wang, [email protected], patrick.staehler, jim.kalbach.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Student blogs and videos

- Why Cambridge

- Qualifications directory

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Frequently asked questions

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Term dates and calendars

- Video and audio

- Find an expert

- Publications

- International Cambridge

- Public engagement

- Giving to Cambridge

- For current students

- For business

- Colleges & departments

- Libraries & facilities

- Museums & collections

- Email & phone search

Faculty of Economics

- Research overview

- Econometrics Research Group - Papers

- Econometrics Research Group - Cambridge Working Papers in Economics

- Microeconomic Theory Research Group - Papers

- Microeconomic Theory Research Group - Cambridge Working Papers in Economics

- Macroeconomics Research Group - Papers

- Macroeconomics Research Group - Cambridge Working Papers in Economics

- Empirical Microeconomics Research Group

- Empirical Microeconomics Research Group - Cambridge Working Papers in Economics

- History Research Group - Cambridge Working Papers in Economics

- Papers and Publications

- Cambridge Working Papers in Economics (CWPE)

- Research Intranet (Raven Login Required)

- The Janeway Institute

- The Keynes Fund

- Research Contact

- People overview

- Noriko Amano-Patiño

- Debopam Bhattacharya

- Florin Bilbiie

- Peter Bossaerts

- Charles Brendon

- Vasco Carvalho

- Tiago Cavalcanti

- Meredith Crowley

- Matthew Elliott

- Aytek Erdil

- Robert Evans

- Elisa Faraglia

- Leonardo Felli

- Eric French

- Edoardo Gallo

- Tripos supervisions

- Chryssi Giannitsarou

- Selected Articles

- Working Papers

- Popular Press

- Past PhD Students

- Invited Lectures

- Christopher Harris

- Economics of Religion in India Book

- Demography Book

- Oliver Linton

- An old link to some of my papers

- A poem by Robert Graves

- Christopher Rauh

- Alexander Rodnyansky

- Mikhail Safronov

- Gabriella Santangelo

- Flavio Toxvaerd

- Julius Vainora

- Some Recent Articles

- Research Projects

- Efficiency Assessment

- Supervisions

- Weilong Zhang

- Ivano Cardinale

- Giancarlo Corsetti

- William H Janeway

- Pierre Mella-Barral

- Theofanis Papamichalis

- Simona Paravani

- Mark Salmon

- Patrick Allmis

- Nazanin Babolmorad

- Seda Basihos

- Leonard Bocquet

- Daniele Cassese

- George Charlson

- Chuan-Han Cheng

- Joris Hoste

- Konstantinos Ioannidis

- Caroline Liqui Lung

- Antonis Ragkousis

- Jason Schoeters

- Jerome Simons

- Robert Woods

- Michael Ashby

- Victoria Bateman

- Francisco Beltran

- Collin Constantine

- Yujiang River Chen

- Rupert Gatti

- Emanuele Giovannetti

- Pauline Goyal-Rutsaert

- Myungun Kim

- Nigel Knight

- Vasileios Kotsidis

- Domique Lauga

- Kamiar Mohaddes

- Mary Murphy

- Dario Palumbo

- Cristina Peñasco

- Cristiano Ristuccia

- Isabelle Roland

- Julia Shvets

- Oleh Stupak

- Simon Taylor

- Anna Watson

- Publications - Since 2001

- Interviews and Lectures

- Jeremy Edwards

- Refereed Papers

- Other Publications

- Work in Progress

- Selected Publications

- Downloadable Publications

- Economics as Social Theory

- Sir James Mirrlees

- Downloadable Conference Presentations

- Regulation, Privatisation, Energy, Electricity

- Transport: Road and Rail

- Risk, Industrial Organisation, Optimal Growth, Dynamic Inconsistency

- Taxation, Public finance, Cost-benefit analysis

- Transition Economies and Development

- Recent Conference Presentations

- Jose Gabriel Palma

- Published Articles

- Forthcoming Papers

- Newspaper, Magazine and Online Articles

- Forewords/Prefaces

- Book Reviews

- Unpublished Papers

- Lecture Audio, Video and Podcast Recordings

- Archive Working Papers

- Biographical

- Biographical (long version)

- William Peterson

- Bob Rowthorn

- Honours and Awards

- Geoff Whittington

- Selection Committee

- Academic Staff - A to E

- Academic Staff - F to H

- Academic Staff - I to M

- Academic Staff - N to Q

- Academic Staff - R to V

- Academic Staff - W to Z

- Academic Staff - Office Hours

- Past Visitors

- Prospective Academic Visitors Information

- Application Form

- Rules and Categories of Visitors

- Visiting Doctoral Students

- Visiting Students Application Form

- Razan Amine

- Laura Araújo De Freitas

- Marium Ashfaq

- Deniz Atalar

- Kilian Bachmair

- Gerardo Baldo

- Balduin Bippus

- Saru Chaudhary

- Adrian Chung

- Radu Cristea

- Zixuan Deng

- Mar Domenech-Palacios

- Lukas Freund

- Luigi Dante Gaviano

- Guillem Gordo-I-Bach

- Darija Halatova

- Andrew Hannon

- Lea Havemeister

- Shengjuan He

- Rebecca Heath

- Christian Höhne

- Darren Hoover

- Benedikt Kagerer

- Kilian Kamkar

- Ganesh Karapakula

- Alastair Langtry

- Sean Lavender

- Weiguang Liu

- Ana Lleo-Bono

- Fred Seunghyun Maeng

- Shane Mahen

- Fergus McCormack

- Manuel Montesinos

- Mathis Momm

- Jamie Moore

- James Morris

- Shania Mustika

- Felix Mylius

- Cheuk Fai Ng

- Lennart Niermann

- Tianyu Pang

- Charles Parry

- Dmitrii Petrukhin

- Benjapon Prommawin

- Vivek Roy-Chowdhury

- Diogo Salgado Baptista

- Niklas Schmitz

- Kishen Shastry

- Sarah Rose Taylor

- Christian Tien

- Ho-Yung Antonia Tsang

- Carles Vila Martínez

- Nicholas Waltz

- Yi (Amanda) Wang

- Shu Feng Wei

- Alessa Widmaier

- Mingmei Xiao

- Yinfeng Zeng

- Mingxi Zhang

- Xiaoxiao Zhang

- Yiyang Zhang

- Yuting (Tina) Zhang

- Zhaocheng Zhang

- Henning Zschietzschmann

- Professional Services Staff

- Job Market Candidates

- Teaching overview

- University's Blended Learning Site

- Apply overview

- Economics Open Days 2023

- Economics Prospectus

- A Guide for Prospective Students

- Preliminary Part I Reading List

- Why Choose Economics

- Course Description

- Course Structure

- Course Requirements

- How to Apply

- Students Finance

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Entry Requirements

- How and When to Apply

- Finance Overview and Funding

- Core Modules

- Optional Modules

- Applicant Mentoring Programme

- Doctoral Training Partnership

- ESRC Studentships

- Example Course Structure

- Faculty PhD Supervisors

- PhD Modules

- Careers / Placements

- EDGE (European Doctoral Group in Economics)

- Social Events

- Postgraduate Open Day

- Postgraduate Life

- Postgraduate Guide 2023

- Cambridge University Graduate Economics Society

- Economics Postgraduate Fund

- Postgraduate Admissions - Contacts

- The Cambridge Environment

- Introduction to the Faculty

- Student Life

- Alumni overview

- Alumni Newsletter

- Alumni Webinars

- Online Giving

- Faculty Info overview

- Information for Staff (Intranet)

- Find the Faculty

- Provision for Students with Disabilities

- History of the Faculty

- Sheilagh Ogilvie

- Caroline Hoxby

- Joan Robinson

- Women in Economics Events

- Student & Staff Behaviour

- Women in Economics

- Faculty IT Support

Business Model Innovation Book Published

Professor Chander Velu of the Cambridge University Engineering Department is a Faculty of Economics alumnus (MPhil in Finance, 1994/5). If you work in the area of business strategy and innovation management, or you are just interested in the challenges facing firms today, 'Business Model Innovation: A Blueprint for Strategic Change' is an interesting read.

The book focusses on the underpinning theory and concepts of business model innovation covering topics such as market creation, leadership, digital technology adoption, small- and medium-sized enterprises, start-ups, sustainability, socio-economic development, conduct risk and the role of government in influencing business model design.

https://www.cambridge.org/gb/universitypress/subjects/management/entrepreneurship-and-innovation/business-model-innovation-blueprint-strategic-change?format=PB

Photo credit The Productivity Institute

Latest News

View all news stories

Most Common Keywords

View all keywords

Faculty Events

2024 (Current) 2023 Archive 2022 Archive 2021 Archive 2020 Archive 2019 Archive 2018 Archive 2017 Archive 2016 Archive 2015 Archive 2014 Archive 2013 Archive 2012 Archive 2011 Archive 2010 Archive

Faculty News

2024 (Current) 2023 Archive 2022 Archive (old) 2021 Archive (old) 2020 Archive (old) 2019 Archive (old) 2018 Archive (old) 2017 Archive (old) 2016 Archive (old) 2015 Archive (old) 2014 Archive (old) 2013 Archive (old) 2012 Archive (old) 2011 Archive (old) 2010 Archive (old)

Media Mentions

Faculty of Economics Austin Robinson Building Sidgwick Avenue Cambridge CB3 9DD UNITED KINGDOM

Telephone: +44 1223 335200

Fax: +44 1223 335475

Site Privacy & Cookie Policies

Find Us (details and maps)

with University of Cambridge Maps

with Google Maps

Associated Websites

Janeway Institute

COVID-19 Economic Research

Keynes Fund

Application Emails

Undergraduate Admissions: (for enquiries about the BA in Economics) [email protected]

Graduate Admissions: (for enquiries about the Diploma, MPhil and PhD courses) [email protected]

General Emails

Faculty Office: (for all other enquiries) [email protected]

Webmaster: (for enquiries about the website) [email protected]

Marshall Library: [email protected]

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- University A-Z

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Terms and conditions

- Undergraduate

- Spotlight on...

- About research at Cambridge

What is decision making?

Decisions, decisions. When was the last time you struggled with a choice? Maybe it was this morning, when you decided to hit the snooze button—again. Perhaps it was at a restaurant, with a miles-long menu and the server standing over you. Or maybe it was when you left your closet in a shambles after trying on seven different outfits before a big presentation. Often, making a decision—even a seemingly simple one—can be difficult. And people will go to great lengths—and pay serious sums of money—to avoid having to make a choice. The expensive tasting menu at the restaurant, for example. Or limiting your closet choices to black turtlenecks, à la Steve Jobs.

Get to know and directly engage with senior McKinsey experts on decision making

Aaron De Smet is a senior partner in McKinsey’s New Jersey office, Eileen Kelly Rinaudo is McKinsey’s global director of advancing women executives and is based in the New York office, Frithjof Lund is a senior partner in the Oslo office, and Leigh Weiss is a senior adviser in the Boston office.

If you’ve ever wrestled with a decision at work, you’re definitely not alone. According to McKinsey research, executives spend a significant portion of their time— nearly 40 percent , on average—making decisions. Worse, they believe most of that time is poorly used. People struggle with decisions so much so that we actually get exhausted from having to decide too much, a phenomenon called decision fatigue.

But decision fatigue isn’t the only cost of ineffective decision making. According to a McKinsey survey of more than 1,200 global business leaders, inefficient decision making costs a typical Fortune 500 company 530,000 days of managers’ time each year, equivalent to about $250 million in annual wages. That’s a lot of turtlenecks.

How can business leaders ease the burden of decision making and put this time and money to better use? Read on to learn the ins and outs of smart decision making—and how to put it to work.

Learn more about our People & Organizational Performance Practice .

How can organizations untangle ineffective decision-making processes?

McKinsey research has shown that agile is the ultimate solution for many organizations looking to streamline their decision making . Agile organizations are more likely to put decision making in the right hands, are faster at reacting to (or anticipating) shifts in the business environment, and often attract top talent who prefer working at companies with greater empowerment and fewer layers of management.

For organizations looking to become more agile, it’s possible to quickly boost decision-making efficiency by categorizing the type of decision to be made and adjusting the approach accordingly. In the next section, we review three types of decision making and how to optimize the process for each.

What are three keys to faster, better decisions?

Business leaders today have access to more sophisticated data than ever before. But it hasn’t necessarily made decision making any easier. For one thing, organizational dynamics—such as unclear roles, overreliance on consensus, and death by committee—can get in the way of straightforward decision making. And more data often means more decisions to be taken, which can become too much for one person, team, or department. This can make it more difficult for leaders to cleanly delegate, which in turn can lead to a decline in productivity.

Leaders are growing increasingly frustrated with broken decision-making processes, slow deliberations, and uneven decision-making outcomes. Fewer than half of the 1,200 respondents of a McKinsey survey report that decisions are timely, and 61 percent say that at least half the time they spend making decisions is ineffective.

What’s the solution? According to McKinsey research, effective solutions center around categorizing decision types and organizing different processes to support each type. Further, each decision category should be assigned its own practice—stimulating debate, for example, or empowering employees—to yield improvements in effectiveness.

Here are the three decision categories that matter most to senior leaders, and the standout practice that makes the biggest difference for each type of decision.

- Big-bet decisions are infrequent but high risk, such as acquisitions. These decisions carry the potential to shape the future of the company, and as a result are generally made by top leaders and the board. Spurring productive debate by assigning someone to argue the case for and against a potential decision can improve big-bet decision making.

- Cross-cutting decisions, such as pricing, can be frequent and high risk. These are usually made by business unit heads, in cross-functional forums as part of a collaborative process. These types of decisions can be improved by doubling down on process refinement. The ideal process should be one that helps clarify objectives, measures, and targets.

- Delegated decisions are frequent but low risk and are handled by an individual or working team with some input from others. Delegated decision making can be improved by ensuring that the responsibility for the decision is firmly in the hands of those closest to the work. This approach also enhances engagement and accountability.

In addition, business leaders can take the following four actions to help sustain rapid decision making :

- Focus on the game-changing decisions, ones that will help an organization create value and serve its purpose.

- Convene only necessary meetings, and eliminate lengthy reports. Turn unnecessary meetings into emails, and watch productivity bloom. For necessary meetings, provide short, well-prepared prereads to aid in decision making.

- Clarify the roles of decision makers and other voices. Who has a vote, and who has a voice?

- Push decision-making authority to the front line—and tolerate mistakes.

Introducing McKinsey Explainers : Direct answers to complex questions

How can business leaders effectively delegate decision making.

Business is more complex and dynamic than ever, meaning business leaders are faced with needing to make more decisions in less time. Decision making takes up an inordinate amount of management’s time—up to 70 percent for some executives—which leads to inefficiencies and opportunity costs.

As discussed above, organizations should treat different types of decisions differently . Decisions should be classified according to their frequency, risk, and importance. Delegated decisions are the most mysterious for many organizations: they are the most frequent, and yet the least understood. Only about a quarter of survey respondents report that their organizations make high-quality and speedy delegated decisions. And yet delegated decisions, because they happen so often, can have a big impact on organizational culture.

The key to better delegated decisions is to empower employees by giving them the authority and confidence to act. That means not simply telling employees which decisions they can or can’t make; it means giving employees the tools they need to make high-quality decisions and the right level of guidance as they do so.

Here’s how to support delegation and employee empowerment:

- Ensure that your organization has a well-defined, universally understood strategy. When the strategic intent of an organization is clear, empowerment is much easier because it allows teams to pull in the same direction.

- Clearly define roles and responsibilities. At the foundation of all empowerment efforts is a clear understanding of who is responsible for what, including who has input and who doesn’t.

- Invest in capability building (and coaching) up front. To help managers spend meaningful coaching time, organizations should also invest in managers’ leadership skills.

- Build an empowerment-oriented culture. Leaders should role model mindsets that promote empowerment, and managers should build the coaching skills they want to see. Managers and employees, in particular, will need to get comfortable with failure as a necessary step to success.

- Decide when to get involved. Managers should spend effort up front to decide what is worth their focused attention. They should know when it’s appropriate to provide close guidance and when not to.

How can you guard against bias in decision making?

Cognitive bias is real. We all fall prey, no matter how we try to guard ourselves against it. And cognitive and organizational bias undermines good decision making, whether you’re choosing what to have for lunch or whether to put in a bid to acquire another company.

Here are some of the most common cognitive biases and strategies for how to avoid them:

- Confirmation bias. Often, when we already believe something, our minds seek out information to support that belief—whether or not it is actually true. Confirmation bias involves overweighting evidence that supports our belief, underweighting evidence against our belief, or even failing to search impartially for evidence in the first place. Confirmation bias is one of the most common traps organizational decision makers fall into. One famous—and painful—example of confirmation bias is when Blockbuster passed up the opportunity to buy a fledgling Netflix for $50 million in 2000. (Actually, that’s putting it politely. Netflix executives remember being “laughed out” of Blockbuster’s offices.) Fresh off the dot-com bubble burst of 2000, Blockbuster executives likely concluded that Netflix had approached them out of desperation—not that Netflix actually had a baby unicorn on its hands.

- Herd mentality. First observed by Charles Mackay in his 1841 study of crowd psychology, herd mentality happens when information that’s available to the group is determined to be more useful than privately held knowledge. Individuals buy into this bias because there’s safety in the herd. But ignoring competing viewpoints might ultimately be costly. To counter this, try a teardown exercise , wherein two teams use scenarios, advanced analytics, and role-playing to identify how a herd might react to a decision, and to ensure they can refute public perceptions.

- Sunk-cost fallacy. Executives frequently hold onto underperforming business units or projects because of emotional or legacy attachment . Equally, business leaders hate shutting projects down . This, researchers say, is due to the ingrained belief that if everyone works hard enough, anything can be turned into gold. McKinsey research indicates two techniques for understanding when to hold on and when to let go. First, change the burden of proof from why an asset should be cut to why it should be retained. Next, categorize business investments according to whether they should be grown, maintained, or disposed of—and follow clearly differentiated investment rules for each group.

- Ignoring unpleasant information. Researchers call this the “ostrich effect”—when people figuratively bury their heads in the sand , ignoring information that will make their lives more difficult. One study, for example, found that investors were more likely to check the value of their portfolios when the markets overall were rising, and less likely to do so when the markets were flat or falling. One way to help get around this is to engage in a readout process, where individuals or teams summarize discussions as they happen. This increases the likelihood that everyone leaves a meeting with the same understanding of what was said.

- Halo effect. Important personal and professional choices are frequently affected by people’s tendency to make specific judgments based on general impressions . Humans are tempted to use simple mental frames to understand complicated ideas, which means we frequently draw conclusions faster than we should. The halo effect is particularly common in hiring decisions. To avoid this bias, structured interviews can help mitigate the essentializing tendency. When candidates are measured against indicators, intuition is less likely to play a role.

For more common biases and how to beat them, check out McKinsey’s Bias Busters Collection .

Learn more about Strategy & Corporate Finance consulting at McKinsey—and check out job opportunities related to decision making if you’re interested in working at McKinsey.

Articles referenced include:

- “ Bias busters: When the crowd isn’t necessarily wise ,” McKinsey Quarterly , May 23, 2022, Eileen Kelly Rinaudo , Tim Koller , and Derek Schatz

- “ Boards and decision making ,” April 8, 2021, Aaron De Smet , Frithjof Lund , Suzanne Nimocks, and Leigh Weiss

- “ To unlock better decision making, plan better meetings ,” November 9, 2020, Aaron De Smet , Simon London, and Leigh Weiss

- “ Reimagine decision making to improve speed and quality ,” September 14, 2020, Julie Hughes , J. R. Maxwell , and Leigh Weiss

- “ For smarter decisions, empower your employees ,” September 9, 2020, Aaron De Smet , Caitlin Hewes, and Leigh Weiss

- “ Bias busters: Lifting your head from the sand ,” McKinsey Quarterly , August 18, 2020, Eileen Kelly Rinaudo

- “ Decision making in uncertain times ,” March 24, 2020, Andrea Alexander, Aaron De Smet , and Leigh Weiss

- “ Bias busters: Avoiding snap judgments ,” McKinsey Quarterly , November 6, 2019, Tim Koller , Dan Lovallo, and Phil Rosenzweig

- “ Three keys to faster, better decisions ,” McKinsey Quarterly , May 1, 2019, Aaron De Smet , Gregor Jost , and Leigh Weiss

- “ Decision making in the age of urgency ,” April 30, 2019, Iskandar Aminov, Aaron De Smet , Gregor Jost , and David Mendelsohn

- “ Bias busters: Pruning projects proactively ,” McKinsey Quarterly , February 6, 2019, Tim Koller , Dan Lovallo, and Zane Williams

- “ Decision making in your organization: Cutting through the clutter ,” McKinsey Quarterly , January 16, 2018, Aaron De Smet , Simon London, and Leigh Weiss

- “ Untangling your organization’s decision making ,” McKinsey Quarterly , June 21, 2017, Aaron De Smet , Gerald Lackey, and Leigh Weiss

- “ Are you ready to decide? ,” McKinsey Quarterly , April 1, 2015, Philip Meissner, Olivier Sibony, and Torsten Wulf.

Want to know more about decision making?

Related articles.

What is productivity?

What is the future of work?

What is leadership?

- Youth Program

- Wharton Online

The Wharton School Makes Strategic Investment in Artificial Intelligence Research and Teaching

School establishes Wharton AI & Analytics Initiative, announces first business school collaboration with OpenAI

As part of the initiative, Wharton will begin providing ChatGPT Enterprise licenses to all full-time and executive MBA students this fall to further enable their exploration of generative AI. This innovation marks the first such collaboration between a business school and OpenAI, the company that makes ChatGPT.

“Exponential advances in AI are already changing how we live, learn, and work,” said Interim President J. Larry Jameson. “Like education, business must either lead this technological revolution or be led, and who better to help blaze the trail than the number one business school in the world? The new Wharton AI & Analytics Initiative is bold, leverages our strengths, and exemplifies Penn’s strategic leadership on great challenges of our time.”

Wharton has a long history of discerning the burgeoning challenges of the day and applying a data-informed approach to address societal needs. This latest initiative builds on Wharton’s extensive expertise in analytics and will significantly broaden the scope and impact of the School’s AI aspirations.

“Artificial intelligence is poised to fundamentally transform every sector of business and society, and the world needs reliable, evidence-based insights about its practical and responsible use today ,” said Erika James, Dean of the Wharton School. “Business schools have a crucial role to play in understanding and advancing an AI-enabled world, and no school is better positioned to examine the multi-faceted dimensions of this evolving phenomenon than Wharton. That’s why we are investing heavily in areas that allow our faculty to navigate the avalanche of interrelated issues AI has broached.”

In support of this initiative, Wharton will establish two new funds to jumpstart efforts in research and teaching. A newly created Wharton AI Research Fund will provide faculty with critical resources to pursue projects exploring the intersection of AI advancement and modern business models, industries, and global economies. Additionally, an Education Innovation Fund has been developed to support curricular innovation by providing resources for faculty to augment, adapt, and reimagine how they incorporate AI into classroom instruction and course materials.

Building on the groundbreaking research explored in centers like AI at Wharton and the Mack Institute for Innovation Management, the initiative will further galvanize scholars across Wharton’s ten academic departments to explore AI’s impact on subjects like marketing, finance, investing, entrepreneurship, health care, and workforce productivity, while also considering AI’s ethical and accountability impact. The work will focus heavily on fostering collaboration between industry and academia to integrate a range of viewpoints and ensure the creation of value-added business learning and solutions.

The Wharton AI & Analytics Initiative will be led by Eric Bradlow, Vice Dean for AI & Analytics at Wharton, who is the K.P. Chao Professor, Professor of Marketing, Statistics and Data Science, Economics and Education. Professor Bradlow, who co-founded at Wharton the first-ever center on the application of data science to business, is an applied statistician with deep expertise in analytics and extensive experience engaging the business community.

“We aim to be the preeminent business school for student learning experiences, faculty exploration opportunities, and industry and academic thought partnership on AI and its impact on society,” said Bradlow. “This is a critical moment, and we are committed to creating and broadly sharing the novel scholarship the world needs to realize the tremendous promise of AI.”

The School is also building a new, open-source platform focused on the swift and iterative development of GenAI prototypes aimed at improving how society works and learns. By empowering learners through tailored AI educational experiences, the School aspires to shape the overall direction of generative AI while also mitigating its risks and dangers.

“Developing a fluency in AI and its impact on business decision-making is no longer an option, it’s a requirement to be competitive in any organization,” said Deputy Dean Nancy Rothbard. “We are once again answering society’s call to address the needs of tomorrow and we’re excited to provide our students and the business world with the tools and applicable knowledge they need to excel as we collectively confront the most transformative technology of our time.”

For more information about the Wharton AI & Analytics Initiative, visit https://ai-analytics.wharton.upenn.edu .

About the Wharton School Founded in 1881 as the world’s first collegiate business school, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania is shaping the future of business by incubating ideas, driving insights, and creating leaders who change the world. With a faculty of more than 235 renowned professors, Wharton has 5,000 undergraduate , MBA , executive MBA , and doctoral students. Each year 100,000 professionals from around the world advance their careers through Wharton Executive Education ’s individual, company-customized, and online programs, and thousands of pre-collegiate students explore business concepts through Wharton’s Global Youth Program . More than 105,000 Wharton alumni form a powerful global network of leaders who transform business every day. For more information, visit www.wharton.upenn.edu .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How Marketers Can Adapt to LLM-Powered Search

- Stefano Puntoni,

- Mike Ensing,

- Jarvis Bowers

With the addition of AI-generated overviews, Google, Perplexity, OpenAI and other search engines are changing how consumers find information.

Large language models (LLMs) provide a search experience that’s dramatically different from the web-browser experience. The biggest difference is this: LLMs promise to answer queries not with links, as web browsers do, but with answers . Increasingly, using apps such as ChatGPT or Perplexity, or search portals such as Google’s Search Generative Experience (now AI Overviews) or Bing’s Copilot, customers will learn about products and brands through natural-language outputs. And that process, which will be highly consultative and conversational, will create a new information pipeline that marketers need to monitor to ensure their brands are presented for relevant prompts and described accurately. The authors present three ways for marketers to rise to this challenge.

For millions of consumers around the world, Google is the access point to the internet — and as a result, the company today enjoys a 91% market share in the $50 billion market for search ads. However, thanks to the advent of large language models (LLMs), a shakeup now seems possible for the first time in two decades.

- SP Stefano Puntoni is a professor of marketing at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, and the co-author of Decision-Driven Analytics: Leveraging Human Intelligence to Unlock the Power of Data (Wharton Press).

- ME Mike Ensing is the CEO and co-founder of Revere. He is an entrepreneur, advisor, and tech-industry executive focused on generative AI and its applications for enterprises and brands and has held senior and advisory positions with leading companies such as RealNetworks, Microsoft, and McKinsey.

- JB Jarvis Bowers is the COO and co-founder of Revere, an emerging marketing-technology company focused on elevating brands with LLMs and generative AI. Jarvis is an experienced marketing leader focused on the use of consumer and creative insights, customer data, and emerging platforms to deliver unique brand experiences.

Partner Center

MIT Technology Review

- Newsletters

Industry- and AI-focused cloud transformation

A successful cloud-based business transformation requires solutions with industry-specific best practices and AI readiness built in.

- MIT Technology Review Insights archive page

In association with Oracle and Wipro

For years, cloud technology has demonstrated its ability to cut costs, improve efficiencies, and boost productivity. But today’s organizations are looking to cloud for more than simply operational gains. Faced with an ever-evolving regulatory landscape, a complex business environment, and rapid technological change, organizations are increasingly recognizing cloud’s potential to catalyze business transformation.

Cloud can transform business by making it ready for AI and other emerging technologies. The global consultancy McKinsey projects that a staggering $3 trillion in value could be created by cloud transformations by 2030. Key value drivers range from innovation-driven growth to accelerated product development.

“As applications move to the cloud, more and more opportunities are getting unlocked,” says Vinod Mamtani, vice president and general manager of generative AI services for Oracle Cloud Infrastructure. “For example, the application of AI and generative AI are transforming businesses in deep ways.”

No longer simply a software and infrastructure upgrade, cloud is now a powerful technology capable of accelerating innovation, improving agility, and supporting emerging tools. In order to capitalize on cloud’s competitive advantages, however, businesses must ask for more from their cloud transformations.

Every business operates in its own context, and so a strong cloud solution should have built-in support for industry-specific best practices. And because emerging technology increasingly drives all businesses, an effective cloud platform must be ready for AI and the immense impacts it will have on the way organizations operate and employees work.

An industry-specific approach

The imperative for cloud transformation is evident: In today’s fast-faced business environment, cloud can help organizations enhance innovation, scalability, agility, and speed while simultaneously alleviating the burden on time-strapped IT teams. Yet most organizations have not fully made the leap to cloud. McKinsey, for example, reports a broad mismatch between leading companies’ cloud aspirations and realities —though nearly all organizations say they aspire to run the majority of their applications in the cloud within the decade, the average organization has currently relocated only 15–20% of them.

Cloud solutions that take an industry-specific approach can help companies meet their business needs more easily, making cloud adoption faster, smoother, and more immediately useful. “Cloud requirements can vary significantly across vertical industries due to differences in compliance requirements, data sensitivity, scalability, and specific business objectives,” says Deviprasad Rambhatla, senior vice president and sector head of retail services and transportation at Wipro.

Health-care organizations, for instance, need to manage sensitive patient data while complying with strict regulations such as HIPAA. As a result, cloud solutions for that industry must ensure features such as high availability, disaster recovery capabilities, and continuous access to critical patient information.

Retailers, on the other hand, are more likely to experience seasonal business fluctuations, requiring cloud solutions that allow for greater flexibility. “Cloud solutions allow retailers to scale infrastructure on an up-and-down basis,” says Rambhatla. “Moreover, they’re able to do it on demand, ensuring optimal performance and cost efficiency.”

Cloud-based applications can also be tailored to meet the precise requirements of a particular industry. For retailers, these might include analytics tools that ingest vast volumes of data and generate insights that help the business better understand consumer behavior and anticipate market trends.

Download the full report .

It’s time to retire the term “user”

The proliferation of AI means we need a new word.

- Taylor Majewski archive page

Modernizing data with strategic purpose

Data strategies and modernization initiatives misaligned with the overall business strategy—or too narrowly focused on AI—leave substantial business value on the table.

Why it’s so hard for China’s chip industry to become self-sufficient

Chip companies from the US and China are developing new materials to reduce reliance on a Japanese monopoly. It won’t be easy.

- Zeyi Yang archive page

Almost every Chinese keyboard app has a security flaw that reveals what users type

An encryption loophole in these apps leaves nearly a billion people vulnerable to eavesdropping.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from mit technology review.

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.

Thank you for submitting your email!

It looks like something went wrong.

We’re having trouble saving your preferences. Try refreshing this page and updating them one more time. If you continue to get this message, reach out to us at [email protected] with a list of newsletters you’d like to receive.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, the future is now: integrating artificial intelligence (ai) into business models.

Development and Learning in Organizations

ISSN : 1477-7282

Article publication date: 3 June 2024

This paper aims to review the latest management developments across the globe and pinpoint practical implications from cutting-edge research and case studies.

Design/methodology/approach

This briefing is prepared by an independent writer who adds their own impartial comments and places the articles in context.

This paper identified that the use of artificial intelligence (AI) can improve business processes to promote efficiency and performance.

Originality/value

The briefing saves busy executives, strategists and researchers hours of reading time by selecting only the very best, most pertinent information and presenting it in a condensed and easy-to-digest format.

- Artificial intelligence

- Business performance

- Digital transformation

(2024), "The future is now: Integrating artificial intelligence (AI) into business models", Development and Learning in Organizations , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLO-05-2024-0123

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2024, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

More From Forbes

Innovative sales models that propel business growth across industries.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Learn how subscription services and other innovative sales models can transform your business, ... [+] tackle market challenges, and engage customers.

The corporate world is evolving, and with it, so are the strategies businesses use to drive growth and profitability. As businesses across various sectors strive to adapt to changing market demands and boost customer engagement, they are increasingly exploring diverse and innovative sales models.

Whether in technology, real estate, or retail, adapting your sales strategy can enhance scalability and significantly increase your bottom line. These strategies are pivotal in driving growth, from subscription services that ensure revenue predictability to customized sales approaches informed by direct customer feedback. Each model offers unique advantages for improved operational efficiency and deeper relational ties with customers.

Integrating loyalty and pricing for customer value

In today's economy, where inflation and recession concerns prompt consumers to tighten their belts, merging loyalty programs with pricing strategies is a strategic move for businesses focused on adding value and spurring growth. This approach is especially effective as it directly responds to the growing consumer demand for more value-driven spending options.

Companies can significantly deepen customer engagement by synchronizing loyalty incentives with pricing adjustments. For example, providing exclusive discounts to loyalty members clarifies membership benefits and encourages broader participation. This strategy can lead to increased purchase frequency and deeper customer loyalty.

However, implementing such integrated strategies requires analytics and cross-departmental collaboration. Advanced levels of integration might include personalized pricing offers that encourage customers to ascend to higher tiers of loyalty programs, which boosts their lifetime value to the company. This strategic blend of pricing and loyalty is designed not just to meet immediate consumer needs but to foster long-lasting relationships.

Samsung Documents Confirm Missing Galaxy Z Fold 6 Feature

World no. 1 djokovic survives 5-set epic to advance in french open match that ends after 3 am, apple insider details an expensive iphone pro decision.