Essay on Drawing

500 words essay on drawing.

Drawing is a simplistic art whose concern is with making marks. Furthermore, drawing is a way of communicating or expressing a particular feeling of an artist. Let us focus on this unique form of art with this essay on drawing.

Essay On Drawing

Significance of Drawing

Drawing by itself is an art that gives peace and pleasure. Furthermore, learning the art of drawing can lead to efficiency in other mediums. Also, having an accurate drawing is the basis of a realistic painting.

Drawing has the power to make people more expressive. It is well known that the expression of some people can’t always take place by the use of words and actions only. Therefore, drawing can serve as an important form of communication for people.

It is possible to gain insight into the thoughts and feelings of people through their drawings. Moreover, this can happen by examining the colour pattern, design, style, and theme of the drawing. One good advantage of being able to express through drawing is the boosting of one’s emotional intelligence .

Drawing enhances the motor skills of people. In fact, when children get used to drawing, their motor skills can improve from a young age. Moreover, drawing improves the hand and eye coordination of people along with fine-tuning of the finger muscles.

Drawing is a great way for people to let their imaginations run wild. This is because when people draw, they tend to access their imagination from the depths of their mind and put it on paper. With continuous drawing, people’s imagination would become more active as they create things on paper that they find in their surroundings.

How to Improve Drawing Skills

One of the best ways to improve drawing skills is to draw something every day. Furthermore, one must not feel pressure to make this drawing a masterpiece. The main idea here is to draw whatever comes to mind.

For drawing on a regular basis, one can make use of repetitive patterns, interlocking circles , doodles or anything that keeps the pencil moving. Therefore, it is important that one must avoid something complex or challenging to start.

Printing of a picture one desires to draw, along with its tracing numerous times, is another good way of improving drawing skills. Moreover, this helps in the building of muscle memory for curves and angles on the subject one would like to draw. In this way, one would be able to quickly improve drawing skills.

One must focus on drawing shapes, instead of outlines, at the beginning of a drawing. For example, in the case of drawing a dog, one must first focus on the head by creating an oval. Afterwards, one can go on adding details and connecting shapes.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Drawing

Drawing is an art that has the power of bringing joy to the soul. Furthermore, drawing is a way of representing one’s imagination on a piece of paper. Also, it is a way of manipulating lines and colours to express one’s thoughts.

FAQs For Essay on Drawing

Question 1: Explain the importance of drawing?

Answer 1: Drawing plays a big role in our cognitive development. Furthermore, it facilitates people in improving hand-eye coordination, analytic skills, creative thinking, and conceptualising ideas. As such, drawing must be used as a tool for learning in schools.

Question 2: What are the attributes that drawing can develop in a person?

Answer 2: The attributes that drawing can develop in a person are collaboration, non-verbal communication, creativity, focus-orientation, perseverance, and confidence.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

My Hobby Drawing – Essay on My Hobby Drawing in English for Students

May 23, 2020 by Leya Leave a Comment

Table of Contents

My Hobby Drawing – Essay 1

When I was 5 years old, I loved to play with colors. I always used to use my elder sister’s pencil colors. Since then, my love for drawing and painting has increased. Everyone has some kind of habit and hobbies, and in my opinion, everyone should have hobbies. There are lots of benefits of hobbies. It gives freedom to express. It gives wings to the creator. It can be a stress bursting.

Essay on my Hobby : My favourite hobby drawing

As I mentioned above, my hobby of drawing started when I was 5. At first, I was just using colors to paint. I used just to draw some random pictures. I used to draw something every day. That is how I developed my drawing skills. I used to take part in various competitions. I was very interested in taking part in multiple events. I won lots of medals, trophies, and certificates by taking participate in these kinds of competitions and events. Apart from that, when I improved my skill, I started painting for others. I used to draw for my friends, cousins, and family members. I used to participate in school events. I was popular among my friends in my school days. Everyone wanted to make drawing for them. It gave me more motivation to do something new and to upgrade my skill.

Why do I love drawing?

I love drawing because it gave me respect. It made me popular among my friends. One of the major reasons why I love drawing because it gives me wings to fly. I can draw anything which is in my mind. I can express my thoughts through drawing. I draw various things. I draw for a social cause. I draw about the current situation. I love drawing because I can speak through my drawing and painting without uttering a word. I love drawing because this hobby is my favorite timepass. I draw in every mood. It helps me put my emotions on the canvas. Whenever I feel low or sad, I just put my sketchbook out from the cupboard and start drawing anything, whatever in my mind. People call it freestyle painting, it means without any purpose. After that, I feel very satisfied.

Benefits of Drawing

There is no particular benefit of drawing. But if we talk, there are many. There are several benefits of drawing, which I will be mentioning below.

It develops fine motor skills. Any specialized movement of hand, wrist, and fingers are included in fine motor skills. As an adult, you rely more on these fine motor skills whenever you type, write, drive, or even when you text on mobile. Holding and manipulating writing implements represent one of the best ways to improve fine motor skills. The drawing creates immediate visual feedback. That depends on what kind of writing instrument the child is holding.

It encourages visual analysis. Children don’t understand the concepts that you take for granted. Such as distance, size, color, or textural differences. Drawing offers the perfect opportunity for your child to learn these concepts. It helps children to get knowledge about fundamental visuals. To support this fundamental visual, give small projects to your children on an everyday basis. Which will help them get the difference between near and far, fat and thin, big and small, etc.?

It helps establish concentration. Most children enjoy drawing. this activity provides time to establish concentration. It helps children to concentrate. It helps children to practice drawing and eventually, it helps children to concentrate. It helps children observe small details.

It helps improves hand-eye concentration. In addition to improving fine motor skills, drawing enables your child to understand the connection between what they see and what they do. This hand-eye coordination is important in athletic and academic scenarios such as penmanship lessons, as well as in recreational situations. For a hand-eye coordination boost, have your child draw an object while looking at it or copy a drawing that you made.

It increases individual confidence. As a parent or guardian, you probably love to hear what your child has made new today. He or she gains confidence. When your child has an opportunity to create physical representations of his or her imagination, thoughts, and experiences. Drawing can help your child feel more intrinsic motivation and validity. This will make him or her more confident in other areas that may not come as naturally as drawing.

It teaches creative problem-solving. Drawing encourages your child to solve problems creatively, Along with visual analysis and concentration. When they draw, your child must determine the best way to connect body parts, portray emotions, and depict specific textures. Always Provide specific drawing tasks, such as creating a family portrait, and talk about your child’s color, method, or special choices that can help him or her develop stronger problem-solving skills over time.

Drawing events

As I mentioned, I loved taking part in the competition. When competing in the event, I used to meet many more talented people. It motivated me. I have lots of painter friends now. Whenever I get stuck in the painting, they help me. When I used to participate, I won lots of medals and trophies. It motivated me a lot, too. Several drawing and painting events are happening every day across the world. I used to take part in most of the interschool and state-level competition. I used to take part in online events, too. It helped me know what kind of talents are there in the world.

My future in drawing

I will try to continue my drawing skills in the future also. I am learning more skills related to painting. I am currently focusing on graphic designing and doodling. The world is moving towards digitalization. That is the reason I am trying my hands there too. There is many things to learn from now. I am looking forward to doing that. Moreover, I am very excited.

In the end, I want to add that everyone should have one hobby. It helps a lot in daily life. It helps to build your social image.

My Hobby Drawing – Essay 2

Drawing is something I enjoy doing in my free time and it is my favourite hobby. Although I love to dance and sing, drawing has a special place in my heart.

When I was in kindergarten, my teacher drew a rose on the blackboard using a few simple shapes. I was surprised that it is so easy to create a rose on paper. I tried drawing it in my book and was really very happy when the little triangles I drew started resembling the flower. That was when I started enjoying drawing.

I understood that all complex images can be drawn by breaking them down into simple shapes. I used to follow instructions from children’s magazines on how you can improve your drawing. Recently, my sister has introduced me to YouTube drawing tutorials. Through these videos, I have learnt to draw beautiful Disney princesses and different types of fruits.

Colour Pencils, Crayons, and Oil Pastels

I was taught to use crayons and pencil colours during art classes in school. Later, I started using oil pastels, as these colours are much brighter than the others. Oil pastels add a special colour pop to the painting and these are easy to use, like crayons. There are several artists in the world who specialise in painting with oil pastels. These works of art also look like oil paintings.

The Motivation to Draw

I feel very happy when I complete a painting and my friends admire my work. My teacher has told me that I am very good at colouring. She has also encouraged me to participate in several drawing competitions as a representative of the school. So I take great pleasure in saying that my hobby is drawing.

One of my biggest sources of inspiration is my mother, who draws like a professional artist! She uses watercolours in most of her paintings. I have recently started using watercolours and I feel it is a lot of fun working with this medium.

The beauty of the colours blending into each other cannot be easily expressed in words. I have used watercolours to paint sunsets and to make abstract paintings. I prefer to use the colours in the tube, rather than the watercolour cakes.

Drawing Events

There are several drawing events that people follow these days. Inktober is an annual event where an artist creates one ink drawing each day for the whole month of October. The drawings will be based on prompts that are decided before the event. Artists display their work on social media and other forums for comments and criticisms.

I am looking forward to participating in Inktober this year. It will be fun to see the different drawings that people come up with for the same prompt.

My Future in Drawing

I intend to continue learning new drawing techniques like mandala art, doodling, and oil painting. There is so much to learn out there, and I am excited to try them all! My mother has promised me that she would enrol me into some painting classes where I can improve my skills in my hobby, drawing. I understand that practise is crucial here, and I should try to draw at least one illustration per day to improve my work.

Top Trending Essays for Students

- Sparrow Bird Essay

- Blindness Essay

- Startup India Essay

- School Life Essay

- Swimming Experience Essay

- Essay on Bhagat Singh

- Friendship Essay

- Grandmother Essay

- Sister Essay

- Grandfather Essay

- An Essay on Criticism

- Essay on Imagination

- Essay on Truth

- VolleyBall Essay

- My Favourite song Essay

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

Essay on Drawing Hobby

Students are often asked to write an essay on Drawing Hobby in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Drawing Hobby

What is a drawing hobby.

A drawing hobby means making pictures with pencils, pens, or crayons. It’s like playing on paper. You can draw anything: animals, cars, or your dreams. It’s fun and you can do it anywhere.

Benefits of Drawing

Drawing is good for you. It helps you to be creative and relax. When you draw often, you get better at it. It also makes you feel happy and proud when you finish a picture.

Materials for Drawing

You need simple things: paper, pencils, and colors. You can use markers or paint too. Keep your tools in one place so you can find them easily.

Sharing Your Drawings

Show your drawings to friends and family. They will like seeing your art. You can also put your drawings online to share with more people. It’s nice to get kind words from others.

Practice Makes Perfect

Also check:

250 Words Essay on Drawing Hobby

A drawing hobby is when someone enjoys creating pictures with pencils, crayons, or other tools. It’s like playing with shapes and colors on paper or a computer. People who like to draw often do it in their free time because it’s fun and can make them feel happy and calm.

Drawing is not just about making pretty pictures. It can help your brain grow stronger. When you draw, you learn to see things more carefully and remember details better. It’s also a way to share what you’re feeling without using words. If you’re feeling sad or excited, you can show it in your drawings.

Starting with Drawing

To start drawing, you don’t need fancy tools. A simple pencil and some paper are enough. You can draw anything you like, such as your favorite animal, a scene from a story, or even a dream you had. The more you practice, the better you get.

Sharing Your Art

Once you finish a drawing, you can share it with friends and family. They might enjoy seeing your art, and you can feel proud of what you’ve made. Sometimes, you can even join a drawing club at school or in your community to meet others who like drawing too.

Keep Learning and Enjoying

500 words essay on drawing hobby, introduction to drawing as a hobby.

Drawing is a fun activity that lets you create pictures using pencils, crayons, markers, or any tool that makes marks. It’s like having an adventure on paper, where you can make anything you imagine come to life. You don’t need to be a professional to enjoy drawing; it’s a hobby for everyone, no matter your age or skill level.

The Joy of Drawing

One of the best things about drawing is that it makes you happy. When you draw, you can forget about other worries and just focus on your picture. It’s a time when you can be calm and enjoy making something beautiful or interesting. You can draw your favorite cartoon character, a scene from nature, or even how you’re feeling that day. The joy comes from being free to create whatever you want.

Improving Your Skills

The more you draw, the better you get at it. It’s like learning to ride a bike or swim; practice makes perfect. You can try copying pictures from books or the internet to learn new ways to draw things. There are also classes and videos that can teach you new techniques. The important part is to keep trying and not to get upset if it’s not perfect. Every drawing you do helps you improve.

Drawing can be even more fun when you share your pictures with others. You can show them to your family and friends or put them up on your wall. Some people even share their drawings online for the whole world to see. When you share your art, you can make other people smile and maybe even inspire them to start drawing too.

In conclusion, drawing is a wonderful hobby that is easy to start and can bring a lot of joy. It doesn’t matter if you’re young or old, or if your drawings are simple or detailed. The important thing is that you have fun and keep practicing. So, grab some paper and a pencil, and let your imagination run wild on the page. Who knows, you might discover a talent you didn’t know you had, or you might just find a new way to relax and be happy.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Question and Answer forum for K12 Students

The Joy Of Art: An Essay On My Hobby Drawing

Essay On My Hobby Drawing: Drawing is one of the most ancient forms of human expression. From cave paintings to modern art, drawing has always been an important medium for humans to convey their thoughts and emotions. Drawing as a hobby is a wonderful way to explore your creativity, reduce stress, and improve your focus. In this essay, I will share my personal experience with drawing as a hobby, discuss the benefits of drawing, and provide tips for beginners to improve their skills.

In this blog, we include the Essay On My Hobby Drawing , in 100, 200, 250, and 300 words . Also cover Essay On My Hobby Drawing for classes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and up to the 12th class. You can read more Essay Writing in 10 lines, and essay writing about sports, events, occasions, festivals, etc… The Essay On My Hobby Drawing is available in different languages.

Benefits Of Drawing As A Hobby

Drawing as a hobby has several benefits that go beyond the joy of creating a beautiful piece of art. Drawing can help reduce stress and anxiety by providing a meditative and relaxing activity. When we draw, we enter into a state of flow that takes our mind off our worries and focuses it on the present moment.

Drawing can also be therapeutic. Art therapy is an established form of therapy that uses art as a means of expression and healing. Drawing can help us express our emotions, thoughts, and feelings in a non-verbal way. This can be especially helpful for those who find it difficult to express themselves through words.

Another benefit of drawing is that it can improve our focus and mindfulness. When we draw, we have to pay attention to the details of what we are drawing. This requires us to be fully present in the moment, which can improve our overall mindfulness and awareness.

My Experience With Drawing

I started drawing as a hobby when I was a child. I would spend hours creating doodles and sketches in my notebook. As I got older, I continued to draw, but I never considered it to be more than just a fun pastime. It wasn’t until I started experiencing stress and anxiety in my adult life that I realized the therapeutic benefits of drawing.

Drawing has become a form of meditation for me. When I draw, I am fully immersed in the process, and my mind is free from worries and stress. Drawing has also helped me express my emotions in a non-verbal way. When I am feeling overwhelmed or anxious, I can sit down and draw, and it helps me feel more centered and calm.

Drawing Techniques And Tools

Drawing is a skill that can be improved with practice. There are several drawing techniques and materials that can help beginners improve their skills. One of the most important things for beginners is to start with simple shapes and lines. This will help you develop a steady hand and improve your control over the pencil or pen.

There are several drawing materials that beginners can use, including pencils, pens, charcoal, and pastels. Each material has its own unique qualities, and it’s important to experiment with different materials to find the ones that work best for you.

In addition to the materials, there are several drawing techniques that beginners can learn. These include shading, perspective, and composition. Learning these techniques can help beginners create more realistic and dynamic drawings.

Inspiration And Motivation

Inspiration for drawing can come from anywhere and everywhere. Some people find inspiration in nature, while others are inspired by music or literature. One of the best ways to find inspiration is to explore different art forms and styles. This can help you develop your own unique style and vision.

Motivation is also an important factor in the drawing. Like any skill, drawing requires practice and perseverance. It’s important to set goals and challenges for yourself to stay motivated. You can also find motivation by joining a community of artists or taking a drawing class.

Drawing as a hobby has several benefits that go beyond the joy of creating a beautiful piece of art. Drawing can reduce stress, improve focus and mindfulness, and be therapeutic. Learning drawing techniques and experimenting with different materials can help beginners improve their skills. Finding inspiration and staying motivated are also important factors in becoming a skilled artist. Drawing is wonderful.

Read More: My Hobby Essay

FAQ’s On Essay On My Hobby Drawing

Question 1. Why is drawing my hobby?

Answer: However, I can tell you that people have different reasons for taking up drawing as a hobby.

- Some people find drawing to be a relaxing and meditative activity that helps them reduce stress and anxiety. Others enjoy the creative process and the satisfaction of creating a beautiful piece of art. Some people use drawing as a means of expressing their emotions and thoughts in a non-verbal way.

- Drawing as a hobby can also be a way of challenging oneself and improving one’s skills. Learning new techniques and experimenting with different materials can be a fun and rewarding experience.

- Ultimately, the reasons for why drawing is your hobby are unique to you and may be influenced by your personal experiences, interests, and passions.

Question 2. How do you write a drawing essay?

Answer: Writing a drawing essay involves describing and analyzing a visual artwork, such as a painting, sculpture, or graphic design. Here are some steps to follow:

- Choose an artwork: Select an artwork that you want to write about. It’s best to choose a piece that you have seen in person, but if that’s not possible, find a high-quality image of the artwork to use as a reference.

- Observe and analyze: Look at the artwork carefully and take notes on what you see. Note the colors, shapes, lines, and textures used in the piece, as well as any patterns or motifs. Think about the overall composition of the artwork and how the various elements work together to create a visual impact.

- Research the artist and the artwork: If you’re writing a formal essay, you’ll want to research the artist and the artwork to provide context and background information. Find out when and where the artwork was created, what inspired the artist, and what artistic movements or styles influenced the piece.

- Develop a thesis statement: Your thesis statement should summarize the main point you want to make in your essay. It might be an analysis of the artwork’s meaning, an exploration of the techniques used by the artist, or a comparison of the artwork to other works in its genre.

Question 3. What is your favorite hobby and why is drawing?

Answer: Drawing can be a favorite hobby because it allows for self-expression and creativity. It can also be a relaxing and therapeutic activity that helps to reduce stress and anxiety. Furthermore, drawing can be a way to improve fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination. Additionally, with practice, it can lead to the development of a unique style and a sense of accomplishment.

Question 4. How do you mention drawing in hobbies?

Answer: If you want to mention drawing as one of your hobbies, you can do so in a variety of ways. Here are a few examples:

- “In my free time, I enjoy drawing. It’s a creative outlet that allows me to express myself and explore new ideas.”

- “One of my hobbies is drawing. I find it to be a relaxing and meditative activity that helps me unwind after a busy day.”

Question 5. How do you describe your drawing?

- Describe the subject matter: What is your drawing depicting? Is it a landscape, a portrait, a still life, or something else?

- Highlight the style: What techniques did you use in your drawing? Are there any unique features or elements that make it stand out?

- Comment on the composition: How did you arrange the elements in your drawing? Did you use any particular techniques to create balance or movement?

- Explain your intention: What message or feeling were you trying to convey with your drawing? What inspired you to create it?

Student Essays

Essay on Drawing | Why I Love Drawing Essay For Students

Drawing is the process of using a pencil, pen or other drawing instrument to make marks on paper. It’s an art form that has been around for centuries and has always held great importance in society. The word “draw” comes from the Old English verb “dragan,” which means “to carry.” Its Latin root, “trahere,” means “to pull” or “to draw.” Drawing is about translating an idea into a visual format, often with time taken to explore different ways of making marks on paper until one feels right.

Read the following short & long essay on drawing that discusses brief history, meaning, importance and benefits of drawing. This essay is quite helpful for children & students for school exam, assignments, competitions etc.

Essay on Drawing | Short & Long Essay For Children & Students

Drawings are made with different kinds of tools and techniques, such as the ballpoint pen or pencil. There are a lot drawing instruments in the world which can help people draw what they want.

>>>> Related Post: Essay on Art For Children & Students

Brief history of Drawing

Drawing is the technique of applying mark-making material to a surface. It’s one of those skills that we take for granted in this digital age, and yet it’s a skill that has been practiced in one form or another by every culture throughout history, whether on cave walls, parchments, animal skin or paper.

The history of drawing is the visceral history of human culture; it’s the way we’ve defined ourselves as people, telling stories, recording our surroundings and communicating our ideas.

Drawing is Easy

To draw is to put down lines, textures or colors that describe figures, forms and shapes. The act of drawing can be practiced by anyone; it does not require specialized tools beyond a piece of paper and writing utensils (e.g., pencils). Some people practice drawing as an art form (i.e., visual arts), or in a general manner as required by functional needs (e.g., quick sketches, architectural drawings).

My Hobby Drawing

People who love to do a drawing as their hobby, they will choose some kind of art that the most fit with their favorite style. For example: people who love to do a sketching will buy some good quality pencils and paper together with a nice sketchbook so that they can draw anytime and anywhere they want. However, many of them will choose to go to a bigger space where there is a good lighting and a big table so that they can easily sketch on their project.

People who love to do some painting will have some brushes, oil paint and canvas ready at home. When they feel boring or when they want to express something, they will bring all the art materials out and start their project.

Drawing vs Art

Drawing is a form of art where you use a pencil or a marker to create an image on paper. This can include sketching, doodles, cartoons, portraits or more complicated images that are finely detailed. If the image is on paper and you used some type of writing utensil to create it, then it’s a drawing!

Why people enjoy drawing?

Drawing is a great way to relax and de-stress. Also, drawings look beautiful on your bedroom or living room walls. No matter the age, there is always something new to learn about drawing. It could be learning to draw realistic eyes or learning different shading techniques. It is a great exercise for keeping the brain agile. As you continue to draw, especially if you are drawing objects that are unfamiliar to you, you are engaging the part of your brain that is responsible for problem solving

Drawing for children

Drawing drawing is not only child’s play, but also an important tool for his intellectual and creative development, as well as a means of expression.. Most parents believe that drawing is an act of scribbling, so they do not pay attention to this, that is a big mistake! Drawing – it’s not just scribbling. This is something more than that. To draw means to show imagination, fantasy and memories. Drawing is a means of expression for children (and adults). And it is the best way to develop fine motor skills, this is very important. When you draw, you move your hands and fingers, make shapes with your hands. This is the best way to work out.

>>>>> Also Read: Essay on An Ideal Teacher For Students

Today we have entered into the computer age. The field of drawing has also been profoundly impacted by drawing. There are a lot of drawing software in the world – but few people can draw artwork by using them. Some of them say “Drawing is simple” but if you are not professional, it is difficult to become familiar with the software. The fact that drawing by using these software has many rules which you need to know.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Essays on Drawing

Faq about drawing.

Illustration Essays: Definitions, Templates and Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

I’m a university professor, and in this article, I’m going to show you exactly how to write an illustration essay.

1. What is an Illustration Essay?

An Illustration Essay is an essay designed to describe and explain with examples. You will be required to use examples to reveal details about the subject you are discussing.

In many ways, it is the easiest form of essay because you don’t have to come up with a thesis or argue a point. All you need to do is explain with descriptions and examples (or ‘illustrate’) a subject or phenomenon.

Much like when someone draws a picture to show you what something looks like, an illustrative essay uses words to show what something is.

Related Article: 141+ Illustration Essay Topics

2. Difference between Illustrative and Argumentative Essays

| Aims to show the reader the details about something. | Aims to make a point and convince the reader about your chosen perspective. |

| Descriptive with many examples. | Persuasive with a clear line of argument. |

| Usually doesn’t require . It is usually presumed that something is true, and you’re simply explaining it in detail. | Requires a unique thesis statement that will be prosecuted throughout. |

| Provides examples and explanations. | Provides examples and explanations. |

| Aims to objectively present information. | Aims to present information that defends a certain viewpoint. |

| You’re marked on your ability to explain and describe in detail. | You’re marked on your ability to present a coherent position on a topic. |

You can see that in many ways, an illustrative essay should be easier than an argumentative essay . You can put all your efforts into your explanations and examples.

Aim to create a coherent picture in the reader’s mind about the topic you’re discussing.

3. Definition of ‘Illustrate’

Here are a few definitions of ‘illustrate’:

- Oxford Dictionary says that to Illustrate is to “Explain or make (something) clear by using examples, charts, pictures, etc.”

- MacMillan Dictionary provides this nice, simple explanation: “to show what something is like.”

Let’s now put the term into a few sentences to help clarify it for you just a little more:

- The newspaper article illustrates how the dinosaurs became extinct.

- The story of Abraham Lincoln provides a clear illustration of his life achievements.

- My father’s explanation of how to change oil in a car illustrated the process sufficiently.

Synonyms for ‘Illustrate’

Illustrate may also be interchangeably used with words like:

- Give Detail

4. How to write an Illustration Essay

Here’s how to write an illustration essay:

2.1 How to write your Introduction

The introduction is much like any other in an essay, and therefore I suggest you use the usual I.N.T.R.O formula .

This formula is a way of writing a 5-sentence introduction that orients the reader to the topic. Here’s how it works. Each of the following points forms one sentence of your introduction:

- Inform: Inform the reader of the topic.

- Notify: Notify the reader of one piece of interesting background information about the topic.

- Translate: Translate or paraphrase the essay question.

- Report: Report on your position or argument (This step can be skipped as you will often not need to make an argument)

- Outline: Outline the essay structure. You can use ‘Firstly, secondly, thirdly’ here.

2.2 An example introduction for an illustration essay

This example is for an illustration essay on the topic: Illustrate the various ways young people use social media in their everyday lives.

“Social media has many impacts on young people. Social media is quite new, with the most famous social media site Facebook only being introduced to the world in 2004. This illustrative essay will explain and provide examples of the many ways young people engage with social media every day. The essay will begin with an explanation of what social media is, followed by several illustrative points with examples to give details about what new media is and how it has changed young people’s lives.”

2.3 How to write an illustration paragraph (body paragraph)

Paragraphs in the body of an illustration essay have two purposes:

- Describe and Define: You need to clearly describe and define your subject to the reader. The reader should be left with the impression that you have a deep knowledge of the topic.

- Explain and Exemplify: You need to provide many examples to illustrate your points.

I recommend that you do this in order. Your first few paragraphs should describe and define the subject. Your following paragraphs should give a lot of quality examples.

2.4 Examples of illustrative paragraphs

I’ll keep using the example topic: Illustrate the various ways young people use social media in their everyday lives.

Example of a Describe and Define Paragraph:

“Social media is a form of media that emerged during the Web 2.0 era of the internet. It is unique because it gives people the ability of people to create personal profiles and communicate back-and-forth with one another. It is generally known to have emerged in the early 2000s with websites like MySpace and Facebook, and has changed recently to be heavily mobile responsive with the emergence of smartphones in the 2010s.”

Example of an Explain and Exemplify Paragraph:

“One unique consequence of social media is that it has meant young people are in constant contact with their friends. Whereas in the past young people would have to hang out in person to be in contact, now they can message each other from their homes. For example, young people get home from school and can log into their web forums like Facebook messenger. From here, they can stay in touch and chat about issues that happened at school. While this may be enjoyable, some people also believe that it means young people can continue to be bullied even from within their own bedrooms.”

2.5 How to write a Conclusion for an Illustration Essay

To conclude your illustrative essay, feel free to use the normal conclusion paragraph style. My preferred template for a conclusion is the 5 Cs Conclusion method .

Here’s a brief summary of the 5 Cs Conclusion method. Like the INTRO method, you can write one sentence per point for a 5 sentence conclusion paragraph:

- Close the loop: Refer to a statement you made in your introduction to tie the beginning and end together.

- Conclude: Show your final conclusion on the issue. As this is an illustrative essay that generally does not require a unique thesis statement, this step can be blended with ‘Clarify’.

- Clarify: Show how you have answered the essay question

- Concern: Show who would be concerned about the issue.

- Consequences: Show what the consequences of the issue are for real life.

Read Also: 39 Better Ways to Write ‘In Conclusion’ in an Essay

2.6 Example Conclusion for an Illustrative Essay

Here’s an example conclusion for an illustrative essay on the topic: Illustrate the various ways young people use social media in their everyday lives.

“The beginning of this essay pointed out that social media is quite a new phenomenon. Nonetheless, it appears to have had a significant impact on young people’s everyday lives. This essay has illustrated this fact with examples including points on how many young people use social media at home every night, how it has impact how bullying occurs, and helped them to stay in touch with friends who live long ways away. Parents and teachers should be concerned with this issue in order to help children know when to switch off social media or use it responsibly. Social media is not going anywhere and will continue to impact the ways young people interact with one another on a daily basis.”

5. A Template Just for You

| Essay Section | Instructions |

|---|---|

| Use the to write a 5-sentence introduction that identifies the issue, gives some background information, shows how you will answer the essay prompt, and outlines what will be said in the piece. | |

| Your first one or two body paragraphs should clearly orient the reader to your topic. In your own words, explain exactly what your subject is as if the reader would have no idea. Use academic references whenever possible. In your own words, provide a detailed description of your subject. What are its unique characteristics? Don’t forget to include . | |

| The rest of the ‘body’ of your essay should be dedicated to providing explanations and examples. Use a few paragraphs to explain what your topic or subject is. You can explain why it is the way it is, when it became like that, how it became like that, where it is, and any more distinguishing features of it. This is very important for an illustrative essay. Your examples can show the impacts of your topic on people’s real lives. Or, it could be practical examples of how real people have interacted with your subject. Feel free to check out some news articles on your topic for some clear real-life examples. | |

| Use the to write your conclusion. I recommend you refer back to something you mentioned in the introduction, state how you answered the essay question, explain who should be concerned with this issue, and provide commentary on the consequences of the topic. |

6. Illustration Essay Topic Ideas

I’ve provided a full list of over 120 illustration essay topics you can choose form on this post here .

For a summary of 5 of my favorites, see below:

- Provide an illustration of the lifestyle of American Pilgrims in the first few years of settlement. You can dig deep in this example by giving explanations of the farming practices, initial struggles faced, and the complex relationships between colonizers and Indigenous peoples.

- Provide an illustration of the factory line production model and how it changed the world. Here, you can dig deep with examples of how the production line model was different to anything that came before it. You can also explain it using an example of a product going through a factory, such as a Model T Ford.

- Provide an illustration of the ways the court system seeks to ensure justice is served. Courts are complex places, so you can dig deep here to explain why we have them and how they help keep all of us safe.

- Provide an illustration of human development from birth to 18 years of age. You can dig deep in your explanation of how children move through stages of development before becoming what we consider to be fully grown adults. I selected this example for the illustration essay above.

- Provide an illustration of how and why the Pyramids were built. An illustration of these remarkable structures can help you delve deep into the ways ancient Egypt operated. Discuss the ways pharaohs saw pyramids as spiritual buildings, how they used slaves to build them, and the remarkable engineering coordination required to build enormous structures back before we had machinery to help out!

7. Illustration Essay Example

Topic: “Provide an illustration of human development from birth to 18 years of age. (1000 words)”

Introduction of the Illustration Essay:

Children are born with complete dependence on their parents for their own survival. Over the next 18 years they go through several stages of biological and cognitive development before reaching full maturation. This illustrative essay explores several key ideas about how humans develop in their first 18 years. There are multiple different understandings of how humans develop, and several of the major ones will be illustrated in this essay. First, the key ideas behind human development are defined and described. Then, several examples of key parts of human development in childhood are presented with a focus on Piaget’s approach to human development.

Body Paragraphs of the Illustration Essay – Definition and Description:

Human development is the process of human growth from birth through to adulthood. It is a process that takes somewhere between 16 and 25 years, although most western societies believe a child has reached adulthood on their 18 th birthday (Charlesworth, 2016). The process behind child development has been defined and described in multiple different ways throughout history. Two of the key theorists who describe child development are Piaget and Freud. Both believe all children develop in clear maturational stages, although their ideas about what happens in each stage differ significantly (Davies, 2010).

Freud believes that all children develop through a series of psychological stages. At each stage of development, children face a challenge which they must overcome or risk experiencing psychological fixations in adulthood. Freud outlined five stages of child development: the oral (0 – 1 years of age), anal (1 – 3 years of age), phallic (3 – 6 years of age), latency (6 – 12 years of age) and genital (12+ years of age). For each stage, there is a challenge (Fleer, 2018; Devine & Munsch, 2018). These are: weaning off the breast (oral), toilet training (anal), identifying gender roles (phallic), social interaction (latency) and development of intimate relationships (genital). If the child successfully navigates each stage, they will become a well developed adult.

By contrast, Piaget was focused less on psychological development and more on cognitive maturation. Piaget also believes that all children develop in roughly equal stages (Devine & Munsch, 2014). Piaget outlined five stages of development: the sensorimotor (0 – 2 years of age), preoperational (2 – 7 years of age), concrete operational (7 – 11 years of age) and formal operational (11+ years). In each stage, the child is capable of certain tasks, and should be encouraged to master those tasks to develop successfully to the next stage. These tasks include: mastery of the sense and motor skills to navigate the world (sensorimotor), capacity to use language and think using symbols (preoperational), ability to use logic and understand time, space and quantities (concrete operational), and ability to use abstract and hypothetical thinking (formal operational) (Charlesworth, 2016).

Body Paragraphs of the Illustration Essay – Explanations and Examples:

For the remainder of this essay, Piaget’s stages will be used to illustrate how children are perceived to develop. Piaget’s stages are still widely acknowledged as useful for teaching and guiding children through cognitive development, and are generally more well received in contemporary society than Freud’s. Their value in education make them an important set of stages to understand for teacher educators. Furthermore, many educational curricula around the world continue to roughly teach in stages commensurate with Piaget’s stages (Kohler, 2014). They are therefore important stages of child development to understand.

The first stage is the sensorimotor stage (0 – 2). Children in the sensorimotor stage need support to develop skills in navigating their immediate environments. At this stage, children are given objects with various textures, shapes and compositions to allow children to touch and learn about their world (Kohler, 2014). Children in this stage also learn to develop the understanding that when things are out of their sight, they still exist! Piaget called this skill ‘object permanence’. For example, the game ‘peek-a-boo’ is often very entertaining to young children because their parents’ faces appear to disappear from the world, then reappear randomly (Isaacs, 2015; Devine & Munsch, 2018).

The next stage is the preoperational stage (2 – 7). In the preoperational stage, children learn to develop more complex communicative capacities. Children develop linguistic capacities and begin to express themselves confidently to their parents and strangers. Children also develop imaginative skills, and you often see children engaging in imaginative play where they dress up and pretend to be princesses, firefighters and heroes in their stories (Isaacs, 2015). At this young age, children are very egotistical and continue to see themselves as the centre of the world. To help children develop through this stage, parents and teachers should encourage creative writing and praise children whenever they may see things from other people’s perspectives (MacBlain, 2018).

The third stage is the concrete operational stage (7 – 11). At this stage, children learn to think logically about things in their everyday environments. They therefore develop more complex capacities to reason and do mathematical tasks. At this stage teachers tend to encourage children to learn to come to conclusions using reason and scientific observations (MacBlain, 2018). At this level many children are able to see things from others’ perspectives, but remain focused on their own lives and things in their immediate environments (Kohler, 2014).

Lastly, from ages 11 and up, children develop into the formal operations stage where they can think abstractly. In this stage, ethical and critical thinking emerges. These young people are now starting to think about issues like social justice and politics (Kohler, 2014). They also develop the capacity to do more complex mathematical tasks in the realm of abstract rather than concrete maths. A real life example may include the capacity to complete algebraic tasks. This is why algebra tends to become a part of mathematics curricula in middle and high school years (Charlesworth, 2016; MacBlain, 2018).

While Piaget’s stages are widely acknowledge to be accurate for ‘normal’ development, there is criticism that these stages do not reflect the development of children across all cultures and abilities. For example, children with autism may develop at faster or slower rates (Isaacs, 2015). Similarly, it appears children in some non-Western cultures develop concrete operations at a much younger age than children in Western societies. Thus, other theorists like Vygotsky have demonstrated that we should not see child development in set rigid stages, but instead think of development as being heavily influenced by social and cultural circumstances in which children develop (MacBlain, 2018).

Conclusion of the Illustrative Essay:

At the beginning of this illustrative essay, it was stated that children use the first 18 years of their life to develop biologically, psychologically and cognitively. Zooming in on cognitive development, this essay has illustrated child development through Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development. Through these stages, it is possible to see how children develop from very dependent and unknowledgeable states to full independence from their parents. Teachers should know about these stages of development to properly understand what level children should be at in their learning and to target lessons appropriately.

References:

Charlesworth, R. (2016). Understanding child development. Los Angeles: Cengage Learning.

Davies, D. (2010). Child development: A practitioner’s guide . New York: Guilford Press.

Fleer, M. (2018). Child Development in Educational Settings . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Isaacs, N. (2015). A Brief Introduction to Piaget. New York: Agathon Press.

Kohler, R. (2014). Jean Piaget. London: Bloomsbury.

Levine, L. E., & Munsch, J. (2018). Child Development from Infancy to Adolescence: An Active Learning Approach . London: Sage Publications.

MacBlain, S. (2018). Learning theories for early years practice . London: SAGE.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 60 Would you Rather Questions for Students (Of all Ages)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Classroom Games Ideas for High School

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Classroom Games Ideas for Middle School

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Classroom Games Ideas (For Elementary School)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Distributed for Intellect Ltd

Writing on Drawing

Essays on drawing practice and research.

Edited by Steve Garner

Increased public and academic interest in drawing and sketching, both traditional and digital, has allowed drawing research to emerge recently as a discipline in its own right. In light of this development, Writing on Drawing presents a collection of essays that reveal a provocative agenda for the field, analyzing the latest work on creativity, education, and thinking from a variety of perspectives. Bringing together contributions by leading artists and researchers, this volume offers consolidation, discussion, and guidance for a previously fragmented discipline. Available for the first time in paperback, it will be an essential resource for artists, scientists, designers, and engineers.

192 pages | 47 halftones, 3 tables | 7 x 9 | © 2008

Art: Art--General Studies

View all books from Intellect Ltd

- Table of contents

- Author Events

- Related Titles

“This book captures the range of current debates, each contributor addresses themes that are significant to the development of drawing both as a practice and as a critical discourse. The book helps to outline an intellectual frame of reference for drawing practices, and allows an interdisciplinary conversation around the role of these activities in the wider world. This is an impressive achievement, as an academic who wishes to explore drawing as a cognitive process and as an artist working in the mass mediated world where the language of drawing has found a vital role, this book will be invaluable for me and to my students.”—Mario Minichiello, Birmingham City University

Mario Minichiello, Birmingham City University

“The past decade has seen a change of attitude towards drawing. Its importance as an element in human intelligence is now widely appreciated. However, there has not been a clear picture of research in the field or an agenda for future investigation. Writing on Drawing fills this gap. It gives an insight into current work and it is clear that a paradigm shift is underway. Drawing is, of course, strongly identified with art and design but it is now being seen in a much broader context. The contributions to this book give a new insight into this fascinating activity.”

Ken Baynes, Loughborough University

“Most art libraries have nothing in their holdings that quite resembles this book. . . . Recommended.”

Table of Contents

Be the first to know.

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

The Gillnetter

The student news site of Gloucester High School in Gloucester, MA

- Don't forget your summer reading! https://ghsreads01930.weebly.com/

- Graduation June 9th, 4:00 p.m. Newell Stadium

- Final exams 6/11 - 6/13

Why I love to draw

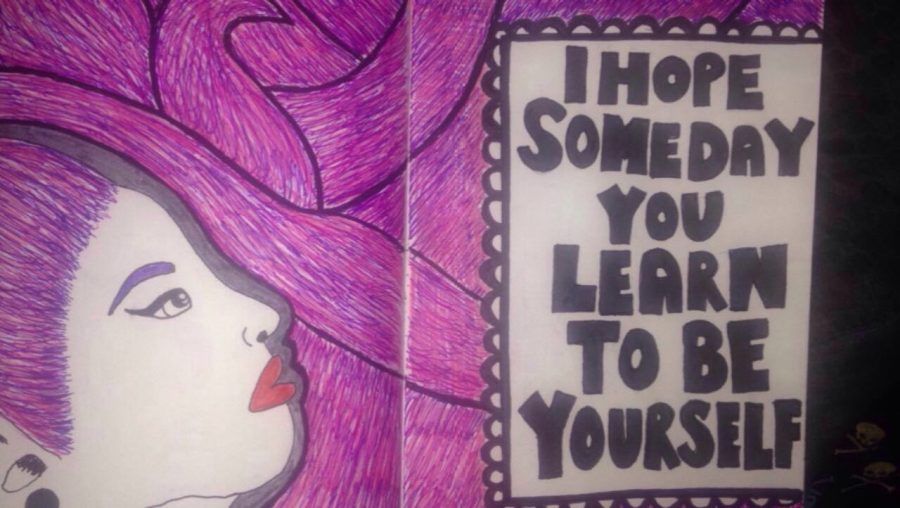

Artwork by Gianna Cabral

GIANNA CABRAL , Staff Writer February 17, 2017

Whether you like cooking or simply playing sports, everyone has a hobby they enjoy doing in their free time. We all need an outlet to let us forget about the world for a while and for me that escape is drawing.

Typically there’s a misconception that you have to be good at drawing in order to enjoy it, but all you really need is a creative mind to be an artist. People can be very judgemental towards one another, but the best part about being an artist is that there is no right or wrong in a piece of art that you have created.

One thing I love about drawing is that you can tell any story you want through your artwork. I find it so fascinating that everyone’s perspective is completely different from one another, and that shows in their artwork. I love to draw pictures that people can interpret in whatever way they choose.

I also love to draw because it gives me a sense of freedom. When I pick up a pencil and draw, I have the ability right at the tip of my fingers to create and destroy anything my heart desires, and that feeling makes me feel so powerful.

Also, as someone who’s not entirely good at putting my feelings into words, drawing enables me to express my emotions without having to speak. Drawing something that represents how I feel allows me to show how I’m feeling when I can’t seem to get the words to come out of my mouth.

Drawing helps me drown out all of the negativity in life when it gets too much. When I have a bad day and don’t want to get out of bed, I like to create art. When I feel sad or angry and don’t totally understand why, putting my thoughts onto a piece of paper through a drawing helps me understand my emotions a little bit better. Even though we all go through sadness and pain, for me creating art allows me to take all of those awful emotions and create something beautiful out of it.

Not only does drawing make me feel better temporarily, but it gives me so much strength, optimism, and confidence that I can do anything. I feel like drawing gives me a purpose in this world. When I create art, it gives me hope that someone might see my artwork and make a connection to it. I could make someone feel empowered simply because they can relate to my artwork. Who knows, maybe one day you’ll see one of my pieces of art and feel inspired, too.

Gianna Cabral is a senior at Gloucester High School and third year Gillnetter staff writer. She can be found creating art or attending concerts. During...

What political issue is most important to you?

Sorry, there was an error loading this poll.

Howard Blackburn : A hero outiside time

Oh, the humanities!

Why GHS should have a gardening class

The argument for a permanent Olympic island

Gloucester needs community land trusts

A Predicament with Parking

Biden’s SOTU speech shows clear distinction between candidates

The case for deleting social media

Periods are hard. Here’s how schools can make them easier.

The U.S. has a gun problem

Comments (1)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

John Landry • Sep 19, 2022 at 3:59 am

My art is essentially a mini-vacation. Whatever I put down, I visit it every day. It’s some place where I can escape for a couple of minutes. But, like I said, it’s a mini-vacation for me.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Plane techniques

- The drawing surface

- Relationship between drawing and other art forms

- Metalpoints

- Graphite point

- Coloured crayons

- Incised drawing

- Pen drawings

- Brush drawings

- Combinations of various techniques

- Mechanical devices

- Applied drawings

- Figure compositions and still lifes

- Fanciful and nonrepresentational drawings

- Artistic architectural drawings

14th, 15th, and 16th centuries

- 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries

- Why is Rembrandt important?

- How was Rembrandt educated?

- What did Rembrandt create?

History of drawing

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Met - How is a Drawing Made?

- Oregon State University - College of Engineering - The Importance of Drawing

- Boise State Pressbooks - Introduction To Art - Drawing

- Smarthistory - Preparatory Drawing During the Italian Renaissance, an Introduction

- Art in Context - Drawing Styles – Finding Your Unique Sketching Style

- The Canadian Encyclopedia - Drawing

- Humanities LibreTexts - Drawing

- drawing - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- drawing - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

As an artistic endeavour, drawing is almost as old as humankind. In an instrumental, subordinate role, it developed along with the other arts in antiquity and the Middle Ages . Whether preliminary sketches for mosaics and murals or architectural drawings and designs for statues and reliefs within the variegated artistic production of the Gothic medieval building and artistic workshop, drawing as a nonautonomous auxiliary skill was subordinate to the other arts. Only in a very limited sense can one speak of centres of drawing in the early and High Middle Ages; that is, the scriptoria of the monasteries of Corbie and Reims in France, as well as those of Canterbury and Winchester in England, and also a few places in southern Germany, where various strongly delineatory (graphically illustrated) styles of book illumination were cultivated .

In the West, the history of drawing as an independent artistic document began toward the end of the 14th century. If its development was independent, however, it was not insular. Just as the greatest draftspeople have been for the most part also distinguished painters, illustrators, sculptors, or architects, so the centres and the high points of drawing have generally coincided with the leading localities and the major epochs of the other arts. Moreover, the same stylistic phenomena have been expressed in drawing as in other art forms. Indeed, drawing shares with other art forms the characteristics of individual style, period style, and regional features. Drawing differs, however, in that it interprets and renders these characteristics in terms of its own unique mediums.

Drawing became an independent art form in northern Italy , at first quite within the framework of ordinary studio activity. But with nature studies, copies of antiques, and drafts in the various sketchbooks (those of Giovannino de’Grassi, Antonio Pisanello, and Jacopo Bellini , for example), the tradition of the Bauhütten studio workshop changed to individual work: the place of “exempla,” models, reproduced in formalized fashion was now being taken by subjectively probing and partially creative drawings. In the early 15th century the international Soft Style of the period still largely predominated over the draftsperson’s individual “handwriting.” At mid-century, however, the differentiation of drawing style according to region and the artist’s personality set in. Essential criteria , destined to remain characteristic for generations, begin to strike the eye.

In drawing produced north of the Alps, the characteristic features lie in the tendency to pictorial compactness and precise execution of detail. Many painters produced individual drawings, but the most notable draftspeople are the otherwise unidentified 15th-century German Master of the Housebook and his contemporary Martin Schongauer . Both of these artists were also major copperplate engravers, so that it is not always easy to determine whether the work is a preliminary sketch or an independent drawing.

In Italian Renaissance drawings, of which there are a great many, the diverging stylistic features of the various artistic regions were particularly evident. What they had in common was the overwhelming importance of the sketch and the study, in contrast to the far rarer finished drawings. The formal and thematic connection with painting is very close even when it was not a question of preliminary drawings. The draftspeople of Venice and northern Italy preferred an open form with loose and interrupted delineation in order to achieve even in drawing the pictorial effect that corresponded to their painters’ imagination.

In central Italy, on the other hand, and especially in Florence , it was the clear contour that predominated, the closed and firmly circumscribed form, the static and plastic character. Corresponding to the functional purpose of drawing, the individual artists’ studios (which, as was the case with the Medicis’ Academy of St. Mark, also had to engage in general educational and humanistic investigations) formed the most significant centres of art drawing. In these large studios, drawing served not only for the probing realization of creative ideas, it was not only study and mediator between the conception and the master’s finished work; it functioned also as teaching aid for the assistants who worked with the master and as a vehicle for the formation and preservation of an individual workshop tradition. Although Leonardo ’s scientific interests were expressed in a large number of drawings, his ideal concept of the human figure is much more frequently preserved in the drawings of his collaborators and successors than in his own. Raphael and Michelangelo were also outstanding draftsmen. Each of them used drawing in order to allow his thoughts about individual works to mature; each had a highly personal drawing style, the one with a soft and rounded stroke, the other with a sculptor’s intermittent and powerful stroke. Probably a great deal of drawing was done in Raphael’s studio, especially if only for the preparation of the engravings after Raphael’s compositions . From Michelangelo’s hand came the first so-called connoisseur drawings that are esteemed as a personal document. They are the precursors of the collector’s drawings that began in the later 16th century (autonomous works, destined for collections).

North of the Alps the autonomy of drawing was championed in the first instance by Albrecht Dürer , an indefatigable draftsman who mastered all techniques and exercised an enduring and widespread influence. The delineatory constituent clearly predominates even in his paintings. This corresponds to the general stylistic character of 16th-century German art, within which Matthias Grünewald , with his freer, broader, and therefore more pictorial style of drawing, and the painters of the Danube school , with their ornamentalizing and agitated stroke, represent significant exceptions. In their metamorphosing of the perceived reality into drawings, the landscapes of Albrecht Altdorfer and Wolf Huber in particular are astonishing documents of a feeling for nature that might almost be called Romantic .

Soberer, incredibly compact in their pictorial concept and yet akin to the Renaissance in their objective viewing, were the portrait drawings of Hans Holbein, the Younger , whose sojourns in 16th-century England proved stimulating to other artists as well. Similar, if less personal than Holbein because of the stricter linearity of their work, were the drawings of the French portraitists Jean and François Clouet . In the Low Countries , where they were combined with the idealized image of Italy (as in the drawings of Lucas van Leyden ), Dürer’s methods gained lasting popularity in the landscape drawings and studies “after life” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder .

Drawing acquired a pivotal significance in the period of Mannerism (c. 1525–1600), both as a document of artistic invention and as a means of its realization. Jacopo da Pontormo in Florence, Parmigianino in northern Italy, and Tintoretto in Venice used point and pen as essential and spontaneous vehicles of expression. Their drawings were clearly related to their painting, both in content and in the graphic method of sensitive contouring and daringly drawn foreshortening.

I write about drawing a lot. I write about how to draw, how to draw more, and how to draw in your own way. But what about why we draw?

This is going to sound melodramatic, but I say this in all seriousness: Drawing has had a profound impact on my life. Without drawing, I don’t know who I would be, where I would be, or how I would deal with everything that happens in life. Drawing is the most powerful tool I have.

But again, why? Why is drawing so powerful? What does drawing do for me? Why do I draw? I’ve been thinking about these questions for a long time, and my answer comes in 3 parts.

1. Drawing helps me see the blobbies inside me

I tend to bottle things up and push things down. It’s taken me 30 years of life to realize this doesn’t work, and eventually everything just crashes down in a wave of exhaustion and confusion. I’ve realized how easy it is to be unaware of my inner thoughts and feelings and how deeply important it is to be in tune with them. So now I’m trying to become more aware of how I’m feeling, and drawing is aiding that process.

Over the years, drawing has evolved from something I did for fun, to something I did for my job, to something that opens up a channel to my inner self. Besides talk therapy , drawing is the only thing I’ve found that can help me see what’s really going on inside.

Almost every time I sit down to draw in my sketchbook, what comes out is a direct reflection of how I’m feeling in that moment. My sketchbook becomes a visual diary that can illuminate feelings I didn’t realize I had. I turn off my thinking brain, move my pen across the paper, then look down and think, ‘Why did I draw a big, bulbous toad with his belly hanging over his feet, droopy eyes, and a dead pan face? Oh, yeah. It’s because that’s totally how I feel right now.’

Drawing in my sketchbook helps me learn about myself. It keeps me honest with myself. It feeds something deep down inside of me, and it allows that something to come to the surface. I call these things blobbies, and drawing can give them a voice.

2. Drawing helps me share the blobbies inside me

These blobbies are inside all of us, and if you’re anything like me, you’re not in the habit of going around talking about them to other people. But this is why we have a stigma around mental health and why we all feel like we’re the only ones struggling with our blobbies. We put on a mask, act like everything’s ok, and in turn believe that everyone else has their stuff together.

My drawing and writing has allowed me to share these blobbies in a way I never could before. Becoming vulnerable with others and sharing what’s really inside me is powerful for both me and whoever sees my art. Because we all struggle with our own blobbies, seeing other people’s can remind us we’re not alone.

Van Gogh once wrote in a letter to his brother,

“ Does what goes on inside show on the outside? Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney.” -Van Gogh

When I share my fire and blobbies, I’m able to connect with other people on an entirely different level. The connection you share with someone who has experienced something similar to you and the validation you feel from hearing a story similar to yours is invaluable.

I used to think that motivational quotes and emotional artwork was melodramatic and over-the-top. But now, having gone through a period of darkness, those works of art have taken on a whole new meaning. When we’re struggling, just having someone to relate to is extremely powerful. Others have been this to me when I needed it, and I aim, by sharing my own blobbies artwork, to be this to others.

3. Drawing helps me deal with the blobbies inside me

Not only does drawing help me become aware of the blobbies inside me, it also helps me clear my head by reflecting on and clarifying those thoughts and feelings.

When I sit down to draw, everything else drops away. The external world fades out and it’s just me, my blobbies, and my sketchbook. Drawing allows me to anchor myself in the present moment, rather than dwelling on the past and stressing about the future. It forces me slow down. It helps me focus on the only thing going on in this one moment: this one line, this one mark, this one color.

If I begin a drawing feeling agitated, grumpy, and stressed out, I almost always finish a drawing feeling more relaxed, content, and at peace. I draw my stress. I draw my worries. I draw my blobbies—often literally. Sometimes as the blobbies leave my pen, they leave me.

Other times, the blobbies are still there inside me, but I now have more awareness and acceptance of them, instead of denial and shame. When I finish a drawing, I’m reminded that my blobbies don’t control my life, I do. It makes me feel more accepting of who I am in this moment. Drawing reminds me that I am capable of change and growth.

Why I Draw: Drawing improves my mental health

Drawing helps me do these things, but I am still far from perfect. I have anxious thoughts, get overwhelmed, shut down, and get stuck in my own head. I can still feel insecure, powerless, stuck, exhausted, grumpy, hangry, unaware, depressed, and stressed out. Sometimes my blobbies run the show without me even knowing.

I am so very imperfect.

But that is precisely why I need drawing.

Thanks for reading, and I hope drawing can do the same for you.

Let me know why you draw by commenting below!

<3, Christine

Join 10,000+ subscribers!

Sign up for my Substack email newsletter to get all my newest essays straight in your inbox!

- 📖 Might Could Essays

- ✏️ Might Could Draw Today

- 📚 Might Could Make a Book

Home — Application Essay — Liberal Arts Schools — About Drawing: Color and Form as a Way to Express Myself

About Drawing: Color and Form as a Way to Express Myself

- University: Macalester College

About this sample

Words: 621 |

Published: Jul 18, 2018

Words: 621 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

I've decided to write my college essay about drawing because, by now, color and form are two essential ways I express myself. In my art I often draw myself as a stick figure with a shock of bright red hair. My family, friends, and even strangers have always commented on the thousands of freckles that pepper my body. This may be why I first began to notice the colors and forms that surround me and to use them for myself. I painted my room orange with a thick magenta stripe. I wear vibrant clothes with colorful patterns and detailed designs. I am even writing this essay through pictures. First, I draw the moments when I have learned most about myself. Then I write thoughts and words on the sketches I have made.

Say no to plagiarism.

Get a tailor-made essay on

'Why Violent Video Games Shouldn't Be Banned'?

Along the edges of the paper I write some facts about my life: For six summers, I lived with eight girls for a month in a ten-by-twenty-foot cabin. I went to Willard Elementary School in Ridgewood, New Jersey through fifth grade and all I can remember is the playground. My younger sister gets to do things before I did, but at least I don’t throw like a girl. Orange County is full of evangelists and born-again Christians while I am an atheist. My high school was built on an old landfill, but luckily we get a strong breeze from the ocean. Each month I get a $250 allowance. Unfortunately, it is not enough for Disneyland. After six weeks in China, every time I see toilet paper in a bathroom I smile to myself.