About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

How does education affect poverty?

For starters, it can help end it.

Aug 10, 2023

Access to high-quality primary education and supporting child well-being is a globally-recognized solution to the cycle of poverty. This is, in part, because it also addresses many of the other issues that keep communities vulnerable.

Education is often referred to as the great equalizer: It can open the door to jobs, resources, and skills that help a person not only survive, but thrive. In fact, according to UNESCO, if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills (nothing else), an estimated 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. If all adults completed secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

At its core, a quality education supports a child’s developing social, emotional, cognitive, and communication skills. Children who attend school also gain knowledge and skills, often at a higher level than those who aren’t in the classroom. They can then use these skills to earn higher incomes and build successful lives.

Here’s more on seven of the key ways that education affects poverty.

Go to the head of the class

Get more information on Concern's education programs — and the other ways we're ending poverty — delivered to your inbox.

1. Education is linked to economic growth

Education is the best way out of poverty in part because it is strongly linked to economic growth. A 2021 study co-published by Stanford University and Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University shows us that, between 1960 and 2000, 75% of the growth in gross domestic product around the world was linked to increased math and science skills.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] rowth rate is extraordinarily strong,” the study’s authors conclude. This is just one of the most recent studies linking education and economic growth that have been published since 1990.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] growth rate is extraordinarily strong.” — Education and Economic Growth (2021 study by Stanford University and the University of Munich)

2. Universal education can fight inequality

A 2019 Oxfam report says it best: “Good-quality education can be liberating for individuals, and it can act as a leveler and equalizer within society.”

Poverty thrives in part on inequality. All types of systemic barriers (including physical ability, religion, race, and caste) serve as compound interest against a marginalization that already accrues most for those living in extreme poverty. Education is a basic human right for all, and — when tailored to the unique needs of marginalized communities — can be used as a lever against some of the systemic barriers that keep certain groups of people furthest behind.

For example, one of the biggest inequalities that fuels the cycle of poverty is gender. When gender inequality in the classroom is addressed, this has a ripple effect on the way women are treated in their communities. We saw this at work in Afghanistan , where Concern developed a Community-Based Education program that allowed students in rural areas to attend classes closer to home, which is especially helpful for girls.

Four ways that girls’ education can change the world

Gender discrimination is one of the many barriers to education around the world. That’s a situation we need to change.

3. Education is linked to lower maternal and infant mortality rates

Speaking of women, education also means healthier mothers and children. Examining 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, researchers from the World Bank and International Center for Research on Women found that educated women tend to have fewer children and have them later in life. This generally leads to better outcomes for both the mother and her kids, with safer pregnancies and healthier newborns.

A 2017 report shows that the country’s maternal mortality rate had declined by more than 70% in the last 25 years, approximately the same amount of time that an amendment to compulsory schooling laws took place in 1993. Ensuring that girls had more education reduced the likelihood of maternal health complications, in some cases by as much as 29%.

4. Education also lowers stunting rates

Children also benefit from more educated mothers. Several reports have linked education to lowered stunting , one of the side effects of malnutrition. Preventing stunting in childhood can limit the risks of many developmental issues for children whose height — and potential — are cut short by not having enough nutrients in their first few years.

In Bangladesh , one study showed a 50.7% prevalence for stunting among families. However, greater maternal education rates led to a 4.6% decrease in the odds of stunting; greater paternal education reduced those rates by 2.9%-5.4%. A similar study in Nairobi, Kenya confirmed this relationship: Children born to mothers with some secondary education are 29% less likely to be stunted.

What is stunting?

Stunting is a form of impaired growth and development due to malnutrition that threatens almost 25% of children around the world.

5. Education reduces vulnerability to HIV and AIDS…

In 2008, researchers from Harvard University, Imperial College London, and the World Bank wrote : “There is a growing body of evidence that keeping girls in school reduces their risk of contracting HIV. The relationship between educational attainment and HIV has changed over time, with educational attainment now more likely to be associated with a lower risk of HIV infection than earlier in the epidemic.”

Since then, that correlation has only grown stronger. The right programs in schools not only reduce the likelihood of young people contracting HIV or AIDS, but also reduce the stigmas held against people living with HIV and AIDS.

6. …and vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change

As the number of extreme weather events increases due to climate change, education plays a critical role in reducing vulnerability and risk to these events. A 2014 issue of the journal Ecology and Society states: “It is found that highly educated individuals are better aware of the earthquake risk … and are more likely to undertake disaster preparedness.… High risk awareness associated with education thus could contribute to vulnerability reduction behaviors.”

The authors of the article went on to add that educated people living through a natural disaster often have more of a financial safety net to offset losses, access to more sources of information to prepare for a disaster, and have a wider social network for mutual support.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to education — and growing

Last August, UNICEF reported that half of the world’s 2.2 billion children are at “extremely high risk” for climate change, including its impact on education. Here’s why.

7. Education reduces violence at home and in communities

The same World Bank and ICRW report that showed the connection between education and maternal health also reveals that each additional year of secondary education reduced the chances of child marriage — defined as being married before the age of 18. Because educated women tend to marry later and have fewer children later in life, they’re also less likely to suffer gender-based violence , especially from their intimate partner.

Girls who receive a full education are also more likely to understand the harmful aspects of traditional practices like FGM , as well as their rights and how to stand up for them, at home and within their community.

Fighting FGM in Kenya: A daughter's bravery and a mother's love

Marsabit is one of those areas of northern Kenya where FGM has been the rule rather than the exception. But 12-year-old student Boti Ali had other plans.

Education for all: Concern’s approach

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. Last year, our work to promote education for all reached over 676,000 children. Over half of those students were female.

We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Concern has brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers.

More on how education affects poverty

6 Benefits of literacy in the fight against poverty

Child marriage and education: The blackboard wins over the bridal altar

Project Profile

Right to Learn

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

- Get involved

The transformative power of education in the fight against poverty

October 16, 2023.

Zubair Junjunia, a Generation17 young leader and the Founder of ZNotes, presents at EdTechX.

Zubair Junjunia

Generation17 Young Leader and founder of ZNotes

Time and again, research has proven the incredible power of education to break poverty cycles and economically empower individuals from the most marginalized communities with dignified work and upward social mobility.

Research at UNESCO has shown that world poverty would be more than halved if all adults completed secondary school. And if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills, almost 171 million people could escape extreme poverty.

With such irrefutable evidence, how do we continue to see education underfunded globally? Funding for education as a share of national income has not changed significantly over the last decade for any developing country. And to exacerbate that, the COVID-19 shock pushed the level of learning poverty to an estimated 70 percent .

I have devoted the past decade of my life to fighting educational inequality, a journey that began during my school years. This commitment led to the creation of ZNotes , an educational platform developed for students, by students. ZNotes was born out of the problem I witnessed first-hand; the inequities in end-of-school examination, which significantly influence access to higher education and career opportunities. It is designed as a platform where students can share their notes and access top-quality educational materials without any limitations. ZNotes fosters collaborative learning through student-created content within a global community and levels the academic playing field with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach to content creation and peer learning.

Although I started ZNotes as a solo project, today, it has touched the lives of over 4.5 million students worldwide, receiving an impressive 32 million hits from students across more than 190 countries, especially serving students from emerging economies. We’re proud to say that today, more than 90 percent of students find ZNotes resources useful and feel more confident entering exams , regardless of their socio-economic background. These globally recognized qualifications empower our learners to access tertiary education and enter the world of work.

Sixteen-year-old Zubair set up a blog to share the resources he created for his IGCSE exams. Through word of mouth, his revision notes were discovered by students all over the world and ZNotes was born.

In rapidly changing job market, young people must cultivate resilience and adaptability. World Economic Forum highlights the importance of future skills, encompassing technical, cognitive, and interpersonal abilities. Unfortunately, many educational systems, especially in under-resourced regions, fall short in equipping youth with these vital skills.

To address this challenge, I see innovative technology as a crucial tool both within and beyond traditional school systems. As the digital divide narrows and access to devices and internet connectivity becomes more affordable, delivering quality education and personalized support is increasingly achievable through technology. At ZNotes, we are reshaping the role of students, transforming them from passive consumers to active creators and proponents of education. Empowering youth through a community-driven approach, students engage in peer learning and generate quality resources on an online platform.

Participation in a global learning community enhances young people's communication and collaboration skills. ZNotes fosters a sense of global citizenship, enabling learners to communicate with a diverse range of individuals across race, gender, and religion. Such spaces also result in redistributing social capital as students share advice for future university, internship and career pathways.

“Studying for 14 IGCSE subjects wasn't easy, but ZNotes helped me provide excellent and relevant revision material for all of them. I ended up with 7 A* 7 A, and ZNotes played a huge role. I am off to Cornell University this fall now. A big thank you to the ZNotes team!"

Alongside ensuring our beneficiaries are equipped with the resources and support they need to be at a level playing field for such high stakes exams, we also consider the skills that will set them up for success in life beyond academics. Especially for the hundreds of young people who join our internship and contribution programs , they become part of a global social impact startup and develop both academic skills and also employability skills. After engaging with our internship programs, 77% of interns reported improved candidacy for new jobs and internships.

ZNotes addresses the uneven playing field of standardized testing with a student-empowered and technology-enabled approach for content creation and peer learning.

A few years ago, Jess joined our team as a Social Impact Analyst intern having just completed her university degree while she continued to search for a full-time role. She was able to apply her data analytics skills from a theoretical degree into a real-world scenario and was empowered to play an instrumental role in understanding and developing a Theory of Change model for ZNotes. In just 6 months, she had been able to develop the skills and gain experiences that strengthened her profile. At the end of internship, she was offered a full-time role at a major news and media agency that she is continuing to grow in!

Jess’s example applies to almost every one of our interns . As another one of them, Alexa, said “ZNotes offers the rare and wonderful opportunity to be at the center of meaningful change”.

Being part of an organization making a significant impact is profoundly inspiring and empowering for young people, and assuming high-responsibility roles within such organizations accelerates their skills development and sets them apart in the eyes of prospective employers.

On the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, it is a critical moment to reflect and enact on the opportunity that we have to achieving two key SDGs, Goal 1 and 4, by effectively funding and enabling access to quality education globally.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Thanks for signing up as a global citizen. In order to create your account we need you to provide your email address. You can check out our Privacy Policy to see how we safeguard and use the information you provide us with. If your Facebook account does not have an attached e-mail address, you'll need to add that before you can sign up.

This account has been deactivated.

Please contact us at [email protected] if you would like to re-activate your account.

Lack of access to education is a major predictor of passing poverty from one generation to the next, and receiving an education is one of the top ways to achieve financial stability.

In other words: education and poverty are directly linked.

Increasing access to education can equalize communities, improve the overall health and longevity of a society , and help save the planet .

The problem is that about 258 million children and youth are out of school around the world, according to UNESCO data released in 2018.

Children do not attend school for many reasons — but they all stem from poverty.

Here are all the statistics, facts, and answers to questions you might have that shed light on the connection between poverty and education.

How does poverty affect education?

Families living in poverty often have to choose between sending their child to school or providing other basic needs. Even if families do not have to pay tuition fees, school comes with the added costs of uniforms, books, supplies, and/or exam fees.

Countries across sub-Saharan Africa, where the world’s poorest children live, have made a concerted effort to abolish school fees . While the ratio of students completing lower secondary school increased in the region from 23% in 1990 to 42% in 2014, enrollment is low compared to the 75% global ratio. School remains too expensive for the poorest families. Some children are forced to stay at home doing chores or need to work. In other places, especially in crisis and conflict areas with destroyed infrastructure and limited resources, unaffordable private schools are sometimes the only option .

Why does poverty stop girls from going to school?

Poverty is the most important factor that determines whether or not a girl can access education, according to the World Bank. If families cannot afford the costs of school, they are more likely to send boys than girls. Around 15 million girls will never get the chance to attend school, compared to 10 million boys.

Read More: These Are the Top 10 Best and Worst Countries for Education in 2016

Gender inequality is more prevalent in low-income countries. Women often perform more unpaid work, have fewer assets, are exposed to gender-based violence, and are more likely to be forced into early marriage, all limiting their ability to fully participate in society and benefit from economic growth.

When girls face barriers to education early on, it is difficult for them to recover. Child marriage is one of the most common reasons a girl might stop going to school. More than 650 million women globally have already married under the age of 18. For families experiencing financial hardship, child marriage reduces their economic burden , but it ends up being more difficult for girls to gain financial independence if they are unable to access a quality education.

Lack of access to adequate menstrual hygiene management also stops many girls from attending school. Some girls cannot afford to buy sanitary products or they do not have access to clean water and sanitation to clean themselves and prevent disease. If safety is a concern due to lack of separate bathrooms, girls will stay home from school to avoid putting themselves at risk of sexual assault or harassment.

Read More: 10 Barriers to Education Around the World

An educated girl is not only likely to increase her personal earning potential but can help reduce poverty in her community, too.

“Educated girls have fewer, healthier, and better-educated children,” according to the Global Partnership for Education.

When countries invest in girls’ education, it sees an increase in female leaders, lower levels of population growth, and a reduction of contributions to climate change.

Can education help break the cycle of poverty?

Education promotes economic growth because it provides skills that increase employment opportunities and income. Nearly 60 million people could escape poverty if all adults had just two more years of schooling, and 420 million people could be lifted out of poverty if all adults completed secondary education, according to UNESCO.

Education increases earnings by roughly 10% per each additional year of schooling. For each $1 invested in an additional year of schooling, earnings increase by $5 in low-income countries and $2.5 in lower-middle income countries.

Read More: 264 Million Children Are Denied Access To Education, New Report Says

Education reduces many issues that stop people from living healthy lives, including infant and maternal deaths, stunting, infant and maternal deaths, vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, and violence.

How can we end extreme poverty through education?

There are more children enrolled in school than ever before — developing countries reached a 91% enrollment rate in 2015 — but we must fully close the gap.

World leaders gathered at the United Nations headquarters to address the disparity in 2015 and set 17 Global Goals to end extreme poverty by 2030. Global Goal 4: Quality Education aims to "end poverty in all its forms everywhere."

Read More: How We Can Be the Generation to End Extreme Poverty

The first step to achieving quality education for all is acknowledging that it is a vital part of sustainable development. Citizens, governments, corporations, and philanthropists all have an important role to play. Learn how to ensure global access to education to end poverty by taking action here .

Global Citizen Explains

Defeat Poverty

Understanding How Poverty is the Main Barrier to Education

Feb. 7, 2020

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Every child has the right to learn..

- Available in:

Overview | What we do | Reports | Data | News

A child’s right to education entails the right to learn. Yet, for too many children across the globe, schooling does not lead to learning.

Over 600 million children worldwide are unable to attain minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics, even though two thirds of them are in school. For out-of-school children, foundational skills in literacy and numeracy are further from grasp.

Children are deprived of education for various reasons. Poverty remains one of the most obstinate barriers. Children living through economic fragility, political instability, conflict or natural disaster are more likely to be cut off from schooling – as are those with disabilities, or from ethnic minorities. In some countries, education opportunities for girls remain severely limited.

Even in schools, a lack of trained teachers, inadequate education materials and poor infrastructure make learning difficult for many students. Others come to class too hungry, ill or exhausted from work or household tasks to benefit from their lessons.

Compounding these inequities is a digital divide of growing concern: Most of the world’s school-aged children do not have internet connection in their homes, restricting their opportunities to further their learning and skills development.

Without quality education, children face considerable barriers to employment later in life. They are more likely to suffer adverse health outcomes and less likely to participate in decisions that affect them – threatening their ability to shape a better future for themselves and their societies.

Education is a basic human right. In 147 countries around the world, UNICEF works to provide quality learning opportunities that prepare children and adolescents with the knowledge and skills they need to thrive. We focus on:

Equitable access : Access to quality education and skills development must be equitable and inclusive for all children and adolescents, regardless of who they are or where they live. We make targeted efforts to reach children who are excluded from education and learning on the basis of gender, disability, poverty, ethnicity and language.

Quality learning : Outcomes must be at the centre of our work to close the gap between what students are learning and what they need to thrive in their communities and future jobs. Quality learning requires a safe, friendly environment, qualified and motivated teachers, and instruction in languages students can understand. It also requires that education outcomes be monitored and feed back into instruction.

Education in emergencies : Children living through conflict, natural disaster and displacement are in urgent need of educational support. Crises not only halt children’s learning but also roll back their gains. In many emergencies, UNICEF is the largest provider of educational support throughout humanitarian response, working with UNHCR, WFP and other partners.

Our programmes

Our strategy

Get involved

Help us tackle the learning crisis.

Global Annual Results Report 2023: Humanitarian action

Progress, results achieved and lessons from 2023 in UNICEF humanitarian action

Global Report on Early Childhood Care and Education

The right to a strong foundation

Building Strong Foundations

Brighter futures through education for health and well-being

Skills for a green transition

Solutions for youth on the move

Data and insights

Our research

Our insights

Ahead of Day of the African Child UNICEF says African governments not spending what they need to secure quality education for continent’s children

1,000 days of education – equivalent to three billion learning hours – lost for Afghan girls

Ukraine’s recovery is dependent on the recovery of children’s education

Children call for access to quality climate education

On Earth Day, UNICEF urges governments to empower every child with learning opportunities to be a champion for the planet

- Ending poverty

- Facts about poverty

- Education & poverty

Global poverty and education

Facts & stats about world poverty and education.

- Global poverty facts

- Health & poverty

- Empowerment & poverty

- Employment & poverty

- Giving & poverty

- Technology & poverty

- Hunger & poverty

- Poverty in the U.S.

- Poverty in Africa

The research is conclusive: When we reduce barriers to education, we set children up to thrive. It’s not only about knowledge and numbers, access to education reduces a child’s involvement in gangs and drugs, and lowers the amount of teen pregnancies. Education leads to healthier childhoods and, ultimately, to greater economic prospects as adults. Your sponsorship or gift helps provide children access to life-changing education programs in the communities we serve, as well as crucial health and dental services, life-skills and career-placement workshops, and more.

Sponsor a child Make a gift Learn about our Education Programs

Children who participate in early childhood development achieve higher education levels and make more money as adults.

In developing nations, 60% of 10 ten-year-olds suffer from learning poverty, unable to read/understand simple stories.

For every year a girl remains in school, her average lifetime income increases 10% and odds of an early marriage shrink.

A child’s survival beyond age 5 increases by 31% when a mother has a high school degree, compared to no education.

Despite the shrinking gender gap, 8% fewer girls complete lower secondary school than boys.

The share of youth not employed or participating in education or job training rose to 23.3%, the highest increase in 15 years.

Global studies find there is a 9% increase in hourly earnings for every extra year of schooling a child receives.

During COVID, children in Latin America and the Caribbean lost an average of 225 full days of school.

Access to education

We believe providing children access to education and resources ushers them into a world of ideas and knowledge, and creates lasting change in their lives. Supporters provide access to tutoring, computer courses, libraries and more, setting children up for a lifetime of success.

- WHO Youth Violence Research, 2009

- UNICEF The State of the World’s Children, 2009

- UNESCO, 2012

- World Bank eLibrary. “Returns on Investments in Education,” 2002

- UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report, 2017

- The World Bank 2015

- The World Bank 2017

- Globalpartnership.org, Education Data Highlights

- Un.org, Education

- Results.Org, World Poverty and What you Can Do About It

- Lifewater.org, 9 Poverty Statistics that Everyone Should Know, January 28, 2020

This site uses cookies to improve your experience. You can restrict cookies through your browser; however that may impair site functionality.

Are you sure?

My order summary

Informing and Advancing Effective Policy

- Newsletters

- Education Gap Grows Between Rich and Poor, Studies Say

By SABRINA TAVERNISE

Education was historically considered a great equalizer in American society, capable of lifting less advantaged children and improving their chances for success as adults. But a body of recently published scholarship suggests that the achievement gap between rich and poor children is widening, a development that threatens to dilute education’s leveling effects.

It is a well-known fact that children from affluent families tend to do better in school. Yet the income divide has received far less attention from policy makers and government officials than gaps in student accomplishment by race.

Now, in analyses of long-term data published in recent months, researchers are finding that while the achievement gap between white and black students has narrowed significantly over the past few decades, the gap between rich and poor students has grown substantially during the same period.

“We have moved from a society in the 1950s and 1960s, in which race was more consequential than family income, to one today in which family income appears more determinative of educational success than race,” said Sean F. Reardon, a Stanford University sociologist. Professor Reardon is the author of a study that found that the gap in standardized test scores between affluent and low-income students had grown by about 40 percent since the 1960s, and is now double the testing gap between blacks and whites.

In another study, by researchers from the University of Michigan , the imbalance between rich and poor children in college completion — the single most important predictor of success in the work force — has grown by about 50 percent since the late 1980s.

The changes are tectonic, a result of social and economic processes unfolding over many decades. The data from most of these studies end in 2007 and 2008, before the recession’s full impact was felt. Researchers said that based on experiences during past recessions, the recent downturn was likely to have aggravated the trend.

“With income declines more severe in the lower brackets, there’s a good chance the recession may have widened the gap,” Professor Reardon said. In the study he led, researchers analyzed 12 sets of standardized test scores starting in 1960 and ending in 2007. He compared children from families in the 90th percentile of income — the equivalent of around $160,000 in 2008, when the study was conducted — and children from the 10th percentile, $17,500 in 2008. By the end of that period, the achievement gap by income had grown by 40 percent, he said, while the gap between white and black students, regardless of income, had shrunk substantially.

The connection between income inequality among parents and the social mobility of their children has been a focus of President Obama as well as some of the Republican presidential candidates.

One reason for the growing gap in achievement, researchers say, could be that wealthy parents invest more time and money than ever before in their children (in weekend sports, ballet, music lessons, math tutors, and in overall involvement in their children’s schools), while lower-income families, which are now more likely than ever to be headed by a single parent, are increasingly stretched for time and resources. This has been particularly true as more parents try to position their children for college, which has become ever more essential for success in today’s economy.

A study by Sabino Kornrich, a researcher at the Center for Advanced Studies at the Juan March Institute in Madrid, and Frank F. Furstenberg, scheduled to appear in the journal Demography this year, found that in 1972, Americans at the upper end of the income spectrum were spending five times as much per child as low-income families. By 2007 that gap had grown to nine to one; spending by upper-income families more than doubled, while spending by low-income families grew by 20 percent.

“The pattern of privileged families today is intensive cultivation,” said Dr. Furstenberg, a professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania.

The gap is also growing in college. The University of Michigan study, by Susan M. Dynarski and Martha J. Bailey, looked at two generations of students, those born from 1961 to 1964 and those born from 1979 to 1982. By 1989, about one-third of the high-income students in the first generation had finished college; by 2007, more than half of the second generation had done so. By contrast, only 9 percent of the low-income students in the second generation had completed college by 2007, up only slightly from a 5 percent college completion rate by the first generation in 1989.

James J. Heckman, an economist at the University of Chicago, argues that parenting matters as much as, if not more than, income in forming a child’s cognitive ability and personality, particularly in the years before children start school.

“Early life conditions and how children are stimulated play a very important role,” he said. “The danger is we will revert back to the mindset of the war on poverty, when poverty was just a matter of income, and giving families more would improve the prospects of their children. If people conclude that, it’s a mistake.”

Meredith Phillips, an associate professor of public policy and sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles, used survey data to show that affluent children spend 1,300 more hours than low-income children before age 6 in places other than their homes, their day care centers, or schools (anywhere from museums to shopping malls). By the time high-income children start school, they have spent about 400 hours more than poor children in literacy activities, she found.

Charles Murray, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute whose book, “Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010,” was published Jan. 31, described income inequality as “more of a symptom than a cause.”

The growing gap between the better educated and the less educated, he argued, has formed a kind of cultural divide that has its roots in natural social forces, like the tendency of educated people to marry other educated people, as well as in the social policies of the 1960s, like welfare and other government programs, which he contended provided incentives for staying single

“When the economy recovers, you’ll still see all these problems persisting for reasons that have nothing to do with money and everything to do with culture,” he said.

There are no easy answers, in part because the problem is so complex, said Douglas J. Besharov, a fellow at the Atlantic Council. Blaming the problem on the richest of the rich ignores an equally important driver, he said: two-earner household wealth, which has lifted the upper middle class ever further from less educated Americans, who tend to be single parents.

The problem is a puzzle, he said. “No one has the slightest idea what will work. The cupboard is bare.”

Mentioned Publications

The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: new evidence and possible explanations.

Sean F. Reardon

In this chapter I examine whether and how the relationship between family socioeconomic characteristics and academic achievement has changed during the last fifty years. In particular, I investigate the extent to which the rising income inequality of the last four decades has been paralleled by a similar increase in the income achievement gradient. As the income gap between high- and low-income families has widened, has the achievement gap between children in high- and low-income families also widened?

The answer, in brief, is yes. The achievement gap between children from high- and low-income families is roughly 30 to 40 percent larger among children born in 2001 than among those born twenty-five years earlier. In fact, it appears that the income achievement gap has been growing for at least fifty years, though the data are less certain for cohorts of children born before 1970. In this chapter, I describe and discuss these trends in some detail. In addition to the key finding that the income achievement gap appears to have widened substantially, there are a number of other important findings.

First, the income achievement gap (defined here as the average achievement difference between a child from a family at the 90th percentile of the family income distribution and a child from a family at the 10th percentile) is now nearly twice as large as the black-white achievement gap. Fifty years ago, in contrast, the black-white gap was one and a half to two times as large as the income gap. Second, as Greg Duncan and Katherine Magnuson note in chapter 3 of this volume, the income achievement gap is large when children enter kindergarten and does not appear to grow (or narrow) appreciably as children progress through school. Third, although rising income inequality may play a role in the growing income achievement gap, it does not appear to be the dominant factor. The gap appears to have grown at least partly because of an increase in the association between family income and children's academic achievement for families above the median income level: a given difference in family incomes now corresponds to a 30 to 60 percent larger difference in achievement than it did for children born in the 1970s. Moreover, evidence from other studies suggests that this may be in part a result of increasing parental investment in children's cognitive development. Finally, the growing income achievement gap does not appear to be a result of a growing achievement gap between children with highly and less-educated parents. Indeed, the relationship between parental education and children's achievement has remained relatively stable during the last fifty years, whereas the relationship between income and achievement has grown sharply. Family income is now nearly as strong as parental education in predicting children's achievement.

This chapter is now published in the book Whither Opportunity: https://www.russellsage.org/publications/whither-opportunity

You are here

- Sean Reardon

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Reducing Poverty Through Education - and How

About the author, idrissa b. mshoro.

There is no strict consensus on a standard definition of poverty that applies to all countries. Some define poverty through the inequality of income distribution, and some through the miserable human conditions associated with it. Irrespective of such differences, poverty is widespread and acute by all standards in sub-Saharan Africa, where gross domestic product (GDP) is below $1,500 per capita purchasing power parity, where more than 40 per cent of their people live on less than $1 a day, and poor health and schooling hold back productivity. According to the 2009 Human Development Report, sub-Saharan Africa's Human Development Index, which measures development by combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income lies in the range of 0.45-0.55, compared to 0.7 and above in other regions of the world. Poverty in sub-Saharan Africa will continue to rise unless the benefits of economic development reach the people. Some sub-Saharan countries have therefore formulated development visions and strategies, identifying respective sources of growth.

Tanzania case study

The Tanzania Development Vision 2025, for example, aims at transforming a low productivity agricultural economy into a semi-industrialized one through medium-term frameworks, the latest being the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP). A review of NSGRP implementation, documented in Tanzania's Poverty and Human Development Report 2009, attributed the falling GDP -- from 7.8 per cent in 2004 to 6.7 per cent in 2006 -- to the prolonged drought during 2005/06. A further fall to 5 per cent was projected by 2009 due to the global financial crisis. While the proportion of households living below the poverty line reduced slightly from 35.7 per cent in 2000 to 33.6 per cent in 2007, the actual number of poor Tanzanians is increasing because the population is growing at a faster rate. The 2009 HDR showed a similar trend whereby the Human Development Index in Tanzania shot up from 0.436 to 0.53 between 1990 and 2007, and in the same year the GDP reached $1,208 per capita purchasing power parity. Again, the improvements, though commendable, are still modest when compared with the goal of NSGRP and Millennium Development Goal 1 to reduce by 50 per cent the number of people whose income is less than $1 a day by 2010 and 2015.

More deliberate efforts are therefore required to redress the situation, with more emphasis placed particularly on education, as most poverty-reduction interventions depend on the availability of human capital for spearheading them. The envisaged economic growth depends on the quantity and quality of inputs, including land, natural resources, labour, and technology. Quality of inputs to a great extent relies on embodied knowledge and skills, which are the basis for innovation, technology development and transfer, and increased productivity and competitiveness.

A quick assessment in June 2010 of education statistics in Tanzania indicated that primary school enrolment increased by 5.8 per cent, from 7,959,884 pupils in 2006 to 8,419,305 in 2010. The Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) was 106.4 per cent. The transition rate from primary to secondary schools, however, decreased by 6.6 per cent from 49.3 per cent in 2005 to 43.9 per cent in 2009. On an annual average, out of 789,739 pupils who completed primary education, only 418,864 continued on to secondary education, notwithstanding the expansion of secondary school enrolment, from 675,672 students in 2006 to 1,638,699 in 2010, a GER increase from 14.8 to 34.0 percent. Moreover, the observed expansion in secondary school education mainly took place from grades one through four, where the number increased from 630,245 in 2006 to 1,566,685 students in 2010. As such, out of 141,527 students who on an annual average completed ordinary secondary education, only 36,014 proceeded to advanced secondary education. Some improvements have also been recorded at the tertiary level. While enrolment in universities was 37,667 students in 2004/05, there were 118,951 in 2009/10.

Adding to this number the students in non-university tertiary institutions totalled 50,173 in 2009/10 and the overall tertiary enrolment reached 169,124 students, providing a GER of 5.3 percent, which is very low.

The observed transition rates imply that, on average, 370,875 primary school children terminate their education journey every year at 13 to 14 years of age in Tanzania. The 17- to 19-year-old secondary school graduates, unable to obtain opportunities for further education, worsen the situation and the overall negative impact on economic growth is very apparent, unless there are other opportunities to develop and empower the secondary school graduates. Vocational education and training could be one such opportunity, but the total current enrolment in vocational education in Tanzania is about 117,000 trainees, which is still far from actual needs. A long-term strategy is therefore critical to expand the capacity for vocational education and training so as to increase the employability of the rising numbers of out-of-school youths. This fact was also apparent in the 2006 Tanzania Integrated Labour Force Survey, which indicated that youth between 15 and 24 years were more likely to be unemployed compared to other age groups because they were entering the labour market for the first time without any skills or work experience. The NSGRP target was to reduce unemployment from 12.9 per cent in 2000/01 to 6.9 per cent by 2010; hence the unemployment rate of 11 per cent in 2006 was disheartening.

One can easily notice that while enrolment in basic education is promising, the situation at other levels remains bleak in meeting poverty reduction targets. Moreover, apart from the noticeably low university enrolment in Tanzania, only 29 per cent of students are taking science and technology courses, probably due to the small catchment pool at lower levels. While this is so, sustainable and broad-based growth requires strengthening of the link between agriculture and industry. Agriculture needs to be modernized for increased productivity and profitability; small and medium enterprises, promoted, with particular emphasis on agro-processing, technology innovation, and upgrading the use of technologies for value addition; and all, with no or minimum negative impact on the environment. Increased investments in human and physical capital are also highly advocated, focusing on efficient and cost-effective provision of infrastructure for energy, information and communication technologies, and transport with special attention to opening up rural and other areas with economic potential. All these point to the promotion of education in science and technology. Special incentives for attracting investments towards accelerating growth are also emphasized. Experience from elsewhere indicates that foreign direct investment contributes effectively to economic growth when the country has a highly-educated workforce. Domestic firms also need to be supported and encouraged to pay attention to product development and innovation for ensuring quality and appropriate marketing strategies that make them competitive and capable of responding to global market conditions.

It is therefore very apparent from the Tanzania example that most of the required interventions for growth and the reduction of poverty require a critical mass of high-quality educated people at different levels to effectively respond to the sustainable development challenges of nations.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

What if We Could Put an End to Loss of Precious Lives on the Roads?

Road safety is neither confined to public health nor is it restricted to urban planning. It is a core 2030 Agenda matter. Reaching the objective of preventing at least 50 per cent of road traffic deaths and injuries by 2030 would be a significant contribution to every SDG and SDG transition.

Promoting Evidence-Based Prevention Strategies to Mitigate the Harms of Drug Use: The Role of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

The engagement of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime with Member States is particularly focused on interventions addressing early adolescence through schools and families by piloting evidence-based, manualized programmes worldwide.

A Chronicle Conversation with Pradeep Kurukulasuriya (Part 2)

In April 2024, Pradeep Kurukulasuriya was appointed Executive Secretary of the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). The UN Chronicle took the opportunity to ask Mr. Kurukulasuriya about the Fund and its unique role in implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This is Part 2 of our two-part interview.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Congress poured billions of dollars into schools. Did it help students learn?

Cory Turner

2 reports set out to answer whether K-12 students have recovered from the pandemic

Two new studies offer a first look at how much more students learned thanks to federal pandemic aid money. Blend Images - JGI/Jamie Grill/Tetra images RF/Getty Images hide caption

America’s schools received an unprecedented $190 billion in federal emergency funding during the pandemic. Since then, one big question has loomed over them: Did that historic infusion of federal relief help students make up for the learning they missed?

Two new research studies, conducted separately but both released on Wednesday, offer the first answer to that question: Yes, the money made a meaningful difference. But both studies come with context and caveats that, along with that headline finding, require some unpacking.

How much of a difference did the money make?

$190 billion is an enormous amount of money by any measure. But districts were only required to spend a fraction of the relief on academic recovery, by paying for proven interventions like summer learning and high-quality tutoring. So how much additional student learning did the federal aid actually buy?

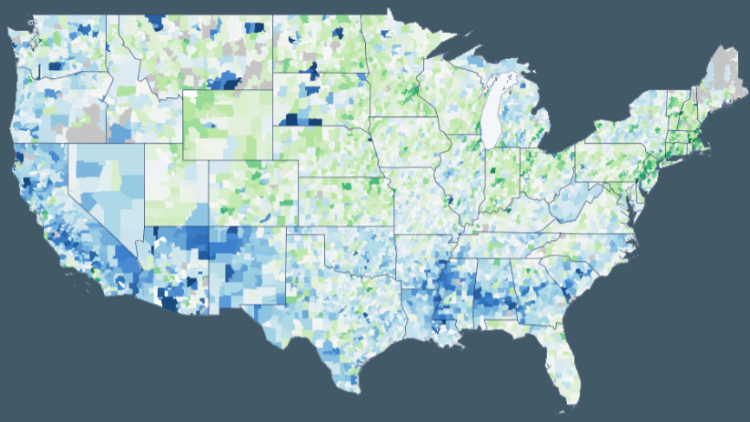

Study #1 , a collaboration including Tom Kane at Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research and Sean Reardon at Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project, estimates that every $1,000 in federal relief spent per student bought the kind of math test score gains that come with 3% of a school year, or about six school days of learning. That’s during the 2022-23 academic year.

Pandemic aid for schools is ending soon. Many after-school programs may go with it

Improvements in reading scores were smaller: roughly three school days of progress per $1,000 in federal relief spending per student.

The federal relief “was worth the investment,” Reardon tells NPR. “It led to significant improvements in children's academic performance… It wasn't enough money, or enough recovery, to get students all the way back to where they were in 2019, but it did make a significant difference.”

Study #2 , co-authored by researcher Dan Goldhaber at the University of Washington and American Institutes for Research, offers a similar estimate of math gains. The increase in reading scores, according to Goldhaber, appeared comparable to those math gains, though he says they’re less precise and a little less certain.

“It did have an impact,” Goldhaber tells NPR, an impact that’s “in line with estimates from prior research about how much money moves the needle of student achievement.”

Who benefited the most?

The federal recovery dollars came in three waves, known as ESSER ( Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund ) I, II and III. The first two waves were relatively small, roughly $68 billion, compared to the $122 billion of ESSER III.

The windfall was distributed to schools based largely on need – specifically, based on the proportion of students living in or near poverty. The assumption being: Districts with higher rates of student poverty would need more help recovering. COVID hit high-poverty communities harder, with higher rates of infection, death, unemployment and remote schooling than in many affluent communities.

Homelessness in the U.S. hit a record high last year as pandemic aid ran out

“These and other factors likely caused greater learning loss during the pandemic and dampened academic recovery,” Goldhaber writes in Study #2, pointing out that, “the Detroit, MI public school district received about $25,800 per pupil across all waves of ESSER… [while] Grosse Pointe, MI (a nearby suburb) only received about $860 per pupil.”

Here’s where the story of these federal dollars gets complicated, because the learning they appear to have bought wasn’t experienced evenly, according to Goldhaber.

In Study #2, he and co-author Grace Falken, found larger academic benefits from federal spending in districts serving low shares of Black and Hispanic students. Though he tells NPR, these patterns “do not necessarily imply that ESSER's impacts vary because of student demographics. Rather, the results could reflect other district characteristics that happen to correlate with the student populations the districts serve.”

Reardon and Kane did not find statistically significant evidence of this kind of variation.

Goldhaber and Falken also found that towns saw more math gains than cities, while rural areas led the way in reading growth. Interestingly, suburban districts generally experienced “smaller, insignificant impacts” from the federal spending in both subjects.

But did the money help enough?

If your standard for “enough” is a full recovery for all students from the learning they missed during the pandemic, then no, the money did not remedy the full problem.

But the researchers behind both studies say that’s an unrealistic and unreasonable yardstick. After all, Congress only required that districts spend at least 20% of ESSER III funds on learning recovery. The rest of the relief came with relatively few strings attached.

Kindergartners are missing a lot of school. This district has a fix

Instead, the researchers say, the money’s effectiveness should be judged by a more realistic standard, based on what previous research has shown money can and cannot buy.

Harvard’s Tom Kane, of Study #1, points out that their results do line up with pre-pandemic research on the impact of school spending, and suggest a clear, long-term return on investment.

“These academic gains will translate into improvements in earnings and other outcomes that will last a lifetime,” Kane tells NPR.

For example, the academic gains associated with every $1,000 in per student spending would be worth $1,238 in future earnings, Kane estimates. Increased academic achievement also comes with valuable social returns, he says, including lower rates of arrest and teen motherhood.

What’s more, Reardon tells NPR, because these federal dollars disproportionately went to lower-income districts, “not only do we find that the federal investment raised test scores, but we also find that it reduced educational inequality.”

But the work’s not over.

In Study #2, Goldhaber and Falken write, “to recover from these remaining losses, our estimates suggest schools would need between $9,000 and $13,000 in additional funds per pupil, assuming the return on those funds is similar to what we estimated for ESSER III.”

They also warn that middle-income districts could continue to struggle – because they experienced academic losses but got less federal aid.

In a presidential election year, it’s unlikely Congress will agree to send schools more money. And Goldhaber worries, as ESSER funds begin to expire this year, districts will have to cut staff.

“Some districts, particularly high poverty, high minority districts, are going to lose so much money that I think teacher layoffs are inevitable,” Goldhaber tells NPR. “So I'm worried that the funding cliff – there's a downside that we're not thinking hard enough about.”

The good news, says Kane, is that ESSER was a massive, “brute force” effort, and a far smaller, state-driven effort could still make a big difference, so long as it’s hyper-focused on academic interventions.

Kane says, “It falls to states to complete the recovery.”

How Federal Pandemic Aid Impacted Schools

- Posted June 26, 2024

- By Elizabeth M. Ross

- Disruption and Crises

- Education Finances

- Education Policy

- Education Reform

- Student Achievement and Outcomes

K–12 schools received nearly $190 billion in federal relief during the COVID-19 pandemic, 90% of which went directly to local districts. Financially disadvantaged districts received the most aid money, but how effective was the money at helping students make up the learning they missed during the pandemic?

Answers can be found in new research which measured the impact of the spending by looking at the average test scores in reading and math from the spring of 2022–2023, for students in grades 3–8. The researchers were not able to assess which intervention strategies were the most effective because school districts were not required to report how they spent the funds they received.

Professor Thomas Kane , economist and co-author of the new report from the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University and The Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University, explains the role that federal relief money played in the academic recovery story in 29 states.

Could you summarize what you found out about the impact of the federal relief money on student achievement during the 2022 to 2023 school year?

We found that $1,000 of federal aid per student that a district spent during the 2022–2023 school year was associated with a 0.03 grade equivalent rise in math achievement (or approximately 6 days of learning) and in reading, the effects were somewhat smaller, a 0.018 grade equivalent (or approximately 3 days of learning). So, the effects were not huge. I think readers might look at that and say, oh gosh, that's a small effect. But what people don't realize is just how strongly related to longer-term outcomes test scores are. So, although the impacts per dollar spent were not large, given the relationship between K–12 test scores and earnings later in life, our estimates imply they were large enough to justify the investment.

In the conclusion of your report, you say that the average recovery was actually larger than what you expected based on your estimate of the effect of the spending. Why was that?

We were surprised when we first got the 2022–2023 data and saw the total magnitude of the gains that year. They were 170% as large as the average annual improvement during the last period of rapid growth in achievement, between 1990 and 2013, in math and double the improvement in reading during that time period.

In this report, we investigated the role that the federal aid played in that growth. Our primary challenge was sorting out how much of the growth was due to spending, versus how much of the growth was related to community poverty — since poorer districts received more aid on average. We took several different approaches to doing that — for instance, using state differences in the Title I formula on which the funding was based and finding high-poverty districts which received large grants (because of the state they were in or because of anomalies in the aid formula) and similarly high-poverty districts with much smaller grants but similar prior trends in achievement. We tried multiple approaches and found similar answers each way we looked at it.

We're still surprised, partially because of the news over the past few years of districts spending the federal relief on athletics fields and across-the-board pay raises and the implementation challenges districts faced when trying to implement tutoring or recruiting students to summer school. But the dollars seem to have had an impact.

"Imagine if, at the beginning of the pandemic, the federal government did not even try to coordinate efforts to develop a vaccine. Instead, suppose they took all that money and sent it to local public health departments, saying, 'You figure it out.' Some would have succeeded, but many would have failed. That’s exactly what happened in the K–12 response." Professor Thomas Kane

In your report you suggested that parental help at home, efforts on the part of teachers and students, and possibly increases in spending at the local level may have played a role in the recovery effort. And it's interesting because I remember the last time I talked with you , you mentioned your concerns about the lack of coordination with the spending of the federal relief money. Is that still a concern?

Yes, in some ways the federal aid was like the first stage of a rocket — it got us started but was broadly focused and ultimately insufficient to get us all the way there. Part of that was due to a lack of coordination. Each district was developing and implementing plans largely on their own. It could have been much more effectively spent. For instance, research suggests that the cost effectiveness ratio for a high-dosage tutoring program was roughly 10 times as large as the cost effectiveness we found for each $1000 in aid spent.

In the report, we also recommend efforts states should be doing now to continue the recovery, because it's pretty clear that there won't be another federal package, given what's happening in Washington. It’s alarming, but it’s just not on the radar screen of most governors — including here in Massachusetts, where the highest-poverty districts have actually lost additional ground since the pandemic. States have spent the last few years watching districts spend down their federal pandemic relief dollars, not recognizing that the recovery will not be complete when the federal dollars run out. Simply going back to business as usual will leave a lot of our neediest communities further behind than they were before the pandemic. So, we're hoping that these results become a call to action at the state and local level. It’s in governors and state legislators’ hands now. If they don’t step up, poor children will end up bearing the most inequitable and longest lasting burden from the pandemic.

The aid did, by our estimates, seem to have a disproportionate effect on high-poverty districts, mostly because they got a lot more money. But that wasn't enough to completely offset the losses. The highest-poverty districts remain behind as well as the middle-income districts. The wealthiest districts we anticipate will be back to 2019 levels soon, not because they received much federal aid — they did not — but because they did not fall very far behind in the first place.

Are there lessons to be learned overall from the pandemic recovery effort?

I do think it would have been beneficial to give federal regulators and state governments more opportunities to coordinate local efforts — like to plan statewide tutoring programs or to plan statewide summer learning programs. Most of the bigger districts would have had the staff to plan their own efforts, but the medium and smaller districts, they didn't necessarily have the bandwidth to be thinking about planning for major summer learning initiatives and tutoring programs. I think granting states, and the federal government, more say in approving local recovery plans, in ensuring that what districts were planning were sufficient to help students catch up and giving states more money to coordinate efforts would have helped.

Imagine if, at the beginning of the pandemic, the federal government did not even try to coordinate efforts to develop a vaccine. Instead, suppose they took all that money and sent it to local public health departments, saying, “You figure it out.” Some would have succeeded, but many would have failed. That’s exactly what happened in the K–12 response. 90% of the federal aid went directly to local school districts. Some figured it out, but many did not.

States and districts should have plans on the shelf for what happens in the next pandemic. I'm sure there are individual schools that will say that they know exactly what they would do next time. But there has not been that sort of learning at the state level — since most states just took a back seat. I have not heard much planning at the state or federal level about what they would do differently next time — and how they might plan for a major tutoring initiative or assembling materials for summer learning, etc. We're not going to have better coordination next time unless somebody starts planning now.

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Where Have All the Students Gone?

New Research Provides the First Clear Picture of Learning Loss at Local Level

Despite progress, achievement gaps persist during recovery from pandemic.

New research finds achievement gaps in math and reading, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, remain and have grown in some states, calls for action before federal relief funds run out

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 July 2024

Geographical migration and fitness dynamics of Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Sophie Belman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9778-7174 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Noémie Lefrancq ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5991-6169 2 ,

- Susan Nzenze 4 ,

- Sarah Downs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5871-5373 5 ,

- Mignon du Plessis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9186-0679 6 , 7 ,

- Stephanie W. Lo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2182-0222 1 , 8 ,

- The Global Pneumococcal Sequencing Consortium ,

- Lesley McGee 9 ,

- Shabir A. Madhi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7629-0636 5 , 10 ,

- Anne von Gottberg 6 , 7 , 11 ,

- Stephen D. Bentley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8094-3751 1 na1 &

- Henrik Salje ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3626-4254 2 na1

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Bacterial genetics

- Population dynamics

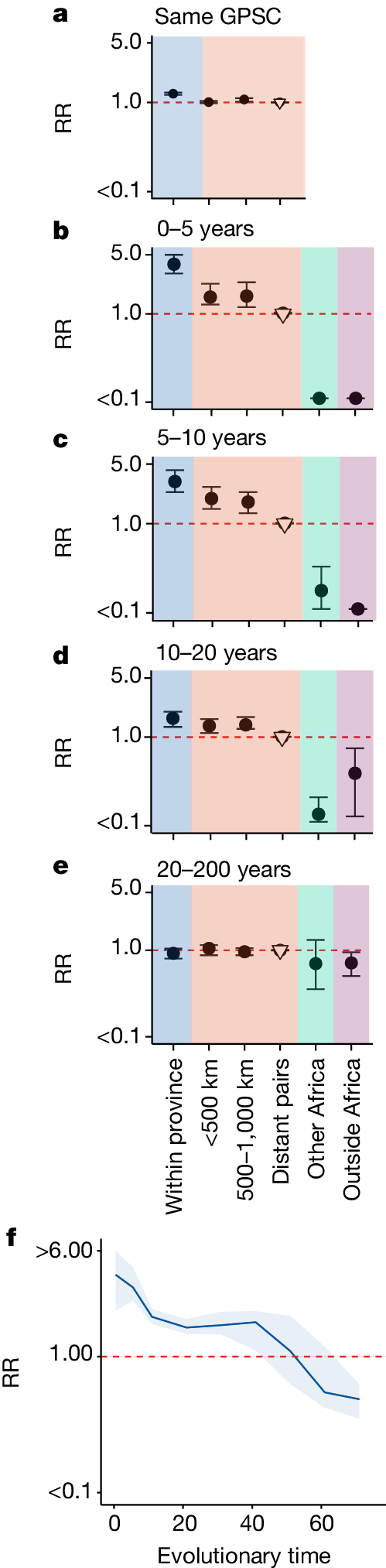

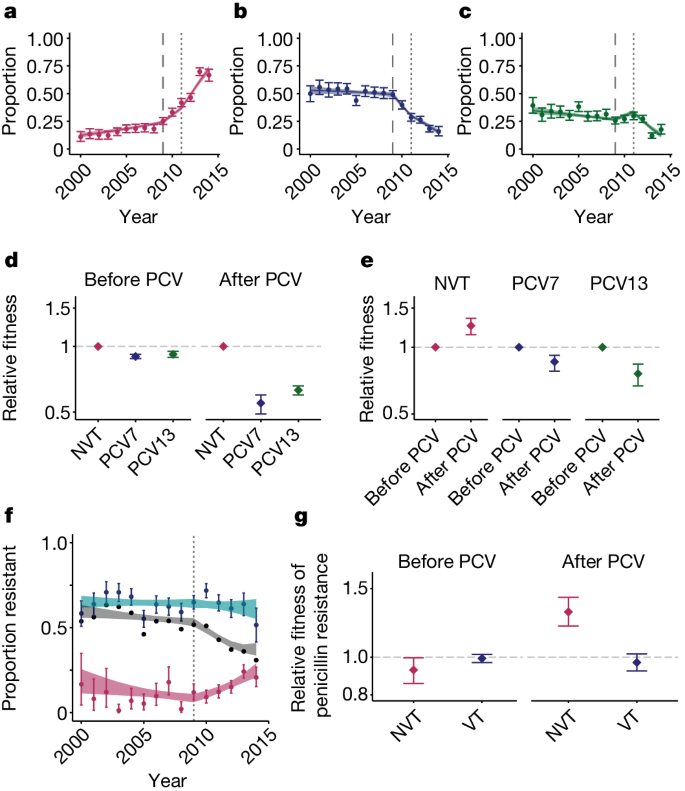

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading cause of pneumonia and meningitis worldwide. Many different serotypes co-circulate endemically in any one location 1 , 2 . The extent and mechanisms of spread and vaccine-driven changes in fitness and antimicrobial resistance remain largely unquantified. Here using geolocated genome sequences from South Africa ( n = 6,910, collected from 2000 to 2014), we developed models to reconstruct spread, pairing detailed human mobility data and genomic data. Separately, we estimated the population-level changes in fitness of strains that are included (vaccine type (VT)) and not included (non-vaccine type (NVT)) in pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, first implemented in South Africa in 2009. Differences in strain fitness between those that are and are not resistant to penicillin were also evaluated. We found that pneumococci only become homogenously mixed across South Africa after 50 years of transmission, with the slow spread driven by the focal nature of human mobility. Furthermore, in the years following vaccine implementation, the relative fitness of NVT compared with VT strains increased (relative risk of 1.68; 95% confidence interval of 1.59–1.77), with an increasing proportion of these NVT strains becoming resistant to penicillin. Our findings point to highly entrenched, slow transmission and indicate that initial vaccine-linked decreases in antimicrobial resistance may be transient.

The greatest public health burden from infectious diseases remains stubbornly endemic pathogens. Once established, pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis , HIV and, now, SARS-CoV-2 are difficult to control, even when vaccines are available 1 . Their persistence in the population can be partially explained by the co-circulation of multiple strains of the same pathogen. Endemic pathogens are complicated to study as we rarely understand the mechanisms that drive spread, including the role of human behaviour and why some lineages increase in prevalence over time whereas others disappear. Underlying genetic diversity is particularly extreme in the case of the bacterium S. pneumoniae (the pneumococcus), which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide because of lower respiratory infections 2 , 3 , 4 . The pneumococcus comprises >100 known antigenically distinct serotypes and >900 classified lineages (also known as global pneumococcal sequence clusters (GPSCs)) 5 , 6 , 7 . Moreover, it is not uncommon for more than 30 antigenically distinct serotypes to co-circulate within a country or region or for a human host to concurrently carry multiple serotypes 8 . We refer to lineage synonymously with GPSC, whereas a strain references any particular circulating phenotype (including specific serotypes and antimicrobial resistance (AMR)). Here we develop mathematical models using thousands of geolocated genome sequences from South Africa collected over a 15-year period to clarify several key uncertainties in pneumococcal migration. We model the rate and breadth of mobility geographically and how fitness changes linked to vaccine implementation and AMR may affect its spread.

The pneumococcus resides in the human upper respiratory tract. Carriage is a prerequisite for disease, and rates of carriage in children under 5 years old range from 20 to 90% 9 . Occasionally, asymptomatic carriage goes on to cause local infections such as otitis media or, more severely, invasive pneumonia and meningitis. More than 500,000 deaths per year linked to pneumococcus are estimated to occur globally 3 , 10 . Penicillin was first used to treat pneumococcal disease in the 1930s, and it successfully reduced pneumococcal disease until the late 1960s when penicillin non-susceptibility was first noted. Multidrug-resistant strains were described soon after penicillin resistance 11 , 12 . By 2019, 19% of deaths associated with AMR had pneumococcal aetiology 13 . In this context, vaccines are pivotal to disease control. A pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine that included 23 serotypes was licensed in the USA in 1983. However, the absence of mucosal immunity has seen it replaced by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) except for in older adults and immunocompromised individuals 14 . PCVs (conjugated with toxin to stimulate mucosal immunity) target a small subset of the polysaccharide capsular serotypes, with the most common formulations including PCV7 and PCV13 (Pfizer) 15 and PCV10 (GlaxoSmithKline) 16 . These target 7, 13 and 10 serotypes, respectively (with all the serotypes included within PCV7 and PCV10 also included within PCV13). In 2021, additional PCV formulations, PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer), were licensed for use in the USA and Europe 17 . Pneumococcal vaccination is dynamic, and new vaccine compositions are frequently tested. Vaccine serotypes are often selected because of their high prevalence and AMR among disease isolates from infants and children. PCVs are now included in 76% of national immunization schedules, with different formulations in different countries. For example, in South Africa, PCV7 was implemented in 2009 and replaced by PCV13 in 2011, excluding PCV10 (ref. 18 ). Despite their success at reducing disease, their use has been linked to serotype replacement by NVTs in both invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) and carriage 8 , 19 , 20 , 21 . In South Africa, this has been characterized by increases in NVT serotypes 8 and 15B among IPD, and increases in NVT serotypes 16F, 24, 35B and 11A among carriage isolates (8, 15B and 11A are now included in PCV20) 20 , 22 , 23 . Although there has been success in predicting the fitness of individual isolates based on the overall gene distribution in a population, quantitative measures of fitness linked to the serotype of individual isolates are lacking 24 , 25 . This includes quantifying the time it takes after implementation for vaccines to affect the serotype composition in the country. Moreover, quantifying the serotype growth before and after vaccine implementation at different time points is needed. These are crucial knowledge gaps, as serotype distributions ultimately drive vaccine development and deployment strategies. In addition, vaccine implementation has resulted in reductions in AMR among both IPD and carriage isolates 20 , 22 , 26 . However, it remains unclear whether these reductions will persist over time at the population level or whether AMR may rebound.

Mathematical models applied to geolocated pathogen genome sequence data are useful to disentangle the changing prevalence of different lineages. However, most phylogeographical models focus on the rate of pathogen flow between locations, which represents the overall effect of multiple transmission chains. Such models therefore consider a different ecological scale to the specific behaviours of infected people and the surrounding population at each transmission generation 27 . The relationship between behaviours of individuals at each transmission step and the overall patterns of pathogen flow between locations are complex and nonlinear. Most existing phylogeographical approaches also struggle to account for changing levels of surveillance in both space and time. Here we develop mechanistic models that use the generation time distribution to estimate the number of transmission events that separate the most recent common ancestors (MRCAs) from each pair of tips in a time-resolved phylogeny. Taken together with measures of human mobility probabilities and human population distribution, we can infer mechanisms of pneumococcal migration at each transmission generation. We implemented this model with a focus on South Africa, where approximately 65% of children ≤5 years of age (35% across all age groups) carry the pneumococcus 28 , 29 . We incorporate both uncertainty in the phylogenetic reconstructions and sampling uncertainty through a bootstrapping approach 30 . We explore the robustness of our approach to highly biased observation processes using simulated data with known parameter values. Finally, we quantify the changing fitness of strains in response to vaccine introduction, including those containing AMR.

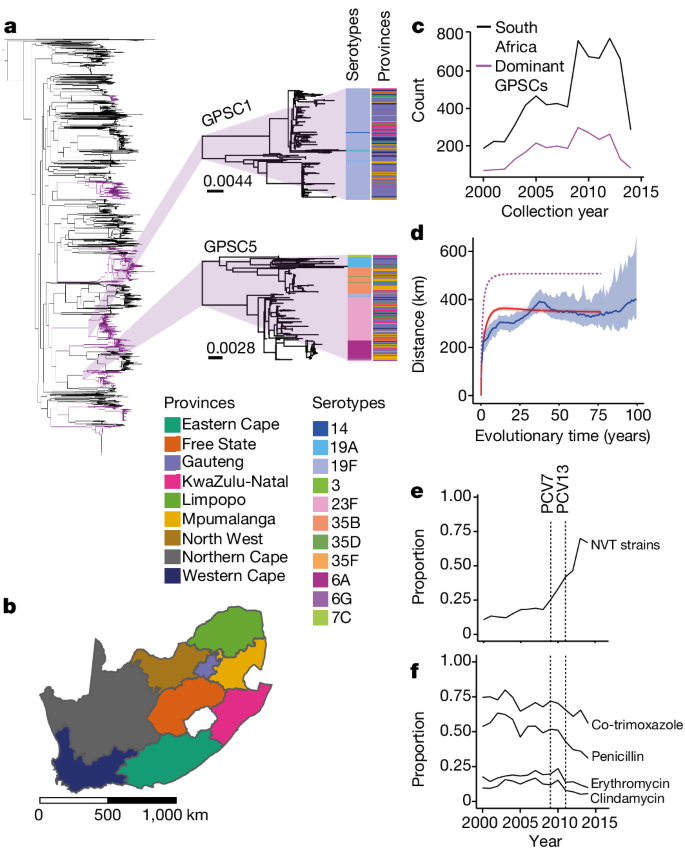

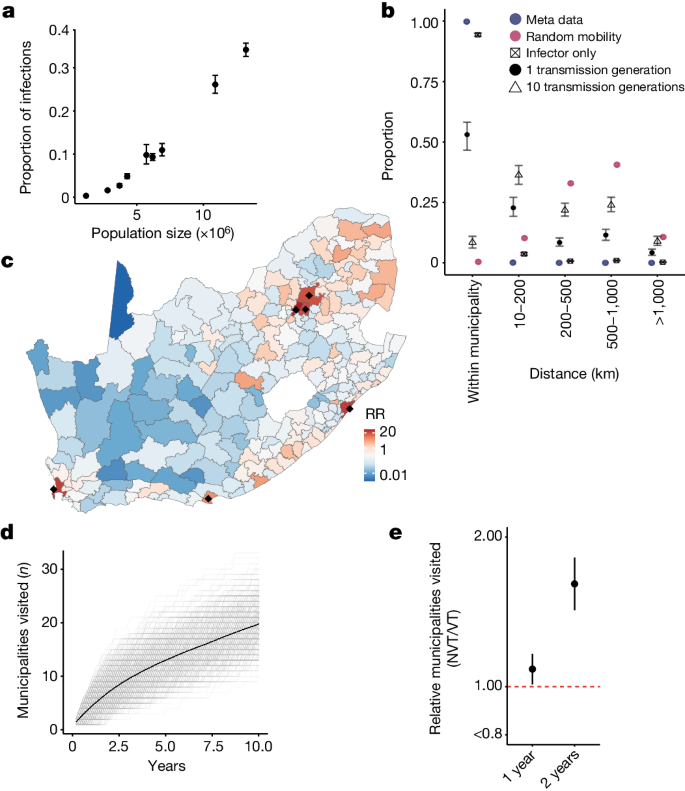

Quantifying spatial structure

In partnership with the South African National Institute for Communicable Disease and the Wits Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit, we sequenced the whole genomes of isolates from each of South Africa’s nine provinces between 2000 and 2014 ( n = 6,910, 5,060 from individuals with invasive pneumococcal disease and 1,850 from carriage studies) (Fig. 1a–c ). Despite the large number of sequences, this dataset only represents a very small proportion ( ≪ 0.1%) of the circulating pneumococcus over this time period. We identified 184 GPSCs with 69 different serotypes (31.9% NVT) (Fig. 1a,e and Supplementary Table 1 ). This diversity persisted across provinces, and the distribution of serotypes within GPSCs did not follow a distinct geographical structure (Fig. 1a ). In silico predicted AMR was common (penicillin, 48.2%; erythromycin, 17.3%, clindamycin, 11.2%; and co-trimoxazole: 68.4%), with similar distributions for isolates from both carriage and disease (Fig. 1f , Extended Data Fig. 10 , Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 3 ).

a , Phylogenetic tree of 6,910 South African isolates included in this study. Dominant GPSCs ( n > 50) are in purple. GPSC1 (top) and GPSC5 (bottom) are highlighted. The columns describe the serotypes and provincial region for each isolate. The branch length legends refer to single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) per site and trees are midpoint rooted. b , Map of the nine provinces of South Africa coloured by province. Scale bar is included in kilometres (km). c , Count of isolates ( n = 6,910) per collection year from 2000 to 2014 used in the lineage-level analysis (black) and the 9 dominant GPSCs used in the divergence time analysis (maroon). d , The mean geographical distance for sequence pairs as a function of cumulative evolutionary distance across all GPSCs with 95% CI (blue). The model fit is shown in red. The implied true pattern of spread is shown in purple, after accounting for a biased observation process. e , The proportion of NVT serotypes across the study period. f , The proportion of in silico predicted AMR isolates for four drugs across the study period. The vertical lines denote the introduction of PCV7 in 2009 and PCV13 in 2011. An interactive phylogeny and metadata are available at Microreact ( https://microreact.org/project/7wqgd2gbBBEeBLLPKonbaT-belman2024southafricapneumococcus ).