- How to Spot a Covert Narcissist

- How to Heal From Emotional Abuse

- How to Live With a Narcissist

- ADHD Vs PTSD

- The Pyramid of Personal Growth

- Importance of Aftercare in Addiction and Mental Health Rehab

- Types and Stages of Relapse

- Alcohol and Drug Detox

- No posts found for the specified taxonomy and term.

CONDITIONS WE TREAT

- Trauma & PTSD

- Dual Diagnosis

- Prescription Drugs

- Binge Eating

- Compulsive Overeating

UNIQUE METHOD

- THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY

LASTING APPROACH

- MULTI-DISCIPLINARY & HOLISTIC

- HEALING ENVIRONMENT

- LUXURY FACILITY

- TRAUMA INFORMED THERAPY

- Detox Process

- Relapse Prevention

- Behavioral Therapy

- Holistic Therapy

- Somatic Experience Therapy

- Equine Therapy

- RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT

Intensive residential treatment program starting from 4 weeks. Location: Mallorca, Zurich, London.

- ASSESSMENTS

Comprehensive second opinion assessments for both psychiatric and general health concerns. Location: Mallorca, Zurich, London

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

- Family Support

- Intervention

- Admit a loved one

- Admission Process

- ACCOMODATION

- IMAGE GALLERY

- Service Excellence

- Leisure Activities

- Residential Treatment

- Assessments

- MANAGEMENT & OPERATIONS

- WHY COGNIFUL

- CLINICAL EXCELLENCE

- COGNIFUL FAMILY

- ADVISORY BOARD

- ACCREDITATIONS

- PUBLICATIONS

- PERSONAL STORIES

- Search for:

Therapeutic Community

A therapeutic community (TC) is a highly organized and closely monitored environment for the treatment of people with substance use, mental health, or behavioral issues.

Based on the concept that the people in the community are the key to managing the change, TCs promote people’s support, accountability, and engagement in the therapeutic processes. Studies show that TC programs can be quite effective in encouraging patients to achieve recovery. For instance, research has indicated that TC members undergo substantial changes in their substance use, social adjustment, and criminal behavior as compared to those in conventional treatment facilities [ 1 ].

These positive outcomes are attributed to the characteristics of TCs, such as their high level of engagement, as well as the emphasis on personal change and support from peers.

What Is A Therapeutic Community

A therapeutic community is a residential setting in which clients with conditions such as addiction, mental illness, or behavioral disorders, live and engage in meaningful activities with other individuals who are also in the process of recovery. It began in the mid-twentieth century and has been developed and refined into several activities designed to enhance people’s feelings of belonging, shared responsibility, and character.

Historical Background

Therapeutic communities can be traced back to post-World War II Britain. The first TCs were established in psychiatric hospitals as an attempt to change the traditional, authoritative approach to treating patients. Early workers such as Maxwell Jones also stressed the principles of community, equality, and decentralized decision-making in the process of therapy [ 2 ].

The concept moved to the United States in the 1950s and 1960s and was applied to substance abusers. Synanon was created in 1958 and was one of the first TCs in the U. S. It served as the prototype for other programs. In time, TCs evolved to treat various conditions such as mental health disorders, criminal behavior, and homelessness.

Core Principles of Therapeutic Communities

Now let’s have a look at some of the key aspects and core principles of therapeutic communities.

Reciprocal Help and Social Pressure

Peer support helps members by sharing their experiences and this kind of support might not be fully provided by the professional staff.

People in various stages of recovery are viewed as inspirational to others and provide real-life examples of change and guidance. There is always collective responsibility in the community and everyone is concerned with the progress of every other person.

Structured Environment

Daily routine organization enhances orderliness and routine in the lives of the members and hence structured schedules are appropriate.

Work and social activities including Daily chores and interactions help the child develop responsibility and learn how to interact with others.

Therapeutic activities including psychotherapy in groups, individual counseling, and educational sessions are used in daily practice.

Democratic Participation

Community meetings enable the members to deliberate on matters, make decisions, and solve problems through majority rule.

Shared governance makes members responsible for the rules and policies that are in the community because they have a voice in the same.

Personal Development

Self-reflection in individuals helps self-observe their actions, thoughts, and feelings.

Skill building covers skills for daily living, interpersonal skills, and behavioral skills including communication, problem-solving, and emotional management skills.

Personal and social goal setting in TC programs helps people with personal objectives to strive for achieving them by being assisted by other people.

How Therapeutic Communities Work

The therapeutic community is organized in a way that can help foster change and also provide protection for the client.

Here are some key components of how Therapeutic Communities operate:

Membership and Roles

Members: Members of the community are recruited either willingly or through recommendations from hospitals or the courts. Every member is supposed to contribute to the community and adhere to the rules of the community.

Staff: There are trained personnel in the community such as therapists, counselors, and social workers. They coordinate the therapy sessions, offer advice and support, and make sure that the functioning of the community runs smoothly.

Peers: People in the various stages of the recovery process help others. Newcomers may feel overwhelmed and may not know how to go about things; this is when the older members come in to teach the new members how to go about things.

Therapeutic Activities

Group Therapy: Group therapy meetings are held regularly and help the members to talk about their experiences, problems, and ideas. These sessions help in fostering self-awareness and empathy.

Individual Counseling: Individual counseling or therapy sessions allow members to talk with a counselor or therapist to deal with specific problems, and to work on their recovery plans.

Work Therapy: They engage in different tasks including washing, preparing meals, or taking care of other tasks within the community or the workplace. These tasks help to develop such values as responsibility, teamwork, and practical skills [1].

Educational Programs: In this regard, TCs provide educational sessions on life skills, vocational training, and health education. These programs are meant to help members gain the necessary skills to reintegrate into society effectively.

What Is The Purpose Of A Therapeutic Community

A therapeutic community has several functions that are meant to facilitate the change and growth of the individuals who need it for substance abuse, mental health, or behavioral problems.

Creating Supportive Environments

The main goal of a therapeutic community is to provide the necessary conditions for the change and growth of a person and the treatment of the disorder. To achieve this, TCs try to establish a strong community of members where everyone feels accepted and can support one another, thereby eliminating loneliness [ 3 ].

Promoting Personal Responsibility

TCs focus on individualism and personal responsibility. They are expected to engage in the various activities of the community such as group therapy, educational sessions, and other tasks within the community. This structured approach assists in the recovery process by enabling the patients to take responsibility for their progress and encourages positive behavioral change.

Fostering Peer Assistance and Tutoring

This is because TCs also aim at promoting peer support and mentorship among the participants. Older members are always involved in training new members and helping them in any way they can. This peer-to-peer interaction helps in improving the social skills, empathy, and mutual respect among the members hence providing support for long-term recovery.

Promoting Self-development and Skills Acquisition

TCs provide prospects for professional and personal development and acquisition of skills in different fields. Members gain practical skills through education, vocational training, and work therapy that improves the possibilities of re-absorption into society. It is a comprehensive approach that not only solves the pressing problems but also provides people with the means to live a stable life in the future.

Empowering Individuals

Another important goal of therapeutic communities is the process of empowering. In this way, TCs engage the members in decision-making and governance that enables them to take charge of their lives and make constructive decisions. It is empowering to the patient, which leads to increased self-esteem, and tenacity to fight the illness and reclaim their lives.

What Happens At A Therapeutic Community Program

A therapeutic community program is a method of treatment and recovery, which is aimed at the effective and healthy modification of individual and group behavior.

Admission and Assessment

The TC program starts with admission and people enroll themselves or are compelled by healthcare practitioners or the legal system. Initially, the member is evaluated to determine their requirements, potential, and difficulties in joining the program. This assessment is useful in determining the goals and needs of the person and therefore the right program to apply.

Orientation and Integration

New members also have to go through an orientation that introduces them to the basic rules, activities, and expectations of the TC. This phase is important as it creates social capital for the new members of the community. Senior members are usually there to help the new members during this transition.

Structured Daily Routine

The daily schedule of a TC program is rather rigid, which is based on the principles of order and discipline. Members engage in different activities that are intended to foster individual and social growth. These activities may include:

Group Therapy: Structured meetings that involve group sharing of experiences, problems, and achievements among the members.

Work Therapy: Maintenance tasks like cooking, cleaning, or sweeping within the community so that people learn to be accountable and contribute to the group.

Educational Workshops: Services that can be provided are sessions on life skills, vocational training, health education, and other areas that relate to individual development and recovery.

Therapeutic Interventions

In the TC programs, some intercessions are used in the treatment of the members depending on their needs. These interventions may include:

Individual Counseling: Individual counseling with a counselor/therapist to discuss individual concerns, establish objectives, and navigate conflicts.

Behavioral Therapy: Methods for changing maladaptive patterns and building effective ways of dealing with stress.

Family Therapy: Engaging family members in the therapeutic process to enhance the support system and communication channels.

Community Living and Accountability

Community living is the cornerstone of the TC modality program, where members are engaged in decision-making and communal activities. It fosters responsibility, cooperation, and supervision, which are crucial for individual development and recovery or abstinence.

Gradual Reintegration and Aftercare

While in the TC program, members follow a program that will help prepare them for reintegration into society. This phase involves planning for transition and seeking aftercare, which may include outpatient services, support groups, and vocational services. They assist members in sustaining their progress, adding to the progress made, and negotiating transitions after leaving the therapeutic community.

This modality is often used in Residential Therapeutic Communities, where patients are encouraged to live together with other patients in a recovery-oriented setting.

References

1. Sage Journals. How therapeutic communities work: Specific factors related to positive outcome. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0020764012450992

2. Science Direct. Therapeutic Community. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/nursing-and-health-professions/therapeutic-community

3. Wikipedia. Therapeutic Community. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therapeutic_community

Is Therapeutic Community Programs Appropriate For All Ages?

Adolescents and young adults can also be treated in therapeutic communities, but there are programs for them different from those for adults. Such programs focus on age-related concerns and offer services to respond to developmental concerns.

What Are The Ways Of Managing Conflicts In A Therapeutic Community?

Conflict resolution in TCs is typically characterized by formal procedures, where the members of the community talk about the conflicts, seek help from the staff or other members of the community, and follow the rules of the community that are aimed at creating a supportive environment.

What Is The Significance Of Spirituality In Therapeutic Communities?

Some TCs include spirituality in their treatment plans, but most programs address the comprehensive growth of patients without reference to religion. Cognitive restructuring is used in the recovery process as people are encouraged to discover their own beliefs while respecting the rights of others to have a different opinion.

Yes, there are rules in therapeutic communities concerning medications so that patients are safe and compliant with their treatment. Skilled personnel are employed to administer medicine, observe the impact, and offer assistance to people who need to take medicine to manage their conditions.

HOW COGNIFUL CAN HELP

COGNIFUL is a leading provider of luxury addiction and mental health treatment for affluent individuals and their families, offering a blend of innovative science and holistic methods with unparalleled individualised care.

A UNIQUE METHOD

Our program consists of treating only one client at a time individually designed to help you with all the problematic aspects of your life. All individual treatment sessions will be held at your private residence.

Your program is designed based on your personal needs. The team will exchange daily information and adjust the schedule as we go. Our therapists will work with you treating the root causes and not just the symptoms and goes beyong your stay to ensure lasting success.

Our biochemical imbalance can be affected by diet and stressful life events, but it often goes back to genetics and epigenetics. We do specific biochemical laboratory testing to determine an individual’s biochemical imbalance. Combining the results of the lab tests with anamnestic information and clinical tests, we prescribe an individualized and compounded vitamin, mineral, nutrient protocol to help recover from various disease states.

Our experts combine the best from psychological treatment, holistic medicine to support you individually and providing complementary therapies all coordinated from one source working complementing each other integrative.

Using latest cutting-edge technology-based therapies such as Neurofeedback, tDCS, and SSP, we can track the biological patterns of your body, giving us valuable insight into your health and well-being as well support your brain and body performance and recovery with neuromodulation.

Complex trauma is often a key factor to distress mental and physical state. The Balance provides a safe space along integrated trauma treatment methods to enable healing.

Send Admission Request

Define treatment goals, assessments & detox, psychological & holistic therapy, family therapy, refresher visit, accreditations.

The Current Importance of Therapeutic Communities

Incorporating multiple therapeutic modalities for addiction care..

Posted April 3, 2021 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- What Is Addiction?

- Find counselling to overcome addiction

Outside the United States, the therapeutic community (TC) model is widely embraced, with currently 65 countries offering treatments and over 3,000 TC models incorporated into community settings across the world. Since its global expansion beginning in the 1980s, the “modern TC” has evolved to adapt to the unique needs and structures of the setting, such as prisons, women’s treatment centers, and shelters. In this sense, such institutions carry therapeutic principles and concepts, which are often complemented with other treatment modalities. As TCs expanded in number, they’ve adapted to fit the needs of particular settings and populations

Within the treatment frame at TCs, individuals are encouraged to explore forms of gratification that might be found in sharing life with others – a necessary drive force of life that medications alone cannot fix. In addition to meaningful peer relationships, individuals are held accountable for their role in sustaining the social fabrics within their community. At San Patrignano, one of the most renowned TCs located in Central Italy , residents are engaged in craftsmanship and employment opportunities that foster self-efficacy and belongingness amongst their peers. TCs aim to integrate structural frameworks to facilitate the generation of self-mastery, such as involvement in work or education . As an example, residents who work in the food and agricultural sectors take active roles in sustaining the basic sustenance of others. Being able to offer the fruits of one’s hard work offers a unique layer of human connection that further strengthens social cohesion.

Some of the key points in the addiction recovery process are connectedness, hope, identity , meaning, and empowerment. Two important predictors of well-being in recovery include social contagion (i.e. the time spent with other people in recovery) and meaning (i.e. the meaningfulness of activities spent within social time). The main goal out of supporting these individuals, who are often marginalized due to stigma , is to improve access to social engagement in meaningful ways. There is the belief that attaining deeper social and community capital enables scaffolding to build the personal skills and resources essential for long-term recovery, which is the central element guiding therapeutic communities.

Growing Pains

It is not without saying that TCs have experienced considerable growing pains over the thirty years, and some of this history has been highlighted in popular media in recent months. TCs around the world have carried a treatment plan that was at times suboptimal. This approach was marked by punishment to reinforce ideal behavior, which was not aligned with the standards of care employed today.

Furthermore, TCs often believed that medications for mental health and substance use issues were harmful to the individual in recovery and viewed them more as a “crutch” than a necessary facilitator for healthy recovery. However, such issues have been addressed by increased receptivity to mediation-assisted treatments.

Current Importance

The current importance of therapeutic communities isn’t something to be under-looked. There is sufficient evidence to support invoking multiple modalities to treat a substance use disorder, rather than a reliance on stand-alone treatment (Pedros Ruiz, 2011). Incorporating aspects of TCs, such as peer support and vocational responsibility, is a promising future direction for substance use disorder treatments.

For individuals involved in the criminal justice system, research supports that therapeutic community principles lead to improved outcomes once they re-enter their community, such as lower rates of re-incarceration and improved social functioning. This is even the case for individuals who have not participated in a prison that holds a TC structure, yet enter into the continuity of care that integrates TC principles once they re-enter society (Sacks, 2012).

Many therapeutic communities also offer admission to the residential community as an alternative to prison. The TC often advocates for the individual and takes steps necessary to ensure that the residents are supported in their petitions that are required to avoid imprisonment. As an example, in the case of San Pa, if there are criminal cases pending for the individual, the community enlists a network of nearly 3,000 lawyers who practice throughout Italy and collaborate with SanPa’s legal office at a negotiated price. Residents are provided consultations, management of their cases, and filing of applications absolutely free of charge.

Integration of a multimodal approach might be necessary to meet the comprehensive needs of individuals with severe substance use disorders. For those subpopulations of individuals with substance use disorder who are deemed unresponsive to treatment attempts, it is thought they might uniquely benefit from the TC model.

Jonathan Avery, MD, is the Director of Addiction Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College and New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Joseph Avery, JD, MA, is a psychologist and attorney.

- Find Counselling

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United Kingdom

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

PERSPECTIVE article

The therapeutic community: a unique social psychological approach to the treatment of addictions and related disorders.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, NYU School of Medicine, New York City, NY, United States

- 2 Center for Integrative Addiction Research (CIAR), Grüner Kreis Society, Vienna, Austria

- 3 University Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapeutic Medicine, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria

- 4 Institute for Religious Studies, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

The evolution of the contemporary Therapeutic Community (TC) for addictions over the past 50 years may be characterized as a movement from the marginal to the mainstream of substance abuse treatment and human services. TCs currently serve a wide array of clients and their diverse problems; through advances in research in treatment outcomes, the composition of staff has been reshaped, the duration of residential treatment has been reduced, the treatment goals have been reset and, to a considerable extent, the approach of therapy itself has been modified. An overview of the TC as a distinct social-psychological method for treating addiction and related disorders is provided by this paper. Included in this is a focus on the multifaceted psychological wounds that consistently show a strong association with addiction and thereby require initiating a recovery process characterized by life-style and identity changes.

Introduction

We intend here to give a brief overview of the development of the therapeutic communities (TCs) for the treatment of addictions. After a brief historical introduction (pt 1), the core dimensions of the TC treatment approach will be introduced and the characteristic peculiarities will be discussed (pt 2). Based on this, we will describe the “community as method” approach in more detail and show different approaches to empirically depict the change process that the patients go through during their stay in the TC (pts 3–5). In line with this, the state of research regarding the possible change processes taking place in the TC will be summarized (pt 6) and possible other forms of application of TCs for special populations and settings will be discussed (pt 7). Lastly, we conclude by summarizing the TC key elements, also in comparison to other therapeutic approaches (pt 8).

The Evolution of the TC

According to DeLeon ( 1 ) “the idea of therapeutic community recurs throughout history, implemented in different incarnations. Communities that teach, heal, and support, appear in religious sects and utopian communes, as well as in spiritual, temperance, and mental health reform movements.” (p.11). In correspondence to this, indirect influences on TC concepts, beliefs, and practices can be found in religion, philosophy, psychiatry, and the social and behavioral sciences. Thereby, early prototypes of communal healing and support can be traced back to classical antiquity. Remarkably, there are two elements in ancient medical texts that can also be applied to modern TCs for addictions: 1) the mental illness (or the disease of the soul) manifests itself as a disease of the whole person and is characterized in particular by problems with self-control on the behavioral and emotional level and 2) the healing of the disease (or the soul) happens through the involvement of a community or group. Then, as now, violations of the rules of the community were sanctioned or had negative consequences for the individual. In this sense, the group also determines the type and extent of the sanctions, which in the case of serious violations, especially against the integrity of the group, can also mean expulsion from the community ( 2 ).

Although the TC for addictions has been influenced by numerous sources, both current and historical teachings can be found herein, the actual term “therapeutic community” can be considered modern. This was first used to describe psychiatric TCs in Great Britain during the 1940s ( 3 ). However, it is unclear, how these first TCs (for general psychiatric patients) have influenced the development of the TCs focusing on addictions, which began in the United States ( 4 ). In North America, Charles Dederich, as a former alcoholic himself and member of “Alcoholics Anonymous”, founded one of the first self-help groups for opiate addictions in 1958 named “Synanon”. Primarily, he was inspired by the works of the writer and philosopher R. W. Emerson and a religious organization called “The Oxford Group”, which saw itself as a moral antipode to international armament. This group was also influenced by “Alcoholics Anonymous” and their 12-step method of treating alcohol addiction. So-called Synanon houses and Synanon villages developed, in which former addicts renounced their old way of life, concentrating instead on the present moment and communal work, which was based on values such as truth and sincerity ( 5 ).

In Europe the first TCs shaped by American models were founded in the mid-1960s. A self-help group called “Release” was setup in England in 1967. As a result of the success of “Release” TCs were independently developed in several countries across Europe from the 1960s and 1970s ( 5 ). As illustrated, for example, by Cortini, Clerici, and Carrà ( 6 ), today we can certainly speak of a unique evolutionary strand of the TC movement in Europe. Furthermore, the authors rightly argued that a comparison of both the European and the American treatment routes could contribute to a more differentiated discussion of the TC treatment concepts in general as well as guide their further development. Although different variations of TCs have developed in the United States as well as in Europe independently from each other, they still share some key core elements which will be further characterized now.

The TC Perspective

Comprehensive accounts of the TC theory, model, and method are contained in De Leon ( 1 , 7 ). The TC theory, “community as method” shapes its program model and its unique approach. The paradigm is comprised of four interconnected views of substance use disorder and how the individual, process of recovery, and living healthy are defined.

View of the Disorder

The abuse of drugs is considered a comprehensive disorder affecting the whole person and many, if not all, parts of functioning. It is evident that those suffering from drug abuse have problems not only with cognition and behavior, but also mood disturbances ( 8 ). The substance abusing individual’s thoughts may be classed as unrealistic or even disorganized, their values are mixed up, antisocial or even nonexistent ( 9 , 10 ). All too often they suffer from deficits in comprehension, writing, reading, and so-called “marketable skills” ( 11 ). Spiritual struggles, or even moral problems, are consistently apparent whether expressed in psychological or existential terms ( 12 ). Thus, it can be argued that the problem is with the individual and not the substance abused; in other words, addiction can be seen as a symptom rather than the essence of their disorder ( 13 ). This perspective may also be one of the main characteristics of the TC and one of the major differences between the TC model and standard psychiatric inpatient treatment, which is much more based on symptom-oriented diagnostic systems such as the International Classification of Diseases in 11 th revision [ICD 11; ( 14 )] or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders Version 5 [DSM 5; ( 15 )].

Accordingly, in terms of an attachment based therapeutic approach, it can be said that the TC tries to break the bond to a substance and instead direct the patient toward forming a bond to the community. Thereby, the TC can serve as an attachment figure, acting as a safe haven in which one can enter, but also as a secure base from which one can start again into a new (drug-free) life ( 16 ). While clinical evidence suggests the important role of the community for the functioning of affect regulation ( 17 ), some additional support comes from a neuro-evolutionary perspective e.g., through the “social baseline” model, which proposes “that social species are hard-wired to assume relatively close proximity to conspecifics, because they have adopted social proximity and interaction as a strategy for reducing energy expenditure relative to energy consumption” [( 18 ), p. 19; see also ( 19 ), for a more general discussion].

View of the Person

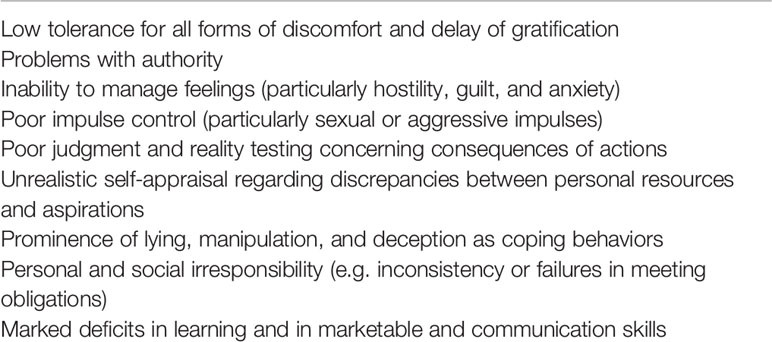

In TCs, rather than classifying individuals according to their patterns of drug abuse, they are instead delineated along degrees of “psychological dysfunction” and “social deficits”. Additionally, many residents in TCs have manifested vocational and educational problems; society’s mores are either ignored or totally avoided. These residents are often from a socially depressed sector. A better term for their TC experience is “habilitation”, the development of a social, productive, and “conventional” lifestyle for the first time. However, among residents from more advantaged backgrounds, the term “rehabilitation” is judged more appropriate since it emphasizes a return to a rejected lifestyle previously lived and known. Despite apparent differences in social background, psychological problems, or drug preferences most individuals admitted to TCs share profound clinical characteristics that center around antisocial dimensions or immaturity ( Table 1 ). Whether they precede or follow serious involvement with drugs, these characteristics are commonly observed to correlate with substance dependency. Crucially, in TCs, a change for the better in these characteristics is thought to be essential for long-term recovery ( 1 ).

Table 1 Typical behavioral, cognitive, and emotional characteristics of substance abusers in therapeutic communities.

From the TC perspective, for recovery to occur a change in lifestyle, in addition to social and personal identity, is considered vital. Thus, the main psychological goal of treatment is an attempt to change negative patterns of thinking, behavior, and feeling that predisposes an individual to drug use; meanwhile the main social goal is to develop skills, attitudes, and instill values necessary for a responsible, drug-free lifestyle. Stable recovery, however, is dependent on a successful integration of these psychological and social goals. Without insight behavioral change is unstable; however, without lived experience mere insight is insufficient. Several key assumptions underlie the recovery process in the TC ( 1 ).

Recovery depends on pressures, both positive and negative, to change. For example, certain people might seek help due to stressful external pressures; others may be moved by more intrinsic factors. For everyone, however, sticking to a treatment program requires a continual internal motivation to change. Thus, some elements of the treatment approach are designed to either sustain motivation or enable early detection of signals that the subject might terminate treatment prematurely ( 1 ).

Self-Help and Mutual Self-Help

In practical terms treatment is not provided per se; rather, it is provided to all individuals in the TC through the daily regimen of groups, seminars, work, recreation and meetings, and its staff and peers. The efficacy of these elements, however, depends on the individual: they must engage fully in the treatment regimen for best outcomes. In self-help recovery the individual must make the main contribution to his/her change process. By contrast, in mutual self-help the primary messages of personal growth, “right living”, and recovery are mediated by peers through discourse and sharing experiences in groups, providing examples as role models, and acting as encouraging, supportive friends in daily interactions ( 1 ).

Social Learning

Lifestyle changes occur in a social context. Negative behavioral attitudes, patterns, and roles, in general, are not acquired in isolation, nor can they be ameliorated in isolation. Thus, this presupposition is the basis for the view that a peer community can facilitate recovery. Social responsibility as a role is learned by acting the role within a community of one’s peers ( 1 ).

View of Right Living

TCs adhere to certain values, precepts, and a social perspective that guides and reinforces recovery. For instance, there exist community sanctions that address antisocial attitudes and behavior: emphasis is also placed on changing the negative values of irresponsible or exploitative sexual conduct, in jails, negative peers or “the streets”. Positive values, by contrast, are given a positive emphasis as being essential to both social learning and personal growth. These values include such concepts as truth and honesty (both in word and deed), a strong work ethic, a feeling of responsibility for others (e.g. being one’s brother’s or sister’s keeper), a sense of achievement and that all rewards have been earned, self-reliance, personal accountability, community involvement, and social manners. The values of “right living” are reinforced constantly in various informal and formal ways (e.g. signs, seminars, in groups, and community meetings) ( 1 ).

In order to counter the concerns of critics, attempts have been made to date to scientifically prove the effectiveness of the treatment concept ( 20 ). However, the therapeutic concept of the TC is being questioned due to the lack of randomized clinical studies with regard to the therapeutic success. Despite these criticisms, “community as method” can still be seen as the top principle of the TC, both in terms of the treatment and the research into change processes in the TC. This method will now be explained in more detail ( 21 ).

TC Approach: Community as Method

The approach of TC can be summarized by the phrase “community as method”. The definition of community as method offered by theoretical writings is as follows: The purposive use of the community to teach individuals to use the community to change themselves. Thus, the fundamental assumption that underlies the concept of community as method is: individuals obtain maximum educational and therapeutic impact when they engage in, and learn to use, all of the diverse elements of the community as tools for self-change. Therefore, “community as a method” means that the community is both context and mediator for individual change and social learning. Its membership establishes expectations or standards of participation in the community. It assesses how individuals are meeting these expectations and respond to them with strategies that promote continued participation ( 1 ).

Community, the Individual, and the Process of Change

Everyone uses the expectations and context of their community to change and learn. Living up to the expectations of their community requires that an individual continually change their behaviors, attitudes, and emotional management. Conversely, avoidance of, or difficulties in living up to community expectations can also result in an individual’s growth through continual self-examination, re-motivation to engage in trial and error learning, and re-committing to the process of change. Thus, the drive to cohere to what the community expects for participation compels residents to pursue personal goals of psychological growth and socialization. The whole process can be summed up in the phrase: if you participate, then you will change ( 1 ).

TC Research: Direct Evidence for Social and Psychological Changes

A considerable scientific knowledge base has been developed over the past four decades, with the addition of follow-up studies on thousands of individuals treated in TCs. The most extensive body of research bearing on the efficacy of TC programs involving addiction has been collected from numerous field outcome studies. All of these studies utilized similar longitudinal designs that followed admissions to TCs during treatment and 1–5 years (and in one study up to 12 years) after leaving the index treatment. These studies consistently show that TC admissions have poor profiles with regard to severity of substance use, psychological symptoms and social deviance. The striking replicability across studies has left little doubt as to the reliability of the overarching conclusion: There is a consistent correlation between treatment retention in TCs and positive post-treatment outcomes. This conclusion is additionally supported in the smaller number of controlled and comparative studies involving TC programs [for enhanced reviews of the TC outcome literature in North America, see ( 21 ); and internationally, see ( 20 )].

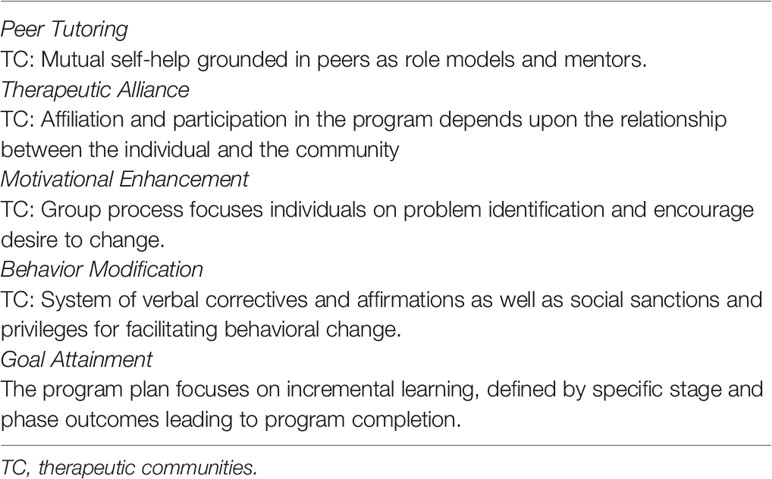

Indirect Evidence Based Social Psychological Principles and Practices Are Embedded Within Community as Method

The TC for addictions emerged practically, outside both mainstream mental health and social science. Nevertheless, a unique theoretical social learning approach has evolved, captured in the phrase “community as method”. The latter, however, contains elements and practices that are familiar and supported by abundant social–psychological and behavioral research outside of TCs ( Table 2 ). Similarly, behavioral training and social learning principles are obvious, e.g. vicarious learning, the training, and acquisition of social roles and social reinforcement. As discussed elsewhere, these principles are naturally mediated by the context of community living ( 1 ).

Table 2 Indirect evidence: examples of TC program and practice elements that are evidence-based in the behavioral and social-psychological research literature.

Overall, the weight of the direct evidence from all sources (e.g., multiple sources of outcome research in North America which includes single program controlled studies, cost–benefit studies, meta-analytic statistical surveys, and multi-program field effectiveness studies) supports the conclusion that the TC is both a cost-effective and therapeutically effective treatment for certain substance abuser subgroups, particularly those with severe drug use, social and psychological problems. This conclusion is supported by considerable indirect evidence from social psychological principles and practices that are inherent within community as method. Other strategies that are informed by evidence can be incorporated to enhance rather than substitute for community as method, the primary approach ( 1 ).

TC model was developed further or adapted to different circumstances or patient groups. These changes will be briefly explained below.

TC Applications to Special Populations and Settings

The traditional TC model described herein is in actuality the prototype of a variety of TC oriented programs. Today TC modality largely consists of a wide range of programs that serve a variety of patients who use diverse drugs and who, in addition to their chemical abuse, present with complex psychological and social problems. Clinical requirements as well as client differences, in addition to the reality of funding, have encouraged the development of modified residential TC programs that offer shorter planned durations of stay (3, 6, and 12 months) as well as TC-oriented outpatient ambulatory models and day treatments. Correctional facilities, medical and mental hospitals, and community residences and shelters, having become overwhelmed with alcohol and drug abuse problems, have implemented TC programs within these settings ( 11 ).

Most community-based traditional TCs have either incorporated new interventions or expanded their social services to address the diverse needs of their members. These changes and additions include specific primary healthcare geared toward individuals with AIDS or who are HIV-positive, family services, relapse prevention training, aftercare services specifically for special populations such as substance-abusing inmates leaving prison treatment, mental health services, components of 12-step groups, and other evidence-based practices (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing). These modifications and additions enhance, but are not intended as a substitute for, the fundamental TC approach: Community as method. Research literature documents the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of modified TCs for special populations such as homeless and mentally ill chemical abusers, those in criminal justice settings and adolescents ( 1 , 22 – 26 ).

Concluding Remarks

The fundamental, primary foundation for the TC program model, its distinctive methodology, community as method, and its longer than usual treatment duration is the recovery perspective. Fundamentally, multi-dimensional (“whole person”) change necessarily requires a multi-interventionist approach that is sustained for a sufficient amount of time ( 1 ).

The TC for addictions is arguably one of the first formal treatment paradigms that is overtly recovery oriented. Although Alcoholics Anonymous and similar programs, focused on an approach of mutual self-help, facilitate recovery these programs differ from TC by representing their service as support rather than treatment. Meanwhile, pharmacological treatment paths, such as methadone, have as their putative treatment objective the outright elimination or, at the very least, reduction of the abuse of opiates. Empirically based approaches to behavior, such as motivational enhancement (MET), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and contingency contracting, focus upon reducing the abuse of the targeted drug. From the TC’s perspective, however, the main goal of treatment is “recovery” which is broadly defined as identity and lifestyle changes. These changes involve abstaining from the illicit use of narcotics (and other drugs), the total elimination of social deviance and the development of positive social values and appropriate behavior ( 1 ). Thus, the mission, and that which distinguishes TC from other treatment paths, is promoting recovery and encouraging living right.

Author Contributions

GDL wrote the draft of the manuscript. HU read the manuscript and made some critical comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. De Leon G. The Therapeutic Community: Theory, Model, and Method . Springer Publishing Company: New York (2000).

Google Scholar

2. Slater MR. An Historical Perspective of Therapeutic Communities. Thesis Propposal to the M.S.S. program . University of Colorado at Denver (1984).

3. Jones M. The concept of a therapeutic community. Am J Psychiatry (1956) 112(8):647–50. doi: 10.1176/ajp.112.8.647

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Debaere V, Vanheule S, Inslegers R. Beyond the “black box” of the Therapeutic Community for substance abusers: A participant observation study on the treatment process. Addict Res Theory (2014) 22(3):251–62. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2013.834892

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Vanderplasschen W, Vandevelde S, Broekaert E. Therapeutic communities for treating addictions in Europe. Evidence, current practices and future challenges. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union (2014).

6. Cortini E, Clerici M, Carrà G. Is there a European approach to drug-free therapeutic communities? A narrative review. J Psychopathol (2013) 19(1):27–33.

7. De Leon G. “The Gold Standard” and related considerations for a maturing science of substance abuse treatment. Therapeutic Communities; a case in point. Subst Use Misuse (2015) 50(8-9):1106–9. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1012846

8. Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use (2005) 10(4):191–7. doi: 10.1080/14659890500114359

9. Hiebler-Ragger M, Unterrainer HF, Rinner A, Kapfhammer HP. Insecure attachment styles and increased borderline personality organization in substance use disorders. Psychopathology (2016) 49(5):341–4. doi: 10.1159/000448177

10. Unterrainer HF, Hiebler-Ragger M, Koschutnig K, Fuchshuber J, Tscheschner S, Url M, et al. Addiction as an attachment disorder: White matter impairment is linked to increased negative affective states in poly-drug use. Front Hum Neurosci (2017) 11:208(208). doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00208

11. De Leon GD, Sacks S, Staines G, McKendrick K. Modified therapeutic community for homeless mentally ill chemical abusers: treatment outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse (2000) 26(3):461–80. doi: 10.1081/ADA-100100256

12. Unterrainer HF, Lewis A, Collicutt J, Fink A. Religious/spiritual well-being, coping styles, and personality dimensions in people with substance use disorders. Int J Psychol Religion (2013) 23(3):204–13. doi: 10.1080/10508619.2012.714999

13. Orford J. Addiction as excessive appetite. Addiction (2001) 96(1):15–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961152.x

14. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision) . (2018), https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en .

15. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . (5th ed.). Author: Arlington, VA (2013).

16. Flores PJ. Addiction as an attachment disorder: Implications for group therapy. Int J Group Psychother (2001) 51(1: Special issue):63–81. doi: 10.1521/ijgp.51.1.63.49730

17. Khantzian EJ. Addiction as a self-regulation disorder and the role of self-medication. Addiction (2013) 108(4):668–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12004

18. Coan JA. Toward a neuroscience of attachment. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications , 2nd edition. London: Guildford (2008). p. 241–65.

19. Nesse RM, Berridge KC. Psychoactive drug use in evolutionary perspective. Science (1997) 278(5335):63–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.63

20. Vanderplasschen W, Colpaert K, Autrique M, Rapp RC, Pearce S, Broekaert E, et al. Therapeutic communities for addictions: a review of their effectiveness from a recovery-oriented perspective. Scientic World J (2013), 427817. doi: 10.1155/2013/427817

21. De Leon G. Therapeutic Communities. In: Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady KT, editors. The American Psychiatric Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment , 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. (2015). p. 511–30.

22. De Leon G. Community as Method: Therapeutic Communities for special populations and special settings . Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.: Westport, CT (1997).

23. Jainchill N. Therapeutic communities for adolescents: The same and not the same. In: De Leon G, editor. Community as method: Therapeutic communities for special populations and special settings . Westport: Praeger Publishers (1997). p. 161–77.

24. Jainchill N, Hawke J, Messina M. Post-Treatment Outcomes Among Adjudicated Adolescent Males and Females in Modified Therapeutic Community Treatment. Subst Use Misuse (2005) 40(7):975–96. doi: 10.1081/JA-200058857

25. Sacks S, Banks S, McKendrick K, Sacks J. Modified therapeutic community for co-occurring disorders: A summary of four studies. J Subst Abuse Treat (2008) 34(1):112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.02.008

26. Wexler HK, Prendergast ML. Therapeutic communities in United States’ prisons: Effectiveness and challenges. Ther Commun. (2010) 31:157–75.

Keywords: community as method, overview, group therapy, substance use disorder, therapeutic community

Citation: De Leon G and Unterrainer HF (2020) The Therapeutic Community: A Unique Social Psychological Approach to the Treatment of Addictions and Related Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 11:786. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00786

Received: 28 August 2019; Accepted: 22 July 2020; Published: 06 August 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 De Leon and Unterrainer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Human F. Unterrainer, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

How TCs Work

Therapeutic communities (tcs) are structured, psychologically informed environments – they are places where the social relationships, structure of the day and different activities together are all deliberately designed to help people’s health and well-being., functions of a tc, in the uk, therapeutic communities have long existed:, one way in which tcs define themselves is not by specific methods or programme elements, but the common shared values which underline all aspects of the work. the ‘community of communities’ project now works with a set of ten ‘core values’ upon which the ‘core standards’ (for measuring to what extent a programme is a tc) are based. for a tc to be accredited through this process it therefore needs to demonstrate that its work is based on the core values., therapeutic jargon, the terminology is often confusing – and there is considerable overlap between therapeutic communities and various other names, such as therapeutic environments, enabling environments, psychologically informed planned environments, intentional communities, intentional environments – and probably others. these have some, but not all the required elements of a therapeutic community. a detailed understanding of how therapeutic communities operate, and what they need to do to become accredited as tcs, can be obtained by looking at the standards set by the ‘community of communities’ project. there are many misconceptions about therapeutic communities, perhaps because of the long and complex history they have had., types of tcs, different forms of therapeutic community have evolved from various origins. one clear strand is for specific treatment of those with personality disorders. others include residential treatment of addictions, rehabilitation and offending behaviour programmes in prisons, social therapy housing for those with long term psychotic conditions, and therapeutic homes and schools for children with extreme emotional and conduct disorders. there is a long tradition of communities for people with learning disabilities which do not offer treatment but provide an alternative lifestyle choice for disabled and non disabled alike. finally, there are a small number of communites which do not specify a particular client group and which offer faith-based community living and support. the chart above represents all the tcs in the uk and estimates the percentage of tcs working with specific client groups. of these, only those designated as working with personality disorder still remain in the nhs. all offending behaviour tcs are within the prison estate. the remaining tcs are situated within the voluntary or private sector., more about tcs, often people have a number of questions about therapeutic communities. we’ve tried to answer some of them here for you..

TCs vary and it is often best to speak directly to the TC you are thinking of joining. In most cases you will need to be referred by a doctor or social worker but there are some that will take self-referrals.

In the NHS TCs working with people diagnosed with a personality disorder generally use a complex admission procedure, rather than straightforward inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This results in diagnostic heterogeneity, and none claim to treat exclusively borderline personality disorder, although recent work has demonstrated that the admission characteristics of members show high levels of personality morbidity, with most exhibiting sufficient features to diagnose more than three personality disorders, often in more than one cluster.

The admission phase includes engagement, assessment, preparation, and selection processes before the definitive therapy programme begins, and is a model of stepped care, where the service users decide when and whether to proceed to the next stage of the programme.

A voting procedure by the existing members of the community, at a specifically convened case conference or admissions panel, is normally used to admit new members.

Programmes and their various stages are time-limited, and none of the therapeutic communities specifically for personality disorder are open-ended. Some have formal or informal, staff or service-user led, post-therapy programmes.

There are various theoretical models on which the clinical practice is based, drawing on systemic, psychodynamic, group analytic, cognitive-behavioural and humanistic traditions.

The original therapeutic community model at Henderson Hospital was extensively researched in the 1950s using anthropological methods and four predominant ‘themes’ were identified: democratisation, permissiveness, reality confrontation, and communalism.

More contemporary theory emphasises the role of attachment; the ‘culture of enquiry’ within which all behaviours, thinking and emotions can be scrutinised; the network of supportive and challenging relationships between members; and the empowering potential of members being made responsible for themselves and each other. This has been synthesised into a simple developmental model of emotional development, where the task of the therapeutic community is to recreate a network of close relationships, much like a family, in which deeply ingrained behavioural patterns, negative cognitions and adverse emotions can be re-learned.

The only way to really find out, though, is to visit one – whether as somebody wanting to go through a treatment programme, as a mental health professional or a commissoner of services.

Early fore-runners of therapeutic communities, such as village communities like Geel in Flanders, existed at least as long ago as the thirteen century.

‘Mentally Afflicted Pilgrims’ (who we would probably classify as learning disabled today) went to worship at the shrine of St Dymphna there – and villagers would take long-term care of them, measuring their success by the amount of weight the pilgrims gained! Elements of this philosophy could later be seen in the work of the Quakers in founding the Retreat in York, and in the twentieth century with Steiner’s ‘anthroposophy’ and the international development of numerous Camp Hill and L’Arche communities specifically for people with learning difficulties. However, these are not normally called ‘therapeutic’ communities – but ‘intentional’ communities.

The history of children’s TCs can easily be traced back tat least as far as 1977, when Homer Lane started ‘The Boys’ Republic’ in Chicago – for wayward boys in his charge. He later set up ‘The Little Commonwealth’ in Dorset which closed in some disarray (a common pattern in the TC world). Later developments in the therapeutic childcare field were led by A S Neill who founded Summerhill in 1924, George Lyward at Finchden Manor, and people including Marjorie Franklin and David Wills with the Q-camps and Hawkspur Experiment between the World Wars. Many of the modern generation of children’s TCs are thriving by following the same treatment philosophy, but (at least in the UK) have a complex array of legislation and inspection to contend with – such as CSCI and OFSTED, as well as commissioning which demands value for money and evidence that their extra quality and costs are justified.

Those for the treatment of adult mental health ailments first emerged in a recognisable form in England during the Second World War, at Northfield Military Hospital in Birmingham and Mill Hill in London. The leaders of the Northfield “experiments” were psychoanalysts who were later involved in treatment programmes at the Tavistock Clinic and the Cassel Hospital, and had considerable international influence on psychoanalysis and group therapy. The Mill Hill programme, for battle-shocked soldiers, later led to the founding of Henderson Hospital and a worldwide “social psychiatry’ movement, which led to considerably more psychological and less custodial treatment of inmates of mental hospitals everywhere. The number of the specific TC units reached a peak in the 1970s, and fell for the following decades – although a new variant of TC, working with day treatment programmes instead of residential ones, has grown in numbers since the 1990s and is now finding a specific place in the treatment of ‘personality disorders’.

In 1958, a new kind of therapeutic community was created in America, by the forceful personality of its originator: Chuck Dederich. He started by setting up a weekly group for helping ex-AA members and ex-addicts in his own flat, based around free association, confrontational ‘reality attack’ therapy groups or ‘synanons’, and educational seminars, particularly based on philosophical ideas. This was the beginning of Synanon, and it was the first of what came to be known as ‘concept-based’, ‘hierarchical’, ‘behavioural’ or ‘programmatic’, and more recently ‘addiction’, therapeutic communities. TCs based on these ideas have spread across the globe, those in North America still adhering to many aspects of the original model – and those elsewhere more substantially modified and adapted to different cultural requirements. There have been several cross-fertilisations between the two major traditions since the early days, and this continues.

‘Democratic TCs’in custodial settings, based on the Social Psychiatry model such as in the Henderson, were first established at HMP Grendon Underwood in 1962, and several others have come and gone since. Of those that still survive, HMP Gartree established a TC wing for life sentenced prisoners in 1993, and HMP Dovegate was opened in 2001 with four TC wings for forty men each. The first women’s prison TC started in 2004 and is at HMP Send. All 14 prison TCs are now coordinated as a joint venture between the Department of Health and Ministry of Justice as part of the national programme for ‘Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder’ (DSPD). Their original work to establish humane and psychologically informed regimes within prisons, where officer and prisoners enjoyed reasonable human relationships with each other, and robust group therapy could take place within prison confines, remains largely intact – although the language now used (and throughout the prison system) is about ‘criminogenic factors’, ‘offence-related behaviour’ and ‘accredited programmes’.

Staff teams in therapeutic communities are always multidisciplinary, drawn mostly from the mental health core professions including direct psychiatric input and specialist psychotherapists.

They also frequently employ “social therapists” who are untrained staff with suitable personal characteristics, and ex-service users. The role of staff is less obvious than in single therapies, and can often cover a wide range of activities as part of the sociotherapy.

However, clear structures – such as job descriptions defining their different responsibilities, mutually agreed processes for dealing with a range of day-to-day problems, and rigorous supervisory arrangements – always underpin the various staff roles.

Frequently Asked Questions and Misconceptions

TCs did get themselves a bad name in the 1960s for being part of the antipsychiatry movement, they often attracted people who were opposed to the use of medication for mental illness and wanted to adopt more radical approaches to caring for people and allowing freedom of expression. Modern TCs are mostly staffed by fully qualified doctors, nurses, psychologists, and other mental health professionals, as well as social therapists, trainees and others. It may be true that they are more independent-minded and less willing to be told what to do without thinking about it, than staff in more structured roles. But if they did not believe in a high order of team work, and respecting people for themselves, they would not survive for long.

This is not the case, all TCs only accept people who choose to come to them and coercion is not used at any point, people always have the right to leave the TC at any time. Nearly all TCs now have professional visitors’ days, they allow others in to discuss how they are practicing, and many of them publish articles in scientific and academic journals to describe and evaluate their work. The Community of Communities sets standards for TCs and some are accredited by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

TCs have been undertaking and publishing qualitative and descriptive work since before the Second World War, and ATC is in the 29th year of publishing the ‘International Journal of Therapeutic Communities’. However, modern requirements of ‘evidence based practice’ now demand experimental quantitative designs to gain recognition, and these are fraught with problems in systems as complex as TCs. However, there is a substantial body of other types of outcome research showing positive results, and high quality randomised trials are being planned.

TCs do have rituals, and some are concerned with joining, but if their intention was to humiliate – or if humiliation was inadvertently allowed to happen – they would not meet standards required of staff sensitivity, training or supervision. Members often do reveal painful and intimate details about their lives, but only when they have established enough trust to be able to do so safely. However, some of the original ‘Concept TC’ practices were very confrontative and possibly humiliating, but these were large American TCs for treating addicts, and modern practice has moved on a long way.

In most TCs, there is a ‘no harm to others’ rule in place – and it is very unusual for it to be broken. All forms of self-harm are also strongly discouraged and people for whom it has been a problem usually do it much less when in a TC. Rigorous research has shown that prison TCs have much lower occurrence of violent incidents than other prison wings. Any unacceptable behaviour is soon challenged by somebody’s peers, and learning about ‘boundaries’ of what is respectful to others is often a major part of the work.

Many TCs are still residential but is becoming less so in the NHS. Tighter economic times have meant that many TCs now operate a Day TC model (meeting for three or more days per week), or even a Mini TC model (meeting for less than three days per week). Although this might not be safe enough for some who do need the full intensity of a residential programme, it has the advantage of being better integrated into somebody’s ‘normal life’.

People who have been in TCs would strongly disagree! Common things said about being in a therapeutic community are ‘There’s no place to hide’; ‘I go home utterly exhausted every day and just collapse’ and ‘It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done’. If TCs were physical activities instead of emotional and mental, it would be the equivalent of being in a gym for several hours every day. And physical activities, such as playful team sport, horticulture, and walks, are often part of the programmes, although less so for the day programmes in urban areas which do not have access to the space for them.

Subscribe to our Mailing List

Stay up to date and informed by subscribing to our mailing list. you will receive tc news, updates and info about our events..

The Consortium for Therapeutic Communities, 34 Carlton Business Centre, Carlton, Nottingham, NG4 3AA

Company number 7710339 & Registered Charity Number 1143955

Useful Links

If you would like to get in touch, please see the contact details.

© 2022, Website Created Best City Services . All Rights Reserved.

COMMENTS

In the USA, the term ‘therapeutic community’ is more often used to describe user-run communities for substance misusers with: a hierarchical structure; a reward system; fierce encounter groups; and a simple explanatory model of addiction and its treatment.

A therapeutic community (TC) is a highly organized and closely monitored environment for the treatment of people with substance use, mental health, or behavioral issues.

Outside the United States, the therapeutic community (TC) model is widely embraced, with currently 65 countries offering treatments and over 3,000 TC models incorporated into community...

This paper gives an outline of four research areas examining therapeutic community practice: an international systematic review, health economics cost-offset work, a cross-institutional multi-level modelling outcome study and a proposed action research project to deliver continuous quality improvement in all British therapeutic communities.

The evolution of the contemporary Therapeutic Community (TC) for addictions over the past 50 years may be characterized as a movement from the marginal to the mainstream of substance abuse treatment and human services.

The evolution of the contemporary Therapeutic Community (TC) for addictions over the past 50 years may be characterized as a movement from the marginal to the mainstream of substance abuse treatment and human services.

Therapeutic Communities (TCs) are structured, psychologically informed environments – they are places where the social relationships, structure of the day and different activities together are all deliberately designed to help people’s health and well-being.

Therapeutic community is a participative, group-based approach to long-term mental illness, personality disorders and drug addiction. The approach was usually residential, with the clients and therapists living together, but increasingly residential units have been superseded by day units.

The last twenty years have seen the rise and dominance in institutional psychiatry of a remarkable notion—“the therapeutic Community”. It is both an attitude and a method, a system of treatment and a battle cry, a charm and a password.

This paper reviews the place of the therapeutic community in the mental health field, using a sociological framework to understand some key factors that have shaped the field and its response to this approach to therapy.