Systematic Reviews and Meta Analysis

- Getting Started

- Guides and Standards

- Review Protocols

- Databases and Sources

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Controlled Clinical Trials

- Observational Designs

- Tests of Diagnostic Accuracy

- Software and Tools

- Where do I get all those articles?

- Collaborations

- EPI 233/528

- Countway Mediated Search

- Risk of Bias (RoB)

Systematic review Q & A

What is a systematic review.

A systematic review is guided filtering and synthesis of all available evidence addressing a specific, focused research question, generally about a specific intervention or exposure. The use of standardized, systematic methods and pre-selected eligibility criteria reduce the risk of bias in identifying, selecting and analyzing relevant studies. A well-designed systematic review includes clear objectives, pre-selected criteria for identifying eligible studies, an explicit methodology, a thorough and reproducible search of the literature, an assessment of the validity or risk of bias of each included study, and a systematic synthesis, analysis and presentation of the findings of the included studies. A systematic review may include a meta-analysis.

For details about carrying out systematic reviews, see the Guides and Standards section of this guide.

Is my research topic appropriate for systematic review methods?

A systematic review is best deployed to test a specific hypothesis about a healthcare or public health intervention or exposure. By focusing on a single intervention or a few specific interventions for a particular condition, the investigator can ensure a manageable results set. Moreover, examining a single or small set of related interventions, exposures, or outcomes, will simplify the assessment of studies and the synthesis of the findings.

Systematic reviews are poor tools for hypothesis generation: for instance, to determine what interventions have been used to increase the awareness and acceptability of a vaccine or to investigate the ways that predictive analytics have been used in health care management. In the first case, we don't know what interventions to search for and so have to screen all the articles about awareness and acceptability. In the second, there is no agreed on set of methods that make up predictive analytics, and health care management is far too broad. The search will necessarily be incomplete, vague and very large all at the same time. In most cases, reviews without clearly and exactly specified populations, interventions, exposures, and outcomes will produce results sets that quickly outstrip the resources of a small team and offer no consistent way to assess and synthesize findings from the studies that are identified.

If not a systematic review, then what?

You might consider performing a scoping review . This framework allows iterative searching over a reduced number of data sources and no requirement to assess individual studies for risk of bias. The framework includes built-in mechanisms to adjust the analysis as the work progresses and more is learned about the topic. A scoping review won't help you limit the number of records you'll need to screen (broad questions lead to large results sets) but may give you means of dealing with a large set of results.

This tool can help you decide what kind of review is right for your question.

Can my student complete a systematic review during her summer project?

Probably not. Systematic reviews are a lot of work. Including creating the protocol, building and running a quality search, collecting all the papers, evaluating the studies that meet the inclusion criteria and extracting and analyzing the summary data, a well done review can require dozens to hundreds of hours of work that can span several months. Moreover, a systematic review requires subject expertise, statistical support and a librarian to help design and run the search. Be aware that librarians sometimes have queues for their search time. It may take several weeks to complete and run a search. Moreover, all guidelines for carrying out systematic reviews recommend that at least two subject experts screen the studies identified in the search. The first round of screening can consume 1 hour per screener for every 100-200 records. A systematic review is a labor-intensive team effort.

How can I know if my topic has been been reviewed already?

Before starting out on a systematic review, check to see if someone has done it already. In PubMed you can use the systematic review subset to limit to a broad group of papers that is enriched for systematic reviews. You can invoke the subset by selecting if from the Article Types filters to the left of your PubMed results, or you can append AND systematic[sb] to your search. For example:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[sb]

The systematic review subset is very noisy, however. To quickly focus on systematic reviews (knowing that you may be missing some), simply search for the word systematic in the title:

"neoadjuvant chemotherapy" AND systematic[ti]

Any PRISMA-compliant systematic review will be captured by this method since including the words "systematic review" in the title is a requirement of the PRISMA checklist. Cochrane systematic reviews do not include 'systematic' in the title, however. It's worth checking the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews independently.

You can also search for protocols that will indicate that another group has set out on a similar project. Many investigators will register their protocols in PROSPERO , a registry of review protocols. Other published protocols as well as Cochrane Review protocols appear in the Cochrane Methodology Register, a part of the Cochrane Library .

- Next: Guides and Standards >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2024 2:45 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/meta-analysis

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to Review a Meta-analysis

Mark w russo , md, mph.

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

Address correspondence to: Mark W. Russo, MD, MPH Medical Director of Liver Transplantation Carolinas Medical Center, Transplant Center, 3rd floor Annex Building 1000 Blythe Boulevard, Charlotte, NC 28203; Tel: 704-355-6649; Fax: 704-355-7184; E-mail: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Meta-analysis is a systematic review of a focused topic in the literature that provides a quantitative estimate for the effect of a treatment intervention or exposure. The key to designing a high quality meta-analysis is to identify an area where the effect of the treatment or exposure is uncertain and where a relatively homogenous body of literature exists. The techniques used in meta-analysis provide a structured and standardized approach for analyzing prior findings in a specific topic in the literature. Meta-analysis findings may not only be quantitative but also may be qualitative and reveal the biases, strengths, and weaknesses of existing studies. The results of a meta-analysis can be used to form treatment recommendations or to provide guidance in the design of future clinical trials.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, statistic, bias

Meta-analysis provides a standardized approach for examining the existing literature on a specific, possibly controversial, issue to determine whether a conclusion can be reached regarding the effect of a treatment or exposure. Results from a meta-analysis can refute expert opinion or popular belief. For example, Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling lectured for many years on the benefits of vitamin C in the treatment and prevention of the common cold. However, several years ago, a meta-analysis of clinical trials examining this issue demonstrated that there is no clear benefit of high doses of vitamin C on the common cold. 1

The first applications of meta-analysis were made more than 30 years ago in the psychiatric literature. 2 Meta-analysis later made its appearance in the gastroenterology literature, with one of its first applications occurring in the assessment of the effectiveness of antisecretory drug dosing for duodenal ulcers. 3 Since then, metaanalysis has been applied to most conditions in gastroenterology and hepatology, including inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis, irritable bowel syndrome, and colon cancer. 4 – 8

If it is well conducted, the strength of a meta-analysis lies in its ability to combine the results from various small studies that may have been underpowered to detect a statistically significant difference in effect of an intervention. For instance, 8 studies of streptokinase suggested its effectiveness in treating patients presenting with myocardial infarction, yet only 3 of these studies reported statistically significant results. 9 Nevertheless, the results of a meta-analysis combining data across all 8 studies concluded that streptokinase was associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality. 9

As with the planning of any study, the study design of a meta-analysis determines the validity of its results. The Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) statement was published to provide guidelines for conducting meta-analyses, with the goal of improving the quality of published meta-analyses of randomized trials. 10 A checklist assessing the quality of a meta-analysis has also been developed by the QUOROM group and is available online ( http://www.consort-statement.org/QUOROM.pdf ).

This article focuses on the key areas that the reader should be aware of to determine whether a meta-analysis was properly designed. These areas include the development of the study question; methods of literature search; data abstraction; proper use of statistical methods; evaluation of results; evaluation for publication bias; sensitivity analysis; and applicability of results. A checklist for reviewing a meta-analysis is shown in Table 1 . By utilizing a standardized approach for critiquing a meta-analysis, the internal validity of the analysis can be determined.

Checklist for Meta-analysis

Development of the Study Question

The objectives of a meta-analysis and the question being addressed must be explicitly stated and may include primary and secondary objectives. The question at the focus of a meta-analysis should not have already been answered satisfactorily by the results of multiple well-conducted randomized trials. The more focused the question is, the more likely the study group will be homogenous. If the subjects across the studies are different, combining data from these studies is not appropriate. For example, a hypothetical meta-analysis on the effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication for reducing the risk of ulcer disease may not be useful or interesting because several studies have already demonstrated a benefit in the eradication of H. pylori when ulcer disease is present. Furthermore, the study population would likely include patients with both gastric and duodenal ulcers, making the population heterogeneous. On the other hand, a meta-analysis comparing the efficacy of different antibiotic treatment regimens to eradicate H. pylori in patients with duodenal ulcers may be more relevant and would constitute a more homogenous study population.

The primary objective of a meta-analysis may not be solely to determine the effectiveness of an intervention. Results from a meta-analysis may be used to determine the appropriate sample size of a future trial, develop data for economic studies such as cost-effectiveness analyses, or demonstrate the association between an exposure and disease. Frequently, the results of a meta-analysis are used to highlight the weaknesses of previous studies and to recommend how to improve the design of future trials.

Literature Search

One of the first steps when reviewing a meta-analysis is to determine whether the authors conducted a comprehensive search for clinical trials and other types of studies, some of which may be unpublished, related to the research question. The information sources that were searched should be provided. Literature searches can include computerized and manual searches, which involve reviewing the references of an article's “ancestor search,” as well as searching through abstracts, typically over the preceding 5 years. The most frequently used online resources for literature searches include PubMed, Cochrane Database, and Cancerlit. The Cochrane Collaboration was founded in 1993 and produces the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, which has generated more than 2,500 systematic reviews and meta-analyses ( http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/index.htm ). Reviews from the Cochrane database are typically of high quality and provide a helpful resource for those interested in performing or reviewing meta-analyses. 11 PubMed was developed by the US National Library of Medicine and includes over 17 million citations dating back to the 1950s. Cancerlit is produced by the US National Cancer Institute and is a database consisting of more than 1 million citations from over 4,000 sources dating back to 1963.

At least two reviewers should search sources for articles relevant to the meta-analysis, and the keywords used in the online searches should be provided in the article. Many authors include only full-length papers because abstracts do not always provide enough information to score the paper. The number of studies that were included and excluded should also be provided, as well as the reasons for exclusion.

Data Abstraction

Data abstraction is one of the most important steps in conducting a meta-analysis, and the methods of data abstraction that were used by the authors should be described in detail. In high-quality meta-analyses, a standardized data abstraction form is developed and utilized by the authors and may be provided in the paper as a figure. The reader of a meta-analysis should be provided with enough information to determine whether the studies that were included were appropriate for a combined analysis.

Two or more authors of a meta-analysis should abstract information from studies independently. It should be stated whether the reviewers were blinded to the authors and institution of the studies undergoing review. The results from the data abstraction are compared only after completing the review of the articles. The article should state any discrepancies between authors and how the discrepancies were resolved.

Results should be collected only from separate sets of patients, and the authors should be careful to avoid studies that published the same subjects or overlapping groups of subjects that appeared in different studies under duplicate publications. Raw numbers, in addition to risk ratios, should be recorded. Results from intention-to-treat analyses should be reported, when possible. The gold standard of data abstraction in a meta-analysis is to include patient level data from the studies combined in the meta-analysis, which usually requires contacting the authors of the original studies. 12 Obtaining patient level data may reveal differences among the trials that otherwise would not have been detected.

A quality score for each study included in a metaanalysis may be useful to ensure that better studies receive more weight. More than 20 instruments have been identified for the assessment for quality in both randomized clinical trials as well as meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. 13 Results can vary by the type of quality instrument, and a sensitivity analysis may need to be performed to determine the impact of the quality score on the results. 13 As with data abstraction, two reviewers should score the quality of the studies using the same quality instrument, and results from the quality assessment should be compared. Agreement among the reviewers should be reported, and differences in quality scores should be reconciled through discussion.

As with clinical trials, inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies included in the meta-analysis need to be well defined and established beforehand. 14 One goal of inclusion and exclusion criteria is to create a homogenous study population for the meta-analysis. 12 The rationale for choosing the criteria should be stated, as it may not be apparent to the reader. Inclusion criteria may be based on study design, sample size, and characteristics of the subject. Examples of exclusion criteria include studies not published in English or as full-length manuscripts. It has been reported that meta-analyses that restrict studies by language overestimate treatment effect only by 2%. 10 The number of studies excluded from the meta-analysis and the reasons for the exclusions should also be provided.

Statistical Techniques

When determining whether a meta-analysis was properly performed, the statistical techniques used to combine the data are not as important as the methods used to determine whether the results from the studies should have been combined. If the data across the studies should not have been combined in the first place because their populations or designs were heterogeneous, statistical methods will not be able to correct these mistakes.

Two commonly used statistical methods for combining data include the Mantel-Haenszel method, which is based on the fixed effects theory, and the DerSimonian-Laird method, which is based on the random effects theory. 15 One of the goals of these methods is to provide a summary statistic of an intervention's effect or exposure, as well as a confidence interval. The fixed effects model examines whether the treatment produced a benefit in the studies that were conducted. In contrast, the random effects model assumes that the studies included in the meta-analysis are a random sample of a hypothetical population of studies. The summary statistic is typically reported as a risk ratio, but it can be reported as a rate difference, person-time data, or percentage.

Arguments can be made for using either the fixed effects or random effects models, and sometimes results from both models are included. The random effects model provides a more conservative estimate of the combined data, with a wider confidence interval, and the summary statistic is less likely to be significant. The Mantel-Haenszel method can be applied to odds ratios, rate ratios, and risk ratios, whereas the DerSimonian-Laird method can be applied to ratios, as well as rate differences and incidence density (ie, person-time data).

The statistical test for homogeneity, which is also referred to as the test for heterogeneity, is frequently misused and misinterpreted as a test to validate whether the studies were similar and appropriate (ie, homogenous) to combine. The test may complement the results from data abstraction, supporting the interpretation that the studies were homogeneous and appropriate to combine. The test for homogeneity investigates the hypothesis that the size of the effect is equal in all included studies. P <.1 is considered to be a conservative estimate. If the test for homogeneity is significant, calculating a combined estimate may not be appropriate. If this is the case, the reviewer should re-examine the studies included in the analysis for substantial differences among study designs or characteristics of subjects.

Evaluating the Results

Data abstraction results should be clearly presented in order for the reader to determine whether the included studies should have been combined in the first place. The meta-analysis should provide a table outlining the features of the studies, such as the characteristics of subjects, study design, sample size, and intervention, including the dose and durations of any drugs. Substantial differences in the study design or patient populations signify heterogeneity and suggest that the data from the studies should not have been combined. 12 For example, a meta-analysis was conducted on the risk of malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease who were taking immunosuppressants. 16 The patients had either ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease and were taking azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, tacrolimus, or cyclosporine. Due to the differences in patient populations and types of treatment among the studies, the results from these studies should not have been combined.

The typical graphic displaying meta-analysis data is a Forest plot, in which the point estimate for the risk ratio is represented by a square or circle and the confidence interval for each study is represented by a horizontal line. The size of the circle or square corresponds to the weight of the study in the meta-analysis, with larger shapes given to studies with larger sample sizes or data of better quality or both. The 95% confidence interval is represented by a horizontal line except for the summary statistic, which can be shown by a diamond, the length of which represents the confidence interval.

Sensitivity analysis is an evaluation method employed when there is uncertainty in one or more variables included in the model or when determining whether the conclusions of the analysis are robust when a range of estimates is used. A sensitivity analysis is usually included in a meta-analysis because of uncertainty regarding the effectiveness or safety of an intervention. The values at the extremes of the 95% confidence intervals for risk estimates of key variables or areas with the most uncertainty can be included in additional modeling to determine the stability of the conclusions. For example, in a meta-analysis I conducted with colleagues on the efficacy and safety of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), the rates of new or worsening encephalopathy ranged from 17% to 60%. 17 This range was incorporated into a sensitivity analysis to report the best and worst case scenarios for encephalopathy post-TIPS.

Assessing for Publication Bias

Meta-analyses are subject to publication bias because studies with negative results are less likely to be published and, therefore, results from meta-analyses may overstate a treatment effect. One strategy to minimize publication bias is to contact well-known investigators in the field of interest to discover whether they have conducted a negative study that remains unpublished. With the development of the National Library of Medicine's clinical trial registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov), researchers conducting meta-analyses have better opportunities to identify trials that are unpublished. Publication bias may lead to the overestimation of a treatment effect by up to 12%. 10

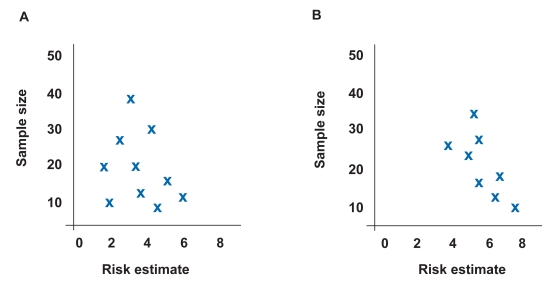

A funnel plot can visually reveal the presence of a publication bias. 18 A funnel plot is a graphic representation in which the size of the study on the y axis is plotted against the measure of effect on the x axis. Sampling error decreases as sample size increases and, therefore, larger studies should provide more precise estimates of the true treatment effect. In the absence of publication bias, smaller studies are scattered evenly around the base of the funnel ( Figure 1A ). In the presence of publication bias, small studies cluster around high-risk estimates with no or few small studies in the area of low-risk estimates ( Figure 1B ). For example, a study reviewing the literature on the association between Barrett esophagus and esophageal carcinoma nicely demonstrated the presence of publication bias using funnel diagrams. 19 Another method employed to address publication bias is a sensitivity analysis to determine the number of negative trials required to convert a statistically significant combined difference into a nonsignificant difference. Examples of these statistical methods to address publication bias include regression analysis, file-drawer analysis (failsafe N), and trim and fill analysis. 18

Example of funnel plot demonstrating no publication bias where the estimated true risk is 4. Risk estimates are evenly distributed around true risk (A). Example of funnel plot demonstrating publication bias where the estimated true risk is 4. Risk estimates cluster in lower right-hand corner, indicating that small studies with positive results are more likely to be published (B).

Applicability of Results

The results of a meta-analysis, even if they are statistically significant, must have utility in clinical practice or constitute a message for researchers in the planning of future studies. The results must have external validity or generalizability and must impact the care of an individual patient. In addition, the studies included in the metaanalysis should include patient populations that are typically seen in clinical practice. There should be a balance between finding studies that are similar and appropriate to combine without becoming too focused, in order to avoid a study population that is too narrow.

Meta-analysis Beyond Randomized, Clinical Trials

Although randomized clinical trials are usually the focus of a meta-analysis, the same methodology used for randomized trials can be applied to cohort studies. 20 The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group has proposed a checklist for conducting meta-analyses of prospective studies, 21 which is similar to the checklist for randomized trials proposed by QUOROM and the checklist shown in Table 1 .

There may be settings in which randomized data are not available, such as the association between a risk factor and cancer. For example, combined data from 21 prospective studies in a meta-analysis demonstrated a significant association between body mass index and pancreatic cancer. 22 The dangers of combining results from cohort studies is that bias is more likely to be introduced in cohort studies than in randomized trials and the study populations among cohort studies are more likely to be heterogeneous. Nevertheless, if there are multiple cohort studies in an area of interest and few or no randomized clinical trials, then the results from a metaanalysis may emphasize the need for one or more randomized trials and provide recommendations for optimal study design.

Meta-analysis can be a powerful tool to combine results from studies with similar design and patient populations that are too small or underpowered individually to demonstrate a statistically significant association. As with clinical trials, having an appropriate study question and design are essential when performing a meta-analysis to ensure that there is internal validity and that the results are clinically meaningful. Heterogeneity among studies in study designs or patient populations is one of the most common flaws in meta-analyses. Heterogeneity can be avoided by thoughtful data abstraction performed by two or more authors who use a standardized data abstraction form. By applying a systematic approach to metaanalysis, many of the pitfalls can be avoided.

- 1. Douglas RM, Hemila H, D'Souza R, et al. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Coochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD000980. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Smith ML, Glass GV. Meta-analysis of psychotherapy outcomes studies. Am Psychol. 1977;32:752–760. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.32.9.752. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Jones DB, Howden CW, Burget DW, et al. Acid suppression in duodenal ulcer: a meta-analysis to define optimal dosing with antisecretory drugs. Gut. 1987;28:1120–1127. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.9.1120. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, et al. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with nonstricturing small bowel Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:954–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00506.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Su C, Lichtenstein GR, Krok K, et al. A meta-analysis of the placebo rates of remission and response in clinical trials of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1257–1269. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.024. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Shi J, Wu C, Lin Y, et al. Long-term effects of mid-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary biliary cirrhosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1529–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00634.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Moskal A, Norat T, Ferrari P, Riboli E. Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of published cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:664–671. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22299. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, et al. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Stampfer MJ, Goldhaber SZ, Yusuf S, et al. Effect of intravenous streptokinase on acute myocardial infarction: pooled results from randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1180–1182. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211043071904. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Jadad AR, Cook DJ, Jones A, et al. Methodology and reports of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a comparison of Cochrane reviews with articles published in paper-based journals. JAMA. 1998;280:278–280. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.3.278. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Chalmers TC, Buyse M. Meta-analysis. In: Chalmers TC, Blum A, Buyse M, et al., editors. Data Analysis for Clinical Medicine: The Quantitative Approach to Patient Care. Rome, Italy: International University Press; 1988. pp. 75–84. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999;282:1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Greenhalgh T. Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) BMJ. 1997;315:672–675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.672. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Petitti DB. Meta-analysis, Decision Analysis, and Cost-effectiveness Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. Statistical Methods in Meta-analysis; pp. 90–114. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Masunaga Y, Ohno K, Ogawa R, et al. Meta-analysis of risk of malignancy with immunosuppressive drugs in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:21–28. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H219. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Russo MW, Sood A, Jacobson IM, Brown RS., Jr. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: an analysis of the literature on efficacy, morbidity, and mortality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2521–2527. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08664.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M, editors. Publication Bias in Meta-analysis: Prevention, Assessment, and Adjustments. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2005. Publication bias in meta-analysis; pp. 1–7. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119:333–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Russo MW, Goldsweig CD, Jacobson IM, Brown RS., Jr. Interferon monotherapy for dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C: an analysis of the literature on efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1610–1615. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07526.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton S, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Body mass index and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1993–1998. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22535. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (156.4 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Overview of meta‐analysis

Zhao‐qiong zhu.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

∗Corresponding author: Zhao‐Qiong Zhu, Department of Anesthesiology, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, Gui Zhou, 563000,China. E‐mail: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Revised 2021 Mar 11; Received 2021 Feb 28; Accepted 2021 Mar 18; Collection date 2021 Mar.

Meta‐analysis has been recognized as the best means to evaluate objectively and study the evidence for a particular issue. In order to give researchers a better understanding of the Meta process, we present an overall introduction to Meta‐analysis in terms of comprehensive assessment of the literature, goals, advantages, main steps, and article structure.

Keywords: Meta‐analysis, Literature retrieval, Information extraction, Heterogeneity

Introduction

With the development of evidence‐based medicine, Meta‐analysis has been recognized as the best means to evaluate objectively and study evidence for a specific problem, and is regarded as the highest level of evidence, which has become a good basis for evidence‐based decision‐making. Meta‐analysis is a kind of statistical method that synthesizes many research results of the same problem with specific conditions, which is the basis of clinical research (Zeng XT, et al., 2013 ). Compared with reviews and systematic reviews, the literature screening of Meta‐analysis is more rigorous, the data extraction of Meta‐analysis is more standardized and its refinement of results through statistical analysis makes the results more scientific and objective. Moreover, the purpose of Meta‐analysis is to increase the efficiency of statistical test, quantitatively estimate the average level of research effects, evaluate the inconsistency of research results, and find new hypotheses and research ideas.

The understanding of Meta‐analysis is mainly from the following aspects: (1) Meta‐analysis is a massive integration of literatures and plays a role of comprehensive evaluation. (2) The goal of Meta‐analysis is to evaluate the results of multiple research results of the same kind. (3) The method of Meta‐analysis is to collect literatures, extract specific problems from the literatures, then perform statistical analysis, and finally obtain the results. (4) The advantage of Meta‐analysis is to conduct an integrated analysis of published or unpublished research results and obtain convincing evidence. Compared with traditional reviews, Meta‐analysis is more comprehensive and accurate because it introduces statistical methods.

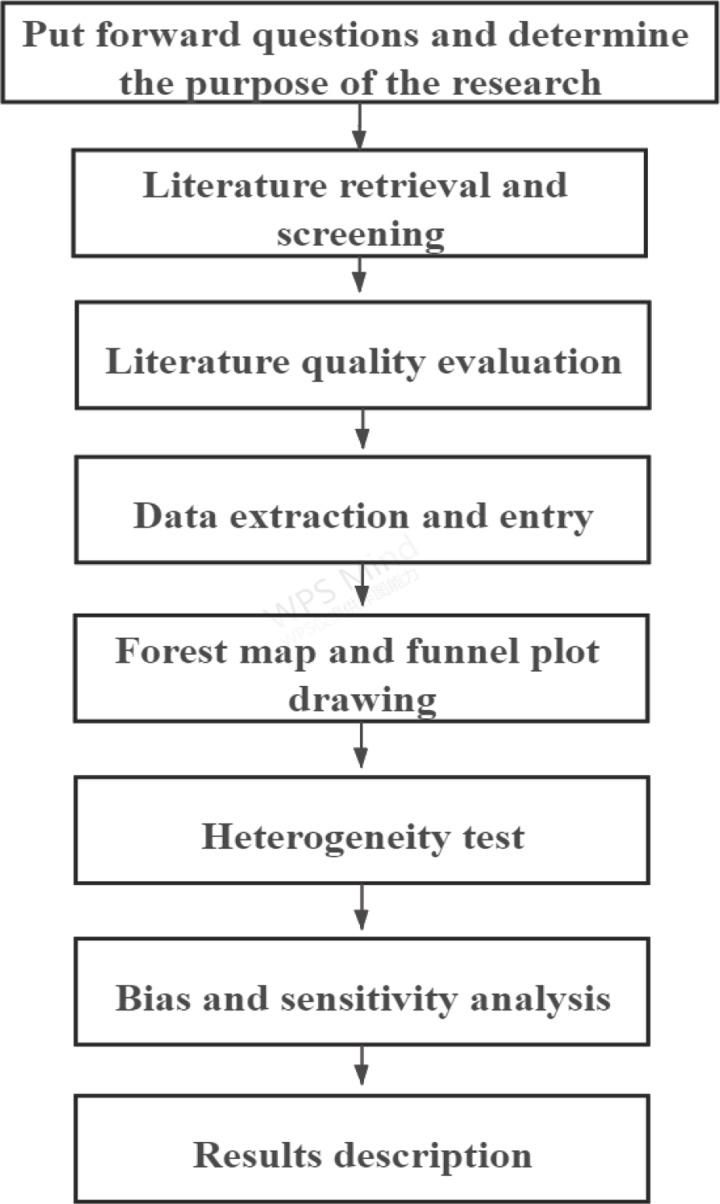

Mainsteps and key points

The steps of Meta‐analysis mainly include raising questions and determing the purpose of the research, literature retrieval and screening, literature quality evaluation, data extraction and entry, forest map and funnel plot drawing, heterogeneity test, bias and sensitivity analysis and results description ( Figure 1 ). The overview is as follows.

The main steps of Meta‐analysis

Topic selection

First of all, the topic selection of Meta‐analysis should be based on clinical significance. The principle of the topic selection mainly includes: the importance, controversial and innovative of the problem, as well as the need for appropriate original research and clear effect indicators (Zeng XT, et al., 2013 ). Topics can be selected from the relevant research, evaluation of intervention measures, evaluation of diagnostic methods, prognosis estimation, cost and benefit analysis, selection of suitable subjects, determination of reasonable indicators and making inclusion criteria.

Literature retrieval and screening

In the following literature retrieval, it is necessary to identify the search terms as comprehensively as possible in different databases (Zhan SY, et al., 2010 ). After retrieving the required documents, read and screen the retrieved documents with the steps of reading abstracts, full texts, and references.

Literature quality evaluation

Quality evaluation of literature is an important part of literature screening. In the quality evaluation, we should pay attention to whether the research design is clear;whether the method is random; whether the statistics are blind; whether the research background is similar; whether the effect evaluation is accurate; whether the research is adaptive and the results are fully described (Castaño‐RN, et al. 2017 ; Abt D, et al. 2017 ). Now commonly used quality assessment tools include Cochrane bias risk assessment tools, AMSTAR scale, OQAQ list, CASP list, SQAC scale, Chalmers scale (Munder T, et al., 2018 ). In the literature management, we can use Endnote and other softwares to record and manage the literature obtained by various ways, and easily generate a list of references to improve the efficiency of literature screening.

Data extraction and entry

Information extraction refers to the correct collection and recording of the included research results and all valuable information according to the inclusion criteria. It is a key step in Meta‐analysis, directly affects the accuracy of the results and connects the original research report and Meta‐analysis. The main function of information extraction is to use original data as the source of data analysis and to facilitate the verification of research data. In information extraction, we must first draw the information extraction table. The main contents should include: (1) Author, year, source; (2) Research design: method, grouping, blind method; (3) Object characteristics: sample size, region; (4) Intervention characteristics: method, blind method, dose; (5) Evaluation index: instrument, index, time; (6) Results (quality) rate: ratio, relative risk; It is worth noting that in the process of information extraction, two people are required to extract and cross‐check independently, while we need to constantly revise and improve the extraction form (Wang M, et al., 2017 ).

Meta‐software analysis‐forest map and funncl plot drawing

Meta‐analysis software provides an important guarantee for the implementation of various types of Meta‐analysis. Currently, there are many kinds of softwares, and the operating system and its functions are also different. At present, the commonly used softwares include Stata, R language (Foo YZ, et al., 2017 ), SAS, SPSS, etc. Among them, the statistical analysis of data mainly starts from the following aspects: (1) Calculate the effect value, variance and weight of each research; (2) Homogeneity test is needed for the effect values of each research result; (3) Calculate the combined effect value; The effect value and confidence interval of each research is classified; (4) Draw forest map.

In 2010, international evidence‐based medicine experts Sharon Straus and David Moher jointly issued a call that all systematic reviews/Meta‐analysis should be registered in order to reduce publication bias and promote transparency and cooperation in the production process. Registration can not only improve the quality of Meta‐analysis, but also avoid the waste of valuable manpower and material resources caused by repeated work (McClure GR, et al., 2016 ). At present, Meta‐analysis can be registered in Cochrane groups or PROSPERO. Compared with the two, Cochrane registration is more rigorous and cumbersome, and currently only randomized trials, diagnostic accuracy studies and methodological meta‐analysis are accepted. PROSPERO registration is relatively simple, and the audit is not very strict. At present, the Meta‐analysis registration of treatment, prevention, diagnosis, monitoring, risk factors and genetic association are accepted.

Heterogeneity analysis

Meta‐analysis is based on the original research, so its quality must be affected by the quality of the original research. According to the types of original research, the corresponding quality evaluation tools are also different. Similarly, the quality of the original research is divided into report quality and methodological quality. The report quality can be evaluated by the report specification, and the methodological quality needs special tools. Inevitably, all studies included in the same Meta‐analysis are different. We call the variations among different studies in Meta‐analysis heterogeneity (Qiu Y, et al. 2017 ; Abd EAMS, et al. 2017 ).

The heterogeneity of Meta‐analysis is divided into clinical heterogeneity, methodological heterogeneity and statistical heterogeneity. Clinical heterogeneity refers to the variation caused by different participants, different interventions and different endpoints of the study. Methodological heterogeneity refers to the variation caused by the differences in experimental design and quality, such as the hidden differences in the application and distribution of blind methods, or the inconsistency in the definition and measurement of outcome during the experiment. Statistical heterogeneity is the variation of estimated therapeutic effects between different trials, which is the direct result of clinical and methodological diversity between studies. In order to reduce the heterogeneity among studies, we should formulate strict and unified inclusion and exclusion criteria when conducting Meta‐analysis. Only studies with the same research purpose and high quality can be included in the analysis, and the consistency of research objects and treatment factors can be considered, which can ensure the clinical homogeneity of included studies to a certain extent, which is also a prerequisite for merging different studies. So as to ensure the homogeneity of methodology, it is necessary to conduct strict quality evaluation of the combined research, including random methods, blind implementation, random scheme concealment, intentional treatment analysis and baseline similarity. Only on the basis of certain homogeneity in clinical and methodological aspects, can we enter the statistical heterogeneity test between studies and the next merger.

As for the presentation and description of the results, we usually accurately display and highlight the results in the form of articles, fully discuss the interaction between the analysis results and clinical information, and finally draw appropriate conclusions to guide the future clinical operation and theoretical update.

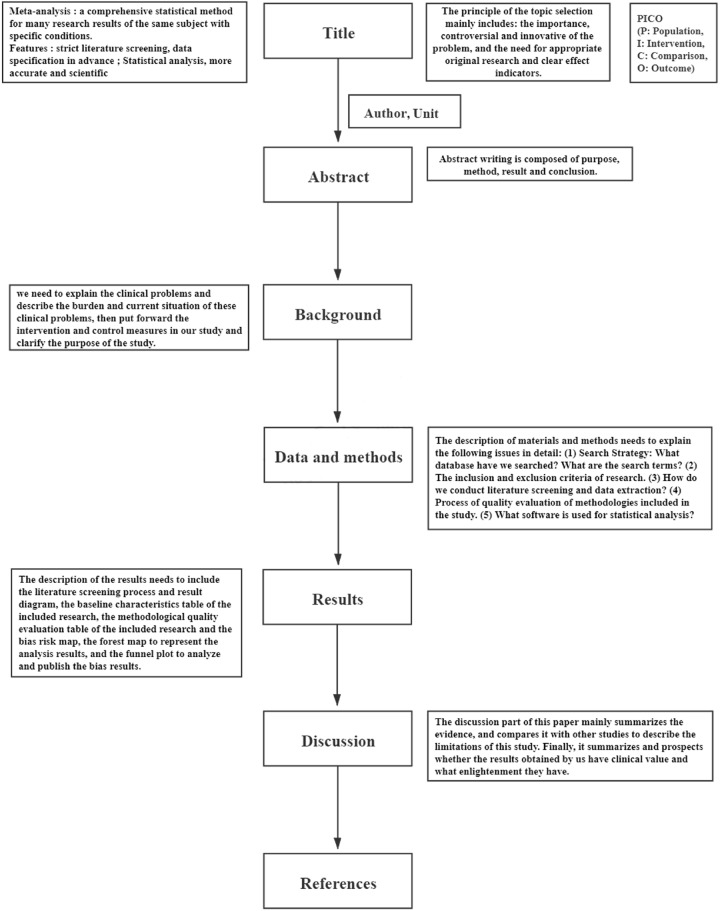

Framework for writing meta‐analysis articles

A clear and smooth structure is especially important for the full and perfect presentation of meta results. At the end of the article, we introduce the structure of the Meta‐analysis, the content of the article mainly includes the title, abstract, background, data and methods, results, discussions or conclusions and references ( Figure 2 ). The title of the article needs to contain the points in PICO (P: Population, I: Intervention, C: Comparison, O: Outcome) (Moher D, et al., 2009 ). Abstract writing is composed of purpose, methods, results and conclusions. In writing the background of the article, we need to explain the clinical problems and describe the burden and current situation of these clinical problems, then put forward the intervention and control measures in our study and clarify the purpose of the study. The description of materials and methods needs to explain the following issues in detail: (1) Search Strategies: What databases have we searched? What are the search terms? (2) The inclusion and exclusion criteria of research. (3) How do we conduct literature screening and data extraction? (4) Process of quality evaluation of methodologies included in the study. (5) What softwares are used for statistical analysis? The description of the results needs to include the literature screening process and results diagram, the baseline characteristics table of the included research, the methodological quality evaluation table of the included research and the bias risk map, the forest map to represent the analysis results, and the funnel plot to analyze and publish the bias results. The discussion part of this paper mainly summarizes the evidence, and compares it with other studies to describe the limitations of this study. Finally, it summarizes and prospects whether the results obtained by us have clinical value and what enlightenment they have.

Article structure of Meta‐analysis

In summary, Meta‐analysis is a development process that is constantly updated and improved with the demand, and there is still room for research and development and improvement with the deepening of practice. Meta‐analysis should be conducted according to the recommended reporting norms, and constantly follow up the progress of Meta‐analysis, timely learning, thinking and research.

Ethical statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Transparency statement

All the authors affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Authors' contribution

Xu Fang and Zhao‐Qiong Zhu contributed the central idea, analysed most of the data, made figures & tables and wrote the initial draft of the paper. Nan Zhao contributed to refining the ideas, carrying out additional analyses and finalizing this paper.

Acknowledgments

- Abd EAMS, Kahle M, Meier JJ, et al. A meta‐analysis comparing clinical effects of short or long‐acting GLP‐1 receptor agonists versus insulin treatment from head‐to‐head studies in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Obes Metab, 2017, 19: 216–227. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abt D, Schmid HP, Re: Clinicopathological Features and Prognostic Value of Incidental Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in Radical Cystoprostatectomy Specimens: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis of 13 140 Patients. Eur Urol, 2017, 72: 154–155. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Castaño‐ RN, Kaakoush NO, Lee WS, et al. Dual role of Helicobacter and Campylobacter species in IBD: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Gut, 2017, 66: 235–249. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Foo YZ, Nakagawa S, Rhodes G, et al. The effects of sex hormones on immune function: a meta‐analysis. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 2017, 92: 551–571. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McClure GR, Belley‐Cote EP, Singal RK, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: a protocol for a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open, 2016, 6: e013273. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med, 2009, 3 (3): e123–130. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Munder T, Barth J. Cochrane's risk of bias tool in the context of psychotherapy outcome research. Psychother Res, 2018, 28: 347–355. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu Y, Mao R, Chen BL, et al. Effects of Combination Therapy With Immunomodulators on Trough Levels and Antibodies Against Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 15: 1359–1372.e6. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang M, He X, Chang Y, et al. A sensitivity and specificity comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and core needle biopsy in evaluation of suspicious breast lesions: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Breast, 2017, 31: 157–166. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeng XT, Shen K, Luo J. Meta‐analysis Series 12: Evaluation of Distribution Hiding. Chinese Journal of Evidence‐based Cardiovascular Medicine, 2013, 5 (3): 219–221. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeng XT, Tian GX, Zhang C, et al. Meta‐analysis Series Fifteen: Progress and Consideration of Meta‐analysis. Chinese Journal of Evidence‐based Cardiovascular Medicine, 2013, (6): 561–563, 587. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhan SY. How to make a good systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Peking University (Medical Edition), 2010, 42 (6): 644–647. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (596.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Meta-analysis is a central method for knowledge accumulation in many scientific fields (Aguinis et al. 2011c; Kepes et al. 2013). Similar to a narrative review, it serves as a synopsis of a research question or field.

Meta-analysis is a research method for systematically combining and synthesizing findings from multiple quantitative studies in a research domain. Despite its importance, most literature evaluating meta-analyses are based on data analysis and statistical discussions.

Overview: When a review strives to comprehensively identify and track down all the literature on a given topic (also called “systematic literature review”). Meta-analysis: A specific statistical strategy for assembling the results of several studies into a single estimate.

A systematic review is best deployed to test a specific hypothesis about a healthcare or public health intervention or exposure. By focusing on a single intervention or a few specific interventions for a particular condition, the investigator can ensure a manageable results set.

In brief: What are systematic reviews and meta-analyses? Last Update: September 8, 2016; Next update: 2024. Individual studies are often not big and powerful enough to provide reliable answers on their own. Or several studies on the effects of a treatment might come to different conclusions.

Meta-analysis is a systematic review of a focused topic in the literature that provides a quantitative estimate for the effect of a treatment intervention or exposure. The key to designing a high quality meta-analysis is to identify an area where ...

1. Understand the basic structure and parts of a systematic review. 2. Be able to read and critically appraise a published systematic review. Biostatistics, Systematic review, Meta-analysis. Go to: Fig. 1. The annual number of published systematic reviews has increased rapidly over the past 30 years.

This editorial briefly summarizes the insights of these papers; provides a workflow of the essential steps in conducting a meta-analysis; suggests state-of-the art methodological procedures; and points to other articles for in-depth investigation.

Therefore, it is important that healthcare practitioners become competent in understanding and applying systematic review findings. This simple guide outlines the key principles regarding the design, conduct and interpretation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Compared with reviews and systematic reviews, the literature screening of Meta‐analysis is more rigorous, the data extraction of Meta‐analysis is more standardized and its refinement of results through statistical analysis makes the results more scientific and objective.