Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

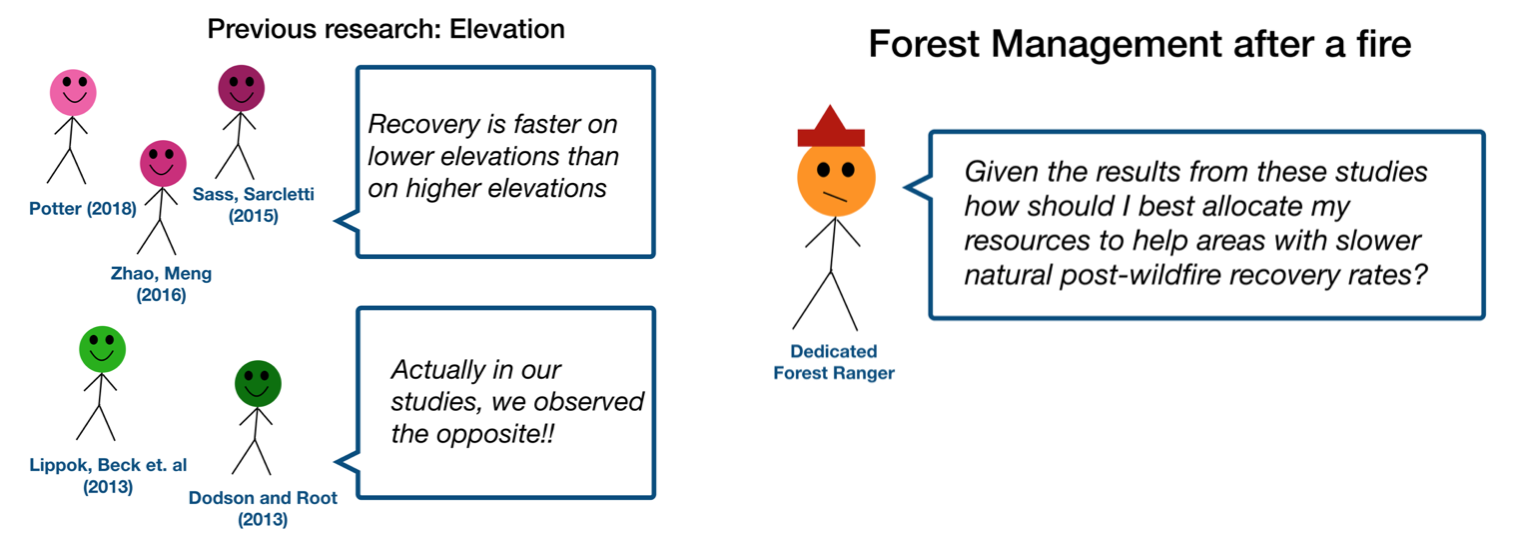

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.

Jacobs’s text references an essay on advancing human knowledge by the mathematician Warren Weaver. At the time, Weaver was director of the Rockefeller Foundation, in charge of funding basic research in the natural and medical sciences. Although the essay is titled ‘A Quarter Century in the Natural Sciences’ (1960) and appears at first blush to be merely a summation of one man’s career, it turns out to be something much bigger and more interesting: a meditation on the history of human beings seeking answers to big questions about the world. Weaver goes back to the 17th century to trace the origins of systematic research thinking, with enthusiasm and vivid anecdotes that make the process come alive. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, and is available free of charge via this link .

For those seeking a more in-depth, professional-level discussion of the logic of research design, the political scientist Harvey Starr provides insight in a compact format in the article ‘Cumulation from Proper Specification: Theory, Logic, Research Design, and “Nice” Laws’ (2005). Starr reviews the ‘research triad’, consisting of the interlinked considerations of formulating a question, selecting relevant theories and applying appropriate methods. The full text of the article, published in the scholarly journal Conflict Management and Peace Science , is available, free of charge, via this link .

Finally, the book Getting What You Came For (1992) by Robert Peters is not only an outstanding guide for anyone contemplating graduate school – from the application process onward – but it also includes several excellent chapters on planning and executing research, applicable across a wide variety of subject areas. It was an invaluable resource for me 25 years ago, and it remains in print with good reason; I recommend it to all my students, particularly Chapter 16 (‘The Thesis Topic: Finding It’), Chapter 17 (‘The Thesis Proposal’) and Chapter 18 (‘The Thesis: Writing It’).

Goals and motivation

How to do mental time travel

Feeling overwhelmed by the present moment? Find a connection to the longer view and a wiser perspective on what matters

by Richard Fisher

How to cope with climate anxiety

It’s normal to feel troubled by the climate crisis. These practices can help keep your response manageable and constructive

by Lucia Tecuta

Emerging therapies

How to use cooking as a form of therapy

No matter your culinary skills, spend some reflective time in the kitchen to nourish and renew your sense of self

by Charlotte Hastings

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.3 Managing Your Research Project

Learning objectives.

- Identify reasons for outlining the scope and sequence of a research project.

- Recognize the steps of the research writing process.

- Develop a plan for managing time and resources to complete the research project on time.

- Identify organizational tools and strategies to use in managing the project.

The prewriting you have completed so far has helped you begin to plan the content of your research paper—your topic, research questions, and preliminary thesis. It is equally important to plan out the process of researching and writing the paper. Although some types of writing assignments can be completed relatively quickly, developing a good research paper is a complex process that takes time. Breaking it into manageable steps is crucial. Review the steps outlined at the beginning of this chapter.

Steps to Writing a Research Paper

- Choose a topic.

- Schedule and plan time for research and writing.

- Conduct research.

- Organize research

- Draft your paper.

- Revise and edit your paper.

You have already completed step 1. In this section, you will complete step 2. The remaining steps fall under two broad categories—the research phase of the project (steps 3 and 4) and the writing phase (steps 5 and 6). Both phases present challenges. Understanding the tasks involved and allowing enough time to complete each task will help you complete your research paper on time with a minimal amount of stress.

Planning Your Project

Each step of a research project requires time and attention. Careful planning helps ensure that you will keep your project running smoothly and produce your best work. Set up a project schedule that shows when you will complete each step. Think about how you will complete each step and what project resources you will use. Resources may include anything from library databases and word-processing software to interview subjects and writing tutors.

To develop your schedule, use a calendar and work backward from the date your final draft is due. Generally, it is wise to divide half of the available time on the research phase of the project and half on the writing phase. For example, if you have a month to work, plan for two weeks for each phase. If you have a full semester, plan to begin research early and to start writing by the middle of the term. You might think that no one really works that far ahead, but try it. You will probably be pleased with the quality of your work and with the reduction in your stress level.

As you plan, break down major steps into smaller tasks if necessary. For example, step 3, conducting research, involves locating potential sources, evaluating their usefulness and reliability, reading, and taking notes. Defining these smaller tasks makes the project more manageable by giving you concrete goals to achieve.

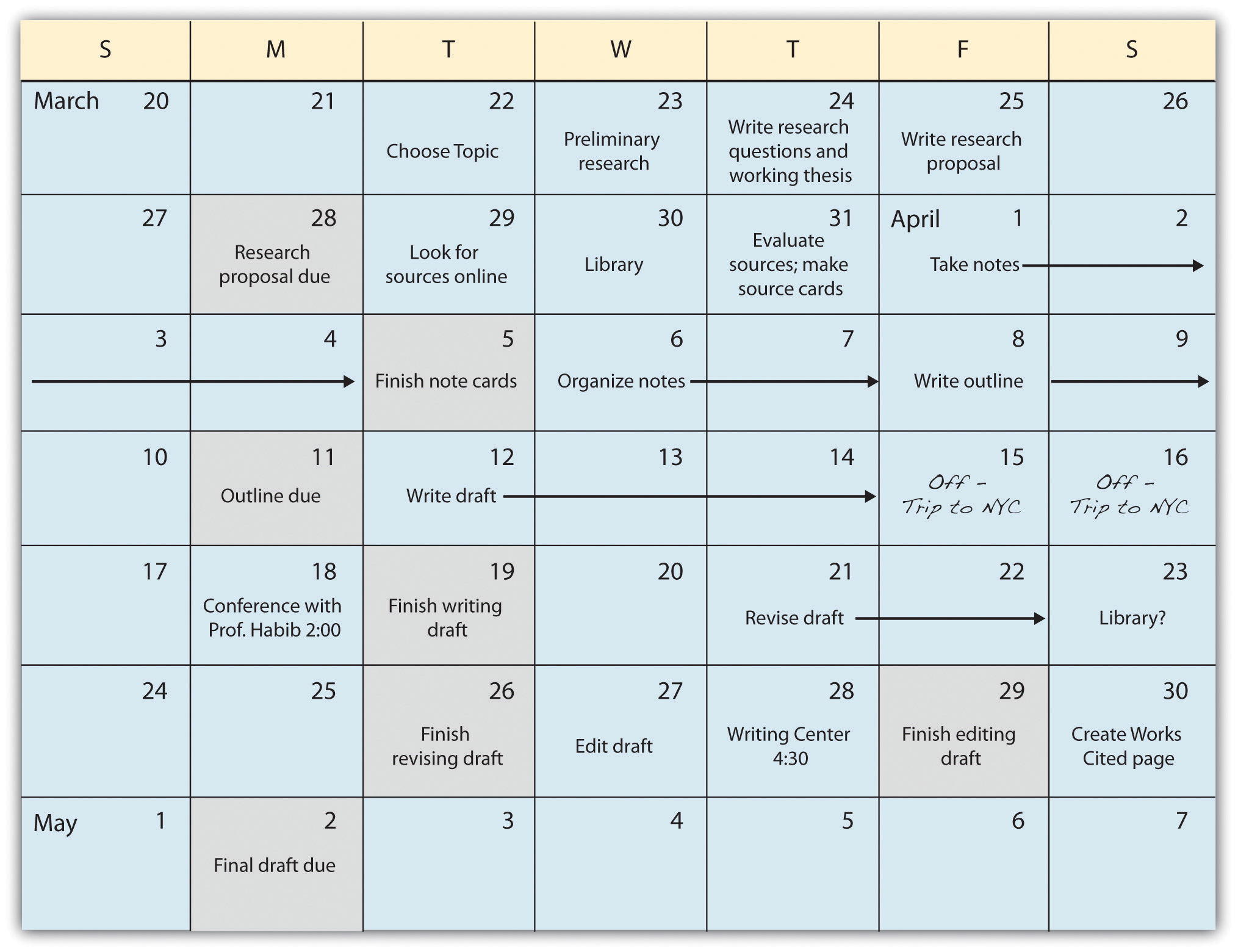

Jorge had six weeks to complete his research project. Working backward from a due date of May 2, he mapped out a schedule for completing his research by early April so that he would have ample time to write. Jorge chose to write his schedule in his weekly planner to help keep himself on track.

Review Jorge’s schedule. Key target dates are shaded. Note that Jorge planned times to use available resources by visiting the library and writing center and by meeting with his instructor.

- Working backward from the date your final draft is due, create a project schedule. You may choose to write a sequential list of tasks or record tasks on a calendar.

- Check your schedule to be sure that you have broken each step into smaller tasks and assigned a target completion date to each key task.

- Review your target dates to make sure they are realistic. Always allow a little more time than you think you will actually need.

Plan your schedule realistically, and consider other commitments that may sometimes take precedence. A business trip or family visit may mean that you are unable to work on the research project for a few days. Make the most of the time you have available. Plan for unexpected interruptions, but keep in mind that a short time away from the project may help you come back to it with renewed enthusiasm. Another strategy many writers find helpful is to finish each day’s work at a point when the next task is an easy one. That makes it easier to start again.

Writing at Work

When you create a project schedule at work, you set target dates for completing certain tasks and identify the resources you plan to use on the project. It is important to build in some flexibility. Materials may not be received on time because of a shipping delay. An employee on your team may be called away to work on a higher-priority project. Essential equipment may malfunction. You should always plan for the unexpected.

Staying Organized

Although setting up a schedule is easy, sticking to one is challenging. Even if you are the rare person who never procrastinates, unforeseen events may interfere with your ability to complete tasks on time. A self-imposed deadline may slip your mind despite your best intentions. Organizational tools—calendars, checklists, note cards, software, and so forth—can help you stay on track.

Throughout your project, organize both your time and your resources systematically. Review your schedule frequently and check your progress. It helps to post your schedule in a place where you will see it every day. Both personal and workplace e-mail systems usually include a calendar feature where you can record tasks, arrange to receive daily reminders, and check off completed tasks. Electronic devices such as smartphones have similar features.

Organize project documents in a binder or electronic folder, and label project documents and folders clearly. Use note cards or an electronic document to record bibliographical information for each source you plan to use in your paper. Tracking this information throughout the research process can save you hours of time when you create your references page.

Revisit the schedule you created in Note 11.42 “Exercise 1” . Transfer it into a format that will help you stay on track from day to day. You may wish to input it into your smartphone, write it in a weekly planner, post it by your desk, or have your e-mail account send you daily reminders. Consider setting up a buddy system with a classmate that will help you both stay on track.

Some people enjoy using the most up-to-date technology to help them stay organized. Other people prefer simple methods, such as crossing off items on a checklist. The key to staying organized is finding a system you like enough to use daily. The particulars of the method are not important as long as you are consistent.

Anticipating Challenges

Do any of these scenarios sound familiar? You have identified a book that would be a great resource for your project, but it is currently checked out of the library. You planned to interview a subject matter expert on your topic, but she calls to reschedule your meeting. You have begun writing your draft, but now you realize that you will need to modify your thesis and conduct additional research. Or you have finally completed your draft when your computer crashes, and days of hard work disappear in an instant.

These troubling situations are all too common. No matter how carefully you plan your schedule, you may encounter a glitch or setback. Managing your project effectively means anticipating potential problems, taking steps to minimize them where possible, and allowing time in your schedule to handle any setbacks.

Many times a situation becomes a problem due only to lack of planning. For example, if a book is checked out of your local library, it might be available through interlibrary loan, which usually takes a few days for the library staff to process. Alternatively, you might locate another, equally useful source. If you have allowed enough time for research, a brief delay will not become a major setback.

You can manage other potential problems by staying organized and maintaining a take-charge attitude. Take a minute each day to save a backup copy of your work on a portable hard drive. Maintain detailed note cards and source cards as you conduct research—doing so will make citing sources in your draft infinitely easier. If you run into difficulties with your research or your writing, ask your instructor for help, or make an appointment with a writing tutor.

Identify five potential problems you might encounter in the process of researching and writing your paper. Write them on a separate sheet of paper. For each problem, write at least one strategy for solving the problem or minimizing its effect on your project.

In the workplace, documents prepared at the beginning of a project often include a detailed plan for risk management. When you manage a project, it makes sense to anticipate and prepare for potential setbacks. For example, to roll out a new product line, a software development company must strive to complete tasks on a schedule in order to meet the new product release date. The project manager may need to adjust the project plan if one or more tasks fall behind schedule.

Key Takeaways

- To complete a research project successfully, a writer must carefully manage each phase of the process and break major steps into smaller tasks.

- Writers can plan a research project by setting up a schedule based on the deadline and by identifying useful project resources.

- Writers stay focused by using organizational tools that suit their needs.

- Anticipating and planning for potential setbacks can help writers avoid those setbacks or minimize their effect on the project schedule.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Get Started With a Research Project

Last Updated: October 3, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Chris Hadley, PhD . Chris Hadley, PhD is part of the wikiHow team and works on content strategy and data and analytics. Chris Hadley earned his PhD in Cognitive Psychology from UCLA in 2006. Chris' academic research has been published in numerous scientific journals. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 312,511 times.

You'll be required to undertake and complete research projects throughout your academic career and even, in many cases, as a member of the workforce. Don't worry if you feel stuck or intimidated by the idea of a research project, with care and dedication, you can get the project done well before the deadline!

Development and Foundation

- Don't hesitate while writing down ideas. You'll end up with some mental noise on the paper – silly or nonsensical phrases that your brain just pushes out. That's fine. Think of it as sweeping the cobwebs out of your attic. After a minute or two, better ideas will begin to form (and you might have a nice little laugh at your own expense in the meantime).

- Some instructors will even provide samples of previously successful topics if you ask for them. Just be careful that you don't end up stuck with an idea you want to do, but are afraid to do because you know someone else did it before.

- For example, if your research topic is “urban poverty,” you could look at that topic across ethnic or sexual lines, but you could also look into corporate wages, minimum wage laws, the cost of medical benefits, the loss of unskilled jobs in the urban core, and on and on. You could also try comparing and contrasting urban poverty with suburban or rural poverty, and examine things that might be different about both areas, such as diet and exercise levels, or air pollution.

- Think in terms of questions you want answered. A good research project should collect information for the purpose of answering (or at least attempting to answer) a question. As you review and interconnect topics, you'll think of questions that don't seem to have clear answers yet. These questions are your research topics.

- Don't limit yourself to libraries and online databases. Think in terms of outside resources as well: primary sources, government agencies, even educational TV programs. If you want to know about differences in animal population between public land and an Indian reservation, call the reservation and see if you can speak to their department of fish and wildlife.

- If you're planning to go ahead with original research, that's great – but those techniques aren't covered in this article. Instead, speak with qualified advisors and work with them to set up a thorough, controlled, repeatable process for gathering information.

- If your plan comes down to “researching the topic,” and there aren't any more specific things you can say about it, write down the types of sources you plan to use instead: books (library or private?), magazines (which ones?), interviews, and so on. Your preliminary research should have given you a solid idea of where to begin.

Expanding Your Idea with Research

- It's generally considered more convincing to source one item from three different authors who all agree on it than it is to rely too heavily on one book. Go for quantity at least as much as quality. Be sure to check citations, endnotes, and bibliographies to get more potential sources (and see whether or not all your authors are just quoting the same, older author).

- Writing down your sources and any other relevant details (such as context) around your pieces of information right now will save you lots of trouble in the future.

- Use many different queries to get the database results you want. If one phrasing or a particular set of words doesn't yield useful results, try rephrasing it or using synonymous terms. Online academic databases tend to be dumber than the sum of their parts, so you'll have to use tangentially related terms and inventive language to get all the results you want.

- If it's sensible, consider heading out into the field and speaking to ordinary people for their opinions. This isn't always appropriate (or welcomed) in a research project, but in some cases, it can provide you with some excellent perspective for your research.

- Review cultural artifacts as well. In many areas of study, there's useful information on attitudes, hopes, and/or concerns of people in a particular time and place contained within the art, music, and writing they produced. One has only to look at the woodblock prints of the later German Expressionists, for example, to understand that they lived in a world they felt was often dark, grotesque, and hopeless. Song lyrics and poetry can likewise express strong popular attitudes.

Expert Q&A

- Start early. The foundation of a great research project is the research, which takes time and patience to gather even if you aren't performing any original research of your own. Set aside time for it whenever you can, at least until your initial gathering phase is complete. Past that point, the project should practically come together on its own. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- When in doubt, write more, rather than less. It's easier to pare down and reorganize an overabundance of information than it is to puff up a flimsy core of facts and anecdotes. Thanks Helpful 1 Not Helpful 0

- Respect the wishes of others. Unless you're a research journalist, it's vital that you yield to the wishes and requests of others before engaging in original research, even if it's technically ethical. Many older American Indians, for instance, harbor a great deal of cultural resentment towards social scientists who visit reservations for research, even those invited by tribal governments for important reasons such as language revitalization. Always tread softly whenever you're out of your element, and only work with those who want to work with you. Thanks Helpful 8 Not Helpful 2

- Be mindful of ethical concerns. Especially if you plan to use original research, there are very stringent ethical guidelines that must be followed for any credible academic body to accept it. Speak to an advisor (such as a professor) about what you plan to do and what steps you should take to verify that it will be ethical. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/research/research_paper.html

- ↑ https://www.nhcc.edu/academics/library/doing-library-research/basic-steps-research-process

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185905

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/student-resources/writing-speaking-resources/using-an-interview-in-a-research-paper

- ↑ https://www.science.org/content/article/how-review-paper

About This Article

The easiest way to get started with a research project is to use your notes and other materials to come up with topics that interest you. Research your favorite topic to see if it can be developed, and then refine it into a research question. Begin thoroughly researching, and collect notes and sources. To learn more about finding reliable and helpful sources while you're researching, continue reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jun 30, 2016

Did this article help you?

Maooz Asghar

Aug 14, 2016

Jun 27, 2016

Calvin Kiyondi

Apr 24, 2017

Nov 2, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Education During Coronavirus

A Smithsonian magazine special report

Science | June 15, 2020

Seventy-Five Scientific Research Projects You Can Contribute to Online

From astrophysicists to entomologists, many researchers need the help of citizen scientists to sift through immense data collections

:focal(300x157:301x158)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/ca/e2ca665f-77b7-4ba2-8cd2-46f38cbf2b60/citizen_science_mobile.png)

Rachael Lallensack

Former Assistant Editor, Science and Innovation

If you find yourself tired of streaming services, reading the news or video-chatting with friends, maybe you should consider becoming a citizen scientist. Though it’s true that many field research projects are paused , hundreds of scientists need your help sifting through wildlife camera footage and images of galaxies far, far away, or reading through diaries and field notes from the past.

Plenty of these tools are free and easy enough for children to use. You can look around for projects yourself on Smithsonian Institution’s citizen science volunteer page , National Geographic ’s list of projects and CitizenScience.gov ’s catalog of options. Zooniverse is a platform for online-exclusive projects , and Scistarter allows you to restrict your search with parameters, including projects you can do “on a walk,” “at night” or “on a lunch break.”

To save you some time, Smithsonian magazine has compiled a collection of dozens of projects you can take part in from home.

American Wildlife

If being home has given you more time to look at wildlife in your own backyard, whether you live in the city or the country, consider expanding your view, by helping scientists identify creatures photographed by camera traps. Improved battery life, motion sensors, high-resolution and small lenses have made camera traps indispensable tools for conservation.These cameras capture thousands of images that provide researchers with more data about ecosystems than ever before.

Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s eMammal platform , for example, asks users to identify animals for conservation projects around the country. Currently, eMammal is being used by the Woodland Park Zoo ’s Seattle Urban Carnivore Project, which studies how coyotes, foxes, raccoons, bobcats and other animals coexist with people, and the Washington Wolverine Project, an effort to monitor wolverines in the face of climate change. Identify urban wildlife for the Chicago Wildlife Watch , or contribute to wilderness projects documenting North American biodiversity with The Wilds' Wildlife Watch in Ohio , Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild in Minnesota , Michigan ZoomIN , Western Montana Wildlife and Snapshot Wisconsin .

"Spend your time at home virtually exploring the Minnesota backwoods,” writes the lead researcher of the Cedar Creek: Eyes on the Wild project. “Help us understand deer dynamics, possum populations, bear behavior, and keep your eyes peeled for elusive wolves!"

If being cooped up at home has you daydreaming about traveling, Snapshot Safari has six active animal identification projects. Try eyeing lions, leopards, cheetahs, wild dogs, elephants, giraffes, baobab trees and over 400 bird species from camera trap photos taken in South African nature reserves, including De Hoop Nature Reserve and Madikwe Game Reserve .

With South Sudan DiversityCam , researchers are using camera traps to study biodiversity in the dense tropical forests of southwestern South Sudan. Part of the Serenegeti Lion Project, Snapshot Serengeti needs the help of citizen scientists to classify millions of camera trap images of species traveling with the wildebeest migration.

Classify all kinds of monkeys with Chimp&See . Count, identify and track giraffes in northern Kenya . Watering holes host all kinds of wildlife, but that makes the locales hotspots for parasite transmission; Parasite Safari needs volunteers to help figure out which animals come in contact with each other and during what time of year.

Mount Taranaki in New Zealand is a volcanic peak rich in native vegetation, but native wildlife, like the North Island brown kiwi, whio/blue duck and seabirds, are now rare—driven out by introduced predators like wild goats, weasels, stoats, possums and rats. Estimate predator species compared to native wildlife with Taranaki Mounga by spotting species on camera trap images.

The Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) Instant Wild app has a dozen projects showcasing live images and videos of wildlife around the world. Look for bears, wolves and lynx in Croatia ; wildcats in Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula ; otters in Hampshire, England ; and both black and white rhinos in the Lewa-Borana landscape in Kenya.

Under the Sea

Researchers use a variety of technologies to learn about marine life and inform conservation efforts. Take, for example, Beluga Bits , a research project focused on determining the sex, age and pod size of beluga whales visiting the Churchill River in northern Manitoba, Canada. With a bit of training, volunteers can learn how to differentiate between a calf, a subadult (grey) or an adult (white)—and even identify individuals using scars or unique pigmentation—in underwater videos and images. Beluga Bits uses a “ beluga boat ,” which travels around the Churchill River estuary with a camera underneath it, to capture the footage and collect GPS data about the whales’ locations.

Many of these online projects are visual, but Manatee Chat needs citizen scientists who can train their ear to decipher manatee vocalizations. Researchers are hoping to learn what calls the marine mammals make and when—with enough practice you might even be able to recognize the distinct calls of individual animals.

Several groups are using drone footage to monitor seal populations. Seals spend most of their time in the water, but come ashore to breed. One group, Seal Watch , is analyzing time-lapse photography and drone images of seals in the British territory of South Georgia in the South Atlantic. A team in Antarctica captured images of Weddell seals every ten minutes while the seals were on land in spring to have their pups. The Weddell Seal Count project aims to find out what threats—like fishing and climate change—the seals face by monitoring changes in their population size. Likewise, the Año Nuevo Island - Animal Count asks volunteers to count elephant seals, sea lions, cormorants and more species on a remote research island off the coast of California.

With Floating Forests , you’ll sift through 40 years of satellite images of the ocean surface identifying kelp forests, which are foundational for marine ecosystems, providing shelter for shrimp, fish and sea urchins. A project based in southwest England, Seagrass Explorer , is investigating the decline of seagrass beds. Researchers are using baited cameras to spot commercial fish in these habitats as well as looking out for algae to study the health of these threatened ecosystems. Search for large sponges, starfish and cold-water corals on the deep seafloor in Sweden’s first marine park with the Koster seafloor observatory project.

The Smithsonian Environmental Research Center needs your help spotting invasive species with Invader ID . Train your eye to spot groups of organisms, known as fouling communities, that live under docks and ship hulls, in an effort to clean up marine ecosystems.

If art history is more your speed, two Dutch art museums need volunteers to start “ fishing in the past ” by analyzing a collection of paintings dating from 1500 to 1700. Each painting features at least one fish, and an interdisciplinary research team of biologists and art historians wants you to identify the species of fish to make a clearer picture of the “role of ichthyology in the past.”

Interesting Insects

Notes from Nature is a digitization effort to make the vast resources in museums’ archives of plants and insects more accessible. Similarly, page through the University of California Berkeley’s butterfly collection on CalBug to help researchers classify these beautiful critters. The University of Michigan Museum of Zoology has already digitized about 300,000 records, but their collection exceeds 4 million bugs. You can hop in now and transcribe their grasshopper archives from the last century . Parasitic arthropods, like mosquitos and ticks, are known disease vectors; to better locate these critters, the Terrestrial Parasite Tracker project is working with 22 collections and institutions to digitize over 1.2 million specimens—and they’re 95 percent done . If you can tolerate mosquito buzzing for a prolonged period of time, the HumBug project needs volunteers to train its algorithm and develop real-time mosquito detection using acoustic monitoring devices. It’s for the greater good!

For the Birders

Birdwatching is one of the most common forms of citizen science . Seeing birds in the wilderness is certainly awe-inspiring, but you can birdwatch from your backyard or while walking down the sidewalk in big cities, too. With Cornell University’s eBird app , you can contribute to bird science at any time, anywhere. (Just be sure to remain a safe distance from wildlife—and other humans, while we social distance ). If you have safe access to outdoor space—a backyard, perhaps—Cornell also has a NestWatch program for people to report observations of bird nests. Smithsonian’s Migratory Bird Center has a similar Neighborhood Nest Watch program as well.

Birdwatching is easy enough to do from any window, if you’re sheltering at home, but in case you lack a clear view, consider these online-only projects. Nest Quest currently has a robin database that needs volunteer transcribers to digitize their nest record cards.

You can also pitch in on a variety of efforts to categorize wildlife camera images of burrowing owls , pelicans , penguins (new data coming soon!), and sea birds . Watch nest cam footage of the northern bald ibis or greylag geese on NestCams to help researchers learn about breeding behavior.

Or record the coloration of gorgeous feathers across bird species for researchers at London’s Natural History Museum with Project Plumage .

Pretty Plants

If you’re out on a walk wondering what kind of plants are around you, consider downloading Leafsnap , an electronic field guide app developed by Columbia University, the University of Maryland and the Smithsonian Institution. The app has several functions. First, it can be used to identify plants with its visual recognition software. Secondly, scientists can learn about the “ the ebb and flow of flora ” from geotagged images taken by app users.

What is older than the dinosaurs, survived three mass extinctions and still has a living relative today? Ginko trees! Researchers at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are studying ginko trees and fossils to understand millions of years of plant evolution and climate change with the Fossil Atmospheres project . Using Zooniverse, volunteers will be trained to identify and count stomata, which are holes on a leaf’s surface where carbon dioxide passes through. By counting these holes, or quantifying the stomatal index, scientists can learn how the plants adapted to changing levels of carbon dioxide. These results will inform a field experiment conducted on living trees in which a scientist is adjusting the level of carbon dioxide for different groups.

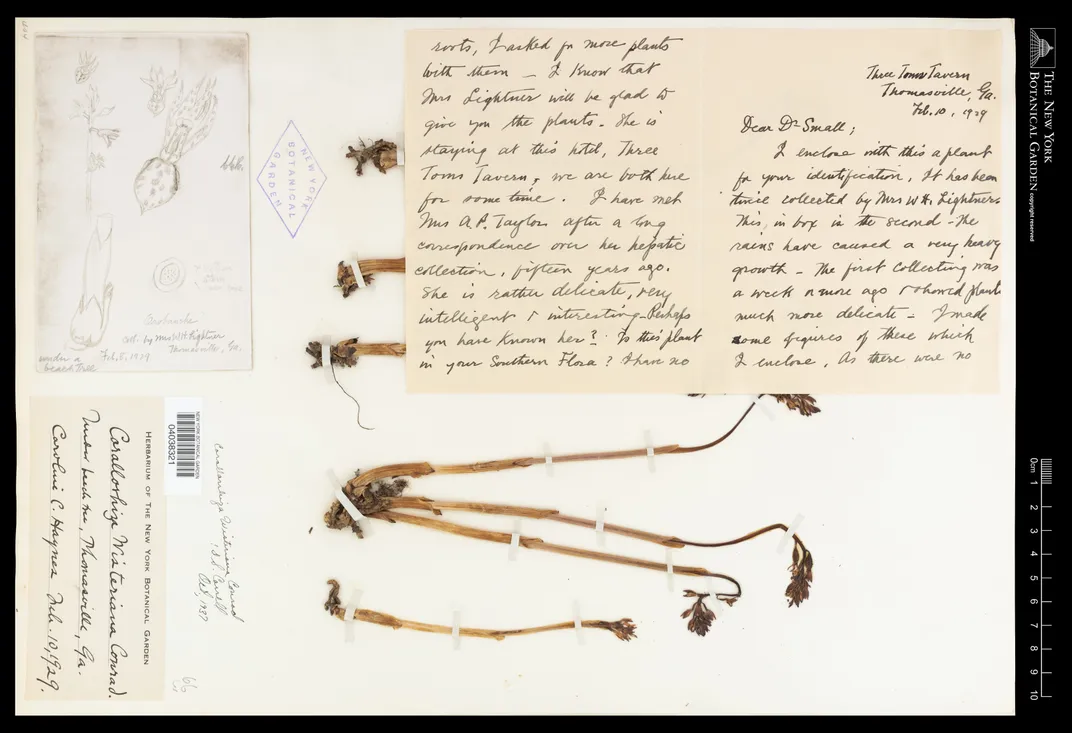

Help digitize and categorize millions of botanical specimens from natural history museums, research institutions and herbaria across the country with the Notes from Nature Project . Did you know North America is home to a variety of beautiful orchid species? Lend botanists a handby typing handwritten labels on pressed specimens or recording their geographic and historic origins for the New York Botanical Garden’s archives. Likewise, the Southeastern U.S. Biodiversity project needs assistance labeling pressed poppies, sedums, valerians, violets and more. Groups in California , Arkansas , Florida , Texas and Oklahoma all invite citizen scientists to partake in similar tasks.

Historic Women in Astronomy

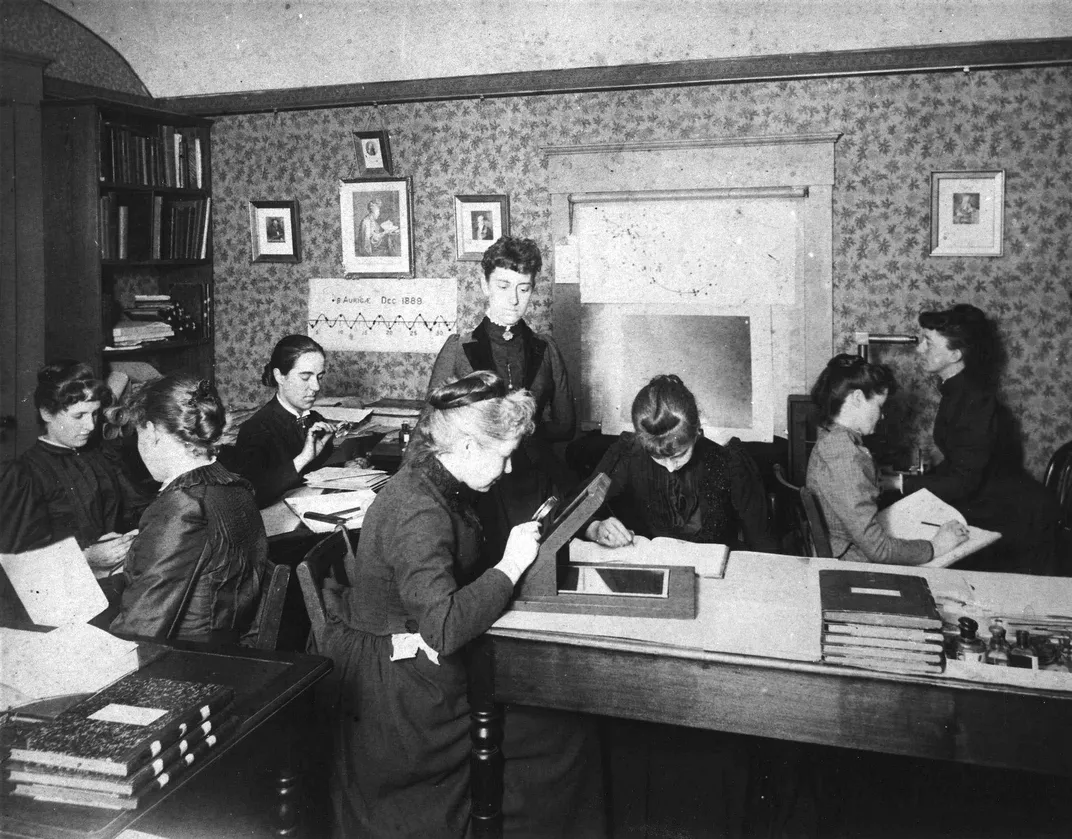

Become a transcriber for Project PHaEDRA and help researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics preserve the work of Harvard’s women “computers” who revolutionized astronomy in the 20th century. These women contributed more than 130 years of work documenting the night sky, cataloging stars, interpreting stellar spectra, counting galaxies, and measuring distances in space, according to the project description .

More than 2,500 notebooks need transcription on Project PhaEDRA - Star Notes . You could start with Annie Jump Cannon , for example. In 1901, Cannon designed a stellar classification system that astronomers still use today. Cecilia Payne discovered that stars are made primarily of hydrogen and helium and can be categorized by temperature. Two notebooks from Henrietta Swan Leavitt are currently in need of transcription. Leavitt, who was deaf, discovered the link between period and luminosity in Cepheid variables, or pulsating stars, which “led directly to the discovery that the Universe is expanding,” according to her bio on Star Notes .

Volunteers are also needed to transcribe some of these women computers’ notebooks that contain references to photographic glass plates . These plates were used to study space from the 1880s to the 1990s. For example, in 1890, Williamina Flemming discovered the Horsehead Nebula on one of these plates . With Star Notes, you can help bridge the gap between “modern scientific literature and 100 years of astronomical observations,” according to the project description . Star Notes also features the work of Cannon, Leavitt and Dorrit Hoffleit , who authored the fifth edition of the Bright Star Catalog, which features 9,110 of the brightest stars in the sky.

Microscopic Musings

Electron microscopes have super-high resolution and magnification powers—and now, many can process images automatically, allowing teams to collect an immense amount of data. Francis Crick Institute’s Etch A Cell - Powerhouse Hunt project trains volunteers to spot and trace each cell’s mitochondria, a process called manual segmentation. Manual segmentation is a major bottleneck to completing biological research because using computer systems to complete the work is still fraught with errors and, without enough volunteers, doing this work takes a really long time.

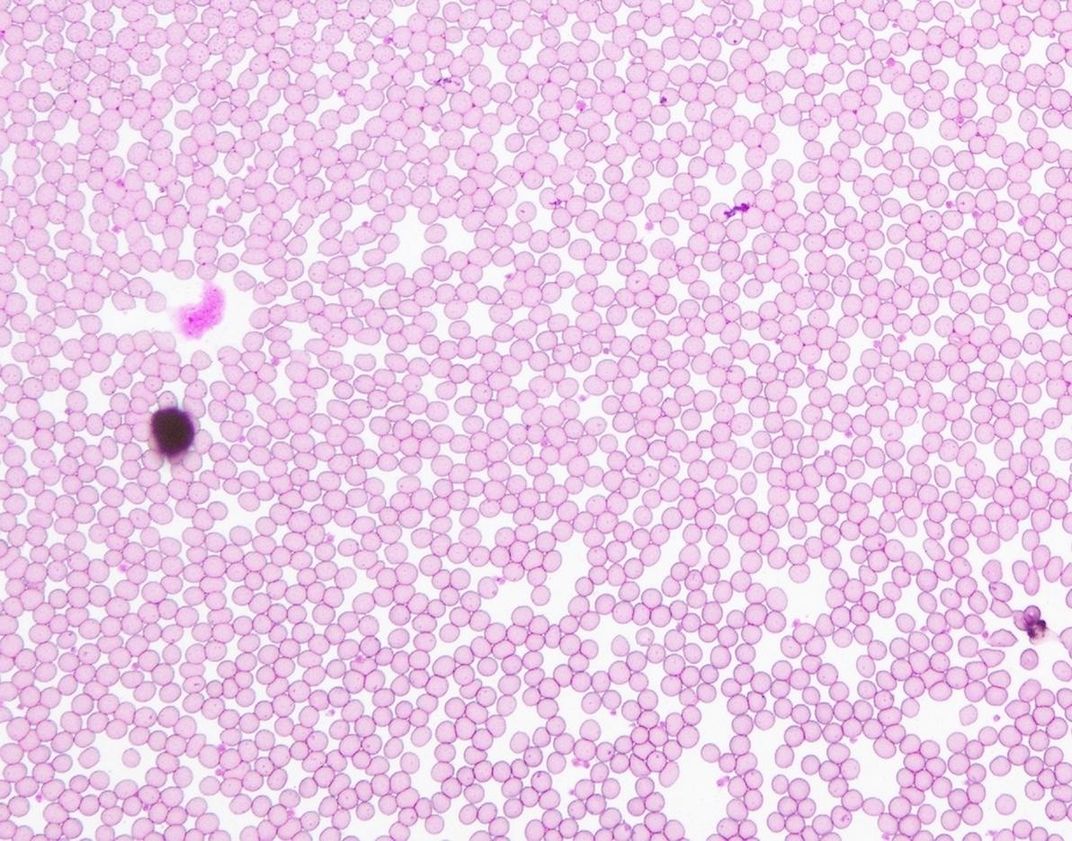

For the Monkey Health Explorer project, researchers studying the social behavior of rhesus monkeys on the tiny island Cayo Santiago off the southeastern coast of Puerto Rico need volunteers to analyze the monkeys’ blood samples. Doing so will help the team understand which monkeys are sick and which are healthy, and how the animals’ health influences behavioral changes.

Using the Zooniverse’s app on a phone or tablet, you can become a “ Science Scribbler ” and assist researchers studying how Huntington disease may change a cell’s organelles. The team at the United Kingdom's national synchrotron , which is essentially a giant microscope that harnesses the power of electrons, has taken highly detailed X-ray images of the cells of Huntington’s patients and needs help identifying organelles, in an effort to see how the disease changes their structure.

Oxford University’s Comprehensive Resistance Prediction for Tuberculosis: an International Consortium—or CRyPTIC Project , for short, is seeking the aid of citizen scientists to study over 20,000 TB infection samples from around the world. CRyPTIC’s citizen science platform is called Bash the Bug . On the platform, volunteers will be trained to evaluate the effectiveness of antibiotics on a given sample. Each evaluation will be checked by a scientist for accuracy and then used to train a computer program, which may one day make this process much faster and less labor intensive.

Out of This World

If you’re interested in contributing to astronomy research from the comfort and safety of your sidewalk or backyard, check out Globe at Night . The project monitors light pollution by asking users to try spotting constellations in the night sky at designated times of the year . (For example, Northern Hemisphere dwellers should look for the Bootes and Hercules constellations from June 13 through June 22 and record the visibility in Globe at Night’s app or desktop report page .)

For the amateur astrophysicists out there, the opportunities to contribute to science are vast. NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission is asking for volunteers to search for new objects at the edges of our solar system with the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project .

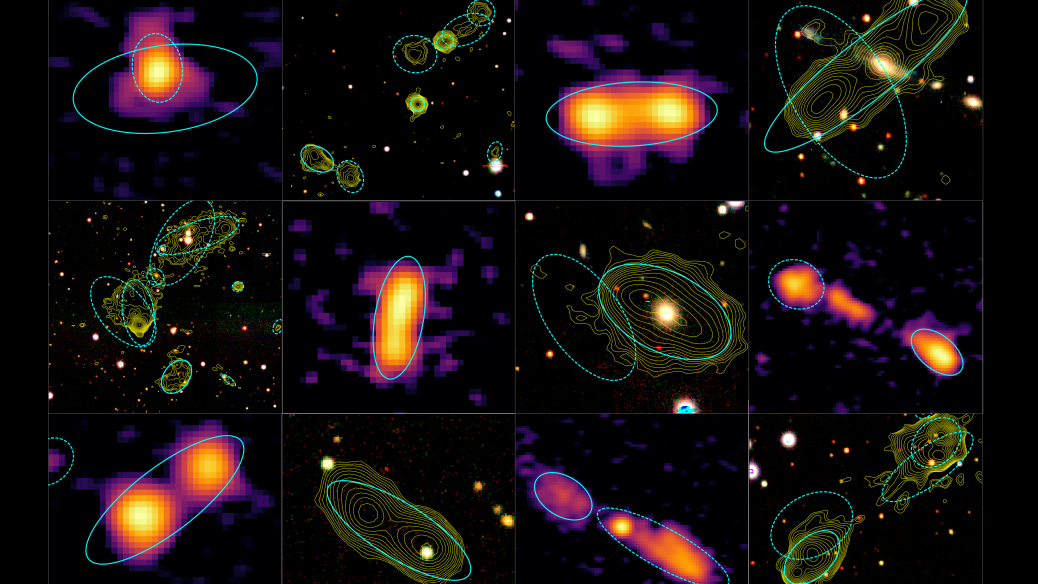

Galaxy Zoo on Zooniverse and its mobile app has operated online citizen science projects for the past decade. According to the project description, there are roughly one hundred billion galaxies in the observable universe. Surprisingly, identifying different types of galaxies by their shape is rather easy. “If you're quick, you may even be the first person to see the galaxies you're asked to classify,” the team writes.

With Radio Galaxy Zoo: LOFAR , volunteers can help identify supermassive blackholes and star-forming galaxies. Galaxy Zoo: Clump Scout asks users to look for young, “clumpy” looking galaxies, which help astronomers understand galaxy evolution.

If current events on Earth have you looking to Mars, perhaps you’d be interested in checking out Planet Four and Planet Four: Terrains —both of which task users with searching and categorizing landscape formations on Mars’ southern hemisphere. You’ll scroll through images of the Martian surface looking for terrain types informally called “spiders,” “baby spiders,” “channel networks” and “swiss cheese.”

Gravitational waves are telltale ripples in spacetime, but they are notoriously difficult to measure. With Gravity Spy , citizen scientists sift through data from Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO , detectors. When lasers beamed down 2.5-mile-long “arms” at these facilities in Livingston, Louisiana and Hanford, Washington are interrupted, a gravitational wave is detected. But the detectors are sensitive to “glitches” that, in models, look similar to the astrophysical signals scientists are looking for. Gravity Spy teaches citizen scientists how to identify fakes so researchers can get a better view of the real deal. This work will, in turn, train computer algorithms to do the same.

Similarly, the project Supernova Hunters needs volunteers to clear out the “bogus detections of supernovae,” allowing researchers to track the progression of actual supernovae. In Hubble Space Telescope images, you can search for asteroid tails with Hubble Asteroid Hunter . And with Planet Hunters TESS , which teaches users to identify planetary formations, you just “might be the first person to discover a planet around a nearby star in the Milky Way,” according to the project description.

Help astronomers refine prediction models for solar storms, which kick up dust that impacts spacecraft orbiting the sun, with Solar Stormwatch II. Thanks to the first iteration of the project, astronomers were able to publish seven papers with their findings.

With Mapping Historic Skies , identify constellations on gorgeous celestial maps of the sky covering a span of 600 years from the Adler Planetarium collection in Chicago. Similarly, help fill in the gaps of historic astronomy with Astronomy Rewind , a project that aims to “make a holistic map of images of the sky.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/rachael.png)

Rachael Lallensack | READ MORE

Rachael Lallensack is the former assistant web editor for science and innovation at Smithsonian .

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- Privacy Policy

Home » Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and Examples

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Scope of the Research

Scope of research refers to the range of topics, areas, and subjects that a research project intends to cover. It is the extent and limitations of the study, defining what is included and excluded in the research.

The scope of a research project depends on various factors, such as the research questions , objectives , methodology, and available resources. It is essential to define the scope of the research project clearly to avoid confusion and ensure that the study addresses the intended research questions.

How to Write Scope of the Research

Writing the scope of the research involves identifying the specific boundaries and limitations of the study. Here are some steps you can follow to write a clear and concise scope of the research:

- Identify the research question: Start by identifying the specific question that you want to answer through your research . This will help you focus your research and define the scope more clearly.

- Define the objectives: Once you have identified the research question, define the objectives of your study. What specific goals do you want to achieve through your research?

- Determine the population and sample: Identify the population or group of people that you will be studying, as well as the sample size and selection criteria. This will help you narrow down the scope of your research and ensure that your findings are applicable to the intended audience.

- Identify the variables: Determine the variables that will be measured or analyzed in your research. This could include demographic variables, independent variables , dependent variables , or any other relevant factors.

- Define the timeframe: Determine the timeframe for your study, including the start and end date, as well as any specific time intervals that will be measured.

- Determine the geographical scope: If your research is location-specific, define the geographical scope of your study. This could include specific regions, cities, or neighborhoods that you will be focusing on.

- Outline the limitations: Finally, outline any limitations or constraints of your research, such as time, resources, or access to data. This will help readers understand the scope and applicability of your research findings.

Examples of the Scope of the Research

Some Examples of the Scope of the Research are as follows:

Title : “Investigating the impact of artificial intelligence on job automation in the IT industry”

Scope of Research:

This study aims to explore the impact of artificial intelligence on job automation in the IT industry. The research will involve a qualitative analysis of job postings, identifying tasks that can be automated using AI. The study will also assess the potential implications of job automation on the workforce, including job displacement, job creation, and changes in job requirements.

Title : “Developing a machine learning model for predicting cyberattacks on corporate networks”

This study will develop a machine learning model for predicting cyberattacks on corporate networks. The research will involve collecting and analyzing network traffic data, identifying patterns and trends that are indicative of cyberattacks. The study aims to build an accurate and reliable predictive model that can help organizations identify and prevent cyberattacks before they occur.

Title: “Assessing the usability of a mobile app for managing personal finances”

This study will assess the usability of a mobile app for managing personal finances. The research will involve conducting a usability test with a group of participants, evaluating the app’s ease of use, efficiency, and user satisfaction. The study aims to identify areas of the app that need improvement, and to provide recommendations for enhancing its usability and user experience.

Title : “Exploring the effects of mindfulness meditation on stress reduction among college students”

This study aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on reducing stress levels among college students. The research will involve a randomized controlled trial with two groups: a treatment group that receives mindfulness meditation training and a control group that receives no intervention. The study will examine changes in stress levels, as measured by self-report questionnaires, before and after the intervention.

Title: “Investigating the impact of social media on body image dissatisfaction among young adults”

This study will explore the relationship between social media use and body image dissatisfaction among young adults. The research will involve a cross-sectional survey of participants aged 18-25, assessing their social media use, body image perceptions, and self-esteem. The study aims to identify any correlations between social media use and body image dissatisfaction, and to determine if certain social media platforms or types of content are particularly harmful.

When to Write Scope of the Research

Here is a guide on When to Write the Scope of the Research:

- Before starting your research project, it’s important to clearly define the scope of your study. This will help you stay focused on your research question and avoid getting sidetracked by irrelevant information.

- The scope of the research should be determined by the research question or problem statement. It should outline what you intend to investigate and what you will not be investigating.

- The scope should also take into consideration any limitations of the study, such as time, resources, or access to data. This will help you realistically plan and execute your research.

- Writing the scope of the research early in the research process can also help you refine your research question and identify any gaps in the existing literature that your study can address.

- It’s important to revisit the scope of the research throughout the research process to ensure that you stay on track and make any necessary adjustments.

- The scope of the research should be clearly communicated in the research proposal or study protocol to ensure that all stakeholders are aware of the research objectives and limitations.

- The scope of the research should also be reflected in the research design, methods, and analysis plan. This will ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner that is aligned with the research objectives.

- The scope of the research should be written in a clear and concise manner, using language that is accessible to all stakeholders, including those who may not be familiar with the research topic or methodology.

- When writing the scope of the research, it’s important to be transparent about any assumptions or biases that may influence the research findings. This will help ensure that the research is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner.

- The scope of the research should be reviewed and approved by the research supervisor, committee members, or other relevant stakeholders. This will ensure that the research is feasible, relevant, and contributes to the field of study.

- Finally, the scope of the research should be clearly stated in the research report or dissertation to provide context for the research findings and conclusions. This will help readers understand the significance of the research and its contribution to the field of study.

Purpose of Scope of the Research

Purposes of Scope of the Research are as follows:

- Defines the boundaries and extent of the study.

- Determines the specific objectives and research questions to be addressed.

- Provides direction and focus for the research.

- Helps to identify the relevant theories, concepts, and variables to be studied.

- Enables the researcher to select the appropriate research methodology and techniques.

- Allows for the allocation of resources (time, money, personnel) to the research.

- Establishes the criteria for the selection of the sample and data collection methods.

- Facilitates the interpretation and generalization of the results.

- Ensures the ethical considerations and constraints are addressed.

- Provides a framework for the presentation and dissemination of the research findings.

Advantages of Scope of the Research

Here are some advantages of having a well-defined scope of research:

- Provides clarity and focus: Defining the scope of research helps to provide clarity and focus to the study. This ensures that the research stays on track and does not deviate from its intended purpose.

- Helps to manage resources: Knowing the scope of research allows researchers to allocate resources effectively. This includes managing time, budget, and personnel required to conduct the study.

- Improves the quality of research: A well-defined scope of research helps to ensure that the study is designed to achieve specific objectives. This helps to improve the quality of the research by reducing the likelihood of errors or bias.

- Facilitates communication: A clear scope of research enables researchers to communicate the goals and objectives of the study to stakeholders, such as funding agencies or participants. This facilitates understanding and enhances cooperation.

- Enables replication : A well-defined scope of research makes it easier to replicate the study in the future. This allows other researchers to validate the findings and build upon them, leading to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Increases the relevance of research: Defining the scope of research helps to ensure that the study is relevant to the problem or issue being investigated. This increases the likelihood that the findings will be useful and applicable to real-world situations.