- Home »

find your perfect postgrad program Search our Database of 30,000 Courses

How to write a masters dissertation or thesis: top tips.

It is completely normal to find the idea of writing a masters thesis or dissertation slightly daunting, even for students who have written one before at undergraduate level. Though, don’t feel put off by the idea. You’ll have plenty of time to complete it, and plenty of support from your supervisor and peers.

One of the main challenges that students face is putting their ideas and findings into words. Writing is a skill in itself, but with the right advice, you’ll find it much easier to get into the flow of writing your masters thesis or dissertation.

We’ve put together a step-by-step guide on how to write a dissertation or thesis for your masters degree, with top tips to consider at each stage in the process.

1. Understand your dissertation or thesis topic

There are slight differences between theses and dissertations , although both require a high standard of writing skill and knowledge in your topic. They are also formatted very similarly.

At first, writing a masters thesis can feel like running a 100m race – the course feels very quick and like there is not as much time for thinking! However, you’ll usually have a summer semester dedicated to completing your dissertation – giving plenty of time and space to write a strong academic piece.

By comparison, writing a PhD thesis can feel like running a marathon, working on the same topic for 3-4 years can be laborious. But in many ways, the approach to both of these tasks is quite similar.

Before writing your masters dissertation, get to know your research topic inside out. Not only will understanding your topic help you conduct better research, it will also help you write better dissertation content.

Also consider the main purpose of your dissertation. You are writing to put forward a theory or unique research angle – so make your purpose clear in your writing.

Top writing tip: when researching your topic, look out for specific terms and writing patterns used by other academics. It is likely that there will be a lot of jargon and important themes across research papers in your chosen dissertation topic.

2. Structure your dissertation or thesis

Writing a thesis is a unique experience and there is no general consensus on what the best way to structure it is.

As a postgraduate student , you’ll probably decide what kind of structure suits your research project best after consultation with your supervisor. You’ll also have a chance to look at previous masters students’ theses in your university library.

To some extent, all postgraduate dissertations are unique. Though they almost always consist of chapters. The number of chapters you cover will vary depending on the research.

A masters dissertation or thesis organised into chapters would typically look like this:

Write down your structure and use these as headings that you’ll write for later on.

Top writing tip : ease each chapter together with a paragraph that links the end of a chapter to the start of a new chapter. For example, you could say something along the lines of “in the next section, these findings are evaluated in more detail”. This makes it easier for the reader to understand each chapter and helps your writing flow better.

3. Write up your literature review

One of the best places to start when writing your masters dissertation is with the literature review. This involves researching and evaluating existing academic literature in order to identify any gaps for your own research.

Many students prefer to write the literature review chapter first, as this is where several of the underpinning theories and concepts exist. This section helps set the stage for the rest of your dissertation, and will help inform the writing of your other dissertation chapters.

What to include in your literature review

The literature review chapter is more than just a summary of existing research, it is an evaluation of how this research has informed your own unique research.

Demonstrate how the different pieces of research fit together. Are there overlapping theories? Are there disagreements between researchers?

Highlight the gap in the research. This is key, as a dissertation is mostly about developing your own unique research. Is there an unexplored avenue of research? Has existing research failed to disprove a particular theory?

Back up your methodology. Demonstrate why your methodology is appropriate by discussing where it has been used successfully in other research.

4. Write up your research

For instance, a more theoretical-based research topic might encompass more writing from a philosophical perspective. Qualitative data might require a lot more evaluation and discussion than quantitative research.

Methodology chapter

The methodology chapter is all about how you carried out your research and which specific techniques you used to gather data. You should write about broader methodological approaches (e.g. qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods), and then go into more detail about your chosen data collection strategy.

Data collection strategies include things like interviews, questionnaires, surveys, content analyses, discourse analyses and many more.

Data analysis and findings chapters

The data analysis or findings chapter should cover what you actually discovered during your research project. It should be detailed, specific and objective (don’t worry, you’ll have time for evaluation later on in your dissertation)

Write up your findings in a way that is easy to understand. For example, if you have a lot of numerical data, this could be easier to digest in tables.

This will make it easier for you to dive into some deeper analysis in later chapters. Remember, the reader will refer back to your data analysis section to cross-reference your later evaluations against your actual findings – so presenting your data in a simple manner is beneficial.

Think about how you can segment your data into categories. For instance, it can be useful to segment interview transcripts by interviewee.

Top writing tip : write up notes on how you might phrase a certain part of the research. This will help bring the best out of your writing. There is nothing worse than when you think of the perfect way to phrase something and then you completely forget it.

5. Discuss and evaluate

Once you’ve presented your findings, it’s time to evaluate and discuss them.

It might feel difficult to differentiate between your findings and discussion sections, because you are essentially talking about the same data. The easiest way to remember the difference is that your findings simply present the data, whereas your discussion tells the story of this data.

Your evaluation breaks the story down, explaining the key findings, what went well and what didn’t go so well.

In your discussion chapter, you’ll have chance to expand on the results from your findings section. For example, explain what certain numbers mean and draw relationships between different pieces of data.

Top writing tip: don’t be afraid to point out the shortcomings of your research. You will receive higher marks for writing objectively. For example, if you didn’t receive as many interview responses as expected, evaluate how this has impacted your research and findings. Don’t let your ego get in the way!

6. Write your introduction

Your introduction sets the scene for the rest of your masters dissertation. You might be wondering why writing an introduction isn't at the start of our step-by-step list, and that’s because many students write this chapter last.

Here’s what your introduction chapter should cover:

Problem statement

Research question

Significance of your research

This tells the reader what you’ll be researching as well as its importance. You’ll have a good idea of what to include here from your original dissertation proposal , though it’s fairly common for research to change once it gets started.

Writing or at least revisiting this section last can be really helpful, since you’ll have a more well-rounded view of what your research actually covers once it has been completed and written up.

Masters dissertation writing tips

When to start writing your thesis or dissertation.

When you should start writing your masters thesis or dissertation depends on the scope of the research project and the duration of your course. In some cases, your research project may be relatively short and you may not be able to write much of your thesis before completing the project.

But regardless of the nature of your research project and of the scope of your course, you should start writing your thesis or at least some of its sections as early as possible, and there are a number of good reasons for this:

Academic writing is about practice, not talent. The first steps of writing your dissertation will help you get into the swing of your project. Write early to help you prepare in good time.

Write things as you do them. This is a good way to keep your dissertation full of fresh ideas and ensure that you don’t forget valuable information.

The first draft is never perfect. Give yourself time to edit and improve your dissertation. It’s likely that you’ll need to make at least one or two more drafts before your final submission.

Writing early on will help you stay motivated when writing all subsequent drafts.

Thinking and writing are very connected. As you write, new ideas and concepts will come to mind. So writing early on is a great way to generate new ideas.

How to improve your writing skills

The best way of improving your dissertation or thesis writing skills is to:

Finish the first draft of your masters thesis as early as possible and send it to your supervisor for revision. Your supervisor will correct your draft and point out any writing errors. This process will be repeated a few times which will help you recognise and correct writing mistakes yourself as time progresses.

If you are not a native English speaker, it may be useful to ask your English friends to read a part of your thesis and warn you about any recurring writing mistakes. Read our section on English language support for more advice.

Most universities have writing centres that offer writing courses and other kinds of support for postgraduate students. Attending these courses may help you improve your writing and meet other postgraduate students with whom you will be able to discuss what constitutes a well-written thesis.

Read academic articles and search for writing resources on the internet. This will help you adopt an academic writing style, which will eventually become effortless with practice.

Keep track of your bibliography

The easiest way to keep the track of all the articles you have read for your research is to create a database where you can summarise each article/chapter into a few most important bullet points to help you remember their content.

Another useful tool for doing this effectively is to learn how to use specific reference management software (RMS) such as EndNote. RMS is relatively simple to use and saves a lot of time when it comes to organising your bibliography. This may come in very handy, especially if your reference section is suspiciously missing two hours before you need to submit your dissertation!

Avoid accidental plagiarism

Plagiarism may cost you your postgraduate degree and it is important that you consciously avoid it when writing your thesis or dissertation.

Occasionally, postgraduate students commit plagiarism unintentionally. This can happen when sections are copy and pasted from journal articles they are citing instead of simply rephrasing them. Whenever you are presenting information from another academic source, make sure you reference the source and avoid writing the statement exactly as it is written in the original paper.

What kind of format should your thesis have?

Read your university’s guidelines before you actually start writing your thesis so you don’t have to waste time changing the format further down the line. However in general, most universities will require you to use 1.5-2 line spacing, font size 12 for text, and to print your thesis on A4 paper. These formatting guidelines may not necessarily result in the most aesthetically appealing thesis, however beauty is not always practical, and a nice looking thesis can be a more tiring reading experience for your postgrad examiner .

When should I submit my thesis?

The length of time it takes to complete your MSc or MA thesis will vary from student to student. This is because people work at different speeds, projects vary in difficulty, and some projects encounter more problems than others.

Obviously, you should submit your MSc thesis or MA thesis when it is finished! Every university will say in its regulations that it is the student who must decide when it is ready to submit.

However, your supervisor will advise you whether your work is ready and you should take their advice on this. If your supervisor says that your work is not ready, then it is probably unwise to submit it. Usually your supervisor will read your final thesis or dissertation draft and will let you know what’s required before submitting your final draft.

Set yourself a target for completion. This will help you stay on track and avoid falling behind. You may also only have funding for the year, so it is important to ensure you submit your dissertation before the deadline – and also ensure you don’t miss out on your graduation ceremony !

To set your target date, work backwards from the final completion and submission date, and aim to have your final draft completed at least three months before that final date.

Don’t leave your submission until the last minute – submit your work in good time before the final deadline. Consider what else you’ll have going on around that time. Are you moving back home? Do you have a holiday? Do you have other plans?

If you need to have finished by the end of June to be able to go to a graduation ceremony in July, then you should leave a suitable amount of time for this. You can build this into your dissertation project planning at the start of your research.

It is important to remember that handing in your thesis or dissertation is not the end of your masters program . There will be a period of time of one to three months between the time you submit and your final day. Some courses may even require a viva to discuss your research project, though this is more common at PhD level .

If you have passed, you will need to make arrangements for the thesis to be properly bound and resubmitted, which will take a week or two. You may also have minor corrections to make to the work, which could take up to a month or so. This means that you need to allow a period of at least three months between submitting your thesis and the time when your program will be completely finished. Of course, it is also possible you may be asked after the viva to do more work on your thesis and resubmit it before the examiners will agree to award the degree – so there may be an even longer time period before you have finished.

How do I submit the MA or MSc dissertation?

Most universities will have a clear procedure for submitting a masters dissertation. Some universities require your ‘intention to submit’. This notifies them that you are ready to submit and allows the university to appoint an external examiner.

This normally has to be completed at least three months before the date on which you think you will be ready to submit.

When your MA or MSc dissertation is ready, you will have to print several copies and have them bound. The number of copies varies between universities, but the university usually requires three – one for each of the examiners and one for your supervisor.

However, you will need one more copy – for yourself! These copies must be softbound, not hardbound. The theses you see on the library shelves will be bound in an impressive hardback cover, but you can only get your work bound like this once you have passed.

You should submit your dissertation or thesis for examination in soft paper or card covers, and your university will give you detailed guidance on how it should be bound. They will also recommend places where you can get the work done.

The next stage is to hand in your work, in the way and to the place that is indicated in your university’s regulations. All you can do then is sit and wait for the examination – but submitting your thesis is often a time of great relief and celebration!

Some universities only require a digital submission, where you upload your dissertation as a file through their online submission system.

Related articles

What Is The Difference Between A Dissertation & A Thesis

How To Get The Most Out Of Your Writing At Postgraduate Level

Dos & Don'ts Of Academic Writing

Dispelling Dissertation Drama

Writing A Dissertation Proposal

Postgrad Solutions Study Bursaries

Exclusive bursaries Open day alerts Funding advice Application tips Latest PG news

Sign up now!

Take 2 minutes to sign up to PGS student services and reap the benefits…

- The chance to apply for one of our 5 PGS Bursaries worth £2,000 each

- Fantastic scholarship updates

- Latest PG news sent directly to you.

Department of Economics

4: dissertation and project guidelines, dissertation and project guidelines, dissertation guidelines for msc economics and msc economics and international financial economics.

The main aim of the dissertation is to encourage independent study and to provide a foundation for future original research. In terms of learning, the dissertation should provide you with a number of research skills, including the ability to:

- Define a feasible project allowing for time and resource constraints;

- Develop an adequate methodology;

- Make optimal use of library resources;

- Access data bases, understand their uses and limitations and extract relevant data;

- Work without the need for continuous supervision.

Topic selection and allocation of supervisors

Your first task is to determine your dissertation topic and possible supervisor. Topics will be suggested by module lecturers, especially on the optional modules, and by members of faculty. In the Spring Term you will have Research Methods lectures that explicitly direct you to sources of inspiration. Alternatively, you may already know the topic you wish to pursue. A word of advice: it is critical that you choose a topic that you are really interested in and not something that you think sounds good.

Information on potential supervisors will be made available in a spreadsheet, which gives you a list of all supervisors available for 2023-2024, along with their main areas of interest and their suggested dissertation topics. Alternatively, you can browse the staff personal web pages for information, or approach members of staff directly with your research ideas.

Students need to approach their potential supervisor and confirm supervision with them in writing (an email is sufficient). Note that supervisors will only be able to accept a limited number of students each. If you have a preferred supervisor in mind approach them early with a clear idea of a topic you would like to pursue to avoid disappointment.

Once you have decided on a topic you should go to the online form on the dissertation webpage. On this form, you are asked to indicate:

(i) your thesis title, and

(ii) a short (max 200 words) description of your planned research.

(iii) your dissertation supervisor (if you have reached an agreement with a supervisor).

The deadline for submitting this form is 12.00 noon on Monday 8 April 2024 (week 28).

If you have not made an agreement with a supervisor then you will be asked to sign up for one of the remaining supervisors on Tabula, and the slots will be filled on a first-come first-served basis. You will be notified of the date and time for doing this by email.

By the start of week 34 of the Summer Term, i.e. Monday 20 May 2024 (week 34) , all students will be allocated supervisors.

Changes in title must be agreed with the supervisor. A request for a change in supervisor must be made directly to the Director of Graduate Studies (Taught Degrees). Changes will only be made if both original and new supervisor agree.

Timetable for Summer Term

Students are expected to stay in the UK during the Summer Term and will be delivering their presentations in-person.

Monday 8 April 2024 (week 28) - 12.00 noon

Deadline for submission of proposed title of dissertation and prospective supervisors online form Link opens in a new window .

Monday 20 May 2024 (week 34)

MSc dissertation supervisors announced.

Wednesday 29 May 2024 (week 35)

Deadline for submitting ethical scrutiny form (if applicable).

Monday 3 June - Fri 14 June 2024 (weeks 36/37)

During this period supervisors will arrange for all supervisees to give short in-person presentations of their ideas.

Monday 24 June 2024 (week 39)

Deadline for submitting Dissertation Proposal by e-submission.

Wednesday 11 September 2024 (week 50)

Dissertation submission deadline for MSc in Economics and MSc in Economics and International Financial Economics.

Wednesday 5 March 2025 (week 23)

Dissertation submission deadline (for resit candidates).

The role of the supervisor

The role of the supervisor is:

- To advise you on the feasibility of your chosen topic and ways of refining it;

- To provide some references to the general methodology to be used;

- To provide general guidance to the literature review and analysis of the chosen topic.

Supervision will take place mainly or entirely during the summer term. This means that both you and your supervisor need to use the time efficiently. The role of the supervisor during the summer term is to help you develop your dissertation proposal and then to mark and provide feedback on your proposal. During the summer vacation the expectation is that you will be working independently, and your supervisor’s role will be to read and make some comments on a final draft of your work.

Additional support to develop research skills

In the Spring Term we run Research Methods lectures and workshops to equip you with the necessary skills required for research and help to prepare you for your dissertation. The weekly sessions will explain the dissertation process, how to select your topic, what makes a good dissertation, how to complete literature reviews and identify your data. We will continue to build on your skills in econometrics packages with a session on STATA. A Library dissertation training session will explain available resources and how to access databases. A detailed schedule for the lectures and workshops will be announced in the Spring Term.

We provide weekly surgeries in the summer term and vacation to help answer queries about your topic and deal with software and econometric problems. Full details of this facility will be circulated in week 34 of the Summer Term.

It is very important that you identify appropriate data source(s) for your dissertation if you are doing an empirical topic, and you should discuss the availability of sources with your supervisor an early stage.

Some organisations will only supply data on the condition that it would be stored on the Department's secure servers and that the Department would take legal responsibility for it. Unfortunately, the Department is unable to meet these conditions, and in this situation, you would need to use an alternative data source.

Please also be aware that the Department does not typically pay for data sets or cover other costs relating to MSc dissertation data collection (for example, surveys). Therefore, please identify data that are already available or can be acquired free of change. Our Economics Academic Support Librarian, Jackie Hanes, is happy to help you find the information you need for your research, show you how to use specific resources, or discuss any other issues you might have. Her email address is [email protected].

Ethical scrutiny

At Warwick, any research, including dissertations for Masters degrees, that involves direct contact with participants, through their physical participation in research activities (invasive and non-invasive participation, including surveys or personal data collection conducted by any means), that indirectly involves participants through their provision of data or tissue, or that involves people on behalf of others (e.g. parents on behalf of children), requires ethical scrutiny.

Note that your research does not require ethical scrutiny if it does not involve direct or indirect contact with participants. For example, most research involving previously existing datasets where individual-level information is not provided, or where individuals are not identified, or using historical records, does not require ethical scrutiny, and this is likely to include most research conducted in the Department. Research involving laboratory or field experiments, or the collection of new individual level survey data, always requires ethical scrutiny.

It is your responsibility to seek the necessary scrutiny and approval, and if in doubt, you must consult your supervisor.

If your research work requires ethical scrutiny and approval, checks are conducted within the Department in line with rules approved by the University’s Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee. Please consult with your supervisor and complete the Department’s form for ethical approval of student research Link opens in a new window .

The form should be submitted to the Postgraduate Office by Wednesday 29 May 2024 (week 35).

The dissertation proposal

There are two parts to the dissertation proposal: a presentation and a written proposal.

First, you will be required to present your proposed topic to your supervisor and fellow students in a group. This will help you focus your ideas, especially via feedback from other students and your supervisor. Please note that some supervisors will organise individual meetings for presentations. The presentations should take the following format:

- The presentation will be delivered in-person.

- You will have 10-15 minutes each, comprising your 5-10 minute presentation followed by five minutes of discussion and comment;

- The presentation should either use Powerpoint or PDF;

- You must identify the title of your proposed research, the research objective, the data and any computing/statistical tools required (for example, Stata);

- The research objective should be briefly expanded into a justification of why you want to study this question — why it is important followed by a short description of what you intend to do;

- One slide is adequate for covering related literature.

Then, based on your presentation and any feedback you receive, you have to write a detailed dissertation proposal to include a literature review and research plan. This should be a maximum length of 1,000 words excluding all appendices, footnotes, tables and the bibliography.

Please note that your supervisor will not comment on a draft of your proposal before you submit it.

The dissertation proposal will be assessed and carries a mark worth 10% of the mark for the dissertation module as a whole. The deadline is Monday 24 June 2024 (week 39) and you should submit your proposal electronically via Tabula.

Dissertation format

The dissertation is worth 90% of the total mark for the dissertation module. There is no minimum word length and concise expositions are encouraged. The dissertation should be a maximum length of 8,000 words, excluding acknowledgements, appendices, footnotes, words in graphs, tables, notes to tables and the bibliography. Note there is a limit of 15 pages for the appendices, footnotes, and tables. Abstract words, quotations and citations count towards the word limit.

We recommend that you use Microsoft Word or Scientific Word, both of which can easily insert equations. The first page of the dissertation itself should include the title, your name, date and any preface and acknowledgements. Pages and sections must be numbered. We have no particular preference for how you format your dissertation. The structure of your dissertation will be decided upon by yourself and your supervisor. We have published some top past dissertations and proposals Link opens in a new window to show you what headings/sub headings other students have used, and how the dissertation might be organised. Every dissertation will normally include:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Methodology

- Results/Discussion

References should be collected at the back in alphabetical order and should contain sufficient detail to allow them to be followed up if required: at a minimum you should cite author, date of publication, title of book or article, journal of publication or book publishing company.

Submitting your dissertation

Your MSc dissertation must be submitted electronically via Tabula under module code EC959. The name of the PDF file should be your student ID number. As well as the PDF of your dissertation, you should submit your “log” (output) file, noting that you will need to upload the .PDF file and the .txt output file at the same time – if you upload them separately the second file may overwrite the other. Please note that we reserve the right to ask to see further details of your data and any econometric and other programmes you have used to analyse it. So, we advise you to keep electronic copies of data and programs (including do-files if applicable) until after the Exam Board has met.

At the same time, you must also submit a completed Dissertation Submission Form Link opens in a new window . No paper copies of your dissertation are required.

Deadlines and extensions

There will be two deadlines each year for MSc dissertations. The September deadline applies to all MSc students who have passed their examinations at the first attempt and are not taking any re(sit) exams in September. The March deadline will be for those students who are doing re(sit) exams in September, and for those who may have asked for an extension due to mitigating circumstances.

Students who are doing one re(sit) exam and are able to hand in their dissertation for the September deadline will be permitted to do so, on the understanding that this is done at their own risk; the dissertation will not be considered if they have not met the criteria for the taught component of the MSc (see the section on MSc Exam Schemes Link opens in a new window ). In the case of two re(sit) exams, we strongly advise you to defer your dissertation until March of the following year. However, if you really feel you have to do your dissertation over the summer, for example, because you are going straight to a job, or for other reasons, you must discuss the situation with your supervisor, and obtain his/her agreement. Please note that we cannot give you a short deadline extension in September because you have got resit examinations. If you have failed or missed three or more exams, we require you to defer the writing of your dissertation until after the September exams, without any exceptions.

If you cannot make your September or March deadline due to medical, or other mitigating circumstances, you must fill in an extension request form, available on Tabula. If your application is approved, you will be permitted to submit your dissertation by the agreed extension date or the next biannual deadline (either March or September). You need to supply suitable medical or other evidence within one week of submitting the extension request. The evidence you provide should cover a substantial part of the dissertation period detailing why you were unable to work on the dissertation. Please note that extensions will not be granted for short-term illnesses or being in full- or part-time employment.

Assessment and feedback

To achieve at least a pass, a dissertation must demonstrate a high level of competence in both analysis and expression. This can be achieved in several ways, for instance by:

- Providing a critical survey of some area of the subject. This should be written in such a way as to take the non-specialist reader from the beginnings of the topic up to the frontiers. It should integrate and synthesise existing ideas, demonstrate the relationships between them and assess their significance. It is not enough to simply catalogue previous work. However lengthy the bibliography is, a dissertation which shows no deep grasp of the motivation, content and structure of the literature will fail. Though ‘originality’ in the sense of a demonstrable theoretical or empirical innovation is not required in order to pass, it is expected that some degree of original thought will be needed to place the ideas of others in a coherent setting;

- Applying techniques developed by others to a data-set not previously used for that purpose, with a clear motivation for doing so;

- Examining the robustness of an existing theoretical model to changes in its underlying assumptions, with a clear motivation for doing so.

At least two examiners will assess your dissertation. Markers will use the 20-point scale shown in the next section when marking the proposal and dissertation (though note that the final mark agreed by first and second dissertation markers is not restricted to the 20-point scale to enable averaging if appropriate).

No feedback on the result of your dissertation is possible until after the Exam Board meets in November 2024, when your mark and comments will be provided through Tabula. Second markers are not required to write comments, though they can do so if they wish. If the second marker does write comments these can be included separately, or they can be combined into a joint report.

20-point marking scale

Research project guidelines for msc behavioural and economic science.

You will carry out novel research in the area of behavioural science. You will work within one of the departments’ labs, designing and running independent empirical work that addresses a current research question. You will have the support of experts in the field and will produce research suitable for publication in an international journal.

Projects are:

- Empirical (that is an experiment, computer program, survey or observational study);

- Physically safe and ethically acceptable (conform to the British Psychological Society Code of Conduct);

- Practical in terms of demands on time, equipment, number of subjects required and laboratory space.

Potential research project topics will be provided in the Spring Term. When the topics are published, please do contact supervisors. You will indicate your project preferences via an online form, with projects allocated centrally.

You must read the British Psychological Society Code of Human Research Ethics. If you are conducting research using the internet, you must also read the British Psychological Society guidelines on internet mediated research. Both documents can be found on the BPS website Link opens in a new window .

At Warwick, any research that involves direct contact with participants, through their physical participation in research activities (invasive and non-invasive participation), that indirectly involves participants through their provision of data or tissue and that involves people on behalf of others (e.g. parents on behalf of children) requires ethical scrutiny. It is your and your supervisor’s joint responsibility to ensure that ethical approval is secured, and this should take place very early in the Summer Term.

If you consider that ethical approval is necessary, please consult with your supervisor and submit the relevant form for ethical approval to [email protected] Link opens in a new window . When there are multiple students on the same project, we will only require one form.

Format and submission

Projects might typically contain one or two experiments or a significant econometric analysis of a large data set. The research in the report should be of a publishable standard. This normally means that the research is relevant and innovative, that there are no major methodological flaws and that the conclusions are appropriate.

With your supervisor choose an appropriate target journal. The formatting of the dissertation must be as for submission to your target journal. Write up your report following the journal submission guidelines. Include on the front page of your report the name of the journal you select. Avoid writing in a more generic 'thesis style' as you may have done for past projects.

Project reports, excluding appendices, should not exceed 20,000 words, and should normally be much shorter. Your target journal may well have a word or page limit which you should follow.

Appendices of test material, raw data, protocols, etc. need not be submitted with your project, but copies of these materials must be given to your supervisor (see below).

No paper copies are required. Please submit online through Tabula as a PDF.

You must retain all of the data that you collect. You must submit all of your data directly to your supervisor when you submit your project. Ideally, you should also submit R scripts (or another language) for the complete analysis of your data.

There will be two deadlines each year for MSc projects. The first will be in August and the second one will be in March. The August deadline will be for all MSc students who have passed their examinations at the first attempt and those with the option to proceed to the project. The March deadline will be for those students who are required to do one or more re(sit) exams in September, either for core modules, or for optional modules where a mark of less than 40 was achieved at the first attempt. The March deadline is also for those who may have asked for an extension due to mitigating circumstances.

Students who are required to re(sit) one exam and are able to hand in their project for the August deadline will be permitted to do so, on the understanding that this is done at their own risk; the project will not be considered if they have not met the criteria for the taught component of the MSc (see the section on Exam Schemes Link opens in a new window ). In the case of students being required to take two re(sit) exams, our advice is that you defer your project until March of the following year. Please note that we cannot give you a short deadline extension in August/September because you have got resit exams. If you have failed or missed three or more exams, we require you to defer the writing of your project until after the September exams, without any exceptions.

If you cannot make your August or March deadline due to medical, or other mitigating circumstances, you must fill in an extension request form, available on Tabula. If an application is approved, the student will be permitted to submit their dissertation by the agreed extension date or the next biannual deadline (either March or August). You need to supply suitable medical or other evidence within one week of submitting the extension request. The evidence you provide should cover a substantial part of the project period detailing why you were unable to work on the dissertation. Please note that extensions will not be granted for low-level and short-term illnesses, or being in full- or part-time employment.

References should be in the style of your target journal. Minimally they should contain the author, date of publication, title of book or article, journal of publication and volume or book publishing company. Almost all journals are very specific about referencing. If there is no guidance (very unlikely) follow the APA conventions.

Assessment is based upon the project report. In assessing reports, some of the points markers will have in mind are:

- How well has the student been able to formulate the research question or hypothesis and establish why it is an important question to ask? How precise is the hypothesis?

- How well does the student know relevant theoretical and empirical literature and can they frame the research question in the light of such literature?

- How clearly has the student described the design and procedure of the investigation and specified the subject sample(s) investigated? (Could the reader replicate the investigation on the basis of the information given?)

- How clearly and how thoroughly has the student been able to describe and analyse the data obtained? How well does the student understand the logic of descriptive and inferential statistics? Can the student explore findings intelligently and not simply number-crunch?

- How well does the student interpret the findings in relation to the original rationale for the investigation? How aware is the student of limitations in the design of the investigation (also important for meta-analysis and analysis of existing data sets) or in the way the research question was formulated? How well can the student point to what might next be done in the light of what has been learned from the investigation?

- What is the overall quality of writing, presentation, organisation and attention to detail?

At least two examiners will assess your project, employing the criteria described elsewhere in this handbook. No feedback on the result of your project is possible until after the Exam Board meets in November 2024, when your mark and comments will be provided through Tabula. Second markers are not required to write comments, though they can do so if they wish. If the second marker does write comments these can be included separately, or they can be combined into a joint report.

How To Write A Research Proposal

A Straightforward How-To Guide (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2019 (Updated April 2023)

Writing up a strong research proposal for a dissertation or thesis is much like a marriage proposal. It’s a task that calls on you to win somebody over and persuade them that what you’re planning is a great idea. An idea they’re happy to say ‘yes’ to. This means that your dissertation proposal needs to be persuasive , attractive and well-planned. In this post, I’ll show you how to write a winning dissertation proposal, from scratch.

Before you start:

– Understand exactly what a research proposal is – Ask yourself these 4 questions

The 5 essential ingredients:

- The title/topic

- The introduction chapter

- The scope/delimitations

- Preliminary literature review

- Design/ methodology

- Practical considerations and risks

What Is A Research Proposal?

The research proposal is literally that: a written document that communicates what you propose to research, in a concise format. It’s where you put all that stuff that’s spinning around in your head down on to paper, in a logical, convincing fashion.

Convincing is the keyword here, as your research proposal needs to convince the assessor that your research is clearly articulated (i.e., a clear research question) , worth doing (i.e., is unique and valuable enough to justify the effort), and doable within the restrictions you’ll face (time limits, budget, skill limits, etc.). If your proposal does not address these three criteria, your research won’t be approved, no matter how “exciting” the research idea might be.

PS – if you’re completely new to proposal writing, we’ve got a detailed walkthrough video covering two successful research proposals here .

How do I know I’m ready?

Before starting the writing process, you need to ask yourself 4 important questions . If you can’t answer them succinctly and confidently, you’re not ready – you need to go back and think more deeply about your dissertation topic .

You should be able to answer the following 4 questions before starting your dissertation or thesis research proposal:

- WHAT is my main research question? (the topic)

- WHO cares and why is this important? (the justification)

- WHAT data would I need to answer this question, and how will I analyse it? (the research design)

- HOW will I manage the completion of this research, within the given timelines? (project and risk management)

If you can’t answer these questions clearly and concisely, you’re not yet ready to write your research proposal – revisit our post on choosing a topic .

If you can, that’s great – it’s time to start writing up your dissertation proposal. Next, I’ll discuss what needs to go into your research proposal, and how to structure it all into an intuitive, convincing document with a linear narrative.

The 5 Essential Ingredients

Research proposals can vary in style between institutions and disciplines, but here I’ll share with you a handy 5-section structure you can use. These 5 sections directly address the core questions we spoke about earlier, ensuring that you present a convincing proposal. If your institution already provides a proposal template, there will likely be substantial overlap with this, so you’ll still get value from reading on.

For each section discussed below, make sure you use headers and sub-headers (ideally, numbered headers) to help the reader navigate through your document, and to support them when they need to revisit a previous section. Don’t just present an endless wall of text, paragraph after paragraph after paragraph…

Top Tip: Use MS Word Styles to format headings. This will allow you to be clear about whether a sub-heading is level 2, 3, or 4. Additionally, you can view your document in ‘outline view’ which will show you only your headings. This makes it much easier to check your structure, shift things around and make decisions about where a section needs to sit. You can also generate a 100% accurate table of contents using Word’s automatic functionality.

Ingredient #1 – Topic/Title Header

Your research proposal’s title should be your main research question in its simplest form, possibly with a sub-heading providing basic details on the specifics of the study. For example:

“Compliance with equality legislation in the charity sector: a study of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ made in three London care homes”

As you can see, this title provides a clear indication of what the research is about, in broad terms. It paints a high-level picture for the first-time reader, which gives them a taste of what to expect. Always aim for a clear, concise title . Don’t feel the need to capture every detail of your research in your title – your proposal will fill in the gaps.

Need a helping hand?

Ingredient #2 – Introduction

In this section of your research proposal, you’ll expand on what you’ve communicated in the title, by providing a few paragraphs which offer more detail about your research topic. Importantly, the focus here is the topic – what will you research and why is that worth researching? This is not the place to discuss methodology, practicalities, etc. – you’ll do that later.

You should cover the following:

- An overview of the broad area you’ll be researching – introduce the reader to key concepts and language

- An explanation of the specific (narrower) area you’ll be focusing, and why you’ll be focusing there

- Your research aims and objectives

- Your research question (s) and sub-questions (if applicable)

Importantly, you should aim to use short sentences and plain language – don’t babble on with extensive jargon, acronyms and complex language. Assume that the reader is an intelligent layman – not a subject area specialist (even if they are). Remember that the best writing is writing that can be easily understood and digested. Keep it simple.

Note that some universities may want some extra bits and pieces in your introduction section. For example, personal development objectives, a structural outline, etc. Check your brief to see if there are any other details they expect in your proposal, and make sure you find a place for these.

Ingredient #3 – Scope

Next, you’ll need to specify what the scope of your research will be – this is also known as the delimitations . In other words, you need to make it clear what you will be covering and, more importantly, what you won’t be covering in your research. Simply put, this is about ring fencing your research topic so that you have a laser-sharp focus.

All too often, students feel the need to go broad and try to address as many issues as possible, in the interest of producing comprehensive research. Whilst this is admirable, it’s a mistake. By tightly refining your scope, you’ll enable yourself to go deep with your research, which is what you need to earn good marks. If your scope is too broad, you’re likely going to land up with superficial research (which won’t earn marks), so don’t be afraid to narrow things down.

Ingredient #4 – Literature Review

In this section of your research proposal, you need to provide a (relatively) brief discussion of the existing literature. Naturally, this will not be as comprehensive as the literature review in your actual dissertation, but it will lay the foundation for that. In fact, if you put in the effort at this stage, you’ll make your life a lot easier when it’s time to write your actual literature review chapter.

There are a few things you need to achieve in this section:

- Demonstrate that you’ve done your reading and are familiar with the current state of the research in your topic area.

- Show that there’s a clear gap for your specific research – i.e., show that your topic is sufficiently unique and will add value to the existing research.

- Show how the existing research has shaped your thinking regarding research design . For example, you might use scales or questionnaires from previous studies.

When you write up your literature review, keep these three objectives front of mind, especially number two (revealing the gap in the literature), so that your literature review has a clear purpose and direction . Everything you write should be contributing towards one (or more) of these objectives in some way. If it doesn’t, you need to ask yourself whether it’s truly needed.

Top Tip: Don’t fall into the trap of just describing the main pieces of literature, for example, “A says this, B says that, C also says that…” and so on. Merely describing the literature provides no value. Instead, you need to synthesise it, and use it to address the three objectives above.

Ingredient #5 – Research Methodology

Now that you’ve clearly explained both your intended research topic (in the introduction) and the existing research it will draw on (in the literature review section), it’s time to get practical and explain exactly how you’ll be carrying out your own research. In other words, your research methodology.

In this section, you’ll need to answer two critical questions :

- How will you design your research? I.e., what research methodology will you adopt, what will your sample be, how will you collect data, etc.

- Why have you chosen this design? I.e., why does this approach suit your specific research aims, objectives and questions?

In other words, this is not just about explaining WHAT you’ll be doing, it’s also about explaining WHY. In fact, the justification is the most important part , because that justification is how you demonstrate a good understanding of research design (which is what assessors want to see).

Some essential design choices you need to cover in your research proposal include:

- Your intended research philosophy (e.g., positivism, interpretivism or pragmatism )

- What methodological approach you’ll be taking (e.g., qualitative , quantitative or mixed )

- The details of your sample (e.g., sample size, who they are, who they represent, etc.)

- What data you plan to collect (i.e. data about what, in what form?)

- How you plan to collect it (e.g., surveys , interviews , focus groups, etc.)

- How you plan to analyse it (e.g., regression analysis, thematic analysis , etc.)

- Ethical adherence (i.e., does this research satisfy all ethical requirements of your institution, or does it need further approval?)

This list is not exhaustive – these are just some core attributes of research design. Check with your institution what level of detail they expect. The “ research onion ” by Saunders et al (2009) provides a good summary of the various design choices you ultimately need to make – you can read more about that here .

Don’t forget the practicalities…

In addition to the technical aspects, you will need to address the practical side of the project. In other words, you need to explain what resources you’ll need (e.g., time, money, access to equipment or software, etc.) and how you intend to secure these resources. You need to show that your project is feasible, so any “make or break” type resources need to already be secured. The success or failure of your project cannot depend on some resource which you’re not yet sure you have access to.

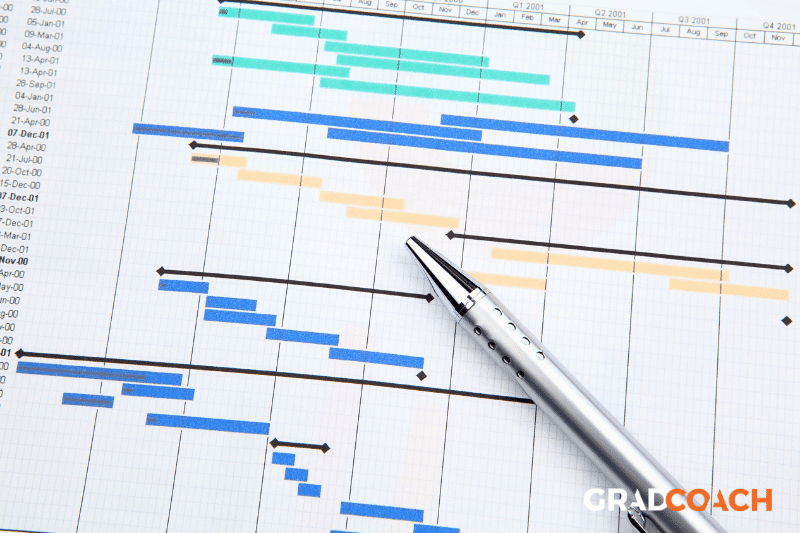

Another part of the practicalities discussion is project and risk management . In other words, you need to show that you have a clear project plan to tackle your research with. Some key questions to address:

- What are the timelines for each phase of your project?

- Are the time allocations reasonable?

- What happens if something takes longer than anticipated (risk management)?

- What happens if you don’t get the response rate you expect?

A good way to demonstrate that you’ve thought this through is to include a Gantt chart and a risk register (in the appendix if word count is a problem). With these two tools, you can show that you’ve got a clear, feasible plan, and you’ve thought about and accounted for the potential risks.

Tip – Be honest about the potential difficulties – but show that you are anticipating solutions and workarounds. This is much more impressive to an assessor than an unrealistically optimistic proposal which does not anticipate any challenges whatsoever.

Final Touches: Read And Simplify

The final step is to edit and proofread your proposal – very carefully. It sounds obvious, but all too often poor editing and proofreading ruin a good proposal. Nothing is more off-putting for an assessor than a poorly edited, typo-strewn document. It sends the message that you either do not pay attention to detail, or just don’t care. Neither of these are good messages. Put the effort into editing and proofreading your proposal (or pay someone to do it for you) – it will pay dividends.

When you’re editing, watch out for ‘academese’. Many students can speak simply, passionately and clearly about their dissertation topic – but become incomprehensible the moment they turn the laptop on. You are not required to write in any kind of special, formal, complex language when you write academic work. Sure, there may be technical terms, jargon specific to your discipline, shorthand terms and so on. But, apart from those, keep your written language very close to natural spoken language – just as you would speak in the classroom. Imagine that you are explaining your project plans to your classmates or a family member. Remember, write for the intelligent layman, not the subject matter experts. Plain-language, concise writing is what wins hearts and minds – and marks!

Let’s Recap: Research Proposal 101

And there you have it – how to write your dissertation or thesis research proposal, from the title page to the final proof. Here’s a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- The purpose of the research proposal is to convince – therefore, you need to make a clear, concise argument of why your research is both worth doing and doable.

- Make sure you can ask the critical what, who, and how questions of your research before you put pen to paper.

- Title – provides the first taste of your research, in broad terms

- Introduction – explains what you’ll be researching in more detail

- Scope – explains the boundaries of your research

- Literature review – explains how your research fits into the existing research and why it’s unique and valuable

- Research methodology – explains and justifies how you will carry out your own research

Hopefully, this post has helped you better understand how to write up a winning research proposal. If you enjoyed it, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . If your university doesn’t provide any template for your proposal, you might want to try out our free research proposal template .

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

Thank you so much for the valuable insight that you have given, especially on the research proposal. That is what I have managed to cover. I still need to go back to the other parts as I got disturbed while still listening to Derek’s audio on you-tube. I am inspired. I will definitely continue with Grad-coach guidance on You-tube.

Thanks for the kind words :). All the best with your proposal.

First of all, thanks a lot for making such a wonderful presentation. The video was really useful and gave me a very clear insight of how a research proposal has to be written. I shall try implementing these ideas in my RP.

Once again, I thank you for this content.

I found reading your outline on writing research proposal very beneficial. I wish there was a way of submitting my draft proposal to you guys for critiquing before I submit to the institution.

Hi Bonginkosi

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, we do provide a review service. The best starting point is to have a chat with one of our coaches here: https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Hello team GRADCOACH, may God bless you so much. I was totally green in research. Am so happy for your free superb tutorials and resources. Once again thank you so much Derek and his team.

You’re welcome, Erick. Good luck with your research proposal 🙂

thank you for the information. its precise and on point.

Really a remarkable piece of writing and great source of guidance for the researchers. GOD BLESS YOU for your guidance. Regards

Thanks so much for your guidance. It is easy and comprehensive the way you explain the steps for a winning research proposal.

Thank you guys so much for the rich post. I enjoyed and learn from every word in it. My problem now is how to get into your platform wherein I can always seek help on things related to my research work ? Secondly, I wish to find out if there is a way I can send my tentative proposal to you guys for examination before I take to my supervisor Once again thanks very much for the insights

Thanks for your kind words, Desire.

If you are based in a country where Grad Coach’s paid services are available, you can book a consultation by clicking the “Book” button in the top right.

Best of luck with your studies.

May God bless you team for the wonderful work you are doing,

If I have a topic, Can I submit it to you so that you can draft a proposal for me?? As I am expecting to go for masters degree in the near future.

Thanks for your comment. We definitely cannot draft a proposal for you, as that would constitute academic misconduct. The proposal needs to be your own work. We can coach you through the process, but it needs to be your own work and your own writing.

Best of luck with your research!

I found a lot of many essential concepts from your material. it is real a road map to write a research proposal. so thanks a lot. If there is any update material on your hand on MBA please forward to me.

GradCoach is a professional website that presents support and helps for MBA student like me through the useful online information on the page and with my 1-on-1 online coaching with the amazing and professional PhD Kerryen.

Thank you Kerryen so much for the support and help 🙂

I really recommend dealing with such a reliable services provider like Gradcoah and a coach like Kerryen.

Hi, Am happy for your service and effort to help students and researchers, Please, i have been given an assignment on research for strategic development, the task one is to formulate a research proposal to support the strategic development of a business area, my issue here is how to go about it, especially the topic or title and introduction. Please, i would like to know if you could help me and how much is the charge.

This content is practical, valuable, and just great!

Thank you very much!

Hi Derek, Thank you for the valuable presentation. It is very helpful especially for beginners like me. I am just starting my PhD.

This is quite instructive and research proposal made simple. Can I have a research proposal template?

Great! Thanks for rescuing me, because I had no former knowledge in this topic. But with this piece of information, I am now secured. Thank you once more.

I enjoyed listening to your video on how to write a proposal. I think I will be able to write a winning proposal with your advice. I wish you were to be my supervisor.

Dear Derek Jansen,

Thank you for your great content. I couldn’t learn these topics in MBA, but now I learned from GradCoach. Really appreciate your efforts….

From Afghanistan!

I have got very essential inputs for startup of my dissertation proposal. Well organized properly communicated with video presentation. Thank you for the presentation.

Wow, this is absolutely amazing guys. Thank you so much for the fruitful presentation, you’ve made my research much easier.

this helps me a lot. thank you all so much for impacting in us. may god richly bless you all

How I wish I’d learn about Grad Coach earlier. I’ve been stumbling around writing and rewriting! Now I have concise clear directions on how to put this thing together. Thank you!

Fantastic!! Thank You for this very concise yet comprehensive guidance.

Even if I am poor in English I would like to thank you very much.

Thank you very much, this is very insightful.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide

Published on 14 February 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on 11 November 2022.

A dissertation proposal describes the research you want to do: what it’s about, how you’ll conduct it, and why it’s worthwhile. You will probably have to write a proposal before starting your dissertation as an undergraduate or postgraduate student.

A dissertation proposal should generally include:

- An introduction to your topic and aims

- A literature review of the current state of knowledge

- An outline of your proposed methodology

- A discussion of the possible implications of the research

- A bibliography of relevant sources

Dissertation proposals vary a lot in terms of length and structure, so make sure to follow any guidelines given to you by your institution, and check with your supervisor when you’re unsure.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Step 1: coming up with an idea, step 2: presenting your idea in the introduction, step 3: exploring related research in the literature review, step 4: describing your methodology, step 5: outlining the potential implications of your research, step 6: creating a reference list or bibliography.

Before writing your proposal, it’s important to come up with a strong idea for your dissertation.

Find an area of your field that interests you and do some preliminary reading in that area. What are the key concerns of other researchers? What do they suggest as areas for further research, and what strikes you personally as an interesting gap in the field?

Once you have an idea, consider how to narrow it down and the best way to frame it. Don’t be too ambitious or too vague – a dissertation topic needs to be specific enough to be feasible. Move from a broad field of interest to a specific niche:

- Russian literature 19th century Russian literature The novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky

- Social media Mental health effects of social media Influence of social media on young adults suffering from anxiety

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Like most academic texts, a dissertation proposal begins with an introduction . This is where you introduce the topic of your research, provide some background, and most importantly, present your aim , objectives and research question(s) .

Try to dive straight into your chosen topic: What’s at stake in your research? Why is it interesting? Don’t spend too long on generalisations or grand statements:

- Social media is the most important technological trend of the 21st century. It has changed the world and influences our lives every day.

- Psychologists generally agree that the ubiquity of social media in the lives of young adults today has a profound impact on their mental health. However, the exact nature of this impact needs further investigation.

Once your area of research is clear, you can present more background and context. What does the reader need to know to understand your proposed questions? What’s the current state of research on this topic, and what will your dissertation contribute to the field?

If you’re including a literature review, you don’t need to go into too much detail at this point, but give the reader a general sense of the debates that you’re intervening in.

This leads you into the most important part of the introduction: your aim, objectives and research question(s) . These should be clearly identifiable and stand out from the text – for example, you could present them using bullet points or bold font.

Make sure that your research questions are specific and workable – something you can reasonably answer within the scope of your dissertation. Avoid being too broad or having too many different questions. Remember that your goal in a dissertation proposal is to convince the reader that your research is valuable and feasible:

- Does social media harm mental health?

- What is the impact of daily social media use on 18– to 25–year–olds suffering from general anxiety disorder?

Now that your topic is clear, it’s time to explore existing research covering similar ideas. This is important because it shows you what is missing from other research in the field and ensures that you’re not asking a question someone else has already answered.

You’ve probably already done some preliminary reading, but now that your topic is more clearly defined, you need to thoroughly analyse and evaluate the most relevant sources in your literature review .

Here you should summarise the findings of other researchers and comment on gaps and problems in their studies. There may be a lot of research to cover, so make effective use of paraphrasing to write concisely:

- Smith and Prakash state that ‘our results indicate a 25% decrease in the incidence of mechanical failure after the new formula was applied’.

- Smith and Prakash’s formula reduced mechanical failures by 25%.

The point is to identify findings and theories that will influence your own research, but also to highlight gaps and limitations in previous research which your dissertation can address:

- Subsequent research has failed to replicate this result, however, suggesting a flaw in Smith and Prakash’s methods. It is likely that the failure resulted from…

Next, you’ll describe your proposed methodology : the specific things you hope to do, the structure of your research and the methods that you will use to gather and analyse data.

You should get quite specific in this section – you need to convince your supervisor that you’ve thought through your approach to the research and can realistically carry it out. This section will look quite different, and vary in length, depending on your field of study.

You may be engaged in more empirical research, focusing on data collection and discovering new information, or more theoretical research, attempting to develop a new conceptual model or add nuance to an existing one.

Dissertation research often involves both, but the content of your methodology section will vary according to how important each approach is to your dissertation.

Empirical research

Empirical research involves collecting new data and analysing it in order to answer your research questions. It can be quantitative (focused on numbers), qualitative (focused on words and meanings), or a combination of both.

With empirical research, it’s important to describe in detail how you plan to collect your data:

- Will you use surveys ? A lab experiment ? Interviews?

- What variables will you measure?

- How will you select a representative sample ?

- If other people will participate in your research, what measures will you take to ensure they are treated ethically?

- What tools (conceptual and physical) will you use, and why?

It’s appropriate to cite other research here. When you need to justify your choice of a particular research method or tool, for example, you can cite a text describing the advantages and appropriate usage of that method.

Don’t overdo this, though; you don’t need to reiterate the whole theoretical literature, just what’s relevant to the choices you have made.

Moreover, your research will necessarily involve analysing the data after you have collected it. Though you don’t know yet what the data will look like, it’s important to know what you’re looking for and indicate what methods (e.g. statistical tests , thematic analysis ) you will use.

Theoretical research

You can also do theoretical research that doesn’t involve original data collection. In this case, your methodology section will focus more on the theory you plan to work with in your dissertation: relevant conceptual models and the approach you intend to take.

For example, a literary analysis dissertation rarely involves collecting new data, but it’s still necessary to explain the theoretical approach that will be taken to the text(s) under discussion, as well as which parts of the text(s) you will focus on:

- This dissertation will utilise Foucault’s theory of panopticism to explore the theme of surveillance in Orwell’s 1984 and Kafka’s The Trial…

Here, you may refer to the same theorists you have already discussed in the literature review. In this case, the emphasis is placed on how you plan to use their contributions in your own research.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

You’ll usually conclude your dissertation proposal with a section discussing what you expect your research to achieve.

You obviously can’t be too sure: you don’t know yet what your results and conclusions will be. Instead, you should describe the projected implications and contribution to knowledge of your dissertation.

First, consider the potential implications of your research. Will you:

- Develop or test a theory?

- Provide new information to governments or businesses?

- Challenge a commonly held belief?

- Suggest an improvement to a specific process?

Describe the intended result of your research and the theoretical or practical impact it will have:

Finally, it’s sensible to conclude by briefly restating the contribution to knowledge you hope to make: the specific question(s) you hope to answer and the gap the answer(s) will fill in existing knowledge:

Like any academic text, it’s important that your dissertation proposal effectively references all the sources you have used. You need to include a properly formatted reference list or bibliography at the end of your proposal.

Different institutions recommend different styles of referencing – commonly used styles include Harvard , Vancouver , APA , or MHRA . If your department does not have specific requirements, choose a style and apply it consistently.

A reference list includes only the sources that you cited in your proposal. A bibliography is slightly different: it can include every source you consulted in preparing the proposal, even if you didn’t mention it in the text. In the case of a dissertation proposal, a bibliography may also list relevant sources that you haven’t yet read, but that you intend to use during the research itself.

Check with your supervisor what type of bibliography or reference list you should include.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, November 11). How to Write a Dissertation Proposal | A Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Master Thesis/Project Report Format

Guidelines for preparation of master thesis/project report, overview of the steps.

- Select master project/thesis advisor.

- Select a project topic.

- Select a committee.

- Obtain approvals for committee, advisor.

- Register for the master project/thesis course with thesis advisor. (A section number will be provided to you by your project/thesis advisor.)

- Start Research on your master project.

- (Optional) Present a thesis proposal to the committee during mid-way of the thesis.

- Write project report/thesis.

- Present your master project and/or defend thesis.

- Submit your master project report, or publish thesis.

Project/Thesis Option

Discuss with your master project advisor at the beginning to decide whether your master project will be more suited for the project or thesis option.

Questions to ask when evaluating your master project topic:

- Is there current interest in this topic in the field?

- Is there is a gap in knowledge that work on this topic could help to fill?

- Is it possible to focus on a manageable segment of this topic?

- Identify a preliminary method of data collection that is acceptable to your advisor.

- Is there a body of literature is available that is relevant to your topic?

- Do you need financial assistance to carry out your research?

- Is the data necessary to complete your work is easily accessible?

- Define the project purpose, scope, objectives, and procedures.

- What are the potential limitations of the study?

- Are there any skills called on by the study that you have yet to acquire?

Master level project involves:

- Analyzing the problem or topic.

- Conducting extensive research.

- Summarizing findings from the research investigation.

- Recommending additional research on the topic.

- Drawing conclusions and making recommendations.

- Documenting the results of the research.

- Defending conclusions and recommendations.

Pre-Thesis Planning

When you’re contemplating a thesis topic, you should discuss your interests with as many people as possible to gain a broad perspective. You will find your faculty advisor knowledgeable and willing to offer excellent suggestions and advice regarding an appropriate thesis topic.

Give considerable thought to the identification and planning of a thesis topic. Review literature related to your interests; read a variety of research papers, abstracts, and proposals for content, methods and structure. Looking at completed master’s theses will be a useful activity toward expanding inquiry skills and thought processes.

After the thesis advisor is selected, you may register on-line for a thesis section. You will need to see your thesis instructor to obtain the thesis section number.

Suggested Master Project/Thesis Completion Timeline

Below please find a suggested timeline. Individual timelines may vary from one student to another.

Required Deadlines

- The approval page with all signatures must be submitted to the graduate advisor prior to the last day of the semester.

- The thesis must be submitted electronically prior to the last day of classes. The last day of class can be identified in the on-line Academic calendar.

Scholarship Possibilities

Funding is usually available to students with expertise to the specific area. You will want to research scholarship options during the pre-project planning as many scholarship applications are due months before the award is granted.

- Research assistantship with a faculty advisor related to the topic of research

- Teaching assistantship to teach an undergraduate laboratory

- Check with Career Center for on-campus positions

- Attend all career fairs that would be of interest to consider summer internships

- SPIE (The International Society for Optics and Photonics)

- ISA (International Society of Automation)