Sri Aurobindo on the Essence of Ethics

Editor’s note: We feature a few selections from the chapter titled ‘The Suprarational Good’ from Sri Aurobindo’s book ‘The Human Cycle’ where he helps us understand the evolution of our ethical impulses and nature from infrarational to rational to suprarational. He reminds us like every other part of our being, the ethical being is also a growth and a seeking towards the absolute, the divine, which can only be attained securely in the suprarational.

Ethics and pursuit of highest utility

Utility is a fundamental principle of existence and all fundamental principles of existence are in the end one; therefore it is true that the highest good is also the highest utility. It is true also that, not any balance of the greatest good of the greatest number, but simply the good of others and most widely the good of all is one ideal aim of our outgoing ethical practice; it is that which the ethical man would like to effect, if he could only find the way and be always sure what is the real good of all.

But this does not help to regulate our ethical practice, nor does it supply us with its inner principle whether of being or of action, but only produces one of the many considerations by which we can feel our way along the road which is so difficult to travel. Good, not utility, must be the principle and standard of good; otherwise we fall into the hands of that dangerous pretender expediency, whose whole method is alien to the ethical.

Moreover, the standard of utility, the judgment of utility, its spirit, its form, its application must vary with the individual nature, the habit of mind, the outlook on the world. Here there can be no reliable general law to which all can subscribe, no set of large governing principles such as it is sought to supply to our conduct by a true ethics. Nor can ethics at all or ever be a matter of calculation.

There is only one safe rule for the ethical man, to stick to his principle of good, his instinct for good, his vision of good, his intuition of good and to govern by that his conduct.

He may err, but he will be on his right road in spite of all stumblings, because he will be faithful to the law of his nature. The saying of the Gita is always true; better is the law of one’s own nature though ill-performed, dangerous is an alien law however speciously superior it may seem to our reason.

But the law of nature of the ethical being is the pursuit of good; it can never be the pursuit of utility.

Ethics and the pursuit of pleasure

Neither is its law the pursuit of pleasure high or base, nor self-satisfaction of any kind, however subtle or even spiritual. It is true, here too, that the highest good is both in its nature and inner effect the highest bliss.

Ananda, delight of being, is the spring of all existence and that to which it tends and for which it seeks openly or covertly in all its activities. It is true too that in virtue growing, in good accomplished there is great pleasure and that the seeking for it may well be always there as a subconscient motive to the pursuit of virtue.

But for practical purposes this is a side aspect of the matter; it does not constitute pleasure into a test or standard of virtue.

On the contrary, virtue comes to the natural man by a struggle with his pleasure-seeking nature and is often a deliberate embracing of pain, an edification of strength by suffering. We do not embrace that pain and struggle for the pleasure of the pain and the pleasure of the struggle; for that higher strenuous delight, though it is felt by the secret spirit in us, is not usually or not at first conscious in the conscient normal part of our being which is the field of the struggle.

The action of the ethical man is not motived by even an inner pleasure, but by a call of his being, the necessity of an ideal, the figure of an absolute standard, a law of the Divine.

In the outward history of our ascent this does not at first appear clearly, does not appear perhaps at all: there the evolution of man in society may seem to be the determining cause of his ethical evolution. For ethics only begins by the demand upon him of something other than his personal preference, vital pleasure or material self-interest; and this demand seems at first to work on him through the necessity of his relations with others, by the exigencies of his social existence.

But that this is not the core of the matter, is shown by the fact that the ethical demand does not always square with the social demand, nor the ethical standard always coincide with the social standard.

On the contrary, the ethical man is often called upon to reject and do battle with the social demand, to break, to move away from, to reverse the social standard. His relations with others and his relations with himself are both of them the occasions of his ethical growth; but that which determines his ethical being is his relations with God, the urge of the Divine upon him whether concealed in his nature or conscious in his higher self or inner genius.

He obeys an inner ideal, not an outer standard; he answers to a divine law in his being, not to a social claim or a collective necessity. The ethical imperative comes not from around, but from within him and above him.

Man’s conscience – a creation of his evolving nature

It has been felt and said from of old that the laws of right, the laws of perfect conduct are the laws of the gods, eternal beyond, laws that man is conscious of and summoned to obey. The age of reason has scouted this summary account of the matter as a superstition or a poetical imagination which the nature and history of the world contradict.

But still there is a truth in this ancient superstition or imagination which the rational denial of it misses and the rational confirmations of it, whether Kant’s categorical imperative or another, do not altogether restore.

If man’s conscience is a creation of his evolving nature, if his conceptions of ethical law are mutable and depend on his stage of evolution, yet at the root of them there is something constant in all their mutations which lies at the very roots of his own nature and of world-nature.

And if Nature in man and the world is in its beginnings infra-ethical as well as infrarational, as it is at its summit supra-ethical as well as suprarational, yet in that infraethical there is something which becomes in the human plane of being the ethical, and that supra-ethical is itself a consummation of the ethical and cannot be reached by any who have not trod the long ethical road.

Below hides that secret of good in all things which the human being approaches and tries to deliver partially through ethical instinct and ethical idea; above is hidden the eternal Good which exceeds our partial and fragmentary ethical conceptions.

The infrarational base of ethical impulse

Our ethical impulses and activities begin like all the rest in the infrarational and take their rise from the subconscient. They arise as an instinct of right, an instinct of obedience to an ununderstood law, an instinct of self-giving in labour, an instinct of sacrifice and self-sacrifice, an instinct of love, of self-subordination and of solidarity with others.

Man obeys the law at first without any inquiry into the why and the wherefore; he does not seek for it a sanction in the reason. His first thought is that it is a law created by higher powers than himself and his race and he says with the ancient poet that he knows not whence these laws sprang, but only that they are and endure and cannot with impunity be violated.

What the instincts and impulses seek after, the reason labours to make us understand, so that the will may come to use the ethical impulses intelligently and turn the instincts into ethical ideas.

It corrects man’s crude and often erring misprisions of the ethical instinct, separates and purifies his confused associations, shows as best it can the relations of his often clashing moral ideals, tries to arbitrate and compromise between their conflicting claims, arranges a system and many-sided rule of ethical action.

And all this is well, a necessary stage of our advance; but in the end these ethical ideas and this intelligent ethical will which it has tried to train to its control, escape from its hold and soar up beyond its province. Always, even when enduring its rein and curb, they have that inborn tendency.

Ethical being and limits of Reason

For the ethical being like the rest is a growth and a seeking towards the absolute, the divine, which can only be attained securely in the suprarational.

It seeks after an absolute purity, an absolute right, an absolute truth, an absolute strength, an absolute love and self-giving, and it is most satisfied when it can get them in absolute measure, without limit, curb or compromise, divinely, infinitely, in a sort of godhead and transfiguration of the ethical being.

The reason is chiefly concerned with what it best understands, the apparent process, the machinery, the outward act, its result and effect, its circumstance, occasion and motive; by these it judges the morality of the action and the morality of the doer. But the developed ethical being knows instinctively that it is an inner something which it seeks and the outward act is only a means of bringing out and manifesting within ourselves by its psychological effects that inner absolute and eternal entity.

The value of our actions lies not so much in their apparent nature and outward result as in their help towards the growth of the Divine within us.

It is difficult, even impossible to justify upon outward grounds the absolute justice, absolute right, absolute purity, love or selflessness of an action or course of action; for action is always relative, it is mixed and uncertain in its results, perplexed in its occasions.

But it is possible to relate the inner being to the eternal and absolute good, to make our sense and will full of it so as to act out of its impulsion or its intuitions and inspirations. That is what the ethical being labours towards and the higher ethical man increasingly attains to in his inner efforts.

The heart of the meaning of ethics

In fact ethics is not in its essence a calculation of good and evil in the action or a laboured effort to be blameless according to the standards of the world,—those are only crude appearances,—it is an attempt to grow into the divine nature.

Its parts of purity are an aspiration towards the inalienable purity of God’s being; its parts of truth and right are a seeking after conscious unity with the law of the divine knowledge and will; its parts of sympathy and charity are a movement towards the infinity and universality of the divine love; its parts of strength and manhood are an edification of the divine strength and power. That is the heart of its meaning.

Its high fulfilment comes when the being of the man undergoes this transfiguration; then it is not his actions that standardise his nature but his nature that gives value to his actions; then he is no longer laboriously virtuous, artificially moral, but naturally divine.

Actively, too, he is fulfilled and consummated when he is not led or moved either by the infrarational impulses or the rational intelligence and will, but inspired and piloted by the divine knowledge and will made conscious in his nature. And that can only be done, first by communication of the truth of these things through the intuitive mind as it purifies itself progressively from the invasion of egoism, self-interest, desire, passion and all kinds of self-will, finally through the suprarational light and power, no longer communicated but present and in possession of his being.

Such was the supreme aim of the ancient sages who had the wisdom which rational man and rational society have rejected because it was too high a truth for the comprehension of the reason and for the powers of the normal limited human will too bold and immense, too infinite an effort.

. . . Even in its first instincts it [the cult of the Good] is already an obscure seeking after the divine and absolute; it aims at an absolute satisfaction, it finds its highest light and means in something beyond the reason, it is fulfilled only when it finds God, when it creates in man some image of the divine Reality.

Rising from its infrarational beginnings through its intermediate dependence on the reason to a suprarational consummation, the ethical is like the aesthetic and the religious being of man a seeking after the Eternal.

~ CWSA, Vol. 25, pp. 149-154

Also read: Of God, Universe, Good and Evil

~ Design: Beloo Mehra and Biswajita Mohapatra

Related Posts

God at the Beginning, God in the Middle, God at the End, God Everywhere

From Nature to Supernature

Vāsudevaḥ sarvam iti and Karmayoga

Search Here

- An Introduction to the CSE Exam

- Personality Test

- Annual Calendar by UPSC-2024

- Common Myths about the Exam

- About Insights IAS

- Our Mission, Vision & Values

- Director's Desk

- Meet Our Team

- Our Branches

- Careers at Insights IAS

- Daily Current Affairs+PIB Summary

- Insights into Editorials

- Insta Revision Modules for Prelims

- Current Affairs Quiz

- Static Quiz

- Current Affairs RTM

- Insta-DART(CSAT)

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Prelims 2024

- Secure (Mains Answer writing)

- Secure Synopsis

- Ethics Case Studies

- Insta Ethics

- Weekly Essay Challenge

- Insta Revision Modules-Mains

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Mains

- Secure (Archive)

- Anthropology

- Law Optional

- Kannada Literature

- Public Administration

- English Literature

- Medical Science

- Mathematics

- Commerce & Accountancy

- Monthly Magazine: CURRENT AFFAIRS 30

- Content for Mains Enrichment (CME)

- InstaMaps: Important Places in News

- Weekly CA Magazine

- The PRIME Magazine

- Insta Revision Modules-Prelims

- Insta-DART(CSAT) Quiz

- Insta 75 days Revision Tests for Prelims 2022

- Insights SECURE(Mains Answer Writing)

- Interview Transcripts

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Prelims

- Answer Keys for Prelims PYQs

- Solve Prelims PYQs

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Mains

- UPSC CSE Syllabus

- Toppers from Insights IAS

- Testimonials

- Felicitation

- UPSC Results

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Ancient Indian History

- Medieval Indian History

- Modern Indian History

- World History

- World Geography

- Indian Geography

- Indian Society

- Social Justice

- International Relations

- Agriculture

- Environment & Ecology

- Disaster Management

- Science & Technology

- Security Issues

- Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Enivornment & Ecology

Ethics and Essay Strategy- Saumya Sharma Rank 9, 111 in Ethics and 160 in Essay

Ethics and essay strategy.

Saumya Sharma Rank 9

Marks -111 in Ethics and 160 in Essay

Hello everyone! This post is going to cover my strategy for the ethics and essay papers. I have secured 160 marks in the essay, and 111 marks in ethics. I hope this post helps you.

The ethics and essay papers should be given equal respect as the other general studies papers. Putting in a little extra effort towards these papers has the potential of doing wonders to your overall result. These two papers are where you are given considerable leeway in expressing yourself. If prepared well, they can definitely become an important factor in securing a good rank.

GS4 Ethics preparation:

- 2 nd ARC Report on Ethics in Governance- This report should be read thoroughly as it helps considerably with GS2 as well.

- Vaji Ram’s yellow book on Ethics- It covers the syllabus sufficiently.

- I followed DK Balaji Sir’s strategy given on insightsonindia. Accordingly, I made my own 1-2 page long notes on every keyword given in the syllabus. I wrote about the meaning of that particular value as I understood it. I also added examples from the news, from history and from my own life to enrich my understanding of the values.

- Youtube videos- many channels such as The School of Life have short, informative videos on thinkers. If you are unable to fully grasp any concept of ethics, I would highly recommend watching videos to understand the topic.

- The Difficulty of Being Good by Gurcharan Das- it can be read if you have sufficient time with you. It explains certain concepts in a way that will remain with you long after you have read the book and answered your GS4 exam.

Preparation:

I first finished the syllabus by referring to the above sources. Then, I joined a test series specifically for ethics. The reason for joining a separate ethics test series was that I considered ethics to be one of my strong points and I wanted to make it stronger. Joining a test series also ensured that I covered the entire syllabus in a thorough manner.

In addition to the feedback received from the test series, I used to discuss current events involving ethical behavior (or the lack of it) with my mother, and sometimes with one of my close friends. Those discussions helped immensely, as I was able to formulate a more balanced viewpoint on various issues. I would recommend candidates to discuss and debate issues on which you are unable to take a stand with your peers. It will help you appreciate opposing or varying viewpoints and come to a more rounded conclusion.

Writing answers :

- It is advisable to attempt the case studies first in the GS4 paper. Better solutions can be thought of with a fresh mind. For attempting the paper, time yourself. I had divided my time as follows: 1 hour 45 minutes for the case studies, and 1 hour 15 minutes for the other questions.

- Your solutions to the case studies should be something that you as a future bureaucrat can actually execute and implement. Their practicality is as important as their being ethically correct. In addition to being ethically correct, your solutions should be legally correct. They should be in accordance with the ethos of our constitution.

- Your answer should reflect clarity of thought. It makes it easier for even the examiner to read a solution that is logical and clear. While giving solutions, try giving innovative solutions suited to the case scenario. Multiple courses of action should be given where asked. Give reasoning to support the course of action you finally choose to take. You can also eliminate certain course of actions by providing reasons for the elimination.

- Do not begin your answer by giving a drastic solution to the problem. If you must take some extreme measures, they should be given as a matter of last resort, and never in the first instance. A course of action that gradually gets stricter is better than something that is sudden and drastic.

- Further, your solutions to the case study must reflect that you have actually understood the root cause of the problem. For example, suppose there is failure in the PDS machinery of a district. People are protesting, and have disrupted railway lines, road traffic and are burning buses. Other citizens are suffering terribly because of this, and it is upon you to control the chaos.

In answering this, you should tackle the situation by taking care of the citizens suffering due to the protests. But, you must not forget that the reason the protests are happening is the failure of the PDS machinery. Any solution that does not address the issue of the faulty PDS will be a superficial solution. Don’t get so overwhelmed with the tragic outcomes (in this case, the violent protests) that you fail to address the root cause itself.

- In writing your ethics answers, a certain conviction must be palpable. If you believe in what you are writing, it will be evident. It also makes it easier to answer ethics questions when you truly believe in something. However, make sure that your beliefs are suited for an upright civil servant of independent India, in accordance with our constitutional values of equality, liberty and fraternity.

- You may make diagrams/ flow charts in your answers. However, I did not. I did not make any flow charts or diagrams even in my GS3 final exam (courtesy my sickness which prevented me from revising), and yet managed to score decent marks. I therefore believe that making diagrams or flow charts is not an important requirement for scoring good marks as long as your content is there.

That’s all for ethics. Hope it helps. Now, coming to the essay preparation.

Essay strategy:

Essay paper was the one paper I was most excited to write. I must admit- I was initially taking the essay paper quite lightly. I wrote my first essay at home, and asked my mother to read it. My essay was not received well at all. This much needed wake-up call shocked me out of my complacency. The mistake I had made was that I had written my essay in a manner that was extremely straightforward and quite imbalanced. It also was quite heavy on the legal points, which made it not so pleasant for a non-lawyer to read.

To channel my preparation better, I joined a test series for essay preparation. Practicing essay writing helped a lot and I could see the improvement myself. Here are the things that I learned:

- Essay is the one paper where you can truly demonstrate your values, beliefs and thoughts to the examiner. So use that opportunity wisely. Your essay should have some emotion in it. It helps immensely if you are able to make the reader connect with your essay. This can be achieved by writing a couple of relatable sentences, or giving simple examples that most can relate to.

Further, having a well-informed opinion on issues helps a lot. Just like in ethics, if you strongly believe in something it will be evident in your writing. In both my essays that I wrote (on agriculture and women), I wrote with a strong conviction in my views.

- Choose a topic that you are most comfortable with. Do not avoid writing on a topic simply because you think everyone else would be writing on that topic too.

Before you start writing, spend a minimum of 10 minutes per essay for brainstorming ideas. Think of all possible dimensions to the topic, and jot down the points in the rough space. Make a rough structure before you start writing. The structure you make must be kept flexible to accommodate any fresh points that come to your mind while writing the essay. Don’t make a very detailed structure in the rough space, as that will just end up taking a lot of precious time. Rather, spend time in expanding your points in the actual essay.

- Format : It can be the SPECLIH format (as suggested by Chandramohan Garg Sir ) or past-present-future format. It can be any other format of your liking too. Pick a format that suits the topic and helps you write a cogent essay.

- Introduction: The introduction of the essay should be something which builds the interest of the reader. You can start with a quote, an anecdote, or an ironical statement. Anything that captures the essence of what you’re going to write ahead can be written.

However, do not write a quote just because it will make your essay look good. Quotes should be written only when they have some rational connection with the content. Quotes can also be inserted in the middle of the essay, to further strengthen an argument. Also, if you have started the first essay with a quote, then it is better to start the second essay with something other than a quote. The idea is to not make your two essays seem monotonous in style.

- Content: The content should have a flow to it. The content for the essay will come naturally to you from GS prep. Reading editorials also helps, as you will learn how to make convincing arguments.

Always give both sides of the argument, as it makes your essay balanced. It is better to write about the positives first and then talk about the criticisms. But once you have given both sides of the argument, do take a stand. Do not give the impression that you don’t have your own informed opinion on the issue. Back your opinion with facts, reports etc.

- Optional bias : Most of us will be better placed to write points relating to our optional subject in the essay. But do not let your optional subject knowledge overpower your essay. Use that knowledge judiciously.

A special advice for law background students- do get your essay checked by a non-lawyer, as they will be able to tell you better if your essay is too technical/straightforward.

- Language – Use simple language. Avoid flowery sentences. Your essay should be easy to read in an uninterrupted flow. Do not make it hard for the examiner by writing complicated sentences.

- Conclusion – After you have written your points in the essay, conclude in a forward looking and positive way. The conclusion should be optimistic. The conclusion must also logically flow from the main content. It should not seem that the conclusion is something that you can copy-paste in any essay.

That’s all. There is a lot of scope to maximize your overall mains marks on the basis of essay and ethics paper. Seize this opportunity well. Good luck to all of you!

Here is a link to a photo essay on my UPSC journey (hope this motivates) https://saumya711.wordpress.com/2018/05/08/the-upsc-journey-a-photo-essay/

- Our Mission, Vision & Values

- Director’s Desk

- Commerce & Accountancy

- Previous Years’ Question Papers-Prelims

- Previous Years’ Question Papers-Mains

- Environment & Ecology

- Science & Technology

- +91-7558644556

Ethics Of Dayananda Saraswati And Sri Aurobindo

- Last Updated : 20-Jan-2023

Ten Principles of Arya Samaj

Sri aurobindo ghose, ethics, desire and karma, any suggestions or correction in this article - please click here ( [email protected] ), related posts:, the cultural relativism: explained.

- 01/Jul/2024

The Moral Subjectivism: Explained

- 18/Jun/2024

Secularism – Explained

- 15/Jun/2024

Kantian Ethics And Categorical Imperative

- 04/Jun/2024

Dual Government In Bengal (176

- 108883 Views

- 79926 Views

Civil Disobedience Movement

- 79898 Views

Human Values And Ethics

- 68268 Views

Factors Affecting Economic Gro

Current account deficit - indi, republic as a concept: explain, the cultural relativism: expla.

- TRP for UPSC Personality Test

- Interview Mentorship Programme – 2023

- Daily News & Analysis

- Daily Current Affairs Quiz

- Baba’s Explainer

- Dedicated TLP Portal

- 60 Day – Rapid Revision (RaRe) Series – 2024

- English Magazines

- Hindi Magazines

- Yojana & Kurukshetra Gist

- Gurukul Foundation

- Gurukul Advanced

- TLP Connect – 2025

- TLP (+) Plus – 2025

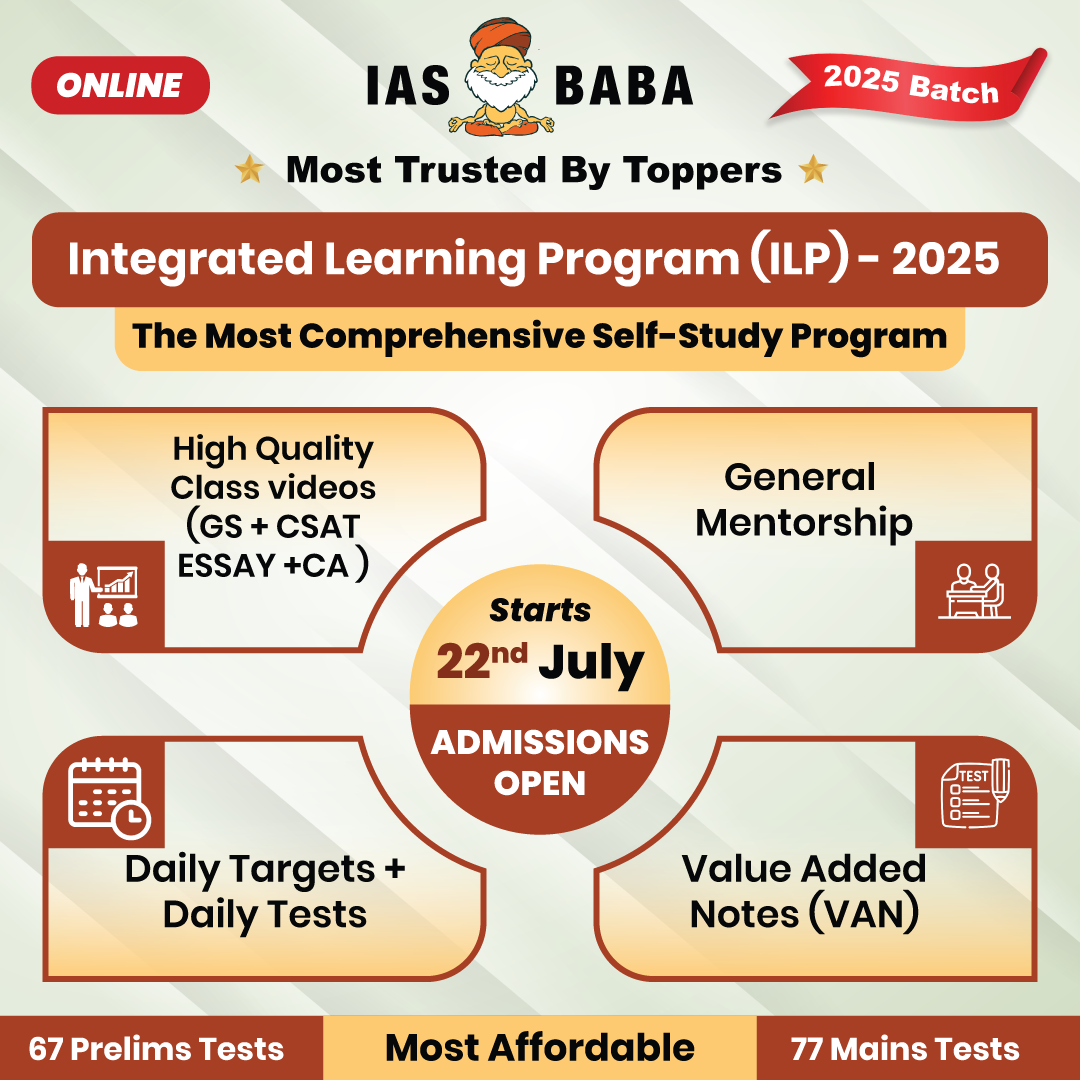

- Integrated Learning Program (ILP) – 2025

- TLP Plus – 2024

- Public Administration FC – 2024

- Anthropology Foundation Course

- Anthropology Optional Test Series

- Sociology Foundation Course – 2024

- Sociology Test Series – 2023

- Geography Optional Foundation Course

- Geography Optional Test Series – Coming Soon!

- PSIR Foundation Course

- PSIR Test Series – Coming Soon

- ‘Mission ಸಂಕಲ್ಪ’ – KPSC Foundation Course

- ‘Mission ಸಂಕಲ್ಪ’ – KPSC Prelims Crash Course

- Monthly Magazine

Category: Ethics and Essay

- June 24, 2023

- Ethics and Essay

- June 21, 2023

- February 11, 2023

- Ethics and Essay , TLP-UPSC Mains Answer Writing

- February 4, 2023

- January 28, 2023

- January 25, 2023

- January 15, 2023

Posts navigation

- 1 2 3 … 5

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 4th July 2024

- IASbaba’s TLP 2024 (Phase 2): UPSC Mains Answer Writing – GS2 Questions [4th July, 2024] – Day 11

- [New Batch] KPSC/KAS 2024 Prelims Crash Course – ‘Mission ಸಂಕಲ್ಪ’ Crack Prelims in 60 Days Starts 8th July | Available ONLINE!

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam – 3rd July 2024

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 3rd July 2024

- IASbaba’s TLP 2024 (Phase 2): UPSC Mains Answer Writing – GS2 Questions [3rd July, 2024] – Day 10

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS IAS | UPSC Prelims and Mains Exam – 2nd July 2024

- MAINS MENTORSHIP with Mohan Sir (Founder, IASbaba) – UPSC Mains 2024!

- UPSC Quiz – 2024 : IASbaba’s Daily Current Affairs Quiz 2nd July 2024

- IASbaba’s TLP 2024 (Phase 2): UPSC Mains Answer Writing – GS2 Questions [2nd July, 2024] – Day 9

Don’t lose out on any important Post and Update. Learn everyday with Experts!!

Email Address

Search now.....

Sign up to receive regular updates.

Sign Up Now !

Lukmaan IAS

A Blog for IAS Examination

"THE 400 DREAMS" (ALL INDIA SCHOLARSHIP TEST)

Courses test series, our selections, toppers’ copy.

Table of Contents

Toppers Copy-2023

Nausheen (air-09).

- ETHICS TEST COPIES ETHICS TEST COPIES

MEDHA ANAND (AIR-13)

- ESSAY TEST COPIES ESSAY TEST COPIES

KUNAL RASTOGI (AIR-15)

Saurabh sharma (air-23), nandala saikiran (air-27), vishnu sasikumar (air-31), ayushi pradhan (air-36), basant singh (air-47), k n chandana jahnavi (air-50), surabhi srivastava (air-56), khushhali solanki (air-61).

- PUBLIC ADMIN. TEST COPIES PUBLIC ADMIN. TEST COPIES

ATUL TYAGI (AIR-62)

Chhaya singh (air-65), kasturi sha (air-68), priya rani (air-69), aniket dnyaneshwar hirde (air-81), prakhar kumar (air-92), toppers copy-2022, uma harathi n (air-03), kritika goyal (air-14), sandeep kumar (air-24), priyansha garg (air-31), sanskriti somani (air-49), sparsh yadav (air-51), richa kulkarni (air-54), maliye sri pranav (air-60), anirudha pandey (air-64), utkarsh ujjwal (air-68), pallavi mishra (air-73).

- GS TEST COPIES GS TEST COPIES

ANJALI GARG (AIR-79)

Siddharth k misra (air-106), rupal srivastava (air-113), manish bhardwaj (air-114), shreya tyagi (air-123), sanket kumar (air-128), khushboo oberoi (air-139), atul tyagi (air-145), b saravanan (air-147), divya pant (air-272), priyanka goel (air-369), manish kansal (air-481), shashank kumar (air-727), srinath t (air-847).

- GS PAPER-II TEST COPIES GS PAPER-II TEST COPIES

JOVIAL PRABHAT (AIR-850)

Socially responsible investing: from the ethical origins to the sustainable development framework of the European Union

- Open access

- Published: 07 April 2021

- Volume 23 , pages 16874–16890, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Alice Martini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6577-3616 1

15k Accesses

38 Citations

Explore all metrics

In this work, we present an overview of the historical development of socially responsible investing (SRI). We will argue that such a financial activity has been boosting in recent decades from a niche, mainly as a religious-led exclusionary practice, towards a mainstream strategy of risk analysis for institutional and retail investors. We also discuss the advances and possible drawbacks that regulatory activity and harmonization process on such industry have achieved at international level in recent years, with a special focus on the European Union. The study shows that the lack of a globally accepted taxonomy on what constitutes sustainable activities, of regulatory clarity and of high-quality data allowing for comparisons across industries and regions, together with practical and behavioural complexities are major critical issues that discourage SRI industry at the global level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Environmental-, social-, and governance-related factors for business investment and sustainability: a scientometric review of global trends

Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: economic analysis and literature review

The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this work, we present an overview of the historical development of socially responsible investing (SRI Footnote 1 ) and evaluate the progress that regulatory activity and harmonization process concerning such financial industry have achieved at international level in recent years, with a special focus on the European Union.

According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (GSIA), SRI is an investment approach that considers environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in portfolio selection and management. GSIA uses an inclusive definition of SRI, without distinctions between this term and related ones, such as ethical investment, responsible investing and social investment. These are collectively referred to as sustainable investing or SRI.

As documented by the GSIA report of 2016, at the beginning of that year $22.89 trillion of assets were professionally managed under responsible investment strategies globally, representing 26% of all professionally managed assets, with an increase of 25% since 2014.

The reasons for this unprecedented growth path are at least twofold. First, the financial crisis of 2007–2008 has increased the awareness about the repercussions that weak corporate governance and risk management practices can have on financial markets and world’s economies. Second, the challenges entailed in the climate change process and depletion of natural resources (as well as air and water pollution and biodiversity loss) have increased demand for more responsible behaviour and coordination at global level from both public and private economic organizations.

As a response, several initiatives have taken place by international organizations to cope with such issues through global governance, which have provided a significant impulse to the SRI industry: for example, in 2006 the UN launched 6 Principles of Responsible Investment (UN PRI), and in 2015, it established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which set out ESG objectives for UN member states. At the Paris Climate Conference in 2015, 195 countries adopted a universal, legally binding global climate agreement, setting out a common action plan to avoid dangerous climate change, by limiting global warming to well below 2 °C and pursuing efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C. Footnote 2 Finally, in several jurisdictions, pension funds, insurance companies and asset managers are required to report on whether and how they take ESG factors into account in their investment activities. Footnote 3

On the other hand, growing empirical evidence has shown that ESG-related issues represent concrete sources of potential risk for investors, so that incorporating ESG criteria in investment strategies should become part of an overall risk analysis aimed at contributing to more stable financial returns. Footnote 4 In the light of these findings, an increasing number of investors, both individual and institutional—such as pension funds, insurance companies and asset managers—have been paying heed to ESG factors in their investment strategies in the last two decades. Significantly, several private-sector organizations have been established to set out global principles for corporate disclosure and reporting on climate-related risks, although on a voluntary basis.

As a matter of fact, Dawkins ( 2016 ) underlines that “the important misgivings regarding the measurement of SRI notwithstanding, it is reasonable to conclude that there are very large sums of money in SRI funds and that it is a matter of importance to investors”.

However, a relevant obstacle to a widespread furthering of SRI is the lack of a universally agreed taxonomy of SRI practices and regulations. The latter elements, besides producing comprehensible confusion among individual investors and intermediaries, also raise concerns on so-called companies’ “green-washing” behaviour. Other open issues concerning SRI development are the lack of standardized data and metrics, given the presence of different classifications from sparse data providers, Footnote 5 which prevents comparisons of SRI practices and performances across time and regions.

Since the early 1990s, different disciplines have been increasingly focusing on the analysis of SRI (see Rizzi et al., 2018 for recent literature), providing a deeper and wider understanding of such phenomenon. Although results are still far from being univocal from an economic point of view, SRI supporters claim that SRI not only allows investors to align their investment choices with their personal motivations, but also provides incentives to firms for voluntarily reducing their negative impact on societies.

While the dispute on SRI within the scientific community is still underway, the European Union is taking a primary role in relation to the global sustainability agenda. Footnote 6 In particular, in recent years the European Commission has launched several ambitious proposals aimed at harmonizing and enhancing the ESG-factor integration within the European Union. These initiatives have produced an ongoing debate between private sector organizations and the European policymakers on what approach (either legislative or market-led, mandatory or voluntary), degree and type of disclosure is needed for institutional investors on ESG factors. For example, concerns have been raised that investment governance standards may be unduly restrictive and so discourage institutional investors from taking ESG factors into account in their analysis, even when ESG integration could lead to more resilient investment portfolios (OECD, 2017 ).

In this work, we will adopt a historical perspective for assessing the evolution of both the concept and practices of SRI, from the origins of mostly religious-related, exclusionary practices, towards a mainstream strategy of risk analysis for institutional investors. By doing so, we aim at shedding new light on the current debate concerning SRI and, in particular, on the above-mentioned initiatives that have been taken at European level, which may represent a significant step towards the furthering of the SRI industry.

The work is organized as follows: in Sect. 2 , we introduce the concept of SRI and retrace the debate on ethical factors in the economic science, which will help understand the current debate within the scientific community and among practitioners on SRI. In Sect. 3 , we will present and evaluate some recent packages proposed by the European Commission. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 The evolution of the concept of SRI

Currently, there is no generally agreed-upon definition on what SRI actually is. Indeed, many authors have documented that the definition of SRI is not univocal (Sparkes, 2001 ; Fowler & Hope, 2007 ; Chatterji et al., 2009 ; Busch et al., 2015 ), so that the issue of how to delimitate and quantify the phenomenon under investigation is worth being explored.

Nicholls ( 2010 ) proposes to consider SRI as a subset of the broader concept of “Social investment” or “Social finance” (SF). The latter, according to Rizzi et al. ( 2018 ), “defines the set of alternative lending and investment approaches for financing projects and ventures, requiring to generate both positive impacts on society, the environment, or sustainable development, along with financial returns […]. The term SF includes a variety of approaches, models and tools such as alternative currencies, community investment, crowd funding, ethical banking, microfinance, social impact bonds, social impact investing, socially responsible investment, venture philanthropy” (Rizzi et al., 2018 , p. 805). SF, according to Nicholls ( 2010 ), encompasses three investment objectives: generating only social and environmental returns (for example, through government spending or support for social movements); generating pure financial returns to capital as in the case of conventional investing (for example, in clean energy stocks). “However, social investment is unique in including a third logic—blended value creation (see Emerson, 2003 )—that combines both an attention to financial return and a focus on social/environmental outputs and outcomes. Blended value creation aims to challenge the Pareto assumption that achieving greater social/environmental impact inevitably reduces financial returns to capital (see Emerson, 2006 and Emerson & Spitzer, 2007 ). Examples of investment for blended value creation include socially responsible investment and mutual finance” (Nicholls, 2010 , pp 75–76).

In the words of Puaschunder ( 2016 ), “financial social responsibility attributes the consideration of CSR [Corporate Social Responsibility, N. o. A. ] in investment decisions […]. Footnote 7 Financial social responsibility bridges the financial world with society in socially responsible investment (SRI). In this asset allocation style, socially conscientious investors select securities not only for their expected yield and volatility, but foremost for social, environmental and institutional ethicality aspects” (p. 39).

Besides the objective difficulties to find a univocally accepted definition of SRI, at international level disparate SRI practices have emerged, influenced by specific national legislations, policy objectives and cultural customs (Reinhardt et al., 2008 ; Steurer, 2010 ), with the risk to make both the concept and the practices of SRI rather blurred and inconclusive and raising concerns for “green-washing” or “ESG-washing” as part of the barriers to SRI development. As a matter of fact, with no stringent legal international basis, SRI activities are in fact mandated by national, federal, state, or local laws and regulations.

Trying to clarify the issue concerning SRI practices, we recall that SRI encompasses activities that range from simple exclusions to general integration of ESG factors into traditional financial risk analysis. More precisely Footnote 8 :

screening (negative/exclusionary screening, positive/best-in-class screening, norms-based screening);

sustainability themed investing;

impact investing;

community investing;

integration of ESG factors;

corporate engagement and shareholder action/advocacy.

To some extent, the debate on the definition on SRI reflects the fact that, on one hand, both the scope and the practices encompassed by SRI have significantly changed over time and that, on the other hand, the ethical nature of SRI might be considered as too generic and muddled, dependent on the context (society) in which it is applied. Footnote 9 Moreover, the economic science, especially in the last century, has been traditionally uncomfortable with “ethics”, for the reasons that we will discuss in the next sub-section.

2.1 From ethical investment to socially responsible investment

Several authors emphasize the ethical foundations of SRI (in fact ethical investing was the term originally used to describe SRI—e.g. Domini, 1984 ; Simon et al., 1972 ) relative to conventional investing activity. For example, according to Richardson and Cragg ( 2010 ), SRI investors reflect the view that they have ethical responsibilities, so that they temper investment return by corporate responsibility, and to that end, they try to exert ethical influence over the firms they invest in. However, while “ethical investment” could in fact well describe the decision process of such value-based organizations in applying internal ethical principles to an investment strategy, some authors doubt that the same term could be applied to the profit maximizing behaviour of fund management companies supplying ethical unit trusts (Anderson, 1996 ). As Cowton ( 1994 ) posed it: “at one level, ethical investment can be seen as just another product innovation that helps widen choice […]. The irony is that its occurrence can be explained in pure, profit-seeking capitalistic terms, as financial institutions seek to influence and exploit their environment in the interests of profitability. Thus individual investors, potentially at least, have their values met or satisfied by institutions/people who do not share these values at all, whose sole motive might be to make more money” (p. 228).

Moreover, others consider the term “ethical” to be incorrect because it could imply that the mainstream approaches to investment are “unethical” (Purcell, 1980 ). Following this reasoning, the term “socially responsible investment” could allow to avoid such preconceptions and facilitate a broader, more positive approach to nonfinancial considerations being adopted by investors.

Revelli ( 2016 ) even argues that the recent evolution has led SRI towards a financial approach where ethics is guided by finance and proposes a model to incorporate the financial aspect of SRI in ethical values that should help formalize investments promoting impact measurement and extra-financial performance.

As mentioned, this debate finds its reason, among other things, in the difficulty of using the term “ethical” to describe investment issues or, more precisely, the difficulty of introducing ethical factors into economics and economic behaviour, a long-disputed issue that is worth being sketched in the next sub-section.

2.2 The ethical factor in the economic science and finance

For a long time, the economic science has not been comfortable with ethical issues. The rich debate of nineteenth century within the economic science led to the formulation of new methodological and epistemological foundations, according to which economics is a real “science” that enjoys the same status of the experimental sciences.

According to this view, economics needed to be liberated from elements that are considered “outsiders” (ideological, ethical, metaphysical or political), in order to be able to identify and formulate—through the use of empirical observation, the logical-deductive method and the mathematical tool—economic laws that are general and invariant with respect to the types of organization of the economy and society. Footnote 10 For example, Jevons ( 1888 ) wrote that he aimed to “treat Economy as a Calculus of Pleasure and Pain, the form which the science, as it seems to, must ultimately take" ( Preface ). By the same lines, Leon Walras, in his Elements of Pure Economics , claimed that “pure theory of economics is a science which resembles the physic-mathematical sciences in every respect” ( 1874 [2013], p. 71). According to this approach, individuals derive and seek their satisfaction from the relationship of pleasure or pain with things, while elements such as altruism, compassion and social connections disappear, although with some exceptions, from the description of social and economic behaviour. For example, Keynes ( 1904 3 ) writes: “it’s true that our economic activities are subject to the influence of a variety of motives, which sometimes strengthen and sometimes counteract one another, [but] it is also true that in economic affairs the desire for wealth exerts a more uniform and an indefinitely stronger influence amongst men taken in the mass that any other immediate aim […]. It is legitimate and even indispensable to begin by tracing the result of this desire under the supposition that it operates without check” (p. 119).

Hence, the utilitarian methodology of economics could work without any reference to external moral values, as it shares with the classical Smithian vision (or the neoclassical interpretation of Smith’s view) the substantial coincidence between individual interest and collective interest (expressed through the famous metaphor of the “invisible hand”). Footnote 11 Personal interest and pleasure are the result of the will and of personal freedom, but they are not mediated in any way by reference to other principles that inform human beings and their living together. Decisions and actions are also independent of any historical and institutional context.

The debate on the necessity to distinguish between “pure” and “applied economics” has continued in subsequent years, especially in the form of a debate between the proponents of laissez faire and those of state intervention; however, the principle of “neutrality” of economic science has not been basically questioned for quite a long time.

In fact, some authors have recently argued that this approach has been a reductionist interpretation of the classical economic thought. Amartya Sen ( 1987 ), for example, argues that “[o]ther parts of Smith's writings on economics and society, dealing with observations of misery, the need for sympathy and the role of ethical considerations in human behaviour, particularly the use of behaviour norms, have become relatively neglected as these considerations have themselves become unfashionable in economics” (p. 28). Footnote 12

However, we can say that since the nineteenth century, the reductionist interpretation of the classical approach has prevailed, so that from that moment onwards economics would be completely separated from virtue and ethics. A famous example of such an approach is an article that Milton Friedman wrote for the New York Times Magazine in 1970, Footnote 13 arguing that public companies possess only minimal ethical obligations (e.g. to operate within the societal ethical frame, to avoid deception and fraud) beyond maximizing profits and obeying the law. Footnote 14 Friedman’s view is well in line with the traditional optimal portfolio theory pioneered by Markowitz ( 1952 ), according to which restricting an investment universe (for any reason) should be avoided in investment decisions because it would reduce the efficiency gains of diversification.

In support of Friedman’s view, Rudd ( 1981 ) argues that the performance of a constrained/screened portfolio, as in the case of SRI, is generally lower, in that, for example, SRI introduces size and other biases that, by reducing diversification, will produce relatively greater extra-market covariation in returns. Hence, Rudd questions the very legitimacy of social responsibility criteria: “there is one important difference between social responsibility criteria and others. The latter are imposed on the manager solely by the investment considerations. It is true that they may be misguided, but the underlying rationale is defensible; namely, the aim is to protect the financial condition of the beneficiaries. Few of the social responsibility criteria have this property” (p. 61). On the same lines, Grossman and Sharpe ( 1986 ) argue that any constraint placed on a portfolio can only reduce or leave unchanged the maximum utility obtainable through an investment decision.

However, in the last decades, several branches of the literature have tried to pursue alternative approaches to the mainstream neoclassical one, with emphasis on the psychological element. For example, behavioural economy unveiled, through experimental and fields studies, evidence of pro-social behaviour or limited rationality among individuals (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010 ; Meier, 2007 ). The role of institutions and of social capital (Keefer & Knack, 2008 ) and of CSR companies behaviour (Crifo & Forget, 2015 ) has been highlighted as crucially affecting individuals’ behaviour and collective outcomes, too.

To date, the research lines that have moved away from the so-called mainstream approach to use a less partial and more realistic view of the homo oeconomicus , while remaining within individualism and admitting different degrees of rationality or altruism, have not provided yet general models and theorems that can redefine fundamental economic phenomena such as production, consumption and distribution. Although lacking the descriptive and prescriptive power of the neoclassical theorems, these studies have opened promising avenues for research, which seem particularly suitable for modern economics and finance.

Finally, within the neoclassical framework, recent economic theory proves that social welfare might not be maximized if some externalities (e.g. environmental pollution) are not priced at all, so that public intervention is called for to correct such market-failure, typically through Pigouvian taxation or environmental regulation. Footnote 15 In fact, a growing body of literature has shown that ESG factors can represent material risks for both productive companies and financial investors, so that their integration within the traditional risk analysis, while facilitating sustainable development, is increasingly considered essential for the achievement of successful performances in the long run. Footnote 16

Also (or perhaps mainly) for all these reasons, the term “ethical investment” has increasingly been replaced, over the last ten years, by the term “socially responsible investment” or “sustainable investment”. Footnote 17

2.2.1 History and evolution of SRI practices

Several authors have documented that SRI can be traced back to its religious origins, going back to the Hebrew Bible, over 2000 years ago. Footnote 18

Social screening of investment opportunities has emerged in the religious communities of pre-revolutionary America, when Methodist communities, followed by the Quakers, screened out investment opportunities in the so-called “sin stocks”, that is companies involved in the industry of tobacco, gambling or alcohol, or were involved in slavery.

From the seventeenth until the mid-twentieth century, SRI remained a religiously centred, small movement and was basically focused on negative screening to avoid investment in “sin industries”. Footnote 19

The protests of students and young people against the Vietnam War in the 1960s led to a boycott campaign against companies that provided weapons used in the war and alerted institutional investors to sell napalm-producing Dow Chemical shares (Biller, 2007 ). Footnote 20 The latter campaigns, together with protests and proposals on civil rights and democratic participation, helped SRI to come out from the universe of religious activism, so that, together with the establishment of Community development banks that were settled in low-income or minority communities, they started to be identified as the beginning of modern SRI. Footnote 21

In 1971, the First Spectrum Fund was established, promising no investment would be made without analysing companies’ performance in “the environment, civil rights and the protection of consumers”. On the same lines, the Dreyfus Third Century Fund , established in 1972, had a prospectus stating that it was looking for companies that “show evidence in the conduct of their business, relative to other companies in the same industry or industries, of contributing to the enhancement of quality of life in America”. In the mid-1970s, Reverend Leon Sullivan, a civil rights activist and director of General Motors , organized a broad movement of opinion and organization of the shareholding of some large corporations and launched investment principles whereby US companies operating in South Africa would have to apply to their local workers the same rules as those for American employees. The investment principles launched by Sullivan were followed by massive financial boycott and extensive pressure on the managers and boards of American multinationals involved in South Africa.

In 1982, Joan Bavaria founded the Trillium Asset Management , a firm that defines itself as the “oldest independent investment advisor devoted exclusively to sustainable and responsible investing”.

In the following years, SRI was focused on screening initiatives in South Africa with the goal of pressuring the South African government to end apartheid , as well as on divestiture strategies against the Angolan repressive government. Footnote 22 In addition to playing a role in political activism, in the same years SRI began to increase its influence in mainstream investment, with positive screening strategies starting in the beginning of the 1990s.

One of the first SRI indexes is The Domini 400 Social Index (now MSCI KLD 400 Social Index) launched in May 1990, a capitalization weighted index of 400 US securities that provides exposure to companies with outstanding ESG ratings and excludes companies whose products have negative social or environmental impacts. Among the other currently existing indexes, we want to cite the Dow Jones Sustainability Index , Ethibel , FTSE4 , Humanix and Jantzi .

In 2015, the US Department of Labor issued a clarifying guidance on ESG integration, confirming that fiduciaries may legitimately consider ESG factors if they have an impact on financial risks and provided that the overall decision-making process is in line with existing standards.

Similarly, as for non-US countries, the 2011 Amendment to the Pension Funds Act of South Africa states that “prudent investing should give appropriate consideration to any factor which may materially affect the sustainable long-term performance of a fund’s assets, including factors of an environmental, social and governance character”.

As for the European market, UK has the largest number of SRI funds in Europe, although the first ethical retail fund in Europe (i.e. available to all investors) was Ansvar Aktiefond Sverige , founded in 1965 in Sweden (Mill, 2006 ).

The above documented development of SRI, while providing new opportunities in terms of financial social market options, also caused a large disparity of SRI practices. For these reasons, in early 2000s the United Nations have launched a program using a bottom-up (or more pragmatic) approach, inviting a group of the world’s largest institutional investors to join a network aimed to codify SRI practices and put them into practice. Signatory institutions were asked to subscribe six Principles of Responsible Investments (PRI), launched in April 2006 at the New York Stock Exchange and concerned with ESG issues, such as human rights and climate change, that are meant to provide a general framework for mainstream investors to consider these ESG issues. Initiatives for boosting SRI at global level have also been taken by the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, which are major issuers of labelled and themed bonds through their Sustainable Development Bonds and other structured products.

However, in most OECD countries regulatory frameworks for institutional investors (pension funds, insurance companies and asset managers) do not make explicit reference to ESG factors, although with some notable exception. In general, incorporation of ESG factors in investment governance is allowed to the extent that they are expected to have a material impact on financial performance. Consequently, it is up to institutional investors to decide whether and to what extent ESG integration is consistent with the usual standards of behaviour, such as prudence and risk control.

A relevant exception is presented by the French legislation, according to which from 2017 institutional investors (and—more in general—companies), must report on the financial risks they face in relation to the consequences of climate change and on the measures taken to reduce these risks.

As for corporate disclosure on ESG factors, in several countries companies are required to report on whether and how they take ESG factors into account, although in most cases it is not mandatory (i.e. in the form “comply or explain”). Footnote 23 On the other hand, a number of organizations and initiatives (also practitioner-led ones) have emerged in recent years in order to facilitate the consistent disclosure and integration of ESG factors by companies and asset managers. For example, the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) initiative has the objective since 2015 to deliver voluntary, consistent climate-related financial risk disclosures to be used by companies in providing information to investors, lenders, insurers and other stakeholders. The final report of the TCFD was released in June 2017, containing four widely adoptable recommendations on climate-related financial disclosures that are applicable to organizations across sectors and jurisdictions.

Another recent official initiative is the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), launched, on a voluntary basis, at the Paris One Planet Summit in December 2017.

As a comment, it is worth noting that although a major critique against the above-mentioned initiatives is their voluntary nature and their lack of external monitoring and sanction mechanisms, some studies have shown that investors may be able to pressure signatories to increase their compliance with the disclosure requirements and to “walk the talk”. Footnote 24

However, regulatory, practical and behavioural barriers to more widespread SRI remain. The lack of harmonization and common definitions is one of the most relevant obstacles, because interpretations of ESG vary within the investment communities and across jurisdictions. Moreover, many asset owners argue that the narrow interpretation of fiduciary duty, which considers ESG factors to be nonfinancial and therefore in conflict with the duties of care and loyalty, is still influential, especially in common law countries and, hence, is a primary obstacle to ESG integration (PRI, 2015 ).

3 SRI in the European Union

As highlighted in Eurosif ( 2018 ), in the European Union the increase in demand for SRI today, also from retail clients, is not matched by adequate product offer, given the difficulties arising from specific legislation concerning financial services, such as the Markets in Financial Instruments Directives (MIFID I and II) and the Regulation on Markets in Financial Instruments (MIFIR). In fact, the latter acts still contain no specific requirements to embed ESG factors as part of the investment preferences discussed with the client. Moreover, there are also behavioural motivations due to the fact that many financial advisers still today perceive SRI as presenting a negative trade-off with returns — although the latter is not necessarily true (see Renneboog et al., 2008 for insightful reviews).

For these reasons, in recent years the European Union has undertaken several steps to increase the availability of green funds and boost SRI, which we summarize in the next subsection.

3.1 The European framework for sustainable development

In recent years, the European Commission has launched several initiatives on sustainable development within a framework aimed at putting ESG factors at the heart of the financial system. The aim is to help transforming Europe's economy into a greener, more resilient and circular system.

The framework has its roots in the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change (COP21), the United Nations (UN) 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the EU 2030 Framework for climate and energy, adopted in October 2014. This framework includes also the Investment Plan for Europe, the Circular Economy Package, the Energy Union package, the Capital Markets Union and the EU budget for 2014–2020, comprising the Cohesion fund and research projects. Footnote 25

To sum up, in September 2016, the European Commission proposed the extension of the duration of the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI) until 2020, and in November 2017 the Council confirmed the agreement on such extension (referred to as EFSI 2.0), by earmarking at least 20% of the EU 2014–2020 budget available for climate action. The agreement increases the EU guarantee from 16 billion euro to 26 billion euro and the European Investment Bank (EIB) capital from 5 to 7.5 billion euro, with the objective of mobilizing 500 billion euro of both private and public investment.

Second, in late 2016 the European Commission established the EU High-Level Group on Sustainable Finance to help develop an overarching and comprehensive EU roadmap on sustainable finance. The Group completed its work by publishing a final report in January 2018, suggesting eight recommendations—including the establishment of a EU sustainability taxonomy, i.e. a technically robust classification system at EU level to provide clarity on what is “green” or “sustainable” activity. These recommendations have been at the heart of the initiatives that the European Commission has launched in the subsequent months:

in March 2018, the publication of the Action Plan on Sustainable Finance , with the objective of reorienting capital flows towards sustainable investments in order to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth;

in May 2018, a package of measures implementing several key actions contained in the action plan.

The latter package is meant to integrate sustainability into the suitability obligations arising from several EU Directives, among which the 2014/65/EU (MiFID II) on financial services and the EU Directive 2016/97 (IDD) on insurance distribution. In particular, it includes a proposal for a regulation that establishes the conditions and the framework to gradually create a unified classification system (“taxonomy”) on what can be considered an environmentally sustainable economic activity, to create EU labels for green financial products, to clarify fiduciary duties of asset managers and institutional investors, by introducing disclosure obligations on how institutional investors and asset managers integrate ESG factors in their risk processes, to enhance corporate reporting on climate issues. Finally, in order to help implement its action plan, the Commission set up a Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG) with the specific target of developing:

a EU classification (taxonomy) on environmentally sustainable activities (to be finalized by the end of 2022 by the Commission);

a EU Green Bond Standard;

benchmarks for low-carbon investment strategies;

guidance to improve corporate disclosure of climate-related information. Footnote 26

In September 2017, the European Commission presented a series of proposals to improve the mandates, governance and funding of the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) for banking (European Banking Authority, EBA), for securities and financial markets (European Securities and Markets Authority, ESMA), and for insurance and pensions (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, EIOPA). In particular, the proposal specifically requires the ESAs to take into account ESG factors arising within the framework of their mandate, thus promoting sustainable finance while ensuring financial stability. This proposal is meant to enable the ESAs to monitor how financial institutions identify, report and address risks that ESG factors may pose to financial stability. Moreover, according to such proposals the ESAs will also provide guidance on how EU financial legislation can integrate sustainability considerations and promote the implementation of these rules.

To conclude it is worth remembering that in January 2019, the European Commission published draft rules on how investment firms and insurance distributors should take sustainability issues into account when providing their services. Although the Commission can only officially adopt these draft rules once the proposed package has been approved at EU level, the draft rules are meant to help investment firms and insurance distributors to already prepare to take ESG considerations and preferences into account in their investment advice and portfolio management, and into the distribution of insurance-based investment products.

3.2 The current debate on the EU regulatory initiatives

While public consultations on the proposed packages are still underway, concerns have been raised by category organizations such as the European Fund and Asset Manager Association (EFAMA, 2016 ). The latter, while supporting the goal of enhancing ESG factors disclosure and the proposal of a EU taxonomy, recommends flexibility to allow for innovation and client-driven developments. EFAMA considers SRI as a young, innovative and still developing field, which cannot be captured by a single regime. Hence, it argues that a prescriptive legislative approach, unlike a market-led or self-regulatory approach, will create unintended barriers to market development. Moreover, it claims that the ESG reporting should be an activity of the asset-owner, rather than of the fiduciary investor. The same advice to avoid inflexible or overly prescriptive regulations has been raised by the Securities and Markets Stakeholder Group (SMSG).

As for the proposed amendment of ESAs mandates, some NGO organizations, such as Finance Watch and ShareAction , expressed a negative judgment, arguing that the final legislation should detail a clear mandate—tasks and powers—for the ESAs to conduct analysis on a European-wide basis of ESG factors and ESG considerations into their roles. Also, the European Parliament has criticized the Commission’s proposal, since allegedly the proposal’s chosen approach to ESAs reform is not in line with the impact assessment that the Commission conducted on the topic earlier.

As for the IORP II Directive, it is worth noting that while it includes several new ESG provisions related to areas such as risk management, it does not require the integration of ESG criteria in investment decisions.

However, on 24 July 2018 the European Commission has formally asked EIOPA and ESMA to deliver technical advice (comprising a cost–benefit analysis) on two delegated acts aimed to incorporating sustainability risks (i.e. ESG risks) in the decisions taken and processes applied by financial market participants subject to those rules. On 3rd May 2019, EIOPA submitted its advice to European Commission stating that “sustainability is an area of significant strategic importance. Consequently, EIOPA strongly supports the European Commission's Sustainable Finance Action Plan including the aim to integrate sustainability considerations into the prudential and conduct framework for insurers, reinsurers and insurance distributors”. Footnote 27

Some member states and associations (such as PensionsEurope , representing national associations of pension funds and similar institutions for workplace pensions) have asked that the delegated act concept be deleted from the IORP II Directive amendment proposal, their concern being that amendments made via delegated acts would result in prescriptive rules without any scope for national implementation. Moreover, they oppose the possibility that through delegated acts the same set of rules would be issued for both insurance companies and pension funds. Moreover, they argued against changes to IORP II as the directive—at that time—was still under implementation.

In November 2018, the European Parliament’s economic and monetary affairs committee decided to allow delegated acts under IORP II amendment, while in December 2018, the EU Council has dropped the disputed amendment to the IORP II Directive allowing for delegated acts. Moreover, the texts from the Council and Parliament have differing definitions of sustainability risks. According to PensionsEurope , the latter’s definition even aims to mandate pension schemes to account for externalities in investment decisions.

The Council’s agreement on the disclosure proposal (and on the Commission’s low carbon benchmarks proposal) implies, in any case, that negotiations between the Parliament and the Council, with the Commission acting as arbiter, can begin. In fact, the final sustainable finance legislation will depend on such negotiations, with the Council Presidency and the Parliament to decide the date of start.

As a final comment, while we think that some concerns emerged from institutional investors are sound and need careful consideration, we believe that the initiatives undertaken by the European Union are going in the right direction. On the one hand, the challenges concerning social and environmental sustainability urgently require rapid and decisive interventions for the improvement of the well-being of European society; on the other hand, the success of these regulatory proposals, although capable of possible improvements, may represent a benchmark for the other jurisdictions and for future generations.

4 Conclusions

Despite the structural difficulties of the economic science in taking ethical factors properly into account, the socially responsible investment industry has been flourishing in the last decades, based, on one hand, on the increased demand from retail investors for more responsible behaviour of financial and business sectors and, on the other hand, on the evidence that ESG factors are a material risk for financial investors. All these elements have induced an increasing number of firms to incorporate ESG factors within their overall risk analysis to get more stable financial returns. However, more work on several issues is needed to help a full development of SRI. The lack of a globally accepted taxonomy on what constitutes sustainable activities and of regulatory clarity, practical complexity and behavioural issues are all critical aspects that discourage ESG integration. These elements need to be coupled with increased transparency, Footnote 28 defined standards and improvement of high-quality data availability across industries and regions. In this respect, the establishment of an accountability or overarching governing body could ensure accuracy of reported information and favouring a coordination of the existing corporate reporting initiatives promoted by international associations towards common frameworks. Finally, we have discussed several proposals that the European Union has launched in recent years, within a long-term sustainability framework explicitly following the path paved by the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change and the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The EU initiatives are particularly relevant, although far from being fully implemented: the debate about the trade-off between harmonization and regulatory requirements, on one hand, and freedom and flexibility needs expressed by the financial and insurance associations, on the other hand, is rich and alive.

The way in which the EU will tackle such issues in the next years is likely to represent a significant turning point for the enhancement of SRI at global level and the improvement of well-being for future generations.

For the sake of brevity, the abbreviation SRI in this text stands for both “Socially Responsible Investing” and “Socially Responsible Investment”.

The EU has estimated an investment gap of 180 billion euro per year in order to achieve those targets.

Updated lists of country-level initiatives and international organizations are contained in Blackrock ( 2016 ) and OECD ( 2017 ), and, as for EU countries, in Eurosif ( 2018 ) and Kahlenborn et al. ( 2017 ).

The empirical link between environmental degradation, economic growth and financial development has been extensively analyzed in recent years. For example, economic growth, trade openness and foreign direct investment are generally found to increase environmental degradation (Nasir et al. 2019 ; Pham et al. 2020 ), while financial development and energy use tend to increase CO 2 emissions. On the other hand, R&D expenditures and energy research innovations reduce them (Shahbaz et al., 2019 , 2020 ; Nguyen et al. 2021 ). Nasir et al. ( 2021 ) find that short-term bidirectional causality prevails between economic growth, energy consumption, industrialization and stock market development with CO 2 emissions. Doğan et al. ( 2020 ) find that renewable energy is more suitable for economic growth than non-renewable.

OECD ( 2017 ).

See Parker and Karlsson ( 2017 ).

According to Sparkes ( 2002 ), “corporate social responsibility (CSR) and socially responsible investing are in essence mirror images of each other. Each concept basically asserts that business should generate wealth for society but within certain social and environmental frameworks. CSR looks at this from the viewpoint of companies, SRI from the viewpoint of investors in those companies” (p. 42). See also Marinetto ( 1999 ) and Stutz ( 2018 ).

See Inderst and Stewart ( 2018 ) for a deeper insight.

For a deeper analysis of the reasons behind the heterogeneity both in the definitions and practices of SRI, see Sandberg et al. ( 2009 ).

Sachs ( 2013 ), p. 86 and Guidi ( 2004 ).

On this point see Martini and Spataro ( 2018 ).

See, for example, Smith ( 1853 ).

The title of the article is self-explaining: “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits”.

Hill et al. ( 2007 ).

See, for example, Renström et al. ( 2020 , 2021 ) and Wang et al. ( 2020 ).

See, for example, Laurel-Fois ( 2018 ).

It is worth mentioning that some authors argue that the mainstreaming of SRI has transformed the original goal of “making good” into a quest for profitability (Hellsten and Mallin, 2006 ) and call for a return of SRI back to the primary virtuous logic of a “margin” or niche market (Revelli, 2017 ).

See, for example, Ciocchetti ( 2007 ), pp. 1976–1977. During the centuries, Judaist writings praised ethical monetary conduct and usury was prohibited by the Catholic Church in 1139. Until today Islamic banking has restricted adult entertainment and gambling (Renneboog et al., 2008 ).

The first public offering of a screened investment fund was in 1928 when an ecclesiastical group in Boston established the Pioneer Fund .

See the PAX World Fund , founded in 1971 by the Methodist clergy, that was aimed at divestiture from Vietnam War supporters (Broadhurst et al., 2003 ; Renneboog et al., 2008 ).

Solomon et al. ( 2002 ); Sparkes and Cowton ( 2004 ).

See Schueth ( 2003 ).

See, for example, for the UN Global Compact, the analysis carried out by Amer ( 2018 ).

See the website of the European Commission for further reference: https://ec.europa.eu/info/index_en .

The TEG operated until 30 September 2020 and after the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis has issued a specific statement and a short paper (“5 high-level principles for Recovery & Resilience”), encouraging governments and the private sector to use EU Taxonomy, the Green Bond Standard and the Climate Benchmarks as tools to ensure a 'resilient, sustainable and fair' recovery (see https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/sustainable-finance-technical-expert-group_en ).

https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/content/eiopa-submits-advice-sustainable-finance-european-commission_en .