How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

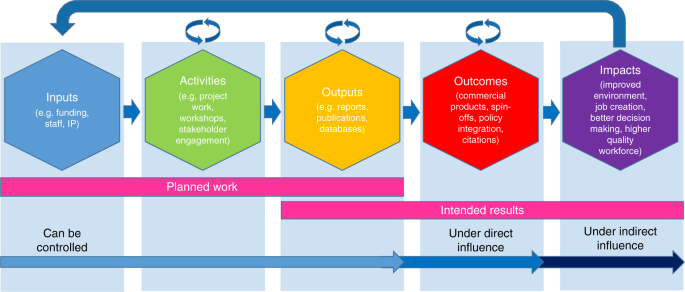

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project .

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement , devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes , demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

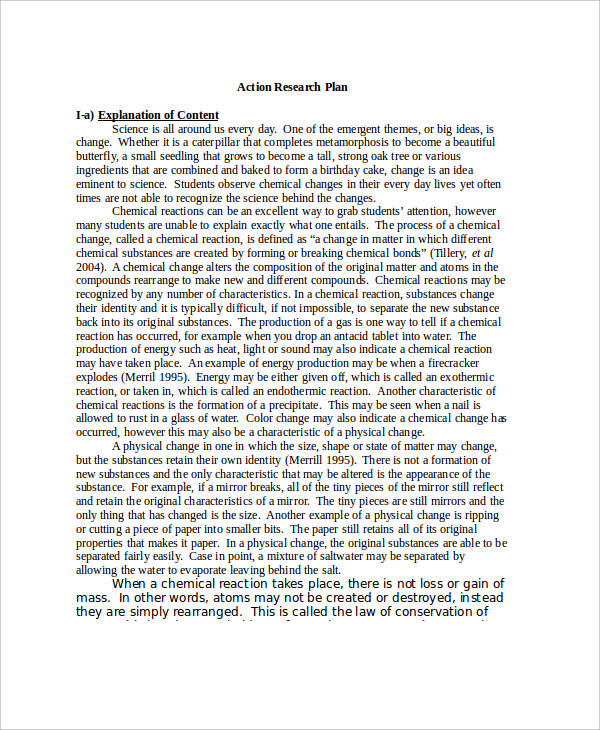

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Once you have outlined your goals, objectives, steps, and tasks, it’s time to drill down on selecting research methods . You’ll want to leverage specific research strategies and processes. When you know what methods will help you reach your goals, you and your teams will have direction to perform and execute your assigned tasks.

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews : this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies : this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting : participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups : use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies : ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys : get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing : tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing : ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project . Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

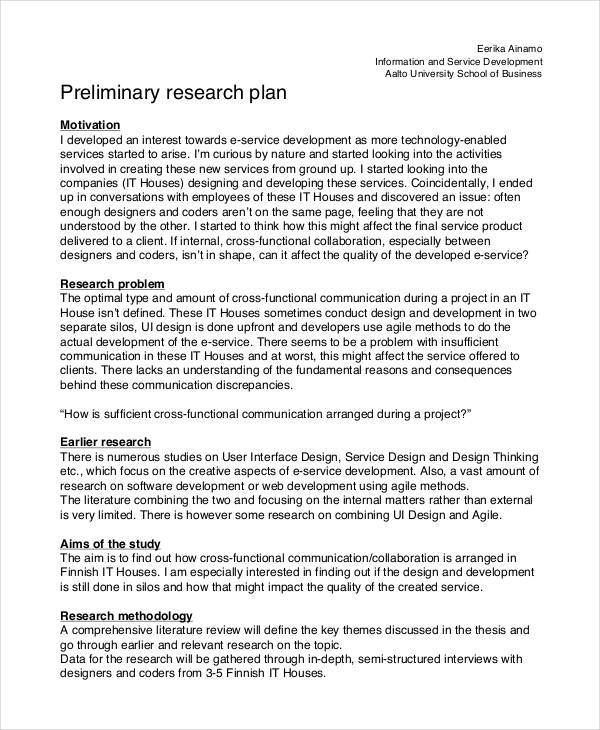

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty . But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 7 March 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

FLEET LIBRARY | Research Guides

Rhode island school of design, create a research plan: research plan.

- Research Plan

- Literature Review

- Ulrich's Global Serials Directory

- Related Guides

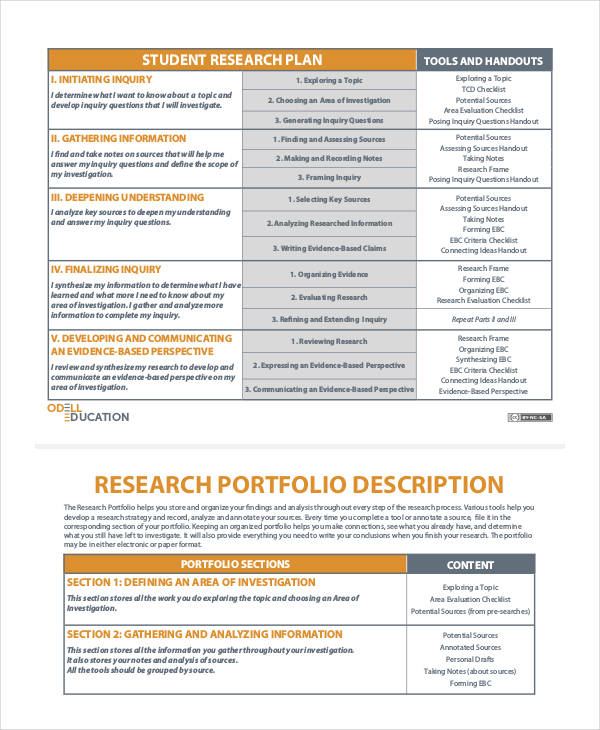

A research plan is a framework that shows how you intend to approach your topic. The plan can take many forms: a written outline, a narrative, a visual/concept map or timeline. It's a document that will change and develop as you conduct your research. Components of a research plan

1. Research conceptualization - introduces your research question

2. Research methodology - describes your approach to the research question

3. Literature review, critical evaluation and synthesis - systematic approach to locating,

reviewing and evaluating the work (text, exhibitions, critiques, etc) relating to your topic

4. Communication - geared toward an intended audience, shows evidence of your inquiry

Research conceptualization refers to the ability to identify specific research questions, problems or opportunities that are worthy of inquiry. Research conceptualization also includes the skills and discipline that go beyond the initial moment of conception, and which enable the researcher to formulate and develop an idea into something researchable ( Newbury 373).

Research methodology refers to the knowledge and skills required to select and apply appropriate methods to carry through the research project ( Newbury 374) .

Method describes a single mode of proceeding; methodology describes the overall process.

Method - a way of doing anything especially according to a defined and regular plan; a mode of procedure in any activity

Methodology - the study of the direction and implications of empirical research, or the sustainability of techniques employed in it; a method or body of methods used in a particular field of study or activity *Browse a list of research methodology books or this guide on Art & Design Research

Literature Review, critical evaluation & synthesis

A literature review is a systematic approach to locating, reviewing, and evaluating the published work and work in progress of scholars, researchers, and practitioners on a given topic.

Critical evaluation and synthesis is the ability to handle (or process) existing sources. It includes knowledge of the sources of literature and contextual research field within which the person is working ( Newbury 373).

Literature reviews are done for many reasons and situations. Here's a short list:

| to learn about a field of study to understand current knowledge on a subject to formulate questions & identify a research problem to focus the purpose of one's research to contribute new knowledge to a field personal knowledge intellectual curiosity | to prepare for architectural program writing academic degrees grant applications proposal writing academic research planning funding |

Sources to consult while conducting a literature review:

Online catalogs of local, regional, national, and special libraries

meta-catalogs such as worldcat , Art Discovery Group , europeana , world digital library or RIBA

subject-specific online article databases (such as the Avery Index, JSTOR, Project Muse)

digital institutional repositories such as Digital Commons @RISD ; see Registry of Open Access Repositories

Open Access Resources recommended by RISD Research LIbrarians

works cited in scholarly books and articles

print bibliographies

the internet-locate major nonprofit, research institutes, museum, university, and government websites

search google scholar to locate grey literature & referenced citations

trade and scholarly publishers

fellow scholars and peers

Communication

Communication refers to the ability to

- structure a coherent line of inquiry

- communicate your findings to your intended audience

- make skilled use of visual material to express ideas for presentations, writing, and the creation of exhibitions ( Newbury 374)

Research plan framework: Newbury, Darren. "Research Training in the Creative Arts and Design." The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts . Ed. Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. New York: Routledge, 2010. 368-87. Print.

About the author

Except where otherwise noted, this guide is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution license

source document

Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 20, 2023 5:05 PM

- URL: https://risd.libguides.com/researchplan

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Guide

How to Write a Research Plan

- Research plan definition

- Purpose of a research plan

- Research plan structure

- Step-by-step writing guide

Tips for creating a research plan

- Research plan examples

Research plan: definition and significance

What is the purpose of a research plan.

- Bridging gaps in the existing knowledge related to their subject.

- Reinforcing established research about their subject.

- Introducing insights that contribute to subject understanding.

Research plan structure & template

Introduction.

- What is the existing knowledge about the subject?

- What gaps remain unanswered?

- How will your research enrich understanding, practice, and policy?

Literature review

Expected results.

- Express how your research can challenge established theories in your field.

- Highlight how your work lays the groundwork for future research endeavors.

- Emphasize how your work can potentially address real-world problems.

5 Steps to crafting an effective research plan

Step 1: define the project purpose, step 2: select the research method, step 3: manage the task and timeline, step 4: write a summary, step 5: plan the result presentation.

- Brainstorm Collaboratively: Initiate a collective brainstorming session with peers or experts. Outline the essential questions that warrant exploration and answers within your research.

- Prioritize and Feasibility: Evaluate the list of questions and prioritize those that are achievable and important. Focus on questions that can realistically be addressed.

- Define Key Terminology: Define technical terms pertinent to your research, fostering a shared understanding. Ensure that terms like “church” or “unreached people group” are well-defined to prevent ambiguity.

- Organize your approach: Once well-acquainted with your institution’s regulations, organize each aspect of your research by these guidelines. Allocate appropriate word counts for different sections and components of your research paper.

Research plan example

- Writing a Research Paper

- Research Paper Title

- Research Paper Sources

- Research Paper Problem Statement

- Research Paper Thesis Statement

- Hypothesis for a Research Paper

- Research Question

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Summary

- Research Paper Prospectus

- Research Paper Proposal

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Styles

- AMA Style Research Paper

- MLA Style Research Paper

- Chicago Style Research Paper

- APA Style Research Paper

- Research Paper Structure

- Research Paper Cover Page

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Body Paragraph

- Research Paper Literature Review

- Research Paper Background

- Research Paper Methods Section

- Research Paper Results Section

- Research Paper Discussion Section

- Research Paper Conclusion

- Research Paper Appendix

- Research Paper Bibliography

- APA Reference Page

- Annotated Bibliography

- Bibliography vs Works Cited vs References Page

- Research Paper Types

- What is Qualitative Research

Receive paper in 3 Hours!

- Choose the number of pages.

- Select your deadline.

- Complete your order.

Number of Pages

550 words (double spaced)

Deadline: 10 days left

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

- Research Guides

- Begin Your Research

- Outline and Plan

Begin Your Research: Outline and Plan

- Research Process

- Background Info

- Research Questions

Outlining and Planning Ahead: Confining or Comforting?

Creating a plan and outline before starting your research paper can lead to a more successful and satisfying writing process. Contrary to concerns about stifling creativity, planning ahead actually frees your mind from cluttered thoughts and allows for creativity to flourish within the boundaries of your rough plan. Just like various aspects of the natural and man-made world, successful creations often begin with some form of structure or boundary. Outlines serve as recipes for your paper, while research plans function as shopping lists, helping you organize your ideas and check your progress once you've completed your work.

Why Create an Outline?

According to the Purdue OWL's Writing Process guide , using an outline is helpful when wanting to "show the hierarchical relationship or logical ordering of information. For research papers, an outline may help you keep track of large amounts of information." Outlines even help those that are preparing a speech or presentation to deliver in front of an audience. Therefore, an outline has many benefits in aiding your writing, organizing your thoughts, keeping your material in logical structures, and giving your writing a boundary within which to keep focus. Making any kind of outline, no matter how rough or polished, will benefit you.

What is an Outline?

An outline is a structured document that lists the main parts of your research paper, essay, presentation, or report. It provides a roadmap for your planned writing, utilizing numbered lists to indicate the larger and nested structures.

- You can further divide your subtopics as needed using Arabic numerals, but there should always be more than one.

- Further subdivision

- Subtopic of First Part (more specific in relationship to the First Part heading)

- Subtopic of First Part (more specific in relationship to the heading above)

- Subtopic of First Part (there should always be more than one subtopic of each main part)

Unless required to use a certain outline template, you have the freedom to choose the type of outline that suits you best, whether it is rough or structured with full sentences, phrases, and alphanumeric ordered lists. Any kind of outline can be effective in aiding your writing process. In conclusion, outlining is a valuable tool for successful writing, allowing you to organize your thoughts and achieve your goals efficiently. By creating a clear plan, you can enhance your creativity and produce a more cohesive and well-structured piece of work.

Please open Purdue OWL's Writing Process guide or separate PDF which provides examples of full sentence and alphanumeric outlines.

- Research Outline Template (RTF file)

- Research Outline Template (PDF File)

Creating a Research Plan

Your final step in the beginning stages of your research journey is making a plan for the rest of your research and writing steps. Treat it like a schedule or shopping list, utilizing a short to-do list or a detailed schedule. Remember, this plan you devise is not restrictive; it's a guide to set achievable goals within one overall process. Here's what to include:

What should you include in a research plan?

As stated above, you don't need to fill out an entire research plan right now, *but as you learn more throughout this "How to Research" guide series. The following items are recommended items to put in your research plan:

- The research topic you have chosen and explored

- The research question or thesis statement you have drafted

- Any important assignment due dates, especially if you have to turn anything in at different stages (topic selection, annotated bibliography, rough draft, final draft)

- The kind of information you are interested in including (supporting or contrasting perspectives, definitions, analysis, facts, background, or statistics)*

- The search terms you have brainstormed and planned in the form of keywords, phrases, or search strings*

- The places you will go to look for information (library searchable databases, websites, physical libraries)*

- If there are any limitations or prohibited sources (no website or encyclopedias, for example)

You can use the provided templates to create your research plan as you progress through the "How to Research" guide series.

- Research Plan Template (RTF File)

- Research Plan Template (PDF File)

Congratulations on completing the initial steps of your research journey, and now you're ready to explore different types of information and sources.

- Learn the Types of Research Sources

- Find Research Sources

Image Source

Unless otherwise indicated, all images are courtesy of Adobe Stock. Paul J. Meyer quote image made in Canva, courtesy of Kristen Cook. The Research Outline Template was adapted from EasyBib.com.

- << Previous: Research Questions

- Next: Need Help? >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 7:16 PM

- URL: https://mclennan.libguides.com/Begin

© McLennan Community College

1400 College Drive Waco, Texas 76708, USA

+1 (254) 299-8622

How to Write a Research Plan

Your answers to these questions form your research strategy. Most likely, you’ve addressed some of these issues in your proposal. But you are further along now, and you can flesh out your answers. With your instructor’s help, you should make some basic decisions about what information to collect and what methods to use in analyzing it. You will probably develop this research strategy gradually and, if you are like the rest of us, you will make some changes, large and small, along the way. Still, it is useful to devise a general plan early, even though you will modify it as you progress. Develop a tentative research plan early in the project. Write it down and share it with your instructor. The more concrete and detailed the plan, the better the feedback you’ll get.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

This research plan does not need to be elaborate or time-consuming. Like your working bibliography, it is provisional, a work in progress. Still, it is helpful to write it down since it will clarify a number of issues for you and your professor.

Writing a Research Plan

To write out your research plan, begin by restating your main thesis question and any secondary ones. They may have changed a bit since your original proposal. If these questions bear on a particular theory or analytic perspective, state that briefly. In the social sciences, for example, two or three prominent theories might offer different predictions about your subject. If so, then you might want to explore these differences in your thesis and explain why some theories work better (or worse) in this particular case. Likewise, in the humanities, you might consider how different theories offer different insights and contrasting perspectives on the particular novel or film you are studying. If you intend to explore these differences, state your goal clearly in the research plan so you can discuss it later with your professor. Next, turn to the heart of this exercise, your proposed research strategy. Try to explain your basic approach, the materials you will use, and your method of analysis. You may not know all of these elements yet, but do the best you can. Briefly say how and why you think they will help answer your main questions.

Be concrete. What data will you collect? Which poems will you read? Which paintings will you compare? Which historical cases will you examine? If you plan to use case studies, say whether you have already selected them or settled on the criteria for choosing them. Have you decided which documents and secondary sources are most important? Do you have easy access to the data, documents, or other materials you need? Are they reliable sources—the best information you can get on the subject? Give the answers if you have them, or say plainly that you don’t know so your instructor can help. You should also discuss whether your research requires any special skills and, of course, whether you have them. You can—and should—tailor your work to fit your skills.

If you expect to challenge other approaches—an important element of some theses—which ones will you take on, and why? This last point can be put another way: Your project will be informed by some theoretical traditions and research perspectives and not others. Your research will be stronger if you clarify your own perspective and show how it usefully informs your work. Later, you may also enter the jousts and explain why your approach is superior to the alternatives, in this particular study and perhaps more generally. Your research plan should state these issues clearly so you can discuss them candidly and think them through.

If you plan to conduct tests, experiments, or surveys, discuss them, too. They are common research tools in many fields, from psychology and education to public health. Now is the time to spell out the details—the ones you have nailed down tight and the ones that are still rattling around, unresolved. It’s important to bring up the right questions here, even if you don’t have all the answers yet. Raising these questions directly is the best way to get the answers. What kinds of tests or experiments do you plan, and how will you measure the results? How will you recruit your test subjects, and how many will be included in your sample? What test instruments or observational techniques will you use? How reliable and valid are they? Your instructor can be a great source of feedback here.

Your research plan should say:

- What materials you will use

- What methods you will use to investigate them

- Whether your work follow a particular approach or theory

There are also ethical issues to consider. They crop up in any research involving humans or animals. You need to think carefully about them, underscore potential problems, and discuss them with your professor. You also need to clear this research in advance with the appropriate authorities at your school, such as the committee that reviews proposals for research on human subjects.

Not all these issues and questions will bear on your particular project. But some do, and you should wrestle with them as you begin research. Even if your answers are tentative, you will still gain from writing them down and sharing them with your instructor. That’s how you will get the most comprehensive advice, the most pointed recommendations. If some of these issues puzzle you, or if you have already encountered some obstacles, share them, too, so you can either resolve the problems or find ways to work around them.

Remember, your research plan is simply a working product, designed to guide your ongoing inquiry. It’s not a final paper for a grade; it’s a step toward your final paper. Your goal in sketching it out now is to understand these issues better and get feedback from faculty early in the project. It may be a pain to write it out, but it’s a minor sting compared to major surgery later.

Checklist for Conducting Research

- Familiarize yourself with major questions and debates about your topic.

- Is appropriate to your topic;

- Addresses the main questions you propose in your thesis;

- Relies on materials to which you have access;

- Can be accomplished within the time available;

- Uses skills you have or can acquire.

- Divide your topic into smaller projects and do research on each in turn.

- Write informally as you do research; do not postpone this prewriting until all your research is complete.

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Write Your Research Plan

In this part, we give you detailed information about writing an effective Research Plan. We start with the importance and parameters of significance and innovation.

We then discuss how to focus the Research Plan, relying on the iterative process described in the Iterative Approach to Application Planning Checklist shown at Draft Specific Aims and give you advice for filling out the forms.

You'll also learn the importance of having a well-organized, visually appealing application that avoids common missteps and the importance of preparing your just-in-time information early.

While this document is geared toward the basic research project grant, the R01, much of it is useful for other grant types.

Table of Contents

Research plan overview and your approach, craft a title, explain your aims, research strategy instructions, advice for a successful research strategy, graphics and video, significance, innovation, and approach, tracking for your budget, preliminary studies or progress report, referencing publications, review and finalize your research plan, abstract and narrative.

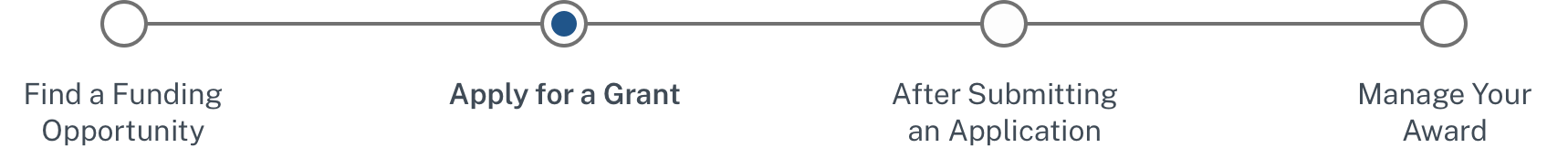

Your application's Research Plan has two sections:

- Specific Aims —a one-page statement of your objectives for the project.

- Research Strategy —a description of the rationale for your research and your experiments in 12 pages for an R01.

In your Specific Aims, you note the significance and innovation of your research; then list your two to three concrete objectives, your aims.

Your Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, where you describe your research rationale and the experiments you will conduct to accomplish each aim. Though how you organize it is largely up to you, NIH expects you to follow these guidelines.

- Organize using bold headers or an outline or numbering system—or both—that you use consistently throughout.

- Start each section with the appropriate header: Significance, Innovation, or Approach.

- Organize the Approach section around your Specific Aims.

Format of Your Research Plan

To write the Research Plan, you don't need the application forms. Write the text in your word processor, turn it into a PDF file, and upload it into the application form when it's final.

Because NIH may return your application if it doesn't meet all requirements, be sure to follow the rules for font, page limits, and more. Read the instructions at NIH’s Format Attachments .

For an R01, the Research Strategy can be up to 12 pages, plus one page for Specific Aims. Don't pad other sections with information that belongs in the Research Plan. NIH is on the lookout and may return your application to you if you try to evade page limits.

Follow Examples

As you read this page, look at our Sample Applications and More to see some of the different strategies successful PIs use to create an outstanding Research Plan.

Keeping It All In Sync

Writing in a logical sequence will save you time.

Information you put in the Research Plan affects just about every other application part. You'll need to keep everything in sync as your plans evolve during the writing phase.

It's best to consider your writing as an iterative process. As you develop and finalize your experiments, you will go back and check other parts of the application to make sure everything is in sync: the "who, what, when, where, and how (much money)" as well as look again at the scope of your plans.

In that vein, writing in a logical sequence is a good approach that will save you time. We suggest proceeding in the following order:

- Create a provisional title.

- Write a draft of your Specific Aims.

- Start with your Significance and Innovation sections.

- Then draft the Approach section considering the personnel and skills you'll need for each step.

- Evaluate your Specific Aims and methods in light of your expected budget (for a new PI, it should be modest, probably under the $250,000 for NIH's modular budget).

- As you design experiments, reevaluate your hypothesis, aims, and title to make sure they still reflect your plans.

- Prepare your Abstract (a summary of your Specific Aims).

- Complete the other forms.

Even the smaller sections of your application need to be well-organized and readable so reviewers can readily grasp the information. If writing is not your forte, get help.

To view writing strategies for successful applications, see our Sample Applications and More . There are many ways to create a great application, so explore your options.

Within the character limit, include the important information to distinguish your project within the research area, your project's goals, and the research problem.

Giving your project a title at the outset can help you stay focused and avoid a meandering Research Plan. So you may want to launch your writing by creating a well-defined title.

NIH gives you a 200 character limit, but don’t feel obliged to use all of that allotment. Instead, we advise you to keep the title as succinct as possible while including the important information to distinguish your project within the research area. Make your title reflect your project's goals, the problem your project addresses, and possibly your approach to studying it. Make your title specific: saying you are studying lymphocyte trafficking is not informative enough.

For examples of strong titles, see our Sample Applications and More .

After you write a preliminary title, check that

- My title is specific, indicating at least the research area and the goals of my project.

- It is 200 characters or less.

- I use as simple language as possible.

- I state the research problem and, possibly, my approach to studying it.

- I use a different title for each of my applications. (Note: there are exceptions, for example, for a renewal—see Apply for Renewal for details.)

- My title has appropriate keywords.

Later you may want to change your initial title. That's fine—at this point, it's just an aid to keep your plans focused.

Since all your reviewers read your Specific Aims, you want to excite them about your project.

If testing your hypothesis is the destination for your research, your Research Plan is the map that takes you there.

You'll start by writing the smaller part, the Specific Aims. Think of the one-page Specific Aims as a capsule of your Research Plan. Since all your reviewers read your Specific Aims, you want to excite them about your project.

For more on crafting your Specific Aims, see Draft Specific Aims .

Write a Narrative

Use at least half the page to provide the rationale and significance of your planned research. A good way to start is with a sentence that states your project's goals.

For the rest of the narrative, you will describe the significance of your research, and give your rationale for choosing the project. In some cases, you may want to explain why you did not take an alternative route.

Then, briefly describe your aims, and show how they build on your preliminary studies and your previous research. State your hypothesis.

If it is likely your application will be reviewed by a study section with broad expertise, summarize the status of research in your field and explain how your project fits in.

In the narrative part of the Specific Aims of many outstanding applications, people also used their aims to

- State the technologies they plan to use.

- Note their expertise to do a specific task or that of collaborators.

- Describe past accomplishments related to the project.

- Describe preliminary studies and new and highly relevant findings in the field.

- Explain their area's biology.

- Show how the aims relate to one another.

- Describe expected outcomes for each aim.

- Explain how they plan to interpret data from the aim’s efforts.

- Describe how to address potential pitfalls with contingency plans.

Depending on your situation, decide which items are important for you. For example, a new investigator would likely want to highlight preliminary data and qualifications to do the work.

Many people use bold or italics to emphasize items they want to bring to the reviewers' attention, such as the hypothesis or rationale.

Detail Your Aims

After the narrative, enter your aims as bold bullets, or stand-alone or run-on headers.

- State your plans using strong verbs like identify, define, quantify, establish, determine.

- Describe each aim in one to three sentences.

- Consider adding bullets under each aim to refine your objectives.

How focused should your aims be? Look at the example below.

Spot the Sample

Read the Specific Aims of the Application from Drs. Li and Samulski , "Enhance AAV Liver Transduction with Capsid Immune Evasion."

- Aim 1. Study the effect of adeno-associated virus (AAV) empty particles on AAV capsid antigen cross-presentation in vivo .

- Aim 2. Investigate AAV capsid antigen presentation following administration of AAV mutants and/or proteasome inhibitors for enhanced liver transduction in vivo .

- Aim 3. Isolate AAV chimeric capsids with human hepatocyte tropism and the capacity for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) evasion.

After finishing the draft Specific Aims, check that

- I keep to the one-page limit.

- Each of my two or three aims is a narrowly focused, concrete objective I can achieve during the grant.

- They give a clear picture of how my project can generate knowledge that may improve human health.

- They show my project's importance to science, how it addresses a critical research opportunity that can move my field forward.

- My text states how my work is innovative.

- I describe the biology to the extent needed for my reviewers.

- I give a rationale for choosing the topic and approach.

- I tie the project to my preliminary data and other new findings in the field.

- I explicitly state my hypothesis and why testing it is important.

- My aims can test my hypothesis and are logical.

- I can design and lead the execution of two or three sets of experiments that will strive to accomplish each aim.

- As much as possible, I use language that an educated person without expertise can understand.

- My text has bullets, bolding, or headers so reviewers can easily spot my aims (and other key items).

For each element listed above, analyze your text and revise it until your Specific Aims hit all the key points you'd like to make.

After the list of aims, some people add a closing paragraph, emphasizing the significance of the work, their collaborators, or whatever else they want to focus reviewers' attention on.

Your Research Strategy is the bigger part of your application's Research Plan (the other part is the Specific Aims—discussed above.)

The Research Strategy is the nuts and bolts of your application, describing the rationale for your research and the experiments you will do to accomplish each aim. It is structured as follows:

- Significance

- You can either include this information as a subsection of Approach or integrate it into any or all of the three main sections.

- If you do the latter, be sure to mark the information clearly, for example, with a bold subhead.

- Possible other sections, for example, human subjects, vertebrate animals, select agents, and others (these do not count toward the page limit).

Though how you organize your application is largely up to you, NIH does want you to follow these guidelines:

- Add bold headers or an outlining or numbering system—or both—that you use consistently throughout.

- Start each of the Research Strategy's sections with a header: Significance, Innovation, and Approach.

For an R01, the Research Strategy is limited to 12 pages for the three main sections and the preliminary studies only. Other items are not included in the page limit.

Find instructions for R01s in the SF 424 Application Guide—go to NIH's SF 424 (R&R) Application and Electronic Submission Information for the generic SF 424 Application Guide or find it in your notice of funding opportunity (NOFO).

For most applications, you need to address Rigor and Reproducibility by describing the experimental design and methods you propose and how they will achieve robust and unbiased results. The requirement applies to research grant, career development, fellowship, and training applications.

If you're responding to an institute-specific program announcement (PA) (not a parent program announcement) or a request for applications (RFA), check the NIH Guide notice, which has additional information you need. Should it differ from the NOFO, go with the NIH Guide .

Also note that your application must meet the initiative's objectives and special requirements. NIAID program staff will check your application, and if it is not responsive to the announcement, your application will be returned to you without a review.

When writing your Research Strategy, your goal is to present a well-organized, visually appealing, and readable description of your proposed project. That means your writing should be streamlined and organized so your reviewers can readily grasp the information. If writing is not your forte, get help.

There are many ways to create an outstanding Research Plan, so explore your options.

What Success Looks Like

Your application's Research Plan is the map that shows your reviewers how you plan to test your hypothesis.

It not only lays out your experiments and expected outcomes, but must also convince your reviewers of your likely success by allaying any doubts that may cross their minds that you will be able to conduct the research.

Notice in the sample applications how the writing keeps reviewers' eyes on the ball by bringing them back to the main points the PIs want to make. Write yourself an insurance policy against human fallibility: if it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again.

The Big Three

So as you write, put the big picture squarely in your sights. When reviewers read your application, they'll look for the answers to three basic questions:

- Can your research move your field forward?

- Is the field important—will progress make a difference to human health?

- Can you and your team carry out the work?

Add Emphasis

Savvy PIs create opportunities to drive their main points home. They don't stop at the Significance section to emphasize their project's importance, and they look beyond their biosketches to highlight their team's expertise.

Don't take a chance your reviewer will gloss over that one critical sentence buried somewhere in your Research Strategy or elsewhere. Write yourself an insurance policy against human fallibility: if it's a key point, repeat it, then repeat it again.

Add more emphasis by putting the text in bold, or bold italics (in the modern age, we skip underlining—it's for typewriters).

Here are more strategies from our successful PIs:

- While describing a method in the Approach section, they state their or collaborators' experience with it.

- They point out that they have access to a necessary piece of equipment.

- When explaining their field and the status of current research, they weave in their own work and their preliminary data.

- They delve into the biology of the area to make sure reviewers will grasp the importance of their research and understand their field and how their work fits into it.

You can see many of these principles at work in the Approach section of the Application from Dr. William Faubion , "Inflammatory cascades disrupt Treg function through epigenetic mechanisms."

- Reviewers felt that the experiments described for Aim 1 will yield clear results.

- The plans to translate those findings to gene targets of relevance are well outlined and focused.

- He ties his proposed experiments to the larger picture, including past research and strong preliminary data for the current application.

Anticipate Reviewer Questions

Our applicants not only wrote with their reviewers in mind they seemed to anticipate their questions. You may think: how can I anticipate all the questions people may have? Of course you can't, but there are some basic items (in addition to the "big three" listed above) that will surely be on your reviewers' minds:

- Will the investigators be able to get the work done within the project period, or is the proposed work over ambitious?

- Did the PI describe potential pitfalls and possible alternatives?

- Will the experiments generate meaningful data?

- Could the resulting data prove the hypothesis?

- Are others already doing the work, or has it been already completed?

Address these questions; then spend time thinking about more potential issues specific to you and your research—and address those too.

For applications, a picture can truly be worth a thousand words. Graphics can illustrate complex information in a small space and add visual interest to your application.

Look at our sample applications to see how the investigators included schematics, tables, illustrations, graphs, and other types of graphics to enhance their applications.

Consider adding a timetable or flowchart to illustrate your experimental plan, including decision trees with alternative experimental pathways to help your reviewers understand your plans.

Plan Ahead for Video

If you plan to send one or more videos, you'll need to meet certain standards and include key information in your Research Strategy now.

To present some concepts or demonstrations, video may enhance your application beyond what graphics alone can achieve. However, you can't count on all reviewers being able to see or hear video, so you'll want to be strategic in how you incorporate it into your application.

Be reviewer-friendly. Help your cause by taking the following steps:

- Caption any narration in the video.

- Choose evocative still images from your video to accompany your summary.

- Write your summary of the video carefully so the text would make sense even without the video.

In addition to those considerations, create your videos to fit NIH’s technical requirements. Learn more in the SF 424 Form Instructions .

Next, as you write your Research Strategy, include key images from the video and a brief description.

Then, state in your cover letter that you plan to send video later. (Don't attach your files to the application.)

After you apply and get assignment information from the Commons, ask your assigned scientific review officer (SRO) how your business official should send the files. Your video files are due at least one month before the peer review meeting.

Know Your Audience's Perspective

The primary audience for your application is your peer review group. Learn how to write for the reviewers who are experts in your field and those who are experts in other fields by reading Know Your Audience .

Be Organized: A B C or 1 2 3?

In the top-notch applications we reviewed, organization ruled but followed few rules. While you want to be organized, how you go about it is up to you.

Nevertheless, here are some principles to follow:

- Start each of the Research Strategy's sections with a header: Significance, Innovation, and Approach—this you must do.

The Research Strategy's page limit—12 for R01s—is for the three main parts: Significance, Innovation, and Approach and your preliminary studies (or a progress report if you're renewing your grant). Other sections, for example, research animals or select agents, do not have a page limit.

Although you will emphasize your project's significance throughout the application, the Significance section should give the most details. Don't skimp—the farther removed your reviewers are from your field, the more information you'll need to provide on basic biology, importance of the area, research opportunities, and new findings.

When you describe your project's significance, put it in the context of 1) the state of your field, 2) your long-term research plans, and 3) your preliminary data.

In our Sample Applications , you can see that both investigators and reviewers made a case for the importance of the research to improving human health as well as to the scientific field.

Look at the Significance section of the Application from Dr. Mengxi Jiang , "Intersection of polyomavirus infection and host cellular responses," to see how these elements combine to make a strong case for significance.

- Dr. Jiang starts with a summary of the field of polyomavirus research, identifying critical knowledge gaps in the field.

- The application ties the lab's previous discoveries and new research plans to filling those gaps, establishing the significance with context.

- Note the use of formatting, whitespace, and sectioning to highlight key points and make it easier for reviewers to read the text.

After conveying the significance of the research in several parts of the application, check that

- In the Significance section, I describe the importance of my hypothesis to the field (especially if my reviewers are not in it) and human disease.

- I also point out the project's significance throughout the application.

- The application shows that I am aware of opportunities, gaps, roadblocks, and research underway in my field.

- I state how my research will advance my field, highlighting knowledge gaps and showing how my project fills one or more of them.

- Based on my scan of the review committee roster, I determine whether I cannot assume my reviewers will know my field and provide some information on basic biology, the importance of the area, knowledge gaps, and new findings.

If you are either a new PI or entering a new area: be cautious about seeming too innovative. Not only is innovation just one of five review criteria, but there might be a paradigm shift in your area of science. A reviewer may take a challenge to the status quo as a challenge to his or her world view.

When you look at our sample applications, you see that both the new and experienced investigators are not generally shifting paradigms. They are using new approaches or models, working in new areas, or testing innovative ideas.

After finishing the draft innovation section, check that

- I show how my proposed research is new and unique, e.g., explores new scientific avenues, has a novel hypothesis, will create new knowledge.

- Most likely, I explain how my project's research can refine, improve, or propose a new application of an existing concept or method.

- Make a very strong case for challenging the existing paradigm.

- Have data to support the innovative approach.

- Have strong evidence that I can do the work.

In your Approach, you spell out a few sets of experiments to address each aim. As we noted above, it's a good idea to restate the key points you've made about your project's significance, its place in your field, and your long-term goals.

You're probably wondering how much detail to include.

If you look at our sample applications as a guide, you can see very different approaches. Though people generally used less detail than you'd see in a scientific paper, they do include some experimental detail.

Expect your assigned reviewers to scrutinize your approach: they will want to know what you plan to do and how you plan to do it.

NIH data show that of the peer review criteria, approach has the highest correlation with the overall impact score.

Look at the Application from Dr. Mengxi Jiang , "Intersection of polyomavirus infection and host cellular responses," to see how a new investigator handled the Approach section.

For an example of an experienced investigator's well-received Approach section, see the Application from Dr. William Faubion , "Inflammatory cascades disrupt Treg function through epigenetic mechanisms."

Especially if you are a new investigator, you need enough detail to convince reviewers that you understand what you are undertaking and can handle the method.

- Cite a publication that shows you can handle the method where you can, but give more details if you and your team don't have a proven record using the method—and state explicitly why you think you will succeed.

- If space is short, you could also focus on experiments that highlight your expertise or are especially interesting. For experiments that are pedestrian or contracted out, just list the method.

Be sure to lay out a plan for alternative experiments and approaches in case you get negative or surprising results. Show reviewers you have a plan for spending the four or five years you will be funded no matter where the experiments lead.

See the Application from Drs. Li and Samulski , "Enhance AAV Liver Transduction with Capsid Immune Evasion," for a strong Approach section covering potential. As an example, see section C.1.3.'s alternative approaches.

Here are some pointers for organizing your Approach:

- Enter a bold header for each Specific Aim.

- Under each aim, describe the first set of experiments.

- If you get result X, you will follow pathway X; if you get result Y, you will follow pathway Y.

- Consider illustrating this with a flowchart.

Trim the fat—omit all information not needed to make your case. If you try to wow reviewers with your knowledge, they'll find flaws and penalize you heavily. Don't give them ammunition by including anything you don't need.

As you design your experiments, keep a running tab of the following essential data on a separate piece of paper:

- Who. A list of people who will help you for your Key Personnel section later.

- What. A list of equipment and supplies for the experiments you plan.

- Time. Notes on how long each step takes. Timing directly affects your budget as well as how many Specific Aims you can realistically achieve.

Jotting this information down will help you Create a Budget and complete other sections later.

After finishing a draft Approach section, check that

- I include enough background and preliminary data to give reviewers the context and significance of my plans.

- They can test the hypothesis (or hypotheses).

- I show alternative experiments and approaches in case I get negative or surprising results.

- My experiments can yield meaningful data to test my hypothesis (or hypotheses).

- As a new investigator, I include enough detail to convince reviewers I understand and can handle a method. I reviewed the sample applications to see how much detail to use.

- If I or my team has experience with a method, I cite it; otherwise I include enough details to convince reviewers we can handle it.

- I describe the results I anticipate and their implications.

- I omit all information not needed to state my case.

- I keep track of and explain who will do what, what they will do, when and where they will do it, how long it will take, and how much money it will cost.

- My timeline shows when I expect to complete my aims.

If you are applying for a new application, include preliminary studies; for a renewal or a revision (a competing supplement to an existing grant), prepare a progress report instead.

Describing Preliminary Studies

Your preliminary studies show that you can handle the methods and interpret results. Here's where you build reviewer confidence that you are headed in the right direction by pursuing research that builds on your accomplishments.

Reviewers use your preliminary studies together with the biosketches to assess the investigator review criterion, which reflects the competence of the research team.

Give alternative interpretations to your data to show reviewers you've thought through problems in-depth and are prepared to meet future challenges. If you don't do this, the reviewers will!

Though you may include other people's publications, focus on your preliminary data or unpublished data from your lab and the labs of your team members as much as you can.

As we noted above, you can put your preliminary data anywhere in the Research Strategy that you feel is appropriate, but just make sure your reviewers will be able to distinguish it. Alternatively, you can create a separate section with its own header.

Including a Progress Report

If you are applying for a renewal or a revision (a competing supplement to an existing grant), prepare a progress report instead of preliminary studies.

Create a header so your program officer can easily find it and include the following information:

- Project period beginning and end dates.

- Summary of the importance of your findings in relation to your Specific Aims.

- Account of published and unpublished results, highlighting your progress toward achieving your Specific Aims.

Note: if you submit a renewal application before the due date of your progress report, you do not need to submit a separate progress report for your grant. However, you will need to submit it, if your renewal is not funded.

After finishing the draft, check that

- I interpret my preliminary results critically.

- There is enough information to show I know what I'm talking about.

- If my project is complex, I give more preliminary studies.

- I show how my previous experience prepared me for the new project.

- It's clear which data are mine and which are not.

References show your breadth of knowledge of the field. If you leave out an important work, reviewers may assume you're not aware of it.

Throughout your application, you will reference all relevant publications for the concepts underlying your research and your methods.

Read more about your Bibliography and References Cited at Add a Bibliography and Appendix .

- Throughout my application I cite the literature thoroughly but not excessively, adding citations for all references important to my work.

- I cite all papers important to my field, including those from potential reviewers.

- I include fewer than 100 citations (if possible).

- My Bibliography and References Cited form lists all my references.

- I refer to unpublished work, including information I learned through personal contacts.

- If I do not describe a method, I add a reference to the literature.

Look over what you've written with a critical eye of a reviewer to identify potential questions or weak spots.

Enlist others to do that too—they can look at your application with a fresh eye. Include people who aren't familiar with your research to make sure you can get your point across to someone outside your field.

As you finalize the details of your Research Strategy, you will also need to return to your Specific Aims to see if you must revise. See Draft Specific Aims .

After you finish your Research Plan, you are ready to write your Abstract (called Project Summary/Abstract) and Project Narrative, which are attachments to the Other Project Information form.

These sections may be small, but they're important.

- All your peer reviewers read your Abstract and narrative.

- Staff and automated systems in NIH's Center for Scientific Review use them to decide where to assign your application, even if you requested an institute and study section.

- They show the importance and health relevance of your research to members of the public and Congress who are interested in what NIH is funding with taxpayer dollars.

Be sure to omit confidential or proprietary information in these sections! When your application is funded, NIH enters your title and Abstract in the public RePORTER database.

Think brief and simple: to the extent that you can, write these sections in lay language, and include appropriate keywords, e.g., immunotherapy, genetic risk factors.

As NIH referral officers use these parts to direct your application to an institute for possible funding, your description can influence the choice they make.

Write a succinct summary of your project that both a scientist and a lay person can understand (to the extent that you can).

- Use your Specific Aims as a template—shorten it and simplify the language.

- In the first sentence, state the significance of your research to your field and relevance to NIAID's mission: to better understand, treat, and prevent infectious, immunologic, and allergic diseases.

- Next state your hypothesis and the innovative potential of your research.

- Then list and briefly describe your Specific Aims and long-term objectives.

In your Project Narrative, you have only a few sentences to drive home your project's potential to improve public health.

Check out these effective Abstracts and Narratives from our R01 Sample Applications :

- Application from Dr. Mengxi Jiang , "Intersection of polyomavirus infection and host cellular responses"

- Application from Dr. William Faubion , "Inflammatory cascades disrupt Treg function through epigenetic mechanisms"

- My Project Summary/Abstract and Project Narrative (and title) are accessible to a broad audience.

- They describe the significance of my research to my field and state my hypothesis, my aims, and the innovative potential of my research.

- My narrative describes my project's potential to improve public health.

- I do not include any confidential or proprietary information.

- I do not use graphs or images.

- My Abstract has keywords that are appropriate and distinct enough to avoid confusion with other terms.

- My title is specific and informative.

Previous Step

Have questions.

A program officer in your area of science can give you application advice, NIAID's perspective on your research, and confirmation that your proposed research fits within NIAID’s mission.

Find contacts and instructions at When to Contact an NIAID Program Officer .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

| and describe frequencies, averages, and correlations about relationships between variables |

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed-methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships

- Descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | relationships effect on a |

| Quasi-experimental | ) |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analyzing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study—plants, animals, organizations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

- Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalize your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.