- Privacy Policy

Home » Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Focus Group

Definition:

A focus group is a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights and opinions from a group of individuals about a particular product, service, concept, or idea.

The focus group typically consists of 6-10 participants who are selected based on shared characteristics such as demographics, interests, or experiences. The discussion is moderated by a trained facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes towards the topic.

Focus groups are an effective way to gather detailed information about consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions, and can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Types of Focus Group

The following are some types or methods of Focus Groups:

Traditional Focus Group

This is the most common type of focus group, where a small group of people is brought together to discuss a particular topic. The discussion is typically led by a skilled facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions.

Mini Focus Group

A mini-focus group involves a smaller group of participants, typically 3 to 5 people. This type of focus group is useful when the topic being discussed is particularly sensitive or when the participants are difficult to recruit.

Dual Moderator Focus Group

In a dual-moderator focus group, two facilitators are used to manage the discussion. This can help to ensure that the discussion stays on track and that all participants have an opportunity to share their opinions.

Teleconference or Online Focus Group

Teleconferences or online focus groups are conducted using video conferencing technology or online discussion forums. This allows participants to join the discussion from anywhere in the world, making it easier to recruit participants and reducing the cost of conducting the focus group.

Client-led Focus Group

In a client-led focus group, the client who is commissioning the research takes an active role in the discussion. This type of focus group is useful when the client has specific questions they want to ask or when they want to gain a deeper understanding of their customers.

The following Table can explain Focus Group types more clearly

How To Conduct a Focus Group

To conduct a focus group, follow these general steps:

Define the Research Question

Identify the key research question or objective that you want to explore through the focus group. Develop a discussion guide that outlines the topics and questions you want to cover during the session.

Recruit Participants

Identify the target audience for the focus group and recruit participants who meet the eligibility criteria. You can use various recruitment methods such as social media, online panels, or referrals from existing customers.

Select a Venue

Choose a location that is convenient for the participants and has the necessary facilities such as audio-visual equipment, seating, and refreshments.

Conduct the Session

During the focus group session, introduce the topic, and review the objectives of the research. Encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions by asking open-ended questions and probing deeper into their responses. Ensure that the discussion remains on topic and that all participants have an opportunity to contribute.

Record the Session

Use audio or video recording equipment to capture the discussion. Note-taking is also essential to ensure that you capture all key points and insights.

Analyze the data

Once the focus group is complete, transcribe and analyze the data. Look for common themes, patterns, and insights that emerge from the discussion. Use this information to generate insights and recommendations that can be applied to the research question.

When to use Focus Group Method

The focus group method is typically used in the following situations:

Exploratory Research

When a researcher wants to explore a new or complex topic in-depth, focus groups can be used to generate ideas, opinions, and insights.

Product Development

Focus groups are often used to gather feedback from consumers about new products or product features to help identify potential areas for improvement.

Marketing Research

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or advertising campaigns to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Customer Feedback

Focus groups can be used to gather feedback from customers about their experiences with a particular product or service, helping companies improve customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Public Policy Research

Focus groups can be used to gather public opinions and attitudes on social or political issues, helping policymakers make more informed decisions.

Examples of Focus Group

Here are some real-time examples of focus groups:

- A tech company wants to improve the user experience of their mobile app. They conduct a focus group with a diverse group of users to gather feedback on the app’s design, functionality, and features. The focus group consists of 8 participants who are selected based on their age, gender, ethnicity, and level of experience with the app. During the session, a trained facilitator asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions on the app. The facilitator also observes the participants’ behavior and reactions to the app’s features. After the focus group, the data is analyzed to identify common themes and issues raised by the participants. The insights gathered from the focus group are used to inform improvements to the app’s design and functionality, with the goal of creating a more user-friendly and engaging experience for all users.

- A car manufacturer wants to develop a new electric vehicle that appeals to a younger demographic. They conduct a focus group with millennials to gather their opinions on the design, features, and pricing of the vehicle.

- A political campaign team wants to develop effective messaging for their candidate’s campaign. They conduct a focus group with voters to gather their opinions on key issues and identify the most persuasive arguments and messages.

- A restaurant chain wants to develop a new menu that appeals to health-conscious customers. They conduct a focus group with fitness enthusiasts to gather their opinions on the types of food and drinks that they would like to see on the menu.

- A healthcare organization wants to develop a new wellness program for their employees. They conduct a focus group with employees to gather their opinions on the types of programs, incentives, and support that would be most effective in promoting healthy behaviors.

- A clothing retailer wants to develop a new line of sustainable and eco-friendly clothing. They conduct a focus group with environmentally conscious consumers to gather their opinions on the design, materials, and pricing of the clothing.

Purpose of Focus Group

The key objectives of a focus group include:

Generating New Ideas and insights

Focus groups are used to explore new or complex topics in-depth, generating new ideas and insights that may not have been previously considered.

Understanding Consumer Behavior

Focus groups can be used to gather information on consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions to inform marketing and product development strategies.

Testing Concepts and Ideas

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or product prototypes to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Gathering Customer Feedback

Informing decision-making.

Focus groups can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Advantages of Focus Group

The advantages of using focus groups are:

- In-depth insights: Focus groups provide in-depth insights into the attitudes, opinions, and behaviors of a target audience on a specific topic, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the issues being explored.

- Group dynamics: The group dynamics of focus groups can provide additional insights, as participants may build on each other’s ideas, share experiences, and debate different perspectives.

- Efficient data collection: Focus groups are an efficient way to collect data from multiple individuals at the same time, making them a cost-effective method of research.

- Flexibility : Focus groups can be adapted to suit a range of research objectives, from exploratory research to concept testing and customer feedback.

- Real-time feedback: Focus groups provide real-time feedback on new products or concepts, allowing researchers to make immediate adjustments and improvements based on participant feedback.

- Participant engagement: Focus groups can be a more engaging and interactive research method than surveys or other quantitative methods, as participants have the opportunity to express their opinions and interact with other participants.

Limitations of Focus Groups

While focus groups can provide valuable insights, there are also some limitations to using them.

- Small sample size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, which may not be representative of the broader population being studied.

- Group dynamics : While group dynamics can be an advantage of focus groups, they can also be a limitation, as dominant personalities may sway the discussion or participants may not feel comfortable expressing their true opinions.

- Limited generalizability : Because focus groups involve a small sample size, the results may not be generalizable to the broader population.

- Limited depth of responses: Because focus groups are time-limited, participants may not have the opportunity to fully explore or elaborate on their opinions or experiences.

- Potential for bias: The facilitator of a focus group may inadvertently influence the discussion or the selection of participants may not be representative, leading to potential bias in the results.

- Difficulty in analysis : The qualitative data collected in focus groups can be difficult to analyze, as it is often subjective and requires a skilled researcher to interpret and identify themes.

Characteristics of Focus Group

- Small group size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, ranging from 6 to 12 people. This allows for a more in-depth and focused discussion.

- Targeted participants: Participants in focus groups are selected based on specific criteria, such as age, gender, or experience with a particular product or service.

- Facilitated discussion: A skilled facilitator leads the discussion, asking open-ended questions and encouraging participants to share their thoughts and experiences.

- I nteractive and conversational: Focus groups are interactive and conversational, with participants building on each other’s ideas and responding to one another’s opinions.

- Qualitative data: The data collected in focus groups is qualitative, providing detailed insights into participants’ attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

- Non-threatening environment: Participants are encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences in a non-threatening and supportive environment.

- Limited time frame: Focus groups are typically time-limited, lasting between 1 and 2 hours, to ensure that the discussion stays focused and productive.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

What Is a Focus Group?

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A focus group is a qualitative research method that involves facilitating a small group discussion with participants who share common characteristics or experiences that are relevant to the research topic. The goal is to gain insights through group conversation and observation of dynamics.

In a focus group:

- A moderator asks questions and leads a group of typically 6 to 12 pre-screened participants through a discussion focused on a particular topic.

- Group members are encouraged to talk with one another, exchange anecdotes, comment on each others’ experiences and points of view, and build on each others’ responses.

- The goal is to create a candid, natural conversation that provides insights into the participants’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on the topic.

- Focus groups capitalize on group dynamics to elicit multiple perspectives in a social environment as participants are influenced by and influence others through open discussion.

- The interactive responses allow researchers to quickly gather more contextual, nuanced qualitative data compared to surveys or one-on-one interviews.

Focus groups allow researchers to gather perspectives from multiple people at once in an interactive group setting. This group dynamic surfaces richer responses as participants build on each other’s comments, discuss issues in-depth, and voice agreements or disagreements.

It is important that participants feel comfortable expressing diverse viewpoints rather than being pressured into a consensus.

Focus groups emerged as an alternative to questionnaires in the 1930s over concerns that surveys fostered passive responses or failed to capture people’s authentic perspectives.

During World War II, focus groups were used to evaluate military morale-boosting radio programs. By the 1950s focus groups became widely adopted in marketing research to test consumer preferences.

A key benefit K. Merton highlighted in 1956 was grouping participants with shared knowledge of a topic. This common grounding enables people to provide context to their experiences and allows contrasts between viewpoints to emerge across the group.

As a result, focus groups can elicit a wider range of perspectives than one-on-one interviews.

Step 1 : Clarify the Focus Group’s Purpose and Orientation

Clarify the purpose and orientation of the focus group (Tracy, 2013). Carefully consider whether a focus group or individual interviews will provide the type of qualitative data needed to address your research questions.

Determine if the interactive, fast-paced group discussion format is aligned with gathering perspectives vs. in-depth attitudes on a topic.

Consider incorporating special techniques like extended focus groups with pre-surveys, touchstones using creative imagery/metaphors to focus the topic, or bracketing through ongoing conceptual inspection.

For example

A touchstone in a focus group refers to using a shared experience, activity, metaphor, or other creative technique to provide a common reference point and orientation for grounding the discussion.

The purpose of Mulvale et al. (2021) was to understand the hospital experiences of youth after suicide attempts.

The researchers created a touchstone to focus the discussion specifically around the hospital visit. This provided a shared orientation for the vulnerable participants to open up about their emotional journeys.

In the example from Mulvale et al. (2021), the researchers designated the hospital visit following suicide attempts as the touchstone. This means:

- The visit served as a defining shared experience all youth participants could draw upon to guide the focus group discussion, since they unfortunately had this in common.

- Framing questions around recounting and making meaning out of the hospitalization focused the conversation to elicit rich details about interactions, emotions, challenges, supports needed, and more in relation to this watershed event.

- The hospital visit as a touchstone likely resonated profoundly across youth given the intensity and vulnerability surrounding their suicide attempts. This deepened their willingness to open up and established group rapport.

So in this case, the touchstone concentrated the dialogue around a common catalyst experience enabling youth to build understanding, voice difficulties, and potentially find healing through sharing their journey with empathetic peers who had endured the same trauma.

Step 2 : Select a Homogeneous Grouping Characteristic

Select a homogeneous grouping characteristic (Krueger & Casey, 2009) to recruit participants with a commonality, like shared roles, experiences, or demographics, to enable meaningful discussion.

A sample size of between 6 to 10 participants allows for adequate mingling (MacIntosh 1993).

More members may diminish the ability to capture all viewpoints. Fewer risks limited diversity of thought.

Balance recruitment across income, gender, age, and cultural factors to increase heterogeneity in perspectives. Consider screening criteria to qualify relevant participants.

Choosing focus group participants requires balancing homogeneity and diversity – too much variation across gender, class, profession, etc., can inhibit sharing, while over-similarity limits perspectives. Groups should feel mutual comfort and relevance of experience to enable open contributions while still representing a mix of viewpoints on the topic (Morgan 1988).

Mulvale et al. (2021) determined grouping by gender rather than age or ethnicity was more impactful for suicide attempt experiences.

They fostered difficult discussions by bringing together male and female youth separately based on the sensitive nature of topics like societal expectations around distress.

Step 3 : Designate a Moderator

Designate a skilled, neutral moderator (Crowe, 2003; Morgan, 1997) to steer productive dialogue given their expertise in guiding group interactions. Consider cultural insider moderators positioned to foster participant sharing by understanding community norms.

Define moderator responsibilities like directing discussion flow, monitoring air time across members, and capturing observational notes on behaviors/dynamics.

Choose whether the moderator also analyzes data or only facilitates the group.

Mulvale et al. (2021) designated a moderator experienced working with marginalized youth to encourage sharing by establishing an empathetic, non-judgmental environment through trust-building and active listening guidance.

Step 4 : Develop a Focus Group Guide

Develop an extensive focus group guide (Krueger & Casey, 2009). Include an introduction to set a relaxed tone, explain the study rationale, review confidentiality protection procedures, and facilitate a participant introduction activity.

Also include guidelines reiterating respect, listening, and sharing principles both verbally and in writing.

Group confidentiality agreement

The group context introduces distinct ethical demands around informed consent, participant expectations, confidentiality, and data treatment. Establishing guidelines at the outset helps address relevant issues.

Create a group confidentiality agreement (Berg, 2004) specifying that all comments made during the session must remain private, anonymous in data analysis, and not discussed outside the group without permission.

Have it signed, demonstrating a communal commitment to sustaining a safe, secure environment for honest sharing.

Berg (2004) recommends a formal signed agreement prohibiting participants from publicly talking about anything said in the focus group without permission. This reassures members their personal disclosures are safeguarded.

Develop questions starting general then funneling down to 10-12 key questions on critical topics. Integrate think/pair/share activities between question sets to encourage inclusion. Close with a conclusion to summarize key ideas voiced without endorsing consensus.

Krueger and Casey (2009) recommend structuring focus group questions in five stages:

Opening Questions:

- Start with easy, non-threatening questions to make participants comfortable, often related to their background and experience with the topic.

- Get everyone talking and open up initial dialogue.

- Example: “Let’s go around and have each person share how long you’ve lived in this city.”

Introductory Questions:

- Transition to the key focus group objectives and main topics of interest.

- Remain quite general to provide baseline understanding before drilling down.

- Example: “Thinking broadly, how would you describe the arts and cultural offerings in your community?”

Transition Questions:

- Serve as a logical link between introductory and key questions.

- Funnel participants toward critical topics guided by research aims.

- Example: “Specifically related to concerts and theatre performances, what venues in town have you attended events at over the past year?”

Key Questions:

- Drive at the heart of study goals, and issues under investigation.

- Ask 5-10 questions that foster organic, interactive discussion between participants.

- Example: “What enhances or detracts from the concert-going experience at these various venues?”

Ending Questions:

- Provide an opportunity for final thoughts or anything missed.

- Assess the degree of consensus on key topics.

- Example: “If you could improve just one thing about the concert and theatre options here, what would you prioritize?”

It is vital to extensively pilot test draft questions to hone the wording, flow, timing, tone and tackle any gaps to adequately cover research objectives through dynamic group discussion.

Step 5 : Prepare the focus group room

Prepare the focus group room (Krueger & Casey, 2009) attending to details like circular seating for eye contact, centralized recording equipment with backup power, name cards, and refreshments to create a welcoming, affirming environment critical for participants to feel valued, comfortable engaging in genuine dialogue as a collective.

Arrange seating comfortably in a circle to facilitate discussion flow and eye contact among members. Decide if space for breakout conversations or activities like role-playing is needed.

Refreshments

- Coordinate snacks or light refreshments to be available when focus group members arrive, especially for longer sessions. This contributes to a welcoming atmosphere.

- Even if no snacks are provided, consider making bottled water available throughout the session.

- Set out colorful pens and blank name tags for focus group members to write their preferred name or pseudonym when they arrive.

- Attaching name tags to clothing facilitates interaction and expedites learning names.

- If short on preparation time, prepare printed name tags in advance based on RSVPs, but blank name tags enable anonymity if preferred.

Krueger & Casey (2009) suggest welcoming focus group members with comfortable, inclusive seating arrangements in a circle to enable eye contact. Providing snacks and music sets a relaxed tone.

Step 6 : Conduct the focus group

Conduct the focus group utilizing moderation skills like conveying empathy, observing verbal and non-verbal cues, gently redirecting and probing overlooked members, and affirming the usefulness of knowledge sharing.

Use facilitation principles (Krueger & Casey, 2009; Tracy 2013) like ensuring psychological safety, mutual respect, equitable airtime, and eliciting an array of perspectives to expand group knowledge. Gain member buy-in through collaborative review.

Record discussions through detailed note-taking, audio/video recording, and seating charts tracking engaged participation.

The role of moderator

The moderator is critical in facilitating open, interactive discussion in the group. Their main responsibilities are:

- Providing clear explanations of the purpose and helping participants feel comfortable

- Promoting debate by asking open-ended questions

- Drawing out differences of opinion and a range of perspectives by challenging participants

- Probing for more details when needed or moving the conversation forward

- Keeping the discussion focused and on track

- Ensuring all participants get a chance to speak

- Remaining neutral and non-judgmental, without sharing personal opinions

Moderators need strong interpersonal abilities to build participant trust and comfort sharing. The degree of control and input from the moderator depends on the research goals and personal style.

With multiple moderators, roles, and responsibilities should be clear and consistent across groups. Careful preparation is key for effective moderation.

Mulvale et al. (2021) fostered psychological safety for youth to share intense emotions about suicide attempts without judgment. The moderator ensured equitable speaking opportunities within a compassionate climate.

Krueger & Casey (2009) advise moderators to handle displays of distress empathetically by offering a break and emotional support through active listening instead of ignoring reactions. This upholds ethical principles.

Advantages and disadvantages of focus groups

Focus groups efficiently provide interactive qualitative data that can yield useful insights into emerging themes. However, findings may be skewed by group behaviors and still require larger sample validation through added research methods. Careful planning is vital.

- Efficient way to gather a range of perspectives in participants’ own words in a short time

- Group dynamic encourages more complex responses as members build on others’ comments

- Can observe meaningful group interactions, consensus, or disagreements

- Flexibility for moderators to probe unanticipated insights during discussion

- Often feels more comfortable sharing as part of a group rather than one-on-one

- Helps participants recall and reflect by listening to others tell their stories

Disadvantages

- Small sample size makes findings difficult to generalize

- Groupthink: influential members may discourage dissenting views from being shared

- Social desirability bias: reluctance from participants to oppose perceived majority opinions

- Requires highly skilled moderators to foster inclusive participation and contain domineering members

- Confidentiality harder to ensure than with individual interviews

- Transcriptions may have overlapping talk that is difficult to capture accurately

- Group dynamics adds layers of complexity for analysis beyond just the content of responses

Goss, J. D., & Leinbach, T. R. (1996). Focus groups as alternative research practice: experience with transmigrants in Indonesia. Area , 115-123.

Kitzinger, J. (1994). The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants . Sociology of health & illness , 16 (1), 103-121.

Kitzinger J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311 , 299-302.

Morgan D.L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research . London: Sage.

Mulvale, G., Green, J., Miatello, A., Cassidy, A. E., & Martens, T. (2021). Finding harmony within dissonance: engaging patients, family/caregivers and service providers in research to fundamentally restructure relationships through integrative dynamics . Health Expectations , 24 , 147-160.

Powell, R. A., Single, H. M., & Lloyd, K. R. (1996). Focus groups in mental health research: enhancing the validity of user and provider questionnaires . International Journal of Social Psychiatry , 42 (3), 193-206.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Redmond, R. A., & Curtis, E. A. (2009). Focus groups: principles and process. Nurse researcher , 16 (3).

Smith, J. A., Scammon, D. L., & Beck, S. L. (1995). Using patient focus groups for new patient services. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement , 21 (1), 22-31.

Smithson, J. (2008). Focus groups. The Sage handbook of social research methods , 357-370.

White, G. E., & Thomson, A. N. (1995). Anonymized focus groups as a research tool for health professionals. Qualitative Health Research , 5 (2), 256-261.

Download PDF slides of the presentation ‘ Conducting Focus Groups – A Brief Overview ‘

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Methodological Aspects of Focus Groups in Health Research

Results of Qualitative Interviews With Focus Group Moderators

Anja P Tausch

Natalja menold.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Anja P. Tausch, GESIS–Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, P.O. Box 12 21 55, 68072 Mannheim, Germany. Email: [email protected]

Received 2015 Sep 17; Revised 2015 Dec 15; Accepted 2015 Dec 28; Collection date 2016 Jan-Dec.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 License ( http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access page( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Although focus groups are commonly used in health research to explore the perspectives of patients or health care professionals, few studies consider methodological aspects in this specific context. For this reason, we interviewed nine researchers who had conducted focus groups in the context of a project devoted to the development of an electronic personal health record. We performed qualitative content analysis on the interview data relating to recruitment, communication between the focus group participants, and appraisal of the focus group method. The interview data revealed aspects of the focus group method that are particularly relevant for health research and that should be considered in that context. They include, for example, the preferability of face-to-face recruitment, the necessity to allow participants in patient groups sufficient time to introduce themselves, and the use of methods such as participant-generated cards and prioritization.

Keywords: cancer, content analysis, focus groups, health care administration, electronic personal health record, research, qualitative, technology

Focus groups have been widely used in health research in recent years to explore the perspectives of patients and other groups in the health care system (e.g., Carr et al., 2003 ; Côté-Arsenault & Morrison-Beedy, 2005 ; Kitzinger, 2006 ). They are often included in mixed-methods studies to gain more information on how to construct questionnaires or interpret results ( Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007 ; Kroll, Neri, & Miller, 2005 ).

The fact that the group process helps people to identify and clarify their views is considered to be an important advantage of focus groups compared with individual interviews ( Kitzinger, 1995 ). The group functions as a promoter of synergy and spontaneity by encouraging the participants to comment, explain, disagree, and share their views. Thus, experiences are shared and opinions voiced that might not surface during individual interviews ( Carey, 1994 ; Stewart, Shamdasani, & Rook, 2007 ). Although focus groups allow participants to respond in their own words and to choose discussion topics themselves, they are not completely unstructured. Questions relating to the research topic are designed by the researchers and are used to guide the discussion ( Stewart et al., 2007 ). The degree of structure of the focus group depends on the openness of the research question(s). Hence, although it takes more time and effort to organize focus groups, and they cause greater logistical problems than individual interviews do, they might generate more ideas about, and yield deeper insights into, the problem under investigation ( Coenen, Stamm, Stucki, & Cieza, 2012 ; Kingry, Tiedje, & Friedman, 1990 ; Morgan, 2009 ).

Historically, focus groups were used mainly for market research before the method was adopted for application in qualitative research in the social sciences ( Morgan, 1996 ). The use of focus groups in health care research is even more recent. For this reason, methodological recommendations on using focus groups in the health care context are quite rare, and researchers rely mainly on general advice from the social sciences (e.g., Krueger, 1988 ; Morgan, 1993 ; Morgan & Krueger, 1998 ; Stewart et al., 2007 ). Even though focus groups have been used in a great variety of health research fields, such as patients’ treatments and perceptions in the context of specific illnesses (rheumatoid arthritis: for example, Feldthusen, Björk, Forsblad-d’Elia, & Mannerkorpi, 2013 ; cancer: for example, Gerber, Hamann, Rasco, Woodruff, & Lee, 2012 ; diabetes: for example, Nafees, Lloyd, Kennedy-Martin, & Hynd, 2006 ; heart failure: for example, Rasmusson et al., 2014 ), community health research (e.g., Daley et al., 2010 ; Rhodes, Hergenrather, Wilkin, Alegría-Ortega, & Montaño, 2006 ), or invention of new diagnostic or therapeutic methods (e.g., Vincent, Clark, Marquez Zimmer, & Sanchez, 2006 ), the method and its particular use in health research is rarely reflected. Methodological articles about the focus group method in health care journals mainly summarize general advice from the social sciences (e.g., Kingry et al., 1990 ; Kitzinger, 1995 , 2006 ), while field-specific aspects of the target groups (patients, doctors, other medical staff) and the research questions (not only sociological but often also medical or technical) are seldom addressed. Reports on participant recruitment and methods of conducting the focus groups are primarily episodic in nature (e.g., Coenen et al., 2012 ; Côté-Arsenault & Morrison-Beedy, 2005 ) and often focus on very specific aspects of the method (communication: for example, Lehoux, Poland, & Daudelin, 2006 ; activating methods: for example, Colucci, 2007 ) or aim at a comparison between face-to-face focus groups and other methods (individual interviews: for example, Coenen et al., 2012 ; telephone groups: for example, Frazier et al., 2010 ; Internet groups: for example, Nicholas et al., 2010 ). Thus, systematic reviews of factors influencing the results of focus groups as well as advantages, disadvantages, and pitfalls are missing. One consequence is that researchers might find it difficult to recruit enough participants or might be surprised by the communication styles of the target groups. Furthermore, in the tradition of classical clinical research, the group discussions might result in a question-and-answer situation or “resemble individual interviews done in group settings” ( Colucci, 2007 , p. 1,424), thereby missing out on the opportunity to use the group setting to activate all participants and to encourage a deeper elaboration of their ideas. Colucci, for example, proposed the use of exercises (e.g., activity-oriented questions) to focus the attention of the group on the core topic and to facilitate subsequent analyses.

Recommendations from the social sciences on using the focus group method can be subsumed under the following headings: subjects (target groups, composition of groups, recruitment), communication in the groups (discussion guide, moderator, moderating techniques), and analysis of focus groups (e.g., Morgan, 1993 ; Morgan & Krueger, 1998 ; Stewart et al., 2007 ). Specific requirements for health research can be identified in all three thematic fields: Recruitment might be facilitated by using registers of quality circles to recruit physicians or pharmacists, or by recruiting patients in outpatients departments. It might be hampered by heavy burdens on target groups—be they time burdens (e.g., clinical schedules, time-consuming therapy) or health constraints (e.g., physical fitness). With regard to communication in focus groups, finding suitable locations, identifying optimal group sizes, planning a good time line, as well as selecting suitable moderators (e.g., persons who are capable of translating medical terms into everyday language) might pose a challenge. The analysis of focus groups in health care research might also require special procedures because the focus group method is used to answer not only sociological research questions (e.g., related to the reconstruction of the perspectives of target groups) but also more specific research questions, such as user requirements with regard to written information or technical innovations.

The aim of our study was to gather more systematic methodological information for conducting focus groups in the context of health research in general and in the more specific context of the implementation of a technical innovation. To this end, we conducted interviews with focus group moderators about their experiences when planning and moderating focus groups. The groups in question were part of a research program aimed at developing and evaluating an electronic personal health record. We chose this program for several reasons: First, because it consisted of several subprojects devoted to different research topics related to the development of a personal electronic health record, it offered a variety of research content (cf. next section). Second, the focus groups were conducted to answer research questions of varying breadth, which can be regarded as typical of research in health care. Third, the focus groups comprised a variety of target groups—not only patients but also different types of health care professionals (general practitioners, independent specialists with different areas of specialization, hospital doctors, pharmacists, medical assistants, nursing staff).

In this article, we report the findings of these interviews in relation to the following questions: (a) What challenges associated with the characteristics of the target groups of health research (patients, physicians, other health care professionals) might be considered during the recruitment process? How should the specific research question relating to a technical innovation be taken into account during the recruitment process? (b) Should specific aspects of the communication styles of target groups be taken into account when planning and moderating focus groups in health care? Can additional challenges be identified in relation to the technical research question? and (c) How was the method appraised by the interviewees in their own research context?

Research Program and Description of Focus Groups

The “Information Technology for Patient-Centered Health Care” (INFOPAT) research program ( www.infopat.eu ) addresses the fact that, because patients with chronic conditions (e.g., colorectal cancer, type 2 diabetes) have complex health care needs, many personal health data are collected in different health care settings. The aim of the program is to develop and evaluate an electronic personal health record aimed at improving regional health care for chronically ill people and strengthening patients’ participation in their health care process. Subprojects are devoted, for example, to developing the personal electronic health record (Project Cluster 1), a medication platform (Project Cluster 2), and a case management system for chronically ill patients (Project Cluster 3). In the first, qualitative, phase, the researchers explored patients’ and health care professionals’ experiences with cross-sectoral health care and patient self-management, and their expectations regarding the advantages and disadvantages of a personal electronic health record. The information gathered in this phase of the program served as a basis for constructing a personal electronic health record prototype. This prototype was implemented as an intervention in a second, quantitative, phase dedicated to investigating the impact of such a record on a range of health care variables (e.g., self-management, health status, patient–doctor relationship, compliance). The University Hospital Heidelberg Ethics Committee approved the studies of the INFOPAT research program. All participants gave their written informed consent, and the participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were ensured throughout the studies according to the ethical standards of German Sociological Association. 1

Twenty-one focus groups were conducted during the qualitative phase of the program. Three groups consisted of colorectal cancer patients, four comprised type 2 diabetes patients, four were made up of physicians, three comprised physicians and pharmacists, four consisted of physicians and other health care professionals, and three consisted of other health care professionals (for more detailed information, see Tausch & Menold, 2015 ). Participants were recruited from urban and rural districts of the Rhine-Neckar region in Germany. Patients were approached in clinics, by their local general practitioners, or in self-help groups. Health care professionals were recruited in clinics, cooperating medical practices, and professional networks.

The focus groups took place at several locations at the National Center of Tumor Diseases (NCT) in Heidelberg, Germany, and the University of Heidelberg. The groups consisted of between four and seven participants and lasted between 1.5 and 2 hours. All focus groups were conducted by two researchers—a moderator and a co-moderator; a third researcher took notes. Semistructured discussion guides were used, and the groups were video- and audio recorded (cf., for example, Baudendistel et al., 2015 ; Kamradt et al., 2015 ). The researchers performed content analysis on the transcripts; the schema of categories was oriented toward the research questions. The focus groups addressed research questions of varying breadth, including, for example, individual health care experiences (comparatively broad), the expected impact of the record on the patient–doctor relationship (medium breadth), and technical requirements for such a personal health record (comparatively narrow). The variety of the research questions was important for our study because it proved to be of relevance for the interviewees’ appraisal of the usefulness of the focus group method.

Interviews With the Focus Group Moderators

We conducted qualitative interviews with nine of the 10 focus group moderators in the INFOPAT program (one moderator moved to a different department shortly after the completion of data collection and was not available for interview). The interviewees were aged between 30 and 54 years ( M age = 36 years; SD = 8.3 years). Their professions were health scientist, pharmacist, general practitioner, or medical ethicist. Their professional experience ranged from one to 23 years ( M = 7.1 years, SD = 7.7 years), and they had little or no previous experience of organizing and conducting focus groups. The moderators were interviewed in groups of one to three persons according to their project assignment (cf. Table 1 ).

Overview of Interviews and Interviewees.

A description of the cluster research questions is given in the text.

The interviews lasted approximately 1 hour, and the interview questions were guided by the chronological order in which a focus group is organized and conducted (recruitment, preparation, moderation, methods) and by the utilization and usefulness of the results. We tape recorded the interviews, transcribed them verbatim, and performed qualitative content analysis on the transcripts ( Elo & Kyngäs, 2008 ; Mayring, 2015 ) with the help of the program MAXQDA 10.0.

The final system of categories 2 ( Tausch & Menold, 2015 ) consisted of two types of codes: All relevant text passages were coded with respect to the content of the statement. In addition, a second type of code was required if the statement related to a specific group of participants (e.g., patients, hospital doctors, men, women).

On the basis of the research questions, the contents of interview statements were classified into the three superordinate thematic categories: recruitment, communication in the focus groups, and appraisal of the focus group method. Consequently, the reporting of the results is structured according to three main topics.

Recruitment

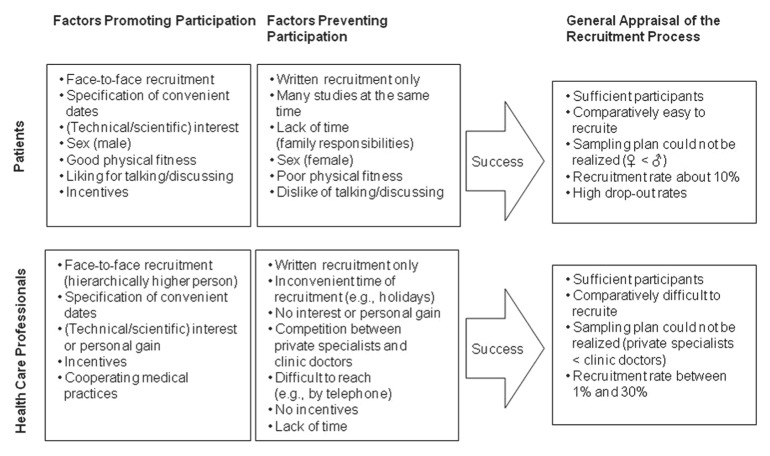

Statements relating to the recruitment of the participants were sorted into the main categories “factors promoting participation”, “factors preventing participation”, and “general appraisal of the recruitment process”. Figure 1 shows the subcategories that were identified under these main categories. Because many of the statements referred only to patients or only to health care professionals (physicians, other health care professionals), the subcodes shown in Figure 1 are sorted by these two types of participants.

Factors relating to the recruitment process.

Factors relevant for all target groups

As the following interviewee statement shows, addressing potential participants face-to-face (rather than in writing) proved crucial for the success of recruitment in all target groups:

Well, a really good tip when recruiting patients is . . . to address the people yourself. Not to get someone else to do it who . . . has nothing to do with [the project], because ultimately you really do have to explain a lot of things, also directly to the patient. And then it’s always good if the person [who does the recruiting] is actually involved in the project. 3

In the case of the clinicians, being addressed by a superior was even more effective for their willingness to participate: “And then top down. If the nursing director asks me, then it’s not so easy to say no.”

Furthermore, a positive response was more often achieved if the groups were scheduled at convenient times for the addressees, and they only had to choose between several alternatives. Patients welcomed times contiguous with their therapies: “And many [of the patients] said: ‘Yes, maybe we can do it after my chemotherapy, on that day when I’m in the clinic anyway?’” Whereas medical assistants were given the opportunity to take part in the groups during working hours, general practitioners preferred evening appointments on less busy weekdays (e.g., Wednesdays and Fridays):

Well, what I found quite good was to suggest a day and a time. And we concentrated on the fact that practices are often closed on Wednesday afternoons. So that’s a relatively convenient day. And then evenings for the pharmacists from seven-thirty onwards.

Interest in the topic of the discussion, or at least in research in general, was an important variable for participation. Together with lack of time, it turned out to be the main reason why sampling plans could not be realized. Among patients, men were much more interested in discussing a technical innovation such as an electronic personal health record, while women—besides their lesser interest—often declined because of family responsibilities: “Well, I’d say a higher proportion of women said: ‘I have a lot to do at home, housework and with the children, therefore I can’t do it.’”

Family physicians, physicians from cooperating medical practices, and hospital doctors showed more interest in discussing an electronic personal health record than did medical specialists in private practice, who often saw no personal gain in such an innovation. For example, one interviewee stated,

Family physicians generally have a greater willingness [to engage with] this [health] record topic. They see . . . also a personal benefit for themselves. . . . or they simply think it might be of relevance to them or they are interested in the topic for other reasons. Some of them even approached us themselves and said, “Oh, that interests me and I’d like to take part.”

In addition, because of heavy workload, private practitioners were difficult to reach (e.g., by telephone). This also lowered the participation of this target group on the focus groups.

Factors relevant only for patients

Two other variables that influenced patients’ willingness to participate were mentioned in the interviews. First, because this target group consisted of cancer patients and diabetes patients with multimorbidity, poor physical fitness also prevented several addressees from participating in the groups. The inability to climb stairs, or the general inability to leave the house, made it impossible for them to reach the location where the groups took place: “[They] immediately replied: ‘Well, no, . . . that’s really too much for me,’ and unfortunately they could not, therefore, be included in the groups.” Furthermore, unstable physical fitness often led to high drop-out rates. The moderators of the focus groups therefore proposed that up to twice as many participants as required should be recruited: “And depending on the severity of the illness, you have to expect a drop-out rate of up to fifty percent. So, if you want to have four people, you should invite eight.”

Second, moderators reported that patients’ liking for, or dislike of, talking and discussing influenced their tendency to join the groups. Participating patients were generally described as talkative. For example: “And with patients, all in all, I had the feeling that those who agreed [to participate] were all people who liked talking, because those who did not like talking refused out of hand.” Patients who refused to participate often argued that they felt uncomfortable speaking in front of a group: “And the men, when they declined they often said: ‘No, group discussion is not for me! I don’t like talking in front of a group.’”

The researchers eventually succeeded in recruiting sufficient participants. However, they were not able to realize the sampling plans according to a certain proportion of male and female patients or types of physicians. “Well, we finally managed to fill up our groups, but only as many [participants] as necessary.” Comparing the different target groups, recruiting patients was described as easier than recruiting physicians: “And that was much easier insofar as you just had to go to the clinic and each day there were five or six patients whom you could address.” However, only 10% of the patients who were addressed agreed to participate. In the health care professional group, the recruitment rates ranged between 0% and 30%, depending on the subgroup. This can be demonstrated by the following interviewee utterance:

And in the private practitioner sector it was rather . . . . Well, we tried to recruit specialists in private practice, in other words internists, gastroenterologists, and oncologists. The success [rate proved to be] extremely poor. . . . Well, on the whole, the willingness to take part, the interest, is not there. Or, well they don’t give the reasons, but they say they don’t want to take part. So that was difficult and, yes, it didn’t go too well.

Communication in the Focus Groups

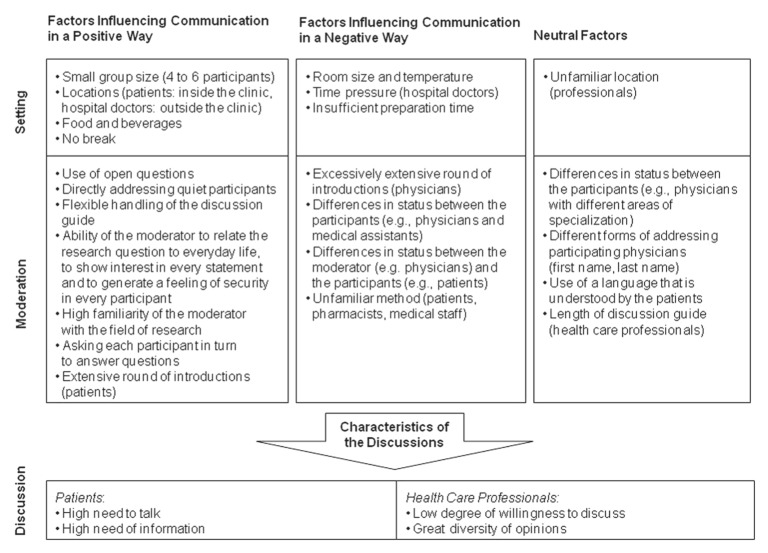

With regard to the communication in the focus groups, the moderators identified factors that influenced communication in a positive or negative way. In addition, we discussed a number of factors with them that are often described in the social science literature as problematic when conducting focus groups. However, the interviewees considered that some of these factors had not influenced communication in the focus groups conducted within the framework of the INFOPAT program. In our system of categories, we also coded whether the factors in question were related to (a) the setting or (b) the moderation of the focus groups (cf. Figure 2 ).

Influences on and characteristics of the focus group discussion.

Factors relating to the setting

As Figure 2 shows, communication was reported to be positively influenced by small group size, location, provision of food and beverages, and conducting the focus group without a break. In contrast to general recommendations on focus groups in the context of sociological research, the moderators in the INFOPAT program considered a smaller group size of between four and six participants to be ideal. With regard to location, the interviewees reported that, depending on the target group, different places were perceived as positive. Patients preferred locations inside the clinic because they were easy to reach and caused no additional effort. Furthermore, because these locations were familiar to them, they facilitated an atmosphere of security and ease, which was seen as an important prerequisite for an open and honest discussion. This is clear from the following quotation:

Well, the patient focus groups were all located at the clinic. We chose this location on purpose to make it easier for them, because they come to the clinic anyway for their therapy. And they know the place and they feel comfortable and in good hands.

By contrast, the clinician groups benefited from being located outside the clinic. In contrast to other common addressees of focus groups, these professionals were not only accustomed to participating in groups outside their familiar surroundings but also this location helped them to distance themselves from their professional duties and to engage more deeply in the discussion, as shown by the following quotation:

Yes, one was located at the O-Center. We chose this location on purpose so that the clinicians had to leave the hospital. It’s not too far, only a few yards away. But we wanted them to leave the clinic, and not to run back to the ward when they were called. And, well, I liked this location.

Food and beverages were welcome in all the groups and also helped to create a positive and trusting atmosphere. And finally, the interviewees found that it was better to omit the break, thereby avoiding the interruption of the ongoing discussion. This is reasonable considering the comparatively short duration of the focus group session (between 1.5 and 2 hours). Statements relating to a break might have been different in the case of longer focus group durations.

The interviewees reported that the size and temperature of the room and time pressure on the participants or the moderator had a negative impact on communication. Some of the focus groups in the project took place in midsummer and had to be held in rooms without blinds or air conditioning. The moderators of these groups had to work hard to maintain the participants’ (and their own) attention and concentration. Time pressure on the participants (e.g., the clinicians) led to an unwillingness to engage in active discussion and created a question-and-answer situation, as shown by the following statement:

And in one group of physicians . . . we never reached the point where they joined in fully. During the whole discussion they never completely arrived. And they had already cut the time short in advance. They were under so much time pressure that they were not able to discuss in an open manner.

Moderators reported that they, too, had experienced time pressure—namely, in situations where they did not have enough time to prepare the room and the recording devices. This had caused them to be nervous and stressed at the beginning of the discussion, which had negatively affected the mood of the participants, thereby rendering an honest and open discussion particularly difficult.

Factors relating to the moderation

Many of the positive factors reported by the interviewees have already been described for focus groups in general—for example, using open questions, directly addressing quiet participants, and handling the discussion guide in a flexible way. Furthermore, by showing interest in every statement, and by generating a feeling of security in every participant, moderators fostered a fruitful discussion:

I believe that another important point is that you are calm yourself. That you give the people the feeling “you can feel safe with me, you don’t have to worry that I will make fun of you . . . or that I won’t take you seriously.”

Interviewees also considered that building a bridge between the technical innovation under discussion (a web-based electronic personal health record) and everyday life (e.g., online banking) was an important factor in getting all participants to contribute to the discussion. As one interviewee noted,

We tried to anchor it in their everyday lives. And . . . the example that always worked was when we said: “Think of it as if it were a kind of online banking.” Everyone understands what online banking is. It’s about important data on the internet; they’re safe there somehow. I have my password. And people understood that. Well, it’s important to anchor it in their reality . . . because otherwise the topic is simply far too abstract.

In this context, the fact that the groups were moderated by the researchers themselves proved very helpful because they were able to answer all questions relating to the research topic. As the following quote shows, this was an important prerequisite for opinion formation on the part of participants:

Well, I think that a really important quality criterion . . . is that you have completely penetrated [the topic]. If you only know the process from the outside . . . and you then conduct the focus group about it. . . . Somewhere, at some stage, [one discussion] narrowly missed the point. . . . You simply have to be totally immersed in the topic, well, I believe that [someone who is totally immersed in the topic] is the ideal person for the job. And in our case the thinking was, okay, so I’m a doctor, but on balance it’s more important that both [moderators] are absolutely well informed because it’s a complex topic.

The more specific the research question was, the more useful the moderating strategy of inviting one participant after the other to express their opinion appeared to be. By using this strategy, the moderators ensured that every participant contributed to the discussion.

A point that was strongly emphasized by the interviewees was the duration of the round of introductions at the beginning of the focus group session. In the patient groups, introductions took much more time than the researchers had expected. Patients had a high need to express themselves and to tell the others about their illness and their experiences with the health system. Although this left less time to work through the topics in the discussion guide, the researchers came to realize that there were several good reasons not to limit these contributions: First, the introductions round proved important for helping the participants to “arrive” at the focus group, for creating a basis of trust, and for building up a sense of community among the participants. Second, the interviewees reported that, because many topics in the discussion guide (e.g., participants’ experiences with coordinating visits to different medical specialists) had already been brought up in the round of introductions, they did not have to be discussed further at a later stage:

And that is the crux of this general exchange of experiences at the beginning. Sure, it costs you a lot of time, but I almost think that if you don’t give them that time, you won’t get what you want from them, in the sense that you say: “I want to hear your frank opinion or attitude.” You don’t want them to simply answer you because they think that’s what you want to hear. You have to create an atmosphere in which they really forget where they are. I’m relatively convinced that you wouldn’t achieve that without such [a round of introductions].

The moderators’ experience in the physician groups was different. These groups benefited from having a rather short round of introductions. Giving participants too much time to introduce themselves meant that they presented their expertise rather than reporting their experiences. In contrast to the patient groups, this did not substantially contribute to the discussion of the research topics.

Depending on the context, status differences between the moderators and the participants, or among the participants, were appraised differently by interviewees. In one group comprising physicians and medical assistants, the moderators observed that status differences had a negative influence on communication. Very young female medical assistants, in particular, did not feel free to express their opinions in the presence of their superiors. By contrast, presumed differences in status between family doctors, hospital doctors, and medical specialists in private practice did not have any negative impact on communication. Nor did different forms of address (some participants in these groups were addressed by their first name and some by their last name, depending on the relationship between the moderator and the participants). Status differences between moderators (if medical doctors) and participants (patients) had an impact on communication when patients regarded doctors as an important source of information (e.g., about the meaning of their blood values) or as representatives of the health care system to whom complaints about the system should be addressed. The latter case was the subject of the following interview statement by a moderator who is a physician by profession:

And a lot [was said about] the kind of experiences they had had here at the NCT. And of course, when the patients have been treated here for many years—or even for not so many [years], but they have had many experiences—they sometimes reported at length. And I had the feeling that this had a bit of a feedback function, quite generally, for the NCT. Also the somehow frustrating experiences they had had, or a lot of things that had not gone that well in conversational exchanges [with the staff]. There was a relatively large amount of feedback that didn’t have a lot to do with the topic because I was, of course, involved as a senior physician and I am not an external researcher, but rather someone who is also seen as being jointly responsible, or at least as someone who can channel criticism.

Finally, because most of the moderators were not medical professionals, they did not experience the translation of medical or technical terms into everyday language as problematic. Rather, they automatically used terms that were also familiar to the participants.

Characteristics of the discussion

The factors described above resulted in focus group discussions that might be interpreted as characteristic of health research. The patient focus groups were characterized by a strong need to talk and a high need for information. In the health care professional focus groups, researchers experienced a greater variety of communication styles. Because of a lack of time, or because they falsely expected a question-and-answer situation, some groups demonstrated a low degree of willingness to engage in discussion:

Although, I believe that was partly due . . . well there was one [woman] who was very demanding; she wanted to know straight away: “Yes, what’s the issue here? What do I have to say to you?” Well, the three who came from the one practice, I think they really had the feeling that we would ask them questions and they would bravely answer them and then they could go home again. So, for them this principle that they were supposed to engage in a discussion, for them that was somehow a bit, I don’t know . . . disconcerting. . . . They really thought: “Okay, well we want to know now what this is all about. And they’ll ask us the questions and then we’ll say yes, no, don’t know, maybe. And then we’ll go home again.” Well, at least that was my impression.

Other groups, especially those consisting of different types of health care professionals (e.g., physicians with different areas of specialization, or physicians and pharmacists), were characterized by lively discussion and a great variety of opinions.

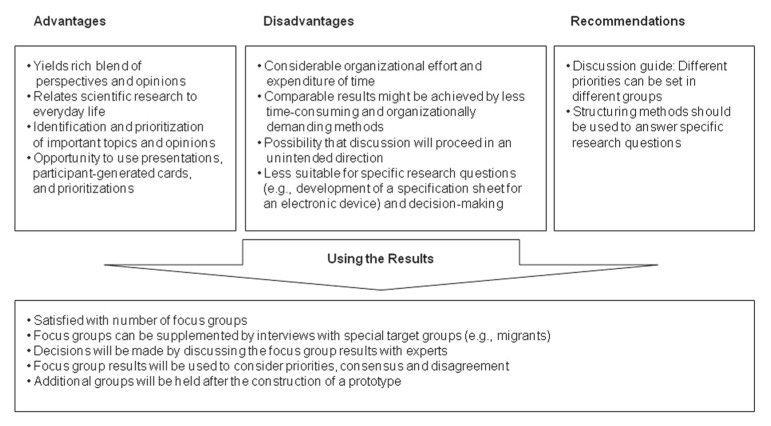

Appraisal of the Focus Group Method

We classified moderators’ statements relating to the appraisal of the focus group method into four main categories: “advantages of the method”, “disadvantages of the method”, “recommendations for other researchers in related research areas”, and “statements on how they used the results” (cf. Figure 3 ).

Appraisal of the focus group method.

The researchers reported that the focus group method yielded a rich blend of perspectives and opinions, brought forth, in particular, by the interaction between the participants:

But for this question and the topic, and for our lack of knowledge, that was . . . a lot of new information . . . and very many good ideas and critical remarks that you naturally read in the literature from time to time. But, let’s say, because of the complexity of the participants’ reactions and the weight they attached to things, it’s different than reading in a literature review that [this or that] could be taken into account.

The results of the focus groups further enriched the researchers’ work by relating it to everyday life: “Well, what was nice was that the topic was related to the participants’ lives. That people said: ‘Now the topic is important for me.’” Furthermore, the method yielded information about which aspects were most important and how the variety of opinions should be prioritized. This was achieved, in particular, by using participant-generated cards:

And with regard to prioritization, we incorporated it using participant-generated cards. We said: “Look: If you could develop this record now, what would be the three most important things that must absolutely be taken into consideration, from your point of view, no matter what they relate to.” And they wrote them down on the cards. And after that they were asked to carry out their own prioritization—that is, what was most important to them personally. One person wrote “data protection” first, while another [wrote] “sharing with my wife.” . . . That was good. . . . That helped a lot because it was simply clear once again what things were important to them.

In cases where concrete questions had to be answered or decisions had to be made, the interviewees also welcomed the opportunity to use structuring methods such as presentations, flip-charts, and participant-generated cards to obtain the relevant information:

. . . Well, the aim was that at the end we [would] have a set of requirements for the engineering [people]. And the engineering [people] don’t so much want to know about experiences and desires and barriers, but rather they want to know should the button be green or red and can you click on it. And that’s why I thought at the beginning it will be difficult with a focus group and an open discussion. Now, if you say that one can also interpret a focus group the way we did, partly with very specific questions and these participant-generated cards, then I think it is indeed possible to answer such questions as well.

Disadvantages

The main disadvantages of the focus group method were seen in the considerable organizational effort and expenditure of time involved. A question raised by some of the interviewees was whether comparable results could have been achieved using less time-consuming and organizationally demanding methods.

It’s true to say that you lose time. Well, you could implement [the innovation] straight away and see whether it’s better. Maybe, in this case you’re wrong and you just think it’s better or in any case not worse than before. You basically lose a year on this whole focus groups thing.

Moreover, in some cases, the discussion went in an unwanted direction and the moderators never fully succeeded in bringing the group back to the intended topics.

Furthermore, like many other medical research projects, INFOPAT included quite specific research questions. In this connection, the moderators emphasized that open focus group discussions would not have succeeded in answering those questions. Only by using methods such as participant-generated cards and prioritization was it possible to answer at least some of them. Nonetheless, some interviewees did not consider the focus group method to be really suitable for this type of research questions:

Of course we also have our engineers as counterparts who . . . need very specific requirements at some point. The question is whether such a focus group . . . . [It] can’t answer that in detail in this first stage. It’s simply not practicable.

Recommendations

As described under the “Communication in the Focus Groups” section above, the round of introductions in the patient groups lasted much longer than planned, thereby shortening the time available for other topics in the discussion guide. As a result, the moderators decided to choose a different thematic focus in each group so that every topic was discussed more deeply in at least one group.

What we usually did was to consider what hadn’t been addressed that much in the previous focus group. That [topic] was given more room in the next focus group because the guide, well it was quite a lot. You could have easily gone on discussing for another hour or two.

Using the results

On the whole, the researchers were satisfied with the number of groups that were conducted and the results that they yielded. They did not agree that more groups would have led to better, or different, results—with one possible exception, namely, in the case of specific target groups (e.g., migrants). Only one group had been composed of patients with a migrant background, and, as one interviewee stated, “I just thought, the patients with a migrant background . . . now that was [only] one group, it by no means covers the whole range.”

In cases where the results of the focus groups were perceived as not being concrete enough to proceed to the next research step (e.g., formulating a specification sheet for the construction of the electronic personal health record), the researchers planned to bring experts together in a roundtable format to make decisions on the basis of the priorities, agreements, and disagreements that had emerged from the focus groups. Following the construction of a prototype, they intended to conduct further focus groups to validate or adapt the usability of the electronic personal health record system.

Our analysis of interviews with focus group moderators yielded considerable insights into methodological aspects of conducting focus groups in health research. Our first research question related to characteristics of the target groups that should be considered during the recruitment process. We identified face-to-face contact as an important factor promoting focus group participation. The interviewees considered this type of contact to be better suited to answering target persons’ questions and explaining the method and aims of the focus groups. Moreover, they felt that addressees might find it more difficult to decline a face-to-face invitation than a written one. With regard to health care professionals, an invitation issued by a hierarchically higher person was most effective, even though ethical aspects should be considered in this case, and voluntary participation should nevertheless be ensured. Otherwise, the order to participate might prevent an atmosphere of open communication and might lead to a lower quantity or to more negative statements.

Furthermore, whereas physicians are usually accustomed to discussing topics with others, an important characteristic that influenced willingness to participate on the part of members of other target groups (other health care professionals, patients) was a liking for, or a dislike of, talking. Researchers might take account of this fact by explaining the method in more detail, by developing arguments to overcome fears, or, as suggested, for example, by Colucci (2007) , by convincing the addressees with other activities implemented in the focus groups. Other relevant personal characteristics—be they related to the research topic (e.g., technical interest in the case of an electronic innovation) or to the specific target group (e.g., physical fitness on the part of patients or lack of time on the part of health care professionals)—should be anticipated when planning recruitment. These characteristics might be taken into account by preparing arguments, providing incentives, giving thought to favorable dates and times, and choosing easily accessible locations. An interesting finding was that, depending on the target group, different locations were considered to have a positive influence on the discussion. Whereas locations inside the clinic were preferred in the case of the patient focus groups because of familiarity and easy accessibility, hospital doctors were more engaged in the discussion when the focus group site was located at least some yards away from their workplace.

Finally, the experience of our researchers that up to 50% of the patients had to cancel at short notice because of health problems does not appear to be uncommon in this research context. That overrecruitment is an effective strategy—particularly in health care research—has been reported by other authors (e.g., Coenen et al., 2012 ).

With our second research question, we focused on aspects of communication in the focus groups. The interviews revealed several factors specific to research topics and addressees of health care studies that influenced the discussions. Consequently, in addition to considering general recommendations regarding the organization and moderation of focus groups (e.g., choosing adequate rooms with a pleasant atmosphere, serving food and beverages, using open questions, showing interest in all contributions, and directly addressing quiet participants), these health care specific aspects should be taken into account. Relevant factors that should be addressed when moderating focus groups in this context are (a) the strong need to talk and the high need for information in the patient groups, (b) status differences between the participants or between the moderators and the participants, (c) the size of the focus group, and (d) the specificity of the topic of discussion. The interview data revealed that these factors influenced the discussions and thus the results achieved with the groups. In addition, the following four possibilities of addressing these factors were identified:

First, the moderators had to devote more time to the round of introductions in the patient groups, which served as a warm-up, created an atmosphere of fellowship and openness, and accommodated this target group’s strong need to talk. Second, with respect to status differences between the moderator and the participants, no definite recommendations can be derived from the interviews. The interviewees found that it was less favorable when the moderator was perceived not only in that role but also in other roles (e.g., physician), because this might hamper a goal-oriented discussion. However, they considered deep insight into the research topic on the part of the moderators to be beneficial, at least for certain research topics. Thus, one should carefully weigh up whether it is more advantageous or more disadvantageous when the group moderator is a physician. Interviewees considered status differences between participants to be disadvantageous only in one case, where—because of organizational constraints—medical assistants and their superiors joined the same focus group, which gave rise to some reticence on the part of the young assistants. Similar problems have been reported by other authors, for example, Côté-Arsenault and Morrison-Beedy (2005 ; see also Hollander, 2004 ). However, interviewees did not experience as problematic status differences between physicians with different areas of specialization.

Third, with respect to group size, interviewees found comparatively small focus groups appropriate to give all participants enough time to tell their stories. In contrast to social science research, where groups of between eight and 20 participants are recommended, our interviewees considered groups of between four and six persons to be optimal. This is in line with Côté-Arsenault and Morrison-Beedy (2005) , who recommended small groups for health research, especially when sensitive topics are discussed. Our interview data revealed that this recommendation might also be useful for other health research topics.