Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Recognizing new trends in brain drain studies in the framework of global sustainability.

1. Introduction

2. methodology, 3.1. thematic sources trends analysis, 3.2. actors and terms trend analysis, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions.

- RQ1. Is there a critical mass of scientific research regarding the brain drain phenomenon?

- RQ2. How has the study of the brain drain phenomenon evolved thematically and conceptually?

- RQ3. Is it possible to identify classic authors on this topic? Are we facing the emergence of new reference authors?

Supplementary Materials

Author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

| (WOS:000234146500004; | WOS:000166022000012; | WOS:000254272900004; |

| WOS:000071167600003; | WOS:000309000200002; | WOS:000172825700002; |

| WOS:000288642600005; | WOS:000224485300033; | WOS:000244394800003; |

| WOS:000233182800006; | WOS:A1997XZ77600012; | WOS:000273110500039; |

| WOS:000172825700006; | WOS:000233665800005; | WOS:000227167900018; |

| WOS:000085041200002; | WOS:000294111300005; | WOS:000245718300010; |

| WOS:000187517000002; | WOS:000287946000034; | WOS:000237827600002; |

| WOS:000285215000008; | WOS:000260472100007; | WOS:000175968700009; |

| WOS:000078262000008; | WOS:000240042900004; | WOS:000244400600007; |

| WOS:000188094700002; | WOS:000266981200004; | WOS:000208405300002; |

| WOS:A1991FZ02600013; | WOS:000290580600007; | WOS:000076715600017; |

| WOS:000288642600003; | WOS:000284673700004; | WOS:000250686900003; |

| WOS:000304032100003; | WOS:000264980600001; | WOS:000258799000006; |

| WOS:000299015400005; | WOS:A1982NK73000007; | WOS:000329962500006; |

| WOS:A1992JZ95900009; | WOS:000233498800003; | WOS:000288642600006; |

| WOS:000250686900002; | WOS:000239666000001; | WOS:000316530400008; |

| WOS:000340978200004; | WOS:000311608300004; | WOS:000240492800002; |

| WOS:000188509300003; | WOS:000243108000001; | WOS:000261309500008; |

| WOS:000227089400004; | WOS:000223696300001; | WOS:000342754300006; |

| WOS:000274474400008; | WOS:000319106200006; | WOS:000261194400002; |

| WOS:000285269700011; | WOS:000243085300006; | WOS:000265205100001; |

| WOS:000294111300006; | WOS:000345730400002). | |

| AND | ||

| (WOS:000329962500006; | WOS:000316530400008; | WOS:000340978200004; |

| WOS:000342754300006; | WOS:000319106200006; | WOS:000345730400002). |

| UT = (WOS:A1992HB74200007 OR | WOS:000078262000008 OR | WOS:000188094700002 OR |

| WOS:000284673700004 OR | WOS:000264980600001 OR | WOS:000286783500004 OR |

| WOS:000288642600005 OR | WOS:000320573500007 OR | WOS:000331431900020 OR |

| WOS:000249748300001 OR | WOS:000281715300011 OR | WOS:000297230300004 OR |

| WOS:000271358200001 OR | WOS:000295151100013 OR | WOS:000252975900002 OR |

| WOS:000308685300007 OR | WOS:000310022600003 OR | WOS:000340080600013 OR |

| WOS:000260472100007 OR | WOS:000280919900004 OR | WOS:000288381200009 OR |

| WOS:000267623900010 OR | WOS:000342246100009 OR | WOS:000261381100008 OR |

| WOS:000291316900010 OR | WOS:000285215000008 OR | WOS:000254735000005 OR |

| WOS:000291545200006 OR | WOS:000267655100023 OR | WOS:000300343200001 OR |

| WOS:000259545500004 OR | WOS:000334324800004 OR | WOS:000281491500003 OR |

| WOS:000263716700003 OR | WOS:000258427700002 OR | WOS:000265690100001 OR |

| WOS:000276131700032 OR | WOS:000333237500010 OR | WOS:000310448600001 OR |

| WOS:A1993KJ94700010 OR | WOS:000261636400003 OR | WOS:000273514100007 OR |

| WOS:000312808400003 OR | WOS:000264173000003 OR | WOS:000297818800014 OR |

| WOS:000405669300001 OR | WOS:000267375000003 OR | WOS:000309000200002 OR |

| WOS:000320182100004 OR | WOS:000320780800003 OR | WOS:000327726700005 OR |

| WOS:000319106200006 OR | WOS:000427151500003 OR | WOS:000266042400002 OR |

| WOS:000308941200005 OR | WOS:000331601600015 OR | WOS:000343022000035 OR |

| WOS:000427340900009 OR | WOS:000277681400003 OR | WOS:000315645600024 OR |

| WOS:000414461300024 OR | WOS:000299015400005 OR | WOS:000288638100004 OR |

| WOS:000291545200001 OR | WOS:000288642600008 OR | WOS:000330620100002 OR |

| WOS:000340019300012 OR | WOS:000338719600004 OR | WOS:000288642600010 OR |

| WOS:000248171900004 OR | WOS:000274111600010 OR | WOS:000288642600009 OR |

| WOS:000315396200029 OR | WOS:000449242400011 OR | WOS:000452955800015 OR |

| WOS:000311008500006 OR | WOS:000345180700010 OR | WOS:000271057100012 OR |

| WOS:000280679100016 OR | WOS:000308243600006 OR | WOS:000308449600001 OR |

| WOS:000340978200004 OR | WOS:000401389900014 OR | WOS:000306666800007 OR |

| WOS:000337870200003 OR | WOS:000312919300002 OR | WOS:000347762000009 OR |

| WOS:000345730400002 OR | WOS:000385335100010 OR | WOS:000397164700001 OR |

| WOS:000338695700012 OR | WOS:000329796800001 OR | WOS:000320780800010 OR |

| WOS:000357326600005 OR | WOS:000256778400005 OR | WOS:000357390100007 OR |

| WOS:000313706300001 OR | WOS:000329373300001 OR | WOS:000319816100006 OR |

| WOS:000339959300004 OR | WOS:000368075800007 OR | WOS:000324669900002 OR |

| WOS:000268166800006 OR | WOS:000289471400006 OR | WOS:000315081400085 OR |

| WOS:000299099500007 OR | WOS:000342279400008 OR | WOS:000362100300006 OR |

| WOS:000379563900015 OR | WOS:000360861600009 OR | WOS:000461078200015 OR |

| WOS:000302864600009 OR | WOS:000308091700001 OR | WOS:000330816900010 OR |

| WOS:000320573400001 OR | WOS:000390105300004 OR | WOS:000343082200007 OR |

| WOS:000347597100026 OR | WOS:000361129200002 OR | WOS:000368192700014 OR |

| WOS:000372023800003 OR | WOS:000387115500002 OR | WOS:000464527200007 OR |

| WOS:000300825700005 OR | WOS:000307363500001 OR | WOS:000383292300010 OR |

| WOS:000386061000006 OR | WOS:000351785500030 OR | WOS:000355873600004 OR |

| WOS:000355341200003 OR | WOS:000374258700004 OR | WOS:000374258700006 OR |

| WOS:000374258700007 OR | WOS:000395202800008 OR | WOS:000414166000004 OR |

| WOS:000431159900027 OR | WOS:000441116700003 OR | WOS:000474023000007 OR |

| WOS:000379552100003 OR | WOS:000306009100012 OR | WOS:000343325000006 OR |

| WOS:000374107100003 OR | WOS:000397050200006 OR | WOS:000442291600008 OR |

| WOS:000396840900003 OR | WOS:000413253700005 OR | WOS:000466866800004 OR |

| WOS:000407728400009 OR | WOS:000488332600005 OR | WOS:000493341500001 OR |

| WOS:000498293300023 OR | WOS:000500954400015 OR | WOS:000427101400006 OR |

| WOS:000427151500008 OR | WOS:000261623300001 OR | WOS:000398964900022 OR |

| WOS:000269532500008 OR | WOS:000280393900004 OR | WOS:000418220900007 OR |

| WOS:000310026800006 OR | WOS:000429046800009 OR | WOS:000435188000260 OR |

| WOS:000393180000005 OR | WOS:000393337100011 OR | WOS:000385360800004 OR |

| WOS:000404474600003 OR | WOS:000419577100003 OR | WOS:000429891200021 OR |

| WOS:000427151500006 OR | WOS:000457127100016 OR | WOS:000431398600003 OR |

| WOS:000462693700026 OR | WOS:000470967500087 OR | WOS:000451375500006 OR |

| WOS:000483158300001 OR | WOS:000460550800004 OR | WOS:000488928600006 OR |

| WOS:000293102900005 OR | WOS:000476101600001 OR | WOS:000350824100003 OR |

| WOS:000501614100003 OR | WOS:000513134300001 OR | WOS:000494888300006 OR |

| WOS:000461972700001 OR | WOS:000513550900001 OR | WOS:000477949900001 OR |

| WOS:000465298600008 OR | WOS:000511153700004 OR | WOS:000484509700007 OR |

| WOS:000491553500013 OR | WOS:000500924400016 OR | WOS:000502881700007 OR |

| WOS:000512390700001 OR | WOS:000519945800005 OR | WOS:000523384400001 OR |

| WOS:000533653600001 OR | WOS:000542629600037 OR | WOS:000570768500006 OR |

| WOS:000539518600001 OR | WOS:000549611900001 OR | WOS:000552681100009 OR |

| WOS:000547804200006) |

- ERIC Thesaurus. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Kaukab, S. Situation of migration and potential available to reverse the brain drain—Case from Pakistan. Public Pers. Manag. 2005 , 34 , 103–112. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Arenas, J.L.; Castanos-Lomnitz, H.; Valles, J.; Gonzalez, E.; Arenas-Licea, J. Mexican scientific brain drain: Causes and impact. Res. Evaluat. 2001 , 10 , 115–119. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Docquier, F.; Lohest, O.; Marfouk, A. Brain drain in developing countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2007 , 21 , 193–218. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Torbat, A.E. The brain drain from Iran to the United States. Middle East J. 2002 , 56 , 272–295. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, H.G. The economics of the brain-drain—The Canadian case. Minerva 1965 , 3 , 299–311. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Oteiza, E. Emigration of engineers from Argentina—A case of Latin-American brain-drain. Int. Labour Rev. 1965 , 92 , 445–461. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grubel, H.G. Brain drain—A US dilemma. Science 1966 , 154 , 1420. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Perkins, J.A. Foreign aid and brain drain. Foreign Aff. 1966 , 44 , 608–619. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Portes, A. Determinants of brain-drain. Int. Migr. Rev. 1976 , 10 , 489–508. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kwok, V.; Leland, H. An economic-model of the brain-drain. Am. Econ. Rev. 1982 , 72 , 91–100. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carrasco, R.; Ruiz-Castillo, J. Spatial mobility in elite academic institutions in economics: The case of Spain. Series-J. Span. Econ. Assoc. 2019 , 10 , 141–172. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Sbalchiero, S.; Tuzzi, A. Italian Scientists Abroad in Europe’s Scientific Research Scenario: High skill migration as a resource for development in Italy. Int. Migr. 2017 , 55 , 171–187. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bhargava, A.; Docquier, F.; Moullan, Y. Modeling the effects of physician emigration on human development. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2011 , 9 , 172–183. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Sherr, K.; Mussa, A.; Chilundo, B.; Gimbel, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Hagopian, A.; Gloyd, S. Brain Drain and Health Workforce Distortions in Mozambique. PLoS ONE 2012 , 7 , e35840. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Bradby, H. International medical migration: A critical conceptual review of the global movements of doctors and nurses. Health 2014 , 18 , 580–596. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Wu, J.; Guo, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, W.; Xiang, Y. Information and Communications Technologies for Sustainable Development Goals: State-of-the-Art, Needs and Perspectives. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018 , 20 , 2389–2406. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, L.; Su, L.; Zhang, Y. Fragile States Metric System: An Assessment Model Considering Climate Change. Sustainability 2018 , 10 , 1767. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Yuret, T. An analysis of the foreign-educated elite academics in the United States. J. Informetr. 2017 , 11 , 358–370. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abramo, G.; D’Angelo, C.A.; Di Costa, F. A nation’s foreign and domestic professors: Which have better research performance? (the Italian case). High. Educ. 2019 , 77 , 917–930. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Saint-Blancat, C. Making Sense of Scientific Mobility: How Italian Scientists Look Back on Their Trajectories of Mobility in the EU. High Educ. Policy 2018 , 31 , 37–54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yuret, T. Tenure and turnover of academics in six undergraduate programs in the United States. Scientometrics 2018 , 116 , 101–124. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Antia, K.; Boucsein, J.; Deckert, A.; Dambach, P.; Račaitė, J.; Šurkienė, G.; Jaenisch, T.; Horstick, O.; Winkler, V. Effects of International Labour Migration on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Left-Behind Children: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 4335. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Torrisi, B.; Pernagallo, G. Investigating the relationship between job satisfaction and academic brain drain: The Italian case. Scientometrics 2020 , 124 , 925–952. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Saxenian, A. From brain drain to brain circulation: Transnational communities and regional upgrading in India and China. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2005 , 40 , 35–61. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bacchi, A. Highly Skilled Egyptian Migrants in Austria: A Case of Brain Drain or Brain Gain? J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2016 , 14 , 198–219. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Markova, Y.V.; Shmatko, N.A.; Katchanov, Y.L. Synchronous international scientific mobility in the space of affiliations: Evidence from Russia. SpringerPlus 2016 , 5 , 480. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Metcalfe, A.S. Nomadic political ontology and transnational academic mobility. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2017 , 58 , 131–149. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Stolz, Y.; Baten, J. Brain drain in the age of mass migration: Does relative inequality explain migrant selectivity? Explor. Econ. Hist. 2012 , 49 , 205–220. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ben-David, D. Soaring minds: The flight of israel’s economists. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2009 , 27 , 363–379. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hillier, C.; Sano, Y.; Zarifa, D.; Haan, M. Will They Stay or Will They Go? Examining the Brain Drain in Canada’s Provincial North. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2020 , 57 , 174–196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yin, M.; Yeakey, C.C. The policy implications of the global flow of tertiary students: A social network analysis. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2019 , 45 , 50–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Oberman, K. Can Brain Drain Justify Immigration Restrictions? Ethics 2013 , 123 , 427–455. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Stark, O.; Helmenstein, C.; Prskawetz, A. A brain gain with a brain drain. Econ. Lett. 1997 , 55 , 227–234. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Meyer, J.B. Network approach versus brain drain: Lessons from the diaspora. Int. Migr. 2001 , 39 , 91–110. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Naghavi, A.; Strozzi, C. Intellectual property rights and diaspora knowledge networks: Can patent protection generate brain gain from skilled migration? Can. J. Econ. Rev. Can. Econ. 2017 , 50 , 995–1022. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Siekierski, P.; Lima, M.C.; Borini, F.M. International Mobility of Academics: Brain Drain and Brain Gain. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2018 , 15 , 329–339. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De Arenas, J.L.; Castanos-Lomnitz, H.; Arenas-Licea, J. Significant Mexican research in the health sciences: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2002 , 53 , 39–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laudel, G. Study the brain drain: Can bibliometric methods help? Scientometrics 2003 , 57 , 215–237. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rutten, M. The Economic Impact of Medical Migration: An Overview of the Literature. World Econ. 2009 , 32 , 291–325. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ingwersen, P.; Jacobs, D. South African research in selected scientific areas: Status 1981–2000. Scientometrics 2004 , 59 , 405–423. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Payumo, J.G.; Lan, G.; Arasu, P. Researcher mobility at a US research-intensive university: Implications for research and internationalization strategies. Res. Evaluat. 2018 , 27 , 28–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Robinson-Garcia, N.; Sugimoto, C.R.; Murray, D.; Yegros-Yegros, A.; Lariyiere, V.; Costas, R. The many faces of mobility: Using bibliometric data to measure the movement of scientists. J. Informetr. 2019 , 13 , 50–63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Niu, X.S. International scientific collaboration between Australia and China: A mixed-methodology for investigating the social processes and its implications for national innovation systems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014 , 85 , 58–68. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Janger, J.; Campbell, D.F.J.; Strauss, A. Attractiveness of jobs in academia: A cross-country perspective. High. Educ. 2019 , 78 , 991–1010. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tian, F.M. Brain circulation, diaspora and scientific progress: A study of the international migration of Chinese scientists, 1998–2006. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2016 , 25 , 296–319. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- De-la-Vega-Hernández, I.M.; Barcellos-de-Paula, L. The quintuple helix innovation model and brain circulation in central, emerging and peripheral countries. Kybernetes 2020 , 49 , 2241–2262. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lodigiani, E.; Marchiori, L.; Shen, I.L. Revisiting the Brain Drain Literature with Insights from a Dynamic General Equilibrium World Model. World Econ. 2016 , 39 , 557–573. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bratt, S.; Hemsley, J.; Qin, J.; Costa, M. Big data, big metadata and quantitative study of science: A workflow model for big scientometrics. In Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology ; Erdelez, S., Agarwal, N.K., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 36–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vega, A.; Salinas, C.M. Scientific production analysis in public affairs of Chile and Peru. Challenges for a better public management. Lex 2017 , 15 , 463–478. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Clarivate Web of Knowledge. Available online: http://www.webofknowledge.com/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Serrano, L.; Sianes, A.; Ariza-Montes, A. Using bibliometric methods to shed light on the concept of sustainable tourism. Sustainability 2019 , 11 , 6964. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Maryam Farhadi, M.; Nader Ale Ebrahim, N.A. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013 , 9 , 18–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M. Social networks and graph theory in the search for distant knowledge in the field of industrial engineering. In Handbook of Research on Advanced Applications of Graph Theory in Modern Society ; Pal, M., Samanta, S., Pal, A., Eds.; IGI-Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 397–418. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Archuby, G.G.; Cellini, J.; González, C.M.; Pené, M.G. Interface de recuperación para catálogos en línea con salidas ordenadas por probable relevancia. Ciênc. Inf. 2000 , 29 , 5–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Price, D. A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. 1976 , 27 , 292–306. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Dobrov, G.M.; Randolph, R.H.; Rauch, W.D. New options for team research via international computer networks. Scientometrics 1979 , 1 , 387–404. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Analysis of hospitality, leisure, and tourism studies in Chile. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 7238. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Du, G.; Huang, L.; Zhou, M. Variance Analysis and Handling of Clinical Pathway: An Overview of the State of Knowledge. IEEE Access 2020 , 8 , 158208–158223. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vega-Muñoz, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. In search of ‘a research front’ in cruise tourism studies. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020 , 85 , 102353. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tran, B.X.; Nghiem, S.; Afoakwah, C.; Latkin, C.A.; Ha, G.H.; Nguyen, T.P.; Doan, L.P.; Pham, H.Q.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Characterizing obesity interventions and treatment for children and youths during 1991–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019 , 16 , 4227. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lotka, A.J. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926 , 16 , 317–321. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marzi, G.; Caputo, A.; Garces, E.; Dabic, M. A three decade mixed-method bibliometric investigation of the IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020 , 67 , 4–17. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bulik, S. Book use as a Bradford-Zipf Phenomenon. Coll. Res. Libr. 1978 , 39 , 215–219. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Morse, P.M.; Leimkuhler, F.F. Technical note—Exact solution for the Bradford distribution and its use in modeling informational data. Oper. Res. 1979 , 27 , 187–198. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pontigo, J.; Lancaster, F.W. Qualitative aspects of the Bradford distribution. Scientometrics 1986 , 9 , 59–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cleber-da-Silva, A.; Adilson-Luiz, P.; Márcio, M.; Moisés-Lima, D.; Gonzales-Aguilar, A. Análise bibliométrica do periódico Transinformação. Prof. Inf. 2014 , 23 , 433–442. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar, S. Application of Bradford’s law to human-computer interaction research literature. Desidoc J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 2014 , 34 , 223–231. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mengual-Andrés, S.; Chiner, E.; Gómez-Puerta, M. Internet and People with Intellectual Disability: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 10051. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shelton, R.D. Scientometric laws connecting publication counts to national research funding. Scientometrics 2020 , 123 , 181–206. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010 , 84 , 523–538. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cobo, M.; López-Herrera, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011 , 62 , 1382–1402. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 8469. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- López-Chao, V.; Amado Lorenzo, A. Architectural Graphics Research: Topics and Trends through Cluster and Map Network Analyses. Symmetry 2020 , 12 , 1936. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Miguel, S.; Tannuri de Oliveira, E.F.; Cabrini Grácio, M.C. Scientific Production on Open Access: A Worldwide Bibliometric Analysis in the Academic and Scientific Context. Publications 2016 , 4 , 1. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Zipf, G.K. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language ; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1932. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cassettari, R.R.B.; Pinto, A.L.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Santos, L.S. Comparison of Zipf’s law in textual content and oral discourse. Prof. Inf. 2015 , 24 , 157–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wild, D.; Jurcic, M.; Podobnik, B. The Gender Productivity Gap in Croatian Science: Women Are Catching up with Males and Becoming Even Better. Entropy 2020 , 22 , 1217. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- NubeDePalabras.es. Available online: https://www.nubedepalabras.es/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Kazemi, S.M.; Goel, R.; Jain, K.; Kobyzev, I.; Sethi, A.; Forsyth, P.; Poupart, P. Representation Learning for Dynamic Graphs: A Survey. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020 , 21 , 1–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Albort-Morant, G.; Henseler, J.; Leal-Millán, A.; Cepeda-Carrión, G. Mapping the field: A bibliometric analysis of green innovation. Sustainability 2017 , 9 , 1011. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005 , 102 , 16569–16572. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Bornmann, L.; Daniel, H.D. What do we know about the h index? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007 , 8 , 1381–1385. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kreiner, G. The slavery of the h-index-measuring the unmeasurable. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016 , 10 , 556. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Mester, G. Rankings scientists, journals and countries using h-index. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2016 , 14 , 1–9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Crespo, N.; Simoes, N. Publication performance through the lens of the h-index: How can we solve the problem of the ties? Soc. Sci. Q. 2019 , 100 , 2495–2506. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Prathap, G. Letter to the editor: Revisiting the h-index and the p-index. Scientometrics 2019 , 121 , 1829–1833. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Müller, S.M.; Mueller, G.F.; Navarini, A.A.; Brandt, O. National Publication Productivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Preliminary Exploratory Analysis of the 30 Countries Most Affected. Biology 2020 , 9 , 271. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Ellis, J.; Ellis, B.; Velez-Estevez, A.; Reichel, M.; Cobo, M. 30 years of parasitology research analysed by text mining. Parasitology 2020 , 147 , 1643–1657. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Vu, G.V.; Ha, G.H.; Nguyen, C.T.; Vu, G.T.; Pham, H.Q.; Latkin, C.A.; Tran, B.X.; Ho, R.C.M.; Ho, C.S.H. Interventions to Improve the Quality of Life of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Global Mapping During 1990–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 3089. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Oh, T.K. New estimate of student brain drain from Asia. Int. Migr. Rev. 1973 , 7 , 449–456. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Godfrey, E.M. Brain drain from low-income countries. J. Dev. Stud. 1970 , 6 , 235–247. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gish, O. Britain and America. Brain drains and brain gains. Soc. Sci. Med. 1970 , 3 , 397. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Das, M.S. Brain drain controversy and African scholars. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 1974 , 9 , 74–83. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Grubel, H.G. Reduction of brain drain—Problems and policies. Minerva 1968 , 6 , 541–558. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Psacharopoulus, G. Some positive aspects of economics of brain drain. Minerva 1971 , 9 , 231–242. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wilson, J.A.; Gaston, J. Reflux from brain drain. Minerva 1974 , 12 , 459–468. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Artuc, E.; Docquier, F.; Ozden, C.; Parsons, C. A Global Assessment of Human Capital Mobility: The Role of Non-OECD Destinations. World Dev. 2015 , 65 , 6–26. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Baruch, Y.; Dickmann, M.; Altman, Y.; Bournois, F. Exploring international work: Types and dimensions of global careers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013 , 24 , 2369–2393. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Beine, M.; Noel, R.; Ragot, L. Determinants of the international mobility of students. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2014 , 41 , 40–54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cerdin, J.L.; Selmer, J. Who is a self-initiated expatriate? Towards conceptual clarity of a common notion. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014 , 25 , 1281–1301. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gamlen, A. Diaspora Institutions and Diaspora Governance. Int. Migr. Rev. 2014 , 48 , 180–217. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kenney, M.; Breznitz, D.; Murphree, M. Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries. Res. Policy 2013 , 42 , 391–407. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mayeya, J.; Chazulwa, R.; Mayeya, P.N.; Mbewe, E.; Magolo, L.M.; Kasisi, F.; Bowa, A.C. Zambia mental health country profile. Int. Rev. Psych. 2004 , 16 , 63–72. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Alem, A.; Pain, C.; Araya, M.; Hodges, B.D. Co-Creating a Psychiatric Resident Program with Ethiopians, for Ethiopians, in Ethiopia: The Toronto Addis Ababa Psychiatry Project (TAAPP). Acad. Psych. 2010 , 34 , 424–432. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jenkins, R.; Kydd, R.; Mullen, P.; Thomson, K.; Sculley, J.; Kuper, S.; Carroll, J.; Gureje, O.; Hatcher, S.; Brownie, S.; et al. International Migration of Doctors, and Its Impact on Availability of Psychiatrists in Low and Middle Income Countries. PLoS ONE 2010 , 5 , e9049. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Da Costa, M.P.; Giurgiuca, A.; Holmes, K.; Biskup, E.; Mogren, T.; Tomori, S.; Kilic, O.; Banjac, V.; Molina-Ruiz, R.; Palumbo, C.; et al. To which countries do European psychiatric trainees want to move to and why? Eur. Psychiat. 2017 , 45 , 174–181. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zubaran, C. The international migration of health care professionals. Australas. Psychiatry 2012 , 20 , 512–517. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Nawka, A.; Kuzman, M.R.; Giacco, D.; Pantovic, M.; Volpe, U. Numbers of early career psychiatrists vary markedly among European countries. Psychiatr. Danub. 2015 , 27 , 185–189. [ Google Scholar ]

- Giurgiuca, A.; Rosca, A.E.; Matei, V.P.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Zgarbura, R.; Szalontay, A.S.; Pinto Da Costa, M. European Union Mobility, Income and Brain Drain. The Attitudes towards Migration of Romanian Psychiatric Trainees. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2018 , 63 , 268–278. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kao, C.H.C.; Lee, J.W. Empirical analysis of Chinas brain drain into United States. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1973 , 21 , 500–513. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lien, D.H.D. Economic-analysis of brain-drain. J. Dev. Econ. 1987 , 25 , 33–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Furst, E.J. Blooms taxonomy of educational-objectives for the cognitive domain—Philosophical and educational issues. Rev. Educ. Res. 1981 , 51 , 441–453. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dubas, J.M.; Toledo, S.A. Taking higher order thinking seriously: Using Marzano’s taxonomy in the economics classroom. Int. Rev. Econ. Educ. 2016 , 21 , 12–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Verenna, A.-M.A.; Noble, K.A.; Pearson, H.E.; Miller, S.M. Role of comprehension on performance at higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy: Findings from assessments of healthcare professional students. Am. Assoc. Anat. 2018 , 11 , 433–444. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hugo, G. Migration and development in Malaysia an emigration perspective. Asian Popul. Stud. 2011 , 7 , 219–241. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wojczewski, S.; Pentz, S.; Blacklock, C.; Hoffmann, K.; Peersman, W.; Nkomazana, O.; Kutalek, R. African Female Physicians and Nurses in the Global Care Chain: Qualitative Explorations from Five Destination Countries. PLoS ONE 2015 , 10 , e0129464. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Albarran, P.; Carrasco, R.; Ruiz-Castillo, J. Geographic mobility and research productivity in a selection of top world economics departments. Scientometrics 2017 , 111 , 241–265. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Yuan, S.; Shao, Z.; Wei, X.X.; Tang, J.; Hall, W.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Science behind AI: The evolution of trend, mobility, and collaboration. Scientometrics 2020 , 124 , 993–1013. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Seoane-Perez, F.; Martinez-Nicolas, M.; Vicente-Marino, M. The brain drain in Spanish Communication research: The perspective of Spanish academics abroad. Prof. Inf. 2020 , 29 , e290433. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Palozzi, G.; Brunelli, S.; Falivena, C. Higher Sustainability and Lower Opportunistic Behaviour in Healthcare: A New Framework for Performing Hospital-Based Health Technology Assessment. Sustainability 2018 , 10 , 3550. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Qadir, M.; Jimenez, G.C.; Farnum, R.L.; Dodson, L.L.; Smakhtin, V. Fog Water Collection: Challenges beyond Technology. Water 2018 , 10 , 372. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Knudsen, M.P.; Frederiksen, M.H.; Goduscheit, R.C. New forms of engagement in third mission activities: A multi-level university-centric approach. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2019 . Accepted. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Laibach, N.; Borner, J.; Broring, S. Exploring the future of the bioeconomy: An expert-based scoping study examining key enabling technology fields with potential to foster the transition toward a bio-based economy. Technol. Soc. 2019 , 58 , 101118. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Merk, B.; Litskevich, D.; Peakman, A.; Bankhead, M. IMAGINE—A Disruptive Change to Nuclear or How Can We Make More Out of the Existing Spent Nuclear Fuel and What Has to be Done to Make it Possible in the UK? ATW-Int. J. Nucl. Power 2019 , 64 , 353–359. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas, E. Toward a New Field of Global Engineering. Sustainability 2019 , 11 , 3789. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Chen, T.L.; Kim, H.; Pan, S.Y.; Tseng, P.C.; Lin, Y.P.; Chiang, P.C. Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 , 716 , 136998. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guo, R.; Lv, S.; Liao, T.; Xi, F.R.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, X.T.; Cao, X.J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.L. Classifying green technologies for sustainable innovation and investment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020 , 153 , 104580. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lubango, L.M. Effects of international co-inventor networks on green inventions in Brazil, India and South Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2020 , 244 , 118791. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Udugama, I.A.; Petersen, L.A.H.; Falco, F.C.; Junicke, H.; Mitic, A.; Alsina, X.F.; Mansouri, S.S.; Gernaey, K.V. Resource recovery from waste streams in a water-energy-food nexus perspective: Toward more sustainable food processing. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020 , 119 , 133–147. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Caviggioli, F.; Jensen, P.; Scellato, G. Highly skilled migrants and technological diversification in the US and Europe. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020 , 154 , 119951. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Capello, R.; Lenzi, C. The nexus between inventors’ mobility and regional growth across European regions. J. Geogr. Syst. 2019 , 21 , 457–486. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Bu, Y.; Kang, L.L.; Min, C.; Bian, Y.Y.; Tang, L.; Li, J. An investigation of the relationship between scientists’ mobility to/from China and their research performance. J. Informetr. 2020 , 14 , 101037. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schaaf, R. The Rhetoric and Reality of Partnerships for International Development. Geogr. Compass 2015 , 9 , 68–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aitsi-Selmi, A.; Murray, V.; Wannous, C.; Dickinson, C.; Johnston, D.; Kawasaki, A.; Stevance, A.S.; Yeung, T. Reflections on a Science and Technology Agenda for 21st Century Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2016 , 7 , 1–29. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Horan, D.A. New Approach to Partnerships for SDG Transformations. Sustainability 2019 , 11 , 4947. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Choi, G.; Jin, T.Y.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, S.K. Evolution of Partnerships for Sustainable Development: The Case of P4G. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 6485. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moreno-Serna, J.; Purcell, W.M.; Sanchez-Chaparro, T.; Soberon, M.; Lumbreras, J.; Mataix, C. Catalyzing Transformational Partnerships for the SDGs: Effectiveness and Impact of the Multi-Stakeholder Initiative El dia despues. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 7189. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Campbell, S. Interregional migration of defense scientists and engineers to the Gunbelt during the 1980s. Econ. Geogr. 1993 , 69 , 204–223. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gherheș, V.; Dragomir, G.-M.; Cernicova-Buca, M. Migration Intentions of Romanian Engineering Students. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 4846. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Humphries, N.; Connell, J.; Negin, J.; Buchan, J. Tracking the leavers: Towards a better understanding of doctor migration from Ireland to Australia 2008–2018. Hum. Resour. Health 2019 , 17 , 36. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lumpe, C. Public beliefs in social mobility and high-skilled migration. J. Popul. Econ. 2019 , 32 , 981–1008. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Beverelli, C.; Orefice, G. Migration deflection: The role of Preferential Trade Agreements. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2019 , 79 , 103469. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdelwahed, A.; Goujon, A.; Jiang, L. The Migration Intentions of Young Egyptians. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 9803. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Djajic, S.; Docquier, F.; Michael, M.S. Optimal education policy and human capital accumulation in the context of brain drain. J. Demogr. Econ. 2019 , 85 , 271–303. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Staniscia, B.; Deravignone, L.; Gonzalez-Martin, B.; Pumares, P. Youth mobility and the development of human capital: Is there a Southern European model? J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Boc, E. Brain drain in the EU: Local and regional public policies and good practices. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2020 , 23–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maxwell, T.W.; Chophel, D. The impact and outcomes of (non-education) doctorates: The case of an emerging Bhutan. High Educ. 2020 , 80 , 1081–1102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Naito, T.; Zhao, L.X. Capital accumulation through studying abroad and return migration. Econ. Model. 2020 , 87 , 185–196. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Kahn, M.; Gamedze, T.; Oghenetega, J. Mobility of sub-Saharan Africa doctoral graduates from South African universities—A tracer study. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2019 , 68 , 9–14. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kramer, B.; Zent, R. Diaspora linkages benefit both sides: A single partnership experience. Glob. Health Action 2019 , 12 , 1645558. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Li, W.; Lo, L.; Lu, Y.X.; Tan, Y.N.; Lu, Z. Intellectual migration: Considering China. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Varma, A.; Tung, R. Lure of country of origin: An exploratory study of ex-host country nationals in India. Pers. Rev. 2020 , 49 , 1487–1501. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X. The geopolitics of knowledge circulation: The situated agency of mimicking in/beyond China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Manic, M. The regional effects of international migration on internal migration decisions of tertiary-educated workers. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019 , 98 , 1027. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dzuverovic, N.; Tepsic, G. Neoliberal co-optation, power relations and informality in the Balkan International Relations profession. Int. Relat. 2020 , 34 , 84–104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Luczaj, K. Foreign-born scholars in Central Europe: A planned strategy or a ‘dart throw’? J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020 , 42 , 602–616. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dustmann, C.; Preston, I.P. Free Movement, Open Borders, and the Global Gains from Labor Mobility. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2019 , 11 , 783–808. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Bu, Y.; Li, J. Does the mobility of scientists disrupt their collaboration stability? J. Inf. Sci. 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Teasley, S.; Wolinsky, S. Scientific Collaborations at a Distance. Science 2001 , 292 , 2254–2255. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Shoemaker, R. Soil-test biological activity with the flush of CO 2 : VI. Economics of optimized nitrogen inputs for corn. Agron. J. 2020 , 112 , 2848–2865. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wartman, J.; Berman, J.W.; Bostrom, A.; Miles, S.; Olsen, M.; Gurley, K.; Irish, J.; Lowes, L.; Tanner, T.; Dafni, J.; et al. Research Needs, Challenges, and Strategic Approaches for Natural Hazards and Disaster Reconnaissance. Front. Built Environ. 2020 , 6 , 573068. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Syed, M.H.; Guillo-Sansano, E.; Wang, Y.; Vogel, S.; Palensky, P.; Burt, G.M.; Xu, Y.; Monti, A.; Hovsapian, R. Real-Time Coupling of Geographically Distributed Research Infrastructures: Taxonomy, Overview and Real-World Smart Grid Applications. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2020 . [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Type of Data | Unit of Analysis | Analytical Methods | Presentations of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Year | Article | Exponential regression | Linear and shadow graph |

| Author | Article | Price’s Law | Table |

| Journal | Article | Bradford’s Law | Table |

| WoS Category | Article (Journal) | Counting and proportionality | Table |

| Citation article | Article | Hirsch index | Relational graph |

| Affiliation, Author, Keywords plus | Article | Counting, co-authorship and co-occurrence | Relational graph |

| Terms | Article (Title and abstract) | Counting and co-occurrence | Relational graph |

| Web of Science Categories | ID | 1965–1974 | 1975–1984 | 1985–1994 | 1995–2004 | 2005–2014 | >= 2015 | Articles | % of Contribution at 1212 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economics | WC01 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 24 | 211 | 137 | 391 | 32.3% |

| Demography | WC02 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 17 | 52 | 47 | 130 | 10.7% |

| Education & Educational Research | WC03 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 31 | 32 | 91 | 7.5% |

| Management | WC04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 46 | 38 | 87 | 7.2% |

| Geography | WC05 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 38 | 37 | 78 | 6.4% |

| Public, Environmental & Occupational Health | WC06 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 38 | 28 | 77 | 6.4% |

| Development Studies | WC07 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 33 | 22 | 70 | 5.8% |

| Environmental Studies | WC08 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 28 | 59 | 4.9% |

| Regional Urban Planning | WC09 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 25 | 20 | 58 | 4.8% |

| Health Policy & Services | WC10 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 32 | 17 | 57 | 4.7% |

| Industrial Relations Labor | WC11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 22 | 52 | 4.3% |

| Sociology | WC12 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 47 | 3.9% |

| Political Science | WC13 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 20 | 8 | 46 | 3.8% |

| Information Science & Library Science | WC14 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 18 | 45 | 3.7% |

| Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | WC15 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 41 | 3.4% |

| International Relations | WC16 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 13 | 12 | 39 | 3.2% |

| Health Care Sciences Services | WC17 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 27 | 5 | 38 | 3.1% |

| Business | WC18 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 15 | 37 | 3.1% |

| Business, Finance | WC19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17 | 13 | 36 | 3.0% |

| Social Sciences, Biomedical | WC20 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 14 | 12 | 33 | 2.7% |

| Area Studies | WC21 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 8 | 28 | 2.3% |

| Computer Science, Interdisciplinary Applications | WC22 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 27 | 2.2% |

| Ethics | WC23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 11 | 25 | 2.1% |

| Urban Studies | WC24 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 24 | 2.0% |

| Total in selection categories (% of contribution at 1212) | 5% | 3% | 5% | 10% | 62% | 48% |

| Zone | Articles (%) | Journals (%) | Bradford Multipliers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | 406 | (33%) | 33 | (6%) | |

| 1 | 399 | (33%) | 119 | (23%) | 3.6 |

| 2 | 407 | (34%) | 374 | (71%) | 3.1 |

| Total | 167 | 526 | 3.4 | ||

| Journal | 1965–1974 | 1975–1984 | 1985–1994 | 1995–2004 | 2005–2014 | >=2015 | Total | Contribution% Over 406 | WoS Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 22 | 13 | 57 | 14.04 | Demography | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 4 | 30 | 7.39 | Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 24 | 5.92 | Computer Science, Interdisciplinary Applications; Information Science and Library Science | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 24 | 5.92 | Health Policy and Services; Industrial Relations and Labor | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 3.45 | Demography; Economics | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 3.21 | Public, Environmental and Occupational Health; Social Sciences, Biomedical | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 3.21 | Development Studies; Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 13 | 3.21 | Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 2.96 | Demography; Geography | |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 2.71 | Demography | |

| 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 2.71 | Education and Educational Research | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 2.71 | Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 2.47 | Business, Finance; Development Studies; Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 2.47 | Business, Finance; Economics; International Relations | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 2.47 | Management | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 10 | 2.47 | Development Studies; Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 2.47 | Management | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 2.22 | Demography; Ethnic Studies | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 2.22 | Economics; Environmental Studies; Geography; Regional and Urban Planning | |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1.98 | Development Studies; International Relations; Political Science | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 1.98 | Sociology | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 1.98 | Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 1.98 | Economics; Environmental Studies; Geography; Regional and Urban Planning | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.98 | Industrial Relations and Labor; Management | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 1.98 | Development Studies; Economics; Urban Studies | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 1.98 | Health Care Sciences and Services | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 1.73 | Area Studies | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 1.73 | Economics; Environmental Studies; Urban Studies | |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 1.73 | Education and Educational Research; History and Philosophy of Science; Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 1.73 | Education and Educational Research | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 1.73 | Economics | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 1.73 | Health Care Sciences and Services; Health Policy and Services | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1.73 | Health Care Sciences and Services; Health Policy and Services | |

| Total Nucleus | 8 | 11 | 20 | 41 | 194 | 132 | 406 | 100 |

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Vega-Muñoz, A.; Gónzalez-Gómez-del-Miño, P.; Espinosa-Cristia, J.F. Recognizing New Trends in Brain Drain Studies in the Framework of Global Sustainability. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063195

Vega-Muñoz A, Gónzalez-Gómez-del-Miño P, Espinosa-Cristia JF. Recognizing New Trends in Brain Drain Studies in the Framework of Global Sustainability. Sustainability . 2021; 13(6):3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063195

Vega-Muñoz, Alejandro, Paloma Gónzalez-Gómez-del-Miño, and Juan Felipe Espinosa-Cristia. 2021. "Recognizing New Trends in Brain Drain Studies in the Framework of Global Sustainability" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063195

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, supplementary material.

XLSX-Document (XLSX, 2499 KiB)

Further Information

Mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

Page Not Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try using the search box below or click on the homepage button to go there.

Brain drain: what is the role of institutions?

- Published: 30 November 2023

Cite this article

- Fanyu Chen 1 ,

- Zi Wen Vivien Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6362-3166 1 &

- Siong Hook Law 2

222 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Brain drain is closely associated with human capital deficiencies and obstacles in economic development. In spite of its crucial economic implications, nations, especially the developing ones, have failed to prevent brain drain due to the focus on simple restrictive policies and the ignorance of institutional factors like weakly-enforced law and order, unfulfilled basic human rights, and others in preventing the outflow high skilled labor. Thus, this paper aims to investigate the impact of institutional quality on brain drain in 100 countries from 2007 to 2019, using system Generalized Method of Moments estimator to estimate the model involving data collected from the International Country Risk Guide, The Quality of Government Institute, and the World Bank. The empirical results indicated that quality of institutions is essential in preventing the outflow of highly skilled workers. It has become imperative for policy-makers in these countries to uphold and strengthen their nations’ institutional frameworks in order to retain and attract the valuable talents to stay on and reside in their own countries.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Macroeconomic determinants of emigration from India to the United States

Brain drain and income distribution.

Brain Drain

Agbola, F. W., & Acupan, A. B. (2010). An empirical analysis of international labour migration in the Philippines. Economic Systems , 34 (4), 386–396.

Article Google Scholar

Aidt, T. S. (2003). Economic analysis of corruption: A survey. The Economic Journal , 113 (491), F632–F652.

Akdede, S. H. (2010). Do more ethnically and religiously diverse countries have lower democratization? Economics Letters , 106 (2), 101–104.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies , 58 (2), 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics , 68 (1), 29–51.

Ariu, A., Docquier, F., & Squicciarini, M. P. (2016). Governance quality and net migration flows. Regional Science and Urban Economics , 60 , 238–248.

Ashby, N. J. (2010). Freedom and international migration. Southern Economic Journal , 77 (1), 49–62.

Bailey, A., & Mulder, C. H. (2017). Highly skilled migration between the Global North and South: Gender, life courses and institutions. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 43 (16), 2689–2703.

Bang, J. T., & Mitra, A. (2011). Brain drain and institutions of governance: Educational attainment of immigrants to the US 1988–1998. Economic Systems , 35 (3), 335–354.

Baudassé, T., Bazillier, R., & Issifou, I. (2018). Migration and institutions: Exit and voice (from abroad)? Journal of Economic Surveys , 32 (3), 727–766.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital . Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Becker, S. O., & Woessmann, L. (2008). Luther and the girls: Religious denomination and the female education gap in nineteenth-century Prussia. Scandinavian Journal of Economics , 110 (4), 777–805.

Beine, M., Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2001). Brain drain and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics , 64 (1), 275–289.

Beine, M. A., Docquier, F., & Schiff, M. (2008). Brain Drain and its Determinants: A Major Issue for small states.

Beine, M., Docquier, F., & Oden-Defoort, C. (2011). A panel data analysis of the brain gain. World Development , 39 (4), 523–532.

Beine, M., Noel, R., & Ragot, L. (2014). Determinants of the international mobility of students. Economics of Education Review , 41 , 40–54.

Bertocchi, G., & Strozzi, C. (2008). International migration and the role of institutions. Public Choice , 137 (1–2), 81–102.

Bessey, D. (2012). International student migration to Germany. Empirical Economics , 42 (1), 345–361.

Bhattacharyya, S. (2009). Unbundled institutions, human capital and growth. Journal of Comparative Economics , 37 (1), 106–120.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics , 87 (1), 115–143.

Botticini, M., & Eckstein, Z. (2007). From farmers to merchants, conversions and diaspora: Human capital and Jewish history. Journal of the European Economic Association , 5 (5), 885–926.

Boucher, A., & Cerna, L. (2014). Current policy trends in skilled immigration policy. International Migration , 52 (3), 21–25.

Cattaneo, C. (2009). International Migration, the Brain Drain and Poverty: A cross-country analysis. World Economy , 32 (8), 1180–1202.

Cebula, R. J. (2002). Migration and the Tiebout-Tullock hypothesis revisited. The Review of Regional Studies , 32 (1), 87–96.

Cerna, L. (2014). Attracting high-skilled immigrants: Policies in comparative perspective. International Migration , 52 (3), 69–84.

Chaudhary, L., & Rubin, J. (2011). Reading, writing, and religion: Institutions and human capital formation. Journal of Comparative Economics , 39 (1), 17–33.

Clemens, M. A. (2009). Skill flow: A fundamental reconsideration of skilled-worker mobility and development. Available at SSRN 1477129 .

Cooray, A., & Schneider, F. (2016). Does corruption promote emigration? An empirical examination. Journal of Population Economics , 29 (1), 293–310.

Cumming, D., Glatzer, Z., & Guedhami, O. (2023). Institutions, digital assets, and implications for economic and financial performance. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics , 1–27.

Datta, K. (2009). Transforming south–north relations? International migration and development. Geography Compass , 3 (1), 108–134.

Demetriades, P., & Law, S. H. (2006). Finance, institutions and economic development. International Journal of Finance and Economics , 11 (3), 245–258.

Dias, J., & Tebaldi, E. (2012). Institutions, human capital, and growth: The institutional mechanism. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics , 23 (3), 300–312.

Dimant, E., Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2013). The effect of corruption on migration, 1985–2000. Applied Economics Letters , 20 (13), 1270–1274.

Docquier, F., & Marfouk, A. (2006). International migration by education attainment, 1990–2000. International migration, remittances and the brain drain , 151–199.

Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2003). Ethnic discrimination and the migration of skilled labor. Journal of Development Economics , 70 (1), 159–172.

Docquier, F., Lohest, O., & Marfouk, A. (2007). Brain drain in developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review , 21 (2), 193–218.

Dreher, A., Krieger, T., & Meierrieks, D. (2011). Hit and (they will) run: The impact of Terrorism on migration. Economics Letters , 113 (1), 42–46.

Dreze, J., & Sen, A. (1999). India: Economic development and social opportunity. OUP Catalogue .

Dustmann, C., Fadlon, I., & Weiss, Y. (2011). Return migration, human capital accumulation and the brain drain. Journal of Development Economics , 95 (1), 58–67.

Dutta, N., & Roy, S. (2011). Do potential skilled emigrants Care about Political Stability at Home? Review of Development Economics , 15 (3), 442–457.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2006). Das human-kapital: A theory of the demise of the class structure. The Review of Economic Studies , 73 (1), 85–117.

Gibson, J., & McKenzie, D. (2011). Eight questions about brain drain. The Journal of Economic Perspectives , 25 (3), 107–128.

Grogger, J., & Hanson, G. H. (2011). Income maximization and the selection and sorting of international migrants. Journal of Development Economics , 95 (1), 42–57.

Harnoss, J. D. (2017). Economic costs of the Malaysian brain drain: Implications from an endogenous growth model. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies , 48 (2), 117–130.

Google Scholar

Harvey, W. S. (2008). Strong or weak ties? British and Indian expatriate scientists finding jobs in Boston. Global Networks , 8 (4), 453–473.

Ibrahim, M. H., & Law, S. H. (2016). Institutional quality and CO2 Emission–Trade relations: Evidence from Sub-saharan A frica. South African Journal of Economics , 84 (2), 323–340.

Jong-A-Pin, R. (2009). On the measurement of political instability and its impact on economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy , 25 (1), 15–29.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido, P. (1999). Governance matters. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper , (2196).

Law, S. H., Azman-Saini, W. N. W., & Ibrahim, M. H. (2013). Institutional quality thresholds and the finance–growth nexus. Journal of Banking & Finance , 37 (12), 5373–5381.

Marra, A., & Colantonio, E. (2022). The institutional and socio-technical determinants of renewable energy production in the EU: Implications for policy. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics , 49 (2), 267–299.

McKenzie, D., & Rapoport, H. (2010). Self-selection patterns in Mexico-US migration: The role of migration networks. The Review of Economics and Statistics , 92 (4), 811–821.

Nejad, M. N., & Young, A. T. (2016). Want freedom, will travel: Emigrant self-selection according to institutional quality. European Journal of Political Economy , 45 , 71–84.

Ngoma, A. L., & Ismail, N. W. (2013). The impact of Brain Drain on human capital in developing countries. South African Journal of Economics , 81 (2), 211–224.

Nguyen, C. P., Quang, N., B., & Su, T. D. (2023). Institutional frameworks and the shadow economy: New evidence of colonial history, Socialist history, religion, and legal systems. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics , 1–29.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 5 (1), 97–112.

Ortega, F., & Peri, G. (2013). The role of income and immigration policies in attracting international migrants. Migration Studies , 1 , 47–74.

Peng, B. (2009). Rent-seeking activities and the ‘brain gain’effects of migration. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique , 42 (4), 1561–1577.

Poprawe, M. (2015). On the relationship between corruption and migration: Empirical evidence from a gravity model of migration. Public Choice , 163 (3–4), 337–354.

Rajan, R. G. (2009). Rent preservation and the persistence of underdevelopment. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics , 1 (1), 178–218.

Rao, G. L. (1979). Brain drain and foreign students: a study of the attitudes and intentions of foreign students in Australia the USA Canada and France. Studies in society and culture .

Rodrik, D. (2000). Institutions for high-quality growth: what they are and how to acquire them? Studies in Comparative International Development, Fall 2000, 35 (3), 3–31.

Rodrik, D. (2005). Growth strategies. Handbook of Economic Growth , 1 , 967–1014.

Sager, A. (2014). Reframing the brain drain. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy , 17 (5), 560–579.

Sager, A. (2020). Against Borders: Why the World needs Free Movement of people . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Schultz, T. W. (1964). Transforming traditional agriculture. Transforming Traditional Agriculture Sciences , 13 (1), 38–45.

Steinberg, D. (2017). Resource shocks and human capital stocks–brain drain or brain gain? Journal of Development Economics , 127 , 250–268.

Stolz, Y., & Baten, J. (2012). Brain drain in the age of mass migration: Does relative inequality explain migrant selectivity? Explorations in Economic History , 49 (2), 205–220.

Tessema, M. (2010). Causes, challenges and prospects of brain drain: The case of Eritrea. International Migration , 48 (3), 131–151.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy , 64 (5), 416–424.

Tomasi, C., Pieri, F., & Cecco, V. (2023). Red tape and industry dynamics: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Industrial and Business Economics , 1–38.

Tullock, G. (1971). Public decisions as public goods. Journal of Political Economy , 79 (4), 913–918.

Varma, R., & Kapur, D. (2013). Comparative analysis of brain drain, brain circulation and brain retain: A case study of Indian institutes of technology. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice , 15 (4), 315–330.

World Bank. (2016). Taking on inequality (poverty and shared prosperity 2016) . Author.

World Bank, Europe and Central Asia Economic Update. (2019). Migration and Brain Drain . Author.

Zweig, D. (1997). To return or not to return? Politics vs. economics in China’s brain drain. Studies in Comparative International Development , 32 (1), 92–125.

Zweig, D. (2006). Competing for talent: China’s strategies to reverse the brain drain. International Labour Review , 145 (1-2), 65–90.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Business and Finance, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Perak, Malaysia

Fanyu Chen & Zi Wen Vivien Wong

School of Business and Economics, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

Siong Hook Law

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zi Wen Vivien Wong .

Ethics declarations

Competing interest.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chen, F., Wong, Z.W.V. & Law, S.H. Brain drain: what is the role of institutions?. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-023-00286-w

Download citation

Received : 24 April 2023

Revised : 14 November 2023

Accepted : 19 November 2023

Published : 30 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40812-023-00286-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Institutions

- Brain drain

- Human Capital

- Economic Development

- Generalized method of moments Estimator

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Cookie settings

These necessary cookies are required to activate the core functionality of the website. An opt-out from these technologies is not available.

In order to further improve our offer and our website, we collect anonymous data for statistics and analyses. With the help of these cookies we can, for example, determine the number of visitors and the effect of certain pages on our website and optimize our content.

Selecting your areas of interest helps us to better understand our audience.

- Subject areas

The brain drain from developing countries

The brain drain produces many more losers than winners in developing countries

Université Catholique de Louvain, and National Fund for Scientific Research, Belgium, and IZA, Germany

Elevator pitch

The proportion of foreign-born people in rich countries has tripled since 1960, and the emigration of high-skilled people from poor countries has accelerated. Many countries intensify their efforts to attract and retain foreign students, which increases the risk of brain drain in the sending countries. In poor countries, this transfer can change the skill structure of the labor force, cause labor shortages, and affect fiscal policy, but it can also generate remittances and other benefits from expatriates and returnees. Overall, it can be a boon or a curse for developing countries, depending on the country’s characteristics and policy objectives.

Key findings

The income-maximizing level of a brain drain is usually positive in developing countries, meaning that some emigration of the more skilled is beneficial.

A brain drain stimulates education, induces remittance flows, reduces international transaction costs, and generates benefits in source countries from both returnees and the diaspora abroad.

Appropriate policy adjustments, which depend on the characteristics and policy objectives of the source country, can help to maximize the gains or minimize the costs of the brain drain.

The effective brain drain exceeds the income-maximizing level in the vast majority of developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and small countries.

A brain drain may cause fiscal losses.

Above a certain level, brain drain reduces the stock of human capital and induces occupational distortions.

Author's main message

The impact of the brain drain on a source country’s welfare and development can be beneficial or harmful. The evidence suggests that there are many more losers than winners among developing countries. Whether a country gains or loses depends on country-specific factors, such as the level and composition of migration, the country’s level of development, and such characteristics as population size, language, and geographic location. Policymakers should gauge the costs and benefits of the brain drain in order to design appropriate policy responses.

The term “brain drain” refers to the international transfer of human capital resources, and it applies mainly to the migration of highly educated individuals from developing to developed countries. In lay usage, the term is generally used in a narrower sense and relates more specifically to the migration of engineers, physicians, scientists, and other very high-skilled professionals with university training, often between developed countries.

Although a concern for rich countries, the brain drain has long been viewed as a serious constraint on the development of poor countries. Comparative data reveal that by 2000 there were 20 million high-skilled immigrants (foreign-born workers with higher education) living in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a 70% increase in ten years. Two-thirds of these high-skilled immigrants came from developing and transition countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

Key trends in high-skilled migration.

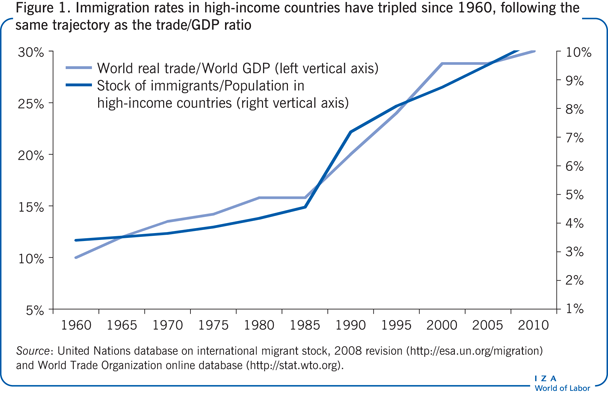

According to the United Nations Global Migration Database, the number of international migrants increased from 75 million in 1960 to 214 million in 2010. This about parallels the growth in the world population, so the world migration rate increased only slightly in relative terms, from 2.5% to 3.1% of the world population. The major part of this change is artificial and due to the break-up of the former Soviet Union, when what was once the internal movement of workers became reclassified as international migration after 1990. Overall, the share of international migrants in the world population has been stable for the last 50 years.

But the picture changes when the focus is narrowed to migration to developed countries. The proportion of international migrants residing in high-income countries relative to the total in all possible destinations increased from 43% to 60% between 1960 and 2010. As measured by the proportion of the foreign-born in the total population of high-income countries, the average immigration rate to these countries has tripled since 1960 and doubled since 1985. The increase has followed the same trajectory as the ratio of trade to gross domestic product (GDP) (see Figure 1 ).

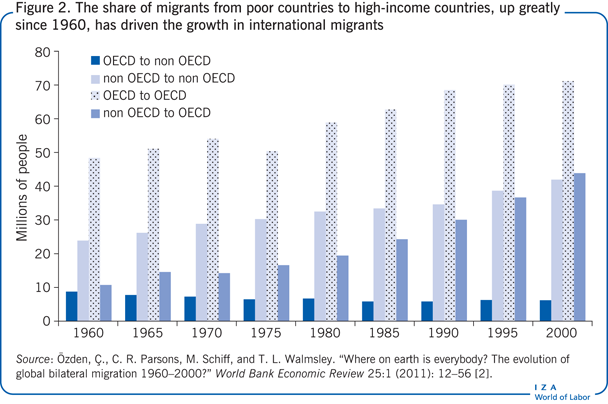

More of these migrants are coming from non-OECD countries. Indeed, a database of global bilateral migration published in 2011 reveals that as of 2000, migration between developing countries still dominated the global migrant stock: at 72.6 million people, migration between developing countries constituted about 45% of all international migration (see Figure 2 ) [2] . Next came migration from developing to developed countries (55 million, 34% of all migrants) and then migration between developed countries (28 million, 17%). But the growth in the number of migrants was driven largely by emigration from developing countries to developed countries, which increased from ten million to 55 million between 1960 and 2000, faster than trade.

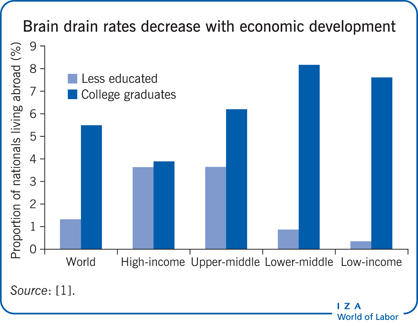

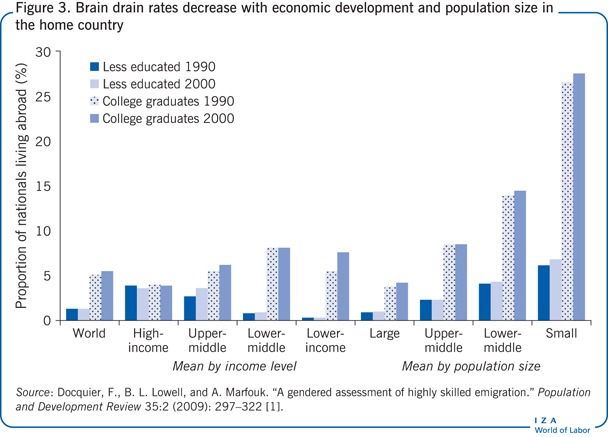

Emigration rates of high-skilled workers exceed those of low-skill workers in virtually all countries (see Figure 3 ) [1] . The skill bias in emigration rates is particularly pronounced in low-income countries (see What drives the brain drain, and how can we quantify it? ). The largest brain drain rates are observed in small, poor countries in the tropics, and they rise over the 1990s. The worst-affected countries see more than 80% of their “brains” emigrating abroad, such as for Haiti, Jamaica, and several small states with fewer than one million workers. About 20 other countries are losing between one-third and one-half of their college graduates. Most are in sub-Saharan Africa (such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Somalia) or Asia (such as Afghanistan and Cambodia). A few are small, high-income countries (such as Hong Kong and Ireland).

Expected adverse and beneficial effects of skilled migration

The brain drain has long been viewed as detrimental to the growth potential of the home country and the welfare of those left behind. It is usually expected to be even more harmful for the least developed countries because, as explained above, with increasing development, positive selection in emigration and brain drain rates fall.

A brain drain can also have benefits for home countries. Alongside positive feedback effects from remittances, circular migration, and the participation of high-skilled migrants in business networks, innovation, and transfers of technology, consider the effect of migration prospects on the formation of human capital in home countries. New research suggests that limited high-skilled emigration can be beneficial for growth and development, especially for a limited number of large, middle-income developing countries. But for the vast majority of poor and small developing countries, skilled emigration rates significantly exceed the optimal rate (see Terms used in migration studies ).

The broad diversity of brain drain effects on development has been illustrated in case studies. The contribution of expatriate Indian engineers and information technology professionals to the Indian growth miracle has been recognized. But the medical brain drain from sub-Saharan Africa has been detrimental. A brain drain can also generate both beneficial and adverse effects for long-term development—as with the emigration of Filipino nurses to the US or Egyptian teachers to Arab states in the Persian Gulf.

Adverse effects

The social returns to human capital are likely to exceed its private returns given the many externalities, both technological and sociological (see Terms used in migration studies ). This externality argument has been central in the literature since the 1970s, and the seminal contribution on this subject concludes that the brain drain entails significant losses for those left behind and increases global inequality [3] .

Another cost is that high-skilled emigrants do not pay taxes in their home country once they have left. As education is partly or totally subsidized by the government, emigrants leave before they can repay their debt to society. This fiscal cost may be reinforced by governments distorting the provision of public education away from general (portable) skills when graduates leave, with the country perhaps ending up educating too many lawyers and too few nurses, doctors, or engineers.

A third negative effect is inducing shortages of manpower in key activities, as when engineers or health professionals emigrate in disproportionately large numbers, undermining a country’s ability to adopt new technologies or deal with health crises.

Fourth, the brain drain increases the technological gap between leading and developing nations because the concentration of human capital in the most advanced economies contributes to their technological progress.

Ambiguous effect on the educational and occupational structure of the labor force

The argument can, however, be reversed because uncertainty about the prospects for migration may create a bias in the opposite direction. When education is seen as a passport to emigration, this creates additional incentives to undertake further education. But if young people are uncertain about their chances of future migration when they make education decisions, this can be turned into a gain for the home country under certain circumstances [4] , [5] .

Case studies on the “brain gain” hypothesis

In Tonga and Papua New Guinea, nearly all (85%) of the very top high school students contemplate emigration while still in high school; this leads them to take additional classes and make changes to their course choices in favor of fields such as science and commerce [6] . In Cape Verde, emigration prospects are among the main drivers of human capital formation [7] . In Fiji, the educational attainment of ethnic Fijians has been compared with that of Fijians of Indian ancestry in the aftermath of the 1987 military coup, which resulted in physical violence and discriminatory policies against the Indian minority [8] . For the latter, the correlation was strong between changes in emigration prospects and human capital investments.

Other studies have not found evidence of a brain gain. This is so for the brain drain of physicians from sub-Saharan Africa, where limited training capacities prevent students from responding to incentives, or migration from Mexico to the US, where there is a bias toward low-skill workers in emigration prospects.

From a development perspective, however, what matters is not how many of a country’s native-born engage in higher education, but how many of those who do engage remain at home. The brain drain can benefit a home country if it increases the proportion of college graduates in the population remaining. There are two conditions for such a benefit to obtain. First, the level of development in the country should be low enough to generate strong incentives for the more educated to emigrate, but not so low that personal liquidity constraints on investment in education become strongly limiting (in which case the incentive cannot operate). Second, the probability of emigration by high-skilled workers must be sufficiently low—for example, below 15–20%. On average, the level of brain drain that maximizes human capital accumulation in a developing country is around 10%. This level varies across countries, depending on their size, location, language, and public policies. In particular, it declines with development and the effectiveness of the higher education system.