Anti-Federalist vs. Federalist

In U.S. history, anti-federalists were those who opposed the development of a strong federal government and the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, preferring instead for power to remain in the hands of state and local governments. Federalists wanted a stronger national government and the ratification of the Constitution to help properly manage the debt and tensions following the American Revolution . Formed by Alexander Hamilton , the Federalist Party, which existed from 1792 to 1824, was the culmination of American federalism and the first political party in the United States. John Adams, the second president of the United States, was the first and only Federalist president.

Comparison chart

| Anti-Federalist | Federalist | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | In U.S. history, anti-federalists were those who opposed the development of a strong federal government and the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, preferring instead for power to remain in the hands of state and local governments. | In U.S. history, federalists wanted a stronger national government and the ratification of the Constitution to help properly manage the debt and tensions following the American Revolution. |

| Position on Fiscal and Monetary Policy | Felt that states were free agents that should manage their own and spend their money as they saw fit. | Felt that many individual and different led to economic struggles and national weakness. Favored central banking and central financial policies. |

| Position on Constitution | Opposed until inclusion of the Bill of Rights. | Proposed and supported. |

| Prominent Figures | Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams. | Alexander Hamilton, , John Jay, John Adams. |

Anti-Federalist vs. Federalist Debate

The American Revolution was a costly war and left the colonies in an economic depression . The debt and remaining tensions—perhaps best summarized by a conflict in Massachusetts known as Shays' Rebellion —led some founding political members in the U.S. to desire for more concentrated federal power. The thought was that this concentrated power would allow for standardized fiscal and monetary policy and for more consistent conflict management.

However, a more nationalistic identity was the antithesis of some founding political members' ideals for the developing states. A more centralized American power seemed reminiscent of the monarchical power of the English crown that had so recently and controversially been defeated. The potential consequences of centralized fiscal and monetary policy were especially frightening for some, reminding them of burdensome and unfair taxation. Anti-federalists were closely tied to rural landowners and farmers who were conservative and staunchly independent.

The most important parts of this debate were decided in the 1700s and 1800s in U.S. history, and the Federalist Party dissolved centuries ago, but the battles between federalist and anti-federalist ideologies continue into the present day in left and right wing American politics . To better understand the history behind this ongoing ideological debate, watch the following video from author John Green's U.S. history Crash Course series.

Articles of Confederation

Prior to the Constitution, there was the Articles of Confederation, a 13-articled agreement between the 13 founding states that covered issues of state sovereignty, (theoretical) equal treatment of citizenry, congressional development and delegation, international diplomacy, armed forces, fund raising, supermajority lawmaking, the U.S.-Canadian relationship, and war debt.

The Articles of Confederation was a very weak agreement on which to base a nation—so weak, in fact, that the document never once refers to the United States of America as being part of a national government, but rather "a firm league of friendship" between states. This is where the concept of the "United States"—i.e., a group of roughly and ideologically united, individually ruling bodies—comes from in the naming of the country. The Articles of Confederation took years for the 13 states to ratify, with Virginia being the first to do so in 1777 and Maryland being the last in 1781.

With the Articles of Confederation, Congress became the only form of federal government, but it was crippled by the fact that it could not fund any of the resolutions it passed. While it could print money, there was no solid regulation of this money, which led to swift and deep depreciation . When Congress agreed to a certain rule, it was primarily up to the states to individually agree to fund it, something they were not required to do. Though Congress asked for millions of dollars in the 1780s, they received less than 1.5 million over the course of three years, from 1781 to 1784.

This inefficient and ineffective governance led to economic woes and eventual, if small scale, rebellion. As George Washington 's chief of staff, Alexander Hamilton saw firsthand the problems caused by a weak federal government, particularly those which stemmed from a lack of centralized fiscal and monetary policies. With Washington's approval, Hamilton assembled a group of nationalists at the 1786 Annapolis Convention (also known as the "Meeting of Commissioners to Remedy Defects of the Federal Government"). Here, delegates from several states wrote a report on the conditions of the federal government and how it needed to be expanded if it was to survive its domestic turmoil and international threats as a sovereign nation.

Constitution

In 1788, the Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation, greatly expanding the powers of the federal government. With its current 27 amendments, the U.S. Constitution remains the supreme law of the United States of America, allowing it to define, protect, and tax its citizenry. Its development and relatively quick ratification was perhaps just as much the result of widespread dissatisfaction with a weak federal government as it was support for the constitutional document.

Federalists, those who identified with federalism as part of a movement, were the main supporters of the Constitution. They were aided by a federalist sentiment that had gained traction across many factions, uniting political figures. This does not mean there was no heated debate over the Constitution's drafting, however. The most zealous anti-federalists, loosely headed by Thomas Jefferson, fought against the Constitution's ratification, particularly those amendments which gave the federal government fiscal and monetary powers.

A sort of ideological war raged between the two factions, resulting in the Federalist Papers and the Anti-Federalist Papers , a series of essays written by various figures—some anonymously, some not—for and against the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

Ultimately, anti-federalists greatly influenced the document, pushing for strict checks and balances and certain limited political terms that would keep any one branch of the federal government from holding too much power for too long. The Bill of Rights , the term used for the first 10 amendments of the Constitution, are especially about personal, individual rights and freedoms; these were included partly to satisfy anti-federalists.

Prominent Anti-Federalists and Federalists

Among anti-federalists, some of the most prominent figures were Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe . Jefferson was often considered a leader among the anti-federalists. Other prominent anti-federalists included Samuel Adams , Patrick Henry , and Richard Henry Lee .

Alexander Hamilton, a former chief of staff to George Washington, was a proponent of a strong federal government and founded the Federalist Party. He helped oversee the development of a national bank and a taxation system. Other prominent federalists of the time included John Jay and John Adams .

Other figures, such as James Madison , greatly supported Hamilton's federalist intentions for a constitution and national identity, but disagreed with his fiscal policies and were more likely to side with anti-federalists on matters of money. Without Madison's influence, which included acceptance of anti-federalists' desire for a bill of rights, it is unlikely that the U.S. Constitution would have been ratified.

Quotes From Anti-Federalists and Federalists

- "One can hardly expect the state legislatures to take enlightened views on national affairs." —James Madison, Federalist

- "You say that I have been dished up to you as an Anti-Federalist, and ask me if it be just. My opinion was never worthy enough of notice to merit citing; but, since you ask it, I will tell it to you. I am not a Federalist, because I never submitted the whole system of my opinions to the creed of any party of men whatever, in religion, in philosophy, in politics, or in anything else, where I was capable of thinking for myself. Such an addiction is the last degradation of a free and moral agent. If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all. Therefore, I am not of the party of Federalists." —Thomas Jefferson, Anti-Federalist

- "...that if we are in earnest about giving the Union energy and duration, we must abandon the vain project of legislating upon the States in their collective capacities; we must extend the laws of the federal government to the individual citizens of America; we must discard the fallacious scheme of quotas and requisitions, as equally impracticable and unjust." —Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper No. 23

- "Congress, or our future lords and masters, are to have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises. Excise is a new thing in America, and few country farmers and planters know the meaning of it." —A Farmer and Planter (pseudonym) in Anti-Federalist Paper No. 26

- "Nothing is more certain than the indispensable necessity of government, and it is equally undeniable, that whenever and however it is instituted, the people must cede to it some of their natural rights in order to vest it with requisite powers." —John Jay in Federalist Paper No. 2

- "This being the beginning of American freedom, it is very clear the ending will be slavery, for it cannot be denied that this constitution is, in its first principles , highly and dangerously oligarchical; and it is every where agreed, that a government administered by a few, is, of all governments, the worst." —Leonidas (pseudonym) in Anti-Federalist Paper No. 48

- "It is, that in a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person: in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, must be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region." —James Madison in Federalist Paper No. 14

- 7 quotes from the Federalist Papers - Constitution Center

- American Federalism: Past, Present, and Future - Issues of Democracy

- Anti-Federalists - U.S. History

- Quotes from The Essential Anti-Federalist Papers (PDF) by Bill Bailey

- Federalism - U.S. History

- Federalists - U.S. History

- Thomas Jefferson Exhibition - Library of Congress

- Thomas Jefferson on the New Constitution - Encyclopedia Britannica

- Wikipedia: Articles of Confederation

- Wikipedia: Timeline of drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution

- Wikipedia: U.S. Constitution

- Wikipedia: United States Bill of Rights#The Anti-Federalists

- Wikipedia: Anti-Federalism

- Wikipedia: Federalism in the United States

- Wikipedia: Federalist#United States

- Wikipedia: Federalist Era

- Wikipedia: Federalist Party

Related Comparisons

Share this comparison via:

If you read this far, you should follow us:

"Anti-Federalist vs Federalist." Diffen.com. Diffen LLC, n.d. Web. 6 Jul 2024. < >

Comments: Anti-Federalist vs Federalist

- Joe Biden vs Donald Trump

- Revolutionary War vs Civil War

- Democracy vs Republic

- Abraham Lincoln vs George Washington

- Left Wing vs Right Wing

- Conservative vs Liberal

- Democrat vs Republican

- Democrat vs Libertarian

Edit or create new comparisons in your area of expertise.

Stay connected

© All rights reserved.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — History of Taekwondo — Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: The Debate Over the Constitution

Federalists Vs. Anti-federalists: The Debate Over The Constitution

- Categories: Civil Rights Movement History of Taekwondo Social Justice

About this sample

Words: 830 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 830 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Table of contents

Origins of the debate, federalist arguments, anti-federalist arguments, the compromise, legacy of the debate.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Life Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 710 words

1 pages / 584 words

2 pages / 774 words

2 pages / 888 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on History of Taekwondo

Play The Tempest has been the subject of much critical analysis over the years, with one of the most prominent themes being that of colonialism. The play, believed to have been written in the early 17th century, depicts the [...]

Feudalism in ancient China was a complex and multifaceted system that played a crucial role in shaping the social, economic, and political landscape of the region for centuries. This hierarchical system, characterized by the [...]

In today's competitive job market and social landscape, personal branding has become an essential tool for individuals to distinguish themselves and stand out from the crowd. Personal branding is the practice of marketing [...]

Julius Caesar is a figure of immense historical significance, known for his role in the downfall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His actions and policies have sparked debate among historians and scholars, [...]

Taekwondo is a martial art form that was founded on April 11, 1955, by the South Korean army general Choi Hong Hee. In Korean Tae (Tae) means kicking, Quon means fist or hand kicks, Do is the way. So there are two components of [...]

I look back at tennis as a very memorable and important part of my life. Being on a team is something that everyone should experience at least once; you will not get far in life if you cannot manage to work on a team. Working [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The Federalist and Anti-Federalist factions developed during the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Alexander Hamilton was a prominent leader of the Federalist faction. Image Source: Wikipedia.

Federalists and Anti-Federalists Summary

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists were two factions that emerged in American politics during the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 . The original purpose of the Convention was to discuss problems with the government under the Articles of Confederation and find reasonable solutions. Instead of updating the Articles, the delegates replaced the Articles with something entirely new — the Constitution of the United States. Despite the development of the Constitution, there was disagreement. The people who favored the Constitution became known as Federalists. Those who disagreed, or even opposed it, were called Anti-Federalists. Anti-Federalists argued the Constitution failed to provide details regarding basic civil rights — a Bill of Rights — while Federalists argued the Constitution provided significant protection for individual rights. After the Constitution was adopted by the Convention, it was sent to the individual states for ratification. The ensuing debate between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists that followed remains of the great debates in American history, and eventually led to the ratification of the United States Constitution.

Quick Facts About Federalists

- The name “Federalists” was adopted by people who supported the ratification of the new United States Constitution.

- Federalists favored a strong central government and believed the Constitution provided adequate protection for individual rights.

- The group was primarily made up of large property owners, merchants, and businessmen, along with the clergy, and others who favored consistent law and order throughout the states.

- Prominent Federalists were James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay .

- During the debate on the Constitution, the Federalists published a series of articles known as the “Federalists Papers” that argued for the passage of the Constitution.

- The Federalists eventually formed the Federalist Party in 1791 .

Quick Facts About Anti-Federalists

- Anti-Federalists had concerns about a central government that had too much power.

- They favored the system of government under the Articles of Confederation but were adamant the Constitution needed a defined Bill of Rights.

- The Anti-Federalists were typically small farmers, landowners, independent shopkeepers, and laborers.

- Prominent Anti-Federalists were Patrick Henry , Melancton Smith, Robert Yates, George Clinton , Samuel Bryan, and Richard Henry Lee .

- The Anti-Federalists delivered speeches and wrote pamphlets that explained their positions on the Constitution. The pamphlets are collectively known as the “Anti-Federalist Papers.”

- The Anti-Federalists formed the Democratic-Republican Party in 1792 .

Significance of Federalists and Anti-Federalists

The Federalists and Anti-Federalists are important to the history of the United States because their differences over the United States Constitution led to its ratification and the adoption of the Bill of Rights — the first 10 Amendments .

Learn More About Federalists and Anti-Federalists on American History Central

- Federalist No. 1

- Federalist No. 2

- Federalist No. 3

- Alexander Hamilton’s Speech to the New York Convention

- Articles of Confederation

- Presidency of George Washington — Study Guide

- Written by Randal Rust

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or anti-federalist.

Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers . We look forward to exploring this important debate with you!

One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification of the Constitution in 1787-1788. Those who supported the Constitution and a stronger national republic were known as Federalists. Those who opposed the ratification of the Constitution in favor of small localized government were known as Anti-Federalists. Both the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists were concerned with the preservation of liberty, however, they disagreed over whether or not a strong national government would preserve or eventually destroy the liberty of the American people. Today, it is easy to accept that the prevailing side was right and claim that, had you been alive, you would have certainly supported ratifying the Constitution. However, in order to develop a deeper understanding of the ideological foundations upon which our government is built, it is important to analyze both the Federalist and Anti-Federalist arguments.

The Anti-Federalists were not as organized as the Federalists. They did not share one unified position on the proper form of government. However, they did unite in their objection to the Constitution as it was proposed for ratification in 1787. The Anti-Federalists argued against the expansion of national power. They favored small localized governments with limited national authority as was exercised under the Articles of Confederation. They generally believed a republican government was only possible on the state level and would not work on the national level. Therefore, only a confederacy of the individual states could protect the nation’s liberty and freedom. Another, and perhaps their most well-known concern, was over the lack of a bill of rights. Most Anti-Federalists feared that without a bill of rights, the Constitution would not be able to sufficiently protect the rights of individuals and the states. Perhaps the strongest voice for this concern was that of George Mason. He believed that state bills of right would be trumped by the new constitution, and not stand as adequate protections for citizens’ rights. It was this concern that ultimately led to the passing of the bill of rights as a condition for ratification in New York, Virginia, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

The Federalists, primarily led by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, believed that establishing a large national government was not only possible, but necessary to “create a more perfect union” by improving the relationship among the states. Until this point, the common belief was that a republic could only function efficiently it was small and localized. The Federalists challenged this belief and claimed that a strong national republic would better preserve the individual liberties of the people. By extending the sphere of the republic, individual and minority rights would be better protected from infringement by a majority. The federalists also wanted to preserve the sovereignty and structure of the states. To do so, they advocated for a federal government with specific, delegated powers. Anything not delegated to the federal government would be reserved to the people and the states. Ultimately, their goal was to preserve the principle of government by consent. By building a government upon a foundation of popular sovereignty, without sacrificing the sovereignty of the states, legitimacy of the new government could be secured.

Today, it appears that the government established by the Constitution is an improvement from that which was established by the Articles of Confederation. At the time however, the Constitution was merely an experiment. Forget what you now know about the success Constitution. Considering its unprecedented nature and the fear that a strong national government would be a threat to personal liberty, would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Learn more about Federalist papers.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, the anti-federalists and their important role during the ratification fight.

September 27, 2017 | by Ugonna Eze

On this day in 1787, the debate over the newly written Constitution began in the press after an anonymous writer in the New York Journal warned citizens that the document was not all that it seemed.

Most Americans know of the Federalist Papers, the collection of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and Madison, in defense of the U.S. Constitution. Fewer know of the Anti-Federalist Papers authored by Cato and other incognito writers, their significance to American political history, or their responsibility for producing the Bill of Rights.

When the Constitution was drafted in the summer of 1787, its ratification was far from certain; it still needed to be ratified by at least nine of the 13 state legislatures. The failure of the Articles of Confederation made it clear that America needed a new form of government. Yet there was worry that the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government. The original draft of the Constitution did not have a Bill of Rights, declared all state laws subservient to federal ones, and created a king-like office in the presidency. At the Philadelphia Convention and in the Federalist Papers, James Madison argued against having a Bill of Rights, fearing that they would limit the people’s rights.

Opposition to the Constitution after the Philadelphia Convention began with Elbridge Gerry, Edmund Randolph, and George Mason, the “Three Dissenters” who refused to sign the document. It then grew to include Patrick Henry, Samuel Adams, and Richard Henry Lee, heroes of the Revolutionary War who objected to the Constitution’s consolidation of power. In time, the various opponents to the new Constitution came to be known as the Anti-Federalists. Their collected speeches, essays, and pamphlets later became known as the “Anti-Federalist Papers.”

While each of the Anti-Federalists had their own view for what a new constitution for the United States should look like, they generally agreed on a few things. First, they believed that the new Constitution consolidated too much power in the hands of Congress, at the expense of states. Second, they believed that the unitary president eerily resembled a monarch and that that resemblance would eventually produce courts of intrigue in the nation’s capital. Third, they believed that the liberties of the people were best protected when power resided in state governments, as opposed to a federal one. Lastly, they believed that without a Bill of Rights, the federal government would become tyrannous.

These arguments created a powerful current against adopting the Constitution in each of the states. In state legislatures across the country, opponents of the Constitution railed against the extensive powers it granted the federal government and its detraction from the republican governments of antiquity. In Virginia, Patrick Henry, author of the famous “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech, called the proposed constitution, “A revolution as radical as that which separated us from Great Britain.” In the Essays of Brutus, an anonymous author worried that without any limitations, the proposed Constitution would make “the state governments… dependent on the will of the general government for their existence.”

The Anti-Federalists mobilized against the Constitution in state legislatures across the country.

Anti-Federalists in Massachusetts, Virginia and New York, three crucial states, made ratification of the Constitution contingent on a Bill of Rights. In Massachusetts, arguments between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists erupted in a physical brawl between Elbridge Gerry and Francis Dana. Sensing that Anti-Federalist sentiment would sink ratification efforts, James Madison reluctantly agreed to draft a list of rights that the new federal government could not encroach.

The Bill of Rights is a list of 10 constitutional amendments that secure the basic rights and privileges of American citizens. They were fashioned after the English Bill of Rights and George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights. They include the right to free speech, the right to a speedy trial, the right to due process under the law, and protections against cruel and unusual punishments. To accommodate Anti-Federalist concerns of excessive federal power, the Bill of Rights also reserves any power that is not given to the federal government to the states and to the people.

Since its adoption, the Bill of Rights has become the most important part of the Constitution for most Americans. In Supreme Court cases, the Amendments are debated more frequently than the Articles. They have been cited to protect the free speech of Civil Rights activists, protect Americans from unlawful government surveillance, and grant citizens Miranda rights during arrest. It is impossible to know what our republic would look like today without the persistence of the Anti-Federalists over two hundred years ago.

Ugonna Eze is a Fellow for Constitutional Studies at the National Constitution Center.

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

- Location, Hours & Parking

- Transportation Grants

- Our Mission

- Board and Officers

- Teacher Advisory Council

- The Courthouse

- The Federal Courts

- Photo Gallery Tour

- Schedule a Tour

- Summer Teacher Institute

- The Supreme Court and My Hometown

- Citizenship in the Nation for Scouts

- Girl Scout Day at the Courthouse

- Bill of Rights Day 2024 Contest

- Student Art Competition 2024 Winners

- Tinker v. Des Moines Exhibit

- Program Photos

- Student Center Landing Page

- The Role of the Federal Courts

- Organization of the Federal Courts

- How Courts Work

- Landmark Cases

- Educator Center Main Page

- Online Learning Resources

- Comparing State and Federal Courts

- Law Day Lessons and Activities

- The Ratification Debate

Ratifying the Constitution

Once the Constitution of the United States was written in 1787 at the Philadelphia convention, the next step was ratification. This is the formal process, outlined in Article VII, which required that nine of the thirteen states had to agree to adopt the Constitution before it could go into effect.

As in any debate there were two sides, the Federalists who supported ratification and the Anti-Federalists who did not.

We now know that the Federalists prevailed, and the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, and went into effect in 1789. Read about their arguments below.

- Anti-Federalist Debate

- Federalist Debate

Those opposed to the Constitution

Anti-Federalists argued that the Constitution gave too much power to the federal government, while taking too much power away from state and local governments. Many felt that the federal government would be too far removed to represent the average citizen. Anti-Federalists feared the nation was too large for the national government to respond to the concerns of people on a state and local basis.

The Anti-Federalists were also worried that the original text of the Constitution did not contain a bill of rights. They wanted guaranteed protection for certain basic liberties, such as freedom of speech and trial by jury .

A Bill of Rights was added in 1791. In part to gain the support of the Anti-Federalists, the Federalists promised to add a bill of rights if the Anti-Federalists would vote for the Constitution. Learn more about it by visiting the Student Center page on The Constitution and Rights .

Those in favor of the Constitution

Federalists believed that the nation might not survive without the passage of the Constitution, and that a stronger national government was necessary after the failed Articles of Confederation.

The Federalists met Anti-Federalist arguments that the new government created by the Constitution was too powerful by explaining that the document had many built-in safeguards, such as:

- Limited Government : Federalists argued that the national government only had the powers specifically granted to it under the Constitution, and was prohibited from doing some things at all.

- Separation of Powers : Federalists argued that, by separating the basic powers of government into three equal branches and not giving too much power to any one person or group, the Constitution provided balance and prevented the potential for tyranny.

- Checks and Balances : Federalists argued that the Constitution provided a system of checks and balances, where each of the three branches is able to check or limit the other branches.

How did the Anti-Federalists feel about the federal courts?

Similar to how they felt about the rest of the proposed federal government, the Anti-Federalists believed the Constitution granted too much power to the federal courts, at the expense of the state and local courts. They argued that the federal courts would be too far away to provide justice to the average citizen.

How did the Federalists feel about the federal courts?

The Federalists argued that the federal courts had limited jurisdiction, leaving many areas of the law to the state and local courts. The Federalists felt that the new federal courts were necessary to provide checks and balances on the power of the other two branches of government. They believed the federal courts would protect citizens from government abuse, and guarantee their liberty.

Courts today

Federalism is a form of government in which power is divided between the national government and the state governments. In the United States, there is a federal court system. In addition, each state has its own courts. To learn more about this dual court system, visit the Student Center page State Courts vs. Federal Courts.

U.S. Constitution.net

Constitutional topic: the federalists and anti-federalists – the u.s. constitution online – usconstitution.net, constitutional topic: the federalists and anti-federalists.

The Constitutional Topics pages at the USConstitution.net site are presented to delve deeper into topics than can be provided on the Glossary Page or in the FAQ pages . This Topic Page concerns the Federalists versus the Anti-Federalists and the struggle for ratification. Generally speaking, the federalists were in favor of ratification of the Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists were opposed. Note the the Anti-Federalists are often referred to as just Antifederalists (without the hyphen). Either form is generally acceptable.

Other pages of interest would include: Ratification Timeline , Ratification Documents , Ratification Dates and Votes .

After the Constitutional Convention , the fight for the Constitution had just begun. According to Article 7 , conventions in nine states had to ratify the Constitution before it would become effective. Some states were highly in favor of the new Constitution, and within three months, three states, Delaware (with a vote of 30-0), Pennsylvania (46-23), and New Jersey (38-0), had ratified it. Georgia (26-0) and Connecticut (128-40) quickly followed in January, 1788 (for the exact dates of ratification, see The Timeline ).

More than half-way there in four months, one might think that the battle was nearly won. But the problem was not with the states that ratified quickly, but with the key states in which ratification was not as certain. Massachusetts, New York, and Virginia were key states, both in terms of population and stature. Debates in Massachusetts were very heated, with impassioned speeches from those on both sides of the issue. Massachusetts was finally won, 187-168, but only after assurances to opponents that the Constitution could have a bill of rights added to it.

After Massachusetts, the remaining states required for ratification did so within a few months, with Maryland (63-11) and South Carolina (149-73) falling in line, and New Hampshire (57-47) casting the deciding vote to reach the required nine states. New York and Virginia still remained, however, and many doubted that the new Constitution could survive without these states.

New York and Virginia

Early in the ratification process, the proponents of the Constitution took the name “Federalists.”

Though those who opposed the Constitution actually wanted a more purely federal system (as the Articles provided), they were more or less forced into taking the name “Anti-Federalists.” These men had many reasons to oppose the Constitution. They did not feel that a republican form of government could work on a national scale. They also did not feel that the rights of the individual were properly or sufficiently protected by the new Constitution. They saw themselves as the true heirs of the spirit of the Revolution. Some very notable persons in United States history counted themselves Anti-Federalists, like Patrick Henry, Thomas Paine, George Mason, George Clinton, and Luther Martin.

There were some true philosophical differences between the two camps. In many instances, though, there was also a lot of personal animosity. For example, in New York, George Clinton was a political opponent of John Jay, a prominent Federalist, and also disliked Alexander Hamilton. And in Virginia, Patrick Henry was a political rival of James Madison.

In addition, many letters were written to newspapers under various pseudonyms, like “The Federal Farmer,” “Cato,” “Brutus,” and “Cincinnatus.” These letters and several speeches are now known as “The Anti-Federalist Papers.”

In response to the speeches and letters of the Anti-Federalists, the Federalists gave their own speeches and wrote their own letters. John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison coordinated their efforts and wrote a series of 85 letters under the name “Publius.” These letters both explained the new Constitution and answered the charges of the Anti-Federalists. The letters were collected into a volume called “The Federalist,” or “The Federalist Papers.” Though the influence of The Federalist at the time is questionable, the letters are noted today as classics in political theory. Perhaps of far greater importance were the Federalist stances of George Washington and Ben Franklin, very prominent men both in their day and today. Their opinions carried great weight.

The votes in Virginia and New York were hard-won, and close. Virginia voted 89-79, and New York , a month later, voted 30-27 to ratify. With all the major states now having ratified, confidence was high that the United States under the Constitution would be a success, or, at least, have a fighting chance. The new Congress met, and George Washington became the first President. As suggested by many of the ratifying conventions, one of the first tasks tackled was the writing of a Bill of Rights to be attached to the Constitution. The Bill, Amendments 1-10, eased the minds of many hold-outs. Shortly thereafter, North Carolina ratified (194-77), and lone hold-out, Rhode Island , finally relented and ratified on a close 34-32 vote.

The Federalists were successful in their effort to get the Constitution ratified by all 13 states. The Federalists later established a party known as the Federalist Party. The party backed the views of Hamilton and was a strong force in the early United States. The party, however, was short-lived, dead by 1824.

The Anti-Federalists generally gravitated toward the views of Thomas Jefferson, coalescing into the Republican Party, later known as the Democratic Republicans, the precursor to today’s Democratic Party.

The Arguments

One of the most succinct enumeration of the arguments of the Anti-Federalists against the Constitution is found in a letter commonly known as Anti-Federalist number 44. The author anonymously signed the letter “Deliberator.” The author listed several points raised by a Federalist in another letter published anonymously in the Pennsylvania Packet under the name Freeman. Most of the points made by Deliberator have actually proven true over time. For example, Freeman argued that the federal government could not train the militia — our modern National Guard, the descendant of their militia, is trained by the federal government. Freeman also noted that the federal government would not be permitted to inspect “the produce of the country”, but our modern system of inspection of everything from food to drugs to cars has shown Freeman to be wrong and Deliberator to be right.

The bulk of Deliberator’s letter is not a refutation of Freeman’s letter, though, but a list of the features of the Constitution that Deliberator, and many other Anti-Federalists, objected to. These, along with commentary, are shown below.

· Congress may, even in time of peace, raise an army of 100,000 men, whom they may canton through the several states, and billet out on the inhabitants, in order to serve as necessary instruments in executing their decrees.

Today’s modern military would probably alarm even the most strident Federalist, but our military evolved with time and most Americans cannot imagine the world without a strong national military. The Anti-Federalist concern about billeting, however, is addressed in the 3rd Amendment .

· Upon the inhabitants of any state proving refractory to the will of Congress, or upon any other pretense whatsoever, Congress may can out even all the militia of as many states as they think proper, and keep them in actual service, without pay, as long as they please, subject to the utmost rigor of military discipline, corporal punishment, and death itself not excepted.

History has shown some of this concern to be true — for example, when the governor of Arkansas refused to implement a Supreme Court decision regarding school desegregation, President Dwight Eisenhower sent in federal troops and federalized the Arkansas National Guard to enforce the ruling. The soldiers, however, were not unpaid, though they were subject to military discipline.

· Congress may levy and collect a capitation or poll tax, to what amount they shall think proper; of which the poorest taxable in the state must pay as much as the richest.

This is true — but the Congress has never imposed a direct (capitation) tax, and with the ratification of the 16th Amendment , there seems to be little need to be concerned with this point.

· Congress may, under the sanction of that clause in the constitution which empowers them to regulate commerce , authorize the importation of slaves, even into those states where this iniquitous trade is or may be prohibited by their laws or constitutions.

The Congress banned the importation of slaves as soon as it was constitutionally able to do so, in 1808. No state was required to allow slaves contrary to their own laws or constitutions, but the outcome of the Dred Scott case illustrates that this concern was real.

· Congress may, under the sanction of that clause which empowers them to lay and collect duties (as distinct from imposts and excises) impose so heavy a stamp duty on newspapers and other periodical publications, as shall effectually prevent all necessary information to the people through these useful channels of intelligence.

This was a real concern, especially considering the Stamp Act that the British has imposed on the colonies. However, no such tax was ever implemented and with the ratification of the 1st Amendment , such a tax probably would have been found unconstitutional by the courts.

· Congress may, by imposing a duty on foreigners coming into the country, check the progress of its population. And after a few years they may prohibit altogether, not only the emigration of foreigners into our country, but also that of our own citizens to any other country.

Congress could effectively close the borders to immigration, and as a matter of policy has strictly regulated the immigration of people from certain countries for centuries — limitations that continue today. It is unlikely that a ban on emigration would be upheld by the courts, however, given the unenumerated right to travel.

· Congress may withhold, as long as they think proper, all information respecting their proceedings from the people.

The Constitution requires that the Congress keep journals and publish them “from time to time.” The definition of “time to time” might have allowed the publication of journals to be delayed for a long time, but today, with the advent of computerized journals and the Internet, “time to time” means no more than 24 hours.

· Congress may order the elections for members of their own body, in the several states, to be held at what times, in what places, and in what manner they shall think proper. Thus, in Pennsylvania, they may order the elections to be held in the middle of winter, at the city of Philadelphia; by which means the inhabitants of nine-tenths of the state will be effectually (tho’ constitutionally) deprived of the exercise of their right of suffrage.

Congress does have the power to alter state plans for time, place, and manner of election, but the Congress does not micro-manage elections in this way, though it has set a national date for elections. It is still possible that the Congress could flex its muscle in this way, though it seems unlikely.

· Congress may, in their courts of judicature, abolish trial by jury in civil cases altogether; and even in criminal cases, trial by a jury of the vicinage is not secured by the constitution. A crime committed at Fort Pitt may be tried by a jury of the citizens of Philadelphia.

These concerns were addressed by the 6th and 7th Amendments.

· Congress may, if they shall think it for the “general welfare,” establish an uniformity in religion throughout the United States. Such establishments have been thought necessary, and have accordingly taken place in almost all the other countries in the world, and will no doubt be thought equally necessary in this.

This concern was addressed by the 1st Amendment .

· Though I believe it is not generally so understood, yet certain it is, that Congress may emit paper money, and even make it a legal tender throughout the United States; and, what is still worse, may, after it shall have depreciated in the hands of the people, call it in by taxes, at any rate of depreciation (compared with gold and silver) which they may think proper. For though no state can emit bills of credit, or pass any law impairing the obligation of contracts, yet the Congress themselves are under no constitutional restraints on these points.

The federal government does, indeed, print paper money. This fiat currency, money which has no intrinsic value in and of itself, is a concern of many even today. However, relying on a gold or silver standard was not a viable economic solution either. While it cannot be said that we have evolved the best possible system of economics and monetary policy, the system in place today does lead to a stable currency and economy.

· The number of representatives which shall compose the principal branch of Congress is so small as to occasion general complaint. Congress, however, have no power to increase the number of representatives, but may reduce it even to one fifth part of the present arrangement.

The concern here is that the number of representatives in the House could not exceed one for every thirty thousand — that there could be one for every hundred thousand, but not one for every ten or twenty thousand. Today, this seems almost quaint, since the rate of representation is now about one for every 650,000. The number of representatives is fixed at 435, but that number can be revised by Congress. Most Americans, however, would find little use for more members of Congress. At the rate of one for every thirty thousand, today we would have over nine thousand representatives in the House.

· On the other hand, no state can call forth its militia even to suppress any insurrection or domestic violence which may take place among its own citizens. This power is, by the constitution, vested in Congress.

The power of a state to quell insurrection within its own borders is not precluded by the Constitution. This power is a concurrent one, one which both the state and federal governments can exercise.

· No state can compel one of its own citizens to pay a debt due to a citizen of a neighboring state. Thus a Jersey-man will be unable to recover the price of a turkey sold in the Philadelphia market, if the purchaser shall be inclined to dispute, without commencing an action in one of the federal courts.

This is true — such an interstate case must be brought and heard in a federal court. By the framers, however, this was seen as a protection, and not a violation of a right. The thought was that the New Jersey courts would be inherently biased against the Pennsylvania purchaser. This has become a bigger issue in the Internet age, as parties in a dispute could be widely separated geographically. A tactic of some large corporations is to sue small companies or individuals in courts they are no capable of attending without great expense, the point being to extract a settlement prior to trial. The ability to sue in state courts across state lines would not solve this problem, however.

· No state can encourage its own manufactures either by prohibiting or even laying a duty on the importation of foreign articles.

This is true — but the reason was an eminently practical one. Without a uniform system for tariff and duty, importers would have had to contend with thirteen different sets of regulations, which is the way things worked under the Articles of Confederation . This was almost universally seen as one of the great defects of the Articles.

· No state can give relief to insolvent debtors, however distressing their situation may be, since Congress will have the exclusive right of establishing uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies throughout the United States; and the particular states are expressly prohibited from passing any law impairing the obligation of contracts.

This was true then and is still true, though states could, if they wished, pass laws that provided funds for debtors to help pay back debt — not that they likely would, but they could. The primacy of contracts and their inviolability by the government, state or federal, is a key feature of the Constitution. Its historical effect on the economy is certainly debatable, but the assurance of both parties to a contract that the government cannot relieve either of its terms has a stabilizing effect, not the opposite.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

US government and civics

Course: us government and civics > unit 1.

- Federalist No. 10 (part 1)

- Federalist No. 10 (part 2)

- Federalist No. 10

Anti-Federalists and Brutus No. 1

- Brutus No. 1

- Government power and individual rights: lesson overview

- Government power and individual rights

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

The Gettysburg College–Gilder Lehrman MA in American History : Apply now and join us for Fall 2024 courses

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

Ratifying the US Constitution: Federalists v. Anti-Federalists and the State Debates, 1787-1788

By tim bailey.

Click here to download this five-lesson unit.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

The Debate Over a Bill of Rights

Antifederalists argued that in a state of nature people were entirely free. In society some rights were yielded for the common good. But, there were some rights so fundamental that to give them up would be contrary to the common good. These rights, which should always be retained by the people, needed to be explicitly stated in a bill of rights that would clearly define the limits of government. A bill of rights would serve as a fire bell for the people, enabling them to immediately know when their rights were threatened.

Additionally, some Antifederalists argued that the protections of a bill of rights was especially important under the Constitution, which was an original compact with the people. State bills of rights offered no protection from oppressive acts of the federal government because the Constitution, treaties and laws made in pursuance of the Constitution were declared to be the supreme law of the land. Antifederalists argued that a bill of rights was necessary because, the supremacy clause in combination with the necessary and proper and general welfare clauses would allow implied powers that could endanger rights.

Federalists rejected the proposition that a bill of rights was needed. They made a clear distinction between the state constitutions and the U.S. Constitution. Using the language of social compact, Federalists asserted that when the people formed their state constitutions, they delegated to the state all rights and powers which were not explicitly reserved to the people. The state governments had broad authority to regulate even personal and private matters. But in the U.S. Constitution, the people or the states retained all rights and powers that were not positively granted to the federal government. In short, everything not given was reserved. The U.S. government only had strictly delegated powers, limited to the general interests of the nation. Consequently, a bill of rights was not necessary and was perhaps a dangerous proposition. It was unnecessary because the new federal government could in no way endanger the freedoms of the press or religion since it was not granted any authority to regulate either. It was dangerous because any listing of rights could potentially be interpreted as exhaustive. Rights omitted could be considered as not retained. Finally, Federalists believed that bills of rights in history had been nothing more than paper protections, useless when they were most needed. In times of crisis they had been and would continue to be overridden. The people’s rights are best secured not by bills of rights, but by auxiliary precautions: the division and separation of powers, bicameralism, and a representative form of government in which officeholders were responsible to the people, derive their power from the people, and would themselves suffer from the loss of basic rights.

(F) Federalist Essays/Speeches (AF) Antifederalist Essays/Speeches

Dangerous to List Rights

- Publius: The Federalist 84, New York, 28 May 1788 (F)

- Edmund Pendleton to Richard Henry Lee, Richmond, Va., 14 June 1788 (F)

Enumerated Powers Protect Rights

- James Wilson Speech in the State House Yard, Philadelphia, 6 October 1787 (F)

- Anti-Cincinnatus, Northampton, Mass., Hampshire Gazette , 19 December 1787 (F)

- Aristides: Remarks on the Proposed Plan of a Federal Government , 31 January 1788 (F)

- George Nicholas Speech: Virginia Convention, 16 June 1788 (F)

- An Old Whig III, Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer , 20 October 1787 (AF)

- Cincinnatus I: To James Wilson, Esquire, New York Journal , 1 November 1787 (AF)

- Federal Farmer: Letters to the Republican , New York, 8 November 1787 —excerpts from Letter IV (12 October 1787) (AF)

- Patrick Henry Speech: Virginia Convention, 12 June 1788 (AF)

Essential in an Original Contract

- An Old Whig IV, Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer , 27 October 1787 (AF)

- John De Witt II, Boston American Herald , 29 October 1787 (AF)

- Brutus II, New York Journal , 1 November 1787 (AF)

- Agrippa XV, Massachusetts Gazette , 29 January 1788 (AF)

- Luther Martin: A Citizen of the State of Maryland, Remarks Relative to a Bill of Rights, 12 April 1788 (AF)

General Arguments

- A Countryman II (De Witt Clinton), New Haven Gazette , 22 November 1787 (F)

- Valerius, Massachusetts Centinel , 28 November 1787 (F)

- A Federal Republican, A Review of the Constitution , Philadelphia, 28 November 1787 (AF)

- Portius, Boston American Herald , 12 November 1787 (AF)

Good Government Protects Rights

- A Native of Virginia: Observations upon the Proposed Plan of Federal Government , 2 April 1788 (F)

- Fabius IV, Pennsylvania Mercury , 19 April 1788 (F)

Ineffective to List Rights

- A Countryman II (Hugh Hughes), New York Journal , 23 November 1787 (F)

- Gazette of the State of Georgia , 20 March 1788 (F)

Jury Trials Need Protection

- Cincinnatus II: To James Wilson, Esquire, New York Journal , 8 November 1787 (AF)

- The Dissent of the Minority of the Convention, Pennsylvania Packet , 18 December 1787 (AF)

Limits Government

- Uncus, Maryland Journal , 9 November 1788 (F)

- Richard Henry Lee to Edmund Randolph, New York, 16 October 1787 (AF)

- Patrick Henry Speech: Virginia Convention, 16 June 1788 (AF)

Limiting Powers More Important than Bill of Rights

- James Wilson Speech: Pennsylvania Convention, 28 November 1787 (F)

Necessary to Check Government Power

- Timoleon, New York Journal , 1 November 1787 (AF)

- Robert Whitehill Speech: Pennsylvania Convention, 28 November 1787 (AF)

- Philadelphiensis III, Philadelphia Freeman’s Journal , 5 December 1787 (AF)

- Address to the Members of the New York and Virginia Conventions, post-30 April 1788 (AF)

Necessary to Prevent Tyranny

- John Smilie Speech: Pennsylvania Convention, 28 November 1787 (AF)

Necessary Statement of First Principles

- A True Friend, Richmond, Va., 6 December 1787 (AF)

- A Delegate Who Has Catched Cold, Virginia Independent Chronicle , 25 June 1788 (AF)

Not Necessary to List Rights

- One of the Middling-Interest, Boston Massachusetts Centinel , 28 November 1787 (F)

- Valerius, Boston Massachusetts Centinel , 28 November 1787 (F)

- America, New York Daily Advertiser , 31 December 1787 (F)

- William Cushing: Undelivered Speech, c. 4 February 1788 (F)

Not Necessary to List Natural Rights

- Remarker, Boston Independent Chronicle , 27 December 1787 (F)

Only Needed in Monarchial Governments

- Marcus I, Norfolk and Portsmouth Journal , 20 February 1788 (F)

- A Citizen of New-York: An Address to the People of the State of New York , New York Packet , 15 April 1788 (F)

- New York Journal , 23 January 1788 (AF)

Partial List in the Constitution is Incomplete

- Federal Farmer: Letters to the Republican , New York, 8 November 1787 —excerpt from Letter IV (12 October 1787) (AF)

- Thomas B. Wait to George Thatcher, Portland, Maine, 8 January 1788 (AF)

- Patrick Henry Speech: Virginia Convention, 17 June 1788 (AF)

Proposed/Recommended Bills of Rights

- Richard Henry Lee’s Proposed Amendments, 27 September 1787

- Robert Whitehill’s Proposed Amendments: Pennsylvania Convention, 12 December 1787

- The Dissent of the Minority of the Convention, Pennsylvania Packet , 18 December 1787

- Massachusetts Form of Ratification, 6–7 February 1788

- William Paca’s Proposed Amendments: Maryland Convention, Maryland Journal , 29 April 1788

- New Hampshire Convention Amendments, 21 June 1788

- George Mason’s Proposed Amendments: Virginia Convention, 27 June 1788

- Recommended Amendments from the Virginia Convention, 27 June 1788

- John R. Lansing’s Proposed Amendments: New York Convention, 10 July 1788

- Melancton Smith’s Proposed Amendments: New York Convention, 17 July 1788

- New York Convention Recommendatory Amendments and Bill of Rights, 25 July 1788

- North Carolina Hillsborough Convention Amendments, 2 August 1788

- Rhode Island Form of Ratification and Amendments, 29 May 1790

Representation Protects Rights

- Letter from Roger Sherman, New Haven, Conn., 8 December 1787 (F)

Supremacy Clause a Threat to Individual Rights

- The Impartial Examiner I, Virginia Independent Chronicle , 20 February 1788 (AF)

- Denatus, Virginia Independent Chronicle , 11 June 1788 (AF)

Treaty Powers a Threat to Individual Rights

- James Madison Speech: Virginia Convention, 19 June 1788 (F)

- Patrick Henry Speech: Virginia Convention, 19 June 1788 (AF)

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Federalist and Anti-federalist Debates on Diversity and the Extended Republic

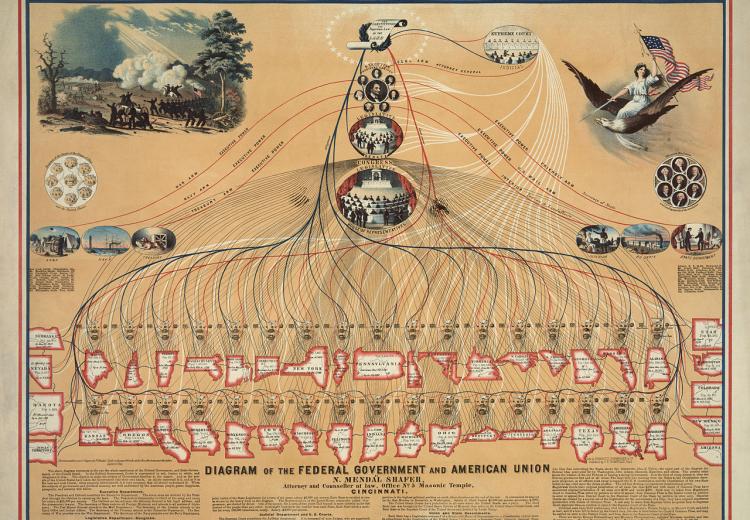

Diagram of the US Federal Government and American Union, 1862.

Wikimedia Commons

In September of 1787, the delegates to the Convention in Philadelphia presented their work to the American public for ratification. The proposed Constitution marked a clear departure from the Articles of Confederation, which had essentially established a federal “league of friendship” between thirteen sovereign and largely independent states. Under the newly proposed plan of government, the union between the states would be strengthened under a national government that derived its authority—at least in part—directly from the American people rather than purely from the state legislatures. And under the new Constitution, the people would be represented equally in the House, regardless of the state in which they lived—unlike the Articles of Confederation, according to which the Continental Congress equally represented the states . In other words, the proposed Constitution would make the United States a nation of one people rather than a loose confederation of states.

In this unit, students will examine the arguments of Anti-federalists and Federalists to learn what their compromises would mean for the extended republic that would result from the new Constitution. They will become familiar with some of the greatest thinkers on both sides of the argument and their reasons for opposing or supporting the Constitution. They will learn why Anti-federalists believed that a large nation could not long preserve liberty and self-government. They will also learn why Federalists such as James Madison believed that a large nation was vital to promote justice and the security of rights for all citizens, majority and minority alike. Finally, students will see the seriousness of the question as one that both sides believed would determine the happiness, liberty, and safety of future generations of Americans.

Guiding Questions

What are the merits of the Anti-federalist argument that an extended republic will lead to the destruction of liberty and self-government?

Was James Madison correct when he claimed that a republican government over an extended territory was necessary to both preserve the Union and secure the rights of citizens?

Learning Objectives

Understand what Anti-federalists meant by the terms “extended republic” or “consolidated republic.”

Articulate the problems the Anti-federalists believed would arise from extending the republic over a vast territory.

Evaluate the nature and purpose of representation and the competing arguments regarding the short and long-term outcomes of these decisions.

Evaluate the argument that a large republic would result in an abuse of power by those holding elected office.

Evaluate the merits of a “pure democracy” and a representative republic.

Construct an argument as to which perspective regarding the size of a government and republic has proved true in the U.S. today.

Curriculum Details

The proposed Constitution, and the change it wrought in the nature of the American Union, spawned one of the greatest political debates of all time. In addition to the state ratifying conventions, the debates also took the form of a public conversation, mostly through newspaper editorials, with Anti-federalists on one side objecting to the Constitution, and Federalists on the other supporting it. Writers from both sides tried to persuade the public that precious liberty and self-government, hard-earned during the late Revolution, were at stake in the question.

Anti-federalists such as the Federal Farmer, Centinel, and Brutus argued that the new Constitution would eventually lead to the dissolution of the state governments, the consolidation of the Union into “one great republic” under an unchecked national government, and as a result the loss of free, self-government. Brutus especially believed that in such an extensive and diverse nation, nothing short of despotism “could bind so great a country under one government.” Federalists such as James Madison (writing as Publius) countered that it was precisely a large nation, in conjunction with a well-constructed system of government, which would help to counter the “mortal disease” of popular governments: the “dangerous vice” of majority faction. In an extended republic, interests would be multiplied, Madison argued, making it difficult for a majority animated by one interest to unite and oppress the minority. If such a faction did form, a frame of government that included “auxiliary precautions” such as separation of powers and legislative checks and balances would help to prevent the “factious spirit” from introducing “instability, injustice, and confusion … into the public councils.”

Review each lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEment-reviewed websites. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing.

- Text Document for Lesson 1, Activity 1

- Text Document for Lesson 1, Activity 2

- Text Document for Lesson 2, Activity 1

- Text Document for Lesson 2, Activity 2

These Text Documents contain excerpted versions of the documents used in the activities, as well as questions for students to answer.

Analyzing primary sources — If students need practice in analyzing primary source documents, excellent resource materials are available at The Learning Page from the Library of Congress and Educator Resources from the National Archives .

Lesson Plans in Curriculum

Lesson 1: anti-federalist arguments against "a complete consolidation".

This lesson focuses on the chief objections of the Anti-federalists, especially The Federal Farmer (Richard Henry Lee), Centinel, and Brutus, regarding the extended republic. Students become familiar with the larger issues surrounding this debate, including the nature of the American Union, the difficulties of uniting such a vast territory with a diverse multitude of regional interests, and the challenges of maintaining a free republic as the American people moved toward becoming a nation rather than a mere confederation of individual states.

Lesson 2: The Federalist Defense of Diversity and "Extending the Sphere"

This lesson involves a detailed analysis of Alexander Hamilton’s and James Madison’s arguments in favor of the extended republic in The Federalist Nos. 9, 10 and 51. Students consider and understand in greater depth the problem of faction in a free republic and the difficulty of establishing a government that has enough power to fulfill its responsibilities, but which will not abuse that power and infringe on liberties of citizens.

Related on EDSITEment

Advanced placement u.s. history lessons, the federalist debates: balancing power between state and federal governments, commemorating constitution day, the constitutional convention of 1787.

Timeline of the Federalist-Antifederalist Debates

Introduction to the Chronology of the Federalist-Antifederalist Debates

The Federalist-Antifederalist Debate is usually conceived of as having taken place after the release of the Constitution in September, 1787, and continuing up to its ratification in 1788. The debate, waged between editorialists – some name and most under pen-names – began before the Constitutional Convention had formally convened, and picked up pace by August, 1787. Most initial essays, printed in newspapers across the states, were from opponents to a new government; however, as time passed and the Federalist authors began producing their work from New York, other Federalist-aligned authors joined the effort, even if there was virtually no coordination between them.

What follows are essays from both those who supported and opposed the new constitution, from across the country, from Spring 1787 through the closing days of 1788, provided alongside one another for context.

- May 16, 1787: Z. (Pennsylvania)

August 1787

- Aug 6, 1787: A Foreign Spectator I (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 9, 1787: Atticus Essay I (Massachusetts)

- Aug 10, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part IV (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 16, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part VI (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 17, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part VII (Pennsylvania)

- Aug 24, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part X (Pennsylvania)

September 1787

- Sept 4, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 12, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XX (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 13, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXI (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 13, 1787: Objections to the Constitution (Virginia)

- Sept 17, 1787: Benjamin Franklin Speech, Federal Convention (Constitutional Convention)

- Sept 17, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXIII (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 18, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXIV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 21, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXV (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 26, 1787: Letter from Sherman and Ellsworth to the Governor of Connecticut (Connecticut)

- Sept 26, 1787: An American Citizen I (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 27, 1787: A Pennsylvania Farmer (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 27, 1787: Cato I (New York)

- Sept 28, 1787: Call for state ratifying conventions by Confederation Congress (Confederation Congress)

- Sept 28, 1787: A Foreign Spectator, Part XXVIII (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 28, 1787: An American Citizen II (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 28, 1787: An American Citizen III (Pennsylvania)

- Sept 29, 1787: Curtius No. I (New York)

October 1787

- Oct 1787: An American Citizen IV (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 1, 1787: Caesar I (New York)

- Oct 1, 1787: Letter from Richard Henry Lee to George Mason (Virginia)

- Oct 2, 1787: Foreign Spectator XXIX (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 5, 1787: Centinel I (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 6, 1787: Crito (Rhode Island)

- Oct 8, 1787: Federal Farmer I (Virginia)

- Oct 9, 1787: Federal Farmer II (Virginia)

- Oct 10, 1787: Federal Farmer III (Virginia)

- Oct 10, 1787: Randolph Letter, On the Federal Constitution (Virginia)

- Oct 11, 1787: Cato II (New York)

- Oct 12, 1787: Federal Farmer IV (Virginia)

- Oct 12, 1787: An Old Whig I (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 13, 1787: Federal Farmer V (Virginia)

- Oct 13, 1787: Convention Essay (Massachusetts)

- Oct 15, 1787: One of Four Thousand (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: Connecticut calls for state convention (Connecticut)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Democratic Federalist (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: Caesar II (New York)

- Oct 17, 1787: An Old Whig II (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Citizen of America by Noah Webster (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 17, 1787: A Citizen of America: An Examination Into the Leading Principles of America (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 18, 1787: Brutus I (New York) ( click here for special commentary on Brutus I )

- Oct 18, 1787: Elbridge Gerry’s Objections (Massachusetts)

- Oct 18, 1787: Atticus Essay II (Massachusetts)

- Oct 20, 1787: An Old Whig III (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 22, 1787: John DeWitt I (Massachusetts)

- Oct 24, 1787: James Madison to Thomas Jefferson (Virginia)

- Oct 24, 1787: Monitor Essay (Massachusetts)

- Oct 24, 1787: Centinel II (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 25, 1787: A Republican No. 1 (New York)

- Oct 25, 1787: Cato III (New York)

- Oct 25, 1787: A Federalist Essay (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 27, 1787: John DeWitt II (Massachusetts)

- Oct 27, 1787: An Old Whig IV (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 27, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 1 (New York)( Click here for special commentary on Federalist 1 )

- Oct 30, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay I (New York)

- Oct 30, 1787: Letter from Gouverneur Morris to George Washington (Pennsylvania)

- Oct 31, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 2 (New York)

November 1787

- Nov 1, 1787: An Old Whig V (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 1, 1787: Brutus II (New York)

- Nov 1, 1788: Cincinnatus No. 1 (New York)

- Nov 2, 1787: Foreigner I (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 3, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 3 (New York)

- Nov 3, 1788: Elbridge Gerry to the Massachusetts General Court (Massachusetts)

- Nov 5, 1787: John DeWitt III (Massachusetts)

- Nov 5, 1787: A Landholder Letter I (Connecticut)

- Nov 6, 1787: An Officer of the Late Continental Army (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 7, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 4 (New York)

- Nov 7, 1787: Philadelphiensis I (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 8, 1787: Centinel III (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 8, 1787: Brutus, Junior (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Cato IV (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Cincinnatus No. 2 (New York)

- Nov 8, 1787: Federal Farmer: Letters to the Republican (Virginia)

- Nov 10, 1787: Massachusetts Centinel (Massachusetts)

- Nov 10, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 5 (New York)

- Nov 14, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 6 (New York)

- Nov 12, 1787: A Landholder Letter II (Connecticut)

- Nov 14, 1787: Socius Essay (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 15, 1787: Brutus III (New York)

- Nov 15, 1787: A Countryman I (Connecticut)

- Nov 15, 1787: Essay by a Georgian (Georgia)

- Nov 16, 1787: Philo-Publius Essay II (New York)

- Nov 17, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 7 (New York)

- Nov 17, 1787: An American: The Crisis (Massachusetts)

- Nov 19, 1787: A Landholder III (Connecticut)

- Nov 19, 1787: A Farmer, of New Jersey: Observations on Government New York (New Jersey)

- Nov 20, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 8 (New York)

- Nov 21, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 9 (New York)

- Nov 21, 1787: George Mason’s Objections (Virginia)

- Nov 22, 1787: Brutus on Mason’s Objections (Virginia)

- Nov 22, 1787: Cato V (New York)

- Nov 22, 1787: A Countryman II (Connecticut)

- Nov 22, 1787: Atticus Essay III (Massachusetts)

- Nov 22, 1787: Cincinnatus No. 4 (New York)

- Nov 22, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 10 (New York)( Click here for special commentary on Federalist 10 )

- Nov 23, 1787: Agrippa I (Massachusetts)

- Nov 24, 1787: Federalist Paper No. 11 (New York)

- Nov 24, 1787: An Old Whig VI (Pennsylvania)

- Nov 24, 1787 – Dec 24, 1787: Timothy Pickering and the Letters from the Federal Farmer (New York)