Essay on Art

500 words essay on art.

Each morning we see the sunshine outside and relax while some draw it to feel relaxed. Thus, you see that art is everywhere and anywhere if we look closely. In other words, everything in life is artwork. The essay on art will help us go through the importance of art and its meaning for a better understanding.

What is Art?

For as long as humanity has existed, art has been part of our lives. For many years, people have been creating and enjoying art. It expresses emotions or expression of life. It is one such creation that enables interpretation of any kind.

It is a skill that applies to music, painting, poetry, dance and more. Moreover, nature is no less than art. For instance, if nature creates something unique, it is also art. Artists use their artwork for passing along their feelings.

Thus, art and artists bring value to society and have been doing so throughout history. Art gives us an innovative way to view the world or society around us. Most important thing is that it lets us interpret it on our own individual experiences and associations.

Art is similar to live which has many definitions and examples. What is constant is that art is not perfect or does not revolve around perfection. It is something that continues growing and developing to express emotions, thoughts and human capacities.

Importance of Art

Art comes in many different forms which include audios, visuals and more. Audios comprise songs, music, poems and more whereas visuals include painting, photography, movies and more.

You will notice that we consume a lot of audio art in the form of music, songs and more. It is because they help us to relax our mind. Moreover, it also has the ability to change our mood and brighten it up.

After that, it also motivates us and strengthens our emotions. Poetries are audio arts that help the author express their feelings in writings. We also have music that requires musical instruments to create a piece of art.

Other than that, visual arts help artists communicate with the viewer. It also allows the viewer to interpret the art in their own way. Thus, it invokes a variety of emotions among us. Thus, you see how essential art is for humankind.

Without art, the world would be a dull place. Take the recent pandemic, for example, it was not the sports or news which kept us entertained but the artists. Their work of arts in the form of shows, songs, music and more added meaning to our boring lives.

Therefore, art adds happiness and colours to our lives and save us from the boring monotony of daily life.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Art

All in all, art is universal and can be found everywhere. It is not only for people who exercise work art but for those who consume it. If there were no art, we wouldn’t have been able to see the beauty in things. In other words, art helps us feel relaxed and forget about our problems.

FAQ of Essay on Art

Question 1: How can art help us?

Answer 1: Art can help us in a lot of ways. It can stimulate the release of dopamine in your bodies. This will in turn lower the feelings of depression and increase the feeling of confidence. Moreover, it makes us feel better about ourselves.

Question 2: What is the importance of art?

Answer 2: Art is essential as it covers all the developmental domains in child development. Moreover, it helps in physical development and enhancing gross and motor skills. For example, playing with dough can fine-tune your muscle control in your fingers.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2 What is a Work of Art?

Richard Hudson-Miles and Andrew Broadey

Introduction

George Dickie’s (1974) “What is Art? An Institutional Analysis” begins by surveying historical attempts to define art according to necessary and sufficient conditions. As such, it would seem to serve as a useful point of departure to the subject of this chapter. However, reading this essay today, with knowledge of the various challenges to classificatory logic of art history mounted by social and cultural theory, one tends to weary at this endless, perhaps hopeless task. In turn, critical neologisms such as “postmodern” (Jameson 1991; Owens [1980] 2002), “expanded field” (Krauss 1979), “post-medium” (Krauss 2000), “relational” (Bourriaud 2002), “alter-modern” (Bourriaud 2009), and “post-conceptual” (Osborne 2017) have all been introduced as theoretical attempts to supplement, redefine, or differentiate the art historical canon and its attendant taxonomies, periodisations, and categorisations. Dickie himself acknowledges that by the mid-1950s many philosophers had begrudgingly conceded that there are no necessary and sufficient conditions for a work of art. Instead, like Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), one of the most important analytic philosophers, famously suggested about definitions of games ([1953] 2009, 65–66), perhaps we can aim for no more than a series of suggested “family resemblances” which unify some, but never all, of a maddeningly heterogeneous field of artistic practices? A quick survey of the diversity of contemporary art would certainly affirm such conclusions. Nevertheless, this task remains an ongoing concern of philosophical aesthetics, from which one could roughly delineate six approaches, each of which is problematic in its own way. This chapter will introduce each of these approaches, testing them against the irreducible complexity of contemporary artworks. Given this, the chapter might fall short of offering easy answers to the question “What is a Work of Art”?

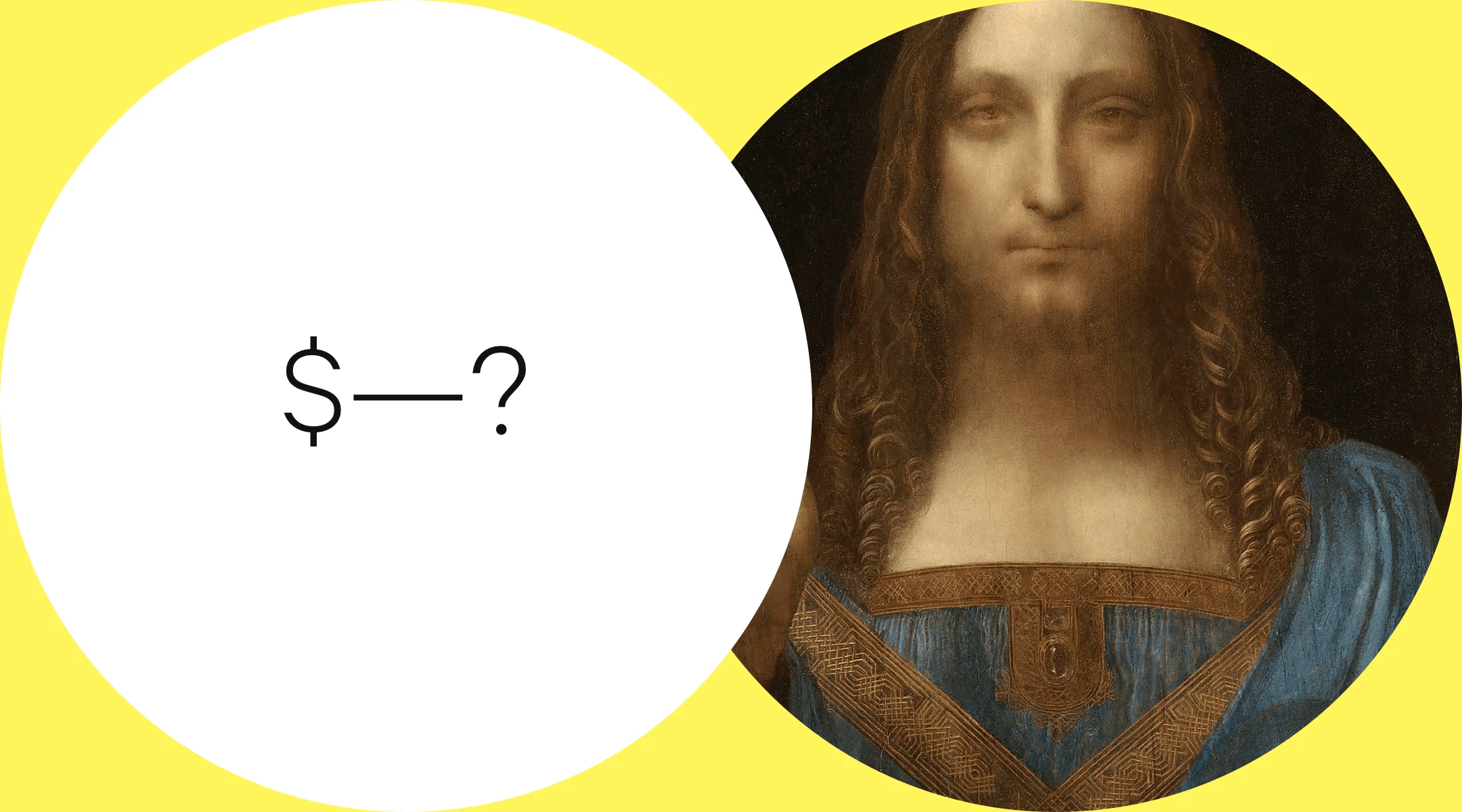

Before proceeding, it is necessary to clarify the more expansive connotations “art” had in Ancient Greece. Indeed, Herbert Read’s (1893–1968) Education through Art (1961, 1-2) insists that most of the problems with modern art education stem from a misreading of the concept of “art” in Plato. In his time, “techne” [ τέχνη ], and its Latin equivalent ars , referred to all forms of human sensuous production, including crafts, social sciences, even skilled labour. Paul Oskar Kristeller (1951) has convincingly demonstrated that the modern sense of “art” was invented in the eighteenth century. Here, the Beaux-Arts tradition ossified five practices (painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry) under the signifier “art.” The rise of a European art market during this period instigated a new need to distinguish artworks from other commodities. Concepts such as “genius,” the “masterpiece,” and a romantic image of the artist, became increasingly important as mechanisms for justifying the uniqueness, desirability, and inflated price tags of “Fine Art” (Shiner 2001, 99–130), especially painting, which remains the most commercial of artforms. Consequences of this were the separation between artisan and artist, and the conceptual narrowing of “Fine Art” to simply painting and sculpture. Conceptual art practices of the twentieth century made significant efforts to broaden the signification of “art” once again, pushing it into what Rosalind Krauss has called “the expanded field” (Krauss 1979). Politically, such practices aimed to create forms of art which were deliberately unclassifiable, immaterial, and non-commodifiable, thus resistant to cooption by the market or gallery systems.

Representational Theories of Art

The words “representation” or “imitation” generally signify philosophical theories of art which, if not directly, can be traced back to the work of Plato (424/423–348/347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Following Plato, such theories suggest art is essentially mimetic, meaning its primary objective is to represent an exterior and more authentic reality. Such theories remained influential during the Renaissance, only fading during the nineteenth century, and persisting in “commonsense” attempts to engage with art today. There is significantly more to the philosophy of artistic representation than Plato and Aristotle, though the classificatory logic of Kristeller’s (1951) “modern system of art” could also be traced back to the work of these two philosophers. Aristotle’s Poetics (335 BCE), in particular, outlines a taxonomic subdivision of the arts and their essential characteristics that remains influential today, especially in literary theory. However, given the limited scope of this introduction, this section will focus mainly on Plato.

As Maria S. Kardaun (2014) argues, the connotative distinction between art as “imitation” or “representation” depends on how one reads Plato. Like techne , mimesis carried expansive connotations in Ancient Greece, including “reflecting,” “expressing,” “mirroring,” and “copying,” alongside “representing” and “imitating.” Therefore, the sophistication of Plato’s art theory, which is sometimes too readily collapsed into his ultimate proscription and censorship of the arts, can be missed with careless reading (Kardaun 2014, 151–2). The persistent, but simplistic and inaccurate (150), reading is based on the famously dismissive Book X of The Republic (380 BCE). [1] From here, the conclusion is usually that Plato rejects all art as “mere imitation” of ideal Forms—abstract but entirely pure concepts such as beauty, virtue, and truth, which precede, yet inform experience. The Forms are knowable only by gods, or perhaps the philosopher-kings Plato envisaged ruling in The Republic . Art can index but never equal them due to the imperfection of human beings. Given that art often represents existing worldly objects and actions which themselves are mere imitations of ideal Forms, it follows that mimetic art represents a thrice-removed simulacrum (a copy of a copy of the Forms), and consequently one of the lowest orders of knowledge.

Yet, despite their imperfections, both art and life strive towards the pure perfection of the Forms. For example, throughout Book V of The Republic , Plato argues that the harmony of the perfectly ordered republican state approximates the “cardinal virtues” of wisdom, courage, discipline, and justice so closely that it soothes the spirit in a manner that transcends even the best works of art. Similarly, despite its apparently low ontological status, Plato suggests the best art can be used as an educational tool, albeit in strictly censored form (bk. III, 376e2–402a4). However, the problematic characteristic of art for Plato is that it stirs our emotions; its affectivity causes us to act in ways that are not rational. Artists rely on divine inspiration, not logic. The audience of a play is seduced by the drama, or the crowd at a musical performance gets entranced by its rhythms. Art is powerful, corrupting, therefore dangerous. This is the primary reason for his infamous proscription of art from the ideal republic (bk. X, 605c–608b).

Whilst still figuring art as imitation, Aristotle’s Poetics pushes back against Plato’s disparaging critique of the mimetic arts. He even suggests that they can benefit society in the following ways. Firstly, he argues that art does not simply imitate reality but accentuates it. For Aristotle, the creative skills of the artist may teach us more about the nature of reality than reality itself. In Chapter 5, he argues that poetry can tell us more than the particulars of history through its expression of universals. Secondly, the emotion central to the experience of art can function as a form of cathartic release for the audience, possibly helping them purge negative feelings and overcome other problems (1449b).

Where imitation theories debate whether art is an accentuation of the world or its mere simulacrum, representational and neo-representational theories focus more on the communicative act. Art does not simply represent the world; it is a representation produced with a specific public in mind whom it speaks to, and in turn, who recognise its content and status as art. Reflecting on the development of such theories, Peter Kivy (1997, 55–83) argues that shift of emphasis means that their real philosophical heritage lies in the work of analytic philosopher John Locke’s (1632–1704) account of language. Book III of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding ([1689] 1979, 223–54) insists words primarily signify ideas, however imperfect, formed in the imagination of an individual (225); communication is then the successful transference of “ideas” from one imagination to another. As Kivy (1997, 58) points out, this Lockean position has been used to support a plethora of “cinematic” accounts of literary and visual art, which figure art as the successfully shared mental representation between artist and audience. Mental representation, in this sense, refers to those images engendered in the mind by poetic literary phrases and dramatic actions, as well as the colours, shapes, and forms of the plastic arts. Kivy raises two main objections to this cinematic model. Firstly, that it is more valid for representational painting than other art forms. Secondly, the term “representation” unhelpfully confuses semantics, consciousness, phenomenology, and presentation (64). Though literature is clearly not non-representational, literary artforms, such as novels, contain large tracts which communicate in ways that don’t involve images. Furthermore, a representational theory of art (literary or visual) tout court (71) denies the differences between the “spectator” of art (theater/public/passive) and its “reader” (modern novel/private/active), which a variety of late-twentieth century art theory (Rancière [2006] 2011, 2009b; Barthes [1971] 1977, 142–9; Mulvey 1975) would expose repeatedly. [2]

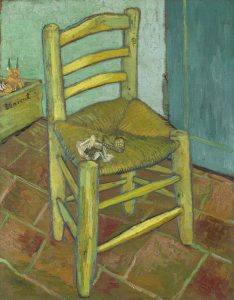

The narrowness of both representational and imitation theories of art is revealed when they are tested against actual artworks. To use a canonical example, it might be useful to ask what is the exact nature of the (Aristotelian) augmentation, (Lockean) “ideas,” or (Platonic) representations offered by Van Gogh’s Chair (1888)? Much art historical ink continues to be spilt arguing about precisely such questions. The Platonic reading would be that it simply imitates the haptic knowledge of an unknown carpenter of Arles, who themselves merely copied the ideal Form of the chair. Another common reading is that it communicates the simplicity and authenticity of the proletarian identity Van Gogh identified with. Using evidence from Van Gogh’s letters, Griselda Pollock and Fred Orton (1978, 58–60) claim these Arles interiors operate as “oblique self-portraits” projecting an ideal of simplicity which he equated with modern masculinity. Later, in J’accuse Van Gog h (Johnstone 1990), Pollock argued that the signature perspectival distortions of his pictorial space were not an attempt to represent anything, but simply accidental results of the technical incompetence of a self-taught amateur. Another reading, attempted by both Albert Lubin (1996, 167-8) and Harold Blum (1956), claims the stylistic differences between Van Gogh’s and Gauguin’s chairs reveal latent repressed homoerotic feelings between the two “friends.” The obvious argument raised by these diverse symbolic readings is that if paintings can sustain such a variety of interpretation, then can it be justifiably argued that they represent any singular artistic vision of the producer?

These questions have been complicated by the emergence of non-representational and immaterial art practices in the late twentieth century. Joseph Kosuth’s (1965) One and Three Chairs , explicitly attempts to foreground questions of meaning and representation in art, and contribute to the further definition and categorisation of art. It is regarded as one of the first pieces of “Conceptual Art.” In Kosuth’s words, the “purest” definition of conceptual art would be that it is an enquiry into the concept of “art,” as it has come to mean (Kosuth [1969] 1991).

Here, Kosuth directly questioned Clement Greenberg’s (1909–94) then dominant account of the development of modernist art (discussed below) as a linear process gradually revealing “medium-specificity”—the essential characteristics common to artistic disciplines such as painting (flatness) or sculpture (three-dimensionality). Instead, Kosuth considered that the readymades attributed to Marcel Duchamp produced a new construction of art beyond enquiry within any given medium. Art now “questioned.” A shift from “modern art” to “conceptual art” had occurred, “one from appearance to conception.” Kosuth talked of “artistic propositions,” whose value derived from their capacity to analyse or question: “the artist, as an analyst is not directly concerned with the physical properties of things. He is only concerned with the way (1) in which art is capable of conceptual growth and (2) how his propositions are capable of logically following that growth” (Kosuth [1969] 1991). Kosuth’s own works attempted to follow this function of analytic proposal. One and Three Chairs (1965) presents an industrially produced chair alongside a photograph of the chair, and a dictionary definition for the word “chair.” Reception of the work takes the form of an enquiry into whether art imitates, communicates, represents, or augments, and also to whether meaning itself originates in the artist, audience, or the structures of language itself.

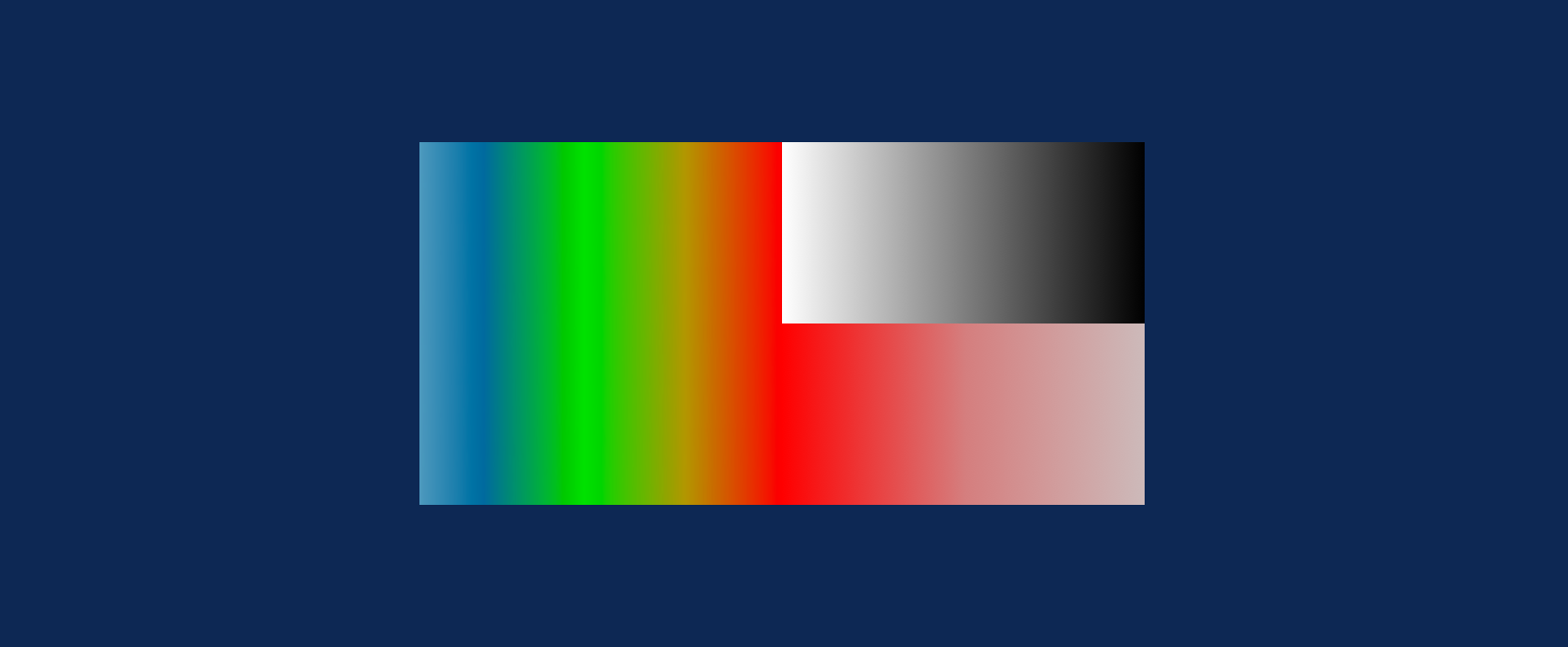

Throughout modernism, critics have consistently correlated form with aesthetic value mediated by judgments of taste. Clement Greenberg considered the aesthetic to be a test of whether a given practice qualified as art. His early text “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) was a defence of taste (high culture) against kitsch, or culture generated out of mass commodity production, such as Hollywood or magazines. Later texts, such as “Modernist Painting” (1960), theorised a developmental logic in the history of painting: a purification of the medium around the values of formalism. Greenberg’s position built upon modernist criticism leading back to the turn of the 20 th Century. Clive Bell (1881-1964) and Roger Fry (1866-1934) identified the realisation of formal relationships in the work of early modernists, such as Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse, with artistic insight and the reception of these works with aesthetic experience. Bell claimed what he termed “significant form” was the distinguishing factor in an artefact’s existence as art (Bell [1914] 2002). Significant form concerns particular compositions of line, colour, and shape that produce aesthetic emotion in the spectator. Roger Fry offers a further distinction, claiming art is a unity of formal elements held in a specific balanced relation that arouses aesthetic emotion (Fry [1909] 2002). A unity of elements is key for Fry. He considered that a work can be superficially ugly, displeasing, or lacking sensuous charm, but can arouse aesthetic emotion because of the unity of elements it conveys.

Each of these positions is rooted in Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) analysis of judgments of taste (Kant [1790] 2000). Kant claims aesthetic judgments concern moments when our rational faculties are set into a state of “free play,” resulting in the claim, “this is beautiful.” On this basis, when we feel aesthetic emotion, or appreciate the significance of the form of a work of art, our cognitive faculties engage the unorganised flux of sound, light, materials, etc. he calls the “manifold” in a state of free play rather than determining this flux as an array of entities in context. When we are able to say of such an object or situation “this is beautiful” we aren’t interested in what it is in itself or what it can do for us, we are rather encountering the manner in which our cognitive faculties can interact with environmental stimuli in a state of free play. For Kant this relation is the marker of the beautiful and the reason why judgments of taste are non-determinate but objective, as no concept is deployed (“this is a …”) but our cognitive faculties are activated in a manner that allows us to reasonably expect the assent of others (“it’s beautiful, isn’t it”). It follows that as objects of taste are an interface for our rational powers and we expect others to assent to our judgments of taste, [3] when we experience beauty, we recognise our participation in a community of sense . Finally, for Kant, art is distinguishable from other objects of beauty, such as natural forms, by virtue of its mediation by a genius capable of configuring forms in order to compel aesthetic judgment. Fry echoes this point in his emphasis on unity.

For Greenberg, art had to be a product of aesthetic judgment: “when no aesthetic value judgment, no verdict of taste, is there, then art isn’t there either” (1971). Greenberg considered modernism to be a self-critical tendency that brought judgments of taste to the fore. Practitioners pursued aesthetic value in their art; in doing so they recognised the constraints of specific media and adapted their work to those constraints. In “Modernist Painting” (1961), Greenberg emphasised a progressive reduction in tactile associations in the work of 20 th Century painters, which paved the way for abstract expressionist reduction of the pictorial field down to a colour space entered by eyesight alone. In the 1960s, Greenberg championed the flat spray-painted colour fields of Jules Olitski as exemplars of “high modernism,” because such works held out to the viewer the possibility of examining the grounds of visual experience: the projective, weightless and synchronous nature of sight.

Diarmuid Costello (2007) notes that Greenbergian criticism and Kantian aesthetics appeared to be closely aligned in the moment of high modernism. He also claimed emergent postmodern critics, such as Rosalind E. Krauss and Hal Foster, believed that challenging its premises meant setting forth an anti-aesthetic rejection of Greenberg. Krauss’s structural analysis of modernism (1979) dismantled high modernist assumptions of art’s aesthetic nature, arguing that modernist artworks, such as the sculptures of Constantin Brancusi, existed in an oppositional relation to architecture and the landscape. This basis in opposition meant that modernist art was in fact a contextual construct. The function of Greenbergian modernism was to suppress the opposition, and naturalise Modernist art as context free, making it in Krauss’s words, “abstraction,” “placeless,” and “self-referential” (1979). With the advent of postmodernism in the late 1960s Krauss argued that minimalism, conceptualism and land art synthesised the terms of the opposition (for example sculpture and architecture) in practice, emphasising art’s contextual existence.

Brian O’Doherty makes the further claim that modernism had always depended on contextual factors to provide conditions conducive to its correct (aesthetic) reception in his analysis of the convention of the “white cube” gallery ([1977] 1986). White cube galleries are uniform, clean, white environments, designed to provide a purified environment of artistic display. O’Doherty’s point is that this design convention historically developed alongside modernism to provide a neutral context for the reception of modernist art. For O’Doherty, the social form of the gallery conditioned modes of contemplative reception that modernist painting necessitated. The gallery was the unremarked context that gave the work “space to breathe” ([1977] 1986). For Costello, the binary nature of this debate (aesthetic/anti-aesthetic) is a function of the critical narrowing of Kantian aesthetics in modernist theory down to an austere formalism. Instead, Costello claims Kant’s theorisation of the aesthetic is broad enough to encompass much of the practice Krauss included in the expanded field, because “it is above all the way in which artworks indirectly embody ideas in sensuous form, by bringing their “aesthetic attributes” together in a unified form that is the focus of judgments of artistic beauty” (Costello 2007). The sensuous embodiment of ideas is the qualification missed by Greenberg, Fry, and Bell. This enables us to conceive the aesthetic as a response that can range across forms of art and non-art in a way that is consistent with the emergence of the expanded field as an aesthetic mobilisation of non-art forms as art.

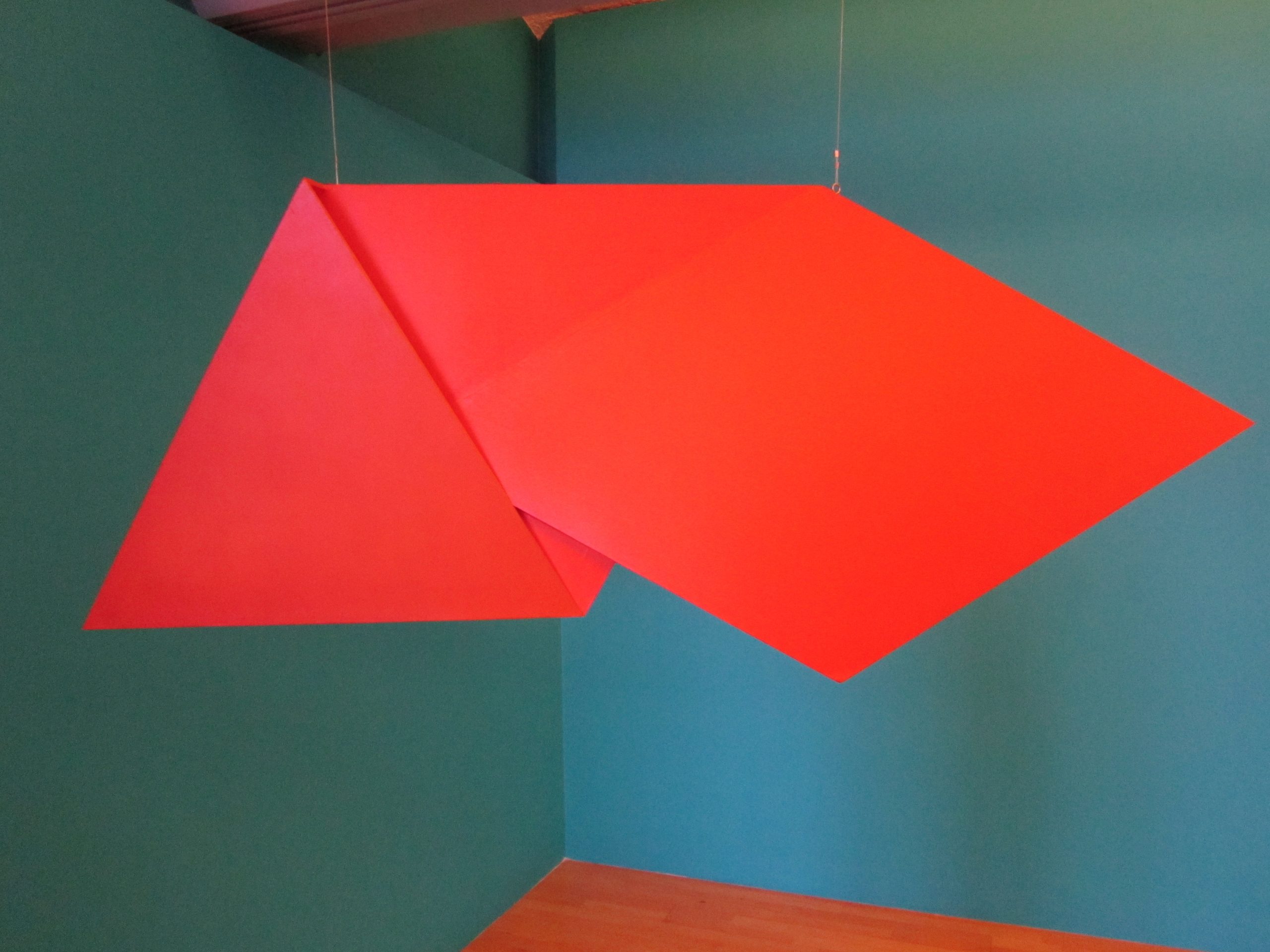

If we test this discussion against an example of art practice then we start to see that a particular attitude to the bounding of form appears to mediate the premises of Bell’s, Fry’s, and Greenberg’s positions. Significant form as criterion or modernist colour space as focus appears to rest on the certitude of its separation from social form. Further to this, we can see that the theorisation of the expanded field as somehow anti-aesthetic also misses the centrality of aesthetic experience to the reception of works operating beyond the bounds of medium specificity. Works by Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica explore form in ways that extend beyond the limits of conventional media and compel attention in a manner that is consistent with the expanded conception of formalism we have outlined. Oiticica was a member of the Rio de Janeiro based Neo-Concrete movement, and around 1960 developed a series of hanging “Spatial Reliefs” that expanded colour forms into architectural space.

Núcleos (Nuclei) (1960–6) consists of hanging geometric panels that occupy a cuboid field. The shapes comprising the work align dynamically at right angles; the central panels are coloured in a rich yellow and graduate to a deep orange at the periphery. The audience moves in and out of the panels as they navigate the gallery, so there is not any strict spatial division between the work and the social space it occupies. This work raises difficult questions for Bell’s position as the encounter with colour forms relates to the architectural structure of the gallery. The work appears to necessitate the collapse of the opposition between work and architecture, or aesthetic and non-aesthetic form. Oiticica’s panels assert the objecthood of colour and break open the static nature of contemplation, turning artistic reception into a dynamic participatory navigation of the work.

The backdrop to Krauss’s and O’Doherty’s interventions is the integration of artistic form into wider social practices of meaning making. Roland Barthes (1971) describes this shift as a movement from work to text (Barthes [1971] 1977). For Barthes, it is the limit or frame of the work that defines the pictorial field and an area of focus for aesthetic emotion. Consequently, he reconceives the work as part of a field of co-related elements whose interactions determine their significance. Rather than a play of pure forms in the artwork, contexts develop through an ongoing play of social forms, whose meaning and status is an object of negotiation. Following Costello, we can argue that when appreciated from the viewpoint of its sensuous manifestation according to a play of our cognitive faculties such semiosis of social form is in fact aesthetic.

If we define art according to its expressivity, we immediately have to contend with the diversity of practices people have considered expressive. For example, the colour harmonies of Wassily Kandinsky’s abstract compositions and Stuart Brisley’s visceral performances are obviously very different types of art practice, but both artists describe their work using the term “expression.” Reflecting this diversity, definitions of art as expression theorise art in terms of enlivenment, purgation, communication, spontaneity, and even transformation. We will navigate this diversity by considering positions developed by Leo Tolstoy and R.G. Collingwood, who focus narrowly on how an artwork might articulate conscious emotion, before considering broader positions advanced by Harold Rosenberg and Gilles Deleuze, for whom expression concerns acts of both individual and social transformation.

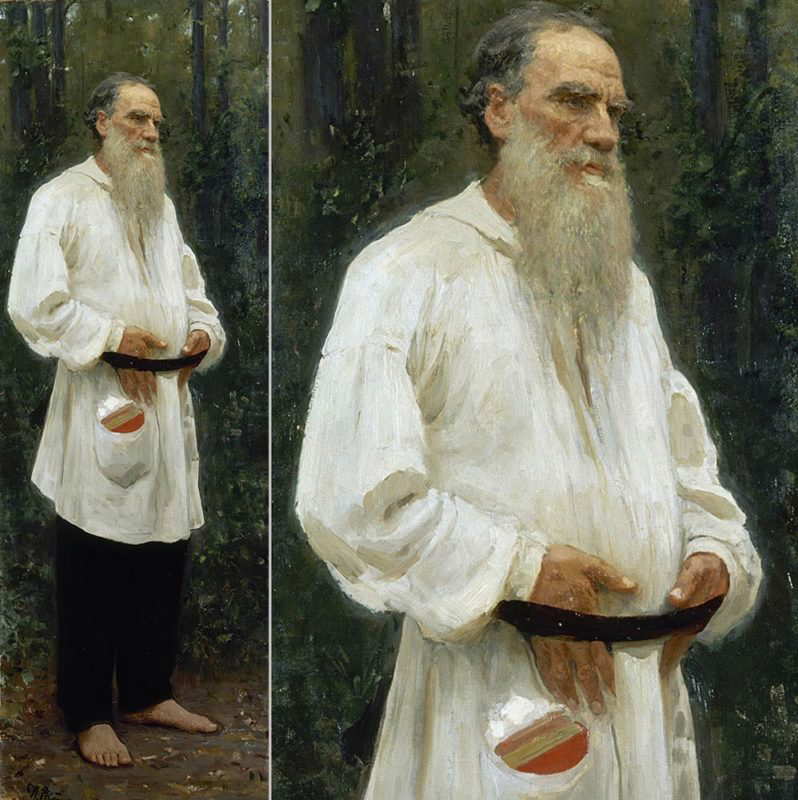

Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) claims art is the transmission of feeling ([1896] 1995). Many different expressions provoke feelings of different kinds in us, but the facility that for Tolstoy distinguishes art is a capacity to produce a unity of feeling between artist and audience. Upon making the work, the artist feels the emotions it expresses and upon receiving the work, each audience member feels this same emotion. We can recognise two assumptions that go unexplained in Tolstoy’s argument: art communicates, and art expresses. Further, he assumes what is subjective for the artist is objective for the audience. Tolstoy’s focus on communication leaves questions concerning the relation of expression to form and representation unanswered. We might also raise a further query around the necessity of premeditation that Tolstoy’s linkage of expression and universal communication seems to require, and the spontaneity that seems to accompany acts of artistic creation.

R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943) resolves some of these issues through his claim that art gives form to expressions that arise in the act of creation (Collingwood [1938] 2013). Art cannot be preconceived (planned and executed): to express is to become conscious of emotion in the act of creation. Similarly, to create is to give plastic reality to feelings that arise in the process of the laying down of forms. By relating artistic expression to creation in this way, Collingwood addresses the assumptions Tolstoy leaves unanswered, but by linking creation to formal arrangement he also limits the range of emotions art provokes to the kinds of aesthetic emotion we previously considered when we discussed Fry.

In contrast to Tolstoy and Collingwood’s narrow theorisations of expression, broader models accommodate unconscious expression and emotions that belong to states of subjective transformation. An early instance of such a model is Aristotle’s analysis of feelings of “fear and pity” ([335 BCE] 1996) experienced by audiences of Greek tragedies, which he identifies with catharsis, or the purging of stored feelings. Aristotle’s analysis makes a change in state or a moment of transformation in the artist or audience member a possible dimension of expression. Aristotle thinks appropriate levels of cathartic response indicate a capacity to engage positively in social life as they demonstrate an ability to interpret others and are hence a marker of virtue.

Poet and critic Harold Rosenberg (1906–1978) theorised abstract expressionist painting in a similar manner, terming it “action painting” (Rosenberg [1952] 2002). Rosenberg argued that painters, such as Lee Krasner, whose works combined improvisational gesture and “all-over” composition, gave symbolic form to emotions that arose in artistic acts of self-questioning, or self-transformation. This transformative potential lay, Rosenberg argued, at the intersection of psychic and plastic forces made to speak for each other in the artist’s address to the blank canvas. For Rosenberg the act of painting was a ritual of self-discovery; symbolic languages were invented through painterly improvisation engaging an array of conscious and unconscious emotion, resulting in moments of self-reinvention. In the words of Clyfford Still (1952), painting was an “unqualified act.”

A subsequent generation of artists viewed expression as action beyond the studio, in the social field. They considered Abstract Expressionism’s pictorial mediation of gesture as indirect when artists could work with the raw material of their practice: their own bodies. To witness Stuart Brisley repeatedly vomiting in a gallery, Gina Pane cutting herself with a razor or spectate on one of Herman Nitsch’s ritualistic actions is to encounter expressions according to an expanded model.

Here, the practitioner explores the potential of their own body to realise the kinds of psychological transformation discussed by Rosenberg through more direct means, refashioning the form of art in accordance to the openness of an event. The intention is to produce change, not just achieve moments of cathartic release.

Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) and Felix Guattari (1930–1992) conceptualise expression in this manner as a force of articulation that demarcates an assemblage (1996). By “assemblage” they mean a dynamic apparatus that articulates a field of social reproduction or transformation. We could talk about the Brisley/gallery assemblage as actions projecting architecturally constrained affect, or the Pane/razor assemblage of laceration and sensation/psychological intensity. Expression here is not merely the feelings of the artistic given plastic form; it is a power to bring forth potential within a structure in order for it to be differently articulated. This transformative aspect defines an event as a moment of rupture that brings forth unformed potentials within the assemblage. Art practices realised in this mode embrace the unknown as a true force of creation by producing a zone of affect that unfolds possibilities of social/psychological change, in contrast to familiar forms and feelings.

The Aesthetic Attitude

Theories of “aesthetic attitude” are less concerned with isolating essential characteristics of artworks, than with describing a certain state of receptivity or the conditions of spectatorship which make the experience of art possible. According to these theories, to attend to art properly we must enact a special kind of distancing, or “disinterestedness.” Here, art is judged outside of the influence of subjective desire or ulterior motivation. The most significant contemporary defender of the theory of the aesthetic attitude is Jerome Stolnitz (1960). For him, “disinterested attention” means focusing on art objects for longer than one would real world objects, sympathetic to their aims, and encountering them for their own sake alone. Before him, Edward Bullough (1880–1934) had characterised the aesthetic attitude as “psychical distance” (1912), where the everyday self is negated in order to generate a space to encounter the world from an aesthetic viewpoint. Stolnitz traces the aesthetic attitude back to the British philosophy of taste articulated in the work of Edmund Burke (1729–97), David Hume (1711–76), Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746), and the Earl of Shaftesbury [Anthony Ashley-Cooper] (1671–1713). However, the most influential (and infamous to hostile commentators) account of this special state of aesthetic receptivity is found in Kant’s Critique of Judgement ([1790, 5: 204–10] 2000, 89–96). In Kant’s own words, “one must not be in the least bit biased in favor of the existence of the thing but must be entirely indifferent in this respect in order to play the judge in matters of taste” (Kant [1790, 5: 205] 2000, 90–1). For Kant, disinterested judgments are non-cognitive—they are outside conceptual knowledge of the object judged, moral interest in it, or any pleasures derived from it. The aesthetic attitude therefore involves willing suspension of the above in order to experience beautiful objects as if one had no prior knowledge of them. His example is a palace, which can be appreciated aesthetically neither by its owner, due to their possessive vanity, nor those who built it, due to their knowledge of the blood and sweat expended on its construction. Similarly, true art is to be distinguished from “remunerative art” ([1790, 5: 304] 2000, 183), whose appeal partly, if not wholly, results from an associated financial reward. A quick, but insufficient, reference also needs to be made to Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), whose The World as Will and Representation ([1819] 2011) contains an important contribution to aesthetic attitude theory. Schopenhauer regards aesthetic contemplation as a form of sanctuary from the violence and enslavement of the world of Will (urges, instincts, cravings). For him, careful aesthetic contemplation brings us closer to the Platonic world of Forms, whilst also giving us a better understanding of the sensory world around us.

The most influential philosophical critique of such theories is Dickie’s “The Myth of the Aesthetic Attitude” (1964). His objection is that “disinterested” contemplation is simply one way of giving attention to art. In terms of philosophical rigour, it is thus indistinct from careful “interested” contemplation. To push Dickie’s argument further, denying the social history of an artwork to emphasise its aesthetic affect will produce a particular idea of art, just as explaining art as a mere reflex of its conditions of production will produce another. Neither approach could claim to have utmost validity in this scenario. A sensitive dialectical approach, incorporating both aesthetic affect and the sociology of art could come closer to attending to the complexity of the question “What is a work of art?”

Aesthetic attitude theories fell out of favour in the late twentieth century, perhaps because of Dickie’s critique, but also because of the increased influence of sociological and materialist theories of art. The claim for disinterestedness as a necessary condition for experiencing art has scandalised many commentators on the left. The classic sociological rebuttal comes from Bourdieu’s (1930-2002) Distinction ([1979] 1996)—a lengthy text, citing an overwhelming array of statistical data to demonstrate that aesthetic “disinterestedness” is a bourgeois illusion, available only to those whose privileged financial situation allows them the luxury of time, or the illusory distance, for such contemplation. According to Kant’s reading, “remunerative artists” are not true artists, despite the fact that no artist can live on fresh air alone. Bourdieu (486-88) concludes that the aesthetic attitude is simply the attitude of the ruling class, and that the purity of the aesthetic attitude is simply veiled contempt for the impurity, and by implication inferiority, of popular, working class culture. As we have seen, contemporary art criticism, such as O’Doherty (1986) and Bishop (2005), has highlighted that the aesthetic attitude finds its physical and spatial equivalent in the hegemonic “white cube” model of display. From the 1960s onwards, radical art practices attempted to problematise the benign image of art galleries as neutralised and universal arenas for disinterested contemplation.

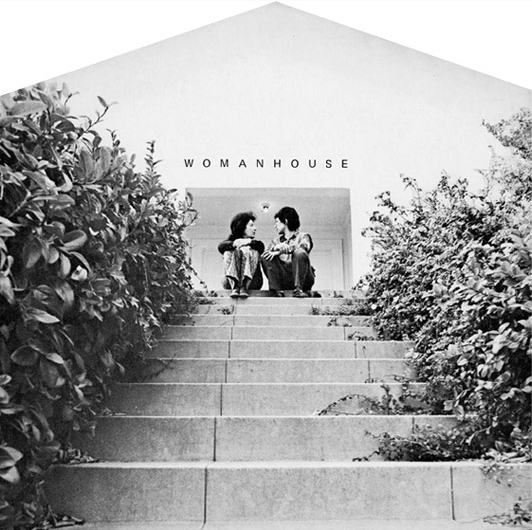

An example would be the exhibition Womanhouse (1972), organised by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro. Over three months, female artists from Cal Arts’ Feminist Art Program renovated a disused Hollywood mansion, turning it into a space for the discussion, production, performance, and display of original artworks. Rather than affecting the faux neutrality of the aesthetic attitude, all exhibited work was explicitly and aggressively “interested.” Men were prohibited from entering the space, and works were given titles such as Menstruation Bathroom (Judy Chicago), Crocheted Environment, or Womb Room (Faith Wilding), and Eggs to Breasts (Robin Weltch and Vicky Hodgetts). The foregrounding of factors specific to the contemporary experience of femininity highlighted the general omission of women from mainstream art galleries and curatorial programmes. The discursive, dialogic, and productive nature of Womanhouse also functioned as a critique of the sterility, neutrality, and passivity of the aesthetic attitude and its attendant white cube model of display. Womanhouse , as political other to such institutions, exposed the exclusion and oppression which the aesthetic attitude has been shown to disguise.

The Institutional Theory of Art

This chapter opened by discussing Dickie’s (1974) “What is Art? An Institutional Theory of Art.” Alongside Arthur Danto’s “The Artworld” (1964), these two texts outline an “institutional theory of art.” For Danto, “The Artworld” describes an enclosed and self-reproducing system of institutions, discourses, critics, publishers, and artists, all of whom are invested in an agreed-upon definition of art. The primary function of the Artworld then is not the production of specific artworks, but the reproduction and dissemination of a dominant idea of art through cultural and educational institutions like schools, universities, museums, or galleries. Dickie’s argument is even more straightforward. For him, art is simply whatever artefact or activity a representative of the Artworld has designated as art. This is not to suggest that artistic practices cannot occur outside the Artworld, such as the activities of hobbyist painters, or countless aspirational student artists, it is simply that these activities will not be recognised as art without its official institutional acknowledgement.

Given that the previous section of this chapter has already suggested that the Artworld is exclusive and non-representative, its absolute power to act as arbitrator of what is art and not-art is highly problematic. Consequently, all manner of radical art practices repeatedly sought to undermine its authority. A recurrent strategy of the “avant-garde,” dating back to Courbet’s Pavilion of Realism (1855), is the establishment of independent exhibitions on the periphery of the Artworld where alternative and oppositional practices can emerge. Such counter-exhibitions have been mounted by the Impressionists (1874–1886), the Dada movement (1916), the Surrealists (1936, 1938), and more recently the YBAs (Young British Artists) (1988). All of these seem to have been recuperated by the Artworld in one form or another, with many gaining canonical status. This capacity of the Artworld to assimilate its symbolic opposition seems to strengthen Dickie’s and Danto’s theses.

From the 1960s onwards, many artists attempted what is now called “Institutional Critique” of the exclusionary and elitist practices of the Artworld. An infamous exhibition by Hans Haacke at the Guggenheim Museum, New York (1971) linked photographs of NYC buildings to financial records, diagrams, and maps of Manhattan to expose links between a Guggenheim trustee and one of New York’s most notorious slum-lords; subsequently his exhibition was cancelled. The feminist artists’ collective The Guerrilla Girls have spent the last three decades covering the billboards outside major art galleries with statistical evidence of the lack of female artists in their permanent collections. Andrea Fraser’s (1989) Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk involved the artist dressing like an employee of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and offering a guided tour of the collection, filled with exaggerations, misinformation, and institutional parody. Not only does this performance satirise the stulted manners and orchestrated behaviours of gallery functionaries, it also highlights the extent to which the audiences of art rely on institutional interpretations to translate their own experiences for them.

Preceding both Institutional Critique and the Institutional Theory of Art, perhaps exceeding them both, is an enduringly influential essay by the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), called “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” ([1935] 2007). Written during the Nazi ascent to power, the text invites “a far-reaching liquidation” of art’s traditional institutions, whose structures he saw as complicit with the social passivity that allowed authoritarian fascism to rise. Benjamin was excited by the capacity (“exhibition-value”) of new technologies of visual production (photography, lithography, cinema) to create new audiences for art outside the Artworld, thus changing the way art is received and understood. With the advent of these new artforms, the individualised reception of art, like viewing a painting alone in a gallery, is replaced by the collective experience of viewing film in a cinema, or a billboard poster in the city space. Because of this, the authority of art institutions to control the meaning of art recedes, not least because art now comes to meet us, in our situations and contexts, rather than vice versa. The consequence of this is that the meaning of art is constantly recontextualised and co-authored at the point of reception, rather than fixed at the point of production by an artist or the moment of exhibition by a gallery or curator.

Benjamin coins the term “aura” to describe the mystifying concepts (creativity, genius, eternal value, uniqueness, mystery) with which galleries, art criticism, and aesthetics surround art production. For Benjamin, these “auratic” discourses not only make art appear more special than it is, but by exaggerating the uniqueness of art and artists, tend to imply that the rest of us are hopelessly ordinary or limited in comparison. For Benjamin, this resembled the general tendency of the public to passively accept social inequality and the status quo, not to mention the hero worship of the “Führer-cult” he witnessed in 1930s Germany. However, the mass dissemination and reproduction of art gradually causes its aura to wither away. This technological “withering” of art’s aura is inseparable from, and impossible without, the creation of a newly energised, critically active, and democratic public sphere, and therefore irreducibly political. The possibilities of new digital media, especially the internet, have multiplied this political effect exponentially. Activist artist groups like Mongrel (2000) can now hack into the Tate Gallery website and reauthor its content. Simple phone technologies can allow users to steal facsimiles of famous artworks, such as the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, and rework them into an infinite array of internet-based memes, GIFs, or fashion accessories. Writing recently, Andrea Fraser (2005) pessimistically recognised that many of the practices of Institutional Critique have become institutionalised. Yet, current digital reproductive technologies have the seemingly infinite capacity to perpetually redefine art and its institutions from the bottom up, and “reactivate the [art] object reproduced,” leading “to a tremendous shattering of tradition which is the obverse of the contemporary crisis and renewal of mankind” (Benjamin [1935] 2007, 221).

Anti-Essentialism

Representation, formalism, expression, aesthetic attitude, and institutionality each constitute dimensions of art practice, but they do violence to the heterogeneity of art practice when we make them function as art’s necessary and sufficient conditions. To traverse the impasse, we might address the question differently, by asking what variable conditions can determine the unfolding of art. This approach attains the flexibility to consider immanent features—expression, form, etc.—in relation to contextual forces.

One example is Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844–1900) positioning of art’s condition between mental processing and the raw data of our senses (Nietzsche 1896). Nietzsche radicalises Kantian aesthetic judgment, pointing out that our viewpoint is articulated through the medium of perception, which is separate from the raw materiality of natural events. Nietzsche’s position is an example of anti-essentialism: what we call truth is something provisional and bound up with the mode of its production. For Nietzsche, perception’s mode is a series of metaphoric abstractions from natural events—from nerve stimulus, to optical information, to mental judgment. The value Nietzsche attributes to art is based on the capacity he thinks art has to help us approach the intensity of those events in nature, and our primal integration within these events. Hence, art conveys our primal perceptual connection with our surroundings by manifesting a play of materiality and conceptual determination. An example of such a practice is Joan Mitchell’s “Rock Bottom” (1960).

The painting comprises a colour field of gestural mark-making, conveying emotions felt by the artist within a landscape. In his essay “The Origin of the Work of Art” (1935–37) Heidegger extends Nietzsche’s analysis to explore how we draw out possibilities of experience through interpretation. He argues that our viewpoint and the particular ways in which it is embedded in the world influences the way the world is disclosed to us. The way we approach disclosure is by circling within the dynamics of experience, between the objects of experience and the ways in which we approach them. The artwork is an aspect of this interpretative circling. It captures and draws out its dynamics. Like Nietzsche’s critique of truth and Heidegger’s analysis of disclosure, Mitchell’s painting articulates judgments as the product of dynamically combined viewpoints, references, memories and sensations.

The attention Nietzsche and Heidegger bring to the embedding of knowledge within specific modes of perception sets the groundwork for deconstruction, which extends these insights into a general analysis of textuality. Textuality assumes material relations that comprise social reality have an inescapable written quality that shapes acts of interpretation. In deconstruction textuality is taken as a condition of knowledge production. Deconstruction addresses art’s ontology by asking what is at stake when we pose the question “What is art?” An example of this deconstructive strategy would be Michel Foucault’s (1926–1984) essay This is Not a Pipe (1983), on Magritte’s painting The Treachery of Images (1928–29), which features the image of a pipe and the caption “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” Foucault claims the pipe cannot be present without the painting. In a similar manner, Paul de Man (1919–1983) argues the practice of philosophy cannot commence without writing (1982). De Man foregrounds how philosophical discourse tends to rest upon metaphor, or figural language, and emphasises how such tropes have to coexist in writing with literal or grammatical meaning, yet even though they appear to mutually exclude each other in the act of reading, texts are always open to literal or figural interpretation. For example, Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”—a story where a community is detained underground and forced to watch shadows, which they mistake for truth, before breaking out of the cave into the blinding light of actual truth—merely describes a series of events if read literally (Plato 380 BCE). Insight comes when we read it figuratively as an allegory of the difference between truth and opinion. Yet, the literal interpretation is also important, because it reveals these tropes as figures of language, compromising the effectiveness of the argument. In order to proceed Plato’s arguments must suppress, or be blind to, literal interpretation, yet blindness runs contrary to the metaphor of illumination central to Plato’s narrative. Such deconstructive analysis reads literal and figural interpretations through each other, a procedure de Man terms “allegories of reading.” Magritte’s painting allegorises in this way by presenting a discontinuity between image and caption, revealing how the interpretation of painting depends on a play of visual aspects and the power of naming. This strategy was later appropriated by Marcel Broodthaers to critique the authority of the public museum in Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles (1968–71).

Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) developed similar insights to frame truth as subject to a process of differing and deferral from itself (Derrida 1967). As de Man notes, words and signs never fully summon forth what they mean but can only be defined through appeal to additional words, from which they differ. Meaning is forever “deferred” or postponed through an endless chain of signifiers. Thus, for Derrida, we reside in a web of language/interpretation that has been laid down by tradition and which shifts each time we hear or read an utterance. Philosophy becomes an act of forensically reading these displacements and instabilities, analyzing the relations of power they manifest. We never arrive at the fixed essences expected by the philosophical tradition, but bear witness to the textual architectures out of which all truth claims arise. Derrida’s (1987) The Truth in Painting seizes upon a passing reference to the “parergon” or frame in Kant’s third critique to demonstrate the codependency of artwork, “Artworld,” and art. [4] For Derrida, the physical frame of a painting can be viewed simultaneously as internal and external to the artwork; the frame is subordinate to the artwork, yet also emphasises and completes it. Also, it can legitimately be regarded as part of the wall of the gallery and part of the painting, collapsing the boundaries between artwork and context. For Derrida, the concept of the parergon can be extended metaphorically to deconstruct the relationship of the artwork to the wider Artworld which acts as its determining frame. Focusing on what “frames” an artwork indicates an instability in any theory of the aesthetic that regards it as separate to social form.

Some of the most significant and sustained challenges to philosophical aesthetics in recent years have come from the work of Jacques Rancière (2009a; 2004). In The Politics of Aesthetics (2004), Rancière introduced the concept of three regimes of artistic production, each of which codifies and delimits what is and what is not recognizable as art in a given epoch. The “representative regime,” stemming from Aristotelian thought, lays down the “rules” of artistic production, including the delimitation of different genres / modes of practice. It also fixes the “principles of convenance”—the styles, methods, images, tropes, and significations proper to each artistic category within this rigid taxonomy. In contradistinction, an earlier “ethical regime” of art, emerging from Platonic thought, judges art according to its truthfulness to an ideal. A third regime, the “aesthetic regime” of modern art production, anarchically undoes these systems of regulation and definition, revealing them as repressive limits on the socio-political capacity of art. Though the concept of these regimes insists that our understanding of art is historically determined, the regimes themselves are meta-historic, unlike the conceptual categories of art history, and can overlap and co-exist in a particular era. For Rancière, the disciplines of philosophical aesthetics and art history are political as they restrict what is knowable as art through the task of categorisation and definition. At the same time, both artistic practice and aesthetics can act as counter-politics to this system by opening aporia within the prevailing regimes of production, exposing the exclusivity and hierarchical ordering of the Artworld, and the a priori ordering of the world, which Rancière refers to as the “distribution of the sensible” (2004, 12), that determines the forms and rights of participation in all of the above.

From narrow definitions of art based on representation, form, expression, or residing in a specific aesthetic attitude or institutional framework, we have developed a position that insists upon such criteria as mutable and historically contingent. This contingency is revealed by both careful philosophical reading and the agency of contemporary artworks. The one universal claim we can make for art is that it is a form of practice. For example, to discuss expression in art effectively, we were forced to broaden this categorisation out from notions of purgation (Aristotle) and self-transformation (Rosenberg) to consider expression on a social basis by addressing how events bring forth change (Deleuze) and how art can take the form of an event. Thus, we might conclude that what we call expression in art is inconstant and bound closely to the diverse specificities of practice.

The weakness of restricted representational, expressive, and formalist theories is the centrality they give to the artist and critic in turn as locus of meaning. Against such theories, we have identified that the origin of art resides as much within modes of social form and social structure. Individual acts of artistic production are part of a series of ongoing chains of signification that spread across general structures of meaning as they manifest at that time. In short, such acts are additive or disruptive. In contrast, institutional theory runs the risk of explaining artistic production, display and reception in a manner that leaves the disruptive charge of the individual work unexplained. Finally, the “aesthetic attitude” has been criticised for suggesting a universalised experience of modern art, outside of national, political, historical, or cultural reference points, disguising the predominantly white, bourgeois, western-centric, patriarchal, and heteronormative character of the artworld’s discourses and power bases. At the same time, the aesthetic act can work against normativity, exposing difference, and heterogeneity, and dissensus within presumed communities of sense (Rancière 2010; Derrida 1987).

From de Man we conclude, to answer the question “What is Art?” we must be attentive to its literal meanings, born out in the specificities of material and context. Moreover, this kind of answer interrogates the disciplinary assumptions that inform the question, a process that ultimately deconstructs the truth claims of philosophy. What is left is a paradoxical interplay of materiality and signification, which allows us to make the limited conclusion that intrinsic functions (representation, form and expression) co-exist with extrinsic determiners (aesthetic attitude and institutionality), challenging assumptions that inform many of the positions (Plato, Fry, Collingwood, Dickie, etc.) we have examined. A philosophy that seeks to reveal art’s essence is blind to the sensuous particularity and heterogeneity of works of art. Insight comes when philosophy analyses these specificities withholding its own assumptions. It might also learn something about itself in the process.

Aristotle. (335 BCE) 1996. Poetics . Translated by Malcolm Heath. London and New York: Penguin.

Bell, Clive. (1914) 2002. “The Aesthetic Hypothesis.” In Art in Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas , edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, 107–110. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barthes, Roland. (1971) 1977. Image, Music, Text . New York: Hill and Wang.

Benjamin, Walter. (1935) 2007. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations , translated by Harry Zohn, 217–52. New York: Schocken.

Bishop, Claire. 2005. Installation Art: A Critical History . London: Tate Publishing.

Blum, Harold P. 1956. “Van Gogh’s Chairs.” American Imago 13, no. 3 (Fall): 307–311, 313–318.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1979) 1996. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste . Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2002. Relational Aesthetics . Dijon: Les Presses Du Reél.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2009. “Altermodern: A Conversation with Nicolas Bourriaud.” Art In America (March 16, 2009). https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/altermodern-a-conversation-with-nicolas-bourriaud-56055/ .

Bullough, Edward. 1912. “‘Psychical Distance’ as a Factor in Art and an Aesthetic Principle.” British Journal of Psychology 5, no. 2: 87–118.

Collingwood, Robin G. (1938) 2013. The Principles of Art. London: Case Press.

Costello, Diarmuid. 2007. “Greenberg’s Kant and the Fate of Aesthetics in Contemporary Art Theory.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 65, no. 2 (Spring): 217–228.

Danto, Arthur. 1964. “The Artworld.” The Journal of Philosophy 61, no. 19 (October 15): 571–584.

Danto, Arthur, and James Liszka. 1997. “Why We Need Fiction: An Interview with Arthur C. Danto.” The Henry James Review 18, no. 3: 213–16.

de Man, Paul. 1982. Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1987. The Truth in Painting . Translated by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, Jacques. (1967) 2001. “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.” In Writing and Difference, 2nd ed, 351–370. London: Routledge.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1996. What is Philosophy? New York: University of Columbia Press.

Dickie, George. 1964. “The Myth of the Aesthetic Attitude.” American Philosophical Quarterly 1: 56–65.

Dickie, George 1974. “What is Art? An Institutional Analysis.” In Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis , 19–52. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Fraser, Andrea. 2005. “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique.” Artforum (September): 100–06.

Fry, Roger. (1909) 2002. “An Essay on Aesthetics.” In Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000, 17–82.

Greenberg, Clement. (1939) 2002. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” In Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000 , 539–549.

Greenberg, Clement. (1960–65) 2002. “Modernist Painting.” In Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000, 773–779.

Greenberg, Clement. 1971. “The Necessity of Formalism.” New Literary History 3, no. 1 (Autumn): 171–175.

Harrison, Charles, and Paul Wood, eds. Art in Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Oxford: Blackwell.

Johnstone, Gary, dir. 1990. J’accuse Vincent Van Gogh . Written by Griselda Pollock. BBC.

Jameson, Fredric. 1991. Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism . London: Verso.

Kant, Immanuel. (1790) 2000. Critique of the Power of Judgment. Translated by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kardaun, Maria S. 2014. “The Philosopher and the Beast: Plato’s Fear of Tragedy.” PsyArt 18: 148–163.

Kivy, Peter. 1997. Philosophies of Arts: An Essay in Differences . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1979. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” In The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths , 151–71. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Krauss, Rosalind. 2000. A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition . London: Thames & Hudson.

Kristeller, Paul Oskar. 1951. “The Modern System of the Arts: A Study in the History of Aesthetics Part I.” Journal of the History of Ideas 12, no. 4 (October): 496–527.

Kosuth, Joseph. [1969] 1991. “Art After Philosophy.” In Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings, 1966–90 . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lubin, Albert J. 1996. Stranger on Earth: A Psychological Biography Of Vincent Van Gogh . New York: Da Capo.

Locke, John. (1689) 1979. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16, no. 3: 6–18.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1896) 2000. “Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense.” In The Continental Aesthetics Reader , ed. Clive Cazeaux, 53–62 . London: Routledge.

O’Doherty, Brian. 1986. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space . Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Osborne, Peter. 2017. The Postconceptual Condition . London: Verso.

Owens, Craig. (1980) 2002. “The Allegorical Impulse.” In Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000 , 1025–1032.

Plato. (380 BCE) 1974. The Republic . Translated by Desmond Lee. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Pollock, Griselda, and Fred Orton. 1978. Vincent Van Gogh: Artist of His Time . Oxford: Phaidon.

Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics . Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London and New York: Continuum.

Rancière, Jacques. (2006) 2011. The Politics of Literature . Translated by Julie Rose. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Rancière, Jacques. 2009a. Aesthetics and its Discontents . Translated by Steven Corcoran. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Rancière, Jacques. 2009b. The Emancipated Spectator . Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso.

Rancière, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics . Translated by Steven Corcoran. London and New York: Continuum.

Read, Herbert. 1961. Education through Art . London: Faber.

Rosenberg, Harold. (1952) 2002. “The American Action Painters.” In Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory 1900–2000 , 589–592.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. (1819) 2011. The World as Will and Representation . Edited by Judith Norman, Alistair Welchman, and Christopher Janaway. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Still, C. “Letter to Dorothy Miller February 5, 1952.” 193. Quoted in Clifford Ross, Abstract Expressionism Creators and Critics: An Anthology , ed. Clifford Ross. New York: Abrams Publishers.

Stolnitz, Jerome. 1960. Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art Criticism . Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press.

Tolstoy, Leo. (1896) 1995. What is Art? London: Penguin.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1953) 2009. Philosophical Investigations . Translated by P.M.S. Hacker and Joachim Schulte. 4th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Further Reading

Brunette, Peter, and David Wills, eds. 1994. Deconstruction and the Visual Arts . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cazeaux, Clive, ed. 2000. The Continental Aesthetics Reader. London: Routledge.

Foster, Hal, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H.D Buchloh. 2004. Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism and Postmodernism . London: Thames & Hudson.

Kivy, Peter. 1997. Philosophies of Arts: An Essay in Differences . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 55–83.

Rancière, Jacques. 2009. The Emancipated Spectator . Translated by Gregory Elliott. London: Verso, 1–24.

Stallabrass, Julian. 2006. Contemporary Art: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Warr, Tracey and Amelia Jones. 2000. The Artist’s Body . London: Phaidon.

- Here, Socrates rejects the claim that poets, or artists in general, are suitable teachers for the young citizens of the republic. Throughout Book X, he argues that artistic representations are unreliable. Painters of shoes know less about ideal Forms than shoemakers, who at least have applied knowledge. A painter of a bridle knows less about its truth than the bridle maker, and certainly less than the horseman who has practical knowledge of its use. Socrates establishes a hierarchy of knowledge gained through use, manufacture, and representation, arranged according to their distance from the truth of the Forms. Because artists create subjective copies of things which are already copies of universal Forms, “representative art is an inferior child of inferior parents” (603b). Stripped of their poetic colour, these arts contain little rational substance (601b). In contradistinction, only philosophers know the truth of the Forms in themselves. Because of their unreliability, and their potential corrupting capacity to engendered emotional rather than rational responses in their audiences, it is concluded that the representative arts should be strictly censored, if not banished, within the ideal republic. ↵

- The famous “death of the author” thesis is generally accepted to begin from the essay by Roland Barthes ([1971] 1977, 142–9) of the same name, though countless cultural theorists and philosophers have contributed to the debate. In his essay, Barthes argues that the meaning of a literary work is produced at the point of its reception, by an active reader situated within a dynamic social context, rather than at the point of its production, where its meaning is fixed by a unique authorial intention. A precursor to this theory can be found in Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” ([1935] 2007). Here, Benjamin claims that new media technologies exponentially increase the audiences and contexts for reception of art, invalidating the authority of any singular claim over the meaning of specific artworks. Feminist film theory, such as the work of Laura Mulvey (1975), theorised the specificity and difference of the female spectator in and against the patriarchal ideology produced and reproduced by Hollywood cinema. Building upon this, Rancière’s The Emancipated Spectator (2009b) argues that the presumptions of hegemonic models of theatrical performance and artistic display render their audiences physically, and by extension intellectually and politically, passive. In contradistinction, the promiscuity of the modern novel, which is recontextualised endlessly by mass culture, perpetually meeting new readers who invent new readings in turn, contains what he regards as The Politics of Literature ([2006] 2011). Plato recognises the same anarchic potential of writing, albeit as a negative rather than emancipatory quality, in his dialogue The Phaedrus . ↵

- For example, when we gaze up into the blueness of the sky and contemplate its beauty it seems beside the point for us to identify it as "the sky." Even a tacit awareness of what we are looking into is superseded in the moment of contemplation by the experience of beauty. This is structurally consistent with Kant’s argument. The faculties (imagination and understanding) that would otherwise identify the blue field apprehended as the sky are in a state of free play. No concept is deployed because there is no synthesis of the apprehension into a determinate judgment. A different order of aesthetic judgment is operative. ↵

- It is perhaps worth pointing out that Danto remained committed to the professional distinction between “analytic” and “continental” philosophy that this chapter has tried to sidestep. See Danto and Liska (1997), where he dismisses the pretentiousness of continental thought, especially Derrida’s. Presumably, despite the possible compatibility of the concepts of “Artworld” and “parergon,” Danto would probably never have countenanced such a comparison. ↵

What is a Work of Art? Copyright © 2021 by Richard Hudson-Miles and Andrew Broadey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Works of Art Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Basic facts about the works, personal philosophies of artists, artwork in time-context, comparison: form, content, and subject matter, aesthetic qualities and symbolic significance.

Pieces of artwork from different time periods portray varying styles. Several time periods had distinctive schools of thought. As a result, an artist who created a piece of work revealed a certain philosophical point of view. Aspects like positioning of key figures in an artwork tell of a particular style used to construct an image. Personal philosophies of artists rely upon the prevailing conditions of the time. It is imperative that the viewer makes some identities such as the visual appearance of the work.

Therefore, many works of art belonging to the same period are closely related to the context of the period. This essay has two main parts. The first part highlights more about the impressionism period’s paintings, basic facts about the works, the personal philosophies of the artists, and art work in time context. On the other hand, the second part compares the forms of art with respect to content, subject matter and form. It also compares and contrasts the symbolic significance, aesthetic attributes and the different perspectives from the artists.

The period chosen is Impressionism. Despite the differences in the paintings to be compared, all have got one description in common. Historically, impressionism as an art period dates back to 1874. These artworks have a unique way from their ability to create brilliant and rosy images. Usually, paintings from the impressionism depicted nature. Light and shadows are blended to create softened outlines. The viewer gets an impression of the sun illuminating the canvas (Perry, 1997, p. 11).

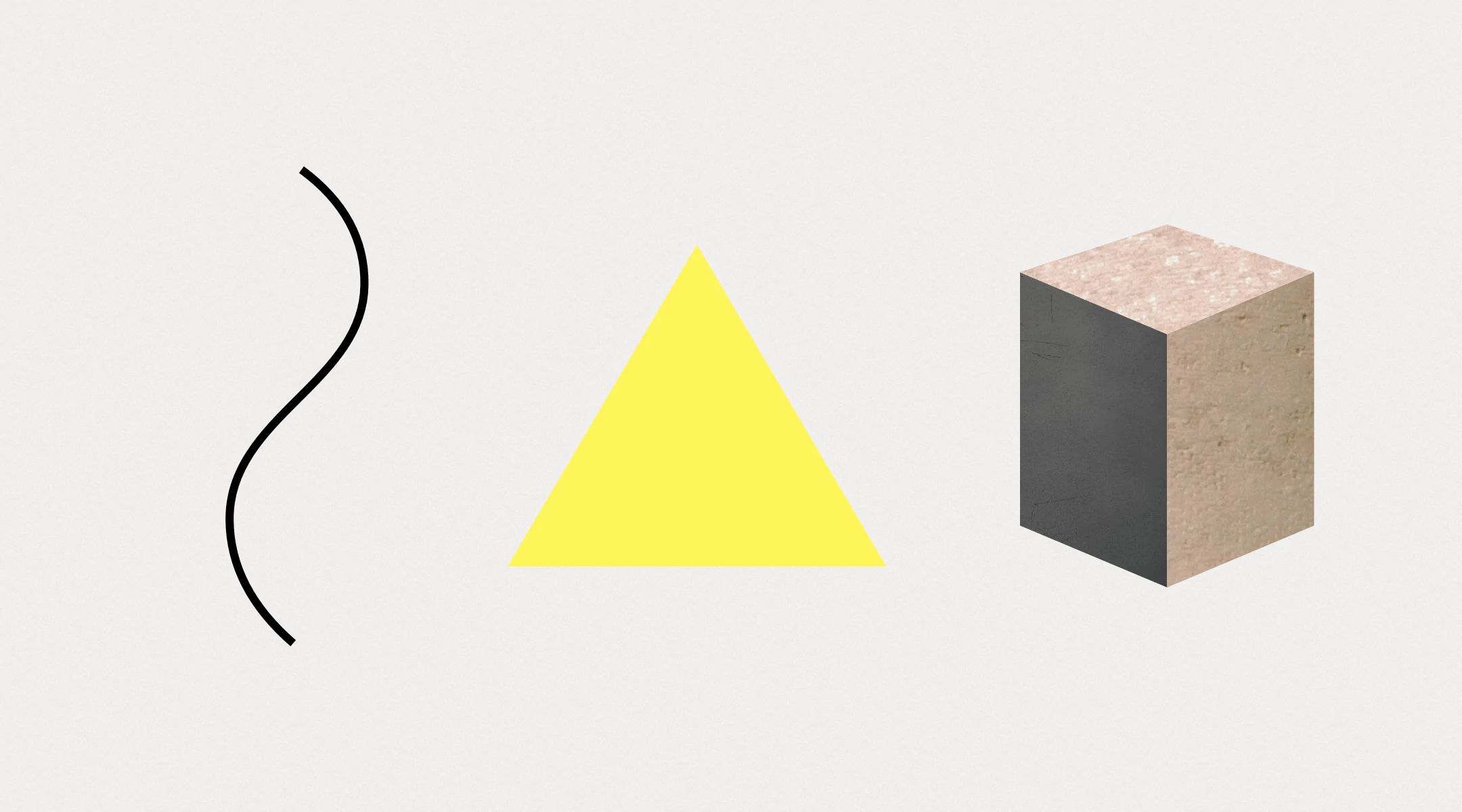

The works belong to an impressionism period. The three paintings chosen for comparison are the works of Cassatt Mary, Renoir Pierre-Aguste and Signac Paul. In all paintings, the theme involves people in a house setting. At a glance, the paintings do not have many details except the subjects in their setting.

The positioning of main figures in the frames is a point that draws interest. In the works below, the figures assume a central location in the frame. In addition, the figures in the pictures are presented in bold colors. The bold colors are blended well with shadows to create an outstanding brilliance.

The above paintings are, from left to right, Mary Cassatt’s 1880 painting, Renoir Pierre-Auguste’s 1864 painting, and Signac Paul’s 1885 painting. The first two paintings have their main figures positioned in the foreground. The last painting has the main figures in the middle ground of the frame.

However, a viewer of the painting cannot miss to note the inclusion of purple colors in all paintings. Therefore, the usage of bold colors that present a shimmering effect, and softened outlines of images is evidence that these paintings belong to the impressionism style of painting. Consequently, Mary Cassatt, Renoir Pierre-Aguste, and Signac Paul were impressionists.

Mary Cassatt’s paintings, during the impressionism period, often depicted family life. In the first place, she painted ladies in their homes. For instance, the painting above is entitled, Lydia crocheting in the Garden at Marley . At that time, her male compatriots in the art painting were working on landscapes.

The impressionism movement was the school of thought in the painting world that Mary lived in. The greatest influence for in-home paintings was females in her time were not allowed to walk alone unattended. This piece of work was done when her sister was ill. There is vibrancy in the painting.

However, the face of Lydia is sad. Therefore, Mary must have been sad too; her sister was ill at the time. One should note that the painting was made in France at that time. Women’s place in society was confined to the homesteads. This influenced the setting of her paintings (Swain, 2011, p 20).

Renoir’s painting above is entitled Little Miss Romaine Lacaux . This oil on canvas paint was done in 1864. The painting was also influenced by the impressionism school of thought. This painting is one among many others depicting children. He held a philosophy of living and working. The main influence for this painting was the closure of the Gleyre Studio in 1864 (Klein & Monet, 2006, p 11). Another influence was his affection for children. His age at that time might have influenced this affection.

Paul Signac had a wealthy background. His painting career was initially influenced by his friendship with other artists like Monet. Signac was both an anarchist and libertarian. The painting illustrated above was created in 1885; the year Signac was in constant resistance from bourgeois (Walther & Suckale, 2002, p 508).

Generally, Signac was influenced by impressionist paintings of artists like Monet and Seurat. Two milliners, Rue du Caire portray the widely held idea in the 19 th century that a woman’s work was indoors. Thus, this picture reveals a disorganized environment in which a woman conducts her daily chores.

The three artworks belong to different artists but same time period. The works are further distinguished from one another through philosophies that an artist held then. In this example, the school of thought was impressionism. As a result, each artist combined artistic requirements of impressionism with prevailing situations. This combination was represented as a pictorial idea of the artist about some subject. Therefore, the school of thought, at that time influenced an artwork.

In the first painting made by Mary Cassatt, the blend of colors offsets the dull mood of the picture’s face. The image is generally flat. Nevertheless, the brown color scaling the perspective in the middle ground of the frame adds some form and texture picture. The large bonnet worn by the lady suggests the painters’ internal feeling of hiding a sad mood in the face of the picture.

In the second painting, Renoir combines the effect of shadows and light to offset the flat upper part of the girl with form. The circular shape of the cloth in the lower waistline of the picture introduces motion and transition in colors. Colors begin with dullness and brighten upwards. This color transition introduces innocence in the child; the subject matter.

Lastly, Signac’s milliner is based on flatness. The brushstrokes applied to the tablecloth combines with the wallpaper to introduce parallelism, in the picture. However, flatness of the picture is reduced by the bending figure. Form is introduced in the picture, around the back of the milliner. This underscores the painter’s subject matter; domestic chores of a woman, that time.

The painting of Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marley has an awkward aesthetic value. The large bonnet on her head does not match with either her thin body or sad face. Unlike the other two paintings, Mary Cassatt symbolically expressed her sadness through this quality.

There is a quality of elegance in Little miss Romaine by Renoir. The elegance is enhanced by usage of bright colors around the face of the girl. This symbolically depicts innocence in children. Lastly, the aesthetic quality in the Two Milliners is powerful. The bending woman in the picture symbolically represents burden. Despite the differences, all paintings embrace the use of bold and bright colors to present their subject matter.

In conclusion, impressionism employed the use of bold and bright colors in most of the paintings. The most preferred color was purple. The paintings comprised majorly of outdoor scenes like landscapes. Through such artworks, an artist’s subject matter is evident. Therefore, impressionists usually painted according to the prevailing situations at the time.

Klein, AG. & Monet, C. (2006). Claude Monet . Minnesota: ABDO Publishing Company.

Olga’s Gallery (2011). Web.

Perry, G. (1997). Impressionist Palette: quilt color and design . California: C&T Publishing Inc.

Swain, C. (2011). Claude Monet, Edward Degas, Mary Cassatt, Vincent Van Vogh . London: Benchmark Education Company.

Walther, IF. & Suckale, R. (2002). Masterpieces of Western Art : A History of Art in 900 individual studies from the Gothic to the present day, part 1. Bonn: Taschen.

- Oil Paintings by Renoir, Maler, de Corter

- Women Writers and Artists About Social Problems

- An analysis of the Luncheon of the boating party

- Art through History

- Art Period Comparison: Classicism and Middle Age

- Art Transformation Since the Middle Ages to the Current Times

- Art influences Culture: Romanticism & Realism

- Necklace of Five Gold Pendants and Twenty One Stone Beads

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)