- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Banned and Challenged: Restricting access to books in the U.S.

Perspective, ashley hope pérez: 'young people have a right' to stories that help them learn.

Ashley Hope Pérez

Author Ashley Hope Pérez wrote Out of Darkness, which is on the American Library Association's lists of most banned books. Kaz Fantone/NPR hide caption

Author Ashley Hope Pérez wrote Out of Darkness, which is on the American Library Association's lists of most banned books.

This essay by Ashley Hope Pérez is part of a series of interviews with — and essays by — authors who are finding their books being challenged and banned in the U.S.

For over a decade, I lived my professional dream. I spent my days teaching college literature courses and writing novels. I regularly visited schools as an author and got to meet teens who reminded me of the students I taught in Houston — the amazing humans who had first inspired me to write for young adults.

Then in 2021, my dream disintegrated into an author and educator's nightmare as my novel Out of Darkness became a target for politically motivated book bans across the country.

Book News & Features

Efforts to ban books jumped an 'unprecedented' four-fold in 2021, ala report says.

Author Interviews

Banned books: author ashley hope pérez on finding humanity in the 'darkness'.

Attacks unfolded, not just on my writing but also on young people's right to read it. Hate mail and threats overwhelmed the inboxes where I once had received invitations for author visits and appreciative notes from readers. At the beginning of 2021, Out of Darkness had been on library shelves for over five years without a single challenge or complaint. As we reach the end of 2022, it has been banned in at least 29 school districts across the country.

From the earliest stages of writing, I knew Out of Darkness would be difficult — for me, and for readers. I drew my inspiration for the novel from an actual school disaster: the 1937 New London school explosion that killed hundreds in an East Texas oil town just 20 minutes from my childhood home. This tragic but little-known historical event serves as the backdrop for a fictional star-crossed romance between a Black teenager and a young Latina who has just arrived in the area.

As I researched the novel, I imagined the explosion as its most devastating event. But to engage honestly with the realities of the time and of my characters' lives, I had to grapple with systemic racism, personal prejudice, sexual abuse and domestic violence. As I wrote, the teenagers' circumstances began to tighten, noose-like, around their lives and love, leading to still more tragedy. I sought to show the depths of harm inflicted on some in this country without sensationalizing that history. The book portrays friendship, loving family, community and healthy relationships because they, too, are part of the characters' world. Then, as now, young people struggle mightily for joy, love and dignity.

When Out of Darkness was first published, I braced for objections. Would readers recoil from the harshness of my characters' realities? Or would they recognize how the novel invites connections between those realities and an ongoing reckoning with racialized violence and police brutality? To my relief, the novel received glowing reviews, earned multiple literary awards, and was named to "best of the year" lists by Kirkus Reviews and School Library Journal . It appeared on reading lists across the country as a recommendation for ambitious young readers ready to face disquieting aspects of the American experience.

So it went until early 2021. In the wake of the 2020 presidential elections, right-wing groups pivoted from a national defeat to "local" issues. The latest wave of book banning exceeds anything ever documented by librarian or free-speech groups. The statistics for 2021, which represent only a fraction of actual removals, reflect a more than 600% increase in challenges and removals as compared to 2020. (See Everylibrary.org for a continually updated database of challenges and bans and PEN America's Banned in the USA reports for April 2022 and September 2022 for further context.)

These book bans do not reflect spontaneous parental concern. Instead, they are part of an orchestrated effort to sow suspicion of public schools as scarily "woke" and to signal opposition to certain identities and topics. Book banners often cite "sexually explicit content" as their reason for objecting to books in high schools. What distinguishes the targeted titles, though, is not their sexual content but that they overwhelmingly center the experiences of BIPOC, LGBTQ+ and other marginalized people. If you were to stack up all the books with sexual content in any library, the tallest stack by far would be about white, straight characters. Tellingly, those are not the books under attack. Claims about "sexual content" are a pretext for erasing the stories that tell Black, Latinx, queer and other non-dominant kids that they matter and belong. Beyond telegraphing disapproval, book bans serve the interests of groups that have long sought to dismantle public education and shut down conversations about important issues.

Debates about the suitability of reading materials in school are nothing new. These include past efforts by progressives to reorient language arts instruction. Concerns about racist language and portrayals might well lead communities to seek alternatives to the teaching of works like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn . But de-emphasizing problematic classics does not generally entail removing the books from library collections. By contrast, in targeting high school libraries, conservative book banners seek to restrict what individual students may choose to read on their own , disregarding the judgment of school librarians who carefully select materials according to professional standards.

Rather than reading the books themselves, today's book banners rely instead on haphazard lists and talking points circulated online. Social media plays a central role in stoking the fires of censorship. Last year, a video of a woman ranting about a passage from Out of Darkness in a school board meeting went internationally viral. The woman's school board rant resulted in the removal of every copy of Out of Darkness from the district's libraries, triggered copycat performances, and fueled more efforts to ban my book.

Book banning poses a real professional and personal cost to authors and educators. For YA writers, losing access to school and library audiences can be career ending. And it is excruciating to watch people describe our life's work as "filth" or "garbage." We try to find creative ways to respond to the defamation, as I did in my own YouTube video . But there is no competing with the virality of outrage. Meanwhile, librarians and teachers face toxic work conditions that shift the focus from student learning to coping with harassment.

But book banning harms students, and their education, the most. Young people rely on school libraries for accurate information and for stories that broaden their understanding, offer hope and community, and speak honestly to challenges they face. As libraries become battlegrounds, teens notice which books, and which identities, are under attack. Those who share identities with targeted authors or characters receive a powerful message of exclusion: These books don't belong, and neither do you.

Back in 2004, my predominately Latinx high school students in Houston wanted — needed — books that reflected their lives and communities but few such books had been written. In the decades since, authors have worked hard to ensure greater inclusion and respect for the diversity of teen experiences. For students with fewer resources or difficult home situations, though, a book that isn't in the school library might as well not exist. Right-wing groups want to roll back the modest progress we've made, and they are winning.

These "wins" happen even without official bans. Formal censorship becomes unnecessary once bullying, threats and disruption shake educators' focus from students. The result is soft censorship . For example, a librarian reads an outstanding review of a book that would serve someone in their school, but they don't order it out of fear of controversy. This is the internalization of the banners' agenda. The effects of soft censorship are pervasive, pernicious and very difficult to document.

The needs of all students matter, not just those whose lives and identities line up with what book banners think is acceptable. Young people have a right to the resources and stories that help them mature, learn and understand their world in all its diversity. They need more opportunities, not fewer, to experience deep imaginative engagement and the empathy it inspires. We've had enough "banner" years. I hope 2023 returns the focus to young people and their right to read.

Ashley Hope Pérez, author of three novels for young adults, is a former high school English teacher and an assistant professor in the Department of Comparative Studies at The Ohio State University. Find her on Twitter and Instagram or LinkT .

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Banned Books — Banned Books and the Freedom of Expression

Banned Books and The Freedom of Expression

- Categories: Banned Books Freedom of Expression

About this sample

Words: 793 |

Published: Sep 16, 2023

Words: 793 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The phenomenon of banned books, the implications of banned books, the paradox of banned books, the enduring value of intellectual freedom, conclusion: the unbreakable bond between books and freedom, 1. offensive content:, 2. political or ideological concerns:, 3. religious sensitivities:, 4. social justice and controversial themes:, 5. protecting children:, 1. suppression of free expression:, 2. preservation of ignorance:, 3. cultural impact:, 4. loss of artistic and literary value:.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1347 words

3.5 pages / 1598 words

2.5 pages / 1232 words

2 pages / 1005 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Banned Books

Go Ask Alice by Beatrice Sparks is a controversial book that has faced challenges and bans in various schools and libraries across the United States. The book, written in the form of a diary, chronicles the life of a teenage [...]

What do you think of when you hear the word library? Is a library a large repository of books? Is a library a place where students can access computers and other equipment? Is a library a quiet place where one can lose [...]

"The Giver" by Lois Lowry has been a controversial book since its publication in 1993, sparking debates about censorship, freedom of expression, and the role of literature in society. In this essay, we will explore the banning [...]

Books have long held the power to inspire, educate, and challenge our perspectives. However, this very power often sparks controversy and leads to some books being banned or challenged. In this essay, we will delve into the [...]

Throughout history, the suppression of knowledge through banning or destroying books has been seen at some point in most modern societies. The reason as to why books are banned varies from different governments and their [...]

In the play “An Inspector Calls” by J B Priestley, the characters of Sheila and Eric are used to represent the younger generation in Edwardian England, a time when traditional Victorian values were beginning to become obsolete. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Book Banning Efforts Surged in 2021. These Titles Were the Most Targeted.

Most of the targeted books are about Black and L.G.B.T.Q. people, according to the American Library Association. The country’s polarized politics has fueled the rise.

By Elizabeth A. Harris and Alexandra Alter

Attempts to ban books in the United States surged in 2021 to the highest level since the American Library Association began tracking book challenges 20 years ago, the organization said Monday.

Most of the targeted books were by or about Black and L.G.B.T.Q. people, the association said.

Book challenges are a perennial issue at school board meetings and libraries. But more recently, efforts fueled by the country’s intensely polarized political environment have been amplified by social media, where lists of books some consider to be inappropriate for children circulate quickly and widely.

Challenges to certain titles have been embraced by some conservative politicians, cast as an issue of parental choice and parental rights. Those who oppose these efforts, however, say that prohibiting the books violates the rights of parents and children who want those titles to be available.

“What we’re seeing right now is an unprecedented campaign to remove books from school libraries but also public libraries that deal with the lives and experience of people from marginalized communities,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the American Library Association’s office for intellectual freedom. “We’re seeing organized groups go to school boards and library boards and demand actual censorship of these books in order to conform to their moral or political views.”

The library association said it counted 729 challenges last year to library, school and university materials, as well as research databases and e-book platforms. Each challenge can contain multiple titles, and the association tracked 1,597 individual books that were either challenged or removed.

The count is based on voluntary reporting by educators and librarians and on media reports, the association said, and is not comprehensive.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools

Key findings.

More books banned.

More districts.

More states.

More students losing access to literature.

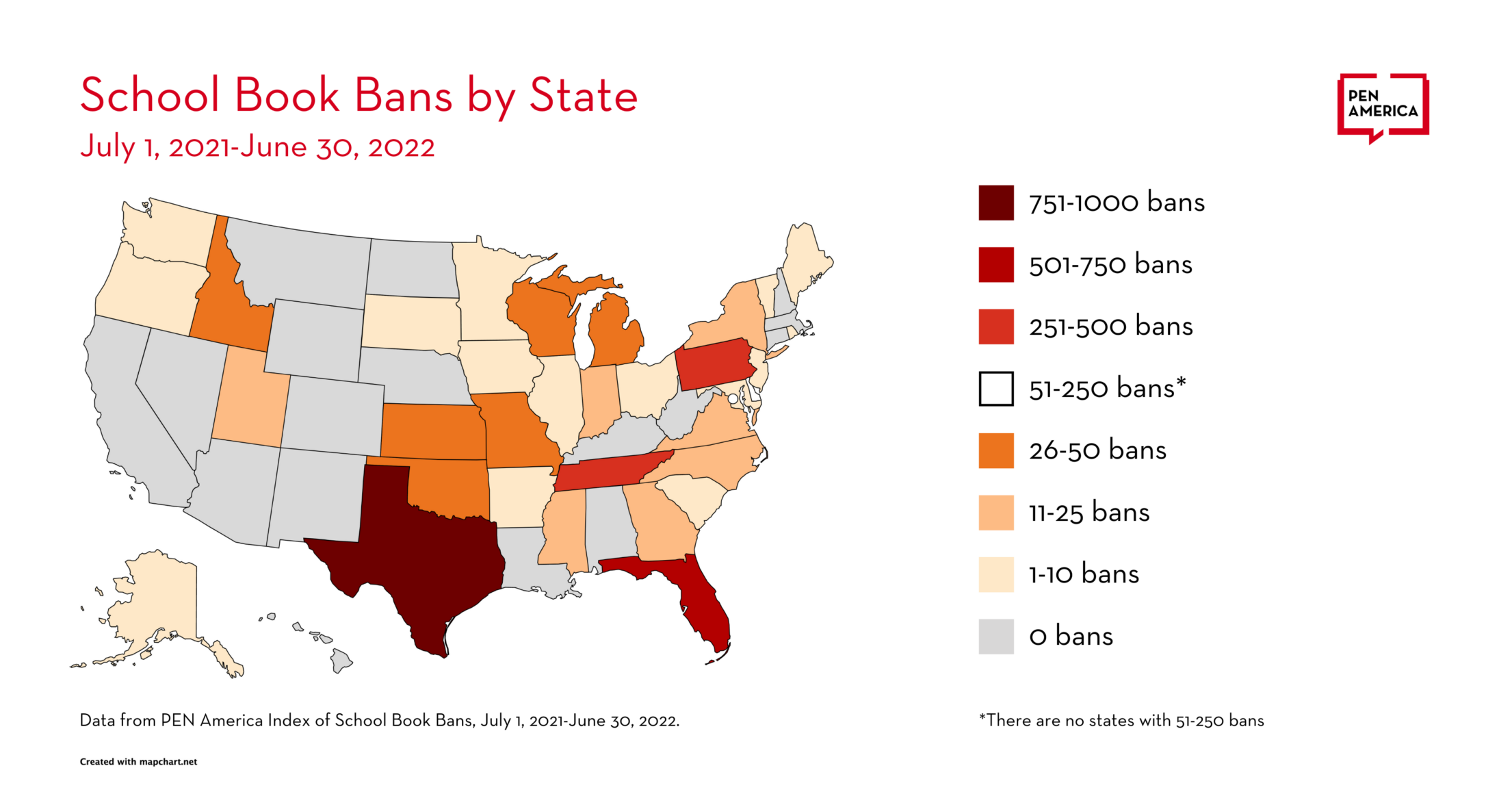

“More” is the operative word for this report on school book bans, which offers the first comprehensive look at banned books throughout the 2021–22 school year. This report offers an update on the count in PEN America’s previous report, Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights (April 2022) , which covered the first nine months of the school year (July 2021 to March 2022). It also sheds light on the role of organized efforts to drive many of the bans.

Many Americans may conceive of challenges to books in schools in terms of reactive parents, or those simply concerned after thumbing through a paperback in their child’s knapsack or hearing a surprising question about a novel raised by their child at the dinner table. However, the large majority of book bans underway today are not spontaneous, organic expressions of citizen concern. Rather, they reflect the work of a growing number of advocacy organizations that have made demanding censorship of certain books and ideas in schools part of their mission.

Banned Book Data Snapshot

- From July 2021 to June 2022, PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans lists 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique book titles.

- The 1,648 titles are by 1,261 different authors, 290 illustrators, and 18 translators, impacting the literary, scholarly, and creative work of 1,553 people altogether.

The numbers in this report represent documented cases of book bans reported directly to PEN America and/or covered in the media; there are likely additional bans that have not been reported. 1 In August, the Houston Chronicle released a report on the partisan nature of book bans in Texas between 2018 and 2021. The newspaper reported finding more than 1,000 bans in Texas during that time frame, which overlaps only in part with the time period covered by this report. That data was not available to review for inclusion in this report in advance of publication.

- Bans occurred in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts represent 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students.

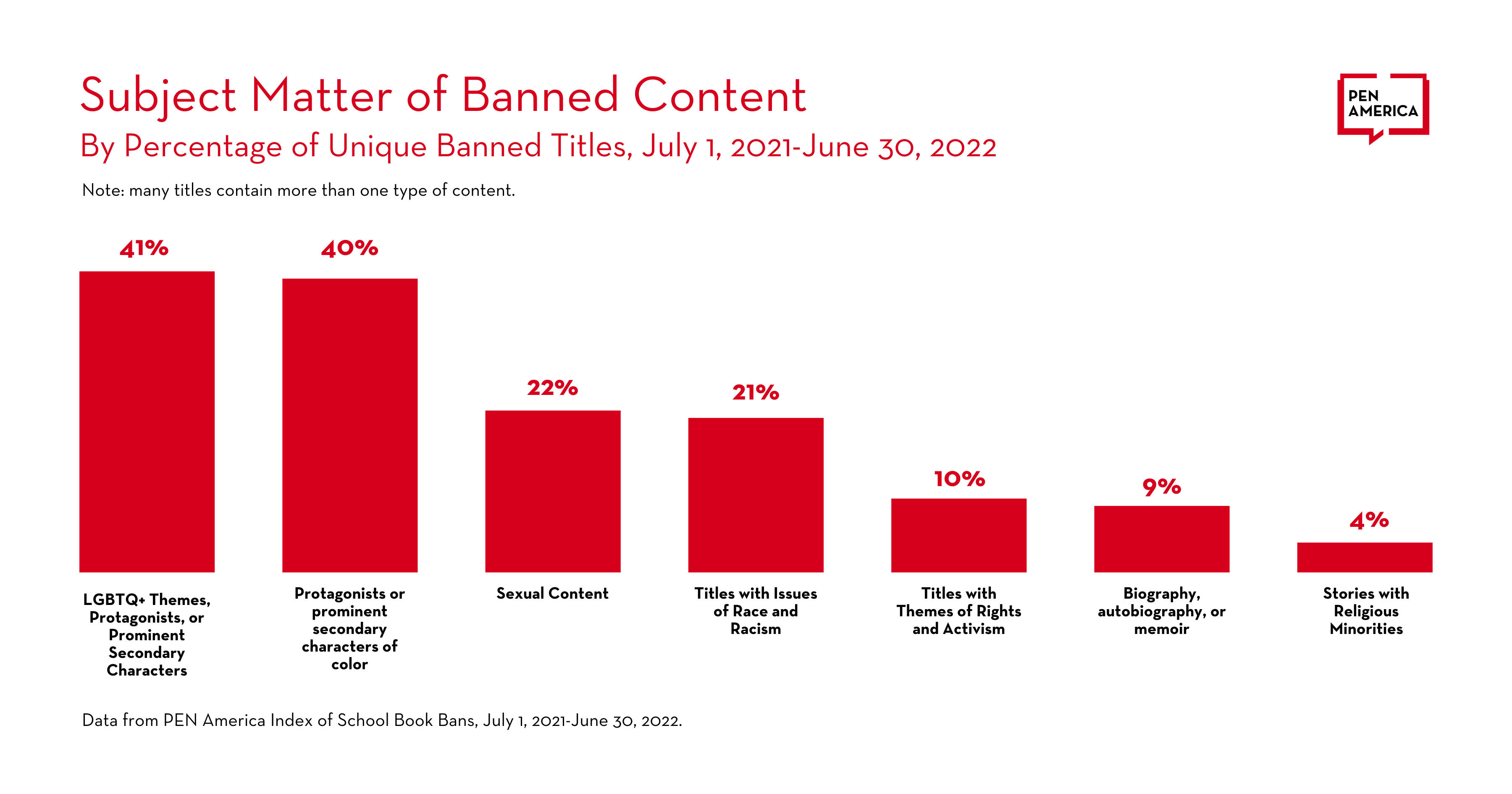

- 674 banned book titles (41 percent) explicitly address LGBTQ+ themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ+ (this includes a specific subset of titles for transgender characters or stories—145 titles, or 9 percent);

- 659 banned book titles (40 percent) contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color;

- 338 banned book titles (21 percent) directly address issues of race and racism;

- 357 banned book titles (22 percent) contain sexual content of varying kinds, including novels with some level of description of sexual experiences of teenagers, stories about teen pregnancy, sexual assault and abortion as well as informational books about puberty, sex, or relationships;

- 161 banned book titles (10 percent) have themes related to rights and activism;

- 141 banned book titles (9 percent) are either biography, autobiography, or memoir; and

- 64 banned book titles (4 percent) include characters and stories that reflect religious minorities, such as Jewish, Muslim and other faith traditions.

PEN America estimates that at least 40 percent of bans listed in the Index (1,109 bans) are connected to either proposed or enacted legislation, or to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers to restrict the teaching or presence of certain books or concepts.

PEN America has identified at least 50 groups involved in pushing for book bans across the country operating at the national, state or local levels. Of those 50 groups, eight have local or regional chapters that, between them, number at least 300 in total; some of these operate predominantly through social media. Most of these groups (including chapters) appear to have formed since 2021 (73 percent, or 262). These parent and community groups have played a role in at least half of the book bans enacted across the country during the 2021–22 school year. At least 20 percent of the book bans enacted in the 2021-22 school year could be directly linked to the actions of these groups, with many more likely influenced by them; in an additional approximately 30 percent of bans, there is some evidence of the groups’ likely influence, including the use of common language or tactics.

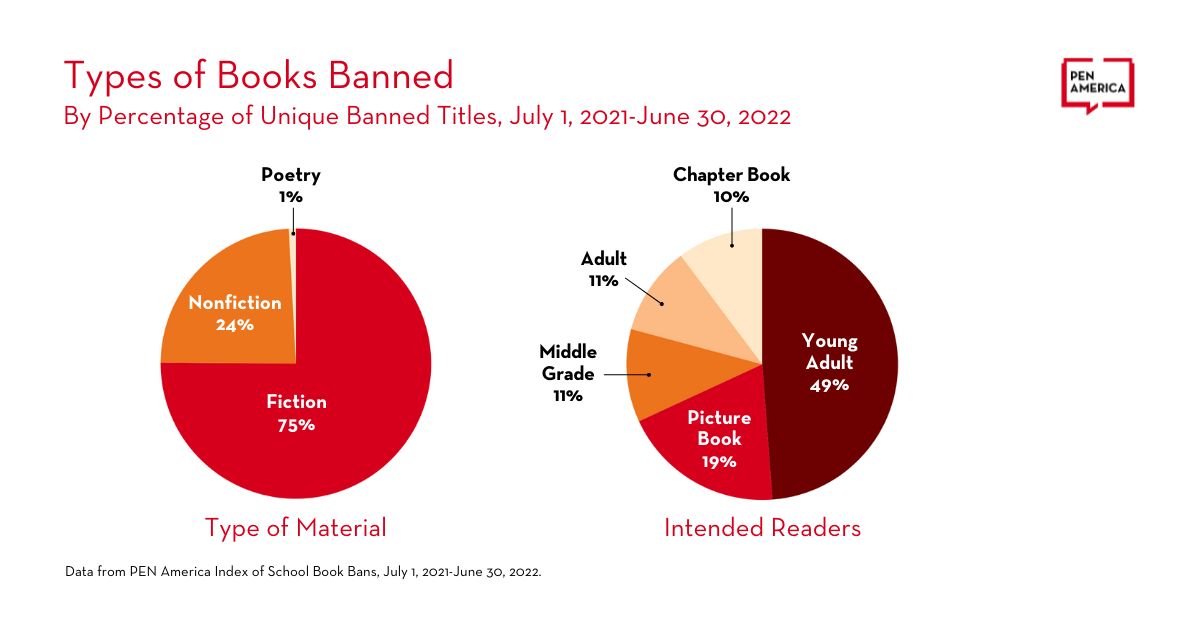

- Nearly half of the unique titles of banned books were young adult books, but bans also affected many books for younger readers, including 317 picture books and 168 chapter books.

- Of the 2,532 bans listed in the Index, 96 percent were enacted without following the best practice guidelines for book challenges outlined by the American Library Association (ALA) and the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC).

Introduction

Over the 2021–22 school year, what started as modest school-level activity to challenge and remove books in schools grew into a full-fledged social and political movement, powered by local, state, and national groups. The vast majority of the books targeted by these groups for removal feature LGBTQ+ characters or characters of color, and/or cover race and racism in American history, LGBTQ+ identities, or sex education.

This movement to ban books is deeply undemocratic, in that it often seeks to impose restrictions on all students and families based on the preferences of those calling for the bans and notwithstanding polls that consistently show that Americans of all political persuasions oppose book bans . And it is having multifaceted, harmful impacts: on students who have a right to access a diverse range of stories and perspectives, and especially on those from historically marginalized backgrounds who are watching their library shelves emptied of books that reflect and speak to them; on educators and librarians who are operating in some states in an increasingly punitive and surveillance-oriented environment with a chilling effect on teaching and learning; on the authors whose works are being targeted; and on parents who want to raise students in schools that remain open to curiosity, discovery, and the freedom to read.

PEN America has identified at least 50 groups involved in pushing for book bans at the national, state, or local levels. This includes eight groups that have among them at least 300 local or regional chapters. PEN America has identified these chapters based on the national groups’ own listings, by chapter or regional websites, and by their official chapter and regional group pages on Facebook. Insofar as we have been able to establish, there are at least another 38 state, regional, or community groups that do not appear to have formal affiliations with national organizations or with one another.

These groups share lists of books to challenge, and they employ tactics such as swarming school board meetings, demanding newfangled rating systems for libraries, using inflammatory language about “grooming” and “pornography,” and even filing criminal complaints against school officials, teachers, and librarians. The majority of these groups appear to have formed in 2021, and many of the banned books counted by PEN America can be linked in some way to their activities. Some of the groups espouse Christian nationalist political views, while many have mission statements oriented toward reforming public schools, in some cases to offer more religious education. In at least a few documented cases (for example, in Texas , Florida , and Pennsylvania ), the individuals lodging complaints about books did not have children attending public schools when at the time they raised objections.

This evolving censorship movement has grown in size and routinely finds new targets and tactics, homing in on the books encompassed in district book purchases or digital library apps . A parallel but connected movement is also targeting public libraries , with calls to ban books; efforts to intimidate, harass , or fire librarians ; and even attempts to suspend or defund entire libraries.

| PEN America defines a school book ban as any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students, or where access to a book is restricted or diminished. It is important to recognize that books available in schools, whether in a school or classroom library, or as part of a curriculum, were by librarians and educators as part of the educational offerings to students. Book bans occur when those choices are overridden by school boards, administrators, teachers, or even politicians, on the basis of a particular book’s content. School book bans take varied forms, and can include prohibitions on books in libraries or classrooms, as well as a range of other restrictions, some of which may be temporary. Book removals that follow established processes may still improperly target books on the basis of content pertaining to race, gender, or sexual orientation, invoking concerns of equal protection in education. For more details, please see the first edition of .

|

Since PEN America published our initial Banned in the USA: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights (April 2022) report, tracking 1,586 book bans during the nine-month period from July 2021 to March 2022, details about 671 additional banned books during that period have come to light. A further 275 more banned books followed from April through June, bringing the total for the 2021-22 school year to 2,532 bans. This book-banning effort is continuing as the 2022–23 school year begins too, with at least 139 additional bans taking effect since July 2022.

In addition to the role played in book banning by local, state, and national groups, efforts to restrict access to books were also advanced in the past year by government officials and enabled by both state-level legislation and district-level policy changes. PEN America estimates that at least 40 percent of the bans counted in the Index of School Book Bans for the 2021–22 school year are connected to political pressure exerted by state officials or elected lawmakers. Some officials for example sent letters specifically inquiring into the availability of certain books in schools, such as occurred in Texas , Wisconsin , and South Carolina .

Since March 2022, we have also seen for the first time educational gag orders passed that implicate restrictions on books, most notably in Florida , as well as a range of other new laws that have put pressure on schools to censor their libraries. The Alpine School District in Utah responded to a new law, HB 374 (“ Sensitive Materials in Schools ”) , by announcing the removal of 52 titles in July, but then opted to keep the books on shelves with some restrictions after national pushback. In August, some school districts in St. Louis, Missouri began to pull books from shelves in response to a law that made it a class A misdemeanor to provide visually explicit sexual material to students. These trends are unfortunately likely to continue, as the chilling effect of these legislative measures spreads.

Altogether, this report paints a deeply concerning picture for access to literature, and diverse literature in particular, in schools in the coming school year. Book banning and educational gag orders are two fronts in an all-out war on education and the open discussion and debate of ideas in America. Students have First Amendment rights to access information and ideas in schools, and these bans and legislative shifts pose clear threats to those rights. This climate is also increasingly undermining the professional discretion of educators and librarians when it comes to matters of public education, and disrupting the potential for effective relationships between parents, teachers and administrators that can actually serve to advance student learning and civic engagement.

| Students retain their First Amendment rights in schools. In , a 1969 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Thirteen years later, in , the Court noted the “special characteristics” of the school library, making it “especially appropriate for the recognition of the First Amendment rights of students,” including the right to access information and ideas. What does this mean for districts who receive a request to reconsider a library holding? Legal precedent and expert best practices demand that committee members, and principals, superintendents, and school boards act with the constitutional rights of students in mind, and using established processes, cognizant of the harm in eliminating access for all based on the concerns of any individual or faction. What if a book is obscene? The term “obscenity” holds particular meaning in the legal sense. Obscene material is not protected under the First Amendment, but a finding of obscenity requires satisfaction of a tripartite test, which requires, among other aspects, a holistic consideration of the material at issue. Simply declaring a book “obscene” does not make it so.

|

PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel on book bans for PBS NewsHour, March 10, 2022.

What Types of Book Bans Are Taking Place in Schools?

In total, PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans tracked 2,532 decisions to ban books between July 1, 2021, and June 30, 2022. This includes bans on 1,648 unique banned book titles. The banning of a single book title could mean anywhere from one to hundreds of copies are pulled from libraries or classrooms in a school district, and often, the same title is banned in libraries, classrooms, or both in a district. PEN America does not count these duplicate book bans in its unique title tally, but does acknowledge each separate ban in its overall count.

In some cases, books are removed from shelves pending investigations or reviews, and they may be only temporarily restricted, but their restriction is recorded in the Index as a ban since such restrictions are counter to procedural best practices for book challenges from the American Library Association (ALA) and the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC). Detailed definitions can be found in the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022) .

PEN America’s recent findings on each type of ban for the 2021-22 school year are listed below.

| 333 | 215 | 70 | |

| 337 | 253 | 40 | |

| 487 | 481 | 22 | |

| 1,375 | 984 | 57 |

What Types of Content Are Being Banned?

Beginning in 2021, a range of individuals and groups sought to remove from schools books focused on issues of race or the history of slavery and racism, mirroring a campaign pushed by some legislators to pass educational gag orders —bills restricting discussion of these and other concepts in school classrooms and curricula. Although the campaign to enact educational gag orders initially focused on misapplications of the academic term “critical race theory” to censor discussions of race and racism, over the past year, it morphed to include a heightened focus on LGBTQ+ issues and identities.

Similar trends — and similar rhetoric and reasoning — have been evident in efforts to ban books in schools as they have expanded since 2021, too.

Complaints about diversity and inclusion efforts have accompanied calls to remove books with protagonists of color, and numerous banned books have been targeted for simply featuring LGBTQ+ characters. Nonfiction histories of civil rights movements and biographies of people of color have been swept up in these campaigns. For example, many volumes in the popular Who Was? chapter book series and several biographies of Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor were banned in Central York School District in Pennsylvania . That ban also impacted hundreds of books with protagonists of color, including the Caldecott Honor–winning A Big Mooncake for Little Star . In a similar example, Duval County Public Schools in Florida opted not to distribute sets of the Essential Voices Classroom Libraries collection of books after they had been purchased, flagged for concern over their content. This collection of 176 unique titles has been effectively banned from classrooms while it is being reviewed and reportedly remains in storage. Books in the collection include Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story by Kevin Noble Maillard, Dim Sum for Everyone by Grace Lin, and Pink Is For Boys by Robb Perlman, among other titles designed to make classroom libraries more diverse and inclusive.

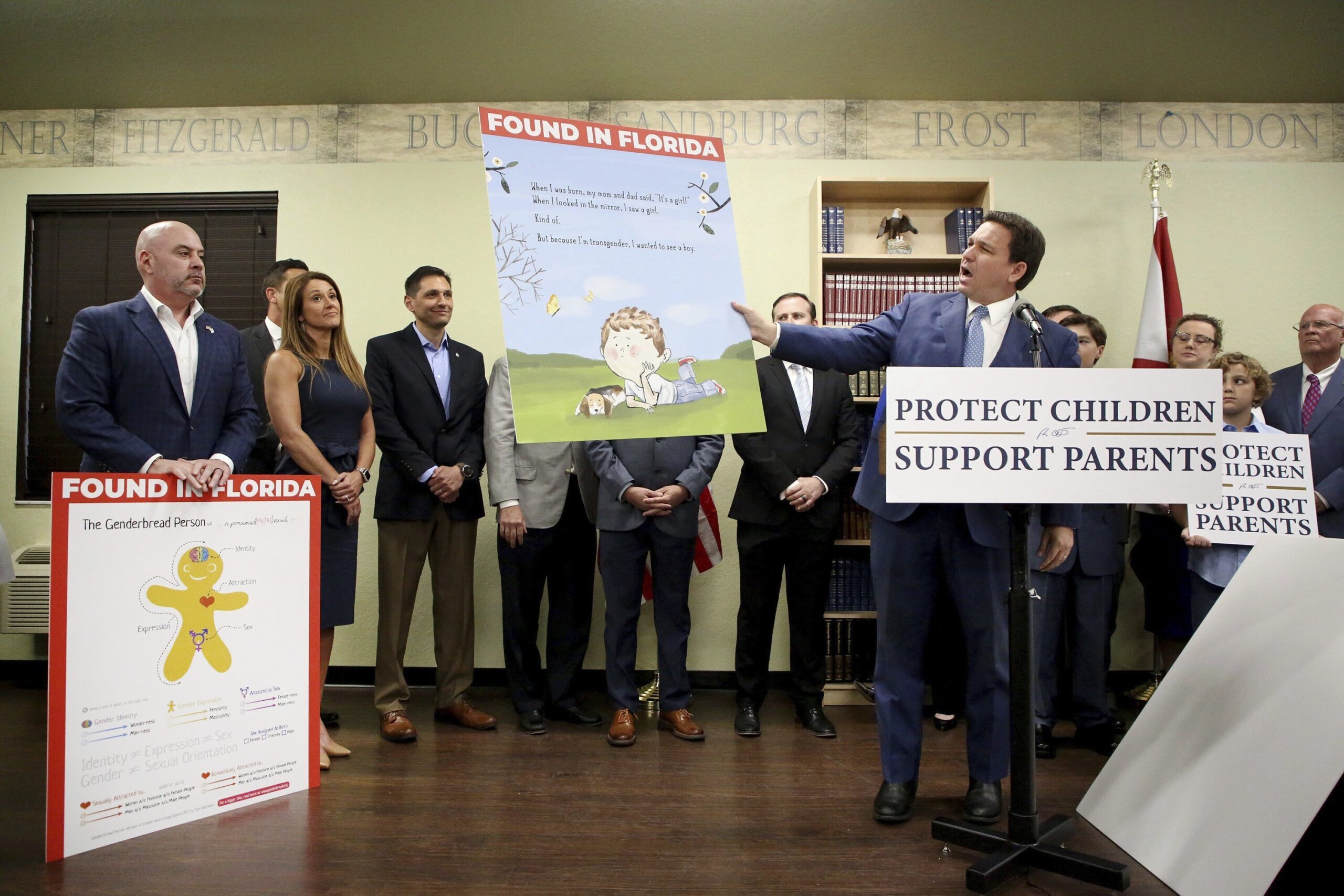

As the school year progressed, those demanding book removals increasingly turned their attention to books that depict LGBTQ+ individuals or touch on LGBTQ+ identities, as well as books they claimed featured “sexual” content, including titles on sexual and reproductive health and sex education. These trends were already identified in PEN America’s first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022) report; however, from April to June, there was an acute focus on these topics. This dovetailed with the passage in late March of the “ Parental Rights in Education ” law in Florida—also known as the “Don’t Say Gay” law—and the introduction of similar legislation in other states, as well as a range of efforts to censor discussion of LGBTQ+ identities in schools, in Maryland , Missouri , Texas , and beyond. From April to June 2022, a third of all book bans recorded in the Index feature LGBTQ+ identities (92 bans). Over the same short period, nearly two thirds of all banned books in the Index touch on topics related to sexual content, such as teen pregnancy, sexual assault, abortion, sexual health, and puberty (161 bans).

These subject areas have long been the targets of censorship and been controversial from the perspective of age appropriateness, with standards and approaches varying from community to community about what is seen as the right age level for such material, as well as the degree to which these topics should be addressed in school as opposed to in the home. As book banning has resurged, some individuals and groups have sought to reignite debate about sexual content in books, and sexual education in schools generally. While debate on these issues recurs, wholesale bans on books deny young people the opportunity to learn, to get answers to pressing questions, and to obtain crucial information. At the same time, the efforts to target books containing LGBTQ+ characters or themes are frequently drawing on long-standing, denigrating stereotypes that suggest LGBTQ+ content is inherently sexual or pornographic.

PEN America’s Jonathan Friedman on MSNBC for the Mehdi Hasan Show, Nov. 11, 2021.

Many of the books targeted for banning have been labeled “obscene.” These complaints are not supported. The legal test for obscenity requires a holistic evaluation of the material, setting a bar that is highly unlikely to be met by materials selected for inclusion in a school library. Many targeted books have achieved bestseller status or received the highest literary honors. Some contain nothing more “obscene” than the mere suggestion of a same-sex couple in an illustration, as in the board book Everywhere Babies , which was included on one list of books misleadingly labeled “pornographic” along with And Tango Makes Three , a story about two male penguins making a family together, based on the true story of two male penguins who formed a pair bond in New York’s Central Park Zoo. The most frequently banned book, Gender Queer , has been called “obscene and pornographic” by the groups who lobby for its removal, as have dozens of books with LGBTQ+ themes or characters.

In these cases, the term “obscenity” is being stretched in unrecognizable ways because the concept itself is widely accepted as grounds for limiting access to content. But many of the materials now being removed under the guise of obscenity bear no relation to the sexually explicit, deliberately evocative content that the term has historically connoted.

In evaluating these trends, it is critical to remember that only a limited number of children’s and young adult books are published annually that are written by or about either LGBTQ+ people or people of color. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the School of Education, University of Wisconsin–Madison, has compiled statistics on diversity in children’s literature since 1985. In its 2021 report , the center states that of the 3,420 books received at the institution in 2021, 1,152 titles were “books by and about Black, Indigenous and People of Color” (34 percent). Although the center does not continuously maintain similar statistics on books about LGBTQ+ characters or plots, such books have not historically been published in great abundance . The targeting of these books in schools reflects a disproportionate focus on what is likely a small fraction of holdings in most public school libraries.

Over the 2021–22 school year, PEN America also tracked efforts to ban not only books, but also whole academic courses, textbooks, and digital literacy apps. In Bossier Parish, Louisiana , the Epic reading app was removed from student iPads after parent objections about the inclusion of LGBTQ+ content. The school district in Brevard County, Florida , canceled its math app, Prodigy, for similar reasons. Along with educational gag orders targeting classroom discussions, efforts to censor and control public education are ranging beyond the physical collections of school libraries.

The Most Banned Titles in the 2021–22 School Year

The most banned book titles include the groundbreaking work of Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, along with best-selling books that have inspired feature films, television series, and a Broadway show. The list includes books that have been targeted for their LGBTQ+ content, their content related to race and racism, or their sexual content—or all three.

- Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe (41 districts)

- All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson (29 districts)

- Out of Darkness by Ashley Hope Pérez (24 districts)

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison (22 districts)

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (17 districts)

- Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison (17 districts)

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie (16 districts)

- Me and Earl and the Dying Girl by Jesse Andrews (14 districts)

- Crank by Ellen Hopkins (12 districts)

- The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini (12 districts)

- l8r, g8r by Lauren Myracle (12 districts)

- Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher (12 districts)

- Beloved by Toni Morrison (11 districts)

- Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin (11 districts)

- Drama: A Graphic Novel by Raina Telgemeier (11 districts)

- Looking for Alaska by John Green (11 districts)

- Melissa by Alex Gino (11 districts)

- This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson (11 districts)

- This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (11 districts)

The Most Frequently Banned Authors

The most banned authors include winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature, the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the Booker Prize, the Newbery Award, the Caldecott Medal, the Eisner Award, the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the NAACP Image Award, the GLAAD Award for Media Representation, the Stonewall Award, and more.

- Hopkins, Ellen – 14 titles – 43 bans – 20 districts

- Kobabe, Maia – 1 title – 41 bans – 41 districts

- Morrison, Toni – 3 titles – 34 bans – 25 districts

- Johnson, George M. – 2 titles – 30 bans – 29 districts

- Myracle, Lauren – 11 titles – 30 bans – 16 districts

- Pérez, Ashley Hope – 1 title – 23 bans – 23 districts

- Thomas, Angie – 2 titles – 19 bans – 17 districts

- Silvera, Adam – 9 titles – 18 bans – 13 districts

- Reynolds, Jason – 6 titles – 18 bans – 11 districts

- Maas, Sarah J. – 8 titles – 18 bans – 10 districts

- Levithan, David – 15 titles – 17 bans – 18 districts

- Alexie, Sherman – 2 titles – 17 bans – 17 districts

- Evison, Jonathan – 1 title – 17 bans – 17 districts

- Andrews, Jesse – 2 titles – 17 bans – 16 districts

- Faruqi, Saadia – 17 titles – 17 bans – 2 districts

- Jules, Jacqueline – 17 titles – 17 bans – 2 districts

- Do, Anh – 17 titles – 17 bans – 1 district

- Green, John – 3 titles – 16 bans – 15 districts

- Atwood, Margaret – 3 titles – 15 bans – 11 districts

- Hutchinson, Shaun David – 6 titles – 15 bans – 7 districts

- Albertalli, Becky – 7 titles – 14 bans – 11 districts

- Miedoso, Andrés – 14 titles – 14 bans – 1 district

- Gino, Alex – 2 titles – 13 bans – 11 districts

- Woodson, Jacqueline – 11 titles – 13 bans – 6 districts

- Asher, Jay – 1 title – 12 bans – 12 districts

- Hosseini, Khaled – 1 title – 12 bans – 12 districts

- Dawson, Juno – 2 titles – 12 bans – 11 districts

- Tamaki, Mariko – 2 titles – 12 bans – 11 districts

- Picoult, Jodi – 3 titles – 12 bans – 10 districts

- Glines, Abbi – 9 titles – 12 bans – 5 districts

- Peters, Julie Anne – 8 titles – 12 bans – 4 districts

- Cast, Kristen – 12 titles – 12 bans – 1 district

- Cast, P. C. – 12 titles – 12 bans – 1 district

- Kuklin, Susan – 1 title – 11 bans – 11 districts

- Telgemeier, Raina – 1 title – 11 bans – 11 districts

- Jennings, Jazz – 2 titles – 11 bans – 10 districts

- Stone, Nic – 3 titles – 11 bans – 10 districts

- Lockhart, E. – 3 titles – 11 bans – 8 districts

- Brown, Monica – 10 titles – 11 bans – 2 districts

- Kendi, Ibram X. – 7 titles – 10 bans – 12 districts

- Anderson, Laurie Halse – 3 titles – 10 bans – 10 districts

- Curato, Mike – 1 title – 10 bans – 10 districts

- Rosen, L. C. – 1 title – 10 bans – 10 districts

- Clare, Cassandra – 5 titles – 10 bans – 8 districts

- Arnold, Elana K. – 7 titles – 10 bans – 5 districts

- Konigsberg, Bill – 5 titles – 10 bans – 5 districts

Who Is Behind Book Bans? The Role of Groups

Book bans in public schools have recurred throughout American history , with notable flare-ups in the McCarthy era and the early 1980s . But, while long present, the scope of such censorship has expanded drastically and in unprecedented fashion since the beginning of the 2021–22 school year. This campaign is in part driven by politics, with state lawmakers and executive branch officials pushing for bans in some cases. In Texas, for example, Republican state representative Matt Krause sent a letter and list with 850 books to school districts, asking them to investigate and report on which of the titles they held in libraries or classrooms. Political pressure of this sort in Texas , South Carolina , Wisconsin , Georgia , and elsewhere has been tied to hundreds of book bans.

Another major factor driving this dramatic expansion of book banning has been the proliferation of organized efforts to advocate for book removals. Organizations and groups involved in pushing for book bans have sprung up rapidly at the local and national levels, particularly since 2021. These range from local Facebook groups to the nonprofit organization Moms for Liberty, a national-level organization that now has over 200 chapters .

In the short period since their formation and expansion, these groups have played a role in at least half of the book bans enacted across the country during the 2021–22 school year. PEN America estimates that at least 20 percent of the book bans enacted in that time frame could be linked directly to the actions of these groups, with many more likely influenced by them. This 20 percent is based on publicly available information and includes cases where a parent or community group took direct action to seek the removal of books by making a statement at a school board meeting, submitting a list of books for formal reconsideration, or filing formal reconsideration paperwork; in many of these cases, the groups also openly touted their role in pushing for book removals. In an additional approximately 30 percent of bans, there is some evidence of the groups’ likely influence, including the use of common language or tactics.

| PEN America has identified at least 50 groups operating at the national, state, or local levels to campaign and mobilize around what they view as the dangers of books in K-12 schools, and advocating for book restrictions and bans. Of these 50 groups, eight have regional and local chapters that, between them, number at least 300 in total; some of these operate predominantly through social media. This presents a minimum count, based on news coverage, school board meetings, and groups’ public presence online. , has spread most broadly, with over 200 local chapters identified on their . Other national groups with branches include US Parents Involved in Education (50 chapters), No Left Turn in Education (25), MassResistance (16), Parents’ Rights in Education (12), Mary in the Library (9), County Citizens Defending Freedom USA (5), and Power2Parent (5).While some of these groups have existed for years, the overwhelming majority are of recent origin: more than 70 percent (including chapters) were formed since 2021.

|

These varied groups do not all share identical aims, but they have found common cause in advancing an effort to control and limit what kinds of books are available in schools. Broadly, this movement is intertwined with political movements that grew throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, including fights against mask mandates and virtual school, as well as disputes over “critical race theory” that in some states fueled the introduction of educational gag orders prohibiting discussion of “divisive” concepts in classrooms. While many of these groups use language in their mission statements about parents’ rights or religious or conservative views , some also make explicit calls for the exclusion of materials that touch on race (sometimes explicitly critical race theory ) or LGBTQ+ themes .

The impact and role of these groups has been noted in dozens of cases of book challenges around the country. For example, local chapters of Moms for Liberty have been reported as driving efforts to remove books from Florida to North Carolina to Virginia . Chapters of County Citizens Defending Freedom pushed for book removals in Polk County Schools, Florida and Corpus Christi, Texas . In Clark County, Nevada , the group Power2Parent successfully got a book removed from a 10th grade honors English class reading list. Leaders of state chapters of Parents Involved in Education have been quoted calling for book removals at school board meetings in Kansas , Tennessee , and South Dakota , When two students filed a lawsuit with the ACLU of Missouri they claimed the removal of books in Wentzville, MO was part of a “targeted campaign by the St. Charles County Parents Association and No Left Turn in Education’s Missouri chapter to remove particular ideas and viewpoints about race and sexuality from school libraries.”

Although the channels of influence and coordination among these groups are not always clear, and the groups range in size and impact, their role in the book banning movement of the past year is a consistent theme.

In Madison County Schools, Mississippi , for example, a parent who identified herself as the point person for Mississippi’s chapter of MassResistance (a national group also classified as an anti-LGBTQ+ “hate group” by the Southern Poverty Law Center ), expressed “concerns regarding critical race theory” and worked with parents to review the schools’ online library catalogs, seeking books that had been challenged in other parts of the country. By April 2022, the district had said the books were being placed in “restricted circulation” (requiring a parent’s permission to check out) while they were being reviewed.

MassResistance—which claims the January 6 attack on the US Capitol was “clearly a setup” and alleges a “Black Lives Matter and LGBT assault” on schools— took credit for bringing these restrictions about, declaring, “ MassResistance gets involved—things start happening! ” and referencing “‘groomer moms’ in the community” who opposed the removal of the 22 books. In August, the school board voted to place some of the books back in full circulation, but a list of 10 books remain restricted, including Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Bluest Eye , along with The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Another parent who was a vocal critic of the books at a local school board meeting was also identified as the chair of the Moms for Liberty Madison chapter.

Some groups without significant national operations have also had far reach. The Florida Citizens Alliance (FLCA), for example, was founded in 2013 to “champion education reform.” But its leaders have spent considerable time and energy opposing climate change education , arguing for the elimination of sex education in K–12 schools , and publishing the misleading 2021 Objectionable Materials Report: Pornography and Age-Inappropriate Material in Florida Public Schools (provocatively named the Porn in Schools Report on their website). With a mailing of their “Porn in Schools” report and follow-up via their legal representative, the Pacific Justice Institute, the FLCA pushed for bans across the state. Ultimately they have played a role in bans in several counties in Florida, such as Jackson County School District , Orange County Public Schools , St. Lucie County Schools , Polk County School District , and Walton County School District . In Walton County School District , the superintendent responded to their email by directing the removal of all books on the list, despite admitting , “I haven’t read one paragraph of the books at this time.” Their advocacy was also connected to ‘warning labels’ being applied to over 100 books in school libraries in Collier County , Florida.

Even smaller, less formal groups have had an impact too. Between February and April 2022, Nixa Public Schools in Missouri received 17 complaints about 16 books, each citing “inappropriate and sexually explicit content,” which were subsequently banned. The woman who filed the most requests confirmed that she was a member of “Concerned Parents of Nixa,” a private Facebook group where community members gather to fight “questionable books, curriculum, and other materials such as sex education in Nixa Public Schools.” Concerned Parents of Nixa recently changed its name to Concerned Parents of the Ozarks . While it is unclear whether their list was solely from another group, the titles they challenged are the same ones seen over and over again amongst school libraries who have had to pull or otherwise eliminate access to them as a result.

These groups have employed a range of common tactics to advance book banning in public schools. Most of these tactics, it should be emphasized, are tactics that many advocacy and community organizing groups employ to a wide range of ends. Citizens are free to organize and advocate; these liberties are protected under the First Amendment’s safeguards for freedom of association. PEN America’s concern is not with the use of such standard organizing and mobilization tactics but rather with the end goal of restricting or banning books. That said, in some cases, members of these groups have also crossed a line, using online harassment or filing criminal complaints to pressure local officials and educators.

One common trend is that many of these groups circulate to their audiences lists of books to target. PEN America saw dozens of lists that circulated online during the 2021–22 school year, and these also occasionally morphed or grew in the process of being shared among groups.

Some groups appear to feed off work to promote diverse books, contorting those efforts to further their own censorious ends. They have inverted the purpose of lists compiled for teachers and librarians interested in introducing a more diverse set of reading materials into the classroom or library. For example, one group, the Idaho Freedom Foundation, referenced multiple lists celebrating books about equity, inclusion, and human rights under the header “ Federal Agencies Are Sexualizing Idaho Libraries ,” accused the federal government of using “taxpayer dollars to promote a pernicious ideology to young children,” and called on the Idaho legislature to reject federal funds for libraries. Another group, the Michigan Liberty Leaders , took an image of books from the Welcoming Schools bullying prevention program created by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation—including books designed to support LGBTQ+ students—and added alarmist language about the books being in schools.

In another example, the list of books created by the FLCA in their “ Porn in Schools” report originated from the website Christian Patriot Daily, which said it received its list from a graduate student in early childhood development promoting LGBTQ+ resources for caregivers. This list has in turn appeared to spread across state lines. In March 2022, in Cherokee County School District in Georgia, a parent presented a list of 225 book challenges . In that list, 41 titles were not only identical to those in the 2021 FLCA report, but they were in the same order, with the same typos found in the original list. The same list also appears in a database of books on the website of Forest Hills Parents United, based in Michigan.

The books on these lists are often framed as dangerous or harmful, and the lists have been used to quicken the pace of book banning, often in violation of or with disregard for established, neutral processes, with demands that all books on such lists be removed from schools immediately.

Members of these groups also flood school districts with official challenges to books and mobilize supporters to dominate discussions at public board meetings. In some cases, parents have screamed to disrupt meetings, or threatened violence . In response to such threats, the Sarasota County, Florida, school board placed limits on public comments at board meetings. School boards in Carmel Clay, Indiana , and Sonoma Valley, California , are considering similar restrictions.

Some groups have at times also helped spur complaints from community members without children in public school. In St. Lucie County Schools, Florida, a complainant submitted official reconsideration challenges for 44 titles from the FLCA’s “Porn in Schools” report, only 20 of which were found in the district. The complainant told a reporter that although they personally did not have children in the district, they were “picked” after attending a meeting hosted by FLCA. “I got picked because I took it seriously,” the complainant said.

In the fall of 2021 in Williamson County Schools, Tennessee, Moms for Liberty pushed for a review of the reading curriculum, stating that the curriculum violated a state law (which PEN America counts as an educational gag order ). The complaints said materials were too focused on the country’s segregationist past and might make children feel uncomfortable about race. After the review, the district published a report that outlined the relationship of complainants to the school district, and only 14 of the 37 complainants had children enrolled and affected by the curriculum targeted by the complaint. Another 14 had no children in the school system at all, while 9 had children enrolled in middle or high schools. One book, Walk Two Moons by Sharon Creech, was ultimately banned permanently, and multiple books had bans placed on what content could be taught, including restrictions on showing students pages 12–13 of Sea Horse: The Shyest Fish in the Sea by Chris Butterworth—pages that included an illustration of the sea creatures twisting tails, rubbing tummies, and mating.

| Although “parents’ rights” is a powerful piece of political rhetoric, in most instances, it is being invoked to mean rights for a particular group of parents with distinct ideological views, rather than a neutral effort to engage all parents and students in ensuring that schools uphold free speech rights. While parents and guardians ought to be partners with educators in their children’s education, and need channels for communicating with school administrators, teachers, and librarians, particularly concerning the education of their own children, public schools are by design supposed to rely on the expertise, ethics, and discretion of educational professionals to make decisions. In too many places, today’s political rhetoric of “parents’ rights” is being weaponized to undermine, intimidate, and chill the practices of these professionals, with potentially profound impacts on how students learn and access ideas and information in schools.

|

The role of organized local, regional, and national groups in book-banning campaigns has several implications that are distinct from prior patterns where book challenges tended to originate locally and spontaneously by individual parents. The groups behind these bans often furnish materials, messaging templates, and other kinds of directions that easily facilitate book challenges and imbue their efforts with a degree of focus and determination that can take local school officials by surprise. Groups that enjoy political ties and advocacy resources are able to marshal political support behind their censorious campaigns, putting local teachers, administrators, and school board officials under pressure. Mobilization on social media or at board meetings can also create an atmosphere of intimidation that may undermine the ability of a community to discuss and adjudicate concerns in a measured way.

Most schools’ book reconsideration policies have been created to respond to challenges filed by individual parents over particular books their children read; now that challenges are coming with such increased frequency and scope, schools and districts have sometimes struggled to keep up, as well as to withstand the heightened political pressure and public scrutiny.

The other key implication of the organized nature of these banning campaigns is their ability to reach scale. Whereas traditional book challenges were one-off incidents, the current pattern of escalating, copycat banned book efforts across the country is a testament to the ability of campaigners to leverage tools and communications channels to push for censorship across the country. As their tactics and methods evolve, it stands to reason that a growing number of schools, communities, and legislatures will confront similar challenges.

| In another sign of the escalation of tactics to restrict books, criminal charges have been pursued against school officials and librarians in a number of cases in the past year. From to to to , sheriffs have received complaints of the distribution of pornography in schools, among other charges. PEN America found at least 15 documented cases of criminal charges being filed or complaints being filled out regarding distribution of obscenity or pornographic material in public and school libraries during the 2021–22 school year, The leader of Moms for Liberty in Indian River, Florida, accusing the school board and superintendent of distributing pornography. Other groups, including , , and , have issued calls to action for individuals to file criminal complaints about books. While these cases have all rightly been dropped by law enforcement, the movement to involve police in efforts to ban books is another aspect of this campaign that is unprecedented in recent memory. Regardless of the legal outcome, the tactic of pressing criminal charges against educators for offering books to students is an attempt to intimidate and discourage librarians and teachers from teaching or offering books that might spark such a virulent response.

|

Where Are Book Bans Happening?

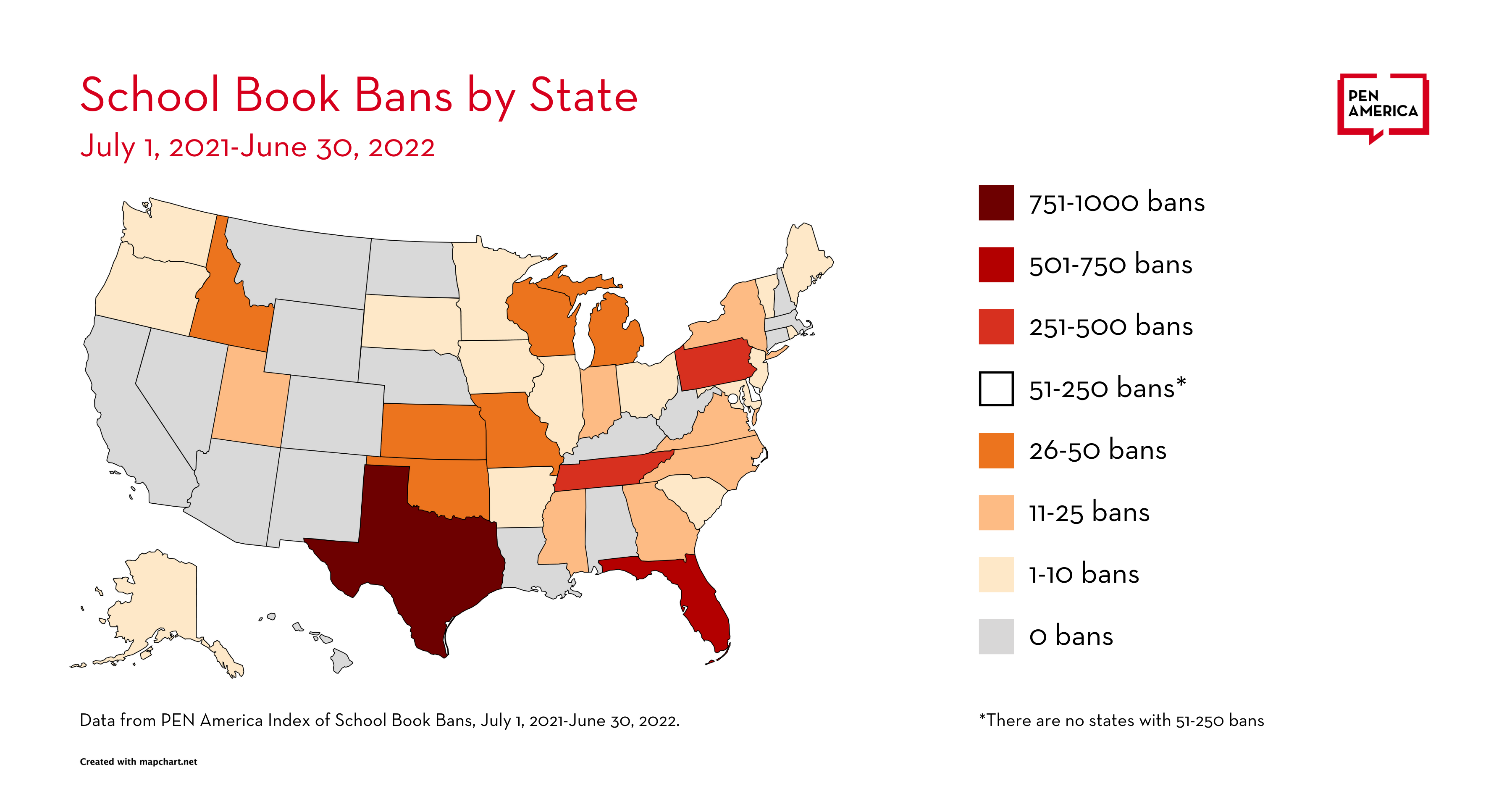

PEN America reported in the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022) that book bans had occurred in 86 school districts in 26 states in the first nine months of the 2021-22 school year. With additional reporting, and looking at the 12-month school year, the Index now lists banned books in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts include 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students.

Total States and Districts with Banned Books

- States with Bans: 32

- Districts with Bans: 138

Total Bans by State

- Texas : 801 bans, 22 districts

- Florida : 566 bans, 21 districts

- Pennsylvania : 457 bans, 11 districts

- Tennessee : 349 bans, 6 districts

- Oklahoma : 43 bans, 3 districts

- Michigan : 41 bans, 4 districts

- Kansas : 30 bans, 2 districts

- Wisconsin : 29 bans, 6 districts

- Missouri : 27 bans, 8 districts

- Idaho : 26 bans, 3 districts

- Georgia : 23 bans, 2 districts

- Mississippi : 22 bans, 1 district

- Virginia : 19 bans, 9 districts

- Indiana : 18 bans, 3 districts

- North Carolina : 16 bans, 5 districts

- New York : 13 bans, 4 districts

- Utah : 12 bans, 3 districts

Rewriting the Rules

Beyond the school book bans documented in the Index and the efforts of various parties to see their implementation and enforcement, the past year has also seen attempts to change laws and school district policies in ways that make censorious challenges easier to file and impose. Even where such laws and policy changes have not been enacted, their chilling effect has been broadly felt.

Legislative Changes

The book-banning movement has operated in conjunction with legislative efforts to pass educational gag orders, all as part of what PEN America has referred to as the “ ed scare ”—a campaign to censor free expression in education. While the effort to constrain teachers has primarily progressed in state legislatures—as PEN America has documented, most recently in our August 2022 report America’s Censored Classrooms —and the effort to ban books has erupted mostly within local school districts, the two have increasingly merged, with some state legislators proposing or supporting bills that directly impact the selection and removal of books in school classrooms and libraries.

- Florida. Beginning in the summer of 2022, book bans in some Florida school districts were reportedly tied to the passage of the “ Parental Rights in Education ” law signed by Governor DeSantis in March 2022. Frequently referred to as the “Don’t Say Gay” law, this legislation prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade, and also in grades 4–12 unless “age appropriate” and “developmentally appropriate” according to state standards. During the same legislative session, Florida lawmakers also enacted HB 1467 , which, in the name of classroom “transparency,” modifies laws governing the selection and discontinuance of instructional materials in public school curricula and libraries, mandates elementary schools to list in a searchable manner all materials held in their libraries, and implicitly encourages greater public scrutiny. This combination of a new law enabling tighter scrutiny and outside monitoring of curricular and book choices in classrooms, coupled with a new prohibition on instruction on certain topics, has done what was intended: it has created a chilling effect on teaching and learning. In anticipation of the law, books were removed in Palm Beach County in June 2022. Over the summer, more books were reported being removed from districts across the state, including a plan to “pause” classroom libraries entirely in Brevard, Florida .

- Georgia. SB 226 passed in March 2022 and will change the way school libraries operate, removing some local control and consolidating power at the state level. The law vacates all school policies on book challenges and requires local school boards to create new policies for complaints, designed to make it easier to remove books with allegedly “offensive content.” Under this new law , school principals have only ten days to determine whether a book challenged for being “harmful to minors” by any parent or guardian will be removed or restricted from schools.

- Tennessee. SB 2247 expanded the State Textbook and Instructional Materials Quality Commission and required it to provide guidance for school libraries. It also created a statewide process for appealing decisions on challenged books to the state commission. These changes will make it easier for books to be banned from student access statewide on the basis of challenges filed in individual districts.

- Utah. HB 374 , “Sensitive Materials in Schools,” was signed into law in March 2022 by Gov. Spencer Cox and prohibits from public schools certain sensitive instructional materials considered pornographic or indecent. It also requires the State Board of Education and the Office of the Attorney General to provide guidance and training to public schools on identifying sensitive materials, a process that must include parents deemed reflective of a school’s community. Although the law does not alter the definition of obscene materials in state statutes, it has been followed by guidance from the attorney general instructing schools to remove “immediately” any books deemed pornographic. The law has already had an impact, for example, in Alpine School District.

- Missouri. SB 775 , an omnibus bill on sex crimes and crimes against minors, included an amendment that makes it a class A misdemeanor if a person “affiliated with a public or private elementary or secondary school” provides “explicit sexual material” to a student, defined in the bill as applying only to visual depictions of genitals or sexual intercourse, not written descriptions. The bill also contains exceptions for works of art, works of “anthropological significance,” and materials for a science or sexual education class. In the wake of the bill taking effect in August, a number of school districts in the St. Louis area removed books from their shelves preemptively, particularly graphic novels, which appear to be uniquely susceptible to challenge under the law’s provisions. Violation of the law could lead to jail or fines for teachers, librarians, and school administrators. Although police have said they will not enforce it, the law is nevertheless already having a chilling effect in the state.

Changing District Policies

Under the plurality Supreme Court decision in Island Trees v. Pico , banning or restricting books in public schools for content- or viewpoint-specific reasons is unconstitutional. To safeguard these rights, the ALA and the NCAC have developed best practice guidelines for book reconsideration processes school districts can adopt concerning library materials and instructional materials for which review is requested, whether by a parent, other community member, administrator, or other source. As discussed at length in Banned in the USA , these guidelines are intended to ensure that challenges are addressed in consistent, reasoned, fact-based ways while protecting the First Amendment rights of students and citizens and guarding against censorship.

In the 2021–22 school year, fewer than 4 percent of book bans tracked by PEN America were enacted pursuant to these established best practice guidelines aimed to safeguard students’ rights and protect against censorship. Instead, in numerous cases, school districts either ignored or circumvented their own policies when removing particular books. In other cases, districts followed policies that failed to afford full protection for freedom of expression—for example, by restricting student access to books while they are under review, by failing to convene a committee to review the complaint, or by not having the complainant complete the paperwork or read the whole book to which they were objecting as required by the stated policies.

In some communities where existing procedures are more aligned with the standards set forth in the ALA and NCAC guidelines, or where advocates for book banning have been stifled in their efforts, there have been new efforts to alter those policies and make the removal of books easier.

Such efforts often include a drive to change the “obscenity” determination used to ban books—usually without regard for the relevant legal standard . These changes have taken place in nearly a dozen districts, such as Frisco ISD in Texas , which in June revised its book policies to remove the existing standards of obscenity for materials and replace them with more stringent standards taken from the Texas Penal Code. In practice, this means that a sentence or image may be enough to get a book banned—and that book content will be evaluated without proper context. The inevitable result of the Frisco ISD and similar changes will be increased policing of content in books for young people, as well as the continued erosion of their right to access these materials.

Some policy changes have been advanced at the state level as well, with Texas leading the way. In April, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) announced new standards for how school districts should handle all content in their libraries. The Texas standards follow state representative Matt Krause’s October 2021 public letter “initiating an inquiry into Texas school district content,” as well as a public letter to the Texas Association of School Boards (TASB) from Gov. Greg Abbott in November 2021 , asking schools to investigate why their libraries contained allegedly “obscene” and “pornographic” content in schools. Abbott did not provide any specific content examples. (It is worth noting that TASB has no power to change or even to recommend district policies.)

The policy recommendations from the TEA, compiled in response to the public letter from Governor Abbott, implemented four significant process changes of note, none of which comport with accepted best practices. The changes include the following:

- Singling out school library acquisitions for intensive review, more so even than the review process for curricular materials.

- Placing a ten-day deadline for reconsideration of challenged material. In an apparent acknowledgement that such a tight timeline will preclude a thorough review, the provisions simultaneously dropped the requirement that reconsideration committee members read the challenged material.

- Requiring librarians to host twice yearly review periods for parents to raise objections or voice concerns prior to accepting new acquisitions.

- Tying the consideration of material containing sexual content to the Texas Penal Code, point 3 of which states that a harmful material is defined as one “utterly without redeeming social value for minors.” If a book falls afoul of the state’s “harmful materials” standards—which are not aligned with Supreme Court jurisprudence defining obscenity in such works—it cannot be part of a school library.

While Texas has not made this policy mandatory for its school districts, the policy has begun to shape school library policies. By July 2022, at least two Texas school districts in Tarrant County had changed their acquisition policies based on the TEA’s model policy. For example, now if a book is challenged and removed in Carroll ISD, Texas, that book cannot be requested again for students for five years. In Keller ISD, this provision was changed to ten years.

The trend of district-level policy changes, which largely began in Texas, has picked up steam in other places too. For example, the school board in Hamilton County, Tennessee, accepted board policy recommendations from a special book review committee in March 2022, which removed a statement on the principles of intellectual freedom from the ALA’s “Library Bill of Rights.” This was a striking departure from the norm, as up until this year, it was a generally accepted standard that school board policies concerning acquisitions management and curricular development would reference or otherwise incorporate principles put forth by the Office for Intellectual Freedom of the ALA.

In another instance, Central Bucks County School District in Pennsylvania voted in July 2022 to reassign oversight of library collections from library and education professionals to a committee of the “ superintendents designees ”—politicizing a task previously performed by library and education professionals well versed in sound acquisition principles and policies. The district further undermined its education professionals by moving to refocus collection acquisition strategies away from instructional needs—as determined by teachers, librarians, and other education professionals—toward potentially politicized decisions, such as evaluating books for sexual content using vague standards to determine whether a book should be placed in the library. In so doing, the district ran afoul of NCAC guidelines to ensure practices that “advance fundamental pedagogical goals and not subjective interests.”

From Kansas to Illinois , Indiana to Virginia , North Carolina to Florida , myriad efforts to implement and enforce censorious practices are effectively allowing some parents and citizens to constrain the availability of books for all students in their and other school communities. A raft of changes are making it easier to ban more books more quickly, undermining educators’ and librarians’ work and ultimately students’ rights to access information.

Preemptive Bans

The unrelenting wave of challenges to the inclusion of certain books in school libraries—whether promulgated at the urging of an individual community member, grassroots organization, or government official—has spurred another phenomenon: preemptive book banning. In April, May, and June 2022, PEN America tracked several cases where school administrators have banned books in the absence of any challenge in their own district, seemingly in a preemptive response to potential bills , threats from state officials , or challenges in other districts .

The most significant ban of this type occurred in Collierville, Tennessee , where a school district removed 327 books from shelves in anticipation of a state law that ultimately did not pass. Administrators sorted the books into tiers based on how much the books focus on LGBTQ+ characters or story lines; tier 3, for instance, reflected that “the main character of the book is part of the LGBTQ community, and their sexual identity forms a key component of the plot. The book may contain suggestive language and/or implied sexual interactions.” If a book reached tier 5, according to the sorting guidelines, “the books are being pulled.”

Other preemptive bans were responses to actions at the state level or in neighboring districts. For example, according to Texas media reports , bans in Katy ISD, Clear Creek ISD, and Cypress-Fairbanks ISD were the result of administrators responding either to what was happening in other districts or to an 850-book list compiled and circulated to education officials by Texas state representative Matt Krause .

Silent Bans and Other Restrictions

Finally, PEN America has tracked other instances of books included in banned book displays, or other disputed materials, being quietly removed to avoid controversy. Books are also being labeled or marked in some way as “inappropriate” both in online catalogs and on physical titles themselves. In the Collier County School District in Florida, for instance, warning labels were attached to a group of more than 100 books that disproportionately included stories featuring LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color. While these cases are not included in the Index because they do not meet PEN America’s definition of school book bans, these types of actions could have a chilling effect—applying a stigma to the books in question and the topics they cover—and they merit further study.

While several stories of preemptive and silent book bans have made it into the news or to the attention of PEN America, it is clear that mounting censorship and the punitive approach being taken to the enforcement of book bans is having wide ripple effects . The Supreme Court has sharply restricted viewpoint- and subject-matter-based restrictions on speech precisely because in addition to rendering certain ideas, stories, and opinions off-limits, such measures cast a wider chilling effect on expression. Given the rapid spread of book bans across the country, it seems inevitable that the resulting climate of caution and fear will result in a reluctance among teachers, administrators, and librarians to take risks that could affect their own employment , their budgets, their reputations, and even their personal safety . Emerging data, like a recent survey of school librarians by the School Library Journal in which 97% said they “always,” “often,” or “sometimes” weigh how controversial subject matter might be when deciding on book purchases is pointing clearly to these alarming trends.

| Beyond formal book bans, there have also been efforts to keep books out of the hands of children even if they remain in circulation. One prominent example of such activity was “ ,” an initiative of CatholicVote.org in June 2022. CatholicVote encouraged members to check out books from the Pride 2022 displays in children’s sections of public libraries and to take pictures of the empty shelves. Although the group instructed participants to “return your library books on time” and to follow the “letter of the law, so to speak,” was an attempt to remove library materials from availability and to limit students’ access to LGBTQ+-affirming books. In the same month, there were efforts to ban displays of LGBTQ+ materials entirely in some public libraries, such as in , and . The latter resulted in an effort to terminate a librarian for allegedly violating the prohibition.

|

The unprecedented flood of book bans in the 2021–22 school year reflects the increasing organization of groups involved in advocating for such bans, the increased involvement of state officials in book-banning debates, and the introduction of new laws and policies. More often than not, current challenges to books originate not from concerned parents acting individually but from political and advocacy groups working in concert to achieve the goal of limiting what books students can access and read in public schools.