More From Forbes

The role of research at universities: why it matters.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

(Photo by William B. Plowman/Getty Images)

Teaching and learning, research and discovery, synthesis and creativity, understanding and engagement, service and outreach. There are many “core elements” to the mission of a great university. Teaching would seem the most obvious, but for those outside of the university, “research” (taken to include scientific research, scholarship more broadly, as well as creative activity) may be the least well understood. This creates misunderstanding of how universities invest resources, especially those deriving from undergraduate tuition and state (or other public) support, and the misperception that those resources are being diverted away from what is believed should be the core (and sole) focus, teaching. This has led to a loss of trust, confidence, and willingness to continue to invest or otherwise support (especially our public) universities.

Why are universities engaged in the conduct of research? Who pays? Who benefits? And why does it all matter? Good questions. Let’s get to some straightforward answers. Because the academic research enterprise really is not that difficult to explain, and its impacts are profound.

So let’s demystify university-based research. And in doing so, hopefully we can begin building both better understanding and a better relationship between the public and higher education, both of which are essential to the future of US higher education.

Why are universities engaged in the conduct of research?

Universities engage in research as part of their missions around learning and discovery. This, in turn, contributes directly and indirectly to their primary mission of teaching. Universities and many colleges (the exception being those dedicated exclusively to undergraduate teaching) have as part of their mission the pursuit of scholarship. This can come in the form of fundamental or applied research (both are most common in the STEM fields, broadly defined), research-based scholarship or what often is called “scholarly activity” (most common in the social sciences and humanities), or creative activity (most common in the arts). Increasingly, these simple categorizations are being blurred, for all good reasons and to the good of the discovery of new knowledge and greater understanding of complex (transdisciplinary) challenges and the creation of increasingly interrelated fields needed to address them.

It goes without saying that the advancement of knowledge (discovery, innovation, creation) is essential to any civilization. Our nation’s research universities represent some of the most concentrated communities of scholars, facilities, and collective expertise engaged in these activities. But more importantly, this is where higher education is delivered, where students develop breadth and depth of knowledge in foundational and advanced subjects, where the skills for knowledge acquisition and understanding (including contextualization, interpretation, and inference) are honed, and where students are educated, trained, and otherwise prepared for successful careers. Part of that training and preparation derives from exposure to faculty who are engaged at the leading-edge of their fields, through their research and scholarly work. The best faculty, the teacher-scholars, seamlessly weave their teaching and research efforts together, to their mutual benefit, and in a way that excites and engages their students. In this way, the next generation of scholars (academic or otherwise) is trained, research and discovery continue to advance inter-generationally, and the cycle is perpetuated.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

University research can be expensive, particularly in laboratory-intensive fields. But the responsibility for much (indeed most) of the cost of conducting research falls to the faculty member. Faculty who are engaged in research write grants for funding (e.g., from federal and state agencies, foundations, and private companies) to support their work and the work of their students and staff. In some cases, the universities do need to invest heavily in equipment, facilities, and personnel to support select research activities. But they do so judiciously, with an eye toward both their mission, their strategic priorities, and their available resources.

Medical research, and medical education more broadly, is expensive and often requires substantial institutional investment beyond what can be covered by clinical operations or externally funded research. But universities with medical schools/medical centers have determined that the value to their educational and training missions as well as to their communities justifies the investment. And most would agree that university-based medical centers are of significant value to their communities, often providing best-in-class treatment and care in midsize and smaller communities at a level more often seen in larger metropolitan areas.

Research in the STEM fields (broadly defined) can also be expensive. Scientific (including medical) and engineering research often involves specialized facilities or pieces of equipment, advanced computing capabilities, materials requiring controlled handling and storage, and so forth. But much of this work is funded, in large part, by federal agencies such as the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Energy, US Department of Agriculture, and many others.

Research in the social sciences is often (not always) less expensive, requiring smaller amount of grant funding. As mentioned previously, however, it is now becoming common to have physical, natural, and social scientist teams pursuing large grant funding. This is an exciting and very promising trend for many reasons, not the least of which is the nature of the complex problems being studied.

Research in the arts and humanities typically requires the least amount of funding as it rarely requires the expensive items listed previously. Funding from such organizations as the National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, and private foundations may be able to support significant scholarship and creation of new knowledge or works through much more modest grants than would be required in the natural or physical sciences, for example.

Philanthropy may also be directed toward the support of research and scholarly activity at universities. Support from individual donors, family foundations, private or corporate foundations may be directed to support students, faculty, labs or other facilities, research programs, galleries, centers, and institutes.

Who benefits?

Students, both undergraduate and graduate, benefit from studying in an environment rich with research and discovery. Besides what the faculty can bring back to the classroom, there are opportunities to engage with faculty as part of their research teams and even conduct independent research under their supervision, often for credit. There are opportunities to learn about and learn on state-of-the-art equipment, in state-of-the-art laboratories, and from those working on the leading edge in a discipline. There are opportunities to co-author, present at conferences, make important connections, and explore post-graduate pathways.

The broader university benefits from active research programs. Research on timely and important topics attracts attention, which in turn leads to greater institutional visibility and reputation. As a university becomes known for its research in certain fields, they become magnets for students, faculty, grants, media coverage, and even philanthropy. Strength in research helps to define a university’s “brand” in the national and international marketplace, impacting everything from student recruitment, to faculty retention, to attracting new investments.

The community, region, and state benefits from the research activity of the university. This is especially true for public research universities. Research also contributes directly to economic development, clinical, commercial, and business opportunities. Resources brought into the university through grants and contracts support faculty, staff, and student salaries, often adding additional jobs, contributing directly to the tax base. Research universities, through their expertise, reputation, and facilities, can attract new businesses into their communities or states. They can also launch and incubate startup companies, or license and sell their technologies to other companies. Research universities often host meeting and conferences which creates revenue for local hotels, restaurants, event centers, and more. And as mentioned previously, university medical centers provide high-quality medical care, often in midsize communities that wouldn’t otherwise have such outstanding services and state-of-the-art facilities.

(Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

And finally, why does this all matter?

Research is essential to advancing society, strengthening the economy, driving innovation, and addressing the vexing and challenging problems we face as a people, place, and planet. It’s through research, scholarship, and discovery that we learn about our history and ourselves, understand the present context in which we live, and plan for and secure our future.

Research universities are vibrant, exciting, and inspiring places to learn and to work. They offer opportunities for students that few other institutions can match – whether small liberal arts colleges, mid-size teaching universities, or community colleges – and while not right for every learner or every educator, they are right for many, if not most. The advantages simply cannot be ignored. Neither can the importance or the need for these institutions. They need not be for everyone, and everyone need not find their way to study or work at our research universities, and we stipulate that there are many outstanding options to meet and support different learning styles and provide different environments for teaching and learning. But it’s critically important that we continue to support, protect, and respect research universities for all they do for their students, their communities and states, our standing in the global scientific community, our economy, and our nation.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

Why Do We Research?

If you are reading this post, you are likely involved in research. Unsurprisingly, I am too. Yes, I’ve spent my fair share of long nights on the A floor of Firestone, reviewing sources and tightening up arguments. This week, I’m embarking on a new history research paper about the evolution of Native American spirituality from the 1830s to the 1890s, which I anticipate will take a fair amount of time. Reflecting on the work I have ahead got me thinking, why am I doing this in the first place? In fact, why do any of us research?

This question can really be broken into two parts: “What do we hope to achieve from our research?” and “What motivates us to conduct our research?” We think about the first question often, because in the academy, we have to justify what we’re doing to our professors, to funding boards, etc. And in lots of research, one’s answer to the first question informs their answer to the second. Certain biologist friends of mine, for instance, study lab rat carcasses in the hopes of better understanding tumors, with the inspiring goal of curing cancer. In cases such as this, the aim of a project is to arrive at something with a concrete application so marvelous that it motivates the researcher to come to the lab each morning.

Similarly, in the social sciences, the motivating goal of research is societal optimization. Economists strive to understand how we as individuals, firms, and nations can most efficiently allocate our scarce resources to make the most of this precious life. Psychologists and sociologists analyze human motivations and behaviors, so that we can understand how we function and organize our lives accordingly. And, many political scientists and public policy researchers study our laws and systems of government with an eye toward tackling problems and implementing concrete solutions. Again, the noble aims of such research provide the motivation necessary to conduct it.

But what about research in the humanities? This realm of inquiry does not seem to concern itself with the material or technological advancement of humanity–the ‘goal’ is less tangible. This brings us back to the second overall question posed at the beginning of this post: w hat motivates us to conduct humanities research?

Research can be goal-oriented, as discussed previously, or grounded in the process. Humanities research is often the latter: we hope to gain a personal appreciation for the immense value and power of ideas. The notion of truth- seeking , a common justification for more theoretical research, implies the high value of the truth being sought —after all, we wouldn’t spend long hours in the library “seeking the truth” if we didn’t think it’d be worth it in the end.

Regardless of our end goal (or lack thereof), rewards are built into the research process. Before we can research, we must learn about our subject area. In the case of my history paper, I received background information on Native American life in the 1800s through lectures from various historians. Grappling with their ideas, a vital part of my research, has been both a challenge and a reward. Indeed, as I learned while researching for this article, new findings in psychology suggest that learning makes humans happier . So, next time you’re dreading working on a research paper, try to remember that you’ll learn something, which will make you happier!

Finally, in addition to making us happier or providing us with a personal sense of meaning, research also expresses something about who we are as a scholarly community. Research is a collective enterprise, and thus everything we do as researchers exists in the context of our fellow researchers–who are often attached to universities. As participants in the university system, we are at the forefront a collaborative, decentralized experiment in personal freedom of thought and action dating back to the 13 th century . This is just as true in the humanities as it is in the hard or social sciences, as we have a shared desire to bring the best ideas of humankind to light. And I think that’s pretty cool.

We all have our own private reasons for researching, too. As a student of history interested in public service, I hope to learn from the mistakes of the past by studying the intricacies of their causes and effects. The United States’ policies towards Native Americans in the 1800s were, in general, morally abhorrent–so studying them is actually a useful exercise in learning how not to conduct public policy. I encourage my fellow Princeton students to devote some time to thinking about the “big picture” of their research, also keeping in mind what we’re participating in as a social movement and why it matters. After all, the grades we receive on our research papers will soon fade from our memories—but these feelings of purpose, meaning, and connection to the academic tradition will be with us forever.

–Shanon FitzGerald, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

What Is Research and Why We Do It

- First Online: 23 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Carlo Ghezzi 2

3030 Accesses

2 Altmetric

The notions of science and scientific research are discussed and the motivations for doing research are analyzed. Research can span a broad range of approaches, from purely theoretical to practice-oriented; different approaches often coexist and fertilize each other. Research ignites human progress and societal change. In turn, society drives and supports research. The specific role of research in Informatics is discussed. Informatics is driving the current transition towards the new digital society in which we will live in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

In [ 34 ], P.E. Medawar discusses what he calls the “snobismus” of pure versus applied science. In his words, this is one of the most damaging forms of snobbism, which draws a class distinction between pure and applied science.

Originality, rigor, and significance have been defined and used as the key criteria to evaluate research outputs by the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) [ 46 ]. A research evaluation exercise has been performed periodically since 1986 on UK higher education institutions and their research outputs have been rated according to their originality, rigor, and significance.

The importance of realizing that “we don’t know” was apparently first stated by Socrates, according to Plato’s account of his thought. This is condensed in the famous paradox “I know that I don’t know.”

This view applies mainly to natural and physical sciences.

Roy Amara was President of the Institute for Future, a USA-based think tank, from 1971 until 1990.

The Turing Award is generally recognized as the Nobel prize of Informatics.

See http://uis.unesco.org/apps/visualisations/research-and-development-spending/ .

Israel is a very good example. Investments in research resulted in a proliferation of new, cutting-edge enterprises. The term start-up nation has been coined by Dan Senor and Saul Singer in their successful book [ 51 ] to characterize this phenomenon.

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/societal-challenges .

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/cross-cutting-activities-focus-areas .

This figure has been adapted from a presentation by A. Fuggetta, which describes the mission of Cefriel, an Italian institution with a similar role of Fraunhofer, on a smaller scale.

The ERC takes an ecumenical approach and calls the research sector “Computer Science and Informatics.”

I discuss here the effect of “big data” on research, although most sectors of society—industry, finance, health, …—are also deeply affected.

Carayannis, E., Campbell, D.: Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems. In: E. Carayannis, D. Campbell (eds.) Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems: 21st-Century Democracy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship for Development. SpringerBriefs in Business, New York, NY (2012)

Google Scholar

Etzkowitz, H., Leydesdorff, L.: The triple helix – university-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Review 14 (1), 14–19 (1995)

Harari, Y.: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Random House (2014). URL https://books.google.it/books?id=1EiJAwAAQBAJ

Harari, Y.: Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. Random House (2016). URL https://books.google.it/books?id=dWYyCwAAQBAJ

Hopcroft, J.E., Motwani, R., Ullman, J.D.: Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd Edition). Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., USA (2006)

MATH Google Scholar

Medawar, P.: Advice To A Young Scientist. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation series. Basic Books (2008)

OECD: Frascati Manual. OECD Publishing (2015). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239012-en . URL https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264239012-en

REF2019/2: Panel criteria and working methods (2019). URL https://www.ref.ac.uk/media/1084/ref-2019_02-panel-criteria-and-working-methods.pdf

Senor, D., Singer, S.: Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle. McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, Canada (2011)

Stokes, D.E.: Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C. (1997)

Thurston, R.H.: The growth of the steam engine. Popular Science Monthly 12 (1877)

Vardi, M.Y.: The long game of research. Commun. ACM 62 (9), 7–7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3352489 . URL http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3352489

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Carlo Ghezzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlo Ghezzi .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ghezzi, C. (2020). What Is Research and Why We Do It. In: Being a Researcher. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_1

Published : 23 June 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-45156-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-45157-8

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A question universities need to answer: why do we research?

Philosopher, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

John Armstrong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Fundamentally, there are two big motives for research.

On the on hand there is intellectual ambition: the desire to know and understand the word, to appreciate the best that has been said and thought on the topics that grip our imaginations.

In one of C.P. Snow ’s Cambridge novels there’s an elderly character who looks back on his early days working under the chemist and physicist, Ernest Rutherford . “We used to run to our laboratories” he says. They were running because of the immense excitement of the discoveries that were unfolding.

I used to look with an almost physical longing at books in the philosophy section of the library – desperate to get to grips with the glory of the ideas they contained.

Sometimes we call this “blue sky” or “fundamental” research. But, in a crucial way, what is at stake is the love and devotion brought to certain questions by (at present) a relatively small number of people.

Many more people would like to be involved in such work than we are, as a society, willing to pay for. I’ve lost count of the number of people who have told me that they would like to have a job in which they spent their time studying manuscripts or on archaeological digs or mapping the heavens or speculating on the ultimate nature of good and evil.

While, in fact, they work as public servants, lawyers, estate agents, school teachers, logistics managers, sales representatives and so on.

It may sound a bit crude to put it this way, but we should look at the issue for what it is: there is not enough demand for such research. That is, there are not enough sources of financial input to support these kinds of desired roles.

This raises the first great question that any serious debate about research must address: if you don’t engage ambitiously with markets or public opinion, how will you actually pay for the research you want to undertake?

Understandably we like to suppose that “government” in some form or another will meet the cost. But this in only to put the question one step further back. What kind of politics would we need to have for governments actually to direct resources in this way?

Clearly, relatively affluent countries spend large sums of money on all kinds of things. Why not on the love of knowledge for its own sake?

This is a tantalising question. It’s tempting to answer it in moral terms. One wants to explain why it is lovely and good and in the long-term national interest to support open-ended intellectual ambition.

But the question is not: would that be good and lovely? The question is: what would have to be the case for such a line of argument to be compelling to government?

There are many potential goods in the world that never come to fruition. And it is fair to say that we are, at present, very far from having a political or national culture in which such arguments would look powerful. It’s no help blaming other people. That gets us no closer to a good outcome.

The deep issue is this: fundamental and blue-sky research (research undertaken for the love of knowledge and from motives of sheer intellectual ambition) is possible on a large scale only with the profound consent of a whole society.

And universities – which are the natural homes of intellectual ambition – are not organised to secure this consent. Those who are fired by the love of knowledge do not see securing such support as fundamental to what they do.

And at an individual level, of course, the task belongs to no particular person. Yet, if we are to carry off the huge task of gaining such committed and widespread support we would have to devote ourselves to a vast project of engagement. We would have to have this task written into the DNA of research culture.

And this is the fateful irony. The motive of intellectual ambition very often goes alongside indifference to public opinion, lack of concern with buy-in from the wider world, hostility to winning over hearts and minds in large numbers.

We want the support that requires a great public but we don’t want to do the things that would win the loyalty of a great public. At worst, we want to demonise the philistines and have their taxes pay for our noble enthusiasms.

I mentioned that there were two motives for research. Aside from the pure pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, research is linked to problem solving. What this means is the solving of other people’s problems. That is, what other people experience as problems.

It starts with a tenderness and ambition that is directed at the needs of others – as they recognise and acknowledge those needs. This is, in effect, entry into a market place. Much research, of course, is conducted in precisely this way beyond the walls of the academy.

And this gives rise to the second great question that universities face with respect to research. If universities devote more of their energies to engagement with markets and public opinion, how will they retain a sense of noble mission – which is one of their defining characteristics? What would the institutions need to be like to carry this off?

My concern at this stage is not to provide a precise answer to either of the great questions. Rather, what I want is to get clear about the questions we really do have to address. That is, the questions that should be central to the debate.

Fundamentally, we are trying to explain to ourselves why research is good and how research will be paid for. Our danger is in asking and answering these questions independently.

We could have a fine account of why research is noble, but fail because we could not work out how to bring this to fruition in the world. Or we could have an account of how to make research pay but fail because we missed the whole point: which is that research is a noble human undertaking.

But not nearly enough people seem to be interested in answering both questions at the same time.

I believe that it is possible to integrate the two demands. And, in fact, that it is a central task of education and of culture to achieve such integration.

Our epochal task is to make our best ideals powerful in the world we happen to have. We must not be Jacobites: devotees of a gracious but lost cause. To avoid that fate we have to think about love and money at the same time. We have to answer the two great questions.

- Research funding

- Universities

Sydney Horizon Educators – Faculty of Engineering (Targeted)

Dean, Faculty of Education

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Social Media Producer

PhD Scholarship

5 Reasons Why Undergraduates Should Do Research

- by Julia Ann Easley

- May 02, 2017

Nearly 40 percent of UC Davis undergraduates participate in hands-on research. On the occasion of the 28th annual Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creative Activities Conference on April 28 and 29 — where more than 700 students presented their work — we introduce you to some students and graduates who shared what they’ve gained. Consider how the research experience can benefit you, too.

1. Exploring career directions

Here is how undergraduate research influenced the direction of three UC Davis students:

Shadd Cabalatungan started his studies at UC Davis aiming for a career as a veterinarian. Touched by his aunt’s diagnosis with breast cancer, he got involved with research at the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center . That experience was key in changing his direction to pursue a medical degree. He also did research on how drinking by college students affects others who don’t drink. With a degree in sociology , he is now completing his first year as a medical student at Stony Brook University.

Graduating senior Rong Ben, once fascinated by the aesthetics of fashion, is geeking out on how technology can be incorporated so fashion helps solve problems. As a junior, this design major did a research internship with a professor working on wearable technology, including gloves to provide a patient’s vital statistics. “It opened up a new view for me,” said Ben. As a participant in the University Honors Program , Ben designed a grab-and-go coat for safety in an earthquake with protective materials, lighting, emergency food and water, and more. Next up for Ben: the graduate program in fashion enterprise and society at the University of Leeds.

Physics major Mario D’Andrea took a course related to climate neutrality to confirm his desire to study physics in graduate school. He worked with two other students to research waste reduction and carbon sequestration through composting. He enjoyed the research, and it helped confirm his desire to study condensed matter physics in graduate school. “I wish more classes were open-ended like this,” he said.

2. Building transferable skills and enhancing resumes

Graduating senior Julie Beppler has learned a lot about food options in downtown Davis. The managerial economics major analyzed how 49 restaurants use menu design to promote certain items. But more than that, she developed and demonstrated skills that employers seek. Beppler first worked as a research assistant and then pursued this project for her Undergraduate Honors Thesis . It focuses on the cost of production and price of featured menu items as well as their relative healthiness. She taught herself computer programing; learned time management; practiced professional communications as she interacted with restaurant managers; and proved her ability to motivate herself and direct her own work.

Beppler will soon start in the management development program at E. & J. Gallo Winery, so take her word that doing research can also help students find a mentor who can provide letters of recommendation and advice to support their success. Kristin Kiesel , a faculty member in agricultural and resource economics and a mentor to Beppler, agreed: “There is no better way to recommend a student than by having them successfully complete an undergraduate research project.”

3. Learning to publicly advocate for and defend work

“Nerve wracking.” That’s how graduating senior Kathryn Green described her anticipation of presenting for the first time her research on California’s clean car consumer rebate program. Now she’s a UC undergraduate research ambassador. Last quarter, the political science major participated in the policy program at the UC Center Sacramento , which included classes, an internship with the advocacy organization Environment California and a research project.

Presenting the research was a requirement. Green designed a large poster representing her research and, in a session lasting 90 minutes, explained it one-on-one to attendees. She talked about the process and her policy recommendations not only to policymakers and people from the clean car industry, but also to others who were unfamiliar with the topic. “I became almost a teacher,” said Green. “I took my research and explained it to someone who didn’t know about it.”

Based on her success in that venue, Green represented UC Davis at showcase in Los Angeles earlier in April for alumni, donors, regents and other friends of the University of California. “I’m really proud I got to go down and share my research,” she said.

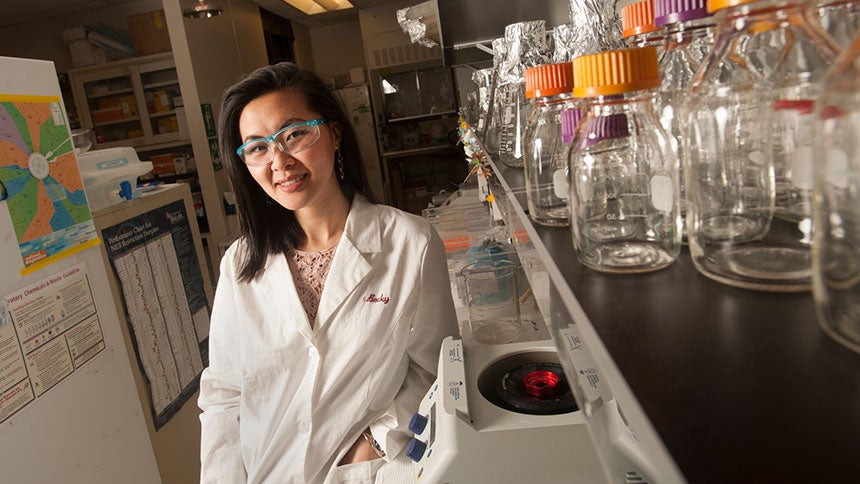

4. Getting a leg up on graduate or professional school

When Becky Fu came to UC Davis in 2008, she was the first in her family to attend college. Nine years later, this genetics and genomics major is preparing to defend her dissertation and graduate from Stanford University with a doctoral degree in genetics and a master’s degree in biomedical informatics. A 2012 graduate from UC Davis, she credits her participation in undergraduate research as foundational to where she is today. “No question about it,” she said. “Without undergraduate research, there would have been no way I got into any of the graduate programs I did.”

As a freshman, Fu heard others talking about research and sought out the Undergraduate Research Center on campus for more information. She went on to do research with two professors; participate in the undergraduate research conference ; publish in Explorations , the UC Davis journal of undergraduate research; be awarded a Provost’s Undergraduate Fellowship to help pay for her research; and win the Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Research and other awards.

“Having that experience as an undergraduate to fail a lot and expand on the techniques,” Fu said, “was an integral part of being prepared for and getting through the doctoral program.” At Stanford, she is working in the lab of Andrew Fire, who shared the 2006 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine .

5. Contributing knowledge and impacting the world

Annaliese Franz, associate professor of chemistry and faculty director of the Undergraduate Research Center , sees students experience the joy of discovery and creation through research. “Students really get the chance to create something new as they go into the lab or out into the field or study new policy.”

Fu, the Stanford student, explained how undergraduate research developed a new quest for her: “I wanted to be contributing to a bigger cause, a bigger realm of intelligence, and that’s advancing medical care in general.”

And Green, who did the research on the clean-car rebate program, discovered a new power. “My research told me that an undergraduate can make an impact,” she said. “You don’t have to have a master’s degree or doctorate to make valuable contributions.”

Julia Ann Easley of News and Media Relations supports communication and writes stories at the heart of the university. Her career includes a noble cause, adventures in learning, working with wonderful people and a beautiful green setting.

Subscribe to our majors blog

Primary Category

- Board Members

- Management Team

- Become a Contributor

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Code of Ethical Practices

KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

- Search Engines List

- Suggested Reading Library

- Web Directories

- Research Papers

- Industry News

- Become a Member

- Associate Membership

- Certified Membership

- Membership Application

- Corporate Application

- CIRS Certification Program

- CIRS Certification Objectives

- CIRS Certification Benefits

- CIRS Certification Exam

- Maintain Your Certification

- Upcoming Events

- Live Classes

- Classes Schedule

- Webinars Schedules

- Latest Articles

- Internet Research

- Search Techniques

- Research Methods

- Business Research

- Search Engines

- Research & Tools

- Investigative Research

- Internet Search

- Work from Home

- Internet Ethics

- Internet Privacy

Six Reasons Why Research is Important

Everyone conducts research in some form or another from a young age, whether news, books, or browsing the Internet. Internet users come across thoughts, ideas, or perspectives - the curiosity that drives the desire to explore. However, when research is essential to make practical decisions, the nature of the study alters - it all depends on its application and purpose. For instance, skilled research offered as a research paper service has a definite objective, and it is focused and organized. Professional research helps derive inferences and conclusions from solving problems. visit the HB tool services for the amazing research tools that will help to solve your problems regarding the research on any project.

What is the Importance of Research?

The primary goal of the research is to guide action, gather evidence for theories, and contribute to the growth of knowledge in data analysis. This article discusses the importance of research and the multiple reasons why it is beneficial to everyone, not just students and scientists.

On the other hand, research is important in business decision-making because it can assist in making better decisions when combined with their experience and intuition.

Reasons for the Importance of Research

- Acquire Knowledge Effectively

- Research helps in problem-solving

- Provides the latest information

- Builds credibility

- Helps in business success

- Discover and Seize opportunities

1- Acquire Knowledge Efficiently through Research

The most apparent reason to conduct research is to understand more. Even if you think you know everything there is to know about a subject, there is always more to learn. Research helps you expand on any prior knowledge you have of the subject. The research process creates new opportunities for learning and progress.

2- Research Helps in Problem-solving

Problem-solving can be divided into several components, which require knowledge and analysis, for example, identification of issues, cause identification, identifying potential solutions, decision to take action, monitoring and evaluation of activity and outcomes.

You may just require additional knowledge to formulate an informed strategy and make an informed decision. When you know you've gathered reliable data, you'll be a lot more confident in your answer.

3- Research Provides the Latest Information

Research enables you to seek out the most up-to-date facts. There is always new knowledge and discoveries in various sectors, particularly scientific ones. Staying updated keeps you from falling behind and providing inaccurate or incomplete information. You'll be better prepared to discuss a topic and build on ideas if you have the most up-to-date information. With the help of tools and certifications such as CIRS , you may learn internet research skills quickly and easily. Internet research can provide instant, global access to information.

4- Research Builds Credibility

Research provides a solid basis for formulating thoughts and views. You can speak confidently about something you know to be true. It's much more difficult for someone to find flaws in your arguments after you've finished your tasks. In your study, you should prioritize the most reputable sources. Your research should focus on the most reliable sources. You won't be credible if your "research" comprises non-experts' opinions. People are more inclined to pay attention if your research is excellent.

5- Research Helps in Business Success

R&D might also help you gain a competitive advantage. Finding ways to make things run more smoothly and differentiate a company's products from those of its competitors can help to increase a company's market worth.

6- Research Discover and Seize Opportunities

People can maximize their potential and achieve their goals through various opportunities provided by research. These include getting jobs, scholarships, educational subsidies, projects, commercial collaboration, and budgeted travel. Research is essential for anyone looking for work or a change of environment. Unemployed people will have a better chance of finding potential employers through job advertisements or agencies.

How to Improve Your Research Skills

Start with the big picture and work your way down.

It might be hard to figure out where to start when you start researching. There's nothing wrong with a simple internet search to get you started. Online resources like Google and Wikipedia are a great way to get a general idea of a subject, even though they aren't always correct. They usually give a basic overview with a short history and any important points.

Identify Reliable Source

Not every source is reliable, so it's critical that you can tell the difference between the good ones and the bad ones. To find a reliable source, use your analytical and critical thinking skills and ask yourself the following questions: Is this source consistent with other sources I've discovered? Is the author a subject matter expert? Is there a conflict of interest in the author's point of view on this topic?

Validate Information from Various Sources

Take in new information.

The purpose of research is to find answers to your questions, not back up what you already assume. Only looking for confirmation is a minimal way to research because it forces you to pick and choose what information you get and stops you from getting the most accurate picture of the subject. When you do research, keep an open mind to learn as much as possible.

Facilitates Learning Process

Learning new things and implementing them in daily life can be frustrating. Finding relevant and credible information requires specialized training and web search skills due to the sheer enormity of the Internet and the rapid growth of indexed web pages. On the other hand, short courses and Certifications like CIRS make the research process more accessible. CIRS Certification offers complete knowledge from beginner to expert level. You can become a Certified Professional Researcher and get a high-paying job, but you'll also be much more efficient and skilled at filtering out reliable data. You can learn more about becoming a Certified Professional Researcher.

Stay Organized

You'll see a lot of different material during the process of gathering data, from web pages to PDFs to videos. You must keep all of this information organized in some way so that you don't lose anything or forget to mention something properly. There are many ways to keep your research project organized, but here are a few of the most common: Learning Management Software , Bookmarks in your browser, index cards, and a bibliography that you can add to as you go are all excellent tools for writing.

Make Use of the library's Resources

If you still have questions about researching, don't worry—even if you're not a student performing academic or course-related research, there are many resources available to assist you. Many high school and university libraries, in reality, provide resources not only for staff and students but also for the general public. Look for research guidelines or access to specific databases on the library's website. Association of Internet Research Specialists enjoys sharing informational content such as research-related articles , research papers , specialized search engines list compiled from various sources, and contributions from our members and in-house experts.

of Conducting Research

Latest from erin r. goodrich.

- Enhancing Efficiency: The Role of Technology in Personal Injury Case Management

- The Evolution and Future of Workplace Benefit Administration

- 10 Best People Search Engines and Websites in 2022

Live Classes Schedule

- JUN 14 CIRS Certification Internet Research Training Program Live Classes Online

- JUN 14 Web Search Methods & Techniques Live Training Live Classes Online

World's leading professional association of Internet Research Specialists - We deliver Knowledge, Education, Training, and Certification in the field of Professional Online Research. The AOFIRS is considered a major contributor in improving Web Search Skills and recognizes Online Research work as a full-time occupation for those that use the Internet as their primary source of information.

Get Exclusive Research Tips in Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Advertising Opportunities

- Knowledge Network

- Youth Program

- Wharton Online

Why should you do research as an undergraduate?

Alumni, faculty, and employers answer the question., erika james, dean, the wharton school; reliance professor of management and private enterprise.

When I was a student, I took a short detour to a corporate setting, which was an experience that only reinforced my belief that my true calling was in academia. The lasting professional and personal relationships I have developed through my research have proven to be invaluable, and transformed my life in many ways. Though not every student will pursue a career in academia, all students can benefit greatly from the skills gained through research. The experience will prepare you to think critically, anticipate opportunities and be an effective leader in any industry or endeavor.

Diana Roberson, Vice Dean, Wharton Undergraduate Division; Samuel A. Blank Professor of Legal Studies & Business Ethics

Raveen Kariyawasam, W’22, SEAS’22

Adam Grant, Saul P. Steinberg Professor of Management, Professor of Psychology

I can’t imagine a better way to learn than doing undergraduate research. When I was in college, getting involved in research changed the course of my life. It gave me the chance to explore fascinating questions, soak up wisdom from brilliant mentors, and stretch my creative and critical thinking muscles. I discovered that I loved creating knowledge, not just consuming it.

Dara Cook, W’95

Wendy De La Rosa, Assistant Professor of Marketing

So many consumers, cultures, and organizations have been ignored and under-researched. As a result, so much is still unknown. For me, there is nothing more honorable than being the person who pushes our collective human knowledge forward (even if it is just by a centimeter). You can be that person, and you can start right now, right here at Penn.

Michael Roberts, William H. Lawrence Professor of Finance

Nancy Zhang, Professor of Statistics and Data Science, Vice Dean of Wharton Doctoral Programs

Geoffrey Garrett, Former Dean and Reliance Professor of Management and Private Enterprise, The Wharton School

Debi Ogunrinde, C’16, W’16

Paul Karner, C’03, W’03

Ashish Shah, W’92

My undergrad experience prepared me for success in a crisis that few expected and fewer were prepared for. When at Wharton, I was fortunate enough to conduct research in two completely different areas of finance. Read more

Kate Lakin, Putnam Investments

Julio Reynaga, C’13, W’13

Katherina M. Rosqueta, WG’01, Founding Executive Director, Center for High Impact Philanthropy, University of Pennsylvania

Joseph Wang, C’13, W’13

Nada Boualam, C’17, W’17

- Oxford Review /

Research quality – not all research is good research, but how do you tell?

- in Blog , Evidence-Based Practice , Oxford Review , Research by David Wilkinson

- “Research says…”

“Research says…”, but does it? How to tell how good a study is. Research quality is an important factor in deciding to use a study but how do you know how good a particular bit of research really is?

Science proves nothing

There are lots of factors that influence things, science is useless, how it works, confirmation bias, how to tell how good a piece of research is, the 4 levels of evidence, the 5 grade domains , risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias, what we are looking for, example review panel, citing evidence, other references used.

Lots of people like quoting research. Usually the quote is vague, something like “There is a study that proves x”. There are a number of problems with using research in this way. The first and most obvious issue here is ‘what research’? A vague reference to some study could refer to a 4 th grade children’s school project, someone’s ideas written on the back of an envelope or a major international study conducted by subject matter experts and professional researchers. There is usually no way of telling what the research quality is until we know which study it actually is, how the research was conducted and by whom.

For example there is a big difference in research quality between a study that interviews 5 people in the same office and a study that observes the actual behaviour of 2,000 employees over time and not what they tell you their behaviour is.

The other issue here is the idea that research is there to ‘prove’ things. It isn’t. It is trying to get to as close to the truth about a particular topic as possible, but that is very different to ‘proving something to be true’. To say something has been ‘proved’ means that there is no doubt left, that this is the truth.

Science doesn’t work like that [i] . Life is complex. There are rarely simple causes of things and finding real causal relationships is notoriously hard. For example, ‘smoking causes lung cancer’. Firstly, not everyone who smokes will get lung cancer. There are other factors which, when combined with smoking, make the chances of developing cancer more or less likely, like excessive drinking, exercise, living in a polluted environment, having a diet of fast food and fizzy drinks etc. Some people have a greater genetic susceptibility to the carcinogens contained in smoke than others. Even then, all the smoke does is to help to create the conditions within the lungs that start changes in the person’s physiology that can then result in cancer. Additionally, there are many types of cancer.

The best we can say is that smoking significantly increases the chance of developing cancer compared to people who don’t smoke. But it’s complex and we don’t have all the answers.

There are rarely simple causes to things – life is complex

On an organisational note, saying something like ‘it has been proved that transformational leadership is better than transactional leadership’ has the same problem. There are so many variables involved that it is impossible to ‘prove’. For example, a poor transformational leader could be worse than a good transactional leader, or transformational leadership may not work in certain situations or with certain people (which appears to be the case). Notice I say, ‘appears to be the case’, not ‘has been proved’. There is always an element of doubt and, as research progresses and gets better, we start to see flaws in our research.

The problem with life, organisations, people etc. is that the number of variables or factors involved in the relationship between most things is so complex it is really hard to unravel.

Does that mean science is useless if it doesn’t prove things? No, not at all. Think about all the life-saving drugs that have been developed, for example. Does it mean the drugs work all the time and in every case? No, because there are so many variables, which is why most medicines come with a leaflet to tell you to stop taking them if you get certain reactions.

So, what researchers do when they are testing something is, firstly, they try to work out what factors may be involved (usually from previous research) and then they don’t test it. They form a hypothesis, something like we think that x is related to y in z direction or way. For example, higher levels of work engagement result in higher levels of productivity. That’s the hypothesis. However, the researcher will turn that statement around and test the null hypothesis. So, for example something like engagement (however that is measured) doesn’t result in higher productivity (however that is measured). If we then find that the null hypothesis can’t be accepted, we accept the hypothesis.

The reason for this is that it prevents things like confirmation bias, where people start looking for the answer they want / expect. This way, researchers are trying to break their hypothesis. If they can’t break it then the hypothesis is accepted. And this is important. It is only accepted – for now. It is always possible (and this happens all the time) that someone else comes along and either finds a flaw in your findings or research method or discovers a relationship or intervening factor you hadn’t. Science and research is dynamic and constantly changing.

The problem is that just looking at findings doesn’t tell you how good or what quality a study is. For example, there is a big difference between someone publishing a single case study based on one particular situation, say a factory or one office or even one person, and a study taking in 1,000s of people across the world and using robust and valid research and analysis methods.

99% of everything you are trying to do...

...has already been done by someone else, somewhere - and meticulously researched.

Get the latest research briefings, infographics and more from The Oxford Review - Free.

Success! Now check your email to confirm your subscription.

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

In evidence-based practice circles, the accuracy and reliability of the research (research quality) is an important factor when deciding to include a study in the evidence-base for a decision, especially clinical or engineering decisions where people’s lives are on the line.

One way that evidence-based practitioners judge the quality of research is to use the GRADE system or framework [i] . GRADE stands for Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations, and is used extensively in medical scenarios.

GRADE is now being used in engineering, organisational evidence-based practice to judge the research and is the basis of many systematic reviews.

When choosing studies to include in a decision GRADE has four levels of evidence, or four levels of certainty, in the quality of the evidence/study:

- Very low – The real effect is probably very different from the reported findings.

- Low – The true effect is quite likely to be different from the findings of this study.

- Moderate – The true effect is probably close to the findings of this study.

- High – A high level of confidence that, the findings represent the true effect / represents reality.

There are five overall factors which are used to help a practitioner work out what the level of evidence a particular study is using :

- Publication bias All of these potential biases downgrade the research quality of the study.

Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias

The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias usually uses a 3-point grading system for judging bias and is an important factor in working the quality of research :

- Low risk of bias

- High risk of bias

- Unclear risk of bias

In 2005 The Cochrane Institute in Oxford produced a tool that has become the standard bias risk assessment tool – The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias – and looks specifically at a range of different biases that can affect a study’s findings. The tool looks for whether the study being looked at:

- Uses quality scales. Quality scales are often inherently biased and based on opinions.

- Looks at the internal validity of the study. What this means is that the researchers extensively look for and report any potential biases the method or study might have. In other words, are the methods used in the study likely to lead to bias or less so?

- Has actively looked for sources of bias or influence in their results. Double blind trials, where neither the participants (subjects) nor the researchers know which subject is getting which treatment or is in which group are considered to be at the least risk of bias.

- That the assessor / evaluator understands the methods used and can make a good judgement about the methods used.

- Is there a risk of bias in the way the data is being presented or represented?

- Does the use or group to which you are putting the study introduce a risk of bias not associated to the study?

How precise are the data and methods used for the study?

Does the study show inconsistences openly or do they try to mask them? Are there inherent inconsistencies that haven’t been reported?

How close is the situation / population of the study being looked at to the one it is being applied to? Is this study talking directly into and about the organisation or population of the study, or is this being used in a more indirect way?

- Does the publisher have a stake in the findings? For example, is this a study by a consultancy attempting to show how good its own methods are?

All of these potential biases downgrade the quality of the research study.

When assessing a study, we are looking for good research that is applicable to the situation to which the findings are being put. It needs to be valid (the methods used actually give good data and is measuring what we think it is measuring) and reliable (you keep getting the same results). Being able to spot bias in all its forms in research studies is essential if you are using research to inform organisational decisions.

Our research briefings, research quality and the review panel

At the end of all of all of our research briefings we have an assessment/review of the study being reported. We use the following simplified panel to grade the quality of the study under consideration:

- Research Quality – 3/5 A good literature review and overview of the subject. Based on a meta-analysis, rather than primary research.

- Confidence – 4/5 Consistent with the current research thinking and developments.

- Usefulness – 4/5 Particularly useful to HR practitioners.

- Comments – The current focus on differentiated HR architecture (structures and systems) to support talent management is showing a lot of promise in improving organisational performance generally.

And we always fully cite which studies we have used, so that you can check it and do further reading

[i] Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2008;336(7651):995-8. [i]

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2008;336(7650):924-6.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64(4):383-94.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64(4):395-400.

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2011;64(4):401-6.

Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Kunz, R., Vist, G. E., Falck-Ytter, Y., & Schünemann, H. J. (2008). What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians?. Bmj , 336 (7651), 995-998.

BMJ Best practice series: What is GRADE? Accessed at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/ on 3 rd November 2019

Guyatt, G., Oxman, A. D., Akl, E. A., Kunz, R., Vist, G., Brozek, J., … & Jaeschke, R. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of clinical epidemiology , 64 (4), 383-394.

Be impressively well informed

Get the very latest research intelligence briefings, video research briefings, infographics and more sent direct to you as they are published

Be the most impressively well-informed and up-to-date person around...

Success! Now check your email to confirm that we got your email right. If you don't get an email in the next 4-5 minutes something went wrong: 1. Check your junk folder just in case 🙁 2. If it's not there either, you may have accidentally mistyped your email address (it happens). Have another go. Many thanks

Related Posts

Research Review of The Balanced Scorecard

Podcast: What are the workplace issues of neurodiversity?

Which factors motivate salespeople the most?

Fear of Failure and Self-sabotage, Self-handicapping and Self-deception

Nudge behaviour change – Is it real?

Change Myths: Separating Sense from Nonsense

How Aversive Leadership Impacts Employee Proactivity and Moral Disengagement

Podcast: What is Neurodiversity?

David Wilkinson

David Wilkinson is the Editor-in-Chief of the Oxford Review. He is also acknowledged to be one of the world's leading experts in dealing with ambiguity and uncertainty and developing emotional resilience. David teaches and conducts research at a number of universities including the University of Oxford, Medical Sciences Division, Cardiff University, Oxford Brookes University School of Business and many more. He has worked with many organisations as a consultant and executive coach including Schroders, where he coaches and runs their leadership and management programmes, Royal Mail, Aimia, Hyundai, The RAF, The Pentagon, the governments of the UK, US, Saudi, Oman and the Yemen for example. In 2010 he developed the world's first and only model and programme for developing emotional resilience across entire populations and organisations which has since become known as the Fear to Flow model which is the subject of his next book. In 2012 he drove a 1973 VW across six countries in Southern Africa whilst collecting money for charity and conducting on the ground charity work including developing emotional literature in children and orphans in Africa and a number of other activities. He is the author of The Ambiguity Advanatage: What great leaders are great at, published by Palgrave Macmillian. See more: About: About David Wikipedia: David's Wikipedia Page

- Previous post

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

- Editorial Notes

- Open access

- Published: 07 January 2020

What is useful research? The good, the bad, and the stable

- David M. Ozonoff 1 &

- Philippe Grandjean 2 , 3

Environmental Health volume 19 , Article number: 2 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

A scientific journal like Environmental Health strives to publish research that is useful within the field covered by the journal’s scope, in this case, public health. Useful research is more likely to make a difference. However, in many, if not most cases, the usefulness of an article can be difficult to ascertain until after its publication. Although replication is often thought of as a requirement for research to be considered valid, this criterion is retrospective and has resulted in a tendency toward inertia in environmental health research. An alternative viewpoint is that useful work is “stable”, i.e., not likely to be soon contradicted. We present this alternative view, which still relies on science being consensual, although pointing out that it is not the same as replicability, while not in contradiction. We believe that viewing potential usefulness of research reports through the lens of stability is a valuable perspective.

Good science as a purpose

Any scientific journal wishes to add to the general store of knowledge. For Environmental Health, an additional important goal is also to publish research that is useful for public health. While maximizing scientific validity is an irreducible minimum for any research journal, it does not guarantee that the outcome of a “good” article is useful. Most writing on this subject concerns efficiencies and criteria for generating new and useful research results while avoiding “research waste” [ 1 ]. In this regard, the role of journals is hard to define. Indeed, a usefulness objective depends upon what happens after publication, thus to some extent being out of our control. That said, because of the importance of this issue the Editors have set out to clarify our thinking about what makes published research useful.

First the obvious: properly conducted scientific research may not be useful, or worse, may potentially mislead, confuse or be erroneously interpreted. Journal editors and reviewers can mitigate such regrettable outcomes by being attentive to faulty over- or under-interpretation of properly generated data, and vice versa, ensuring that unrealistic standards don’t prevent publication of a “good” manuscript. In regard to the latter, we believe our journal should not shy away from alternative or novel interpretations that may be counter to established paradigms and have consciously adopted a precautionary orientation [ 2 ]: We believe that it is reasonable to feature risks that may seem remote at the moment because the history of environmental and occupational health is replete with instances of red flags ignored, resulting in horrific later harms that could no longer be mitigated [ 3 , 4 ].

Nonetheless, it has happened that researchers publishing results at odds with vested interests have become targets of unreasonable criticism and intimidation whose aim is to suppress or throw suspicion on unwelcome research information, as in the case of lead [ 3 , 5 ] and many other environmental chemicals [ 6 ]. An alternative counter strategy is generating new results favorable to a preferred view [ 7 , 8 ], with the objective of casting doubt on the uncomfortable research results. Indeed, one trade association involved in supporting such science once described its activities with the slogan, “Doubt is our product” [ 9 ]. Thus, for better or for worse, many people do not separate science, whether good or bad, from its implications [ 10 ].

Further, even without nefarious reasons, it is not uncommon for newly published research to be contradicted by additional results from other scientists. Not surprisingly, the public has become all too aware of findings whose apparent import is later found to be negligible, wrong, or cast into serious doubt, legitimately or otherwise [ 11 ]. This has been damaging to the discipline and its reputation [ 12 ].

Replication as a criterion

A principal reaction to this dilemma has been to demand that results be “replicated” before being put to use. As a result, both funding agencies [ 13 ] and journals [ 14 ] have announced their intention of emphasizing the reproducibility of research, thereby also facilitating replication [ 15 ]. On its face this sounds reasonable, but usual experimental or observational protocols are already based on internal replication. If some form of replication of a study is desired, attempts to duplicate an experimental set-up can easily produce non-identical measurements on repeated samples, and seemingly similar people in a population may yield somewhat different observations. Given an expected variability within and between studies, we need to define more precisely what is to be replicated and how it is to be judged.

That said, in most instances, it seems that what we are really asking for is interpretive replication (i.e., do we think two or more studies mean the same thing), not observational or measurement replication. Uninterpreted evidence is just raw data. The main product of scientific journals like Environmental Health is interpreted evidence. It is interpreted evidence that is actionable and likely to affect practice and policy.

Research stability

This brings us back to the question of what kind of evidence and its accompanying interpretation is likely to be of use? The philosopher Alex Broadbent distinguishes between how results get used and the decision about which results are likely to be used [ 16 ]. Discussions of research translation tend to focus on the former question, while the latter is rarely discussed. Broadbent introduces a new concept into the conversation, the stability of the research results.

He begins by identifying which results are not likely to be used. Broadbent observes that if a practitioner or policy-maker thinks a result might soon be overturned she is unlikely to use it. Since continual revision is a hallmark of science, this presents a dilemma. All results are open to revision as science progresses, so what users and policy makers really want are stable results, ones whose meaning is unlikely to change in ways that make a potential practice or policy quickly obsolete or wrong. What are the features of a stable result?

This is a trickier problem than it first appears. As Broadbent observes it does not seem sufficient to say that a stable a result is one that is not contradicted by subsequent work, an idea closely related to replication. Failure to contradict, like lack of replication, may have many reasons, including lack of interest, lack of funding, active suppression of research in a subject, or external events like social conflict or recession. Moreover, there are many examples of clinical practice, broadly accepted as stable in the non-contradiction sense, that have not been tested for one reason or another. Contrariwise, contradictory results may also be specious or fraudulent, e.g., due to attempts to make an unwelcome result appear unstable and hence unusable [ 6 , 9 ]. In sum, lack of contradiction doesn’t automatically make a result stable, nor does its presence annul the result.

One might plausibly think that the apparent truth of a scientific result would be sufficient to make a result stable. This is also in accordance with Naomi Oreskes’ emphasis of scientific knowledge being fundamentally consensual [ 10 ] and relies on the findings being generalizable [ 15 ]. Our journal, like most, employs conventional techniques like pre-publication peer review and editorial judgment, to maximize scientific validity of published articles; and we require Conflict of Interest declarations to maximize scientific integrity [ 6 , 17 ]. Still, a result may be true but not useful, and science that isn’t true may be very useful. Broadbent’s example of the latter is the most spectacular. Newtonian physics continues to be a paragon of usefulness despite the fact that in the age of Relativity Theory we know it to be false. Examples are also prevalent in environmental health. When John Snow identified contaminated water as a source of epidemic cholera in the mid-nineteenth Century he believed a toxin was the cause, as the germ theory of disease had not yet found purchase. This lack of understanding did not stop practitioners from advocating limiting exposure to sewage-contaminated water. Nonetheless, demands for modes of action or adverse outcome pathways are often used to block the use of new evidence on environmental hazards [ 18 ].

Criteria for stability

Broadbent’s suggestion is that a result likely to be seen as stable by practitioners and policy makers is one that (a) is not contradicted by good scientific evidence; and (b) would not likely be soon contradicted by further good research [ 16 ] (p. 63).

The first requirement, (a), simply says that any research that produces contradictory evidence be methodologically sound and free from bias, i.e., “good scientific evidence.” What constitutes “good” scientific evidence is a well discussed topic, of course, and not a novel requirement [ 1 ], but the stability frame puts existing quality criteria, in a different, perhaps more organized, structure, situating the evidence and its interpretation in relation to stability as a criterion for usefulness.

More novel is requirement (b), the belief that if further research were done it would not likely result in a contradiction. The if clause focuses our attention on examining instances where the indicated research has not yet been done. The criterion is therefore prospective, where the replication demand can only be used in retrospect.

This criterion could usefully be applied to inconclusive or underpowered studies that are often incorrectly labeled “negative” and interpreted to indicate “no risk” [ 18 ]. A U.S. National Research Council committee called attention to the erroneous inference that chemicals are regarded inert or safe, unless proven otherwise [ 19 ]. This “untested-chemical assumption” has resulted in exposure limits for only a small proportion of environmental chemicals, limits often later found to be much too high to adequately protect against adverse health effects [ 20 , 21 ]. For example, some current limits for perfluorinated compounds in drinking water do not protect against the immunotoxic effects in children and may be up to 100-fold too high [ 22 ].

Inertia as a consequence

Journals play an unfortunate part in the dearth of critical information on emerging contaminants, as published articles primarily address chemicals that have already been well studied [ 23 ]. This means that environmental health research suffers from an impoverishing inertia, which may in part be due to desired replications that may be superfluous or worse. The bottom line is that longstanding acceptance in the face of longstanding failure to test a proposition should not be used as a criterion of stability or of usefulness, although this is routinely done.

If non-contradiction, replication or truth are not reliable hallmarks of a potentially useful research result, then what is? Broadbent makes the tentative proposal that a stable interpretation is one which has a satisfactory answer to the question, “Why this interpretation rather than another?” Said another way, are there more likely, almost or equally as likely, or other possible explanations (including methodological error in the work in question)? Sometimes the answer is patently obvious. Such an evaluation is superfluous in instances where the outcomes have such forceful explanations that this exercise would be a waste of time, for example a construction worker falling from the staging. We only need one instance and (hopefully no repetitions) to make the case.

Consensus and stability