Critical Thinking: Pengertian, Manfaat, dan Contoh Penerapannya

- Azzahra Ilka Aulia

- October 6, 2023

- Artikel , Business

Critical thinking adalah sebuah skill yang perlu dimiliki oleh setiap orang agar dapat membuat keputusan dan menyelesaikan masalah dengan baik. Skill ini biasanya ditandai dengan orang yang mampu berpikiran secara cermat dalam segala situasi.

Kemampuan ini tentu akan sangat berguna bagi seseorang dalam menjalankan pekerjaannya. Lalu, bagaimana cara berpikir kritis dengan baik?

Artikel di bawah ini akan menjelaskan tentang critical thinking dengan secara jelas. Simak artikel berikut ini sampai selesai, ya!

Apa itu Critical Thinking ?

Critical thinking adalah sebuah cara untuk berpikir dan mengkritik sesuatu dengan mempertanyakan suatu ide atau permasalahan.

Lebih lanjut, critical thinking artinya berpikir kritis atau dapat dipahami sebagai pola pikir yang tidak menerima informasi secara mentah.

Berpikir kritis umumnya melibatkan kemampuan untuk mengambil keputusan dengan cara yang bijak. Selain itu, berdasarkan definisi tersebut, berpikir kritis juga suatu pemahaman untuk menghasilkan keputusan yang paling optimal.

Critical thinking dapat dipahami sebagai salah satu soft skill yang sangat penting dalam membantu seseorang berorganisasi dan karyawan dalam perusahaan. Dengan memiliki pikiran yang kritis, suatu permasalahan dan keputusan dapat diselesaikan dengan tepat.

Manfaat Critical Thinking

Dengan kemampuan berpikir kritis, tentu banyak manfaat yang didapat bagi diri sendiri dan golongan. Berikut ini adalah beberapa manfaat berpikir kritis.

1. Kemampuan Berpikir Kritis dan Kreatif Meningkat

Dari berpikir kritis, Anda dapat melatih diri sendiri dengan menyelidiki dan mengajukan pertanyaan terhadap lingkungan di sekitar. Berpikir kritis dapat meningkatkan sisi kreatif dalam diri sendiri.

2. Kemampuan Problem Solving Meningkat

Skill pemecahan masalah sangat penting bagi diri sendiri dan juga bagi perusahaan. Dengan kemampuan problem solving dapat memungkinkan seseorang untuk mengidentifikasi, menganalisis, dan mencari solusi yang efektif terhadap suatu masalah.

3. Membuat Keputusan dengan Tepat

Membuat keputusan yang tepat melibatkan kemampuan berpikir kritis. Sebelum memutuskan sesuatu dengan tepat, kemampuan untuk mengevaluasi informasi, mempertimbangan opsi, dan memilih tindakan yang paling sesuai dengan tujuan yang dihadapi

4. Komunikasi yang Efektif Meningkat

Komunikasi yang efektif merupakan salah satu skill yang yang penting bagi pribadi dan profesional. Komunikasi yang efektif memungkinkan seseorang untuk menyampaikan pesan dengan jelas sehingga pesan yang disampaikan dapat dipahami oleh orang lain.

Baca Juga: Leadership: Pengertian, Gaya, Jenis-Jenis, dan Contohnya

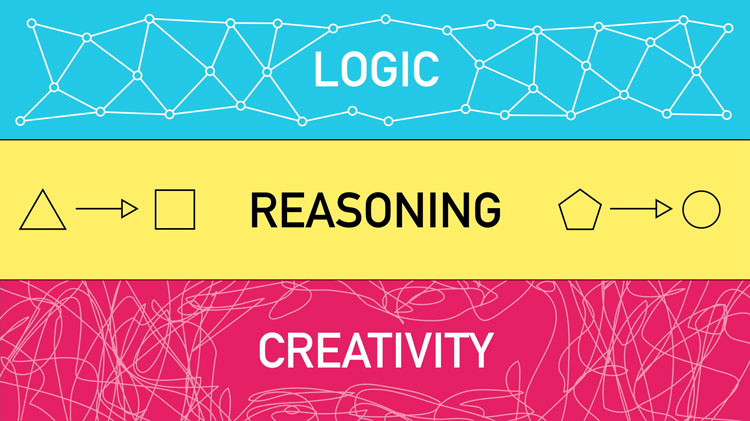

Komponen Critical Thinking

Berpikir kritis melibatkan beberapa komponen yang penting untuk membantu individu dalam menganalisis informasi dengan kritis.

Berikut ini adalah beberapa komponen berpikir kritis.

- Observing adalah proses mengamati sebuah objek, kejadian, atau informasi secara seksama dan kemudian memahami atau mencari pola hubungannya.

- Feeling adalah perasaan respons emosional atau perasaan yang timbul dari hasil suatu pengalaman atau situasi.

- Wondering berarti proses bertanya-tanya atau ingin tahu lebih tentang suatu fenomena yang mendorong eksplorasi lebih lanjut.

- Imagining berarti membayangkan atau membentuk gambaran tentang sesuatu yang belum terjadi atau digunakan untuk mengembangkan kreativitas dan inovasi.

- Inferring adalah menyimpulkan dengan logis berdasarkan bukti atau petunjuk yang tersedia.

- Knowledge adalah informasi atau pengetahuan yang dimiliki oleh seseorang mengenai sebuah topik atau bidang tertentu.

- Consulting adalah mencari atau meminta saran, pandangan, dan nasihat kepada orang yang memiliki pengetahuan dan pengalaman tentang suatu bidang.

- Identifying and analyzing adalah proses mengidentifikasi dan menganalisis sebuah elemen atau komponen untuk memahami strukturnya dalam pemecahan masalah.

- Judging berarti memberikan penilaian atau evaluasi terhadap sesuatu berdasarkan kriteria tertentu.

- Deciding adalah mengambil keputusan setelah mempertimbangkan berbagai informasi yang ada.

Indikator Critical Thinking

Kemampuan berpikir kritis memiliki indikator menjadi klarifikasi dasar untuk memberikan alasan dari sebuah kesimpulan. Berikut ini adalah beberapa indikator dari critical thinking .

1. Menyimpulkan ( Inference )

Menyimpulkan berarti adalah kemampuan untuk membuat kesimpulan atau asumsi berdasarkan bukti atau informasi yang ada.

2. Klarifikasi Lebih Lanjut ( Advanced Clarification )

Klarifikasi lebih lanjut adalah kemampuan untuk memperjelas atau menjelaskan informasi yang kurang jelas atau ambigu dengan bertanya pertanyaan yang tepat atau mencari klarifikasi tambahan.

3. Dugaan dan Keterpaduan ( Supposition and Integration )

Dugaan dan keterpaduan adalah kemampuan untuk membuat asumsi atau dugaan yang rasional, kemudian mengintegrasikan informasi tersebut ke dalam pemahaman atau penalaran yang lebih besar.

Cara Membentuk Kemampuan Critical Thinking

Dalam membentuk kemampuan berpikir kritis, tidak hanya dibentuk begitu saja. Namun, perlu mengembangkan kemampuan lainnya agar seimbang.

Berikut ini adalah cara melatih agar dapat berpikir dengan kritis.

- Memahami konsep dari berpikir kritis.

- Mengembangkan sikap yang terbuka.

- Melatih analisis secara kritis.

- Menggunakan keterampilan berpikir yang bijak.

- Melibatkan debat dan diskusi pada setiap kesempatan.

- Mempraktikkan pemecahan masalah.

- Memperdalam materi dan wawasan mengenai cara mendorong berpikiran kritis.

- Mengelola manajemen waktu.

- Menerima kritik dan saran dari setiap orang untuk membangun diri sendiri.

Contoh Critical Thinking

Skill critical thinking dapat memberikan kemungkinan seseorang untuk menganalisis, menilai, dan membuat keputusan dengan baik. Oleh karena itu, berpikir kritis harus diterapkan dalam segala bidang.

Berikut ini adalah beberapa contoh berpikir kritis yang dapat diterapkan dalam kehidupan sehari-hari.

- Ketika terdapat berita heboh yang muncul di internet, pembaca tentu akan langsung terpengaruh dan mungkin saja terpicu emosi. Orang yang memiliki pikiran kritis tentu tidak akan langsung percaya dengan berita yang tersebar karena bisa saja berita tersebut hoax.

- Ketika guru menerangkan pelajaran di kelas, murid yang berpikiran kritis akan mengajukan pertanyaan terkait pelajaran yang belum mereka belum pahami.

- Ketika pemerintahan mengesahkan sebuah peraturan, seseorang yang memiliki pikiran kritis tidak langsung menolak atau setuju. Mereka akan memahami isi peraturan tersebut apakah memberikan manfaat atau tidak bagi masyarakat.

- Ketika merencanakan perjalanan, seseorang akan berpikir kritis untuk mempertimbangkan rute terbaik, biaya, akomodasi, dan kebutuhan perjalanan lainnya, serta membuat rencana yang efisien dan menyeluruh.

- Seorang siswa akan berpikir kritis untuk memprioritaskan tugas, memperkirakan waktu yang diperlukan untuk masing-masing, dan memutuskan urutan yang paling efisien untuk menyelesaikan pekerjaan.

- Seseorang yang memiliki konflik pribadi akan mencoba berpikir kritis untuk memahami perspektif orang lain, menganalisis akar permasalahan, dan mencari solusi yang adil dan menguntungkan semua pihak yang terlibat.

Baca Juga: Engineering adalah: Skill, Jenis, Gaji & Jurusan Kuliahnya

Itulah penjelasan mengenai critical thinking dan penerapannya pada kehidupan sehari-hari yang perlu Anda ketahui.

Dengan menerapkan critical thinking pada kehidupan sehari-hari, akan memberikan keuntungan dalam termasuk dalam pengambilan keputusan, berinteraksi dengan orang lain, mengelola waktu, serta menghadapi dan memecahkan masalah.

Lingkungan yang baik juga akan dapat meningkatkan cara berpikir dengan kritis. Sekawan Media adalah salah satu industri di bidang teknologi yang membutuhkan critical thinking.

Sekawan Media terus mengembangkan sudut pandang dan cara kerja dalam melihat tantangan teknologi dan industri sehingga kami dapat terus memberikan hasil yang terukur, aplikatif, dan terbaik untuk klien.

- Terakhir Diperbarui: 6 October 2023

- Pengembangan Karir

- Digital Marketing

- Programming

Artikel Terkait

Apa itu IT Support? Pengertian, Tugas, Skill, dan Gaji

Rekrutmen adalah: Pengertian, Tujuan, Proses, dan Contohnya

Account Officer: Definisi, Gaji, Tugas, Skill, & Kualifikasi

React Developer: Karir, Gaji, dan Perbedaan Full Stack vs Front-end

Data Engineer: Pengertian, Tugas, Skill, dan Tanggung Jawab

Seputar Business Analyst, 5 Tanggung Jawab, Skill, dan Jenjang Karir

Sekawan Media merupakan perusahaan IT yang berfokus pada pembuatan aplikasi dan website. Didirikan pada tahun 2013, Sekawan Media telah memberikan solusi yang terbaik kepada ratusan klien dari berbagai industri.

- Berita & Informasi

- 2024 Sekawan Media Group

- Syarat & Ketentuan

- Ketentuan Layanan

- Kebijakan Privasi

- Cookie Policy

Copied To Clipboard

Bagikan Ke:

Critical Thinking: Pengertian, Manfaat, Cara Membentuk, dan Contohnya

Accidentally learning SEO, and want to learn more about Google algorithm, optimization and still trying to see another magic from content.

Kamu pasti sudah tidak asing dengan istilah critical thinking . Sebuah pola pikir yang banyak direkomendasikan untuk diasah ketika kamu akan bekerja atau menempuh pendidikan. Namun, tahukah kamu apa arti critical thinking sebenarnya? Apakah hanya sekedar berpikir kritis saja dan apakah bedanya dengan analytical thinking ?

Nah , agar kamu lebih jelas dalam kedua pola pikir tersebut, pastikan kamu membaca artikel ini hingga selesai, ya. Akan dijelaskan mengenai pengertian hingga apa saja contoh critical thinking yang bisa kamu kenali. Selamat membaca!

Apa itu critical thinking ?

Arti critical thinking adalah berpikir kritis di bahasa Indonesia. Secara mendetail, critical thinking artinya sebuah kemampuan berpikir secara rasional, menghubungkan antara ide dengan pemikiran logis sehingga menghasilkan keputusan terbaik. Pola pikir ini tidak hanya berfokus pada satu pemikiran saja.

Seseorang yang memiliki pola pikir satu ini akan mempertanyakan berbagai macam kemungkinan yang terjadi sehingga menimbulkan solusi-solusi baru. Secara tidak langsung, critical thinking memungkinkan kamu melakukan identifikasi, berargumen, dan menyelesaikan masalah sekaligus.

Baca juga: Mengenal Design Thinking: 4 Elemen dan Cara Mengaplikasikan

Bedanya critical thinking dengan analytical thinking

Selain berpikir kritis, ada juga istilah analytical thinking . Meski kebanyakan orang menganggap keduanya merupakan hal yang sama, namun ternyata kedua pola pikir ini memiliki sisi yang berbeda. Perbedaan critical thinking dan analytical thinking yang paling dasar adalah tujuan dari masing-masing pola pikir.

Critical thinking adalah pola pikir yang digunakan untuk meyakinkan apakah sebuah keputusan telah sesuai dan rasional. Pola pikir ini akan membuka kemungkinan-kemungkinan lain sehingga akan lebih selektif dalam mencermati sebuah keputusan. Sedangkan analytical thinking adalah pola pikir yang menganalisis sebuah fakta hingga mendetail. Pemikiran ini akan meneliti lebih jauh mengenai satu keputusan saja, misalnya dengan mempertimbangkan baik dan buruknya sebuah keputusan tanpa mengeksplor keputusan lain.

Baca juga: 6 Contoh analytical skills dan cara meningkatkannya

Manfaat critical thinking

Critical thinking memiliki beberapa manfaat bagi individu yang memilikinya maupun perusahaan yang memiliki karyawan dengan kompetensi ini. Simak selengkapnya berikut ini.

- Menggali berbagai kemungkinan untuk mendapatkan hal terbaik

- Meningkatkan kreativitas tiap individu

- Keputusan yang ditentukan punya alasan yang sagat kuat

- Keputusan yang tepat akan membawa perkembangan yang baik bagi perusahaan

- Menekan kemungkinan buruk yang terjadi karena sudah dipertimbangkan secara matang

- Dapat menyelesaikan masalah yang kompleks dengan keputusan yang singkat

Baca juga: Computational Thinking: Pengertian, 4 Landasan, Manfaat, dan Contohnya

Cara membentuk critical thinking

Melihat bagaimana pola pikir ini bisa membawa manfaat bagi tiap individu maupun lingkup secara besar, tidak ada salahnya kamu mencoba membentuk critical thinking mulai sekarang. Bagaimana caranya? Cek beberapa tahap berikut ini, yuk !

1. Analisis 5W + 1H

Ketika kamu mendapatkan sebuah kasus atau fakta, coba telaah pernyataan tersebut dengan 5W + 1H, yang terdiri dari what , why , when , who , where , dan how . Misalkan ada sebuah perusahaan yang akan melakukan ekspansi ke sebuah daerah, dan ditentukanlah daerah A. Nah , kamu bisa jabarkan topik tersebut menjadi seperti ini:

- Who (Siapa). Siapa yang memberikan ide tersebut? Siapa yang akan bertanggung jawab terhadap project ini?

- When (Kapan). Kapan ekspansi akan dilakukan? Apakah momennya tepat atau tidak?

- Where (Dimana). Dimana letak kantor cabang akan dibangun? Apakah sudah strategis?

- Why (Mengapa). Mengapa tempat dan momen tersebut harus dipilih untuk ekspansi?

- What (Apa). Apa tantangan yang akan dihadapi? Misal lokasi tersebut rawan banjir, dan lain-lain. Apakah bisa digunakan untuk berkembang dalam jangka panjang?

- How (Bagaimana). Bagaimana cara mengatasi tantangan yang ada di tempat tersebut? Bagaimana cara mengembangkan kantor cabang dalam jangka pendek?

2. Buka kesempatan untuk menerima pemikiran lain

Terkadang setiap orang punya ide atau pendapat yang berbeda dengan keputusan yang ada. Coba beri ruang untuk menyampaikan ide dan pendapat dari orang lain. Agar lebih efisien, tentukan batas waktu kapan keputusan harus segera didapatkan sehingga orang-orang yang berada di tim kamu akan lebih kritis untuk segera mengumpulkan idenya.

3. Coba identifikasi argumen yang berbeda denganmu

Dari ide yang telah terkumpul, tidak semua bisa digunakan. Pilih beberapa ide yang berbeda serta paling memungkinkan untuk dipertimbangkan. Kemudian identifikasi menggunakan cara yang sama atau mintalah timmu untuk menjelaskan mengapa mengutarakan ide tersebut.

4. Kenali kelebihan dan kekurangan tiap keputusan

Setiap keputusan tentu memiliki kelebihan dan kekurangannya. Maka, jangan lupa untuk menimbang apa kelebihan dan kekurangan yang akan didapatkan jika menggunakan keputusan tersebut. Semakin mendetail kamu bisa menghitung kelebihan dan kekurangan yang dimiliki, maka akan semakin baik. Namun pastikan masih dalam satu pembahasan yang sama, ya.

5. Berikan pendapat dan fakta yang mendukung

Untuk menguatkan sebuah keputusan, cobalah untuk memberi pendapat serta fakta yang mendukung. Mungkin jika strategi tersebut sudah pernah dilakukan, carilah data pendukung di internet berupa berita atau kumpulan statistik yang berkaitan dengan permasalahan yang kamu bahas.

Baca juga: 12 Cara berpikir positif di tempat kerja yang penting untuk diterapkan

Nah , sekarang kamu sudah memahami arti hingga perbedaan critical thinking dengan analytical thinking . Dengan pola pikir ini, kamu bisa lebih terbuka dalam menerima pendapat dan lebih kritis dengan perkembangan yang bisa memajukan bisnis kamu. Selain itu, critical thinking juga akan meningkatkan value kamu sebagai individu.

Kalau kamu ingin mendapatkan informasi serupa yang menarik, baca artikel lainnya di EKRUT Media atau tonton video menarik yang ada di YouTube official EKRUT. Dan, jika kamu sedang mencari informasi lowongan kerja di perusahaan atau startup ternama di Indonesia, klik sign up di EKRUT sekarang juga!

- skillsyouneed.com

- phylosophy.hku.hk

Apakah Kamu Sedang Mencari Pekerjaan?

Artikel terkait.

5 Contoh Biografi Diri Sendiri untuk Peluang dan Perkembangan Karier

Alvina Vivian

10 Cara Menulis Artikel yang Baik dan Benar untuk Pemula

Anisa Sekarningrum

Tips Menyampaikan Kata-kata Perpisahan Kerja yang Berkesan beserta Contohnya

Maria Tri Handayani

Apa Itu Critical Thinking dan Mengapa Penting bagi Orang Indonesia?

Apa itu critical thinking? Mengapa critical thinking penting bagi para pelajar di Indonesia? Berikut ini penjelasannya.

tirto.id - Kemampuan critical thinking atau berpikir kritis penting dimiliki bagi manusia Indonesia. Dengan berpikir secara logis, rasional, serta dapat menganalisis fakta dan data, seseorang tidak mudah tersesat dalam menghadapi arus informasi data seperti sekarang ini.

Apa itu critical thinking ? Mengapa kemampuan critical thinking penting bagi orang Indonesia?

Definisi Critical Thinking

Sebenarnya tidak ada definisi tunggal tentang critical thinking . Para akademisi punya definisi berbeda tentang critical thinking .

Monash University dalam publikasi di situs resminya, menjelaskan bahwa berpikir kritis ( critical thinking ) adalah jenis pemikiran di mana seseorang mempertanyakan, menganalisis, menafsirkan, dan membuat penilaian tentang sesuatu yang dibaca, didengar, dikatakan atau ditulis. Definisi ini berangkat dari asal kata “kritis” dalam Bahasa Yunani disebut “kritikos” yang berarti “mampu menilai atau membedakan.”

Critical thinking sebenarnya sudah sudah dilakukan sejak di era filsuf Yunani Kuno, tetapi istilah ini baru populer di dunia akademik pada 1987. Michael Scriven dan Richard Paul mempopulerkan istilah tersebut pada Konferensi Internasional Tahunan ke-8 tentang Pemikiran Kritis dan Reformasi Pendidikan, Musim Panas 1987. Keduanya adalah profesor dan peneliti di bidang critical thinking .

Kedua ahli ini mendefinisikan berpikir kritis adalah proses intelektual mengkonseptualisasikan, menganalisis, mensitesis dan atau menghasilkan informasi sebagai panduan keyakinan atau tindakan. Informasi ini dikumpulkan dari hasil pengamatan, pengalaman, refleksi, penalaran, atau komunikasi.

Dalam tesaurus Bahasa Indonesia, kata “kritis” bermakna; bersifat tidak lekas percaya, bersifat selalu berusaha menemukan kesalahan atau kekeliruan, atau tajam dalam penganalisisan.

Kendati ada perbedaan definisi tentang berpikir kritis, ada beberapa inti utama dari metode berpikir ini, antara lain:

1. Memperjelas tujuan dan konteks pemikiran

Memperjelas tujuan dan konteks pemikiran ini maksudnya adalah memilah dan memilih informasi yang sesuai dengan kebutuhan.

2. Mempertanyakan sumber informasi

Setelah informasi yang sesuai dikumpulkan, tahapan selanjutnya adalah mempertanyakan sumber informasi apakah punya kredibilitas atau orisinalitas. Pendek kata, kritik terhadap sumber.

3. Mengidentifikasi argumen

Setelah informasi valid didapatkan, langkah berikutnya adalah mengambil poin utama dari informasi tersebut yang akan menjadi bahan argumentasi.

4. Menganalisis sumber dan argumen

Bahan informasi ini kemudian diolah dengan teori untuk menjadi sebuah konstruksi argumen yang kuat.

5. Mengevaluasi argumen orang lain

Di tahap evaluasi ini, seseorang yang berpikir kritis perlu melihat klaim, bukti, dan alasan yang diajukan oleh orang lain.

6. Membuat atau mensintesis argumen sendiri

Setelah mempunyai bahan argumentasi dan mengevaluasi argumen orang lain, selanjutnya seseorang yang berpikir kritis membentuk argumennya sendiri.

Mengapa Berpikir Kritis itu Penting bagi Pelajar Indonesia?

Kemampuan berpikir kritis penting buat manusia Indonesia terutama bagi pelajar sebagai generasi penerus. Metode critical thinking akan membantu seseorang untuk mengobservasi masalah yang dimiliki dengan kemampuan analisis. Hal ini dibutuhkan dalam proses belajar maupun di dunia kerja.

Selain itu, dengan berpikir kritis juga dapat meningkatkan kreativitas seseorang serta mengasah cara berkomunikasi dan menyampaikan ide secara terstruktur dan informatif. Dengan kemampuan tersebut, seseorang dapat menemukan solusi terbaik ketika menghadapi berbagai permasalahan dalam kehidupannya.

Menurut Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), kemampuan critical thinking merupakan satu dari lima soft skills utama yang harus dimiliki individu pada 2030.

Dengan alasan itu, maka berpikir kritis sangat penting bagi pelajar saat ini yang kelak menjadi pemimpin di Indonesia. Di Indonesia sendiri sebenarnya gerakan berpikir kritis ini sudah dikembangkan dan disebarluaskan.

Intellectual Academy (IIA) yang berdiri sejak tahun 2018 telah memelopori gerakan berpikir kritis ini. Selain bergerak di bidang strategi belajar, daya ingat, dan growth mindset , lembaga ini fokus pada pengembangan critical thinking bagi para pemuda di Indonesia.

IIA pun memiliki berbagai platform pembelajaran yang bertujuan untuk meningkatkan kemampuan intelektualitas masyarakat Indonesia, khususnya pelajar, melalui platform dan aplikasi pendidikan seperti Mind Academy dan MindX Memory Games.

Dalam pengembangannya, IIA saat ini didukung oleh para pakar di bidang pendidikan dan neurosains. Mereka mengembangkan riset-risetnya dan berkomitmen memberikan pendidikan berkualitas guna mempersiapkan generasi muda. Tujuannya agar kelak para pelajar Indonesia siap memimpin Indonesia Emas di tahun 2045.

Sejalan dengan upaya menyebarluaskan gerakan berpikir kritis, IAA menggelar Critical Thinking Championship 2022. Kompetisi ini terbuka bagi para pelajar Indonesia dari jenjang SD hingga perguruan tinggi.

Untuk informasi jadwal dan cara pendaftaran kompetisi dapat dibaca pada artikel " Jadwal dan Cara Daftar Critical Thingking Championship 2022. "

Artikel Terkait

Kompetisi nasional critical thinking ke-4 digelar september 2024, urgensi berpikir kritis untuk masa depan pelajar indonesia, pengertian cara berpikir kritis dan metode menanamkannya pada anak, hasil final critical thinking championship 2022: ini para juaranya, sandiaga uno dapat tawaran jadi sekjen unwto, kementerian kebudayaan langsung jalankan program usai dibentuk, dahnil anzar kembali diminta jadi jubir prabowo, badan penyelenggara haji akan pisah diri dari kemenag pada 2026, sawit indonesia di tengah perang dagang, dasco jelaskan alasan mengapa prabowo beri luhut dua jabatan, penjelasan yandri soal surat undangan haul berkop kemendes, rincian gaji mayor teddy sebagai sekretaris kabinet & tni aktif, ditanya soal gaya blusukan, gibran: kami ini pembantu presiden, pemprov dki jakarta ajukan apbd 2025 sebesar rp91,1 triliun, kun wardana akan buat aplikasi keamanan dengan panic button, willy aditya dipilih jadi ketua komisi xiii dpr ri, gibran: tugas wapres tak jauh berbeda dari era sebelumnya, netty pks pimpin badan aspirasi dpr & bob hasan jadi ketua baleg, sebelum lengser, jokowi buat inpres soal proyek trem otonom ikn, kemenko marves dibubarkan prabowo, begini nasib pegawainya, brin minta pemerintah tindak tegas pengelola jurnal predator, kombes ahrie sonta diajukan sebagai ajudan presiden prabowo, masuk kabinet prabowo-gibran, zita anjani mundur dari dprd dki, dpr baru gelar rapat bersama kabinet prabowo-gibran pekan depan, shi sebut terbitnya pp 44 2024 belum selesaikan masalah hakim, yusril: jokowi tepat kirim nama capim kpk ke dpr sebelum lengser.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a widely accepted educational goal. Its definition is contested, but the competing definitions can be understood as differing conceptions of the same basic concept: careful thinking directed to a goal. Conceptions differ with respect to the scope of such thinking, the type of goal, the criteria and norms for thinking carefully, and the thinking components on which they focus. Its adoption as an educational goal has been recommended on the basis of respect for students’ autonomy and preparing students for success in life and for democratic citizenship. “Critical thinkers” have the dispositions and abilities that lead them to think critically when appropriate. The abilities can be identified directly; the dispositions indirectly, by considering what factors contribute to or impede exercise of the abilities. Standardized tests have been developed to assess the degree to which a person possesses such dispositions and abilities. Educational intervention has been shown experimentally to improve them, particularly when it includes dialogue, anchored instruction, and mentoring. Controversies have arisen over the generalizability of critical thinking across domains, over alleged bias in critical thinking theories and instruction, and over the relationship of critical thinking to other types of thinking.

2.1 Dewey’s Three Main Examples

2.2 dewey’s other examples, 2.3 further examples, 2.4 non-examples, 3. the definition of critical thinking, 4. its value, 5. the process of thinking critically, 6. components of the process, 7. contributory dispositions and abilities, 8.1 initiating dispositions, 8.2 internal dispositions, 9. critical thinking abilities, 10. required knowledge, 11. educational methods, 12.1 the generalizability of critical thinking, 12.2 bias in critical thinking theory and pedagogy, 12.3 relationship of critical thinking to other types of thinking, other internet resources, related entries.

Use of the term ‘critical thinking’ to describe an educational goal goes back to the American philosopher John Dewey (1910), who more commonly called it ‘reflective thinking’. He defined it as

active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends. (Dewey 1910: 6; 1933: 9)

and identified a habit of such consideration with a scientific attitude of mind. His lengthy quotations of Francis Bacon, John Locke, and John Stuart Mill indicate that he was not the first person to propose development of a scientific attitude of mind as an educational goal.

In the 1930s, many of the schools that participated in the Eight-Year Study of the Progressive Education Association (Aikin 1942) adopted critical thinking as an educational goal, for whose achievement the study’s Evaluation Staff developed tests (Smith, Tyler, & Evaluation Staff 1942). Glaser (1941) showed experimentally that it was possible to improve the critical thinking of high school students. Bloom’s influential taxonomy of cognitive educational objectives (Bloom et al. 1956) incorporated critical thinking abilities. Ennis (1962) proposed 12 aspects of critical thinking as a basis for research on the teaching and evaluation of critical thinking ability.

Since 1980, an annual international conference in California on critical thinking and educational reform has attracted tens of thousands of educators from all levels of education and from many parts of the world. Also since 1980, the state university system in California has required all undergraduate students to take a critical thinking course. Since 1983, the Association for Informal Logic and Critical Thinking has sponsored sessions in conjunction with the divisional meetings of the American Philosophical Association (APA). In 1987, the APA’s Committee on Pre-College Philosophy commissioned a consensus statement on critical thinking for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (Facione 1990a). Researchers have developed standardized tests of critical thinking abilities and dispositions; for details, see the Supplement on Assessment . Educational jurisdictions around the world now include critical thinking in guidelines for curriculum and assessment.

For details on this history, see the Supplement on History .

2. Examples and Non-Examples

Before considering the definition of critical thinking, it will be helpful to have in mind some examples of critical thinking, as well as some examples of kinds of thinking that would apparently not count as critical thinking.

Dewey (1910: 68–71; 1933: 91–94) takes as paradigms of reflective thinking three class papers of students in which they describe their thinking. The examples range from the everyday to the scientific.

Transit : “The other day, when I was down town on 16th Street, a clock caught my eye. I saw that the hands pointed to 12:20. This suggested that I had an engagement at 124th Street, at one o’clock. I reasoned that as it had taken me an hour to come down on a surface car, I should probably be twenty minutes late if I returned the same way. I might save twenty minutes by a subway express. But was there a station near? If not, I might lose more than twenty minutes in looking for one. Then I thought of the elevated, and I saw there was such a line within two blocks. But where was the station? If it were several blocks above or below the street I was on, I should lose time instead of gaining it. My mind went back to the subway express as quicker than the elevated; furthermore, I remembered that it went nearer than the elevated to the part of 124th Street I wished to reach, so that time would be saved at the end of the journey. I concluded in favor of the subway, and reached my destination by one o’clock.” (Dewey 1910: 68–69; 1933: 91–92)

Ferryboat : “Projecting nearly horizontally from the upper deck of the ferryboat on which I daily cross the river is a long white pole, having a gilded ball at its tip. It suggested a flagpole when I first saw it; its color, shape, and gilded ball agreed with this idea, and these reasons seemed to justify me in this belief. But soon difficulties presented themselves. The pole was nearly horizontal, an unusual position for a flagpole; in the next place, there was no pulley, ring, or cord by which to attach a flag; finally, there were elsewhere on the boat two vertical staffs from which flags were occasionally flown. It seemed probable that the pole was not there for flag-flying.

“I then tried to imagine all possible purposes of the pole, and to consider for which of these it was best suited: (a) Possibly it was an ornament. But as all the ferryboats and even the tugboats carried poles, this hypothesis was rejected. (b) Possibly it was the terminal of a wireless telegraph. But the same considerations made this improbable. Besides, the more natural place for such a terminal would be the highest part of the boat, on top of the pilot house. (c) Its purpose might be to point out the direction in which the boat is moving.

“In support of this conclusion, I discovered that the pole was lower than the pilot house, so that the steersman could easily see it. Moreover, the tip was enough higher than the base, so that, from the pilot’s position, it must appear to project far out in front of the boat. Moreover, the pilot being near the front of the boat, he would need some such guide as to its direction. Tugboats would also need poles for such a purpose. This hypothesis was so much more probable than the others that I accepted it. I formed the conclusion that the pole was set up for the purpose of showing the pilot the direction in which the boat pointed, to enable him to steer correctly.” (Dewey 1910: 69–70; 1933: 92–93)

Bubbles : “In washing tumblers in hot soapsuds and placing them mouth downward on a plate, bubbles appeared on the outside of the mouth of the tumblers and then went inside. Why? The presence of bubbles suggests air, which I note must come from inside the tumbler. I see that the soapy water on the plate prevents escape of the air save as it may be caught in bubbles. But why should air leave the tumbler? There was no substance entering to force it out. It must have expanded. It expands by increase of heat, or by decrease of pressure, or both. Could the air have become heated after the tumbler was taken from the hot suds? Clearly not the air that was already entangled in the water. If heated air was the cause, cold air must have entered in transferring the tumblers from the suds to the plate. I test to see if this supposition is true by taking several more tumblers out. Some I shake so as to make sure of entrapping cold air in them. Some I take out holding mouth downward in order to prevent cold air from entering. Bubbles appear on the outside of every one of the former and on none of the latter. I must be right in my inference. Air from the outside must have been expanded by the heat of the tumbler, which explains the appearance of the bubbles on the outside. But why do they then go inside? Cold contracts. The tumbler cooled and also the air inside it. Tension was removed, and hence bubbles appeared inside. To be sure of this, I test by placing a cup of ice on the tumbler while the bubbles are still forming outside. They soon reverse” (Dewey 1910: 70–71; 1933: 93–94).

Dewey (1910, 1933) sprinkles his book with other examples of critical thinking. We will refer to the following.

Weather : A man on a walk notices that it has suddenly become cool, thinks that it is probably going to rain, looks up and sees a dark cloud obscuring the sun, and quickens his steps (1910: 6–10; 1933: 9–13).

Disorder : A man finds his rooms on his return to them in disorder with his belongings thrown about, thinks at first of burglary as an explanation, then thinks of mischievous children as being an alternative explanation, then looks to see whether valuables are missing, and discovers that they are (1910: 82–83; 1933: 166–168).

Typhoid : A physician diagnosing a patient whose conspicuous symptoms suggest typhoid avoids drawing a conclusion until more data are gathered by questioning the patient and by making tests (1910: 85–86; 1933: 170).

Blur : A moving blur catches our eye in the distance, we ask ourselves whether it is a cloud of whirling dust or a tree moving its branches or a man signaling to us, we think of other traits that should be found on each of those possibilities, and we look and see if those traits are found (1910: 102, 108; 1933: 121, 133).

Suction pump : In thinking about the suction pump, the scientist first notes that it will draw water only to a maximum height of 33 feet at sea level and to a lesser maximum height at higher elevations, selects for attention the differing atmospheric pressure at these elevations, sets up experiments in which the air is removed from a vessel containing water (when suction no longer works) and in which the weight of air at various levels is calculated, compares the results of reasoning about the height to which a given weight of air will allow a suction pump to raise water with the observed maximum height at different elevations, and finally assimilates the suction pump to such apparently different phenomena as the siphon and the rising of a balloon (1910: 150–153; 1933: 195–198).

Diamond : A passenger in a car driving in a diamond lane reserved for vehicles with at least one passenger notices that the diamond marks on the pavement are far apart in some places and close together in others. Why? The driver suggests that the reason may be that the diamond marks are not needed where there is a solid double line separating the diamond lane from the adjoining lane, but are needed when there is a dotted single line permitting crossing into the diamond lane. Further observation confirms that the diamonds are close together when a dotted line separates the diamond lane from its neighbour, but otherwise far apart.

Rash : A woman suddenly develops a very itchy red rash on her throat and upper chest. She recently noticed a mark on the back of her right hand, but was not sure whether the mark was a rash or a scrape. She lies down in bed and thinks about what might be causing the rash and what to do about it. About two weeks before, she began taking blood pressure medication that contained a sulfa drug, and the pharmacist had warned her, in view of a previous allergic reaction to a medication containing a sulfa drug, to be on the alert for an allergic reaction; however, she had been taking the medication for two weeks with no such effect. The day before, she began using a new cream on her neck and upper chest; against the new cream as the cause was mark on the back of her hand, which had not been exposed to the cream. She began taking probiotics about a month before. She also recently started new eye drops, but she supposed that manufacturers of eye drops would be careful not to include allergy-causing components in the medication. The rash might be a heat rash, since she recently was sweating profusely from her upper body. Since she is about to go away on a short vacation, where she would not have access to her usual physician, she decides to keep taking the probiotics and using the new eye drops but to discontinue the blood pressure medication and to switch back to the old cream for her neck and upper chest. She forms a plan to consult her regular physician on her return about the blood pressure medication.

Candidate : Although Dewey included no examples of thinking directed at appraising the arguments of others, such thinking has come to be considered a kind of critical thinking. We find an example of such thinking in the performance task on the Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+), which its sponsoring organization describes as

a performance-based assessment that provides a measure of an institution’s contribution to the development of critical-thinking and written communication skills of its students. (Council for Aid to Education 2017)

A sample task posted on its website requires the test-taker to write a report for public distribution evaluating a fictional candidate’s policy proposals and their supporting arguments, using supplied background documents, with a recommendation on whether to endorse the candidate.

Immediate acceptance of an idea that suggests itself as a solution to a problem (e.g., a possible explanation of an event or phenomenon, an action that seems likely to produce a desired result) is “uncritical thinking, the minimum of reflection” (Dewey 1910: 13). On-going suspension of judgment in the light of doubt about a possible solution is not critical thinking (Dewey 1910: 108). Critique driven by a dogmatically held political or religious ideology is not critical thinking; thus Paulo Freire (1968 [1970]) is using the term (e.g., at 1970: 71, 81, 100, 146) in a more politically freighted sense that includes not only reflection but also revolutionary action against oppression. Derivation of a conclusion from given data using an algorithm is not critical thinking.

What is critical thinking? There are many definitions. Ennis (2016) lists 14 philosophically oriented scholarly definitions and three dictionary definitions. Following Rawls (1971), who distinguished his conception of justice from a utilitarian conception but regarded them as rival conceptions of the same concept, Ennis maintains that the 17 definitions are different conceptions of the same concept. Rawls articulated the shared concept of justice as

a characteristic set of principles for assigning basic rights and duties and for determining… the proper distribution of the benefits and burdens of social cooperation. (Rawls 1971: 5)

Bailin et al. (1999b) claim that, if one considers what sorts of thinking an educator would take not to be critical thinking and what sorts to be critical thinking, one can conclude that educators typically understand critical thinking to have at least three features.

- It is done for the purpose of making up one’s mind about what to believe or do.

- The person engaging in the thinking is trying to fulfill standards of adequacy and accuracy appropriate to the thinking.

- The thinking fulfills the relevant standards to some threshold level.

One could sum up the core concept that involves these three features by saying that critical thinking is careful goal-directed thinking. This core concept seems to apply to all the examples of critical thinking described in the previous section. As for the non-examples, their exclusion depends on construing careful thinking as excluding jumping immediately to conclusions, suspending judgment no matter how strong the evidence, reasoning from an unquestioned ideological or religious perspective, and routinely using an algorithm to answer a question.

If the core of critical thinking is careful goal-directed thinking, conceptions of it can vary according to its presumed scope, its presumed goal, one’s criteria and threshold for being careful, and the thinking component on which one focuses. As to its scope, some conceptions (e.g., Dewey 1910, 1933) restrict it to constructive thinking on the basis of one’s own observations and experiments, others (e.g., Ennis 1962; Fisher & Scriven 1997; Johnson 1992) to appraisal of the products of such thinking. Ennis (1991) and Bailin et al. (1999b) take it to cover both construction and appraisal. As to its goal, some conceptions restrict it to forming a judgment (Dewey 1910, 1933; Lipman 1987; Facione 1990a). Others allow for actions as well as beliefs as the end point of a process of critical thinking (Ennis 1991; Bailin et al. 1999b). As to the criteria and threshold for being careful, definitions vary in the term used to indicate that critical thinking satisfies certain norms: “intellectually disciplined” (Scriven & Paul 1987), “reasonable” (Ennis 1991), “skillful” (Lipman 1987), “skilled” (Fisher & Scriven 1997), “careful” (Bailin & Battersby 2009). Some definitions specify these norms, referring variously to “consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends” (Dewey 1910, 1933); “the methods of logical inquiry and reasoning” (Glaser 1941); “conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication” (Scriven & Paul 1987); the requirement that “it is sensitive to context, relies on criteria, and is self-correcting” (Lipman 1987); “evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations” (Facione 1990a); and “plus-minus considerations of the product in terms of appropriate standards (or criteria)” (Johnson 1992). Stanovich and Stanovich (2010) propose to ground the concept of critical thinking in the concept of rationality, which they understand as combining epistemic rationality (fitting one’s beliefs to the world) and instrumental rationality (optimizing goal fulfillment); a critical thinker, in their view, is someone with “a propensity to override suboptimal responses from the autonomous mind” (2010: 227). These variant specifications of norms for critical thinking are not necessarily incompatible with one another, and in any case presuppose the core notion of thinking carefully. As to the thinking component singled out, some definitions focus on suspension of judgment during the thinking (Dewey 1910; McPeck 1981), others on inquiry while judgment is suspended (Bailin & Battersby 2009, 2021), others on the resulting judgment (Facione 1990a), and still others on responsiveness to reasons (Siegel 1988). Kuhn (2019) takes critical thinking to be more a dialogic practice of advancing and responding to arguments than an individual ability.

In educational contexts, a definition of critical thinking is a “programmatic definition” (Scheffler 1960: 19). It expresses a practical program for achieving an educational goal. For this purpose, a one-sentence formulaic definition is much less useful than articulation of a critical thinking process, with criteria and standards for the kinds of thinking that the process may involve. The real educational goal is recognition, adoption and implementation by students of those criteria and standards. That adoption and implementation in turn consists in acquiring the knowledge, abilities and dispositions of a critical thinker.

Conceptions of critical thinking generally do not include moral integrity as part of the concept. Dewey, for example, took critical thinking to be the ultimate intellectual goal of education, but distinguished it from the development of social cooperation among school children, which he took to be the central moral goal. Ennis (1996, 2011) added to his previous list of critical thinking dispositions a group of dispositions to care about the dignity and worth of every person, which he described as a “correlative” (1996) disposition without which critical thinking would be less valuable and perhaps harmful. An educational program that aimed at developing critical thinking but not the correlative disposition to care about the dignity and worth of every person, he asserted, “would be deficient and perhaps dangerous” (Ennis 1996: 172).

Dewey thought that education for reflective thinking would be of value to both the individual and society; recognition in educational practice of the kinship to the scientific attitude of children’s native curiosity, fertile imagination and love of experimental inquiry “would make for individual happiness and the reduction of social waste” (Dewey 1910: iii). Schools participating in the Eight-Year Study took development of the habit of reflective thinking and skill in solving problems as a means to leading young people to understand, appreciate and live the democratic way of life characteristic of the United States (Aikin 1942: 17–18, 81). Harvey Siegel (1988: 55–61) has offered four considerations in support of adopting critical thinking as an educational ideal. (1) Respect for persons requires that schools and teachers honour students’ demands for reasons and explanations, deal with students honestly, and recognize the need to confront students’ independent judgment; these requirements concern the manner in which teachers treat students. (2) Education has the task of preparing children to be successful adults, a task that requires development of their self-sufficiency. (3) Education should initiate children into the rational traditions in such fields as history, science and mathematics. (4) Education should prepare children to become democratic citizens, which requires reasoned procedures and critical talents and attitudes. To supplement these considerations, Siegel (1988: 62–90) responds to two objections: the ideology objection that adoption of any educational ideal requires a prior ideological commitment and the indoctrination objection that cultivation of critical thinking cannot escape being a form of indoctrination.

Despite the diversity of our 11 examples, one can recognize a common pattern. Dewey analyzed it as consisting of five phases:

- suggestions , in which the mind leaps forward to a possible solution;

- an intellectualization of the difficulty or perplexity into a problem to be solved, a question for which the answer must be sought;

- the use of one suggestion after another as a leading idea, or hypothesis , to initiate and guide observation and other operations in collection of factual material;

- the mental elaboration of the idea or supposition as an idea or supposition ( reasoning , in the sense on which reasoning is a part, not the whole, of inference); and

- testing the hypothesis by overt or imaginative action. (Dewey 1933: 106–107; italics in original)

The process of reflective thinking consisting of these phases would be preceded by a perplexed, troubled or confused situation and followed by a cleared-up, unified, resolved situation (Dewey 1933: 106). The term ‘phases’ replaced the term ‘steps’ (Dewey 1910: 72), thus removing the earlier suggestion of an invariant sequence. Variants of the above analysis appeared in (Dewey 1916: 177) and (Dewey 1938: 101–119).

The variant formulations indicate the difficulty of giving a single logical analysis of such a varied process. The process of critical thinking may have a spiral pattern, with the problem being redefined in the light of obstacles to solving it as originally formulated. For example, the person in Transit might have concluded that getting to the appointment at the scheduled time was impossible and have reformulated the problem as that of rescheduling the appointment for a mutually convenient time. Further, defining a problem does not always follow after or lead immediately to an idea of a suggested solution. Nor should it do so, as Dewey himself recognized in describing the physician in Typhoid as avoiding any strong preference for this or that conclusion before getting further information (Dewey 1910: 85; 1933: 170). People with a hypothesis in mind, even one to which they have a very weak commitment, have a so-called “confirmation bias” (Nickerson 1998): they are likely to pay attention to evidence that confirms the hypothesis and to ignore evidence that counts against it or for some competing hypothesis. Detectives, intelligence agencies, and investigators of airplane accidents are well advised to gather relevant evidence systematically and to postpone even tentative adoption of an explanatory hypothesis until the collected evidence rules out with the appropriate degree of certainty all but one explanation. Dewey’s analysis of the critical thinking process can be faulted as well for requiring acceptance or rejection of a possible solution to a defined problem, with no allowance for deciding in the light of the available evidence to suspend judgment. Further, given the great variety of kinds of problems for which reflection is appropriate, there is likely to be variation in its component events. Perhaps the best way to conceptualize the critical thinking process is as a checklist whose component events can occur in a variety of orders, selectively, and more than once. These component events might include (1) noticing a difficulty, (2) defining the problem, (3) dividing the problem into manageable sub-problems, (4) formulating a variety of possible solutions to the problem or sub-problem, (5) determining what evidence is relevant to deciding among possible solutions to the problem or sub-problem, (6) devising a plan of systematic observation or experiment that will uncover the relevant evidence, (7) carrying out the plan of systematic observation or experimentation, (8) noting the results of the systematic observation or experiment, (9) gathering relevant testimony and information from others, (10) judging the credibility of testimony and information gathered from others, (11) drawing conclusions from gathered evidence and accepted testimony, and (12) accepting a solution that the evidence adequately supports (cf. Hitchcock 2017: 485).

Checklist conceptions of the process of critical thinking are open to the objection that they are too mechanical and procedural to fit the multi-dimensional and emotionally charged issues for which critical thinking is urgently needed (Paul 1984). For such issues, a more dialectical process is advocated, in which competing relevant world views are identified, their implications explored, and some sort of creative synthesis attempted.

If one considers the critical thinking process illustrated by the 11 examples, one can identify distinct kinds of mental acts and mental states that form part of it. To distinguish, label and briefly characterize these components is a useful preliminary to identifying abilities, skills, dispositions, attitudes, habits and the like that contribute causally to thinking critically. Identifying such abilities and habits is in turn a useful preliminary to setting educational goals. Setting the goals is in its turn a useful preliminary to designing strategies for helping learners to achieve the goals and to designing ways of measuring the extent to which learners have done so. Such measures provide both feedback to learners on their achievement and a basis for experimental research on the effectiveness of various strategies for educating people to think critically. Let us begin, then, by distinguishing the kinds of mental acts and mental events that can occur in a critical thinking process.

- Observing : One notices something in one’s immediate environment (sudden cooling of temperature in Weather , bubbles forming outside a glass and then going inside in Bubbles , a moving blur in the distance in Blur , a rash in Rash ). Or one notes the results of an experiment or systematic observation (valuables missing in Disorder , no suction without air pressure in Suction pump )

- Feeling : One feels puzzled or uncertain about something (how to get to an appointment on time in Transit , why the diamonds vary in spacing in Diamond ). One wants to resolve this perplexity. One feels satisfaction once one has worked out an answer (to take the subway express in Transit , diamonds closer when needed as a warning in Diamond ).

- Wondering : One formulates a question to be addressed (why bubbles form outside a tumbler taken from hot water in Bubbles , how suction pumps work in Suction pump , what caused the rash in Rash ).

- Imagining : One thinks of possible answers (bus or subway or elevated in Transit , flagpole or ornament or wireless communication aid or direction indicator in Ferryboat , allergic reaction or heat rash in Rash ).

- Inferring : One works out what would be the case if a possible answer were assumed (valuables missing if there has been a burglary in Disorder , earlier start to the rash if it is an allergic reaction to a sulfa drug in Rash ). Or one draws a conclusion once sufficient relevant evidence is gathered (take the subway in Transit , burglary in Disorder , discontinue blood pressure medication and new cream in Rash ).

- Knowledge : One uses stored knowledge of the subject-matter to generate possible answers or to infer what would be expected on the assumption of a particular answer (knowledge of a city’s public transit system in Transit , of the requirements for a flagpole in Ferryboat , of Boyle’s law in Bubbles , of allergic reactions in Rash ).

- Experimenting : One designs and carries out an experiment or a systematic observation to find out whether the results deduced from a possible answer will occur (looking at the location of the flagpole in relation to the pilot’s position in Ferryboat , putting an ice cube on top of a tumbler taken from hot water in Bubbles , measuring the height to which a suction pump will draw water at different elevations in Suction pump , noticing the spacing of diamonds when movement to or from a diamond lane is allowed in Diamond ).

- Consulting : One finds a source of information, gets the information from the source, and makes a judgment on whether to accept it. None of our 11 examples include searching for sources of information. In this respect they are unrepresentative, since most people nowadays have almost instant access to information relevant to answering any question, including many of those illustrated by the examples. However, Candidate includes the activities of extracting information from sources and evaluating its credibility.

- Identifying and analyzing arguments : One notices an argument and works out its structure and content as a preliminary to evaluating its strength. This activity is central to Candidate . It is an important part of a critical thinking process in which one surveys arguments for various positions on an issue.

- Judging : One makes a judgment on the basis of accumulated evidence and reasoning, such as the judgment in Ferryboat that the purpose of the pole is to provide direction to the pilot.

- Deciding : One makes a decision on what to do or on what policy to adopt, as in the decision in Transit to take the subway.

By definition, a person who does something voluntarily is both willing and able to do that thing at that time. Both the willingness and the ability contribute causally to the person’s action, in the sense that the voluntary action would not occur if either (or both) of these were lacking. For example, suppose that one is standing with one’s arms at one’s sides and one voluntarily lifts one’s right arm to an extended horizontal position. One would not do so if one were unable to lift one’s arm, if for example one’s right side was paralyzed as the result of a stroke. Nor would one do so if one were unwilling to lift one’s arm, if for example one were participating in a street demonstration at which a white supremacist was urging the crowd to lift their right arm in a Nazi salute and one were unwilling to express support in this way for the racist Nazi ideology. The same analysis applies to a voluntary mental process of thinking critically. It requires both willingness and ability to think critically, including willingness and ability to perform each of the mental acts that compose the process and to coordinate those acts in a sequence that is directed at resolving the initiating perplexity.

Consider willingness first. We can identify causal contributors to willingness to think critically by considering factors that would cause a person who was able to think critically about an issue nevertheless not to do so (Hamby 2014). For each factor, the opposite condition thus contributes causally to willingness to think critically on a particular occasion. For example, people who habitually jump to conclusions without considering alternatives will not think critically about issues that arise, even if they have the required abilities. The contrary condition of willingness to suspend judgment is thus a causal contributor to thinking critically.

Now consider ability. In contrast to the ability to move one’s arm, which can be completely absent because a stroke has left the arm paralyzed, the ability to think critically is a developed ability, whose absence is not a complete absence of ability to think but absence of ability to think well. We can identify the ability to think well directly, in terms of the norms and standards for good thinking. In general, to be able do well the thinking activities that can be components of a critical thinking process, one needs to know the concepts and principles that characterize their good performance, to recognize in particular cases that the concepts and principles apply, and to apply them. The knowledge, recognition and application may be procedural rather than declarative. It may be domain-specific rather than widely applicable, and in either case may need subject-matter knowledge, sometimes of a deep kind.

Reflections of the sort illustrated by the previous two paragraphs have led scholars to identify the knowledge, abilities and dispositions of a “critical thinker”, i.e., someone who thinks critically whenever it is appropriate to do so. We turn now to these three types of causal contributors to thinking critically. We start with dispositions, since arguably these are the most powerful contributors to being a critical thinker, can be fostered at an early stage of a child’s development, and are susceptible to general improvement (Glaser 1941: 175)

8. Critical Thinking Dispositions

Educational researchers use the term ‘dispositions’ broadly for the habits of mind and attitudes that contribute causally to being a critical thinker. Some writers (e.g., Paul & Elder 2006; Hamby 2014; Bailin & Battersby 2016a) propose to use the term ‘virtues’ for this dimension of a critical thinker. The virtues in question, although they are virtues of character, concern the person’s ways of thinking rather than the person’s ways of behaving towards others. They are not moral virtues but intellectual virtues, of the sort articulated by Zagzebski (1996) and discussed by Turri, Alfano, and Greco (2017).

On a realistic conception, thinking dispositions or intellectual virtues are real properties of thinkers. They are general tendencies, propensities, or inclinations to think in particular ways in particular circumstances, and can be genuinely explanatory (Siegel 1999). Sceptics argue that there is no evidence for a specific mental basis for the habits of mind that contribute to thinking critically, and that it is pedagogically misleading to posit such a basis (Bailin et al. 1999a). Whatever their status, critical thinking dispositions need motivation for their initial formation in a child—motivation that may be external or internal. As children develop, the force of habit will gradually become important in sustaining the disposition (Nieto & Valenzuela 2012). Mere force of habit, however, is unlikely to sustain critical thinking dispositions. Critical thinkers must value and enjoy using their knowledge and abilities to think things through for themselves. They must be committed to, and lovers of, inquiry.

A person may have a critical thinking disposition with respect to only some kinds of issues. For example, one could be open-minded about scientific issues but not about religious issues. Similarly, one could be confident in one’s ability to reason about the theological implications of the existence of evil in the world but not in one’s ability to reason about the best design for a guided ballistic missile.

Facione (1990a: 25) divides “affective dispositions” of critical thinking into approaches to life and living in general and approaches to specific issues, questions or problems. Adapting this distinction, one can usefully divide critical thinking dispositions into initiating dispositions (those that contribute causally to starting to think critically about an issue) and internal dispositions (those that contribute causally to doing a good job of thinking critically once one has started). The two categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, open-mindedness, in the sense of willingness to consider alternative points of view to one’s own, is both an initiating and an internal disposition.

Using the strategy of considering factors that would block people with the ability to think critically from doing so, we can identify as initiating dispositions for thinking critically attentiveness, a habit of inquiry, self-confidence, courage, open-mindedness, willingness to suspend judgment, trust in reason, wanting evidence for one’s beliefs, and seeking the truth. We consider briefly what each of these dispositions amounts to, in each case citing sources that acknowledge them.

- Attentiveness : One will not think critically if one fails to recognize an issue that needs to be thought through. For example, the pedestrian in Weather would not have looked up if he had not noticed that the air was suddenly cooler. To be a critical thinker, then, one needs to be habitually attentive to one’s surroundings, noticing not only what one senses but also sources of perplexity in messages received and in one’s own beliefs and attitudes (Facione 1990a: 25; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001).

- Habit of inquiry : Inquiry is effortful, and one needs an internal push to engage in it. For example, the student in Bubbles could easily have stopped at idle wondering about the cause of the bubbles rather than reasoning to a hypothesis, then designing and executing an experiment to test it. Thus willingness to think critically needs mental energy and initiative. What can supply that energy? Love of inquiry, or perhaps just a habit of inquiry. Hamby (2015) has argued that willingness to inquire is the central critical thinking virtue, one that encompasses all the others. It is recognized as a critical thinking disposition by Dewey (1910: 29; 1933: 35), Glaser (1941: 5), Ennis (1987: 12; 1991: 8), Facione (1990a: 25), Bailin et al. (1999b: 294), Halpern (1998: 452), and Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo (2001).

- Self-confidence : Lack of confidence in one’s abilities can block critical thinking. For example, if the woman in Rash lacked confidence in her ability to figure things out for herself, she might just have assumed that the rash on her chest was the allergic reaction to her medication against which the pharmacist had warned her. Thus willingness to think critically requires confidence in one’s ability to inquire (Facione 1990a: 25; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001).

- Courage : Fear of thinking for oneself can stop one from doing it. Thus willingness to think critically requires intellectual courage (Paul & Elder 2006: 16).

- Open-mindedness : A dogmatic attitude will impede thinking critically. For example, a person who adheres rigidly to a “pro-choice” position on the issue of the legal status of induced abortion is likely to be unwilling to consider seriously the issue of when in its development an unborn child acquires a moral right to life. Thus willingness to think critically requires open-mindedness, in the sense of a willingness to examine questions to which one already accepts an answer but which further evidence or reasoning might cause one to answer differently (Dewey 1933; Facione 1990a; Ennis 1991; Bailin et al. 1999b; Halpern 1998, Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001). Paul (1981) emphasizes open-mindedness about alternative world-views, and recommends a dialectical approach to integrating such views as central to what he calls “strong sense” critical thinking. In three studies, Haran, Ritov, & Mellers (2013) found that actively open-minded thinking, including “the tendency to weigh new evidence against a favored belief, to spend sufficient time on a problem before giving up, and to consider carefully the opinions of others in forming one’s own”, led study participants to acquire information and thus to make accurate estimations.

- Willingness to suspend judgment : Premature closure on an initial solution will block critical thinking. Thus willingness to think critically requires a willingness to suspend judgment while alternatives are explored (Facione 1990a; Ennis 1991; Halpern 1998).

- Trust in reason : Since distrust in the processes of reasoned inquiry will dissuade one from engaging in it, trust in them is an initiating critical thinking disposition (Facione 1990a, 25; Bailin et al. 1999b: 294; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001; Paul & Elder 2006). In reaction to an allegedly exclusive emphasis on reason in critical thinking theory and pedagogy, Thayer-Bacon (2000) argues that intuition, imagination, and emotion have important roles to play in an adequate conception of critical thinking that she calls “constructive thinking”. From her point of view, critical thinking requires trust not only in reason but also in intuition, imagination, and emotion.

- Seeking the truth : If one does not care about the truth but is content to stick with one’s initial bias on an issue, then one will not think critically about it. Seeking the truth is thus an initiating critical thinking disposition (Bailin et al. 1999b: 294; Facione, Facione, & Giancarlo 2001). A disposition to seek the truth is implicit in more specific critical thinking dispositions, such as trying to be well-informed, considering seriously points of view other than one’s own, looking for alternatives, suspending judgment when the evidence is insufficient, and adopting a position when the evidence supporting it is sufficient.

Some of the initiating dispositions, such as open-mindedness and willingness to suspend judgment, are also internal critical thinking dispositions, in the sense of mental habits or attitudes that contribute causally to doing a good job of critical thinking once one starts the process. But there are many other internal critical thinking dispositions. Some of them are parasitic on one’s conception of good thinking. For example, it is constitutive of good thinking about an issue to formulate the issue clearly and to maintain focus on it. For this purpose, one needs not only the corresponding ability but also the corresponding disposition. Ennis (1991: 8) describes it as the disposition “to determine and maintain focus on the conclusion or question”, Facione (1990a: 25) as “clarity in stating the question or concern”. Other internal dispositions are motivators to continue or adjust the critical thinking process, such as willingness to persist in a complex task and willingness to abandon nonproductive strategies in an attempt to self-correct (Halpern 1998: 452). For a list of identified internal critical thinking dispositions, see the Supplement on Internal Critical Thinking Dispositions .

Some theorists postulate skills, i.e., acquired abilities, as operative in critical thinking. It is not obvious, however, that a good mental act is the exercise of a generic acquired skill. Inferring an expected time of arrival, as in Transit , has some generic components but also uses non-generic subject-matter knowledge. Bailin et al. (1999a) argue against viewing critical thinking skills as generic and discrete, on the ground that skilled performance at a critical thinking task cannot be separated from knowledge of concepts and from domain-specific principles of good thinking. Talk of skills, they concede, is unproblematic if it means merely that a person with critical thinking skills is capable of intelligent performance.

Despite such scepticism, theorists of critical thinking have listed as general contributors to critical thinking what they variously call abilities (Glaser 1941; Ennis 1962, 1991), skills (Facione 1990a; Halpern 1998) or competencies (Fisher & Scriven 1997). Amalgamating these lists would produce a confusing and chaotic cornucopia of more than 50 possible educational objectives, with only partial overlap among them. It makes sense instead to try to understand the reasons for the multiplicity and diversity, and to make a selection according to one’s own reasons for singling out abilities to be developed in a critical thinking curriculum. Two reasons for diversity among lists of critical thinking abilities are the underlying conception of critical thinking and the envisaged educational level. Appraisal-only conceptions, for example, involve a different suite of abilities than constructive-only conceptions. Some lists, such as those in (Glaser 1941), are put forward as educational objectives for secondary school students, whereas others are proposed as objectives for college students (e.g., Facione 1990a).

The abilities described in the remaining paragraphs of this section emerge from reflection on the general abilities needed to do well the thinking activities identified in section 6 as components of the critical thinking process described in section 5 . The derivation of each collection of abilities is accompanied by citation of sources that list such abilities and of standardized tests that claim to test them.

Observational abilities : Careful and accurate observation sometimes requires specialist expertise and practice, as in the case of observing birds and observing accident scenes. However, there are general abilities of noticing what one’s senses are picking up from one’s environment and of being able to articulate clearly and accurately to oneself and others what one has observed. It helps in exercising them to be able to recognize and take into account factors that make one’s observation less trustworthy, such as prior framing of the situation, inadequate time, deficient senses, poor observation conditions, and the like. It helps as well to be skilled at taking steps to make one’s observation more trustworthy, such as moving closer to get a better look, measuring something three times and taking the average, and checking what one thinks one is observing with someone else who is in a good position to observe it. It also helps to be skilled at recognizing respects in which one’s report of one’s observation involves inference rather than direct observation, so that one can then consider whether the inference is justified. These abilities come into play as well when one thinks about whether and with what degree of confidence to accept an observation report, for example in the study of history or in a criminal investigation or in assessing news reports. Observational abilities show up in some lists of critical thinking abilities (Ennis 1962: 90; Facione 1990a: 16; Ennis 1991: 9). There are items testing a person’s ability to judge the credibility of observation reports in the Cornell Critical Thinking Tests, Levels X and Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005). Norris and King (1983, 1985, 1990a, 1990b) is a test of ability to appraise observation reports.

Emotional abilities : The emotions that drive a critical thinking process are perplexity or puzzlement, a wish to resolve it, and satisfaction at achieving the desired resolution. Children experience these emotions at an early age, without being trained to do so. Education that takes critical thinking as a goal needs only to channel these emotions and to make sure not to stifle them. Collaborative critical thinking benefits from ability to recognize one’s own and others’ emotional commitments and reactions.

Questioning abilities : A critical thinking process needs transformation of an inchoate sense of perplexity into a clear question. Formulating a question well requires not building in questionable assumptions, not prejudging the issue, and using language that in context is unambiguous and precise enough (Ennis 1962: 97; 1991: 9).

Imaginative abilities : Thinking directed at finding the correct causal explanation of a general phenomenon or particular event requires an ability to imagine possible explanations. Thinking about what policy or plan of action to adopt requires generation of options and consideration of possible consequences of each option. Domain knowledge is required for such creative activity, but a general ability to imagine alternatives is helpful and can be nurtured so as to become easier, quicker, more extensive, and deeper (Dewey 1910: 34–39; 1933: 40–47). Facione (1990a) and Halpern (1998) include the ability to imagine alternatives as a critical thinking ability.

Inferential abilities : The ability to draw conclusions from given information, and to recognize with what degree of certainty one’s own or others’ conclusions follow, is universally recognized as a general critical thinking ability. All 11 examples in section 2 of this article include inferences, some from hypotheses or options (as in Transit , Ferryboat and Disorder ), others from something observed (as in Weather and Rash ). None of these inferences is formally valid. Rather, they are licensed by general, sometimes qualified substantive rules of inference (Toulmin 1958) that rest on domain knowledge—that a bus trip takes about the same time in each direction, that the terminal of a wireless telegraph would be located on the highest possible place, that sudden cooling is often followed by rain, that an allergic reaction to a sulfa drug generally shows up soon after one starts taking it. It is a matter of controversy to what extent the specialized ability to deduce conclusions from premisses using formal rules of inference is needed for critical thinking. Dewey (1933) locates logical forms in setting out the products of reflection rather than in the process of reflection. Ennis (1981a), on the other hand, maintains that a liberally-educated person should have the following abilities: to translate natural-language statements into statements using the standard logical operators, to use appropriately the language of necessary and sufficient conditions, to deal with argument forms and arguments containing symbols, to determine whether in virtue of an argument’s form its conclusion follows necessarily from its premisses, to reason with logically complex propositions, and to apply the rules and procedures of deductive logic. Inferential abilities are recognized as critical thinking abilities by Glaser (1941: 6), Facione (1990a: 9), Ennis (1991: 9), Fisher & Scriven (1997: 99, 111), and Halpern (1998: 452). Items testing inferential abilities constitute two of the five subtests of the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (Watson & Glaser 1980a, 1980b, 1994), two of the four sections in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test Level X (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005), three of the seven sections in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005), 11 of the 34 items on Forms A and B of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (Facione 1990b, 1992), and a high but variable proportion of the 25 selected-response questions in the Collegiate Learning Assessment (Council for Aid to Education 2017).

Experimenting abilities : Knowing how to design and execute an experiment is important not just in scientific research but also in everyday life, as in Rash . Dewey devoted a whole chapter of his How We Think (1910: 145–156; 1933: 190–202) to the superiority of experimentation over observation in advancing knowledge. Experimenting abilities come into play at one remove in appraising reports of scientific studies. Skill in designing and executing experiments includes the acknowledged abilities to appraise evidence (Glaser 1941: 6), to carry out experiments and to apply appropriate statistical inference techniques (Facione 1990a: 9), to judge inductions to an explanatory hypothesis (Ennis 1991: 9), and to recognize the need for an adequately large sample size (Halpern 1998). The Cornell Critical Thinking Test Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005) includes four items (out of 52) on experimental design. The Collegiate Learning Assessment (Council for Aid to Education 2017) makes room for appraisal of study design in both its performance task and its selected-response questions.

Consulting abilities : Skill at consulting sources of information comes into play when one seeks information to help resolve a problem, as in Candidate . Ability to find and appraise information includes ability to gather and marshal pertinent information (Glaser 1941: 6), to judge whether a statement made by an alleged authority is acceptable (Ennis 1962: 84), to plan a search for desired information (Facione 1990a: 9), and to judge the credibility of a source (Ennis 1991: 9). Ability to judge the credibility of statements is tested by 24 items (out of 76) in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test Level X (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005) and by four items (out of 52) in the Cornell Critical Thinking Test Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005). The College Learning Assessment’s performance task requires evaluation of whether information in documents is credible or unreliable (Council for Aid to Education 2017).