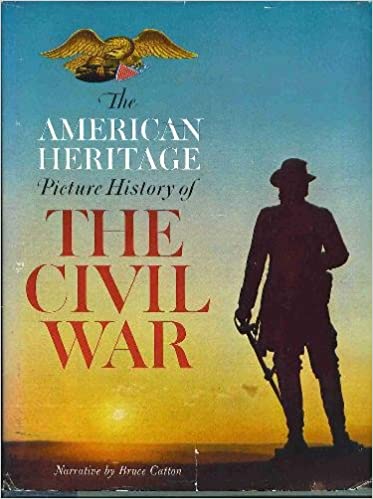

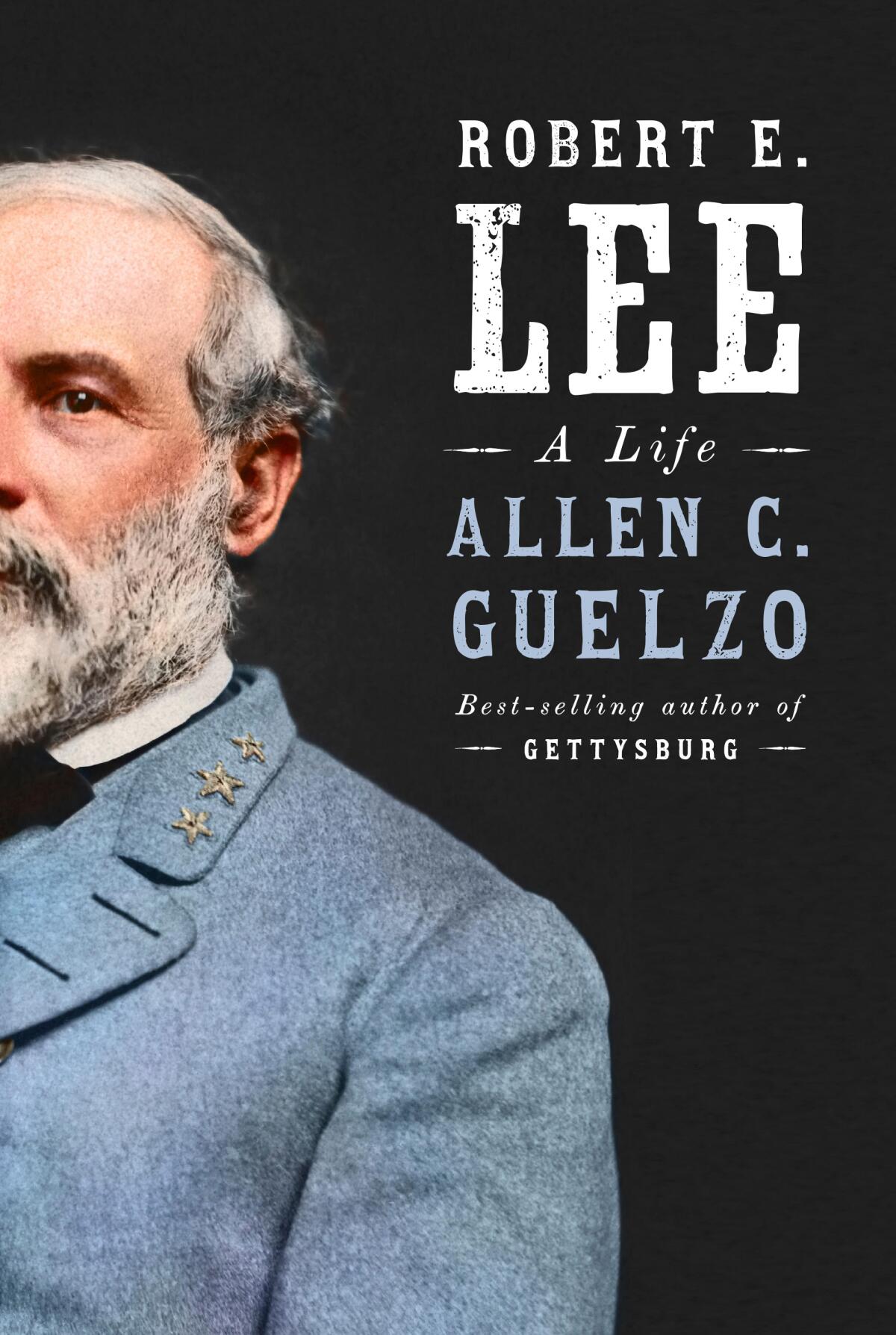

Best Books About Robert E. Lee

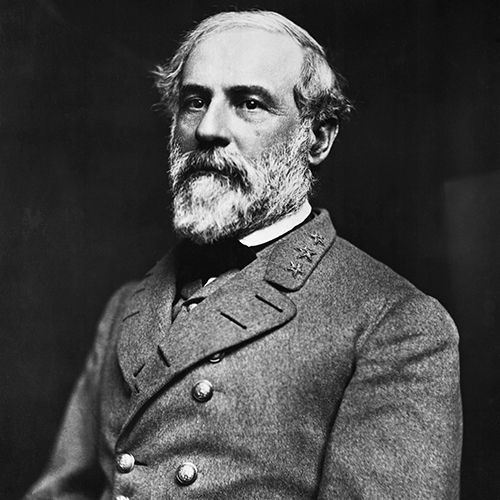

Robert E. Lee is an iconic and controversial figure which countless books have been written about since days of the Civil War .

To help you figure out which books to read, I’ve created this list of the best books about Robert E. Lee.

I’ve also used many of these books in my research for this website so I can personally say they are some of the best on the topic.

The following is a list of the best books about Robert E. Lee:

(Disclaimer: This article contains Amazon affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

The book discusses everything from Lee’s experiences in the Mexican-War to his surrender at Appomattox. Freeman depicts Lee as an honest, straightforward man who is “one of the small company of great men in whom there is no inconsistency to be explained, no enigma to be solved.”

The book received positive reviews when it was published. The New York Times referred to the entire work as “Lee Complete for All Time” while Stephen Vincent Benet’s review in the New York Herald Tribune referred to it as a “a complete portrait – solid, vivid, authoritative, and compelling.”

In addition to his biography about Lee, Freeman also wrote a highly acclaimed six-volume biography of George Washington.

Thomas argues that Lee’s image has been distorted over the years partly due to his own hidden nature and partly due to the myths and legends that surround him.

“Lee, the enigma, seldom if ever revealed himself while he lived. To understand him, it is necessary to look behind his words and see, for example, the true nature of the lighthouse keeper Lee encountered during his surveying mission in 1835. It is also important to peer beyond Lee’s words and recall what he did as well as what he said. Sometimes the existential Lee contradicted the verbal Lee.”

“In addition to looking behind and beyond his words, it is well to remember that Lee once possessed of flesh and blood. This is important because so many have made so much of Lee during the years since he lived that legend, image and myth have supplanted reality. Lee has become a hero essentially smaller than life.”

The book received positive reviews when it was published. A review in Publisher’s Weekly “highly recommended” the book due to its unique take on this iconic figure:

“Synthesizing printed and manuscript sources, he presents Lee as neither the icon of Douglas Southall Freeman nor the flawed figure presented by Thomas Connolly. Lee emerges instead as a man of paradoxes, whose frustrations and tribulations were the basis for his heroism. Lee’s work was his play, according to the author, and throughout his life he made the best of his lot…Highly recommended.”

A review by Kirkus Reviews praised the book for presenting a fair and balanced view of this controversial figure:

“A comprehensive new biography that seeks to give a balanced portrait of the famed Confederate general. Thomas undertakes a daunting task here, seeking to recover the real, living human from the mythology surrounding Lee since his death in 1870. In this effort he hews a middle ground between early 20th century hagiographies and revisionist contemporary interpretations…Well written and based largely on primary documentation, a good effort at understanding a complex personality.”

A review by Patrick T. Reardon in the Chicago Tribune called the book an “interesting, readable examination of Lee’s life” but states that it “leaves the general still very much a mystery.”

A review in the New York Review of Books called it “The best and most balanced of the Lee biographies.”

Thomas is also the author of eight books about the Civil War era, which include The Confederate Nation: 1861-1865; The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience; Travels to Hallowed Ground: A Historian’s Journey to the American Civil War; Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart; The Confederate State of Richmond: A Biography of the Capital; The Dogs of War: 1861; The American War and Peace: 1860-1877.

3. Recollections and Letters of Robert E. Lee by Captain Robert Edward Lee

Captain Robert E. Lee was the youngest of General Lee’s three sons. In 1862, Lee served as a private in the Rockbridge Artillery before he was promoted to the rank of Captain, after the Battle of Sharpsburg, and then promoted to major general and aide-de-camp to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

The book attempts to dispel the myths surrounding Lee to reveal the true human being underneath. In the book, Korda describes Lee as a serious, hard-working military man with a surprisingly fun side:

“A perfectionist, obsessed by duty and by the value of obedience, he might have been a grim figure, except for the fact that he had another side, charming, funny, and flirtatious. The animal lover, the gifted watercolorist, the talented cartographer – the topographic maps he drew for the Corps of Engineers are works of art, as are the cartoons he drew for his children in Mexico. The father who adored having his children get into bed with him in the morning, and telling them stories, or having them tickle his feet; the adoring husband; the devoted friend – these are all facets of the same man. He was the product of a rationalist education and at the same time a romantic, who sought for a spiritual answer to the problems of life – a man of contradictions, whose natural good manners and courtly bearing disguised his lifelong soul-searching.”

The book received positive reviews when it was published. A review by David Shribman in the Boston Globe described it as “Lively, approachable, and captivating…Like Lee himself, everything about Clouds of Glory is on a grand scale” while Publisher’s Weekly referred to it as “superbly engaging.”

Kirkus Reviews called it “A masterful biography of the beloved Civil War general…Lee is a man for the ages, and Korda delivers the goods with this heart-wrenching story of the man and his state” and a review by David Holahan in the Christian Science Monitor stated “Korda clearly has command of his subject…[Clouds of Glory] is well-considered and amply documented. Military buffs will find much to feast on.”

Yet, other reviewers were a little more reserved in their praise. Historian Eric Foner reviewed the book for the Washington Post and took issue with Korda’s grasp of the broader issues of the Civil War and Lee’s attitude towards them:

“When it comes to the broader historical context, Korda sometimes falters. He does not display familiarity with recent literature on the Civil War era. For example, the one book he cites on desertion from the Confederate armies, a subject of considerable recent scholarship, was written in 1924. Korda notes that Lee’s views on slavery and race have too often been ‘swept under the rug,’ but his own discussion is scattered and incomplete…Although Korda describes him as a political moderate, there was nothing moderate in Lee’s stance during the 1860 presidential campaign… Toward the end of the Civil War, Lee came to accept the necessity of enlisting black soldiers in the Confederate armies; a handful were enrolled a month before the surrender at Appomattox. Yet, Korda notes, his racial views ‘never changed.’ Unfortunately, the book fails to devote sufficient attention to Lee’s appearance in 1866 before the congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction, which showed him at his worst.”

5. The Man Who Would Not Be Washington by Jonathan Horn

Published in 2015, this book by Jonathan Horn is about Lee’s complicated connection to George Washington.

“The connections between Washington and Lee are neither mystic nor manufactured. Lee was not the second coming of Washington, but he might have been had he chosen differently. As Washington was the man who would not be king, Lee was the man who would not be Washington. The story that emerges when viewed in this light is more complicated, more tragic, and more illuminating.”

The book received positive reviews when it was published. A review by USA Today called it compelling:

“Compelling….a modern and readable perspective on Lee’s enigmatic character” while the Pittsburg Post Gazette declared “The resulting work is well-written, fair-minded and short.”

“Horn, a former White House speechwriter, puts a captivating spin on Lee’s story by comparing and contrasting the two great men. Detailed yet accessible descriptions of battles are coupled with stories of Lee’s personal life, revealing a man as complex as the war he reluctantly joined…Horn takes a fair and equitable approach to Lee, his life, and his struggle over participation in a war that tore apart the nation.”

“A romantic, rueful portrait of the Confederate general and the fatal decision that shut him out of history. Former White House speechwriter Horn finds Robert E. Lee (1807-1870) a deeply sympathetic American hero whom fortune seemed to have favored as heir to George Washington, if only Lee had thrown his lot with the Union rather than the South…Compelling research within an overwrought presentation.”

A review in the Kent State University Press also praised the book’s research:

“By design, Horn’s book is a limited biography of Lee. Whole chapters of Lee’s life, for example his engineering work on the Mississippi, receive only a sentence or two. But his central point, the Washington-Lee dynamic, is well researched and thoroughly developed. Whether Horn has made his case convincingly is for each reader to decide.”

Jonathan Horn is a former speechwriter for George W. Bush and journalist whose writing has appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times and the Weekly Standard. The Man Who Would Not Be Washington is Horn’s first book.

Davis explains in the book’s preface that the work is not a traditional biography that chronicles the timeline of their lives but instead follows their personal development as military leaders:

“This is not a conventional biography. It is, rather, an exploration of the origins and development of Grant’s and Lee’s personalities and characters, their ethical and moral compasses, and their thinking processes and approaches to decision making – in short, the things that made them the kind of commanders they became.”

Yet, Davis goes on to explain that the book still has new information and insight from newly discovered and previously ignored sources, especially on Lee and Grant’s youth.

A review by Kirkus Reviews called it “A fresh look at the sources and a careful eye to leadership and character places this book high atop the list of recent Civil War histories.”

7. Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters by Elizabeth Brown Pryor

In the book’s preface, Pryor explains that the book is not meant to be a full-scale biography but is instead a behind the scenes glimpse at Lee through his own words;

“Although this book is filled with new material, it is not meant to be a sensationalist biography. Nor is it a cradle-to-grave chronology, a detailed description of military movements, or an exhaustive analysis of the Civil War. Those books have already been written. Debunking the Lee mythology is also not the point of this book. Rather, it is to amplify our understanding of what constitutes heroism, and how as an ordinary person Lee faced the vagaries of the human condition. These letters help us to understand his prominence and to move out of our own moment to connect with a larger collective experience.”

The book received positive reviews when it was published. Historian David Blight reviewed it for the Boston Globe and praised its unique take on this controversial figure:

“An unorthodox, critical, and engaging biography. . . . [Pryor] impressively captures Lee’s character and personality.”

A review by Fergus M. Bordewich in the Wall Street Journal also praised the book for capturing Lee’s complexity:

“Pryor has taken an icon and given us the soul of a complex man and his turbulent age.”

Fellow Lee biographer, William C. Davis, wrote in the preface to his own book, Crucible of Command , that Pryor’s book is well-researched although he faulted her for occasionally making unwarranted assumptions:

“Elizabeth Pryor’s 2007 Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters is exhaustively researched and in the main an outstanding exploration of the inner Lee, often through writings not previously available, though she sometimes makes unwarranted leaps of interpretation from her sources.”

Elizabeth Brown Pryor, who died unexpectedly in an accident in 2015, was a former U.S. Diplomat who worked for the Department of State. Pryor is also the author of Clara Barton: Professional Angel and Six Encounters With Lincoln: A President Confronts Democracy and Its Demons, which was published posthumously in 2017.

Published in 1894, this book by Fitzhugh Lee, Robert’s E. Lee’s nephew, chronicles Lee’s life using his unpublished private letters.

The book briefly discusses Lee’s family history before delving deep into the events of his military career. Fitzhugh Lee explains, in the book’s preface, that since General Lee never wrote a memoir, this book is an attempt to tell Lee’s story through his own words:

“In this volume the attempt has been made to imperfectly supply the great desire to have something from Robert E. Lee’s pen, by introducing, at the periods referred to, such extracts from his private letters as would be of general interest. He is thus made, for the first time, to give his impressions and opinions on most of the great events with which he was so closely connected.”

Fitzhugh Lee was a general in the U.S. army during the Spanish-American war and a cavalry general for the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War.

Published in 1991, this book by Alan T. Nolan debunks the myths and legends about Lee to set the record straight about this iconic figure.

“This book is not, therefore, a biography and offers no full account of Robert E. Lee’s life. It is, instead, an examination of major aspects of the tradition that identifies Lee in American history. In raising questions and drawing conclusions about this tradition, I have attempted to set fort the evidence. The reader who thinks I am asking the wrong questions or disagrees with my conclusions may, in evaluating my thesis, consider the evidence on which it is based. This evidence does not include any new or sensational facts or new primary materials. On the contrary, my inquiry concerns what the familiar and long-available evidence actually establishes about Robert E. Lee. The results of my inquiry are not so much an expose as simply an attempt to set the record straight.”

“However, any future author dealing with Lee will have to face up to Nolan’s material and we will all be the better for it. A man struggling with his times, his prejudices and his sense of honor makes a more arresting subject than a public figure who forever seems to be speaking in copybook maxims.”

Yet, historian James McPherson reviewed the book for the New York Review of Books and accused Nolan of being disingenuous in his claim that the book was not intended to defame Lee:

“But this disclaimer of bias is a bit disingenuous. Nolan is a lawyer by profession. The book has something of the tone of an indictment of Lee in the court of history, with the author as prosecuting attorney. He wants the jury—his readers—to convict Lee of entering willingly into a war to destroy the American nation.”

“There is truth in some of these charges; it is not the whole truth, however. Nolan’s portrait of Lee may be closer to the real Lee than the flawless marble image promoted by tradition. But the prosecutorial style of his book produces some new distortions.”

Alan T. Nolan is a former lawyer and author of numerous books about the Civil War, including The Iron Brigade: A Military History; Giants in Their Tall Hats: Essays on the Iron Brigade; Rally, Once Again!: Selected Civil War Writings.

10. Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society by Thomas Lawrence Connelly

“This book is an attempt to probe the image of Robert E. Lee in the American mind, from its origins among Lost Cause writers in the Reconstruction years to the era of the 1961-65 Civil War Centennial, when Lee became a hero to white middle class America. I am also endeavoring to test the Lee image for possible distortion and to rep-praise Lee himself as well. While there have been many biographies of Robert E. Lee, no one has seriously explored the process by which his image has developed since the Civil War.”

Connelly goes on to explain that Lee’s image has become distorted over the years and as a result the real Lee has been obscured:

“In truth, Lee was an extremely complex individual. Lee the man has become so intermingled with Lee the hero symbol that the real person has been obscured. Efforts to understand him, and to appraise his capabilities fairly, have been hindered by his image as a folk hero.”

The book was the first to deconstruct the myth of Robert E. Lee and was considered groundbreaking and controversial when it was published.

A review by the now defunct Saturday Review of Literature called it fascinating:

“Connelly provides a fascinating insight into the historical press-agentry through which Lee was enshrined as…an exemplar of American virtues.”

“Connelly conveys these themes with a professionalism that will enable readers to discriminate among his views of Lee, earlier commentators’, and his view of the latter; what could have been a merely useful compilation of propaganda is transformed by Connelly’s own evaluations into a highly substantive and challenging work.”

“Through exhaustive research, Connelly effectively illustrates the Lee image which emerged from newspaper, popular and scholarly magazine, manuscript, fictional, oral, radio, and poetic accounts of the General. Shortcomings of The Marble Man are the attempts to discover why the image developed and then to compare it with the real person, Robert E. Lee.”

Thomas Lawrence Connelly, who died in 1991, was a professor of history at the University of South Carolina. Connelly wrote numerous books about the Civil War, including The Politics of Command: Factions and Ideas in Confederate Strategy; Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee, 1862-1865; Army of Heartland: The Army of Tennessee, 1861-1862; Civil War Tennessee: Battles and Leaders; God and General Longstreet: The Lost Cause and the Southern Mind.

Sources: Wilkinson, Julie. “The Marble Man: Robert E. Lee and His Image in American Society.” The Annals of Iowa, State Historical Society of Iowa, vol. 44, no. 5, summer 1978, pps. 408-408, ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=8568&context=annals-of-iowa Carmichael, Peter S. “CWT Book Review: Lee Considered.” History.net, 16 March. 2018, www.historynet.com/cwt-book-review-lee-considered.htm Andrews, Peter. “Book World – Lee Considered.” Washington Post, 8 July. 1991, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1991/07/08/book-world/7e9be165-279d-4973-81e6-4643d21b16cb/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.f56cb4917a8e McPherson, James. “How Noble Was Robert E. Lee.” New York Review of Books, 7 Nov. 1991, www.nybooks.com/articles/1991/11/07/how-noble-was-robert-e-lee/ Faust, Drew Gilpin. “Lee Without Tears.” New York Times, 7 July. 1991, www.nytimes.com/1991/07/07/books/lee-without-tears.html Bordewich, Fergus M. “Discovering the Real Robert E. Lee.” Wall Street Journal, 15 May. 2007, www.wsj.com/articles/SB117918601842902577 Blight, David. “In a Celebrated Life, Shades of Gray.” Boston Globe, 29 July. 2007, archive.boston.com/ae/books/articles/2007/07/29/in_a_celebrated_life_shades_of_gray/ Barney, William L.”Crucible of Command: Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee—The War They Fought, the Peace They Forged by William C. Davis (review).” Journal of Southern History , vol. 82 no. 1, 2016, pp. 176-177. Project MUSE , muse.jhu.edu/article/611092/pdf Wert, Jeffry D. “Davis: Crucible of Command (2015).” Civil War Monitor, 12 Aug. 2015, www.civilwarmonitor.com/book-shelf/davis-crucible-of-command-2015 “Review: Crucible of Command.” Bob On Books, 25 May. 2015, bobonbooks.com/2015/05/25/review-crucible-of-command/ Barra, Allen. “Book Review: Crucible of Command – Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee.” Historynet.com, 9 Dec. 2014, www.historynet.com/book-review-crucible-of-command-ulysses-s-grant-and-robert-e-lee.htm “Crucible of Command by William C. Davis.” Kirkus Reviews, 21 Dec. 2014, www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/william-c-davis/crucible-of-command/ Goulden, Joseph C. “The Civil War and the Generals Who Fought It.” Washington Times, 20 April. 2015, www.washingtontimes.com/news/2015/apr/20/book-review-crucible-of-command-ulysses-s-grand-an/ Bonds, Russell S. “The Odd Couple.” Wall Street Journal, 6 March. 2015, www.wsj.com/articles/book-review-crucible-of-command-by-william-c-davis-1425677492 Carrigan, Henry L., Jr. “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington by Jonathan Horn.” BookPage, bookpage.com/reviews/17608-jonathan-horn-man-who-would-not-be-washington-history Dotinga, Randy. “Robert E. Lee and George Washington Do Not Equate, Says Lee Biographer Jonathan Horn.” Christian Science Monitor, 7 Sept. 2017, www.csmonitor.com/Books/chapter-and-verse/2017/0907/Robert-E.-Lee-and-George-Washington-do-not-equate-says-Lee-biographer-Jonathan-Horn Barcousky, Len. “’The Man Who Would Not Be Washington’: Robert E. Lee embraces Virginia at the expense of the country he loved.” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, 1 March. 2015, www.post-gazette.com/ae/books/2015/03/01/The-Man-Who-Would-Not-Be-Washington-Robert-E-Lee-embraces-Virginia-at-the-expense-of-the-country-he-loved/stories/201503010062 “Nonfiction Book Review: The Man Who Would Not Be Washington by Jonathan Hom.” Publisher’s Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-4767-4856-6 “The Man Who Would Not Be Washington by Jonathan Hom.” Kirkus Reviews, 2 Nov. 2014, www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/jonathan-horn/the-man-who-would-not-be-washington/ Bailey, Greg. “ The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War and His Decision That Changed American History by Jonathan Horn (review).” Civil War History , vol. 61 no. 4, 2015, pp. 455-456. Project MUSE , muse.jhu.edu/article/597689 Holahan, David. “Clouds of Glory.” Christian Science Monitor, 12 May. 2014, www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2014/0512/Clouds-of-Glory “Clouds of Glory by Michael Korda.” Kirkus Reviews, 30 March. 2014, www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/michael-korda/clouds-of-glory-life/ “Nonfiction Book Review: Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee by Michael Korda.” Publisher’s Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-06-211629-1 Shribman, David. “’Clouds of Glory’ by Michael Korda.” Boston Globe, 17 May. 2014, www.bostonglobe.com/arts/books/2014/05/17/review-clouds-glory-michael-korda/hs2q7pt1kaZSBBEoXs212K/story.html Foner, Eric. “Book Review: ‘Clouds of Glory: the Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee’ by Michael Korda.” Washington Post, 30 May. 2014, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/book-review-clouds-of-glory-the-life-and-legend-of-robert-e-lee-by-michael-korda/2014/05/30/cba1d004-c973-11e3-95f7-7ecdde72d2ea_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.20ee0c7f1ea7 Bordewiche, Fergus M. “Ghost of the Confederacy.” New York Times, 27 June. 2014, www.nytimes.com/2014/06/29/books/review/clouds-of-glory-michael-kordas-robert-e-lee-biography.html Rable, George C. “The Journal of Southern History.” The Journal of Southern History , vol. 62, no. 4, 1996, pp. 809–811. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/2211160. Reardon, Patrick. “Emory Thomas Paints a 3 rd View of Enigmatic Robert E. Lee.” Chicago Tribune, 10 Sept. 1995, www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1995-09-10-9509100037-story.html “Robert E. Lee by Emory M. Thomas.” Kirkus Review, www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/emory-m-thomas/robert-e-lee/ “Nonfiction Book Review: Robert E. Lee: A Biography.” Publisher’s Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-393-03730-2 Thompson, Charles Willis. “Robert E. Lee: A Final Portrait.” New York Times Book Review, 14 Oct. 1934. Thompson, Charles Willis. “Dr. Freeman Concludes his Monumental Life of Lee.” New York Times Book Review, 10 Feb. 1935. Benet, Stephen Vincent. “Great General, Greater Man: Robert E. Lee.” New York Herald Tribune, 10 Feb. 1935. Tate, Allen. “The Definitive Lee.” The New Republic, 19 Dec. 1934. Commager, Henry Steele. “New Books in Review: The Life of Lee.” The Yale Review, vol. XXIV, no. 3 (March 1935), 594. Malone, Dumas. “Review of R.E. Lee.” American Historical Review, vol. XL, no. 3, (April 1935), 534. Malone, Dumas. “Review of R.E. Lee.” American Historical Review, vol. XLI, no. 1, (October 1935), 164. Johnson, David E. Douglas Southall Freeman. Pelican Publishing Company, 2002. “30 Great Books About Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee.” About Great Books, www.aboutgreatbooks.com/topics/history/ulysses-s-grant-robert-e-lee/ Reeves, John. “7 Essential Books on Robert E. Lee.” Medium, 15 Aug. 2017, medium.com/@reevesjw/7-essential-books-on-robert-e-lee-dae455bc7bcf

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Early life and U.S. military service

- Slavery and racial attitudes

- Role in the Civil War

- Postwar life and legacy

What was Robert E. Lee’s family like?

Should statues of robert e. lee be taken down.

- What was the significance of the Battle of Gettysburg?

- What caused the American Civil War?

- Who won the American Civil War?

Robert E. Lee

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- American Battlefield Trust - Biography of Robert E. Lee

- Encyclopedia Virginia - Robert E. Lee

- Virginia Center for Civil War Studies - Robert E. Lee: The Eternal General

- Public Broadcasting Service - American Experience - Biography of General Robert E. Lee

- National Park Service - Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial - Biography of Robert Edward Lee

- HistoryNet - Robert E. Lee

- African American Registry - Robert E. Lee, Confederate General born

- Robert E. Lee - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Robert E. Lee - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

On both sides, Robert E. Lee’s family had produced many of the dominant figures in the ruling class of Virginia . His father, Col. Henry (“Light-Horse Harry”) Lee , had been a cavalry leader during the American Revolution , a post-Revolution governor of Virginia, and the author of a popular congressional memorial eulogy to his friend George Washington .

What was Robert E. Lee’s childhood like?

Robert E. Lee’s father’s financial mismanagement left Lee, his mother, and his siblings in circumstances that rendered them less wealthy than the plantation owners in his extended family.

Why is Robert E. Lee significant?

Robert E. Lee commanded the Army of Northern Virginia, the most successful of the Southern armies during the American Civil War , and ultimately commanded all the Confederate armies. As the military leader of the defeated Confederacy , Lee became a symbol of the American South.

What was Robert E. Lee’s occupation after leaving the military?

Robert E. Lee spent several months recuperating from the Civil War and then, in 1865, became the president of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University ) in Lexington, Virginia. He died in 1870.

Whether statues of Robert E. Lee or other controversial people should be taken down is widely debated. Some argue the statues misrepresent history and are a painful reminder of the past, while other statues would better represent the county. Others argue the statues are part of the country's history that do not cause racism but could educate people, and removal of one statue is a slippery slope to taking down any statue anyone disagrees with. For more on the debate on historical statue removal, visit ProCon.org .

Robert E. Lee (born January 19, 1807, Stratford Hall, Westmoreland county, Virginia , U.S.—died October 12, 1870, Lexington , Virginia) was a U.S. Army officer (1829–61), Confederate general (1861–65), college president (1865–70), and central figure in contending memory traditions of the American Civil War .

The Civil War

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Making Sense of Robert E. Lee

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”— Robert E. Lee, at Fredericksburg

Roy Blount, Jr.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/lee_father.jpg)

Few figures in American history are more divisive, contradictory or elusive than Robert E. Lee, the reluctant, tragic leader of the Confederate Army, who died in his beloved Virginia at age 63 in 1870, five years after the end of the Civil War. In a new biography, Robert E. Lee , Roy Blount, Jr., treats Lee as a man of competing impulses, a “paragon of manliness” and “one of the greatest military commanders in history,” who was nonetheless “not good at telling men what to do.”

Blount, a noted humorist, journalist, playwright and raconteur, is the author or coauthor of 15 previous books and the editor of Roy Blount’s Book of Southern Humor . A resident of New York City and western Massachusetts, he traces his interest in Lee to his boyhood in Georgia. Though Blount was never a Civil War buff, he says “every Southerner has to make his peace with that War. I plunged back into it for this book, and am relieved to have emerged alive.”

“Also,” he says, “Lee reminds me in some ways of my father.”

At the heart of Lee’s story is one of the monumental choices in American history: revered for his honor, Lee resigned his U.S. Army commission to defend Virginia and fight for the Confederacy, on the side of slavery. “The decision was honorable by his standards of honor—which, whatever we may think of them, were neither self-serving nor complicated,” Blount says. Lee “thought it was a bad idea for Virginia to secede, and God knows he was right, but secession had been more or less democratically decided upon.” Lee’s family held slaves, and he himself was at best ambiguous on the subject, leading some of his defenders over the years to discount slavery’s significance in assessments of his character. Blount argues that the issue does matter: “To me it’s slavery, much more than secession as such, that casts a shadow over Lee’s honorableness.”

In the excerpt that follows, the general masses his troops for a battle over three humid July days in a Pennsylvania town. Its name would thereafter resound with courage, casualties and miscalculation: Gettysburg.

In his dashing (if sometimes depressive) antebellum prime, he may have been the most beautiful person in America, a sort of precursorcross between Cary Grant and Randolph Scott. He was in his element gossiping with belles about their beaux at balls. In theaters of grinding, hellish human carnage he kept a pet hen for company. He had tiny feet that he loved his children to tickle None of these things seems to fit, for if ever there was a grave American icon, it is Robert Edward Lee—hero of the Confederacy in the Civil War and a symbol of nobility to some, of slavery to others.

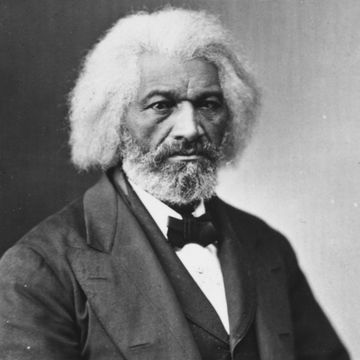

After Lee’s death in 1870, Frederick Douglass, the former fugitive slave who had become the nation’s most prominent African-American, wrote, “We can scarcely take up a newspaper . . . that is not filled with nauseating flatteries” of Lee, from which “it would seem . . . that the soldier who kills the most men in battle, even in a bad cause, is the greatest Christian, and entitled to the highest place in heaven.” Two years later one of Lee’s ex-generals, Jubal A. Early, apotheosized his late commander as follows: “Our beloved Chief stands, like some lofty column which rears its head among the highest, in grandeur, simple, pure and sublime.”

In 1907, on the 100th anniversary of Lee’s birth, President Theodore Roosevelt expressed mainstream American sentiment, praising Lee’s “extraordinary skill as a General, his dauntless courage and high leadership,” adding, “He stood that hardest of all strains, the strain of bearing himself well through the gray evening of failure; and therefore out of what seemed failure he helped to build the wonderful and mighty triumph of our national life, in which all his countrymen, north and south, share.”

We may think we know Lee because we have a mental image: gray. Not only the uniform, the mythic horse, the hair and beard, but the resignation with which he accepted dreary burdens that offered “neither pleasure nor advantage”: in particular, the Confederacy, a cause of which he took a dim view until he went to war for it. He did not see right and wrong in tones of gray, and yet his moralizing could generate a fog, as in a letter from the front to his invalid wife: “You must endeavour to enjoy the pleasure of doing good. That is all that makes life valuable.” All right. But then he adds: “When I measure my own by that standard I am filled with confusion and despair.”

His own hand probably never drew human blood nor fired a shot in anger, and his only Civil War wound was a faint scratch on the cheek from a sharpshooter’s bullet, but many thousands of men died quite horribly in battles where he was the dominant spirit, and most of the casualties were on the other side. If we take as a given Lee’s granitic conviction that everything is God’s will, however, he was born to lose.

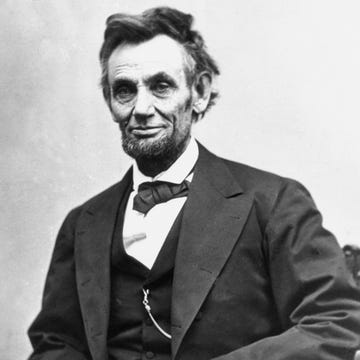

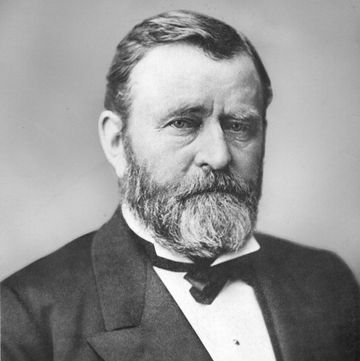

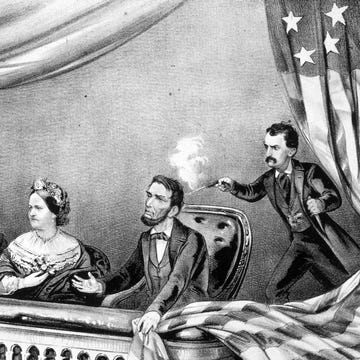

As battlefield generals go, he could be extremely fiery, and could go out of his way to be kind. But in even the most sympathetic versions of his life story he comes across as a bit of a stick—certainly compared with his scruffy nemesis, Ulysses S. Grant; his zany, ferocious “right arm,” Stonewall Jackson; and the dashing “eyes” of his army, J.E.B. “Jeb” Stuart. For these men, the Civil War was just the ticket. Lee, however, has come down in history as too fine for the bloodbath of 1861-65. To efface the squalor and horror of the war, we have the image of Abraham Lincoln freeing the slaves, and we have the image of Robert E. Lee’s gracious surrender. Still, for many contemporary Americans, Lee is at best the moral equivalent of Hitler’s brilliant field marshal Erwin Rommel (who, however, turned against Hitler, as Lee never did against Jefferson Davis, who, to be sure, was no Hitler).

On his father’s side, Lee’s family was among Virginia’s and therefore the nation’s most distinguished. Henry, the scion who was to become known in the Revolutionary War as Light-Horse Harry, was born in 1756. He graduated from Princeton at 19 and joined the Continental Army at 20 as a captain of dragoons, and he rose in rank and independence to command Lee’s light cavalry and then Lee’s legion of cavalry and infantry. Without the medicines, elixirs, and food Harry Lee’s raiders captured from the enemy, George Washington’s army would not likely have survived the harrowing winter encampment of 1777-78 at Valley Forge. Washington became his patron and close friend. With the war nearly over, however, Harry decided he was underappreciated, so he impulsively resigned from the army. In 1785, he was elected to the Continental Congress, and in 1791 he was elected governor of Virginia. In 1794 Washington put him in command of the troops that bloodlessly put down the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania. In 1799 he was elected to the U.S. Congress, where he famously eulogized Washington as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Meanwhile, though, Harry’s fast and loose speculation in hundreds of thousands of the new nation’s acres went sour, and in 1808 he was reduced to chicanery. He and his second wife, Ann Hill Carter Lee, and their children departed the Lee ancestral home, where Robert was born, for a smaller rented house in Alexandria. Under the conditions of bankruptcy that obtained in those days, Harry was still liable for his debts. He jumped a personal appearance bail—to the dismay of his brother, Edmund, who had posted a sizable bond—and wangled passage, with pitying help from President James Monroe, to the West Indies. In 1818, after five years away, Harry headed home to die, but got only as far as Cumberland Island, Georgia, where he was buried. Robert was 11.

Robert appears to have been too fine for his childhood, for his education, for his profession, for his marriage, and for the Confederacy. Not according to him. According to him, he was not fine enough. For all his audacity on the battlefield, he accepted rather passively one raw deal after another, bending over backward for everyone from Jefferson Davis to James McNeill Whistler’s mother. (When he was superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, Lee acquiesced to Mrs. Whistler’s request on behalf of her cadet son, who was eventually dismissed in 1854.)

By what can we know of him? The works of a general are battles, campaigns and usually memoirs. The engagements of the Civil War shape up more as bloody muddles than as commanders’ chess games. For a long time during the war, “Old Bobbie Lee,” as he was referred to worshipfully by his troops and nervously by the foe, had the greatly superior Union forces spooked, but a century and a third of analysis and counteranalysis has resulted in no core consensus as to the genius or the folly of his generalship. And he wrote no memoir. He wrote personal letters—a discordant mix of flirtation, joshing, lyrical touches, and stern religious adjuration—and he wrote official dispatches that are so impersonal and (generally) unselfserving as to seem above the fray.

During the postbellum century, when Americans North and South decided to embrace R. E. Lee as a national as well as a Southern hero, he was generally described as antislavery. This assumption rests not on any public position he took but on a passage in an 1856 letter to his wife. The passage begins: “In this enlightened age, there are few I believe, but what will acknowledge, that slavery as an institution, is a moral & political evil in any Country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages.” But he goes on: “I think it however a greater evil to the white than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.”

The only way to get inside Lee, perhaps, is by edging fractally around the record of his life to find spots where he comes through; by holding up next to him some of the fully realized characters—Grant, Jackson, Stuart, Light-Horse Harry Lee, John Brown—with whom he interacted; and by subjecting to contemporary skepticism certain concepts—honor, “gradual emancipation,” divine will—upon which he unreflectively founded his identity.

He wasn’t always gray. Until war aged him dramatically, his sharp dark brown eyes were complemented by black hair (“ebon and abundant,” as his doting biographer Douglas Southall Freeman puts it, “with a wave that a woman might have envied”), a robust black mustache, a strong full mouth and chin unobscured by any beard, and dark mercurial brows. He was not one to hide his looks under a bushel. His heart, on the other hand . . . “The heart, he kept locked away,” as Stephen Vincent Benét proclaimed in “John Brown’s Body,” “from all the picklocks of biographers.” Accounts by people who knew him give the impression that no one knew his whole heart, even before it was broken by the war. Perhaps it broke many years before the war. “You know she is like her papa, always wanting something,” he wrote about one of his daughters. The great Southern diarist of his day, Mary Chesnut, tells us that when a lady teased him about his ambitions, he “remonstrated—said his tastes were of the simplest. He only wanted a Virginia farm—no end of cream and fresh butter—and fried chicken. Not one fried chicken or two—but unlimited fried chicken.” Just before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, one of his nephews found him in the field, “very grave and tired,” carrying around a fried chicken leg wrapped in a piece of bread, which a Virginia countrywoman had pressed upon him but for which he couldn’t muster any hunger.

One thing that clearly drove him was devotion to his home state. “If Virginia stands by the old Union,” Lee told a friend, “so will I. But if she secedes (though I do not believe in secession as a constitutional right, nor that there is sufficient cause for revolution), then I will follow my native State with my sword, and, if need be, with my life.”

The North took secession as an act of aggression, to be countered accordingly. When Lincoln called on the loyal states for troops to invade the South, Southerners could see the issue as defense not of slavery but of homeland. A Virginia convention that had voted 2 to 1 against secession, now voted 2 to 1 in favor.

When Lee read the news that Virginia had joined the Confederacy, he said to his wife, “Well, Mary, the question is settled,” and resigned the U.S. Army commission he had held for 32 years.

The days of July 1-3, 1863, still stand among the most horrific and formative in American history. Lincoln had given up on Joe Hooker, put Maj. Gen. George G. Meade in command of the Army of the Potomac, and sent him to stop Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania. Since Jeb Stuart’s scouting operation had been uncharacteristically out of touch, Lee wasn’t sure where Meade’s army was. Lee had actually advanced farther north than the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, when he learned that Meade was south of him, threatening his supply lines. So Lee swung back in that direction. On June 30 a Confederate brigade, pursuing the report that there were shoes to be had in Gettysburg, ran into Federal cavalry west of town, and withdrew. On July 1 a larger Confederate force returned, engaged Meade’s advance force, and pushed it back through the town—to the fishhook-shaped heights comprising Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, Little Round Top, and Round Top. It was almost a rout, until Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard, to whom Lee as West Point superintendent had been kind when Howard was an unpopular cadet, and Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock rallied the Federals and held the high ground. Excellent ground to defend from. That evening Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who commanded the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, urged Lee not to attack, but to swing around to the south, get between Meade and Washington, and find a strategically even better defensive position, against which the Federals might feel obliged to mount one of those frontal assaults that virtually always lost in this war. Still not having heard from Stuart, Lee felt he might have numerical superiority for once. “No,” he said, “the enemy is there, and I am going to attack him there.”

The next morning, Lee set in motion a two-part offensive: Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s corps was to pin down the enemy’s right flank, on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, while Longstreet’s, with a couple of extra divisions, would hit the left flank—believed to be exposed—on Cemetery Ridge. To get there Longstreet would have to make a long march under cover. Longstreet mounted a sulky objection, but Lee was adamant. And wrong.

Lee didn’t know that in the night Meade had managed by forced marches to concentrate nearly his entire army at Lee’s front, and had deployed it skillfully—his left flank was now extended to Little Round Top, nearly three-quarters of a mile south of where Lee thought it was. The disgruntled Longstreet, never one to rush into anything, and confused to find the left flank farther left than expected, didn’t begin his assault until 3:30 that afternoon. It nearly prevailed anyway, but at last was beaten gorily back. Although the two-pronged offensive was ill-coordinated, and the Federal artillery had knocked out the Confederate guns to the north before Ewell attacked, Ewell’s infantry came tantalizingly close to taking Cemetery Hill, but a counterattack forced them to retreat.

On the third morning, July 3, Lee’s plan was roughly the same, but Meade seized the initiative by pushing forward on his right and seizing Culp’s Hill, which the Confederates held. So Lee was forced to improvise. He decided to strike straight ahead, at Meade’s heavily fortified midsection. Confederate artillery would soften it up, and Longstreet would direct a frontal assault across a mile of open ground against the center of Missionary Ridge. Again Longstreet objected; again Lee wouldn’t listen. The Confederate artillery exhausted all its shells ineffectively, so was unable to support the assault—which has gone down in history as Pickett’s charge because Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division absorbed the worst of the horrible bloodbath it turned into.

Lee’s idolaters strained after the war to shift the blame, but the consensus today is that Lee managed the battle badly. Each supposed major blunder of his subordinates—Ewell’s failure to take the high ground of Cemetery Hill on July 1, Stuart’s getting out of touch and leaving Lee unapprised of what force he was facing, and the lateness of Longstreet’s attack on the second day—either wasn’t a blunder at all (if Longstreet had attacked earlier he would have encountered an even stronger Union position) or was caused by a lack of forcefulness and specificity in Lee’s orders.

Before Gettysburg, Lee had seemed not only to read the minds of Union generals but almost to expect his subordinates to read his. He was not in fact good at telling men what to do. That no doubt suited the Confederate fighting man, who didn’t take kindly to being told what to do—but Lee’s only weakness as a commander, his otherwise reverent nephew Fitzhugh Lee would write, was his “reluctance to oppose the wishes of others, or to order them to do anything that would be disagreeable and to which they would not consent.” With men as well as with women, his authority derived from his sightliness, politeness, and unimpeachability. His usually cheerful detachment patently covered solemn depths, depths faintly lit by glints of previous and potential rejection of self and others. It all seemed Olympian, in a Christian cavalier sort of way. Officers’ hearts went out to him across the latitude he granted them to be willingly, creatively honorable. Longstreet speaks of responding to Lee at another critical moment by “receiving his anxious expressions really as appeals for reinforcement of his unexpressed wish.” When people obey you because they think you enable them to follow their own instincts, you need a keen instinct yourself for when they’re getting out of touch, as Stuart did, and when they are balking for good reason, as Longstreet did. As a father Lee was fond but fretful, as a husband devoted but distant. As an attacking general he was inspiring but not necessarily cogent.

At Gettysburg he was jittery, snappish. He was 56 and bone weary. He may have had dysentery, though a scholar’s widely publicized assertion to that effect rests on tenuous evidence. He did have rheumatism and heart trouble. He kept fretfully wondering why Stuart was out of touch, worrying that something bad had happened to him. He had given Stuart broad discretion as usual, and Stuart had overextended himself. Stuart wasn’t frolicking. He had done his best to act on Lee’s written instructions: “You will . . . be able to judge whether you can pass around their army without hindrance, doing them all the damage you can, and cross the [Potomac] east of the mountains. In either case, after crossing the river, you must move on and feel the right of Ewell’s troops, collecting information, provisions, etc.” But he had not, in fact, been able to judge: he met several hindrances in the form of Union troops, a swollen river that he and his men managed only heroically to cross, and 150 Federal wagons that he captured before he crossed the river. And he had not sent word of what he was up to.

When on the afternoon of the second day Stuart did show up at Gettysburg, after pushing himself nearly to exhaustion, Lee’s only greeting to him is said to have been, “Well, General Stuart, you are here at last.” A coolly devastating cut: Lee’s way of chewing out someone who he felt had let him down. In the months after Gettysburg, as Lee stewed over his defeat, he repeatedly criticized the laxness of Stuart’s command, deeply hurting a man who prided himself on the sort of dashing freelance effectiveness by which Lee’s father, Maj. Gen. Light-Horse Harry, had defined himself. A bond of implicit trust had been broken. Loving-son figure had failed loving-father figure and vice versa.

In the past Lee had also granted Ewell and Longstreet wide discretion, and it had paid off. Maybe his magic in Virginia didn’t travel. “The whole affair was disjointed,” Taylor the aide said of Gettysburg. “There was an utter absence of accord in the movements of the several commands.”

Why did Lee stake everything, finally, on an ill-considered thrust straight up the middle? Lee’s critics have never come up with a logical explanation. Evidently he just got his blood up, as the expression goes. When the usually repressed Lee felt an overpowering need for emotional release, and had an army at his disposal and another one in front of him, he couldn’t hold back. And why should Lee expect his imprudence to be any less unsettling to Meade than it had been to the other Union commanders?

The spot against which he hurled Pickett was right in front of Meade’s headquarters. (Once, Dwight Eisenhower, who admired Lee’s generalship, took Field Marshal Montgomery to visit the Gettysburg battlefield. They looked at the site of Pickett’s charge and were baffled. Eisenhower said, “The man [Lee] must have got so mad that he wanted to hit that guy [Meade] with a brick.”)

Pickett’s troops advanced with precision, closed up the gaps that withering fire tore into their smartly dressed ranks, and at close quarters fought tooth and nail. Acouple of hundred Confederates did break the Union line, but only briefly. Someone counted 15 bodies on a patch of ground less than five feet wide and three feet long. It has been estimated that 10,500 Johnny Rebs made the charge and 5,675—roughly 54 percent—fell dead or wounded. As a Captain Spessard charged, he saw his son shot dead. He laid him out gently on the ground, kissed him, and got back to advancing.

As the minority who hadn’t been cut to ribbons streamed back to the Confederate lines, Lee rode in splendid calm among them, apologizing. “It’s all my fault,” he assured stunned privates and corporals. He took the time to admonish, mildly, an officer who was beating his horse: “Don’t whip him, captain; it does no good. I had a foolish horse, once, and kind treatment is the best.” Then he resumed his apologies: “I am very sorry—the task was too great for you—but we mustn’t despond.” Shelby Foote has called this Lee’s finest moment. But generals don’t want apologies from those beneath them, and that goes both ways. After midnight, he told a cavalry officer, “I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett’s division of Virginians. . . . ” Then he fell silent, and it was then that he exclaimed, as the officer later wrote it down, “Too bad! Too bad! OH! TOO BAD!”

Pickett’s charge wasn’t the half of it. Altogether at Gettysburg as many as 28,000 Confederates were killed, wounded, captured, or missing: more than a third of Lee’s whole army. Perhaps it was because Meade and his troops were so stunned by their own losses—about 23,000—that they failed to pursue Lee on his withdrawal south, trap him against the flooded Potomac, and wipe his army out. Lincoln and the Northern press were furious that this didn’t happen.

For months Lee had been traveling with a pet hen. Meant for the stewpot, she had won his heart by entering his tent first thing every morning and laying his breakfast egg under his Spartan cot. As the Army of Northern Virginia was breaking camp in all deliberate speed for the withdrawal, Lee’s staff ran around anxiously crying, “ Where is the hen? ” Lee himself found her nestled in her accustomed spot on the wagon that transported his personal matériel. Life goes on.

After Gettysburg, Lee never mounted another murderous head-on assault. He went on the defensive. Grant took over command of the eastern front and 118,700 men. He set out to grind Lee’s 64,000 down. Lee had his men well dug in. Grant resolved to turn his flank, force him into a weaker position, and crush him.

On April 9, 1865, Lee finally had to admit that he was trapped. At the beginning of Lee’s long, combative retreat by stages from Grant’s overpowering numbers, he had 64,000 men. By the end they had inflicted 63,000 Union casualties but had been reduced themselves to fewer than 10,000.

To be sure, there were those in Lee’s army who proposed continuing the struggle as guerrillas or by reorganizing under the governors of the various Confederate states. Lee cut off any such talk. He was a professional soldier. He had seen more than enough of governors who would be commanders, and he had no respect for ragtag guerrilladom. He told Col. Edward Porter Alexander, his artillery commander, . . . the men would become mere bands of marauders, and the enemy’s cavalry would pursue them and overrun many wide sections they may never have occasion to visit. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from.”

“And, as for myself, you young fellows might go to bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be, to go to Gen. Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences.” That is what he did on April 9, 1865, at a farmhouse in the village of Appomattox Court House, wearing a fulldress uniform and carrying a borrowed ceremonial sword which he did not surrender.

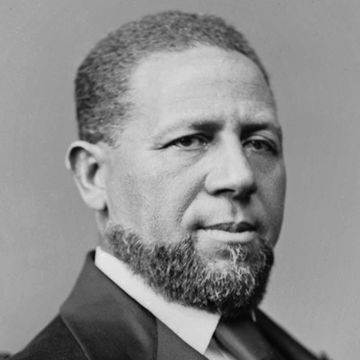

Thomas Morris Chester, the only black correspondent for a major daily newspaper (the Philadelphia Press ) during the war, had nothing but scorn for the Confederacy, and referred to Lee as a “notorious rebel.” But when Chester witnessed Lee’s arrival in shattered, burned-out Richmond after the surrender, his dispatch sounded a more sympathetic note. After Lee “alighted from his horse, he immediately uncovered his head, thinly covered with silver hairs, as he had done in acknowledgment of the veneration of the people along the streets,” Chester wrote. “There was a general rush of the small crowd to shake hands with him. During these manifestations not a word was spoken, and when the ceremony was through, the General bowed and ascended his steps. The silence was then broken by a few voices calling for a speech, to which he paid no attention. The General then passed into his house, and the crowd dispersed.”

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Advertisement

Supported by

Ghost of the Confederacy

- Share full article

By Fergus M. Bordewich

- June 27, 2014

Robert E. Lee occupies a remarkable place in the pantheon of American history, combining in the minds of many, Michael Korda writes in this admiring and briskly written biography, “a strange combination of martyr, secular saint, Southern gentleman and perfect warrior.” Indeed, Korda aptly adds, “It is hard to think of any other general who had fought against his own country being so completely reintegrated into national life.”

Lee has been a popular subject of biography virtually from his death in 1870, at the age of 63, through the four magisterial volumes of Douglas Southall Freeman in the 1930s to Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s intimate 2007 study of Lee and his letters, “Reading the Man.” Korda, the author of earlier biographies of Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower, aspires to pry the marble lid off the Lee legend to reveal the human being beneath.

He draws a generally sympathetic portrait of a master strategist who was as physically fearless on the battlefield as he was reserved in personal relations. He was, Korda writes, “a perfectionist, obsessed by duty,” but also “charming, funny and flirtatious,” an animal lover, a talented cartographer and a devoted parent, as well as “a noble, tragic figure, indeed one whose bearing and dignity conferred nobility on the cause for which he fought and still does confer it in the minds of many people.”

Graduating second in his class at West Point, Lee was commissioned into the engineers, then the most prestigious branch of the Army. He spent several unremarkable decades directing the construction of coastal fortifications, including Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, and somewhat more memorably, diverting the course of the Mississippi River at St. Louis. The Lee legend was born during the Mexican War, when he won the highest praise from the commander of the invading American army, Winfield Scott, for his bold reconnaissance behind enemy lines, during which he participated in three battles and crossed enemy territory three separate times in 36 hours — “the greatest feat of physical and moral courage” of the campaign, in Scott’s words. In 1859, when Scott was the overall commander of the United States Army, Lee was tapped to lead the company of Marines that captured John Brown at Harpers Ferry. Two years later, as state after state seceded from the Union, Lincoln offered Lee the command of the federal forces. He of course declined, and took his talents south.

Korda portrays the Lee of 1861 as a man tragically torn between loyalty to his nation and his native state. That Lee agonized over his decision is certainly true. However, Korda does not consider the fact that Lee was also heir to an antifederalist tradition embedded deep in the political circuitry of the Virginia elite, and of his own family: 70 years earlier, in 1790, Robert’s father, the Revolutionary War hero Henry Lee, declared in response to what he considered a slighting of Southern interests, “I had rather myself submit to all the hazards of war and risk the loss of everything dear to me in life, than to live under the rule of a fixed insolent Northern majority.” Many other Southern-born officers remained unshaken in their loyalty to the Union.

Korda provides crisp and concise, if conventional, accounts of Lee’s major engagements. We rarely hear from ordinary soldiers or feel the terror of battle amid the fog of war, but Korda is good at explaining Lee’s strategic thinking, the maneuvering of armies and the sometimes crippling limitations imposed by logistics, bad maps and worse roads.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee was the leading Confederate general during the U.S. Civil War and has been venerated as a heroic figure in the American South.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert E. Lee became military prominence during the U.S. Civil War, commanding his home state's armed forces and becoming general-in-chief of the Confederate troops toward the end of the conflict. Though the Union won the war, Lee earned renown as a military tactician for scoring several significant victories on the battlefield. He became president of Washington College and, renamed Washington and Lee University after he died in 1870.

Quick Facts

FULL NAME: Robert Edward Lee BORN: January 19, 1807 DIED: October 12, 1870 BIRTHPLACE: Stratford, Virginia SPOUSE: Mary Custis (1831-1870) CHILDREN: George Washington Custis, William “Rooney,” Robert Jr, Mary, Anne, Eleanor Agnes, and Mildred ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Early Years

A Confederate general who led southern forces against the Union Army in the U.S. Civil War, Robert Edward Lee was born on Jan. 19, 1807, at his family home of Stratford Hall in northeastern Virginia.

Lee saw himself as an extension of his family's greatness. At 18, he enrolled at West Point Military Academy, where he put his drive and serious mind to work. He placed second in his graduating class after four spotless years without a demerit and wrapped up his studies with perfect scores in artillery, infantry, and cavalry.

Wife and Children

After graduating from West Point, Lee married Mary Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington (from her first marriage before meeting George Washington) in 1831. The couple wed on Mary Custis’s family plantation in Arlington, Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C. They would make the estate their primary home for the next 30 years. In 1857, Mary inherited the Arlington plantation outright following her father’s death. However, after the outbreak of the Civil War, Union troops occupied the plantation, and the federal government seized the land. In 1864, the government began constructing a new national cemetery to bury and honor the war’s military dead. After that, the former Custis/Lee home was transformed into one of the most hallowed places in American history— Arlington National Cemetery .

Together, they had seven children: four daughters (Mary, Annie, Agnes, and Mildred) and three sons (Custis, Rooney, and Rob) who followed their father to serve in the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

Early Military Career

While Mary and the children spent their lives on Mary's father's plantation, Lee stayed committed to his military obligations. His loyalties moved him around the country, from Savannah to St. Louis to New York.

In 1846, Lee got the chance he had been waiting for his whole military career when the United States went to war with Mexico. Serving under General Winfield Scott, Lee distinguished himself as a brave battle commander and a brilliant tactician. In the aftermath of the U.S. victory over its neighbor, Lee was held up as a hero. Scott showered Lee with particular praise, saying that if the United States went into another war, the government should consider taking out a life insurance policy on the commander.

But life away from the battlefield proved difficult for Lee to handle. He struggled with the mundane tasks associated with his work and life. For a time, he returned to his wife's family's plantation to manage the estate following the death of his father-in-law. The property had fallen under hard times, and for two long years, he tried to make it profitable again.

Robert E. Lee and Slavery

Lee did not own slaves in his youth, but he and Mary Custis Lee inherited enslaved people from both his mother and her father, and it’s believed Lee himself owned between 10-15 enslaved people during his lifetime. His racial attitudes reflected much of his background, and while he wrote to Mary about the moral and political evils of slavery, he held views of white superiority. He saw slavery as necessary to maintain order between races. He opposed abolitionism, which he saw as a northern effort to inflict political will on the South.

When Lee’s father-in-law died in 1857, Lee became executor of his estate, tasked with managing the Arlington plantation. During this period, despite his father-in-law’s decree that his slaves be freed within five years of his death, Lee was accused of being a cruel and harsh overseer, with reports of beatings of some of the 200 enslaved people under his control, particularly those who had tried to escape.

In late 1862, to fulfill the terms of his father-in-law’s will, Lee signed deeds freeing some 150 of the enslaved workers at Arlington and other Custis plantations. Just a few months later, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863, freeing enslaved peoples in Confederate territory. Despite the Proclamation, Lee, during his Gettysburg campaign later that year, continued his practice of seizing freed Blacks in Union territory to be sent into slavery in the South. Towards the end of the war, with the Confederacy desperate for recruits, he supported the idea of allowing enslaved peoples to serve in the army in exchange for their freedom. Still, the war ended before the policy was enacted.

Confederate Leader

In October 1859, Lee was summoned to put an end to an enslaved person insurrection led by John Brown at Harper's Ferry. Lee's orchestrated attack took just an hour to end the revolt, and his success put him on a shortlist of names to lead the Union Army should the nation go to war.

But Lee's commitment to the Army was superseded by his commitment to Virginia. After turning down an offer from President Abraham Lincoln to command the Union forces, Lee resigned from the military and returned home. While Lee had misgivings about centering a war on the slavery issue, after Virginia voted to secede from the nation on April 17, 1861, Lee agreed to help lead the Confederate forces.

Over the next year, Lee again distinguished himself on the battlefield. On June 1, 1862, he took control of the Army of Northern Virginia and drove back the Union Army during the Seven Days Battles near Richmond. In August of that year, he gave the Confederacy a crucial victory at Second Manassas (also known as the Second Battle of Bull Run).

But not all went well. He courted disaster when he tried to cross the Potomac at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, barely escaping the site of the bloodiest single-day skirmish of the war, which left some 22,000 combatants dead.

From July 1-3, 1863, Lee's forces suffered another round of heavy casualties in Pennsylvania. The three-day stand-off, known as the Battle of Gettysburg , wiped out a vast chunk of Lee's army, halting his invasion of the North while helping to turn the tide for the Union.

By the fall of 1864, Union General Ulysses S. Grant had gained the upper hand, decimating much of Richmond, the Confederacy's capital, and Petersburg. By early 1865, the fate of the war was clear, a fact driven home on April 2 when Lee was forced to abandon Richmond. A week later, a reluctant and despondent Lee surrendered to Grant at a private home in Appomattox, Virginia.

"I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant," he told an aide. "And I would rather die a thousand deaths."

Final Years and Death

Saved from being hanged as a traitor by a forgiving Lincoln and Grant, Lee returned to his family in April 1865. He eventually accepted a job as president of Washington College in western Virginia and devoted his efforts toward boosting the institution's enrollment and financial support.

In late September 1870, Lee suffered a massive stroke. He died at his home in Lexington, Virginia, surrounded by family, on Oct. 12. He was buried in a chapel at nearby Washington College. Shortly afterward, the college was renamed Washington and Lee University.

Disputed Legacy and Statue

In the decades after the Civil War, sympathizers regarded Lee as a heroic figure of the South. Several monuments to the late general sprung up before the end of the 19th century, notably in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Dallas, Texas. Lee’s birthday is commemorated in several southern states. Until 2020, Lee-Jackson Day (also commemorating Civil War General Stonewall Jackson ) was celebrated each January in Virginia. Texas celebrates Lee on his Jan. 19th birthday as part of Confederate Heroes Day. Mississippi and Alabama celebrate a combined state holiday in late January honoring both Lee and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr , while Florida commemorates Robert E. Lee Day as an unofficial state holiday.

Lee's complicated legacy became part of the culture wars that engulfed the country more than a century later. While some sought to have statues of Confederate leaders removed from public view, others argued that doing so represented an attempt to erase history. In 2017, after the City Council of Charlottesville, Virginia, voted to move a Lee statue from a park, Charlottesville became the site of several protests and counter-protests; in August, numerous demonstrators clashed, resulting in one death and 19 injuries.

In late October 2017, President Donald Trump 's chief of staff, John Kelly, further fanned the flames of the controversy with his appearance on Fox News. Addressing the topic of a Virginia church's decision to remove plaques that honored both Lee and Washington, Kelly called the Confederate general an "honorable man" and pointed to the "lack of an ability to compromise" as the cause of the Civil War. This analysis drew the ire of opponents.

Robert E. Lee in Movies

Robert E. Lee has been the subject of numerous biographies, documentaries, and novels, including several “alternative history” books depicting the South as winning the Civil War. Among the most popular books featuring Lee is a trilogy of novels . The first, written by Jeffrey Shaara, was the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Killer Angels, which became the basis for the 1993 film Gettysburg , starring Martin Sheen as Lee. After Jeffrey’s death, his son Michael completed the trilogy, publishing Gods and Generals and The Last Full Measure , the former of which was adapted into a 2003 film of the same name, starring Robert Duvall—himself a descendant of Robert E. Lee—as the famed general.

- I suppose there is nothing for me to do but go and see General Grant. And I would rather die a thousand deaths.

- Do your duty in all things. You cannot do more; you should never wish to do less.

- I cannot trust a man to control others who cannot control himself.

- Whiskey: I like it, I always did, and that is the reason I never use it.

- Obedience to lawful authority is the foundation of manly character.

- The education of a man is never completed until he dies.

- Never do a wrong thing to make a friend or keep one.

- You cannot be a true man until you learn to obey.

- In this enlightened age, there are few, I believe, but what will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country.

- You see what a poor sinner I am and how unworthy to possess what was given me; for that reason, it has been taken away.

- Everybody kind of perceives me as being angry. It's not anger, it's motivation.

- It is good that war is so horrible, or we might grow to like it.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Civil War Figures

The 13 Most Cunning Military Leaders

Clara Barton

Abraham Lincoln

The Story of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Arrest

Hiram R. Revels

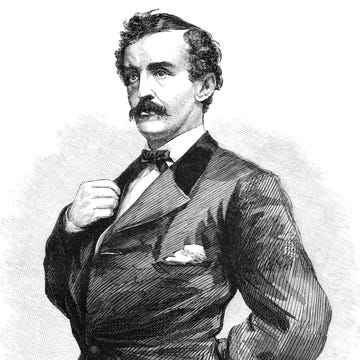

John Wilkes Booth

The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln

Stonewall Jackson

Frederick Douglass

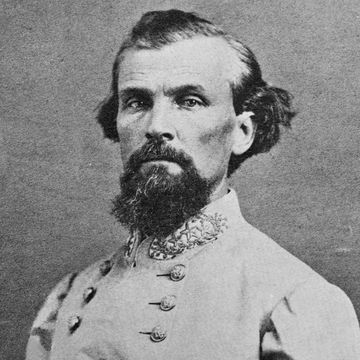

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

- Exhibitions Home

- Current Exhibitions

- All Exhibitions

- Loan Procedures for Institutions

- Special Presentations

The Civil War in America Biographies

Robert E. Lee

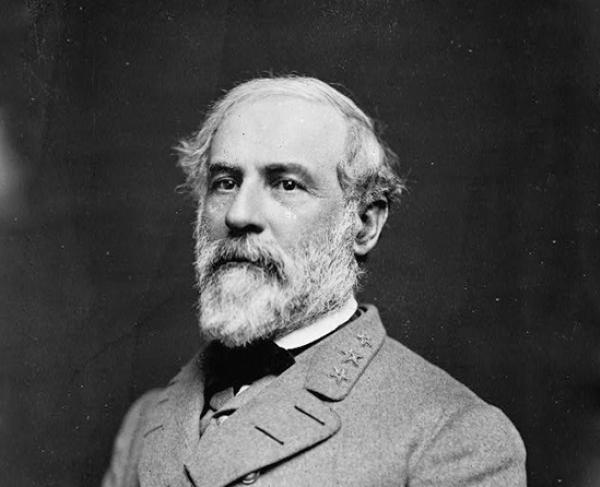

General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870). Prints and Photographs Division , Library of Congress. Digital ID # cwpb 04402

General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870) has continuously ranked as the leading iconic figure of the Confederacy. A son of Revolutionary War hero Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, Robert graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1829, ranking second in a class of forty six—and without a single demerit. His prewar record as an officer was distinguished by numerous engineering projects, service in the Mexican War , and nearly three years as commandant at West Point. In March and April 1861, Lee was offered command of the principal Union Army. Yet, after Virginia seceded on April 17, he determined that "to lift my hand against my own State and people is impossible." After resigning from the U.S. Army, he assumed command of Virginia's forces on April 23. Lee’s genius as a military tactician came to the fore after he was given command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June 1862. Despite being consistently outnumbered by the enemy, he led his forces in a series of remarkable victories that included Second Manassas (Second Bull Run), Fredericksburg , and Chancellorsville . The Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 marked Lee’s last major campaign on Northern soil. Remaining thereafter in Virginia, he mounted skillful defenses against the Union's unrelenting Overland Campaign and the siege of Petersburg (spring 1864–spring 1865). After Petersburg and Richmond fell, Lee was finally compelled to surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Later that year, Lee accepted the presidency of Washington College External (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, a position he retained until his death on October 12, 1870.

Related Items

- To Secede or Not to Secede

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Robert E. Lee

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 29, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

Robert E. Lee was a Confederate general who led the South’s attempt at secession during the Civil War . He challenged Union forces during the war’s bloodiest battles, including Antietam and Gettysburg , before surrendering to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865 at Appomattox Court House in Virginia, marking the end of the devastating conflict that nearly split the United States.

WATCH: Civil War Journal on HISTORY Vault

Who Was Robert E. Lee?

Robert Edward Lee was born in Stratford Hall, a plantation in Virginia, on January 19, 1807, to a wealthy and socially prominent family. His mother, Anne Hill Carter, also grew up on a plantation and his father, Colonel Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, was descended from colonists and become a Revolutionary War leader and three-term governor of Virginia.

But the family hit hard times when Lee’s father made a series of bad investments that left him in debtors’ prison. He fled to the West Indies and died in 1818 while trying to return to Virginia when Lee was barely a teen.

With little money for his education, Lee went to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point for a military education. He graduated second in his class in 1829—and the following month he would lose his mother.

Did you know? Robert E. Lee graduated second in his class from West Point. He did not receive a single demerit during his four years at the academy.

Robert E. Lee's Children

After graduation, Lee’s military career quickly took off as he chose a position with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers .

A year later, he began courting a childhood connection, Mary Custis Washington. Given his father’s diminished reputation, Lee had to propose twice to win approval to wed Mary, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington and the step-great-granddaughter of President George Washington .

The pair married in 1831; Lee and his wife had seven children, including three sons, George, William and Robert, who followed him into the military to fight for the Confederate States during the Civil War.

As the couple were establishing their family, Lee frequently travelled with the military on engineering projects. He first distinguished himself in battle during the Mexican-American War under General Winfield Scott in the battles of Veracruz , Churubusco and Chapultepec. Scott once declared that Lee was “the very best soldier that I ever saw in the field.”

Was Robert E. Lee a Slave Owner?

Lee did not grow up on a large plantation, but his wife inherited an enslaved worker in 1857 from her father, George Washington Park Custis.

Lee executed his father-in-law's will, which included Arlington House near Washington, D.C., a poorly managed plantation with debts and nearly 200 enslaved people, whom Custis wanted freed within five years of his death.

As a result of his father-in-law, Lee became owner of hundreds of enslaved workers. While historical accounts vary, Lee’s treatment of the enslaved peoples was described as being so combative and harsh that it led to revolts.

Lee at Harpers Ferry

During the 1850s, tensions between the abolitionist movement and slave owners reached a boiling point, and the union of states was near a breaking point. Lee entered the fray by halting a raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, capturing radical abolitionist John Brown and his followers.