No products in the cart.

Successful Harvard Essays

Harvard essays →, harvard mentors →.

Harvard Supplemental Essay: Travel, living, or working experiences in your own or other communities.

Travel, living, or working experiences in your own or other communities. I have had a fascination with the people, languages and cultures of Spain since…...

Harvard Supplemental Essay: What you would want your future college roommate to know about you

What you would want your future college roommate to know about you? Hello roomie! It’s nice to be able to talk to you about myself…...

Harvard Common App Essay: Evaluate a Significant Experience.

Evaluate a significant experience, achievement, risk you have taken, or ethical dilemma you have faced and its impact on you. The most gratifyingly productive and…...

Harvard Common App Essay: Evaluate a significant experience.

Evaluate a significant experience, achievement, risk you have taken, or ethical dilemma you have faced and its impact on you. The Cayman Islands, our home,…...

Harvard Common App Essay: Share an essay on any topic of your choice.

Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you’ve already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one…...

Harvard Supplemental Essay: Elaborate on One of Your Extracurricular Activities or Work Experiences

Short answer — Please briefly elaborate on one of your extracurricular activities or work experiences in the space below. As my cursor hits “refresh” at…...

Harvard Essay Prompts

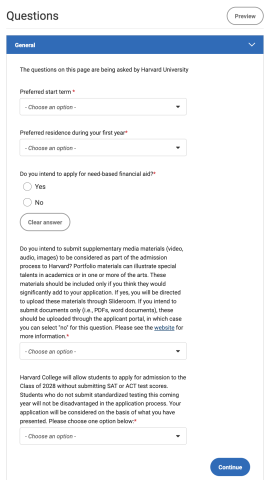

Harvard University requires the Common Application, with its 250-650 word essay requirement, as well as their own short essay questions, included below.

Harvard University Supplemental Essay Prompts

Please briefly elaborate on one of your extracurricular activities or work experiences. (50-150 words) Your intellectual life may extend beyond the academic requirements of your…...

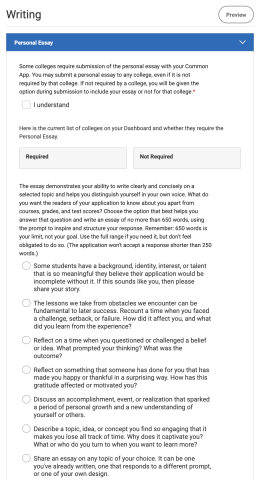

Common Application Essay Prompts

The Common App Essay for 2020-2021 is limited to 250-650 word responses. You must choose one prompt for your essay. Some students have a background,…...

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write the Harvard University Essays 2023-2024

Harvard University, perhaps the most prestigious and well-known institution in the world, is the nation’s oldest higher learning establishment with a founding date of 1636. Boasting an impressive alumni network from Sheryl Sandberg to Al Gore, it’s no surprise that Harvard recruits some of the top talents in the world.

It’s no wonder that students are often intimidated by Harvard’s extremely open-ended supplemental essays. However, CollegeVine is here to help and offer our guide on how to tackle Harvard’s supplemental essays.

Read this Harvard essay example to inspire your own writing.

How to Write the Harvard University Supplemental Essays

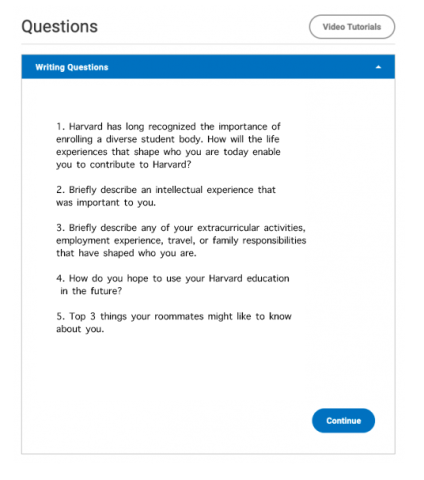

Prompt 1: Harvard has long recognized the importance of enrolling a diverse student body. How will the life experiences that shape who you are today enable you to contribute to Harvard? (200 words)

Prompt 2: Briefly describe an intellectual experience that was important to you. (200 words)

Prompt 3: Briefly describe any of your extracurricular activities, employment experience, travel, or family responsibilities that have shaped who you are. (200 words)

Prompt 4: How do you hope to use your Harvard education in the future? (200 words)

Prompt 5: Top 3 things your roommates might like to know about you. (200 words)

Harvard has long recognized the importance of enrolling a diverse student body. How will the life experiences that shape who you are today enable you to contribute to Harvard? (200 words)

Brainstorming Your Topic

This prompt is a great example of the classic diversity supplemental essay . That means that, as you prepare to write your response, the first thing you need to do is focus in on some aspect of your identity, upbringing, or personality that makes you different from other people.

As you start brainstorming, do remember that the way colleges factor race into their admissions processes will be different this year, after the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in June. Colleges can still consider race on an individual level, however, so if you would like to write your response about how your racial identity has impacted you, you are welcome to do so.

If race doesn’t seem like the right topic for you, however, keep in mind that there are many other things that can make us different, not just race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and the other aspects of our identities that people normally think of when they hear the word “diversity.” That’s not to say that you can’t write about those things, of course. But don’t worry if you don’t feel like those things have played a significant role in shaping your worldview. Here are some examples of other topics that could support a strong essay:

- Moving to several different cities because of your parents’ jobs

- An usual hobby, like playing the accordion or making your own jewelry

- Knowing a lot about a niche topic, like Scottish castles

The only questions you really need to ask yourself when picking a topic are “Does this thing set me apart from other people?” and “Will knowing this thing about me give someone a better sense of who I am overall?” As long as you can answer “yes” to both of those questions, you’ve found your topic!

Tips for Writing Your Essay

Once you’ve selected a topic, the question becomes how you’re going to write about that topic in a way that helps Harvard admissions officers better understand how you’re going to contribute to their campus community. To do that, you want to connect your topic to some broader feature of your personality, or to a meaningful lesson you learned, that speaks to your potential as a Harvard student.

For example, perhaps your interest in Scottish castles has given you an appreciation for the strength of the human spirit, as the Scots were able to persevere and build these structures even in incredibly remote, cold parts of the country. Alternatively, maybe being half Puerto Rican, but not speaking Spanish, has taught you about the power of family, as you have strong relationships even with relatives you can’t communicate with verbally.

Remember that, like with any college essay, you want to rely on specific anecdotes and experiences to illustrate the points you’re making. To understand why, compare the following two excerpts from hypothetical essays.

Example 1: “Even though I can’t speak Spanish, and some of my relatives can’t speak English, whenever I visit my family in Puerto Rico I know it’s a place where I belong. The island is beautiful, and I especially love going to the annual party at my uncle’s house.”

Example 2: “The smell of the ‘lechón,’ or suckling pig greets me as soon as I enter my uncle’s home, even before everyone rushes in from the porch to welcome me in rapid-fire Spanish. At best, I understand one in every ten words, but my aunt’s hot pink glasses, the Caribbean Sea visible through the living room window, and of course, the smell of roasting pork, tell me, wordlessly yet undeniably, that I’m home.”

Think about how much better we understand this student after Example 2. If a few words were swapped out, Example 1 could’ve been written by anyone, whereas Example 2 paints us a clear picture of how this student’s Puerto Rican heritage has tangibly impacted their life.

Mistakes to Avoid

The biggest challenge with this particular “Diversity” essay is the word count. Because you only have 200 words to work with, you don’t have space to include more than one broader takeaway you’ve learned from this aspect of your identity.

Of course, people are complicated, and you’ve likely learned many things from being Puerto Rican, or from being interested in Scottish castles. But for the sake of cohesion, focus on just one lesson. Otherwise your essay may end up feeling like a bullet-point list of Hallmark card messages, rather than a thoughtful, personal, reflective piece of writing.

The other thing you want to avoid is writing an essay that’s just about your topic. Particularly since you’re going to be writing about an aspect of your identity that’s important to you, you’ll likely have a lot to say just about that. If you aren’t careful, you may burn through all 200 words without getting to the broader significance of what this piece of your personality says about who you are as a whole.

That component, however, is really the key to a strong response. Harvard receives over 40,000 applications a year, which means that, whether you write about being Puerto Rican or Scottish castles, it’s likely someone else is writing about something similar.

That doesn’t mean you need to agonize over picking something absolutely nobody else is writing about, as that’s practically impossible. All it means is that you need to be clear about how this aspect of your identity has shaped you as a whole, as that is how your essay will stand out from others with similar topics.

Briefly describe an intellectual experience that was important to you. (200 words)

Harvard admissions officers are being considerate here, as they’re telling you explicitly what they would like you to write about. Of course, there are still nuances to the prompt, but in terms of brainstorming, just ask yourself: What is an intellectual experience that’s been important to me?

Keep in mind that “intellectual” doesn’t necessarily mean “academic.” You absolutely can write a great response about a paper, project, or some other experience you had through school. But you could also write about attending a performance by the Berlin Philharmonic, or about a book you read for fun that made a big impact on you. So long as the experience was intellectually stimulating, you can write a strong essay about it.

Once you’ve picked an experience, the key is to describe it in a way that shows Harvard admissions officers how this experience has prepared you to contribute to their classrooms, and campus community as a whole. In other words, don’t just tell them what you did, but also what you learned and why that matters for understanding what kind of college student you’ll be.

For example, say you choose to write about a debate project you did in your American history class, where you had to prepare for both sides and only learned which one you would actually be defending on the day of the debate. You could describe how, although you came into the project with pre-existing opinions about the topic, the preparation process taught you that, if you’re thoughtful and open-minded, you can usually find merit and logic even in the polar opposite position from your own.

Alternatively, you could write about a book you read that had been translated from Danish, and how reading it got you interested in learning more about how to translate a text as faithfully as possible. After watching many interviews with translators and reading a book about translation, you have learned that sometimes, the most literal translation doesn’t capture the spirit from the original language, which to you is proof that, in any piece of writing, the human element is at least as important as the words on the page.

Notice that both of these examples include broader reflections that zoom out from the particular experiences, to show what you took away from them: increased open-mindedness to different perspectives, for the first, and a more nuanced understanding of what makes art, art, in the case of the second.

A strong response must include this kind of big-picture takeaway, as it shows readers two things. First, that you can reflect thoughtfully on your experiences and learn from them. And second, it shows them a skill or perspective you’d be bringing with you to Harvard, which gives them a better sense of how you’d fit into their campus community.

The only real thing you need to watch out for is accidentally selecting an experience that, for whatever reason, doesn’t allow you to incorporate the kind of bigger-picture takeaway described above. Maybe the experience just happened, so you’re still in the process of learning from it. Or maybe the lessons you learned are too nuanced to describe in 200 words.

Whatever this reason, if you find yourself unable to articulate the broader significance of this experience, head back to the drawing board, to select one that works better for this prompt. What you don’t want to do is try to force in a takeaway that doesn’t really fit, as that will make your essay feel generic or disjointed, since the “moral of the story” won’t clearly connect to the story itself.

Briefly describe any of your extracurricular activities, employment experience, travel, or family responsibilities that have shaped who you are. (200 words)

This is a textbook example of the “Extracurricular” essay . As such, what you need to do is well-defined, although it’s easier said than done: select an extracurricular activity that has, as Harvard says, “shaped who you are,” and make sure you’re able to articulate how it’s been formative for you.

As you brainstorm which extracurricular you want to write about, note that the language of the prompt is pretty open-ended. You write about “any” activity, not just one you have a lot of accolades in, and you don’t even have to write about an activity—you can also write about a travel experience, or family responsibility.

If the thing that immediately jumps to mind is a club, sport, volunteer experience, or other “traditional” extracurricular, that’s great! Run with that. But if you’re thinking and nothing in that vein seems quite right, or, alternatively, you’re feeling bold and want to take a creative approach, don’t be afraid to get outside the box. Here are some examples of other topics you could write a strong essay about:

- A more hobby-like extracurricular, like crocheting potholders and selling them on Etsy

- Driving the Pacific Coast Highway on your own

- Caring for your family’s two large, colorful macaws

These more creative topics can do a lot to showcase a different side of you, as college applications have, by their nature, a pretty restricted scope, and telling admissions officers about something that would never appear on your resume or transcript can teach them a lot about who you are. That being said, the most important thing is that the topic you pick has genuinely been formative for you. Whether it’s a conventional topic or not, as long as that personal connection is there, you’ll be able to write a strong essay about it.

The key to writing a strong response is focusing less on the activity itself, and more on what you’ve learned from your involvement in it. If you’re writing about a more conventional topic, remember that admissions officers already have your activities list. You don’t need to say “For the last five years, I’ve been involved in x,” because they already know that, and when you only have 200 words, wasting even 10 of them means you’ve wasted 5% of your space.

If you’re writing about something that doesn’t already show up elsewhere in your application, you want to provide enough details for your reader to understand what you did, but not more than that. For example, if you’re writing about your road trip, you don’t need to list every city you stopped in. Instead, just mention one or two that were particularly memorable.

Rather than focusing on the facts and figures of what you did, focus on what you learned from your experience. Admissions officers want to know why your involvement in this thing matters to who you’ll be in college. So, think about one or two bigger picture things you learned from it, and center your response around those things.

For example, maybe your Etsy shop taught you how easy it is to bring some positivity into someone else’s life, as crocheting is something you would do anyways, and the shop just allows you to share your creations with other people. Showcasing this uplifting, altruistic side of yourself will help admissions officers better envision what kind of Harvard student you’d be.

As always, you want to use specific examples to support your points, at least as much as you can in 200 words. Because you’re dealing with a low word count, you probably won’t have space to flex your creative writing muscles with vivid, immersive descriptions.

You can still incorporate anecdotes in a more economical way, however. For example, you could say “Every morning, our scarlet macaw ruffles her feathers and greets me with a prehistoric chirp.” You’re not going into detail about what her feathers look like, or where this scene is happening, but it’s still much more engaging than something like “My bird always says hello to me in her own way.”

The most common pitfall with an “Extracurricular” essay is describing your topic the way you would on your resume. Don’t worry about showing off some “marketable skill” you think admissions officers want to see, and instead highlight whatever it is you actually took away from this experience, whether it’s a skill, a realization, or a personality trait. The best college essays are genuine, as admissions officers feel that honesty, and know they’re truly getting to know the applicant as they are, rather than some polished-up version.

Additionally, keep in mind that, like with anything in your application, you want admissions officers to learn something new about you when reading this essay. So, if you’ve already written your common app essay about volunteering at your local animal shelter, you shouldn’t also write this essay about that experience. Your space in your application is already extremely limited, so don’t voluntarily limit yourself even further by repeating yourself when you’re given an opportunity to say something new.

How do you hope to use your Harvard education in the future? (200 words)

Although the packaging is a little different, this prompt has similarities to the classic “Why This College?” prompt . That means there are two main things you want to do while brainstorming.

First, identify one or two goals you have for the future—with just 200 words, you won’t have space to elaborate on any more than that. Ideally, these should be relatively concrete. You don’t have to have your whole life mapped out, but you do need to be a lot more specific than “Make a difference in the world.” A more zoomed-in version of that goal would be something like “Contribute to conservation efforts to help save endangered species,” which would work.

Second, hop onto Harvard’s website and do some research on opportunities the school offers that would help you reach your goals. Again, make sure these are specific enough. Rather than a particular major, which is likely offered at plenty of other schools around the country, identify specific courses within that major you would like to take, or a professor in the department you would like to do research with. For example, the student interested in conservation might mention the course “Conservation Biology” at Harvard.

You could also write about a club, or a study abroad program, or really anything that’s unique to Harvard, so long as you’re able to draw a clear connection between the opportunity and your goal. Just make sure that, like with your goals, you don’t get overeager. Since your space is quite limited, you should choose two, or maximum three, opportunities to focus on. Any more than that and your essay will start to feel rushed and bullet point-y.

If you do your brainstorming well, the actual writing process should be pretty straightforward: explain your goals, and how the Harvard-specific opportunities you’ve selected will help you reach them.

One thing you do want to keep in mind is that your goals should feel personal to you, and the best way to accomplish that is by providing some background context on why you have them. This doesn’t have to be extensive, as, again, your space is limited. But compare the following two examples, written about the hypothetical goal of helping conservation efforts from above, to get an idea of what we’re talking about:

Example 1: “As long as I can remember, I’ve loved all kinds of animals, and have been heartbroken by the fact that human destruction of natural resources could lead to certain species’ extinction.”

Example 2: “As a kid, I would sit in front of the aquarium’s walrus exhibit, admiring the animal’s girth and tusks, and dream about seeing one in the wild. Until my parents regretfully explained to me that, because of climate change, that was unlikely to ever happen.”

The second example is obviously longer, but not egregiously so: 45 words versus 31. And the image we get of this student sitting and fawning over a walrus is worth that extra space, as we feel a stronger personal connection to them, which in turn makes us more vicariously invested in their own goal of environmental advocacy.

As we’ve already described in the brainstorming section, the key to this essay is specificity. Admissions officers want you to paint them a picture of how Harvard fits into your broader life goals. As we noted earlier, that doesn’t mean you have to have everything figured out, but if you’re too vague about your goals, or how you see Harvard helping you reach them, admissions officers won’t see you as someone who’s prepared to contribute to their campus community.

Along similar lines, avoid flattery. Gushy lines like “At Harvard, every day I’ll feel inspired by walking the same halls that countless Nobel laureates, politicians, and CEOs once traversed” won’t get you anywhere, because Harvard admissions officers already know their school is one of the most prestigious and famous universities in the world. What they don’t know is what you are going to bring to Harvard that nobody else has. So, that’s what you want to focus on, not vague, surface-level attributes of Harvard related to its standing in the world of higher education.

Top 3 things your roommates might like to know about you. (200 words)

Like Prompt 2, this prompt tells you exactly what you need to brainstorm: three things a roommate would like to know about you. However, also like Prompt 2, while this prompt is direct, it’s also incredibly open-ended. What really are the top three things you’d like a complete stranger to know about you before you live together for nine months?

Questions this broad can be hard to answer, as you might not know where to start. Sometimes, you can help yourself out by asking yourself adjacent, but slightly more specific questions, like the following:

- Do you have any interests that influence your regular routine? For example, do you always watch the Seahawks on Sunday, or are you going to be playing Taylor Swift’s discography on repeat while you study?

- Look around your room—what items are most important to you? Do you keep your movie ticket stubs? Are you planning on taking your photos of your family cat with you to college?

- Are there any activities you love and already know you’d want to do with your roommate, like weekly face masks or making Christmas cookies?

Hopefully, these narrower questions, and the example responses we’ve included, help get your gears turning. Keep in mind that this prompt is a great opportunity to showcase sides of your personality that don’t come across in your grades, activities list, or even your personal statement. Don’t worry about seeming impressive—admissions officers don’t expect you to read Shakespeare every night for two hours. What they want is an honest, informative picture of what you’re like “behind the scenes,” because college is much more than just academics.

Once you’ve selected three things to write about, the key to the actual essay is presenting them in a logical, cohesive, efficient way. That’s easier said than done, particularly if the three things you’ve picked are quite different from each other.

To ensure your essay feels like one, complete unit, rather than three smaller ones stuck together, strong transitions will be crucial. Note that “strong” doesn’t mean “lengthy.” Just a few words can go a long way towards helping your essay flow naturally. To see what we mean here, take the following two examples:

Example 1: “Just so you know, every Sunday I will be watching the Seahawks, draped in my dad’s Steve Largent jersey. They can be a frustrating team, but I’ll do my best to keep it down in case you’re studying. I also like to do facemasks, though. You’re always welcome to any of the ones I have in my (pretty extensive) collection.”

Example 2: “Just so you know, every Sunday I will be watching the Seahawks, draped in my dad’s Steve Largent jersey. But if football’s not your thing, don’t worry—once the game’s over, I’ll need to unwind anyways, because win or lose the Hawks always find a way to make things stressful. So always feel free to join me in picking out a face mask from my (pretty extensive) collection, and we can gear up for the week together.”

The content in both examples is the same, but in the first one, the transition from football to facemasks is very abrupt. On the other hand, in the second example the simple line “But if football’s not your thing, don’t worry” keeps things flowing smoothly.

There’s no one right way to write a good transition, but as you’re polishing your essay a good way to see if you’re on the right track is by asking someone who hasn’t seen your essay before to read it over and tell you if there are any points that made them pause. If the answer is yes, your transitions probably still need more work.

Finally, you probably noticed that the above examples are both written in a “Dear roomie” style, as if you’re actually speaking directly to your roommate. You don’t have to take this exact approach, but your tone should ideally be light and fun. Living alone for the first time, with other people your age, is one of the best parts of college! Plus, college applications are, by their nature, pretty dry affairs for the most part. Lightening things up in this essay will give your reader a breath of fresh air, which will help them feel more engaged in your application as a whole.

Harvard is doing you a favor here by keeping the scope of the essay narrow—they ask for three things, not more. As we’ve noted many times with the other supplements, 200 words will be gone in a flash, so don’t try to cram in extra things. It’s not necessary to do that, because admissions officers have only asked for three, and trying to stuff more in will turn your essay into a list of bullet points, rather than an informative piece of writing about your personality.

Finally, as we’ve hinted at a few times above, the other thing you want to avoid is using this essay as another opportunity to impress admissions officers with your intellect and accomplishments. Remember, they have your grades, and your activities list, and all your other essays. Plus, they can ask you whatever questions they want—if they wanted to know about the most difficult book you’ve ever read, they would. So, loosen up, let your hair down, and show them you know how to have fun too!

Where to Get Your Harvard Essays Edited

Do you want feedback on your Harvard essays? After rereading your essays countless times, it can be difficult to evaluate your writing objectively. That’s why we created our free Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays.

If you want a college admissions expert to review your essay, advisors on CollegeVine have helped students refine their writing and submit successful applications to top schools. Find the right advisor for you to improve your chances of getting into your dream school!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Test Preparation

- College & High School

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

50 Successful Harvard Application Essays, 5th Edition: What Worked for Them Can Help You Get into the College of Your Choice Paperback – May 9, 2017

Fifty all-new essays that got their authors into Harvard - with updated statistics, analysis, and complete student profiles - showing what worked, what didn’t, and how you can do it, too. With talented applicants coming from top high schools as well as the pressure to succeed from family and friends, it’s no wonder that writing college application essays is one of the most stressful tasks high schoolers face. To help, this completely new edition of 50 Successful Harvard Application Essays , edited by the staff of the Harvard Crimson , gives readers the most inspiring approaches, both conventional and creative, that won over admissions officers at Harvard University, the nation’s top-ranked college. From chronicling personal achievements to detailing unique talents, the topics covered in these essays open applicants up to new techniques to put their best foot forward. It teaches students how to: - Get started - Stand out - Structure the best possible essay - Avoid common pitfalls Each essay in this collection is from a Harvard student who made the cut, is accompanied by a student profile that includes SAT scores and grades, and is followed by a detailed analysis by the staff of the Harvard Crimson that shows readers how they can approach their own stories and ultimately write their own high-caliber essay. 50 Successful Harvard Application Essays ’ all-new examples and straightforward advice make it the first stop for college applicants who are looking to craft essays that get them accepted to the school of their dreams.

- Print length 224 pages

- Language English

- Publication date May 9, 2017

- Dimensions 5.45 x 0.75 x 8.2 inches

- ISBN-10 9781250127556

- ISBN-13 978-1250127556

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- ASIN : 1250127556

- Publisher : St. Martin's Griffin; 5th edition (May 9, 2017)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 224 pages

- ISBN-10 : 9781250127556

- ISBN-13 : 978-1250127556

- Item Weight : 6.9 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.45 x 0.75 x 8.2 inches

- #12 in College Guides (Books)

- #34 in College Entrance Test Guides (Books)

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Customer Review: No good

About the author

Staff of the harvard crimson.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Book details

50 Successful Harvard Application Essays, 5th Edition

What Worked for Them Can Help You Get into the College of Your Choice

Author: Staff of the Harvard Crimson

M ICHAEL B ERVELL Hometown : Mukilteo, Washington, USA High School : Public school, 550 students in graduating class Ethnicity : Black, African American Gender : Male GPA : 3.9 out of 4.0 SAT : Reading 800, Math 800, Writing 800 ACT : 35 SAT Subject Tests Taken : Mathematics Level 1, Mathematics Level 2, Physics, World History Extracurriculars : Student body president; newspaper editor in chief; varsity debate captain; Hugs for Ghana (nonprofit) cofounder and executive director; GMAZ Jazz Quartet cofounder, drummer, and manager Awards : International Build-a-Bear Workshop Huggable Heroes Award, National Bank of America Student Leader Delegate, Evergreen Boys State Delegate and Governor, National Radio Disney Hero for Change Award, National Achievement Scholar, National Coca-Cola Scholar Major : Philosophy and Computer Science ESSAY “A-one,” I adjust my earphones. “A-two,” I wipe the sweat off my sticks. “A-one-two-three-four!” The sharp rhythm of Mr. Dizzy Gillespie’s iconic bebop tune “Salt Peanuts” rattles through my head like saline seeds as I silently count myself off. Then—without a hitch—Gillespie, his quintet, and I are off. My left foot taps the AP biology textbook, my sticks bounce along the metal frame of my bed, and my soul dances to the beat I am creating. This makeshift drum set is a liberating entrance into an abstract world where I am free to express myself. As I sit on the edge of my bed imitating the monophonic flow of drummer Max Roach, I close my eyes and envision myself performing onstage with world-renowned Gillespie. We stand before thousands of people, steeped in the spotlight’s brilliant glare, and as we play my arms become a flurry of motion when, suddenly, crack ! I snap back into reality and my eyes shoot open only to realize that the moment of pure ecstasy had been interrupted—another broken drumstick! Smiling, I pick up the pieces and walk toward a worn, old, black Ikea desk in the corner of my room. Since 5th grade, my DrumDrawer has been the keeper of every pair of new and broken drumsticks I have ever owned. I pull open the big bottom drawer and stand admiring the sacred splinters for a brief moment before finally dropping in this latest offering. The sticks in my small pine sepulcher illustrate the quintessential facets of who I am—a musician, leader, and philanthropist. While most people typically collect rocks or baseball cards, I collect musical phrases from my life and store them in this drawer. As I reach to the bottom, my fingers wrap around two white Vic Firth sticks. Rubbing my fingers along the bumps on the wood, I grin. This exclusive pair shared my accomplishments of playing jazz under the Eiffel Tower in Paris, drumming in award-winning spring musicals, and being inducted into the National Tri-M Music Honor Society. Moreover, these sticks not only inspired me to persevere as I cofounded, managed, and drummed in the GMAZ Jazz Quartet, but they also instilled confidence in me when I needed it most. After I decided to run for Student Body President of my 2,200-student high school in what turned out to be a competitive election against two of my closest friends, these tattered drumsticks soothed and comforted me. Despite turbulent weeks of campaigning and preparing a daunting school-wide campaign speech, I always looked forward to returning to my bedroom and playing my favorite jazz melodies. The ups and downs of musical arrangements never failed to strike a chord. Reminiscing, I twirl the white drumsticks between my fingers and realize that they also profoundly influenced my view of service. Once a month, these wooden wonders and I would trek from my desk to the local retirement home where we performed with other musicians in monthly “Play-It-Forward” retirement home concerts. On these Friday nights, my sticks danced on the drums, our music floated throughout the concert hall, elderly faces glowed, and I was free to let out my creative exuberance. In organizing dozens of these events, I have shared with both peers and audience members my own musical definition of altruism. I return my Vic Firth sticks to the drawer and contentedly appreciate the collection of memories. While the wooden contents physically have no other value than, perhaps, kindling a small fire, I cannot bear to part with them. Someday the sticks will go, I realize, but the music will not. Fresh pair of sticks in hand, I slowly shut the DrumDrawer, return to my bed, and count myself off, eyes closed, to John Coltrane’s jazz rendition of “My Favorite Things” by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein. “A-one, a-two, a-one-two-three-four!” REVIEW Right from the introduction, readers are thrown into the vibrant and colorful world that Michael’s essay creates. Passion for a musical instrument is a topic that is doubtlessly written about by many applicants, but Michael differentiates himself by using his passion for drumming to demonstrate his stylistic flair, cleverly finding ways to discuss his other, non-musical accomplishments and pursuits. Michael clearly aims to communicate that he is a “musician, leader, and philanthropist” throughout his essay—a goal he successfully accomplishes. His musical talent and passion come alive through the vivid imagery and onomatopoeia that he uses. To demonstrate leadership, he shows how he dealt with a difficult situation maturely. Finally, his dedication to volunteer work is seamlessly worked into the essay when he recalls playing concerts at a retirement home. Michael roots the essay in the physical space of his bedroom, but chooses a place that allows him to be creative and cover a lot of aspects of himself that might not be accessible in other parts of his application. The full-circle ending is a nice touch to further root the essay in the prompt. Michael does a wonderful job of demonstrating that you don’t need a particularly unique topic to create a memorable essay. —Mia Karr J ANG L EE Hometown : Flower Mound, Texas, USA High School : Public school, 816 students in graduating class Ethnicity : Asian Gender : Male GPA : 4.0 out of 4.0 SAT : Reading 800, Math 740, Writing 790 ACT : n/a SAT Subject Tests Taken : Mathematics Level 2, Chemistry Extracurriculars : President of art club / National Art Honor Society, vice president of Science National Honor Society, founding member and vice president of creative engagement and design for 501(c)3 nonprofit Raise4aCause, volunteer at church summer school Awards : PSAT semifinalist, Welch Summer Scholar, 1 Scholastic Silver Key and 2 Gold Keys, artwork exhibited at the Texas Legislative Budget Board and part of the Texas Art Education Association traveling exhibition, Gold Seal at UIL Texas art competition (highest possible award given to .6% of artworks out of over twenty thousand submissions) Major : Visual and Environmental Studies ESSAY Like it does on most nights, the smell of toxic fumes drifts through my room. Occasionally washing my paintbrushes in turpentine oil thinner, I am uncomfortably aware that these vapors can cause brain damage, lung cancer, and chronic respiratory problems. My lifelong passion is killing me— literally. Yet, this smell is strangely comforting. It blankets me with a sense of security I find nowhere else. An artist at the core, my paint-smeared heart pumps pigments of red through veins and arteries—the love for painting permeates every part of my body and has transformed me. By constantly observing subtle details of objects, breathtaking spectrums of color, and the interactions of lights and darks, my perception of the world has shifted. I walk down the school hallway during passing period. Carried by a stream of teenage bodies, I notice ceiling lights scattering among clothes and locks of glossy hair. Looking down, shadows crisscross and overlap on the laminated floor to create a kaleidoscope of dancing silhouettes. Faces draw my attention—delicate hues of rosy pink on tips of ears and softly chiseled curves of bone. I observe my surroundings from an artist’s perspective, fully immersed in a state of perpetual learning. Ultimately, my goal as an artist is to give my art personal, profound depth that transcends aesthetic purpose or technical skill. Paintings do not have to be of flowers or landscapes; they can portray story, emotion, and experience. Consequently, my art is inspired by personal experiences and observations. I hope to convey a fresh perspective of my life through strokes of color. The ambition of creating depth in my art forces me to reflect on myself as I continually ask why I am painting what I am painting. And because of the rigorous reflection of my values and experiences, I am given a greater sense of self-identity. This overwhelming position as an artist is humbling, teaching me an appreciation for self-worth often neglected or trivialized in a fast-paced American lifestyle. I want to show others this same value through my art so they can slow down to recognize and appreciate the value of their own lives. Wonderland Unknown, a painting based on my favorite childhood story, Alice in Wonderland, depicts a rabbit in a forest of overgrown mushrooms and twisted trees. The piece builds on the idea that children’s innate creativity and capacity for imagination are stifled as they mature. Growing up, I began to feel estranged from the tale because it turned unrealistically ridiculous, a personal testimony to the slow deterioration of childhood wonder. Painting Wonderland Unknown was an epiphany—I realized that creativity is inherent: a universal thread within all of us that stitches humanity together. Most importantly, it is a trait that should be nurtured and valued instead of taken for granted. Truly, art is a world of possibility and a world I would like to share. It is a place where one is encouraged to break rules, be unapologetically audacious, and take pride in unorthodoxy. Ready to play creator of my universe, I rule with brush in one hand and palette in the other, painting because of a chance to explore this liberating world and discover myself through it. And in the end, art will always stay a constant in my life, forever my private sanctuary of creativity and personal expression. A place where I am infinite. I feel relieved knowing that the smell of turpentine will always comfort me. It is a thin, oily smell of ironic undertones, vaguely nauseating and coffee-ground bitter. It is a smell that has given me life. REVIEW Jang’s essay is filled with beautiful phrasing and flowery descriptions, which shows off his writing skills and creativity. One of the biggest strengths of the essay is how Jang pairs explanation of art’s function in his life with an artistic analysis of the piece Wonderland Unknown . Being able to write exceedingly well in a distinctive narrative form proves to be a strength for Jang. His essay weds two distinct types of writing—narrative and analytical—together, which is the very essence of what a good college essay should be. But, rather than present a single, overarching narrative, the writer takes the reader through separate vignettes: a crowded hallway, his work space at home, the scene depicted in the painting—all of which combine to provide a distinct and colorful look into the writer’s relationship with art. —Brandon J. Dixon Copyright © 2017 by the Staff of The Harvard Crimson

Buy This Book From:

Reviews from goodreads, about this book, book details.

Fifty all-new essays that got their authors into Harvard - with updated statistics, analysis, and complete student profiles - showing what worked, what didn’t, and how you can do it, too. With talented applicants coming from top high schools as well as the pressure to succeed from family and friends, it’s no wonder that writing college application essays is one of the most stressful tasks high schoolers face. To help, this completely new edition of 50 Successful Harvard Application Essays , edited by the staff of the Harvard Crimson , gives readers the most inspiring approaches, both conventional and creative, that won over admissions officers at Harvard University, the nation’s top-ranked college. From chronicling personal achievements to detailing unique talents, the topics covered in these essays open applicants up to new techniques to put their best foot forward. It teaches students how to: - Get started - Stand out - Structure the best possible essay - Avoid common pitfalls Each essay in this collection is from a Harvard student who made the cut, is accompanied by a student profile that includes SAT scores and grades, and is followed by a detailed analysis by the staff of the Harvard Crimson that shows readers how they can approach their own stories and ultimately write their own high-caliber essay. 50 Successful Harvard Application Essays ’ all-new examples and straightforward advice make it the first stop for college applicants who are looking to craft essays that get them accepted to the school of their dreams.

Imprint Publisher

St. Martin's Griffin

9781250127563

About the Creators

Harvard University Essay Examples (And Why They Worked)

The following essay examples were written by several different authors who were admitted to Harvard University and are intended to provide examples of successful Harvard University application essays. All names have been redacted for anonymity. Please note that Bullseye Admissions has shared these essays with admissions officers at Harvard University in order to deter potential plagiarism.

For more help with your Harvard supplemental essays, check out our 2020-2021 Harvard University Essay Guide ! For more guidance on personal essays and the college application process in general, sign up for a monthly plan to work with an admissions coach 1-on-1.

Please briefly elaborate on one of your extracurricular activities or work experiences. (50-150 words)

Feet moving, eyes up, every shot back, chants the silent mantra in my head. The ball becomes a beacon of neon green as I dart forward and backward, shuffling from corner to far corner of the court, determined not to let a single point escape me. With bated breath, I swing my racquet upwards and outwards and it catches the ball just in time to propel it, spinning, over the net. My heart soars as my grinning teammates cheer from the sidelines.

While I greatly value the endurance, tenacity, and persistence that I have developed while playing tennis throughout the last four years, I will always most cherish the bonds that I have created and maintained each year with my team.

Why this Harvard essay worked: From an ex-admissions officer

When responding to short essays or supplements, it can be difficult to know which info to include or omit. In this essay, the writer wastes no time and immediately captivates the reader. Not only are the descriptions vivid and compelling, but the second portion highlights what the writer gained from this activity. As an admissions officer, I learned about the student’s level of commitment, leadership abilities, resiliency, ability to cooperate with others, and writing abilities in 150 words.

I founded Teen Court at [High School Name Redacted] with my older brother in 2016. Teen Court is a unique collaboration with the Los Angeles Superior Court and Probation Department, trying real first-time juvenile offenders from all over Los Angeles in a courtroom setting with teen jurors. Teen Court’s foundational principle is restorative justice: we seek to rehabilitate at-risk minors rather than simply punish them. My work provides my peers the opportunity to learn about the justice system. I put in over fifty hours just as Secretary logging court attendance, and now as President, I mentor Teen Court attendees. My goal is to improve their empathy and courage in public speaking, and to expand their world view. People routinely tell me their experience with Teen Court has inspired them to explore law, and I know the effort I devoted bringing this club to [High School Name Redacted] was well worth it.

This writer discussed a passion project with a long-lasting impact. As admissions officers, we realize that post-secondary education will likely change the trajectory of your life. We hope that your education will also inspire you to change the trajectory of someone else’s life as well. This writer developed an organization that will have far-reaching impacts for both the juvenile offenders and the attendees. They saw the need for this service and initiated a program to improve their community. College Admissions Quiz: If you’re planning on applying to Harvard, you’ll want to be as prepared as possible. Take our quiz below to put your college admissions knowledge to the test!

Harvard University Supplemental Essay Option: Books Read During the Last Twelve Months

Reading Frankenstein in ninth grade changed my relationship to classic literature. In Frankenstein , I found characters and issues that resonate in a modern context, and I began to explore the literary canon outside of the classroom. During tenth grade, I picked up Jane Eyre and fell in love with the novel’s non-traditional heroine whose agency and cleverness far surpassed anything that I would have imagined coming from the 19th century. I have read the books listed below in the past year.

- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Purple Hibiscus *

- Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger *

- Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility

- Aphra Behn, The Fair Jilt ♰

- Mongo Beti, Mission Terminée * (in French)

- Kate Chopin, The Awakening

- Arthur Conan-Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

- Kamel Daoud, Meursault, contre-enquête * (in French)

- Roddy Doyle, A Star Called Henry *

- Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane *

- Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

- William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying *

- Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

- E. M. Forster, Maurice

- E. M. Forster, A Passage to India

- E. M. Forster, Where Angels Fear to Tread

- Eliza Haywood, The City Jilt ♰

- Homer, The Iliad

- Christopher Isherwood, All The Conspirators

- Christopher Isherwood, A Meeting by the River

- Christopher Isherwood, Sally Bowles

- Christopher Isherwood, A Single Man

- Shirley Jackson, We Have Always Lived in the Castle

- James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

- Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis

- Franz Kafka, The Trial

- Jhumpa Lahiri, Interpreter of Maladies *

- Morrissey, Autobiography

- Rudolph Otto, The Idea of the Holy *

- Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago

- Charlotte Perkins-Gilman, Herland

- Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

- Marcel Proust, Within a Budding Grove

- Mary Renault, Fire From Heaven

- Mary Renault, The Friendly Young Ladies

- Mary Renault, The King Must Die

- Mary Renault, The Persian Boy

- J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Terre des hommes * (in French)

- Shakespeare, Hamlet *

- Mary Shelley, The Last Man

- Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead *

- Kurt Vonnegut, Breakfast of Champions

- Kurt Vonnegut, The Sirens of Titan

- Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited

- Evelyn Waugh, Scoop

- Evelyn Waugh, Vile Bodies

- Jeanette Winterson, The Passion

- Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary: A Fiction ♰

- Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights of Woman ♰

- Virginia Woolf, A Haunted House and Other Stories

- * indicates assigned reading

- ♰ indicates independent study reading

Harvard University Supplemental Essay Option: What would you want your future college roommate to know about you? (No word limit)

Hi Roomie!!!!

You probably have noticed that I put four exclamation points. Yes, I am that excited to meet you, roomie!

Also, I don’t believe in the Rule of Three. It’s completely unfair that three is always the most commonly used number. Am I biased in my feelings because four is my favorite number? Perhaps. However, you have to admit that our reason for the Rule of Three is kinda arbitrary. The Rule of Three states that a trio of events is more effective and satisfying than any other numbers. Still, the human psyche is easily manipulated through socially constructed perceptions such as beauty standards and gender roles. Is having three of everything actually influential or is it only influential because society says so? Hmm, it’s interesting to think about it, isn’t it?

But if you’re an avid follower of the Rule of three, don’t worry, I won’t judge. In fact, if there’s one thing I can promise you I will never do, it’s being judgmental. Life is too short to go around judging people. Besides, judgments are always based on socially constructed beliefs. With so many backgrounds present on campus, it really would be unfair if we start going around judging people based on our own limited beliefs. My personal philosophy is “Mind your own business and let people be,” So, if you have a quirk that you’re worrying is too “weird” and are afraid your roommate might be too judgy, rest assured, I won’t be.

In fact, thanks to my non-judginess, I am an excellent listener. If you ever need to rant with someone about stressful classes, harsh gradings, or the new ridiculous plot twists of your favorite TV show (*cough* Riverdale), I am always available.

Now, I know what you are thinking. A non-judgmental and open-minded roommate? This sounds too good to be true. This girl’s probably a secret villain waiting to hear all my deepest and darkest secrets and blackmail me with them!

Well, I promise you. I am not a secret villain. I am just someone who knows how important it is to be listened to and understood.

I grew up under the communist regime of Vietnam, where freedom of speech and thought was heavily suppressed. Since childhood, I was taught to keep my opinion to myself, especially if it is contradictory to the government’s. No matter how strongly I felt about an issue, I could never voice my true opinion nor do anything about it. Or else, my family and I would face oppression from the Vietnamese government.

After immigrating to America, I have made it my mission to fight for human rights and justice. Back in Vietnam, I have let fear keep me from doing the right thing. Now, in the land of freedom, I won’t use that excuse anymore. I can finally be myself and fight for what I believe in. However, I can still remember how suffocating it was to keep my beliefs bottled up and to be silenced. Trust me, a conversation may not seem much, but it can do wonders. So, if you ever need a listener, know that I am right here.

See, I just shared with you a deep secret of mine. What secret villain would do that?

See ya soon!!!!!

[Name redacted] : )

P/S: I really love writing postscripts. So, I hope you won’t find it weird when I always end my emails, letters, and even texts with a P/S. Bye for real this time!!!!!

Harvard University Supplemental Essay Option: Unusual circumstances in your life

I would like the Harvard Admissions Committee to know that my life circumstances are far from typical. I was born at twenty-four weeks gestation, which eighteen years ago was on the cusp of viability. Even if I was born today, under those same circumstances, my prospects for leading a normal life would be grim. Eighteen years ago, those odds were worse, and I was given a less than 5% chance of survival without suffering major cognitive and physical deficits.

The first six months of my life were spent in a large neonatal ICU in Canada. I spent most of that time in an incubator, kept breathing by a ventilator. When I was finally discharged home, it was with a feeding tube and oxygen, and it would be several more months before I was able to survive without the extra tubes connected to me. At the age of two, I was still unable to walk. I engaged in every conventional and non-conventional therapy available to me, including physical and speech therapy, massage therapy, gymnastics, and several nutritional plans, to try to remedy this. Slowly, I began to make progress in what would be a long and arduous journey towards recovery.

Some of my earliest childhood memories are of repeated, often unsuccessful attempts to grip a large-diameter crayon since I was unable to hold a regular pencil. I would attempt to scrawl out letters on a page to form words, fueled by either determination or outright stubbornness, persevering until I improved. I spent countless hours trying to control my gait, eventually learning to walk normally and proving the doctors wrong about their diagnoses. I also had to learn how to swallow without aspirating because the frequent intubations I had experienced as an infant left me with a uncoordinated swallow reflex. Perhaps most prominently, I remember becoming very winded as I tried to keep up with my elementary school peers on the playground and the frustration I experienced when I failed.

Little by little, my body’s tolerance for physical exertion grew, and my coordination improved. I enrolled in martial arts to learn how to keep my balance and to develop muscle coordination and an awareness of where my limbs were at any given time. I also became immersed in competition among my elementary school peers to determine which one of us could become the most accomplished on the recorder. For each piece of music played correctly, a “belt” was awarded in the form of a brightly colored piece of yarn tied around the bottom of our recorders- meant as symbols of our achievement. Despite the challenges I had in generating and controlling enough air, I practiced relentlessly, often going in before school or during my lunch hour to obtain the next increasingly difficult musical piece. By the time the competition concluded, I had broken the school record of how far an elementary school child could advance; in doing so, my love of instrumental music and my appreciation for the value of hard work and determination was born.

Throughout my middle and high school years, I have succeeded at the very highest level both academically and musically. I was even able to find a sport that I excelled at and would later be able to use as an avenue for helping others, volunteering as an assistant coach once I entered high school. I have mentored dozens of my high school peers in developing trumpet skills, teaching them how to control one’s breathing during musical phrases and how to develop effective fingering techniques in order to perform challenging passages. I believe that my positive attitude and hard work has allowed for not only my own success, but for the growth and success of my peers as well.

My scholastic and musical achievements, as well as my leadership abilities and potential to succeed at the highest level will hopefully be readily apparent to the committee when you review my application. Perhaps more importantly, however, is the behind-the-scenes character traits that have made these possible. I believe that I can conquer any challenge put in front of me. My past achievements provide testimony to my work ethic, aptitudes and grit, and are predictive of my future potential.

Thank you for your consideration.

In this essay, the writer highlighted their resilience. At some point, we will all endure challenges and struggles, but it is how we redeem ourselves that matters. This writer highlighted their initial struggles, their dedication and commitment, and the ways in which they’ve used those challenges as inspiration and motivation to persevere and also to encourage others to do the same.

Harvard University Supplemental Essay Option: An intellectual experience (course, project, book, discussion, paper, poetry, or research topic in engineering, mathematics, science or other modes of inquiry) that has meant the most to you.

I want to be a part of something amazing, and I believe I can. The first line of the chorus springs into my mind instantaneously as my fingers experiment with chords on the piano. In this moment, as I compose the protagonist’s solo number, I speak from my heart. I envision the stage and set, the actors, the orchestra, even the audience. Growing increasingly excited, I promptly begin to create recordings so I can release the music from the confines of my imagination and share it with any willing ears.

My brother [name redacted] and I are in the process of writing a full-length, two-act musical comprised of original scenes, songs, characters. I began creating the show not only because I love to write music and entertain my friends and family, but also with the hope that I might change the way my peers view society. Through Joan, the protagonist of my musical, I want to communicate how I feel about the world.

The story centers around Joan, a high schooler, and her connection to the pilot Amelia Earhart. Ever since I saw a theatrical rendition of Amelia Earhart’s life in fifth grade, she has fascinated me as an extraordinary feminist and a challenger of society’s beliefs and standards. As I began researching and writing for the show, I perused through biographies and clicked through countless youtube documentaries about the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, astounded by her bravery and ability to overcome a troubled childhood and achieve her dream. In my musical, as Amelia transcends 20th century norms, changing the way that people regard women and flight, Joan strives to convince her peers and superiors that the worth of one’s life spans not from material success and grades, but from self-love and passion.

As I compose, the essence of each character and the mood of each scene steer the flow of each song. To me, it seems as though everything falls into place at once – as I pluck a melody out of the air, the lyrics come to me naturally as if the two have been paired all along. As I listen to the newly born principal line, I hear the tremolo of strings underscoring and the blaring of a brass section that may someday audibly punctuate each musical phrase.

The project is certainly one of the most daunting tasks I’ve ever undertaken – we’ve been working on it for almost a year, and hope to be done by January – but, fueled by my passion for creating music and writing, it is also one of the most enjoyable. I dream that it may be performed one day and that it may influence society to appreciate the success that enthusiasm for one’s relationships and work can bring.

These essay examples were compiled by the advising team at Bullseye Admissions. If you want to get help writing your Harvard University application essays from Bullseye Admissions advisors , register with Bullseye today .

Personalized and effective college advising for high school students.

- Advisor Application

- Popular Colleges

- Privacy Policy and Cookie Notice

- Student Login

- California Privacy Notice

- Terms and Conditions

- Your Privacy Choices

By using the College Advisor site and/or working with College Advisor, you agree to our updated Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy , including an arbitration clause that covers any disputes relating to our policies and your use of our products and services.

50 MBA Essays That Got Applicants Admitted To Harvard & Stanford

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share on Reddit

What Matters? and What More? is a collection of 50 application essays written by successful MBA candidates to Harvard Business School and Stanford Graduate School of Business

I sat alone one Saturday night in a boardroom in Eastern Oregon, miles from home, my laptop lighting the room. I was painstakingly reviewing a complex spreadsheet of household energy consumption data, cell by cell. ‘Why am I doing this to myself? For remote transmission lines?’…I felt dejected. I’d felt that way before, during my summer at JP Morgan, standing alone in the printing room at 3 a.m., binding decks for a paper mill merger that wouldn’t affect my life in the least.

That’s how an analyst at an MBB firm started his MBA application essay to Stanford Graduate School of Business. His point: In a well-crafted essay, he confronts the challenge of finding meaning in his work and a place where he can make a meaningful difference. That is what really matters most to him, and his answer to Stanford’s iconic MBA application essay helped get him defy the formidable odds of acceptance and gain an admit to the school.

Getting into the prestigious MBA programs at either Stanford Graduate School of Business or Harvard Business School are among the most difficult journeys any young professional can make.

NEARLY 17,000 CANDIDATES APPLIED TO HARVARD & STANFORD LAST YEAR. 1,500 GOT IN

This collection of 50 successful HBS and GSB essays, with smart commentary, can be downloaded for $60

They are two of the most selective schools, routinely rejecting nine or more out of every ten applicants. Last year alone, 16,628 candidates applied to both schools; just 1,520 gained an acceptance, a mere 9.1% admit rate.

Business school admissions are holistic, meaning that while standardized test scores and undergraduate transcripts are a critical part of the admissions process, they aren’t the whole story. In fact, the stories that applicants tell the schools in the form of essays can be a critical component of a successful application.

So what kinds of stories are successful applicants to Harvard and Stanford telling their admission officers? For the first time ever, a newly published collection of 50 of these essays from current MBA students at these two schools has been published. In ten cases, applicants share the essays they wrote in applying to both schools so you can see whether they merely did a cut-and-paste job or approached the task anew. The 188-page book, What Matters? and What More?, gains its title from the two iconic essay prompts at Harvard and Stanford.

THOUGHTFUL CRITIQUES OF THE ESSAYS

Stanford can easily boast having the most difficult question posed to MBA applicants in any given year: In 650 words or less, candidates must tell the school what matters most to them and why. Harvard gives applicants ample room to hang themselves, providing no word limit at all, “What more would you like us to know as we consider your candidacy?”

One makes this unusual collection of essays powerful are the thoughtful critiques by the founders of two MBA admissions consulting firms, Jeremy Shinewald of mbaMission and Liza Weale of Gatehouse Admissions. They write overviews of each essay in the book and then tear apart portions by paragraphs to either underline a point or address a weakness. The book became available to download for $60 a pop.

As I note in a foreword to the collection, published in partnership with Poets&Quants, the essay portion of an application is where a person can give voice to who they are, what they have achieved so far, and what they imagine their future to be. Yet crafting a powerful and introspective essay can be incredibly daunting as you stare at a blank computer screen.

APPLICANTS OPEN UP WITH INTIMATE STORIES THAT SHOW VULNERABILITY

One successful applicant to Harvard Business School begins his essay by conveying a deeply personal story: The time his father was told that he had three months to live, with his only hope being a double lung transplant. had to undergo a lung transplant. His opening line: “Despite all we had been through in recent years, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect when I asked my mother one summer evening in Singapore, ‘What role did I play during those tough times?’”

For this candidate to Stanford Graduate School of Business, the essay provided a chance to creatively engage admission readers about what matters most to him–equality-by cleverly using zip codes as a hook.

60605, 60606, 60607.

These zip codes are just one digit apart, but the difference that digit makes in someone’s life is unfathomable. I realized this on my first day as a high school senior. Leafing through my out-of- date, stained, calculus textbook, I kept picturing the new books that my friend from a neighboring (more affluent) district had. As college acceptances came in, I saw educational inequality’s more lasting effects—my friends from affluent districts that better funded education were headed to prestigious universities, while most of my classmates were only accepted by the local junior college. I was unsettled that this divergence wasn’t the students’ doing, but rather institutionalized by the state’s education system. Since this experience, I realized that the fight for education equality will be won through equal opportunity. Overcoming inequality, to ensure that everyone has a fair shake at success, is what matters most to me.

HOW AN APPLICANT TO BOTH SCHOOLS ALTERED HIS ESSAYS

Yet another candidate, who applied to both Harvard and Stanford, writes about being at but not fully present at his friend’s wedding.

The morning after serving as my friend’s best man, I was waiting for my Uber to the airport and—as usual—scrolling through my phone,” he wrote. “I had taken seemingly hundreds of photos of the event, posting in real time to social media, but had not really looked through them. With growing unease, I noticed people and things that had not registered with me the night before and realized I had been so preoccupied with capturing the occasion on my phone that I had essentially missed the whole thing. I never learned the name of the woman beside me at the reception. I could not recall the wedding cake flavor. I never introduced myself to my friend’s grandfather from Edmonton. I was so mortified that before checking into my flight, I turned my phone off and stuffed it into my carry-on.

The Stanford version of his essay is more compact. In truth, it’s more succinctly written and more satisfying because it is to the point. By stripping away all but the most critical pieces of his narrative, the candidate focuses his essay entirely on his central point: the battle of man versus technology.

Even if you’re not applying to business school, the essays are entertaining and fun to read. Sure, precious few are New Yorker worthy. In fact, many are fairly straightforward tales, simply told. What the successful essays clearly show is that there is no cookie-cutter formula or paint-by-the-numbers approach. Some start bluntly and straightforwardly, without a compelling or even interesting opening. Some meander through different themes. Some betray real personality and passion. Others are frankly boring. If a pattern of any kind could be discerned, it is how genuine the essays read.

The greatest benefit of reading them? For obsessive applicants to two of the very best business schools, they’ll take a lot of pressure off of you because they are quite imperfect.

GET YOUR COPY OF WHAT MATTERS? AND WHAT MORE? NOW

Questions about this article? Email us or leave a comment below.

- Stay Informed. Sign Up! Login Logout Search for:

Crafting A Compelling Career Vision For Your MBA Application

Advice Column: Insider Tips For Your MBA Applications

What Harvard Business School Really Wants: How To Ace The HBS Essay

How To Ace The INSEAD Video Questions

- How To Use Poets&Quants MBA Admissions Consultant Directory

- How To Select An MBA Admissions Consultant

- MBA Admission Consulting Claims: How Credible?

- Suddenly Cozy: MBA Consultants and B-Schools

- The Cost: $6,850 Result: B-School

Our Partner Sites: Poets&Quants for Execs | Poets&Quants for Undergrads | Tipping the Scales | We See Genius

- Fotgot Password?

The informative site for education and college admission.

10 Successful Harvard Application Essays And Reviews

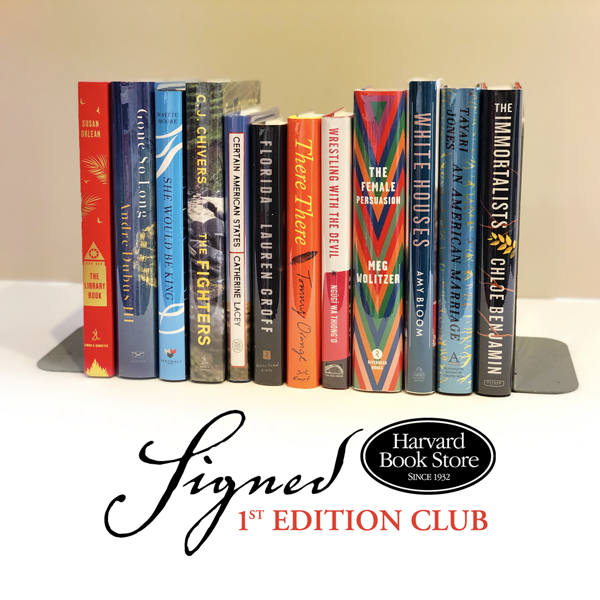

We are excited to announce our sponsorship with The Harvard Crimson, one of the premier student newspapers in the nation, for their annual release of "10 Successful Harvard Application Essays," a must-read for aspiring students. This collection showcases stellar essays and offers detailed reviews that reveal what makes these essays stand out to admission committees.

Reading these essays is an excellent way to familiarize yourself with the qualities and writing styles that Harvard and other top colleges value. Each essay is a testament to the unique voices and compelling stories that resonate with admissions officers.

https://www.thecrimson.com/topic/sponsored-successful-harvard-essays-2024/

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

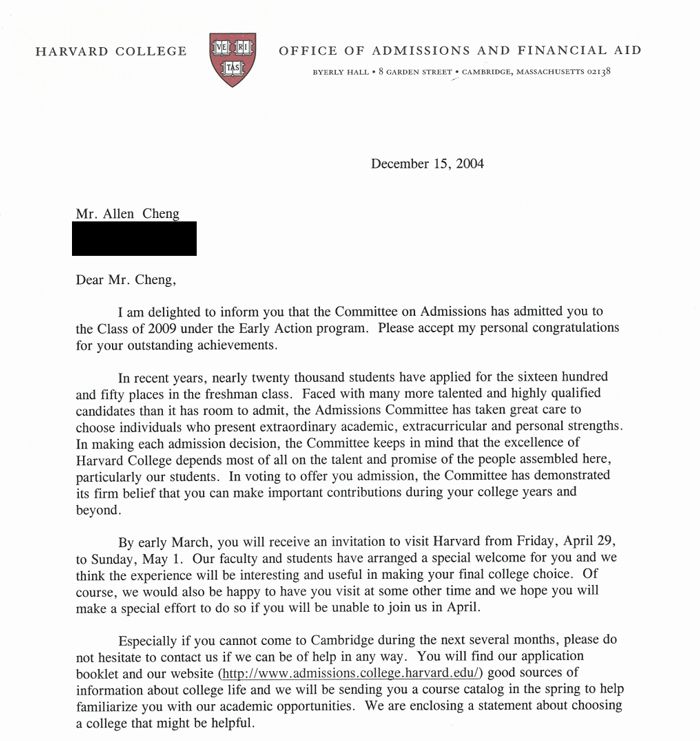

My Successful Harvard Application (Complete Common App + Supplement)

Other High School , College Admissions , Letters of Recommendation , Extracurriculars , College Essays

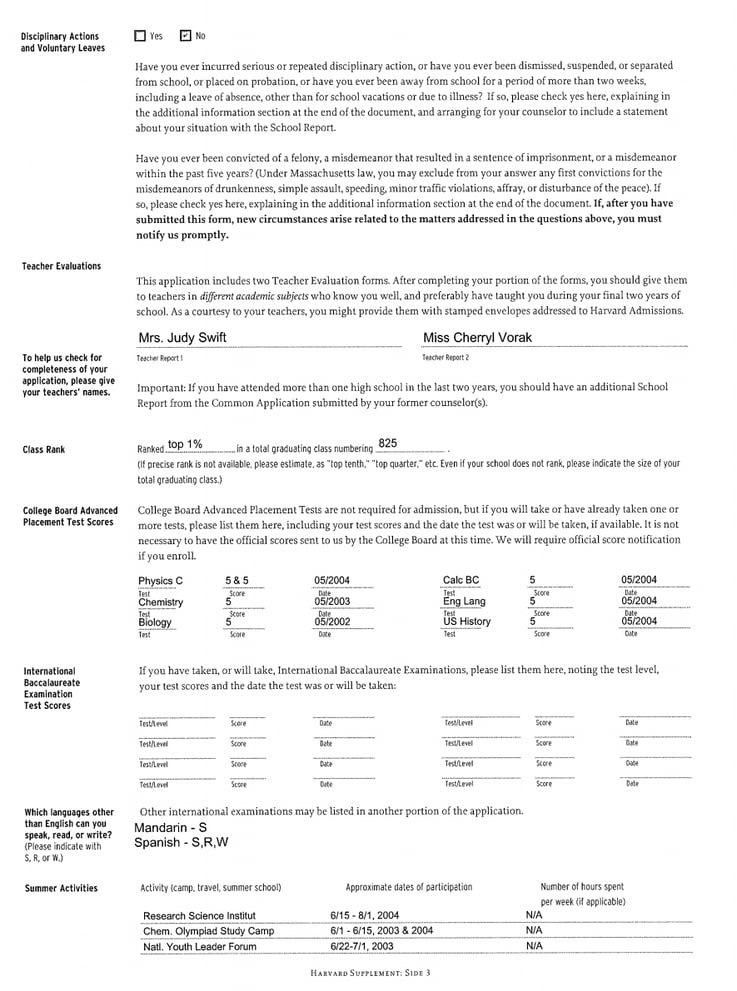

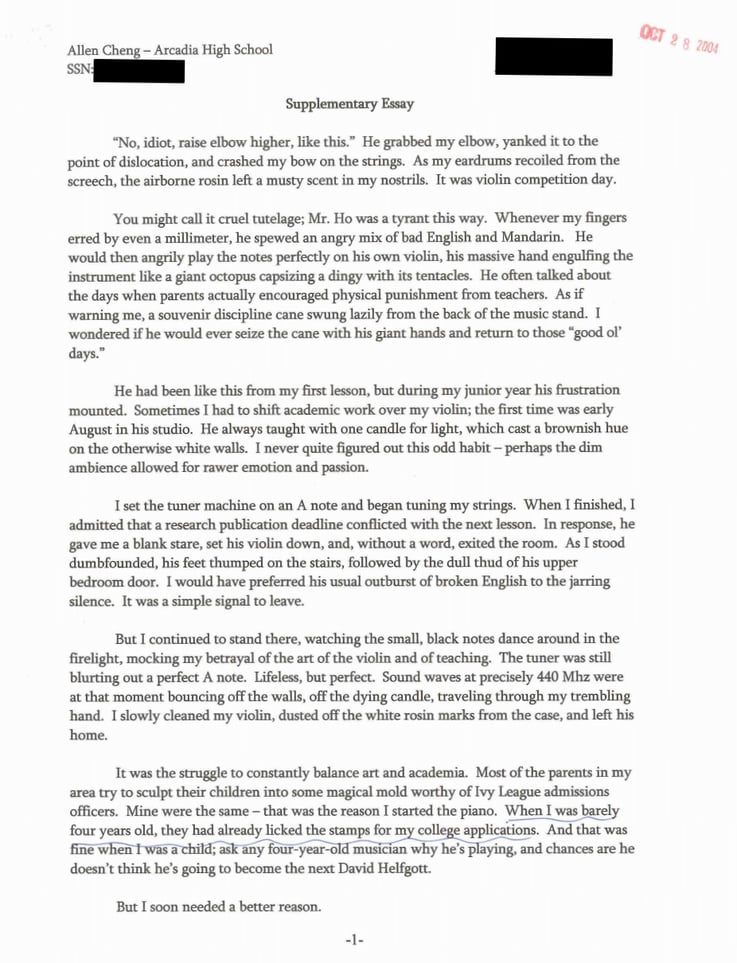

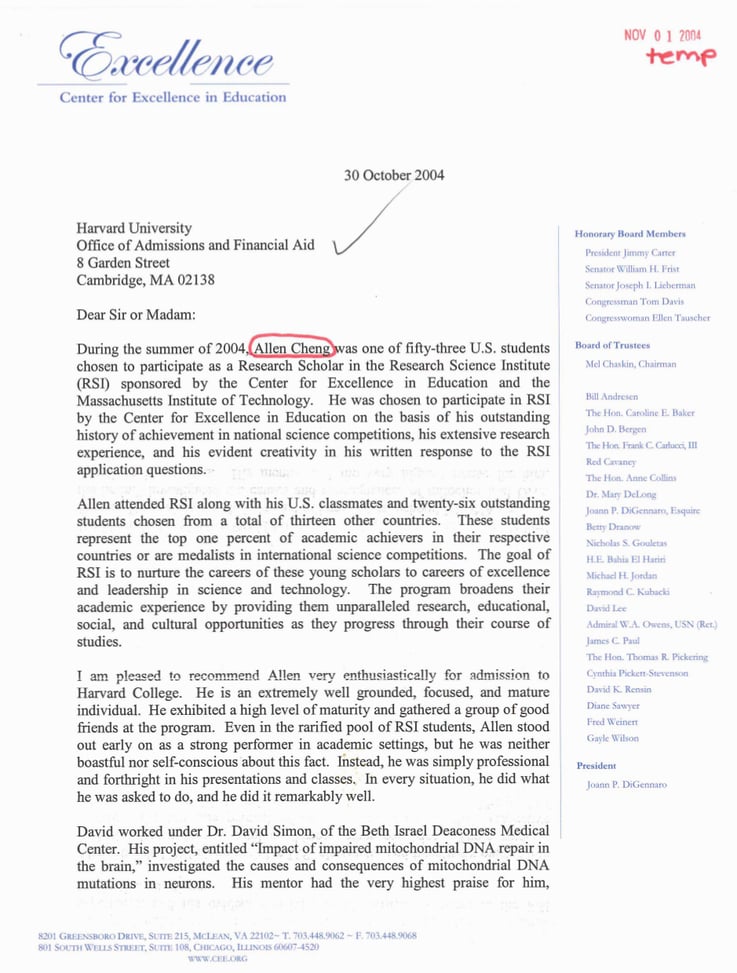

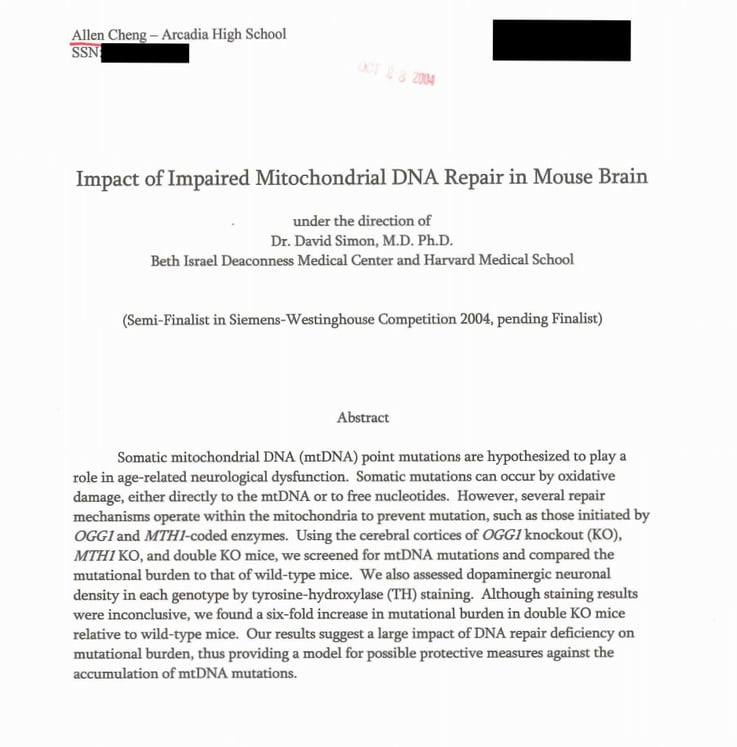

In 2005, I applied to college and got into every school I applied to, including Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. I decided to attend Harvard.

In this guide, I'll show you the entire college application that got me into Harvard—page by page, word for word .

In my complete analysis, I'll take you through my Common Application, Harvard supplemental application, personal statements and essays, extracurricular activities, teachers' letters of recommendation, counselor recommendation, complete high school transcript, and more. I'll also give you in-depth commentary on every part of my application.

To my knowledge, a college application analysis like this has never been done before . This is the application guide I wished I had when I was in high school.

If you're applying to top schools like the Ivy Leagues, you'll see firsthand what a successful application to Harvard and Princeton looks like. You'll learn the strategies I used to build a compelling application. You'll see what items were critical in getting me admitted, and what didn't end up helping much at all.

Reading this guide from beginning to end will be well worth your time—you might completely change your college application strategy as a result.

First Things First

Here's the letter offering me admission into Harvard College under Early Action.

I was so thrilled when I got this letter. It validated many years of hard work, and I was excited to take my next step into college (...and work even harder).

I received similar successful letters from every college I applied to: Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. (After getting into Harvard early, I decided not to apply to Yale, Columbia, UChicago, UPenn, and other Ivy League-level schools, since I already knew I would rather go to Harvard.)

The application that got me admitted everywhere is the subject of this guide. You're going to see everything that the admissions officers saw.

If you're hoping to see an acceptance letter like this in your academic future, I highly recommend you read this entire article. I'll start first with an introduction to this guide and important disclaimers. Then I'll share the #1 question you need to be thinking about as you construct your application. Finally, we'll spend a lot of time going through every page of my college application, both the Common App and the Harvard Supplemental App.

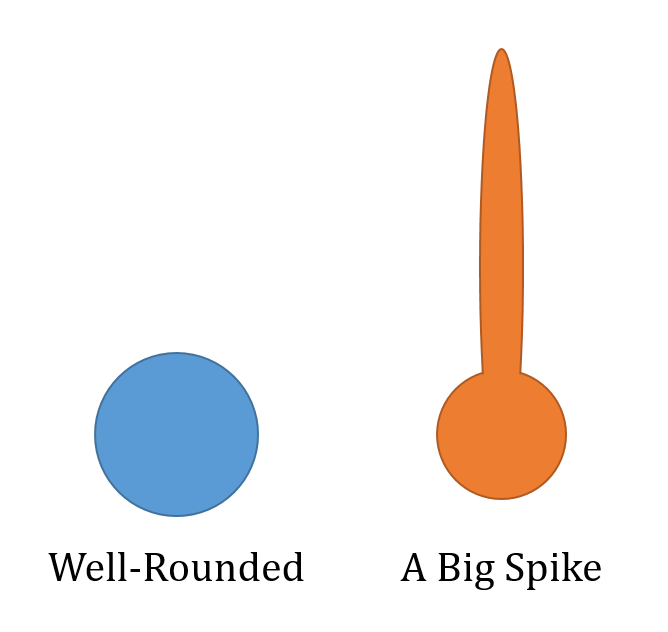

Important Note: the foundational principles of my application are explored in detail in my How to Get Into Harvard guide . In this popular guide, I explain:

- what top schools like the Ivy League are looking for

- how to be truly distinctive among thousands of applicants

- why being well-rounded is the kiss of death

If you have the time and are committed to maximizing your college application success, I recommend you read through my Harvard guide first, then come back to this one.

You might also be interested in my other two major guides:

- How to Get a Perfect SAT Score / Perfect ACT Score

- How to Get a 4.0 GPA

What's in This Harvard Application Guide?

From my student records, I was able to retrieve the COMPLETE original application I submitted to Harvard. Page by page, word for word, you'll see everything exactly as I presented it : extracurricular activities, awards and honors, personal statements and essays, and more.

In addition to all this detail, there are two special parts of this college application breakdown that I haven't seen anywhere else :

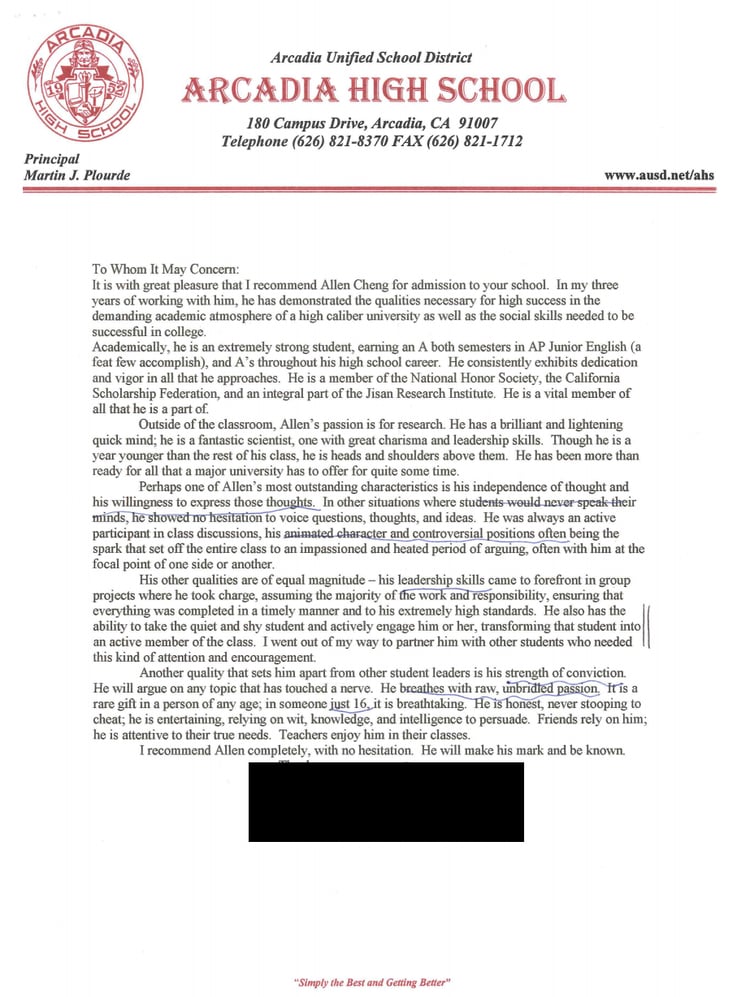

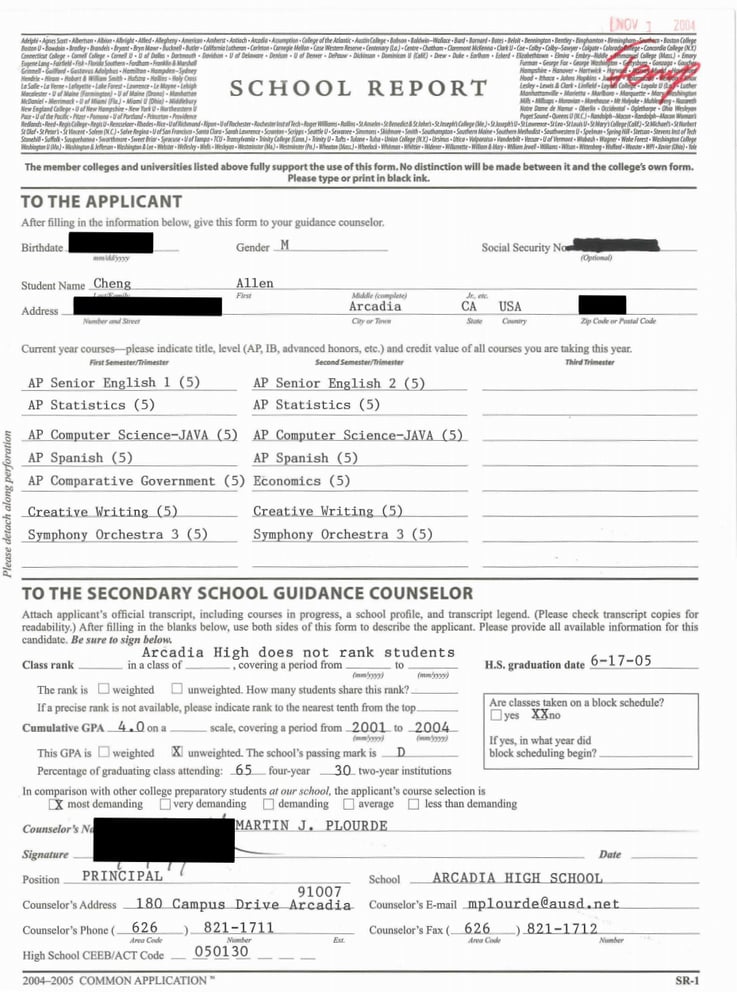

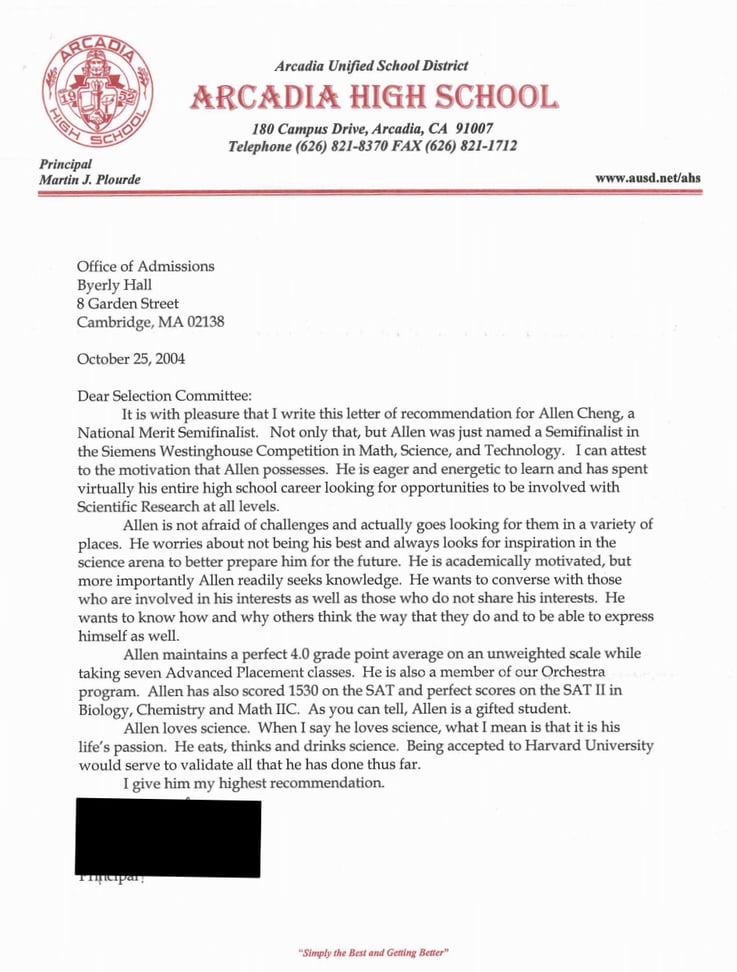

- You'll see my FULL recommendation letters and evaluation forms. This includes recommendations from two teachers, one principal, and supplementary writers. Normally you don't get to see these letters because you waive access to them when applying. You'll see how effective strong teacher advocates will be to your college application, and why it's so important to build strong relationships with your letter writers .

- You'll see the exact pen marks made by my Harvard admissions reader on my application . Members of admissions committees consider thousands of applications every year, which means they highlight the pieces of each application they find noteworthy. You'll see what the admissions officer considered important—and what she didn't.

For every piece of my application, I'll provide commentary on what made it so effective and my strategies behind creating it. You'll learn what it takes to build a compelling overall application.

Importantly, even though my application was strong, it wasn't perfect. I'll point out mistakes I made that I could have corrected to build an even stronger application.

Here's a complete table of contents for what we'll be covering. Each link goes directly to that section, although I'd recommend you read this from beginning to end on your first go.

Common Application

Personal Data

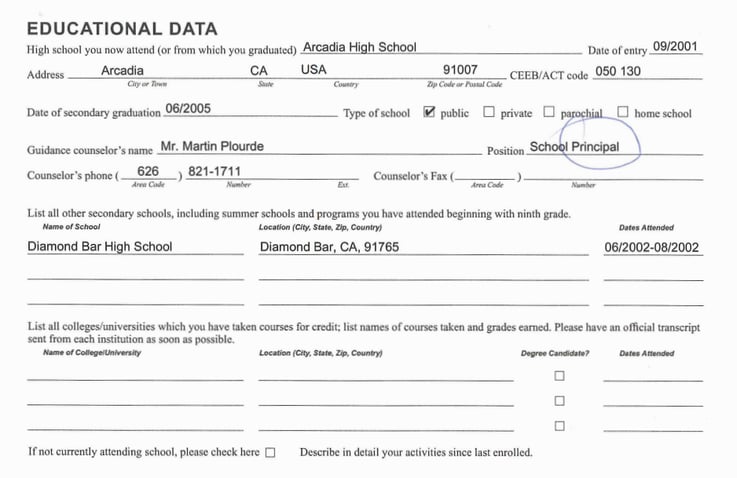

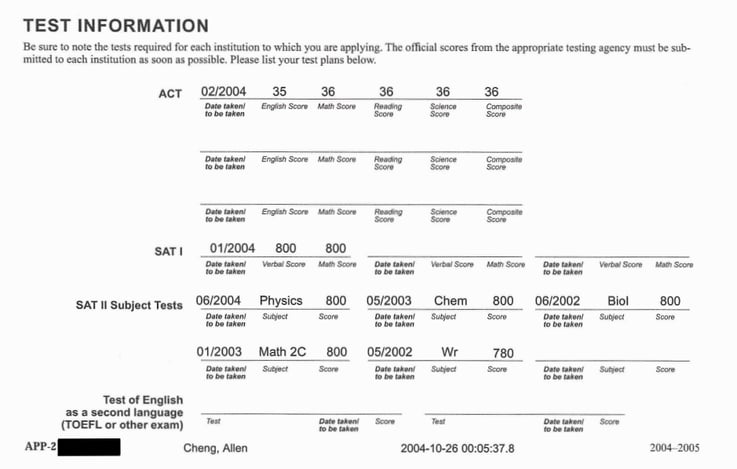

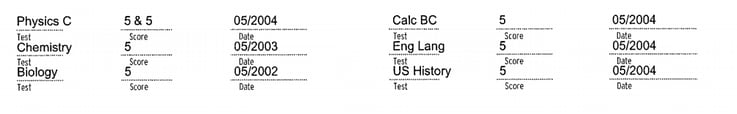

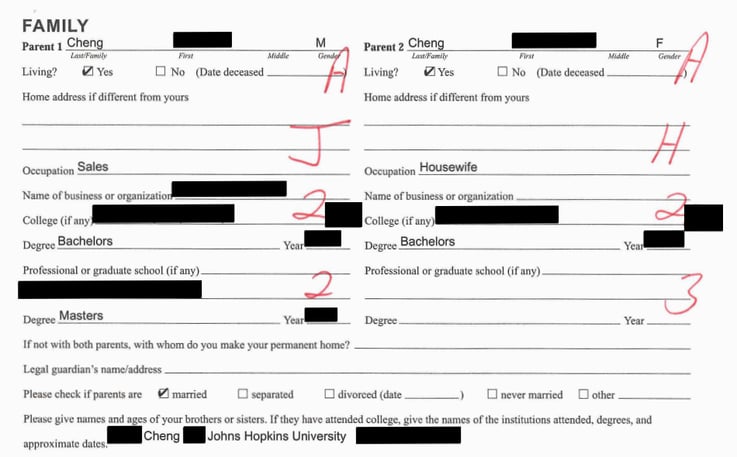

Educational data, test information.

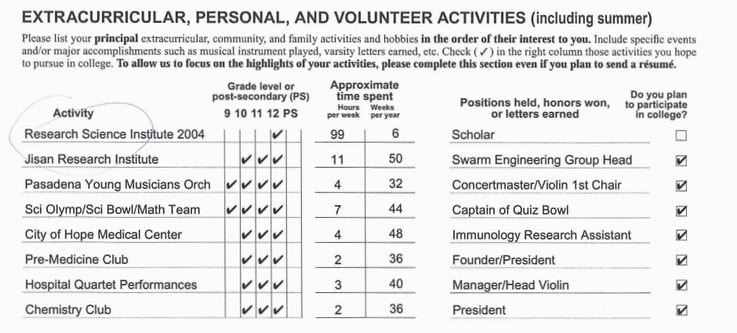

- Activities: Extracurricular, Personal, Volunteer

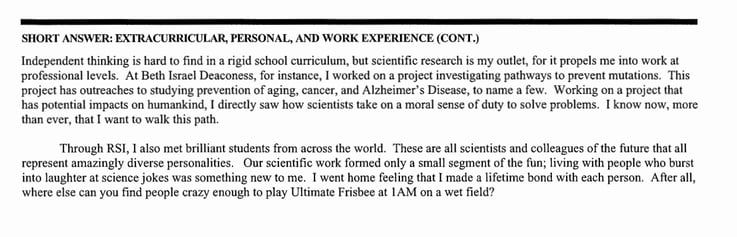

- Short Answer

- Additional Information

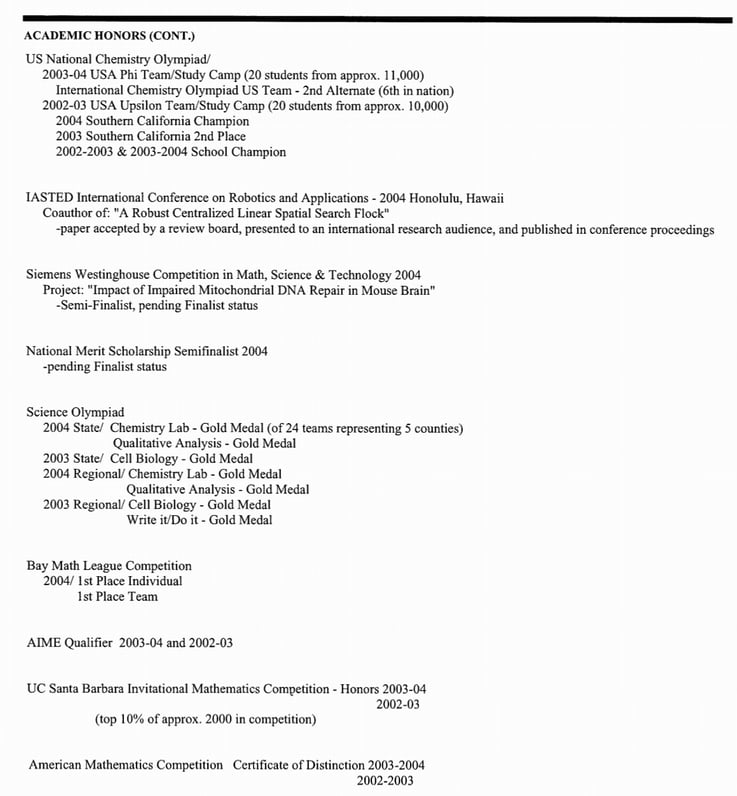

Academic Honors

Personal statement, teacher and counselor recommendations.

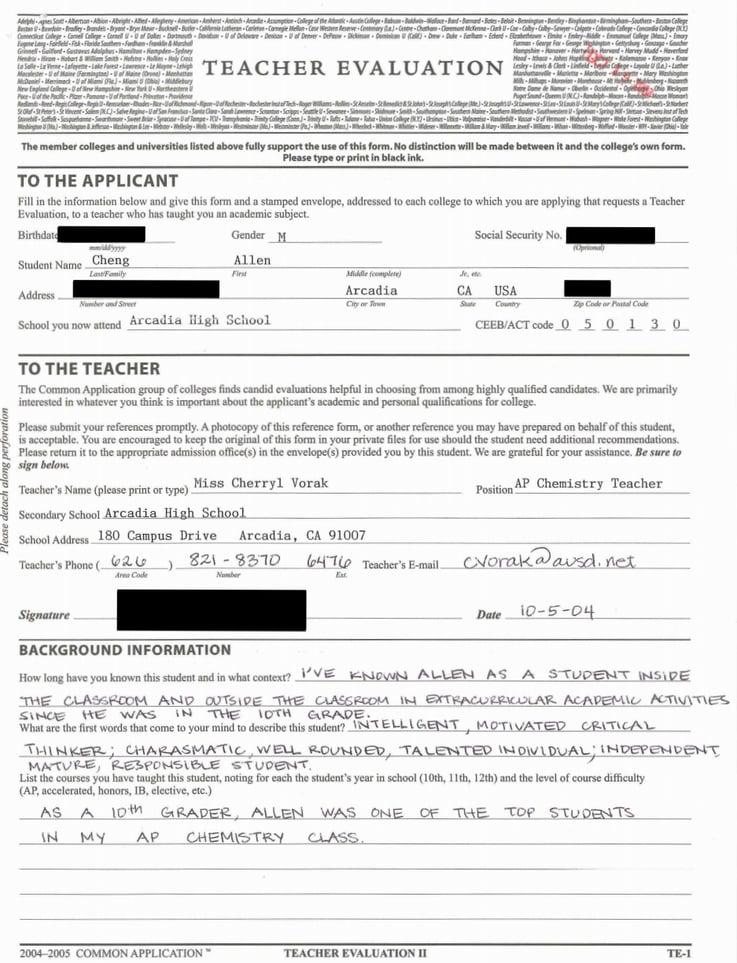

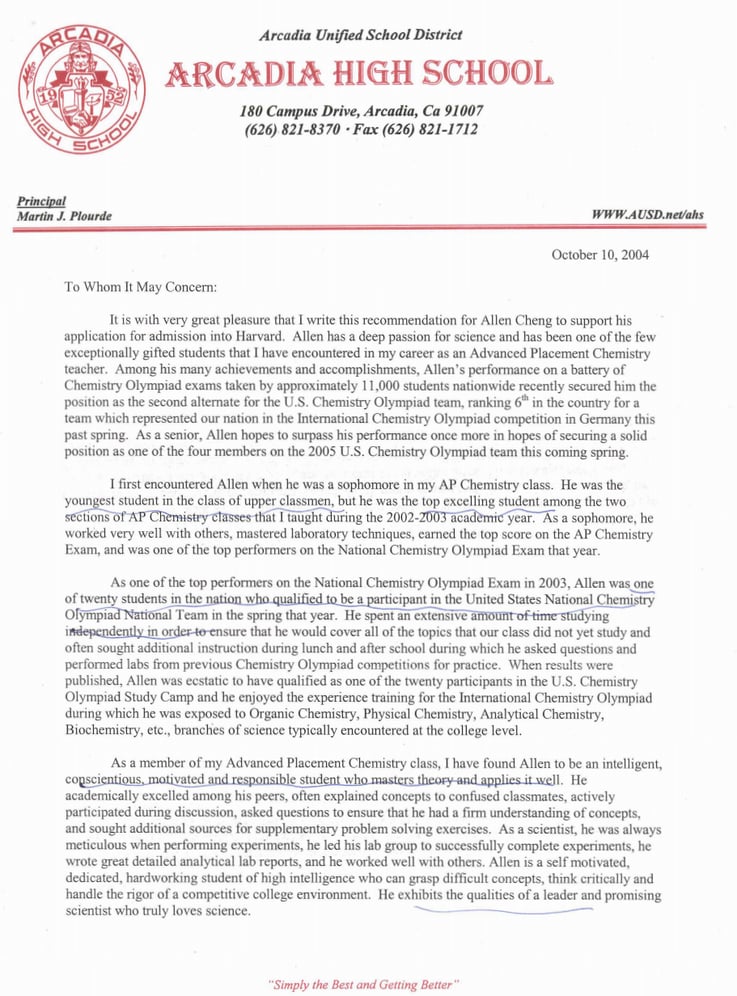

- Teacher Letter #1: AP Chemistry

- Teacher Letter #2: AP English Lang

School Report

- Principal Recommendation

Harvard Application Supplement

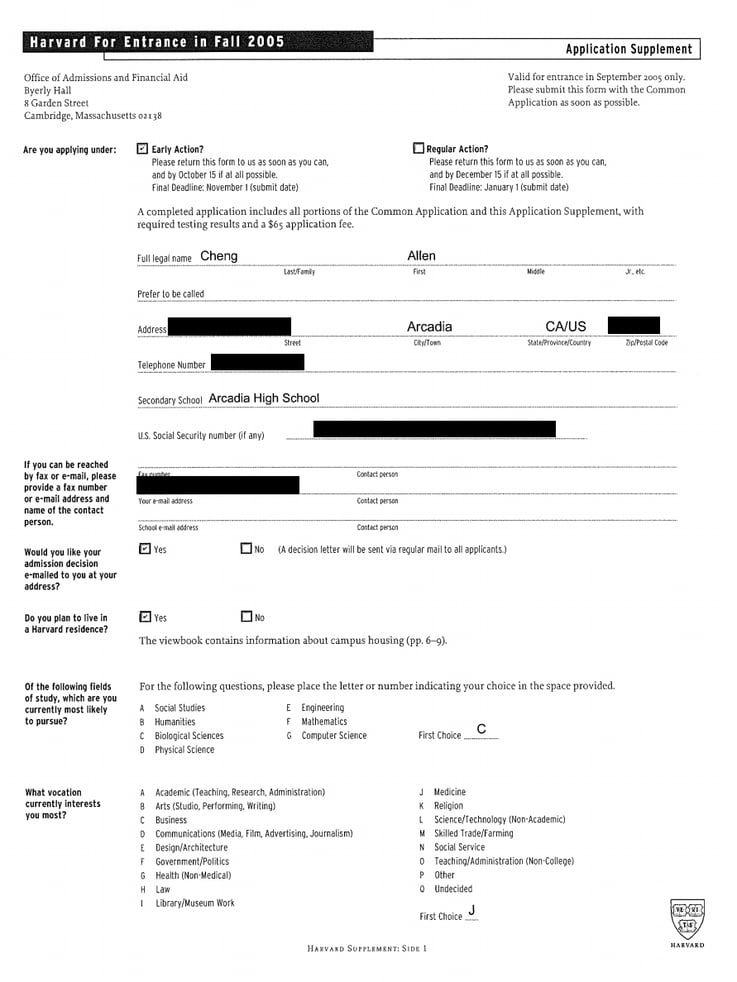

- Supplement Form

- Writing Supplement Essay

Supplementary Recommendation #1