Article Review Generator

Here is your article critique :

Writing an article review can become a daunting task for any student. It requires analyzing the article's content, evaluating it, and sharing personal insights. Stuck with summarizing the article rather than criticizing it? Use this article review generator!

- ️🎤 What Is This Review Generator?

- ️👑 Article Review Generator Benefits

- ️🤔 When to Use the Tool

- ️✍️ How to Write an Article Review

- ️❓ Article Review Generator Free: FAQ

- ️🔗 References

🎤 What Is the Article Review Generator?

Our online article review generator is an excellent solution for crafting comprehensive reviews. It offers in-depth analysis while ensuring that the main ideas from the article are effectively highlighted. The tool allows students to focus on critical evaluation and personal insights rather than getting bogged down in summarization.

An article review is a piece that critically evaluates and analyzes a scholarly article or research paper. It involves summarizing the article's main points, assessing its strengths and weaknesses, and providing personal opinion.

You may need to write an article analysis:

- To provide a critique of a specific article or paper.

- To contribute to academic discourse by evaluating scholarly work.

- To improve your writing skills via summarizing, analyzing, and critiquing complex texts.

- To deepen understanding of a topic.

- To prepare for future research projects.

👑 Online Article Review Generator: 6 Benefits

Many benefits make our article review summary generator stand out. For example, it is:

| 🦾 AI-based | Our article review generator is powered by artificial intelligence, ensuring it can analyze articles accurately without missing key points or details. |

|---|---|

| 🤲 Free | In a time when many online tools require payment or subscriptions, our tool is completely free to use. |

| 🔮 Unlimited | Users can regenerate the review multiple times until they are fully satisfied with the output. |

| 🔝 High quality | The output provided by the tool matches all academic standards. You will get an objective and reliable article analysis. |

| 💨 Fast & time-saving | With our tool, any user can create an article review in a few simple clicks, saving valuable time for other tasks. |

| 🪐 Universal | The generator is designed to work with various articles across different topics and disciplines. |

🤔 When to Use the Article Reviewer Tool?

Our tool is not only helpful in writing article reviews, but it also comes in handy for a variety of other purposes. Here are some cases when you can use the article review summary generator:

- Analyze the article's strengths and weaknesses.

- Quickly understand the key points and arguments of the article.

- Get a new perspective on the article's content and structure.

- Generate a concise summary of an article.

- Understand complex articles more effectively.

- Improve writing skills .

- Be informed about current developments.

- Prepare for exams or presentations.

- Facilitate collaboration during group projects.

- Get multiple article summaries for the literature review.

✍️ How to Write an Article Review

You can always use our online article review generator to analyze and critique an article quickly. However, if you have time and wish to enhance your academic writing skills, consider writing the review yourself. To help you with this, we've prepared a step-by-step tutorial for crafting a compelling article review .

Step 1 – Preparation

First of all, you should clearly understand the goal of this assignment. An article review is more than just a summary or your opinion on a publication. It involves a critical analysis and assessment of the content.

Here's what to do to prepare for composing an article review:

- Assess the title. Before delving into the paper, consider what the title suggests about its content and the potential focus of the author's argument.

- Analyze the structure. Subheadings can offer a roadmap of the article's organization. Focus on them to get an overview of the key topics the author will explore.

- Understand the main idea. Identify the article's central argument or thesis. It is the primary claim or position the author is asserting.

- Analyze the abstract. An abstract is a condensed version of the article. It offers a glimpse into the main arguments, research methodology, and conclusions.

Step 2 – Reading

Carefully reading an article is vital for making a well-informed evaluation , so don't underestimate this stage. Take notes or use highlighters to keep track of the information you might refer to later. We suggest paying attention to:

- Intended audience. Determine who the article is addressing. Consider potential readers' level of expertise, interests, and background knowledge.

- Author's purpose. Does the writer aim to summarize extant research, put forward a fresh argument, or refute others' claims?

- Key terms. Note whether the author defines key concepts. A straightforward definition of terminology helps understand the writer's arguments better.

- Facts and opinions. Differentiate between objective information and the author's views. Assess the adequacy and reliability of the presented information.

- Central arguments and conclusions. Evaluate their clarity, coherence, and the degree to which they are reinforced by evidence and analysis.

- Methodology and findings. Examine the methods and expected results in the article. Assess the research credibility and the clarity of the reported findings.

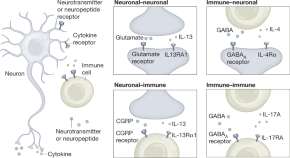

- Visual aids. If the article contains illustrations or charts, analyze their effectiveness in communicating information and strengthening the message.

Step 3 – Outlining & Drafting

Outlining an article review can help you arrange your ideas and guarantee that your paper is logical and coherent. Usually, an outline comprises an introduction, the body of the review, and a conclusion.

When outlining, work on your thesis statement . It is a sentence or two that presents your main argument about the article, which you will support and develop in your review.

After finishing your outline, you can move on to writing a draft. These are the main components for each section of an article review:

- Hook (attention-grabbing opening).

- Background information on the article.

- Thesis statement.

- Summary of the article.

- Analysis and evaluation.

- Restated thesis statement.

- Summary of your main points.

- Final evaluation of the article.

- Suggestions for further research or areas for improvement.

Step 4 – Writing

The final stage of writing an article critique involves reviewing and polishing the draft. It is important to revise the piece and check for any mistakes or inconsistencies. Additionally, we recommend double-checking all citations and references and ensuring they are carefully formatted according to the requirements provided in the assignment.

During the review and polishing process, consider the following:

- Review title. Consider creating a suitable title for the article review if a title is not provided. A good article review title should convey the text's main focus, include keywords, and hint at what readers can expect from the review.

- Reference list. Include a reference list to acknowledge and give credit to the sources you have used in your review. Even if the review only references the article being analyzed, the reference list should include this article.

❓ Article Review Generator Free: FAQ

❓ what is an article review.

An article review critically evaluates and analyzes a scholarly article or research paper. It summarizes the main points, critiques the methodology, and discusses the significance and potential limitations of the work. Article reviews are a common assignment among high school and college students.

❓ How to write an article review?

Writing an article review starts with thorough preparation and understanding of the article's context. Then, carefully read the article to identify critical points and evaluate the author's arguments. Finally, provide a well-reasoned and supported assessment of the article's overall quality and contribution. You can always use our article review generator for the best summary and evaluation.

❓ Where is the literature review in an article?

The literature review in an article is typically situated after the introduction or in the body section. It draws a comprehensive overview of existing research relevant to the article's topic. However, not all article reviews require a literature review. It's better to consult the professor or review guidelines to determine if a literature review is necessary for the specific assignment.

❓ How to start an article review?

To begin an article review, start by introducing the article's title, author, and publication date. Provide a brief overview of the article's main topic and purpose. Consider setting the context by explaining the topic's significance and the article's relevance to the field. Lastly, state your thesis or main argument regarding the article's quality and contribution.

Updated: Jun 6th, 2024

🔗 References

- How to Write an Article Review (with Sample Reviews) - wikiHow

- Research Guides: Introduction to Research: Humanities and Social Sciences: Critical Reviews

- How to Review a Journal Article | University of Illinois Springfield

- Research Guides: Writing Help: The Article Review

RAxter is now Enago Read! Enjoy the same licensing and pricing with enhanced capabilities. No action required for existing customers.

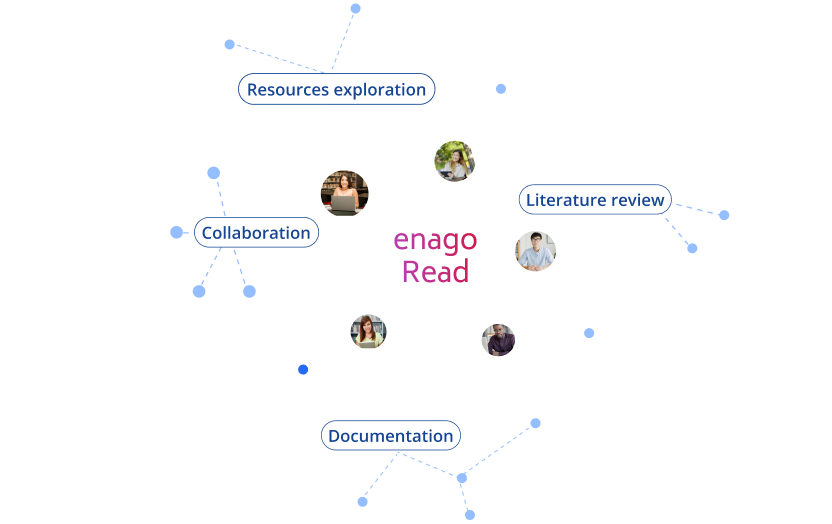

Your all in one AI-powered Reading Assistant

A Reading Space to Ideate, Create Knowledge, and Collaborate on Your Research

- Smartly organize your research

- Receive recommendations that cannot be ignored

- Collaborate with your team to read, discuss, and share knowledge

From Surface-Level Exploration to Critical Reading - All in one Place!

Fine-tune your literature search.

Our AI-powered reading assistant saves time spent on the exploration of relevant resources and allows you to focus more on reading.

Select phrases or specific sections and explore more research papers related to the core aspects of your selections. Pin the useful ones for future references.

Our platform brings you the latest research related to your and project work.

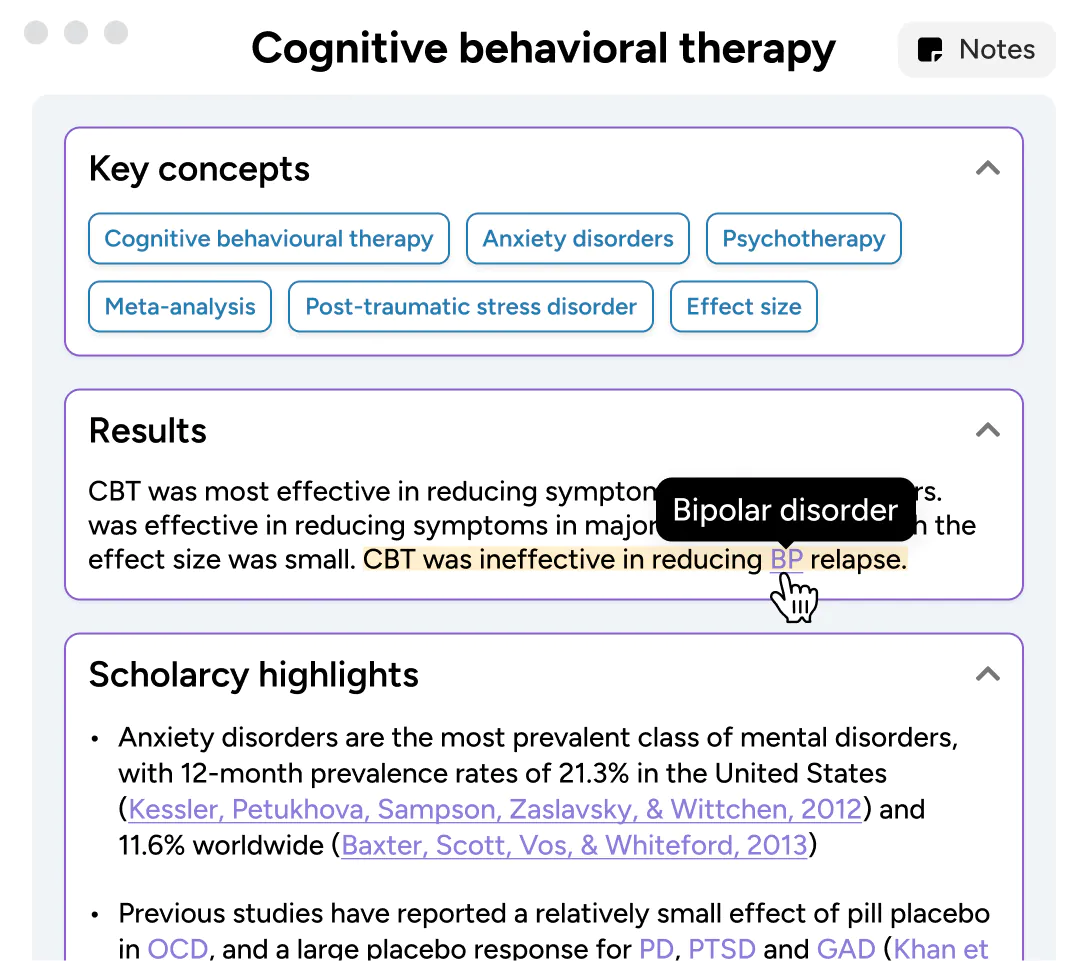

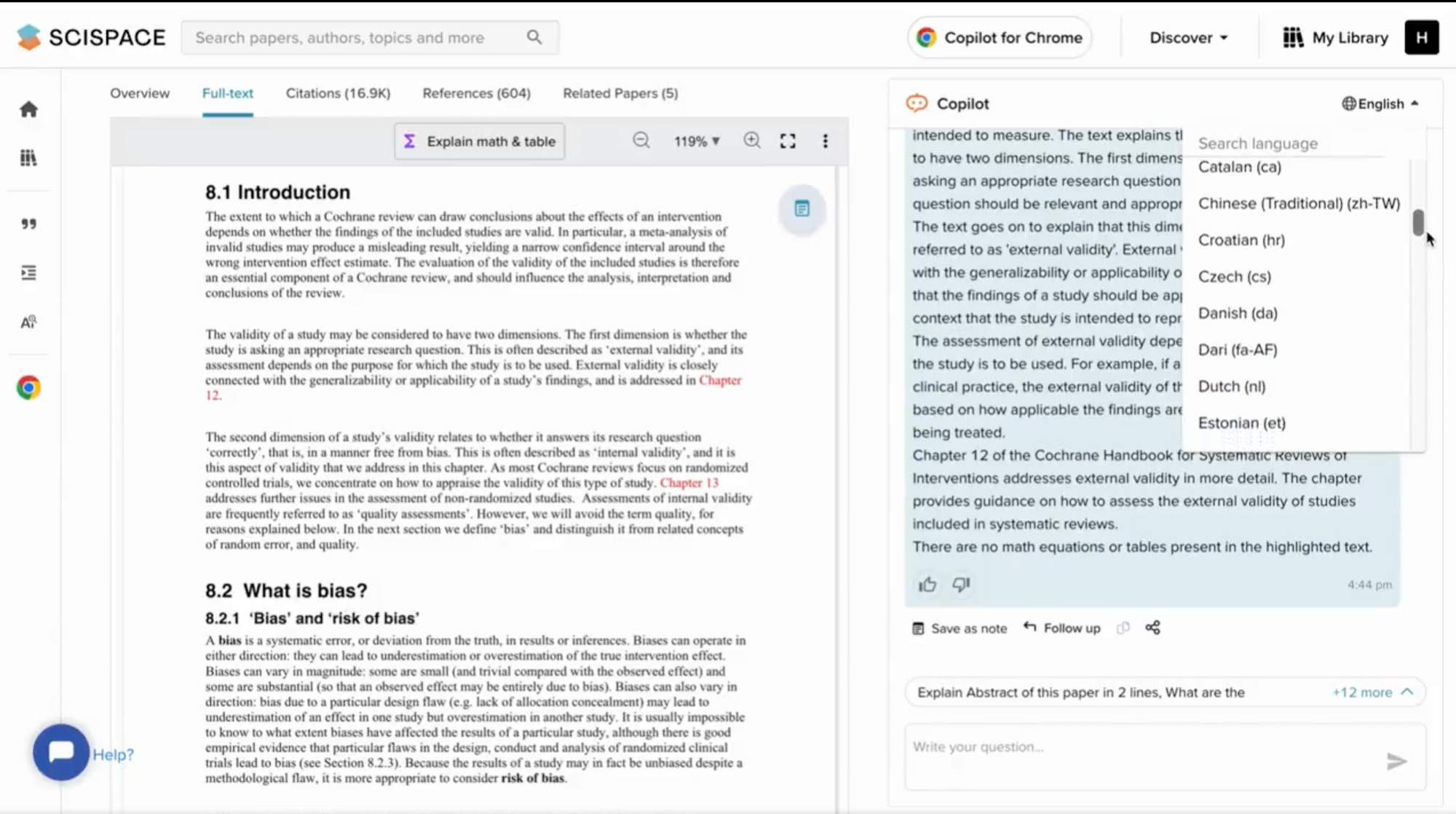

Speed up your literature review

Quickly generate a summary of key sections of any paper with our summarizer.

Make informed decisions about which papers are relevant, and where to invest your time in further reading.

Get key insights from the paper, quickly comprehend the paper’s unique approach, and recall the key points.

Bring order to your research projects

Organize your reading lists into different projects and maintain the context of your research.

Quickly sort items into collections and tag or filter them according to keywords and color codes.

Experience the power of sharing by finding all the shared literature at one place.

Decode papers effortlessly for faster comprehension

Highlight what is important so that you can retrieve it faster next time.

Select any text in the paper and ask Copilot to explain it to help you get a deeper understanding.

Ask questions and follow-ups from AI-powered Copilot.

Collaborate to read with your team, professors, or students

Share and discuss literature and drafts with your study group, colleagues, experts, and advisors. Recommend valuable resources and help each other for better understanding.

Work in shared projects efficiently and improve visibility within your study group or lab members.

Keep track of your team's progress by being constantly connected and engaging in active knowledge transfer by requesting full access to relevant papers and drafts.

Find papers from across the world's largest repositories

Testimonials

Privacy and security of your research data are integral to our mission..

Everything you add or create on Enago Read is private by default. It is visible if and when you share it with other users.

You can put Creative Commons license on original drafts to protect your IP. For shared files, Enago Read always maintains a copy in case of deletion by collaborators or revoked access.

We use state-of-the-art security protocols and algorithms including MD5 Encryption, SSL, and HTTPS to secure your data.

Join over 500,000 people saving time

Summarize, analyze and organize your research

Summarize anything

Understand complex research

Organize your knowledge

AI powered tools built specifically for academic papers

From undergrad to postgrad and beyond.

Researchers

“It would normally take me 15mins – 1 hour to skim read the article but with Scholarcy I can do that in 5 minutes.”

Omar Ng , Masters student @omarng

It’s time to revolutionize your research workflow

So, you have texts coming at you from every angle and need to articulate your understanding of them tomorrow? We’ve been there…

Summarize any paper, article or textbook.

You can summarize videos too! Scholarcy converts long complex texts into interactive summary flashcards, which highlight key information.

We’re compatible!

Import any file, from anywhere. Whether you're browsing articles online, have a chapter downloaded, or a folder of PDFs and Word docs.

Enhance your summaries

Change the summary to match your reading style with our Enhance feature. Choose from a single sentence to a researcher level overview.

Jump to key findings with Spotlight

We’ll take you straight to the important points, key concepts, and contributions.

Critically evaluate complex texts more easily

Smart highlighting and analyzing features guide you to important sections of text and help you interpret them.

Find order from chaos

Our Flashcards provide a structured, consistent format to read and explore any text from, whether you’re reading just one article or 20.

Highlight, annotate and take notes

Never lose another flash of inspiration. Add notes while you read and pick up right where you left off.

Explore new concepts and terms as you go

We’ll point you to further reading and show you how the article compares to earlier work.

Keep track of your knowledge

Never lose another text. Scholarcy is the perfect tool for saving, organising and getting a quick refresher of your reading.

Save summaries and never lose another paper

Generate and save flashcards to your library even while browsing and reading on the go.

Keep track of important details

Store all of your references, figures and tables and easily find them again.

Refresh your memory

Quickly remind yourself of the key facts and findings before a lecture or meeting with your supervisor.

Synthesize your insights. Export to other apps.

Export your flashcards to a range of file formats that are compatible with lots of research and productivity apps.

Export summaries to a range of formats

Learn more about your texts and how they compare, or connect by exporting to Excel, PKMS and more.

Import directly from Zotero

Convert your Zotero library into Scholarcy Flashcards for more efficient article screening.

Generate bibliographies in a click

Export your flashcards to your favourite citation manager or generate a one-click, fully formatted bibliography in Word.

Apply what you’ve learned. Write that magnum opus 🤌

Transform all that knowledge you’ve built up into a perfectly articulated argument.

Introduction

Try Scholarcy today

Your all in one AI-powered Reading Assistant

A Reading Space to Ideate, Create Knowledge, & Collaborate on Your Research

- Smartly organize your research

- Receive recommendations that can not be ignored

- Collaborate with your team to read, discuss, and share knowledge

From Surface-Level Exploration to Critical Reading - All at One Place!

Fine-tune your literature search.

Our AI-powered reading assistant saves time spent on the exploration of relevant resources and allows you to focus more on reading.

Select phrases or specific sections and explore more research papers related to the core aspects of your selections. Pin the useful ones for future references.

Our platform brings you the latest research news, online courses, and articles from magazines/blogs related to your research interests and project work.

Speed up your literature review

Quickly generate a summary of key sections of any paper with our summarizer.

Make informed decisions about which papers are relevant, and where to invest your time in further reading.

Get key insights from the paper, quickly comprehend the paper’s unique approach, and recall the key points.

Bring order to your research projects

Organize your reading lists into different projects and maintain the context of your research.

Quickly sort items into collections and tag or filter them according to keywords and color codes.

Experience the power of sharing by finding all the shared literature at one place

Decode papers effortlessly for faster comprehension

Highlight what is important so that you can retrieve it faster next time

Find Wikipedia explanations for any selected word or phrase

Save time in finding similar ideas across your projects

Collaborate to read with your team, professors, or students

Share and discuss literature and drafts with your study group, colleagues, experts, and advisors. Recommend valuable resources and help each other for better understanding.

Work in shared projects efficiently and improve visibility within your study group or lab members.

Keep track of your team's progress by being constantly connected and engaging in active knowledge transfer by requesting full access to relevant papers and drafts.

Find Papers From Across the World's Largest Repositories

Testimonials

Privacy and security of your research data are integral to our mission..

Everything you add or create on Enago Read is private by default. It is visible only if and when you share it with other users.

You can put Creative Commons license on original drafts to protect your IP. For shared files, Enago Read always maintains a copy in case of deletion by collaborators or revoked access.

We use state-of-the-art security protocols and algorithms including MD5 Encryption, SSL, and HTTPS to secure your data.

🤖 AI Literature Review Generator

Unleash the power of AI with our Literature Review Generator. Effortlessly access comprehensive and meticulously curated literature reviews to elevate your research like never before!

The landscape of knowledge is vast, diverse, and ever-changing. Navigating it can seem daunting yet exciting, like reading a suspense-filled novel. Welcome to the world of a literature review, a fundamental tool that manages complexity, uncovers answers, and expands understanding in any research venture. A literature review generator simplifies this process and makes it more accessible.

Explore the review of existing literature, moving from the general to the specific, the known to the unknown. A literature review bridges the gap between raw data and informed conclusions. It defines research objectives, highlights key themes of the content, identifies gaps, and outlines future study areas.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a comprehensive analysis and evaluation of scholarly articles, books, and other sources concerning a particular field of study or a research question. This process involves discussing the state of the art of an area of research and identifying pivotal works and researchers in the domain.

The primary purpose of a literature review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the knowledge that already exists on your chosen subject.

This type of review usually serves as the starting point for many forms of academic research and forms a vital part of dissertations, thesis, research articles, and other documents. Its significance lies in its ability to concentrate the existing knowledge on a subject and reveal gaps that need further research.

A well-crafted literature review also clarifies the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates, and establishes a framework for interpreting the findings of your study in the context of what is already known.

Why Use a Literature Review Generator?

Universities and academic institutions require students to develop literature reviews — these targeted examinations of other studies related to your current research provide a robust foundation for your work.

While these are satisfactory to develop your academic writing skills, they can be time-consuming and challenging due to the extensive research involved. With the contemporary integration of technological tools into our daily lives, literature review generators have become a lifeline for many students.

Now, let’s take a closer look at why you should embrace these generators in the literature review process, and explore the benefits that they pose.

- Ease of Information Gathering : Comprehensive studies require extensive reading and diligent research, which often takes hours to complete. Literature review generators automate the information-gathering process, retrieving relevant articles, journals, and related publications in a matter of seconds. This ensures a momentous saving of time and relieves the user from the tedious job of slogging through numerous resources.

- Coherent and Well-Structured Reviews : Structuring the review in a logical and coherent manner can be a difficult task. These intelligent tools present well-structured reviews, offering well-organized input which can guide you in writing your own well-formulated literature review.

- Finds Good Matches : A literature review generator is designed to find the most relevant literature content according to your research topic. The expertise of these software tools allows users to ease the process of finding relevant scholarly articles and other documents, making it more accurate and faster than doing it manually.

- Reduces Errors and Improves Quality : Humans are prone to making mistakes, especially when tasked with analyzing extensive volumes of data. Literature review generators minimize errors by ensuring access to the most accurate data and providing proper citations hence enhancing the quality of the review.

- Pedagogical Benefits : Using a Literature review generator does not only provide a quick fix for students but it also serves as a tool for learning. It allows the users to understand how professional literature reviews should be structured and can guide them in crafting their work.

How To Use This AI Generator:

- Click “Use Generator” to create a project instantly in your workspace.

- Click “Save Generator” to create a reusable template for you and your team.

- Customize your project , make it your own, and get work done!

The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

A Career Coach Reviewed The 10-Year-Old Résumé That Got Him Into Google. He Would Make 3 Changes Today

Developer successfully boots up linux on google drive, paramount global merges with skydance, creating ‘new paramount’, what does a world without airbnb look like, house of the dragon recap: you win or you die, house of the dragon scorecard: crown roast, ecuador court rules pollution violates rights of a river running through capital, show hn: simulating 20m particles in javascript, daemon’s harrenhal visions in ‘house of the dragon’ season 2, episode 4, explained, house of the dragon’ season 2, episode 4: who is alyn, and why might he be important, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

4 Ways to Report Fraud on Craigslist

How to Stop Dogs Licking You: 11 Steps

3 Ways to Buy Clothes That Fit

How to Feed a Diabetic Cat: 13 Steps

How to Dance the Boogie Woogie: 15 Steps

11 Easy Ways to Say “Stupid” in Spanish

How to Review a Journal Article

For many kinds of assignments, like a literature review , you may be asked to offer a critique or review of a journal article. This is an opportunity for you as a scholar to offer your qualified opinion and evaluation of how another scholar has composed their article, argument, and research. That means you will be expected to go beyond a simple summary of the article and evaluate it on a deeper level. As a college student, this might sound intimidating. However, as you engage with the research process, you are becoming immersed in a particular topic, and your insights about the way that topic is presented are valuable and can contribute to the overall conversation surrounding your topic.

IMPORTANT NOTE!!

Some disciplines, like Criminal Justice, may only want you to summarize the article without including your opinion or evaluation. If your assignment is to summarize the article only, please see our literature review handout.

Before getting started on the critique, it is important to review the article thoroughly and critically. To do this, we recommend take notes, annotating , and reading the article several times before critiquing. As you read, be sure to note important items like the thesis, purpose, research questions, hypotheses, methods, evidence, key findings, major conclusions, tone, and publication information. Depending on your writing context, some of these items may not be applicable.

Questions to Consider

To evaluate a source, consider some of the following questions. They are broken down into different categories, but answering these questions will help you consider what areas to examine. With each category, we recommend identifying the strengths and weaknesses in each since that is a critical part of evaluation.

Evaluating Purpose and Argument

- How well is the purpose made clear in the introduction through background/context and thesis?

- How well does the abstract represent and summarize the article’s major points and argument?

- How well does the objective of the experiment or of the observation fill a need for the field?

- How well is the argument/purpose articulated and discussed throughout the body of the text?

- How well does the discussion maintain cohesion?

Evaluating the Presentation/Organization of Information

- How appropriate and clear is the title of the article?

- Where could the author have benefited from expanding, condensing, or omitting ideas?

- How clear are the author’s statements? Challenge ambiguous statements.

- What underlying assumptions does the author have, and how does this affect the credibility or clarity of their article?

- How objective is the author in his or her discussion of the topic?

- How well does the organization fit the article’s purpose and articulate key goals?

Evaluating Methods

- How appropriate are the study design and methods for the purposes of the study?

- How detailed are the methods being described? Is the author leaving out important steps or considerations?

- Have the procedures been presented in enough detail to enable the reader to duplicate them?

Evaluating Data

- Scan and spot-check calculations. Are the statistical methods appropriate?

- Do you find any content repeated or duplicated?

- How many errors of fact and interpretation does the author include? (You can check on this by looking up the references the author cites).

- What pertinent literature has the author cited, and have they used this literature appropriately?

Following, we have an example of a summary and an evaluation of a research article. Note that in most literature review contexts, the summary and evaluation would be much shorter. This extended example shows the different ways a student can critique and write about an article.

Chik, A. (2012). Digital gameplay for autonomous foreign language learning: Gamers’ and language teachers’ perspectives. In H. Reinders (ed.), Digital games in language learning and teaching (pp. 95-114). Eastbourne, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Be sure to include the full citation either in a reference page or near your evaluation if writing an annotated bibliography .

In Chik’s article “Digital Gameplay for Autonomous Foreign Language Learning: Gamers’ and Teachers’ Perspectives”, she explores the ways in which “digital gamers manage gaming and gaming-related activities to assume autonomy in their foreign language learning,” (96) which is presented in contrast to how teachers view the “pedagogical potential” of gaming. The research was described as an “umbrella project” consisting of two parts. The first part examined 34 language teachers’ perspectives who had limited experience with gaming (only five stated they played games regularly) (99). Their data was recorded through a survey, class discussion, and a seven-day gaming trial done by six teachers who recorded their reflections through personal blog posts. The second part explored undergraduate gaming habits of ten Hong Kong students who were regular gamers. Their habits were recorded through language learning histories, videotaped gaming sessions, blog entries of gaming practices, group discussion sessions, stimulated recall sessions on gaming videos, interviews with other gamers, and posts from online discussion forums. The research shows that while students recognize the educational potential of games and have seen benefits of it in their lives, the instructors overall do not see the positive impacts of gaming on foreign language learning.

The summary includes the article’s purpose, methods, results, discussion, and citations when necessary.

This article did a good job representing the undergraduate gamers’ voices through extended quotes and stories. Particularly for the data collection of the undergraduate gamers, there were many opportunities for an in-depth examination of their gaming practices and histories. However, the representation of the teachers in this study was very uneven when compared to the students. Not only were teachers labeled as numbers while the students picked out their own pseudonyms, but also when viewing the data collection, the undergraduate students were more closely examined in comparison to the teachers in the study. While the students have fifteen extended quotes describing their experiences in their research section, the teachers only have two of these instances in their section, which shows just how imbalanced the study is when presenting instructor voices.

Some research methods, like the recorded gaming sessions, were only used with students whereas teachers were only asked to blog about their gaming experiences. This creates a richer narrative for the students while also failing to give instructors the chance to have more nuanced perspectives. This lack of nuance also stems from the emphasis of the non-gamer teachers over the gamer teachers. The non-gamer teachers’ perspectives provide a stark contrast to the undergraduate gamer experiences and fits neatly with the narrative of teachers not valuing gaming as an educational tool. However, the study mentioned five teachers that were regular gamers whose perspectives are left to a short section at the end of the presentation of the teachers’ results. This was an opportunity to give the teacher group a more complex story, and the opportunity was entirely missed.

Additionally, the context of this study was not entirely clear. The instructors were recruited through a master’s level course, but the content of the course and the institution’s background is not discussed. Understanding this context helps us understand the course’s purpose(s) and how those purposes may have influenced the ways in which these teachers interpreted and saw games. It was also unclear how Chik was connected to this masters’ class and to the students. Why these particular teachers and students were recruited was not explicitly defined and also has the potential to skew results in a particular direction.

Overall, I was inclined to agree with the idea that students can benefit from language acquisition through gaming while instructors may not see the instructional value, but I believe the way the research was conducted and portrayed in this article made it very difficult to support Chik’s specific findings.

Some professors like you to begin an evaluation with something positive but isn’t always necessary.

The evaluation is clearly organized and uses transitional phrases when moving to a new topic.

This evaluation includes a summative statement that gives the overall impression of the article at the end, but this can also be placed at the beginning of the evaluation.

This evaluation mainly discusses the representation of data and methods. However, other areas, like organization, are open to critique.

Writing a Scientific Review Article: Comprehensive Insights for Beginners

Ayodeji amobonye.

1 Department of Biotechnology and Food Science, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334, KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

2 Writing Centre, Durban University of Technology, P.O. Box 1334 KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4000, South Africa

Japareng Lalung

3 School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Gelugor 11800, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia

Santhosh Pillai

Associated data.

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

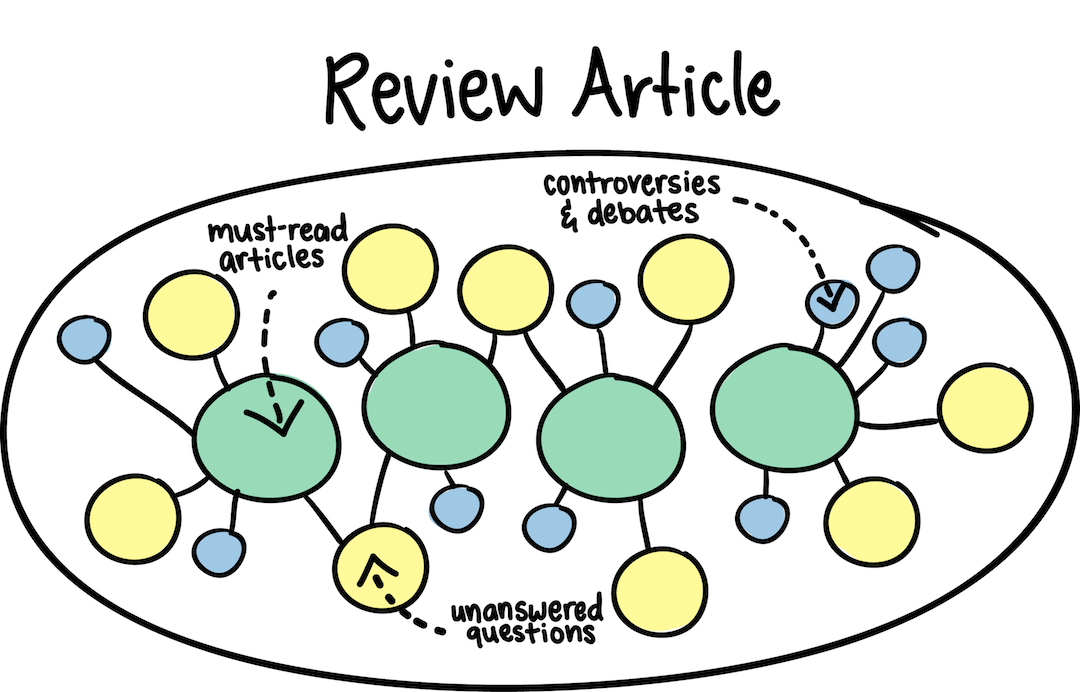

Review articles present comprehensive overview of relevant literature on specific themes and synthesise the studies related to these themes, with the aim of strengthening the foundation of knowledge and facilitating theory development. The significance of review articles in science is immeasurable as both students and researchers rely on these articles as the starting point for their research. Interestingly, many postgraduate students are expected to write review articles for journal publications as a way of demonstrating their ability to contribute to new knowledge in their respective fields. However, there is no comprehensive instructional framework to guide them on how to analyse and synthesise the literature in their niches into publishable review articles. The dearth of ample guidance or explicit training results in students having to learn all by themselves, usually by trial and error, which often leads to high rejection rates from publishing houses. Therefore, this article seeks to identify these challenges from a beginner's perspective and strives to plug the identified gaps and discrepancies. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a systematic guide for emerging scientists and to summarise the most important information on how to write and structure a publishable review article.

1. Introduction

Early scientists, spanning from the Ancient Egyptian civilization to the Scientific Revolution of the 16 th /17 th century, based their research on intuitions, personal observations, and personal insights. Thus, less time was spent on background reading as there was not much literature to refer to. This is well illustrated in the case of Sir Isaac Newton's apple tree and the theory of gravity, as well as Gregor Mendel's pea plants and the theory of inheritance. However, with the astronomical expansion in scientific knowledge and the emergence of the information age in the last century, new ideas are now being built on previously published works, thus the periodic need to appraise the huge amount of already published literature [ 1 ]. According to Birkle et al. [ 2 ], the Web of Science—an authoritative database of research publications and citations—covered more than 80 million scholarly materials. Hence, a critical review of prior and relevant literature is indispensable for any research endeavour as it provides the necessary framework needed for synthesising new knowledge and for highlighting new insights and perspectives [ 3 ].

Review papers are generally considered secondary research publications that sum up already existing works on a particular research topic or question and relate them to the current status of the topic. This makes review articles distinctly different from scientific research papers. While the primary aim of the latter is to develop new arguments by reporting original research, the former is focused on summarising and synthesising previous ideas, studies, and arguments, without adding new experimental contributions. Review articles basically describe the content and quality of knowledge that are currently available, with a special focus on the significance of the previous works. To this end, a review article cannot simply reiterate a subject matter, but it must contribute to the field of knowledge by synthesising available materials and offering a scholarly critique of theory [ 4 ]. Typically, these articles critically analyse both quantitative and qualitative studies by scrutinising experimental results, the discussion of the experimental data, and in some instances, previous review articles to propose new working theories. Thus, a review article is more than a mere exhaustive compilation of all that has been published on a topic; it must be a balanced, informative, perspective, and unbiased compendium of previous studies which may also include contrasting findings, inconsistencies, and conventional and current views on the subject [ 5 ].

Hence, the essence of a review article is measured by what is achieved, what is discovered, and how information is communicated to the reader [ 6 ]. According to Steward [ 7 ], a good literature review should be analytical, critical, comprehensive, selective, relevant, synthetic, and fully referenced. On the other hand, a review article is considered to be inadequate if it is lacking in focus or outcome, overgeneralised, opinionated, unbalanced, and uncritical [ 7 ]. Most review papers fail to meet these standards and thus can be viewed as mere summaries of previous works in a particular field of study. In one of the few studies that assessed the quality of review articles, none of the 50 papers that were analysed met the predefined criteria for a good review [ 8 ]. However, beginners must also realise that there is no bad writing in the true sense; there is only writing in evolution and under refinement. Literally, every piece of writing can be improved upon, right from the first draft until the final published manuscript. Hence, a paper can only be referred to as bad and unfixable when the author is not open to corrections or when the writer gives up on it.

According to Peat et al. [ 9 ], “everything is easy when you know how,” a maxim which applies to scientific writing in general and review writing in particular. In this regard, the authors emphasized that the writer should be open to learning and should also follow established rules instead of following a blind trial-and-error approach. In contrast to the popular belief that review articles should only be written by experienced scientists and researchers, recent trends have shown that many early-career scientists, especially postgraduate students, are currently expected to write review articles during the course of their studies. However, these scholars have little or no access to formal training on how to analyse and synthesise the research literature in their respective fields [ 10 ]. Consequently, students seeking guidance on how to write or improve their literature reviews are less likely to find published works on the subject, particularly in the science fields. Although various publications have dealt with the challenges of searching for literature, or writing literature reviews for dissertation/thesis purposes, there is little or no information on how to write a comprehensive review article for publication. In addition to the paucity of published information to guide the potential author, the lack of understanding of what constitutes a review paper compounds their challenges. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to serve as a guide for writing review papers for journal publishing. This work draws on the experience of the authors to assist early-career scientists/researchers in the “hard skill” of authoring review articles. Even though there is no single path to writing scientifically, or to writing reviews in particular, this paper attempts to simplify the process by looking at this subject from a beginner's perspective. Hence, this paper highlights the differences between the types of review articles in the sciences while also explaining the needs and purpose of writing review articles. Furthermore, it presents details on how to search for the literature as well as how to structure the manuscript to produce logical and coherent outputs. It is hoped that this work will ease prospective scientific writers into the challenging but rewarding art of writing review articles.

2. Benefits of Review Articles to the Author

Analysing literature gives an overview of the “WHs”: WHat has been reported in a particular field or topic, WHo the key writers are, WHat are the prevailing theories and hypotheses, WHat questions are being asked (and answered), and WHat methods and methodologies are appropriate and useful [ 11 ]. For new or aspiring researchers in a particular field, it can be quite challenging to get a comprehensive overview of their respective fields, especially the historical trends and what has been studied previously. As such, the importance of review articles to knowledge appraisal and contribution cannot be overemphasised, which is reflected in the constant demand for such articles in the research community. However, it is also important for the author, especially the first-time author, to recognise the importance of his/her investing time and effort into writing a quality review article.

Generally, literature reviews are undertaken for many reasons, mainly for publication and for dissertation purposes. The major purpose of literature reviews is to provide direction and information for the improvement of scientific knowledge. They also form a significant component in the research process and in academic assessment [ 12 ]. There may be, however, a thin line between a dissertation literature review and a published review article, given that with some modifications, a literature review can be transformed into a legitimate and publishable scholarly document. According to Gülpınar and Güçlü [ 6 ], the basic motivation for writing a review article is to make a comprehensive synthesis of the most appropriate literature on a specific research inquiry or topic. Thus, conducting a literature review assists in demonstrating the author's knowledge about a particular field of study, which may include but not be limited to its history, theories, key variables, vocabulary, phenomena, and methodologies [ 10 ]. Furthermore, publishing reviews is beneficial as it permits the researchers to examine different questions and, as a result, enhances the depth and diversity of their scientific reasoning [ 1 ]. In addition, writing review articles allows researchers to share insights with the scientific community while identifying knowledge gaps to be addressed in future research. The review writing process can also be a useful tool in training early-career scientists in leadership, coordination, project management, and other important soft skills necessary for success in the research world [ 13 ]. Another important reason for authoring reviews is that such publications have been observed to be remarkably influential, extending the reach of an author in multiple folds of what can be achieved by primary research papers [ 1 ]. The trend in science is for authors to receive more citations from their review articles than from their original research articles. According to Miranda and Garcia-Carpintero [ 14 ], review articles are, on average, three times more frequently cited than original research articles; they also asserted that a 20% increase in review authorship could result in a 40–80% increase in citations of the author. As a result, writing reviews can significantly impact a researcher's citation output and serve as a valuable channel to reach a wider scientific audience. In addition, the references cited in a review article also provide the reader with an opportunity to dig deeper into the topic of interest. Thus, review articles can serve as a valuable repository for consultation, increasing the visibility of the authors and resulting in more citations.

3. Types of Review Articles

The first step in writing a good literature review is to decide on the particular type of review to be written; hence, it is important to distinguish and understand the various types of review articles. Although scientific review articles have been classified according to various schemes, however, they are broadly categorised into narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses [ 15 ]. It was observed that more authors—as well as publishers—were leaning towards systematic reviews and meta-analysis while downplaying narrative reviews; however, the three serve different aims and should all be considered equally important in science [ 1 ]. Bibliometric reviews and patent reviews, which are closely related to meta-analysis, have also gained significant attention recently. However, from another angle, a review could also be of two types. In the first class, authors could deal with a widely studied topic where there is already an accumulated body of knowledge that requires analysis and synthesis [ 3 ]. At the other end of the spectrum, the authors may have to address an emerging issue that would benefit from exposure to potential theoretical foundations; hence, their contribution would arise from the fresh theoretical foundations proposed in developing a conceptual model [ 3 ].

3.1. Narrative Reviews

Narrative reviewers are mainly focused on providing clarification and critical analysis on a particular topic or body of literature through interpretative synthesis, creativity, and expert judgement. According to Green et al. [ 16 ], a narrative review can be in the form of editorials, commentaries, and narrative overviews. However, editorials and commentaries are usually expert opinions; hence, a beginner is more likely to write a narrative overview, which is more general and is also referred to as an unsystematic narrative review. Similarly, the literature review section of most dissertations and empirical papers is typically narrative in nature. Typically, narrative reviews combine results from studies that may have different methodologies to address different questions or to formulate a broad theoretical formulation [ 1 ]. They are largely integrative as strong focus is placed on the assimilation and synthesis of various aspects in the review, which may involve comparing and contrasting research findings or deriving structured implications [ 17 ]. In addition, they are also qualitative studies because they do not follow strict selection processes; hence, choosing publications is relatively more subjective and unsystematic [ 18 ]. However, despite their popularity, there are concerns about their inherent subjectivity. In many instances, when the supporting data for narrative reviews are examined more closely, the evaluations provided by the author(s) become quite questionable [ 19 ]. Nevertheless, if the goal of the author is to formulate a new theory that connects diverse strands of research, a narrative method is most appropriate.

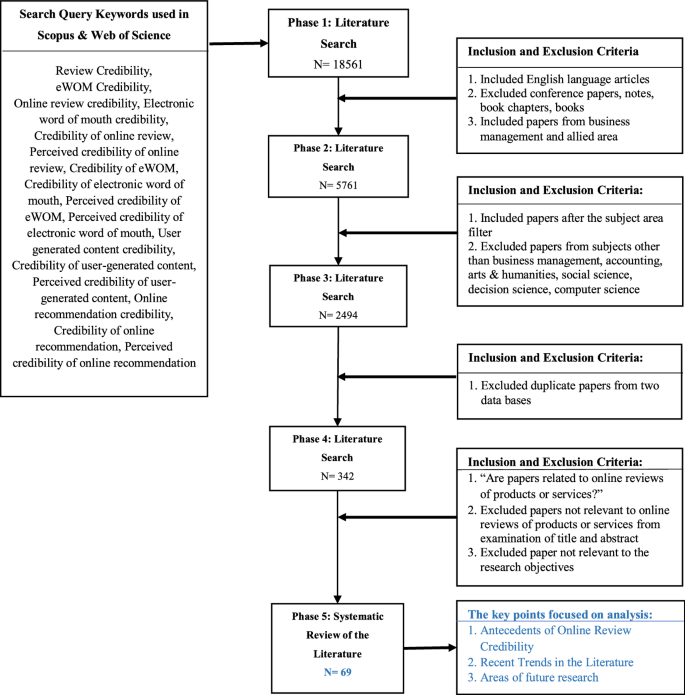

3.2. Systematic Reviews

In contrast to narrative reviews, which are generally descriptive, systematic reviews employ a systematic approach to summarise evidence on research questions. Hence, systematic reviews make use of precise and rigorous criteria to identify, evaluate, and subsequently synthesise all relevant literature on a particular topic [ 12 , 20 ]. As a result, systematic reviews are more likely to inspire research ideas by identifying knowledge gaps or inconsistencies, thus helping the researcher to clearly define the research hypotheses or questions [ 21 ]. Furthermore, systematic reviews may serve as independent research projects in their own right, as they follow a defined methodology to search and combine reliable results to synthesise a new database that can be used for a variety of purposes [ 22 ]. Typically, the peculiarities of the individual reviewer, different search engines, and information databases used all ensure that no two searches will yield the same systematic results even if the searches are conducted simultaneously and under identical criteria [ 11 ]. Hence, attempts are made at standardising the exercise via specific methods that would limit bias and chance effects, prevent duplications, and provide more accurate results upon which conclusions and decisions can be made.

The most established of these methods is the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines which objectively defined statements, guidelines, reporting checklists, and flowcharts for undertaking systematic reviews as well as meta-analysis [ 23 ]. Though mainly designed for research in medical sciences, the PRISMA approach has gained wide acceptance in other fields of science and is based on eight fundamental propositions. These include the explicit definition of the review question, an unambiguous outline of the study protocol, an objective and exhaustive systematic review of reputable literature, and an unambiguous identification of included literature based on defined selection criteria [ 24 ]. Other considerations include an unbiased appraisal of the quality of the selected studies (literature), organic synthesis of the evidence of the study, preparation of the manuscript based on the reporting guidelines, and periodic update of the review as new data emerge [ 24 ]. Other methods such as PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols), MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology), and ROSES (Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses) have since been developed for systematic reviews (and meta-analysis), with most of them being derived from PRISMA.

Consequently, systematic reviews—unlike narrative reviews—must contain a methodology section which in addition to all that was highlighted above must fully describe the precise criteria used in formulating the research question and setting the inclusion or exclusion criteria used in selecting/accessing the literature. Similarly, the criteria for evaluating the quality of the literature included in the review as well as for analysing, synthesising, and disseminating the findings must be fully described in the methodology section.

3.3. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analyses are considered as more specialised forms of systematic reviews. Generally, they combine the results of many studies that use similar or closely related methods to address the same question or share a common quantitative evaluation method [ 25 ]. However, meta-analyses are also a step higher than other systematic reviews as they are focused on numerical data and involve the use of statistics in evaluating different studies and synthesising new knowledge. The major advantage of this type of review is the increased statistical power leading to more reliable results for inferring modest associations and a more comprehensive understanding of the true impact of a research study [ 26 ]. Unlike in traditional systematic reviews, research topics covered in meta-analyses must be mature enough to allow the inclusion of sufficient homogeneous empirical research in terms of subjects, interventions, and outcomes [ 27 , 28 ].

Being an advanced form of systematic review, meta-analyses must also have a distinct methodology section; hence, the standard procedures involved in the traditional systematic review (especially PRISMA) also apply in meta-analyses [ 23 ]. In addition to the common steps in formulating systematic reviews, meta-analyses are required to describe how nested and missing data are handled, the effect observed in each study, the confidence interval associated with each synthesised effect, and any potential for bias presented within the sample(s) [ 17 ]. According to Paul and Barari [ 28 ], a meta-analysis must also detail the final sample, the meta-analytic model, and the overall analysis, moderator analysis, and software employed. While the overall analysis involves the statistical characterization of the relationships between variables in the meta-analytic framework and their significance, the moderator analysis defines the different variables that may affect variations in the original studies [ 28 , 29 ]. It must also be noted that the accuracy and reliability of meta-analyses have both been significantly enhanced by the incorporation of statistical approaches such as Bayesian analysis [ 30 ], network analysis [ 31 ], and more recently, machine learning [ 32 ].

3.4. Bibliometric Review

A bibliometric review, commonly referred to as bibliometric analysis, is a systematic evaluation of published works within a specific field or discipline [ 33 ]. This bibliometric methodology involves the use of quantitative methods to analyse bibliometric data such as the characteristics and numbers of publications, units of citations, authorship, co-authorship, and journal impact factors [ 34 ]. Academics use bibliometric analysis with different objectives in mind, which includes uncovering emerging trends in article and journal performance, elaborating collaboration patterns and research constituents, evaluating the impact and influence of particular authors, publications, or research groups, and highlighting the intellectual framework of a certain field [ 35 ]. It is also used to inform policy and decision-making. Similarly to meta-analysis, bibliometric reviews rely upon quantitative techniques, thus avoiding the interpretation bias that could arise from the qualitative techniques of other types of reviews [ 36 ]. However, while bibliometric analysis synthesises the bibliometric and intellectual structure of a field by examining the social and structural linkages between various research parts, meta-analysis focuses on summarising empirical evidence by probing the direction and strength of effects and relationships among variables, especially in open research questions [ 37 , 38 ]. However, similarly to systematic review and meta-analysis, a bibliometric review also requires a well-detailed methodology section. The amount of data to be analysed in bibliometric analysis is quite massive, running to hundreds and tens of thousands in some cases. Although the data are objective in nature (e.g., number of citations and publications and occurrences of keywords and topics), the interpretation is usually carried out through both objective (e.g., performance analysis) and subjective (e.g., thematic analysis) evaluations [ 35 ]. However, the invention and availability of bibliometric software such as BibExcel, Gephi, Leximancer, and VOSviewer and scientific databases such as Dimensions, Web of Science, and Scopus have made this type of analysis more feasible.

3.5. Patent Review

Patent reviews provide a comprehensive analysis and critique of a specific patent or a group of related patents, thus presenting a concise understanding of the technology or innovation that is covered by the patent [ 39 ]. This type of article is useful for researchers as it also enhances their understanding of the legal, technical, and commercial aspects of an intellectual property/innovation; in addition, it is also important for stakeholders outside the research community including IP (intellectual property) specialists, legal professionals, and technology-transfer officers [ 40 ]. Typically, patent reviews encompass the scope, background, claims, legal implications, technical specifications, and potential commercial applications of the patent(s). The article may also include a discussion of the patent's strengths and weaknesses, as well as its potential impact on the industry or field in which it operates. Most times, reviews are time specified, they may be regionalised, and the data are usually retrieved via patent searches on databases such as that of the European Patent Office ( https://www.epo.org/searching.html ), United States Patent and Trademark Office ( https://patft.uspto.gov/ ), the World Intellectual Property Organization's PATENTSCOPE ( https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/structuredSearch.jsf ), Google Patent ( https://www.google.com/?tbm=pts ), and China National Intellectual Property Administration ( https://pss-system.cponline.cnipa.gov.cn/conventionalSearch ). According to Cerimi et al. [ 41 ], the retrieved data and analysed may include the patent number, patent status, filing date, application date, grant dates, inventor, assignee, and pending applications. While data analysis is usually carried out by general data software such as Microsoft Excel, an intelligence software solely dedicated to patent research and analysis, Orbit Intelligence has been found to be more efficient [ 39 ]. It is also mandatory to include a methodology section in a patent review, and this should be explicit, thorough, and precise to allow a clear understanding of how the analysis was carried out and how the conclusions were arrived at.

4. Searching Literature

One of the most challenging tasks in writing a review article on a subject is the search for relevant literature to populate the manuscript as the author is required to garner information from an endless number of sources. This is even more challenging as research outputs have been increasing astronomically, especially in the last decade, with thousands of new articles published annually in various fields. It is therefore imperative that the author must not only be aware of the overall trajectory in a field of investigation but must also be cognizant of recent studies so as not to publish outdated research or review articles. Basically, the search for the literature involves a coherent conceptual structuring of the topic itself and a thorough collation of evidence under the common themes which might reflect the histories, conflicts, standoffs, revolutions, and/or evolutions in the field [ 7 ]. To start the search process, the author must carefully identify and select broad keywords relevant to the subject; subsequently, the keywords should be developed to refine the search into specific subheadings that would facilitate the structure of the review.

Two main tactics have been identified for searching the literature, namely, systematic and snowballing [ 42 ]. The systematic approach involves searching literature with specific keywords (for example, cancer, antioxidant, and nanoparticles), which leads to an almost unmanageable and overwhelming list of possible sources [ 43 ]. The snowballing approach, however, involves the identification of a particular publication, followed by the compilation of a bibliography of articles based on the reference list of the identified publication [ 44 ]. Many times, it might be necessary to combine both approaches, but irrespective, the author must keep an accurate track and record of papers cited in the search. A simple and efficient strategy for populating the bibliography of review articles is to go through the abstract (and sometimes the conclusion) of a paper; if the abstract is related to the topic of discourse, the author might go ahead and read the entire article; otherwise, he/she is advised to move on [ 45 ]. Winchester and Salji [ 5 ] noted that to learn the background of the subject/topic to be reviewed, starting literature searches with academic textbooks or published review articles is imperative, especially for beginners. Furthermore, it would also assist in compiling the list of keywords, identifying areas of further exploration, and providing a glimpse of the current state of the research. However, past reviews ideally are not to serve as the foundation of a new review as they are written from someone else's viewpoint, which might have been tainted with some bias. Fortunately, the accessibility and search for the literature have been made relatively easier than they were a few decades ago as the current information age has placed an enormous volume of knowledge right at our fingertips [ 46 ]. Nevertheless, when gathering the literature from the Internet, authors should exercise utmost caution as much of the information may not be verified or peer-reviewed and thus may be unregulated and unreliable. For instance, Wikipedia, despite being a large repository of information with more than 6.7 million articles in the English language alone, is considered unreliable for scientific literature reviews, due to its openness to public editing [ 47 ]. However, in addition to peer-reviewed journal publications—which are most ideal—reviews can also be drawn from a wide range of other sources such as technical documents, in-house reports, conference abstracts, and conference proceedings. Similarly, “Google Scholar”—as against “Google” and other general search engines—is more appropriate as its searches are restricted to only academic articles produced by scholarly societies or/and publishers [ 48 ]. Furthermore, the various electronic databases, such as ScienceDirect, Web of Science, PubMed, and MEDLINE, many of which focus on specific fields of research, are also ideal options [ 49 ]. Advancement in computer indexing has remarkably expanded the ease and ability to search large databases for every potentially relevant article. In addition to searching by topic, literature search can be modified by time; however, there must be a balance between old papers and recent ones. The general consensus in science is that publications less than five years old are considered recent.

It is important, especially in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, that the specific method of running the computer searches be properly documented as there is the need to include this in the method (methodology) section of such papers. Typically, the method details the keywords, databases explored, search terms used, and the inclusion/exclusion criteria applied in the selection of data and any other specific decision/criteria. All of these will ensure the reproducibility and thoroughness of the search and the selection procedure. However, Randolph [ 10 ] noted that Internet searches might not give the exhaustive list of articles needed for a review article; hence, it is advised that authors search through the reference lists of articles that were obtained initially from the Internet search. After determining the relevant articles from the list, the author should read through the references of these articles and repeat the cycle until saturation is reached [ 10 ]. After populating the articles needed for the literature review, the next step is to analyse them individually and in their whole entirety. A systematic approach to this is to identify the key information within the papers, examine them in depth, and synthesise original perspectives by integrating the information and making inferences based on the findings. In this regard, it is imperative to link one source to the other in a logical manner, for instance, taking note of studies with similar methodologies, papers that agree, or results that are contradictory [ 42 ].

5. Structuring the Review Article

The title and abstract are the main selling points of a review article, as most readers will only peruse these two elements and usually go on to read the full paper if they are drawn in by either or both of the two. Tullu [ 50 ] recommends that the title of a scientific paper “should be descriptive, direct, accurate, appropriate, interesting, concise, precise, unique, and not be misleading.” In addition to providing “just enough details” to entice the reader, words in the titles are also used by electronic databases, journal websites, and search engines to index and retrieve a particular paper during a search [ 51 ]. Titles are of different types and must be chosen according to the topic under review. They are generally classified as descriptive, declarative, or interrogative and can also be grouped into compound, nominal, or full-sentence titles [ 50 ]. The subject of these categorisations has been extensively discussed in many articles; however, the reader must also be aware of the compound titles, which usually contain a main title and a subtitle. Typically, subtitles provide additional context—to the main title—and they may specify the geographic scope of the research, research methodology, or sample size [ 52 ].

Just like primary research articles, there are many debates about the optimum length of a review article's title. However, the general consensus is to keep the title as brief as possible while not being too general. A title length between 10 and 15 words is recommended, since longer titles can be more challenging to comprehend. Paiva et al. [ 53 ] observed that articles which contain 95 characters or less get more views and citations. However, emphasis must be placed on conciseness as the audience will be more satisfied if they can understand what exactly the review has contributed to the field, rather than just a hint about the general topic area. Authors should also endeavour to stick to the journal's specific requirements, especially regarding the length of the title and what they should or should not contain [ 9 ]. Thus, avoidance of filler words such as “a review on/of,” “an observation of,” or “a study of” is a very simple way to limit title length. In addition, abbreviations or acronyms should be avoided in the title, except the standard or commonly interpreted ones such as AIDS, DNA, HIV, and RNA. In summary, to write an effective title, the authors should consider the following points. What is the paper about? What was the methodology used? What were the highlights and major conclusions? Subsequently, the author should list all the keywords from these answers, construct a sentence from these keywords, and finally delete all redundant words from the sentence title. It is also possible to gain some ideas by scanning indices and article titles in major journals in the field. It is important to emphasise that a title is not chosen and set in stone, and the title is most likely to be continually revised and adjusted until the end of the writing process.

5.2. Abstract

The abstract, also referred to as the synopsis, is a summary of the full research paper; it is typically independent and can stand alone. For most readers, a publication does not exist beyond the abstract, partly because abstracts are often the only section of a paper that is made available to the readers at no cost, whereas the full paper may attract a payment or subscription [ 54 ]. Thus, the abstract is supposed to set the tone for the few readers who wish to read the rest of the paper. It has also been noted that the abstract gives the first impression of a research work to journal editors, conference scientific committees, or referees, who might outright reject the paper if the abstract is poorly written or inadequate [ 50 ]. Hence, it is imperative that the abstract succinctly represents the entire paper and projects it positively. Just like the title, abstracts have to be balanced, comprehensive, concise, functional, independent, precise, scholarly, and unbiased and not be misleading [ 55 ]. Basically, the abstract should be formulated using keywords from all the sections of the main manuscript. Thus, it is pertinent that the abstract conveys the focus, key message, rationale, and novelty of the paper without any compromise or exaggeration. Furthermore, the abstract must be consistent with the rest of the paper; as basic as this instruction might sound, it is not to be taken for granted. For example, a study by Vrijhoef and Steuten [ 56 ] revealed that 18–68% of 264 abstracts from some scientific journals contained information that was inconsistent with the main body of the publications.

Abstracts can either be structured or unstructured; in addition, they can further be classified as either descriptive or informative. Unstructured abstracts, which are used by many scientific journals, are free flowing with no predefined subheadings, while structured abstracts have specific subheadings/subsections under which the abstract needs to be composed. Structured abstracts have been noted to be more informative and are usually divided into subsections which include the study background/introduction, objectives, methodology design, results, and conclusions [ 57 ]. No matter the style chosen, the author must carefully conform to the instructions provided by the potential journal of submission, which may include but are not limited to the format, font size/style, word limit, and subheadings [ 58 ]. The word limit for abstracts in most scientific journals is typically between 150 and 300 words. It is also a general rule that abstracts do not contain any references whatsoever.

Typically, an abstract should be written in the active voice, and there is no such thing as a perfect abstract as it could always be improved on. It is advised that the author first makes an initial draft which would contain all the essential parts of the paper, which could then be polished subsequently. The draft should begin with a brief background which would lead to the research questions. It might also include a general overview of the methodology used (if applicable) and importantly, the major results/observations/highlights of the review paper. The abstract should end with one or few sentences about any implications, perspectives, or future research that may be developed from the review exercise. Finally, the authors should eliminate redundant words and edit the abstract to the correct word count permitted by the journal [ 59 ]. It is always beneficial to read previous abstracts published in the intended journal, related topics/subjects from other journals, and other reputable sources. Furthermore, the author should endeavour to get feedback on the abstract especially from peers and co-authors. As the abstract is the face of the whole paper, it is best that it is the last section to be finalised, as by this time, the author would have developed a clearer understanding of the findings and conclusions of the entire paper.

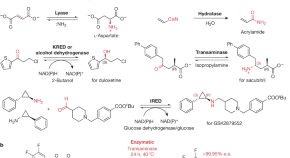

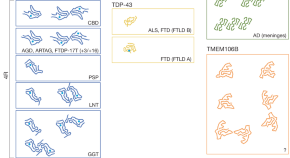

5.3. Graphical Abstracts

Since the mid-2000s, an increasing number of journals now require authors to provide a graphical abstract (GA) in addition to the traditional written abstract, to increase the accessibility of scientific publications to readers [ 60 ]. A study showed that publications with GA performed better than those without it, when the abstract views, total citations, and downloads were compared [ 61 ]. However, the GA should provide “a single, concise pictorial, and visual summary of the main findings of an article” [ 62 ]. Although they are meant to be a stand-alone summary of the whole paper, it has been noted that they are not so easily comprehensible without having read through the traditionally written abstract [ 63 ]. It is important to note that, like traditional abstracts, many reputable journals require GAs to adhere to certain specifications such as colour, dimension, quality, file size, and file format (usually JPEG/JPG, PDF, PNG, or TIFF). In addition, it is imperative to use engaging and accurate figures, all of which must be synthesised in order to accurately reflect the key message of the paper. Currently, there are various online or downloadable graphical tools that can be used for creating GAs, such as Microsoft Paint or PowerPoint, Mindthegraph, ChemDraw, CorelDraw, and BioRender.

5.4. Keywords