The Complete Guide to UX Research Methods

UX research provides invaluable insight into product users and what they need and value. Not only will research reduce the risk of a miscalculated guess, it will uncover new opportunities for innovation.

By Miklos Philips

Miklos is a UX designer, product design strategist, author, and speaker with more than 18 years of experience in the design field.

PREVIOUSLY AT

“Empathy is at the heart of design. Without the understanding of what others see, feel, and experience, design is a pointless task.” —Tim Brown, CEO of the innovation and design firm IDEO

User experience (UX) design is the process of designing products that are useful, easy to use, and a pleasure to engage. It’s about enhancing the entire experience people have while interacting with a product and making sure they find value, satisfaction, and delight. If a mountain peak represents that goal, employing various types of UX research is the path UX designers use to get to the top of the mountain.

User experience research is one of the most misunderstood yet critical steps in UX design. Sometimes treated as an afterthought or an unaffordable luxury, UX research, and user testing should inform every design decision.

Every product, service, or user interface designers create in the safety and comfort of their workplaces has to survive and prosper in the real world. Countless people will engage our creations in an unpredictable environment over which designers have no control. UX research is the key to grounding ideas in reality and improving the odds of success, but research can be a scary word. It may sound like money we don’t have, time we can’t spare, and expertise we have to seek.

In order to do UX research effectively—to get a clear picture of what users think and why they do what they do—e.g., to “walk a mile in the user’s shoes” as a favorite UX maxim goes, it is essential that user experience designers and product teams conduct user research often and regularly. Contingent upon time, resources, and budget, the deeper they can dive the better.

What Is UX Research?

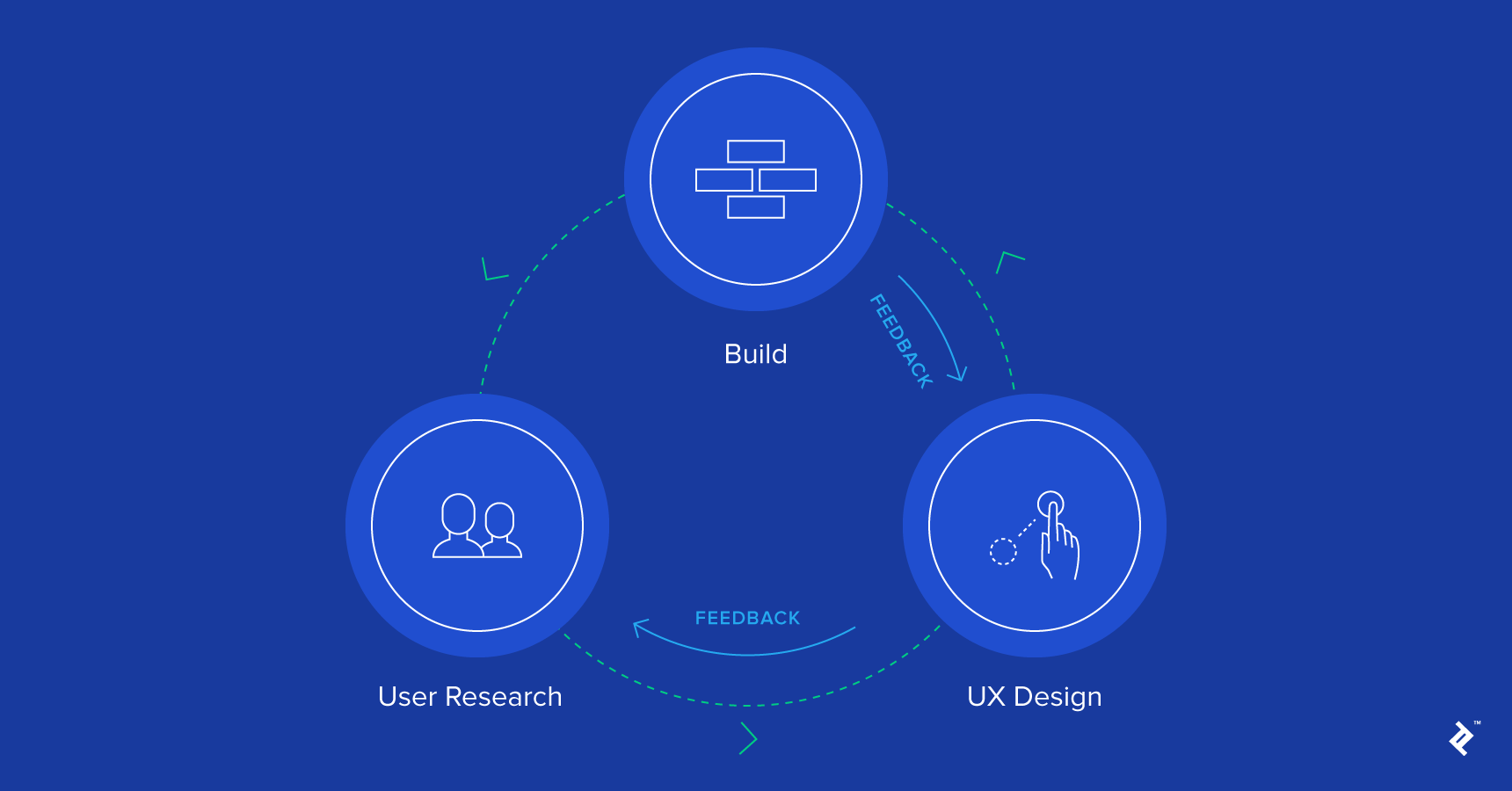

There is a long, comprehensive list of UX design research methods employed by user researchers , but at its center is the user and how they think and behave —their needs and motivations. Typically, UX research does this through observation techniques, task analysis, and other feedback methodologies.

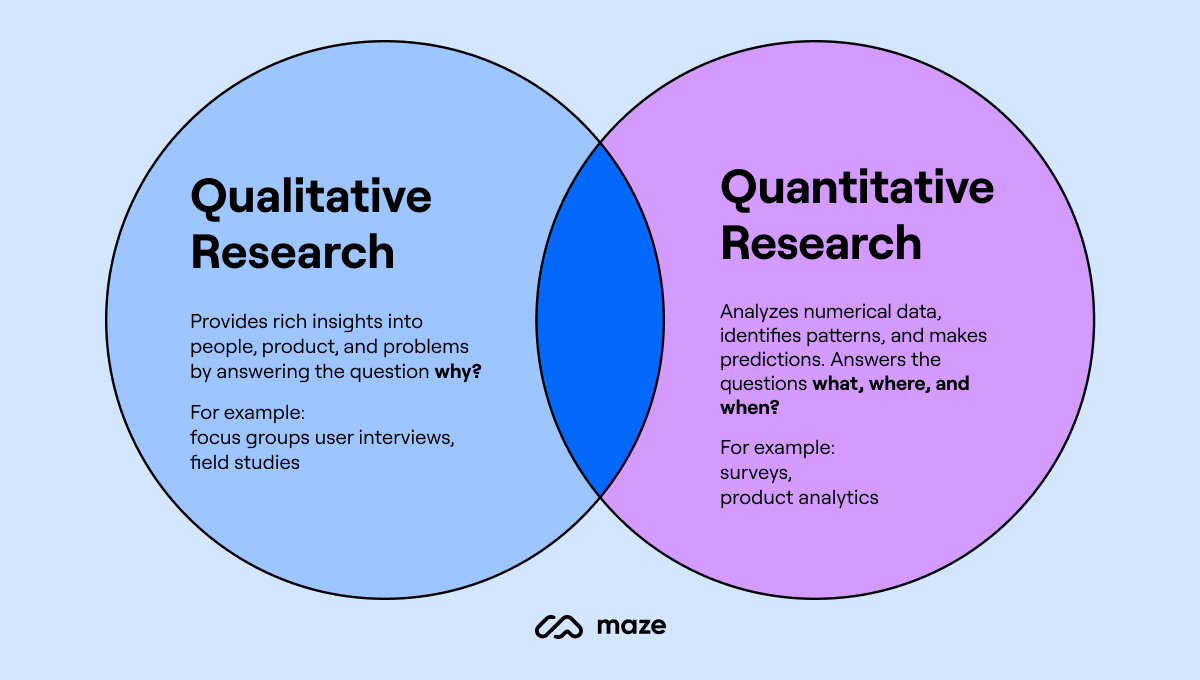

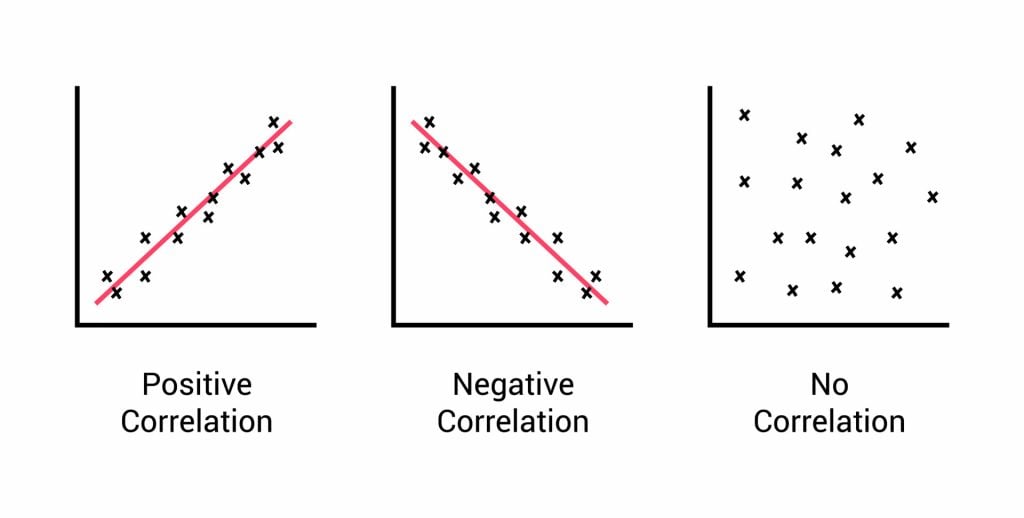

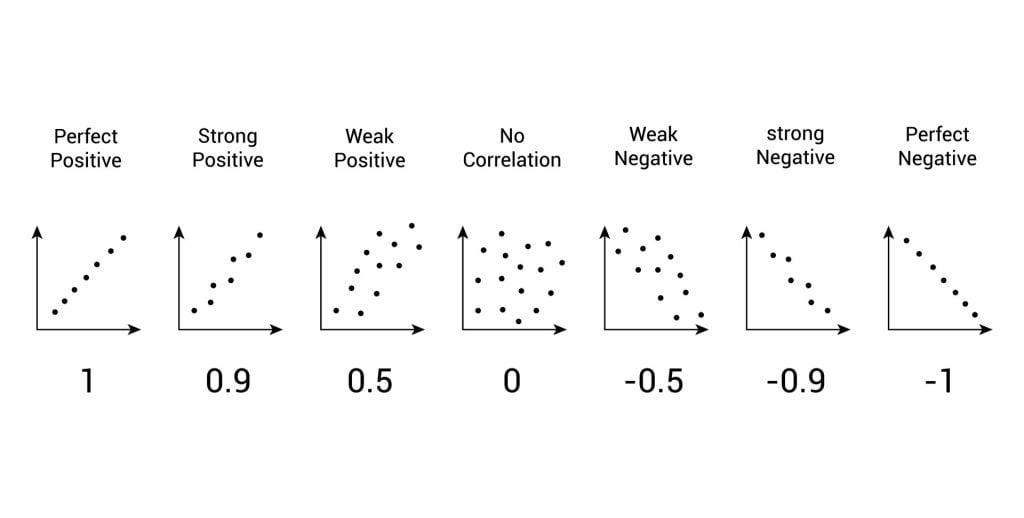

There are two main types of user research: quantitative (statistics: can be calculated and computed; focuses on numbers and mathematical calculations) and qualitative (insights: concerned with descriptions, which can be observed but cannot be computed).

Quantitative research is primarily exploratory research and is used to quantify the problem by way of generating numerical data or data that can be transformed into usable statistics. Some common data collection methods include various forms of surveys – online surveys , paper surveys , mobile surveys and kiosk surveys , longitudinal studies, website interceptors, online polls, and systematic observations.

This user research method may also include analytics, such as Google Analytics .

Google Analytics is part of a suite of interconnected tools that help interpret data on your site’s visitors including Data Studio , a powerful data-visualization tool, and Google Optimize, for running and analyzing dynamic A/B testing.

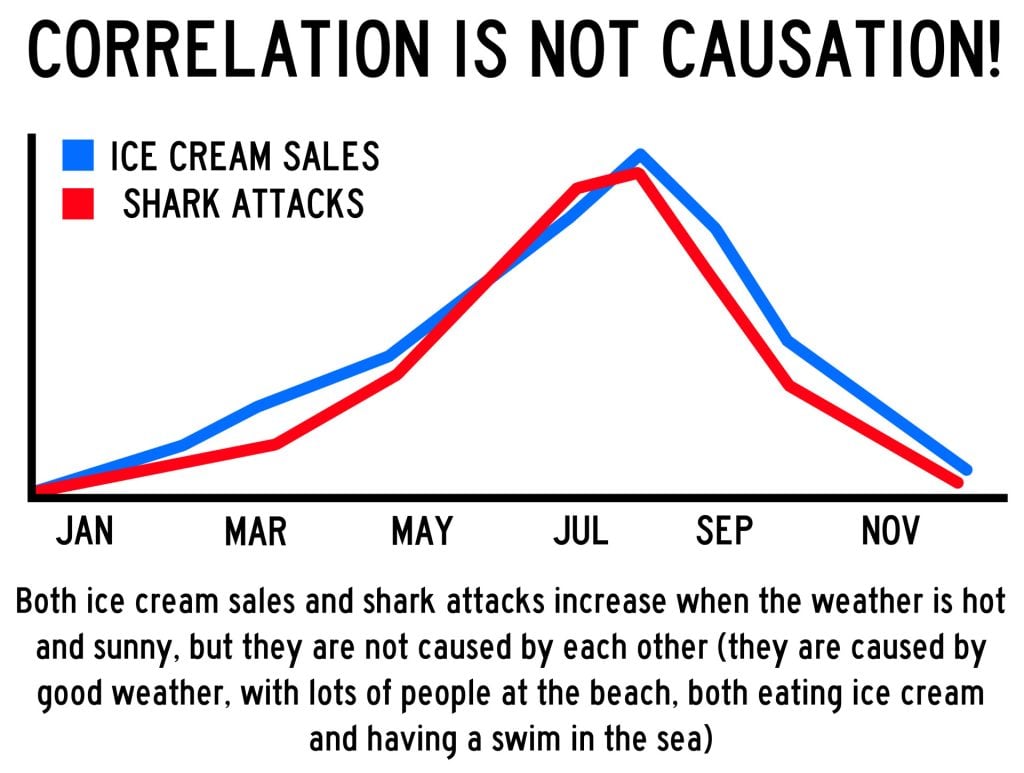

Quantitative data from analytics platforms should ideally be balanced with qualitative insights gathered from other UX testing methods , such as focus groups or usability testing. The analytical data will show patterns that may be useful for deciding what assumptions to test further.

Qualitative user research is a direct assessment of behavior based on observation. It’s about understanding people’s beliefs and practices on their terms. It can involve several different methods including contextual observation, ethnographic studies, interviews, field studies, and moderated usability tests.

Jakob Nielsen of the Nielsen Norman Group feels that in the case of UX research, it is better to emphasize insights (qualitative research) and that although quant has some advantages, qualitative research breaks down complicated information so it’s easy to understand, and overall delivers better results more cost effectively—in other words, it is much cheaper to find and fix problems during the design phase before you start to build. Often the most important information is not quantifiable, and he goes on to suggest that “quantitative studies are often too narrow to be useful and are sometimes directly misleading.”

Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. William Bruce Cameron

Design research is not typical of traditional science with ethnography being its closest equivalent—effective usability is contextual and depends on a broad understanding of human behavior if it is going to work.

Nevertheless, the types of user research you can or should perform will depend on the type of site, system or app you are developing, your timeline, and your environment.

Top UX Research Methods and When to Use Them

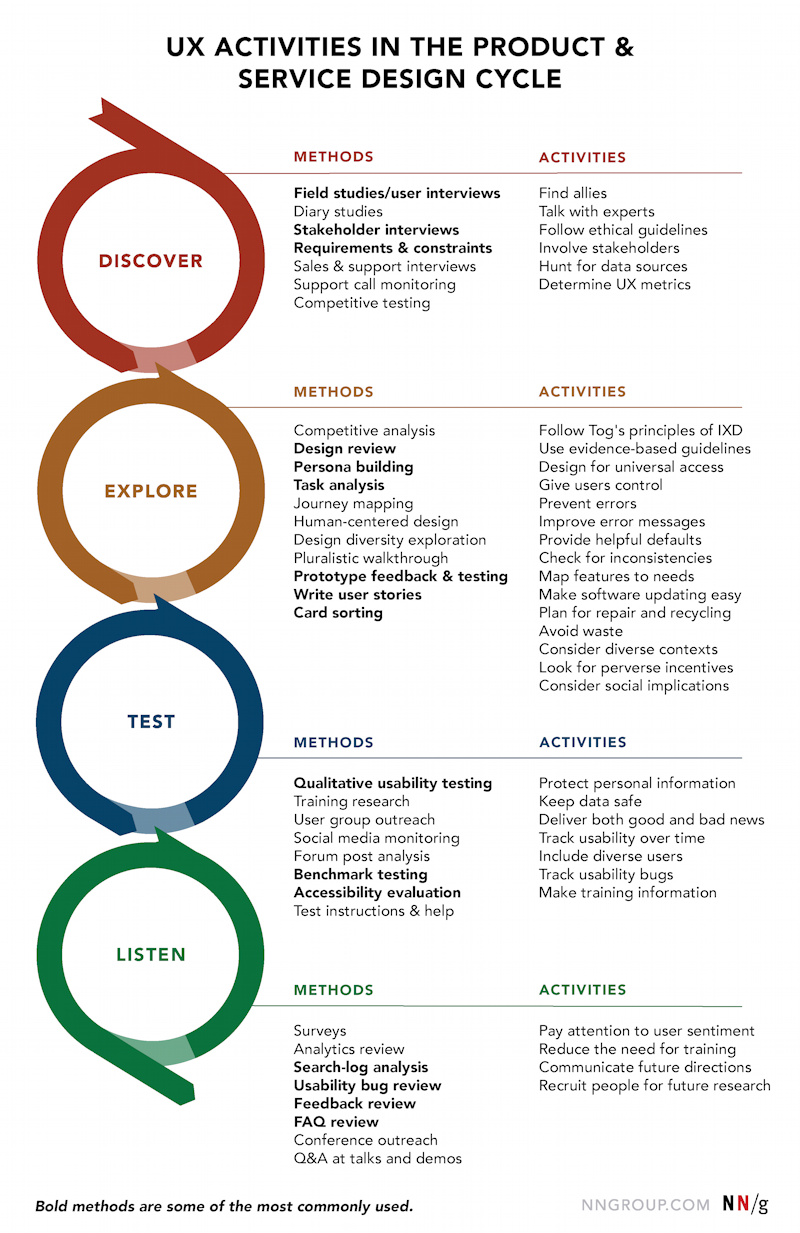

Here are some examples of the types of user research performed at each phase of a project.

Card Sorting : Allows users to group and sort a site’s information into a logical structure that will typically drive navigation and the site’s information architecture. This helps ensure that the site structure matches the way users think.

Contextual Interviews : Enables the observation of users in their natural environment, giving you a better understanding of the way users work.

First Click Testing : A testing method focused on navigation, which can be performed on a functioning website, a prototype, or a wireframe.

Focus Groups : Moderated discussion with a group of users, allowing insight into user attitudes, ideas, and desires.

Heuristic Evaluation/Expert Review : A group of usability experts evaluating a website against a list of established guidelines .

Interviews : One-on-one discussions with users show how a particular user works. They enable you to get detailed information about a user’s attitudes, desires, and experiences.

Parallel Design : A design methodology that involves several designers pursuing the same effort simultaneously but independently, with the intention to combine the best aspects of each for the ultimate solution.

Personas : The creation of a representative user based on available data and user interviews. Though the personal details of the persona may be fictional, the information used to create the user type is not.

Prototyping : Allows the design team to explore ideas before implementing them by creating a mock-up of the site. A prototype can range from a paper mock-up to interactive HTML pages.

Surveys : A series of questions asked to multiple users of your website that help you learn about the people who visit your site.

System Usability Scale (SUS) : SUS is a technology-independent ten-item scale for subjective evaluation of the usability.

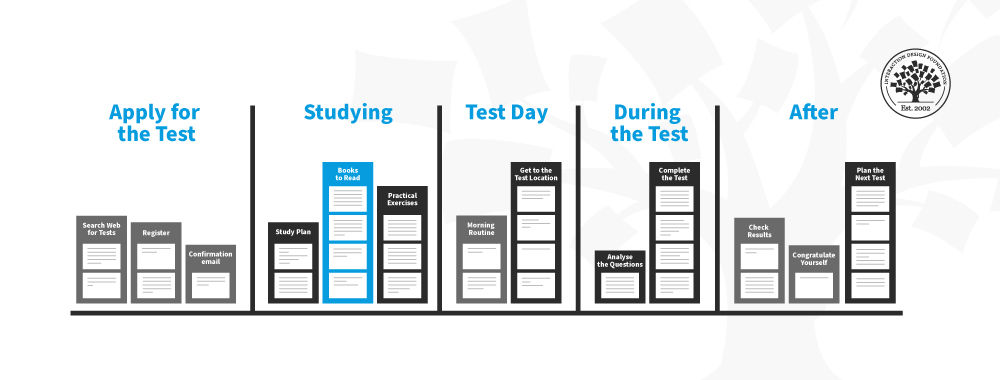

Task Analysis : Involves learning about user goals, including what users want to do on your website, and helps you understand the tasks that users will perform on your site.

Usability Testing : Identifies user frustrations and problems with a site through one-on-one sessions where a “real-life” user performs tasks on the site being studied.

Use Cases : Provide a description of how users use a particular feature of your website. They provide a detailed look at how users interact with the site, including the steps users take to accomplish each task.

You can do user research at all stages or whatever stage you are in currently. However, the Nielsen Norman Group advises that most of it be done during the earlier phases when it will have the biggest impact. They also suggest it’s a good idea to save some of your budget for additional research that may become necessary (or helpful) later in the project.

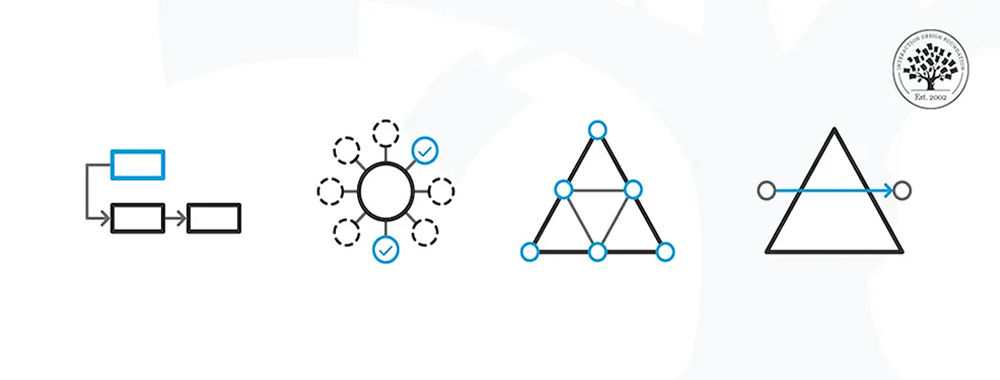

Here is a diagram listing recommended options that can be done as a project moves through the design stages. The process will vary, and may only include a few things on the list during each phase. The most frequently used methods are shown in bold.

Reasons for Doing UX Research

Here are three great reasons for doing user research :

To create a product that is truly relevant to users

- If you don’t have a clear understanding of your users and their mental models, you have no way of knowing whether your design will be relevant. A design that is not relevant to its target audience will never be a success.

To create a product that is easy and pleasurable to use

- A favorite quote from Steve Jobs: “ If the user is having a problem, it’s our problem .” If your user experience is not optimal, chances are that people will move on to another product.

To have the return on investment (ROI) of user experience design validated and be able to show:

- An improvement in performance and credibility

- Increased exposure and sales—growth in customer base

- A reduced burden on resources—more efficient work processes

Aside from the reasons mentioned above, doing user research gives insight into which features to prioritize, and in general, helps develop clarity around a project.

What Results Can I Expect from UX Research?

In the words of Mike Kuniaysky, user research is “ the process of understanding the impact of design on an audience. ”

User research has been essential to the success of behemoths like USAA and Amazon ; Joe Gebbia, CEO of Airbnb is an enthusiastic proponent, testifying that its implementation helped turn things around for the company when it was floundering as an early startup.

Some of the results generated through UX research confirm that improving the usability of a site or app will:

- Increase conversion rates

- Increase sign-ups

- Increase NPS (net promoter score)

- Increase customer satisfaction

- Increase purchase rates

- Boost loyalty to the brand

- Reduce customer service calls

Additionally, and aside from benefiting the overall user experience, the integration of UX research into the development process can:

- Minimize development time

- Reduce production costs

- Uncover valuable insights about your audience

- Give an in-depth view into users’ mental models, pain points, and goals

User research is at the core of every exceptional user experience. As the name suggests, UX is subjective—the experience that a person goes through while using a product. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the needs and goals of potential users, the context, and their tasks which are unique for each product. By selecting appropriate UX research methods and applying them rigorously, designers can shape a product’s design and can come up with products that serve both customers and businesses more effectively.

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- How to Conduct Effective UX Research: A Guide

- The Value of User Research

- UX Research Methods and the Path to User Empathy

- Design Talks: Research in Action with UX Researcher Caitria O'Neill

- Swipe Right: 3 Ways to Boost Safety in Dating App Design

- How to Avoid 5 Types of Cognitive Bias in User Research

Understanding the basics

How do you do user research in ux.

UX research includes two main types: quantitative (statistical data) and qualitative (insights that can be observed but not computed), done through observation techniques, task analysis, and other feedback methodologies. The UX research methods used depend on the type of site, system, or app being developed.

What are UX methods?

There is a long list of methods employed by user research, but at its center is the user and how they think, behave—their needs and motivations. Typically, UX research does this through observation techniques, task analysis, and other UX methodologies.

What is the best research methodology for user experience design?

The type of UX methodology depends on the type of site, system or app being developed, its timeline, and environment. There are 2 main types: quantitative (statistics) and qualitative (insights).

What does a UX researcher do?

A user researcher removes the need for false assumptions and guesswork by using observation techniques, task analysis, and other feedback methodologies to understand a user’s motivation, behavior, and needs.

Why is UX research important?

UX research will help create a product that is relevant to users and is easy and pleasurable to use while boosting a product’s ROI. Aside from these reasons, user research gives insight into which features to prioritize, and in general, helps develop clarity around a project.

- UserResearch

Miklos Philips

London, United Kingdom

Member since May 20, 2016

About the author

World-class articles, delivered weekly.

By entering your email, you are agreeing to our privacy policy .

Toptal Designers

- Adobe Creative Suite Experts

- Agile Designers

- AI Designers

- Art Direction Experts

- Augmented Reality Designers

- Axure Experts

- Brand Designers

- Creative Directors

- Dashboard Designers

- Digital Product Designers

- E-commerce Website Designers

- Full-Stack Designers

- Information Architecture Experts

- Interactive Designers

- Mobile App Designers

- Mockup Designers

- Presentation Designers

- Prototype Designers

- SaaS Designers

- Sketch Experts

- Squarespace Designers

- User Flow Designers

- User Research Designers

- Virtual Reality Designers

- Visual Designers

- Wireframing Experts

- View More Freelance Designers

Join the Toptal ® community.

Integrations

What's new?

Prototype Testing

Live Website Testing

Feedback Surveys

Interview Studies

Card Sorting

Tree Testing

In-Product Prompts

Participant Management

Automated Reports

Templates Gallery

Choose from our library of pre-built mazes to copy, customize, and share with your own users

Browse all templates

Financial Services

Tech & Software

Product Designers

Product Managers

User Researchers

By use case

Concept & Idea Validation

Wireframe & Usability Test

Content & Copy Testing

Feedback & Satisfaction

Content Hub

Educational resources for product, research and design teams

Explore all resources

Question Bank

Research Maturity Model

Guides & Reports

Help Center

Future of User Research Report

The Optimal Path Podcast

Maze Guides | Resources Hub

What is UX Research: The Ultimate Guide for UX Researchers

0% complete

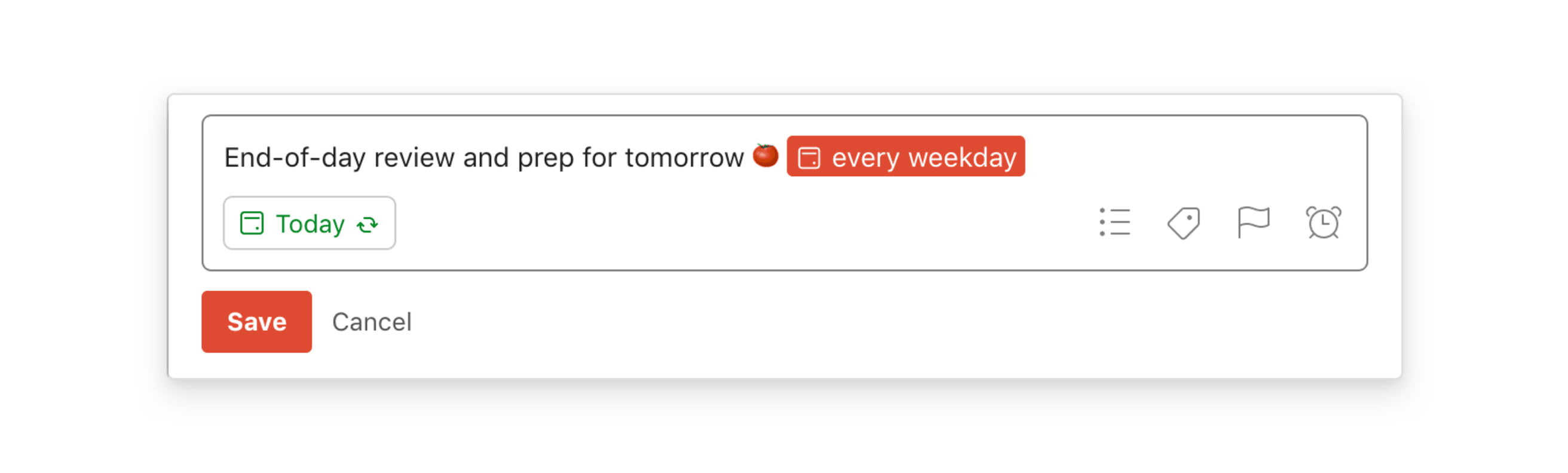

The UX researcher’s toolkit: 11 UX research methods and when to use them

After defining your objectives and planning your research framework, it’s time to choose the research technique that will best serve your project's goals and yield the right insights. While user research is often treated as an afterthought, it should inform every design decision. In this chapter, we walk you through the most common research methods and help you choose the right one for you.

What are UX research methods?

A UX research method is a way of generating insights about your users, their behavior, motivations, and needs.

These methods help:

- Learn about user behavior and attitudes

- Identify key pain points and challenges in the user interface

- Develop user personas to identify user needs and drive solutions

- Test user interface designs to see what works and what doesn’t

You can use research methodologies like user interviews, surveys, focus groups, card sorting, usability testing to identify user challenges and turn them into opportunities to improve the user experience.

More of a visual learner? Check out this video for a speedy rundown. If you’re ready to get stuck in, jump straight to our full breakdown .

The most common types of user research

First, let’s talk about the types of UX research. Every individual research method falls under these types, which reflect different goals and objectives for conducting research.

Here’s a quick overview:

Qualitative vs. quantitative

All research methods are either quantitative or qualitative . Qualitative research focuses on capturing subjective insights into users' experiences. It aims to understand the underlying reasons, motivations, and behaviors of individuals.

Quantitative research, on the other hand, involves collecting and analyzing numerical data to identify patterns, trends, and significance. It aims to quantify user behaviors, preferences, and attitudes, allowing for generalizations and statistical insights.

Qualitative research also typically involves a smaller sample size than quantitative research. Nielsen Norman Group recommends 40 participants—see our full rundown of how many user testers you need for different research methods .

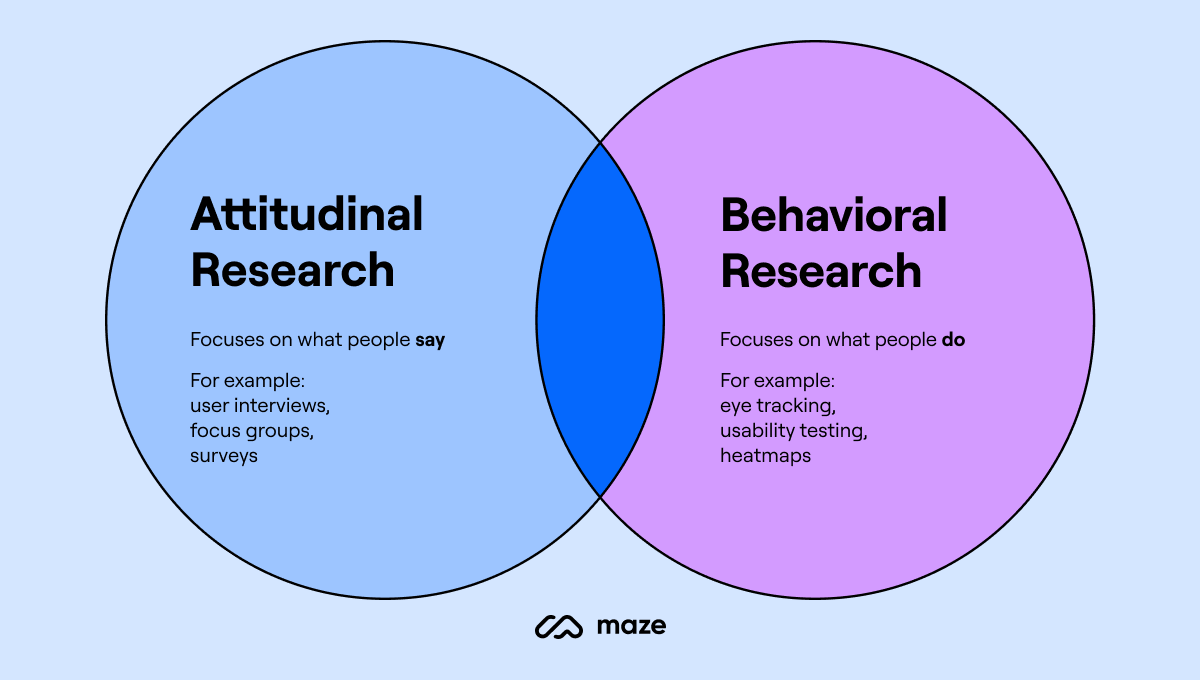

Attitudinal vs. behavioral

Attitudinal research is about understanding users' attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs. It delves into the 'why' behind user decisions and actions. It often involves surveys or interviews where users are asked about their feelings, preferences, or perceptions towards a product or service. It's subjective in nature, aiming to capture people's emotions and opinions.

Behavioral research is about what users do rather than what they say they do or would do. This kind of research is often based on observation methods like usability testing, eye-tracking, or heat maps to understand user behavior.

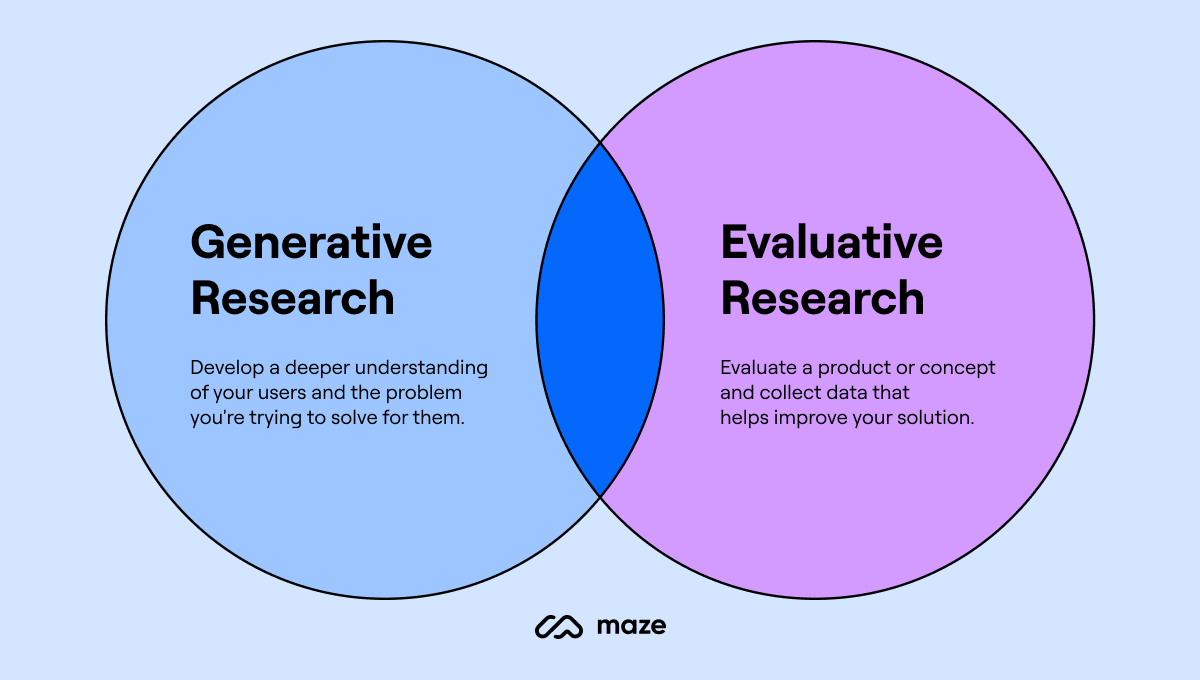

Generative vs. evaluative

Generative research is all about generating new ideas, concepts, and insights to fuel the design process. You might run brainstorming sessions with groups of users, card sorting, and co-design sessions to inspire creativity and guide the development of user-centered solutions.

On the other hand, evaluative research focuses on assessing the usability, effectiveness, and overall quality of existing designs or prototypes. Once you’ve developed a prototype of your product, it's time to evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. You can compare different versions of a product design or feature through A/B testing—ensuring your UX design meets user needs and expectations.

Remove the guesswork from product decisions

Collect both quantitative and qualitative insights from your customers and build truly user-centric products with Maze.

11 Best UX research methods and when to use them

There are various UX research techniques—each method serves a specific purpose and can provide unique insights into user behaviors and preferences. In this section, we’ll highlight the most common research techniques you need to know.

Read on for an at-a-glance table, and full breakdown of each method.

| User interviews | One-on-one open-ended and guided discussions | Start and end of your project | Qualitative Generative |

| Field studies | Observe people in their natural environment | All stages | Qualitative Behavioral |

| Focus group | Group discussions facilitated by a moderator | Start and end of your project | Qualitative Generative |

| Diary studies | Users keep a diary to track interactions and experience with a product | Start of your project | Qualitative Evaluative |

| Surveys | Asking people open or closed questions | All stages | Qualitative |

| Card sorting | Users sort information and ideas into groups that makes sense to them | Start of your project | Qualitative |

| Tree testing | Assess the findability and organization of information as users navigate a stripped-down IA | Start of your design or redesign process | Quantitative |

| Usability testing | Users perform a set of tasks in a controlled setting | All stages | Qualitative Behavioral |

| Five second testing | Collect immediate impressions within a short timeframe | During initial ideation and throughout design | Attitudinal Evaluative |

| A/B testing | Compare two versions of a solution | All stages | Quantitative |

| Concept testing | Evaluate the feasibility, appeal, and potential success of a new product | During initial ideation, design, and before launch | Qualitative |

1. User interviews

Tl;dr: user interviews.

Directly ask users about their experiences with a product to understand their thoughts, feelings, and problems

✅ Provides detailed insights that survey may miss ❌ May not represent the wider user base; depends on user’s memory and honesty

User interviews are a qualitative research method that involves having open-ended and guided discussions with users to gather in-depth insights about their experiences, needs, motivations, and behaviors.

Typically, you would ask a few questions on a specific topic during a user interview and analyze participants' answers. The results you get will depend on how well you form and ask questions, as well as follow up on participants’ answers.

“As a researcher, it's our responsibility to drive the user to their actual problems,” says Yuliya Martinavichene , User Experience Researcher at Zinio. She adds, “The narration of incidents can help you analyze a lot of hidden details with regard to user behavior.”

That’s why you should:

- Start with a wide context : Make sure that your questions don’t start with your product

- Ask questions: Always ask questions that focus on the tasks that users are trying to complete

- Invest in analysis : Get transcripts done and share the findings with your team

Tanya Nativ , Design Researcher at Sketch recommends defining the goals and assumptions internally. “Our beliefs about our users’ behavior really help to structure good questions and get to the root of the problem and its solution,” she explains.

It's easy to be misunderstood if you don't have experience writing interview questions. You can get someone to review them for you or use our Question Bank of 350+ research questions .

When to conduct user interviews

This method is typically used at the start and end of your project. At the start of a project, you can establish a strong understanding of your target users, their perspectives, and the context in which they’ll interact with your product. By the end of your project, new user interviews—often with a different set of individuals—offer a litmus test for your product's usability and appeal, providing firsthand accounts of experiences, perceived strengths, and potential areas for refinement.

2. Field studies

Tl;dr: field studies.

Observe users in their natural environment to inform design decisions with real-world context

✅ Provides contextual insights into user behavior in real-world situations ✅ Helps identify external factors and conditions that influence user experience ❌ Can be time-consuming and resource-intensive to conduct ❌ Participants may behave differently when they know they are being observed (Hawthorne effect)

Field studies—also known as ethnographic research—are research activities that take place in the user’s environment rather than in your lab or office. They’re a great method for uncovering context, unknown motivations, or constraints that affect the user experience.

An advantage of field studies is observing people in their natural environment, giving you a glimpse at the context in which your product is used. It’s useful to understand the context in which users complete tasks, learn about their needs, and collect in-depth user stories.

When to conduct field studies

This method can be used at all stages of your project—two key times you may want to conduct field studies are:

- As part of the discovery and exploration stage to define direction and understand the context around when and how users interact with the product

- During usability testing, once you have a prototype, to evaluate the effectiveness of the solution or validate design assumptions in real-world contexts

3. Focus groups

Tl;dr: focus groups.

Gather qualitative data from a group of users discussing their experiences and opinions about a product

✅ Allows for diverse perspectives to be shared and discussed ❌ Group dynamics may influence individual opinions

A focus group is a qualitative research method that includes the study of a group of people, their beliefs, and opinions. It’s typically used for market research or gathering feedback on products and messaging.

Focus groups can help you better grasp:

- How users perceive your product

- What users believe are a product’s most important features

- What problems do users experience with the product

As with any qualitative research method, the quality of the data collected through focus groups is only as robust as the preparation. So, it’s important to prepare a UX research plan you can refer to during the discussion.

Here’s some things to consider:

- Write a script to guide the conversation

- Ask clear, open-ended questions focused on the topics you’re trying to learn about

- Include around five to ten participants to keep the sessions focused and organized

When to conduct focus groups

It’s easier to use this research technique when you're still formulating your concept, product, or service—to explore user preferences, gather initial reactions, and generate ideas. This is because, in the early stages, you have flexibility and can make significant changes without incurring high costs.

Another way some researchers employ focus groups is post-launch to gather feedback and identify potential improvements. However, you can also use other methods here which may be more effective for identifying usability issues. For example, a platform like Maze can provide detailed, actionable data about how users interact with your product. These quantitative results are a great accompaniment to the qualitative data gathered from your focus group.

4. Diary studies

Tl;dr: diary studies.

Get deep insights into user thoughts and feelings by having them keep a product-related diary over a set period of time, typically a couple of weeks

✅ Gives you a peak into how users interact with your product in their day-to-day ❌ Depends on how motivated and dedicated the users are

Diary studies involve asking users to track their usage and thoughts on your product by keeping logs or diaries, taking photos, explaining their activities, and highlighting things that stood out to them.

“Diary studies are one of the few ways you can get a peek into how users interact with our product in a real-world scenario,” says Tanya.

A diary study helps you tell the story of how products and services fit into people’s daily lives, and the touch-points and channels they choose to complete their tasks.

There’s several key questions to consider before conducting diary research, from what kind of diary you want—freeform or structured, and digital or paper—to how often you want participants to log their thoughts.

- Open, ‘freeform’ diary: Users have more freedom to record what and when they like, but can also lead to missed opportunities to capture data users might overlook

- Closed, ‘structured; diary: Users follow a stricter entry-logging process and answer pre-set questions

Remember to determine the trigger: a signal that lets the participants know when they should log their feedback. Tanya breaks these triggers down into the following:

- Interval-contingent trigger : Participants fill out the diary at specific intervals such as one entry per day, or one entry per week

- Signal-contingent trigger : You tell the participant when to make an entry and how you would prefer them to communicate it to you as well as your preferred type of communication

- Event-contingent trigger : The participant makes an entry whenever a defined event occurs

When to conduct diary studies

Diary studies are often valuable when you need to deeply understand users' behaviors, routines, and pain points in real-life contexts. This could be when you're:

- Conceptualizing a new product or feature: Gain insights into user habits, needs, and frustrations to inspire your design

- Trying to enhance an existing product: Identify areas where users are having difficulties or where there are opportunities for better user engagement

TL;DR: Surveys

Collect quantitative data from a large sample of users about their experiences, preferences, and satisfaction with a product

✅ Provides a broad overview of user opinions and trends ❌ May lack in-depth insights and context behind user responses

Although surveys are primarily used for quantitative research, they can also provided qualitative data, depending on whether you use closed or open-ended questions:

- Closed-ended questions come with a predefined set of answers to choose from using formats like rating scales, rankings, or multiple choice. This results in quantitative data.

- Open-ended question s are typically open-text questions where test participants give their responses in a free-form style. This results in qualitative data.

Matthieu Dixte , Product Researcher at Maze, explains the benefit of surveys: “With open-ended questions, researchers get insight into respondents' opinions, experiences, and explanations in their own words. This helps explore nuances that quantitative data alone may not capture.”

So, how do you make sure you’re asking the right survey questions? Gregg Bernstein , UX Researcher at Signal, says that when planning online surveys, it’s best to avoid questions that begin with “How likely are you to…?” Instead, Gregg says asking questions that start with “Have you ever… ?” will prompt users to give more specific and measurable answers.

Make sure your questions:

- Are easy to understand

- Don't guide participants towards a particular answer

- Include both closed-ended and open-ended questions

- Respect users and their privacy

- Are consistent in terms of format

To learn more about survey design, check out this guide .

When to conduct surveys

While surveys can be used at all stages of project development, and are ideal for continuous product discovery , the specific timing and purpose may vary depending on the research goals. For example, you can run surveys at:

- Conceptualization phase to gather preliminary data, and identify patterns, trends, or potential user segments

- Post-launch or during iterative design cycles to gather feedback on user satisfaction, feature usage, or suggestions for improvements

6. Card sorting

Tl;dr: card sorting.

Understand how users categorize and prioritize information within a product or service to structure your information in line with user expectations

✅ Helps create intuitive information architecture and navigation ❌ May not accurately reflect real-world user behavior and decision-making

Card sorting is an important step in creating an intuitive information architecture (IA) and user experience. It’s also a great technique to generate ideas, naming conventions, or simply see how users understand topics.

In this UX research method, participants are presented with cards featuring different topics or information, and tasked with grouping the cards into categories that make sense to them.

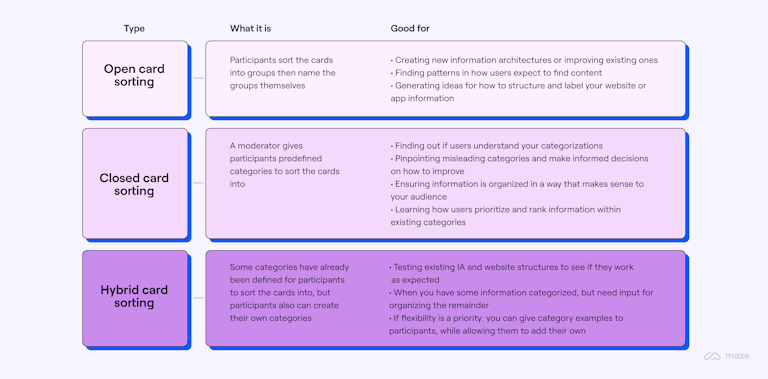

There are three types of card sorting:

- Open card sorting: Participants organize topics into categories that make sense to them and name those categories, thus generating new ideas and names

- Hybrid card sorting: Participants can sort cards into predefined categories, but also have the option to create their own categories

- Closed card sorting: Participants are given predefined categories and asked to sort the items into the available groups

Card sorting type comparison table

You can run a card sorting session using physical index cards or digitally with a UX research tool like Maze to simulate the drag-and-drop activity of dividing cards into groups. Running digital card sorting is ideal for any type of card sort, and moderated or unmoderated sessions .

Read more about card sorting and learn how to run a card sorting session here .

When to conduct card sorting

Card sorting isn’t limited to a single stage of design or development—it can be employed anytime you need to explore how users categorize or perceive information. For example, you may want to use card sorting if you need to:

- Understand how users perceive ideas

- Evaluate and prioritize potential solutions

- Generate name ideas and understand naming conventions

- Learn how users expect navigation to work

- Decide how to group content on a new or existing site

- Restructure information architecture

7. Tree testing

Tl;dr: tree testing.

Evaluate the findability of existing information within a product's hierarchical structure or navigation

✅ Identifies potential issues in the information architecture ❌ Focuses on navigation structure, not visual design or content

During tree testing a text-only version of the site is given to your participants, who are asked to complete a series of tasks requiring them to locate items on the app or website.

The data collected from a tree test helps you understand where users intuitively navigate first, and is an effective way to assess the findability, labeling, and information architecture of a product.

We recommend keeping these sessions short, ranging from 15 to 20 minutes, and asking participants to complete no more than ten tasks. This helps ensure participants remain focused and engaged, leading to more reliable and accurate data, and avoiding fatigue.

If you’re using a platform like Maze to run remote testing, you can easily recruit participants based on various demographic filters, including industry and country. This way, you can uncover a broader range of user preferences, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of your target audience.

To learn more about tree testing, check out this chapter .

When to conduct tree testing

Tree testing is often done at an early stage in the design or redesign process. That’s because it’s more cost-effective to address errors at the start of a project—rather than making changes later in the development process or after launch.

However, it can be helpful to employ tree testing as a method when adding new features, particularly alongside card sorting.

While tree testing and card sorting can both help you with categorizing the content on a website, it’s important to note that they each approach this from a different angle and are used at different stages during the research process. Ideally, you should use the two in tandem: card sorting is recommended when defining and testing a new website architecture, while tree testing is meant to help you test how the navigation performs with users.

8. Usability testing

Tl;dr: usability testing.

Observe users completing specific tasks with a product to identify usability issues and potential improvements

✅ Provides direct insights into user behavior and reveals pain points ❌ Conducted in a controlled environment, may not fully represent real-world usage

Usability testing evaluates your product with people by getting them to complete tasks while you observe and note their interactions (either during or after the test). The goal of conducting usability testing is to understand if your design is intuitive and easy to use. A sign of success is if users can easily accomplish their goals and complete tasks with your product.

There are various usability testing methods that you can use, such as moderated vs. unmoderated or qualitative vs. quantitative —and selecting the right one depends on your research goals, resources, and timeline.

Usability testing is usually performed with functional mid or hi-fi prototypes . If you have a Figma, InVision, Sketch, or prototype ready, you can import it into a platform like Maze and start testing your design with users immediately.

The tasks you create for usability tests should be:

- Realistic, and describe a scenario

- Actionable, and use action verbs (create, sign up, buy, etc)

Be mindful of using leading words such as ‘click here’ or ‘go to that page’ in your tasks. These instructions bias the results by helping users complete their tasks—something that doesn’t happen in real life.

✨ Product tip

With Maze, you can test your prototype and live website with real users to filter out cognitive biases, and gather actionable insights that fuel product decisions.

When to conduct usability testing

To inform your design decisions, you should do usability testing early and often in the process . Here are some guidelines to help you decide when to do usability testing:

- Before you start designing

- Once you have a wireframe or prototype

- Prior to the launch of the product

- At regular intervals after launch

To learn more about usability testing, check out our complete guide to usability testing .

9. Five-second testing

Tl;dr: five-second testing.

Gauge users' first impressions and understanding of a design or layout

✅ Provides insights into the instant clarity and effectiveness of visual communication ❌ Limited to first impressions, does not assess full user experience or interaction

In five-second testing , participants are (unsurprisingly) given five seconds to view an image like a design or web page, and then they’re asked questions about the design to gauge their first impressions.

Why five seconds? According to data , 55% of visitors spend less than 15 seconds on a website, so it;s essential to grab someone’s attention in the first few seconds of their visit. With a five-second test, you can quickly determine what information users perceive and their impressions during the first five seconds of viewing a design.

Product tip 💡

And if you’re using Maze, you can simply upload an image of the screen you want to test, or browse your prototype and select a screen. Plus, you can star individual comments and automatically add them to your report to share with stakeholders.

When to conduct five-second testing

Five-second testing is typically conducted in the early stages of the design process, specifically during initial concept testing or prototype development. This way, you can evaluate your design's initial impact and make early refinements or adjustments to ensure its effectiveness, before putting design to development.

To learn more, check out our chapter on five-second testing .

10. A/B testing

Tl;dr: a/b testing.

Compare two versions of a design or feature to determine which performs better based on user engagement

✅ Provides data-driven insights to guide design decisions and optimize user experience ❌ Requires a large sample size and may not account for long-term effects or complex interactions

A/B testing , also known as split testing, compares two or more versions of a webpage, interface, or feature to determine which performs better regarding engagement, conversions, or other predefined metrics.

It involves randomly dividing users into different groups and giving each group a different version of the design element being tested. For example, let's say the primary call-to-action on the page is a button that says ‘buy now’.

You're considering making changes to its design to see if it can lead to higher conversions, so you create two versions:

- Version A : The original design with the ‘buy now’ button positioned below the product description—shown to group A

- Version B : A variation with the ‘buy now’ button now prominently displayed above the product description—shown to group B

Over a planned period, you measure metrics like click-through rates, add-to-cart rates, and actual purchases to assess the performance of each variation. You find that Group B had significantly higher click-through and conversion rates than Group A. This indicates that showing the button above the product description drove higher user engagement and conversions.

Check out our A/B testing guide for more in-depth examples and guidance on how to run these tests.

When to conduct A/B testing

A/B testing can be used at all stages of the design and development process—whenever you want to collect direct, quantitative data and confirm a suspicion, or settle a design debate. This iterative testing approach allows you to continually improve your website's performance and user experience based on data-driven insights.

11. Concept testing

Tl;dr: concept testing.

Evaluate users' reception and understanding of a new product, feature, or design idea before moving on to development

✅ Helps validate and refine concepts based on user feedback ❌ Relies on users' perception and imagination, may not reflect actual use

Concept testing is a type of research that evaluates the feasibility, appeal, and potential success of a new product before you build it. It centers the user in the ideation process, using UX research methods like A/B testing, surveys, and customer interviews.

There’s no one way to run a concept test—you can opt for concept testing surveys, interviews, focus groups, or any other method that gets qualitative data on your concept.

*Dive into our complete guide to concept testing for more tips and tricks on getting started. *

When to conduct concept testing

Concept testing helps gauge your audience’s interest, understanding, and likelihood-to-purchase, before committing time and resources to a concept. However, it can also be useful further down the product development line—such as when defining marketing messaging or just before launching.

Which is the best UX research type?

The best research type varies depending on your project; what your objectives are, and what stage you’re in. Ultimately, the ideal type of research is one which provides the insights required, using the available resources.

For example, if you're at the early ideation or product discovery stage, generative research methods can help you generate new ideas, understand user needs, and explore possibilities. As you move to the design and development phase, evaluative research methods and quantitative data become crucial.

Discover the UX research trends shaping the future of the industry and why the best results come from a combination of different research methods.

How to choose the right user experience research method

In an ideal world, a combination of all the insights you gain from multiple types of user research methods would guide every design decision. In practice, this can be hard to execute due to resources.

Sometimes the right methodology is the one you can get buy-in, budget, and time for.

Gregg Bernstein , UX Researcher at Signal

UX research tools can help streamline the research process, making regular testing and application of diverse methods more accessible—so you always keep the user at the center of your design process. Some other key tips to remember when choosing your method are:

Define the goals and problems

A good way to inform your choice of user experience research method is to start by considering your goals. You might want to browse UX research templates or read about examples of research.

Michael Margolis , UX Research Partner at Google Ventures, recommends answering questions like:

- “What do your users need?”

- “What are your users struggling with?”

- “How can you help your users?”

Understand the design process stage

If your team is very early in product development, generative research —like field studies—make sense. If you need to test design mockups or a prototype, evaluative research methods—such as usability testing—will work best.

This is something they’re big on at Sketch, as we heard from Design Researcher, Tanya Nativ. She says, “In the discovery phase, we focus on user interviews and contextual inquiries. The testing phase is more about dogfooding, concept testing, and usability testing. Once a feature has been launched, it’s about ongoing listening.”

Consider the type of insights required

If you're looking for rich, qualitative data that delves into user behaviors, motivations, and emotions, then methods like user interviews or field studies are ideal. They’ll help you uncover the ‘why’ behind user actions.

On the other hand, if you need to gather quantitative data to measure user satisfaction or compare different design variations, methods like surveys or A/B testing are more suitable. These methods will help you get hard numbers and concrete data on preferences and behavior.

*Discover the UX research trends shaping the future of the industry and why the best results come from a combination of different research methods. *

Build a deeper understanding of your users with UX research

Think of UX research methods as building blocks that work together to create a well-rounded understanding of your users. Each method brings its own unique strengths, whether it's human empathy from user interviews or the vast data from surveys.

But it's not just about choosing the right UX research methods; the research platform you use is equally important. You need a platform that empowers your team to collect data, analyze, and collaborate seamlessly.

Simplifying product research is simple with Maze. From tree testing to card sorting, prototype testing to user interview analysis—Maze makes getting actionable insights easy, whatever method you opt for.

Meanwhile, if you want to know more about testing methods, head on to the next chapter all about tree testing .

Get valuable insights from real users

Conduct impactful UX research with Maze and improve your product experience and customer satisfaction.

Frequently asked questions

How do you choose the right UX research method?

Choosing the right research method depends on your goals. Some key things to consider are:

- The feature/product you’re testing

- The type of data you’re looking for

- The design stage

- The time and resources you have available

What is the best UX research method?

The best research method is the one you have the time, resources, and budget for that meets your specific needs and goals. Most research tools, like Maze, will accommodate a variety of UX research and testing techniques.

When to use which user experience research method?

Selecting which user research method to use—if budget and resources aren’t a factor—depends on your goals. UX research methods provide different types of data:

- Qualitative vs quantitative

- Attitudinal vs behavioral

- Generative vs evaluative

Identify your goals, then choose a research method that gathers the user data you need.

What results can I expect from UX research?

Here are some of the key results you can expect from actioning the insights uncovered during UX research:

- Improved user satisfaction

- Increased usability

- Better product fit

- Informed design decisions

- Reduced development costs

- Higher conversion rates

- Increased customer loyalty and retention

Tree Testing: Your Guide to Improve Navigation and UX

How To Choose Your Research Methodology

Qualitative vs quantitative vs mixed methods.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA). Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2021

Without a doubt, one of the most common questions we receive at Grad Coach is “ How do I choose the right methodology for my research? ”. It’s easy to see why – with so many options on the research design table, it’s easy to get intimidated, especially with all the complex lingo!

In this post, we’ll explain the three overarching types of research – qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods – and how you can go about choosing the best methodological approach for your research.

Overview: Choosing Your Methodology

Understanding the options – Qualitative research – Quantitative research – Mixed methods-based research

Choosing a research methodology – Nature of the research – Research area norms – Practicalities

1. Understanding the options

Before we jump into the question of how to choose a research methodology, it’s useful to take a step back to understand the three overarching types of research – qualitative , quantitative and mixed methods -based research. Each of these options takes a different methodological approach.

Qualitative research utilises data that is not numbers-based. In other words, qualitative research focuses on words , descriptions , concepts or ideas – while quantitative research makes use of numbers and statistics. Qualitative research investigates the “softer side” of things to explore and describe, while quantitative research focuses on the “hard numbers”, to measure differences between variables and the relationships between them.

Importantly, qualitative research methods are typically used to explore and gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of a situation – to draw a rich picture . In contrast to this, quantitative methods are usually used to confirm or test hypotheses . In other words, they have distinctly different purposes. The table below highlights a few of the key differences between qualitative and quantitative research – you can learn more about the differences here.

- Uses an inductive approach

- Is used to build theories

- Takes a subjective approach

- Adopts an open and flexible approach

- The researcher is close to the respondents

- Interviews and focus groups are oftentimes used to collect word-based data.

- Generally, draws on small sample sizes

- Uses qualitative data analysis techniques (e.g. content analysis , thematic analysis , etc)

- Uses a deductive approach

- Is used to test theories

- Takes an objective approach

- Adopts a closed, highly planned approach

- The research is disconnected from respondents

- Surveys or laboratory equipment are often used to collect number-based data.

- Generally, requires large sample sizes

- Uses statistical analysis techniques to make sense of the data

Mixed methods -based research, as you’d expect, attempts to bring these two types of research together, drawing on both qualitative and quantitative data. Quite often, mixed methods-based studies will use qualitative research to explore a situation and develop a potential model of understanding (this is called a conceptual framework), and then go on to use quantitative methods to test that model empirically.

In other words, while qualitative and quantitative methods (and the philosophies that underpin them) are completely different, they are not at odds with each other. It’s not a competition of qualitative vs quantitative. On the contrary, they can be used together to develop a high-quality piece of research. Of course, this is easier said than done, so we usually recommend that first-time researchers stick to a single approach , unless the nature of their study truly warrants a mixed-methods approach.

The key takeaway here, and the reason we started by looking at the three options, is that it’s important to understand that each methodological approach has a different purpose – for example, to explore and understand situations (qualitative), to test and measure (quantitative) or to do both. They’re not simply alternative tools for the same job.

Right – now that we’ve got that out of the way, let’s look at how you can go about choosing the right methodology for your research.

2. How to choose a research methodology

To choose the right research methodology for your dissertation or thesis, you need to consider three important factors . Based on these three factors, you can decide on your overarching approach – qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. Once you’ve made that decision, you can flesh out the finer details of your methodology, such as the sampling , data collection methods and analysis techniques (we discuss these separately in other posts ).

The three factors you need to consider are:

- The nature of your research aims, objectives and research questions

- The methodological approaches taken in the existing literature

- Practicalities and constraints

Let’s take a look at each of these.

Factor #1: The nature of your research

As I mentioned earlier, each type of research (and therefore, research methodology), whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed, has a different purpose and helps solve a different type of question. So, it’s logical that the key deciding factor in terms of which research methodology you adopt is the nature of your research aims, objectives and research questions .

But, what types of research exist?

Broadly speaking, research can fall into one of three categories:

- Exploratory – getting a better understanding of an issue and potentially developing a theory regarding it

- Confirmatory – confirming a potential theory or hypothesis by testing it empirically

- A mix of both – building a potential theory or hypothesis and then testing it

As a rule of thumb, exploratory research tends to adopt a qualitative approach , whereas confirmatory research tends to use quantitative methods . This isn’t set in stone, but it’s a very useful heuristic. Naturally then, research that combines a mix of both, or is seeking to develop a theory from the ground up and then test that theory, would utilize a mixed-methods approach.

Let’s look at an example in action.

If your research aims were to understand the perspectives of war veterans regarding certain political matters, you’d likely adopt a qualitative methodology, making use of interviews to collect data and one or more qualitative data analysis methods to make sense of the data.

If, on the other hand, your research aims involved testing a set of hypotheses regarding the link between political leaning and income levels, you’d likely adopt a quantitative methodology, using numbers-based data from a survey to measure the links between variables and/or constructs .

So, the first (and most important thing) thing you need to consider when deciding which methodological approach to use for your research project is the nature of your research aims , objectives and research questions. Specifically, you need to assess whether your research leans in an exploratory or confirmatory direction or involves a mix of both.

The importance of achieving solid alignment between these three factors and your methodology can’t be overstated. If they’re misaligned, you’re going to be forcing a square peg into a round hole. In other words, you’ll be using the wrong tool for the job, and your research will become a disjointed mess.

If your research is a mix of both exploratory and confirmatory, but you have a tight word count limit, you may need to consider trimming down the scope a little and focusing on one or the other. One methodology executed well has a far better chance of earning marks than a poorly executed mixed methods approach. So, don’t try to be a hero, unless there is a very strong underpinning logic.

Need a helping hand?

Factor #2: The disciplinary norms

Choosing the right methodology for your research also involves looking at the approaches used by other researchers in the field, and studies with similar research aims and objectives to yours. Oftentimes, within a discipline, there is a common methodological approach (or set of approaches) used in studies. While this doesn’t mean you should follow the herd “just because”, you should at least consider these approaches and evaluate their merit within your context.

A major benefit of reviewing the research methodologies used by similar studies in your field is that you can often piggyback on the data collection techniques that other (more experienced) researchers have developed. For example, if you’re undertaking a quantitative study, you can often find tried and tested survey scales with high Cronbach’s alphas. These are usually included in the appendices of journal articles, so you don’t even have to contact the original authors. By using these, you’ll save a lot of time and ensure that your study stands on the proverbial “shoulders of giants” by using high-quality measurement instruments .

Of course, when reviewing existing literature, keep point #1 front of mind. In other words, your methodology needs to align with your research aims, objectives and questions. Don’t fall into the trap of adopting the methodological “norm” of other studies just because it’s popular. Only adopt that which is relevant to your research.

Factor #3: Practicalities

When choosing a research methodology, there will always be a tension between doing what’s theoretically best (i.e., the most scientifically rigorous research design ) and doing what’s practical , given your constraints . This is the nature of doing research and there are always trade-offs, as with anything else.

But what constraints, you ask?

When you’re evaluating your methodological options, you need to consider the following constraints:

- Data access

- Equipment and software

- Your knowledge and skills

Let’s look at each of these.

Constraint #1: Data access

The first practical constraint you need to consider is your access to data . If you’re going to be undertaking primary research , you need to think critically about the sample of respondents you realistically have access to. For example, if you plan to use in-person interviews , you need to ask yourself how many people you’ll need to interview, whether they’ll be agreeable to being interviewed, where they’re located, and so on.

If you’re wanting to undertake a quantitative approach using surveys to collect data, you’ll need to consider how many responses you’ll require to achieve statistically significant results. For many statistical tests, a sample of a few hundred respondents is typically needed to develop convincing conclusions.

So, think carefully about what data you’ll need access to, how much data you’ll need and how you’ll collect it. The last thing you want is to spend a huge amount of time on your research only to find that you can’t get access to the required data.

Constraint #2: Time

The next constraint is time. If you’re undertaking research as part of a PhD, you may have a fairly open-ended time limit, but this is unlikely to be the case for undergrad and Masters-level projects. So, pay attention to your timeline, as the data collection and analysis components of different methodologies have a major impact on time requirements . Also, keep in mind that these stages of the research often take a lot longer than originally anticipated.

Another practical implication of time limits is that it will directly impact which time horizon you can use – i.e. longitudinal vs cross-sectional . For example, if you’ve got a 6-month limit for your entire research project, it’s quite unlikely that you’ll be able to adopt a longitudinal time horizon.

Constraint #3: Money

As with so many things, money is another important constraint you’ll need to consider when deciding on your research methodology. While some research designs will cost near zero to execute, others may require a substantial budget .

Some of the costs that may arise include:

- Software costs – e.g. survey hosting services, analysis software, etc.

- Promotion costs – e.g. advertising a survey to attract respondents

- Incentive costs – e.g. providing a prize or cash payment incentive to attract respondents

- Equipment rental costs – e.g. recording equipment, lab equipment, etc.

- Travel costs

- Food & beverages

These are just a handful of costs that can creep into your research budget. Like most projects, the actual costs tend to be higher than the estimates, so be sure to err on the conservative side and expect the unexpected. It’s critically important that you’re honest with yourself about these costs, or you could end up getting stuck midway through your project because you’ve run out of money.

Constraint #4: Equipment & software

Another practical consideration is the hardware and/or software you’ll need in order to undertake your research. Of course, this variable will depend on the type of data you’re collecting and analysing. For example, you may need lab equipment to analyse substances, or you may need specific analysis software to analyse statistical data. So, be sure to think about what hardware and/or software you’ll need for each potential methodological approach, and whether you have access to these.

Constraint #5: Your knowledge and skillset

The final practical constraint is a big one. Naturally, the research process involves a lot of learning and development along the way, so you will accrue knowledge and skills as you progress. However, when considering your methodological options, you should still consider your current position on the ladder.

Some of the questions you should ask yourself are:

- Am I more of a “numbers person” or a “words person”?

- How much do I know about the analysis methods I’ll potentially use (e.g. statistical analysis)?

- How much do I know about the software and/or hardware that I’ll potentially use?

- How excited am I to learn new research skills and gain new knowledge?

- How much time do I have to learn the things I need to learn?

Answering these questions honestly will provide you with another set of criteria against which you can evaluate the research methodology options you’ve shortlisted.

So, as you can see, there is a wide range of practicalities and constraints that you need to take into account when you’re deciding on a research methodology. These practicalities create a tension between the “ideal” methodology and the methodology that you can realistically pull off. This is perfectly normal, and it’s your job to find the option that presents the best set of trade-offs.

Recap: Choosing a methodology

In this post, we’ve discussed how to go about choosing a research methodology. The three major deciding factors we looked at were:

- Exploratory

- Confirmatory

- Combination

- Research area norms

- Hardware and software

- Your knowledge and skillset

If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below. If you’d like a helping hand with your research methodology, check out our 1-on-1 research coaching service , or book a free consultation with a friendly Grad Coach.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Very useful and informative especially for beginners

Nice article! I’m a beginner in the field of cybersecurity research. I am a Telecom and Network Engineer and Also aiming for PhD scholarship.

I find the article very informative especially for my decitation it has been helpful and an eye opener.

Hi I am Anna ,

I am a PHD candidate in the area of cyber security, maybe we can link up

The Examples shows by you, for sure they are really direct me and others to knows and practices the Research Design and prepration.

I found the post very informative and practical.

I struggle so much with designs of the research for sure!

I’m the process of constructing my research design and I want to know if the data analysis I plan to present in my thesis defense proposal possibly change especially after I gathered the data already.

Thank you so much this site is such a life saver. How I wish 1-1 coaching is available in our country but sadly it’s not.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

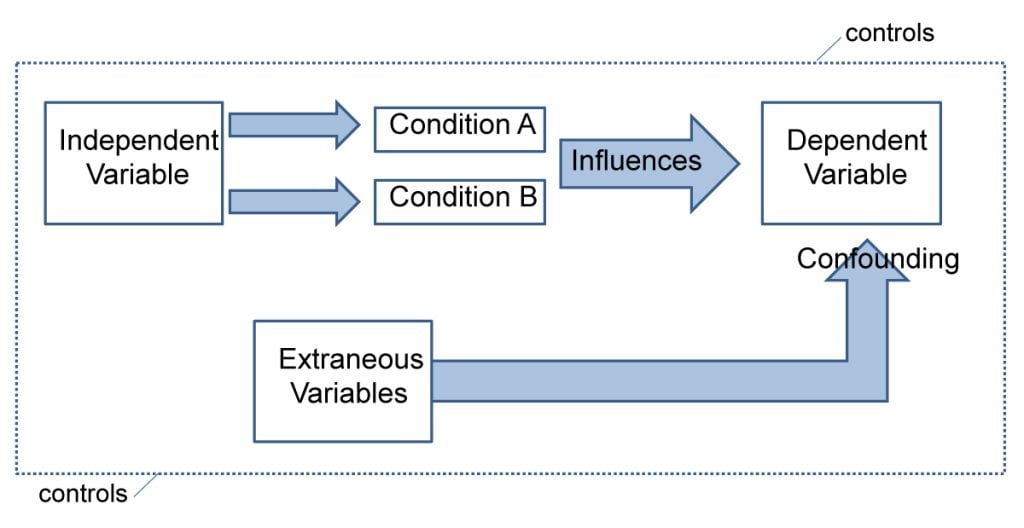

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

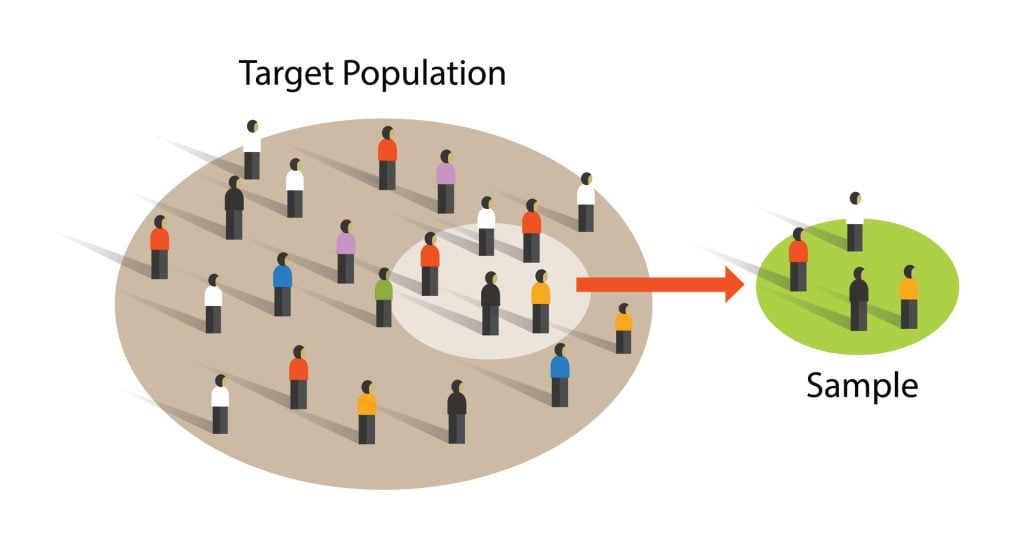

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE: Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE: If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].