You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Get More Zócalo

Eclectic but curated. Smart without snark. Ideas journalism with a head and heart.

Zócalo Podcasts

How Americans Fell in Love with the Open Road

As the automobile industry took off, drivers discovered the romance and freedom of long-distance travel.

By Peter J. Blodgett | August 13, 2015

In 1900, Americans were hampered by wretched roads and limited by the speed and endurance of the horses that powered buckboards, coaches, and wagons. If they had an urge to travel far distances, they had to rely upon the steam locomotive.

As fantastic as it might have seemed at the turn of the 20th century, the idea of supplanting the iron horse with the horseless carriage did catch the fancy of some intrepid men and women. Eager to test the technological limits of their new contraptions, a few hardy souls set off upon far-reaching expeditions between 1900 and 1910.

Colorado attorney Philip Delany, recounting his 1903 excursion from Colorado Springs to Santa Fe, observed, “and so the machine is conquering the old frontier, carrying the thudding of modern mechanics into the land of romance. . . .” Such travel meant seeing “the wildest and most natural places on the continent,” encountering more than a few hints of danger on steep and rocky mountain roads, and reliving the exploits of American pioneers. “The trails of Kit Carson and Boone and Crockett, and the rest of the early frontiersmen,” he declared, “stretch out before the adventurous automobilist.”

At the same time, some city dwellers simply sought an escape. Early 20th century urban environments had their drawbacks: sidewalks overflowing with scurrying pedestrians; streets crowded with unending waves of trolleys, delivery wagons, carriages, and pushcarts; the persistent stench rising from mounds of horse manure; raw sewage emptying into open gutters; rotting piles of uncollected garbage and dense clouds belching from factory smokestacks.

Upper-middle-class tourists motored through the countryside and then camped by the side of the road, finding the sentimentalized image of the gypsy or the tramp quite a compelling identity to assume. They reveled in their sense of independence from stodgy summer resorts and the tyranny of inflexible timetables set by railroads or steamship lines. They delighted in the beauty and serenity of unspoiled countryside. In the same article quoted above, Philip Delany observed that “when [the automobilist] is tired of the old, there are new paths to be made. He has no beaten track to follow, no schedule to meet, no other train to consider; but he can go with the speed of an express straight into the heart of an unknown land.”

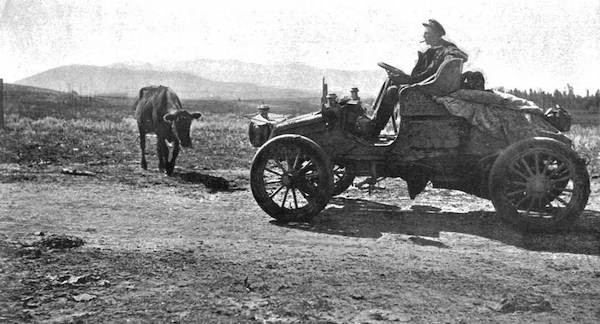

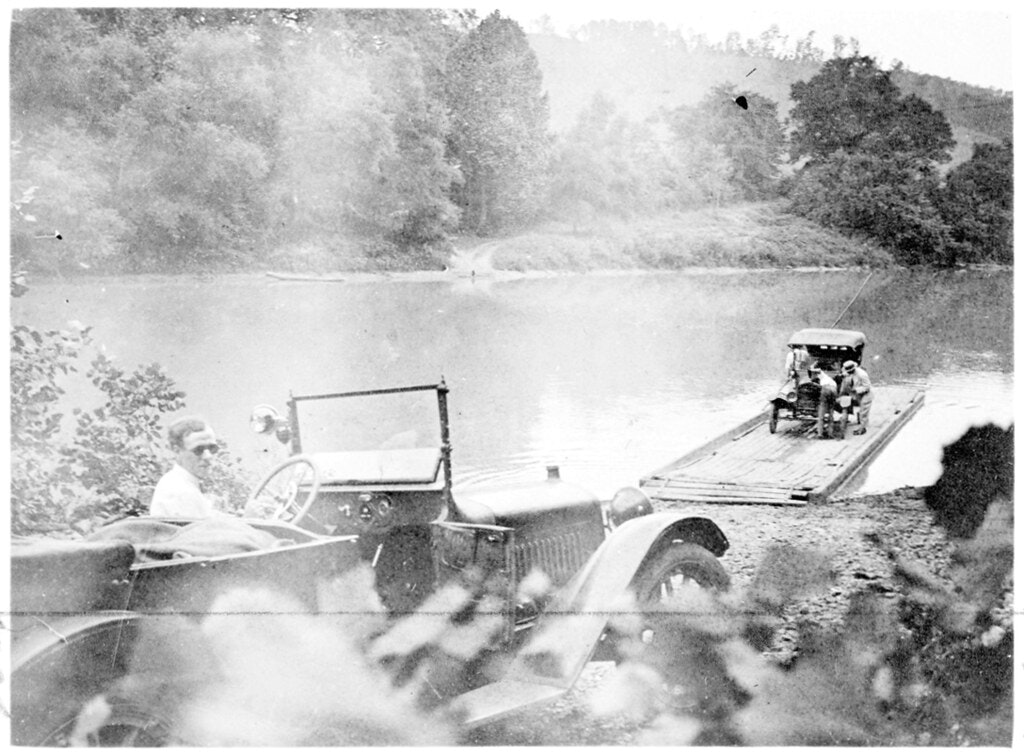

Photograph illustrating an article called “From Coast to Coast in an Automobile,” World’s Work, May 1904

In its infancy, however, an automobile could not deliver most Americans from their urban frustrations—for most Americans could not afford to own and operate one. At a time when average annual salaries might not reach $500, many automobiles might cost between $650 and $1,300, securely beyond the grasp of all but the wealthiest. Moreover, with few garages, filling stations, and dealerships outside of city limits, even the infrastructure required for the care and feeding of the automobile could be difficult to locate and could drain the motorist’s wallet. During their earliest years, neither automobiles nor auto touring could be considered within the reach of the masses. Automobility would only become pervasive over time, thanks to rising wages, falling prices for used cars, expanding opportunities to buy these machines on credit, and, especially, the introduction of Henry Ford’s revolutionary Model T in 1908.

Even for those Americans who could afford the first horseless carriages, to go off the few familiar paths in most parts of the country, especially in the great distances of the trans-Mississippi West, required a large measure of self-reliance. One motor traveler characterized the roads of his native Wyoming in 1909 as “deep ruts, high centers, rocks, loose and solid; steep grades, washouts, or gullies . . . ” He went on to note that, “unbridged streams; sand, alkali dust; gumbo; and plain mud, were some of the more common abominations.” Between the obstacles presented by such abysmal road conditions, the likelihood of frequent mechanical breakdowns, and the rarity of supplies to sustain driver and vehicle, these early outings always required an audacious spirit.

Aspiring long-distance auto tourists back then were counseled by self-proclaimed experts to carry abundant quantities of supplies. Those who made the first transcontinental drives between 1901 and 1908 hauled along ropes, blocks and tackle, axes, sleeping bags, water bags, spades, camps stoves, compasses, barometers, thermometers, cyclometers, first aid kits, rubber ponchos, tire chains, pith helmets, assorted spare parts, and sufficient firearms to launch a small insurrection. Mary C. Bedell’s impressive list of gear, published in her entertaining 1924 account of auto touring, Modern Gypsies , typifies what was carried by the most dedicated motor campers both in scale and variety: “tent, duffle bags, gasoline stove, Adirondack grate and a kit of aluminum kettles, with coffee pot and enamel cups and saucers inside”—an array of equipment that added “four or five hundred pounds” alone to the weight of the fully loaded automobile. A car so laden, puffing along western trails, bears a striking resemblance in the mind’s eye to a hermit crab staggering across the ocean floor burdened with its house on its back.

Even as motoring Americans loaded up their cars with the contents of their local hardware stores, however, the growth in their numbers year by year provided alluring prospects to entrepreneurs in small towns and great cities throughout the West. Garages, gas stations, roadside cafés, and diners began to pop up along more frequently traveled routes while hotels, restaurants, and general stores started to advertise in the earliest guidebooks produced by organizations such as AAA and the Automobile Club of America. Following the lead of Gulf Oil in 1914, gasoline retailers commissioned maps branded liberally with their logos for free distribution at their service stations. Motorists once left entirely to their own devices now encountered a rapidly evolving infrastructure of goods and services.

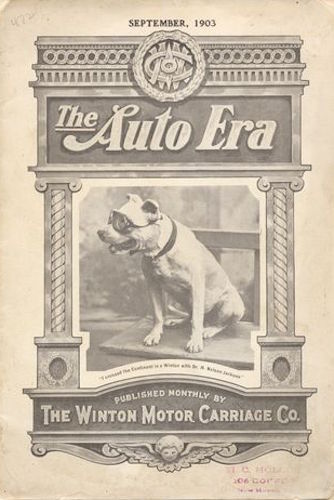

Cover of The Auto Era, featuring Bud the dog, a passenger on an early cross-country automobile trip

Meanwhile, governments at the local, state, and federal levels began to invest increased engineering skill, construction efforts, and tax dollars in road improvements. While motor tourists by the end of the World War I might still encounter 10,000 miles of battered gravel trails littered with potholes for every 10 miles of carefully surfaced and maintained roads throughout the country, the increasing pace of improvements made it far easier to drive through the West than it had been for those who had attempted such a journey only a decade before.

Although still new to the American scene by 1920, the road trip thus had begun to take on a shape familiar to modern eyes. Above all, the automobile was assuming a dominant role in popular recreation as more and more Americans incorporated it into their visions of recreation and leisure. As costs fell and reliability increased, as the successful outings of the few began to inspire the many, and as the thrill of this new technology spread through an ever-wider range of the populace, motoring for pleasure insinuated itself as a notion in the minds of many Americans. Indeed, less than a decade after the turn of the 20th century, author William F. Dix could assert that the automobile had become nothing less than a “vacation agent” for motor-savvy Americans as it “opens up the countryside to the city dweller, [and held out the promise of] great national highways stretching from ocean to ocean and from North to South.” Over those highways, he continued, “would sweep endless processions of light, graceful, and inexpensive vehicles . . . carrying rich and poor alike into a better understanding of nature and teaching them the pure and refreshing beauties of the country.”

While Dix fell far short as a prophet of social or technological developments, his sense of how inextricably linked the automobile would become in the leisure pursuits of Americans has been thoroughly borne out by the evolution of the American road trip.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

Song of the Open Road

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road, Healthy, free, the world before me, The long brown path before me, leading wherever I choose. …

Still here I carry my old delicious burdens, I carry them, men and women—I carry them with me wherever I go… … The black with his woolly head, the felon, the diseased, the illiterate person, are not denied; The birth, the hasting after the physician, the beggar’s tramp, the drunkard’s stagger, the laughing party of mechanics, The escaped youth, the rich person’s carriage, the fop, the eloping couple, The early market-man, the hearse, the moving of furniture into the town, the return back from the town, They pass, I also pass, any thing passes—none can be interdicted, None but are accepted, none but are dear to me.

Yes, Walt Whitman. Who could miss his catalogs of inclusiveness, with their unexpected yet spot-on details?

If you had read these lines to me without disclosing their source, I’d say “Song of Myself”—because that’s the poem best known for Whitman’s catalogs. But no, this is “Poem of the Open Road.” It’s not in the first (1855) edition of Leaves of Grass . But it does appear in the 1856 edition and thereafter—soon re-titled “Song of the Open Road.” (Whitman revised and expanded Leaves of Grass throughout his life: nine editions in all. I’ll be using the 1856 version of “Song of the Open Road,” because in general Whitman’s earlier versions are more spontaneous—more, well, Whitmanesque.)

It’s a longish poem of fifty-seven sections (though nowhere near the 372 sections of “Song of Myself”).

For this post, I want to hang out with “Song of the Open Road.” I wonder why. I think because I’m moved by its all-embracing spirit, and I like where the poem takes me. And maybe because, with COVID having kept me cooped up at home for so long, I need some expansiveness. And I need a celebration of the fresh air that I can finally breathe:

You air that serves me with breath to speak!

For Whitman, of course, just “breathing” the air isn’t enough. He has to picture how the air is empowering:

I think heroic deeds were all conceived in the open air, I think I could stop here myself, and do miracles…

One of the “miracles” is to be freed from all constraints:

From this hour, freedom! From this hour I ordain myself loosed of limits and imaginary lines…

Freely out on the open road, Whitman’s poetic persona apostrophizes the road itself. As always in Whitman’s catalogs, the delight is in the details:

You flagged walks of the cities! you strong curbs at the edges!… You gray stones of interminable pavements! you trodden crossings! From all that has been near you I believe you have imparted to yourselves, and now would impart the same secretly to me, From the living and the dead I think you have peopled your impassive surfaces, and the spirits thereof would be evident and amicable with me.

This is typical of Whitman’s poetic persona: that whatever he extols he takes into himself “amicably.”

Also typical is the eventual movement from the literal road out toward the transcendent, as his subject becomes the traveling “Soul”:

“ To know the universe itself as a road—as many roads—as roads for travelling Souls…

All parts away for the progress of Souls, All religion, all solid things, arts, governments—all that was or is apparent upon this globe or any globe, falls into niches and corners before the procession of Souls along the grand roads of the universe.

Those “grand roads of the universe”: to call Whitman’s persona expansive would be a colossal understatement (if that’s not an oxymoron). There’s evidently nothing and no one that he won’t exuberantly embrace:

Committers of crimes, committers of many beautiful virtues,… Habitues of many different countries, habitues of far-distant dwellings,…

Stately, solemn, sad, withdrawn, baffled, mad, turbulent, feeble, dissatisfied, Desperate, proud, fond, sick, accepted by men, rejected by men, They go! They go! I know that they go, but I know not where they go, But I know that they go toward the best—toward something great.

They go! As you’ve no doubt noted, traveling the open road releases, for Whitman, a spray of exclamation points. (I count sixty-three total in the poem.) Then about halfway through the poem, the exclamation point itself starts acting as a euphoric embrace of the reader, with sections beginning “Allons!” (“Let’s go!” “Come along!”). And with that invitation, the pronouns you-we-us join the poem’s previous I-me :

Allons! Whoever you are, come travel with me! Traveling with me, you find what never tires.

The “Allons!” invitation is cried out repeatedly through the rest of the poem, which ends with what I hear as a climatic clashing of cymbals in this final, wildly fun catalog—of what the open road calls us to leave behind:

Allons! Be not detained! Let the paper remain on the desk unwritten, and the book on the shelf unopened! Let the tools remain in the workshop! let the money remain unearned! Let the school stand! mind not the cry of the teacher! Let the preacher preach in his pulpit! let the lawyer plead in the court, and the judge expound the law.

And then the final verse: Mon enfant! I give you my hand! I give you my love, more precious than money,

I give you myself, before preaching or law; Will you give me yourself? Will you come travel with me? Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?

My coda: Actually, I’d say that we stick by Whitman long after he lived. Through his poems like this one.

Peggy Rosenthal has a PhD in English Literature. Her first published book was Words and Values , a close reading of popular language. Since then she has published widely on the spirituality of poetry, in periodicals such as America , The Christian Century , and Image , and in books that can be found here .

My Liberation

Wallace Stevens’s “The Death of a Soldier”: History in a Poem

The Grace of Accuracy: Robert Lowell and the Structure of Illumination

Mixing and Matching in Ann Patchett’s “Commonwealth”

Poem Appreciation: Song Of The Open Road

Writing an appreciation of Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” requires a deep dive into the poem’s thematic essence, its stylistic features, and the emotional resonance it holds. The poem is an embodiment of freedom, a reflection on life’s journey, and a celebration of the individual’s quest for meaning. To craft a comprehensive appreciation, one must consider several critical aspects that make the poem stand out as a seminal work in American literature.

Table of Contents

Understanding Thematic Elements

“Song of the Open Road” is rich in themes that are both personal and universal. Freedom, adventure, individualism, and democracy are just a few of the poem’s central ideas. An appreciation should consider how Whitman explores these themes and their relevance to the reader’s life. The open road as a metaphor for life’s journey suggests that the path to self-discovery is open and accessible to all.

Analyzing Stylistic Features

Whitman’s use of free verse is revolutionary and reflects the poem’s core message of liberation. Unlike the structured verse of his contemporaries, Whitman’s poem flows freely, mirroring the unrestricted nature of the open road. Appreciating this poem involves acknowledging how the form complements the content—how the sprawling lines and the lack of rhyme scheme invite the reader into an experience free from traditional constraints.

Exploring the Poet’s Language

Whitman’s language is direct, robust, and inclusive. His use of repetition and anaphora, particularly in the opening lines, creates a rhythm that echoes the movement of traveling. In your appreciation, explore the impact of these poetic devices and how they contribute to the poem’s immersive quality. The language should be seen as a conduit that transports the reader alongside Whitman on his journey.

Imagery and Sensory Experience

Whitman’s vivid imagery and sensory language are pivotal to the poem’s effectiveness. He doesn’t just tell the reader about the open road; he shows it through evocative descriptions of the landscape, the sky, and the sounds and scents of nature. An appreciation should delve into how these images create a multisensory experience and how they enhance the poem’s appeal.

Philosophical and Reflective Undertones

The poem goes beyond a mere celebration of travel; it is a philosophical reflection on life and the interconnectedness of humanity. Whitman’s democratic vision, where every individual’s journey is valued, is a profound aspect that merits attention. Discuss how “Song of the Open Road” challenges readers to consider their place in the world and their relationship with others.

Connecting with the Reader

A significant aspect of the poem is its ability to connect with readers across time and space. Whitishman’s inclusive language and universal themes speak directly to the reader, creating a sense of camaraderie. Your appreciation should consider the poem’s emotive power and its capacity to inspire a sense of adventure and longing for freedom.

Historical and Cultural Context

Understanding the historical and cultural context in which Whitman wrote can add depth to an appreciation. The poem was published in the mid-19th century, a time of great change and optimism in America. Consider how the spirit of the era—the expansion westward and the belief in the American Dream—influences the poem’s tone and message.

Personal Reflection

Lastly, an appreciation is a personal response to the poem. Reflect on how “Song of the Open Road” resonates with you. What emotions does it evoke? How does it inspire you to think about your own life’s journey? Incorporate your personal engagement with the poem to give your appreciation a unique and authentic voice.

In concluding your appreciation, summarize the poem’s enduring impact. Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” is an invitation to embrace life’s journey with all its uncertainties and delights. It is a timeless piece that encourages the reader to seek out their path, to find joy in the journey itself, and to recognize the intrinsic freedom that lies within the open road and within themselves.

Song of the Open Road Appreciation Example

“Song of the Open Road”, a poem by Walt Whitman, is an iconic piece that encapsulates the essence of freedom, individuality, and the journey of life. Whitman, renowned for his contributions to American literature and his unorthodox style in the canon of poetry, presents a piece that resonates with the spirit of adventure and the quest for self-discovery. This appreciation seeks to explore the profound themes, stylistic devices, and emotive power of “Song of the Open Road” and its celebration of the vast, unfolding paths of possibility.

Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” emerges from the pages of “Leaves of Grass”, his seminal work, and stands as a resonant call for liberation from societal constraints and an embrace of the boundless opportunities that life offers. The poem is an ode to the journey more than the destination, a theme that is quintessentially American in its valorization of the frontier and the belief in progress and self-reliance.

At the heart of the poem is the theme of freedom—freedom not only in the physical sense of exploring the open road but also in the psychological sense of casting off the shackles of societal expectations and norms. Whitman invites readers to join him on a journey that promises liberation and self-exploration. His invitation is not just to travel physically but to embark on a path of personal growth and transformation.

The “open road” is a powerful symbol in Whitman’s poem, representing the uncharted territory of one’s future and the myriad paths one can choose in life. It stands as a metaphor for personal autonomy and the existential journey each individual must undertake. The allure of the open road lies in its uncertainty and the promise of adventure, themes Whitman masterfully weaves into the fabric of the poem.

Whitman’s stylistic choices in “Song of the Open Road” are as important as its thematic content. His use of free verse is revolutionary, breaking away from the strict metrical patterns and rhyme schemes that dominated poetry of the time. This stylistic liberation mirrors the content of the poem itself, emphasizing the freedom that the open road symbolizes. The poem’s structure is sprawling and open-ended, with varying line lengths and a conversational tone that invites the reader into an intimate exchange.

The language of the poem is another aspect that deserves appreciation. Whitman employs a direct and robust diction that is at once commanding and inviting. His repetitive use of the first person creates a sense of solidarity with the reader, while the anaphora of “Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road…” reinforces the exhilarating rhythm of the journey. The poet’s language is imbued with a sense of optimism and potential, qualities that are infectious and inspiring.

Whitman also makes use of vivid imagery and sensory language to draw the reader into the experience of the open road. His descriptions of the landscape, the sky, and the scents and sounds of the environment serve to immerse the reader in the sensory richness of the journey. The poem becomes not just a reading experience but a vicarious voyage through Whitishman’s America, with its diverse people and sprawling vistas.

The poem’s philosophical undertones add depth to its celebratory tone. Whitman explores the interconnectedness of all individuals and the universal journey of life. He champions the idea that each person is part of a larger whole and that the open road is a shared experience, a common ground where all walks of life converge. This democratic vision reflects Whitman’s belief in equality and his hope for a society where all individuals are free to pursue their own paths.

In conclusion, Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” is a rich and evocative poem that speaks to the universal human desire for freedom and adventure. Its thematic depth, coupled with Whitman’s innovative style and use of language, makes it a work that continues to inspire and resonate with readers today. As an appreciation of the poem, it is clear that “Song of the Open Road” is not just a celebration of travel and exploration but a profound meditation on life, individuality, and the pursuit of happiness. It is a testament to the enduring power of poetry to encapsulate the human spirit and its eternal yearning for unfettered existence.

Final Thoughts

Crafting an appreciation of “Song of the Open Road” is an exercise in understanding Whitman’s vision and translating that understanding into a thoughtful and emotive response. By exploring the poem’s themes, style, imagery, and philosophical underpinnings, you not only delve into Whitman’s world but also invite others to join you on the open road of poetic discovery.

About Mr. Greg

Mr. Greg is an English teacher from Edinburgh, Scotland, currently based in Hong Kong. He has over 5 years teaching experience and recently completed his PGCE at the University of Essex Online. In 2013, he graduated from Edinburgh Napier University with a BEng(Hons) in Computing, with a focus on social media.

Mr. Greg’s English Cloud was created in 2020 during the pandemic, aiming to provide students and parents with resources to help facilitate their learning at home.

Whatsapp: +85259609792

[email protected]

- Collections

- Support PDR

Search The Public Domain Review

American Freedom Sinclair Lewis and the Open Road

By Steven Michels

Some three decades before Kerouac and friends hit the road, Sinclair Lewis published Free Air , one of the very first novels about an automobile-powered road trip across the United States. Steven Michels looks at the particular vision of freedom espoused in the tale, one echoed throughout Lewis' oeuvre.

March 22, 2017

Sinclair Lewis at the wheel of his automobile, ca. 1920s — Source .

Sinclair Lewis is experiencing a renaissance of late — but not for a reason he would have liked. His 1935 novel, It Can’t Happen Here , depicts an authoritarian American president, whose rise and rhetoric very much resemble the current commander in chief.

Criticized at the time for making American fascism sound too European, Lewis’ prescience is remarkable. Eschewing the conservative fear of moral and cultural relativism, the libertarian fear of a regulatory state, and the progressive fear of economic elites and corporations, Lewis follows Plato in pointing to democracy itself as the cause for the slide to tyranny. It Can’t Happen Here , like The Republic , shows how someone elected to satisfy the severe passions of the mass can quickly run afoul of legal norms and institutions.

Lewis’ most affirmative vision of what he means by freedom is found in his novel Free Air , which was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in the spring of 1919, the year before Main Street and Babbitt made him a household name. Free Air is the story of two young people, Milt and Claire. Milt is a small-town mechanic and garage owner, and Claire is from Long Island and in the middle of a coast-to-coast trip to Seattle with her father. Like many Northeasterners, Claire believes that the rest of the country is filled with folks who are good but simple. Milt knows better. He had been plotting an escape from its dreary doldrums, but is enthralled with Claire when she comes through town, and he ends up following her and her father on their journey west. Claire quickly falls for the heartiness of the outdoors, even though she sees Milt more like a brother than a romantic partner. “There is an America!” Claire cheers by her tent, after she and Milt forgo her usual hotel. “I’m glad I’ve found it!”

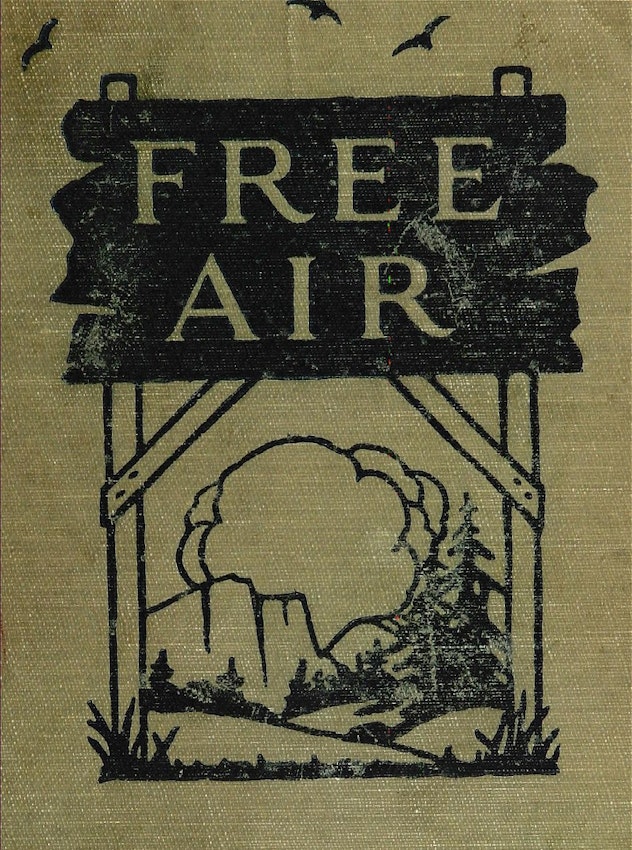

Cover illustration for Free Air (1919) — Source .

Once they get to their destination, however, they discover that everyone is obsessed with “the View” and ranks houses accordingly. What’s worse is that everyone builds and buys from the assumption that houses ought to resemble the East Coast as much as possible. Milt and Claire were looking for something unique and interesting, but instead find a stale sameness and imitation. The book ends with the couple heading back on an open-ended road trip. It might be, Lewis suggests, the only place where they are unburdened by society and its conventions enough to be together.

Free Air is not kind to the petty and conniving rural dwellers, but Lewis’ most devastating take on small-town life appears in Main Street . Lewis, a product of Sauk Centre, Minnesota, rails against the idea that these remote burgs are the source of all that is good. Rather, they infect their residents with “the village virus”, symptomized by a firm ignorance, self-satisfaction, and general intolerance of anyone who doesn’t look or think like they do. Will Kennicott loves weekend driving, but he never gets too far out of town. All the roads he takes lead him back to Gopher Prairie.

Picture of Sinclair Lewis at the wheel, published in The World’s Work (1921) in a piece celebrating the bestseller success of Main Street — Source .

That’s not to say that Lewis touts cities as unqualifiedly good. What is gained by their cosmopolitan sensibility, culture, and good food is lost in a lack of intimacy and familiarity. There is a reason Claire and her exhausted father had left the East Coast. It’s easy and hard in different ways. “We need to know men like that in this pink-frosting playing at living we have in the cities”, she says to an aristocratic suitor, in defense of Milt’s working-class father. The Innocents , the novel Lewis wrote before Free Air , follows the long-married Applebys as they leave New York City to open a tea room in the quiet country. It’s a rare soul that can reside in a city and not be corrupted by it.

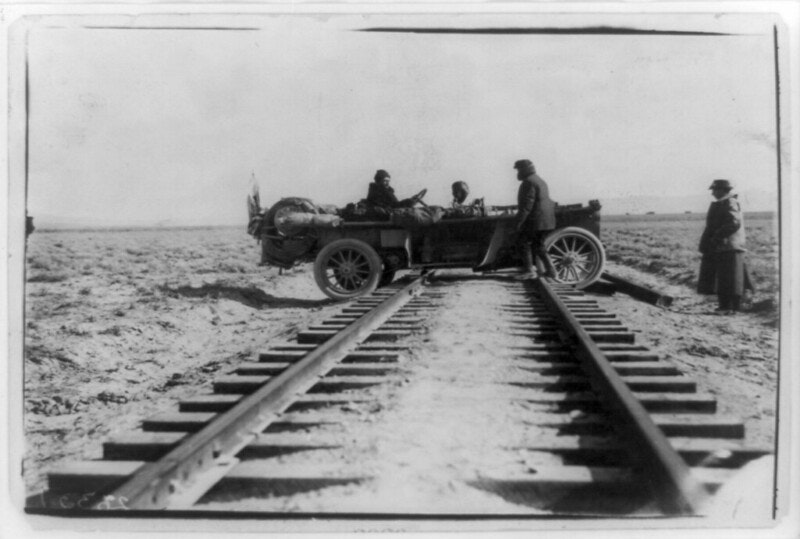

This is not just about travel; for Lewis, it is about positive freedom and control. He never presents train travel as especially desirable, constrained as it is to tracks, and his early love of planes is directed at those who can fly them. Americans are rightful captains and pilots, not passengers or spectators. He would have agreed with Thomas Wolfe, who, in You Can’t Go Home Again , posited: “Perhaps this is our strange and haunting paradox here in America — that we are fixed and certain only when we are in movement.” It is only when Wolfe’s protagonist George Webber arrives at a destination, that he feels a sense of homelessness. The expansive country and its prairie makes motion the most natural and comfortable condition.

Automobile straddling railroad tracks during a race between New York and San Francisco in 1908 — Source .

Business travel provides both an opportunity and a threat. On the one hand, people who travel for work go through small towns and bring with them information and a perspective about the world outside. Milt is much improved by his time with them. Yet as “missionaries of business”, theirs is a hollow gospel. Business also provides opportunities for independence. Una Golden, Lewis’ protagonist in The Job , moves from a small town in Pennsylvania to New York and uses her business acumen to make a decent life for herself, which for a woman at the time was no small feat. Yet George F. Babbitt and his clique travel to cheat on their wives and expand their bourgeois lifestyle.

Lewis loves America for its individualist philosophy and its pioneer spirit. For him, progress is more about exploring than putting down roots and putting up buildings. Growth is a matter of psychology, not economics. The eponymous anti-hero of Our Mr. Wrenn has to go off to Europe to gain some perspective on his workaday routine. “Adventure, like fear of adventure, consisted in going one step at a time, keeping at it, forming the habit . . . ” Lewis instructs. He operates from a grand and romantic vision of what our expansive territory has made possible, and he worries that we have squandered too much of our good fortune.

Lewis lived his nomadic philosophy — moving from Minnesota to New Haven for school, through New York City, D.C., and with stints in Europe, never in one location for very long and often returning to the same place. “It’s always easier to be a bold adventurer in some town other than the one in which you are”, Lewis writes in The Innocents . His perception of and even his fondness for his native land grew during the time he lived in Europe. “No American, if he can help it, dies in his birthplace”, he wrote. Of course, that did not prevent him from being buried in his hometown.

Sinclair Lewis’ boyhood home, the family posing on the porch, ca. 1900. “Harry Sinclair” (his full name) is sat far right — Source .

Among Lewis’ gifts are his willingness to probe the essential tension at the heart of American moral and social life. It’s a land of boundless opportunity and fierce competition; it’s also a land of individualism that too easily bends toward conformity. Who else could have said: “Intellectually I know that America is no better than any other country; emotionally I know she is better than every other country”? Lewis understands both sides of American exceptionalism. How much better would the country be if it had more of that kind of patriotism.

In some respects, Lewis’ extreme form of freedom could be said to resemble what you find in Rousseau’s “state of nature”, where individuals are untethered by property or people. But Lewis never advocated solitude and he was too much a fan of progress. Two of his early books, Hike and the Aeroplane and The Trail of the Hawk , take the new technology of aviation as their themes. Lewis saw air travel as a modern form of daring, and he held out great hope for what it could do for the American psyche.

There are, however, some interesting parallels between Lewis and the road’s other great prophet, Jack Kerouac. Lewis would certainly approve of Kerouac’s discipline and stream-of-consciousness method. Kerouac is said to have written On the Road in three weeks on a 1200-foot scroll of teletype paper. Lewis, after doing his research, could write 3000-5000 words a day.

For Lewis, however, writing was more about self-improvement than self-expression. He wanted a kind of noble and pioneering freedom and would judge other modes accordingly. He would see Kerouac as a hedonist. Nor did Lewis tout the virtues of alcohol or drugs. He reflects on “the torture of being bored by the two-frequent presence of his own self”, in Cass Timberlane, one of Lewis’ more mature characters. It was the reason Lewis drank, even though he recognized it as a temporary cure. He was, by many accounts, a problem drinker. Self-doubt is a prerequisite for improvement, but it too has its risks. Sometimes the greatest obstacles to freedom are not other people, but ourselves.

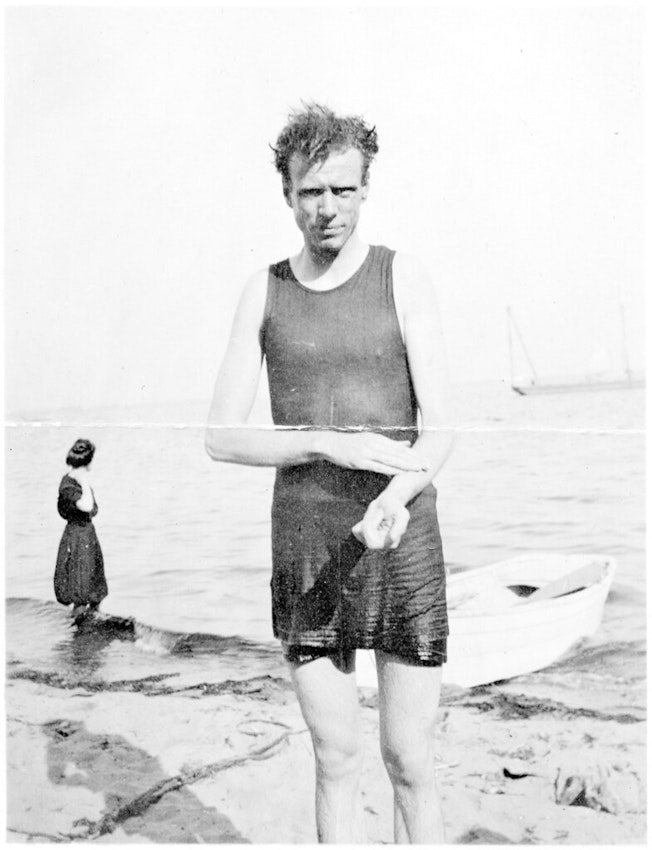

Sinclair Lewis by the sea, ca. 1920s — Source .

Most importantly, Lewis’ moralism was utterly conventional. Although one of the more prominent subtexts of his novels is the extent to which moralists are all hypocrites, he is equally bothered by anyone who operates without a compass of any kind. For instance, there is a rawness and physicality in Kerouac that Lewis would likely have found off-putting. Kerouac’s sex scenes are tame by today’s standards, but they were risqué enough at the time to have been edited by his publisher. Lewis’ sex scenes are ridiculous. Sometimes it’s not even clear what has happened — what might be called coitus obscurus .

Lewis’ greatest gifts as a novelist were his abilities of perception and mimicry. For the first part of his life, Lewis wanted to be in theater and would regularly delight others with his character portraits and impressions. As a political writer, his greatest asset was his ability to present what he observed without the filter of his own ideology. He was not an activist and not terribly political. It didn’t exactly make him a great citizen, but it made a superior novelist. He had a reporter’s sensibilities, which is why he made a newspaper man, Doremus Jessup, the protagonist of It Can’t Happen Here , his most political novel.

It’s not a stretch to say that he is among the best writers on democratic freedom. More than anyone, Lewis understands its aims and its limitations for both individuals and the country. For him, freedom is playful but serious, directionless but purposeful, and essential to knowing true happiness. Lewis sees that kind of freedom as America’s greatest virtue and best export. It would be tragic if we were to somehow lose it.

Public Domain Works

- Internet Archive

- Internet Archive 1906 English edition

- Internet Archive 1761 English edition

Further Reading

A cautionary tale about the fragility of democracy, it is an alarming, eerily timeless look at how fascism could take hold in America.

An examination of each of Lewis’s novels on key themes in the history of political thought and democracy including freedom and purpose, success and materialism, and nationalism and race.

The Public Domain Review receives a small percentage commission from sales made via the links to Bookshop.org (10%) and Amazon (4.5%). Thanks for supporting the project! For more recommended books, see all our “ Further Reading ” books, and browse our dedicated Bookshop.org stores for US and UK readers.

Indexed under…

- Freedom and the open road

- Vehicles and freedom

Steven Michels is professor of political science at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, CT and the author of Sinclair Lewis and American Democracy . Visit his personal website or follow him on Twitter .

The text of this essay is published under a CC BY-SA license, see here for details.

If You Liked This…

Get Our Newsletter

Our latest content, your inbox, every fortnight

Prints for Your Walls

Explore our selection of fine art prints, all custom made to the highest standards, framed or unframed, and shipped to your door.

Start Exploring

{{ $localize("payment.title") }}

{{ $localize('payment.no_payment') }}

Pay by Credit Card

Pay with PayPal

{{ $localize('cart.summary') }}

Click for Delivery Estimates

Sorry, we cannot ship to P.O. Boxes.

Leaves of Grass

by Walt Whitman

Leaves of grass summary and analysis of "calamus," "song of the open road," and "crossing brooklyn ferry".

Whitman begins “Calamus” in September, 1859, alone in the woods, away from all of the “pleasures, / profits, conformities” of his life. It is in this place that he can reflect on his inner self. This is a truer self than the one of the ordinary world. He resolves to “sing no songs to-day but those of manly / attachment….” It is a celebration of his own “need of comrades.” This time is also a time of reflection on the end of life. In “Scented Herbage of My Breast” he ponders leaves that grow above him. They are leaves of death and they are bitter, but this does not mean that death is not beautiful. Whitman says, “Death or life I am then indifferent, my soul declines to prefer….” Death is beautiful when a man does not live his life in service to it. Instead, Whitman is decisive in his wish to “make death / exhilarating” for his comrades and fellow travelers.

In “For You O Democracy,” Whitman makes the connection between America, the “continent indissoluble” and the friendship of which he sings. His goal is to create companionship in all of America. Cities will be filled with men bonded together in “manly love.” As he wanders through the woods, Whitman can feel the spirits of his former friends beside him. Some embrace him while others stand around him. Whitman begins to pick up “tokens” of nature around him: a lilac, a pine branch, “some moss…pull’d off a live- / oak in Florida as it hung trailing down,” some laurel leaves and some water from the pond. Whitman says that these are held near to him “by a thick cloud of spirits….” In “Of the Terrible Doubt of Appearances,” Whitman speaks not of spirits but of real people, lovers with whom he travels. They hold his hand and sit with him and there is a sense “that words and / reason hold not….” Whitman gains his wisdom from these moments and from this love. The questions of life and death fade away.

In “The Base of All Metaphysics,” Whitman attempts to give a philosophical answer to the ideas of love and companionship that he writes about here. He imagines a college course, taught by a professor. The class studies all of the great philosophers of the world from Socrates to Christ to Hegel. All of these philosophies, Whitman says, are undergirded by “The dear love of man for his comrade, the attraction of friend / to friend….” Whitman hopes that it is this kind of “measureless….love” within him that will be the thing he is remembered for. He calls on his future biographers and recorders of history to note not his “songs” but his love for his friends.

It is only this love that can make Whitman happy. “When I Heard at the Close of the Day” is a reflection on this happiness. Whitman recalls the time he was honored in the capitol and a time when he “carous’d” and when his “plans were / accomplish’d,” yet he says still he is not happy. He is happy when he is in nature, rising with the sun, bathing in the ocean, and thinking of his dear friend, his lover, and how he is on his way over to see him. Whitman says that he is only happy when his arm is around his friend, when they lay together sleeping “In the stillness in the autumn moonbeams….”

Whitman sings a song for his beloved New York in “City of Orgies.” Manhattan is a city of “walks and joys” and Whitman sings his songs within the city and about it. What makes the city “illustrious” is not its buildings, homes, streets, or commerce. It is, instead, the love that the inhabitants of the city have for Whitman and the love that he shares with them. He sings of one particular New Yorker in “Behold This Swarthy Face,” who comes up and kisses him “lightly on the lips with robust love….” This is an act of robust love and this is a love that is saluted all over America. In “To a Stranger,” Whitman observes someone walking down the street and thinks that he must have known this person in some other time. This person gives him pleasure even though he does not know him. He is sure that he will meet this stranger again and that he will not lose this person again.

In a quiet moment, sitting alone, Whitman thinks of all the other men in the world sitting alone, “yearning and thoughtful.” Whitman believes that if he could only know these men, he would become as “attached to them as I do to men in my own lands….” He yearns to be brothers with these men; to be happy with them. Whitman then responds to those that charge him with seeking “to destroy / institutions.” He says that this is not his goal. Instead, he seeks to build up the institution of manly love in all the cities of the nation. Whitman says he does not envy important men – generals or the President or any rich or powerful person. Instead, he envies the “brotherhood of lovers” and those that maintain manly love throughout their lives.

Whitman makes “A Promise to California.” He tells California that he will soon go West because he knows that “I and robust love belong among you.” First, however, he rejoices in his love of “a youth who loves me and whom I love.” This youth comes to him in a crowded bar-room and holds his hand at a table. While others drink and swear, Whitman and his love speak little, “perhaps not a word” and enjoy being in silence with each other. He is not only smitten with this youth, however, but with all of the people of the nation. He longs to “infuse” himself amongst the workers and the blue-collar people of the land. In a dream, Whitman sees a “new city of Friends,” a place not of this earth. In this city, nothing is greater than equality and love.

In “To the East and to the West,” Whitman proclaims, “I believe the main purport of these States is to found a superb / friendship, exalte” that is unknown in any other time or place. While in “Among the Multitude,” Whitman says he can feel one “picking me out by secret and divine signs.” This person knows him and is his lover, his “perfect equal.” For his own part, he feels a “subtle electric fire” when he is near this lover. Whitman ends “Calamus” by claiming he is “Full of Life Now.” He speaks to past and future generations who will read these words and wish they could be his lover and tells them that through these words they can be certain that he is with them.

“Song of the Open Road” is Whitman’s celebration of travel. He takes to the road “A foot and light hearted…Healthy, free, the world before me….” He is free to choose where he goes. Whitman feels as though he embodies his own journey. He is good fortune and does not need to ask for it. “Strong and content I travel the open road.” He proclaims that the world around him – the earth and the constellations – come with him yet they do not have to support him.

To travel is to be free above all. Whitman “ordains” himself “loos’d of limits and imaginary lines….” He is, in the most real sense, master of his domain. He claims that he will listen to others, hear their words, but in the end he is divested “of the holds that would hold me.” Whitman even amazes himself. “I am larger, better than I thought / I did not know I held so much goodness.” Whitman seeks to give this goodness back to the world since the men and women of the world have done good to him while on his journey. Whitman proclaims that he will “scatter” himself amongst all people as if he were seed. If someone should deny him, he will not be troubled. If they accept him, and bless him, Whitman will reciprocate the reception and the blessing.

Whitman also has words of encouragement for his fellow travelers. He understands the journey, oftentimes, is difficult. “The earth is rude, silent, incomprehensible at first….” He tells the traveler to “Be not discouraged, keep on, there are divine things well envelop’d….” He asks his fellow reader and traveler not to be convinced of this by “arguments, similes, rhymes” but to be convinced simply by Whitman’s own presence. Whitman assures his companion that all things of humankind – governments, religions, institutions - fall “into niches and corners before the procession of souls along the grand road.” The journey is always towards “something great.”

In “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Whitman takes on the stance of observer. Around him, he sees “Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes” and they are “curious” to him. They are on the hundreds and hundreds of ferry boats that cross between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Whitman sees all of them, and himself, as “disintegrated yet part of the scheme….” He sees that others will follow him, others will watch these people and these boats cross, fifty or even a hundred years, they will “enjoy the sunset, the pouring-in of the flood-tide, the / falling-back to the sea of the ebb-tide.”

Whitman tells the “many generations hence” that he is with them. “Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd.” These future generations can trust that their experiences are the same as his own. Their observations of the beauty of the natural world around them are the same as his own. He wants these future people to know that he loved the cities, the rivers, and all the men and women that crossed between them. Whitman asks what it is between he and the future generations. “Whatever it is, it avails not – distance avails not, and place / avails not….” The “abrupt” questions that these future people feel, he also felt them. Whitman exhorts the river to “Flow on! Flow with the flood-tide,” and for the “masts of Mannahatta” to “Stand up, tall….” He asks the reader to consider that he himself might be looking back in some “unknown / ways….”

The sexual nature of Leaves of Grass was fodder for great controversy during Whitman’s own life. Several high profile critics, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, found these themes less than desirable in the book. Whitman lost his government job in 1865 because his boss read his work and dismissed him for indecency. Through all of this, however, Whitman maintained that sexuality was vital to his own work precisely because it is a vital characteristic of the human experience. Sexuality was not just an individual experience between two people according to Whitman; it was a foundational experience for how society is woven together.

“Calamus” is a reflection on male friendship and relationship. The name “Calamus” refers to an ancient Greek myth -- Calamus was a man who grieved for his young male lover and turned into a reed. That Whitman sees this friendship in erotic terms only shows the multiplicity of ways in Whitman understood true relationship. While much has been made of Whitman’s use of homosexual imagery, a sexual viewpoint that was not widely talked of nor published during Whitman’s day, the reader cannot overlook the fact that in previous sections, including “Song of Myself,” Whitman makes use of autoerotic and heterosexual imagery as well. This is what scholars have noted as Whitman’s omnisexual viewpoint. No one sexual preference is complete for Whitman. Sexuality must include preference for the individual, for the different, and for the same.

The first poems of “Calamus” see Whitman reevaluating some of the themes from previous sections, especially his understanding of the natural world. If the child’s poem from “Song of Myself,” in which the child brings a handful of grass to Whitman in order to ask what it is, is instructive of Whitman’s understanding of humanity’s relationship with the natural world, than “Calamus” represents a break with that understanding. Whitman begins in nature, observing the trees and the leaves around him, yet he does not feel a part of it. There is death and life in those leaves, he understands, but this does not seem to be as vital to him as it did before. Instead, he is infused with the desire for friendship. This is also a reevaluation of the Romantic spirit in American literature. While previous poets and writers, taking cues from their European forebears, found a true spirituality in the mysteries of nature, Whitman finds that he cannot find the true self in nature alone. Truth is only to be found in the bonding of men.

Whitman’s historical context is also important for understanding this section of the book. This is one of the only poems in the book in which Whitman gives a specific date for reference, 1859. It is notable that this is the same year that Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species was published. As the classic text on the theory of evolution, Darwin’s book is considered to be revolutionary in the fields of biological science. The theories that Darwin put in print, however, were already widely discussed in intellectual circles of Whitman’s day. In science and psychology (whose original manifestation was phrenology, a discipline which Whitman studied), there was a growing understanding that sexuality was a trigger for all biological actions and interior feelings.

Whitman sought to take this understanding from the scientific disciplines and make it relevant to the philosophical and literary disciplines. This is the best reading of “The Base of All Metaphysics.” Whitman’s reading of the great philosophers and religious leaders is not materialist in any way. Instead, Whitman understands the basis of all life as the interwoven relationships between people. His own songs are but manifestations of this love between friends. This love is manifested in “When I Heard at the Close of the Day.” This is a poem of consummated love between Whitman and his male friend. Through this act of sexual consummation, both also are consummated with nature suggesting that the relationship between men that Whitman experiences is the root of an equilibrium between all natural things.

The reader, however, cannot only read “Calamus” as an expression of carnal lust and base desire. The ending gives a correction to any who might do so. The last poems of the section take on a social dimension. While the first poems exemplified a deep and personal love, Whitman equates this personal, sexual love with the social love that he shares for all people. He thinks of all the men that he could be friends with and decides that he is united with them. He promises California that he will come and visit and envisions being united with all the working men and women of land. By the end of “Calamus,” the reader understands that the sexual impulse is, in reality, a democratic impulse.

In “Song of the Open Road,” Whitman moves from an individual perspective to what we today might consider a global perspective. This is a broadening of his subject from previous poems. While Whitman has claimed in previous verse to be singing a song of America, in Song of the Open Road he shows that all people of the earth are in his purview and that his teachings can be understood beyond the democratic states. While the United States has been built as a country on the concept of freedom, Whitman wants his readers to understand that there is a strong urge of the individual that is present within the concept of freedom. Whitman cannot be tied down to the difficulties of the earth, to institutions or rules. To be free means that one loses the constraints of these old things and Whitman offers himself as the best example. His imagery of scattering seed is a metaphor for planting and for impregnating the imagination with his teachings.

If “Song of the Open Road” is a an ode to individuality, “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” is Whitman’s expression par excellence of the collective. “Brooklyn Ferry” features two characters – Whitman and You, the reader. The poem begins descriptively but, by the end of the first section, has introduced a conversational tone between Whitman and the reader. There is a personal dimension to the conversation and the setting seems to be more private than in previous poems addressed to a wide audience. Whitman balances an understanding of the reader as a close and personal friend, the kind of erotic relationship he described in “Calamus,” yet also a friend spread across time and space.

A central meaning to the poem is elusive except to say that, in watching the crowds cross Brooklyn’s river, Whitman is reminded of the fact that all things he experiences have been and will be experienced by all others. Whitman uses images of the world – rivers and suns, crowds and individuals – all as part of a larger “scheme.” These things have been placed within the poet and he understands that they will also be placed inside of the reader. In this way, Whitman knows that he has gained a spiritual unity with the world and with those that came before and will come after. This theme was important to many of the New England Transcendentalist writers and poets of the nineteenth century. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famous essay Nature is, perhaps, the best example. Where Emerson sought to find a divine, unifying spirit in the natural world, however, Whitman finds it in the crowds of New York.

Leaves of Grass Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Leaves of Grass is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

In Walt Whitman's "From Song of Myself," what parts of the poem show the use of metaphor? Cite examples from the poem.

Whitman uses the metaphor of grass in the sixth section of “Songs of Myself” to try and explain the democratic self. His explanation, he admits, is incomplete. Whitman describes a child coming to him and asking him what is the grass. He has no...

Whitman first began writing Leaves of Grass after failed attempts at newspaper publishing and teaching.

what is the image of woman in leaves of the grass?

Which particular poem are you referring to?

Study Guide for Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass study guide contains a biography of Walt Whitman, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Leaves of Grass

- Leaves of Grass Summary

- Character List

Essays for Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

- Reconciling Disparate Objects in "Leaves of Grass"

- The Thrust of Nature: An Examination of Walt Whitman's Poetic Realm

- Philosophical Parallels in Plato's Meno and the 1855 Leaves of Grass

- Homoeroticism in Leaves of Grass

- Walt Whitman: The Center of the American Literary Canon

Lesson Plan for Leaves of Grass

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Leaves of Grass

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Leaves of Grass Bibliography

E-Text of Leaves of Grass

Leaves of Grass e-text contains the full text of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman.

- Introduction

- Book I: Inscriptions

- Book II: Starting from Paumanok

- Book III: Song of Myself

- Book IV: Children of Adam

Wikipedia Entries for Leaves of Grass

- Publication history and origin

- Critical response and controversy

Idaho Falls news, Rexburg news, Pocatello news, East Idaho news, Idaho news, education news, crime news, good news, business news, entertainment news, Feel Good Friday and more.

UPDATE: Teton Pass has reopened; road damage patched by crews

Andrea Olson, EastIdahoNews.com

Teton Pass opened as of 2:10 p.m. Thursday, according to the Wyoming Department of Transportation.

The road (Wyoming State Highway 22) was closed earlier in the day due to road damage. Maintenance crews have temporarily patched the area to allow traffic, but the area continues to be under observation until a more permanent solution can be implemented, WYDOT said.

Drivers are asked to use caution in the area.

ORIGINAL STORY

JACKSON, Wyoming — The Wyoming Department of Transportation has closed Teton Pass due to a large crack in the road, causing unsafe driving conditions.

The road damage announcement came on Thursday just before noon. According to Idaho 511, State Highway 33, eastbound near the Idaho-Wyoming line, is closed.

Transportation crews were told that the road had faulted, and a crack was seen in both lanes of travel, according to a social media post. The crack “dropped vertically,” about 8 inches in some places.

Maintenance crews are working to create a temporary patch. WYDOT’s geology department will investigate the cause.

There is no estimated time of reopening.

Click here for the latest road conditions and updates in Idaho, and here for road conditions in Wyoming.

SUBMIT A CORRECTION

Essay on Road Safety

500 words essay on road safety.

In today’s fast-paced world, road accidents are happening at a very high rate. Although, the technological advancements in the automobile industry has thankfully brought down the mortality rates. Nonetheless, there are a lot of potential hazards that are present on the road. Thus, road safety is important to safeguard everyone. In this essay on road safety, we will learn its importance and its basic rules.

Importance of Essay on Road Safety

Road safety is important to safeguard the well-being of everyone including humans and other living beings. This essay on road safety will help us learn about why it is important. A lot of environmental factors determine our road safety.

For instance, if it is raining or there is heavy fog or smog, the visibility of the driver will be hampered. It may result in pile-ups on the highway. Similarly, there are other factors like rain that lead to hydroplaning.

In this phenomenon, the vehicles that travel at high speeds start to slide uncontrollably as the tires of the vehicle push off the ground through a thin film of water present on the road.

However, road safety rules can help us avoid all these dangerous situations easily. When people follow the road safety rules rigorously and maintain their vehicles well, everyone can remain safe.

Most importantly, it is also essential to drive within the prescribed speed limits. Also, one must not use their mobile phone when driving a vehicle. Road safety is of utmost importance to make sure that everyone remains safe and healthy.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Basic Rules of Road Safety

There are a lot of general and basic rules that one must follow when they drive vehicles or use public roads in general. The first rule is to know the signals and pay attention to them rigorously.

This applies to both the driver as well as the pedestrian. Further, it is important for those who are walking to use the sidewalks and pedestrian crossings. It is also essential to be aware of all the rules and laws of the state and abide by them.

Most importantly, it is also mandatory to have an approved driving license before getting on the road with your vehicle. Road safety sensitization is vital to ensure the safety of everyone.

Making the general public aware of the importance of road safety can help reduce the rate of accidents and road mishaps that happen on a daily basis. Seminars and educating people can be helpful to guide them and make them aware of the consequences.

Conclusion of Essay on Road Safety

To sum it up, everyone must follow the road rules. Do not drive at excessive speed and try to enhance the general awareness so risks of traffic accidents can be reduced. One must also check the vehicle health regularly and its maintenance parts to eliminate any potential risks.

FAQ on Essay on Road Safety

Question 1: What is road safety?

Answer 1: Road safety refers to the methods that we adopt to prevent road users from getting injuries or being killed in traffic accidents. They are essential to maintain everyone’s well being.

Question 2: How can one avoid traffic accidents and enhance road safety?

Answer 2: One can avoid traffic accidents by following the road rules strictly. Moreover, they must also make sure their vehicles are always well-maintained. Further, it is also vital to drive within the speed limits of the state. Do not use phones when driving or be under the influence of alcohol.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Mayor of Waupun says prison should stay open despite issues

WAUPUN, Wis. (WBAY) - Following a sweeping investigation that resulted in criminal charges filed against a prison warden and other prison employees, many have called for Waupun Correctional Institution to be shut down.

But not the Mayor of Waupun.

Department of Correction employees at Wisconsin’s oldest maximum-security prison were arrested earlier this week, including the warden. The Dodge County Sheriff’s Office announced the investigation this week.

During the press conference Wednesday, the sheriff also brought up problems at Green Bay Correctional Institution, renewing a call to shut down both prisons.

However, Waupun Mayor Rohn W. Bishop disagrees, saying in a public column that authorities are “not going to close Waupun Correctional without a fight.”

“For 175 years, Waupun has helped keep Wisconsnites safe by housing those who’ve committed bad crimes,” the mayor wrote. “Waupun is Wisconsin’s oldest prison and Waupun inmates helped to build the Green Bay Prison. Every license plate in Wisconsin is made right here in Waupun and we’re really proud of that.”

“Folks in Green Bay want to close their prison because it’s prime real estate for development, but to make their case, they keep bashing Waupun. And I’ve had it with that! Waupun’s prison means more to us than Green Bay’s means to them. They seem to think they can kick us around and it’s ticked me off! Waupun may be an easy target because we’re a small city, but we’re a great one too! Waupun is Wisconsin’s Sculpture City, we’re America’s Rivet City, we have delicious water, and we still are, and always will be, Wisconsin’s Prison City. As your mayor, they’re not going to close Waupun Correctional without a fight,” the mayor wrote.

Action 2 News also spoke with Mayor Bishop about the column.

“It means so much to our city and our history. What I would say is the prison needs some updates and remodeling but to close it is an overreaction and it’s the wrong thing to do. It’s a simple cop-out for elected officials and bureaucrats in Madison who don’t want to take responsibility for their failures,” he said.

The arrests of nine Department of Corrections employees, including a warden, is opening up a wider discussion on Wisconsin’s aging prisons.

The Dodge County Sheriff’s Office announced this week the investigation at Waupun Correctional Institution over the deaths of two prisoners.

Dodge County Sheriff Dale Schmidt says the failures documented at Waupun are not isolated to one facility. During his press conference on Wednesday, he also brought up problems at Green Bay Correctional Institution and renewed a call to shut down both prisons.

“We are operating the oldest prison in Wisconsin in a dangerous and reckless manner,” the sheriff said Wednesday.

Sheriff Schmidt says Waupun Correctional Institution and Green Bay’s Correctional Institution, two of Wisconsin’s maximum security prisons, share similar issues within their walls.

“They were investigated in Brown County. No criminal charges were filed in those incidents although we have similar issues that occurred during those incidents. A stern warning issued by the investigator to DOC meaning this is not isolated to one facility in the Department of Corrections,” said Sheriff Schmidt.

Sheriff Schmidt is calling on the Department of Corrections, the governor, and state leaders to consider renovating the prisons or closing them altogether.

“One prison could replace two prisons, or two renovated prisons would be better than what we have now, it will save lives and provide more humane treatment of inmates,” said the sheriff.

“The problems at Waupun weren’t caused by Warden Hepp or the good people who work there,” Mayor Bishop wrote in his column. “These problems were caused by governors who didn’t care, legislators who didn’t care, and a media who cared too much about the prisoners instead of the safety of the staff [...] Wisconsin deserves better than what we’re getting. Our inmates deserve better. Our correctional staff deserves better. Waupun deserves better.”

Copyright 2024 WBAY. All rights reserved.

Green Bay Police identify deceased woman; body found along Kepler Drive

UPDATE: Child safely reunited with family

Drug bust at Oshkosh home nets 7 arrests, ages 35 to 74

UPDATE: Wautoma police arrest suspect in attempted child abduction

Oshkosh Arena’s builder files foreclosure notice

Latest news.

Path of serendipity: former NICU baby becomes NICU nurse at local hospital

Path of serendipity: Former NICU baby becomes NICU nurse at local hospital

Events for Saturday’s Bellin Run, road closures begin Friday

UW-Oshkosh gets loan for debt, plans to demolish up to 4 halls

Mt. Olive road back open after tractor trailer overturns

MT. OLIVE, N.C. (WITN) -A road in Mount Olive is back open after being closed due to an overturned tractor trailer.

The Mt. Olive Fire Department says U.S. 117 Southbound was closed from Old Smith Chapel Road to Lees Country Club Road due to an overturned tractor trailer.

It’s not known what caused the accident, but storms were moving through the area at the time and there are reports of several trees down, including one on a house.

Copyright 2024 WITN. All rights reserved.

Major damage at Kinston Jetport from last night’s storm

Police release name of man killed in officer-involved shooting Wednesday

Police say teenager killed at Goldsboro Food Lion

Cause of Greenville house fire that devastated family of five “undetermined”

Validated Crips gang member gets 11 years in federal prison

Latest news.

New Bern mother and daughter sentenced for defrauding COVID-19 Housing Program

New Bern celebrates high school graduation of covid freshmen

Kinston awarded millions to help flooding mitigation

Kinston man arrested for multiple sex charges with a minor

site categories

‘a mistake’ review: elizabeth banks delivers powerful turn in grim medical drama – tribeca film festival, breaking news.

Vertical Acquires Michael Angarano’s Tribeca-Bound Road Trip Comedy ‘Sacramento’

By Matt Grobar

Matt Grobar

Senior Film Reporter

More Stories By Matt

- Mikaela Hoover & Christopher MacDonald Join ‘Superman’

- Jared Leto To Produce, Star In H.wood Media Film Inspired By Professor-Turned-Cat Burglar Suspect Dr. Lawrence Gray

- Hugh Jackman, Emma Thompson, Nicholas Braun, Nicholas Galitzine & More To Star In Amazon MGM Comedy ‘Three Bags Full: A Sheep Detective Movie’

EXCLUSIVE : Ahead of its June 8 world premiere at the Tribeca Festival , the road trip buddy comedy Sacramento , directed by and starring Michael Angarano ( Oppenheimer ), has been acquired by Vertical for distribution in North America, the UK and Ireland later this year.

Related Stories

How Indie Distributor Vertical Went From “VOD Expert” To A Respected Theatrical Player

Vertical Acquires Supernatural Horror Pic ‘The Damned’ Ahead Of Tribeca Premiere

Angarano penned the screenplay with Chris Smith, and they produced the film alongside Bee-Hive Productions’ Stephen Braun, the Wonder Company’s Chris Abernathy and Eric B. Fleischman, and Sam Grey. Irfan Siddiqui served as associate producer.

In a statement on the acquisition, Angarano told Deadline, “ Sacramento was a movie-making experience that was truly one of a kind. Each and every crew member believed in the movie we were making and had fun while doing it, which is all you could ever hope for as a filmmaker. It’s also a very personal film for me which is why I’m grateful to have a home like Vertical.”

Angarano noted that Vertical has established itself as “one of the great independent film distributors” and is “constantly demonstrating their willingness to champion movies like ours. We feel like we have found the perfect partner to continue this movie’s journey.”

Stated Vertical Partner Peter Jarowey, “It’s hard to imagine when Michael found time to sleep, but his incredible talent has produced a hilarious and poignant film that we can’t wait to share with audiences later this year. We’re also thrilled to continue our collaboration with Eric, Stephen, and Chris on this project and look forward to many more successful ventures together.”

Jarowey and SVP of Acquisitions Tony Piantedosi negotiated the deal on behalf of Vertical, with Verve Ventures and UTA’s Independent Film Group repping the production.

Must Read Stories

Kristen stewart to play astronaut sally ride as amazon mgm nears limited series deal.

Bad Boys Back In Town: ‘Ride Or Die’ Driving To $50M In Opening Frame

Jackman, thompson lead starry cast of amazon mgm’s ‘sheep detective movie’, ‘king kong’ loomed large for franka potente: film that lit my fuse.

Subscribe to Deadline Breaking News Alerts and keep your inbox happy.

Read More About:

No comments.

Deadline is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2024 Deadline Hollywood, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

GuEST Essay

Mitch McConnell: We Cannot Repeat the Mistakes of the 1930s

By Mitch McConnell

Mr. McConnell is the Senate minority leader.

On this day in 1944, the liberation of Western Europe began with immense sacrifice. In a tribute delivered 40 years later from a Normandy cliff, President Ronald Reagan reminded us that “the boys of Pointe du Hoc” were “heroes who helped end a war.” That last detail is worth some reflection because we are in danger of forgetting why it matters.

American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines joined allies and took the fight to the Axis powers not as a first instinct, but as a last resort. They ended a war that the free world’s inaction had left them no choice but to fight.

Generations have taken pride in the triumph of the West’s wartime bravery and ingenuity, from the assembly lines to the front lines. We reflect less often on the fact that the world was plunged into war, and millions of innocents died, because European powers and the United States met the rise of a militant authoritarian with appeasement or naïve neglect in the first place.

We forget how influential isolationists persuaded millions of Americans that the fate of allies and partners mattered little to our own security and prosperity. We gloss over the powerful political forces that downplayed growing danger, resisted providing assistance to allies and partners, and tried to limit America’s ability to defend its national interests.

Of course, Americans heard much less from our disgraced isolationists after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Today, America and our allies face some of the gravest threats to our security since Axis forces marched across Europe and the Pacific. And as these threats grow, some of the same forces that hampered our response in the 1930s have re-emerged.

Germany is now a close ally and trading partner. But it was caught flat-footed by the rise of a new axis of authoritarians made up of Russia, China, North Korea and Iran. So, too, were the advanced European powers who once united to defeat the Nazis.

Like the United States, they responded to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine in 2014 with wishful thinking. The disrepair of their militaries and defense industrial bases, and their overreliance on foreign energy and technology, were further exposed by Russia’s dramatic escalation in 2022.

By contrast, Japan needed fewer reminders about threats from aggressive neighbors or about the growing links between Russia and China. Increasingly, America’s allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific are taking seriously the urgent requirements of self-defense. Fortunately, in the past two years, some of our European allies have taken overdue steps in the same direction.

Here at home, we face problems of our own. Some vocal corners of the American right are trying to resurrect the discredited brand of prewar isolationism and deny the basic value of the alliance system that has kept the postwar peace. This dangerous proposition rivals the American left’s longstanding allergy to military spending in its potential to make America less safe.

It should not take another catastrophic attack like Pearl Harbor to wake today’s isolationists from the delusion that regional conflicts have no consequences for the world’s most powerful and prosperous nation. With global power comes global interests and global responsibilities.

Nor should President Biden or congressional Democrats require another major conflict to start investing seriously in American hard power.

The president began this year’s State of the Union with a reference to President Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 effort to prepare the nation to meet the Axis threat. But until the commander in chief is willing to meaningfully invest in America’s deterrent power, this talk carries little weight.

In 1941, President Roosevelt justified a belated increase in military spending to 5.5 percent of gross domestic product. On the road to victory, that figure would reach 37 percent. Deterring conflict today costs less than fighting it tomorrow.

I was encouraged by the plan laid out last week by my friend, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Roger Wicker , which detailed specific actions the president and colleagues in Congress should take to prepare America for long-term strategic competition.

I hope my colleague’s work prompts overdue action to address shortcomings in shipbuilding and the production of long-range munitions and missile defenses. Rebuilding the arsenal of democracy would demonstrate to America’s allies and adversaries alike that our commitment to the stable order of international peace and prosperity is rock-solid.

Nothing else will suffice. Not a desperate pursuit of nuclear diplomacy with Iran, the world’s most active state sponsor of terrorism. Not cabinet junkets to Beijing in pursuit of common ground on climate policy. The way to prove that America means what it says is to show what we’re willing to fight for.

Eighty years ago, America and our allies fought because we had to. The forces assembled on the English Channel on June 6, 1944, represented the fruits of many months of feverish planning. And once victory was secure, the United States led the formation of the alliances that have underpinned Western peace and security ever since.

Today, the better part of valor is to build credible defenses before they are necessary and demonstrate American leadership before it is doubted any further.

Mr. McConnell, a Republican senator from Kentucky, is the Senate minority leader.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an introduction paragraph , how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction: