Academic Programs

- Tuition & Financial Aid

Student Experience

The power of peer editing: five questions to ask in the review.

You’ve put in the work of researching, reading, writing and revising your paper. You’ve read it out loud and followed the assignment requirements.

You’re going strong, but there’s still another step you need to perfect your paper.

The peer edit.

Utilizing peer review in your writing process may not always be easy. You’re offering the paper that you’ve spent hours on up for critique.

But the peer edit can be so beneficial in enhancing your writing.

We may often think of “peer review” in terms of journal articles that have been analyzed and approved for accuracy. While your paper won’t require that same heightened, professional level of critique, bringing it to one of your peers—whether a classmate, a friend, a mentor—can enhance your research paper greatly.

Here, we share about the importance of incorporating a peer review process for both the author and the reviewer.

What is Peer Review?

A peer review of your research paper is different than the editing process that you go through. Rather than you going through each section, citation, argument in your paper, someone else does. A peer review involves handing it to someone you trust to allow them to read it and provide feedback to help make your paper the best it can be.

This is no small feat. It requires you to be vulnerable about what you’ve written. You need to be willing to accept mistakes you may make and be committed to accepting their suggestions as a way to grow in your writing and academic work.

Why is Peer Review Important?

This stage of the editing process is unique in that pulls in another perspective. Unlike you, your peer editor hasn’t been immersed in reading and research on your paper’s topic. They don’t know for certain what direction your paper will go or what your arguments are.

This new, objective perspective brings great value in revision.

A fresh set of eyes sees issues, gaps, mistakes and clouded arguments that you may have missed or had not thought of.

When your peer editor sits down and sifts through your paper, they provide both positive comments of what’s going well in the paper, as well as opportunities for improvement in areas that may be unclear. Their input helps make your paper better, if you choose to follow their recommendations.

If you’re working with a classmate, trade papers and review each other’s paper. This not only allows you to receive feedback on your paper, but it also develops your skills in providing feedback and looking for specific elements in a paper. You become a better editor. Whether you’re passing your paper off or reviewing a paper, your skills in writing can be greatly enhanced.

Questions to Ask in the Peer Review

In the peer review process, it’s helpful to have a plan of action in addressing the paper. Below are five questions that can help guide the process. Whether you’re the author or the reviewer (or both), these five questions can help focus your attention on key components of the assignment and enhance your skills.

Question 1: Is the Audience and Purpose of the Paper Clearly Established?

As a reviewer, one of the first things you want to be sure to notice in the paper is if you can figure out who the paper is addressing. The audience of the paper should be evident in reference to the topic, the tone of the paper and the type of language used.

For example, if the paper contains a lot of jargon and industry-specific language, you could infer that the audience would be familiar with those terms. If not, you may want to suggest using less jargon or explaining the terms used.

The purpose of the paper should also be very clear and straightforward to you as the new reader. The thesis statement, most often in the introduction, should clearly convey the purpose. But from the opening to the main arguments to the concluding statement, the purpose of the paper should be obvious.

As a peer reviewer, you can help the author determine if both the audience and purpose of the paper are clearly established early on in the paper.

Question 2: Does the Main Point Match the Thesis Statement?

One of the most important sentences in the paper is the author’s thesis statement. The location and type of thesis statement depends on the kind of essay or paper. However, as a general rule, thesis statements should be concise, straightforward and clear in addressing the main argument.

As a new reader, you as the reviewer can provide great insight into the clarity of the thesis.

The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina has a helpful article on crafting the perfect thesis. In this article, they suggest you ask the following questions of the thesis statement:

- Can I find the thesis statement?

- Is the thesis specific enough?

- Does the thesis answer the “so what” question of the paper?

- Does the rest of the paper support the thesis statement?

Peer review can help enhance a thesis statement by noticing gaps or questions in the argument.

Question 3: Does the Paper Flow Well?

When you’re the writer of a paper, you may work in sections. First, you tackle main point A, then move onto B, add in C and finish up with a conclusion.

When you’re a peer reviewer, you’re reading it for the first time all in one glance. With this new perspective, you can more easily identify gaps, questions and concerns in the structure of the paper.

Does point A leap to point B leaving little to hold on to? Note that the author should include a better transition. Are you left wondering what point C has to do with point A? Highlight the need for a better connection between main points.

With an objective, outside perspective, you can help the author improve the flow and clarity of their paper to communicate most effectively.

Question 4: What Areas Need Additional Description?

As a reviewer of a paper, you want to fully understand the content you’re reading. And when you come across a section that you’re left wondering what’s going on, it can be frustrating.

An important question to ask as you review a paper is if each section contains sufficient description and detail to add value to the paper. Notice those areas that come across as too vague and uninteresting. Highlighting the desire for more information encourages the author to add clarity and enhance their ability to communicate effectively.

Question 5: Do you notice any grammar or word choice mistakes?

While this final question may be the most obvious, you want to help your author out by pointing out those grammar and word choice errors that she may have missed.

- Is there an extra comma?

- Does she have subject-verb agreement in all sentences?

- Are most of the sentences in active voice?

- Did they incorrectly cite their source?

- Is there an extra tab in their reference page?

Being on the lookout for these types of errors can also help you as the reviewer to refresh your skills in grammar, punctuation, paragraphs and APA Style.

Incorporating a peer review process in finalizing a paper is immensely beneficial for both the author and the reviewer. Each elevates their writing skills. The author is more confident in the paper she submits and the reviewer grows in her editing ability.

Be Supported as You Pursue Your Goals

PGS offers numerous academic support resources to equip you to succeed in your degree program, whether that’s in writing a paper or other assignments. Visit our academic support web page to discover more essential tools.

Discover academic support

Ellie Walburg

Ellie Walburg (B.S.’17, M.B.A.’20) serves as the admissions communications coordinator for Cornerstone University’s Professional & Graduate Studies division.

Related Posts

Six Steps to Really Edit Your Paper

Let’s Chat! Best Strategies to Weave Personal Interviews Into Your Paper

Must Know Strategies for Achieving Work-Life Balance

6 Simple Ways to Conquer Your Fears of Returning to School

12 Methods to Significantly Improve Your Studying

Want to learn more about cu, connect with cu.

- Student Life

- About Cornerstone

- University Offices

- Faculty & Staff Directory

Recent News

- Cornerstone Continues to Advance Growth Plans

- Enrollment Deadline Extended for Fall 2024 at Cornerstone University

- Free Tuition Expands Through the Cornerstone Commitment Grant for 2024/25

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.8(7); 2022 Jul

Online peer editing: effects of comments and edits on academic writing skills

a National Research University Higher School of Economics, Institute of Education, Myasnitskaya Ulitsa, 20, Moscow, 101000, Russia

Galina Shulgina

b EFL Department, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), 291 Daehak-ro, Guseong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, South Korea

Jamie Costley

Associated data.

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Although the effects of online peer editing have been studied from a number of perspectives, it remains unclear how giving and receiving comments and edits affect student academic writing performance. The current study examined the influence of these aspects of peer editing on student academic writing performance in higher education during online peer editing. Participants were 76 students engaged in peer editing of one another's work in a graduate scientific writing course at a Korean university. The relationships between the giving and receiving of comments and edits, and student performance on their writing tasks were analyzed. Results showed that there is a positive correlation between the number of comments received and the student's writing score, whereas receiving edits had the opposite effect and was associated with lower student performance. Furthermore, no relationship was found between giving comments or edits and writing performance. These results add to the field's understanding of how specific elements of peer editing can impact students' performance.

Academic writing; Comments; Edits; Online collaborative learning; Peer feedback.

1. Introduction

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, blended and online learning have been used to provide students with diverse collaborative learning opportunities ( Al-Samarraie and Saeed, 2018 ; Zhu and Liu, 2020 ). Existing research recognizes that peer feedback is a valuable tool for improving student academic performance ( Al-Rahmi et al., 2015 ), thus interest has also grown in learner-to-learner interaction and how peer editing, as one type of collaboration, plays a role in interaction and student performance ( Zhou, 2017 ). Peer editing is defined as a collaborative learning process during which peers interact, review, critique, and edit each other's work ( Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ). It has been shown to be more effective than feedback from a teacher in some contexts ( Cho and MacArthur, 2011 ; Ciftci and Kocoglu, 2012 ; Nicol et al., 2014 ). In the context of academic writing, both providing and receiving feedback may help students improve their writing skills as this kind of peer interaction allows students to gain knowledge from different perspectives through social sharing ( Huisman et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, peer editing may lead both the giver and receiver of feedback to absorb information, and then decide how to judge the received messages through self-reflection ( Casey and Goodyear, 2015 ). Therefore, students may take some measures to narrow the gap and reach their potential after the feedback interpretation ( Carless and Boud, 2018 ; Wang et al., 2015 ; Zhu and Carless, 2018 ).

In online peer editing, providing comments or edits are the two most prevalent methods of providing feedback ( Magnifico et al., 2015 ). Comments refer to offering opinions and leaving suggestions, usually using the embed comments function in Microsoft word or another type of word processing software. On the other hand, providing edits means making direct changes to student original text, which generally shows up as a different color than what the original author wrote in ( Perron and Sellers, 2011 ). These two methods provide students an opportunity to discuss ideas and questions, review, criticize, and edit each other's work by adding suggestions and responding to them ( Lin and Reigeluth, 2016 ; Zhu and Carless, 2018 ), which activate key cognitive processes. Existing evidence supports the claim that peer feedback may improve students' academic writing performance ( Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ; Huisman et al., 2018 , 2019 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). However, there is a lack of clarity regarding how giving and receiving comments and edits will affect students' writing performance separately, especially in an online collaborative context. This study intends to explore the impact of comments and edits on students' writing performance from both giving and receiving perspectives.

2. Literature review

2.1. two methods of online peer editing.

As an in-class collaborative activity, giving and receiving peer feedback through online peer editing has been shown to greatly benefit student writing ( Casey and Goodyear, 2015 ; Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ; Huisman et al., 2018 , 2019 ). The enhancement that peer editing brings to writers seems to be beyond an improvement in the quality of a particular piece of writing. Engaging in peer editing helps students develop greater self-assessment skills when compared with editing alone ( Nulty, 2011 ). It allows students to learn to critically review and revise their writing from the audience's perspective, thereby developing their independent thinking skills and self-directed learning ( Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ). Through communication and interaction with their peers, students become more actively engaged in their own writing ( Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006 ).

Online peer editing allows students to offer comments or edits to their peers. Specifically, comments refer to the leaving suggestions to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their peers, while edits are the act of inserting and/or deleting text written by other students ( Liu and Edwards, 2018 ). Once the editor has made the edits or left comments, the author of the text may respond to the comment, mark it as resolved, or delete it. In terms of edits of others, students can delete words and phrases directly, correct others’ spelling mistakes and add sentences or paragraphs. Compared to comments, edits provide direct changes without supporting arguments, which may, in some cases, prevent the author of the text from understanding the reasons for the proposed solution and, in turn, cause the author to decline it ( Liu and Edwards, 2018 ). Furthermore, the writer can often accept the changes without checking or understanding why the changes were made. Understanding the problem is an important predictor of effective feedback implementation ( Nelson and Schunn, 2009 ).

2.2. The influence of receiving comments on learning

Many studies have shown improvements in performance after students received comments during the learning process ( Huisman et al., 2018 , 2019 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). A possible explanation is that receiving comments from others is helpful to student learning because during this process, receivers are encouraged to participate in the evaluation and reflection of their peers' comments ( Shvidko, 2015 ). Students may improve themselves as their peer has identified the pros and cons of their essays, and then the author may think about whether they agree with those opinions and find solutions to solve the problems noted by the reviewer ( Nicol et al., 2014 ).

However, it is not always the case that receiving comments will lead to improvements in writing or learning performance. For instance, some research has pointed out that receiving summaries, explanations, or ideas in comments is more helpful to student writing than some direct praise or criticism ( Wu and Schunn, 2020 ). Sometimes, students feel less motivated when they receive comments with no supporting evidence, which reduces the potential benefits of this type of peer activity ( Zhang and Hyland, 2018 ). Furthermore, comments may be ineffective if students do not consider, organize or fully implement them during the reflecting process ( Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006 ). Holmes and Papageorgiou (2009) suggested that if the comments students receive are of low quality or the allocation is not appropriate, they will not help students' writing. Thus, there is a lack of clarity on how different received comments affect students’ writing.

2.3. The influence of giving comments on learning

How giving comments might affect academic writing is another area of required investigation that is within the scope of peer feedback. There is some evidence that giving feedback may be even more important than receiving it ( Ion et al., 2019 ; Rouhi and Azizian, 2013 ). Students may develop their critical thinking abilities and metacognitive strategies through providing comments, and in some cases, their ability to problem-solve can be increased to a greater degree than those who receive feedback during the process of writing ( Cho and Cho, 2011 ; Frank et al., 2018 ). Through this process, students may explore ideas collaboratively and focus on the connections between ideas while seeking to improve their writing ( Neumann and McDonough, 2015 ).

During this process, students may produce, present, and develop their knowledge of a certain topic and share that knowledge with another learner whose work they are giving feedback on ( Tai et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, many studies have stated that generating explanations is an effective method to improve one's own writing ( Dunlosky et al., 2013 ; Nicol et al., 2014 ; Tempelaar et al., 2015 ). For instance, Cho and MacArthur (2010) pointed out that when students try to give an explanation by themselves, it is much more useful than receiving them from an expert. Those findings revealed that judging from a given text can enhance students' writing performance ( Henderson and Phillips, 2015 ).

However, effective feedback necessitates deliberate coordination between the provider and recipient in a peer feedback-friendly atmosphere ( Ray and Singh, 2018 ). In general, comments as a type of peer feedback should be provided only when the learner welcomes it ( Jug et al., 2019 ). In some cases, certain comments can incite social conflicts in groups so that some comments givers may try to offer praises or other kind suggestions to avoid conflicts within groups, which may not lead to the best learning outcomes ( Fong et al., 2018 ).

2.4. Receiving edits and student performance

Research has revealed that students can gain insights into their collaborators’ views on their work by reflecting on edits that others make of their work ( Mabbott and Bull, 2006 ). According to the quality of the edits and where they are directed, students can begin to understand the quality of their own work ( Hattie and Clarke, 2018 ). Furthermore, edits can range from simple superficial corrections, such as grammar or spelling errors, or more elaborate and deeper changes directed at the conceptual and knowledge level; after receiving and judging these edits, students may be more sensitive to avoid the same mistakes in their writing ( Petrović et al., 2017 ).

On the one hand, highlighting spelling or grammar mistakes helps to improve the quality of writing. On the other hand, getting only grammatical edits as feedback may make students question their peers' abilities and cause feelings of disappointment ( Birnholtz and Ibara, 2012 ; Liu and Edwards, 2018 ). In general, students believe that collaborative writing and peer editing lead to better quality work. However, while they may perceive their edits and suggestions as a source for improvement for others' texts, sometimes received edits may be seen as an intervention which makes their texts worse ( Blau and Caspi, 2009 ). Also, edits often only highlight mistakes, which makes students perceive them as direct criticism, which may be harmful for subsequent improvement of students' writing ( Tseng and Tsai, 2007 ), lower their sense of psychological ownership ( Blau and Caspi, 2009 ), or lead to conflict ( Birnholtz and Ibara, 2012 ). Interestingly, a high number of modifications may hurt students' feelings, while a small number of edits makes them feel uninvolved by their classmates. A lack of edits may be interpreted by students as an indication of disengagement or disinterest, which could negatively impact students’ writing ( Mabbott and Bull, 2006 ).

2.5. Giving edits and student performance

Many studies have confirmed the effectiveness of online editing among peers, such as edits of others, for improving their active learning, as discussed above regarding comments ( Wang, 2015 ). For instance, reading others' writing and correcting their errors can motivate them to seek information about what they are reading about or double-check their own understanding of concepts they are reviewing ( Wang, 2015 ; Yen et al., 2015 ).

However, several circumstances, such as a lack of expertise with peer editing in general and online learning in particular, may have a detrimental impact on the usefulness of edits in improving the student writing performance. According to Ishtaiwa and Aburezeq (2015) , opaque criteria for peer editing and the lack of information about the expected level of contribution may lead to minimal and/or overly formal student participation. Some students may also have difficulties with using some functions of the learning environment as a new instrument for learning, which can limit their participation ( Ishtaiwa and Aburezeq, 2015 ). Moreover, students often may try to avoid editing their peers’ work because of the risk of upsetting the author ( Birnholtz and Ibara, 2012 ; Coyle, 2007 ).

2.6. Present study

The present study seeks to explore the influence of giving and receiving peer feedback in the form of comments and edits on student learning. This study looks at the total amounts of comments and edits and does not investigate the quality or function of comments or edits. The reasons for this is that the first step in this type of research agenda is to look at the impact of the quantity of peer feedback elements on student writing performance. This gives a broad overview of how comments and/or edits impact student performance. This is a necessary first step in the understanding of how peer-to-peer feedback behaviors have on author and editor performance. Furthermore, when dealing with a high volume and number of students, as well as the use of technology for statistics and analysis, the amount of peer feedback is easier to obtain than the quality. This means that the outputs of comments and edits are readily available in the form of learning analytic visualizations more so than measures of edit or comment quality and function. Furthermore, this type of information can be more potential ready use for instructors to better understand online peer editing and implement instructional design choices that may help students improve their writing skills.

To achieve this, the present study collects data on comments and edits from peer editing sessions from 76 students over 5 cases of peer editing. Since most extant research explored the role of peer editing in broad ways such as surveys or interviews, the field has not yet dug deeply into how the volume of different peer editing methods influence students' learning performance. This study looks at peer editing by measuring comments and edits in students’ written documents directly in a collaborative learning context. To measure the performance of students, the overall individual writing scores are representative of the students' learning outcomes and performance during the course. The existing literature discussed above suggests that, on balance, giving and receiving comments and/or edits will lead to better learning performance and based on this, the present study has four main hypotheses:

Students who receive more comments will perform better in their writing.

Students who give more comments will perform better in their writing.

Students who receive more edits will perform better in their writing.

Students who give more edits will perform better in their writing.

3. Methodology

3.1. participants and learning context.

There were 76 students engaged in peer editing of each other's work in 4 sections of a graduate scientific writing course at a Korean university. Each of the 4 course sections had between 16 to 22 students. Among the subjects, 49 subjects were master's students, and 27 were in a doctoral program. There were 22 females and 54 males. The average age of the students was 25.7 (SD = 3.6), with a minimum age of 21 and a maximum age of 39 among the participants in the present study. The purpose of the scientific writing course was to teach students to write a journal manuscript on their graduate research findings ( Zhang et al., 2021 ). The course was given in an online format, and pre-recorded video lectures were provided on the course learning management system for students to view at their convenience. The course consists of 10 instructional weeks that respectively include 4 to 8 lecture videos, totaling 56 lecture videos for the course. The average length of a course video is nearly 12 min and covers topics related to scientific writing for graduate STEM students.

The ten instructional weeks of the course were grouped into two-week units designed to provide instruction related to the five major sections of a journal manuscript: 1) Introduction, 2) Methodology, 3) Results, 4) Discussion & Conclusion, and 5) Abstract. In the first week of a given unit, students would watch a set of videos specific to the journal section of interest for that unit. Videos in this first week explained the purpose, function, characteristics, and conventions of the given section of a journal manuscript. After viewing this initial set of videos, students would attend a live session of the course with the course instructor using Zoom teleconferencing software. After leading a short discussion on the topics of the course videos and answering any student questions, the instructor would put students into small groups for collaborative learning activities to reinforce their learning regarding the concepts covered in the lecture videos.

The second week of the unit consisted of another set of lecture videos often providing instruction on writing style, language, and grammar related to the same manuscript section focused on in the first week of the unit. Prior to the Zoom meeting of the second week of the unit, students were instructed to compose a first draft of a journal article section of focus in the unit and bring it to the meeting. While no special instructions were given to students in terms of word count, students were advised to consult journal style guides and published papers in their fields of study in deciding on the length and format of their written assignments. At the Zoom meeting, the instructor led a short discussion and answered questions and then provided instruction for the peer editing session. Then, students grouped themselves into dyads, and the instructor moved them into breakout rooms so that they could peer edit one another's writing. In the first week of the semester, students filled out a short questionnaire on their major, degree program, areas of research interest or expertise, and the title of their research project or paper. This information was shared with the class through a spreadsheet so that students could choose a peer editing partner with research interests that were as aligned as possible with their own. Ethical approval from a KAIST Institutional Review Board (IRB) named “The Effects of Collaborative Notetaking on Learning Outcomes in Online and Blended Learning Environments'' was received before conducting the questionnaire.

A Google Doc was created by the course instructor for each member of the dyad for each of five peer editing sessions, which corresponded to the Introduction, Methodology, Results, Discussion & Conclusion, and Abstract sections. Students were instructed to copy and paste their first draft of the journal manuscript section into the corresponding peer editing Google Doc and to share with and provide editing privileges to their dyad member. The peer editing Google Doc contained instructions for the students on how to peer edit their partner's work, and a video on how to peer edit an assignment was provided on the course learning management system. The instructions provided in the video and within each peer editing Google Doc required the students to track any changes to their partner's paper using “suggesting mode” rather than “editing mode”. This was done so that the original author of the work could easily see any changes that were made and would easily be able to accept or reject any changes according to preference. In addition, students were encouraged to make use of the embedded comment feature within the Google Docs platform, which allows a collaborator to highlight a given section of text and embed a comment that shows up in the right margin of the document. Replies to such comments are possible, so that the author and editor can engage in a comment thread if they desire. After providing such edits and comments, reviewers were asked to grade the quality of the draft using a specialized rubric provided by the course instructor adapted from Clabough and Clabough (2016) . The rubric assessed five criteria: four criteria specific to the content and function of a given section of a journal article and one general criterion related to the clarity and readability of the writing, and allowed students to rate the quality level of each criteria as “poor,” “average,” or “excellent”, giving scores of 0, 1, and 2, respectively. Accordingly, these subscores were added up and amounted to a final score from 0 to 10.

At the end of this second live Zoom meeting for a given unit, students were instructed to consider their partner's feedback on the first draft of their assignment and to create a final draft for submission on the course learning management system for final grading by the course instructor. Students were given two days to complete the revision, and the course instructor provided comments, suggestions, edits, and a final grade out of 10 points using the same specialized rubric that was used for peer editing. This 10-point grade accounted for 10% of the student's final grade in the course. Completion and grading of the final draft marked the end of a given unit, and the following week would begin a new unit of the course until all sections of the paper were completed.

3.2. Research instruments

Comments. Students can develop critical thinking skills, improve the structure of their writing, and gain new insights and perspectives when provided with written comments from their classmates ( Sung et al., 2016 ). In the present study, comments refer to written feedback students receive from a peer editing partner on their individual writing using embedded commenting features within the Google Docs platform. Such embedded comments appear as small frames in the margin of the document. Prior research has shown that embedded comments can be used to provide feedback and assessment at a variety of levels, from superficial, such as grammar and spelling, to highly complex, including deeper conceptualizations and connections of knowledge ( Luo et al., 2016 ; Strijbos and Wichmann, 2018 ; Sung et al., 2016 ). Embedded comments can also be used by editors and coauthors to ask questions and engage in online discussions in the margins of the document. For the purposes of this study, the number of embedded comments and replies to comments within a given peer editing Google Doc serves as the comments variable.

Edit of others. When peer editing one another's writing, students change or delete the writing of the original author of a text. In prior research, an increase in such edits of others was shown to correlate positively with students' ability to write clearly and to support their claims with evidence ( Yim et al., 2017 ). The edits of others variable i s the total number of characters inserted by a collaborator after the collaborator deleted text from the original author. This definition was originally provided by Wang et al. (2015) in their paper presenting DocuViz, an add-on for Google Chrome that enables collaborative data, including edits of others, to be mined and visualized from Google Docs. In the present research, DocuViz was used to mine this editing data from each of the peer editing Google Docs.

Writing assignments. The primary assignments for the scientific writing course examined in this study were the five major sections of a research manuscript: 1) Introduction, 2) Methodology, 3) Results, 4) Discussion & Conclusion, and 5) Abstract. Using a rubric adapted from Clabough and Clabough (2016) , these writing assignments were assessed by the course instructor and given a grade from 0 to 10. These assignment grades were then tallied to give a total writing score out of 50 points, accounting for 50% of the total grade points for the course.

Correlational analyses were conducted to examine the connection between the variables and then evaluated for significance to test the hypotheses. The first step of looking into the research questions was an overview of the main variables that were used as a part of this study. As can be seen in Table 1 , the authors wrote on average 2588 words, with the longest piece of work being 6829 words, and the shortest being 410 words. The students performed well in regards to their writing score, with the average score being 41 out of a possible 50. Also, worth noting is the lowest writing score attained in the sample population (32) is considered a passing grade for the writing portion of this class. The comments received and comments given have the same mean score of 11.16 embedded comments as these variables are the inverse of each other. As with comments, the edits received and edits given number of key-strokes have the same mean, which in the case of edits was 3881.38 keystrokes.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for the main variables used in the study.

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author volume | 410 | 6829 | 2587.68 | 1354.07 | Words |

| Writing score | 32 | 50 | 41.36 | 3.96 | Rubric based score |

| Comments received | 0 | 41 | 11.16 | 10.93 | Embedded comments |

| Edits received | 10 | 30818 | 3881.38 | 5539.64 | Keystrokes |

| Comments given | 0 | 41 | 11.16 | 11.16 | Embedded comments |

| Edits given | 0 | 30818 | 3881.38 | 5539.64 | Keystrokes |

To look more closely at the variables that could be analyzed as a part of this study, correlations between all main variables as well as author volume were calculated ( Table 2 ). The results show that receiving comments had a statistically significant positive association with writing score (.232∗). In contrast, receiving edits had a negative statistically significant association with writing score (-.325∗∗). In regards to the giving of comments and the giving of edits, neither variable had a statistically significant relationship with writing score.

Table 2

Correlations between all variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Author volume | 1 | |||||

| 2 | Writing score | .521∗∗ | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Comments received | .466∗∗ | .232∗ | 1 | |||

| 4 | Edits received | .018 | -.325∗∗ | -0.19 | 1 | ||

| 5 | Comments given | .162 | .087 | .485∗∗ | -.117 | 1 | |

| 6 | Edits given | .270∗ | -.068 | -.118 | .327∗∗ | -.181 | 1 |

∗∗Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

∗Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Notable on this table are the positive associations between author volume and writing score (.521∗∗), comments received (.466∗∗) and edits given (.270∗). This shows that authors who produced more words had higher writing results. Furthermore, individuals who wrote more words encouraged their peers to comment on them more. Finally, people who wrote more appeared to be more likely to edit the work of others. Another finding that can be seen in this table is the positive relationship between giving comments and receiving comments (.485∗∗). Furthermore, there was also a positive relationship between receiving edits and giving edits (.327∗∗). These two results suggest that pairs tended to fall into a pattern of engaging in the same types of peer-editing - either commenting, or editing.

5. Discussion

Although previous research has investigated online peer editing, it remains unclear how the giving and receiving of comments and edits affect student writing performance. The current study explores the influence of these aspects on student academic writing performance in higher education by using Google Docs. The results show that receiving comments is positively associated with student writing performance. However, receiving edits has a negative association with student writing. In terms of giving comments and giving edits, neither technique has a statistically significant association with writing performance.

The findings indicate that students who receive more comments will write better papers, which coincides with evidence suggesting that students may improve their writing performance after receiving comments from their peers in the learning process ( Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ; Huisman et al., 2018 , 2019 ; Shvidko, 2015 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ). Students may improve their work based on the feedback they received, which identifies their writing's strengths and faults ( Casey and Goodyear, 2015 ). Students may identify answers to difficulties raised by the reviewer because of self-reflection, and their writing may improve as a result ( Nicol et al., 2014 ). This finding may be also due to the positive perceptions and attitudes of the learners because looking at others' comments through Google Docs provides learners with enough time and space to think, judge, and choose to accept or reject these suggestions, and eventually enhance their writing skills ( Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017 ). All students are masters and PhD in present study; thus, student writing may be in high quality and students may be more likely to receive higher quality comments from their high-performing peers. On the contrary, some research revealed that not all kinds of comments are effective ( Jug et al., 2019 ; Ray and Singh, 2018 ). One possible interpretation of this statement is that some comments are not well-structured or well-considered, so that students refuse to accept them. However, this research found that comments as suggestions and effective learning resources are useful to enhance student academic writing. As a result, comments should be expressed directly and clearly, and they should be comprehended independently of the giver; otherwise, receivers may not be able to grasp them, becoming confused and, in some cases, refusing to provide feedback ( Hattie and Clarke, 2018 ; Holmes and Papageorgiou, 2009 ).

Another finding of the present study is that giving comments during online peer editing has no association with students' writing performance. This contrasts with previous literature where giving comments to their peers can promote students' critical thinking and metacognitive strategies, thereby enabling improvement of their writing skills ( Cho and Cho, 2011 ; Frank et al., 2018 ; Dunlosky et al., 2013 ; Nicol et al., 2014 ). The finding in the present study may be related to the concerns of some feedback givers. For instance, students may try to avoid social conflicts within groups by only giving praise or soft advice to others, which may lead them to not engage personally with others’ work ( Fong et al., 2018 ; Robertson, 2011 ). Therefore, perhaps instructions are needed to guide students on how to deliver comments at deeper levels to improve writing before conducting online peer editing so that the givers of comments can also benefit from peer editing.

The most surprising result of the present study also shows that receiving edits negatively correlates with student writing performance, suggesting that such behaviors may stop students from improving their writing skills. This finding seems to contradict the work of Mabbott and Bull (2006) , who claimed that students will be more sensitive to their mistakes after reading and judging the edits from their peers, which should lead to better performance. However, the negative correlation between receiving edits and student writing is in line with Liu and Edwards (2018) , who illustrated that students may be upset or question the ability of their peers when they only received edits related to grammar or spelling errors. In turn, the effects of peer editing may rely on the quality of the reviewed writings ( Cho and Cho, 2011 ). When the editors look through a paper of poor quality, too many grammar and spelling errors make it difficult to give in-depth edits, thereby limiting the effects of edits on their peer's writing. For low-quality writing, it is possible that their peers are confused about the writing itself so that they are not able to offer edits. Interestingly, the average amount of edits received by students was 3881.38 characters. Receiving such large volumes of edits during collaborative learning may increase the workload of students' reflection, and students may only choose to accept all suggested edits without considering their accuracy, which may lead to a worse outcome in writing performance.

It is suggested by the results of the current study that giving more edits in groups does not drive better writing performance. It refutes the claim that reviewing others' sentences and pointing out their mistakes is a useful method to look for information and double check their own understanding of concepts mentioned by their peers ( Wang et al. 2015 ; Yen et al., 2015 ). This result likely has several causes. The first is that students may lack experience in using online collaborative technologies and giving edits online through Google Docs, which may hinder them from participating in online peer editing and gaining benefits from it ( Ishtaiwa and Aburezeq, 2015 ). Ludemann and McMakin (2014) found negative relationships between the first experience as a peer editor and assignment grades; however, for the second and subsequent sessions, this correlation did not hold. In the present study, five peer editing sessions were conducted. According to Jeffery et al. (2016) , the accuracy of peer editing is greatly impacted by the number of reviewers, and they suggested that there should be at least three reviewers for one academic paper. Therefore, interaction between two people may influence the results, especially if the feedback givers have little experience in peer editing. The second possible explanation for the negative association found in the present study is that students try to edit others’ sentences kindly and superficially to avoid upsetting the author ( Birnholtz and Ibara, 2012 ; Coyle, 2007 ). This type of editing may distract the author without any benefit as the edits are superficial and not helpful in increasing writing performance.

There are also some other interesting findings in the present study. For instance, positive correlations were found between author volume and their writing scores, comments received, and edits given. It is possible that when students have a well-rounded understanding of the topic, they may hold a positive attitude and prefer to express more in their writing. In turn, they will get higher scores than those who did not put a lot of effort into writing assignments. In addition, when the author volume becomes higher, there are more materials that can be provided to their peers for feedback, so that students may offer more comments and edits to their peers ( Nicol et al., 2014 ).

There is also a positive relationship between comments received and comments given, and between edits received and edits given. When considering the influence of peer review, one should remember that every student is both a reviewer and a writer ( Cho and Cho, 2011 ). Specifically, students act as reviewers to comment or edit on others' drafts, and as authors, they receive comments or edits from other reviewers’ perspectives ( Cho and Cho, 2011 ). Thus, the effect of receiving comments/edits and the role of giving comments/edits need to be considered together.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this research was to explore how giving and receiving comments and edits influence students' writing performance. Since previous studies used broad methods to investigate students' perspectives on peer editing, this paper fills a gap in the research on online peer feedback by categorizing feedback as comments or edits and separately examining them in documents. One of the contributions of the present study is that it reveals receiving comments during online peer editing is a useful method to improve student writing performance, which provides empirical evidence that judging and reflecting on received comments enables students to enhance their writing skills. Interestingly, another finding from this research showed that there is a negative correlation between receiving edits and students' writing performance, which may be due to the large volume of edits and the low level of students’ writing abilities. However, there is no statistically significant correlation between giving comments and/or edits and student writing performance. These findings suggest two important recommendations for instructors facilitating online peer editing sessions: 1) encourage students to participate in self-reflection after receiving comments actively and 2) provide some instructions before peer editing on how to give deeper levels of comments and edits during online peer editing. For example, before online collaboration, instructors can show students the example of good peer feedback and point out what types of feedback can enhance their writing.

Since online learning has become increasingly popular, the present research is particularly relevant as it suggests new avenues for improving students' online writing performance in online settings. However, there are some limitations to this research. For instance, in this study, students could choose their own partners rather than having partners randomly assigned to conduct online peer editing. In this case, students may prefer to give kind suggestions or less edits to protect their friends' feelings, which may have a negative influence on the outcome of this research. Thus, future research should assign students to different groups randomly to increase the validity of research. Another limitation is that while this study accounts for edits and comments that were provided by peers within a Google Doc, it does not account for backchannel communication occurring outside the document, including discussions during Zoom video conferencing while the peers edited each other's’ work or subsequent communications proceeded via email or text messaging. While such backchannel communications would likely provide a rich source of data on students' collaborative processes, the collection of such information would be invasive to students' privacy and is not allowed by the institutional review board that granted permission for the present study. One other limitation is that the present study only took into account the number of comments and modifications, not their intention or quality. More extensive research in the future might take into account both the quantity and quality of comments and edits. More study could be done to develop a systematic method for accounting for these two factors. Although previous research has investigated the influence of peer editing on student academic writing, further exploration is needed on how giving and receiving peer feedback online affect students' writing. Since comments and edits, two popular modes of online editing, play an essential role in cooperative learning, more research is needed to explore the impact of peer editing in online contexts.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Han Zhang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Galina Shulgina: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mik Fanguy: Performed the experiments.

Jamie Costley: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Declaration of interests statement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This article is an output of a research project implemented as part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University). Supplementary content related to this article has been published online at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09822 .

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

- Al-Rahmi W., Othman M.S., Yusuf L.M. The role of social media for collaborative learning to improve academic performance of students and researchers in Malaysian higher education. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 2015; 16 (4) [ Google Scholar ]

- Al-Samarraie H., Saeed N. A systematic review of cloud computing tools for collaborative learning: opportunities and challenges to the blended-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2018; 124 :77–91. [ Google Scholar ]

- Birnholtz J., Ibara S. 2012. Tracking changes in collaborative writing: edits, visibility and group maintenance. Proceedings of the ACM 2012 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work; pp. 809–818. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blau I., Caspi A. Vol. 12. 2009. What type of collaboration helps? Psychological ownership, perceived learning and outcome quality of collaboration using Google Docs. In Proceedings of the Chais Conference on Instructional Technologies Research; pp. 48–55. No. 1. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carless D., Boud D. The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2018; 43 (8):1315–1325. [ Google Scholar ]

- Casey A., Goodyear V.A. Can cooperative learning achieve the four learning outcomes of physical education? A review of literature. Quest. 2015; 67 (1):56–72. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho K., MacArthur C. Student revision with peer and expert reviewing. Learn. InStruct. 2010; 20 (4):328–338. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho K., MacArthur C. Learning by reviewing. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011; 103 (1):73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho Y.H., Cho K. Peer reviewers learn from giving comments. Instr. Sci. 2011; 39 (5):629–643. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ciftci H., Kocoglu Z. Effects of peer e-feedback on Turkish EFL students' writing performance. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2012; 46 (1):61–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- Clabough E.B., Clabough S.W. Using rubrics as a scientific writing instructional method in early stage undergraduate neuroscience study. J. Undergrad. Neurosci. Educ. 2016; 15 (1):A85–A93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5105970/ Retrieved online at. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coyle J.E., Jr. 2007. Wikis in the College Classroom: A Comparative Study of Online and Face-to-Face Group Collaboration at a Private Liberal Arts University (Doctoral dissertation, Kent State University) http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=kent1175518380 [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunlosky J., Rawson K.A., Marsh E.J., Nathan M.J., Willingham D.T. Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Interest. 2013; 14 (1):4–58. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ebadi S., Rahimi M. Exploring the impact of online peer-editing using Google Docs on EFL learners’ academic writing skills: a mixed methods study. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017; 30 (8):787–815. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank B., Simper N., Kaupp J. Formative feedback and scaffolding for developing complex problem solving and modelling outcomes. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2018; 43 (4):552–568. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fong C.J., Schallert D.L., Williams K.M., Williamson Z.H., Warner J.R., Lin S., Kim Y.W. When feedback signals failure but offers hope for improvement: a process model of constructive criticism. Think. Skills Creativ. 2018; 30 :42–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J., Clarke S. Routledge; 2018. Visible Learning: Feedback. [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson M., Phillips M. Video-based feedback on student assessment: scarily personal. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2015; 31 (1) [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmes K., Papageorgiou G. Good, bad and insufficient: students' expectations, perceptions and uses of feedback. J. Hospit. Leisure Sports Tourism Educ. 2009; 8 (1):85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huisman B., Saab N., Van Driel J., Van Den Broek P. Peer feedback on academic writing: undergraduate students’ peer feedback role, peer feedback perceptions and essay performance. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2018; 43 (6):955–968. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huisman B., Saab N., van den Broek P., van Driel J. The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: a Meta-Analysis. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2019; 44 (6):863–880. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ishtaiwa F.F., Aburezeq I.M. The impact of Google Docs on student collaboration: a UAE case study. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction. 2015; 7 :85–96. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ion G., Sánchez Martí A., Agud Morell I. Giving or receiving feedback: which is more beneficial to students’ learning? Assess Eval. High Educ. 2019; 44 (1):124–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeffery D., Yankulov K., Crerar A., Ritchie K. How to achieve accurate peer assessment for high value written assignments in a senior undergraduate course. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2016; 41 :127–140. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jug R., Jiang X.S., Bean S.M. Giving and receiving effective feedback: a review article and how-to guide. Arch. Pathol. Lab Med. 2019; 143 (2):244–250. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin C.Y., Reigeluth C.M. Scaffolding wiki-supported collaborative learning for small-group projects and whole-class collaborative knowledge building. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016; 32 (6):529–547. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu J., Edwards J.H. University of Michigan Press; 2018. Peer Response in Second Language Writing Classrooms. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludemann P.M., McMakin D. Perceived Helpfulness of Peer Editing Activities: first-year students' views and writing performance outcomes. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2014; 13 (2):129–136. [ Google Scholar ]

- Luo L., Kiewra K.A., Samuelson L. Revising lecture notes: how revision, pauses, and partners affect note taking and achievement. Instr. Sci. 2016; 44 (1):45–67. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mabbott A., Bull S. Student preferences for editing, persuading, and negotiating the open learner model. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2006:481–490. [ Google Scholar ]

- Magnifico A.M., Curwood J.S., Lammers J.C. Words on the screen: broadening analyses of interactions among fanfiction writers and reviewers. Literacy. 2015; 49 (3):158–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nelson M.M., Schunn C.D. The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instr. Sci. 2009; 37 (4):375–401. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neumann H., McDonough K. Exploring student interaction during collaborative prewriting discussions and its relationship to L2 writing. J. Sec Lang. Writ. 2015; 27 :84–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicol D., Thomson A., Breslin C. Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: a peer review perspective. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2014; 39 (1):102–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicol D.J., Macfarlane-Dick D. Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Stud. High Educ. 2006; 31 (2):199–218. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nulty D.D. Peer and self-assessment in the first year of university. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2011; 36 (5):493–507. [ Google Scholar ]

- Perron B.E., Sellers J. Book review: a review of the collaborative and sharing aspects of Google Docs. Res. Soc. Work. Pract. 2011; 21 (4):489–490. [ Google Scholar ]

- Petrović J., Pale P., Jeren B. Online formative assessments in a digital signal processing course: effects of feedback type and content difficulty on students learning achievements. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017; 22 (6):3047–3061. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ray P., Singh M. Effective feedback for millennials in new organizations. Human Resource Management International Digest. 2018 [ Google Scholar ]

- Robertson J. The educational affordances of blogs for self-directed learning. Comput. Educ. 2011; 57 (2):1628–1644. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rouhi A., Azizian E. Peer review: is giving corrective feedback better than receiving it in L2 writing? Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2013; 93 :1349–1354. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shvidko E. Beyond “giver-receiver” relationships: facilitating an interactive revision process. Journal of Response to Writing. 2015; 1 (2):4. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/journalrw/vol1/iss2/4 [ Google Scholar ]

- Strijbos J.W., Wichmann A. Promoting learning by leveraging the collaborative nature of formative peer assessment with instructional scaffolds. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018; 33 (1):1–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sung Y.T., Liao C.N., Chang T.H., Chen C.L., Chang K.E. The effect of online summary assessment and feedback system on the summary writing on 6th graders: the LSA-based technique. Comput. Educ. 2016; 95 :1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tai J., Ajjawi R., Boud D., Dawson P., Panadero E. Developing evaluative judgement: enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. High Educ. 2018; 76 (3):467–481. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tempelaar D.T., Rienties B., Giesbers B. In search for the most informative data for feedback generation: learning analytics in a data-rich context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015; 47 :157–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tseng S.C., Tsai C.C. On-line peer assessment and the role of the peer feedback: a study of high school computer course. Comput. Educ. 2007; 49 (4):1161–1174. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang D., Olson J.S., Zhang J., Nguyen T., Olson G.M. Proceedings of the 33rd Annu al ACM Conference On Human Factors In Computing Systems . 2015. DocuViz: visualizing collaborative writing; pp. 1865–1874. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y.C. Promoting collaborative writing through wikis: a new approach for advancing innovative and active learning in an ESP context. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2015; 28 (6):499–512. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wu Y., Schunn C.D. From feedback to revisions: effects of feedback features and perceptions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020; 60 [ Google Scholar ]

- Yen Y.C., Hou H.T., Chang K.E. Applying role-playing strategy to enhance learners’ writing and speaking skills in EFL courses using Facebook and Skype as learning tools: a case study in Taiwan. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2015; 28 (5):383–406. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yim S., Wang D., Olson J., Vu V., Warschauer M. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing. 2017. Synchronous collaborative writing in the classroom: undergraduates' collaboration practices and their impact on writing style, quality, and quantity; pp. 468–479. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Z.V., Hyland K. Student engagement with teacher and automated feedback on L2 writing. Assess. Writ. 2018; 36 :90–102. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang H., Southam A., Fanguy M., Costley J. Understanding how embedded peer comments affect student quiz scores, academic writing and lecture note-taking accuracy. Interactive Technology and Smart Education; 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhou J. Exploring the factors affecting learners’ continuance intention of MOOCs for online collaborative learning: an extended ECM perspective. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2017; 33 (5) [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhu Q., Carless D. Dialogue within peer feedback processes: clarification and negotiation of meaning. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2018; 37 (4):883–897. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhu X., Liu J. Education in and after Covid-19: immediate responses and long-term visions. Postdigital Science and Education. 2020; 2 (3):695–699. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mission Statement

- Editorial Staff

- Subscribe to Our Newsletter

The Truth about Peer Editing

Peer editing is a common part of the curriculum for writing students, but does it actually teach the students anything? Studies say yes.

If you’ve taken a writing class, especially at the university level, you’re probably familiar with the concept of peer editing. You and a classmate swap pieces and edit one another’s work. Peer editing happens all the time, but does it actually help? Does peer editing improve students’ writing skills? Does it boost their editing skills? According to Jessica Holt , a professor at the University of Georgia, the answer seems to be yes.

THE RESEARCH

In Holt’s article “ Grade-Accountable Peer Editing: Students’ Perceptions of Peer-Editing Assignments ,” she describes research on how university-level communications students perceive the peer-editing process. In the study, students in two communications classes were given several peer-editing assignments throughout the semester.

At the conclusion of the semester, the students participated in focus groups to discuss their perceptions about the peer-editing process. Holt discovered that the students overwhelmingly perceived peer editing to be helpful but unpleasant and that many students didn’t believe peer-editing skills would be relevant after entering the workforce. One student stated, “I think that peer editing can be good, but in all honesty, I would rather have a teacher edit my paper or like my boss or whoever the end-all, be-all person is.”

“Peer review has been shown to promote the recognition of good practice as well as critical and constructive collaborative dialogue.” —Jennifer brill and charles hodges (2011)

THE IMPLICATIONS

Though university students in writing-heavy disciplines may believe that peer reviewing is just a classroom tactic, peer review can be much more than that. Holt’s and others’ research shows that learning to effectively edit peers’ work can help individuals improve their ability to edit, including in the workplace. For example, Jennifer Brill and Charles Hodges noted in the article “ Investigating Peer Review as an Intentional Learning Strategy to Foster Collaborative Knowledge-Building in Students of Instructional Design ” that “peer review has been shown to promote the recognition of good practice as well as critical and constructive collaborative dialogue.” Peer review is also a great way to sharpen writing and communication skills. Giving feedback and receiving feedback are skills that all writers and editors can benefit from and, like other skills, require practice to develop. One way to practice is through peer review.

To learn more about the benefits of peer editing, read the full article:

Holt, Jessica. (2019). “Grade-Accountable Peer Editing: Students’ Perceptions of Peer-Editing Assignments.” Journalism & Mass Communication Educator 74 (1): 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695818764959 .

—Erin Johnston, Editing Research

FEATURE IMAGE BY IVAN SAMKOV

Find more research

Read Pantelis Papadopoulos, Thomas Lagkas, and Stavros Demitriadis’s (2012) article on different methods to make peer reviewing as effective as possible: “How to Improve the Peer Review Method: Free-Selection vs. Assigned-Pair Protocol Evaluated in a Computer Networking Course.” Computers & Education 59 (2): 182–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.005 .

Check out Lloyd Rieber’s article on how peer editing can help students in business disciplines: Rieber, Lloyd J. (2012). “Using Peer Review to Improve Student Writing in Business Courses.” Journal of Education for Business 81 (6): 322–26. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.6.322-326 .

Related Posts

What News Editing Can Teach Us about Editing

Bigger Isn’t Always Better: Publish with Independent Publishers

Unbalancing Act: When Fiction Normalizes Unhealthy Romance

Erin Johnston

Had so much fun doing this research.

As someone who hasn’t always enjoyed the peer-editing process, I liked being able to see how it would be relevant to life outside of the classroom. Writing doesn’t end when we graduate, so it makes sense that peer editing wouldn’t end either.

I definitely agree! We can all benefit from each other’s perspectives, no matter how experienced we are.

Peer Editing to the Rescue! - Editing Research

[…] Take a look at Erin Johnston’s Editing Research article for more information on peer editing: “The Truth about Peer Editing.” […]

Leave a Reply Cancel

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- About NuWrite

- Writing Advice

- Engineering & Design

- General writing advice

- Academic integrity and avoiding plagiarism (Northwestern WCAS)

- Grammar and punctuation

- Analytical writing

- Research papers

- Graphics and visuals

- Conferences

- Peer editing sheets for drafts

- Peer feedback form literature seminar

- Peer review Asian diaspora freshman seminar

- Research draft peer review

- Research paper introduction peer response

- Research paper peer evaluation of claims

- Peer editing science papers

- Getting the most out of peer reviews

- Peer review guidelines for a personal essay

- Writing assignments

- Freshman seminar award essays

- Useful links with writing advice

- Grading criteria

- Global Health

- Writing in the Humanities

- Science Writing

- Social Science Writing

- Writing for Graduate or Professional School

- Writing Advice for International Students

- Faculty-Only Resources

Peer editing

Peer editing can be done during class time or electronically outside of class, as the documents below--from Northwestern instructors--illustrate. The questions that students respond to can vary according to the nature of the assignment and the purpose of the peer review.

peer editing sheets for drafts Peer editing sheets for two essay assignments in a freshman seminar. Providing very specific questions helps the editors give useful feedback and suggestions.

peer feedback form literature seminar Students exchange drafts in class, complete the peer feedback form, and then discuss their written comments with one another. Students submit the forms with their drafts so that I can read them. I frequently refer to their peers' comments when I am writing my own comments on their drafts.

peer review Asian diaspora freshman seminar Students do a close reading of one another's drafts to provide insight into what has and has not been conveyed by the draft.

research draft peer review Prompts peer reviewers to comment on key pieces of information, logical organization, and conclusion

research paper introduction peer response Prompts peer editor to comment on introduction, and prompts author to respond to those comments

research paper peer evaluation of claims Prompts peer editor to evaluate the paper's effectiveness in supporting claims and addressing counter-arguments

peer editing science papers Prompts peer editor to complete a checklist on the paper's content, structure, and grammar

getting the most out of peer reviews A link to NU's Writing Place that explains how to make sure you benefit from sharing your writing with peers

peer review guidelines for a personal essay These guidelines from a freshman seminar are aimed at pairs of students who are exchanging drafts before meeting individually with the instructor.

- Contact Northwestern University

- Campus Emergency Information

- University Policies

Northwestern University Library | 1970 Campus Drive, Evanston, IL 60208-2300 | Phone: 847.491.7658 | Fax: 847.491.8306 | Email: [email protected]

Lend Me Your Peers: How to Make the Most of Peer Editing Sessions

September 1, 2017

By Andrew Koch, Writing Tutor

"And be sure to bring a draft of your paper for next week's class. We're having a peer review day."

(Internal groan)

Peer editing days are like Cincinnati weather: either great or miserable, with not much in between. The right suggestions from classmates about your writing can give you great insights on how to improve your paper, but if you're anything like me, you find bad peer editing can be a real drag.

Bad peer editing comes in many forms, from the hypercritical (red ink dripping from every line) to the unresponsive (a blank expression and a shrug when you ask "So what'd you think?"), and the worst peer editing can make you feel worse about your paper than when you began the session. Many professors have students critique others' works as a way of improving writing, but misguided peer review sessions can turn into time spent either politely nodding and discussing weekend plans and last night's game or (worse) passive-aggressively tearing each other's papers apart. Sometimes a student may not know what kind of advice to give to a classmate, especially if he or she is personally struggling to understand the assignment.

But you don't have to settle for anything less than the best from these sessions! As is the case in many areas in life, you'll get what you give from peer editing. By committing to being a better peer editor, you're helping to improve the peer editing culture and showing your classmate what kind of feedback you're looking for in return. By learning the right questions to ask, your partner and you can both walk away with a better paper and more confidence about the assignment. Here are some ways to help you get the most out of peer editing sessions:

Look at the big picture. A common mistake among editors is putting too much focus on "proofreading" and not enough on the content of a paper. Though it pains me (a grammar nerd) to admit it, good peer editing is about a lot more than policing spelling and punctuation. Rather, good peer editing ensures that a piece of writing, in addition to being grammatically correct, makes sense to the audience and is accomplishing what the assignment asks. Don't be afraid to ask more general questions about the paper and its structure and focus. Is the writer's focus too broad? Too specific? In an argumentative paper, is the writer's main opinion coming through? Are there ways that the writer could be clearer? Does your partner's paper fulfill the assignment's requirements in terms of focus?

Listen to the writer and let him/her guide. See if there's a specific aspect of the paper that your partner is concerned about. While some of your fellow students might not know what they want to improve about their writing/assignment, others will more precisely know how they want to better develop the paper. As a peer editor, your goal is to help the other student improve his or her assignment and writing ability, whatever shape that may take, and your classmate will do the same for you. As tempting as it might seem, this is not a chance for you to show off your intelligence or writing prowess. Remember to stay focused on what your review session partner needs and follow his or her lead.

Read the paper out loud. If you've been to the Writing Center, you're probably familiar with this technique, one of our favorites. It's easy to become bogged down in your own words while writing a piece, but verbally revisiting your words by doing a read through can help you catch content weaknesses and, yes, spelling and grammar mistakes, too, by revisiting your language in a new way. Time permitting, have your partner read his or her paper aloud to you.

Ask questions and be patient. If you're unsure about something in your partner's paper, just ask! Writers love to talk about their writing, and face-to-face communication allows you the opportunity to quickly and efficiently ask questions and get feedback. Don't assume that you understand what a writer is saying - feel free to pick your partner's brain about his or her subject or topic. I've often found that my best ideas come when I'm explaining my paper's subject or my writing assignment to someone else.

Being a better peer editor for someone else can help you focus on your own writing as well. By being a more thoughtful peer editor, you can break the cycle of unproductive and unhelpful peer editing sessions, and everybody will win.

You might also like:

A little catch up on catching up, the future of sport: writing, feedback shouldn’t be the enemy.

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

278k Accesses

15 Citations

714 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

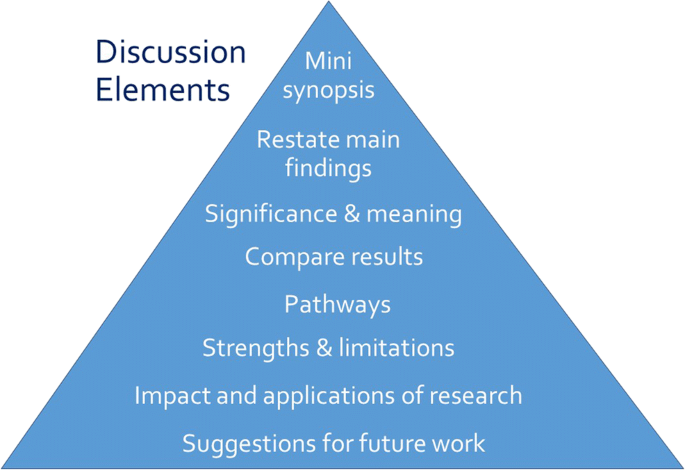

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

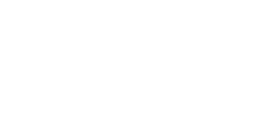

Structure of the Introduction Section