- 0 Shopping Cart

Nyiragongo Case Study

This case study has been developed to support students studying Edexcel B GCSE Geography.

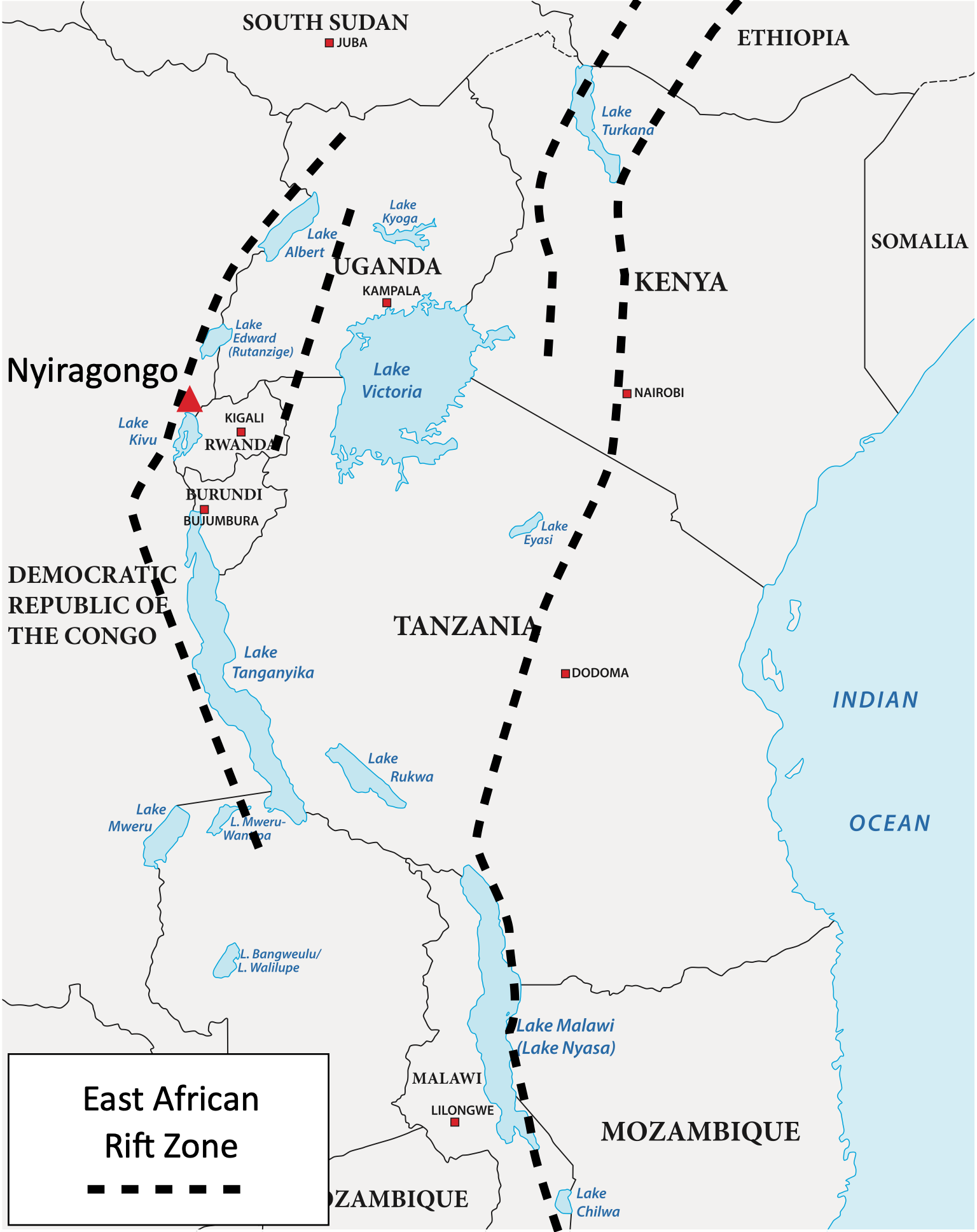

Tectonic Setting and Location

Mount Nyiragongo is a composite volcano located in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The volcano consists of a huge (2km wide) crater, usually filled with a lava lake, and is only 20km away from the city of Goma. Nyiragongo is currently classed as active (2020).

Nyiragongo is located on a divergent plate boundary where the African plate is being pulled apart into the Nubian plate (east) and Somali plate (west), causing lava to rise between. Eruptions are non-explosive as the lava is basaltic, with a low viscosity, which means it is runny and fast flowing (up to 37 mph).

A map to show the location of Mount Nyiragongo

What are the Primary Impacts of Nyiragongo?

The eruption of Mount Nyiragongo in January 2002 had a significant impact on the surrounding area due to huge lava flows.

The primary effects of a volcanic eruption are those caused instantly. These are directly linked to the type of volcano and eruption.

The primary effects of the January 2002 eruption include:

- The lava flow and earthquakes triggered by volcanic activity destroyed 12,500 homes.

- At least 15% of Goma was covered by lava, with one-third of the city being destroyed.

- 80 per cent of the airstrips at Goma International Airport were covered in lava.

- The majority of the 200 deaths were caused by carbon monoxide poisoning from the eruption (this continues to be a threat today).

- The lava flows destroyed crops, and many livestock were killed.

- There were drinking water shortages due to the disruption caused to main water supplies.

- 400,000 people were evacuated from their homes to avoid the lava.

What are the Secondary Impacts of Nyiragongo?

The secondary effects of a volcanic eruption are those that occur in the hours, days and weeks after an eruption.

The secondary effects of the 2002 Nyiragongo eruption include:

- Acid rain fell due to the reaction of volcanic gases in the atmosphere, damaging farmland.

- Refugee camps were overcrowded as many of the 120,000 homeless could not afford to rebuild their homes.

- Overcrowding and poor hygiene conditions led to the spread of cholera in refugee camps.

- The economic impact of the eruption was felt across the region as businesses and shops were destroyed.

- After people evacuated Goma, looting broke out.

How are Nyiragongo’s Hazards Managed?

Management of volcanic hazards includes short-term relief (shelter and supplies) and long-term planning (trained and funded emergency services), preparation (warning and evacuation ; building design) and prediction .

Short-term relief

Approximately 400,000 people were evacuated from the vicinity of the volcano. The pace of evacuation was slow until plumes of smoke from the volcano were visible. The evacuation plans were very limited, many residents had not experienced a volcanic eruption. This led to people heading to the volcano to see the eruption, slowing the evacuation process. As a result, around 50,000 inhabitants of Goma became trapped between two lava flows.

The damage to Goma’s airport disrupted the arrival of international aid .

The United Nations sent 260 tonnes of food to the affected area within a week of the eruption. Families received 26kg of rations each.

UK Oxfam sent 33 tonnes of water-cleansing equipment for 50,000 people in refugee camps. The £150,000 package mainly contained water purification kits to provide clean water for drinking and sanitation. This stopped people from drinking contaminated water from Lake Kivu and helped to reduce the spread of cholera in some refugee camps.

The World Health Organisation and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) conducted emergency measles vaccinations to 28,000 children to stop the spread in refugee camps.

Refugee camps, made from scrap metal, were set up to house the displaced populations.

Communication was poor between agencies and refugees. Many people began to travel back to the affected area within a few days to collect belongings and supplies from their homes, even though it was not yet safe. Some walked across hot lava that was not yet solidified and cooled to get home.

Governments around the world gave $35 million in aid to support refugees.

Long-term planning

Preparation

Thirty new signs that detail the early warning signs of a volcanic eruption have been put up in high-risk areas. Evacuation routes have also been mapped.

Communities and schools now have evacuation drills to prepare people for future eruptions.

Leaflets have been distributed to vulnerable people containing information on evacuation routes, shelters and advice on what to do in an emergency.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies has expressed a need for more funding to release further educational materials to communities in need.

Officials have been retrained and provided with evacuation plans; each has a designated community to support.

Community officers have been trained to relay information to vulnerable communities if an eruption occurs.

Knowledge from similar volcanoes has encouraged vulcanologists to measure carbon dioxide emissions from the volcano and within Lake Kivu to predict if levels will become lethal (as people can die from carbon dioxide poisoning).

An observatory for the volcano, The Observatoire Volcanologique de Goma, constantly monitors the volcano.

The large lava lake in Mount Nyiragongo is visible from above, so its levels can be carefully monitored to see if an eruption is impending.

Premium Resources

Please support internet geography.

If you've found the resources on this page useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Related Topics

Use the images below to explore related GeoTopics.

Topic Home

Next topic page, share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field We invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

Alex Chestnut

Introduction

The First and Second Congo Wars from 1996-1997 and 1998-2003 respectively, have often been considered by historians to be Sub-Saharan Africa’s World Wars. These conflicts have had repercussions on The Democratic Republic of the Congo such that it has not yet fully recovered in the modern era. Each of these respective conflicts experienced sweeping peace agreements with large international participation, and each peace agreement subsequently ended in failure. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest geographic country with the most significant deposits of natural resources in the region, yet it ranks 52 nd out of 54 countries in GDP per Capita by the International Monetary Fund’s annual World Economic Outlook. [1] In addition, the country maintains one of the lowest Freedom House scores in both political rights and civil liberties. [2] Analyzing these peace agreements in conjunction with unique factors to the DRC such as; brutal colonialism, ethnic fracture, and corruption, can provide insight into areas of success and causation of failure in these conflicts.

Colonialism’s Lasting effects on Peace and Stability

It is essential to ground any discussion of modern history in the DRC on study of colonial rule and the vast generational repercussions it placed on the society. Belgian rule of the Congo was markedly brutal leaving deep scars upon the society. Belgium, and its King Leopold II, viciously abused Congolese people creating a society of slavery where the populace was afraid to oppose his role. [3] Leopold believed he could unite the Congo which was deeply divided between Catholic and secular ideologies through French and Flemish traditions including forced language transition. [4] He created a private military group known as the Force Publique which terrorized Congolese laborers forcing extraction of resources. The Force Publique is known to have killed or tortured the families of workers to instill enough fear suppressing any inklings of rebellion. [5]

Belgium ruled the Congo as its official African colony from 1908 until it finally gained independence in 1960. In the latter half of its rule, Belgium instituted policies of urbanization, economic development, educational reform, and an expanded healthcare system.4 However, the colony was still designed to generate wealth for its colonizer leading to forced labor and exploitation.

The Congo experienced 83 years of direct colonial rule which has formed deep transgenerational trauma that exists to this day. Generational trauma is the theory a society or group of people can inherit the pain and suffering of their ancestors subsequently internalizing emotional attachments and generating psychological identity to their ancestor’s trauma. [6] Analysis of modern day conflicts in this region must utilize this theoretical concept to interpret some level of causation. It is evident that decades after the fall of colonial rule, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and its people still harbor emotionally traumatic experiences and real societal scars from occupation. Crisis of identity permeates throughout all levels of the society, leading Congolese peoples to turn to violence multiple times throughout history as they lack proper recourse to repair their cultural traditions.

Zaire and Mobutu

The Belgian-Congo officially gained independence on June 30, 1960, declaring itself the Republic of the Congo and holding democratic elections. Patrice Lumumba was elected as the first Prime Minister of the newly independent nation and Joseph Kasa-Vubu was elected President. However, political chaos quickly ensued later known as the Congo Crisis. This constituted a five-year period from 1960-1965 of political instability and civil wars within the country that saw the nation divided into three parts. Kasa-Vubu led the most powerful political party Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) and quickly dismissed Lumumba from his position as Prime Minister to gain power. This chaos allowed Joseph Mobutu who had been declared the head of the Army by Lumumba to forcibly remove Lumumba from office where he was subsequently executed in 1961 by an American and Belgian backed execution squad of Belgian nationals. Utilizing the resulting power struggle between Tshombe and Kasa-Vubu, Mobutu instituted a coup resulting in his sole leadership. [7] It is important to note that this power struggle was a proxy-war between the United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, with further foreign influence and destabilization efforts on both sides. [8]

Mobutu renamed the country to the Republic of Zaire in 1971. His rule was initially met with widespread support as he generated peace and stability for the newly formed nation. The stability and African nationalism of Mobutu’s regime veiled the severe corruption, widespread human rights violations, political repression, and rampant clientelism that defined his rule. [9] Mobutu faced immense amounts of pressure internally in the 1990s which ultimately forced him to flee the country during the First Congo War in 1997.

Mobutu’s regime is synonymous with corruption, becoming an illustrative example of a trend that has swept through sub-Saharan Africa in subsequent years. Corruption, cronyism, and clientelism were so widespread during this period that their effects have destabilized the state in modern times. While the subsequent wars are the result of a variety of factors, it is undeniable that the extreme corruption of the Mobutu regime created a country which was perfectly situated to experience violent conflict and massive societal upheaval.

Rwandan Genocide

War may have always been brewing in The Congo, but the aftermath of the Rwandan Genocide acted as the official powder keg to spark the conflict. The civil war saw the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups engage in a four-year long struggle for control of Rwanda. Extremist factions in the Hutu government eventually gained power and enacted a genocide against Tutsi, Twa, and moderate Hutu in the country. Approximately 500,000 to 1 million people were slaughtered by the Hutu in just 100 days from April 7 th , 1994 to July 15 th , 1994. The Rwandan government quickly collapsed following the genocide as the Tutsi RPF forces won the Civil War by July of 1994. [10]

The victorious RPF formed a government ousting the Hutu and declaring intent to persecute those responsible for the genocide. By 1996 approximately two million Hutu’s had poured into The Congo fleeing repercussions of the War. They set up refugee camps along the border that housed hundreds of thousands of Hutus. [11] These camps were effectively controlled by the former Hutu regime and military including those who had orchestrated the genocide. These individuals plotted a return to power in Rwanda and a re-ignition of conflict. Zaire provided support and sanctuary to these leaders and by 1996 Hutu military forces were launching steady attacks on Rwanda.

The resulting wars known as the First and Second Congo Wars, or “Africa’s World War” are directly correlated with ethnic tensions that had been brewing for generations in the region. Deep hatred between Hutu and Tutsi exploded into all-out war pitting nine countries and numerous rebel groups against one another in brutal, often chaotic, combat from 1996-2003. Unweaving this complex web of alliances, ethnic groups, and political objectives can provide significant insight into the successes and failures of the resulting peace agreements in both conflicts.

First Congo War

In 1996 with support from Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi, Laurent Kabila led anti-Mobutu forces in capturing large swaths of territory in Eastern Zaire. During this march, Rwandan forces massacred an estimated 200,000 Hutu refugees. [12]

Kabila’s AFDL (Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo) acted as the figurehead for this conflict, but the war was ultimately of Rwanda and Uganda’s making. Zaire proved too weak to oppose the alliance of AFDL, Rwanda and Uganda who took the capital of Kinshasa in 1997, as Mobutu fled the country. Kabila declared himself President in May of 1997, changing the name of the nation from Zaire to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and violently cracking down on opposition. [13]

Second Congo War

Regional alliances collapsed in 1998 as Kabila ousted Rwandan and Ugandan military allies whom he had relied upon to retake The Congo just a year earlier. Kabila turned away from his Tutsi allies, closely embracing the Hutu who are a smaller ethnic subgroup of the larger Bantu speaking peoples who make up an estimated 80% of the DRC. [14] Rwanda subsequently provided military support to the Banyamulenge Tutsi a small ethnic group in Eastern Congo, utilizing ethnic tensions in the region to invade the country. Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi subsequently launched a successful offensive into The DRC capturing large areas of land in the eastern part of the Country. [15]

The DRC allied itself with Zimbabwe, Namibia, Chad, Angola, and Sudan, as well as Anti-Ugandan and Anti-Rwandan militias such as the LRA or Lord’s Resistance Army and FDLR or Democratic Forces for Liberation of Rwanda. A chaotic conflict ensued; with rebel groups often splintering and switching sides as a brutal guerrilla war continued for five years with mass atrocities across the conflict. [16]

Peace Agreements

The UN subsequently responded by facilitating the development and implementation of four peace agreements. The Lusaka Agreement created the first brief ceasefire in 1999 and was built upon following the end of the War in 2003. The Sun City Agreement, signed in April of 2002, provided a framework for governance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo formalizing democratic institutions and elections. [17] The Pretoria Accords signed July of 2002 subsequently created the first peace deal between Rwanda and the DRC, requiring dismantling of Hutu militias and the Rwandan withdrawal from the DRC. [18] Finally, the Luanda Agreement signed in September of 2002 created peace between Uganda and the DRC as Uganda agreed to also withdraw troops from the DRC. [19]

These peace agreements formalized an end to the conflict but have not resulted in the end of violence. While the State actors no longer engage in direct conflict Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC all are actively backing rebel groups who continue the fight to this day. In addition, in 2002 just months after peace agreements were formalized, an estimated 60-100,000 Bambuti pygmies were massacred by Congolese backed groups. [20]

Lusaka Agreement

The first attempt at peace came in 1999 as the UN sent diplomats who created the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement which was signed by the 6 major warring nation states in the region. The UN then deployed 5,000 peacekeeping troops to monitor the ceasefire agreement. However, a large flaw quickly appeared in this agreement as they did not account for the rebel groups who continued the conflict as they were not given a seat at the negotiating table. [21]

Terms of the cease-fire as addressed in the executive summary are: “cessation of hostilities, establishment of a joint military commission (JMC) comprising representatives of the belligerents, withdrawal of foreign groups, disarming, demobilizing and reintegrating of combatants, release of prisoners and hostages, re-establishment of government administration and the selection of a mediator to facilitate an all-inclusive inter-Congolese dialogue. The agreement also calls for the deployment of a UN peacekeeping force to monitor the ceasefire, investigate violations with the JMC and disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate armed groups.” [22]

Critics of the cease-fire often cite the slow deployment of peacekeeping forces and corruption of Laurent Kabila as the key elements that prevented the successful cessation of the conflict. The terms of the agreement are quite effective in de-militarizing and preventing continued conflict. If this agreement were to have been implemented successfully it could have paused hostilities potentially saving thousands of lives and allowing time for conflict practitioners to work towards a long-standing agreement.

Laurent Kabila’s assassination opened the door for renewed interest in the Lusaka Agreement as peacemakers believed his son Joseph Kabila was amenable to the terms and provisions. [23] They alleged Laurent Kabila felt threatened by the Lusaka Agreement as it would destroy his power over the country. [24] The international body failed to address the ethnically driven nature of the conflict as they singularly focused on the political elite. The Lusaka Agreement is the first to demonstrate the clear lack of understanding on the part of international actors in accepting the fractured nature to such a conflict as they instead chose to apply practices of mediation that are acceptable in other less fragmented parts of the world. Peace attempts in this conflict display a trend of lack of comprehension for the unique challenges posed by a large-scale conflict in the Congo region.

Unfortunately, this agreement did not address any of the primary factors that led to conflict and the continuation of hostilities. This was clearly a strategic choice as the international community believe that a pause would give them time to prevent the re-ignition of war, but ultimately history has shown that concrete efforts to address the root causes were required to develop an effective cease-fire. In a war such as this, all sides must be included in a peace process or else it will ultimately end in failure. The UN’s oversight in excluding rebels from the peace process, combined with the weak provision of the Agreement itself, lead to the ultimate continuation of conflict.

The Sun City Agreement

The Sun City agreement is unique in that it set forth to unite conflicting elements within The DRC by creating a unified government. The provisions of this agreement sought to create a positive and transformative political climate for a country that had experienced massive political upheaval over multiple decades. The ensuing negotiations were designed to facilitate dialogue within the country and create an effective democratic system. This has ultimately failed as the Democratic Republic of the Congo continues to be one of the worst offenders on personal and political rights in Africa.

This agreement as its provisions were rather simplistic and designed to transition a conflict-government to a stable post-conflict State. It contained three articles designed to coalesce the fragmented political parties in the Congo which included; re-enforcing the provisions of the Lusaka Agreement, institution of a transitional government, and acknowledgement of the international community’s role in the peace process. [25] While the agreement contained 36 additional adopted resolutions by the parties involved, these all seek to support the three articles contained in the document. The resolutions are far more encompassing in their scope and nature; however, the problem lies with the overarching guidelines of the agreement. The political fragmentation in the DRC included parties backed by rival State actors, extremists, corporations, ethnic groups, and criminal enterprises. In simply instructing these parties to form a government and follow the Lusaka Agreement, the UN failed in its responsibility as mediator to institute sweeping political change. The agreement reads as more of a pat on the back for their effort than a document seeking to formalize a post-conflict State.

Freedom House provides an extremely effective in country report of a State’s political rights and civil liberties. It ultimately assigns a score out of 100 based upon these factors. In its 2019 Freedom in the World Report the organization provided the DRC a score of 15/100. [26] This is one of the lowest scores in their report proving that the Sun City agreement was ultimately ineffective in establishing lasting democratic institutions with political and civil liberties. The Sun City agreement proved to be far too simplistic for the complex and chaotic nature of political realities in the DRC.

A successful agreement would have assigned concrete political procedures and democratic election protocols, quickly enacting these upon the conclusion of the Second War. Instead of simply re-affirming a past agreement and suggesting transitional democratic elections, the UN should have instituted strict rules to be enforced by a multi-national coalition of democracies and regional states. Fight for political power was a core factor that lead to both Congolese Wars. In failing to properly address the inevitable political power grab that would develop following the end of the War, the UN failed to develop an effective agreement. The Sun City agreement has very few redeemable qualities when examined.

Pretoria Accords and Luanda Agreement

The Pretoria Accords set forth to create a permanent peace agreement between Rebel groups and the DRC. Similarly, the Luanda agreement intended to establish permanent peace between Uganda and the DRC. These agreements have both been successful in preventing formalized combat and are held in high regard amongst foreign governments and institutions such as the United Nations. They are heralded as successful peace processes that ended the conflict ushered in peace across the sub-continent. However, while the successes of these peace processes should be studied and built upon, they did not completely solidify an end to conflict in the region. Each agreement lacked concrete provisions to enforce peace, allowing for continued violence across the country. The DRC has since devolved into a proxy for multiple conflicting parties utilizing non-state actors to continue the conflict over ethnic and resource-based grievances. However, it has not resumed full-scale war proving the limited success of both agreements.

Pretoria Accords

The Pretoria Accords or Global and Inclusive Agreement on Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo as it is tilted by the UN sought to “provide a power-sharing formula and transitional arrangements until elections are held” but was really the driving force behind peace between the DRC and Rwanda. Participants in the agreement included; the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD), the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (MLC), the Congolese Rally for Democracy/Liberation/National Movement (RDC/ML), the Mai-Mai, and civil society. Interestingly this agreement included the DRC as the only State actor with rebel groups linked to Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC itself, representing the other parties. Provisions contained within set forth to; end hostilities, formulate transition objectives, implement institutions, set the powers of the three branches of government, and create a military council including all rebel groups. [27]

The Pretoria Accords most successful element was the inclusion of non-state actors involved in the conflict. International peace agreements often exclude non-state actors leading to continued feeling of otherizing for those groups justifying further violence. In his book Making Peace Last, Robert Ricigliano discusses the extreme frustration in the DRC peace process as “one step forward, two steps back”. He and his team of conflict practitioners examined the feedback loop of the negotiation process determined the failures of peace attempts were; “simply working to strengthen the national level negotiations” they discovered that “the real driving force was regional sub-conflict”. [28] This analysis by an expert in the field of sustainable peacebuilding displays the essential nature of focusing on the regional conflicts within the larger War when implementing peace. The Pretoria Accords, while still having flaws, should be built upon as it is the only peace process to focus on these regional conflicts and ensure the participation of all groups involved. The UN made some very successful choices in this process which if expanded in other processes, could have resulted in maintainable peace that works within a systematic peacebuilding process.

If the Accords included a peace process between the States of the DRC and Rwanda, it could have potentially secured peace between these nations. In 2012 the rebel group M23 seized the regional capital of Goma. A subsequent U.S. House of Representative’s Committee on Foreign Affairs investigation in 2015 determined Rwanda had directly controlled the group. [29] This is clear evidence that Rwanda and the DRC continue a proxy war in Eastern Congo that the Pretoria Accords did little to quell. The Peace process may have halted the currently active rebel groups in 2003, however the modern States have continued to sponsor and control new fighting forces as a Cold War-esque conflict exists in the country. The Pretoria process somewhat stemmed the tide of violence between non-state actors but lead to the continuation of the proxy war.

Luanda Agreement

In direct contradiction to the focus of regional conflicts in the Pretoria Accords, the Luanda Agreement focused entirely on peace between the DRC and Uganda. The peace deal included; withdrawal of Ugandan troops from the DRC, state sovereignty, diplomatic cooperation, and social/economic cooperation between nations. [30] This peace process similarly to the Pretoria Accords, is looked upon favorably by the international community as a successful deal that ensured regional peace and stability. It is the direct cause of the cessation of violence between the DRC and Uganda which had been ongoing for decades. The deal certainly has had resounding successes in peace between States but has proved unsuccessful in the regional conflicts around the border between the two nations.

The agreement suffers from the exact opposite successes and failures of the Pretoria Accords; in that it excluded non-State actors leading to continued violence but simultaneously included State actors successfully implementing national peace. Uganda continues to secretly sponsor and control rebel groups in Eastern Congo, but to a lesser degree than Rwanda.

The combined lessons learned in both the Luanda and Pretoria agreements could have been built upon to establish lasting peace between nations and non-state actors. The UN and other foreign conflict practitioners should have formatted each agreement to include the formalized States involved in the conflict, as well as every rebel group.

Future Conflict Resolution

Successes in the peace process in the DRC have been few and far between. The two major successes in the aforementioned peace deals were; the end to formalized State on State conflict in the region, and the engagement of non-state actors in the peace process. However, even these successes are challenged by events in recent years where violence continues to rage on in the eastern part of the country. Future peace deals will need to be massive enterprises tackling the largest issues present in the country and surrounding regions. There needs to be a targeted effort by the international community and the DRC, Rwanda, and Uganda to acknowledge and address the main problems facing each nation to reach a reasonable stage of peace. It is nearly impossible to create an effective peace deal that will solve these issues, however, outlining them creates the possibility to analyze and construct a systematic process to start progress towards this goal.

Corruption and Resource Plundering

The largest intractable source of conflict in the region continues to be the fight for the rich natural resources of the Congo. This has led to the Democratic Republic of the Congo becoming one of the world’s most corrupt states with the leaders in political and military positions trading their power for payoffs. The excellent documentary Virunga which premiered in 2014 provides unparalleled on the ground insight into this problem. The documentary displays evidence of foreign oil companies, mainly SOCO International, plundering Eastern Congo for-profits. The company pays off any corruptible officials that get in their way while simultaneously funding and sponsoring rebel groups to enact violence and instability. They also allegedly attempt to assassinate individuals who get in their way such as Virunga National Park Chief Warden Emmanuel de Merode who was shot in an assassination attempt in 2014. It has also become clear that corporations continue to provide financial support to rebel groups when it suits their interests. SOCO officials are secretly filmed bribing and mentioning illegal acts, while simultaneously supporting the racist neocolonial position that foreign entities should rule over the region. [31] The corporation in the documentary illustrates a microcosm of a greater problem of resource stealing and corruption in the country. Recently this has transformed into state-sponsored resource extraction by entities linked to China who trade the rich resources in the country for economic support projects such as infrastructure.

The film outlines just one region and the natural resource present there. The Congo is so rich in natural resources that it contains various elements desired by foreign entities. These include; precious metals such as diamonds, rare minerals needed in modern technology, and fossil fuels such as oil and gas. Foreign companies and states care little for peace and stability in the region seeking only to extract these resources for profit. Simultaneously many Congolese officials hold immense amounts of power and are easily corruptible leading to the perfect storm of payoffs and bribery. Successful and sustainable peace in the Congo requires these foreign companies to be held accountable for their illegal actions while simultaneously allowing the Congolese people to benefit from the economic prosperity obtainable in the resources and the protection of natural environments where they lie. This would require comprehensive internal and external oversight and the willingness of the UN or other international bodies to prosecute large powerful corporations in international court. The DRC is experiencing cold colonialism as corporate and State entities enact similar policies to Belgian rule in the early 1900s. This is much more difficult to contend with as these groups hide their involvement well but must be countered if there is a reasonable expectation of peace development.

Good Governance and the Rule of Law

The DRC currently lacks comprehensive governance and would need to change for stability and peace. The UN defines eight characteristics leading to good governance in a democratic system including; “it is participatory, consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, effective/efficient, equitable/inclusive and follows the rule of law”. [32] effective peace deals must to build upon the provisions in the Lusaka agreement to transition the DRC into a stable democracy that contains the listed elements. It must restructure its system to focus on de-centralized local political jurisdictions within a greater centralized national system. Starting small in this way at the local level will allow for the facilitation of dialogue and democratic processes that lead to greater participation and accountability in the country. The DRC must also make transparency a key priority to eliminate corruption as mentioned in the previous section.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the Congo must institute a strict and comprehensive legal code that holds all citizens accountable for their actions. The first step in this process should be to institute a universal code of human rights which the country currently lacks. Without this, any legal constitutions would be invalid as individuals can continue violent action disregarding basic human rights. Transition into such a system must begin at the local level as authorities across the country are given leeway to enforce basic laws. This would then ideally transition to the greater legal system, which could institute comprehensive criminal prosecution and a standard legal code. It is important to mention that this legal system must encompass all citizens of the DRC as it is easy for the country to continue systems of corruption, nepotism, and clientelism within a loose legal framework.

In recent years democracy has come under heavy criticism from outside sources who claim that it can lead to continued violence due to its complex and often slow nature. Articles such as: Liberal Peace and Peace-Building: Another Critique [33] and Across the Globe, a Growing Disillusionment With Democracy [34] , outline this concept in detail. It is important to note that polls suggest citizens in the DRC still overwhelmingly support democracy, but this may change with a little substantial transformation in coming years. With the rising influence of China, a more authoritarian, potentially communist, ideology may develop in the country. This is certainly not ideal but would likely lead to faster progress in development and economic stability. The more enticing prospect for the Congo is that they utilize their unique strengths and challenges to develop a new system of governance similar to democracy but that is superior in solving the need for rapid growth and development, while respective of the fragmented ethnocultural society in the country. Such a governmental system is difficult to conceptualize and would require the local citizenry’s unique perspectives and expertise to develop. The international community could help guide the country in this regard but could not overtly control the process as it would need to organically develop.

Ethnic Tension

The current trajectory of best practice in the field of Conflict Analysis points towards the idea that competing ethnic groups often engage in conflict due to their “otherizing” of their opponents. These groups form around similarities in socio-cultural practices creating ethnic tenants which when challenged result in conflict. Utilizing psycho-social study, practitioners have often attempted to understand the complex web of relationships that form social groups in order to combat inevitable violence between them. [35] This however has been challenged recently by some practitioners who through study of post-conflict societies discovered a distinct lack of otherizing in conflict. Gearoid Millar describes this a 2012 study of Sierra Leona where former combatants viewed each other as brothers or friends rather than the “other”. [36] It is essential to conduct full studies into the many ethnic groups involved in this conflict to determine their unique psycho-social relationships to one another. Strategies for attempting resolution cannot be suggested and employed until practitioners hold a clearer understanding of this element of the conflict.

Programs and policies must furthermore be constructed to stop retaliation, while addressing the wrongs committed in the conflict. It is important to balance the desire for retribution with forgiveness to build a future societal structure around positive elements of the competing ethnic groups, minimizing the differences that lead to violence. John Paul Lederach stresses the importance of this balance and building relationships through reconciliation by identifying opposing seemingly incompatible ideas, allowing those ideas space to exist, and embracing them. He additionally stresses the importance of truth and justice in this process as he describes “Mercy alone is superficial. It covers up. It moves on too quickly”. [37] Justice cannot exist without mercy however; the ethnic groups will ultimately need to move past their tensions and forgive one another.

This process is difficult to implement. It will take years of hard work and effort on the part of international peace actors, local communities, and governmental institutions; however, it is possible to unify the competing ethnic groups into a stable societal structure that can transcend the conflict between them. It is equally important to remember the rural ethnic groups such as the pygmy people in this process as they cannot be subjected to further ethnic cleansing or hatred by the larger groups within the country.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo presents one of the most challenging post-conflict peace processes in the world. The country’s complex web of political, societal, ethnic, and economic differences creates an extremely fragmented culture with justifiable cause for continued violence by its many groups. The challenges presented here do not cover the full breadth of intricacies involved in this conflict, but they do represent the largest causes of intractable conflict in the region. With the correct application of new policies, building upon the successes in the peace accords that have come before, and the implementation of some of the suggestions mentioned in this article, it is reasonable to assume the DRC could become a champion of peaceful transition in Africa.

Works Cited

Agreement between the DRC and Uganda on withdrawal of Ugandan Troops, Cooperation and Normalization of Relations between the two countries (Luanda Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, September 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-luandaagreement2002

Ceasefire Agreement (Lusaka Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1999, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-lusaka-agreement99

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO: A LONG-STANDING CRISIS SPINNING OUT OF CONTROL. (1998). Amnesty International , Index number: AFR 62/033/1998.

Foa R., & Mounk Y., (September 2015) Across the Globe a Growing Disillusionment with Democracy, The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/15/opinion/across-the-globe-a-growing d...

Freedom House (January, 2019). The Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Report, Freedom in the World 2019

GANN, L., & Duignan, P. (1979). THE FORCE PUBLIQUE. In The Rulers of Belgian Africa,1884-1914 (pp. 52-84). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt13x17wv.9

Gerard, E., & Kuklick, B. (2015). The Congo of the Belgians. In Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba (pp. 5-18). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press. Retrieved April 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21pxknd.7

Global and Inclusive Agreement on Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Pretoria Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo, July 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-agreementontransition2002

Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies.Vick, K. (2001, January 23). The Ascendant Son in Congo. The Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2001/01/23/the-ascendant... congo/d12ca608-752c-4527-8ecd-cf1388143f17/

Millar, G. (2012). ‘Our brothers who went to the bush’: Post-identity conflict and the experience of reconciliation in Sierra Leone. Journal of Peace Research, 49(5), 717–729. doi:10.1177/0022343312440114

MONUC United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (24 February 2000). Retrieved from: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/monuc/mandate.shtml

Penketh, A. (2004, July 7). Extermination of the pygmies. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/extermination-of-the-pyg...

Prunier, G. (2014). The Rwanda Crisis History of a Genocide. London: Hurst & Company. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/extermination-of-the-pyg... 552332.html

Rentjens, F. (2009). The Great African War: Congo and Regional Geopolitics, 1996–2006. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511596698

Reyntjens, F. (1999). Briefing: The Second Congo War: More than a Remake. African Affairs,98(391), 241-250. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/723629

Ricigliano, R. (2016). Making peace last: a toolbox for sustainable peacebuilding. London:Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Saideman, S. (2001). Understanding the Congo Crisis, 1960–1963¹. In The Ties That Divide: Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Conflict (pp. 36-69). NEW YORK: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/said12228.6

Scramble for the Congo Anatomy of an Ugly War. (20 December 2000). International Crisis Group. Retrieved from: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/democratic republic-congo/scramble-congo-anatomy-ugly-war

STANARD, M. (2011). The Inheritance: Leopold II and Propaganda about the Congo. In Selling the Congo: A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism (pp. 27-46). LINCOLN; LONDON: University of Nebraska Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1df4g39.7

SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS before the COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, House of Representatives 114th Cong. 1 (2015) (Serial Number 114-113). Retrieved From: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA16/20150520/103498/HHRG 114-FA16-Transcript-20150520.pdf

Turner, T. (2001). The Death of Laurent Kabila. Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from https://ips-dc.org/the_death_of_laurent_kabila/

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2000). "Ch. 10: The Rwandan genocide and its aftermath" (PDF). State of the World's Refugees 2000. Retrieved From: https://www.unhcr.org/publ/PUBL/3ebf9bb60.pdf

Virunga. (2014). Directed by Orlando von Einsiedel, Distributed by Netflix

Volkan, V. D. (1997). Blood Lines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Weissman, S. M. (2014). What Really Happened in Congo? The CIA, the Murder of Lumumba, and the Rise of Mobutu. Foreign Affairs, 93(4). doi: 10.1163/2468 1733_shafr_sim160090032

World Economic Outlook (April 14 th , 2020). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, What is Good Governance?, (n.d.) United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/goodgovernance.pdf

Young, C., & Turner, T. (2012). The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. Madison (Wis.): The University of Wisconsin Press.

Zenonas T. (June, 2012) Liberal Peace and Peace-Building: Another Critique The GW PostResearch Paper retrieved from www.thegwpost.com

[1] World economic Outlook, (April 14 th , 2020). Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund,

[2] Freedom House (January, 2019). Freedom in the World 2019 – PDF

[3] STANARD, M. (2011). The Inheritance: Leopold II and Propaganda about the Congo. In Selling the Congo: AHistory of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism (pp. 27-46). LINCOLN; LONDON: University of Nebraska Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1df4g39.7

[4] Gerard, E., & Kuklick, B. (2015). The Congo of the Belgians. In Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba (pp. 5-18). Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press. Retrieved April 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21pxknd.7

[5] GANN, L., & Duignan, P. (1979). THE FORCE PUBLIQUE. In The Rulers of Belgian Africa, 1884-1914 (pp. 52-84). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt13x17wv.9

[6] Volkan, V. D. (1997). Blood Lines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

[7] Saideman, S. (2001). Understanding the Congo Crisis, 1960–1963¹. In The Ties That Divide: Ethnic Politics, Foreign Policy, and International Conflict (pp. 36-69). NEW YORK: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/said12228.6

[8] Weissman, S. M. (2014). What Really Happened in Congo? The CIA, the Murder of Lumumba, and the Rise of Mobutu. Foreign Affairs , 93(4). doi: 10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim160090032

[9] Young, C., & Turner, T. (2012). The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. Madison (Wis.): The University of Wisconsin Press.

[10] Prunier, G. (2014). The Rwanda Crisis History of a Genocide. London: Hurst & Company.

[11] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2000). "Ch. 10: The Rwandan genocide and its aftermath" (PDF). State of the World's Refugees 2000. Retrieved From: https://www.unhcr.org/publ/PUBL/3ebf9bb60.pdf

[12] DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO: A LONG-STANDING CRISIS SPINNING OUT OF CONTROL. (1998). Amnesty International , Index number: AFR 62/033/1998.

[13] Reyntjens, F. (2009). The Great African War: Congo and Regional Geopolitics, 1996–2006. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511596698

[14] The World Factbook: Congo, Democratic Republic of the. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_c...

[15] Reyntjens, F. (1999). Briefing: The Second Congo War: More than a Remake. African Affairs, 98(391), 241-250. Retrieved April 24, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/723629

[16] Scramble for the Congo Anatomy of an Ugly War. (20 December 2000). International Crisis Group. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-co...

[17] Inter-Congolese Negotiations: The Final Act (Sun City Agreement) , The Democratic Republic of the Congo, 02 April 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-suncity-agreement2003

[18] Global and Inclusive Agreement on Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Pretoria Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo, July 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-agreementontransition2002

[19] Agreement between the DRC and Uganda on withdrawal of Ugandan Troops, Cooperation and Normalization of Relations between the two countries (Luanda Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, September 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-luandaagreement2002

[20] Penketh, A. (2004, July 7). Extermination of the pygmies. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/extermination-of-the-pyg...

[21] MONUC United Nations Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (24 February 2000). Retrieved from: https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/monuc/mandate.shtml

[22] Ceasefire Agreement (Lusaka Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1999, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-lusaka-agreement99

[23] Turner, T. (2001). The Death of Laurent Kabila. Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from https://ips-dc.org/the_death_of_laurent_kabila/

[24] Vick, K. (2001, January 23). The Ascendant Son in Congo. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2001/01/23/the-ascendant...

[25] Inter-Congolese Negotiations: The Final Act (Sun City Agreement) , The Democratic Republic of the Congo, 02 April 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-suncity-agreement2003

[26] Freedom House (January, 2019). The Democratic Republic of the Congo Country Report, Freedom in the World 2019

[27] Global and Inclusive Agreement on Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Pretoria Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo, July 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-agreementontransition2002

[28] Ricigliano, R. (2016). Making peace last: a toolbox for sustainable peacebuilding. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

[29] SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS before the COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, House of Representatives 114th Cong. 1 (2015) (Serial Number 114-113). Retrieved From: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA16/20150520/103498/HHRG-114-FA16-Transcript-20150520.pdf

[30] Agreement between the DRC and Uganda on withdrawal of Ugandan Troops, Cooperation and Normalization of Relations between the two countries (Luanda Agreement), The Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda, September 2002, United Nations Treaty available from https://peacemaker.un.org/drc-luandaagreement2002

[31] Virunga . (2014). Directed by Orlando von Einsiedel, Distributed by Netflix

[32] What is Good Governance?, (n.d.) United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved from: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/good-governance.pdf

[33] Zenonas T. (June, 2012) Liberal Peace and Peace-Building: Another Critique The GW Post Research Paper retrieved from www.thegwpost.com

[34] Foa R., & Mounk Y., (September 2015) Across the Globe a Growing Disillusionment with Democracy, The New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/15/opinion/across-the-globe-a-growing-disillusionment-with-democracy.html

[35] Volkan, V. D. (1997). Blood Lines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism. p. 19-30 Boulder, CO: Westview.

[36] Millar, G. (2012). ‘Our brothers who went to the bush’: Post-identity conflict and the experience of reconciliation in Sierra Leone. Journal of Peace Research , 49 (5), 717–729. doi: 10.1177/0022343312440114

[37] Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies.

The Intractable Conflict Challenge

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Roles - Part 4 -- The last in a four-part series of MPP roles looking at those who help balance power so that everyone in society is treated fairly, and those who try to defend democracy from those who would destroy it.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of May 19, 2024 -- Another in our weekly set of links from readers, our colleagues, and others with important ideas for our field.

- Crisis, Contradiction, Certainty, and Contempt -- Columbia Professor Peter Coleman, an expert on intractable conflict, reflects on the intractable conflict occurring on his own campus, suggesting "ways out" that would be better for everyone.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers

A free, open, online seminar exploring new approaches for addressing difficult and intractable conflicts. Major topic areas include:

Scale, Complexity, & Intractability

Massively Parallel Peacebuilding

Authoritarian Populism

Constructive Confrontation

Conflict Fundamentals

An look at to the fundamental building blocks of the peace and conflict field covering both “tractable” and intractable conflict.

Beyond Intractability / CRInfo Knowledge Base

Home / Browse | Essays | Search | About

BI in Context

Links to thought-provoking articles exploring the larger, societal dimension of intractability.

Colleague Activities

Information about interesting conflict and peacebuilding efforts.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Beyond Intractability or the Conflict Information Consortium.

Beyond Intractability

Unless otherwise noted on individual pages, all content is... Copyright © 2003-2022 The Beyond Intractability Project c/o the Conflict Information Consortium All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without prior written permission.

Guidelines for Using Beyond Intractability resources.

Citing Beyond Intractability resources.

Photo Credits for Homepage, Sidebars, and Landing Pages

Contact Beyond Intractability Privacy Policy The Beyond Intractability Knowledge Base Project Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess , Co-Directors and Editors c/o Conflict Information Consortium Mailing Address: Beyond Intractability, #1188, 1601 29th St. Suite 1292, Boulder CO 80301, USA Contact Form

Powered by Drupal

production_1

Introduction to the General Geography of the DRC

- First Online: 15 September 2023

Cite this chapter

- Paul Van Pul 2

55 Accesses

This chapter provides an overview of the main geographical features of the DRC, especially pertaining to its position within the neighboring countries. The typical Central African washbasin relief dictated by the Congo River watershed dominates the geography. The chapter also looks at the main regions within the borders of the DRC, unrelated to any political boundaries and lastly the principal vegetation zones, the result of the climate and their interaction with the hydrology of the Congo River watershed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

For a Canadian audience, the DRC is larger than British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan combined. For Europeans, the DRC is 76 times larger than Belgium.

Figures for the drainage basin of the river vary between 3,6 million and 4,1 million km 2 [1,390,000 & 1,583,000 sq mi] depending apparently on which areas previous authors did include or not. In comparison the Mississippi River has a basin area of almost 3 million km 2 [1,158,300 sq mi] and Western Europe’s largest basin, that of the Danube, is only 801,500 km 2 [309,460 sq mi].

The average discharge per second of the Congo River near Boma (43,000 m 3 /s or 1,518,500 cfs) is about seven times the volume that flows over Niagara Falls, both sides, every second (5796 m 3 /s or 204,680 cfs).

Under the rule of President Sese Seko Mobutu the province was called Shaba.

At Bandundu, in 1937 and 1939, the Kwango had a recorded discharge of between 5817 and 2367 m 3 /s [205,425 & 83,590 cfs].

In Congo-Brazzaville, the Ubangi River is called: Oubangui.

The cuvette centrale is the central plateau region of the DRC, having an elevation between 400 and 500 m [1300 & 1640 ft].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Paul Van Pul

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Van Pul, P. (2023). Introduction to the General Geography of the DRC. In: Hydrography and Navigation on the Congo River. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41065-9_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-41065-9_1

Published : 15 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-41064-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-41065-9

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Natural resources and conflicts

- In-depth articles

Case study Democratic Republic of the Congo - Resource wealth, poverty and conflicts

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is one of the few countries in Africa in which, even today, armed conflict is financed through the trade in minerals. Reports of UN expert groups and increased interest by the media have highlighted the DRC as a sad example of the close relationship between conflicts and the exploitation of natural resources.

The DRC is one of the most resource-rich countries in Africa. Copper, diamonds, cobalt, coltan and gold can be found in abundance. According to the German Federal Agency for Geosciences and Natural Resources (Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe), the DRC is one of the ten most important suppliers of natural resources to Germany. Despite all this, the Central African state is one of the poorest in the world. In 2015, its gross domestic product (GDP) amounted to US $35.24 billion—the German 2015 GDP, in comparison, amounted to US $ 3363.45 billion. The DRC belongs to the group of low human development (position 176 of 188) on the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) 2014, and an estimated 70 per cent of its population lived below the national poverty line in 2014.

In the 1990s, two civil wars raged in the country, and still today, the country is not at peace. It is true that in 2003 there was a peace agreement between the former warring parties, but in the east of the country, the fighting and armed raids on civilians continue.

The Congolese war economy and the role of international companies

How does the Congolese war economy work? During the first Congo war (1996 to 1997), warlords began to market natural resources. For one, rebel groups established tax systems in areas under their control. The lucrative trade in natural resources was one important pillar for this. Then, rebel groups established the control over some mining areas with their foreign military allies and forced miners to work for them.

The Congolese rebel group Rally for Democracy (Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie–RCD), allied with Rwanda, even tried to gain the monopoly over the export of metals, particularly coltan. For many years, coltan, a basic material for the electronics industry (for instance for mobile phones), has played an important role in the war economy. In Eastern Congo, there are deposits that can be mined artisanally without much technical assistance. RCD therefore founded the trading company Somigl in the year 2000, which was to have the sole right to export coltan. That year, the price of coltan rose sharply due to the boom in mobile phones and computers, and coltan became the most important source of income for rebels and militias in the east of the country. In December 2000 alone, Somigl, sold US $1.12 million worth of coltan. This boom in coltan, however, ended as quickly as it had begun, so that in 2001, Somigl was already disbanded. After that, coltan was traded via local traders and foreign buyers from the coltan processing industry, amongst them the German company H.C. Starck, a daughter of the Bayer Group.

Non-governmental organizations and a UN expert group demanded sanctions against the trade in coltan from the DRC; the Security Council, however, refrained from imposing such sanctions. One argument was that an embargo would be difficult to enforce in view of the open borders. Another argument was that sanctions imposed on coltan would mostly affect the great number of miners who would be without income. Indeed, most natural resources, such as coltan, tin, diamonds or gold are mined by hundreds of thousands of artisanal miners who work with their pure muscle power.

The discussion about sanctions has not abated. A new law in the United States has led to a de facto boycott of tin ore, coltan, tungsten and gold in the eastern provinces of South and North Kivu. It is true that the so-called Dodd -Frank-Act (see info text on 'national regulation of international business activities') does not forbid the trade in these metals from the DRC, but it forces companies to publicly report on whether they buy metals from areas of conflict. The majority of the electronics industry has since then temporarily stopped purchases from that region. To ensure legal and fair mining of resources in the DRC, the ownership of resource deposits, mining licences and the distribution of the income from this must be clarified. These questions remain open, until today.

Causes and trajectories of conflict

While the exploitation of natural resources in the DRC surely served as a motivation to continue the conflict, the root causes of wars and armed conflicts in the country were, and still are, of a political and societal nature. The DRC is an extremely poor country with more than 200 ethnic groups and a weak, corrupt state that is targeted by regional and national political interests.

With a surface area of 2,344,885 square kilometres—an area six times larger than that of Germany—the country is difficult to govern. This is aggravated by the fact that the exploitation of natural resources continued to trigger internal power struggles and external interventions. For a long time, mostly European (Belgian in particular) corporate groups had controlled natural resource extraction. This did not change much when President Mobutu, who governed the country until 1997, nationalized parts of the country's economy—then called Zairization. The autocrat misused the state-owned copper- and diamond-producing enterprises to finance his extravagant lifestyle and to pay his followers.

The neighbouring countries, too, wanted to get their hands on the rich mineral deposits. Again and again, regional powers were militarily involved in the two Congo wars (1996 to 1997 and 1998 to 2003), be it by supporting various warring parties or by direct military intervention. And this is why there were—and still are—so many weapons and ammunition in the DRC. In the second Congo war, rebel leaders from the resource-rich east, with the support of the neighbouring countries of Rwanda and Uganda, attempted a coup against the central government in Kinshasa. Other neighbouring countries, such as Angola and Zimbabwe, were supportive of the central government. They used the control over the production and the marketing of national resources to finance these activities. At the same time, individuals in armies and the state apparatus got rich.

The first Congo war must also be viewed against the backdrop of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. There, the extremist Hutu government had up to one million Tutsi and Hutu from the opposition murdered. When Tutsi rebels stopped the genocide, more than one million Hutu fled to the DRC (the Zaire); amongst them were also members of the so-called Interahamwe, a Hutu paramilitary organization that had participated in the genocide. The new Rwandan government felt threatened by the extremist Hutu in the refugee camps across the border and justified its invasion into the DRC in 1996 with this. The presence of the Rwandan Hutu in the east of the DRC exacerbated conflicts between Congolese Hutu and Tutsi (North Kivu) and long-established ethnic groups such as the Wabembe and recently arrived groups, such as the Banyamulenge (South Kivu). The numerous armed groups, be they Congolese or foreign, that had participated in the wars have also contributed to the fact that the chasm between ethnic groups became even deeper.

Only in July 2003 did the United Nations impose sanctions on the import of weapons and ammunition that, initially, were limited to regions in the east of the DRC. Today, a large part of the armed groups have either been integrated into the armed forces or have been disarmed—one consequence of military operations by Congolese and Rwandan military and UN peacekeeping forces. The Rwandan Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR - Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda), founded by the former Interahamwe and some Congolese militias, still exists, plunder villages and control some trade routes. Despite various agreements and the largest peacekeeping operation of all times (MONUC, then MONUSCO, with at times more than 20,000 soldiers), the fighting has still not totally stopped.

For the current conflict, too, natural resources, their exploitation and their trade play an important role. FDLR, militias and the army continue to control large parts of the mining areas. Just like rebels and militias, parts of the state army impose protection duties and possess shares in mines.

Sources and further information:

- medico international - Hintergrund zum Rohstoffkonflikt in der DR Kongo

- Medica Mondiale in der DR Kongo

- ÖNZ und Forum Menschenrechte (Hsg.) 2007. Von der Gewalt zur Kriegsökonomie. Deutsche Unternehmen in der Demokratischen Republik Kongo (German)

© picture-alliance/dpa

Data tables

For some select map layers, the information portal ‘War and Peace’ provides the user with all used data sets as tables.

Country portraits

In the country reports, data and information are collected by country and put into tables that are used in the modules as a basis for maps and illustrations.

Navigation and operation

The information and data of each module are primarily made available as selectable map layers and are complemented by texts and graphs. The map layers can be found on the right hand side and are listed according to themes and sub-themes.

- International

- Education Jobs

- Schools directory

- Resources Education Jobs Schools directory News Search

DRC Development Case Study - OCR B Geography

Subject: Geography

Age range: 14-16

Resource type: Unit of work

Last updated

8 November 2021

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

Five lessons based on the Democratic Republic of Congo planned on the topic Dynamic Development following the OCR B Geography specification.

Lesson Six - Intro to the Democratic Republic of Congo Lesson Seven - Ros-tow Model Lesson Eight - Millennium Development Goals Lesson Nine - Trade and Transnational Corporations Lesson Ten - Aid in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

This site requires Javascript to be turned on. Please enable Javascript and reload the page.

This page is referenced by:

“OOSCI (2013) surveyed households in DRC on reasons for non-enrolment and drop-out for 6–17 year olds, with one option being “fear of crime and conflict”. Whilst this was not the main reason in any province, it was significant in the two worst-affected provinces, North and South Kivu, with “fear of crime and conflict” being the primary reason for drop-out for 16% in South Kivu and 8% in North Kivu compared to 4% nationally, and the primary reason for non-enrolment for 10% in South Kivu and 15% in North Kivu compared to 5% nationally.” –The quantitative impact of armed conflict on education in DRC: case study, 2014

The DRC: Comparison with the UK

Comparing the drc with the uk.

We can use development indicators to compare the quality of life of those who live in DRC with those who live in the UK.

Development indicators

- DRC: $800 (USD).

- UK: $44,300.

- DRC: 61 years.

- UK: 81.1 years.

Development indicators cont.

- DRC: 55.2%.

- DRC: 0.457.

- Primary: 19.7%.

- Secondary: 43.6%.

- Tertiary: 36.7%.

- Primary: 0.7%.

- Secondary: 20.2%.

- Tertiary: 32.5%.

1 Geography Skills

1.1 Mapping

1.1.1 Map Making

1.1.2 OS Maps

1.1.3 Grid References

1.1.4 Contour Lines

1.1.5 Symbols, Scale and Distance

1.1.6 Directions on Maps

1.1.7 Describing Routes

1.1.8 Map Projections

1.1.9 Aerial & Satellite Images

1.1.10 Using Maps to Make Decisions

1.2 Geographical Information Systems

1.2.1 Geographical Information Systems

1.2.2 How do Geographical Information Systems Work?

1.2.3 Using Geographical Information Systems

1.2.4 End of Topic Test - Geography Skills

2 Geology of the UK

2.1 The UK's Rocks

2.1.1 The UK's Main Rock Types

2.1.2 The UK's Landscape

2.1.3 Using Rocks

2.1.4 Weathering

2.2 Case Study: The Peak District

2.2.1 The Peak District

2.2.2 Limestone Landforms

2.2.3 Quarrying

3 Geography of the World

3.1 Geography of America & Europe

3.1.1 North America

3.1.2 South America

3.1.3 Europe

3.1.4 The European Union

3.1.5 The Continents

3.1.6 The Oceans

3.1.7 Longitude

3.1.8 Latitude

3.1.9 End of Topic Test - Geography of the World

4 Development

4.1 Development

4.1.1 Classifying Development

4.1.3 Evaluation of GDP

4.1.4 The Human Development Index

4.1.5 Population Structure

4.1.6 Developing Countries

4.1.7 Emerging Countries

4.1.8 Developed Countries

4.1.9 Comparing Development

4.2 Uneven Development

4.2.1 Consequences of Uneven Development

4.2.2 Physical Factors Affecting Development

4.2.3 Historic Factors Affecting Development

4.2.4 Human & Social Factors Affecting Development

4.2.5 Breaking Out of the Poverty Cycle

4.3 Case Study: Democratic Republic of Congo

4.3.1 The DRC: An Overview

4.3.2 Political & Social Factors Affecting Development

4.3.3 Environmental Factors Affecting the DRC

4.3.4 The DRC: Aid

4.3.5 The Pros & Cons of Aid in DRC

4.3.6 Top-Down vs Bottom-Up in DRC

4.3.7 The DRC: Comparison with the UK

4.3.8 The DRC: Against Malaria Foundation

4.4 Case Study: Nigeria

4.4.1 The Importance & Development of Nigeria

4.4.2 Nigeria's Relationships with the Rest of the World

4.4.3 Urban Growth in Lagos

4.4.4 Population Growth in Lagos

4.4.5 Factors influencing Nigeria's Growth

4.4.6 Nigeria: Comparison with the UK

5 Weather & Climate

5.1 Weather

5.1.1 Weather & Climate

5.1.2 Components of Weather

5.1.3 Temperature

5.1.4 Sunshine, Humidity & Air Pressure

5.1.5 Cloud Cover

5.1.6 Precipitation

5.1.7 Convectional Precipitation

5.1.8 Frontal Precipitation

5.1.9 Relief or Orographic Precipitation

5.1.10 Wind

5.1.11 Extreme Wind

5.1.12 Recording the Weather

5.1.13 Extreme Weather

5.2 Climate

5.2.1 Climate of the British Isles

5.2.2 Comparing Weather & Climate London

5.2.3 Climate of the Tropical Rainforest

5.2.4 End of Topic Test - Weather & Climate

5.3 Tropical Storms

5.3.1 Formation of Tropical Storms

5.3.2 Features of Tropical Storms

5.3.3 The Structure of Tropical Storms

5.3.4 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina Effects

5.3.5 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina Responses

6 The World of Work

6.1 Tourism

6.1.1 Landscapes

6.1.2 The Growth of Tourism

6.1.3 Benefits of Tourism

6.1.4 Economic Costs of Tourism

6.1.5 Social, Cultural & Environmental Costs of Tourism

6.1.6 Tourism Case Study: Blackpool

6.1.7 Ecotourism

6.1.8 Tourism Case Study: Kenya

7 Natural Resources

7.1.1 What are Rocks?

7.1.2 Types of Rock

7.1.4 The Rock Cycle - Weathering

7.1.5 The Rock Cycle - Erosion

7.1.6 What is Soil?

7.1.7 Soil Profiles

7.1.8 Water

7.1.9 Global Water Demand

7.2 Fossil Fuels

7.2.1 Introduction to Fossil Fuels

7.2.2 Fossil Fuels

7.2.3 The Global Energy Supply

7.2.5 What is Peak Oil?

7.2.6 End of Topic Test - Natural Resources

8.1 River Processes & Landforms

8.1.1 Overview of Rivers

8.1.2 The Bradshaw Model

8.1.3 Erosion

8.1.4 Sediment Transport

8.1.5 River Deposition

8.1.6 River Profiles: Long Profiles

8.1.7 River Profiles: Cross Profiles

8.1.8 Waterfalls & Gorges

8.1.9 Interlocking Spurs

8.1.10 Meanders

8.1.11 Floodplains

8.1.12 Levees

8.1.13 Case Study: River Tees

8.2 Rivers & Flooding

8.2.1 Flood Risk Factors

8.2.2 Flood Management: Hard Engineering

8.2.3 Flood Management: Soft Engineering

8.2.4 Flooding Case Study: Boscastle

8.2.5 Flooding Case Study: Consequences of Boscastle

8.2.6 Flooding Case Study: Responses to Boscastle

8.2.7 Flooding Case Study: Bangladesh

8.2.8 End of Topic Test - Rivers

8.2.9 Rivers Case Study: The Nile

8.2.10 Rivers Case Study: The Mississippi

9.1 Formation of Coastal Landforms

9.1.1 Weathering

9.1.2 Erosion

9.1.3 Headlands & Bays

9.1.4 Caves, Arches & Stacks

9.1.5 Wave-Cut Platforms & Cliffs

9.1.6 Waves

9.1.7 Longshore Drift

9.1.8 Coastal Deposition

9.1.9 Spits, Bars & Sand Dunes

9.2 Coast Management

9.2.1 Management Strategies for Coastal Erosion

9.2.2 Case Study: The Holderness Coast

9.2.3 Case Study: Lyme Regis

9.2.4 End of Topic Test - Coasts

10 Glaciers

10.1 Overview of Glaciers & How They Work

10.1.1 Distribution of Glaciers

10.1.2 Types of Glaciers

10.1.3 The Last Ice Age

10.1.4 Formation & Movement of Glaciers

10.1.5 Shaping of Landscapes by Glaciers

10.1.6 Glacial Landforms Created by Erosion

10.1.7 Glacial Till & Outwash Plain

10.1.8 Moraines

10.1.9 Drumlins & Erratics

10.1.10 End of Topic Tests - Glaciers

10.1.11 Tourism in Glacial Landscapes

10.1.12 Strategies for Coping with Tourists

10.1.13 Case Study - Lake District: Tourism

10.1.14 Case Study - Lake District: Management

11 Tectonics

11.1 Continental Drift & Plate Tectonics

11.1.1 The Theory of Plate Tectonics

11.1.2 The Structure of the Earth

11.1.3 Tectonic Plates

11.1.4 Plate Margins

11.2 Volcanoes

11.2.1 Volcanoes & Their Products

11.2.2 The Development of Volcanoes

11.2.3 Living Near Volcanoes

11.3 Earthquakes

11.3.1 Overview of Earthquakes

11.3.2 Consequences of Earthquakes

11.3.3 Case Study: Christchurch, New Zealand Earthquake

11.4 Tsunamis

11.4.1 Formation of Tsunamis

11.4.2 Case Study: Japan 2010 Tsunami

11.5 Managing the Risk of Volcanoes & Earthquakes

11.5.1 Coping With Earthquakes & Volcanoes

11.5.2 End of Topic Test - Tectonics

12 Climate Change

12.1 The Causes & Consequences of Climate Change

12.1.1 Evidence for Climate Change

12.1.2 Natural Causes of Climate Change