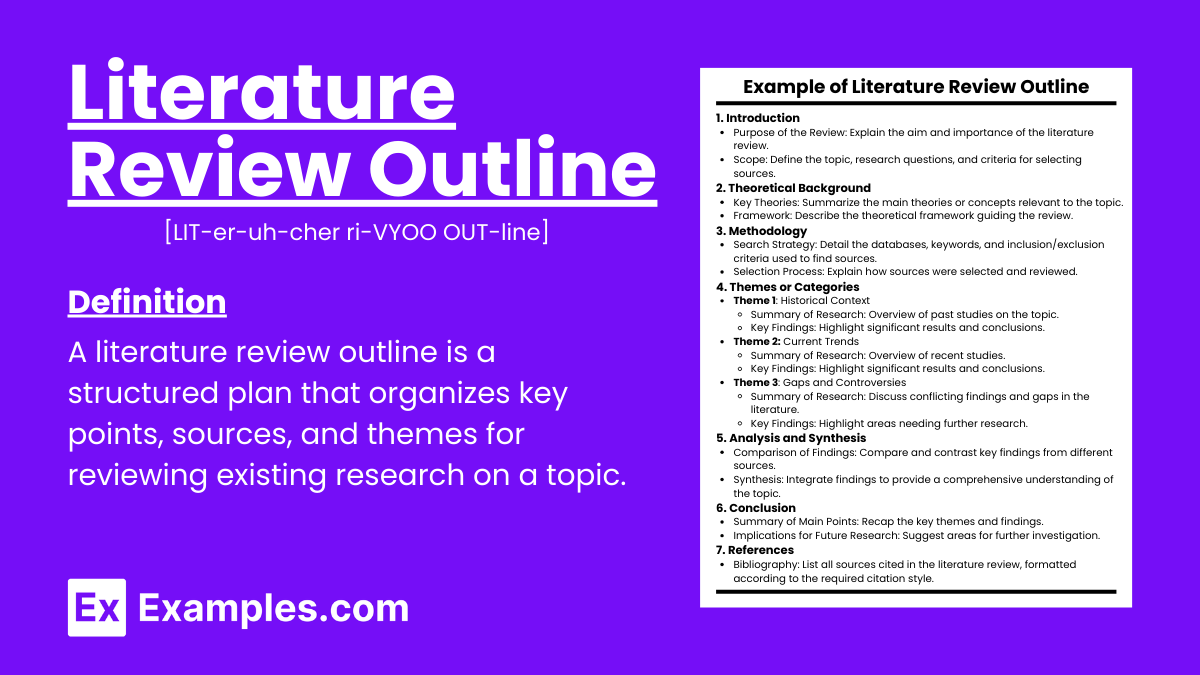

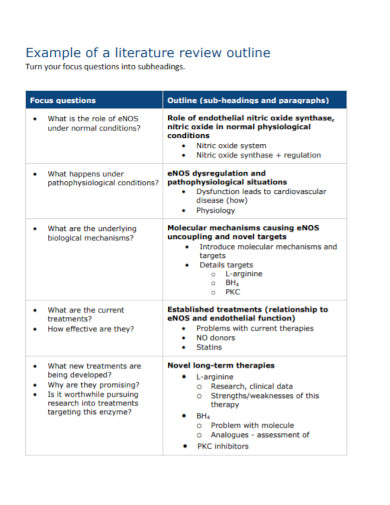

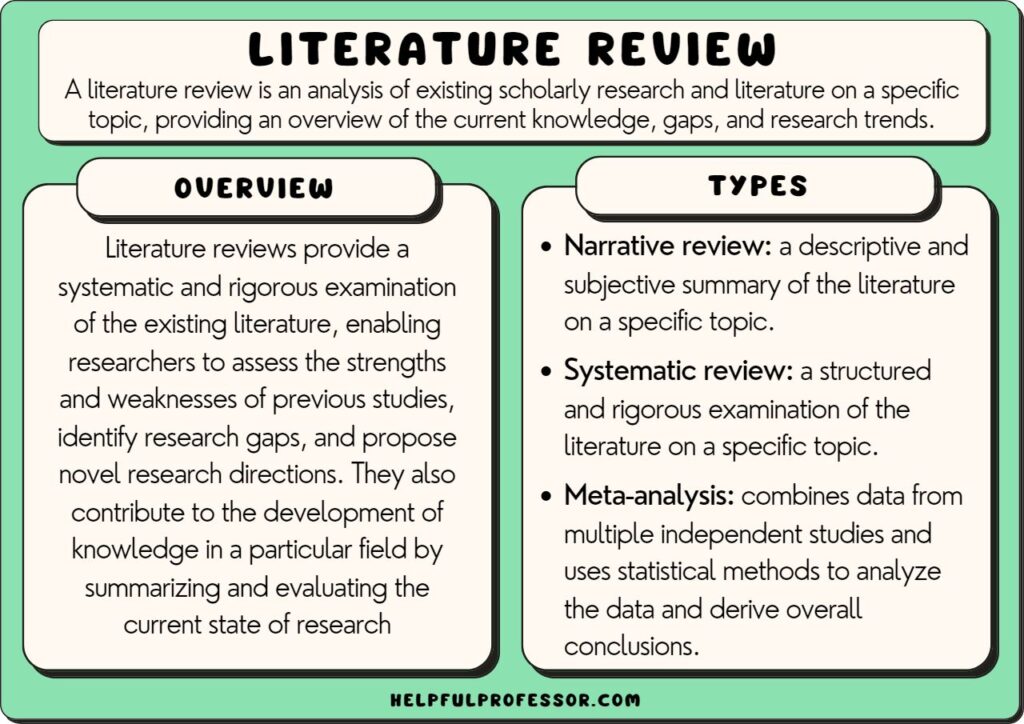

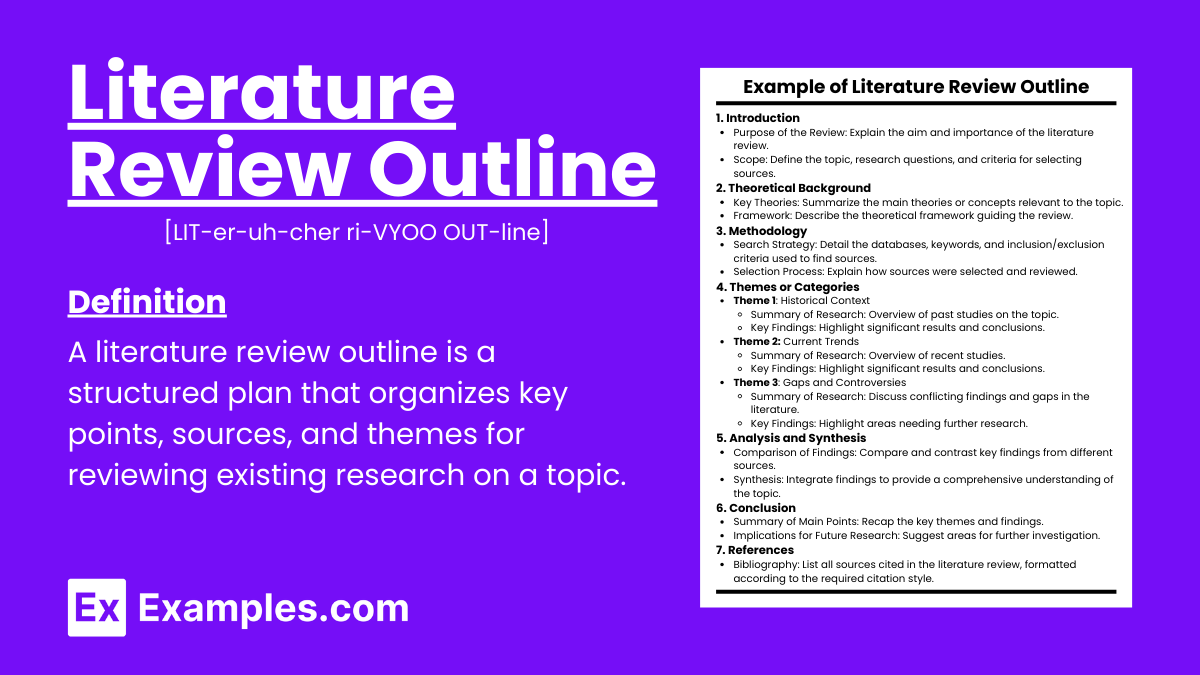

Literature Review OutlineAi generator.  Literature Review. We all been there, especially those who are currently in high school or college. We get to review different types of literary pieces ranging from short stories , poem , and novels just to name a few. It can be confusing when you have a lot of ideas but you have no idea how to formulate them into one clean thought. It can also be quite frustrating if you have to start from the beginning or back to square one if you forgot a single part of the whole, but don’t worry, here are some literature review outline examples you can download to help you with your problems. Let’s check them out. What is a Literature Review Outline?A literature review outline is a structured framework that organizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic. It helps identify key themes, gaps, and methodologies in the literature. The outline typically includes sections such as introduction, major themes, sub-themes, methodologies, and conclusions, facilitating a clear and comprehensive review of the literature. Literature Review FormatA literature review is a comprehensive summary of previous research on a topic. It includes a systematic examination of scholarly article , book , and other sources relevant to the research area. Here’s a guide to structuring a literature review effectively: Introduction- Explain the purpose of the literature review.

- Define the scope of the review – what is included and what is excluded.

- State the research question or objective .

- Provide context or background information necessary to understand the literature review.

- Highlight the significance of the topic.

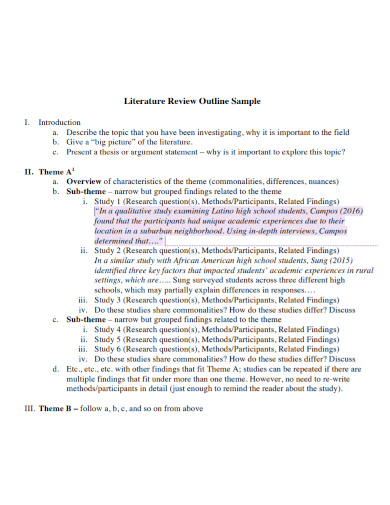

- Organize the literature review by themes, trends, or methodological approaches rather than by individual sources.

- Use headings and subheadings to categorize different themes or topics.

- For each theme or section, summarize the key findings of the relevant literature.

- Highlight major theories, methodologies, and conclusions.

- Note any significant debates or controversies.

- Critically evaluate the sources.

- Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the existing research.

- Identify gaps or inconsistencies in the literature.

- Compare and contrast different sources.

- Synthesize the information to provide a coherent narrative.

- Show how the different studies are related to one another.

- Summarize the main findings from the literature review.

- Highlight the most important insights and their implications.

- Identify any gaps in the existing research that require further investigation.

- Suggest areas for future research.

- Discuss the overall significance of the literature review.

- Explain how it contributes to the field of study and the specific research question.

- List all the sources cited in the literature review.

- Follow the appropriate citation style (APA, MLA , Chicago, etc.) as required by your academic institution.

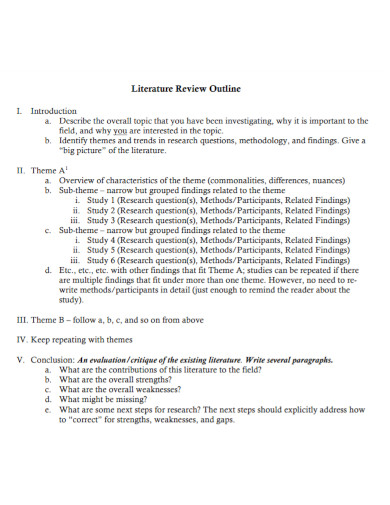

Research Literature Review Outline ExampleI. Introduction Background Information: Provide context and background on the research topic. Explain the importance of the topic in the current research landscape. Purpose of the Review: State the main objectives of the literature review. Clarify the research questions or hypotheses guiding the review. Scope of the Review: Define the scope, including time frame, types of studies, and key themes. Explain any limitations or boundaries set for the review. II. Search Strategy Databases and Sources: List the databases and other sources used to find relevant literature. Keywords and Search Terms: Detail the specific keywords and search terms employed. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Describe the criteria for including or excluding studies. III. Theoretical Framework Relevant Theories: Introduce and explain the key theories and models related to the research topic. Application of Theories: Discuss how these theories provide a foundation for understanding the literature. IV. Review of Literature Thematic Organization: Organize the literature into themes or categories based on common findings or approaches. Example Structure: Theme 1: Impact of Rising Temperatures Summarize key studies and findings. Compare and contrast different research approaches. Theme 2: Changing Precipitation Patterns Highlight significant studies and their results. Discuss any conflicting findings or perspectives. Theme 3: Socioeconomic Factors Review literature focusing on socioeconomic impacts. Analyze how these factors interact with environmental changes. V. Critical Analysis Strengths and Weaknesses: Evaluate the strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies. Discuss the reliability and validity of the methodologies used. Methodological Critique: Assess the methodologies for potential biases and gaps. VI. Discussion and Synthesis Integration of Findings: Synthesize the findings from the literature into a cohesive narrative. Highlight common themes, trends, and gaps. Research Gaps: Identify areas where further research is needed. Suggest potential future research directions. VII. Conclusion Summary of Main Findings: Summarize the key insights and conclusions drawn from the literature review. Importance of the Topic: Reiterate the significance of the research topic. Implications for Future Research: Outline the implications of the findings for future research. VIII. References Citation List: Provide a complete list of all sources cited in the literature review. Follow a specific citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). IX. Appendices (if applicable) Supplementary Material: Include tables, charts, or detailed methodological information that supports the review but is too extensive for the main text. Thematic Literature Review Outline ExampleI. Introduction Background Information: Provide context and background on the research topic. Explain the importance of the topic in the current research landscape. Purpose of the Review: State the main objectives of the literature review. Clarify the research questions or hypotheses guiding the review. Scope of the Review: Define the scope, including time frame, types of studies, and key themes. Explain any limitations or boundaries set for the review. II. Search Strategy Databases and Sources: List the databases and other sources used to find relevant literature. Keywords and Search Terms: Detail the specific keywords and search terms employed. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Describe the criteria for including or excluding studies. III. Thematic Review of Literature Theme 1: Impact of Rising Temperatures Summary of Key Studies: Summarize the findings of major studies related to rising temperatures. Example: “Smith et al. (2020) found that increasing temperatures have led to a 5% decline in crop yields globally.” Comparison of Research Approaches: Compare different methodologies and approaches used in the studies. Example: “While Jones (2018) used a longitudinal study, Brown (2019) employed a cross-sectional analysis.” Theme 2: Changing Precipitation Patterns Summary of Key Studies: Highlight significant studies and their results. Example: “Lee and Wang (2021) reported that altered precipitation patterns have increased the frequency of droughts.” Discussion of Conflicting Findings: Discuss any contradictory findings or differing perspectives. Example: “Contrary to Lee and Wang, Garcia (2020) found minimal impact of precipitation changes on crop health.” Theme 3: Socioeconomic Factors Summary of Key Studies: Review literature focusing on the socioeconomic impacts of climate change. Example: “Davis (2017) highlighted the disproportionate effects on small-scale farmers.” Analysis of Interactions: Analyze how socioeconomic factors interact with environmental changes. Example: “Economic instability exacerbates the vulnerability to climate impacts (Green, 2018).” IV. Critical Analysis Strengths and Weaknesses: Evaluate the strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies. Example: “Many studies provide robust data but often lack consideration of regional variability.” Methodological Critique: Assess the methodologies for potential biases and gaps. Example: “There is a notable reliance on regional data, limiting the generalizability of findings.” V. Discussion and Synthesis Integration of Findings: Synthesize the findings from the literature into a cohesive narrative. Example: “The review indicates a clear trend of climate change negatively impacting agriculture, though the extent varies regionally.” Identification of Gaps: Identify areas where further research is needed. Example: “There is a gap in research on adaptive farming practices and their effectiveness.” VI. Conclusion Summary of Main Findings: Summarize the key insights and conclusions drawn from the literature review. Example: “Overall, rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are significantly affecting agricultural productivity.” Importance of the Topic: Reiterate the significance of the research topic. Example: “Understanding these impacts is crucial for developing effective adaptation strategies.” Implications for Future Research: Outline the implications of the findings for future research. Example: “Future research should focus on adaptive measures to mitigate the adverse effects on agriculture.” VII. References Citation List: Provide a complete list of all sources cited in the literature review. Example: Smith, J. et al. (2020). Impact of Rising Temperatures on Global Crop Yields . Journal of Environmental Studies, 45(3), 234-250. Lee, S. & Wang, H. (2021). Precipitation Patterns and Drought Frequency . Climate Research Journal, 29(2), 98-115. VIII. Appendices (if applicable) Supplementary Material: Include tables, charts, or detailed methodological information that supports the review but is too extensive for the main text. Example: “Appendix A includes a table of regional crop yield changes from 2000 to 2020.” Literature Review Outline Example in APA Format1. Title Page Title of the Review Author’s Name Institutional Affiliation Course Name and Number Instructor’s Name Due Date 2. Abstract Summary of the Literature Review Brief overview of the main points Research question or thesis Key findings Implications 3. Introduction Introduction to the Topic General introduction to the subject area Importance of the topic Purpose of the Review Specific objectives of the literature review Research Questions or Hypotheses Main research question(s) or hypotheses guiding the review Organization of the Review Brief outline of the structure of the literature review 4. Theoretical Framework Relevant Theories and Models Description of key theories and models relevant to the topic Application of Theories Explanation of how these theories are applied to the research problem 5. Review of the Literature Historical Context Background and historical development of the research topic Current Research Summary of recent studies and their findings Methodologies Used Overview of research methods used in the studies Themes and Patterns Common themes and patterns identified in the literature Contradictions and Gaps Conflicting findings and gaps in the literature 6. Critical Analysis Evaluation of Key Studies Critical analysis of the most influential studies Strengths and limitations of these studies Comparison of Different Approaches Comparative analysis of different perspectives and methodologies 7. Synthesis of Findings Integration of Theories and Results How the findings integrate with the theoretical framework Overall Trends Summary of the major trends in the literature Gaps in the Research Identification of gaps and areas for further research 8. Conclusion Summary of Main Findings Recap of the most significant findings from the review Implications for Future Research Suggestions for future research directions Practical Applications Implications for practice or policy 9. References Complete Citation of Sources Proper APA format for all sources cited in the literature review 10. Appendices (if necessary) Additional Material Any supplementary material such as tables, figures, or questionnaires Literature Review Outline Templates & Samples in PDF1. literature review template.  3. Literature Review Outline Template 6. Preliminary Outline of Literature Review 7. Literature Review Outline Example 8. Printable Literature Review Outline Types of Literature ReviewA literature review is an essential part of academic research, providing a comprehensive summary of previous studies on a particular topic. There are various types of literature reviews, each serving a different purpose and following a unique structure. Here, we explore the main types: 1. Narrative ReviewA narrative review, also known as a traditional or descriptive review, provides a comprehensive synthesis of the existing literature on a specific topic. It focuses on summarizing and interpreting the findings rather than conducting a systematic analysis. 2. Systematic ReviewA systematic review follows a rigorous and predefined methodology to collect, analyze, and synthesize all relevant studies on a particular research question. It aims to minimize bias and provide reliable findings. 3. Meta-AnalysisA meta-analysis is a subset of systematic reviews that statistically combines the results of multiple studies to arrive at a single conclusion. It provides a higher level of evidence by increasing the sample size and improving the precision of the results. 4. Scoping ReviewA scoping review aims to map the existing literature on a broad topic, identify key concepts, theories, and sources, and clarify research gaps. It is often used to determine the scope of future research. 5. Critical ReviewA critical review evaluates the quality and validity of the existing literature, often questioning the methodology and findings. It provides a critical assessment and aims to present a deeper understanding of the topic. 6. Theoretical ReviewA theoretical review focuses on analyzing and synthesizing theories related to a specific topic. It aims to understand how theories have evolved over time and how they can be applied to current research. 7. Integrative ReviewAn integrative review synthesizes research on a topic in a more holistic manner, combining perspectives from both qualitative and quantitative studies. It aims to generate new frameworks and perspectives. 8. Annotated BibliographyAn annotated bibliography provides a summary and evaluation of each source in a list of references. It includes a brief description of the content, relevance, and quality of each source. 9. Rapid ReviewA rapid review streamlines the systematic review process to provide evidence in a timely manner. It is often used in healthcare and policy-making to inform decisions quickly. 10. Umbrella ReviewAn umbrella review, or overview of reviews, synthesizes the findings of multiple systematic reviews on a particular topic. It provides a high-level summary and identifies broader patterns and trends. Purpose of a Literature ReviewA literature review is a critical component of academic research, serving multiple important purposes. It provides a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on a topic, helps identify research gaps, and sets the context for new research. Here are the key purposes of a literature review: 1. Summarizing Existing ResearchA literature review summarizes and synthesizes the findings of previous studies related to a specific topic. This helps researchers understand what is already known and what remains to be explored. 2. Identifying Research GapsBy reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps or inconsistencies in the current knowledge. This allows them to pinpoint areas where further investigation is needed and justify the need for their research. 3. Providing Context and BackgroundA literature review sets the context for new research by providing background information. It helps readers understand the broader landscape of the topic and how the current study fits into it. 4. Establishing the Theoretical FrameworkLiterature reviews often involve discussing various theories and models relevant to the topic. This helps establish a theoretical framework for the research, guiding the study’s design and methodology. 5. Demonstrating Researcher KnowledgeConducting a thorough literature review demonstrates that the researcher is knowledgeable about the field. It shows that they are aware of the key studies, debates, and trends in their area of research. 6. Justifying Research Questions and MethodologyA literature review helps justify the research questions and methodology of a study. By showing how previous studies were conducted and what their limitations were, researchers can argue for their chosen approach. 7. Avoiding DuplicationReviewing existing literature ensures that researchers do not duplicate previous studies unnecessarily. It helps them build on existing work rather than repeating it. 8. Highlighting Key Findings and TrendsA literature review highlights significant findings and trends in the research area. This helps researchers understand the development of the field and identify influential studies and seminal works. 9. Informing Practice and PolicyIn applied fields, literature reviews can inform practice and policy by summarizing evidence on what works and what doesn’t. This helps practitioners and policymakers make evidence-based decisions. 10. Facilitating a Comprehensive UnderstandingOverall, a literature review facilitates a comprehensive understanding of the topic. It integrates various perspectives, findings, and approaches, providing a well-rounded view of the research area. Components of a Literature ReviewA well-structured literature review is essential for providing a clear and comprehensive overview of existing research on a particular topic. The following components are typically included in a literature review: 1. IntroductionThe introduction sets the stage for the literature review. It provides background information on the topic, explains the review’s purpose, and outlines its scope. Example: “Over the past decade, research on climate change’s impact on agriculture has proliferated. This literature review aims to synthesize these studies, focusing on the effects of rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns on crop yields.” 2. Search StrategyThe search strategy describes how the literature was identified. This includes the databases and search engines used, search terms and keywords, and any inclusion or exclusion criteria. Example: “The literature search was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR. Keywords included ‘climate change,’ ‘agriculture,’ ‘crop yields,’ and ‘precipitation patterns.’ Studies published between 2000 and 2023 were included.” 3. Theoretical FrameworkThe theoretical framework presents the theories and models relevant to the research topic. This section provides a foundation for understanding the studies reviewed. Example: “This review utilizes the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework to analyze the impact of climate change on agricultural communities, focusing on how environmental changes affect economic stability and food security.” 4. Review of LiteratureThe core of the literature review, this section summarizes and synthesizes the findings of the selected studies. It is often organized thematically, chronologically, or methodologically. Example: “Studies from the early 2000s focused on temperature changes, while recent research has shifted to examining precipitation patterns. Common findings include a general decline in crop yields, with significant regional variations.” 5. Critical AnalysisA critical analysis evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the existing research. This involves assessing the methodology, data, and conclusions of the studies reviewed. Example: “Many studies used longitudinal data to track changes over time, but few incorporated socioeconomic factors. Additionally, the reliance on regional data limits the generalizability of some findings.” 6. Discussion and SynthesisThe discussion and synthesis section integrates the findings from the literature review, highlighting common themes, trends, and gaps. It connects the reviewed studies to the current research question. Example: “The literature consistently shows that rising temperatures negatively affect crop yields. However, there is a gap in understanding the role of adaptive farming practices, suggesting a need for further research in this area.” 7. ConclusionThe conclusion summarizes the main findings of the literature review. It reiterates the importance of the research topic and outlines the implications for future research. Example: “In summary, climate change poses a significant threat to agricultural productivity. Future research should focus on adaptive strategies to mitigate these effects and ensure food security.” 8. ReferencesThe references section lists all the sources cited in the literature review. It should follow a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago. - Smith, J. (2021). Climate Change and Crop Yields . Journal of Environmental Science, 12(3), 45-60.

- Brown, A., & Jones, B. (2019). Precipitation Patterns and Agriculture . Climate Research, 8(2), 34-48.

9. Appendices (if applicable)Appendices may include supplementary material that is relevant to the literature review but would disrupt the flow of the main text. This could include tables, charts, or detailed methodological information. Example: “Appendix A includes a table of regional crop yield changes from 2000 to 2020. Appendix B provides a detailed description of the data collection methods used in the reviewed studies.” How to Write a Literature Review Writing a literature review involves several steps to ensure that you provide a comprehensive, critical, and coherent summary of existing research on a specific topic. Here is a step-by-step guide to help you write an effective literature review: 1. Define Your Topic and Scope- Identify your research question or thesis.

- Decide on the scope (broad topic or specific aspect, time frame, types of studies).

2. Conduct a Comprehensive Literature Search- Identify key sources (use academic databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, JSTOR).

- Use relevant keywords to search for literature.

- Select relevant studies by reviewing abstracts.

3. Organize the Literature- Group studies by themes (methodology, findings, theoretical perspective).

- Create an outline to structure your review.

4. Summarize and Synthesize the Literature- Summarize key findings for each study.

- Synthesize information by comparing and contrasting studies.

5. Write the Literature Review- Introduce the topic.

- Explain the purpose of the review.

- Outline the scope.

- Discuss literature thematically or chronologically.

- Present summaries and syntheses.

- Highlight patterns, contradictions, and gaps.

- Evaluate methodologies and findings.

- Discuss strengths and weaknesses of studies.

- Summarize main findings.

- Reiterate the importance of the topic.

6. Cite Your Sources- Use a consistent citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago).

7. Review and Revise- Proofread for grammatical errors and clarity.

- Revise for coherence and logical flow.

How do I start a literature review?Begin by defining your research question and scope, then conduct a comprehensive search for relevant literature using academic databases. What is the purpose of a theoretical framework?It provides a foundation for understanding the literature and guides the analysis of existing studies. How should I organize the literature review?Organize it thematically, chronologically, or methodologically, depending on what best suits your research question. How do I choose which studies to include?Use inclusion and exclusion criteria based on relevance, publication date, and quality of the studies. What is the difference between a thematic and chronological organization?Thematic organization groups studies by topics or themes, while chronological organization arranges them by the date of publication. How do I critically analyze the literature?Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study, assess methodologies, and discuss biases or gaps. What should be included in the introduction?Provide background information, state the purpose of the review, and outline its scope. How can I synthesize findings from different studies?Integrate the results to highlight common themes, trends, and gaps, providing a cohesive narrative. Why are references important in a literature review?References provide evidence for your review, ensure academic integrity, and allow readers to locate the original sources. What role do appendices play in a literature review?Appendices include supplementary material like tables or detailed methodologies that support the review but are too extensive for the main text.  Text prompt 10 Examples of Public speaking 20 Examples of Gas lighting  How to Prepare a Research Proposal and Literature ReviewAll HDR candidates are required to prepare a research proposal and literature review for their first Research Progress Review. If you are a PhD candidate, this will be your Confirmation Review. Your research proposal and literature review should be a comprehensive outline of your research topic and show how you will make an original contribution to knowledge in your field. Your Review panel will use your research proposal and literature review to assess the viability of your research project, and to provide you with valuable feedback on your topic, methodology, research design, timeline and milestones. UNSW Academic Skills provides a detailed description of how to develop and structure your research proposal. Your Faculty and/or School may have particular requirements, and you should contact your Postgraduate Coordinator or your supervisor if you’re unsure of what is required. Additional ResourcesAll disciplinary areas A guide for writing thesis proposals - UNSW Academic Skills Confirmation – not as big a deal as you think it is? - the Thesis Whisperer Humanities and Social Sciences Essential ingredients of a good research proposal for undergraduate and postgraduate students in the social sciences – Raymond Talinbe Abdulai and Anthony Owusu-Ansah, SAGE Open, Jul-Sep 2014 Template for writing your PhD Confirmation document in Sociology and Anthropology - S A Hamed Hosseini Science, Technology, Engineering and Medicine How to prepare a research proposal – Asya Al-Riyami, Oman Medical Journal Writing a scientific research proposal – author unknown  - Find a degree

- Ask a Question

- Getting Started

- International

- Find a Researcher/Area

- Apply for a Higher Degree Research Program

- UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia

- Telephone +61 2 9385 5500

- Maps

Graduate Research School, Level 2, Rupert Myers Building (South Wing), UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia Telephone +61 2 93855500 Dean of Graduate Research, Professor Jonathan Morris. UNSW CRICOS Provider Code: 00098G TEQSA Provider ID : PRV12055 ABN: 57 195 873 179 Log in using your username and password- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-8130 Parveen Ali 3 , 4

- 1 Memorial University of Newfoundland , St John's , Newfoundland , Canada

- 2 Swat College of Nursing , Pakistan

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , South Yorkshire , UK

- 4 Sheffield University Interpersonal Violence Research Group , Sheffield University , Sheffield , UK

- Correspondence to Ahtisham Younas, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John's, NL A1C 5C4, Canada; ay6133{at}mun.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103417 Statistics from Altmetric.comRequest permissions. If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways. IntroductionLiterature reviews offer a critical synthesis of empirical and theoretical literature to assess the strength of evidence, develop guidelines for practice and policymaking, and identify areas for future research. 1 It is often essential and usually the first task in any research endeavour, particularly in masters or doctoral level education. For effective data extraction and rigorous synthesis in reviews, the use of literature summary tables is of utmost importance. A literature summary table provides a synopsis of an included article. It succinctly presents its purpose, methods, findings and other relevant information pertinent to the review. The aim of developing these literature summary tables is to provide the reader with the information at one glance. Since there are multiple types of reviews (eg, systematic, integrative, scoping, critical and mixed methods) with distinct purposes and techniques, 2 there could be various approaches for developing literature summary tables making it a complex task specialty for the novice researchers or reviewers. Here, we offer five tips for authors of the review articles, relevant to all types of reviews, for creating useful and relevant literature summary tables. We also provide examples from our published reviews to illustrate how useful literature summary tables can be developed and what sort of information should be provided.  Tip 1: provide detailed information about frameworks and methods- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Tabular literature summaries from a scoping review. Source: Rasheed et al . 3 The provision of information about conceptual and theoretical frameworks and methods is useful for several reasons. First, in quantitative (reviews synthesising the results of quantitative studies) and mixed reviews (reviews synthesising the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies to address a mixed review question), it allows the readers to assess the congruence of the core findings and methods with the adapted framework and tested assumptions. In qualitative reviews (reviews synthesising results of qualitative studies), this information is beneficial for readers to recognise the underlying philosophical and paradigmatic stance of the authors of the included articles. For example, imagine the authors of an article, included in a review, used phenomenological inquiry for their research. In that case, the review authors and the readers of the review need to know what kind of (transcendental or hermeneutic) philosophical stance guided the inquiry. Review authors should, therefore, include the philosophical stance in their literature summary for the particular article. Second, information about frameworks and methods enables review authors and readers to judge the quality of the research, which allows for discerning the strengths and limitations of the article. For example, if authors of an included article intended to develop a new scale and test its psychometric properties. To achieve this aim, they used a convenience sample of 150 participants and performed exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the same sample. Such an approach would indicate a flawed methodology because EFA and CFA should not be conducted on the same sample. The review authors must include this information in their summary table. Omitting this information from a summary could lead to the inclusion of a flawed article in the review, thereby jeopardising the review’s rigour. Tip 2: include strengths and limitations for each articleCritical appraisal of individual articles included in a review is crucial for increasing the rigour of the review. Despite using various templates for critical appraisal, authors often do not provide detailed information about each reviewed article’s strengths and limitations. Merely noting the quality score based on standardised critical appraisal templates is not adequate because the readers should be able to identify the reasons for assigning a weak or moderate rating. Many recent critical appraisal checklists (eg, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) discourage review authors from assigning a quality score and recommend noting the main strengths and limitations of included studies. It is also vital that methodological and conceptual limitations and strengths of the articles included in the review are provided because not all review articles include empirical research papers. Rather some review synthesises the theoretical aspects of articles. Providing information about conceptual limitations is also important for readers to judge the quality of foundations of the research. For example, if you included a mixed-methods study in the review, reporting the methodological and conceptual limitations about ‘integration’ is critical for evaluating the study’s strength. Suppose the authors only collected qualitative and quantitative data and did not state the intent and timing of integration. In that case, the strength of the study is weak. Integration only occurred at the levels of data collection. However, integration may not have occurred at the analysis, interpretation and reporting levels. Tip 3: write conceptual contribution of each reviewed articleWhile reading and evaluating review papers, we have observed that many review authors only provide core results of the article included in a review and do not explain the conceptual contribution offered by the included article. We refer to conceptual contribution as a description of how the article’s key results contribute towards the development of potential codes, themes or subthemes, or emerging patterns that are reported as the review findings. For example, the authors of a review article noted that one of the research articles included in their review demonstrated the usefulness of case studies and reflective logs as strategies for fostering compassion in nursing students. The conceptual contribution of this research article could be that experiential learning is one way to teach compassion to nursing students, as supported by case studies and reflective logs. This conceptual contribution of the article should be mentioned in the literature summary table. Delineating each reviewed article’s conceptual contribution is particularly beneficial in qualitative reviews, mixed-methods reviews, and critical reviews that often focus on developing models and describing or explaining various phenomena. Figure 2 offers an example of a literature summary table. 4 Tabular literature summaries from a critical review. Source: Younas and Maddigan. 4 Tip 4: compose potential themes from each article during summary writingWhile developing literature summary tables, many authors use themes or subthemes reported in the given articles as the key results of their own review. Such an approach prevents the review authors from understanding the article’s conceptual contribution, developing rigorous synthesis and drawing reasonable interpretations of results from an individual article. Ultimately, it affects the generation of novel review findings. For example, one of the articles about women’s healthcare-seeking behaviours in developing countries reported a theme ‘social-cultural determinants of health as precursors of delays’. Instead of using this theme as one of the review findings, the reviewers should read and interpret beyond the given description in an article, compare and contrast themes, findings from one article with findings and themes from another article to find similarities and differences and to understand and explain bigger picture for their readers. Therefore, while developing literature summary tables, think twice before using the predeveloped themes. Including your themes in the summary tables (see figure 1 ) demonstrates to the readers that a robust method of data extraction and synthesis has been followed. Tip 5: create your personalised template for literature summariesOften templates are available for data extraction and development of literature summary tables. The available templates may be in the form of a table, chart or a structured framework that extracts some essential information about every article. The commonly used information may include authors, purpose, methods, key results and quality scores. While extracting all relevant information is important, such templates should be tailored to meet the needs of the individuals’ review. For example, for a review about the effectiveness of healthcare interventions, a literature summary table must include information about the intervention, its type, content timing, duration, setting, effectiveness, negative consequences, and receivers and implementers’ experiences of its usage. Similarly, literature summary tables for articles included in a meta-synthesis must include information about the participants’ characteristics, research context and conceptual contribution of each reviewed article so as to help the reader make an informed decision about the usefulness or lack of usefulness of the individual article in the review and the whole review. In conclusion, narrative or systematic reviews are almost always conducted as a part of any educational project (thesis or dissertation) or academic or clinical research. Literature reviews are the foundation of research on a given topic. Robust and high-quality reviews play an instrumental role in guiding research, practice and policymaking. However, the quality of reviews is also contingent on rigorous data extraction and synthesis, which require developing literature summaries. We have outlined five tips that could enhance the quality of the data extraction and synthesis process by developing useful literature summaries. - Aromataris E ,

- Rasheed SP ,

Twitter @Ahtisham04, @parveenazamali Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Competing interests None declared. Patient consent for publication Not required. Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. Read the full text or download the PDF:Literature Review: Conducting & Writing- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication ArtsHave an exemplary literature review. - Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes? Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post? Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged. - << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples) The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples. Why you need an introduction for a literature reviewIn academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review. It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section . When you need an introduction for a literature reviewThere are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review: What to include in a literature review introductionIt is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work. Academic literature review paperThe introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass: Regular literature review section in an academic article or essayIn a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass: Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertationSome students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements: Examples of literature review introductionsExample 1: an effective introduction for an academic literature review paper. To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision. Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paperThe second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment. Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation. Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chaptersNumerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers. Master’s thesis literature review introductionPhd thesis literature review chapter introduction. The second example is Deep Learning on Semi-Structured Data and its Applications to Video-Game AI, Woof, W. (Author). 31 Dec 2020, a PhD thesis completed at the University of Manchester . In Chapter 2, the author offers a comprehensive introduction to the topic in four paragraphs, with the final paragraph serving as an overview of the chapter’s structure: PhD thesis literature review introductionThe last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records. Steps to write your own literature review introductionMaster academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, the best answers to "what are your plans for the future", 10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles, introduce yourself in a phd interview (4 simple steps + examples), how to disagree with reviewers (with examples), 75 linking words for academic writing (+examples).  An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely. - Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now . - Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

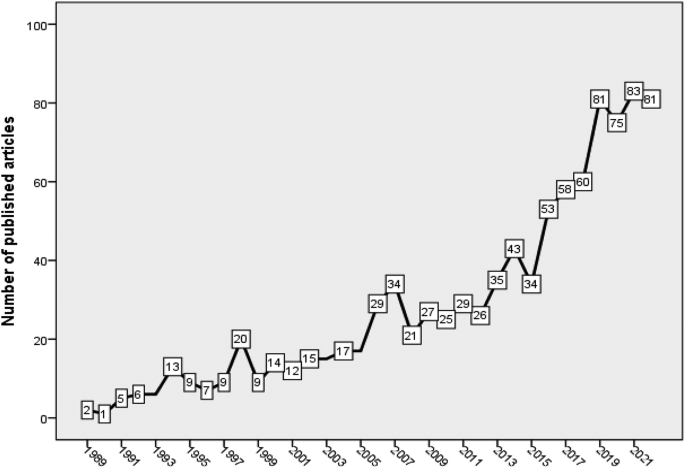

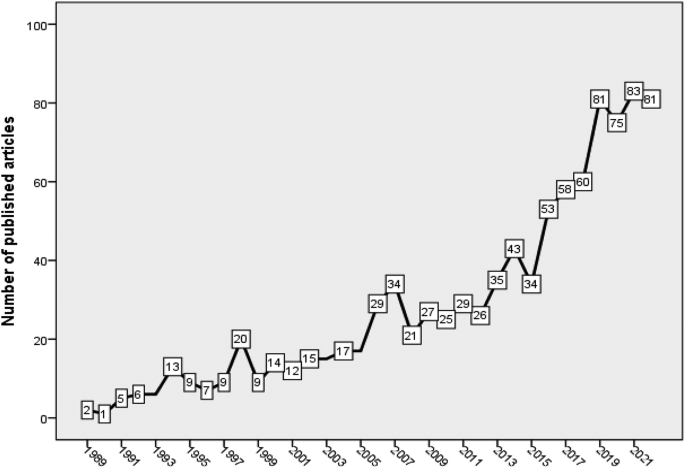

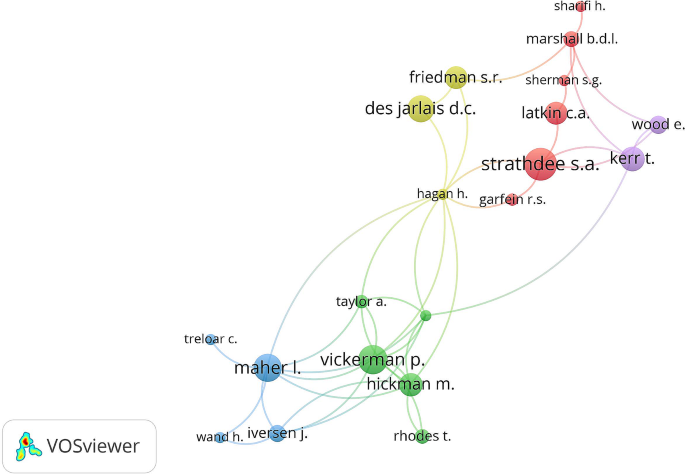

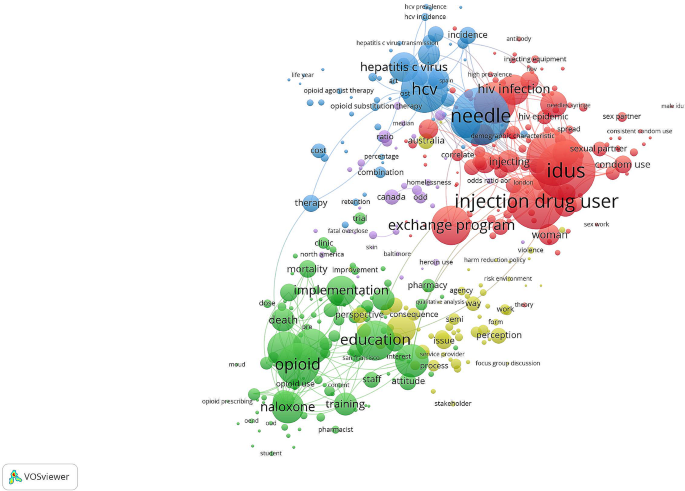

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature ReviewMarco pautasso. 1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France 2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] . When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review. Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors. Rule 1: Define a Topic and AudienceHow to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be: - interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.). Rule 2: Search and Re-search the LiteratureAfter having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here: - keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,  The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] . - discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply: - be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While ReadingIf you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review. Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time. Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to WriteAfter having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs. There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] . Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad InterestWhether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas. While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines. Rule 6: Be Critical and ConsistentReviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of: - the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense. Rule 7: Find a Logical StructureLike a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] . How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] . Rule 8: Make Use of FeedbackReviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form. Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] . Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be ObjectiveIn many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it. In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors. Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older StudiesGiven the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society. Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature. AcknowledgmentsMany thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft. Funding StatementThis work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.  How To Structure Your Literature Review3 options to help structure your chapter. By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023) Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should: - Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).  But wait – is this the right time?Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter. In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research. Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess. Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write. Need a helping hand? Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion . Let’s take a closer look at each of these. 1: The Introduction SectionJust like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead. Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:  Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies). Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .  2: The Body SectionThe body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way. The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly). There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.  Option 1: Chronological (according to date)Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward. The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .  For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages. Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically. - What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ). Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome). As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields. For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.  Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes: - Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here. Option 3: MethodologicalThe methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies. Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.  For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies. Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology: - Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion SectionOnce you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis. The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified. Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.  Example: Thematically Structured ReviewIn the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice. Let’s RecapIn this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure: - Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.  Psst… there’s more!This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this . 27 Comments Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?  I agree with you Marin… A great piece  I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.  Awesome article for my research.  I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide  It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students  Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you  Great work, very insightful. Thank you.  Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?  Thank you very much, very helpful  This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .  Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.  I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.  comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.  great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?  I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?  Beautifully clear.nThank you! Lucid! Thankyou!  Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks  I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊  Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!  You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.  Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach  I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.  I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?  You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!  I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it Submit a Comment Cancel replyYour email address will not be published. Required fields are marked * Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. - AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group