- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2024

Prevalence of intimate partner violence among Indian women and their determinants: a cross-sectional study from national family health survey – 5

- Sayantani Manna ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9093-1172 1 na1 ,

- Damini Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3574-4398 1 na1 ,

- Manish Barik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7582-1047 1 ,

- Tanveer Rehman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2377-4394 1 ,

- Shishirendu Ghosal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1833-3703 1 ,

- Srikanta Kanungo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5647-0122 1 &

- Sanghamitra Pati ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7717-5592 1

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 363 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1628 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) can be described as a violation of human rights that results from gender inequality. It has arisen as a contemporary issue in societies from both developing and industrialized countries and an impediment to long-term development. This study evaluates the prevalence of IPV and its variants among the empowerment status of women and identify the associated sociodemographic parameters, linked to IPV.

This study is based on data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) of India, 2019-21 a nationwide survey that provides scientific data on health and family welfare. Prevalence of IPV were estimated among variouss social and demographic strata. Pearson chi-square test was used to estimate the strength of association between each possible covariate and IPV. Significantly associated covariates (from univariate logistic regression) were further analyzed through separate bivariate logistic models for each of the components of IPV, viz-a-viz sexual, emotional, physical and severe violence of the partners.

The prevalence of IPV among empowered women was found to be 26.21%. Among those who had experienced IPV, two-thirds (60%) were faced the physical violence. When compared to highly empowered women, less empowered women were 74% more likely to face emotional abuse. Alcohol consumption by a partner was established to be attributing immensely for any kind of violence, including sexual violence [AOR: 3.28 (2.83–3.81)].

Conclusions

Our research found that less empowered women experience all forms of IPV compared to more empowered women. More efforts should to taken by government and other stakeholders to promote women empowerment by improving education, autonomy and decision-making ability.

Peer Review reports

Domestic violence is one of the emerging problems in recent years in both low- and middle-income as well as high-income countries. Gender-based violence, another leading public health problem identified in 1996, is a matter of human rights rooted in gender inequality [ 1 ]. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) from 2015, also recognized the importance of gender-based violence, which is an advance step to eliminate gender inequality and women empowerment [ 2 , 3 ]. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is recognized as the most common gender-based violence, which is mostly used as synonymously as domestic or spousal violence but conceptually a subtle difference is present [ 4 ]. IPV affect general health and reproductive health of women, causing chronic pain, injuries, fractures, disabilities, unwanted pregnancy and over expose to contraceptive pills, increasing vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases [ 5 ]. Such physical and mental strains gradually bring about in the form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, phobia, depression, alcohol abuse etc [ 6 ].

IPV has become a global public health problem with the consequences of premature deaths and injuries [ 7 ]. World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized IPV as a “global hidden epidemic” [ 8 , 9 ]. Worldwide, one-third of the women have experienced IPV [ 3 ]. Due to stigma and fear Intimate Partner violence (IPV) on married women remain unreported in India [ 10 ]. IPV has been recognized as a criminal offence under Indian Penal Code 498-A since 1983. Victims are offered civil protection under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA) 2005, which covers all forms of physical, mental, verbal, sexual and economic violence (unlawful dowry demands), including marital rape and harassment etc [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. According to the National Crime Record Bureau’s report, the rate of total crime per lakh ( per lakh defined in the Indian numbering system as equal to one hundred thousand) in the women population is 56.5 [ 14 ].

Evidence suggests IPV is associated with low socioeconomic status and unemployment. Indian-employed women faced IPV at a lower rate [ 15 ], while other researchers have identified it as an increased risk of violence [ 16 ]. Other studies illustrated little consistency between women empowerment and violence across varying cultures, where educational attainment, income, decision-making, and contextual factors all play vital roles individually [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. On the contrary empowered women and following economic independence act as a shield to domestic violence in high-income countries [ 20 ]. Consequently, women’s empowerment would continue to be perceived as a “zero-sum” game with politically robust beneficiaries and weak losers if it was advocated as a goal in and off itself [ 22 ]. There may be present specific association and management techniques for each sort of IPV which must thus be researched independently [ 15 ]. Hence, in this study, we estimated the prevalence of different IPV categories against empowerment status of women and determined the sociodemographic behaviour associated with IPV.

Overview of data

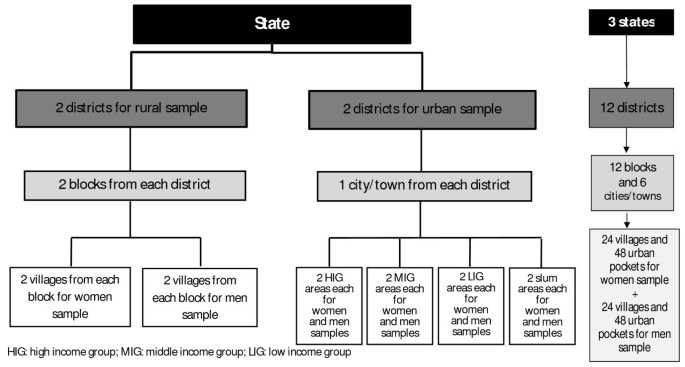

India is home for more than 1.4 billion population, making this country the second-most populous country in the world [ 23 ]. The National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5), which was conducted in all 28 states and 8 union territories of the country, is representative at the national and state/UT levels, adopted in each survey round. A two-stage sampling was done to choose villages and census enumeration blocks from districts in rural and urban regions, respectively. From June 2019 to April 2021, data were collected using CAPI. (Computer-Assisted Personal Interview) with an internal scheduling and adequate maintenance of respondent anonymity. The NFHS-5 methodology has been extensively explained and published elsewhere, including the methods for choosing households and data collection [ 24 ].

Study population and study design

The design for this research is comparable to a cross-sectional study because the secondary data used here is collected during the two phases of NFHS-5: from June 17, 2019, to January 30, 2020, and from January 2, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Women who lived with their spouses or partners and experienced any event of domestic abuse, ever till the day of the interview, were included. The included observations were then the subject of secondary data analysis.

Sample size

Among the 724,115 women interviewed during the NFHS-5, information was acquired from “never-married” or “ever-married” women aged 18–49 years on their experience of violence committed by their present and previous spouses. Only participants who lived with a partner (married or unmarried) were included in this study ( Fig. 1 ) . As a result, 68,949 women formed the ultimate sample size.

Flow diagram of sample selection from the women’s questionnaire of the NFHS-5

Independent variables

The current study focused on the sociodemographic covariates like age, residence (rural/urban), caste, respondent educational qualification, partner’s educational qualification, religion (four categories: Hindu, Muslim, Christian and other religions), wealth index (five quintiles: poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest quintile), and women empowerment (three categories: low, medium and high ). Another two sets of covariates were the partner’s habit of alcohol consumption and partner controlling behaviour, both dichotomous, grouped as ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Levels of women’s empowerment were assessed using three indicators: (1) women’s decision-making ability for the household (including access to healthcare, household purchasing and freedom to visit relatives, spending husband earnings, beating wife refuse to have sex), (2) beating indicators(beating the child, wife when argues or refuse to have sex etc.) (3)controlling indicators (includes if allowed to go to market, health facility, outside the village, is justified if went outside without telling), and (4) five economic indicators explaining ownership of the land, house, working status, having a bank account and if owns a mobile phone. All the selected variables are coded into binary variables 0 and 1. Binary variables were included in the composite index to guarantee consistency, while ordinal variables were recoded into binary variables. Table A1 in the supplementary file describes the final variables and their recorded values.

During principal component analysis (PCA), scree plots were examined to determine the number of components to be retained. The scree plot shows that only five components’ eigenvalue is more than 1, which were further processed [ 4 , 19 , 25 ]. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy (greater than 0.04 in the PCA) analysis indicates that the sample sizes in this study were appropriate for PCA (Table A2 in the supplementary file). For all components, Bartlett’s test of sphericity confirms that the selected markers of women’s empowerment were intercorrelated. Furthermore, the reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha score:0.60–0.79) demonstrates an adequate component correlation level. We utilized the first component only after loadings and computing component scores, and the index scores were then divided into quintiles (low, medium, and high). Finally, for each selected nation, an overall index of women’s empowerment was built with three ordered categories: low, medium, and high, where ‘low’ indicated women had lower employment and ‘high’ meant women had more empowerment.

Outcome characteristics: intimate partner violence status

In NFHS-5, a series of questions were asked to collect information on violence committed by the partners, including husbands. It also examines four types of violence faced by women: physical, sexual, emotional, and severe. The level of violence was determined by asking all “ever-married” women if their husbands had ever done the following to them:

- Physical violence

The IPVs which include any physical violence inflicted on a woman by her husband/partner, which provides for: (a) ever slapped; (b) arm twisted /hair pulled; (c) pushed, shaken/had something thrown at them; (d) punched with a fist or hit by something harmful; (e) kicked/dragged; (f) strangled /brunt; (g) threatened with any weapon.

- Sexual violence

The Sexual IPVs were captured by three questions in the dataset: (a) physically forced to have sexual intercourse; (b) physically forced to perform any other sexual acts (c) forced you with threats / in any other way to perform sexual acts.

Emotional violence

Emotional violence recorded by these questions (a) ever having been said /done something to humiliate you in front of others, b) threatened to hurt /harm you or someone close to you, c) insulted you/make you feel bad about yourself.

Severe violence

Severe violence includes physical acts like beatings, choking, burning, and using weapons, as well as sexual violence [ 5 , 26 ]. NFHS-5 asks specific questions to gather this information are a) ever bruises, b) eye injuries, sprains, dislocations or burns, c) severe burns, d) wounds, broken bones, broken teeth or others.

The answer was classified as “never” if the response was “frequently”, “occasionally”, or “yes but not in the previous 12 months”. Except for ‘never,’ all responses to questions on IPVs indicated prior exposure to physical, sexual, emotional, or serious violence. For simplicity, all responses except ‘never’ were coded as Yes = 1 but never as No = 0.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in STATA v17.0 (Stata Corp., Texas). The Fig. 2 below presents a conceptual framework for predicting the socioeconomic determinants of IPV in India. Using this framework, IPV can be characterized as a function of the individual, household, and community variables (Fig. 2 ) . We also analyzed weighted profiles of various IPVs among the sociodemographic and expressed them in numbers and proportions. Distribution of the number of IPV among other categorical was presented as frequencies and association in p-value (< 0.002). To account for the complex survey design, we utilized the domestic violence weighting variable (d005) provided in the NFHS data and applied the survey command (svy), which enabled us to weight the data accurately.

For each independent variable, we performed univariate analysis (Table A3 ) and incorporated the variables with significant p-values to the multivariable logistic regression model. To assess the appropriateness of the model fit, we utilized two statistical tests: the AIC BIC test and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The diminishing values of AIC and BIC suggest that the model is well-suited for the analysis. Moreover, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded a p-value of > 0.05, which reinforces our conclusion that the model is a suitable fit for this analysis. These preliminary models aimed to establish whether any factors should not be regarded as potential covariates for IPV in the multivariate analysis.

Conceptual framework for the determinants of intimate partner violence

Among the 68,949 women in the study, 26.21% (18,074) experienced intimate partner abuse. Most of them belonged to > 35 years of age (40%), and 46% of women completed secondary-level education [Table A3 (Supplementary file)]. Among 26.21% of women who faced any kind of violence, 60% (11,679) experienced physical violence, 23.87% (4,314) were physically injured due to severe IPV, 2.15% experienced sexual violence, and 9.54% experienced emotional violence (Fig. 3 ).

Distribution of various form of IPV among Indian women

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic profile, which is further classified by the type of violence experienced. A prevalence of 28.39%, among women aged > 35 years was observed for IPV from their partner. In rural areas have the higher incidence of physical IPV at 26%, compared to urban areas. Women belongs to SC caste had the experienced the highest prevalence of IPV. Women with no formal education (39.03%) and less empowered (37.81%) were the most vulnerable to violence. Similarly, 35% of women who didn’t have any formal education had experienced physical abuse by their partner. When the partner is highly educated, IPV was 19% compared to no formal education (41.60%). IPV was almost equally prevalent among Hinduism (27%) and Muslim women (25%) [physical violence (Hindu: 24.40%; Muslim: 21.31%); emotional violence (Hindu: 11.61%; Muslim: 10.94%)]. In the southern region of India, 30% of women have reported experiencing violence.

The distribution of sampled women based on their background characteristics has been presented in Table A4 . The chi-square test is used to assess the strength of association between each socioeconomic variable, and the p-values are provided in the last column of Table A4 . Multivariate regression (Table 2 ) showed a higher chance of experiencing severe IPV among the 25–35 years age-group than the 35–49 years age group with AOR 2.18 (95%CI: 1.69–2.80) in comparison with 15–24 years age group. Respondents who didn’t have any formal education had higher likelihood [AOR = 1.65 (95% CI = 1.35–2.02)] of facing physical violence than women having more than secondary education. Partners with no formal education were significantly associated with any form of violence compared to the highly educated partners. There was 52% greater likelihood among the less empowered women of facing more emotional violence than the highly empowered women. Less empowered women had a significant odd of experiencing sexual violence [AOR:1.92(1.59–2.31)] than that highly empowered women. Relatively higher odds of physical violence were evident from southern [AOR: 2.10 (1.82–2.42)] and eastern [AOR: 1.75(1.51–2.02)] regions, however, sexual violence was highly associated with western [AOR: 1.21 (0.92–1.59)] part of India. Partner’s alcohol drinking was found to be an attributing factor for any form of violence, i.e., emotional violence [AOR: 2.34 (2.09–2.63)], physical violence[AOR: 2.76 (2.52–3.03)] sexual violence [AOR: 3.31 (2.83–3.88)] or severe violence [AOR: 3.38 (2.94–3.89)]. Partner controlling behaviour also evolved as a determining factor for any violence, i.e., emotional violence [AOR:6.63(5.87–7.47)], Physical violence [AOR:3.62(3.33–3.94)] and sexual violence [AOR:6.60(5.53–7.88)].

Our analysis showed a statistically significant increase in physical violence, particularly among women who were less empowered. At the individual level, it has been shown that women are less likely to experience IPV when they are more educated, higher income status, and are empowered. Household-level factors demonstrated that they had significance in intimate partner violence as well as the community-level factors showed the same (i.e., husband’s education, controlling behaviour and drinking Alcohol).

The results of this study demonstrate that a few individual factors strongly explain IPV. For instance, young women who belong to a scheduled caste, being from lower income group and with less level educationwere more likely to experience spousal violence. Previous evidence supported that higher prevalence of IPV is observed among women from Schdule Tribe and Schdeduled Caste [ 27 , 28 ]. Being from lower socioeconomic status also found to be elevating the risk of IPV in women. The literature with the similar evidence confirm that the women from marginal poor segment of society [ 29 , 30 , 31 ] .

Significantly, the more alcohol is consumed, the more nuanced the association between the variables of women empowerment become. According to the findings of this study, women who indicate that their husbands frequently or occasionally consume alcohol have a higher likelihood of experiencing all types of IPV than empowered women who report their husbands never consume alcohol [ 33 , 34 ].

Working women with higher education, on the other hand, experienced higher IPV exposures as compared to their non-working counterparts. The ego considerations of the spouses and gender prejudices in Indian society are likely reasons for any kind of violence [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. This public health challenge can be addressed by enhancing economic empowerment there by could providing women the awareness and a platform for protest. Given that different levels of social ecology influence spousal violence, interventions at a higher level may be more effective in challenging spousal violence social norms rather than focusing on individual factors, which are difficult to change at the population level and may take decades or generations to be effective.

Strength & limitation

This study used nationally representative data to understand the prevalence of intimate partner violence. It creates an aggregated index of women’s empowerment, providing a more comprehensive view of its relationship with IPV. The NFHS collects a large data set from a representative sample of the country and hence gives a good estimate of marital violence and its relationships with explanatory factors at the population level. However, one of the key drawbacks was its dependence on women’s self-reporting of partner violence. Spousal violence is delicate and intimate in nature, and it is difficult for women to divulge during major survey data collecting due to recall bias and fear of stigmatisation. Further, we were unable to validate the direction of causation and the causative mechanism of domestic and Intimate Partner violence in India using this cross-sectional data. In addition, our composite measure of women’s empowerment index was not strong by conventional statistical standards.

Finally, the implications of the findings are constrained because the data supplied only allowed for the examination of heterosexual relationships [ 39 ]. It should be emphasized, however, that monogamous heterosexual partnerships are the norm in India, signifying a larger reach in terms of generalizability.

Implication

This study has numerous significant policy consequences. This study provides recent evidence for understanding the underlying factors of IPV in India, where wife-beating is high, women’s decision-making power is limited, and male-dominated cultures prevail across the country, though to varying degrees from rigid gender norms. Women’s empowerment, which in turn could ease the risk of IPV and domestic violence, may be enhanced by economic interventions such as conditional cash transfers gender sensitization workshops, media, and cultural campaigns and microcredit programs [ 40 ].

The findings of this study highlight the need to enhance girls’ education, increasing women empowerment, equity in society by eliminating harmful socio-cultural practises. Nevertheless, sole reliance on economic empowerment falls short in ensuring the comprehensive protection of women. Interventions aimed at empowering women must engage with couples as units and operate at the community level, addressing issues of equal job opportunities and gender-specific roles to be effective.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) repository (with proper permission), Available at: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset/India_Standard-DHS_2020.cfm?flag=0 .

Abbreviations

National family health survey

Ministry of health and family welfare

Union territory

- Intimate partner violence

Sustainable development goals

Principal component analysis

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval

World health organization

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Demographic health survey

Computer-assisted personal interview

Gender-based violence against. women and girls | OHCHR n.d. https://www.ohchr.org/en/women/gender-based-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed February 21, 2023).

Understanding. and Addressing violence against women. n.d.

World Health Organization. Violence against Women [Internet]. www.who.int. 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women#:~:text=Estimates%20published%20by%20WHO%20indicate

Parekh A, Tagat A, Kapoor H, Nadkarni A. The effects of husbands’ alcohol consumption and women’s empowerment on intimate Partner violence in India. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP11066–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521991304 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

García-Moreno C, World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, South African Medical Research Council. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. n.d.

Malik M, Munir N, Usman Ghani M, Ahmad N. Domestic violence and its relationship with depression, anxiety and quality of life: a hidden dilemma of Pakistani women. Pak J Med Sci. 2021;37:191. https://doi.org/10.12669/PJMS.37.1.2893 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sabri B, Renner LM, Stockman JK, Mittal M, Decker MR. Risk factors for severe intimate Partner violence and violence-related injuries among women in India. Women Health. 2014;54:281–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2014.896445 .

Hidden Epidemic? A. A Hidden Epidemic? A Hidden Epidemic? A Hidden Epidemic? A Hidden Epidemic? 2006.

Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8 .

Gajmer P, Tyagi S. Domestic violence: an overview of Sec 498A IPC- a case report. Indian J Forensic Community Med. 2021;8:55–7. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijfcm.2021.011 .

Article Google Scholar

Mondal D, Paul P. Associations of Power relations, wife-beating attitudes, and Controlling Behavior of Husband with Domestic Violence Against women in India: insights from the National Family Health Survey–4. Violence against Women. 2021;27:2530–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220978794 .

National family health survey (NFHS. -4) 2015-16 INDIA. 2017.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. 2017. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS.

Crime in. India 2020 National Crime Records Bureau. n.d.

Garg P, Das M, Goyal LD, Verma M. Trends and correlates of intimate partner violence experienced by ever-married women of India: results from National Family Health Survey round III and IV. BMC Public Health. 2021;21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12028-5 .

Haobijam S, Singh KA. Socioeconomic determinants of domestic violence in Northeast India: evidence from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4). J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP13162–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211005133 .

Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, Devries K, Kiss L, Ellsberg M, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO Multi-country Study on women’s Health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-109 .

Hindin MJ. Intimate Partner Violence among Couples in 10 DHS Countries: Predictors and Health Outcomes [AS18]. 2008.

Rowan K, Mumford E, Clark CJ. Is women’s empowerment Associated with help-seeking for Spousal Violence in India? J Interpers Violence. 2018;33:1519–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515618945 .

Dalal K. Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? J Inj Violence Res. 2011;3:35–44. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76 .

Kabeer N, Resources. Agency, Achievements: Re¯ections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. n.d.

Mind the gap [Internet]. Available from: https://cdn.sida.se/publications/files/sida984en-discussing-womens-empowerment---theory-and-practice.pdf.

India Overview. Development news, research, data | World Bank n.d. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/overview (accessed April 28, 2024).

Release of NFHS-5. (2019-21) - Compendium of Factsheets | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | GOI n.d. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/basicpage-14 (accessed August 24, 2022).

Anik AI, Islam MR, Rahman MS. Do women’s empowerment and socioeconomic status predict the adequacy of antenatal care? A cross-sectional study in five south Asian countries. BMJ Open. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043940 .

NFHS-5 womans n.d.

Begum S, Donta B, Nair S, Prakasam CP. Sociodemographic factors associated with domestic violence in urban slums, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:783–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-5916.160701 .

Chowdhury S, Singh A, Kasemi N, Chakrabarty M. Decomposing the gap in intimate partner violence between Scheduled Caste and General category women in India: an analysis of NFHS-5 data. SSM Popul Health. 2022;19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101189 .

Ahmad J, Khan N, Mozumdar A. Spousal Violence Against Women in India: A. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:10147–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519881530 . Social–Ecological Analysis Using Data From the National Family Health Survey 2015 to 2016.

Ackerson LK, Subramanian S. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1188–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn049 .

Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S. Challenging assumptions about women’s empowerment: Social and economic resources and domestic violence among young married women in urban South India. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:577–85. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn226 .

Aboagye RG, Ahinkorah BO, Tengan CL, Salifu I, Acheampong HY, Seidu AA. Partner alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence against women in sexual unions in sub-saharan Africa. PLoS ONE. 2022;17. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0278196 .

Aboagye RG, Ahinkorah BO, Tengan CL, Salifu I, Acheampong HY, Seidu AA. Partner alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence against women in sexual unions in sub-Saharan Africa. Salinas-Miranda A, editor. PLOS ONE. 2022 Dec 22;17(12):e0278196.

Tumwesigye NM, Kyomuhendo GB, Greenfield TK, Wanyenze RK. Problem drinking and physical intimate partner violence against women: evidence from a national survey in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-399/TABLES/2 .

Zhu Y, Dalal K, Childhood exposure to domestic violence and attitude towards wife, beating in adult life: a study of men in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2010;42:255–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932009990423 .

Downside of Patriarchal Benevolence. Ambivalence in Addressing Domestic Violence and Socio Economic Considerations for Women of Tamil Nadu, India | Office of Justice Programs n.d. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/downside-patriarchal-benevolence-ambivalence-addressing-domestic (accessed February 9, 2023).

Moonzwe Davis L, Schensul SL, Schensul JJ, Verma RK, Nastasi BK, Singh R. Women’s empowerment and its differential impact on health in low-income communities in Mumbai, India. Global Public Health. 2014 Apr 25;9(5):481–94

Moonzwe Davis L, Schensul SL, Schensul JJ, Verma RK, Nastasi BK, Singh R. Women’s empowerment and its differential impact on health in low-income communities in Mumbai, India. Glob Public Health. 2014;9:481–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.904919 .

Manik Manas G. women empowerment through higher education in India. n.d.

Antai D. Controlling behavior, power relations within intimate relationships and intimate partner physical and sexual violence against women in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2011;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-511 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) for providing the NFHS-5 dataset.

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Sayantani Manna and Damini Singh contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Division of Health Research, ICMR-Regional Medical Research Centre, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India

Sayantani Manna, Damini Singh, Manish Barik, Tanveer Rehman, Shishirendu Ghosal, Srikanta Kanungo & Sanghamitra Pati

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TR, SK and SP conceived the study. TR and SK developed the analytical framework. SM, DS and MB performed the analysis, produced results and drafted manuscript. SK, TR and SG monitored the analysis. All Authors edited the manuscript. SP provided overall guidance and supervised the study.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Srikanta Kanungo or Sanghamitra Pati .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable. The present study utilizes de-identified data from a secondary source.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Manna, S., Singh, D., Barik, M. et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence among Indian women and their determinants: a cross-sectional study from national family health survey – 5. BMC Women's Health 24 , 363 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03204-x

Download citation

Received : 18 October 2023

Accepted : 11 June 2024

Published : 22 June 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03204-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- What is already known on this topic

- What this study adds

- How this study might affect research, practice or policy

- Introduction

- Conflict of Interest statement

- Authors’ contributions

- Ethics approval

- Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

- Data sharing statement

- < Previous

Burden, trend and determinants of various forms of domestic violence among reproductive age-group women in India: findings from nationally representative surveys

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Premkumar Ramasubramani, Yuvaraj Krishnamoorthy, Karthiga Vijayakumar, Rajan Rushender, Burden, trend and determinants of various forms of domestic violence among reproductive age-group women in India: findings from nationally representative surveys, Journal of Public Health , Volume 46, Issue 1, March 2024, Pages e1–e14, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdad178

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Violence, a notable human rights concern, has a public health impact across the globe. The study aimed to determine the prevalence and determinants of domestic violence among ever-married women aged 18–49 years in India.

Secondary data analysis with National Family Health Survey 5, 2019–21 data (NFHS-5) was conducted. The complex sampling design of the survey was accounted-for during analysis. The primary outcome was domestic violence. Prevalence was reported with 95% confidence interval (CI). Prevalence ratio was reported to provide the factors associated with domestic violence using Poisson regression.

About 63 796 ever-married women aged 18–49 years covered under domestic violence module of NFHS-5 survey were included. Prevalence of domestic violence (12 months preceding the survey) was 31.9% (95% CI: 30.9–32.9%). Physical violence (28.3%) was the most common form followed by emotional (14.1%) and sexual violence (6.1%). Women with low education, being employed, husband being uneducated or with coercive behavior had significantly higher prevalence of domestic violence.

One-third of the reproductive age-group women were facing some form of domestic violence. Target group interventions like violence awareness campaigns, women supportive services and stringent law enforcement should be implemented to eliminate domestic violence by year 2030.

- domestic violence

- reproductive physiological process

- sexual assault

- secondary data analysis

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Risk Factor of Domestic Violence in India

Meerambika mahapatro, vinay gupta.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Meerambika Mahapatro, National Institute of Health and Family Welfare, Baba Gang Nath Marg, Munirka, New Delhi - 110 067, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2011 May 20; Accepted 2012 Feb 19.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background:

It is over the last decade that research in this field of domestic violence has led to greater recognition of the issue as public health problem. The paper aims to study the prevalence of physical, psychological, and sexual violence and potential risk factors of the women confronting violence within the home in India.

Materials and Methods:

A multicentric study with analytical cross-sectional design was applied. It covers 18 states in India with 14,507 women respondents. Multistage sampling and probability proportion to size were done.

The result shows that overall 39 per cent of women were abused. Women who have a lower household income, illiterate, belonging to lower caste, and have a partner who drinks/bets, etc. found to be important risk factors and place women in India at a greater risk of experiencing domestic violence.

Conclusion:

As India has already passed a bill against domestic violence, the present results on robustness of the problem will be useful to sensitize the concerned agencies to strictly implement the law. This may lead to more constructive and sustainable response to domestic violence in India for improvement of women health and wellbeing.

Keywords: Domestic violence, education, India, risk factor, zone

Introduction

The ubiquity of domestic violence (DV) can be gauged from the fact that it has been documented in different cultures and societies all over the world. There is growing awareness that DV is a global phenomenon and is a serious issue in developing countries as well.( 1 ) Nevertheless, DV shows particular forms and patterns depending on the local context and recognized as an important public health problem. Despite the range of abuse, it is the most common cause of nonfatal injury to women, who suffer, blame themselves, and choose not to report it. In fact, often rationalize and internalized the abuse by believing that the act was provoked by the women, therefore, justify and accept it as their fate, to continue living with it.( 2 ) The substantial consequence for women's physical, mental, and reproductive health and ultimately the risk of death from DV is also reported to be high, which is committed by a spouse or partner.( 3 – 5 )

The prevalence of DV in India ranges from 6 per cent to 60 per cent,( 6 ) with considerable variation across the states in different settings.( 3 , 7 , 8 ) However, the magnitude, extent, and burden of the problem in the country have not been accounted well, as the reporting to the problem is still inadequate. In India, few community-based microlevel studies( 4 , 9 ) are available, which confine to physical violence but evidence on psychological violence and sexual violence is limited.( 4 ) There is also very limited empirical evidence of its various determinants, outcome, and their relationships.( 10 )

Various studies from South Asian countries on DV have identified a number of associated individual and household level risk factors which shows that certain demographic factors such as age, number of living male children, and living in extended family have an association with DV.( 11 , 12 ) Among the protective factors identified in developing countries are higher socioeconomic status, women's economic independence, quality of marital relationship,( 9 ) and higher levels of education among women.( 13 , 14 ) The risk of spousal violence against women is globally known to be higher among women who are younger, have a lower household income, less educated, belonging to lower caste, nonworking women, partner who drinks/bets, etc.( 4 , 8 ) However, the issue of DV and its underlying social determinants of DV in developing countries remain limited especially in the context of India.

This paper tries to study the prevalence of physical, psychological, and sexual violence and its potential risk factors for women respondents with their background characteristics such as age, religion, caste, education, occupation, and income, and its association. The term DV is used in the article refers to the violence faced by the women from their husband and family members within the marital home. Any form of DV includes physical, psychological, or sexual violence faced by the women.

Materials and Methods

Study design.

It was a multicentre study and the study design was conceived as an analytical cross-sectional study. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used. A population-based approach was applied to find out the association between DV and reproductive health consequences.

Inclusion criteria were the married women in the age group between 15 and 35 years. Exclusion criteria were unmarried, widow, and separated women.

Sampling frame

The study was carried out in all the six zones of India, i.e., Northern, Southern, Eastern, Western, Central, and North East, to have a wider representation. Based on the prevalence rate from NFHS-2,( 2 ) the states with high, medium, and low prevalence of DV were selected. In total, 18 states were randomly selected. Keeping in view of 70:30 ratio of rural and urban population, the samples were distributed accordingly. Multistage sampling strategy was used to attain the required samples. For rural sample, two districts and two blocks were selected randomly. 124 villages were chosen for women participants randomly. For urban sample, district headquarters were considered and three socioeconomic strata were identified as high-, middle-, and low-income groups. To select the married women from urban and rural areas, a systematic sampling procedure was followed for households.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the available study that the bad obstetric outcome of pregnancy was 8 per cent and it was expected that the risk would be double (OR = 2) with women subjected to abuse or violence. Using WinPepi, a total of 14,405 female samples were considered for the study (Alpha = 0.05 and 1-Beta = 0.80), which included a margin of 10 per cent nonresponse. Probability proportion to size was calculated for each state.

Study instrument

The study involved collecting data through semistructured questionnaire. A multiphase process was used to develop these questionnaires to ensure that it was culturally and linguistically appropriate. The questionnaire was prepared initially in English and translated and back translated to ensure semantic and content validity. The translated questionnaires were further reviewed for linguistic reliability and appropriateness by the field investigator.

Data validation and management

The data entry package (Epi 6) and the tabulation plan were sent to each centre to bring uniformity. After receiving the data from six participating centers, data were merged. The data were cleaned and validated using excels double data entry.

Data analysis

The data analysis were done using Epi Info, transport to SPSS to calculate proportion, OR, and multivariate logistic regression. 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI) and a P value of less than 0.05 were considered as the minimum level of significance. Content analysis was done for the qualitative data like Focus Group Discussion (FGD), in-depth interview, and case study, respectively.

Measurements

The factors associated with DV included for the analysis were individual- and community-level variables. Multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression (forward method) was applied to 14,507 cases. The statistically significant (<0.20) variables observed in the univariate analysis were included for multivariate analysis. For logistic regression, these variables were used as categorical variables, except the age which was taken as continuous variable. The final model got stabilized after undergoing 12 iterations. Overall efficiency of the model was found 87 per cent approximately. The most parsimonious model obtained in the multivariate analysis with 14,507 cases of which 13,951 have been included in the analysis and 556 cases were missing.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics, ICMR, New Delhi, and reviewed by senior staff for cultural appropriateness. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, participation was entirely voluntary and confidentiality assured.

The study data revealed that DV was very much prevalent irrespective of rural-urban differentials in the country. On the whole, 39 per cent of the women have mentioned about the incidence of one or the other forms of DV in all the six zones. However, overall 37 per cent of the women indicated prevalence of psychological violence, about 14 per cent of physical and sexual violence in their homes, respectively.

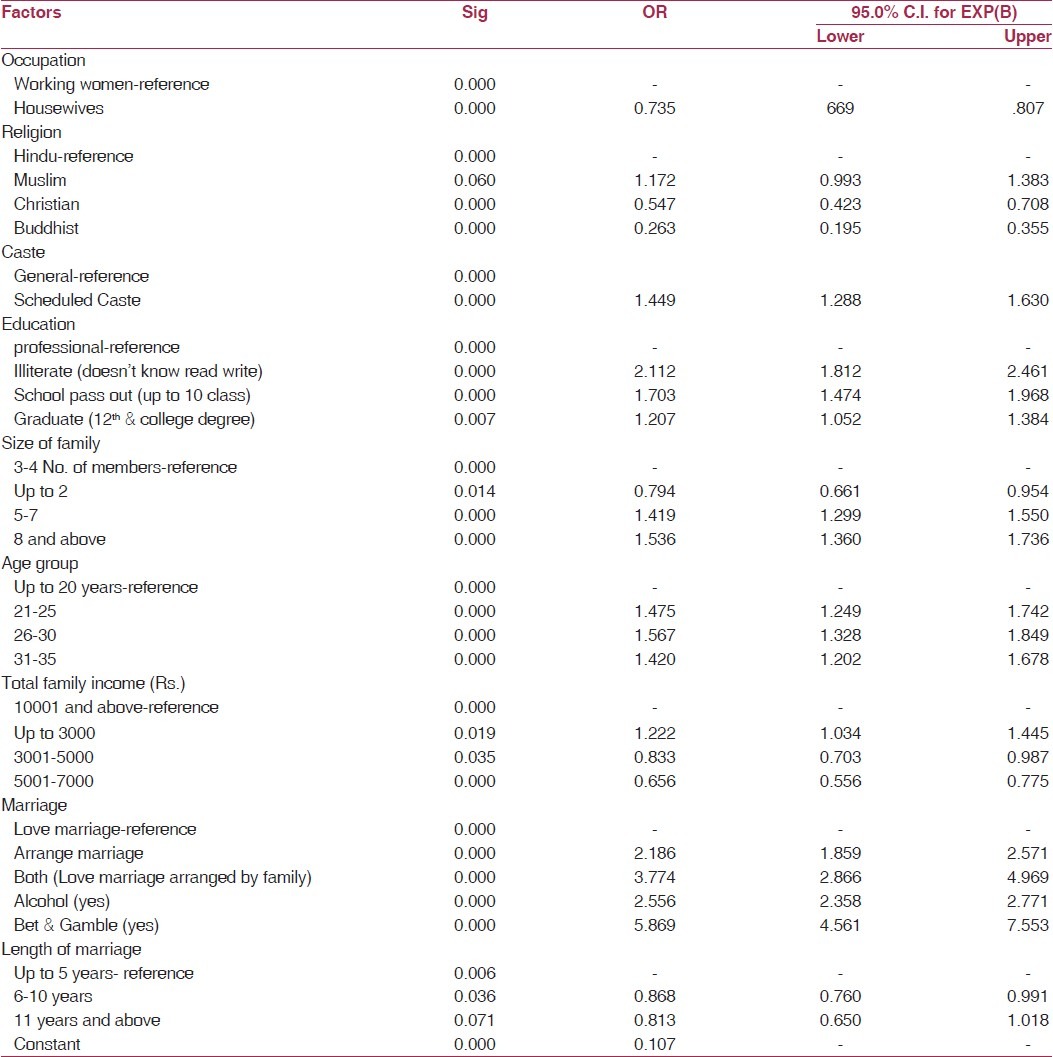

Risk factors of DV

The potential risk factors associated with DV reported by the respondents are discussed using multivariate logistic regression analysis [ Table 1 ].

Binary logistic regression: Risk factors of domestic violence

It is evident that women in the age group between 21 to 35 years were significantly at one time risk of facing DV compared to the women belonged to less than 20 years of age. However, there was a slight decline after 30 years and above age group, which was quite expected as women of higher age group were bound to reduce violence with the passage of time by virtue of their position betters with having adult sons in the family.

The data revealed that women belonged to Muslim religion were at more risk of facing any form of DV compared to women belonged to Hindu religion. While women belonged to Christianity and Buddhism were at no risk, depicting the religion being the protective factor.

The analysis reveals that the infliction of physical as well as psychological and sexual violence was most prevalent among lower caste women who were significantly at greater risk of facing any form of DV compared to upper caste groups.

The data reveal from the regression model that illiterate women were two times significantly at risk of DV (OR = 2.112, CI = 1.812–2.461), whereas women who have completed up to 10 years of schooling (OR = 1.703, CI = 1.474–1.968) and graduation or higher education (OR = 1.207, CI = 1.052–1.384) were significantly one time at higher risk for injury from DV, respectively, compared to the women having professional degree. Though violence decreases with increase of education, the magnitude of DV was considerably high among women with higher literacy also.

The occupation of the participant was recorded and the responses were categorized into i) working women, those contributed to the household income in terms of cash may be engaged in small businesses, daily-waged skilled and unskilled laborers, etc., and ii) house wife. Out of the total women working in different sectors, 49 per cent were facing DV compared to the housewives (36 per cent). In contrast, women who contributed financially none (the house wives) than women whose earnings contributed more to covering their household's expenses were significantly (OR = 0.735, CI = 0.669–0.807) less at risk for DV. Across all the zones, prevalence of DV was higher among the working women compared to the homemakers which were quite contrary to the expected norm. Intraoccupational comparison reveals that women working as nonskilled laborer were facing more DV than the working women of other sector.

Family income

The income of the respondents is indicated by the household's net income per month. The income details were collected in Indian Rupees (INR). The association of family income and DV was found to be highly significant. Women fell in the category of monthly income up to Rs. 3000 were at one time risk of DV compared to women in the family income of Rs. 3001-Rs. 5000 and above.

Size of the family

The association of size of the family and DV was found to be highly significant as women belonged to the family size of the 5–7 members and more than 8 members had one time risk of facing DV, respectively, than the women belonging to the smaller family size of 2 and 3–4 family members, respectively.

Type and length of the marriage

The marriage was categorized in three types namely, arranged marriage, love marriage, and mix marriage, which was love marriage settled by elders. The proportion of the women who reported experiencing DV was significantly two times higher among the women with arranged marriage and three times higher among the women with mixed marriage, respectively, than among women with love marriages. The result shows that any form of DV decreased as the space of marital life increased.

Alcohol consumption

It is evident from the regression model that the prevalence of DV was significantly two times more where husband was found alcoholic (OR = 2.556, CI = 2.358–2.771) as compared to women whose husbands were not habitual of alcohol. However, alcoholism might not be the sole cause of DV as DV was also reported in homes where husband was reported nonalcoholic.

Bet and gamble: Gambling was another menace which leads to DV. It was found from the model that women whose husbands were in the habit of betting and gambling were significantly five times higher at risk of DV (OR = 5.869, CI = 4.561–7.553) as compared to those women whose husbands were not having such habits.

In the present study, the prevalence of DV in India was considerably high persisting across all socioeconomic strata existing in all the communities.( 5 , 11 ) Empirical results have suggested that education of women have an association with DV, which reflects a shift in the thinking pattern and burgeoning down the balance of power between husband and wife.( 9 , 15 ) But, the odds of DV were reduced only for women who had achieved higher education, suggesting that modest increases in educational attainment available to the majority of the women in India will not substantially alter their risks. However, data reflect that the victims were not only among illiterate and poor, who were besieged in traditional folklores and customs, it occurs across all social categories and social set-up.( 5 , 10 ) However, results reported that women working and contributing to the household budget were at increased risk of violence. The expectation expressed in the qualitative data that women's participation in economic activity would lead to higher status, security, and as a protective buffer against DV appears less realistic in the light of the quantitative results.( 1 , 3 )

One limitation of the study was that the family income was calculated based on self-reported items produced in the agricultural land. We presume that the women may not report correctly due to stigma and embarrassment. Previous studies suggest that highly normative support for violence against women exists in this setting and therefore may lead to underreporting Stephenson et al . 2006.

Despite the limitations of reporting bias, the findings highlight the complex and often contradictory nature of the relationships among factors at different levels and the ways in which they influence women's risk of suffering DV. In this context of gender inequality and poverty, the practice of patriarchy appears to exacerbate women's risk of DV. These causes reflect deep-rooted gender inequalities that persist across India.( 9 , 14 , 15 ) The findings of the association between the above analyzed factors suggest that there are broader and overarching reasons behind DV, whose implications go beyond individual and psychological situations. This practice of interpersonal violence may lead to affects the health of the women.( 1 , 11 ) Recognition of emerging health issues is needed to address women facing DV within the cultural milieu to improve maternal health and well-being.

The appalling toll will not be eased out until family, government, institutions, and civil society organizations address the issue collectively. These results provide vital information to assess the situation to develop interventions as well as policies and programmes toward preventing violence against the women. As India has already passed a bill against DV, the present results on robustness of the problem will be useful to sensitize the concerned agencies to strictly implement the law.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

- 1. Garcia-Moreno C, Heise L, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Watts C. Public health: Violence against women. Science. 2005;310:1282–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1121400. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2) 1998-99: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, Neelakantan N, Peedicayil A, Pillai R, Duvvury N. Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39:657–70. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001836. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Babu BV, Kar SK. Domestic violence against women in eastern India: a population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-129. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Miller BD. Wife-Beating in India: Variations on a Theme. In: Counts DA, Brown JK, Campbell JC, editors. Sanctions and Sanctuary: Cultural Perspectives on the Beating of Wives. Colorado: West view Press; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Krishnan S. Do structural inequalities contribute to marital violence? Ethnographic evidence from rural South India. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:759–75. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276078. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J. Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:132–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Visaria L. Violence against women: a field study. Econ Polit Wkly. 2000;35:1742–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottmoeller M. A global overview of gender-based violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;78(Suppl 1):S5–14. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00038-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Martin SL, Tsui AO, Maitra K, Marinshaw R. Domestic violence in northern India. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:417–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010021. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Rao V. Wife-beating in rural south India: a qualitative and econometric analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1169–80. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00252-3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Hindin MJ, Adair LS. Who's at risk? Factors associated with intimate partner violence in the Philippines. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1385–99. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00273-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Jejeebhoy SJ, Cook RJ. State accountability for wife-beating: the Indian challenge. Lancet. 1997;349(Suppl 1):sl10–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)90004-0. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Sen G, George A, Östlin P. Engendering International Health The Challenge of Equity. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (467.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance

Affiliations.

- 1 Public Health Foundation of India, Plot No. 47, Sector 44, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, 122002, India. [email protected].

- 2 Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, USA. [email protected].

- 3 Public Health Foundation of India, Plot No. 47, Sector 44, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, 122002, India.

- PMID: 35448988

- PMCID: PMC9023044

- DOI: 10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

Background: Prevalence of self-reported domestic violence against women in India is high. This paper investigates the national and sub-national trends in domestic violence in India to prioritise prevention activities and to highlight the limitations to data quality for surveillance in India.

Methods: Data were extracted from annual reports of National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) under four domestic violence crime-headings-cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment to suicide, and protection of women against domestic violence act. Rate for each crime is reported per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years, for India and its states from 2001 to 2018. Data on persons arrested and legal status of the cases were extracted.

Results: Rate of reported cases of cruelty by husband or relatives in India was 28.3 (95% CI 28.1-28.5) in 2018, an increase of 53% from 2001. State-level variations in this rate ranged from 0.5 (95% CI - 0.05 to 1.5) to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6-115.8) in 2018. Rate of reported dowry deaths and abetment to suicide was 2.0 (95% CI 2.0-2.0) and 1.4 (95% CI 1.4-1.4) in 2018 for India, respectively. Overall, a few states accounted for the temporal variation in these rates, with the reporting stagnant in most states over these years. The NCRB reporting system resulted in underreporting for certain crime-headings. The mean number of people arrested for these crimes had decreased over the period. Only 6.8% of the cases completed trials, with offenders convicted only in 15.5% cases in 2018. The NCRB data are available in heavily tabulated format with limited usage for intervention planning. The non-availability of individual level data in public domain limits exploration of patterns in domestic violence that could better inform policy actions to address domestic violence.

Conclusions: Urgent actions are needed to improve the robustness of NCRB data and the range of information available on domestic violence cases to utilise these data to effectively address domestic violence against women in India.

Keywords: Domestic violence; Dowry; India; Intimate partner; Suicide.

© 2022. The Author(s).

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Domestic Violence*

- Gender-Based Violence*

- Heart Arrest*

- India / epidemiology

Empowering Women Through Digital Transformation: A Path to Mitigate Intimate Partner Violence in India

- Published: 06 November 2024

Cite this article

- Anamika Chakraborty ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0005-0930-7900 1 &

- Suresh Jungari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4223-2603 1

Explore all metrics

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that a staggering one-third of women worldwide face intimate partner violence (IPV). Recent developments in digital transformations, such as the rapid use of mobile phones, internet use, and mobile use for financial transitions, have been evident. Earlier research shows that women’s digital empowerment or access to digital technologies protects them from IPV. However, there is less evidence on how various digital transformations in women’s lives lead to digital empowerment and protection from IPV. The study addresses whether empowering women through digital transformations leads to IPV prevention or reduction. We used National Family Health Survey-5 round data conducted during 2020–21 in a representative sample of India. We have constructed an additive index of digital empowerment using several questions about mobile use. The study results show that women with high digital empowerment reduced the odds of intimate partner violence when controlling socioeconomic variables.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Do electronic and economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence (IPV) in India?

An investigation of the longitudinal association of ownership of mobile phones and having internet access with intimate partner violence among young married women in India

Does Women Mobile Technology Inclusion Shape Their Attitude Towards Intimate Partner Violence? An Empirical Evidence from Sub-Saharan African Communities

Abramsky, T., Watts, C. H., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., ... & Heise, L. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health , 11 (1), 1–17.

Ackerson, L. K., & Subramanian, S. V. (2008). State gender inequality, socioeconomic status and intimate partner violence (IPV) in India: A multilevel analysis. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 43 (1), 81–102.

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad, J., Khan, M. E., Mozumdar, A., & Varma, D. S. (2016). Gender-based violence in rural Uttar Pradesh, India: Prevalence and association with reproductive health behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31 (19), 3111–3128.

Ahmad, J., Khan, N., & Mozumdar, A. (2021). Spousal violence against women in India: A social–ecological analysis using data from the National Family Health Survey 2015 to 2016. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36 (21–22), 10147–10181.

Aker, J. C., & Mbiti, I. M. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24 (3), 207–232.

Bhattacharya, H. (2016). Mass media exposure and attitude towards spousal violence in India. The Social Science Journal, 53 (4), 398–416.

Bhushan, K., & Singh, P. (2014). The effect of media on domestic violence norms: Evidence from India. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal , 9 (1).

Boyle, M. H., Georgiades, K., Cullen, J., & Racine, Y. (2009). Community influences on intimate partner violence in India: Women’s education, attitudes towards mistreatment and standards of living. Social Science and Medicine, 69 (5), 691–697.

Brahmapurkar, K. P. (2017). Gender equality in India hit by illiteracy, child marriages and violence: A hurdle for sustainable development. Pan African medical journal , 28 (1).

Chauhan, B. G., & Jungari, S. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of spousal violence against women in Afghanistan: Evidence from demographic and health survey data. Journal of Biosocial Science, 54 (2), 225–242.

Coker, A. L., Davis, K. E., Arias, I., Desai, S., Sanderson, M., Brandt, H. M., & Smith, P. H. (2002). Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23 (4), 260–268.

Coker, A. L., Sanderson, M., & Dong, B. (2004). Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 18 (4), 260–269.

Dalal, K., Lawoko, S., & Jansson, B. (2010). The relationship between intimate partner violence and maternal practices to correct child behavior: A study on women in Egypt. Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 2 (1), 25.

Dalal, K., Yasmin, M., Dahlqvist, H., & Klein, G. O. (2022). Do electronic and economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence (IPV) in India? BMC Women’s Health, 22 (1), 510.

Devries, K. M., Mak, J. Y., Garcia-Moreno, C., Petzold, M., Child, J. C., Falder, G., ... & Watts, C. H. (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science , 340 (6140), 1527–1528.

Garg, S., Singh, M. M., Rustagi, R., Engtipi, K., & Bala, I. (2019). Magnitude of domestic violence and its socio-demographic correlates among pregnant women in Delhi. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8 (11), 3634.

Gautam, S., & Jeong, H. S. (2019). Intimate partner violence in relation to husband characteristics and women empowerment: Evidence from Nepal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16 (5), 709.

GSMA Report. (2020). The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2022, Anne Delaporte, Kalvin Bahia, The-State-of-Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-Report-2022.pdf (gsma.com)

Heise, L. (86). y García-Moreno, C. (2002). Violence by intimate partners. World Report on Violence and Health , 87–121.

Hossieni, V. M., Toohill, J., Akaberi, A., & HashemiAsl, B. (2017). Influence of intimate partner violence during pregnancy on fear of childbirth. Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, 14 , 17–23.

IIPS, I. (2017). International institute for population sciences and ICF. National Family and Household Survey (NFHS) .

Jeyaseelan, L., Kumar, S., Neelakantan, N., Peedicayil, A., Pillai, R., & Duvvury, N. (2007). Physical spousal violence against women in India: Some risk factors. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39 (5), 657–670.

Jungari, S. (2021). Violent motherhood: Prevalence and factors affecting violence against pregnant women in India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36 (11–12), NP6323–NP6342.

Jungari, S., & Chinchore, S. (2022). Perception, prevalence, and determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy in urban slums of Pune, Maharashtra, India. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37 (1–2), NP239–NP263.

Jungari, S., Chauhan, B. G., & Ubale, P. (2019). Intimate partner violence driven fatal injuries among women in India: Empirical evidence from national family health survey 2015–2016. Social Science Spectrum, 5 (4), 164–173.

Google Scholar

Jungari, S., Chauhan, B. G., Bomble, P., & Pardhi, A. (2022). Violence against women in urban slums of India: A review of two decades of research. Global Public Health, 17 (1), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1850835

Kamimura, A., Ganta, V., Myers, K., & Thomas, T. (2014). Intimate partner violence and physical and mental health among women utilizing community health services in Gujarat, India. BMC Women’s Health, 14 (1), 1–11.

Kidman, R. (2017). Child marriage and intimate partner violence: A comparative study of 34 countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46 (2), 662–675.

Kim, J., & Lee, J. (2013). Prospective study on the reciprocal relationship between intimate partner violence and depression among women in Korea. Social Science and Medicine, 99 , 42–48.

Kimuna, S. R., Djamba, Y. K., Ciciurkaite, G., & Cherukuri, S. (2013). Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005–2006 national family health survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28 (4), 773–807.

Lana, R. (1992). Gender on the line: Women, the telephone, and community life.

Lee, D., & Jayachandran, S. (2009). The impact of mobile phones on the status of women in India.

Loke, A. Y., Wan, M. L. E., & Hayter, M. (2012). The lived experience of women victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21 (15–16), 2336–2346.

Ludermir, A. B., Lewis, G., Valongueiro, S. A., de Araújo, T. V. B., & Araya, R. (2010). Violence against women by their intimate partner during pregnancy and postnatal depression: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet, 376 (9744), 903–910.

Mahapatro, M., Prasad, M. M., & Singh, S. P. (2021). Role of social support in women facing domestic violence during lockdown of Covid-19 while cohabiting with the abusers: Analysis of cases registered with the family counseling centre, Alwar, India. Journal of Family Issues, 42 (11), 2609–2624.

Mookerjee, M., Ojha, M., & Roy, S. (2022). Who’s your neighbour? Social influences on domestic violence. The Journal of Development Studies, 58 (2), 350–369.

Nadda, A., Malik, J. S., Rohilla, R., Chahal, S., Chayal, V., & Arora, V. (2018). Study of domestic violence among currently married females of Haryana, India. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40 (6), 534–539.

Palermo, T., Bleck, J., & Peterman, A. (2014). Palermo et al. Respond to “disclosure of gender-based violence.” American Journal of Epidemiology, 179 (5), 619–620.

Patrikar, S., Basannar, D., Bhatti, V., Chatterjee, K., & Mahen, A. (2017). Association between intimate partner violence & HIV/AIDS: Exploring the pathways in Indian context. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 145 (6), 815.

Priya, N., Abhishek, G., Ravi, V., Aarushi, K., Nizamuddin, K., Dhanashri, B., ... & Sanjay, K. (2014). Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. New Delhi, International Center for Research on Women .

Ragavan, M., Iyengar, K., & Wurtz, R. (2015). Perceptions of options available for victims of physical intimate partner violence in northern India. Violence Against Women, 21 (5), 652–675.

Rahman, M., Hoque, M. A., & Makinoda, S. (2011). Intimate partner violence against women: Is women empowerment a reducing factor? A study from a national Bangladeshi sample. Journal of Family Violence, 26 , 411–420.

Raj, A., Saggurti, N., Lawrence, D., Balaiah, D., & Silverman, J. G. (2010). Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 110 (1), 35–39.

Rowan, K., Mumford, E., & Clark, C. J. (2018). Is women’s empowerment associated with help-seeking for spousal violence in India? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33 (9), 1519–1548.

Rowlands, J. (1997). Questioning empowerment: Working with women in Honduras . Oxfam.

Sabri, B., Renner, L. M., Stockman, J. K., Mittal, M., & Decker, M. R. (2014). Risk factors for severe intimate partner violence and violence-related injuries among women in India. Women and Health, 54 (4), 281–300.

Sabri, B., Sanchez, M. V., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). Motives and characteristics of domestic violence homicides and suicides among women in India. Health Care for Women International, 36 (7), 851–866.

Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., & García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399 (10327), 803–813.

Simister, J., & Mehta, P. S. (2010). Gender-based violence in India: Long-term trends. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25 (9), 1594–1611.

Stockman, J. K., Hayashi, H., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). Intimate partner violence and its health impact on ethnic minority women. Journal of Women’s Health, 24 (1), 62–79.

Talbot, N. L., & Gamble, S. A. (2008). IPT for women with trauma histories in community mental health care. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 38 , 35–44.

Thakkar, S., Muhammad, T., & Maurya, C. (2022). An investigation of the longitudinal association of ownership of mobile phone and having internet access with intimate partner violence among young married women from India.

Wagman, J. A., Donta, B., Ritter, J., Naik, D. D., Nair, S., Saggurti, N., ... & Silverman, J. G. (2018). Husband’s alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and family maltreatment of low-income postpartum women in Mumbai, India. Journal of interpersonal violence , 33 (14), 2241–2267.

Wood, S. N., Glass, N., & Decker, M. R. (2021). An integrative review of safety strategies for women experiencing intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 22 (1), 68–82.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence . World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2017). Violence against women: Key facts. World Health Organization. Last modified November , 29 , 2017.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Anamika Chakraborty & Suresh Jungari

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anamika Chakraborty .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chakraborty, A., Jungari, S. Empowering Women Through Digital Transformation: A Path to Mitigate Intimate Partner Violence in India. Glob Soc Welf (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-024-00360-8

Download citation

Accepted : 01 October 2024

Published : 06 November 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-024-00360-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Intimate partner violence (IPV)

- Digital empowerment

- Gender-based violence

- Domestic violence

- Mobile phones

- Internet access

- Financial autonomy

- Technology and empowerment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Domestic violence against women: A hidden and deeply rooted health issue in India

Abantika bhattacharya, shamima yasmin, amiya bhattacharya, baijayanti baur, kishore p madhwani.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Dr. Shamima Yasmin, Department of Community Medicine, Midnapore Medical College, Midnapore – 721 101, West Bengal, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2020 Mar 30; Revised 2020 Apr 25; Accepted 2020 Jul 2; Collection date 2020 Oct.

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Background:

Domestic violence was identified as a major contributor to the global burden of ill health in terms of female morbidity leading to psychological trauma and depression, injuries, sexually transmitted diseases, suicide, and murder.