- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When was London founded?

- Was London bombed during World War II?

- What is London known for?

British Museum

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- JewishEncyclopedia.com - British Museum, London, England, United Kingdom

- History Today - The British Museum Opened

- British Museum - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Recent News

British Museum , in London , comprehensive national museum with particularly outstanding holdings in archaeology and ethnography . It is located in the Bloomsbury district of the borough of Camden .

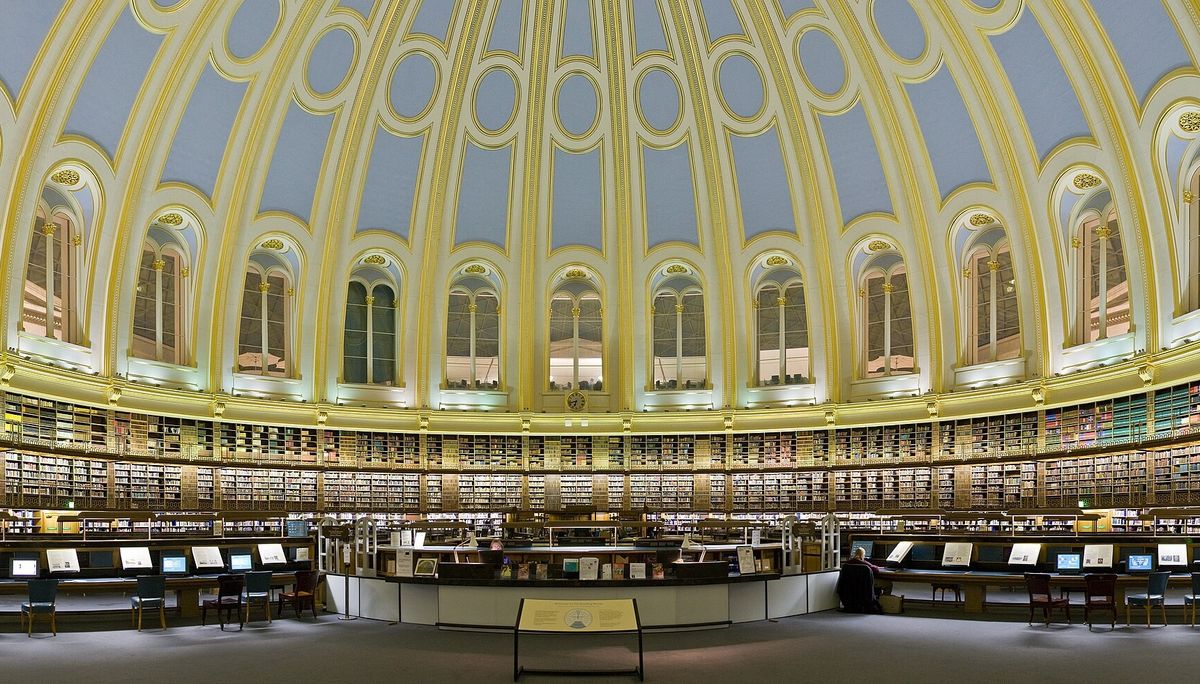

Established by act of Parliament in 1753, the museum was originally based on three collections: those of Sir Hans Sloane ; Robert Harley, 1st earl of Oxford ; and Sir Robert Cotton . The collections (which also included a significant number of manuscripts and other library materials) were housed in Montagu House, Great Russell Street, and were opened to the public in 1759. The museum’s present building, designed in the Greek Revival style by Sir Robert Smirke , was built on the site of Montagu House in the period 1823–52 and has been the subject of several subsequent additions and alterations. Its famous round Reading Room was built in the 1850s; beneath its copper dome laboured such scholars as Karl Marx , Virginia Woolf , Peter Kropotkin , and Thomas Carlyle . In 1881 the original natural history collections were transferred to a new building in South Kensington to form the Natural History Museum , and in 1973 the British Museum’s library was joined by an act of Parliament with a number of other holdings to create the British Library . About half the national library’s holdings were kept at the museum until a new library building was opened at St. Pancras in 1997.

After the books were removed, the interior of the Reading Room was repaired and restored to its original appearance. In addition, the Great Court (designed by Norman Foster ), a glass-roofed structure surrounding the Reading Room, was built. The Great Court and the refurbished Reading Room opened to the public in 2000. Also restored in time for the 250th anniversary of the museum’s establishment was the King’s Library (1823–27), the first section of the newly constituted British Museum to have been constructed. It now houses a permanent exhibition on the Age of Enlightenment .

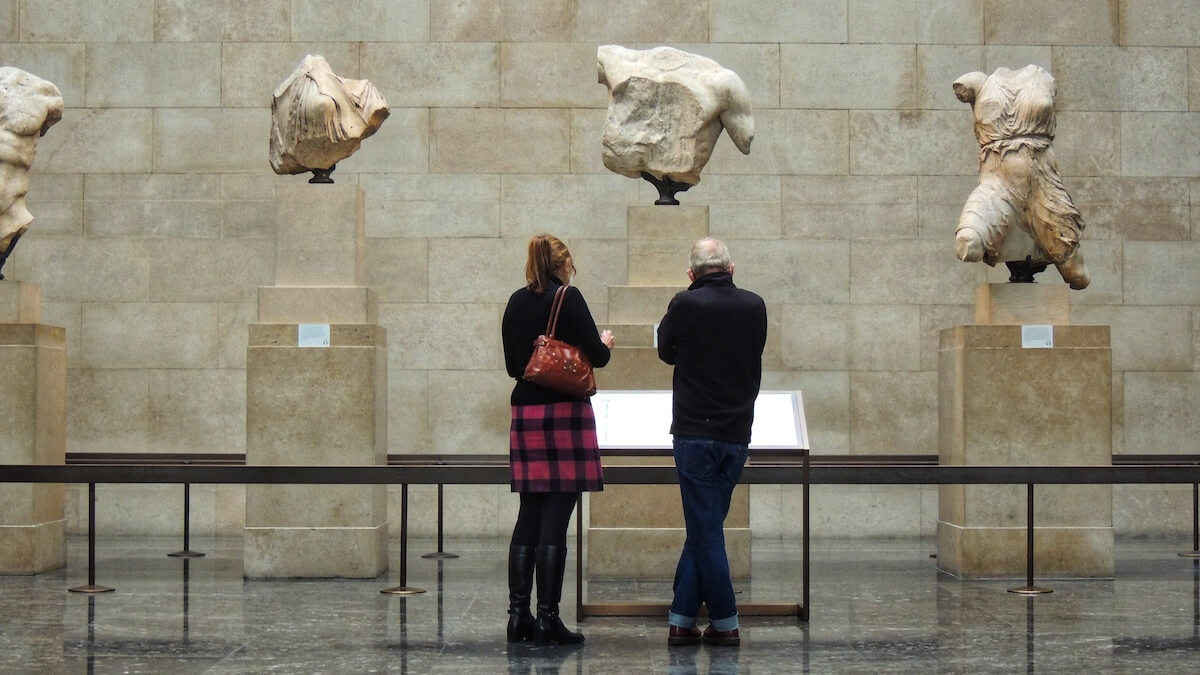

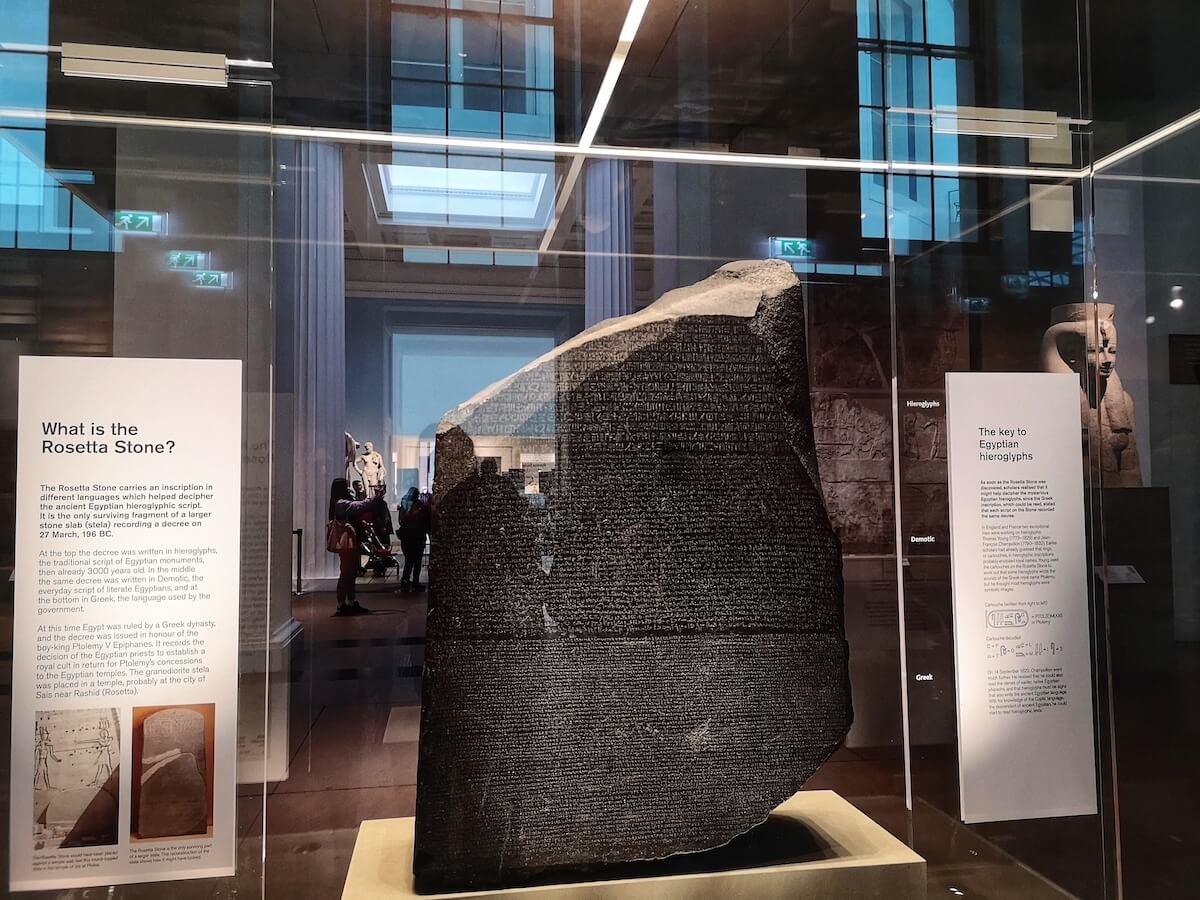

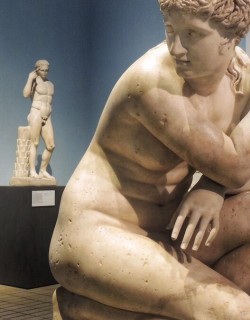

Among the British Museum’s most famous holdings are the Elgin Marbles , which were removed in the early 19th century from the Parthenon in Athens and shipped to England by arrangement of Thomas Bruce, 7th Lord Elgin . The Greek government frequently demanded the return of the marbles, but the British Museum—claiming among other reasons that it had saved the marbles from certain damage and deterioration—did not accede, and the issue remained controversial. Other objects in the collection include Greek sculptures from the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and from the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus; the Rosetta Stone , which provided the key to reading ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs; the Black Obelisk and other Assyrian relics from the palace and temples at Calah (modern Nimrūd) and Nineveh ; exquisite gold, silver, and shell work from the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur ; the so-called Portland Vase , a 1st-century- ce cameo glass vessel found near Rome; treasure from the 7th-century- ce ship burial found at Sutton Hoo , Suffolk; and Chinese ceramics from the Ming and other dynasties .

Exploring the British Museum: A Journey Through Time, Memory, and Cultures

London boasts a plethora of remarkable museums, each with unique treasures and stories. Among these cultural gems, the British Museum stands out as a testament to human history, art, and culture. Having visited many museums in London, I find myself consistently drawn back to the British Museum again and again.

The British Museum, located in Holborn, just off the famous Bloomsbury Square in London, is full of memories for me of previous visits and, equally, it is a place of collective, global memory on an enormous scale. Combining the rich heritage of the British Museum itself, established as far back as 1753, it also plays a role in revealing a great tapestry of ancient cultures that are displayed within its walls.

The British Museum holds the title of the first public national museum to cover all fields of knowledge and contains a vast collection of eight million works! It is the largest collection in the world and includes the controversial Greek Elgin Marbles and the Egyptian Rosetta Stone.

Apparently in 2022, the British Museum experienced a significant increase in visitors; in total, attracting around four million in that year. A figure that makes it the third most-visited art museum globally. Putting its incredible artifacts aside for a moment, the historic architecture of the building alone is enough to keep me captivated.

In particular I am always keen to enter the courtyard, known as the Great Court that encircles the Reading Room, in order to gaze at the extraordinary fried egg, glass roof ceiling. Its dazzling brilliance, coupled with the white stone porticos, creates a visually stunning space that makes me want to look up and endlessly marvel at its thousands of unique panes of glass.

It is in fact the largest covered public square in Europe, and within this space there are sculptures from an impressive range of cultures that include, one from fifth-century Ireland, late Ming Dynasty China, ancient Nimrud (now in Iraq), and the Greek and Roman empires. In the centre of all this stands the circular Reading Room; world-famous in its own right as a former exalted centre of learning.

In terms of the British Museum’s history, the Great Court’s new ceiling (pictured at top) is actually relatively recent, and was only unveiled in December 2000. I remember reading about it in one of the Sunday papers and eagerly wanting to visit and see it for myself. Not only was I not disappointed, I remember telling my boyfriend’s Grandfather about it. His Grandfather happened to be a well known artist and sculptor and if I’m honest I was more than a little in awe of him. We both were. I had just finished telling him about what I had thought about seeing this marvellous sight, when he left the room. For a moment I didn’t know what to think, but then he came back with a sketch book and showed me his visit to the museum. He had sat in the Great Court and drawn sketches of the people that he had seen there, doing exactly what I had done, looking up.

As yet, on this private tour of the museum, we haven’t even ventured into any of the galleries, so I think it’s time for me to introduce you to my favourite one, the Enlightenment gallery. Housed in the oldest part of the building, it was originally designed for King George III's Library, and it is vast in scale. Filled with display cabinets of artifacts from the 18th century and bookcases that rise to the ceiling there is so much to take in. It’s a permanent exhibition and fascinating to me because it feels like it connects me to a time in history that I’m particularly interested in.

I’m moving on quite swiftly now, discarding thoughts and memories as they emerge so that I can take you to one more section of the museum that I love, and that is the Egyptian Sculpture gallery. With the poem ‘Ozymandias’ by Shelley, in my head, it’s incredible to contemplate the rise and fall of civilisations as you walk through this gallery. The length of time of the Egyptian civilisation, its impressive monuments, vast statues and intricate carvings now all that remains of this vanished civilisation. Meanwhile, I find myself debating the issue of ownership, the rightful location of these artifacts, whether that be Egypt or London. It’s a complex issue, and one that involves many points of view; such as the balance between cultural preservation and accessibility. I certainly don’t have the answer.

What is true though, is that the British Museum charges no admission fee, allowing free access to all those seeking cultural enrichment.

Currently, tickets are available for two temporary exhibitions; "Burma to Myanmar" and "Legion: Life in the Roman Army," to provide even more reasons to keep returning.

What the British Museum means to me, is an institution that sparks curiosity in human nature; in the magnificence of human endeavour to express itself, to witness itself and to be witnessed. Whether you are drawn to the Enlightenment gallery, the Egyptian Sculpture gallery, or the overarching architectural marvels, the British Museum is most certainly spectacular.

* * *

Sarah Agnew

Sarah Agnew is a heritage photographer at sarahagnew.co.uk and blogger on modernbricabrac.com . Find her on Facebook at @sarahagnewphotos .

The British Museum

The British Museum holds in trust for the nation and the world a collection of art and antiquities from ancient and living cultures.

The British Museum was founded in 1753, the first national public museum in the world. From the beginning it granted free admission to all ‘studious and curious persons’. The Museum was based on the practical principle that the collection should be put to public use and be freely accessible. It was also grounded in the Enlightenment idea that human cultures can, despite their differences, understand one another through mutual engagement. The Museum was to be a place where this kind of humane cross-cultural investigation could happen. It still is.

Housed in one of Britain’s architectural landmarks, the collection is one of the finest in existence, spanning two million years of human history. Visitor numbers have grown from around 5,000 a year in the eighteenth century to nearly 6 million today.

- Visit britishmuseum.org/

- Are you an expert from this institution? Register to write

- Article Feed

Displaying all articles

Friday essay: Indigenous afterlives in Britain

Gaye Sculthorpe , The British Museum

We identified 39,000 Indigenous Australian objects in UK museums. Repatriation is one option, but takes time to get right

Maria Nugent , Australian National University ; Gaye Sculthorpe , The British Museum , and Howard Morphy , Australian National University

Friday essay: 5 museum objects that tell a story of colonialism and its legacy

Alistair Paterson , The University of Western Australia ; Andrea Witcomb , Deakin University ; Gaye Sculthorpe , The British Museum ; Shino Konishi , The University of Western Australia , and Tiffany Shellam , Deakin University

Tall ship tales: oral accounts illuminate past encounters and objects, but we need to get our story straight

Maria Nugent , Australian National University and Gaye Sculthorpe , The British Museum

The Palestinian Museum opened without artefacts, but it’s still a beacon of hope

James Fraser , The British Museum

Curator & Section Head, Oceania, The British Museum

Project Curator for the Ancient Levant, The British Museum

More Authors

- In the Press

- Work with us

- Rome & Vatican Rome Vatican Colosseum Rome Food

- Italy Florence & Tuscany Venice & Northern Italy Pompeii & Herculaneum Amalfi Coast & Capri Naples & Southern Italy

Highlights of the British Museum: 10 Objects from Around the World

Tue 27 Sep 2022

When the doctor and avid collector Sir Hans Sloane donated his massive collection of 71,000 artefacts to the British State in 1753, the world’s first public national museum was born. Originally sited in the palatial Montagu House, the collection was free and open to ‘all studious and curious persons’ from the outset. The collection quickly grew, and a massive new neo-classical building designed by Robert Smirke was constructed between 1825 and 1857 to house the museum. As the British Empire reached the peak of its power and extent, objects kept flooding in from across the globe, and today the museum is home to a staggering 8 million objects. From ancient Greece to Egypt, Mexico, Nigeria and beyond, whatever you’re interested in you’ll find it here. You could easily spend weeks or months in the sprawling collection without seeing everything, but if you’re looking for somewhere to start then check out our guide to 10 highlights of the British Museum below!

The Parthenon Marbles

Also known as the Elgin marbles, this collection of Greek sculptures taken from the Parthenon in Athens is possibly the most important grouping of classical sculpture in existence. The Parthenon is the centrepiece of the Athenian Acropolis, and was decorated with sculptures by the renowned ancient sculptor Phidias and his assistants between 443 and 437 BC. The majority of the sculptures in the British Museum come from the 160 metre-long frieze that ran around the building, and features scenes from ancient war and mythology. Comprising hundreds of human, animal and mythological figures, the highly naturalistic Parthenon marbles are widely considered the high-point of the High-Classical period of Greek sculpture. The Earl of Elgin, Thomas Bruce, removed a large proportion of the Parthenon frieze between 1801 and 1812 and had them carted back to Britain in a move whose legality has been questioned ever since. The marbles remain amongst the British Museum’s most controversial objects but are an absolute must-see for anyone interested in Classical art.

Where to find it: Room 18, Ground Floor, Level 0

The Nereid Monument

This monumental tomb was likely constructed on the orders of Erbinna, the ruler of Xanthos in present-day Turkey. Although Xanthos was part of the Lycian empire, the influence of Greek models of classical architecture and sculpture were widely adopted in its monuments, and Erbinna’s tomb strongly recalls the form of a Greek temple. The monument is named after the highly expressive sculptures that were located between the tomb’s columns, which depict the Nereids - sea nymphs that provided protection to sailors on the stormy high seas. Although the temple’s reconstruction at the British Museum is hypothetical and the location of the individual sculptures open to debate, the Nereid monument gives a vivid sense of the refined culture of the Lycians.

Where to find it: Room 17, Ground floor, Level 0

Coffin of Hornedjitef

Most visitors coming to the British Museum make a beeline for the Egyptian rooms, and for good reason. The museum’s display of mummies, sarcophagi and funerary objects from the ancient empire on the Nile are truly jaw-dropping, none more so than the coffin and mummy of the Egyptian high priest Hornedjitef, who was responsible for the Temple of Amun at Karnak in the Ptolemaic period. For ancient Egyptians like Hornedjitef, the mummification of the body was central to one’s chances of life after death. The delicately decorated inner case of the priest’s coffin is a masterful example of Egyptian art, and features a map of the celestial sphere to help him on his journey through the afterlife. It’s an eerie experience indeed to lock gazes with this powerful figure from across the centuries, his eye shining out from the golden features of his sculpted face. Also belonging to Hornedjitef’s funerary objects is a fascinating papyrus Book of the Dead, a collection of spells and invocations that were intended to aid the defunct priest’s difficult journey through the underworld and into the afterlife beyond.

Where to find it: Room 63, Upper Floors, Level 3

The Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most important objects in the story of ancient Egypt, and was the final key to deciphering the hieroglyphic language that was for centuries one of the most enduring mysteries of Egyptology. The massive stone was originally part of a larger slab known as a stela , and has an official decree voicing support from the priests of Memphis for king Ptolemy V inscribed onto its surface. Crucially, the decree is recounted in three languages - hieroglyphics, or the official language of state, Demotic, or the popular script used in everyday Egyptian life, and Ancient Greek - the language of bureaucracy. As Ancient Greek was known to scholars when the stone was found at the end of the 18th century, it became possible to crack the code of the hieroglyphs by comparing the texts. The painstaking process was completed by French philologist Jean-François Champollion, paving the way for a new understanding of Egyptian history, society and culture.

Where to find it: Room 4, Ground Floor, Level 0

Winged Lions of Nimrud

With developed societies extending as far back as 10,000 BC, the Middle East was the cradle of ancient civilisation - it’s to the ancient Mesopatamians that we owe vital human discoveries such as the wheel, agriculture, writing, mathematics and much more. Between the 10th and 7th centuries BC the Neo-Assyrian empire was the world’s most powerful state, extending all the way from the Mediterranean in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east and the Caucasus Mountains in the north, and a number of colossal sculptures surviving to this day are testament to the wealth and grandeur of this lost civilisation. These enormous 9th-century BC sculptures of winged lions with stylised human heads and long beards originally guarded the throne room of King Ashurnasipal the city of Nimrud (now in northern Iraq), and were believed to protect the city from harm.

Where to find it: Room 6, Ground Floor, Level 0

Bronze Portrait of the Emperor Augustus

The ancient Roman empire was one of the greatest and most powerful civilizations the world has ever known, and its story is inextricably tied up with the empire’s first and longest-serving emperor - Augustus. Rising to power in the aftermath of the bloody civil war that was unleashed in the wake of Julius Caesar’s assassination , Augustus proved to be a brilliant statesman and popular ruler. This remarkable bronze portrait captures the charisma, dignity and commanding nature of the man: his magnetic gaze will be sure to stop you in your tracks as you make your way through the museum. The sculpture was originally part of a full-body statue of the emperor that stood near the Roman empire’s southern border in Egypt. The area was captured by the Sudanese Kushite kingdom in 25 BC, and the Augustan statue dismembered, decapitated and buried. Augustus would only see the light of day again nearly 2,000 years later, when it was excavated by English archaeologist John Garstang in 1910.

Where to find it: Room 70, Upper Floor, Level 3

Lewis Chessmen

Where to find it: Room 40, Upper Floors, Level 3

Sutton Hoo Helmet

The Anglo-Saxon ship burial discovered at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk in 1939 was one of the most exciting archaeological discoveries of medieval British history, recently immortalised in Netflix drama The Dig . Amongst the hoard’s highlights is this jaw-dropping decorated helmet. It’s one of only four complete helmets to survive from the Anglo-Saxon period, and dates from the 6th or 7th century. Constructed from iron covered in copper alloy panels, designs on the helmet depict scenes of warriors and zoomorphic motifs, indicating that the helmet was a highly prestigious object, equal parts functional and aesthetic.

Where to find it: Room 41, Upper Floors, Level 3

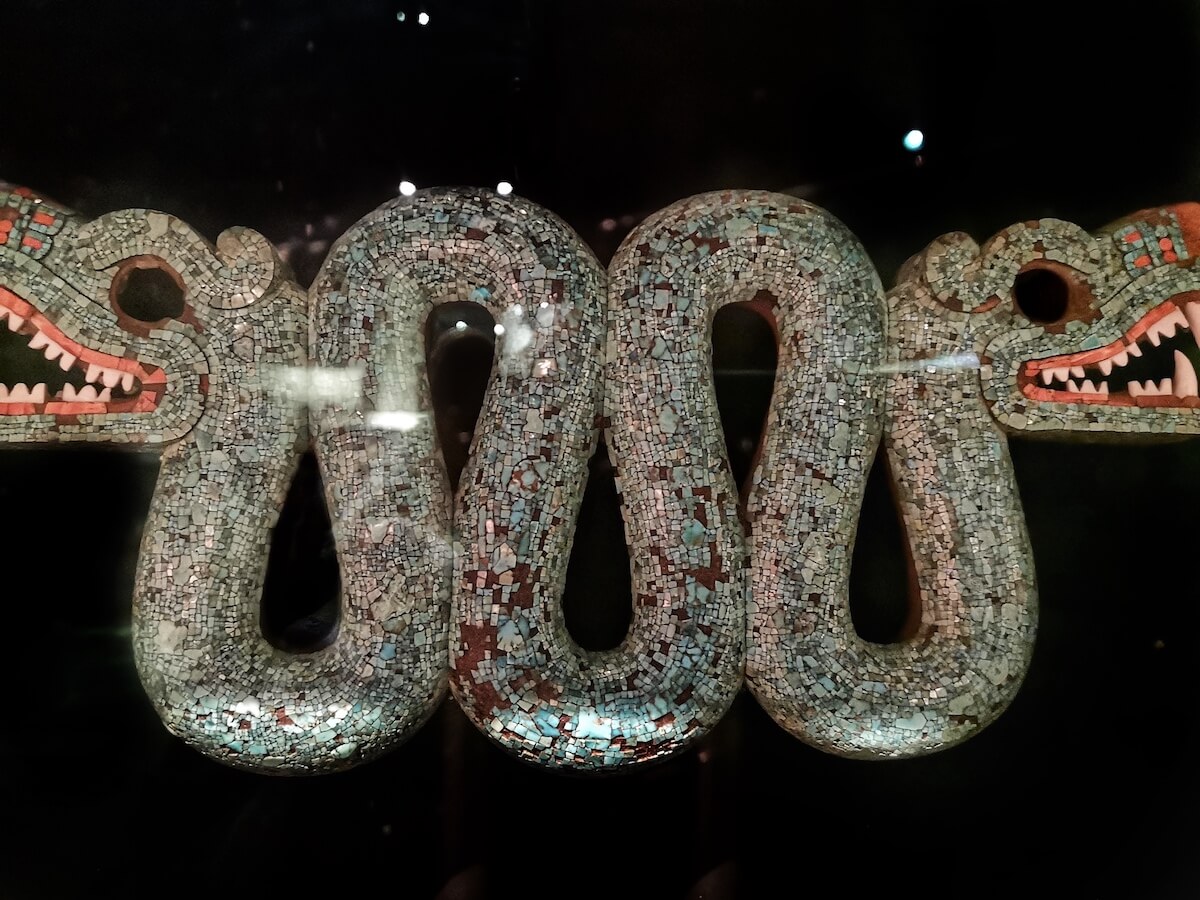

Mexican Serpent Mosaic

An iconic example of central-American art, this stunning double-headed serpent was meticulously crafted from over 2,000 pieces of turquoise mosaic and shells attached to a wooden framework. The snake was sculpted sometime in the 15th or 16th century, and reflects the religious significance that the reptile held for the Aztec people, whose most important god, Quetzlcoatl, took the form of a feathered serpent. The Aztec empire was the most extensive and largest in the Americas before the arrival of European invaders, and serpent sculptures survive from across their vast territories. The shimmering turquoise tiles and gleaming bared teeth seem to make the snake come alive, and it’s not hard to imagine the powerful effect this object would have had when worn during rituals and religious ceremonies.

Where to find it: Room 27, Ground Floor, Level 0

The Ife Head

This magnificent brass sculpture depicts the portrait of an Ooni, or sacred ruler of the Yoruba-speaking Kingdom of Ife in modern-day Nigeria wearing an elaborate headdress. The beautiful head dates from the 14th-century, and its striking naturalism and psychological intensity is characteristic of Ife sculpture. When this stunning object first went on display in the Museum in the 1930s it caused something of a controversy, with many viewers refusing to accept that 14th-century West African artists were capable of such realism. Today however the object is accepted for what it is - one of the shining cultural examples of a highly developed African kingdom.

Where to find it: Room 25, Lower Floor, Level -2

Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led guided itineraries through the colllections of the British Museums as well as many other sites in London. To find out more, check out the full range of our London tours here !

Post Categories

Suggested Tours

Best of London Tour with Westminster Abbey and the National Gallery

Tower of London and Borough Market Tour

British Museum and Bloomsbury Walking Tour

Bath and Stonehenge Day Trip from London

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive 5% off your first booking!

You'll also receive fascinating travel tips and insights from our expert team

Subscribe to our free newsletter

Thank you for subscribing!

You should shortly receive a confirmation message with your discount code. If you do not receive this within 5 minutes, please email [email protected].

British Museum, Imperialism and Empire

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- Paige Elizabeth Rooney 3

220 Accesses

Has the sun actually set on the British Empire in the twenty-first century? This paper seeks to answer this question by observing the history of the British Museum during the era of imperialism and empire. The first section discusses the evolution of the British public’s interest in cultural objects from the colonies, looking specifically at the original objects in the British Museum as well as how British wars, expeditions, personal collections, and world fairs contributed to the museum’s growth in the nineteenth century. In the following section, the question of a British national identity during this time period is examined through the displays in the British Museum. Finally, the stories of artifacts stolen from Egypt, Greece, Nigeria, and China during the nineteenth century as well as the repatriation efforts in recent years for these artifacts are described in order to demonstrate that the British Museum continued to be an imperialist institution even after the British colonies gained independence.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The British Museum: Imperialism and Empire

The Encounter with the Ottoman Heritage: Imperial Grandeur, Medieval Decay, and Double Discourses

Displaying the Cultures of Islam at the British Museum: The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World

Barringer, T. (1998). The South Kensington museum and the colonial project. In T. Barringer & T. Flynn (Eds.), Colonialism and the object: Empire, material culture, and the museum . London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Belam, M. (2017, September 13). British Museum says too many Asian names on labels can be confusing. The Guardian .

Breckenridge, C. (1989). The aesthetics and politics of colonial collecting: India at world fairs. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31 (2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0010417500015796 .

Article Google Scholar

British Museum Act 1963. (1963, July 10). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1963/24/enacted

Canaday, J. (1965, July 14). Art: African Bronzes in Philadelphia: British Museum Lends 35 Benin Plaques. New York Times (1923–Current File) .

Clunas, C. (1998). China in Britain: The Imperial collections. In T. Barringer & T. Flynn (Eds.), Colonialism and the object: Empire, material culture, and the museum . London: Routledge.

Concerning the Ethics of Loot. (1904, December 17). Los Angeles Times (1886–1922) .

Duthie, E. (2011). The British Museum: An imperial museum in a post-imperial world. Public History Review, 18 , 12–25. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v18i0.1523 .

Edwardes, C., & Milner, C. (2003, July 20). Egypt demands return of the Rosetta Stone. The Telegraph .

Harris, C., & O’Hanlon, M. (2013, February 1). The future of the ethnographic museum. Anthropology Today, 29 (1), 8–12.

Jacobs, J. (2010). Confronting Indiana Jones: Chinese Nationalism, Historical Imperialism, and the Criminalization of Aurel Stein and the Raiders of Dunhuang, 1899–1944. In S. Cochran & P. G. Pickowicz (Eds.), China on the margins (pp. 65–90). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Jones, J. (2003, September 11). Spoils of war: The art of Benin is elegant, fiery – And mostly locked in the British Museum. The Guardian , p. 8.

MacKenzie, J. M. (2010). Museums and empire: Natural history, human cultures, and colonial identities . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

MacKenzie, J. M. (2019). Culture and British imperialism in the nineteenth century. In The Palgrave encyclopedia of imperialism and anti-imperialism (pp. 1–15). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91206-6_43-1 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Owen, J. (2006). Collecting artefacts, acquiring empire. Journal of the History of Collections, 18 (1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhs/fhi042 .

Pagani, C. (1998). Chinese material culture and British perceptions of China in the mid-nineteenth century. In T. Barringer & T. Flynn (Eds.), Colonialism and the object: Empire, material culture, and the museum . London: Routledge.

Sloane, H. (1753). The Will of Sir Hans Sloane, Bart. Deceased . London: Printed for John Virtuoso.

The British Museum Story. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story

The Parthenon Sculptures. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_press/statements/parthenon_sculptures.aspx

Wintle, C. (2008). Career development: Domestic display as imperial, anthropological, and social trophy. Victorian Studies, 50 (2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.2979/vic.2008.50.2.279 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA

Paige Elizabeth Rooney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Paige Elizabeth Rooney .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Brooklyn College, New York, USA

Immanuel Ness

Belfast, UK

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Rooney, P.E. (2021). British Museum, Imperialism and Empire. In: Ness, I., Cope, Z. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29901-9_62

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29901-9_62

Published : 03 February 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-29900-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-29901-9

eBook Packages : History Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Get More Zócalo

Eclectic but curated. Smart without snark. Ideas journalism with a head and heart.

Zócalo Podcasts

Why Is the British Museum Still Fighting to Keep the Parthenon’s Marble Sculptures?

Removed from greece more than 200 years ago, they now fuel a post-brexit fight over who is civilized and who is a barbarian.

Passengers walk past copies of some of the Parthenon Sculptures displayed in the British Museum, at the Acropolis Metro station in Athens, Greece, in 2009. Courtesy of Thanassis Stavrakis/ Associated Press .

by Gabrielle Bruney | March 18, 2020

Two-and-a-half millennia ago, Athenian artist Phidias depicted the Greek myth of the Centauromachy in his sculptures for Athens’ Parthenon. Athens, the wealthy and powerful democratic nation-state, was of course analogous in the story to the civilized Lapiths; any foes the city faced resembled the barbaric Centaurs, who, as the tale goes, attempted to rape the bride at a Lapith wedding feast, launching a battle between the two peoples.

The Parthenon still stands all these centuries later, but Phidias’ work, which once adorned the building, is scattered between the Athens’ Acropolis Museum and the British Museum nearly 2,000 miles away.

It’s been more than 200 years since Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin, obtained a royal Ottoman mandate to excavate near the Parthenon, document the sculptures, and “take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions, or sculptures therein.” An international debate has raged ever since: Did Britain’s Lord Elgin, who was the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which then ruled Greece, have the legal right to remove the sculptures? Should the British Museum, the current home of the sculptures, yield to Greek demands for their return?

Recently, a line in a potential post-Brexit trade deal being drafted by Europe demanding that Britain “return unlawfully removed cultural objects to their countries of origin” has reignited the debate. It’s an issue that, much like Brexit itself, boils down to a question of “Leave” or “Remain.” But perhaps it’s also a question of who, in modern Europe, are the civilized Lapiths, and who are the barbaric Centaurs?

To understand the turns the discussion has taken, it’s helpful to go back to the sculptures’ beginning, 2,500 years ago, when the Athens city-state was at the height of its power and influence—Euripides and Sophocles were writing their great tragedies; Socrates was still young.

After a Persian invasion destroyed an older temple, Athens celebrated Greece’s victory by building the Parthenon in its place. Its name means “the virgin’s abode,” and the temple was dedicated to Athena, the virgin goddess of war and wisdom. Though a temple, it was not strictly a religious site and was used as a treasury.

The building featured hundreds of sculptures by Phidias, one of the greatest artists of Ancient Greece, whose figures tell stories of gods, celebrations, and battles. Phidias installed finely carved sculptures on multiple levels of the building: the most fully modeled were on its pediment, while the 92 highly sculpted friezes known as the metopes, sat right below the roof. Finally, the frieze, in low relief, lined the walls just above the temple’s inner columns.

Like the Centauromachy, some of the stories carved into the marble are allegorical. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that the frieze contained exactly 192 horsemen, which was the number of Athenian warriors who died at the Battle of Marathon during the first Persian invasion of Greece.

Greek Foreign Minister George Papandreau, accompanied by his wife Anda and daughter Margarita visit the British Museum in London in 2000. Courtesy of Alastair Grant/ Associated Press .

The beauty and detail of the sculptures are truly awe-inspiring—every fold of every peplos, the draping, sleeveless tunic favored by women of ancient Greece, is included; not even fingernails are neglected on a frieze that was mounted 30 feet above eye level. At the center of the temple stood a giant gold-plated statue of Athena herself, known as the Athena Parthenos. At some point, that sculpture disappeared from the temple and the historical record, its whereabouts unknown.

Over the millennia, the Parthenon has changed with times, states, and faiths. Around 450 A.D., it was rededicated to a different virgin saint, Mary of Nazareth, and next became a mosque after the Ottomans took Athens in the 15th century. When a Venetian shell hit the temple in 1687, during a war between the Turks and Venice, it became the temple we know now—a ruin.

That was how Elgin viewed it at the dawn of the 19th century, when, armed with his mandate from the royal Ottoman empire, he chiseled off and conveyed to England the sculptures, metopes, and friezes from the temple that would become known as the Parthenon Marbles.

It has since been the subject of fierce debate whether or not the hazy perimeters of the stunningly inexact document Elgin obtained allowed him to simply sift through the debris surrounding the Parthenon and collect any treasures that had already fallen from the building, or remove the works from the structure.

By contemporary standards, what happened at the Parthenon was deeply unethical. No major institution like the British Museum would today acquire artifacts from an occupied land under the permission of the invading force. But those who would return the sculptures see the question of lawfulness simply: “They were ‘stolen’ in that an alien Ottoman regime was in power at the time,” says Dame Janet Suzman, celebrated Shakespearean actress and chairperson of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles.

And this isn’t merely a modern interpretation of Elgin’s actions: Even in 1801 contemporary witnesses to the despoiling of the Acropolis were framing the situation as a tragedy. “Athena wept over her lost virginity,” one traveler wrote at the time.

In 1816, the British Museum bought the Marbles from Elgin. The Elgin Marbles, as they became known, became an instant phenomenon when they went on view the following year. Keats was observed gazing at them in an uninterruptible rapture, and wrote his famous sonnet “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” in response. The French Romantic Alphonse de Lamartine declared the Marbles “the most perfect poem ever written in stone on the surface of the earth.”

But they were also instantly controversial when they went on view—even in early 19th-century England, it was considered shocking for an ancient monument to be stripped of its adornments. Byron, Greece’s most famous foreign champion, was appalled, and dedicated five stanzas of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” to his outrage.

When Greece won its independence in 1832, the campaign for the Marbles’ return began in earnest.

The British Museum, would, in turn, begin to justify its possession of the marbles by positioning itself as preservers of the sculptures, which the Ottomans had taken to grinding up for limestone. More recently, the institution has gone on to argue that it sheltered and preserved the marbles from environmental damage as the Parthenon was subject to acid rain and other environmental pollutants.

But those who advocate for repatriation point to the shoddy record of British care for the marbles, starting with the two years some of the works spent at the bottom of the ocean when one of Elgin’s ships sank, and continuing through a 1930s effort to scrub them whiter-than-white with steel wool and household bleach. In 2014, Britain undermined its longstanding argument that the Marbles were too fragile to be moved by loaning them to a museum in St. Petersburg.

The controversy will not go away, especially at the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery, which attempts to help visitors envision the works as they were intended to be displayed. Here, it’s impossible to escape the fact that this is not the way these works were supposed to be displayed. The sculptures of the east pediment are arranged at one end of the rectangular gallery; the sculptures of the west at the other, while friezes and metopes line the walls in between at eye level. This attempt to emulate what was lost in stripping the stones from the Parthenon only underscores one of the most convincing arguments cited by those who would repatriate the Marbles to Athens: this art is intensely site-specific.

“This case is unique because the Parthenon itself is standing there,” says political sociologist and University of Virginia researcher Fiona Rose-Greenland. “So you have the idea that these things are actually ornaments for a structure that exists. It’s not like they were statues pulled out of the ash heap of some building that’s no longer there.”

The Duveen Gallery does contribute one major benefit to viewers—they’re no longer dozens of feet from the ground, as they were when they decorated the Parthenon. But Phidias explicitly carved the sculptures with this distance in mind; figures in the frieze were sculpted to account for the distorting perspective of eyes 35 feet below.

Though no one will ever again stand at the Parthenon and gaze up at the sculptures above, it would be possible for visitors to see the art closer to its birthplace. Partially in response to the British Museum’s long-held contention that Greece lacked a suitable home for the Marbles, the country in 2003 opened the Acropolis Museum, where the Parthenon sculptures owned by Greece are now displayed. The Parthenon itself is visible from the galleries of the Acropolis Museum, “an eye flicker [away] from the picture window in the dedicated Parthenon Gallery,” according to Suzman.

Visitors at Athens’ Acropolis Museum look at the vista to the ancient Temple of Parthenon. Courtesy of Petros Giannakouris/ Associated Press .

Though a British government spokesperson recently said that returning the marbles is “ not up for discussion as part ” of the Brexit trade deal, there are precedents for similar returns of ancient art. In 2006, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art agreed to repatriate to Italy the Euphronios Krater, a terra cotta bowl that predates the Parthenon by approximately 100 years. The Krater may be the finest surviving example of ancient Greek pottery, and in 1972 the Met purchased it for more than one million dollars, a staggering amount at the time. But the bowl had been looted from an Italian tomb, and eventually the museum agreed to return it to Italy, in exchange for three lesser early vases.

Opponents of repatriation in the op-ed pages of the British press trot out the rather hoary argument that the return of the Marbles could lead to the gradual emptying of the world’s encyclopedic museums. The Rosetta Stone would follow the marbles out the doors of the British Museum shortly thereafter, then Berlin’s Neues Museum would be forced to ship its bust of Nefertiti back to Egypt. In fact, Egyptian wings the world over would be empty husks.

It is in global institutions like the British Museum, these advocates argue, that art achieves its true cosmopolitan promise. If art is for all peoples and all ages, then it’s most appropriate that it be showcased in museums featuring art made by all peoples during all ages, rather than segregated in far-flung state museums that serve narratives of glorious nationalistic pasts. Shortly after the Euphronios Krater was returned to Italy, a reporter for the New York Times noted that the bowl didn’t seem to attract many visitors in its new-old home. Is the Krater better served at the relatively little-known Cerveteri Museum where it now resides than it was at the Met, with its more than 6 million annual visitors?

But, “if really what we’re talking about is equal share for all, and a universal culture, then why isn’t there an old Dutch masters museum in Namibia?” asks Rose-Greenland, “Why isn’t the Art Institute of Chicago handing over its exquisite collection of French 19th-century watercolors to a Peruvian museum for a long-term loan?”

“Ownership necessarily betrays historical balances of power,” says James Cuno, art curator, historian, and president and CEO of the Getty Trust. But he argues that the fact that Western developed nations possess a disproportionate share of the world’s encyclopedic museums doesn’t mean that the idea of such museums is invalid. The cure isn’t fewer encyclopedic museums, but more of them, in more countries.

More problematic is another question raised by some supporters of global museums—that contemporary communities lack serious claims on objects built for and by people who lived centuries ago on the same patch of earth. The logic of this objection is that either art knows no age or national boundary, or it so grounded in its context that every other culture and era is equally without claim to it.

In his book Cosmpolitanism , Kwame Anthony Appiah argues that parsing thousands of years of human creation into categories of “yours” and “mine” isn’t easy, particularly since it can hardly be argued that the ancients were creating art with any of us in mind. He points out that the Euphronios Krater, found in and returned to Italy, was actually a Greek bowl. “Patrimony, here,” he writes, “equals imperialism plus time.”

In the case of the Parthenon Marbles, however, the suggestion that contemporary Greek people are not the legitimate heirs of Ancient Greece has a very ugly history. Elgin himself remarked that “The Greeks of today do not deserve such wonderful works of antiquity,” and “[Modern Greeks] have nothing whatsoever in common with [Ancient Greeks]. He made this claim based on the idea, popularized by the 19th-century Austrian travel writer and theorist Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer, that modern Greeks are descended from Slavs. “The race of the Hellenes has been wiped out in Europe,” he wrote in 1830. “Physical beauty, intellectual brilliance, innate harmony and simplicity, art, competition, city, village, the splendour of column and temple … [have] disappeared from the surface of the Greek continent.”

Though controversial from its inception and now debunked, Fallmerayer’s implicitly racist theory has appeared as recently as 2015 in the conservative German newspaper Die Welt , in an article in which the author argued that Greece was the perpetual demolisher of Eurozone order, from the early 19th century through austerity. He writes that Greeks are not “descendants of a Pericles or Socrates” but “a mixture of Slavs, Byzantines, and Albanians”—less worthy of a place in the European order, pretenders to admission to the EU. As if foretold in Phideas’s sculptures of the Centauromachy, the discussion has been reduced to an explicitly racist rumination on who inherits the title of civilization from the Ancient Greeks, and who is cast out as a barbarian.

The works of Phidias were completed in 432 B.C., but it might be argued that the Parthenon Marbles were created in 1687 when that shell turned the Parthenon into a husk and many of its adornments to dust. These were the sculptures that Elgin began excavating in 1801— and no one can argue that the 19th-century Greeks who watched the Parthenon defiled are unrelated to the Greeks today who clamor for their return.

The Parthenon Marbles as they are now are not the same art as the works Phidias painted and sculpted. Recreations of the works are almost jarring—their bright colors seem garish to contemporary eyes—accustomed as we are to the cool white scrubbed marble that western curators claimed showed the elegant simplicity of Ancient Greece. And of course, in the place of missing faces and limbs we project our own imaginings of the ancients, projections that have become part of the works themselves. As Margaretha Rossholm Lagerlof writes in The Sculptures of the Parthenon , “The ancient artifact naturally possesses a certain sublimity from the sheer passing of time, but also because it represents an unfilled and unfillable void.”

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

KU ScholarWorks

- Enroll & Pay

- KU Directory

- KU ScholarWorks

- Libraries Scholarly Works

Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the origins of the British Museum. [Review Essay]

Collections

- Libraries Scholarly Works [533]

Items in KU ScholarWorks are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

We want to hear from you! Please share your stories about how Open Access to this item benefits YOU.

The University of Kansas prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, national origin, age, ancestry, disability, status as a veteran, sexual orientation, marital status, parental status, gender identity, gender expression and genetic information in the University’s programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies: Director of the Office of Institutional Opportunity and Access, [email protected] , 1246 W. Campus Road, Room 153A, Lawrence, KS, 66045, (785)864-6414, 711 TTY.

Last updated 27/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > The Antiquaries Journal

- > Volume 92

- > Ancient Cyprus in the British Museum: essays in honour...

Article contents

Ancient cyprus in the british museum: essays in honour of veronica tatton-brown . edited by thomas kiely. 295mm. pp 112, 95 figs plus line drawings. british museum research publication 180, london: british museum, 2009. isbn 9780861591800. £25 (pbk)..

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 October 2012

Access options

No CrossRef data available.

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Sarah Janes

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581512000819

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Why is the British Museum always in trouble?

Partly because it was bad. But partly because it was good

Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

“T he Essex Antiquities” doesn’t have quite the same ring. The sculptures that were hacked from the Parthenon in the early 19th century go by many names. They are called the “Parthenon Sculptures”, the “Parthenon Marbles” and, by traditionalists, “the Elgin Marbles” but never known by the name of the county in the south-east of England. Yet in 1902 part of the frieze from the Acropolis turned up in a rockery in a charming garden in Essex. Quite how it got there, as Mary Beard, a classicist, puts it, “we have no idea.”

The British Museum gets in trouble precisely because people do know how it acquired its bits of the Parthenon, and much else besides. This week’s drama was a spat between the visiting Greek prime minister, who likened the sculptures’ presence in London to cutting “the Mona Lisa in half”, and the British prime minister, who threw a tantrum in response and cancelled a planned meeting with his counterpart.

The Parthenon Sculptures are not the museum’s only controversial items. In recent years it has also been embroiled in arguments over the Benin Bronzes (Nigeria wants them back), the Rosetta Stone (Egyptians want that one) and the Easter Island statues (Rapa Nui claims them). It gets in trouble because it has far too many objects—8m at the last count, which is considered greedy. More recently, it has got in trouble for having too few—it let 2,000 items get stolen, which is clearly incompetent. It has been accused of dealing in stolen goods, exhibiting “pilfered” objects and generally being “Brutish”.

Not without cause. Many of its objects have objectionable back stories. Lord Elgin removed parts of the Parthenon so carelessly that they fell to the ground and shattered; the boat onto which others were loaded promptly sank. One infamous curator, E.A. Wallis Budge, bragged about how he had smuggled objects out of Egypt illegally by variously cutting them up, hiding them in books and, in one case, tunnelling into the back of a house while Egyptian officials guarded its front. “All Luxor rejoiced,” he wrote when he filched them. UNESCO would have been less thrilled.

Such looting should be seen in context, however. “One mustn’t judge Elgin unusually harshly,” says Paul Cartledge, emeritus professor of Greek at Cambridge. For Elgin was egregious but not exceptional. He wasn’t the only one to nick things from the Parthenon: parts of it were hacked off as souvenirs and left in the pockets of pleased tourists. Museums in four other countries have bits of the marbles. If Elgin “hadn’t got the Parthenon, a Frenchman would have got it”. An alarming thought.

Indeed competitive nationalism runs throughout the history of museums. Nationalism provided an excuse to take things. Budge argued that it was better for him to nick a mummy and bring it back to the British Museum since it has “a far better chance of being preserved” there than in Egypt. It is commonly said that the Rosetta Stone has three scripts on it but as Neil MacGregor, a former director of the museum, has pointed out, it has four. On the side it reads “Captured by the British Army in 1801”.

Nationalism also helped spur museums into existence. The British Museum was one of the first institutions to use the word “British” in its title and the first national museum to open its doors to the public, in 1759. It still spurs things on today. Most people never hear of an artefact until it becomes the focus of a row between countries, as the Parthenon Sculptures did again this week. The British Museum’s website lists 1,699 objects also associated with Elgin. Since no nations are arguing about them, no one cares.

The British Museum’s history is flawed, then, but also influential. Today, it is taken for granted that the obvious thing to do with old objects is to gather them all in a room, add labels, a loo and a gift shop selling Rosetta Stone rubbers, and then open it all up to the public. This was not always so. The British Museum is in trouble in part because it treated objects badly but also because it treated them well. Unlike the bits of the Parthenon that disappeared in tourists’ pockets, its sculptures are still there to get cross about. And, on the bright side, it also occasionally thwarted the French. ■

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in Britain, sign up to Blighty, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.

Explore more

This article appeared in the Britain section of the print edition under the headline “The Brutish museum?”

Britain December 2nd 2023

- How to restore Britons’ confidence in the police

- Post-Brexit Britain is splurging more on state aid

- Why Britain’s homes will need different types of heat pump

- The curious case of Nick Clegg

- How to change the policy of the British government

From the December 2nd 2023 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

More from Britain

How shallow was Labour’s victory in the British election?

The British party system may be fragmenting but voters delivered a coherent message

Labour’s victory is good for Britain’s union of four countries

It is not clear how long that will last

Labour’s landslide victory will turn politics on its head

But even with a majority this big, running bad-tempered Britain will not be easy

What now for Britain’s right-wing parties?

The Conservatives, Reform UK and the regressive dilemma

Labour is on course for a huge victory in the British election

An exit poll points to a collapse in the Tory vote

Nukes and King Charles—but no door key

The first 24 hours for a new British prime minister are odd, and busy

IELTS Essay Task 1: Museums

by Dave | Sample Answers | 2 Comments

This is an IELTS writing task 1 sample answer essay on the topic of a bar chart showing museum admissions in London from the real IELTS exam.

Please consider supporting my efforts to creative high quality IELTS materials for students around the world by signing up for my Patreon (and so you won’t miss out on any of my exclusive IELTS Ebooks)!

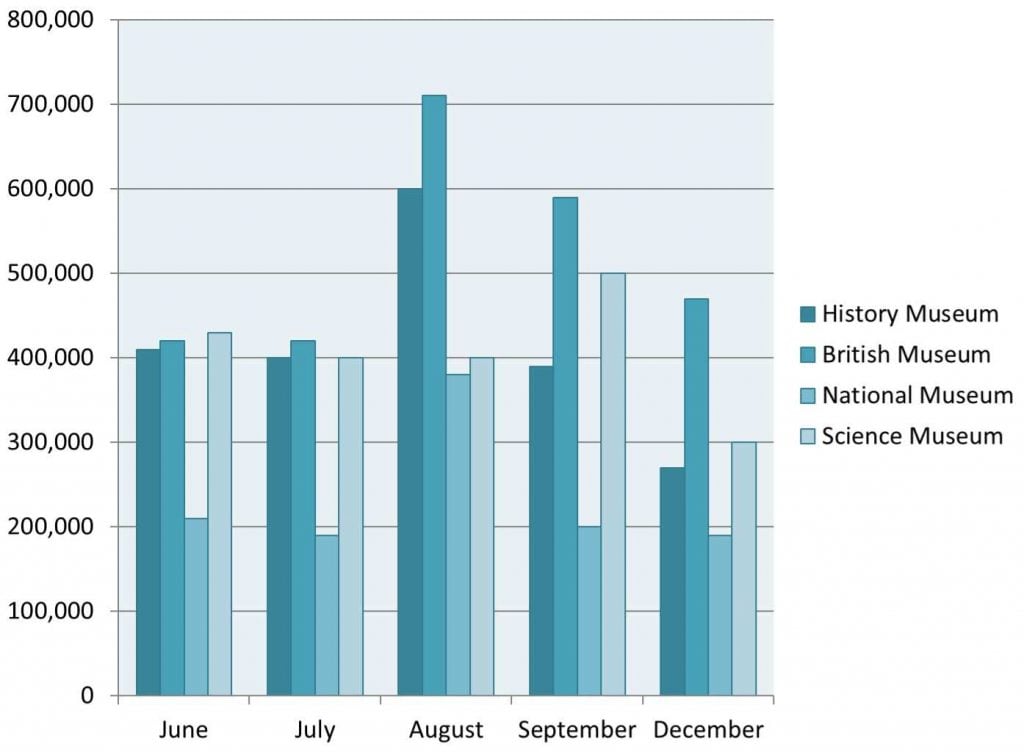

The bar chart shows the number of visitors to four London museums.

The bar chart compares attendance figures for museums in London over a period from June to December. Looking from an overall perspective, it is readily apparent that only the British Museum grew in popularity, while the others saw steep or moderate declines. In terms of overall figures, the British Museum was highest and the National Museum lowest throughout.

In June, the History Museum (410,000), the British Museum (420,000) and the Science Museum (430,000) had similar figures with the National Museum the outlier at just 210,000 visitors. Through July, numbers for all museums declined gradually, with the exception of the British Museum which was stable. August saw a shift in the pattern as the History and British Museum soared to 600,000 and 710,000, respectively. The Science Museum was unchanged but National Museum admissions doubled to 380,000.

By September, figures had fallen back to 390,000 and 590,000 for the History and British Museum, in turn, while the Science Museum rose to 500,000 visitors and the National Museum dipped to 200,000. At the end of the period, the History Museum continued to fall (270,000) along with the British Museum (470,000), National Museum (190,000), and the Science Museum (300,000).

1. The bar chart compares attendance figures for museums in London over a period from June to December. 2. Looking from an overall perspective, it is readily apparent that only the British Museum grew in popularity, while the others saw steep or moderate declines. 3. In terms of overall figures, the British Museum was highest and the National Museum lowest throughout.

- Paraphrase what the graph shows.

- Write a clear overview summarising the major trends and differences.

- Add an extra sentence to be sure that you have covered everything.

1. In June, the History Museum (410,000), the British Museum (420,000) and the Science Museum (430,000) had similar figures with the National Museum the outlier at just 210,000 visitors. 2. Through July, numbers for all museums declined gradually, with the exception of the British Museum which was stable. 3. August saw a shift in the pattern as the History and British Museum soared to 600,000 and 710,000, respectively. 4. The Science Museum was unchanged but National Museum admissions doubled to 380,000.

- Begin writing about the differences.

- Compare as much as possible.

- Move on to the next category to describe.

- Try to include all the data you can.

1. By September, figures had fallen back to 390,000 and 590,000 for the History and British Museum, in turn, while the Science Museum rose to 500,000 visitors and the National Museum dipped to 200,000. 2. At the end of the period, the History Museum continued to fall (270,000) along with the British Museum (470,000), National Museum (190,000), and the Science Museum (300,000).

- Write about the rest of the information.

- Make sure you have detailed all the information .

What do the words in bold below mean? Take some notes on a piece of paper to aid your memory:

The bar chart compares attendance figures for museums in London over a period from June to December. Looking from an overall perspective, it is readily apparent that only the British Museum grew in popularity , while the others saw steep or moderate declines. In terms of overall figures, the British Museum was highest and the National Museum lowest throughout .

In June, the History Museum (410,000), the British Museum (420,000) and the Science Museum (430,000) had similar figures with the National Museum the outlier at just 210,000 visitors. Through July, numbers for all museums declined gradually , with the exception of the British Museum which was stable . August saw a shift in the pattern as the History and British Museum soared to 600,000 and 710,000, respectively . The Science Museum was unchanged but National Museum admissions doubled to 380,000.

By September, figures had fallen back to 390,000 and 590,000 for the History and British Museum, in turn, while the Science Museum rose to 500,000 visitors and the National Museum dipped to 200,000. At the end of the period , the History Museum continued to fall (270,000) along with the British Museum (470,000), National Museum (190,000), and the Science Museum (300,000).

compares shows differences between

attendance figures number of people going there

period time

looking from an overall perspective, it is readily apparent that overall

grew in popularity more people went there

steep fast, large

moderate a little

in terms of when it comes to

highest biggest

lowest throughout smallest the whole time

similar figures numbers about the same

outlier exception

through to the end of

declined gradually went down slowly

exception different from the norm

stable unchanged

shift change

pattern trend

soared rose a lot

respectively in turn

unchanged stable

doubled increased 2x

fallen back decreased after increasing before

dipped fell

at the end of the period by the end of the time surveyed

continued to fall kept decreasing

Pronunciation

kəmˈpeəz əˈtɛndəns ˈfɪgəz ˈpɪərɪəd ˈlʊkɪŋ frɒm ən ˈəʊvərɔːl pəˈspɛktɪv , ɪt ɪz ˈrɛdɪli əˈpærənt ðæt gruː ɪn ˌpɒpjʊˈlærɪti stiːp ˈmɒdərɪt ɪn tɜːmz ɒv ˈhaɪɪst ˈləʊɪst θru(ː)ˈaʊt ˈsɪmɪlə ˈfɪgəz ˈaʊtˌlaɪə θruː dɪˈklaɪnd ˈgrædjʊəli ɪkˈsɛpʃən ˈsteɪbl ʃɪft ˈpætən sɔːd rɪsˈpɛktɪvli ʌnˈʧeɪnʤd ˈdʌbld ˈfɔːlən bæk dɪpt æt ði ɛnd ɒv ðə ˈpɪərɪəd kənˈtɪnju(ː)d tuː fɔːl

Vocabulary Practice

Remember and fill in the blanks:

The bar chart c___________s a_______________s for museums in London over a period from June to December. L__________________________________t only the British Museum g____________________y , while the others saw s______p or m___________e declines. I_________f overall figures, the British Museum was h_______t and the National Museum l_________________t .

In June, the History Museum (410,000), the British Museum (420,000) and the Science Museum (430,000) had s_______________s with the National Museum the o__________r at just 210,000 visitors. T_________h July, numbers for all museums d________________y , with the e__________n of the British Museum which was s_______e . August saw a s______t in the p_________n as the History and British Museum s_________d to 600,000 and 710,000, r____________y . The Science Museum was u__________d but National Museum admissions d_______d to 380,000.

By September, figures had f_____________k to 390,000 and 590,000 for the History and British Museum, in turn, while the Science Museum rose to 500,000 visitors and the National Museum d_________d to 200,000. A___________________________d , the History Museum c__________________l (270,000) along with the British Museum (470,000), National Museum (190,000), and the Science Museum (300,000).

Listening Practice

Listen to the related topic below and practice with these activities :

Reading Practice

Read more and use these ideas to practice:

https://www.travelandleisure.com/attractions/museums-galleries/museums-with-virtual-tours

Speaking Practice

Practice with the following related questions from the real IELTS speaking exam:

- Should kids be taught art from a young age?

- Is it important for all people to get the opportunity to make art?

- Should art be sold or kept in museums for the public to see?

- Why is art sold for such large sums of money?

- What is the attitude to art in your country?

Writing Practice

Practice with the related graph below related to film production in 5 countries and then check with my sample answer:

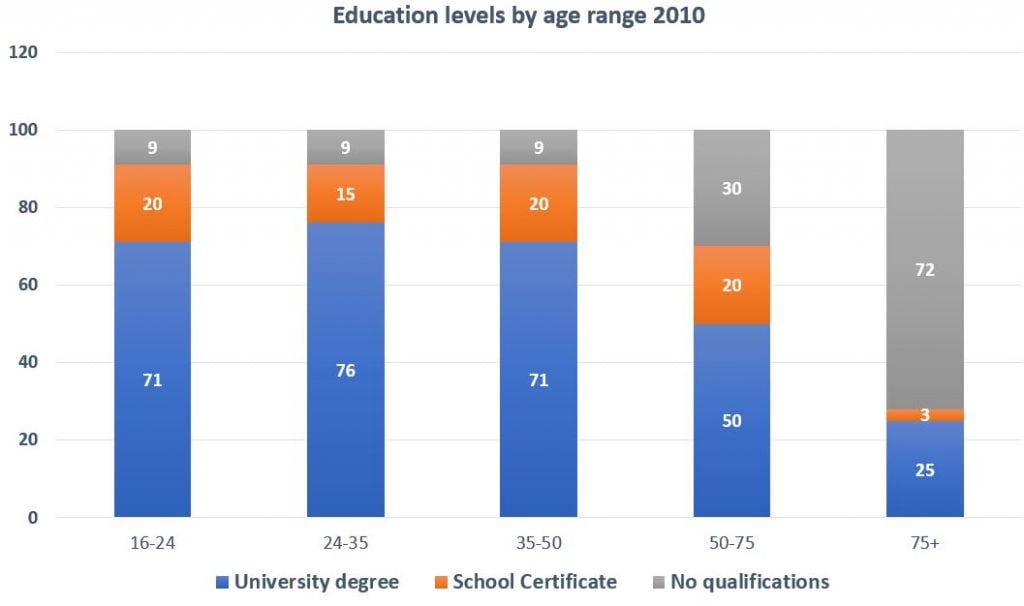

IELTS Task 1 Essay: Bar Chart (Education)

Recommended For You

Latest IELTS Writing Task 1 2024 (Graphs, Charts, Maps, Processes)

by Dave | Sample Answers | 147 Comments

These are the most recent/latest IELTS Writing Task 1 Task topics and questions starting in 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, and continuing into 2024. ...

Recent IELTS Writing Topics and Questions 2024

by Dave | Sample Answers | 342 Comments

Read here all the newest IELTS questions and topics from 2024 and previous years with sample answers/essays. Be sure to check out my ...

Find my Newest IELTS Post Here – Updated Daily!

by Dave | IELTS FAQ | 18 Comments

IELTS Essay Task 1: Exports Table

by Dave | Sample Answers | 6 Comments

This is an IELTS writing task 1 sample answer essay on the topic of an exports table in Hong Kong. Please consider supporting ...

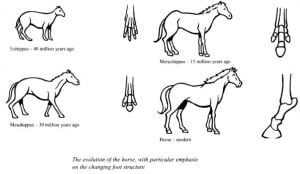

IELTS Essay Task 1: Horse Diagram

by Dave | Sample Answers | 0 Comment

This is an IELTS writing task 1 sample answer essay on the topic of the evolution of the horse and its hoof. Please ...

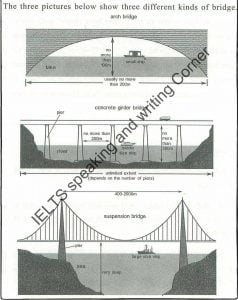

IELTS Essay Task 1: Bridges

by Dave | Sample Answers | 1 Comment

This is an IELTS writing task 1 sample answer essay on the topic of 3 different types of bridges. A really odd one ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The bar chart compares attendance figures for 4 museums in London over a five-month period from June to December. The overall popularity for all museums declined over this period of time with the notable exception of the British museum in which more people went there. Furthermore, the British Museum was also the most popular apart from June. The only two groups to see no change in attendance were the British Museum from June to July at approximately 420,000, and the Science Museum from July to August at exactly 400,000. For the other three months, the British Museum experienced a continued decrease from 720,000 in august to 460,000 at the end of the period. The trend for the History Museum was almost identical, but their numbers of visitors were always smaller as the gap widened dramatically: by 10,000 and 20,000 in the first two months, in turn, to less than 100,000 in august and 200,000 in the two final months. The science museum started at the highest point of June with 430,000 admissions, soaring to precisely 500,000 in September before a pullback to 300,000 in December. Finally, the national museum stayed at around 200,000 for the majority of the time described, remaining the least popular museum despite a peak of 380,000 in august.

Nice writing!

Really good comparison of the data and very accurate as well.

Careful with some slightly informal verbs and capitilization – otherwise really strong!

Exclusive Ebooks, PDFs and more from me!

Sign up for patreon.

Don't miss out!

"The highest quality materials anywhere on the internet! Dave improved my writing and vocabulary so much. Really affordable options you don't want to miss out on!"

Minh, Vietnam

Hi, I’m Dave! Welcome to my IELTS exclusive resources! Before you commit I want to explain very clearly why there’s no one better to help you learn about IELTS and improve your English at the same time... Read more

Patreon Exclusive Ebooks Available Now!

250 Years of The British Museum

The British Museum houses one of the world's largest and most comprehensive collections of cultural artifacts. And with the exception of two World Wars, when parts of the collection were evacuated, it has remained open since opening on January 15, 1759

- Disputed Artifacts

- StumbleUpon

- Del.i.cious

- Environment

- Road to Net Zero

- Art & Design

- Film & TV

- Music & On-stage

- Pop Culture

- Fashion & Beauty

- Home & Garden

- Things to do

- Combat Sports

- Horse Racing

- Beyond the Headlines

- Trending Middle East

- Business Extra

- Culture Bites

- Year of Elections

- Pocketful of Dirhams

- Books of My Life

- Iraq: 20 Years On

The repatriation debate: should museums return colonial artefacts?

The british museum is willing to loan out the objects it once pillaged (or bought), but is that enough.

Workmen deliver a portion of the Parthenon frieze, the socalled Elgin Marbles, to the British Museum in 1961. Greece has demanded the sculptures be returned to Athens. Getty

Imagine the British Museum in London without Egypt's Rosetta Stone. The city's Victoria and Albert Museum without Ethiopia's Maqdala treasures. Or the British capital's Natural History Museum without the scientific wonders that are Gibraltar's Neanderthal skulls.

After a summer of repatriation requests, the debate over the right of British museums to retain contested artefacts – objects that were often "removed" by Brit ish citizens from territories once ruled by the UK during its centuries as a colonial power – has gathered pace. In August, a Jamaican government minister requested that the British Museum hand back objects taken from the island when it was a UK colony. Only a month earlier, renowned Egyptian writer Ahdaf Soueif resigned her position as a member of the museum's Board of Trustees, citing its "immovability on issues of critical concern", including repatriation.

But speaking to The National , Soueif acknowledge s that "on the issue of restitution there is no one-size-fits-all solution".

"It has to be a case-by-case deliberation, and the solutions [must] stretch across the whole spectrum," sa ys Soueif, 69, who had served as a trustee since 2012 .

She says the spectrum ranged "from the object remaining where it is in the 'colonial' museum, but is provided with an appropriate context, to the object returning to the location where it was made – with lots of varied possibilities in between".

A history of disputes

Last month, a historic dispute between London and Athens over the so-called Elgin Marbles reared its head once more. Gree k Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis made a request to take the marbles from Britain on loan, with a view to putting them on show in 2021 to commemorate the Greek War of Independence, which began in 1821.

On display at the British Museum, this collection of classical Greek marble sculptures assumed their name after they were acquired by Britain's Lord Elgin from Greece in the early 1800s. But, according to media reports, the museum's precondition for any loan would be to acknowledge British ownership of the sculptures, which are about 2,500 years old and known in Greece as the Parthenon Marbles. But former Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras was critical of the notion, writing on Facebook that, far from asking to simply borrow them, Mitsotakis "should ask for the permanent return of the Parthenon Marbles".

As a result of its controversial colonial past, Britain has been the target of frequent and varied attempts to return objects seized from regions including the Middle East and Africa in eras gone by.

Take the Rosetta Stone, for instance. This ancient slab of granodiorite was discovered by French troops in 1799 after Napoleon Bonaparte's invasion of Egypt a year earlier. But after France's defeat by Britain in 1801, the stone fell into British hands. For more than 200 years, the artefact – inscribed in 196 BC and used to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs – has been exhibited at the British Museum.

But last year, Tarek Tawfik, director of Cairo's Grand Egyptian Museum, asked for it back.

"It would be great to have the Rosetta Stone back in Egypt but this is something that will still need a lot of discussion and co-operation," Tawfik told London newspaper the Evening Standard last year.

How the UK is behind when it comes to repatriation

Today, restitution efforts have become more pronounced as painful attempts by the UK to extricate itself from the European Union continue to stir debate over the country's place in the world and its colonial legacy.

British-Nigerian historian, broadcaster and filmmaker, David Olusoga, sa ys Britain ha s often lacked the sense of empathy necessary to understand why its former colonial territories long to see removed objects repatriated. "That is, to imagine what it is like to live in a country in which your national treasures – things that are of historical, cultural and sometimes religious and spiritual significance – are in the museums of other countries," says Olusoga, who personally advocates restitution. "Often as a result of unfair purchases or historic acts of violence, invasion and colonisation."

Olusoga, who is also a professor of public history at England's University of Manchester, sa ys Britain is "behind the curve" as far as repatriation is concerned. While museums across western Europe are filled with treasures lifted during the age of empire and colonisation, some nations have taken steps to right perceived wrongs of the past that took place under British rule.

In May, the German Historical Museum in Berlin announced that it was returning a 15th-century artefact known as the Stone Cross to Namibia. And late last year, a report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron called for museums in France to return artworks removed from African nations during the country's own colonial period.

Why it may not be such a great idea

But not everybody thinks restitution is such a good idea, relevant or even helpful. Tiffany Jenkins , author of Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended up in Museums, and Why They Should Stay There , has challenge d the idea that removed objects should be repatriated. She says that asking for artefacts to be returned to "repair the sins of colonisation" is an unwarranted "politicisation of culture".

She also contends that the clamour for restitution, not least from British critics of UK museums, has arisen from “an insecurity and crisis in the idea of what a museum is for”.

"In recent times, museums have been seen as simply reflecting the elite and offering nothing to anybody else," she explain s. "And the positive things that museums can do – that is showing different cultures and times and places to different people – have been abandoned, or people are not as confident about [their role]."

But a representative for the British Museum t ells The National that "internationally, the museum works extensively in partnership with museums across the globe to consider, understand and reflect … complicated shared histories".

"We lend many thousands of objects all over the world . For example, with regard to our work in Africa, we have committed to lending objects from the collection on a rotating basis to the planned new Royal Museum Benin in Benin City, within a three-year timeframe."

Soueif has no intention of returning to her British Museum role , saying that "the changes I think are necessary need a younger person who has a lot more time" . But she maintains that the debate about restitution should continue.

"There's a global conversation that has started and needs to be encouraged," she sa ys. "It's about the relationship of the south and the north, about cultural 'property' and what constitutes it, and about who gets to determine how objects with cultural or heritage significance are used . It's a conversation that needs to be entered into with an open mind and with a will to explore the past and the future. "

15 Best Museums in London, England in 2024

Updated : July 02, 2024

Michelle Palmer

Table of contents, free museums in london.

- Museums in London that cost

- FAQs About Museums in London

Museum lovers will be delighted by the abundance of museums in London. Whether your interest is in history, art or science, there is a museum for you, and many of the museums are free, an excellent feature for budget-conscious travelers and those traveling with kids. History museums in particular offer a wide range of topics. Some museums focus on the development of London, such as the National Maritime Museum, while others take an interesting look at recent history like the Museum of Brands. Art museums range from portraiture and modernism to exploration of British painters and more. Science enthusiasts should visit the London Natural History Museum to learn about prehistoric animals, geology and other topics. Be sure to visit some of the best museums in London, not only are they entertaining and educational, they are a great indoor activity.

At the best free museums in London, you'll find a range of exhibits about history, science and art — even a house museum made the list. These free museums are a fun way to experience culture in London on a budget and are some of the top things to do in London .

1. British Museum

The collection at the British Museum is wide and varied, if controversial due to Britain's history of imperialism and colonialism, but it is undeniably on of the top free museums in London. On three floors, you can see art and artifacts including textiles, paintings and pottery, to contemporary art from many different countries and regions. While here, you can see items from Egypt including sculptures from temples and tombs and even the Rosetta Stone, a slab which helped to translate Egyptian hieroglyphs. There are also galleries about Europe from the Middle Ages to the Age of Enlightenment and into the 20th century.

The British Museum is free to enter, except for some special exhibitions. You should book your tickets ahead of time to ensure entry to this busy museum. You can tour the museum on your own, download their app to purchase an audio guide or plan ahead for a tour with a guide. Some guided tours cost like the 90-minute Around the World Tour, while others are free, like the 70-minute Desire, Love and Identity Tour that explores LGBTQ history.

2. London Natural History Museum