“The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David – In-Depth Analysis

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David has stood the tests of revolutions and vanishment, but it has always managed to make a statement. This article will explore this political history painting in more detail.

Table of Contents

- 1 Artist Abstract: Who Was Jacques-Louis David?

- 2.1 Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

- 3.1 Subject Matter: Visual Description

- 3.2 Texture

- 3.6 Shape and Form

- 4 A Revolutionary Duo

- 5.1 Who Painted The Death of Marat?

- 5.2 Where Is The Death of Marat Painting Now?

- 5.3 What Is the Meaning of The Death of Marat Painting?

Artist Abstract: Who Was Jacques-Louis David?

Jacques-Louis David was a French Neoclassical painter; his date of birth was August 30, 1748, and he died December 29, 1825. He was born in Paris, France, and started painting at an early age. He won the Prix de Rome in 1774, allowing him to study in Italy, which also exposed him to great classical artists. He studied at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, where he initially started his art studies at the age of 18. His art style was characterized by historical and classical subject matter, but he also had a political side and painted for Napoleon Bonaparte. Some of his famous artworks include The Oath of the Horatii (1784), The Death of Socrates (1787), and Napoleon at the Saint Bernard Pass (1801).

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David in Context

The article below will explore The Death of Marat analysis, first discussing a contextual overview in terms of why Jacques-Louis David painted it, which will be followed by a formal analysis looking at the subject matter and stylistic elements.

| Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) | |

| 1793 | |

| Oil on canvas | |

| History painting | |

| Neoclassicism | |

| 162 x 128 | |

| N/A | |

| Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium | |

| Uncertain |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

For a better comprehension of the painting The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David it is important to have a sense of what occurred in French history when David painted it in 1793, as well as the artist’s own political preoccupations that inspired him to paint it.

It’s believed that Jacques-Louis David painted The Death of Marat as a “tribute” to the murdered political figure of Jean-Paul Marat, who was also a journalist and writer. He was pro-revolutionary and affiliated with the Jacobins, who was a prominent political “club”. Similarly, Jacques-Louis David was also a pro-revolutionary and part of the Jacobins.

Marat reportedly had a skin condition and he needed to frequently be in the water, which eased his discomfort. This ties in with his murderer, Charlotte Corday, who was part of the Girondins group, who were against the Jacobins. She gained access to meet with Marat, although there is debate around the details of why she met with him, and she stabbed him while he was in the bath. David’s intent for The Death of Marat painting was as a propagandist tool, and he utilized various iconographical tools common to religious paintings.

Some of these include the position of Marat’s body, limp and lifeless, like Jesus Christ’s body after he was crucified, and the wound on his upper chest, like the wounds Jesus Christ had known as the stigmata.

Other examples include the wooden crate, which has been likened to a stele, and the bath, which has been compared to a tomb, as well as the light coming from an unknown source to the left, which creates an air of seeming holiness shining on the dead Marat. These and more all point to how David portrayed Marat in light of the political upheavals of the time.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

The Death of Marat analysis continues below with a visual description of the subject matter and how the following art elements like color , texture, line, shape, form, and space were applied and utilized by Jacques-Louis David.

Subject Matter: Visual Description

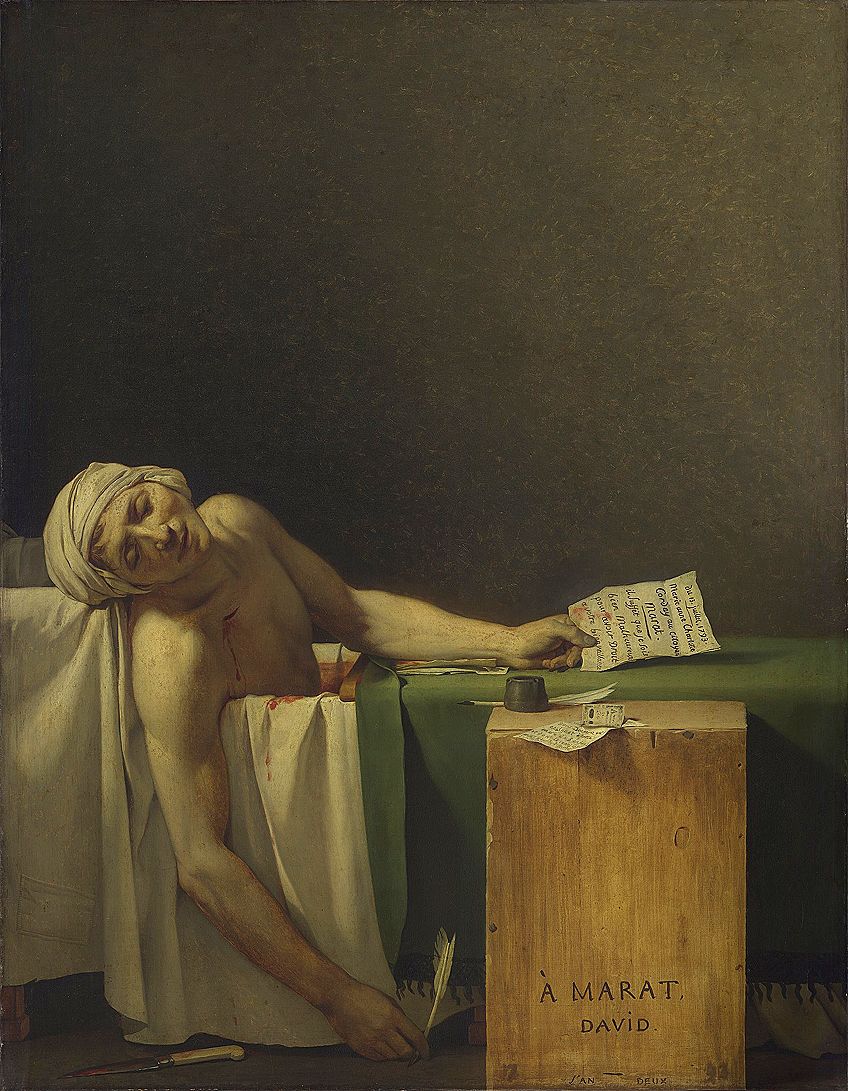

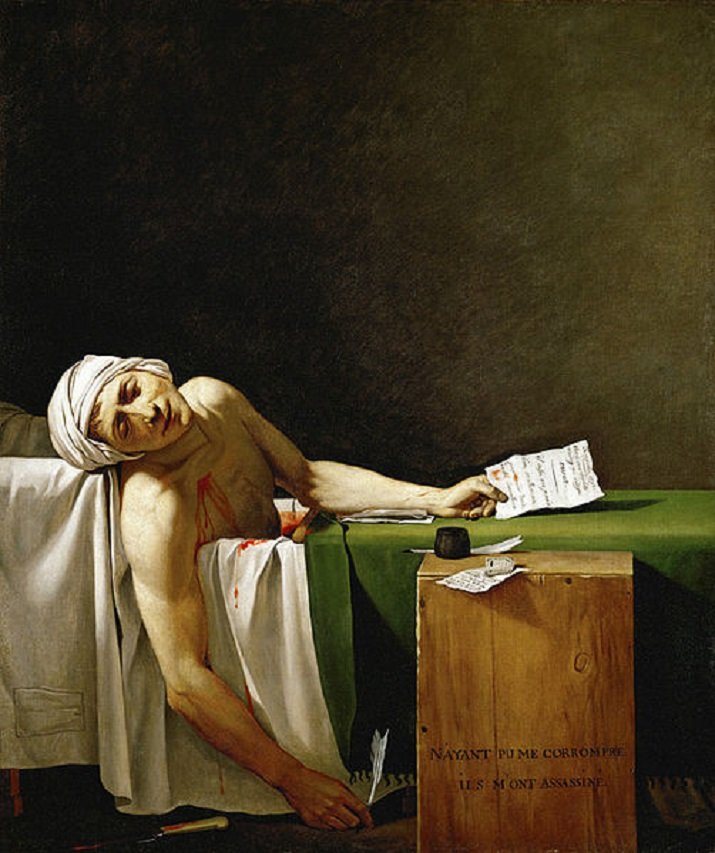

The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David depicts the lifeless body of Jean-Paul Marat lying in his bath; his upper body is slightly slouched over the bath’s edge, his head, which is topped with a white turban, is limp and resting against a piece of furniture behind the bath to the right, and his right arm is hanging over the bath’s edge; his lifeless fingers are touching the floor.

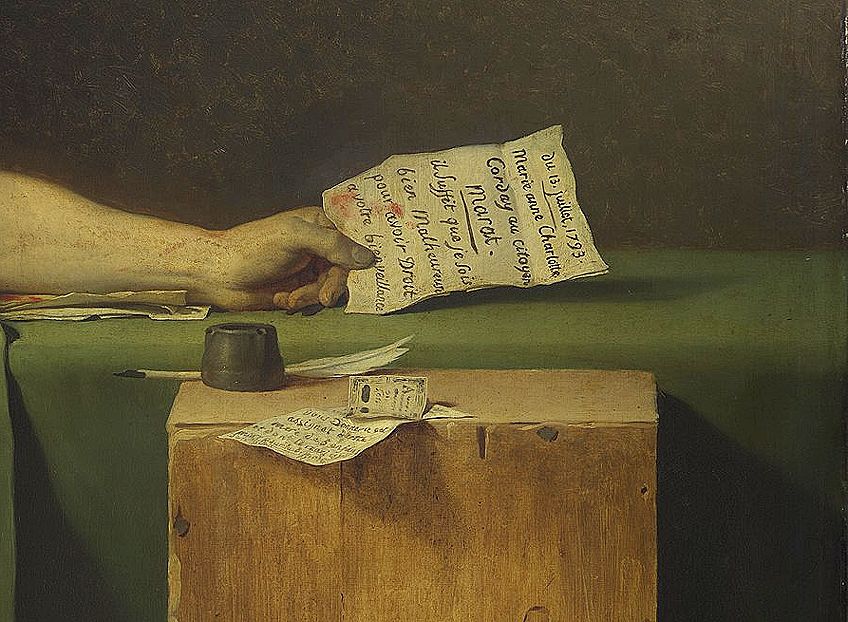

In his left hand, he is holding a piece of paper, the letter from his murderer who was Charlotte Corday, and his left is on a wooden slab that appears to be over the bath allowing him to write on it. In his right hand, which is touching the floor, is a quill, and to the left of it is a knife with blood on the blade and handle; a stab wound is visible on Marat’s upper right chest area.

Slightly further to the right and next to the bath is a wooden block or crate acting as a table with a quill and ink bottle with several papers on it. On the crate are inscribed the words, “À MARAT, DAVID” and right at the bottom it reads, “L’AN DEUX”, which reportedly translates to “Year Two”. The bath itself is covered over by a green cloth or throw, and red bloodied water is visible in it near Marat’s upper body.

There are numerous implied textures that Jacques-Louis David created through his brushwork, which also create contrasting effects, for example, the smoother surface of the cloth and material as well as Marat’s pallid skin tone compared with the rougher wooden surface of the crate next to the bath.

The color scheme in The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David consists mostly of neutral hues like the whites of the turban, cloth, paper, and quills, the green of the cloth over the bath, the brown from the wooden crate, and flesh tone of Marat’s skin.

David utilized the shading to create the effects of light, for example, the light source to the left gently illuminates Marat’s dead body, providing more emphasis on him as the main protagonist of the scene. Furthermore, it also sheds light on the objects that give us, the viewers, more details about the scene, for example, the letter in Marat’s left hand and his face, which appears seemingly serene.

There are also areas of shadows in the background and foreground, notably where the knife lies on the floor.

There are a variety of implied lines created by the subject matter leading us (the viewers) to gaze around the composition, with a specific focus on Marat and the knife on the floor. For example, the vertical lines from the folds of the white and green cloth near Marat’s hanging arm, the latter also create a vertical line. However, there is also a diagonal and curved line created, which is emphasized by the quill in Marat’s hand, its tip just touching the floor and seemingly creating an implied directional line towards the knife to the left.

Space in The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David is composed of the main subject matter in the foreground, more specifically in what is called the “shallow” foreground. The background is neutral and in a dark hue, which creates a backdrop effect for the figure in the foreground.

The space has also been described as if David set it as a stage, intentionally placing all the objects where they need to be to address the narrative of the scene and more importantly Marat’s figure.

Shape and Form

Jacques-Louis David created a naturalistic composition in terms of form, in other words, the figure of Marat is depicted in a realistic manner and muscularly defined, as was also characteristic of Neoclassical paintings of the time, however, Marat’s form was also “idealized” by the artist and placed in a position of that of a martyr, likened to the martyrdom of Jesus Christ.

A Revolutionary Duo

This article discussed the oil on canvas The Death of Marat by one of the most renowned Neoclassical artists Jacques-Louis David. This was not only a homage to the political figure of Marat but also a visual, politically prone, portrayal of him. Furthermore, the article also discussed some of the primary stylistic approaches and iconography that David utilized to create a gentle, yet impassioned display of Marat’s death.

“The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David has been an emblem of inspiration since its unveiling in 1793, including inspiring many to make copies of it for political purposes. But the painting was also lost for some time and was unveiled yet again, reportedly almost two decades after the artist’s death, this time inspiring poets and artists like Charles Baudelaire, Pablo Picasso, and Edvard Munch , including numerous references in 21st-century pop culture by artists like Brazilian artist Vik Muniz. It is safe to say that David and Marat have been a revolutionary duo since 1793, and even in death, they continue to master their trade and message of suffering, liberty, and ultimately immortalizing Marat’s honor.

A look at The Death of Marat painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who painted the death of marat .

The Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David created the famous history oil painting titled The Death of Marat (1793). It is a portrayal of Jean-Paul Marat lying dead in his bath after Charlotte Corday killed him.

Where Is The Death of Marat Painting Now?

The oil on canvas painting The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David is housed at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, which is located in Brussels, Belgium.

What Is the Meaning of The Death of Marat Painting?

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David was painted in a manner to show the Jacobin Jean-Paul Marat as a so-called martyr, notably of the French Revolution . He was assassinated by Charlotte Corday, who was part of the opposite political group the Girondins.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David – In-Depth Analysis.” Art in Context. February 17, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-marat-by-jacques-louis-david/

du Plessis, A. (2023, 17 February). “The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David – In-Depth Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-marat-by-jacques-louis-david/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Death of Marat” by Jacques-Louis David – In-Depth Analysis.” Art in Context , February 17, 2023. https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-marat-by-jacques-louis-david/ .

Similar Posts

“Le Rêve” by Pablo Picasso – The Dream Painting Analysis

“The Eiffel Tower” by Georges Seurat – Strokes of Brilliance

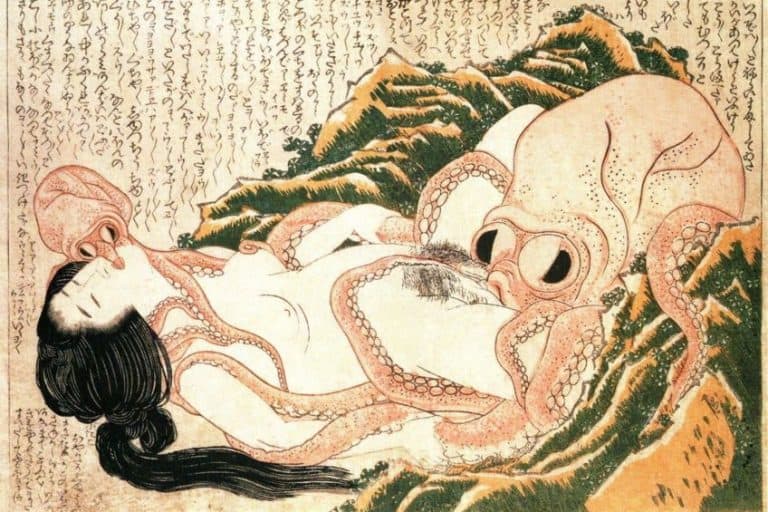

“The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” by Hokusai – An Analysis

“Queen Charlotte” Painting by Allan Ramsay – Fit for Royalty

“The Old Guitarist” Picasso – Analyzing Picasso’s Guitar Painting

“Irises” by Vincent van Gogh – Studying the Famed “Irises” Painting

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Most Famous Artists and Artworks

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors…in all of history!

MOST FAMOUS ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS

Discover the most famous artists, paintings, sculptors!

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Europe 1300 - 1800

Course: europe 1300 - 1800 > unit 10.

- Neoclassicism, an introduction

- David, Oath of the Horatii

- David's Oath of the Horatii Quiz

- Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Socrates

- David, The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons

- David, Study for The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of his Sons

- Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat

David and The Death of Marat

- David, The Intervention of the Sabine Women

- David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps

- Kauffmann, Cornelia Presenting Her Children as Her Treasures

- Girodet, The Sleep of Endymion

- Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine

- Canova, Repentant Magdalene

- Canova, Paolina Borghese as Venus Victorius

- Vignon, Church of La Madeleine

- Soufflot, The Panthéon, Paris

- David, The Emperor Napoleon in his Study at the Tuileries

- J. Schul, Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom

- Neoclassicism

David and the Jacobins

Marat and christ, david and napoleon, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Assassination of Marat

The assassination of revolutionary activist and Jacobin leader Jean- Paul Marat on 13 July 1793 was one of the most iconic moments of the French Revolution (1789-1799), immortalized in Jacques-Louis David's painting Death of Marat . Marat's killer, Charlotte Corday , believed that the only way to save the Revolution and prevent the excesses of the Reign of Terror was through his death.

The murder failed to prevent the Terror, instead giving the Jacobins a martyr who they could use to advance their agenda. Following her execution four days after the assassination, Corday also became a symbolic figure for those who resisted the Jacobin regime. In the decades since the event, it has become mythicized through the various poetry, art, and literature made about it.

The Pariah: Jean-Paul Marat

On the topic of Marat, historian Mona Ozouf makes an interesting observation: "The historiography of the French Revolution has had its Dantonists. It always has Robespierrists. But it has few Maratists" (Furet et al, 244). Truly, even amongst the colorful cast of characters found in the French Revolution, Marat stands out as unique, an outcast in death as he was in life. Short in stature, Marat was ugly and extravagant, a former physician who had failed to break into the social circles of aristocratic society, turning instead to a life of provocation, encouraging the most extreme excesses during the course of his revolutionary career. He has been described as a "streetcorner Caligula " by Chateaubriand, and a "functionary of ruin" by Victor Hugo ( ibid ). To his supporters, he was always a patriotic visionary, a true friend of the people. To his detractors, he was a pestilence, leaving murder and destruction in his wake.

This heavily divisive man was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on 24 May 1743. He came to France to pursue a career as a physician, writing papers on scientific and philosophical topics. As early as the 1770s, he was making attacks against the aristocracy; in his earliest political work, the 1774 Chains of Slavery , he wrote of a supposed aristocratic plot against the people, something that would become a running theme throughout his work. Ozouf reiterates the idea that Marat's later violence came about in this phase of his life when his intellectual ambitions were thwarted again and again. When the Revolution began, Ozouf states, it offered him "an unprecedented promise: the ability to avenge slights received or imagined and thereby avenge humanity" (Furet et al, 246).

Marat was hardly the only one who felt downtrodden by French society in the years leading up to Revolution. It was from this large crowd of poor, hungry, marginalized people that he drew his audience. Publishing the first issue of his famous newspaper, L'Ami du Peuple ("Friend of the people") in September 1789, Marat quickly became renowned for his colorful, inflammatory remarks and fiery attacks on public officials; at one point in 1790, his attacks against chief royal minister Jacques Necker became so virulent that a warrant went out for his arrest, forcing him to go into hiding.

It is difficult to quantify the exact impact Marat had on the Revolution, seeing as he rarely took active participation in events, preferring instead to write about them before or after their occurrences. Certainly, he took pleasure in unmasking the Revolution's enemies, priding himself on his predictions of Lafayette 's treason or Mirabeau 's corruption. He also advocated for political violence as a means to an end, famously stating that "six hundred well-chosen heads" would deliver liberty to France. He often spoke of the need to purge certain individuals for the greater good and would routinely call for violence against "counter-revolutionary" figures.

Eventually, as his newspaper expanded in popularity, Marat's influence could be found at the heart of several of the Revolution's bloodiest moments. These included the Storming of the Tuileries Palace , which overthrew the monarchy, and the September Massacres , in which between 1,100 and 1,400 clergymen and political prisoners were butchered by Parisian mobs. He had called for all good patriots to go to the prison of Abbaye, take the priests and Swiss Guards imprisoned there, and "run a sword through them" (Schama, 630).

By late 1792, Marat was popular enough to win a seat in the National Convention, and a few months later he served as president of the Jacobin Club. In April 1793, he was arrested by the Jacobins' rivals, the moderate Girondin faction, who hoped to use him as an example to their enemies. Marat was charged with inciting violence and put on trial on 24 April. Unexpectedly, large crowds came to support him as Marat eloquently defended himself by claiming the statements used against him had been taken out of context.

He was acquitted, a rarity for those placed before the Revolutionary Tribunal, to the delight of the cheering crowd, who hoisted him upon their shoulders and placed a crown of laurel on his head. Marat would not have to wait long to have his revenge. A little over a month after his trial, he was instrumental in inciting the insurrections that led to the fall of the Girondins on 2 June. By the summer of 1793, it seemed Marat was at the height of his influence, an outcast no longer, with no one left to stand in his way, except a provincial young woman from Normandy.

The Assassin: Charlotte Corday

Charlotte Corday was born in Saint-Saturnin, Normandy on 27 July 1768. At 13 years old, she was sent to live in a convent in Caen following the death of her mother. There, she would become enraptured by the works of philosophers of the French Enlightenment such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire . By the start of the Revolution, she was an avowed republican, despite the aristocratic background of her family.

By 1793, Corday found herself disgusted by the direction the Revolution was heading. News of the September Massacres had particularly horrified her, and political violence had found its way to her hometown of Caen; in April, Abbé Gombault, the refractory priest who had given last rites to Corday's dying mother, was the first to be guillotined in Caen. Corday, who lived a short stroll away from the local Girondin headquarters, came to blame the violence on the Jacobins, who had long encouraged the Parisian mobs in their insurrections. She would have been further influenced by the militant atmosphere in Normandy, which was preparing to rebel against the Jacobin regime, the way other cities recently had in the Federalist Revolts . The Girondist pamphlets circulating Caen were equally as inflammatory as those of the Jacobins, which may have helped Corday choose her target. One such pamphlet read:

Let Marat's head fall and the Republic is saved…Purge France of this man of blood…Marat sees Public Safety only in a river of blood; well then, his own must flow, for his head must fall to save two hundred thousand others (Schama, 730).

Using logic eerily similar to Marat's own, Corday came to the conclusion that Marat had to die so the Republic could live. On 9 July, she left Caen for Paris , arriving two days later. On the morning of 13 July, she visited the gardens of the Palais-Royal and purchased a kitchen knife with a wooden handle and a five-inch blade. Slipping it beneath her dress, she made her way to Marat's apartments on the rue des Cordeliers.

Corday had hoped to kill Marat in full view of the National Convention to maximize the impact of her message, but shortly before her arrival in Paris, Marat suffered the resurgence of a nasty skin condition that had been intermittently bothering him for two years. Confined to soaking in his bathtub, Marat was visited by the painter and Jacobin supporter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) the day before his death. David found his friend in good spirits and hard at work, using a plank laid across his tub as a writing desk. The bathroom was adorned with maps of the Republic and revolutionary slogans. When David wished Marat a speedy recovery, the sick man laughed. "Ten years more or less in the duration of my life do not concern me," he said. "My only desire is to be able to say with my last breath 'I am happy the fatherland is saved'" (Schama, 731).

At 11.30 the following morning, Charlotte Corday arrived at the doorstep of Marat's apartment, requesting a visit with the famous Friend of the People. She was met by Catherine Evrard, sister of Marat's fiancée Simonne, who refused her entry, claiming Marat was too sick to receive any visitors. Corday gave Catherine a letter about a supposed Girondist conspiracy in Caen before taking her leave. She returned at seven in the evening, sneaking into the apartment as a delivery of fresh bread was being made. This time, she was stopped on the stairs by Simonne herself. Suspicious of this stranger's determination to see Marat, Simonne attempted to turn her away again. As they argued, Corday deliberately raised her voice so that Marat could hear in the next room, claiming she wished to give him information about traitors in Normandy. Before Simonne could push her back down the stairs, a voice sounded from the bathroom: "Let her in."

Reluctantly, Simonne led Corday into the room where Marat was soaking in his bath, a wet cloth tied about his brow. He invited Corday to take a seat by his tub while Simonne waited at the corner of the room, keeping a close eye on the visitor. For 15 minutes, they talked about the political situation in Caen before Marat sent Simonne out of the room to fetch him a fresh solution for his bathwater. Once she was gone, Marat asked Corday for a complete list of the conspirators. According to Corday, once she had listed the names, Marat had said, "Good. In a few days I will have them all guillotined" (Schama, 736).

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

That was when the assassin struck. Reaching into her dress, Corday produced the kitchen knife which she plunged into Marat's right side, just below the clavicle. He screamed in pain, shouting, "Help me, my beloved!" By the time Simonne rushed back into the room she found Marat floating in a tub of reddened water, and the girl standing beside him. Simonne screamed, "My God , he has been assassinated!", and turned to Corday, "what have you done?" (Schama, 737).

Marat's dying scream was heard by his neighbors who now rushed in to help. One man, Laurent Bas, who distributed Marat's newspaper, hurled a chair at Corday before tackling her and pinning her to the ground. Two of the neighbors, a dentist and a surgeon, lifted the body from the tub to try and staunch the bleeding. But it was too late. The Friend of the People was already dead.

News of the attack traveled quickly, and within the hour a large crowd had gathered outside Marat's apartments. Six deputies from the National Convention arrived to interrogate Corday, who had made no attempts to escape or resist arrest. She answered every question put before her, claiming she had come to Paris with the sole intention of killing Marat, and that she had done so of her own volition, aided and abetted by no outside parties.

The Jacobin leadership, convinced of a grand Girondist plot, had Corday cross-examined by the Revolutionary Tribunal three times over the next four days. Each time, Corday proudly insisted she had acted alone. When asked why she had killed Marat, Corday answered, "I knew that he was perverting France. I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand... I was a republican well before the Revolution, and I have never lacked for energy" (Andress, 189). She remained unrepentant, believing she had done France a patriotic service. On 17 July, Corday was executed by guillotine, only ten days before her 25th birthday.

Two Martyrs

The assassination of Marat would hold significance for both sides of the revolutionary divide. For some, it was the deliverance of justice, a vile creature aspiring to dictatorship struck down by the virtuous hand of a youthful maiden. For others, it was a tragedy, the friend of the people slain in his own bathtub by a traitorous aristocrat. In time, both Marat and Corday would achieve the status of martyrs, one for the Jacobins, the other for those who resisted them. A far cry from Corday's desire to lessen the bloodshed and diminish Jacobin influence, her act only served to deepen divisions in the months preceding Jacobin supremacy and the Reign of Terror.

Marat's martyrdom took place almost immediately. In the weeks leading up to his assassination, his fellow Jacobin leaders had become mistrustful of him, nervous that he would turn his populist rhetoric against them. Now, they took steps to maximize their political gains from his death. The funeral ceremonies were organized by the esteemed painter David, who paid 7,500 livres for the best embalmer in Paris to prepare Marat's body. It was a demanding order; the fatal wound had to be emphasized to show the suffering of Marat, while his disfiguring skin condition had to be covered up. In the end, it hardly mattered. The stifling summer heat caused the corpse to stink so bad that they were forced to hold the funeral days early, meaning most of France's prominent officials were unable to attend.

However, this unfortunate funeral did not stop an almost cultlike reverence to surround the murdered Marat. His heart was removed and placed in an urn that hung above the radical Cordeliers Club. At the ceremony commemorating this, a eulogy was given by the Marquis de Sade, which demonstrated the increasingly anti-Christian nature of the Revolution by comparing Marat to Jesus Christ :

O heart of Jesus , O heart of Marat…their Jesus was but a false prophet, but Marat is a god. Long live the heart of Marat…Like Jesus, Marat detested nobles, priests, the rich, the scoundrels. Like Jesus, he led a poor and frugal life… (Schama, 744).

Popular songs were written in the name of the 'patriot Marat', as his bust replaced a statue of the Virgin Mary on the rue aux Ours. For a time, the port city of Le Havre even changed its name to Le Havre-de-Marat, and when the Jacobins eventually established their own Cult of the Supreme Being to replace Christianity, Marat was made a quasi-saint. His remains were interred in the French Panthéon in 1794, and the Jacobins used his martyrdom to push through their own agenda. As historian Simon Schama points out, the unpredictable, chaotic Marat was more use to them in death than in life.

The downfall of the Jacobins and the Thermidorian Reaction , however, ended this deification of Marat. In 1795, his busts were smashed in the streets, and his coffin was removed from the Panthéon. While Marat would enjoy a brief resurgence of post-mortem popularity in the early years of the Soviet Union, he had truly become an outcast once again.

Charlotte Corday would also become a martyr, for the opposite side. She became a symbol of resistance to the Jacobins; the green headdress she wore on the day of the murder would help make green the color of counter-revolution throughout France. Although many feminists at the time reviled her for her actions and for potentially causing the executions of leading revolutionary women like Madame Roland, Corday played an important role in the conversation surrounding women in the French Revolution. By committing her act alone, without the coercing of a man, she proved that women were capable of self-autonomy and of committing political acts. She became romanticized in paintings, poems, and literature. In 1847, writer Alphonse de Lamartine even assigned her the nickname 'Angel of Assassination'.

In Art & Popular Culture

Both Marat and Corday sought to achieve revolutionary ideals through acts of violence. Both of them became heroes and martyrs for their respective ideologies. And both continue to survive to this day, in the form of art. As part of the Jacobin propaganda machine, Jacques-Louis David made a painting of his fallen friend that would become one of the most famous works of art to come out of the Revolution. In it, Marat lies dead in his bathtub, his features beautified and his expression peaceful. It is widely considered to be David's masterpiece and is often reproduced for its historical and cultural significance. Corday, too, was painted, by the National Guard officer Jean-Jacques Hauer in the last hours of her life. Behind the innocence of Hauer's Corday is a certain unapologetic determination, the face of one who believed herself to be a patriot.

Aside from countless other paintings, Marat and Corday have both been featured in novels and poems throughout the centuries. Marat features in Victor Hugo's novel Ninety-Three, while Corday is briefly referenced in another of his famous works, Les Miserables . Numerous plays and operas have been made about the assassination, including the relatively recent Charlotte Corday written by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero in 1989 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Revolution. References to the assassination have even made their way into video games; in the popular 2014 game Assassin's Creed: Unity , the player must solve the mystery of Marat's murder, which results in the capture and confession of Charlotte Corday. Clearly, Marat's assassination has had a major impact on cultural history just as much as it did on the course of the Revolution itself.

Subscribe to topic Bibliography Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Andress, David. The Terror. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Francois Furet & Mona Ozouf & Arthur Goldhammer. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Jean-Paul Marat | Biography, Death, Painting, Writings, & Facts | Britannica Accessed 12 Oct 2022.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens. Vintage, 1990.

- Van Alstine, Jeanette. Charlotte Corday. Generic, 1890.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this article into another language!

Questions & Answers

What did the death of marat do for the french revolution, why was marat assassinated, what role did jacques-louis david play in marat's assassination, related content.

Charlotte Corday

Federalist Revolts

4 Women of the French Revolution

French Revolution

Hauer's Portrait of Charlotte Corday

Portrait of Charlotte Corday

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

| , published by Kessinger Publishing (2010) |

| , published by Kessinger Publishing (2006) |

| , published by Kessinger Publishing (2008) |

| , published by Waveland Pr Inc (2001) |

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2022, October 22). Assassination of Marat . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2092/assassination-of-marat/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " Assassination of Marat ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified October 22, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2092/assassination-of-marat/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " Assassination of Marat ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 22 Oct 2022. Web. 22 Jun 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 22 October 2022. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

|

|

| . |

Description (1748-1825) |

|

| Analysis of Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David during the three decades of the Revolutionary period in France (c.1785-1815), Jacques-Louis David exemplified the new style of Neoclassicism as well as the didactic nature of , championed by the . Winner of the prestigious (1774), his three early masterpieces - (1785, Louvre, Paris), (1787, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and (1789, Louvre, Paris) - mark the apogee of in France. He is best-known however for his propagandist painting (1793), which transformed a violent and ruthless revolutionary into a political martyr. Following the execution of his protector Robespierre (1758-94), David was briefly imprisoned before being rehabilitated under The Directory (1795-99). However he soon transferred his allegiance to Napoleon Bonaparte, eventually becoming official painter to the new regime, which showered him with honours. His best works of this period include (1800 Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) and (1800, Louvre, Paris). After Napoleon's fall in 1815, David went into self-imposed exile in Brussels. Influenced by such people as (1717-68) as well as (1728-79) he was the last of the great to leave behind a firm group of followers - sometimes known as the 'School of David' - who included Louis Girodet-Trioson (1767-1824), (1771-1835), (1780–1867), and later (1815-91). was a full-blown attempt to turn a bloodthirsty zealot into a tragic hero who was martyred for the revolutionary cause. In its focus on a contemporary political issue, the picture follows the tradition set two decades previously by (1738-1820), who painted (1770, National Gallery, Ottowa) in memory of Wolfe's demise at the Battle of Quebec (1759). David had already essayed a work of recent history, (1790-94, Musee National du Chateau de Versailles), but was unable to finish it because of the changing political climate. In particular, the revolutionary "unity" it was supposed to portray, no longer existed; and many "revolutionary heroes" were, by 1793, seen as traitors to the cause. The same can be said for Marat, whose posthumous reputation declined significantly as the Revolution developed. However, David's talent as a political painter, well versed in both and , has endowed with an life of its own, quite independent from Marat's reputation in real life. (1814, Prado, Madrid) by . |

|

|

|

|

) that caused him to itch constantly, for which the only palliative was immersion in a bath. He also wore a 'turban' soaked in vinegar to reduce the discomfort on his scalp. Because of this he regularly used his bathroom as an office and spent much of his time in his bathtub writing out long lists of suspects to be tried and executed. The painting depicts Marat in the final moments of his life, shortly after being stabbed. immortalized Marat as a martyr and hero of the people, and rapidly became an iconic image of the French Revolution. David achieved this by harnessing all the features commonly used in of the lamentation of Christ, or scenes of Christian martyrdom. - see, for example, (1500, St Peter's Basilica, Rome) by Michelangelo - David transforms a messy, chaotic assassination into an icon of peaceful martyrdom. He has amended and edited the truth so carefully that nothing rings false. Although a withered invalid in life, Marat has been given long muscular arms in death. His right arm is left dangling in a manner reminiscent of Jesus in (1601-3, Vatican Museums) by Caravaggio. His oozing skin is now smooth and unblemished.

is one of his most memorable images. In assuring his audience that Marat really did look like the dead Christ, he deliberately deluded them about the nature and character of his subject. In this sense he adapted the tried-and-true methods of propagandists everywhere. . After Napoleon's fall and the restoration of the monarchy, David went into exile in Belgium. Despite many invitations, he never returned to France. After his death the painting was largely ignored until it was 'rediscovered' by some 20 years later. Interpretation of Other 18th-Century Paintings (1717) by Jean-Antoine Watteau. (1750-3) by Tiepolo. (1767) by Jean-Honore Fragonard. (1768) by Joseph Wright of Derby. (1781) by Henry Fuseli. |

| .

|

The Art Post Blog | Art and Artists Italian Blog

The death of marat: analysis and curious facts.

THE DEATH OF MARAT BY DAVID: ANALYSIS AND CURIOUS FACTS

On July 13th 1793 the news of the death of Marat, a protagonist of the French Revolution, shocked France. Marat was stabbed to death and his murderer, Charlotte Corday, four days after the assassination and after a summary trial, was executed by guillotine.

In this post you’ll discover the history of a masterpiece that depicts one of the most tragic moments in the 18th-century France.

The Death of Marat by David

WHY A PAINTING OF THE DEATH OF MARAT WAS PAINTED

Jacques-Louis David was the official painter of the French Revolution, and in 1792 was also elected as a Deputy of the Convention, and aligned with the Jacobins, who represented the most radical political party during the French Revolution. So, it was almost automatic for him to be commissioned to execute a painting that would celebrate the Death of Marat , which was considered as a martyrdom.

Marat was a leading figure of the French Revolution. The Death of Marat was caused by a woman, Charlotte Corday, who believed that he was responsible for the more radical course the Revolution had taken through his role as a journalist and a Jacobin deputy. The woman stabbed Marat while he was immersed in his bathtub and David, one of the most important artists of the 18 th century , chose to portray the moment after the murder.

ANALYSIS OF THE DEATH OF MARAT BY DAVID

David did a painting that is the celebration of a martyr of the Revolution . The room is bare and dark. There’s only Marat lying in the bathtub and few objects of a man who dedicated himself to the good of the French citizens. Marat holds in his hands a pen and a paper his assassin had given him before killing him. On the floor is the murder weapon.

There are a pen and an inkwell on a simple wood box that acts as a desk. On it David painted the inscription : À MARAT, DAVID (TO MARAT, DAVID).

Marat’s pose, with his unmoving arm, draws inspiration from “The Entombment of Christ” by Caravaggio, housed in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, in the Vatican City.

CURIOUS FACTS ABOUT THE DEATH OF MARAT BY DAVID

It may seem odd that the Death of Marat occurred while the hero of the French Revolution was in his bathtub. However, it was not rare. Marat suffered from a skin disease that obliged him to have long and everyday baths, during which he kept working and meeting any kind of personalities.

There are three versions of this painting. The first one hangs in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels , the second is housed in Reims and the third one is part of the Louvre works.

David was a close friend of Marat and supported politically him on different occasions, especially when they had to vote for the death of the King of France Louis XVI.

4 thoughts on “ The Death of Marat: analysis and curious facts ”

Did the death of Marat change the course of the Revolution? Who took over after the assassination? I know Napoleon came in a tad later.

Marat’s death is the event that will lead to Robespierre’s period of Terror. The Reign of Terror was characterised by a high number of death sentences and persecutions of opponents of the Revolution. After his death, Marat’s heart was removed from his body, embalmed and placed in a stone urn. His copper urn was placed on the altar like a crucifix during his funeral. There was also a public exhibition of Marat’s body but, due to the intense heat and Robespierre’s opposition, the funeral was rushed through. After his death there was the fall of the Jacobin regime and Marat continued to be venerated for a time. They decided to move his body to the Panthéon in Paris, where the bodies of Voltaire, Descartes and Lepeletier (deputy assassinated by a royalist in 1793) already rested. However, the body was moved again and is now lost.

Come e da chi venne ucciso Marat?

La sua assassina era Charlotte Corday. Quattro giorni dopo l’omicidio fu processata e condannata alla ghigliottina.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

15 Things You Should Know About The Death of Marat

By kristy puchko | jun 11, 2015.

A strangely hypnotic portrait, Jacques-Louis David 's The Death of Marat has emerged as one of the most famous images of the blood-soaked French Revolution. The history behind this morbid masterpiece is even richer than its color palette.

1. The Death of Marat depicts a gruesome political murder .

Outspoken journalist and notable member of the Montagnards, Jean-Paul Marat would never see the French Revolution's conclusion in 1799. On July 13 th of 1793, the 50-year-old writer was murdered by 24-year-old Charlotte Corday, who was either, depending on the propaganda you believe, a supporter of the monarchy or a supporter of the less radical Girondins, and blamed Marat for the escalating violence of the revolution. After making no attempt to escape after stabbing him, Corday was apprehended and executed by guillotine just four days later.

2. The Death of Marat was propaganda.

Not only the leading artist of his time, but also a zealous Jacobin and "official artist" of the radical revolutionary cause, David was asked by the revolutionary government to glorify three of its lost members for political gain. Essentially, David was charged with making Marat a publicly recognized martyr to the cause and an epic hero.

3. It's both an idealized and accurate portrait of Marat .

The propaganda angle informed David's creative choices, urging him to blend fact and fiction. Almost like a crime scene photo, David carefully captured the green rug, bathtub, papers and pen left behind by the late revolutionary. However, he opted to exclude Marat's physical imperfections.

The reason Marat was working in the bathtub to begin with was because he suffered from a skin condition, likely severe eczema. To soothe his skin, he habitually bathed in oatmeal. In depicting Marat’s final bath, David decided to portray his friend as a beautiful beacon, free of such superficial flaws.

4. David pulled from religious inspiration to make Marat appear like a martyr.

The positioning of Marat's right arm, long and limp, cascading down the canvas, has drawn comparisons to the death pose of Jesus in Caravaggio's The Entombment of Christ . David was a noted fan of the 16th century Italian painter and also mimicked his use of light.

5. David also drew from Greek and Roman sculpture.

Art historian E.H. Gombrich explained of the creation of The Death of Marat:

"He had learned from the study of Greek and Roman sculpture how to model the muscles and sinews of the body, and gave it the appearance of noble beauty; he had also learned from classical art to leave out all the details which were not essential to the main effect, and to aim at simplicity.”

6. The Death of Marat was revolutionary for several reasons.

The first is that it depicts a martyr of the French Revolution. The second is that it was painted in the midst of the French Revolution, mere months after Marat's demise. The last revolutionary element relates to how it marked a change from David's typical subject matter. He'd previously pulled his subjects from classical antiquity, but here his muse was a contemporary figure.

7. The Death of Marat is the only one of David’s propaganda paintings to survive.

The Death of Lepeletier was destroyed on July 27 th , 1794 during the coup d'état known as the Thermidorian Reaction. The Death of Bara was never completed.

8. David decided to exclude Marat's killer almost completely.

While historian Alphonse de Lamartine would go on to describe Corday as "the Angel of Assassination," David was understandably less fond of Marat's murderer. He chose instead to focus on the man he admired, and only includes a mention of Corday in the writings surrounding Marat's corpse.

Similarly, he chose to remove the offending knife from his colleague's chest where Corday had left it. Instead, it sits, stained with blood, on the floor.

9. Corday's treachery is revealed in Marat's hand.

Corday gained access to Marat's private moment by entreating the writer to read a petition. As depicted by David, he was about to sign it as he was stabbed. The artist makes it clear that in his dying moments Marat's last thoughts were only of the revolution.

10. The Death of Marat was initially popular.

Presented by David to his peers in November 15, 1793, the painting was instantly so beloved by the Montagnards and their sympathizers that it was hung in the hall of their National Convention of Deputies. Reproductions were also made for further propaganda use. But as the tide turned against the Montagnards, so too did opinion of the painting. To protect it, David hid the work when he himself was exiled for his part in the Reign of Terror.

11. The Death of Marat got a second life after David's death.

Twenty-one years after David passed away in 1825, renewed interest came from French art critic and poet Charles Baudelaire's praises of the long-forgotten portrait.

Baudelaire wrote :

“The drama is here, vivid in its pitiful horror. This painting is David’s masterpiece and one of the great curiosities of modern art because, by a strange feat, it has nothing trivial or vile … This work contains something both poignant and tender; a soul is flying in the cold air of this room, on these cold walls, around this cold funerary tub.”

12. The iconic French painting now calls Brussels home.

After having been banished for a second time after the fall of Napoleon, David fled with the painting and lived out the rest of his days in the Belgian capital. Sixty-one years later, David’s family decided to bequeath the painting to the city that accepted David. And the Royal Museum of Fine Arts has been proud to display The Death of Marat since 1886.

However, reproductions can be found in museums in Dijon, Reims, and Versailles.

13. It has inspired a couple of major tributes.

In 1907, Edvard Munch, best known for The Scream , made an interpretation that put a nude Corday front and center. Picasso also applied his unique vision to the subject in 1931.

14. It's repeatedly referenced in pop culture.

In the movies, Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon and Derek Jarman's Caravaggio mimic the painting’s composition in their mise-en-scene. Andrzej Wajda's Danton includes a scene of David's creation of The Death of Marat . The scene was brought to life in Abel Gance's 1927 film Napoleon . It was rendered in garbage in the landfill documentary Waste Land .

In 2013, it was gender-swapped with Lady Gaga in Marat's spot for ARTPOP. And it has even been memed in response to contemporary conflicts.

15. The Death of Marat has become more famous than Marat.

Because of David's moving—if manipulative—depiction of his fallen friend, The Death of Marat has struck a chord and spent the last two centuries becoming a highly recognized painting. Though some viewers might not know it by name, they recognize its influential iconography. But Marat the man is known primarily because of this very portrait.

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

- Mission Statement

- Editorial Board and Field Editors

- Past Editors

- Terms of Use

- Submission Guidelines for Reviewers

- Republication Guidelines

- Citation Guidelines

- Letters to the Editor

- Dissertation Submission Guidelines

- 2011 Centennial Project

William Vaughan and Helen Weston are contributing editors to this volume in a recently launched series by Cambridge University Press, Masterpieces of Western Painting . Each volume in the series offers a group of essays on a single painting by specialists in the field representing different methodological perspectives. The objective is to provide a concise history and reassessment of paintings that belong to the Western canon. A volume of this nature devoted to David’s Marat is timely since the field of David studies has undergone an intense period of revitalization over the past decade, launched by the 1989 David retrospective exhibition at the Louvre. The Marat had long been considered an icon of the French Revolution and this makes it challenging to offer new perspectives. This book succeeds, however, in doing just that and in admirably fulfilling the goals of this series. The introduction by Vaughan and Weston and the subsequent six essays are written in a clear and limpid prose. Each essay presents new research and perspectives on this extremely significant painting with an emphasis on sound scholarship and historical contextualization.

After receiving immediate acclaim and success in 1793, the fortunes of the painting in the 19th and first half of the 20th century fluctuated, quite expectedly, with the continual reevaluations of Marat’s reputation by differing political factions and regimes. In the year 2000 it remains an icon of the French Revolution and the singular composition that has come to define David as the political painter par excellence of the Revolution. In the past twenty years the Death of Marat has also been a locus of fascination for art historians and historians of the French Revolution and has been the subject of extensive study in numerous articles, essays, and books. The celebrations of the bicentennial of the French Revolution were only one factor in this revival of interest. The ambiguity of Marat as a tainted hero, murdered ignominiously in his bathtub by a fervent young woman, not for his deeds but for his words, has struck a chord. In seeking to commemorate the one “significant” moment of his life, David chose to depict Marat breathing his last breath, slumped literally in a bloodied bath. Many elements in the painting serve as a counterbalance to the heroic, idealized figure, including a curious narrative created by the various types of writing juxtaposed one above the other (David’s dedication on the writing table/tombstone, Marat’s letter and assignat, and Corday’s perfidious letter at the top of this hierarchy), and the knife used to murder Marat lying adjacent to the pen still held in the victim’s hand.

In Vaughan and Weston’s book many new perspectives and contexts are brought to bear that were not found in the literature previously. Vaughan and Weston provide a cogent and informative introduction to The Death of Marat which succinctly recounts the history of Marat’s death and funeral, the role of the main protagonists, and offers a description of the painting along with the circumstances of its creation and an overview of its reception and fortunes. Each editor also contributes an outstanding and important essay. Vaughan examines the composition as both historical document and history painting, emphasizing that David was following the common practice of history painters of the time by altering events in order to commemorate more cogently their significance. In so doing, he places the painting in broader aesthetic and theoretical contexts such as the goals and ideals of history painting in France and the prescribed role of the history painter within the Academy. Vaughan studies the pictorial rhetoric of the painting and seeks to define the new hybrid genre of portrait-as-history that David has created, and that combines the heroic exemplum virtutis with the pietà (the influence of Christian iconography as well the images of the antique conclamatio have been much studied). He stresses the importance of attending closely to the visual language of the painting, its specific features as well as its “pared-down” Spartan style as a primary mode of understanding meaning. He reviews David’s educational and aesthetic experiences in Italy in the 1770s, especially Rome and suggests that, in addition to neoclassicism, David encountered the theory and practice of the sublime in Rome, possibly through contact with Sergel, the Swedish sculptor, and the Swiss painter Fuseli. Placing the Marat in the context of the pictorial language of the sublime as well as that of classicism opens up new avenues for inquiry in David studies.

Weston’s essay is equally important and thought provoking. She re-examines Corday’s metonymic inclusion in the painting through the letter held in Marat’s left hand as well as the bloodied knife that lies adjacent to his right hand that still holds his pen. Weston argues that David, through a subtle manipulation of pictorial signs, sought to discredit Corday and diminish her significance as sole perpetrator of the crime, a role that she worked actively to promote from her prison cell. Weston contrasts David’s composition with engravings inspired by it that do include the murderess at a moment just before or after the crime. These juxtapositions demonstrate the subtlety of David’s use of Corday’s perfidious letter adjacent to Marat’s “sincere” request to help a poor widow and her family. The letters, which stand in dramatic contradistinction in intent and tone, provide the narrative background for the significant moment. Weston focuses attention on the role and function of letter writing and its ramifications, contrasting Corday’s “royalist” writing and penmanship style with that of the “republican” Marat. This is a fascinating context in which to re-examine Corday and her role in the history of the Revolution with that of Marat. The context of the theme of letters in the 18th century and representations of reading and writing opens up exciting new avenues for further exploration.

Tony Halliday had the particularly fructive idea of examining the painting in the context of private commemorative portraits of the recently deceased. He relates the image in particular to the private posthumous portrait and proposes that many portraits from the 16th-18th centuries, hitherto presumed to depict living individuals, actually are commemorative and depict the recently deceased. Related to developments in funerary practice and private mourning, Halliday contends that the posthumous portrait emerged as an important genre in 18th-century French art and that in the Marat David responded to a new pictorial language that revealed a private rather than public identity, and sought to move the spectator to emotions of bereavement and loss. In addition to the private effigy, Halliday places the Marat in the context of its public or political functions and meanings relating the work to Roman Republican funeral effigies well-known through historical descriptions as well as to 18th-century wax effigies of the recently deceased, including waxworks exhibitions of political figures such as those by Philippe Curtius, uncle of Madame Tussaud (who made a wax effigy of Marat that also figures into the discussion). The death masks and subsequent busts of Marat were a significant part of this effigy culture. Halliday’s research reveals the richness and breadth of the field of 18th-century portraiture.

In his essay, Tom Gretton re-examines the historical context of the period of Marat’s murder, including David’s role as a Jacobin politician/painter, Marat as l’ami du peuple , the emerging role of the “People” vis-à-vis Jacobin control and the confluence of David-Marat in the summer of 1793 with its clashing factions and political discourses. Gretton signals David’s dilemma in creating a successful composition of Marat as revolutionary martyr because Corday answered in an unexpected way Marat’s call to action, her murderous assault embodying the values promulgated by her victim—"the exaltation of political violence, the personalization of political conflict, and the fascination with political conspiracy." (51) The relationship between discourse and violence expressed in David’s painting is underscored by Gretton as a key to understanding the period of the Terror.

One rarely learns about how a painting is made in terms of methods and materials and this is the subject of Libby Sheldon’s informative essay. Her study reveals David as a master craftsman, well-schooled in the techniques of making a painting from the preparation of the canvas to the actual mixing and application of paints. Sheldon interprets the results of infrared reflectography of the painting. This process revealed David’s underdrawing of the Marat and presented a wealth of new information about the artist’s procedures in preparation and use of the canvas as well as changes he made from the original underdrawing to the final painting. The subtle changes from drawing to painting demonstrate David’s attention and care to the smallest of details. One telling example is the packing case, made of knotted wood that serves Marat as a writing table. Infrared reflectography revealed that the position of the box, drawn with a ruler rather than freehand, was subtly adjusted during the drawing stage, as were specific details. Sheldon analyzes the underdrawing itself, most likely made with a black chalk drawing tool, and follows the adjustments David made as he drew in the outlines of Marat. These discoveries are particularly fascinating in terms of the changes made in the details of the hand and face, and how they transformed the expression of the final painting. Sheldon describes her discoveries about the subsequent stages of the painting, also revealed through the infrared relectography process, such as the colored sketch, a form of rough underpainting that David used in creating the flesh tones of the figure and left in its entirety to serve as the background. She concludes with a technical discussion of the use and application of paints, the mixing of colors, and the types of brushes employed. This technical study of the painting gives us a clear picture of David at work on the canvas and we can follow the choices he made at each stage that resulted in the final painting.

In the concluding essay of the book, David Lomas looks at works inspired by David’s painting and the historical event of Marat’s murder by Corday. Using Freudian theory he analyzes what he characterizes as the “phantasies” of Munch in such works as Death of Marat I (1907) and Marat and Charlotte Corday (1932-5). Similarly, he uses Freudian analysis to address Picasso’s depictions of male sacrifice or murder by women, including, among others, Woman with a Stiletto, Death of Marat (1931), Composition (Death of Marat) (1934) and Blind Minotaur with Death of Marat (1934). He relates Picasso’s works of the early 1930s to the revival in Paris of the cult of Marat by the Left who invoked the French Revolution to further their cause and considered Marat to be a prophet of modern socialism. The use of David’s Marat as a political icon in the 1930s is a fascinating episode in the fortunes of the painting that had become linked so intimately with its subject. The essays in the book make recent scholarship and new interpretations accessible to a broad range of informed readers. The fruitful results of the authors’ focus on one inexhaustible painting demonstrate the value to be gained from such a concentration. The book is a very welcome addition to David studies.

Dorothy Johnson Roy J. Carver Professor of Art History, School of Art and Art History, University of Iowa

- By accessing and/or using caa.reviews, you accept and agree to abide by the Terms & Conditions .

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793)

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793). (2016, Sep 12). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay

"Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793)." StudyMoose , 12 Sep 2016, https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793) . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay [Accessed: 23 Jun. 2024]

"Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793)." StudyMoose, Sep 12, 2016. Accessed June 23, 2024. https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay

"Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793)," StudyMoose , 12-Sep-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay. [Accessed: 23-Jun-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). Jacques-Louis David’s “Death of Marat” (1793) . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/jacques-louis-davids-death-of-marat-1793-essay [Accessed: 23-Jun-2024]

- “Death of Socrates” by Jacques-Louis David Pages: 5 (1422 words)

- The Painter Jacques-Louis David Pages: 6 (1511 words)

- Jacques-Louis David: Artistic Evolution and Impact Pages: 5 (1215 words)

- Mattie’s Transformation: From Immaturity to Maturity in Fever 1793 Pages: 2 (549 words)

- History and fiction intertwined in narrating Fever 1793 Pages: 6 (1652 words)

- Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Works, Death Pages: 3 (688 words)

- Jacques Derrida and His Deconstruction Pages: 6 (1563 words)

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Foremost Important Thinker Pages: 8 (2179 words)

- The Views of Paulo Freire and Jean Jacques Rousseau Pages: 6 (1526 words)

- Jacques-Yves Cousteau Pages: 3 (603 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat (detail)

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793, oil on canvas, 65 x 50-1/2″ (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels)

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Early scientific work

Attacks on the aristocracy, activities in the national convention, assassination.

What did Jean-Paul Marat do before the French Revolution?

How was jean-paul marat involved with the national convention, how did jean-paul marat die, what is jean-paul marat’s legacy.

- What was the French Revolution?

Jean-Paul Marat

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Heritage History - Biography of Jean-Paul Marat

- World History Encyclopedia - Assassination of Marat

- Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh - Doctor Jean-Paul Marat (1743–93) and his time as a physician in Great Britain

- Hektoen International - Jean-Paul Marat, physician and revolutionary

- Alpha History - Biography of Jean Paul Marat

- Jean-Paul Marat - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

What is Jean-Paul Marat famous for?

Jean-Paul Marat was a prominent figure in the French Revolution . His polemics against the French monarchy and aristocracy were influential in the rise of the Jacobin Club , but his advocacy for the execution of counterrevolutionaries earned him many enemies.

Jean-Paul Marat was a renowned doctor in London until he returned to France in 1777. He served as a physician to various aristocrats while performing scientific experiments in his spare time. Although his paper on electricity received accolades from the Royal Academy of Rouen in 1783, he was never elected to the Academy of Sciences .

Jean-Paul Marat became a delegate to the National Convention in 1792 after scathingly denouncing the National Assembly for refusing to remove King Louis XVI . He became popular among Parisians for supporting tax reforms and new state-sponsored programs. The conservative Girondin faction despised Marat and arraigned him on political charges in 1793, but he was acquitted.

On July 13, 1793, Jean-Paul Marat received a visit from the young Girondin activist Charlotte Corday . Corday claimed to have intelligence on Girondins in Caen and was admitted to his quarters, where Marat was taking a medicinal bath. There Corday drew a knife from beneath her clothes and stabbed him through the heart.

Jean-Paul Marat’s assassination in 1793 quickly became a symbol of the French Revolution for Jacobin supporters, who had seized power from the Girondins just weeks before. The murder was immortalized through Jacques-Louis David ’s painting The Death of Marat . Marat’s radical thought shaped the direction of the Jacobins during their brief but devastating Reign of Terror .

Jean-Paul Marat (born May 24, 1743, Boudry, near Neuchâtel , Switzerland—died July 13, 1793, Paris, France) was a French politician, physician, and journalist , a leader of the radical Montagnard faction during the French Revolution . He was assassinated in his bath by Charlotte Corday , a young Girondin conservative .

Marat, after obscure years in France and other European countries, became a well-known doctor in London in the 1770s and published a number of books on scientific and philosophical subjects. His Essay on the Human Soul (1771) had little success, but A Philosophical Essay on Man (1773) was translated into French and published in Amsterdam (1775–76). His early political works included The Chains of Slavery (1774), an attack on despotism addressed to British voters, in which he first expounded the notion of an “aristocratic,” or “court,” plot; it would become the principal theme of a number of his articles.

Returning to the Continent in 1777, Marat was appointed physician to the personal guards of the comte d’Artois (later Charles X ), youngest brother of Louis XVI of France. At this time he seemed mainly interested in making a reputation for himself as a successful scientist. He wrote articles and experimented with fire, electricity, and light. His paper on electricity was honoured by the Royal Academy of Rouen in 1783. At the same time, he built up a practice among upper-middle-class and aristocratic patients. In 1783 he resigned from his medical post, probably intending to concentrate on his scientific career.

In 1780 he published his Plan de législation criminelle (“Plan for Criminal Legislation”), which showed that he had already assimilated the ideas of such critics of the ancien régime as Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau and was corresponding with the American Revolutionary leader Benjamin Franklin . More serious, perhaps, was Marat’s failure to be elected to the Academy of Sciences. Some historians, notably the American Louis Gottschalk, have concluded that he came to suffer from a “martyr complex,” imagining himself persecuted by powerful enemies. Thinking that his work refuted the ideas of Sir Isaac Newton , he joined the opponents of the established social and scientific order.

In the first weeks of 1789—the year that saw the beginning of the French Revolution —Marat published his pamphlet Offrande à la patrie (“Offering to Our Country”), in which he indicated that he still believed that the monarchy was capable of solving France’s problems. In a supplement published a few months later, though, he remarked that the king was chiefly concerned with his own financial problems and that he neglected the needs of the people; at the same time, Marat attacked those who proposed the British system of government as a model for France.

Beginning in September 1789, as editor of the newspaper L’Ami du Peuple (“The Friend of the People”), Marat became an influential voice in favour of the most radical and democratic measures, particularly in October, when the royal family was forcibly brought from Versailles to Paris by a mob. He particularly advocated preventive measures against aristocrats, whom he claimed were plotting to destroy the Revolution. Early in 1790 he was forced to flee to England after publishing attacks on Jacques Necker , the king’s finance minister; three months later he was back, his fame now sufficient to give him some protection against reprisal. He did not relent but directed his criticism against such moderate Revolutionary leaders as the marquis de Lafayette, the comte de Mirabeau, and Jean-Sylvain Bailly , mayor of Paris (a member of the Academy of Sciences); he continued to warn against the émigrés , royalist exiles who were organizing counterrevolutionary activities and urging the other European monarchs to intervene in France and restore the full power of Louis XVI.

In July 1790 he declared to his readers:

Five or six hundred heads cut off would have assured your repose, freedom, and happiness. A false humanity has held your arms and suspended your blows; because of this millions of your brothers will lose their lives.

The National Assembly sentenced him to a month in prison, but he went into hiding and continued his campaign. When bloody riots broke out at Nancy in eastern France, he saw them as the first sign of the counterrevolution.

In 1790 and 1791 Marat gradually came to the view that the monarchy should be abolished; after Louis XVI’s attempt to flee in June 1791, he declared the king "unworthy to remount the throne" and violently denounced the National Assembly for refusing to depose the king. As a delegate to the National Convention (beginning in September 1792), he advocated such reforms as a graduated income tax , state-sponsored vocational training for workers, and shorter terms of military service . Though he had often advocated the execution of counterrevolutionaries, Marat seems to have had no direct connection with the wholesale massacres of suspects that occurred in the same month. He had opposed France’s declaration of war against antirevolutionary Austria in April, but, once the war had begun and the country was in danger of invasion, he advocated a temporary dictatorship to deal with the emergency.

Actively supported by the Parisian people both in the chamber and in street demonstrations, Marat quickly became one of the most prominent members of the Convention . Attacks by the conservative Girondin faction early in 1793 made him a symbol of the Montagnards , or radical faction, although the Montagnard leaders kept him out of any position of real influence. In April the Girondins had him arraigned before a Revolutionary tribunal. His acquittal of the political charges brought against him (April 24) was the climax of his career and the beginning of the fall of the Girondins from power.

On July 13, Charlotte Corday , a young Girondin supporter from Normandy, was admitted to Marat’s room on the pretext that she wished to claim his protection, and she stabbed him to death in his bath (he took frequent medicinal baths to relieve a skin infection). Marat’s dramatic murder at the very moment of the Montagnards’ triumph over their opponents caused him to be considered a martyr to the people’s cause. His name was given to 21 French towns and later, as a gesture symbolizing the continuity between the French and Russian revolutions, to one of the first battleships in the Soviet navy.

The Death of Marat , by French artist and member of the Jacobin Club Jacques-Louis David , was painted just days after the murder. Called the “Pietà of the Revolution” (in reference to Michelangelo’s sculpture ) and widely considered David’s masterpiece, the painting is frequently reproduced for its historical and artistic value.

Sample details

- Views: 1,204

Related Topics

- Health equity

- Mental Health

- Hospitality

- Healthy Diet

Overview of Painting “Death of Marat”

The portrait of Marat encapsulates the artist’s grief, political fervor, and artistic ability. It is a personal homage to his friend, as seen by an inscription on the side of a makeshift desk: A Marat David.” The brushwork in the corpse is striking. The artist has stripped the painting to its bare essentials, creating a powerful and moving image with the tragic solemnity of the Pieta. It is gruesome subject matter to depict, but the artist has commemorated an event and created a portrait of a martyr – a dying man in a graceful and heroic pose against a stark setting.

In his hand, he holds a bloody note which reminds us of Michelangelo’s Pieta. The bathtub is mostly covered by a wooden board that is gray-brown in color. The background is entirely bare and consists of shades of gray. Warm yellow light softens the horror of the scene further. The formal analysis of The Death of Marat reveals its orthogonal construction as a gift of eternity with no death involved. Writing serves as a way to stop time, while money helps us understand how Marat helped poor people. Despite the dark background representing death and darkness, Marat survives, and even though he dies, his public image remains eternal.

ready to help you now

Without paying upfront

The protagonist is now in front of us, and we can feel Marat’s gaze. This means that Marat lives forever for David. To understand this artwork, we need to consider two aspects: the style used by David, which is Neoclassicism, and the artist’s purpose of turning Marat into a hero with high moral virtues according to classical tradition. Neoclassicism was a rediscovery of classical art from Greek and Roman times.