Try searching for

- Misinformation

- Subscriptions

- Fact-checking

AI and journalism: What's next?

Illustration generated by the Midjourney 5.2 text-to-image model, using the prompt “An abstract image representing the uncertain future of digital journalism in the age of artificial intelligence.”

Innovation in journalism is back. Following a peak of activity in the mid 2010s, the idea of fundamentally reinventing how news might be produced and consumed had gradually become less fashionable, giving way to incrementalism, shallow rhetoric and in some cases even unapologetic ‘innovation exhaustion.’ No longer. The public release of ChatGPT in late November of 2022 demonstrated capabilities with such obvious and profound potential impact for journalism that AI-driven innovation is now the urgent focus of the senior leadership teams in almost every newsroom. The entire news industry is asking itself ‘what’s next’?

For many people in journalism the first half of 2023 was a time for asking questions and learning the basics of AI. What can ChatGPT actually do? What is generative AI? What is a language model? What is a ‘prompt’? How dependable are these tools? What kind of skills are required to use them? How fast is this technology improving? What are the risks? How much of all this is just hype?

Many newsrooms went further, providing their employees and audiences with statements or guidelines describing how they intended to approach the use of generative AI in their workflows and news products. Some even began publishing a few experimental articles written by ChatGPT. Very few, however, have yet taken specific steps to pragmatically and routinely apply these technologies in their newsrooms. Change is in the air, but specific initiatives are harder to find.

Over the past six months I have had the privilege of spending significant time discussing AI with the senior leadership of more than 40 news organisations, ranging from scrappy digitally-native newsrooms in Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America to many of the largest global news providers based in the US, UK, and Europe.

This access came as a result of my familiarity with AI-driven innovation in news, acquired from a combination of applied product innovation at large media companies in the US and UK, and from a small parallel academic career exploring the first principles of computation applied to news production and consumption.

My journey with many of the questions now facing news organisations began in Silicon Valley more than a decade ago, and my exploration of the GPT family of language models began in 2019 at the BBC. My career focus — a relative niche until the arrival of ChatGPT — was suddenly of great interest to many people in the news industry.

This article is based on a distillation of what I have learned from these conversations. It assumes a knowledge of generative AI’s general capabilities and potential, and examines some of the ways that large news organisations are thinking about its strategic and practical implications for their newsrooms. My intent here is to help advance the conversation beyond awareness and towards specific initiatives that can help move newsrooms forward in preparing for an uncertain AI-mediated future.

Any point of view regarding the application of AI to news is somewhat speculative, especially given the remarkable pace of advancement in AI functionality. Nonetheless, I believe that some clarity may be emerging.

Coming up with a list of things that your newsroom might be able to do using ChatGPT is fairly easy (Summarisation! Rewriting in a simpler style!). It is much harder to clearly identify exactly what it is that you are trying to achieve with generative AI, why you are trying to achieve it, how you might plausibly achieve it at scale in routine and professionally managed operations, and whether that achievement will even continue to be relevant as AI fundamentally alters the competitive landscape in the coming months and years.

To frame this discussion I will begin with an overview of potential strategies for using AI in news, before turning to options for the practical deployment of AI in newsrooms, and the infrastructural and organisational requirements needed to support those options. At the end of the piece I will offer a point of view for changes that we might anticipate for the news industry in the longer term.

1. Applying generative AI to news: product and editorial strategies

Efficiency-focused strategies

The most obvious opportunities for applying generative AI to news are in bringing new efficiencies to specific and familiar steps within the existing news production workflows supporting an organisation’s existing news products. This ‘more-efficient-production-of-existing-products’ strategy is attractive in its simplicity, but its benefits will almost certainly be short-lived because it assumes that the existing media environment will continue in roughly its existing form.

It is increasingly possible that the competitive environment, product offerings, production workflows and business models of news organisations will change, possibly radically, as use of generative AI becomes ubiquitous and as AI-based media products appear.

There are early indications of this in the nascent generative search experiences offered by Google and Microsoft, in the user control of consumption experiences offered by well-funded news aggregators such as Artifact (launched by the founders of Instagram), in the declared intention to build a foundation language model around ‘X’ (or Twitter 2.0), and even in the early behaviour of tens of millions of early adopters of generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney, who have quickly learned how to use traditional media essentially as raw material for their own self-directed consumption experiences.

A ‘more-efficient-production-of-existing-products’ strategy is clearly a reasonable place to start, but it does not fundamentally compete with new AI-enabled experiences and therefore may not remain sufficient for long.

Product expansion strategies

A more ambitious AI strategy for news organisations lies in reimagining and expanding the scope and scale of an organisation’s news products in ways that only become feasible using generative AI. This ‘new-products-for-new-audiences’ strategy will likely be more enduring than an efficiency-only approach because it seeks to actively accommodate the expansion of audience choice that generative AI enables.

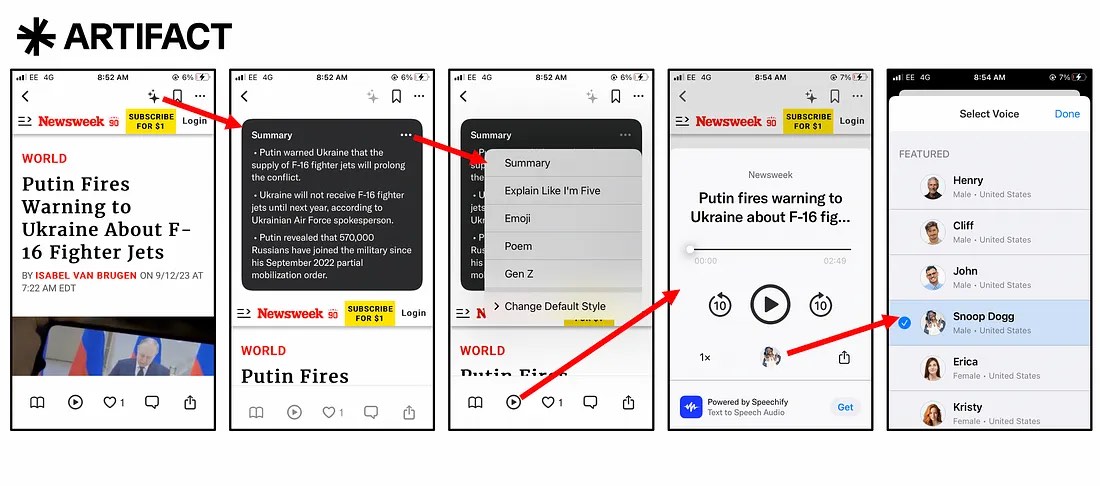

In essence this approach assumes that if generative AI is going to provide audiences with more control over their news consumption experiences (as pioneered by the Artifact app), then news organisations might as well offer that option directly. If news consumers can now control how they consume articles, then shouldn’t they be able to do that on a news publisher’s app or website?

The advantage of this strategy is that it offers a way to compete within an emerging AI-mediated news ecosystem while continuing to exploit the advantages that news organisations already possess — brand, trust in editorial processes, habit, etcetera.

Furthermore, that competition need not merely be aimed at existing targeted audiences but might now also be extended to entirely new audiences via new journalistic products that would have been editorially impossible without generative AI. Even small newsrooms now have the option of offering comprehensive multi-media news products to diverse audiences with radically different consumption behaviours and preferences.

Differentiation strategies

A more enduring strategy for news in the age of AI will necessarily be centred on differentiation and competitive advantage, offering exclusive news products that remain uniquely valuable to audiences even as the information ecosystem changes.

This ‘unique products’ strategy is challenging because it will be audiences that decide on the relative uniqueness of a newsroom’s products, not newsrooms. Pursuit of differentiation must therefore be clear-eyed, unsentimental and data-tested – magical thinking about vague specialness requiring little effort to implement is unlikely to be helpful here. A differentiation strategy might still potentially fit well with some of the values and brand attributes of traditional journalism, especially if the information ecosystem begins to significantly degrade under the onslaught of AI-generated content.

Some examples of familiar forms might include: proprietary news gathering using special access or special skills; audience trust gained from well-demonstrated verification and validation processes; richly contextual content produced from archives or from deep familiarity with subject matter; or perhaps a commitment to systematic coverage of particular subject domains using narrowly customised stories, such as local coverage or climate reporting.

All these opportunities, however, will likely need to be comprehensively optimised using generative AI to remain competitive within an AI-mediated information ecosystem, even if their core value is differentiated. Developing forms of differentiation will likely be very challenging for many news organisations, especially for those whose current product is largely built on packaging commodity information, however there may eventually be no alternative.

Techno-editorial strategies

A similar but even more ambitious potential strategy, probably available only to a few well-resourced news organisations or well-funded start-ups, is to seek to develop proprietary or competitively defensible information technologies and services centred on news – products that might resemble specialised intelligence tools more than traditional news products.

This option, which we might call a ‘techno-editorial product’ strategy, would likely reverse the relationship between the product and editorial functions that currently exists in most news organisations, requiring editorial operations to support product and business development rather than the other way around.

This kind of strategy might include provision of highly technical solutions such the systematic extraction of news events (and, critically, of news stories) from enormous streams of natural language text and speech, the creation and maintenance of proprietary datasets in story form, the systematic certification of that news, new tools for exploring and contextualising complex news, the extreme customization of news and of the experience of consuming news, etc.

Such processes and tools might resemble those used by government intelligence organisations, platforms like search engines, or processes and tools already offered by news organisations targeting financial professionals, but with much broader coverage and audience appeal.

Such a strategy would likely be research-led, would require substantial capital investment and needs to be justified by expected returns from high-value subscriptions. Such ‘techno-editorial’ businesses may not be well suited for reach-based news products but might nevertheless become significant components of an information ecosystem in which generative AI is ubiquitously deployed.

Training your own model

As news organisations look for strategic responses to generative AI, there are also a few options that are often discussed but which might be less attractive than they first seem. One of those ‘approach-with-caution’ strategies is that of pre-training a proprietary language model using a newsroom’s archive.

This is likely a bad idea for most news organisations for multiple reasons, including the difficulty in attracting the world-class machine learning talent needed to create a useful language model, the tiny size of the archives of even the largest news organisations relative to the training needs of a useful language model, and the substantial costs of periodic retraining, maintaining and operating a proprietary language model in the face of rapidly improving technology.

Furthermore there are few clear benefits available from training a proprietary model, even if it were competitive in performance to a commercial or open-source language model. Concerns about data security, vendor lock-in or a need for niche functionality can probably be addressed in much easier ways, including contractually, via abstraction of user interfaces, using model fine-tuning or using an open-source model.

A proprietary model built on the same transformer architecture as most current LLMs will still hallucinate, even if the entire training corpus is accurate, and a news organisation is unlikely to match the efforts underway by technology companies aimed at making language models more accurate. Training a proprietary language model may make sense for some very specific use cases in some news organisations with special information products (for example a ‘ text-plus-financial-data’ multi-modal model at Bloomberg), but even in such cases a clear-eyed, careful consideration of the costs and benefits of such a strategy is essential.

Building a chatbot for archives

Another ‘approach-with-caution’ strategy that some news organisations have pursued or considered is that of building a proprietary chatbot that enables conversational, interactive access to the organisation’s current news and archive.

This option seems attractive given the success of ChatGPT. However, when considering a news chatbot, it is important to separately consider the interface component (i.e. interactive chat), the information component (e.g. news and its context) and the underlying technology used to deliver the experience (e.g. LLMs).

Despite the rapid adoption of ChatGPT, text or verbal chat as an interface is still very far from broadly accepted as a way of accessing any kind of information, much less news. Audience analytics for news bulletins built for voice agents like Amazon Alexa and Google Home have been disappointing, and early attempts at LLM-enabled chatbots by media companies have delivered little traffic.

This lack of success might be at least partly due to the relative inadequacy of news and news archives as a dataset powering such an interface, which for news organisations will be considerably smaller and more homogenous than the vast datasets that power ChatGPT or even search for that matter.

Furthermore, from a technology perspective it is very difficult to replicate the fluid nature of communication with an LLM using the techniques currently available for constructing chatbots from archives, which typically involve some kind of embedding-based search operation combined with interpretation of the results by the language model.

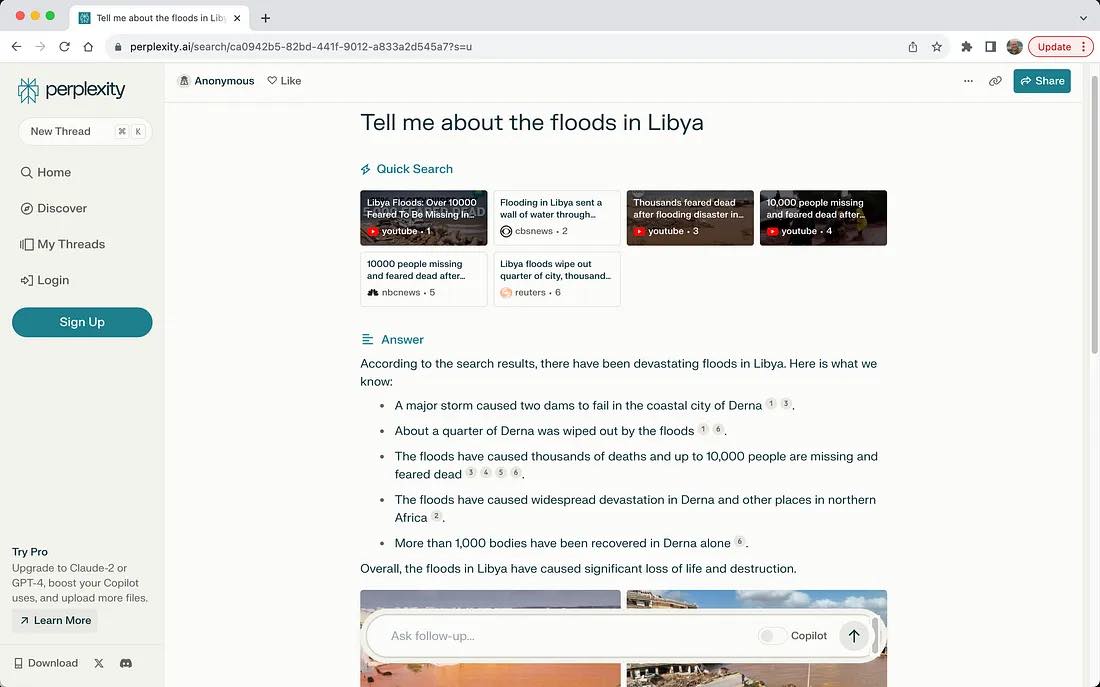

The result is often either far too many ‘I don’t know’ responses to specific queries, or references to ‘closest match’ archived articles in isolation from current context, an experience that can’t compete with internet-enabled chatbots like Bing Chat or Perplexity.ai.

Communication strategy

Regardless of where a news organisation might be in its path towards a strategy for responding to AI, there is an urgent strategic need that requires early attention – that of communicating the organisation’s approach to AI to stakeholders, funders, staff and audiences.

The urgency of strategic communication about AI for news organisations comes from the awareness that every individual connected with the organisation already has about the abilities of these tools and their potential for dramatic disruption. Most people in the news industry are already playing with the tools, reading the reports, assessing the potential and asking the obvious questions.

It would, of course, be ideal to patiently assess the situation, carefully devise a strategy, produce a plan for executing that strategy, and then communicate that strategy and plan – but that may not be possible to do quickly.

A more practical communication strategy at this stage might consist of acknowledging the situation, articulating how the organisation is engaging with and learning about AI, providing clear guidelines for its early or limited use, demonstrating new approaches to innovation, signalling adaptability and generally preparing for change. A tone of optimism and excitement for the potential of AI to help raise journalism above commodity information and to make it more accessible to many more people is also appropriate.

A strategic path to continued relevance

The common objective for almost all news organisations in navigating the coming AI-induced transformation is, bluntly, continued relevance.

News organisations, whether funded by ads, subscriptions, public funds or philanthropy, will seek to remain sufficiently valuable to enough people to ensure that those funding mechanisms continue to function.

The challenge of the coming transition to an AI-mediated information ecosystem is therefore to navigate a path that takes advantage of near-term opportunities for efficiency, medium-term opportunities for new products and services for audiences, and longer-term opportunities for re-imagining what news can become in a transformed information ecosystem.

This path obviously comes with considerable associated risk, specifically the risk of losing existing value and of not being able to develop new value to replace it, and may therefore require a greater tolerance of risk by leaders in news organisations. Developing that greater tolerance for risk, a tolerance perhaps closer to that of the technology companies that initiated this transition, might be the most important strategic step that a news organisation can take.

2. How to deploy generative AI in newsrooms

From strategy to projects

Any strategy for adapting a newsroom to an information ecosystem defined by generative AI is of little use without specific, practical projects that translate that strategy into useful outcomes.

Identifying such projects is obviously difficult during this current period of exceptionally rapid change, because of the considerable risks of wasted investments, embarrassing missteps or potential damage to brands or trust. In addition, projects can only contribute meaningfully towards a strategy if they can be applied in routine, day-to-day operations, rather than merely as testable prototypes or demonstrators.

To move forward, therefore, we need to identify categories of projects that might advance newsrooms towards an AI-ready future while minimising risks, and also identify the infrastructure requirements needed to deploy those projects routinely at scale when that time comes.

Back-end projects

A relatively low risk category of generative AI projects is purely back-end applications. These are applications with no direct audience-facing output, not even draft text, but which instead deliver their value to journalists or to businesses. These can include efficiency-focused or quality-focused tasks such as tagging, other kinds of categorisation, headline and SEO suggestions, assembly of newsletters from pre-existing copy, copy-editing, brainstorming and ideation, early research, some analysis, etcetera.

In addition to being relatively low risk, back-end AI applications are also relatively easy to implement as they are often ‘loosely coupled’ to news production workflow and infrastructure. Such applications can sometimes be managed by stand-alone tools disconnected from the primary publishing stack of the organisation, operated by specialised staff separate from the main editorial workflow.

Language task projects

A more ambitious but still relatively low risk category of generative AI projects include those applications that produce draft text by modifying source text in some way. These applications use language models solely for ‘language tasks’ and should not introduce any information content into the draft that was not already present in the source document.

They explicitly do not depend on the knowledge available to the model as a result of its training data, and they therefore reduce (but don’t eliminate) the risks of hallucinations, biases and other issues.

Examples of language tasks include summarisation , simplification, stylistic re-versioning, rewriting text for particular channels (social media, topic bulletins, etcetera), script-writing for audio or video, translation...

Language tasks can be done using any form of model access, such as the ChatGPT user interface, custom-built API-driven tools or even as new features integrated into content authoring and management systems. Language tasks can also be part of any strategy, including strategies based on efficiency, on new products or on differentiation. They are a fundamental category of journalistic task in an AI-enabled newsroom.

Knowledge task projects

A higher risk category of generative AI projects are applications that produce draft text with information content that originates in the language model itself, rather than from a source document.

These applications perform so-called ‘knowledge tasks’, because they are doing more than merely modifying language – they are true ‘authoring’ applications of language models.

The increased risk associated with knowledge task projects comes from the significant potential for hallucinations, simple error from training data, biases, out-of-date context and other limitations inherent in language models.

Nonetheless, if these risks can be managed , knowledge tasks offer a substantial range of news products including provision of context for stories, explainer-like background content , different interpretations of events based on historical context, and even full articles, especially on evergreen, commodity subject matter.

Mitigating the risks associated with knowledge tasks requires editing processes designed to detect error and inappropriate content – non-trivial tasks, as evidenced by the difficulties experienced by CNET in publishing knowledge-based content from language models. Nonetheless, there are clearly many significant journalistic opportunities available from knowledge tasks, and these opportunities will likely increase as we collectively learn more about how to manage and edit their output and as we begin to use AI to help do that.

As with language tasks, knowledge tasks can be integrated into workflows in different ways and can contribute to different strategies. They too are a fundamental category of journalistic task in an AI-enabled newsroom.

Medium-to-medium transformation projects

A particularly ambitious category of generative AI projects for news are applications that transform information content from one information medium into another, for example from text into audio, from text into video or from text into graphical images.

Unlike language tasks and knowledge tasks, these applications typically depend on special-purpose medium-to-medium transformation models, often used in combination with general-purpose large language models within complex workflows.

Such special-purpose models include speech-to-text models (transcription), text-to-speech models (synthetic voices), text-to-video models (synthetic avatars, automated generation of B-roll video, etcetera), text-to-image models and others. These tools are still at an early stage. But they are developing very quickly, are widely available, and already easily match human quality in many cases.

Furthermore, the potential of this category of applications is likely to increase with the imminent arrival of so-called ‘multi-modal’ functionality enabling richly descriptive image-to-text, video-to-text and other transformations.

Examples of potentially high-value journalistic tasks that can be accomplished using these cross-media models include the automated or semi-automated creation of text articles from audio or video source material, the creation of audio and video news products from text articles , the transformation of text articles into graphical stories or videos, and the automated or semi-automated creation of podcasts from articles.

These tasks are most useful for a product expansion strategy. They can often be achieved using just model vendor user interfaces and so have the potential to enable relatively low-resource newsrooms to quickly offer multimedia content at significant scale.

Some potential barriers to implementing this category of projects include the need for an editorial producer with experience in the output medium to ensure quality, the not insignificant cost of using the specialised models, and the challenge of distributing the same story in several different media.

Listening and monitoring projects

The project categories described above all focus on novel ways of producing news products using AI, but practical projects focused on news-gathering are also viable using large language models.

The term ‘generative AI’ has an obvious built-in bias towards the generation of media, but large language models and multi-modal models can also read, listen and soon observe at enormous scale, enabling entirely new ways of reporting news.

The kinds of news-gathering tasks that these models can perform extend far beyond the earlier generation of ‘social listening’ tools, which usually just searched for keywords in the feeds of social media platforms. The ‘natural language understanding’ (NLU) abilities of LLMs can not only read, but interpret, evaluate, analyse, synthesise and summarise.

Furthermore, they can do this not just with natural language text and speech, but also with structured data — as clearly demonstrated by OpenAI’s new ‘ code interpreter ’ add-on to their GPT-4 LLM, and likely soon with visual information in images and video. Projects based on NLU and ‘reporting at scale’ are already underway at newsrooms, including small newsrooms. Such projects may be most appropriate for a differentiation strategy and might enable newsrooms to build out and defend special abilities to report systematically on specific domains.

Advanced projects

Our understanding of potential applications of AI in news is still nascent, not only because of the rapid development of new functionality but also because we have just begun to explore the potential of these tools for news work.

The projects described above are easily possible right now, with existing functionality, but there are also several ‘near frontiers’ of functionality that will likely open up significant new potential. One of these is the advent of multi-modal functionality, which is already available in limited forms in Bing Chat, MidJourney and soon GPT-4, and is likely to become increasingly powerful for applications that cross between language and visual information.

A second near frontier is the advent of LLM ‘agents’, pioneered by small examples like AutoGPT and BabyAGI . These approaches use LLMs to deconstruct high-level tasks expressed in vague terms into small, specific, actionable tasks that are then carried out by the LLM. They offer intriguing possibilities for automating some investigative journalism, and for scaling investigative reporting into an ongoing and systematic function.

The AI strategies and specific AI projects described here illustrate that newsrooms have tangible and specific options for moving forward towards an AI-mediated information ecosystem, but these strategies and projects are insufficient. Producing professional AI-enabled news products, using AI-enabled workflows, at sufficient scale to make a difference, day-after-day and month-after-month, requires something more. It requires infrastructure.

3. Infrastructure for an AI-ready newsroom

Old-school AI infrastructure

In the decade prior to the rise of large language models, infrastructure for AI in news organisations meant something different than it does today. It meant data warehouses and data lakes, a well-structured and well-maintained metadata schema, libraries of embeddings, an expensive data science team, a large monthly AWS bill and a product roadmap focused on training small, specialised ‘machine learning’ models from scratch using small volumes of proprietary data.

These roadmaps often included business-focused models predicting propensity to subscribe, propensity to churn or willingness-to-pay, journalist-focused models enabling a host of special functions useful for a handful of special stories, and audience-focused models such as semantic search and, of course, different kinds of recommender systems.

This kind of AI infrastructure is still very valuable and useful, even if affordable only by a small number of elite news organisations, but it is very different from the infrastructure required to apply generative AI.

Professionalised prompt management

A fundamental and permanent requirement for applying generative AI to news work is infrastructure that enables the professional development, testing and deployment of prompts.

AI models will be a permanent part of the future of news, and controlling those models in the service of useful journalistic work will be a central function of editorial organisations.

That control will be exercised through prompts. Whether back-end tasks, language tasks or knowledge tasks, and whether employed as part of an efficiency strategy, a product expansion strategy or a product differentiation strategy, all applications of generative AI in newsrooms are fundamentally dependent not just on the models used to execute them, but also on the prompts used to direct those models.

Permanent, professional mastery of prompts does not look like journalists casually cutting-and-pasting from a dozen options in a Google Doc into ChatGPT, but instead looks like a professional ‘prompt-to-publish’ pipeline that enables systematic and quality-controlled management of every aspect of prompting, outputs, editing and deployment.

This includes prompt design, assembly, evaluation and testing, ‘certification’, metadata, storage and retrieval, versioning, iterative improvement, usage tracking, analytics, output editing, training and more. Even just prompt design can involve explicit task definition, application of system roles and ‘custom instructions’, development of few-shot examples, management of context size, prompt templating, multi-prompt staging and more.

Just evaluating the outputs of prompts applied to stochastic models fed by diverse source documents presents a combinatorial editing challenge unlike anything previously seen in news work. All of this requires infrastructure – databases, tools, user interfaces, schemas, integration, processes, analytics, training and documentation.

Interfaces between prompts and journalistic tasks

Assuming that adequate ‘prompt-to-publish’ infrastructure is in place, a newsroom still requires an interface between this infrastructure and its journalists.

For many journalists this is unlikely to be the raw prompt, which for useful tasks will likely be long, quite complex and probably ‘certified’ as tested and reliable according to some accepted quality control process. Instead most journalists will likely access prompts via buttons and controls that produce draft outputs for editing and refinement.

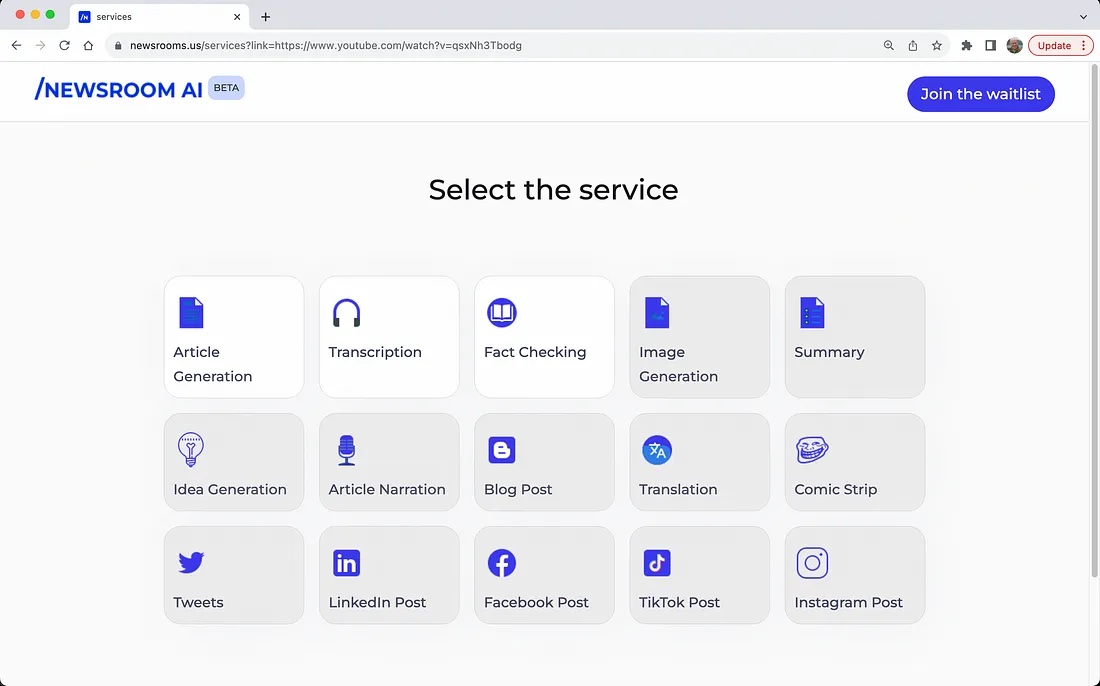

Such interface infrastructure could consist of either stand-alone journalistic ‘co-pilot’ tools with separate experiences for prompt management and prompt use – something already seen in Google’s ‘Genesis’ interface , in various ‘News AI’ tools from start-ups and in some in-house tools developed by newsrooms. It will also require a comprehensive integration into an organisation’s existing content management infrastructure or possibly even as an entirely new form of CMS designed specifically for AI workflows.

Maintaining control of these tools, of the buttons and functions they provide, and of the prompts behind those buttons will likely be critical for journalistic independence in an AI-mediated news ecosystem.

Infrastructure for personalised experiences

Even with a coherent strategy, a set of applications that support that strategy and a prompt management process that professionalises the execution of those applications, the extent of AI-enabled news production will still be limited by the available content management, serving and distribution infrastructure.

This is especially true of a product expansion strategy executed using language tasks or medium-to-medium transformations.

Producing 5, 10 or 20 different variants of every story, suitable for a wide variety of audiences, situations and consumption contexts, might be far easier than actually serving each of those variants to the right user at the right time. This is a personalisation challenge, but one that is quite different from the usual interpretation of ‘personalisation’ in most newsrooms – which tends to focus almost exclusively on personalised recommendations of one-size-fits-all content artefacts.

This new requirement is, instead, for personalisation of the story experience, and it therefore requires infrastructure that can store, select and serve different variants of a story to different users or different user segments in different situations – in addition to continuing to recommend relevant stories.

A simple form of experience personalisation, being pursued by several newsrooms, is to set up a separate channel or even an entirely separate brand from which to serve a newsroom’s stories in new AI-generated formats.

A more advanced form is to offer direct user control over their consumption experience, for example in the way that the Artifact news app offers article consumption as summaries, simplified text, emoji stories, poems or as audio readings by celebrities (see illustration above).

A more complex form of experience personalisation is to automatically adapt a user’s experience using behavioural data and contextual signals.

Each of these approaches can open up access to a newsroom’s journalism to more people, but each also requires infrastructure that can support the management and serving of story variants.

News-gathering infrastructure

Infrastructure is also required to take advantage of opportunities to use LLMs to substantially scale news-gathering by monitoring and analysing large volumes of source documents – perhaps as part of a differentiation strategy focused on competitively defensible coverage of a particular news domain.

A starting point is infrastructure that enables constant access to source material, which might exist in different text formats, or in audio or video form that must first be converted to text transcripts using AI speech-to-text tools, or possibly even in large datasets that are frequently updated. Such ‘monitoring’ infrastructure might range from a simple list of sources to a complex web crawler that continually ‘reads’ portions of the internet to maintain an awareness of domain events.

The monitoring that such infrastructure performs will depend on a system of prompts and a system that manages the summaries and assessments that are the outputs of such prompts.

This all requires databases, data schemas, access tools and filtering functionality. Such functionality can be built at a small scale and used as a supplement to a manual monitoring workflow, and several newsrooms are already doing so.

Infrastructure flexibility

Despite our efforts to identify a useful way forward amid the uncertainty of the present moment, there remains a real possibility that AI might enable an entirely new interface to journalism, delivering experiences of news that are not centred on discrete text, audio or video artefacts.

We see early signs of this in the form of chat interfaces, generative search and early conversational voice interfaces enabled by language models. Despite the caution provided above regarding an archive chatbot strategy, and despite evidence from audience research indicating a preference for passive rather than active news consumption, it is still possible that we may soon be interacting with news in entirely new ways.

Given this uncertainty, it may be useful for news organisations to reexamine their technical architectures and infrastructure strategy from the perspective of an increasing need for flexibility. This might involve reexamining build-vs-buy decisions, refactoring brittle, tightly coupled architectures, or even attempting to identify various possible product scenarios and a path to infrastructure that could support those scenarios if they develop.

Any such reevaluation should consider the many new options for AI-enabled software architectures and AI-enabled software engineering that are appearing. The increasing need for flexible infrastructure is accompanied by new AI-enabled techniques that may make it easier to design, build and maintain such infrastructure.

4. Organisational structure for AI-empowered teams

News organisations will need to operate differently

A news organisation with a coherent, well-articulated strategy for responding to generative AI, delivered via a portfolio of well-conceived applications supported by a professionalised prompt management process and delivered to audiences via a personalised publishing stack would clearly be well-placed to adapt to an AI-mediated information environment.

But such an organisation would also likely need to operate differently from a traditional digital news publisher, and its organisational structure would probably need to change substantially in order to support those differences. Furthermore, the skills and talent required to operate successfully in this environment are likely to also be different.

Discussions of likely changes in the structure of news organisations often focus on the potential for AI to either replace or augment traditional jobs. But the reality is likely to be more complicated than that.

It is quite certain that many newsroom tasks will be either replaced or made moot by AI, but it is also certain that many new tasks will appear. It is obviously difficult at this stage to predict how old and new tasks will be assembled into individual jobs, teams and department-level functions, and different newsrooms with different strategies will clearly do this differently. Nonetheless we can make some informed speculation using the likely drivers of organisation change as a starting point.

Drivers of organisational change

If we consider what generative AI can do, how it is being used for news applications in a nascent way and how news organisations talk about it, then we can make some plausible assumptions about how news organisations might change in response to it:

- It is likely that technology will play a more central role in news organisations than it currently does. It is likely, perhaps less obviously, that the accessibility of generative AI will cause the use and control of technology to be dispersed throughout the organisation rather than concentrated within a team of specialists.

- It is likely that news organisations will place a higher priority on adaptability and constant entrepreneurial innovation.

- It is likely that substantial differences in the productivity of teams and individuals may appear, caused by differential effectiveness in using AI.

- It is likely that, as competition for audience attention increases, news organisations will increasingly value a deep understanding of audiences and their information needs.

- It is likely that, at least for some categories of news, news organisations will focus less on producing individual stories by hand and more on overseeing systems and processes that produce or help produce stories.

The collective organisational influence of all these assumptions can perhaps be summed up in a single word: autonomy. Those teams that adopt and master AI will be able to do much more, with many fewer dependencies on other parts of the organisation.

An AI-native news organisation

The enablement of increased autonomy by AI suggests to me that the productive units of AI-native news organisations might be small, AI-empowered, multi-disciplinary and self-directing teams operating relatively independently from each other and each focused on serving a specific audience or audience need.

In this scenario the organisation itself becomes somewhat federalised, providing an environment within which self-directing teams can be productive and impactful but not directing their work.

This federal organisation provides brand, values, certification of quality, monetisation, financial stability, enabling infrastructure, training and, of course, general strategy. The atomic teams provide adaptability, fast decision making, audience and competitive awareness and, of course, routine production of valued content via AI-augmented workflows.

Implementing such a federalised organisational structure would clearly be challenging for many news organisations, not least because of that eternal and vaguely-defined bugbear of newsroom change management: culture.

A practical, near-term response being explored by some pioneering newsrooms is the possibility of becoming a ‘two-speed organisation’, taking advantage of the new autonomy available from AI to set up teams that are loosely coupled to existing workflows. A longer-term response, already underway at several newsrooms, is to re-evaluate hiring and performance criteria to emphasise the skills and talents needed to form a more autonomous AI-empowered culture.

Skills and talent

The most valued skill in an AI-empowered news organisation will likely be the same as it has been in traditionally configured news organisations.

Editorial judgement – the ability to maintain a keen awareness of the deep informational needs of an audience or society, identify stories that meet those deep needs, verify and contextualise those stories, and then communicate them to audiences in clear and engaging forms – will probably remain the foundation of journalism.

How editorial judgement is exercised, however, may change in ways that require substantial new skills and different talents. These might include an ability to work with abstractions and systems, to analytically understand audiences and their needs, to engage with complexity, and to remain curious and to learn continually.

Organisations will obviously need to identify, support, incentivise and retain their most innovative and adaptable employees, but they will also need to supply those AI-empowered employees with leadership that is perhaps more entrepreneurial, more skilled at motivating and coaching, and perhaps less managerial or political.

Specific technical skills with specific AI tools or models may, surprisingly, be less important due to the near-universal accessibility of the interfaces. Merely operating AI will likely be much easier and therefore less valuable than wielding it skilfully as a genuine superpower.

5. So, what’s next?

The AI moment

The development of generative AI has placed journalism at the cusp of significant change, variously equated to the iPhone moment, the birth of the internet and even the appearance of the printing press.

The significance of the moment has been understood and appreciated by the senior leadership of most newsrooms, and many are already moving forward towards specific initiatives and experiments aimed at preparing for an AI-mediated future.

Considerable attention is rightly being given to potential harms, to the ethics of using AI in journalism, to influencing regulation and legislation, to the potential for AI-created misinformation and disinformation, to education of audiences and ‘AI literacy’ and to the development of early guidelines to orient news organisations as they begin this new transformation of their industry.

This attention is necessary and valuable, but it is not enough. Journalism must also engage with these new tools, explore them and their potential, and learn how to pragmatically apply them in creating and delivering value to audiences.

There are no best practices, textbooks or shortcuts for this yet, only engaging, doing and learning until a viable way forward appears. Caution is advisable, but waiting for complete clarity is not. So-called ‘ second mover advantage ’ is only available to those who are well-prepared to move when the time comes.

The next information ecosystem

Looking further ahead, the need for hands-on familiarity with applied AI in journalism becomes even more critical because of the likelihood that the entire information ecosystem within which journalism exists will undergo transformation.

What will journalism look like, for example, in an environment in which text, audio and video is fluid and malleable to the preferences of each individual consumer? What should the tangible output of a newsroom be in an environment in which that output is consumed primarily by machines? How will a coherent record of news – an archived ‘first draft of history’ – be maintained in such an environment? What might news become when useful reporting can be done on almost every word of text or speech, or every byte of data, produced in public by society? How will newsrooms capture value from their work in such an environment? What will that work be?

These questions, and others that are similarly fundamental, may not become relevant for years, or even decades, but merely participating meaningfully in that discussion will require newsrooms to possess far more tangible expertise of AI-augmented journalism than any now possess.

Progress in the face of uncertainty depends on developing and maintaining options, but options require situational awareness, and situational awareness comes from authentic engagement with the environment. For journalism that environment will almost certainly be shaped by AI.

In this article I have attempted to describe a few ways in which news organisations might build on the awareness of AI that they have developed since the launch of ChatGPT with specific strategies, projects, infrastructure and organisational changes.

These suggestions are my own interpretation of what I am observing and hearing, and they are by no means exhaustive or complete. It would be reasonable to expect people who staff or lead news organisations to exhibit frustration or even resentment at the prospect of even more impending change, but this is not what I have observed.

Instead the predominant tone of my conversations about AI has been one of optimism and excitement, largely at the opportunity presented by AI to further realise an ideal of journalism that motivates many of us who work in and around newsrooms. If you could bring that ideal to life, without regard for the scarcity of resources, where would you start?

David Caswell is a consultant, builder and researcher focused on AI in news. David has led news product innovation at the BBC, Tribune Publishing & Yahoo! and publish peer-reviewed work. He is a regular speaker of our newsroom leadership programmes . This piece, which was written entirely by hand and without the use of AI, was first published here .

At every email we send you'll find original reporting, evidence-based insights, online seminars and readings curated from 100s sources - all in 5 minutes.

- Twice a week

- More than 20,000 people receive it

- Unsubscribe any time

signup block

How the news ecosystem might look like in the age of generative ai.

Is ChatGPT a threat or an opportunity for journalism? Five AI experts weigh in

Will AI-generated images create a new crisis for fact-checkers? Experts are not so sure

AI, lies and conspiracy theories: How Latinos became a key target for misinformation in the US election

AI deepfakes, bad laws – and a big fat Indian election

Latest News

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Does Journalism Have a Future?

By Jill Lepore

The wood-panelled tailgate of the 1972 Oldsmobile station wagon dangled open like a broken jaw, making a wobbly bench on which four kids could sit, eight legs swinging. Every Sunday morning, long before dawn, we’d get yanked out of bed to stuff the car’s way-back with stacks of twine-tied newspapers, clamber onto the tailgate, cut the twine with my mother’s sewing scissors, and ride around town, bouncing along on that bench, while my father shouted out orders from the driver’s seat. “Watch out for the dog!” he’d holler between draws on his pipe. “Inside the screen door!” “Mailbox!” As the car crept along, never stopping, we’d each grab a paper and dash in the dark across icy driveways or dew-drunk grass, crashing, seasonally, into unexpected snowmen. “Back porch!” “Money under the mat!” He kept a list, scrawled on the back of an envelope, taped to the dashboard: the Accounts. “They owe three weeks!” He didn’t need to remind us. We knew each Doberman and every debt. We’d deliver our papers—Worcester Sunday Telegrams —and then run back to the car and scramble onto the tailgate, dropping the coins we’d collected into empty Briggs tobacco tins as we bumped along to the next turn, the newspaper route our Sabbath.

The Worcester Sunday Telegram was founded in 1884, when a telegram meant something fast. Two years later, it became a daily. It was never a great paper but it was always a pretty good paper: useful, gossipy, and resolute. It cultivated talent. The poet Stanley Kunitz was a staff writer for the Telegram in the nineteen-twenties. The New York Times reporter Douglas Kneeland, who covered Kent State and Charles Manson, began his career there in the nineteen-fifties. Joe McGinniss reported for the Telegram in the nineteen-sixties before writing “The Selling of the President.” From bushy-bearded nineteenth-century politicians to baby-faced George W. Bush, the paper was steadfastly Republican, if mainly concerned with scandals and mustachioed villains close to home: overdue repairs to the main branch of the public library, police raids on illegal betting establishments—“ Worcester Dog Chases Worcester Cat Over Worcester Fence ,” as the old Washington press-corps joke about a typical headline in a local paper goes. Its pages rolled off giant, thrumming presses in a four-story building that overlooked City Hall the way every city paper used to look out over every city hall, the Bat-Signal over Gotham.

Most newspapers like that haven’t lasted. Between 1970 and 2016, the year the American Society of News Editors quit counting, five hundred or so dailies went out of business; the rest cut news coverage, or shrank the paper’s size, or stopped producing a print edition, or did all of that, and it still wasn’t enough. The newspaper mortality rate is old news, and nostalgia for dead papers is itself pitiful at this point, even though, I still say, there’s a principle involved. “I wouldn’t weep about a shoe factory or a branch-line railroad shutting down,” Heywood Broun, the founder of the American Newspaper Guild, said when the New York World went out of business, in 1931. “But newspapers are different.” And the bleeding hasn’t stopped. Between January, 2017, and April, 2018, a third of the nation’s largest newspapers, including the Denver Post and the San Jose Mercury News , reported layoffs. In a newer trend, so did about a quarter of digital-native news sites. BuzzFeed News laid off a hundred people in 2017; speculation is that BuzzFeed is trying to dump it. The Huffington Post paid most of its writers nothing for years, upping that recently to just above nothing, and yet, despite taking in tens of millions of dollars in advertising revenue in 2018, it failed to turn a profit.

Even veterans of august and still thriving papers are worried, especially about the fake news that’s risen from the ashes of the dead news. “We are, for the first time in modern history, facing the prospect of how societies would exist without reliable news,” Alan Rusbridger, for twenty years the editor-in-chief of the Guardian , writes in “ Breaking News: The Remaking of Journalism and Why It Matters Now .” “There are not that many places left that do quality news well or even aim to do it at all,” Jill Abramson , a former executive editor of the New York Times , writes in “Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts.” Like most big-paper reporters and editors who write about the crisis of journalism, Rusbridger and Abramson are interested in national and international news organizations. The local story is worse.

First came conglomeration. Worcester, Massachusetts, the second-largest city in New England, used to have four dailies: the Telegram , in the morning, and the Gazette , in the evening (under the same ownership), the Spy , and the Post . Now it has one. The last great laying waste to American newspapers came in the early decades of the twentieth century, mainly owing to (a) radio and (b) the Depression; the number of dailies fell from 2,042 in 1920 to 1,754 in 1944, leaving 1,103 cities with only one paper. Newspaper circulation rose between 1940 and 1990, but likely only because more people were reading fewer papers, and, as A. J. Liebling once observed, nothing is crummier than a one-paper town. In 1949, after yet another New York daily closed its doors, Liebling predicted, “If the trend continues, New York will be a one- or two-paper town by about 1975.” He wasn’t that far off. In the nineteen-eighties and nineties, as Christopher B. Daly reports in “ Covering America: A Narrative History of the Nation’s Journalism ,” “the big kept getting bigger.” Conglomeration can be good for business, but it has generally been bad for journalism. Media companies that want to get bigger tend to swallow up other media companies, suppressing competition and taking on debt, which makes publishers cowards. In 1986, the publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle bought the Worcester Telegram and the Evening Gazette , and, three years later, right about when Time and Warner became Time Warner, the Telegram and the Gazette became the Telegram & Gazette , or the T&G , smaller fries but the same potato.

Next came the dot-coms. Craigslist went online in the Bay Area in 1996 and spread across the continent like a weed, choking off local newspapers’ most reliable source of revenue: classified ads. The T&G tried to hold on to its classified-advertising section by wading into the shallow waters of the Internet, at telegram.com, where it was called, acronymically, and not a little desperately, “ TANGO !” Then began yet another round of corporate buyouts, deeply leveraged deals conducted by executives answerable to stockholders seeking higher dividends, not better papers. In 1999, the New York Times Company bought the T&G for nearly three hundred million dollars. By 2000, only three hundred and fifty of the fifteen hundred daily newspapers left in the United States were independently owned. And only one out of every hundred American cities that had a daily newspaper was anything other than a one-paper town.

Then came the fall, when papers all over the country, shackled to mammoth corporations and a lumbering, century-old business model, found themselves unable to compete with the upstarts—online news aggregators like the Huffington Post (est. 2005) and Breitbart News (est. 2007), which were, to readers, free. News aggregators also drew display advertisers away from print; Facebook and Google swallowed advertising accounts whole. Big papers found ways to adapt; smaller papers mainly folded. Between 1994 and 2016, years when the population of Worcester County rose by more than a hundred thousand, daily home delivery of the T&G declined from more than a hundred and twenty thousand to barely thirty thousand. In one year alone, circulation fell by twenty-nine per cent. In 2012, after another round of layoffs, the T&G left its building, its much reduced staff small enough to fit into two floors of an office building nearby. The next year, the owner of the Boston Red Sox bought the newspaper, along with the Boston Globe , from the New York Times Company for seventy million dollars, only to unload the T&G less than a year later, for seventeen million dollars, to Halifax Media Group, which held it for only half a year before Halifax itself was bought, flea-market style, by an entity that calls itself, unironically, the New Media Investment Group.

The numbers mask an uglier story. In the past half century, and especially in the past two decades, journalism itself—the way news is covered, reported, written, and edited—has changed, including in ways that have made possible the rise of fake news, and not only because of mergers and acquisitions, and corporate ownership, and job losses, and Google Search, and Facebook and BuzzFeed . There’s no shortage of amazing journalists at work, clear-eyed and courageous, broad-minded and brilliant, and no end of fascinating innovation in matters of form, especially in visual storytelling. Still, journalism, as a field, is as addled as an addict, gaunt, wasted, and twitchy, its pockets as empty as its nights are sleepless. It’s faster than it used to be, so fast. It’s also edgier, and needier, and angrier. It wants and it wants and it wants. But what does it need?

The daily newspaper is the taproot of modern journalism. Dailies mainly date to the eighteen-thirties, the decade in which the word “journalism” was coined, meaning daily reporting, the jour in journalism. Early dailies depended on subscribers to pay the bills. The press was partisan, readers were voters, and the news was meant to persuade (and voter turnout was high). But by 1900 advertising made up more than two-thirds of the revenue at most of the nation’s eighteen thousand newspapers, and readers were consumers (and voter turnout began its long fall). “The newspaper is not a missionary or a charitable institution, but a business that collects and publishes news which the people want and are willing to buy,” one Missouri editor said in 1892. Newspapers stopped rousing the rabble so much because businesses wanted readers, no matter their politics. “There is a sentiment gaining ground to the effect that the public wants its politics ‘straight,’ ” a journalist wrote the following year. Reporters pledged themselves to “facts, facts, and more facts,” and, as the press got less partisan and more ad-based, newspapers sorted themselves out not by their readers’ political leanings but by their incomes. If you had a lot of money to spend, you read the St. Paul Pioneer Press; if you didn’t have very much, you read the St. Paul Dispatch .

Unsurprisingly, critics soon began writing big books, usually indictments, about the relationship between business and journalism. “When you read your daily paper, are you reading facts or propaganda?” Upton Sinclair asked on the jacket of “ The Brass Check ,” in 1919. In “ The Disappearing Daily ,” in 1944, Oswald Garrison Villard mourned “what was once a profession but is now a business.” The big book that inspired Jill Abramson to become a journalist was David Halberstam’s “ The Powers That Be ,” from 1979, a history of the rise of the modern, corporate-based media in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Halberstam, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting from Vietnam for the New York Times , took up his story more or less where Villard left off. He began with F.D.R. and CBS radio; added the Los Angeles Times , Time Inc., and CBS television; and reached his story’s climax with the Washington Post and the New York Times and the publication of the Pentagon Papers, in 1971.

Halberstam argued that between the nineteen-thirties and the nineteen-seventies radio and television brought a new immediacy to reporting, while the resources provided by corporate owners and the demands made by an increasingly sophisticated national audience led to harder-hitting, investigative, adversarial reporting, the kind that could end a war and bring down a President. Richard Rovere summed it up best: “What The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Time and CBS have in common is that, under pressures generated internally and externally, they moved from venality or parochialism or mediocrity or all three to something approaching journalistic excellence and responsibility.” That move came at a price. “Watergate, like Vietnam, had obscured one of the central new facts about the role of journalism in America,” Halberstam wrote. “Only very rich, very powerful corporate institutions like these had the impact, the reach, and above all the resources to challenge the President of the United States.”

Link copied

There’s reach, and then there’s reach. When I was growing up, in the nineteen-seventies, nobody I knew read the New York Times , the Washington Post , or the Wall Street Journal . Nobody I knew even read the Boston Globe , a paper that used to have a rule that no piece should ever be so critical of anyone that its “writer could not shake hands the next day with the man about whom he had written.” After journalism put up its dukes, my father only ever referred to the Globe as “that Communist rag,” not least because, in 1967, it became the first major paper in the United States to come out against the Vietnam War.

The view of the new journalism held by people like my father escaped Halberstam’s notice. In 1969, Nixon’s Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, delivered a speech drafted by the Nixon aide Pat Buchanan accusing the press of liberal bias. It’s “good politics for us to kick the press around,” Nixon is said to have told his staff. The press, Agnew said, represents “a concentration of power over American public opinion unknown in history,” consisting of men who “read the same newspapers” and “talk constantly to one another.” How dare they. Halberstam waved this aside as so much P.R. hooey, but, as has since become clear, Agnew reached a ready audience, especially in houses like mine.

Spiro who? “The press regarded Agnew with uncontrolled hilarity,” Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., observed in 1970, but “no one can question the force of Spiro T. Agnew’s personality, nor the impact of his speeches.” No scholar of journalism can afford to ignore Agnew anymore. In “ On Press: The Liberal Values That Shaped the News ,” the historian Matthew Pressman argues that any understanding of the crisis of journalism in the twenty-first century has to begin by vanquishing the ghost of Spiro T. Agnew.

For Pressman, the pivotal period for the modern newsroom is what Abramson calls “Halberstam’s Golden Age,” between 1960 and 1980, and its signal feature was the adoption not of a liberal bias but of liberal values: “Interpretation replaced transmission, and adversarialism replaced deference.” In 1960, nine out of every ten articles in the Times about the Presidential election were descriptive; by 1976, more than half were interpretative. This turn was partly a consequence of television—people who simply wanted to find out what happened could watch television, so newspapers had to offer something else—and partly a consequence of McCarthyism . “The rise of McCarthy has compelled newspapers of integrity to develop a form of reporting which puts into context what men like McCarthy have to say,” the radio commentator Elmer Davis said in 1953. Five years later, the Times added “News Analysis” as a story category. “Once upon a time, news stories were like tape recorders,” the Bulletin of the American Society of Newspaper Editors commented in 1963. “No more. A whole generation of events had taught us better—Hitler and Goebbels, Stalin and McCarthy, automation and analog computers and missiles.”

These changes weren’t ideologically driven, Pressman insists, but they had ideological consequences. At the start, leading conservatives approved. “To keep a reporter’s prejudices out of a story is commendable,” Irving Kristol wrote in 1967. “To keep his judgment out of a story is to guarantee that the truth will be emasculated.” After the Times and the Post published the Pentagon Papers, Kristol changed his spots. Journalists, he complained in 1972, were now “engaged in a perpetual confrontation with the social and political order (the ‘establishment,’ as they say).” By 1975, after Watergate, Kristol was insisting that “most journalists today . . . are ‘liberals.’ ” With that, the conservative attack on the press was off and running, all the way to Trumpism—“the failing New York Times,” “CNN is fake news,” the press is “the true enemy of the people”—and, in a revolution-devouring-its-elders sort of way, the shutting down of William Kristol’s Weekly Standard , in December. “The pathetic and dishonest Weekly Standard . . . is flat broke and out of business,” Trump tweeted. “May it rest in peace!”

What McCarthy and television were for journalism in the nineteen-fifties, Trump and social media would be in the twenty-tens: license to change the rules. Halberstam’s Golden Age, or what he called “journalism’s high-water mark,” ended about 1980. Abramson’s analysis in “Merchants of Truth” begins with journalism’s low-water mark, in 2007, the year after Facebook launched its News Feed, “the year everything began to fall apart.”

“ Merchants of Truth ” isn’t just inspired by “The Powers That Be”; it’s modelled on it. Abramson’s book follows Halberstam’s structure and mimics its style, chronicling the history of a handful of nationally prominent media organizations—in her case, BuzzFeed, Vice, the Times , and the Washington Post —in alternating chapters that are driven by character sketches and reported scenes. The book is saturated with a lot of gossip and glitz, including details about the restaurants the powers that be frequent, and what they wear (“Sulzberger”—the Times ’ publisher—“dressed in suits from Bloomingdale’s, stylish without being ostentatiously bespoke, and wore suspenders before they went out of fashion”), alongside crucial insights about structural transformations, like how Web and social-media publishing “unbundled” the newspaper, so that readers who used to find a fat newspaper on their front porch could, on their phones, look, instead, at only one story. “Each individual article now lived on its own page, where it had a unique URL and could be shared, and spread virally,” Abramson observes. “This put stories, rather than papers, in competition with one another.”

This history is a chronicle of missed opportunities, missteps, and lessons learned the hard way. As long ago as 1992, an internal report at the Washington Post urged the mounting of an “electronic product”: “The Post ought to be in the forefront of this.” Early on, the Guardian started a New Media lab, which struck a lot of people as frivolous, Rusbridger writes, because, at the time, “only 3 per cent of households owned a PC and a modem,” a situation not unlike that at the Guardian’s own offices, where “it was rumored that downstairs a bloke called Paul in IT had a Mac connected to the internet.” A 1996 business plan for the Guardian concluded that the priority was print, and the London Times editor Simon Jenkins predicted, “The Internet will strut an hour upon the stage, and then take its place in the ranks of the lesser media.” In 2005, the Post lost a chance at a ten-per-cent investment in Facebook, whose returns, as Abramson points out, would have floated the newspaper for decades. The C.E.O. of the Washington Post Company, Don Graham, and Mark Zuckerberg shook hands over the deal, making a verbal contract, but, when Zuckerberg weaseled out of it to take a better offer, Graham, out of kindness to a young fella just starting out, simply let him walk away. The next year, the Post shrugged off a proposal from two of its star political reporters to start a spinoff Web site; they went on to found Politico. The Times , Abramson writes, declined an early chance to invest in Google, and was left to throw the kitchen sink at its failing business model, including adding a Thursday Style section to attract more high-end advertising revenue. Bill Keller, then the newspaper’s editor, said, “If luxury porn is what saves the Baghdad bureau, so be it.”

More alarming than what the Times and the Post failed to do was how so much of what they did do was determined less by their own editors than by executives at Facebook and BuzzFeed. If journalism has been reinvented during the past two decades, it has, in the main, been reinvented not by reporters and editors but by tech companies, in a sequence of events that, in Abramson’s harrowing telling, resemble a series of puerile stunts more than acts of public service.

Who even are these people? “Merchants of Truth” has been charged with factual errors, including by people Abramson interviewed, especially younger journalists. She can also be maddeningly condescending. She doffs her cap at Sulzberger, with his natty suspenders, but dismisses younger reporters at places like Vice as notable mainly for being “impossibly hip, with interesting hair.” This is distracting, and too bad, because there is a changing of the guard worth noting, and it’s not incidental: it’s critical. All the way through to the nineteen-eighties, all sorts of journalists, including magazine, radio, and television reporters, got their start working on daily papers, learning the ropes and the rules. Rusbridger started out in 1976 as a reporter at the Cambridge Evening News , which covered stories that included a petition about a pedestrian crossing and a root vegetable that looked like Winston Churchill. In the U.K., a reporter who wanted to go to Fleet Street had first to work for three years on a provincial newspaper, pounding the pavement. Much the same applied in the U.S., where a cub reporter did time at the Des Moines Register , or the Worcester Telegram , before moving up to the New York Times or the Herald Tribune. Beat reporting, however, is not the backstory of the people who, beginning in the nineteen-nineties, built the New Media.

Jonah Peretti started out soaking up postmodern theory at U.C. Santa Cruz in the mid-nineteen-nineties, and later published a scholarly journal article about the scrambled, disjointed, and incoherent way of thinking produced by accelerated visual experiences under late capitalism. Or something like that. Imagine an article written by that American Studies professor in Don DeLillo’s “ White Noise .” Peretti thought that watching a lot of MTV can mess with your head—“The rapid fire succession of signifiers in MTV style media erodes the viewer’s sense of temporal continuity”—leaving you confused, stupid, and lonely. “Capitalism needs schizophrenia, but it also needs egos,” Peretti wrote. “The contradiction is resolved through the acceleration of the temporal rhythm of late capitalist visual culture. This type of acceleration encourages weak egos that are easily formed, and fade away just as easily.” Voilà, a business plan!

Peretti’s career in viral content began in 2001, with a prank involving e-mail and Nike sneakers while he was a graduate student at the M.I.T. Media Lab. (Peretti ordered custom sneakers embroidered with the word “sweatshop” and then circulated Nike’s reply.) In 2005, a year the New York Times Company laid off five hundred employees and the Post began paying people to retire early, Peretti joined Andrew Breitbart, a Matt Drudge acolyte, and Ken Lerer, a former P.R. guy at AOL Time Warner, in helping Arianna Huffington, a millionaire and a former anti-feminist polemicist, launch the Huffington Post. Peretti was in charge of innovations that included a click-o-meter. Within a couple of years, the Huffington Post had more Web traffic than the Los Angeles Times , the Washington Post , and the Wall Street Journal . Its business was banditry. Abramson writes that when the Times published a deeply reported exclusive story about WikiLeaks, which took months of investigative work and a great deal of money, the Huffington Post published its own version of the story, using the same headline—and beat out the Times story in Google rankings. “We were learning that the internet behaved like a clattering of jackdaws,” Rusbridger writes. “Nothing remained exclusive for more than two minutes.”

Pretty soon, there were jackdaws all over the place, with their schizophrenic late-capitalist accelerated signifiers. Breitbart left the Huffington Post and started Breitbart News around the same time that Peretti left to focus on his own company, Contagious Media, from which he launched BuzzFeed, where he tested the limits of virality with offerings like the seven best links about gay penguins and “YouTube Porn Hacks.” He explained his methods in a pitch to venture capitalists: “Raw buzz is automatically published the moment it is detected by our algorithm,” and “the future of the industry is advertising as content.”

Facebook launched its News Feed in 2006. In 2008, Peretti mused on Facebook, “Thinking about the economics of the news business.” The company added its Like button in 2009. Peretti set likability as BuzzFeed’s goal, and, to perfect the instruments for measuring it, he enlisted partners, including the Times and the Guardian , to share their data with him in exchange for his reports on their metrics. Lists were liked. Hating people was liked. And it turned out that news, which is full of people who hate other people, can be crammed into lists.

Chartbeat, a “content intelligence” company founded in 2009, launched a feature called Newsbeat in 2011. Chartbeat offers real-time Web analytics, displaying a constantly updated report on Web traffic that tells editors what stories people are reading and what stories they’re skipping. The Post winnowed out reporters based on their Chartbeat numbers. At the offices of Gawker, the Chartbeat dashboard was displayed on a giant screen.

In 2011, Peretti launched BuzzFeed News, hiring a thirty-five-year-old Politico journalist, Ben Smith, as its editor-in-chief. Smith asked for a “scoop-a-day” from his reporters, who, he told Abramson, had little interest in the rules of journalism: “They didn’t even know what rules they were breaking.” In 2012, BuzzFeed introduced three new one-click ways for readers to respond to stories, beyond “liking” them—LOL, OMG, and WTF—and ran lists like “10 Reasons Everyone Should Be Furious About Trayvon Martin’s Murder,” in which, as Abramson explains, BuzzFeed “simply lifted what it needed from reports published elsewhere, repackaged the information, and presented it in a way that emphasized sentiment and celebrity.” BuzzFeed makes a distinction between BuzzFeed and BuzzFeed News, just as newspapers and magazines draw distinctions between their print and their digital editions. These distinctions are lost on most readers. BuzzFeed News covered the Trayvon Martin story, but its information, like BuzzFeed’s, came from Reuters and the Associated Press.

Even as news organizations were pruning reporters and editors, Facebook was pruning its users’ news, with the commercially appealing but ethically indefensible idea that people should see only the news they want to see. In 2013, Silicon Valley began reading its own online newspaper, the Information, its high-priced subscription peddled to the information élite, following the motto “Quality stories breed quality subscribers.” Facebook’s goal, Zuckerberg explained in 2014, was to “build the perfect personalized newspaper for every person in the world.” Ripples at Facebook create tsunamis in newsrooms. The ambitious news site Mic relied on Facebook to reach an audience through a video program called Mic Dispatch, on Facebook Watch; last fall, after Facebook suggested that it would drop the program, Mic collapsed. Every time Facebook News tweaks its algorithm—tweaks made for commercial, not editorial, reasons—news organizations drown in the undertow. An automated Facebook feature called Trending Topics, introduced in 2014, turned out to mainly identify junk as trends, and so “news curators,” who tended to be recent college graduates, were given a new, manual mandate, “massage the algorithm,” which meant deciding, themselves, which stories mattered. The fake news that roiled the 2016 election? A lot of that was stuff on Trending Topics. (Last year, Facebook discontinued the feature.)

BuzzFeed surpassed the Times Web site in reader traffic in 2013. BuzzFeed News is subsidized by BuzzFeed, which, like many Web sites—including, at this point, those of most major news organizations—makes money by way of “native advertising,” ads that look like articles. In some publications, these fake stories are easy to spot; in others, they’re not. At BuzzFeed, they’re in the same font as every other story. BuzzFeed’s native-advertising bounty meant that BuzzFeed News had money to pay reporters and editors, and it began producing some very good and very serious reporting, real news having become something of a luxury good. By 2014, BuzzFeed employed a hundred and fifty journalists, including many foreign correspondents. It was obsessed with Donald Trump’s rumored Presidential bid, and followed him on what it called the “fake campaign trail” as early as January, 2014. “It used to be the New York Times , now it’s BuzzFeed,” Trump said, wistfully. “The world has changed.” At the time, Steve Bannon was stumping for Trump on Breitbart. Left or right, a Trump Presidency was just the sort of story that could rack up the LOLs, OMGs, and WTFs. It still is.

In March, 2014, the Times produced an Innovation Report, announcing that the newspaper had fallen behind in “the art and science of getting our journalism to readers,” a field led by BuzzFeed. That May, Sulzberger fired Abramson, who had been less than all-in about the Times doing things like running native ads. Meanwhile, BuzzFeed purged from its Web site more than four thousand of its early stories. “It’s stuff made at a time when people were really not thinking of themselves as doing journalism,” Ben Smith explained. Not long afterward, the Times began running more lists, from book recommendations to fitness tips to takeaways from Presidential debates.

The Times remains unrivalled. It staffs bureaus all over the globe and sends reporters to some of the world’s most dangerous places. It has more than a dozen reporters in China alone. Nevertheless, BuzzFeed News became more like the Times , and the Times became more like BuzzFeed, because readers, as Chartbeat announced on its endlessly flickering dashboards, wanted lists, and luxury porn, and people to hate.