- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- Plant and animal life

- Ethnic groups and languages

- Rural settlement

- Urban settlement

- Demographic trends

- Agriculture, forestry, and fishing

- Resources and power

- Manufacturing

- Transportation

- Constitutional framework

- Local government

- Justice and security

- Political process

- Health and welfare

- Daily life and social customs

- Music, literature, and film

- Visual arts

- Cultural institutions

- Sports and recreation

- Media and publishing

- The prehistory of Wales

- Roman Wales (1st–4th centuries)

- The founding of the kingdoms

- Early Christianity

- Political development

- Early Welsh society

- Norman infiltration

- Gwynedd, Powys, and Deheubarth

- Llywelyn ap Iorwerth

- The Edwardian settlement

- Rebellion and annexation

- Union with England

- The Reformation

- Social change

- Politics and religion, 1640–1800

- The growth of industrial society

- Political radicalism

- The 20th century

- The 21st century

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- GlobalSecurity.org - Wales, United Kingdom

- Official Site of Wales, United Kingdom

- Official Tourism Site of Wales, United Kingdom

- Wales - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Wales - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Is Wales part of the United Kingdom?

Wales is a constituent unit of the United Kingdom that forms a westward extension of the island of Great Britain.

What kind of climate does Wales have?

Wales has a maritime climate with frequent precipitation; annual totals average 55 inches (1,385 mm). Winter snowfall can be significant in the uplands. The mean daily temperature is 50 °F (10 °C), ranging from 40 °F (4 °C) in January to 61 °F (16 °C) in July and August.

What languages are spoken in Wales?

Welsh and English are the primary languages spoken in Wales.

What is the name of Wales in Welsh?

The name of Wales in Welsh is Cymru.

Wales , constituent unit of the United Kingdom that forms a westward extension of the island of Great Britain. The capital and main commercial and financial centre is Cardiff .

Famed for its strikingly rugged landscape, the small nation of Wales—which comprises six distinctive regions—was one of Celtic Europe’s most prominent political and cultural centres, and it retains aspects of culture that are markedly different from those of its English neighbours.

Recent News

The medieval chronicler Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) had topography , history, and current events alike in mind when he observed that Wales is a “country very strongly defended by high mountains, deep valleys, extensive woods, rivers, and marshes; insomuch that from the time the Saxons took possession of the island the remnants of the Britons, retiring into these regions, could never be entirely subdued either by the English or by the Normans.” In time, however, Wales was in fact subdued and, by the Act of Union of 1536, formally joined to the kingdom of England. Welsh engineers, linguists, musicians, writers, and soldiers went on to make significant contributions to the development of the larger British Empire even as many of their compatriots laboured at home to preserve cultural traditions and even the Welsh language itself, which enjoyed a revival in the late 20th century. In 1997 the British government, with the support of the Welsh electorate, provided Wales with a measure of autonomy through the creation of the Welsh Assembly, which assumed decision-making authority for most local matters.

Although Wales was shaken by the decline of its industrial mainstay, coal mining , by the end of the 20th century the country had developed a diversified economy, particularly in the cities of Cardiff and Swansea , while the countryside, once reliant on small farming, drew many retirees from England. Tourism became an economic staple, with visitors—including many descendants of Welsh expatriates—drawn to Wales’s stately parks and castles as well as to cultural events highlighting the country’s celebrated musical and literary traditions. In the face of constant change, Wales continues to seek both greater independence and a distinct place in an integrated Europe.

Wales is bounded by the Dee estuary and Liverpool Bay to the north, the Irish Sea to the west, the Severn estuary and the Bristol Channel to the south, and England to the east. Anglesey (Môn), the largest island in England and Wales, lies off the northwestern coast and is linked to the mainland by road and rail bridges. The varied coastline of Wales measures about 600 miles (970 km). The country stretches some 130 miles (210 km) from north to south, and its east-west width varies, reaching 90 miles (145 km) across in the north, narrowing to about 40 miles (65 km) in the centre, and widening again to more than 100 miles (160 km) across the southern portion.

Glaciers during the Pleistocene Epoch (about 2,600,000 to 11,700 years ago) carved much of the Welsh landscape into deeply dissected mountains, plateaus , and hills, including the north-south–trending Cambrian Mountains, a region of plateaus and hills that are themselves fragmented by rivers. Protruding from that backbone are two main mountain areas—the Brecon Beacons in the south, rising to 2,906 feet (886 metres) at Pen y Fan, and Snowdonia in the northwest, reaching 3,560 feet (1,085 metres) at Snowdon , the highest mountain in Wales. Snowdonia’s magnificent scenery is accentuated by stark and rugged rock formations, many of volcanic origin, whereas the Beacons generally have softer outlines. The uplands are girdled on the seaward side by a series of steep-sided coastal plateaus ranging in elevation from about 100 to 700 feet (30 to 210 metres). Many of them have been pounded by the sea into spectacular steplike cliffs. Other plateaus give way to coastal flats that are estuarine in origin.

Wales consists of six traditional regions—the rugged central heartland, the North Wales lowlands and Isle of Anglesey county, the Cardigan coast (Ceredigion county), the southwestern lowlands, industrial South Wales, and the Welsh borderland. The heartland, which coincides partly with the counties Powys , Denbighshire , and Gwynedd , extends from the Brecon Beacons in the south to Snowdonia in the north and includes the two national parks based on those mountain areas. To the north and northwest lie the coastal lowlands, together with the Lleyn Peninsula (Penrhyn Llŷn) in Gwynedd and the island of Anglesey. To the west of the heartland, and coinciding with the county of Ceredigion , lies the coastline of Cardigan Bay, with numerous cliffs and coves and pebble- and sand-filled beaches. Southwest of the heartland are the counties of Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire . There the land rises eastward from St. David’s Head, through moorlands and uplands, to 1,760 feet (536 metres) in the Preseli Hills. South Wales stretches south of the heartland on an immense but largely exhausted coalfield . To the east of the heartland, the Welsh border region with England is largely agricultural and is characterized by rolling countryside and occasional wooded hills and mountainous moorland.

The main watershed of Wales runs approximately north-south along the central highlands. The larger river valleys all originate there and broaden westward near the sea or eastward as they merge into lowland plains along the English border. The Severn and Wye , two of Britain’s longest rivers, lie partly within central and eastern Wales and drain into the Bristol Channel via the Severn estuary. The main river in northern Wales is the Dee , which empties into Liverpool Bay. Among the lesser rivers and estuaries are the Clwyd and Conwy in the northeast, the Tywi in the south, and the Rheidol in the west, draining into Cardigan Bay (Bae Ceredigion). The country’s natural lakes are limited in area and almost entirely glacial in origin. Several reservoirs in the central uplands supply water to South Wales and to Merseyside and the Midlands in England.

The parent rock of Wales is dominated by strata ranging from Precambrian time (more than 540 million years ago) to representatives of the Jurassic Period (about 200 million to 145 million years ago). However, glaciers during the Pleistocene blanketed most of the landscape with till (boulder clay), scraped up and carried along by the underside of the great ice sheets, so that few soils can now be directly related to their parent rock. Acidic, leached podzol soils and brown earths predominate throughout Wales.

- News & Events

- Our Partners

Our Bookshelf

- Books from Wales

- Authors from Wales

- Translations

- Translation Grants Fund

Browse our Bookshelves, selected annually by the Exchange as a window to recent Welsh literary works which we recommend for translation.

Welsh (Plural): Essays on the Future of Wales

What does it mean to imagine Wales and 'The Welsh' as something both distinct and inclusive? In Welsh (Plural), some of the foremost Welsh writers consider the future of Wales and their place in it. For many people, Wales brings to mind the same old collection of images - if it's not rugby, sheep and leeks, it's the 3 Cs: castles, coal, and choirs. Heritage, mining and the church are indeed integral parts of Welsh culture. But what of the other stories that point us toward a Welsh future? In this anthology of essays, authors offer imaginative, radical perspectives on the future of Wales as they take us beyond the cliches and binaries that so often shape thinking about Wales and Welshness. Includes essays from Charlotte Williams, Joe Dunthorne, Niall Griffiths , Rabab Ghazoul, Mike Parker, Martin Johnes, Kandace Siobhan Walker, Gary Raymond, Darren Chetty, Andy Welch, Marvin Thompson, Durre Shahwar, Hanan Issa, Dan Evans, Shaheen Sutton, Morgan Owen, Iestyn Tyne, Grug Muse and Cerys Hafana.

Iestyn Tyne

Publication details

- Repeater Books (2022)

Translation rights

Watkins Media Limited [email protected]

Watch Author discuss and read from Meet the Author: Manon Steffan Ros

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/19903594

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/26594982

Watch Author discuss and read from Translating Minority Languages in the Literary Translation Centre

Watch Author discuss and read from Digwyddiad Diwrnod Rhyngwladol Mamiaith 2021

Watch Author discuss and read from Alun Davies | Ar Lwybr Dial (Pursuit of Vengeance)

Watch Author discuss and read from Cyfnewid Anrhegion

Watch Author discuss and read from Iaith y Nefoedd (The Language of Heaven) | Llwyd Owen

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/9019016

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/14838693

Watch Author discuss and read from The Party Wall | Stevie Davies

Watch Author discuss and read from The Jeweller | Caryl Lewis, translated by Gwen Davies

Watch Author discuss and read from We Could Be Anywhere By Now | Katherine Stansfield

Watch Author discuss and read from Footnotes to Water | Zoë Skoulding

Watch Author discuss and read from Gwirionedd | Elinor Wyn Reynolds

Watch Author discuss and read from Stillicide | Cynan Jones

Watch Author discuss and read from The Mission House | Carys Davies

Watch Author discuss and read from Wing | Matthew Francis

Watch Author discuss and read from Filò | Siân Melangell Dafydd

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/463779459

Watch Author discuss and read from Her Gyfieithu 2020 Translation Challenge

Watch Author discuss and read from Zafer Şenocak 'Nahaufnahmen’

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/463767754

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/463766831

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/29255892

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/11075895

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/11551571

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/11682522

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/12828372

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/14972312

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/14851476

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/26593990

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/16725923

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/7856028

Watch Author discuss and read from Lloyd Markham on Bad Ideas/Chemicals

Watch Author discuss and read from Llŷr Gwyn Lewis on Rhyw Flodau Rhyfel (Some Flowers of War)

Watch Author discuss and read from Llŷr Gwyn Lewis on 'Fabula'

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/452198481

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/448562290

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/448566977

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/448567473

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/448576310

Watch Author discuss and read from https://player.vimeo.com/video/453687535

Watch Author discuss and read from Darllen y Byd - Llenyddiaeth Ryngwladol i Blant yn y Gymraeg

“A smart and timely exploration of Welshness.”

“A gritty oral history and a vibrant set of essays examine Wales’s past and its renewed sense of purpose, sparked by a new generation.”

Judge Rogers, The Guardian

Dysgu Nofio

Merch y llyn, welsh (plural):…, just so you know:…, ar ddisberod.

In Conversation with the Editors of Welsh [Plural]

Wales Arts Review speaks to the editors of Welsh (Plural): Essays on the Future of Wales – Darren Chetty, Grug Muse, Hanan Issa and Iestyn Tyne – for an insight into this watershed collection of essays and its ambition to reveal imaginative perspectives on Welshness that are not bound by clichés and binaries. Here, we hear from each of the editors on their vision for this book and the challenges faced in making it a reality.

How did the concept of the project come about?

Grug: Hanan, Darren and I were at the Hay Festival in 2019 as part of the Hay Writers at Work programme, and over the course of the 10 or so days we were there, questions about the place of Welsh writing in the British publishing world kept coming up. Wherever you fall on the question of Britishness, and I’m one that would enjoy watching this union fall apart, I think it’s hard to escape the fact that Welsh writing has struggled to get the same attention as Irish (Northern or Republican) and Scottish writing gets. Maybe it’s a branding problem, maybe it’s numbers, whatever it is, nowhere does it feel more evident than when you are a Welsh writer hanging out in the Hay festival, which might be physically on the Welsh side of the border, but emotionally I think it’s fair to say it’s not. So, this book in many ways was born out of those conversations: why can’t books about Wales, and by Welsh writers, do well in the London publishing scene.

But… hold on. What do we mean by Welsh? Who? When, to quote Gwyn Alf. It’s those first conversations that got us started, but it’s the questions that came next that made the book interesting. Yes, let’s get the world to pay attention to Wales, but let’s make sure it’s a reflection of the Wales that we all know, the different Waleses that we all know, not the 2D caricatures you get in escapist novels or feel-good films about miners.

Iestyn: I joined the team a little later, when the idea was beginning to take shape; a few contributors had expressed an interest by that point and I remember the infectious enthusiasm that bubbled over in the first Skype call I had with the others. I hadn’t been to Hay – and haven’t been yet, but it looks like Welsh (Plural) will be the reason I finally make it! – and so hadn’t been part of those initial conversations, but I already shared the same frustrations and similar ideas to Hanan, Darren and Grug and was very happy to be invited.

Can you tell us a little bit about what you were looking for in the writers?

Hanan: We built a ‘dream list’ of writers we wanted to approach, keeping in mind how important we felt it was to balance aspects such as gender, location, heritage, proximity to the Welsh language etc. There’s so much talent out there it wasn’t hard to compile that list but narrowing it down was a challenge. We thought there might be some overlap or duplication of topics but even though there are themes running right through the book, each essayist has a fresh, distinct perspective.

Darren: We wanted people who could write memorable essays – and perhaps play with the form. So Marvin Thompson’s essay is a poem followed by his reflection on the process, Charlotte Williams combines personal writing with her account of chairing the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Communities, Contributions and Cynefin in the New Curriculum Working Group , Gary Raymond wrote his essay as a first-person role-playing game and Rabab Ghazoul’s is a series of letters to the editors. As we say in the introduction when discussing the cover, the book is our collective tailor’s quilt of stories.

There must have been some idea of notions you wanted to work against when discussing the vision for the book? Cliches about Wales, or just concepts of what a book like this could be?

Iestyn: As we’ve mentioned in the blurb – which is taken almost word for word from the original brief we set our contributors – there is a set of images that the idea of Wales brings to mind for many people – ‘if it’s not rugby, sheep and rolling hills, it’s the 3 Cs: castles, coal and choirs’. In fact, the book contains references to all those things; indeed, they are central themes in many – sheep, in my own essay; rugby in Joe Dunthorne’s essay; and there’s mention of Wales’ ‘modest’ mountains in the opening paragraph of ‘Medium, Rare’ by Mike Parker. Several of the contributors refer to the Wales’ industrial heritage and life in its wake … so I don’t think the book necessarily works against all those cliches, I suppose an element of truth is often the starting point of a cliche; but we did want fresh reimaginings, and that is what I believe we got.

In terms of what books like this could be, we did steer away from work that was too drily political – the idea driving Welsh (Plural) is that more creative writing can be harnessed to offer a vision for the future, too; that this is not a less valid way of thinking of how things could be; and that you can paint a picture of the future you dream of without necessarily having every answer for every step of the way to hand. I hope Welsh (Plural) gains an audience with people who perhaps feel that conversations on the future of Wales that happen in the political realm fail to engage them for whatever reason.

Do you think it was harder or easier to pull this all together during the pandemic?

Grug: One of the biggest challenges was that we all live a distance from each other, which meant that even pre-pandemic we were already mostly meeting through Skype and Zoom, so in a way the pandemic had very little effect on the project.

Darren: Literature Wales have been very supportive from the off, and they did offer us a weekend at Tŷ Newydd to meet as an an editorial team. But the pandemic prevented that from happening. Skype, Zoom, Google Docs, Email and WhatsApp have all played major supporting roles in the creation of the book.

How did you see the collection taking shape as the contributions began to come in?

Hanan: The hunger for a book like this was what struck me. Almost everyone involved expressed how necessary they felt it was to have a book highlighting Wales as a distinct yet inclusive nation. Also, how the sense of not being Welsh enough was such a common sentiment regardless of where people lived, their ethnicity, or gender. The collection became such a clear demonstration of just how pointless it is to stereotype Welshness.

Darren: Yes, there seemed to be lurking in many contributor’s minds a kind of Platonic ideal of Welshness that one can picture but never actually attain. But then there are also fascinating reflections on why that might be and what it might say for Wales.

Were there any disagreements about direction between editors – any example of where some tension resulted in a revelation for all concerned?

Iestyn: I wouldn’t say disagreements about direction; however, we assigned a combination of two editors to each individual essay and this was definitely a good call – it meant that we could challenge each others’ interpretations of what people had written. In my experience this was particularly valuable when working on an essay by a writer of whom I’ve been a long time admirer – my co-editor in that case was able to highlight the blindspots I might have had, which ensured a careful and considerate edit.

Darren: Yes, an editing team of four didn’t mean that we all ended up doing a quarter of the work a single editor would. Collaboration involves additional work – conversations, consultations, negotiations – but I think the book is much richer for that. I like that the (Plural) aspect of the book extends to how it was curated and edited. It’s almost three years since our first conversation at Hay in 2019 – and we’ve been in conversation throughout since then!

Tell us about the decision to go with an English publisher for a book of essays about Welshness?

Grug: Almost just to see if we could. Could a book about Welshness succeed outside of Wales? It’s going alright so far, we will keep you posted!

Darren: We talked to a lot of publishers. We knew we were going to devote a lot of time to putting the book together and we wanted a publisher that was as enthusiastic about the book as we were, and was confident they could give it the exposure that we think it deserves. Repeater have published some excellent radical non-fiction and understood what we were trying to do with the book.

What impact would you hope for this book to have?

Hanan: I’m hoping this will become a go-to book when discussing Welshness. As well as book-shops, I can see it on syllabuses, in Welsh gift shops etc. quietly spreading the story of a country rich with varied experiences.

Iestyn: I think it’s also important to emphasise that while we’ve been able to bring a collection together that is hugely diverse in perspectives and experiences, a sequence of 19 essays is still never going to present the full picture in all its complexity. I would love to see it spark more writing in the same vein; more story-sharing and more listening, too!

Darren: Yep, I think we’ve built on Dai Smith’s observation that Wales is a ‘plural experience’ and I very much hope that others will too.

Has there been any talk of future collaborations between you four now you’ve had this experience?

Grug: I’m a longtime collaborator with both Hanan and Iestyn, working with Hanan as an individual writer, and getting into all sorts of misadventures in Welsh language publishing with Iestyn, as part of the team that used to run Cylchgrawn y Stamp, and now runs Cyhoeddiadau’r Stamp. I expect we’ll keep going – Darren, Hanan and Iestyn are three people that I have enjoyed working with immensely, and have learned so much from them, but I think we all deserve a break after Welsh (Plural). After that, who knows?

Hanan: I agree a break is needed! Grug, Iestyn and Darren are phenomenal writers I admire very much so I will always have time for future collaborations with any or all of them again. A Welsh (Plural) children’s edition perhaps?

Iestyn: Before anything else, I’m looking forward to actually meeting Darren at last! This collaboration has been entirely virtual from the start, and I’m so glad that the return of live literary events this summer will finally allow the four of us to meet up face to face. We must remember to get a picture!

Darren: Yes, we’ll be taking Welsh (Plural) to festival this year – Hay, Amdani! Fachynlleth, Green Man, Bristol Transformed, Good Life. So it might just be that I’ll finally meet Iestyn when we’re on a panel together!

Welsh [Plural]: Essays on the Future of Wales is available now via Repeater.

Further reading

The Best of 2023: Our Number Ones

Whatever happened to Rick Astley? by Bryony Rheam

Best Welsh Poetry of 2023

Best Welsh Non-Fiction books of 2023

Best Welsh Fiction of 2023

- Planet and New Welsh Review Report Funding Cut

Richard John Parfitt on Class and the Gift of Ideas.

The Sea Horizon: Part I

You may also like.

- Memoir of a Magazine

- Upheld NTW Appeal Rejected by Arts Council

- Have Yourself a Merry Indie Christmas Vol III: Line Up Reveal

- Celebration of Centenary of Women’s Peace Petition

Review: The impact of devolution in Wales – Essays edited by Jane Williams and Aled Eirug

Sarah Tanburn

Rhodri Morgan’s long shadow still looms over Welsh policy making and analysis, amply demonstrated by this book of essays due out shortly from University of Wales Press. The sub-title is Social Democracy with a Welsh Stripe and it is intended to accompany Rhodri Morgan’s personal memoir.

The distinguished collection of contributors explore the notion of a distinctive Welsh approach to policy without any insistence on, even an avoidance of, nationalism and deeply rooted in the evolution of Welsh structures and governance since 1999.

Across health, education, development and international relations, equalities and rights, the essays asks if such a stripe can be distinguished in key policy areas, and what difference it has made to the lives of people in Wales.

Geraint Talfan Davies gives the relevant warning that:

‘commentary on devolution in Wales during those first two decades tends to fall into one of two categories: patient understanding of the growth of a fragile new institution … and less patient frustration that the institution’s achievements have not been sufficiently impressive and radical, and have not realised the highest hopes that were placed in it by its proponents. ’

Other reviewers might be more embedded in Welsh politics than I am, and so, besides falling into one of these traps, be more minded to comment on this detail or that of events in the last twenty years.

Instead, I shall focus on what lessons might be taken from the book as a whole, and what that might suggest for the future.

Overall this is an elegant and nuanced study, filled with detailed knowledge and very well referenced. Any serious student of Welsh politics should have it on their shelves. Nonetheless, I would like to see the sequel, a request of which more below.

From multi-level evolution to disruption for its own sake

It is particularly important to note issues of timing, while recognising that the referendum was not ‘year zero’ for distinctively Welsh policy development, as the history of promoting Cymraeg, of developing an holistic approach to policy or to exporting Welsh culture all illustrate.

The first decade of devolution took place with a Labour government in Westminster, relatively beneficent public spending regimes and ongoing increases in the budget for the Wales Assembly Government.

The narrow majority in the first referendum put pressure on those early representatives to demonstrate genuine improvement from devolution, but they could work in relative partnership with Westminster and considerable stability.

Throughout Morgan’s tenure as First Minister he dealt with just two prime ministers and two chancellors in Blair, Brown and Darling. By comparison, in four years Mark Drakeford is on his fourth PM and fifth Chancellor. Of these, the longest Downing Street resident is Sunak, despite only entering Parliament seven years ago.

The second decade brought Osborne’s austerity to Westminster and a very different attitude to devolution. Of course, we have also had the 2016 referendum and the increasing turbulence which has followed. In his article on sustainable development, Terry Marsden accurately describes this as a move from multi-level to disruptive governance.

When I wrote Wales, the United Kingdom and Europe in 2013, it was indeed a different age, even given the centralising impact of global financial collapse and the consequent hit on European regionalism.

The disruption has of course accelerated: when Marsden wrote this essay, Johnson seemed secure in No. 10 and the nightmare of Truss’s ‘fiscal event’ was not even imagined.

Despite the enormous challenges of such disruption, there is clearly an electoral appetite for it, whether in the vote to leave the EU or the Welsh support for Truss herself (including from the newly appointed Welsh Secretary).

Marsden is writing specifically about a proper alignment of food policy, greater economic equity, and addressing environmental catastrophe, but his words apply to many other areas of policy development:

‘The analysis and recommendations have demonstrated the need to find collective hope and energy in exploring the real paradoxes that this disruptive governance also creates.

These are opportunities to re-set and redesign former sectoral, fragmented and unevenly devolved policies and competences in ways that meet now the wider [sustainable development and climate change] goals our international, as well as national, public commitments demand….

That is what present and future generations will expect of today’s governments, and that is what is embedded in Wales’s Well Being of Future Generations Act. .. This is what the onset of disruptive governance is in part telling us, and why its critical analysis both in the UK and beyond is of vital importance in … an enlivened debate about participative and devolved forms of effective democratic governance.’

The book as a whole demonstrates that global discontinuities, from climate crisis to ongoing technological revolution, play out in institutions and governance, and that the ways policy makers and legislators respond will matter for people’s everyday lives and long term futures.

Marsden and, to a lesser extent, Geraint Talfan Davies point both to the ambition for disruption explicit in narratives from Farage to Kwarteng and to the opportunities it might represent for Wales.

While the current Welsh Government has been applauded for calmness during Covid, and (at least in that context) prioritising communication which treats the public like adults, the world around us is in upheaval: are the authorities in Cardiff Bay willing, able and ready to address that reality?

In a range of proposals which sometimes smack of rearranging the deck chairs of government rather than fundamentally addressing the purpose of the voyage, the importance of reinstating a Minister for International Affairs stands out.

If Wales is to assert its position as a mature, functioning country capable of considerable impact despite the difficulties in London, this is a significant and relatively straightforward step.

Wales does have levers, from the world-leading Wellbeing Act, to the disproportionate reach of our sport and culture, to our role in agri-business but we are not yet using them sufficiently. A number of common themes across these policy essays suggest why.

A pass mark, but could do better

Every author in this volume identifies a Welsh stripe in the area of policy they examine, the much touted clear red water between Westminster policy and Cardiff.

The standout is of course the Wellbeing Act, but we can also highlight, for example, basing children’s engagement and services on rights, a distinctive approach to qualifications and the ongoing resistance to marketisation in health or schools.

In each area, there is plenty of evidence of innovation and value-driven development in domestic policy.

It is also interesting to note the comparisons used both by these analysts and by politicians. Despite the media insistence on comparisons with our wealthy neighbour, there are better places to look, small countries like Singapore, Finland and Czechia. Yet the researchers themselves sometimes do not look far enough.

There are over 8 million Catalan speakers spread across Spain, France, Italy and Andorra, for example. Te Reo Māori, another poster child for linguistic resurgence, has just 183,000 speakers, almost all in one administration. Wide-reaching internationalism in policy and outlook can only bolster Welsh innovation.

There are identified successes, not least the Welsh approach to the UK’s withdrawal from the Europe-wide Erasmus scheme encouraging student exchange and building collaborations. Geraint Talfan Davies says:

‘Taken together, the Erasmus replacement scheme and the Global Wales initiative present a case par excellence of a devolved administration pushing its way further into the international arena from the base of its devolved powers . ’

We can also recognise the importance of the Welsh approach to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Jane Sullivan summarises the first decade’s adoption of the Convention by saying:

‘[P]romotion of child rights-aligned policies played to strengths within the Assembly at a time when Welsh devolution was often seen as the weaker sibling of devolution elsewhere in the UK.

It provided an opportunity to demonstrate that Welsh devolution enabled distinct, principled policy developed through collaboration and consensus, not only between political parties but also with voluntary and statutory sectors and with children and young people themselves.

And it offered positive exposure on the world stage: an opportunity to present Welsh innovation in policy and law reform in favourable contrast to other countries in the UK, especially England, and the world.’

Her words show the mixture of motivations that influence more than one policy arena: the importance of policy driven by values of participation and justice, the drive to promote the benefits of self-determination, the ambition for cross-sector and multiparty consensus and the desire to be seen on the world stage.

Despite these laudable ambitions, a common thread in these studies is the recognition that innovative thinking has not been matched by life-changing delivery, particularly for many of our most disadvantaged children and young people.

Inevitably, such failures are normally attributed to external lacks – of power, resources, or even media shortcomings.

These of course are real. In addition, though, these analyses suggest three key internal barriers: a failure to join plans up and take a bold, holistic approach to sustained change; insufficient rigour in governance structures and, perhaps most of all, the group think engendered by a closed circle of so-called partnership and inward-looking policy making.

Making the big leaps

‘Boldness’ has gained something of a bad reputation in recent months, yet it must be admitted that big changes need both the vision of what our society can be, and the rigorous decision making needed to carry it through. And in a disrupting world context, clear vision needs to be accompanied by evidence-based, sustained interventions undertaken within a robust governance framework.

Children living in poverty are of course particularly vulnerable. Jane Williams reminds us that:

Wales has continued to have the highest percentage rates in the UK of relative income poverty for all age groups. Of all age groups, children are most likely to be in relative income poverty and children in lone parent and larger families, some BAME families, workless households and in households with a disabled adult or child are disproportionately affected.

Pre-COVID-19 data covering the periods 2015–18 show 29 per cent of children in Wales living in relative income poverty, and by reference to multiple indicators, children in poor families were on average living further below the poverty line and experiencing poorer outcomes in 2018 than in 2013.

The impact of COVID-19 has yet to be fully appreciated, but evidence suggests that it has worsened and will continue to worsen the situation, specifically exacerbating pre-existing inequalities. … [I]t remains the case that pupils in receipt of free school meals scored lower and school exclusions, which increased in a 4-year period from 2015, disproportionately affect children from poorer backgrounds, additional learning needs and some protected characteristics and the rate of permanent exclusions doubled between 2014/15 and 2017/18 and has continued to increase.

A sobering statistic is that at the end of the ‘well-being’ decade in Welsh policy, pupils in Wales were less satisfied with their lives than the OECD average, more likely to feel miserable and worried, and less likely to feel joyful, cheerful or proud.

Such figures make sobering reading indeed.

Thus In considering educational achievement, there is a clear need to reduce (rather than re-arrange) the number of organisations involved in setting policy but not in actually educating children, while also significantly enhancing the capacity of educators and school leaders.

There have been numerous efforts in this direction, yet as David Egan makes clear, there is still a great deal of talk and not enough real outcomes in classrooms.

By comparison, Williams points to recent actions addressing poverty taken by Welsh government during the COVID-19 pandemic, including increasing benefits take-up, progression of support such as free school meals, period products and access to cultural and leisure activities, alongside pupil development grant and better public transport access for young people.

Various forms of discretionary assistance and financial advice services are being enhanced. It is interesting that housing issues are omitted from this list and indeed from the whole book. It is a crucial area for Wales and one where almost all relevant policy is devolved, unlike control over most benefits.

The latest plan does include milestones and data collection, essential if policy is to learn from what works rather than starting from scratch in each political cycle.

Such information will enable policy-makers to see if such direct interventions, alongside praiseworthy, rights-based actions, really make a difference to those who need it most, improving educational outcomes and life chances by a clear focus on the front line rather than organisational musical chairs.

Scrutiny and capacity

Although not directly examined in this collection, there is widespread recognition of the need for a larger Senedd.

Despite cross-party agreement to the principle, there is still a lack of transparency about the process and a confused approach to creating the electoral lists, as Professor Laura McAllister set out in a recent article for the Constitution Unit of UCL.

At its heart, there is a lack of scrutiny of the work of the executive, and insufficient separation of powers between that executive and the legislature.

Wales is of course dominated almost exclusively by Labour, despite various partnerships with Plaid Cymru and the Liberal Democrats.

However one individual might vote, there are obvious risks to such long-standing control, which should be matched by an emphasis on probity, openness and accountability. Instead, as these analysts show, the opposite is true.

To give one example, in the detailed implementation of the Government of Wales Act, responsibility for both the Childrens’ Commissioner and Funky Dragon (predecessor to Young Wales and ultimately the Welsh Youth Parliament) went not to the legislature (now the Senedd) but to the executive. Williams says:

‘This was odd, because both functions, one statutory and one discretionary, were purposed towards holding the executive to account, which would have been better aligned with the purpose of the parliamentary function in the evolving Welsh constitution.’

In general, this chimes with a weak process of scrutinising emerging legislation, with Senedd Committees hugely overstretched by the current raft of responsibilities, limited evidential capacity on existing impact and, perhaps most worrying, a failure of political leadership to even understand the importance of their transparency.

There are also ambiguities and inconsistencies, betraying an incomplete over-arching vision of what government is for . Williams again, speaking of the Social Services and Well-being (Wales) Act 2014 noted the tendency

‘towards absorption of rights, with their internationally recognised, normative value, into the more malleable and less enforceable concept of well-being. … [T]he focus on well-being in the legislation as the cornerstone to good administration has led to the marginalisation of other foundations, e.g., human rights, equality, and specifically, principles of administrative justice that had been developed for Wales.’

There is a conflict between the much-admired sustainable development principles of WFG Act and how wellbeing may be seen to undermine the approach to embedded rights and more formal approaches to social justice.

We can spot a missed opportunity for a cross-governmental holistic approach in the ‘international strategy’ of late 2019. Geraint Talfan Davies spells out that

‘On the business and research front it wants to focus on three areas in particular: cyber security, compound semi-conductors and the creative industries. Some business people would have liked that list to be longer, but those who in the past have criticised the government for failing to prioritise can hardly complain.’

Despite his strictures on list-making, the strategy makes little or no reference to food production and agri-business, discussed in illuminating detail by Marsden. Tourism or energy are also fundamental to Wales’ development of a higher-value and resilient economy, yet they too are omitted.

Such mis-alignments matter in a government so consciously and determinedly driven by its values. If the Welsh stripe is to mean anything, it is in the values underpinning policy and governance and yet we can see here the ambiguities which in turn undermine boldness in delivery.

Longevity, partnerships and exclusion

Our third barrier to sustained change is evident almost in the cast list of the book itself. Many names echo from the 1980’s onwards.

The most prominent today is of course Mark Drakeford himself, the man largely responsible for the original notion of ‘clear red water.’ In addition to the evidence in this text, he said as much in his recent interview with Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart.

Adam Price is quoted by Eurig calling the creation of Welsh Labour a ‘master stroke’ which ‘stole Plaid’s intellectual territory.’ Clearly, however, the two men have found a way to work together in close partnership today.

This is further evidence, if it was needed, of the ambition of the political leadership of Wales to find collaboration and partnership to develop policy.

Elin Royles and Paul Chaney remind us that such notions have always been central to the campaign for and delivery of devolution. Their excellent essay examines the notions of ‘civil society’, ‘equalities’ and ‘inclusion’ as they have played out in practice, and draws some important conclusions.

They suggest, with good evidence, that in some arenas the devolved government has enabled more participative structures, exemplified by the considerably greater visibility and volume afforded to Black, Asian and ethnic minority communities today compared to the earlier, lamentable record and the failure to elect any ethnic minority candidate to the Assembly till 2007.

Highlighted here is also the growth in the number of women elected to the Senedd (a cause for congratulation in other essays too), although less attention is paid to the many other structural, sex-based inequalities in Wales, such as the very poor rate of convictions for sexual assault or rape.

Even when these are not devolved areas, the Senedd and Welsh Government must recognise the ongoing specific challenges facing women and people of colour, despite progress in representation.

I have noted above that a fully holistic approach has not been achieved, which undermines genuine understanding of plurality and inclusion.

Nonetheless, this commitment has led to a greater involvement of marginalised groups in policy making, not least through the use of the language and some of the techniques of ‘mainstreaming’ equalities, with a greater ‘system openness’ evident on many topics.

In this respect, there is indeed clear water both between Cardiff and Westminster and in the developments from the pre-devolution closed shop of the Welsh Office, with the language of equality now embedded in policy and legislation.

In addition, Royles and Chaney identify the early promotion of networks to facilitate engagement of under-represented groups, and the statutory equality duty contained in Welsh governance legislation. The latter remains unique amongst the devolved administrations and is robust both in its phasing and in much associated guidance.

Thus, from the beginning an apparent commitment to a stronger civil society, to more inclusion and to redressing historic inequality in representation, was baked in to the way the Assembly and now the Senedd expects to function.

The authors, however, also point to early concerns that some of the mechanisms put in place might have negative democratic consequences. Considerable funding has been invested in capacity development and policy networks intended to

‘facilitate activism and voluntary activity, and … to channel grass- roots views into the policy process as part of influencing policy-making.’

These concerns have materialised in some systemic failings. A study as early as 2007 found:

‘Increasing power inequalities between professionalised organisations with well-developed lobbying capabilities, both formally and informally, and those with limited resources. In addition to some organisations having the advantage of being better equipped to be represented in the political process than others, there was evidence that devolved institutions exacerbated existing inequalities. More exclusive relations were forged with some organisations , particularly through receipt of Welsh Government funding and support for policy networks.

..[T]he devolved government’s engagement methods lacked adequate recognition of the risks of creating more exclusive relations that could result in issues regarding the representativeness of organisations, increasing inequalities within civil society with repercussions for the relative autonomy of organisations, including challenging their propensity to scrutinise government as expected in a vibrant democracy.‘ (Emphases mine)

The clear risk is that in paying some organisations to develop robust networks to represent and engage specific marginalised communities, they become lobby agencies for particular agendas.

Because the Senedd is so stretched, those lobbying agencies become the source (and in some cases the author) of policy documents ostensibly the property of Welsh Government itself.

Those partnerships, originally created to promote diversity and inclusion become the originators and endorsers of specific interests from which contrary voices may be actively excluded.

This challenge is borne out by research. The authors cite Rebecca Rumbul’s study of scrutiny in Wales, arguing that activist citizens outside the charmed circle of funded partners feel:

‘disengaged, disillusioned and disregarded by the political and public sector institutions in Wales, … Of particular concern were assertions of ‘institutional lethargy’ on the part of WG in its approach to broadening the participation of civil society in policy development and delivery beyond the ‘usual suspects’.’

As one outside that circle, I have seen these mechanisms operate across diverse topics, from forestry ownership to sex-based rights to the choice of a dignified death.

Informed voices who do not adhere to the agenda of established and funded partners find it impossible to gain even a basic audience with Welsh Government representatives. In effect, criticism of the pre-determined lobby agenda is silenced.

This is a sore failing in a maturing social democracy. Closed minds and suppression of dissent can only inhibit sustainable delivery and count against the presumed success of a distinctive Welsh approach to inclusion and social justice.

As Williams concludes, these are:

‘key ongoing challenges in realising the vision of social democracy with a Welsh stripe; particularly addressing … the need for sustained efforts to enable a critical, diverse and independent civil society as an essential ingredient of a revitalised and healthy Welsh democracy.‘

So what about that sequel?

This structured and important research shows clearly Wales has all the intellectual capacity to create a genuinely rooted, imaginative and committed government, even when that brainpower is stymied by shortage of resources for evidence and too small a Senedd.

Yet delivery is frustrated and remains timid. These essays suggest a cross-Senedd lack of boldness and holistic vision. They reveal a charmed inner circle engaged in group-think and a lack of serious challenge or scrutiny. These are all solid but demountable barriers to ambition.

A worthy sequel to this book would be an review of routes to overcoming those barriers. It would be well evidenced but accessible to the lay reader. Such a book would offer government tools to open up to robust debate, trusting all its citizens to have a voice.

It would encourage everyone involved in policy to understand each other’s constraints and drivers – from the interaction of family farms with the survival of the Welsh language, to the importance of railway management to women’s incomes.

And it would offer concerned citizens and activists the promise that Welsh Government, whatever its party dominance, has a meaningful commitment to improving the participation, environment and lives of everyone in Wales.

I look forward to the day I can shelve such a volume alongside this collection.

The Impact of Devolution in Wales: Social Democracy with a Welsh Stripe ? is published by University of Wales Press and available here or from good bookshops

Share this:

Support our nation today.

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by the people of Wales.

Our Supporters

All information provided to Nation.Cymru will be handled sensitively and within the boundaries of the Data Protection Act 2018.

Home » The Welsh Agenda » Culture » Review: The Welsh Way: Essays on Neoliberalism and Devolution

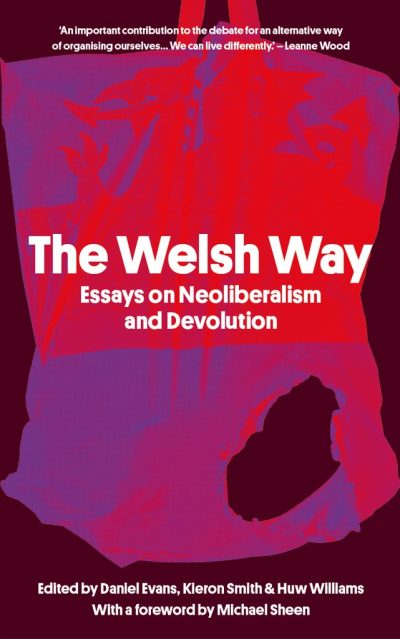

Review: The Welsh Way: Essays on Neoliberalism and Devolution

Dylan Moore shares his thoughts on The Welsh Way, a new anthology of essays decrying the hold of neoliberal values in the Welsh public sphere.

The Welsh Way begins with an introduction attributed to the 400-page volume’s three editors, Daniel Evans, Kieron Smith and Huw Williams.

It gives a broad overview of the consensus that governs Wales’ public sphere centred on a pre-pandemic speech by Mark Drakeford which ‘had it all: radicalism, a sense of a Wales that is distinct (and always defined against England as a yardstick) in its pursuit of equality, motivated by hagiographic notions of Wales’ radical socialist past’.

The authors contend that this ‘narrative of Welsh social democratic distinctiveness’ – which, let’s be honest, we all recognise – has become ‘an article of faith… widely accepted by the Welsh political class (consisting not just of politicians, but academics, journalists and commentators)’. The book’s central thesis is that the picture painted by Drakeford and by extension by all of us is ‘not remotely true’; it substantiates this repudiation in twenty-three essays that take Welsh Labour to task across a full gamut of social and policy fields.

‘Wales is… a deeply neoliberal country’ they say, and the evidence is overwhelming – and damning. Devolution is a ‘passive revolution’ that has resulted in ‘the continued collapse of Welsh society under the pressures of late capitalism’; ‘the Welsh Way is to play the subordinate partner in… relations with international capital’ and to ‘tinker around the edges’. Policies hailed as Welsh Government success stories – ‘plastic bag charges, 20mph speed limits, banning pavement parking [are] small gestures within a system that continues to immiserate people.’

‘The Welsh Way is a full frontal attack: jabs, hooks and near-fatal body blows delivered from the Left.

Let me begin, then, by admitting the presence of a log in my own eye. Editing a current affairs magazine for a leading Welsh think tank, there is of course a danger that I, together with this very magazine and the IWA more widely, are a part of the very ecosystem that perpetuates cosy consensus and thereby facilitates neoliberal orthodoxy and props up political timidity.

Having said this, however, the bibliographies following each essay reveal that around a third of the book’s contributors draw upon articles published in the welsh agenda . So at the very least we are hosting the debate – although this is little succour when that debate characterises our nation, with stacks of evidence, as a place of ‘nuclear colonialism’ (Robat Idris); ‘marketisation of universities’ (Joe Healey); ‘a lack of affordable housing’ (Steffan Evans); ‘the highest rate of incarceration in western Europe’ (Polly Manning); and ‘discriminative policing’ against both ethnic minorities and the homeless (Mike Harrison).

Innovative. Informed. Independent. Your support can help us make Wales better.

Former IWA Chair Geraint Talfan Davies has often called Wales ‘the land of the pulled punch’, and if this has for many years been true, with a soft and consensual centre-left fending off occasional aimless roundhouses from the Right, The Welsh Way is a full frontal attack: jabs, hooks and near-fatal body blows delivered from the Left.

‘Unsurprisingly, neoliberalism is held to make little sense of ‘something as basically, unquantifiably, elusively human’ as culture.

A central section of the volume is organised by ‘Policy Fields’ and I turn first to the areas where I have personally experienced the so-called ‘Welsh Way’ on the ground.

Dan Evans’ piece on education, ‘Standardising Wales’ rings immediately true:

‘In a world where everything is quantifiable, teaching and education now focus on producing data . Schools test children to track their progress, and schools and teachers themselves must be tested to ensure they are delivering high quality services. This culture forces schools to compete with one another… discourages solidarity and encourages overwhelmed teachers to begin “teaching to the test”.’

Evans sees ‘some progressive and ostensibly laudable ideas’ in the new curriculum but a fundamental contradiction in its wedding to ‘the logic of neoliberalism education’, governed by Wales’ overriding obsession with PISA rankings.

On Culture, Kieron Smith inevitably begins with a long quotation from the Welsh godfather of its complex definition, Raymond Williams, before encapsulating it in a pithy and rather beautiful phrase of his own: ‘the very stuff of the individual and collective soul’. It is a welcome intrusion on the relentlessly Marxist framework for the book’s overall analysis, which predictably relegates spiritual aspects of the human condition beneath material concerns.

Unsurprisingly, neoliberalism is held to make little sense of ‘something as basically, unquantifiably, elusively human’ as culture. A similar claim could be levelled about Marxism and the soul, and to this we will return in conclusion.

Smith goes on to use Raymond Williams’ distinction between cultural policy ‘proper’ and the concept of ‘display’ to interrogate the way ‘arts organisations… are expected to pick up the slack of a state that has failed to look after its most vulnerable’. As with education, the bureaucratisation of arts funding is immediately recognisable to one who has experienced the system.

‘Much more compassionate rhetoric emanates from Cardiff Bay than from Westminster, but it makes little difference to people’s lives.

More seriously still, Rhian E. Jones’ critique of ‘Institutional vs. Grassroots Representation’ in the arts and culture is equally unerring: ‘under neoliberalism… culture [is] increasingly pitched in terms of instrumental value rather than intrinsic worth’. She lists the National Eisteddfod, Brecon Jazz and Hay Festival as being used vacuously to ‘promote’ Wales, rather than ‘exploring or critiquing it more deeply’.

Jones also rightly points out ‘closures, cuts and downgrading’ of ‘libraries, cultural facilities [and] independent music venues’ as symptoms of ‘austerity’ associated with UK Conservative Governments, but – and here is the point The Welsh Way hammers home repeatedly – unmitigated by a timid and complacent Welsh Labour Government in Wales that has more tools within the current devolution settlement to build a truly different kind of society than they would have the Welsh people believe.

One area where Welsh Government is beholden to UK-wide policy is immigration and asylum. Much more compassionate rhetoric emanates from Cardiff Bay than from Westminster, but it makes little difference to people’s lives.

As Faith Clark puts it: ‘the reality of seeking sanctuary in Wales is little different to seeking it elsewhere in the UK.’ For all that phrases like ‘A Tolerant Nation’ and ‘Nation of Sanctuary’ have become currency in Wales, in pointed contrast with the ‘hostile environment’ dreamt up in Whitehall, this language can be contested with the question marks that accompanied both the title of the University of Wales Press volume that ‘Revisit[ed] Ethnic Diversity in a Devolved Wales’ and that of Clark’s essay here. Our conclusion must be that, just like ‘clear red water’, such phrases serve as midwives to a pernicious status quo in which Welsh realities are masked by the comfort of endlessly repeating empty ideals.

Robust debate and agenda-setting research. Support Wales’ leading independent think tank.

I have no doubt about the good intentions of many of our Senedd politicians, some of whom I know personally to be warm, caring and hard working individuals. But there can be no doubt that The Welsh Way is a wake up call. For Senedd members, and – let’s break the fourth wall here – for all of us. (When ‘we’ write ‘us’ in articles like this one, we should admit that ‘we’ are talking to ‘ourselves’ – other members of the ‘political class’ – academics, journalists and third sector good eggs, doing our little bit to mitigate the worst effects of a system we are failing to overturn).

And let’s also say this: even The Welsh Way , with its laudable commitment to social justice, its unpulled punches and its gender balanced range of contributors, hardly represents the collective lived experience of the people of Wales. Its editors make a point of claiming that ‘unlike most other books on Welsh policy [it is] written in the main by those on the margins of academia and the mainstream commentariat; PhD students, early career academics, ex-academics and activists.’

I have no doubt that many of the contributors have indeed experienced precarity, but it must also be recognised that this loose collective of marginalised academics represent a very narrow milieu of Welsh life.

‘Any campaign for the improvement of workers’ rights to live and work in more humane conditions must demand something truly new.’

What we need much more of – and I am thinking internally here too, reflecting on my own practice as a teacher, writer, editor and some-time activist, as well as about the IWA – is the type of platforming presented in the final piece of this volume.

‘Interview with Butetown Matters’ gives voice to Shutha, Nirushan and Elbashir, three young people from south Cardiff who talk about their own experiences: that ‘it’s not exactly the kind of place where you are granted much opportunity’ (Bash); ‘we regularly feel let down by the authorities and those in power’ (Nirushan) and ‘you’ll get people coming into schools, the police telling you not to use drugs, don’t do this, don’t do that… but nobody talking to us about the right things to do’ (Shutha).

These are vital voices if we are ever to emerge from the national malaise the book identifies.

One step removed from this approach, Frances Williams’ piece on ‘How the High Ideals of The Well-being of Future Generations Act Have Fallen Short’ draws on her PhD research as a ‘participant observer within community groups at “the receiving end” of policy’. This depressing phrase comes from a volunteer’s characterisation of ‘the dynamic at play’. Awful because it speaks of people having policy – schemes, programmes, action plans – done to them rather than with or even for them; depressing because true.

I turn finally to Gareth Leaman’s piece: ‘Washed Up on Severnside: Life, Work and Capital on the Border of South-East Wales’. After the ‘Policy Fields’ I have worked in, here is a ‘View of a Neoliberal Wales’ from the place I call home. How much will I recognise amid the ‘post-industrial ruination’?

The writer excoriates the Western Gateway project that has seen the UK and Welsh Governments, and local councils, ‘complicit in… granting the residents of Gwent the freedom to devote all their waking hours to precarious, underpaid and unfulfilling jobs, and the freedom to coat their lungs in carbon monoxide in pursuit of this debasement’.

Leaman identifies gentrification and deregulation as neoliberal tools to disrupt and dissolve social cohesion. He goes on to analyse the way class tensions resulting from an influx of middle class Bristolians to working class Newport can be passed off as anti-English xenophobia.

‘Unconditional love, community and hope transcend the material world that bound a Marxist analytical framework.

Leaman posits Mark Fisher’s concept of ‘red belonging’ – an ‘unconditional care without community (it doesn’t matter where you come from or who you are, we will care for you anyway)’ as a way out – and fittingly for a volume that owes so much of its theoretical underpinning to the work of Raymond Williams, ends with a search for resources of hope: ‘Any campaign for the improvement of workers’ rights to live and work in more humane conditions must demand something truly new’. He quotes Matt Colquhoun: ‘a form of existence which cannot be expressed in capitalist vocabulary’. It is the glimmer of a dream: to ‘demand more out of what it means to live, and never stop fighting for it’. A new Welsh Way.

If only we could find the beginning of the path.

For that, the humility of removing logs from our eyes will be painful but essential. We would do well to revisit the teachings of the one who first used the metaphor – in Matthew 7:5 and Luke 6:42. This is not to suggest rehashing hagiographic notions of Wales’ Christian nonconformist past to match or replace the radical socialist ones, but gently to posit the notion that there are forms of existence outside of capitalist vocabulary and neoliberal hegemony.

The Welsh Way: Essays on Neoliberalism and Devolution

Eds. Daniel Evans, Kieron Smith, Huw Williams Parthian, 2021

£10.00, available to preorder .

All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA’s disclaimer .

Photo by Catrin Ellis on Unsplash

Also within Culture

In search of Welsh cinema

Review: Nye, Wales Millennium Centre

Wales Essays

The hierarchical structure and appeals process in the court and tribunal system of england and wales, discussion analysis of the relevant law relating to the sfo’s jurisdiction in england and wales, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Britain’s Next Prime Minister Has Shown Us Who He Is, and It’s Not Good

By Oliver Eagleton

Mr. Eagleton is a journalist and the author of “The Starmer Project.” He wrote from London.

The outcome seems predestined. The British Conservative Party, moribund after 14 years in office and struggling to defend its record of routine corruption and economic mismanagement , is heading into Thursday’s general election with the backing of just 20 percent of the electorate. The opposition Labour Party, having run a colorless campaign whose main aim was to channel frustration with the government, is projected to win a huge parliamentary majority. That means that Labour’s leader, Keir Starmer , will be the country’s next prime minister.

How is he likely to govern? A former lawyer with a bland rhetorical style and a tendency to modify his policies, Mr. Starmer is accused by critics on the left and right alike of lacking conviction. He is labeled an enigma, a man who stands for nothing, with no plans and no principles. His election manifesto, which The Telegraph pronounced “the dullest on record,” appears to confirm the sense that he is a void and that the character of his administration defies prediction.

But a closer look at Mr. Starmer’s back story belies this narrative. His politics are, in fact, relatively coherent and consistent. Their cardinal feature is loyalty to the British state. In practice, this often means coming down hard on those who threaten it. Throughout his legal and political career, Mr. Starmer has displayed a deeply authoritarian impulse, acting on behalf of the powerful. He is now set to carry that instinct into government. The implications for Britain — a country in need of renewal, not retrenchment — are dire.

Mr. Starmer has seldom dwelt on the specifics of his legal career, and his personal motives are, of course, unknowable. But it seems clear, based on his track record, that Mr. Starmer’s outlook began to take shape around the turn of the millennium. By that time, he had gained a reputation as a progressive barrister who worked pro bono for trade unionists and environmentalists. But in 1999 he surprised many of his colleagues by agreeing to defend a British soldier who had shot and killed a Catholic teenager in Belfast. Four years later, he was hired as a human rights adviser to the Northern Ireland Policing Board — a role in which he reportedly helped police officers justify the use of guns, water cannons and plastic bullets.

Feted by the judicial establishment, Mr. Starmer was hired to run the Crown Prosecution Service in 2008, putting him in charge of criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. Professional success brought him closer to the state, which he repeatedly sought to shield from scrutiny. He did not bring charges against the police officers who killed Jean Charles de Menezes , a Brazilian migrant who was mistaken for a terrorist suspect and shot seven times in the head. Nor did Mr. Starmer prosecute MI5 and MI6 agents who faced credible accusations of complicity in torture. Nor were so-called spy cops — undercover officers who infiltrated left-wing activist groups and manipulated some of their members into long-term sexual relationships — held accountable.

He took a different tack with those he saw as threatening law and order. After the 2010 student demonstrations over a rise in tuition fees, he drew up legal guidelines that made it easier to prosecute peaceful protesters. The following year, when riots erupted in response to the police killing of Mark Duggan , Mr. Starmer organized all-night court sittings and worked to increase the severity of sentencing for people accused of participating. During his tenure, state prosecutors fought to extradite Gary McKinnon, an I.T. expert with autism who had embarrassed the U.S. military by gaining access to its databases, and worked to drag out the case against the WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Wales is bounded by the Dee estuary and Liverpool Bay to the north, the Irish Sea to the west, the Severn estuary and the Bristol Channel to the south, and England to the east. Anglesey (Môn), the largest island in England and Wales, lies off the northwestern coast and is linked to the mainland by road and rail bridges. The varied coastline of Wales measures about 600 miles (970 km).

In Welsh (Plural), some of the foremost Welsh writers consider the future of Wales and their place in it. For many people, Wales brings to mind the same old collection of images - if it's not rugby, sheep and leeks, it's the 3 Cs: castles, coal, and choirs. Heritage, mining and the church are indeed integral parts of Welsh culture.

Welsh (Plural): Essays on the Future of Wales is a 2022 Welsh non-fiction book. Edited by Darren Chetty, Hanan Issa, Grug Muse, and Iestyn Tyne, the book gathers an anthology of essays about Welsh identity and its future. Summary. The ...

Emma Schofield takes a closer look at Welsh [Plural], a new collection of essays which promises to break down the clichés and binaries which have traditionally shaped our thinking about Wales and Welsh identity.. I can't remember the last time I've heard as much about a non-fiction book before I've even received a copy. The hype surrounding Welsh [Plural] has been building for a while ...

In her essay, Lights in the Dark: Notes towards a personal history of Wales in the 21st Century, Kandace writes about being "tolerated nowhere, questioned everywhere".

In Welsh (Plural), some of the foremost Welsh writers consider the future of Wales and their place in it. For many people, Wales brings to mind the same old collection of images - if it's not rugby, sheep and leeks, it's the 3 Cs: castles, coal, and choirs. Heritage, mining and the church are indeed integral parts of Welsh culture.

Wales is a UK nation with a population of approximately 3,000,000 people. It is characterised by, among other things, ... Williams H (2021) Introduction: The Welsh way. In: Evans D, Smith K, Williams H (eds) The Welsh Way: Essays on Neoliberalism and Devolution. Cardigan: Parthian, pp. 1-23. Google Scholar.

Welsh (Plural) Essays on the Future of Wales edited by: Darren Chetty, Grug Muse, Hanan Issa, Iestyn Tyne. Jon Gower. There's an awful lot to commend about this eminently readable and energetic collection, from the selection of writers to the various ways in which they have each decided to marshal and present their material and stances.

Classical. Wales Arts Review speaks to the editors of Welsh (Plural): Essays on the Future of Wales - Darren Chetty, Grug Muse, Hanan Issa and Iestyn Tyne - for an insight into this watershed collection of essays and its ambition to reveal imaginative perspectives on Welshness that are not bound by clichés and binaries. Here, we hear from each of.

Sarah Tanburn Rhodri Morgan's long shadow still looms over Welsh policy making and analysis, amply demonstrated by this book of essays due out shortly from University of Wales Press. The sub-title is Social Democracy with a Welsh Stripe and it is intended to accompany Rhodri Morgan's personal memoir. The distinguished collection of contributors explore the […]

The essay collection makes it clear that Wales is, and always has been, a multicultural nation.To fully demonstrate this, the collection rounds off with a collection of pieces that consider the multidimensional nature of Welsh identity, focusing on stories that tell the complexities of the many Welsh identities that make up the nation.

The Welsh Way: Essays on Neoliberalism and Devolution. Eds. Daniel Evans, Kieron Smith, Huw Williams Parthian, 2021. £10.00, available to preorder. All articles published on the welsh agenda are subject to IWA's disclaimer. Dylan Moore is Editor of the welsh agenda. He writes this in a personal capacity. Photo by Catrin Ellis on Unsplash ...

A collection of essays exploring the impact on Welsh culture of one of the most exciting periods in history, the decades surrounding the French Revolution of 17... Front Matter ... The voices of war:: poetry from Wales 1794-1804 Download; XML; The Revd William Howels (1778-1832) of Cowbridge and London:: the making of an anti-radical ...

Wales (Welsh: Cymru ⓘ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom.It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic Sea to the south-west. As of 2021, it had a population of 3,107,494. It has a total area of 21,218 square kilometres (8,192 sq mi) and over 2,700 kilometres (1,680 mi) of coastline.

'There was a widespread public expectation that devolution would bring greater policy innovation and divergence between Scotland, Wales and the UK state.' This essay will assess the situation of divergence and convergence in Wales with a specific focus on the period after the devolution settlement.

Fourteen essays dealing with various aspects of the social and economic experience of Wales since the mid to late nineteenth century. Sign in. Hidden fields. ... Was Wales Industrialised?: Essays in Modern Welsh History: Author: John L. Williams: Edition: illustrated: Publisher: Gomer Press, 1995: ISBN: 1859021395, 9781859021392: Length: 333 ...

Wales, one of the four constituent nations of the United Kingdom, is currently undergoing major education system-level reforms and initiatives, from curriculum and qualifications, to initial teacher education and significant investments in practitioner in-service training and professional learning (Harris, Jones, & Crick, 2020; Welsh Government, 2020a).

Welsh independence (Welsh: Annibyniaeth i Gymru) is the political movement advocating for Wales to become a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom.. Wales was conquered during the 13th century by Edward I of England following the killing of Llywelyn the Last, Prince of Wales.Edward introduced the royal ordinance, the Statute of Rhuddlan, in 1284, introducing English common law ...

ABSTRACT. This discussion paper explores the evolution of Wales' new national curriculum. Launched in 2022 and reflective of a new international trend in curriculum reform, Curriculum for Wales is founded on the idea that key decisions related to teaching and learning are best made in schools and at the site of practice. The principle of subsidiarity is championed as a way of empowering ...

Another major reason why the benefits of bilingualism may be untapped in Wales may have to do with the way Welsh is taught, particularly in primary schools. Many of the teachers participating in the research commented on the fact that children are not being taught Welsh in a way that will support language-learning more widely.

Wales Essays. The Hierarchical Structure and Appeals Process in the Court and Tribunal System of England and Wales. Introduction England and Wales have a court and tribunal system that is fundamental to the country's legal framework to serve in dispute resolution, maintain justice, and protect laws (Slapper & Kelly, 2003). ...

Collections of monographs, essays, etc. Prefer subclass AS for collections published under the auspices of learned bodies (Institutions or ... 851-854 New South Wales (Table A9) 861-864 Queensland (Table A9) 866-869 South Australia (Table A9) 871-874 Tasmania (Table A9) 876-879 Victoria (Table A9) ...

Guest Essay. Britain's Next Prime Minister Has Shown Us Who He Is, and It's Not Good. July 3, 2024. ... putting him in charge of criminal prosecutions in England and Wales. Professional ...