Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

Home › Study Tips › How To Write an Academic Essay? 9 Amazing Tips

100 Essay Writing Tips for Students (How to write a good essay)

- Published September 7, 2022

Are you searching for the best tips to create the most compelling essay? We’ve compiled some of the best essay writing tips so that you don’t have to search far and wide to learn how to write a good essay. Take a look at these top 100 essay writing tips!

100 Essay Writing Tips

#1 Analyse the question

#2 Define your argument

#3 Use reputable sources of evidence to support your claims (i.e. not Wikipedia)

#4 Share different perspectives

#5 On draft number 1, don’t worry about spelling, punctuation or grammar!

#6 Rewrite draft 2 on a new blank document

#7 Use transitional phrases and words

#8 Divide your essay into three main parts: introduction, main body, conclusion

#9 End your essay on a relevant quote

#10 Check your spelling, punctuation and grammar in your final draft

#11 Cite your sources correctly (check the guidelines or ask your teacher)

#12 Avoid using conjunctions at the start of sentences e.g. And / But / Also

#13 Put direct quotes in quotation marks, citing them correctly

#14 Avoid plagiarism (your teacher or the marker will know if you have copied)

#15 Rephrase your research – put it into your own words

#16 Avoid the repetition of phrases and words

#17 Use a thesaurus to find synonyms for words you have used often

#18 Provide statistics to support your claims

#19 Include facts to support your arguments

#20 Use emotive language where appropriate to write a compelling argument

#21 Avoid spending too much time on your introduction and conclusion

#22 Get somebody else to proofread it

#23 Get feedback from friends and family (or even a teacher)

#24 Don’t be afraid to delete irrelevant points and evidence

#25 Avoid slang and colloquial language

#26 Use formal language throughout your essay

#27 Double space your essay (check essay requirements to ensure you format it correctly)

#28 Use appropriate titles and headings

#29 Use an appropriate font (Times New Roman, size 12 is the most common, acceptable font)

#30 Avoid images unless you have been asked to use them

#31 Avoid talking about yourself or providing anecdotal information

#32 Avoid cliches, try to be original in your writing

#33 Keep your introduction and conclusion short

#34 Stick to the word count (universities usually allow 10% over or under)

#35 Distribute the word count appropriately across your introduction, main body and conclusion (e.g. 10/80/10)

#36 Read it out loud to spot errors

#37 Make sure your writing is clear and concise

#38 Avoid citing sources in your bibliography that are irrelevant

#39 Use grammar checking software to check for grammar errors

#40 Don’t depend solely on grammar checking software (because it’s a computer, it may get context wrong)

#41 Read your work critically – have you answered the question?

#42 Don’t get distracted by what you WANT to write, focus on answering the question

#43 Check the grading criteria and set your goals – if you want an A, what do you need to do to get there?

#44 Create a checklist based on the grading criteria

#45 Create a timetable to write your essay and plan your time wisely

#46 Plan your writing during times when you’re least likely to get disturbed

#47 Work in a place where you are least likely to get distracted

#48 Write your essay in 25-minute increments and take a break after each one

#49 Have snacks and refreshments to hand

#50 Take a break after writing each draft, for example, 2 days where you don’t look at it (this will allow you to process information and go back to your essay with fresh eyes)

#51 Remember that stress doesn’t help – you’re most likely going to write well when you’re the least stressed.

#52 If you’re struggling to write your essay at home, do it in a study group or at the library. You’ll likely be more productive surrounded by other people who are working, too.

#53 Don’t leave it to the last minute – write several drafts in good time

#54 Plan your final week to work on formatting only (do the bulk of the work way before the final week)

#55 Swap work with a friend and give each other feedback, or do this in a group

#56 Make sure you know the submission criteria way before submitting e.g. the format of your essay, rules for submission, etc.

#57 Define the type of essay you’re writing – is it argumentative, persuasive, expository, admissions, compare/contrast, analytical or narrative?

#58 Brainstorm the essay before writing it

#59 Keep your notes handy

#60 Identify the gaps in your knowledge before writing

#61 Before you begin writing, do as much productive research as you can

#62 Read relevant books and reputable articles to learn more about your topic

#63 Write notes in the form of short answers to your question, it will be easier to put them into your essay later on

#64 If you’re finding it difficult to answer the question, more research is needed

#65 Identify your WHY – Why do you need to write this essay? What will happen if you get an A or win the essay competition? Why is it important to you?

#66 When essay writing is becoming a struggle, remember your WHY to keep motivated

#67 In your introduction, remember to clearly state your topic and your main points

#68 Avoid explaining your points in your introduction (you do that in the main body)

#69 For every point or opinion you introduce, be sure to include some evidence and an explanation

#70 Avoid filling your essay up with opinions with no supporting evidence

#71 Explain your points clearly and concisely

#72 Stay on topic

#73 When proofreading, consider if the essay sparks the reader’s interest. If it doesn’t, see what you can do to improve this.

#74 Double check you have used paragraphs correctly

#75 Ensure each argument has a single focus and a clear connection to the thesis statement

#76 Ensure you have clear transitions between your sentences and paragraphs

#77 Ensure your essay has an informative and compelling style

#78 Try using these phrases such as: In view of; in light of; considering

#79 Use one of the following sentence structure when writing about your evidence “According to…” “…. stated that, “Referring to the views of…”

#80 Maintain an unbiased voice in your writing – your goal is to present some intriguing arguments to the reader

#81 Try using phrases such as “In order to…”, “To that end…”, “To this end…”

#82 Use phrases like these to emphasize a point: In other words; to put it another way; that is; to put it more simply

#83 Other phrases you could use are: Similarly; likewise; another key fact to remember; as well as; an equally significant aspect of

#84 When comparing ideas or opinions, use phrases such as: By contrast; in comparison; then again; that said; yet

#85 Use these phrases to demonstrate a positive aspect of something: Despite this; provided that; nonetheless

#86 Another way to add contrast is using these phrases: Importantly; significantly; notably; another key point

#87 When giving examples, try using phrases like these: For instance; to give an illustration of; to exemplify; to demonstrate; as evidence; to elucidate

#88 Try using these phrases in your conclusion: In conclusion; to conclude; to summarise; in sum; in the final analysis; on close analysis

#89 This phrase can be used to highlight the most compelling argument in your research “the most compelling argument is…”

#90 When explaining the significance of something, use one of these phrases: Therefore; this suggests that; it can be seen that; the consequence is

#91 When summarizing, you can use some of these phrases: Above all; chiefly; especially; most significantly; it should be noted

#92 You might want to use the phrase “All things considered” when summarizing towards the end of your essay

#93 Avoid using Wikipedia

#94 Remember that the marker will always check to see if you have copied your work – so don’t do it

#95 Try your best

#96 Remember that writing an essay is also an opportunity to learn

#97 Build your vocabulary while writing by using a dictionary to replace common words

#98 Make sure you understand the definition of the words you have used

#99 Work hard but remember to take breaks

#100 Submit your essay on time!

- Administrator

- July 2, 2024

We will send you updates and the latest news about our company. Sign up for free by filling out the form.

- Name * First Last

- School Country

- School City

- School Name

- School counsellor/advisor

- Educational agent

- I consent to receiving updates from Immerse Education

- Yes. See Privacy Policy

Download Our Prospectus

- I'm a Parent

- I'm a Student

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- School SF ID

- Which subjects interest you? (Optional) Architecture Artificial Intelligence Banking and Finance Biology Biotechnology Business Management Chemistry Coding Computer Science Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Creative Writing Creative Writing and Film Criminology Data Science and Analytics Earth Science Economics Encryption and Cybersecurity Engineering English Literature Entrepreneurship Fashion and Design Female Future Leaders Film Studies Fine Arts Global Society and Sustainability Health and Biotechnology History International Relations Law Marketing and Entertainment Mathematics Medicine Medicine and Health Sciences Nanotechnology Natural Sciences Philosophy Philosophy Politics and Economics Physics Psychology Software Development and AI Software Development and Gaming Veterinary Studies Online Research Programme

Secure priority enrolment for our new summer school location with a small refundable deposit.

" * " indicates required fields

Receive priority enrolment for new summer school locations by registering your interest below.

Our programme consultant will contact you to talk about your options.

- Family Name *

- Phone Number

- Yes. See Privacy Policy.

Subject is unavailable at location

You have selected a subject that is not available at the location that you have previously chosen.

The location filter has been reset, and you are now able to search for all the courses where we offer the subject.

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1964 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 41,397 quotes across 1964 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Writing a great essay

This resource covers key considerations when writing an essay.

While reading a student’s essay, markers will ask themselves questions such as:

- Does this essay directly address the set task?

- Does it present a strong, supported position?

- Does it use relevant sources appropriately?

- Is the expression clear, and the style appropriate?

- Is the essay organised coherently? Is there a clear introduction, body and conclusion?

You can use these questions to reflect on your own writing. Here are six top tips to help you address these criteria.

1. Analyse the question

Student essays are responses to specific questions. As an essay must address the question directly, your first step should be to analyse the question. Make sure you know exactly what is being asked of you.

Generally, essay questions contain three component parts:

- Content terms: Key concepts that are specific to the task

- Limiting terms: The scope that the topic focuses on

- Directive terms: What you need to do in relation to the content, e.g. discuss, analyse, define, compare, evaluate.

Look at the following essay question:

Discuss the importance of light in Gothic architecture.

- Content terms: Gothic architecture

- Limiting terms: the importance of light. If you discussed some other feature of Gothic architecture, for example spires or arches, you would be deviating from what is required. This essay question is limited to a discussion of light. Likewise, it asks you to write about the importance of light – not, for example, to discuss how light enters Gothic churches.

- Directive term: discuss. This term asks you to take a broad approach to the variety of ways in which light may be important for Gothic architecture. You should introduce and consider different ideas and opinions that you have met in academic literature on this topic, citing them appropriately .

For a more complex question, you can highlight the key words and break it down into a series of sub-questions to make sure you answer all parts of the task. Consider the following question (from Arts):

To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?

The key words here are American Revolution and revolution ‘from below’. This is a view that you would need to respond to in this essay. This response must focus on the aims and motivations of working people in the revolution, as stated in the second question.

2. Define your argument

As you plan and prepare to write the essay, you must consider what your argument is going to be. This means taking an informed position or point of view on the topic presented in the question, then defining and presenting a specific argument.

Consider these two argument statements:

The architectural use of light in Gothic cathedrals physically embodied the significance of light in medieval theology.

In the Gothic cathedral of Cologne, light served to accentuate the authority and ritual centrality of the priest.

Statements like these define an essay’s argument. They give coherence by providing an overarching theme and position towards which the entire essay is directed.

3. Use evidence, reasoning and scholarship

To convince your audience of your argument, you must use evidence and reasoning, which involves referring to and evaluating relevant scholarship.

- Evidence provides concrete information to support your claim. It typically consists of specific examples, facts, quotations, statistics and illustrations.

- Reasoning connects the evidence to your argument. Rather than citing evidence like a shopping list, you need to evaluate the evidence and show how it supports your argument.

- Scholarship is used to show how your argument relates to what has been written on the topic (citing specific works). Scholarship can be used as part of your evidence and reasoning to support your argument.

4. Organise a coherent essay

An essay has three basic components - introduction, body and conclusion.

The purpose of an introduction is to introduce your essay. It typically presents information in the following order:

- A general statement about the topic that provides context for your argument

- A thesis statement showing your argument. You can use explicit lead-ins, such as ‘This essay argues that...’

- A ‘road map’ of the essay, telling the reader how it is going to present and develop your argument.

Example introduction

"To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?"

Introduction*

Historians generally concentrate on the twenty-year period between 1763 and 1783 as the period which constitutes the American Revolution [This sentence sets the general context of the period] . However, when considering the involvement of working people, or people from below, in the revolution it is important to make a distinction between the pre-revolutionary period 1763-1774 and the revolutionary period 1774-1788, marked by the establishment of the continental Congress(1) [This sentence defines the key term from below and gives more context to the argument that follows] . This paper will argue that the nature and aims of the actions of working people are difficult to assess as it changed according to each phase [This is the thesis statement] . The pre-revolutionary period was characterised by opposition to Britain’s authority. During this period the aims and actions of the working people were more conservative as they responded to grievances related to taxes and scarce land, issues which directly affected them. However, examination of activities such as the organisation of crowd action and town meetings, pamphlet writing, formal communications to Britain of American grievances and physical action in the streets, demonstrates that their aims and actions became more revolutionary after 1775 [These sentences give the ‘road map’ or overview of the content of the essay] .

The body of the essay develops and elaborates your argument. It does this by presenting a reasoned case supported by evidence from relevant scholarship. Its shape corresponds to the overview that you provided in your introduction.

The body of your essay should be written in paragraphs. Each body paragraph should develop one main idea that supports your argument. To learn how to structure a paragraph, look at the page developing clarity and focus in academic writing .

Your conclusion should not offer any new material. Your evidence and argumentation should have been made clear to the reader in the body of the essay.

Use the conclusion to briefly restate the main argumentative position and provide a short summary of the themes discussed. In addition, also consider telling your reader:

- What the significance of your findings, or the implications of your conclusion, might be

- Whether there are other factors which need to be looked at, but which were outside the scope of the essay

- How your topic links to the wider context (‘bigger picture’) in your discipline.

Do not simply repeat yourself in this section. A conclusion which merely summarises is repetitive and reduces the impact of your paper.

Example conclusion

Conclusion*.

Although, to a large extent, the working class were mainly those in the forefront of crowd action and they also led the revolts against wealthy plantation farmers, the American Revolution was not a class struggle [This is a statement of the concluding position of the essay]. Working people participated because the issues directly affected them – the threat posed by powerful landowners and the tyranny Britain represented. Whereas the aims and actions of the working classes were more concerned with resistance to British rule during the pre-revolutionary period, they became more revolutionary in nature after 1775 when the tension with Britain escalated [These sentences restate the key argument]. With this shift, a change in ideas occurred. In terms of considering the Revolution as a whole range of activities such as organising riots, communicating to Britain, attendance at town hall meetings and pamphlet writing, a difficulty emerges in that all classes were involved. Therefore, it is impossible to assess the extent to which a single group such as working people contributed to the American Revolution [These sentences give final thoughts on the topic].

5. Write clearly

An essay that makes good, evidence-supported points will only receive a high grade if it is written clearly. Clarity is produced through careful revision and editing, which can turn a good essay into an excellent one.

When you edit your essay, try to view it with fresh eyes – almost as if someone else had written it.

Ask yourself the following questions:

Overall structure

- Have you clearly stated your argument in your introduction?

- Does the actual structure correspond to the ‘road map’ set out in your introduction?

- Have you clearly indicated how your main points support your argument?

- Have you clearly signposted the transitions between each of your main points for your reader?

- Does each paragraph introduce one main idea?

- Does every sentence in the paragraph support that main idea?

- Does each paragraph display relevant evidence and reasoning?

- Does each paragraph logically follow on from the one before it?

- Is each sentence grammatically complete?

- Is the spelling correct?

- Is the link between sentences clear to your readers?

- Have you avoided redundancy and repetition?

See more about editing on our editing your writing page.

6. Cite sources and evidence

Finally, check your citations to make sure that they are accurate and complete. Some faculties require you to use a specific citation style (e.g. APA) while others may allow you to choose a preferred one. Whatever style you use, you must follow its guidelines correctly and consistently. You can use Recite, the University of Melbourne style guide, to check your citations.

Further resources

- Germov, J. (2011). Get great marks for your essays, reports and presentations (3rd ed.). NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Using English for Academic Purposes: A guide for students in Higher Education [online]. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.uefap.com

- Williams, J.M. & Colomb, G. G. (2010) Style: Lessons in clarity and grace. 10th ed. New York: Longman.

* Example introduction and conclusion adapted from a student paper.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

Sample Essays

The breadth of Georgetown’s core curriculum means that students are required to write for a wide variety of academic disciplines. Below, we provide some student samples that exhibit the key features the most popular genres. When reading through these essays, we recommend paying attention to their

1. Structure (How many paragraphs are there? Does the author use headers?)

2. Argument (Is the author pointing out a problem, and/or proposing a solution?)

3. Content (Does the argument principally rely on facts, theory, or logic?) and

4. Style (Does the writer use first person? What is the relationship with the audience?)

Philosophy Paper

- Singer on the Moral Status of Animals

Theology Paper

- Problem of God

- Jewish Civilization

- Sacred Space and Time

- Phenolphthalein in Alkaline Solution

History Paper

- World History

Literature Review

Comparative Analysis

Policy Brief

- Vaccine Manufacturing

White Paper

Critical Analysis

- Ignatius Seminar

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

Getting College Essay Help: Important Do's and Don’ts

College Essays

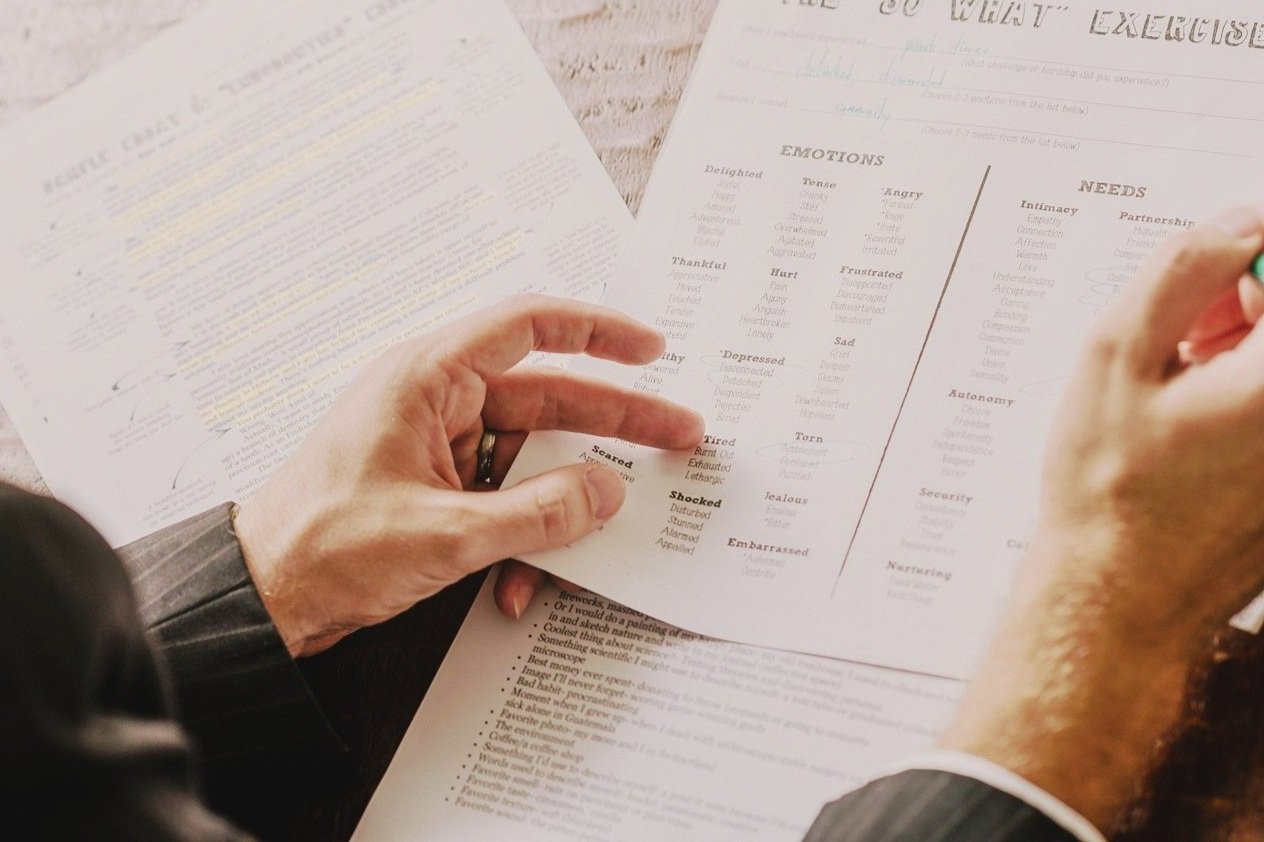

If you grow up to be a professional writer, everything you write will first go through an editor before being published. This is because the process of writing is really a process of re-writing —of rethinking and reexamining your work, usually with the help of someone else. So what does this mean for your student writing? And in particular, what does it mean for very important, but nonprofessional writing like your college essay? Should you ask your parents to look at your essay? Pay for an essay service?

If you are wondering what kind of help you can, and should, get with your personal statement, you've come to the right place! In this article, I'll talk about what kind of writing help is useful, ethical, and even expected for your college admission essay . I'll also point out who would make a good editor, what the differences between editing and proofreading are, what to expect from a good editor, and how to spot and stay away from a bad one.

Table of Contents

What Kind of Help for Your Essay Can You Get?

What's Good Editing?

What should an editor do for you, what kind of editing should you avoid, proofreading, what's good proofreading, what kind of proofreading should you avoid.

What Do Colleges Think Of You Getting Help With Your Essay?

Who Can/Should Help You?

Advice for editors.

Should You Pay Money For Essay Editing?

The Bottom Line

What's next, what kind of help with your essay can you get.

Rather than talking in general terms about "help," let's first clarify the two different ways that someone else can improve your writing . There is editing, which is the more intensive kind of assistance that you can use throughout the whole process. And then there's proofreading, which is the last step of really polishing your final product.

Let me go into some more detail about editing and proofreading, and then explain how good editors and proofreaders can help you."

Editing is helping the author (in this case, you) go from a rough draft to a finished work . Editing is the process of asking questions about what you're saying, how you're saying it, and how you're organizing your ideas. But not all editing is good editing . In fact, it's very easy for an editor to cross the line from supportive to overbearing and over-involved.

Ability to clarify assignments. A good editor is usually a good writer, and certainly has to be a good reader. For example, in this case, a good editor should make sure you understand the actual essay prompt you're supposed to be answering.

Open-endedness. Good editing is all about asking questions about your ideas and work, but without providing answers. It's about letting you stick to your story and message, and doesn't alter your point of view.

Think of an editor as a great travel guide. It can show you the many different places your trip could take you. It should explain any parts of the trip that could derail your trip or confuse the traveler. But it never dictates your path, never forces you to go somewhere you don't want to go, and never ignores your interests so that the trip no longer seems like it's your own. So what should good editors do?

Help Brainstorm Topics

Sometimes it's easier to bounce thoughts off of someone else. This doesn't mean that your editor gets to come up with ideas, but they can certainly respond to the various topic options you've come up with. This way, you're less likely to write about the most boring of your ideas, or to write about something that isn't actually important to you.

If you're wondering how to come up with options for your editor to consider, check out our guide to brainstorming topics for your college essay .

Help Revise Your Drafts

Here, your editor can't upset the delicate balance of not intervening too much or too little. It's tricky, but a great way to think about it is to remember: editing is about asking questions, not giving answers .

Revision questions should point out:

- Places where more detail or more description would help the reader connect with your essay

- Places where structure and logic don't flow, losing the reader's attention

- Places where there aren't transitions between paragraphs, confusing the reader

- Moments where your narrative or the arguments you're making are unclear

But pointing to potential problems is not the same as actually rewriting—editors let authors fix the problems themselves.

Bad editing is usually very heavy-handed editing. Instead of helping you find your best voice and ideas, a bad editor changes your writing into their own vision.

You may be dealing with a bad editor if they:

- Add material (examples, descriptions) that doesn't come from you

- Use a thesaurus to make your college essay sound "more mature"

- Add meaning or insight to the essay that doesn't come from you

- Tell you what to say and how to say it

- Write sentences, phrases, and paragraphs for you

- Change your voice in the essay so it no longer sounds like it was written by a teenager

Colleges can tell the difference between a 17-year-old's writing and a 50-year-old's writing. Not only that, they have access to your SAT or ACT Writing section, so they can compare your essay to something else you wrote. Writing that's a little more polished is great and expected. But a totally different voice and style will raise questions.

Where's the Line Between Helpful Editing and Unethical Over-Editing?

Sometimes it's hard to tell whether your college essay editor is doing the right thing. Here are some guidelines for staying on the ethical side of the line.

- An editor should say that the opening paragraph is kind of boring, and explain what exactly is making it drag. But it's overstepping for an editor to tell you exactly how to change it.

- An editor should point out where your prose is unclear or vague. But it's completely inappropriate for the editor to rewrite that section of your essay.

- An editor should let you know that a section is light on detail or description. But giving you similes and metaphors to beef up that description is a no-go.

Proofreading (also called copy-editing) is checking for errors in the last draft of a written work. It happens at the end of the process and is meant as the final polishing touch. Proofreading is meticulous and detail-oriented, focusing on small corrections. It sands off all the surface rough spots that could alienate the reader.

Because proofreading is usually concerned with making fixes on the word or sentence level, this is the only process where someone else can actually add to or take away things from your essay . This is because what they are adding or taking away tends to be one or two misplaced letters.

Laser focus. Proofreading is all about the tiny details, so the ability to really concentrate on finding small slip-ups is a must.

Excellent grammar and spelling skills. Proofreaders need to dot every "i" and cross every "t." Good proofreaders should correct spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and grammar. They should put foreign words in italics and surround quotations with quotation marks. They should check that you used the correct college's name, and that you adhered to any formatting requirements (name and date at the top of the page, uniform font and size, uniform spacing).

Limited interference. A proofreader needs to make sure that you followed any word limits. But if cuts need to be made to shorten the essay, that's your job and not the proofreader's.

A bad proofreader either tries to turn into an editor, or just lacks the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job.

Some signs that you're working with a bad proofreader are:

- If they suggest making major changes to the final draft of your essay. Proofreading happens when editing is already finished.

- If they aren't particularly good at spelling, or don't know grammar, or aren't detail-oriented enough to find someone else's small mistakes.

- If they start swapping out your words for fancier-sounding synonyms, or changing the voice and sound of your essay in other ways. A proofreader is there to check for errors, not to take the 17-year-old out of your writing.

What Do Colleges Think of Your Getting Help With Your Essay?

Admissions officers agree: light editing and proofreading are good—even required ! But they also want to make sure you're the one doing the work on your essay. They want essays with stories, voice, and themes that come from you. They want to see work that reflects your actual writing ability, and that focuses on what you find important.

On the Importance of Editing

Get feedback. Have a fresh pair of eyes give you some feedback. Don't allow someone else to rewrite your essay, but do take advantage of others' edits and opinions when they seem helpful. ( Bates College )

Read your essay aloud to someone. Reading the essay out loud offers a chance to hear how your essay sounds outside your head. This exercise reveals flaws in the essay's flow, highlights grammatical errors and helps you ensure that you are communicating the exact message you intended. ( Dickinson College )

On the Value of Proofreading

Share your essays with at least one or two people who know you well—such as a parent, teacher, counselor, or friend—and ask for feedback. Remember that you ultimately have control over your essays, and your essays should retain your own voice, but others may be able to catch mistakes that you missed and help suggest areas to cut if you are over the word limit. ( Yale University )

Proofread and then ask someone else to proofread for you. Although we want substance, we also want to be able to see that you can write a paper for our professors and avoid careless mistakes that would drive them crazy. ( Oberlin College )

On Watching Out for Too Much Outside Influence

Limit the number of people who review your essay. Too much input usually means your voice is lost in the writing style. ( Carleton College )

Ask for input (but not too much). Your parents, friends, guidance counselors, coaches, and teachers are great people to bounce ideas off of for your essay. They know how unique and spectacular you are, and they can help you decide how to articulate it. Keep in mind, however, that a 45-year-old lawyer writes quite differently from an 18-year-old student, so if your dad ends up writing the bulk of your essay, we're probably going to notice. ( Vanderbilt University )

Now let's talk about some potential people to approach for your college essay editing and proofreading needs. It's best to start close to home and slowly expand outward. Not only are your family and friends more invested in your success than strangers, but they also have a better handle on your interests and personality. This knowledge is key for judging whether your essay is expressing your true self.

Parents or Close Relatives

Your family may be full of potentially excellent editors! Parents are deeply committed to your well-being, and family members know you and your life well enough to offer details or incidents that can be included in your essay. On the other hand, the rewriting process necessarily involves criticism, which is sometimes hard to hear from someone very close to you.

A parent or close family member is a great choice for an editor if you can answer "yes" to the following questions. Is your parent or close relative a good writer or reader? Do you have a relationship where editing your essay won't create conflict? Are you able to constructively listen to criticism and suggestion from the parent?

One suggestion for defusing face-to-face discussions is to try working on the essay over email. Send your parent a draft, have them write you back some comments, and then you can pick which of their suggestions you want to use and which to discard.

Teachers or Tutors

A humanities teacher that you have a good relationship with is a great choice. I am purposefully saying humanities, and not just English, because teachers of Philosophy, History, Anthropology, and any other classes where you do a lot of writing, are all used to reviewing student work.

Moreover, any teacher or tutor that has been working with you for some time, knows you very well and can vet the essay to make sure it "sounds like you."

If your teacher or tutor has some experience with what college essays are supposed to be like, ask them to be your editor. If not, then ask whether they have time to proofread your final draft.

Guidance or College Counselor at Your School

The best thing about asking your counselor to edit your work is that this is their job. This means that they have a very good sense of what colleges are looking for in an application essay.

At the same time, school counselors tend to have relationships with admissions officers in many colleges, which again gives them insight into what works and which college is focused on what aspect of the application.

Unfortunately, in many schools the guidance counselor tends to be way overextended. If your ratio is 300 students to 1 college counselor, you're unlikely to get that person's undivided attention and focus. It is still useful to ask them for general advice about your potential topics, but don't expect them to be able to stay with your essay from first draft to final version.

Friends, Siblings, or Classmates

Although they most likely don't have much experience with what colleges are hoping to see, your peers are excellent sources for checking that your essay is you .

Friends and siblings are perfect for the read-aloud edit. Read your essay to them so they can listen for words and phrases that are stilted, pompous, or phrases that just don't sound like you.