- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

The four major ethnic divisions among Black South Africans are the Nguni, Sotho, Shangaan-Tsonga and Venda. The Nguni represent nearly two thirds of South Africa's Black population and can be divided into four distinct groups; the Northern and Central Nguni (the Zulu-speaking peoples), the Southern Nguni (the Xhosa-speaking peoples), the Swazi people from Swaziland and adjacent areas and the Ndebele people of the Northern Province and Mpumalanga. Archaeological evidence shows that the Bantu-speaking groups that were the ancestors of the Nguni migrated down from East Africa as early as the eleventh century.

Language, culture and beliefs:

The Xhosa are the second largest cultural group in South Africa, after the Zulu-speaking nation. The Xhosa language (Isixhosa), of which there are variations, is part of the Nguni language group. Xhosa is one of the 11 official languages recognized by the South African Constitution, and in 2006 it was determined that just over 7 million South Africans speak Xhosa as a home language. It is a tonal language, governed by the noun - which dominates the sentence.

Missionaries introduced the Xhosa to Western choral singing. Among the most successful of the Xhosa hymns is the South African national anthem, Nkosi Sikele' iAfrika (God Bless Africa). It was written by a school teacher named Enoch Sontonga in 1897. Xhosa written literature was established in the nineteenth century with the publication of the first Xhosa newspapers, novels, and plays. Early writers included Tiyo Soga, I. Bud-Mbelle, and John Tengo Jabavu .

Stories and legends provide accounts of Xhosa ancestral heroes. According to one oral tradition, the first person on Earth was a great leader called Xhosa. Another tradition stresses the essential unity of the Xhosa-speaking people by proclaiming that all the Xhosa subgroups are descendants of one ancestor, Tshawe. Historians have suggested that Xhosa and Tshawe were probably the first Xhosa kings or paramount (supreme) chiefs.

The Supreme Being among the Xhosa is called uThixo or uQamata . As in the religions of many other Bantu peoples, God is only rarely involved in everyday life. God may be approached through ancestral intermediaries who are honoured through ritual sacrifices. Ancestors commonly make their wishes known to the living in dreams. Xhosa religious practice is distinguished by elaborate and lengthy rituals, initiations, and feasts. Modern rituals typically pertain to matters of illness and psychological well-being.

The Xhosa people have various rites of passage traditions. The first of these occurs after giving birth; a mother is expected to remain secluded in her house for at least ten days. In Xhosa tradition, the afterbirth and umbilical cord were buried or burned to protect the baby from sorcery. At the end of the period of seclusion, a goat was sacrificed. Those who no longer practice the traditional rituals may still invite friends and relatives to a special dinner to mark the end of the mother's seclusion.

Male and female initiation in the form of circumcision is practiced among most Xhosa groups. The Male abakweta (initiates-in-training) live in special huts isolated from villages or towns for several weeks. Like soldiers inducted into the army, they have their heads shaved. They wear a loincloth and a blanket for warmth, and white clay is smeared on their bodies from head to toe. They are expected to observe numerous taboos (prohibitions) and to act deferentially to their adult male leaders. Different stages in the initiation process were marked by the sacrifice of a goat.

The ritual of female circumcision is considerably shorter. The intonjane (girl to be initiated) is secluded for about a week. During this period, there are dances, and ritual sacrifices of animals. The initiate must hide herself from view and observe food restrictions. There is no actual surgical operation.

Although they speak a common language, Xhosa people belong to many loosely organized, but distinct chiefdoms that have their origins in their Nguni ancestors. It is important to question how and why the Nguni speakers were separated into the sub-group known today. The majority of central northern Nguni people became part of the Zulu kingdom, whose language and traditions are very similar to the Xhosa nations - the main difference is that the latter abolished circumcision.

In order to understand the origins of the Xhosa people we must examine the developments of the southern Nguni, who intermarried with Khoikhoi and retained circumcision. For unknown reasons, certain southern Nguni groups began to expand their power some time before 1600. Tshawe founded the Xhosa kingdom by defeating the Cirha and Jwarha groups. His descendants expanded the kingdom by settling in new territory and bringing people living there under the control of the amaTshawe. Generally, the group would take on the name of the chief under whom they had united. There are therefore distinct varieties of the Xhosa language, the most distinct being isiMpondo (isiNdrondroza) . Other dialects include: Thembu, Bomvana, Mpondimise, Rharhabe, Gcaleka, Xesibe, Bhaca, Cele, Hlubi, Ntlangwini, Ngqika, Mfengu (also names of different groups or clans).

Unlike the Zulu and the Ndebele in the north, the position of the king as head of a lineage did not make him an absolute king. The junior chiefs of the various chiefdoms acknowledged and deferred to the paramount chief in matters of ceremony, law, and tribute, but he was not allowed to interfere in their domestic affairs. There was great rivalry among them, and few of these leaders could answer for the actions of even their own councillors. As they could not centralise their power, chiefs were constantly preoccupied with strategies to maintain the loyalties of their followers.

The Cape Nguni of long ago were cattle farmers. They took great care of their cattle because they were a symbol of wealth, status, and respect. Cattle were used to determine the price of a bride, or lobola, and they were the most acceptable offerings to the ancestral spirits. They also kept dogs, goats and later, horses, sheep, pigs and poultry. Their chief crops were millet, maize, kidney beans, pumpkins, and watermelons. By the eighteenth century they were also growing tobacco and hemp.

At this stage isiXhosa was not a written language but there was a rich store of music and oral poetry. Xhosa tradition is rich in creative verbal expression. Intsomi (folktales), proverbs, and isibongo (praise poems) are told in dramatic and creative ways. Folktales relate the adventures of both animal protagonists and human characters. Praise poems traditionally relate the heroic adventures of ancestors or political leaders.

As the Xhosa slowly moved westwards in groups, they destroyed or incorporated the Khoikhoi chiefdoms and San groups, and their language became influenced by Khoi and San words, which contain distinctive 'clicks'.

Europeans who came to stay in South Africa first settled in and around Cape Town. As the years passed, they sought to expand their territory. This expansion was first at the expense of the Khoi and San, but later Xhosa land was taken as well. The Xhosa encountered eastward-moving White pioneers or 'Trek Boers' in the region of the Fish River. The ensuing struggle was not so much a contest between Black and White races as a struggle for water, grazing and living space between two groups of farmers.

Nine Frontier Wars followed between the Xhosa and European settlers, and these wars dominated 19th century South African History. The first frontier war broke out in 1780 and marked the beginning of the Xhosa struggle to preserve their traditional customs and way of life. It was a struggle that was to increase in intensity when the British arrived on the scene.

The Xhosa fought for one hundred years to preserve their independence, heritage and land, and today this area is still referred to by many as Frontier Country.

During the Frontier Wars, hostile chiefs forced the earliest missionaries to abandon their attempts to 'evangelise' them. This situation changed after 1820, when John Brownlee founded a mission on the Tyhume River near Alice, and William Shaw established a chain of Methodist stations throughout the Transkei.

Other denominations followed suit. Education and medical work were to become major contributions of the missions, and today Xhosa cultural traditionalists are likely to belong to independent denominations that combine Christianity with traditional beliefs and practices. In addition to land lost to white annexation, legislation reduced Xhosa political autonomy. Over time, Xhosa people became increasingly impoverished, and had no option but to become migrant labourers. In the late 1990s, Xhosa labourers made up a large percentage of the workers in South Africa's gold mines.

The dawn of apartheid in the 1940s marked more changes for all Black South Africans. In 1953 the South African Government introduced homelands or Bantustans, and two regions 'Transkei and Ciskei' were set aside for Xhosa people. These regions were proclaimed independent countries by the apartheid government. Therefore many Xhosa were denied South African citizenship, and thousands were forcibly relocated to remote areas in Transkei and Ciskei.

The homelands were abolished with the change to democracy in 1994 and South Africa's first democratically elected president was African National Congress (ANC) leader, Nelson Mandela , who is a Xhosa-speaking member of the Thembu people.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

- Privacy Policy

- Safeguarding

- Accessibility

- Unsubscribe

The spirit of Ubuntu: The Xhosa people of South Africa

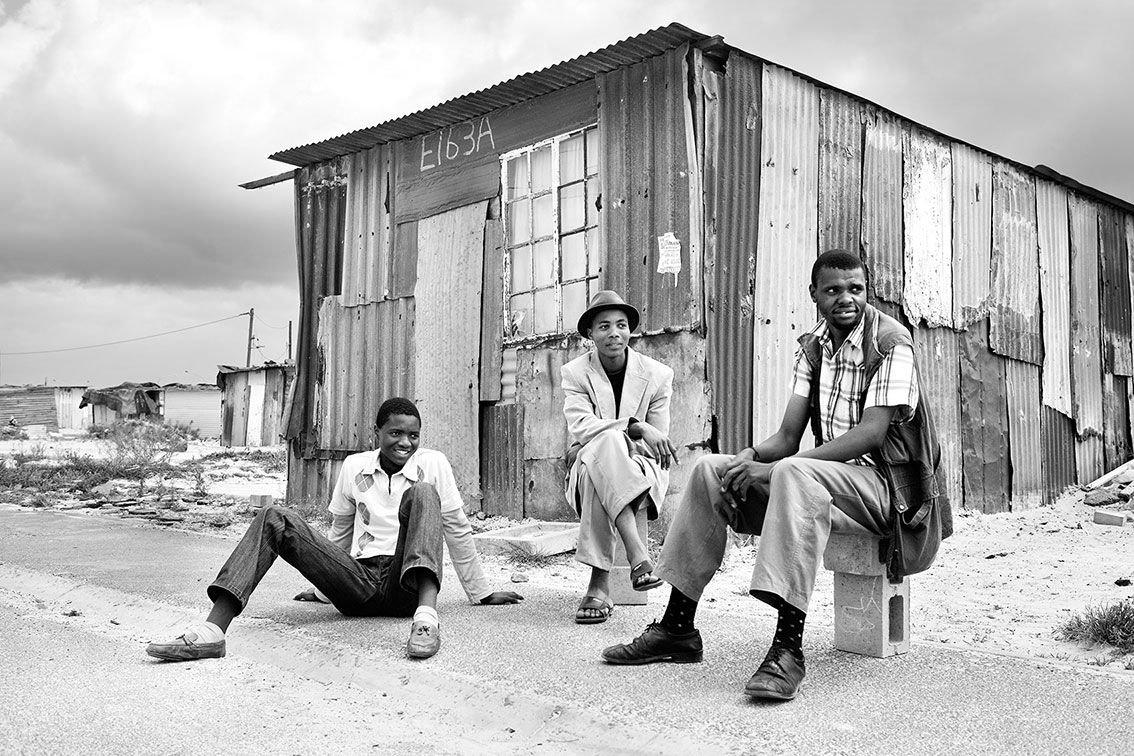

Lavonne Bosman , a South African photographer, shares her journey to the Transkei, a rural area on the East coast of South Africa.

At the age of 34, when many of my friends were buying houses and starting families, I bought a small second-hand caravan and traded my city comforts for a different kind of lifestyle amongst the Xhosa people in Coffee Bay, a small coastal town in one of the poorest areas of our country, the rural homelands of the Transkei. What started as five months quickly turned into more than two years.

The first couple of weeks in Coffee Bay were a bit of a culture shock. This tiny town of rainbow people and picturesque landscapes contrasted with the grim effects of poverty. The area is at once ancient and modern, with numerous diverse cultures, belief systems and values. In this beautiful tropical paradise, largely untouched by Western modernity and its pressures, the colorful Xhosa people live a very simple traditional life.

During my time in the Transkei, I gained experience with Ubuntu, best explained by Archbishop Tutu as,

“The essence of being human. Ubuntu speaks particularly about the fact that you can’t exist as a human being in isolation. It speaks about our interconnectedness … We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected and what you do affects the whole world. When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity.”

Through the photographs I took during my time in the Transkei, I hope to give a glimpse into the lives and character of the Xhosa people and above all, the spirit of Ubuntu.

The Xhosa people living a very simple traditional life

Xhosa boys driving their hand-crafted wire cars

Which image illustrates the spirit of Ubuntu the most? Tell us in a comment below.

Thank you Lavonne for sharing your photos with us! View her portfolio here .

If you believe everyone has the right to a life of opportunity and justice, no matter where they live, and if you believe ordinary people can change the world, then join us.

Sign up to receive emails from ONE and join millions of people around the world taking action to end extreme poverty and preventable disease. We'll only ever ask for your voice, not your money. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Please enable JavaScript to complete this form.

Privacy options

Do you want to stay informed about how you can help fight against extreme poverty?

Disclaimer options

By signing you agree to ONE's privacy policy , including to the transfer of your information to ONE's servers in the United States.

You agree to receive occasional updates about ONE's campaigns. You can unsubscribe at any time.

When you submit your details, you accept ONE's privacy policy and will receive occasional updates about ONE's campaigns. You can unsubscribe at any time.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- B-BBEE Level 1

- OUP WORLDWIDE

- RESOURCE HUB

- HOW TO ORDER

- PRICE LISTS

- LOGIN/REGISTER

- SHOPPING CART

- COMPETITIONS

- Description

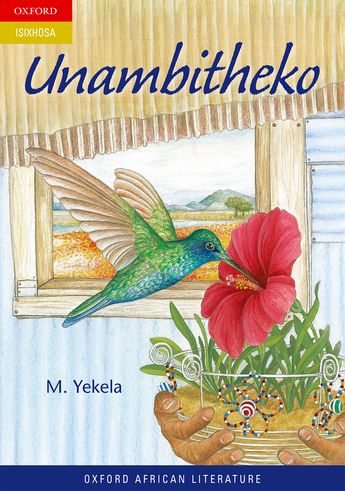

U-Unambitheko yincwadi equlethe izincoko ezichaphazela imiba ngemiba kubomi esibuphilayo kuwo lo mhlaba umagad ahlabayo. Ingakumbi kula maxesha sikuwo, zininzi izinto ezifika ziphithikeze ingqondo yomntu oNtsunda atsho angazazi nokuba ubheka kweliphi na icala. Zingena kweso sithuba ke izincoko kuba zona ziyayixhokonxa ingqondo, zimenze obelele abuke ebuthongweni, zimenze ohleliyo abe ngathi uyazikisa ukucinga. Le ncwadi ilikhwelo kumZi oNtsundu. Vukani! A collection of contemporary essays that explore the pros and cons of common issues (eg. the role of TV, corporal punishment) and further encourage debate and reflection on these topics.

The specification in this catalogue, including without limitation price, format, extent, number of illustrations, and month of publication, was as accurate as possible at the time the catalogue was compiled. Due to contractual restrictions, we reserve the right not to supply certain territories.

The personal perspective essay in Xhosa as reflection of the writing competence of grade 12 learners

Journal title, journal issn, volume title, description, collections.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A cross-linguistics analysis of the writing of prospective first year students in Xhosa and English

Related Papers

Per Linguam

Zannie Bock

Greener Journal of Educational Research

dorcas zuvalinyenga

Christa van der Walt

Felix Banda

Nonformal speech is often considered primary discourse and can be casually picked up in everyday conversational English. Formal English is considered secondary discourse and is usually learned through some form of apprenticeship in particular contexts. One would expect that after 12 years of instruction in English, students should at least be able to distinguish between conversational and formal English and would have enough proficiency in English to hold a sustained discussion. However, this is not always the case, particularly when reduced learner–teacher interaction occurs in English as a second language (ESL) contexts. Using a sample of a selected group of students, this enquiry mainly aimed to explore the English discourse skills some students from isiXhosa language homes and communities brought to the university as well as the English proficiency they demonstrated at the 2nd-year level. With a particular focus on a selected group of 2nd-year students, I set out to explore the spoken and written English proficiency of the students as well as the strategies they adopted to improve their proficiency. The conclusions and strategies for remedial action are thereafter discussed.

ANAS S A ' I D U MUHAMMAD , Abdul Majid

Background: English writing among Nigerian students prove to be difficult at various academic levels; including pre-university and university levels. Precisely, poor command in English writing among Nigerian students hinders proper academic achievement of most undergraduates. Objective: The objective of the present article is to ascertain the level of variation in English writing among Nigerian undergraduate students' in terms of gender and in terms of major ethnic groups. Results: The findings indicated that the mean scores for the overall scores of the students' descriptive essay are at an average score. Conclusion: This study affirms that there is crucial need for intervention concerning Nigerian undergraduates' English writing. As such, the results of the findings are hopeful to contribute and provide insights to Nigerian education administrative personals, the national education boards, as well as the international education planners concerning ways of enhancing students' English writing.

University of Fort Hare

Thandiswa Mpiti

Adelia Carstens

Laston Mukaro , Annastacia Dhumukwa

順天堂スポーツ健康科学研究

Yumiko MIZUSAWA

Subadrah Madhawa Nair

Background: English writing among Nigerian students prove to be difficult at various academic levels; including pre-university and university levels. Precisely, poor command in English writing among Nigerian students hinders proper academic achievement of most undergraduates.Objective: The objective of the present article is to ascertain the level of variation in English writing among Nigerian undergraduate students’ in terms of gender and in terms of major ethnic groups. Results: The findings indicated that the mean scores for the overall scores of the students’ descriptive essay are at an average score. Conclusion: This study affirms that there is crucial need for intervention concerning Nigerian undergraduates’ English writing. As such, the results of the findings are hopeful to contribute and provide insights to Nigerian education administrative personals, the national education boards, as well as the international education planners concerning ways of enhancing students’ Englis...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences

JOSEPHINE DANIELS

International Journal of English and Literature

mulat guadie

Andrew Drummond

International Journal of Higher Education

Pineteh Angu

Precious Dube

Dedi Turmudi

Karoline Du Plessis

Betsy Gilliland

Job Mwakapina

Reading & Writing

Berrington Ntombela

Reading and Writing

Elaine R Silliman

Susan Ntete

Journal of English and …

Washington Dudu

Brigitte Lenong , Atrimecia Hass

Gastor Mapunda

International Journal on Integrated Education

USORO OKONO

Critical Inquiry in Language Studies

Journal of Education and Practice

Mary Karuri

Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP)

Md. Shamim Hossain Biswas

Teguh Budiharso

FAIS Journal of Humanities

Isa Yusuf Chamo

Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching

Brahim Ait Hammou

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Faculty of Humanities

- Engineering and the Built Enviroment

- Health Sciences

- myUCT Email

- Writing Center

- Dean's welcome

- Applications Overview

- Undergraduate Programmes

- Admission requirements

- Orientation

- Transferring students

- Postgraduate programmes

- Admission Requirements Overview

- Semester Study Abroad applicants

- Funding your Studies

- International applicants

- Recognition of Prior Learning

- Humanities Students' Council

- Matric Exemption

- Registration

- Student advisors

- Student mentorship

- Third Term Courses

- Getting started

- You & your supervisor

- Ethics & plagiarism

- Preparing to submit

- Postgraduate Student Council

- Academic excellence

- Academic exclusion

- Change of Curriculum

- Concessions

- Leave of Absence

- Academic Departments

- Umthombo Centre for Student Success

- UCT English Language Centre

- Research Overview

- Research Ethics

- Awards & Achievements

- Alumni Overview

- Fund the Performing and Creative Arts

- News archive

- Faculty Office Staff

- Emergency Contacts

Language students experience Xhosa culture, first hand

Each year, Dr Tessa Dowling takes a group of her Xhosa Communication students to Cata, a small rural village located near Qoboqobo in the Eastern Cape. The field trip is designed to immerse students in the culture and traditions of African family life, whilst enabling them to hone their language skills. It is also an emotional and eye-opening experience from which no one returns the same.

Cata, which in isiXhosa means ‘to add a small amount’, is a picturesque village located in the former Ciskei. From the 1930’s onwards, it was a site of traumatic forced removals and dispossesion under the apartheid government. “During apartheid, villagers were subjected to forced removals under the guise of a ‘betterment programme”. The aim being to reduce their wealth and confidence as powerful, successful farmers and to create division amongst an otherwise united community” says Dr. Dowling who is a senor lecturer in African Languages at UCT. In 2008, she was commissioned by the Border Rural Committee to establish language workshops for families who were hosting ‘homestays’ for foreign researchers but finding it difficult to teach their home language to their visitors. In this next extract, she describes the sights and sounds of Cata as well as her observations on the student summer field trip:

You wake up to the sound of people greeting each other with loud friendliness, reminding one of that Telkom advertisement “Molo, mhlobo wam!” where the two pensioners phone each other but still shout their greetings across the hills. Children, slightly dusty from playing with the piglets outside the house, crawl into bed with you and teach you, with an air of sophisticated tolerance: Yingubo (It is a blanket), Yifestile (It is a window) and laugh at the way you say their names “Olwethu” (ours), “Asekhona” (they are still around), “Siyabulela” (we give thanks). And go absolutely hysterical when you attempt a click “Yingxaki!” (It is a problem!) They follow you to the loo, which is just the other side of the spinach field, and hold the wobbly door shut while you pee, looking out across a view that is almost cheeky with undiscovered charm. This is the Xhosa Communication field trip, which in previous years has been generously financed by the Vice-Chancellor’s special fund. Once a year, from 2010 to 2012, I bundled up eager Xhosa Communication students, and took them to Cata, a tiny village just outside Qoboqobo (Keiskammahoek) near Qonce (King William’s Town).

I never knew exactly what they were expecting, my students, but after a 17-hour bus trip followed by a hilarious taxi ride into the village, the taxi driver inseparable from his cellphone and smilingly reassuring us – “Akhongxaki, akhongxaki” (no problem, no problem) – as he one-handedly lurched us across yet another pothole or weaved through a herd of sheep, the conversations about boyfriends and food and learning Xhosa turned into an oneiric hush as we swerved into the main street of Cata. My students suddenly realize it is two weeks here, and there isn’t a Woolworths in sight. Or a place to plug in a hairdryer. Or a loo that flushes. They are here for the reason they are here: to listen to Xhosa, to speak Xhosa, to dream in Xhosa, to make friends. And it works! These field trips have created softer, gentler, humbler students (the best kind for learning a language), more willing to admit their language skills will only improve if they integrate, try to communicate with people in a society where English is not that important, but water is.

The 2014 class have been hard at work all year fundraising for the next trip which is scheduled to take place in Januaury 2015. The group includes Xhosa first-language speakers who have not had the opportunity to learn their mother-tongue formally as a first language at school. There is also an ongoing research component to the Cata field trip. Dr Dowling will be in village next month as part of her research into language change in Xhosa. The first part of her study, which investigates the migration of Xhosa nouns and concords, has already been accepted for publication in the South African Journal of African Languages. The second part focuses on the use of Xhosa vocabulary and on the ways in which children assimilate English words into the urban Xhosa vocabulary. After studying language use in Cape Town, Dr Dowling observed that for instance instead of using the Xhosa word uphahla for roof, children use i-roof, instead of isiselo for drink they use i-drink. “I hope that what I discover will go some small way towards helping inform educational programmes and texts. Children need to learn the correct grammar and vocabulary of the language but educationalists also need to take into account that vocabularies shift and change all the time in all languages” says Dowling.

About Cata Cultural Village ‘Homestays’ in Cata afford the visitor an opportunity to stay with a family, sharing their food and experiencing their hospitality in exchange for a small fee. This type of accommodation arrangement is becoming increasingly popular with visitors to the Eastern Cape and simultaneously serves to boost the local economy. Cata Cultural Village coordinate eco-tours for vistors and there is a museum and

Africa Is a Country

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

The Xhosa literary revival

- Use + Republish + Donate

The writer Mphuthumi Ntabeni's new novel explores the deep history of colonialism and resistance in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash

When cooped-up critics and writers connect on social media, their conversations often demand more room. Such was the case in my correspondence with Mphuthumi “Mpush” Ntabeni, which migrated to various messenger platforms before finding its stride on email. We read each other’s books; we related them to other books; we grew an unlikely discussion of Catholic conversion narratives from a deep love of South African intellectual history. Talking to Ntabeni, it is anyone’s guess how one body of texts will lead to another. He is a literary wanderer par excellence, and yet he is far from unmoored. Born and raised in Queenstown, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, he now resides in Cape Town, where he has continued to nurture a far-ranging knowledge of Xhosa history and culture. His first novel, The Broken River Tent , reconstitutes the perspective of a real-life 19th-century chief named Maqoma, of the amaRharhabe branch of amaXhosa who lived west of the Kei River, and were thus among the first African people to encounter white settlers when they arrived on the Cape’s Eastern shores. Ntabeni’s book uses retrospective narration framed by present-day dialogue to offer a Xhosa point of view on that violent encounter, which gave rise to the century-long period of the Xhosa or Cape Frontier Wars (1779-1879) against the British and the Boers.

Published by South Africa’s Blackbird Books imprint in 2018, The Broken River Tent won the debut category of the University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English the following year. It is not an easy book to slip into: more of a series of conversational and historical collisions than a self-propelling plot, it pairs Maqoma with a contemporary figure named Phila to parse topics ranging from the relevance of psychoanalysis for Africans to the structure and material composition of frontier wagons. One could be forgiven here for recalling fellow South African J.M. Coetzee’s early novels ( In the Heart of the Country , especially), owing not least to Phila’s “hyperanalytical” disposition. Ntabeni’s style, however, is marked not by the stymying force of endless self-reflection, but by the exuberance of a mind eager to unfurl its abundant stores. A single paragraph of the book moves rapidly from Steve Biko to Soren Kierkegaard to the biblical Job, with its dialogue lubricated by cheap whiskey. This is Ntabeni’s approach to fiction in a nutshell: high-octane and expansively informed.

This interview took place on Google Docs between Baltimore and Johannesburg, where Ntabeni has just settled into a four-month writer’s fellowship at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study, housed at the University of Johannesburg. With lockdowns still in place internationally and his work on a third novel beginning in earnest, it seemed like the perfect time to present his ideas to the AIAC readership. What follows has been edited for clarity and flow.

I’m glad we are finally getting around to this, Mpush—your novel was one of the first I read when the pandemic lockdowns started. I know that it’s intended to be part of a trilogy, so I’ll jump right in by asking you what it is that appeals to you about that format for this project. Are you intentionally in dialogue with other famous African trilogies? (Achebe, Mahfouz, and Dangarembga all come to mind, though Okri is perhaps the closest to The Broken River Tent in its merging of spiritual and historical concerns.) Or is there some intrinsic quality of the trilogy that you see your story as making use of?

Well, I’m happy to be here and finally do this with you. Thanks for inviting me. The trilogy was not my original idea. Come to think of it, even writing a book was never my original intention. I was just eager to know about my own history and so I started researching it on my own. I knew very little about it because we had not really been taught it at school or at home. When I thought I had done enough and was even beginning to form my own opinions about it, I started asking myself how I could make other people aware of it, especially the ones directly affected by it, like myself. That is when the idea of the book came to mind. I didn’t want to just translate the material I found in the archives. I wanted to find a way of making that history live, resurrect it if you like, so that non-professional historians like myself would also be interested in it. There was also the issue of gaps in historical facts I found and wished to fill by what I call an “informed imagination,” that is, by inserting psychological and emotional energy into known or unknown historical facts without betraying their true spirit. In that way the genre of historical fiction chose me.

As for why this became a plan for a trilogy in particular, I realized at some point that I had accumulated too much historical data in my research. The task of tackling it through a narrative form became formidable. Then, one cold December day, while we were walking on the High Street of Edinburgh, my wife wanted to feed our daughter who was only a month old then. So, we left the snowy streets and quickly dashed into a restaurant for a meal, to give my wife also a chance to breastfeed the baby. As we sat there, looking through the window, I realized that we were sitting across from one of the places Tiyo Zisani Soga used to stay in while studying at the University of Edinburgh. ( Note to readers: Tiyo Soga was a 19th-century South African intellectual best remembered for translating the bible and John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress into isiXhosa ). Then the format of how to handle my research material came as a bolt of lightning to me. I would need to divide it into three thematic units: war, religion, and politics. The protagonist for the war section became obvious to me when I recalled that out of nine wars the amaXhosa fought with the British colonial government over 100 years, at least four of them were led by Maqoma , and he was physically present in five. This is why I used his biographical facts as the skeleton of my first book. Soga, the first Xhosa person to be educated in what we call Western education as a reverend, was also the obvious candidate for the religious section, which I’m currently busy with. And S.E.K Mqhayi (1875-1945), the poet, essayist, biographer, and newspaper editor during the foundations of political resistance that led to the foundation of the ANC, also became an obvious choice for me. I wish to call the trilogy “The River People,” and The Broken River Tent is its first installment.

My writing influences are myriad. In fact, I still consider myself an avid reader who acquired an opinion about the events of our history more than I consider myself to be a writer. I like that it is mostly my readers who make me aware of the literary influences on my writing, more than I do myself. I recall being surprised when a brilliant interviewer asked me if I considered The Broken River Tent to be magic realism. I honestly had never thought of it that way, but as I began doing so I saw her point, especially in the section when Maqoma gets a visit from Nxele in Robben Island. I suspect it is also the reason why you see Ben Okri’s influences on my writing, perhaps more with The Famished Road than any other of his works. The Chinua Achebe reference is understandable since we both write about the impact of colonialism on native culture and history. I also learnt a wonderful trick from him of titling books with lines from popular poets.

I want to get back to Soga, so hold that thought. First, though, it also strikes me that you try, in The Broken River Tent , to approximate the cadences and “feel” of Xhosa speech as well as including passages of isiXhosa. This deliberate Africanization of English is often cited as one of Achebe’s key postcolonial innovations. Can you say a bit more about what this technique entailed, for you?

I guess no one can bring forth an African voice in literature without adopting the African traditional style of speaking in proverbs and all. I don’t know how Achebe wrote his characters in his head, but I was deliberate in hearing Maqoma’s voice in Xhosa in mine, before translating it into English. This is why his English is different to that of other people in the novel, like Phila who has been educated in Western ways. I wanted Maqoma’s voice to have raw Xhosa intonations. I felt lucky in the sense that Xhosa is a singing language, so I wanted to translate that for non-Xhosa speakers so that they might be able to understand how the language, like most ancient and classical languages, sings. My sister says I Xhosalized English, and I find this phrase endearing. I was also happy that someone at least noticed the effort I tried to make with Maqoma’s voice. Much of it is acquired from a Xhosa imbongi style of praise singing. Mqhayi has been very helpful in my learning to acquire that voice. I also learn a lot from the Gaelic ancient languages, like Irish shamans and Scottish Picts, my other learning obsessions. I find a lot of commonality in how they infuse English with traits of their traditional languages, which is what gives them distinct and unique ways of speaking English mixed with their mother tongues. I’m afraid I’ll never stop bragging about the richness of the Xhosa language if you don’t stop me…

Brag away! You fill me with regret that I didn’t stick with Xhosa beyond an intro course. And I think that you are onto something important, here, about the significance of your role as a specifically Xhosa novelist to the fractious tradition of South African literature broadly. Black South African writing is most often associated with the urban, the cosmopolitan, and the “modern,” from the trope of “Jim Comes to Joburg” in the mid-20th-century; through the “Drum generation” as it flourished in the 1960s; to the Soweto novels of the 1970s and 1980s; and right up to post-apartheid figures like Phaswane Mpe and K. Sello Duiker . And yet, as you suggest with your reference to Tiyo Soga, there is a much longer and less widely read history of culturally differentiated South African writing; it isn’t simply “English,” “Afrikaans,” and “Black,” as one often hears. I am thinking even of A.C. Jordan here, whose 1940 novel Wrath of the Ancestors , as you well know, deals not so much with overt questions of racial or national identity but with intra-cultural dynamics. The historical tensions within “Xhosaness” are also something you explore in The Broken River Tent . My question, then, is this: has South African literature reached a point where there is room for more prominent literary experimentation in a wider range of constituent traditions? What, in other words, is the relationship between Mpush Ntabeni the Xhosa novelist and Mpush Ntabeni the South African one?

This is an interesting question that I doubt I’ll be able to answer, but I’m going to give it a go. I think all writing cultures that write in English, not as a mother tongue, or perhaps it is better to say those whose background is not necessarily Anglo-Saxon, have a love/hate relationship with the language. Though they understand its usefulness as a lingua franca, they tug on the leash of its dominance and hegemony. They also sometimes find it to be an insufficient means to express their own philological roots. I am not even talking about the language politics here, which Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues convincingly even though proper solutions still elude him also. I am talking about the sheer frustration of someone who has been raised and nurtured in say, German or Xhosa, with a much more comprehensive variety of words and phrases to transmit the spirit of their thoughts precisely and succinctly in their own language, and which often are not translatable to English. ( Note to readers: The character of Phila in TBRT was educated in South Africa and Germany .) When writing The Broken River Tent , whenever I encountered that challenge, I chose to use the Xhosa or German phrase alongside what I regarded as a weak explanation of its meaning in English. I don’t see why I should rob words/phrases of the richness of their meaning just to serve the monolinguist.

To answer your question properly, though, the genius of the English language, why it became so popular, I think, is because it is adaptable. It gleans words from various languages to enrich its vocabulary. There’s no reason why that adaptability should only be limited to Germanic, Frank, and Latin languages when English is also spoken in Africa and Asia. South African literature therefore has no choice but to adapt also, it must grow its African roots, and those cannot only be limited to Afrikaans when this country has 11 official languages. Of course, the attitude of some gatekeepers within the publishing industry is not completely convinced about this. They still come with tendencies of recognizing only occidental trends as seeds of progress. But they’ll be compelled by the ruthless hand of necessity.

My going back to the roots of our literature, I mean beyond the so-called Drum Renaissance, was necessitated by my handling of our older historical material. I guess you can say it was serendipitous in that sense. But it was deliberate also. I feel the writings of the Drum generation are too American, black US American to be precise. I hold nothing against them doing what they needed to do with the tools at their disposal then. In fact, I dream of writing a literary biography of Bloke Modisane one day as my excuse to interrogate the zeitgeist of that era, but that’s a topic for another time. Then our cultural issues developed into political ones for the necessary expediency of our freedom. I think it incumbent on us now to revisit our unresolved cultural issues for the sake of mending our identity, especially the crucial parts that were vandalized by colonialism. Your Jordans and your Jolobes interest and influence me more because they were dramatizing Xhosa oral history. To date it is very difficult to distinguish between their writings and that of J.H. Soga, who wrote non-fiction books like The South-Eastern Bantu . J.J.R Jolobe and your Mqhayi dramatize that history in their books. Not only that, they also close the gaps by what I have called their informed imagination. Hence their narrative tonality is closer to the oral history and recitations by imbongi of the amaXhosa because they wrote closer to the transitional period when all that was changing. This is why at this moment of my writing they interest me more than the Drum generation. I find in them a certain Xhosa literary tradition that got truncated into the Americanized cosmopolitanism of the Drum era when our writers moved to the big cities. I wish to trace and follow that tradition. By the way, I was named by my paternal grandpa, who taught himself how to read through Jordan’s book. Hence, I am called Mphuthumi, after the wise counselor of the king in Ingqumbo Yeminyanya .

This is a fascinating response, especially seeing as there are such tricky questions circulating right now about the uses and limitations of a US-originating racial vocabulary in articulating social justice claims within African contexts. I’m quite drawn to your idea of returning through reading and writing to a truncated but robust intranational tradition, veering off course from the more typical emphasis on South Africa’s international visibility during the apartheid years. It suggests a way of getting some intellectual distance from what can feel like overwhelmingly urgent political and cultural entanglements, at the same time as it speaks directly to some of their most prominent concerns: the decolonization of knowledge, black cultural reclamation, and language justice. In this way, The Broken River Tent is quintessential of the historical novel genre, reconstituting the past to advance crucial claims on the present. It also partakes in an ongoing “boom” of African historical fiction, appearing within the same few years as Fred Khumalo’s Dancing the Death Drill (2017), Ayesha Harrunah Atta’s The Hundred Wells of Salaga (2018), and Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light (2019), to name just a few examples. The Broken River Tent , however, does something bold and unusual: it introduces Maqoma as a character in the present, while leaving what we might call his “historicity” intact (his speech, frames of reference, etc.). What motivated this choice, and how would you describe your particular (and wonderfully peculiar) re-engineering of the historical novel?

In the first draft of my manuscript Maqoma was the one telling the story alone. It felt too monologic and like an excuse to retell historical events that affected his life. It was missing the element of clear impact on current events and the status quo of our history. I needed a way to visibly link our present status quo as consequences of those historical events. That is how Phila was born, a character that would not only ask questions to suss out what we need to know from history, but that would also provide a historical tour of the present-day situation to Maqoma and his past era. I am sure you’re aware of this trick from Dante, how he used the ancient poet, Virgil, as his tour guide to his imagined life after death. Because I wanted to talk about this life, I re-tooled that trick a little and made it so that it is Maqoma who comes back as an ancestor to help Phila in this life.

The idea of ancestors as guides for the living is prominent in Xhosa spirituality. Our culture is impatient with numinous things that only speculate about life after death with no bearing on the present situation. I’ve since been pleased to discover that Diana Gabaldon has done a similar thing on her Scottish Outlander historical novels that have been turned into a popular TV series in the UK. I am also aware of the African historical novels you mention though I wanted to introduce the element of what others are now calling magic realism, most popular in Latin American literature of the likes of Gabriel García Márquez. Somehow, he definitely influenced me because I had a period in my life when I was obsessed with his writings, which I had forgotten.

My aim was to also expose the truth of rootlessness even on those who are educated if they’ve no solid sense of their own identity. You know the proverbial saying about a tree without roots. The presence of Maqoma in our times was to give Phila a cultural background and deeper sense of his own identity as a means to assuage his weltschmerz , world-weariness. So, in a way, the book is some sort of bildungsroman for Phila whose character starts out slightly emotionally stunted, something I hope is clear in how he relates to his girlfriend Nandi.

I so admire the easy breadth of your references and reading, which also comes through in the novel itself. This feels like an important reminder that there is no need to choose between centering African traditions and richly engaging with others, Western or not. I want to return, though, to this matter of “roots” and “rootlessness,” which you’ve referenced a few times here. There is a certain skepticism, in your work, of secular and cosmopolitan ways of viewing the world, and particularly of secular modernity’s propensity to find meaning primarily in the self. (It’s no coincidence that Nandi is a psychologist.) While there is, of course, a long record of “troubling” modernity in African writing, you have also been open about your debt to the Catholic intellectual tradition. We might, then, go further afield and think about The Broken River Tent alongside some classic Catholic texts and writers for whom rootlessness was also a paramount concern—G.K. Chesterton, Evelyn Waugh, even Graham Greene in his attempts to work through the mechanics of redemption in a British colonial setting. How has this part of your life informed your fictional practice, in ways that might be surprising to some readers?

Thanks for the complements. I get worried when people, more influenced by so-called “cancel culture,” think the process of, say, decolonizing ourselves means that we need to disregard all Western thinking in order to allow African thought to emerge. As if African thought and vision is too weak to stand its own ground against other world streams of thought. In fact, as a staunch humanist, I strongly believe that global thought, Goethe’s world literature if you like, awaits African thought traditions to be properly assimilated to it.

The human condition is my preoccupation. I have also invested a lot of learning in classical literature. And yes, there was a time classical literature was used as a weapon to propagate imperialism, patriarchy and all that rubbish whose aim was to put a white male on the pedestal to be worshipped and admired. But there’s so much more in it there that speaks to the human condition, including the African condition, that it seems to me a disservice to just throw its baby out with the dirty water of occidental historic faults. So much of it also can be used, and is being used, to counteract all of its wrongs. Hence you see this exciting bloom of the retelling of Homeric stories in particular from the feminine point of view by the likes of Madeline Miller, Pat Barker, and Natalie Heyns, among others. You earlier mentioned Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light , and I am sure you noticed that she has also begun to turn toward ancient classical themes and language to depict the African human condition. Chigozie Obioma, in The Orchestra of Minorities does the same. You shall notice in my next novel, The Wanderers [to be published in April/May] , that I delve into this a little deeper also, to depict the notion of the absurdity of the human condition, which though popularized by Albert Camus, and elaborated through thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard (another strong influence in my thinking), goes back to the classical era of literature and is a Socratic imperative. Camus was greatly influenced by the church fathers, St Augustine in particular. My thinking is also greatly influenced by Augustine. In fact, my conversion to Catholicism has something to do with my immersion into history. Perhaps the major difference between Camus and me is that the absurdity of the human condition has never managed to extinguish the flame of hope within me, not yet anyway. In fact, I define hope as that mysterious and incomprehensible energy that remains in a person when human reason has been defeated by the absurdity of their human condition. Chesterton, of course, is necessary in religious thinking in particular, so that one doesn’t take oneself too seriously to their detriment.

You formulate this belief in decolonization as cultural capaciousness so passionately, and it calls to mind the famous quote by the Roman playwright Terence, himself an African and freed slave: “I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me.” It is, of course, easy enough to cite this in a pat and cliche way, as a conversation-ending shortcut to universalism rather than as a reminder of how much work it takes for a writer to approach something like what you call “the human condition.” I take you to be suggesting that African writers, far from being peripheral to humanism, may in fact have a particular claim to its fulfillment. The title of your forthcoming novel, The Wanderers, is resonant here as well, because it is also the title of a sprawling and ambitious 1971 novel by Es’kia Mphahlele. In this light, what goals for African writing and critical thought broadly do you see your work as advancing? And, more specifically, where do you feel most “at home” within the current South African and continental publishing landscape?

I am extremely happy you picked up my association with the quote of Terence, because I had it exactly in mind when I mentioned my preoccupation with the human condition. And yes, I strongly believe the humanistic thread of world thought will only be fulfilled by something whose seed is the African life attitude of ubuntu . And yes, there are deliberate parallels on my forthcoming work with that of the late professor Es’kia Mphahlele in that they’re both exile novels, with mine in Tanzania whereas his was in Nigeria. But far be it to me to dictate where my work will eventually end up within African writing. That will depend on my readers and the generation that follows us if we’re lucky enough to be of any interest to them. For now, I feel my writing experience is drawing me towards the fractured narratives that are part of our heritage we dropped during the early parts of the 20th century and before. I feel part of our true literary roots are left stranded there and calling to be assimilated to our contemporary thoughts.

Within the current trend of continental publishing it would seem as if Nigeria is the continental trend setter for African literature. There might be many things informing this, like the fact that it is the most populated country on the continent, and so has more people in the diaspora also. And the migrant story is the flavour of the day in the global literary market. But I like what Ghana writers, who by the way you introduced me to, like Nana Oforiatta Ayim, are doing in books such as her debut The God Child , infusing philosophical and psychological substance in their writing that gives its literature more gravitas, rather than merely writing about big social issues without treating them with the deeper thinking they deserve. The charge I am making here is that made by James Baldwin against American writers, “… that they do not describe society, and have no interest in it. They only describe individuals in opposition to it, or isolated from it.” Most of our African migrant writers, especially those writing from the US, seem to have caught this disease. Like Baldwin I am beginning to find fault with it.

As for South Africa, the only way for us to move beyond the schizophrenic bipolar nature of our literary identity is by respecting what came before. It is imperative that we honestly deal with our past in order to gain our roots, a true sense of identity we can successfully depict as our assimilated literature tradition. This separate literary development of the Afrikaans of Afrikaners doing its own things, and that of colored writers doing another, or the black Africans doing theirs, though good for diversity, has not provided us with an assimilated national literary voice also, hence I call it schizophrenic. The problem is we’ve not yet distilled our identities deeply enough to go beyond politics into the understanding of not only our commonalities but our indispensability to each other also. And going to our historical foundations helps us rediscover this.

While I am tempted to go off on a tangent about Ghanaian writing, here, this seems like an ideal and provocative place to stop and let readers process the many points you’ve raised about how literary traditions can and should enrich each other, about the primacy of African histories for seeing that such exchange happens justly, and about historical legacies both recent and long past. I am sure that many readers will also want to read these issues’ fuller exposition in The Broken River Tent ! I, for one, am grateful to you for lending me your mind across these hours on other sides of the earth, and eagerly await publication of The Wanderers . Enkosi, Mpush.

Wonderful, Jeanne. Thanks for taking time to read The Broken River Tent and talk to me about it. Now that I am busy with my third manuscript, I feel The Broken River Tent is still the book that gave me the most trouble with research and writing process. It tested not only my intellectual but psychological strength also. I was not ready to encounter the rawness of the archives. It took some getting used to working with the material objectively, disregarding the anger it provoked in me as a Xhosa person, because hardly any of these historical sources ever try to see things from the perspective of the amaXhosa. That is what inspired me to write the book, that wanting to tell things, for once, from our perspective.

Further Reading

Letters of resistance

- Athambile Masola

An anthology series, Women Writing Africa , restores women’s writing to the public archive.

A Revolution in Many Tongues

- Mukoma wa Ngugi

There is not a single journal devoted to literary criticism in an African language or any writer residencies that encourage writing in African languages.

African poets for Africa

Badilisha is rare: an African project funded by a mix of government and private art donors, facilitating media access to African poets.

The most interesting bits

- Orlando Reade

Kaleidoscope magazine has done an “Africa” issue; it wants to walk a fine line between identity politics and universalism.

Xhosa in 45 minutes

Permanent link to this item, journal title, link to journal, journal issn, volume title.

University of Cape Town

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/

Description

Dowling, T. 2014-08-22. Xhosa in 45 minutes. Collection. University of Cape Town.

Collections

DSpace software copyright © 2002-2024 LYRASIS

- Constructed scripts

- Multilingual Pages

Xhosa ( isiXhosa )

Xhosa is a Bantu language spoken in South Africa, mainly in the Eastern Cape, Western Cape, Free State and Northern Cape. It is also in parts of Lesotho and Zimbabwe. According to the 2011 census there are about 8.2 million native speakers of Xhosa, and another 11 million second language speakers.

Xhosa at a glance

- Native name : isiXhosa [isikǁʰɔ́ːsa]

- Language family : Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Benue-Congo, Southern Bantoid, Bantu, Southern Bantu, Nguni, Zunda

- Number of speakers : c. 19 million

- Spoken in : South Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho

- First written : 1823

- Writing system : Latin script

- Status : official language in South Africa and Zimbabwe

Xhosa is an official language in South Africa and Zimbabe, and is used as a language of instruction in primary schools, and in some secondary schools. It is also taught in universities. There are books, magazines and newspapers in Xhosa, as well as TV and radio programmes, films, plays and songs.

Xhosa is closely related to Zulu , Swati and Ndebele , and mutually intelligible with them to some extent.

Xhosa's click consonants were most likely borrowed from the Khoisan languages as a result of long and extensive interaction between the Xhosa and Khoisan peoples.

A system for writing Xhosa using the Latin alphabet was devised by Christian missionaries during the early 19th century. The first printed work in Xhosa was published in 1823.

Xhosa alphabet

Hear the Xhosa alphabet:

Xhosa pronunciation

Hear how to pronounce Xhosa:

Download an alphabet chart for Xhosa (Excel)

Sample text in Xhosa

Bonke abantu bazalwa bekhululekile belingana ngesidima nangokweemfanelo. Bonke abantu banesiphiwo sesazela nesizathu sokwenza isenzo ongathanda ukuba senziwe kumzalwane wakho.

Translation

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. (Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

Some corrections to this page by Michael Peter Füstumum

Sample video in Xhosa

Information about Xhosa | Phrases | Numbers | Colours | Family words | Tower of Babel | Books about Xhosa on: Amazon.com and Amazon.co.uk [affilate links]

Information about the Xhosa language http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xhosa_language https://www.ethnologue.com/language/xho

Online Xhosa lessons https://www.memrise.com/course/1572/xhosa-an-intro/ http://learn101.org/xhosa.php http://ilanguages.org/xhosa.php http://xhosaculture.co.za/about-us/learn-xhosa/ http://www.youtube.com/user/XhosaKhaya https://www.twinkl.co.za/resources/south-africa-resources/isixhosa-foundation-phase-english-south-africa-suid-afrika/2

Online Xhosa dictionaries http://www.freelang.net/dictionary/xhosa.php http://glosbe.com/en/xh/ http://www.gononda.com/xhosa/

Xhosa phrases http://www.salanguages.com/isixhosa/xhowrd.htm http://www.southafricalogue.com/travel-tips/south-african-phrases-xhosa.html

Bantu languages

Bangi , Basaa , Bemba , Bena , Benga , Bhaca , Bukusu , Bulu , Central Teke , Chichewa , Chokwe , Chuwabu , Comorian , Digo , Duala , Eton , Ewondo , Fang , Ganda/Luganda , Gogo , Gusii , Gwere , Haya , Herero , Ikizu , Jita , Kamba , Kiga , Kikuyu , Kimbundu , Kinyarwanda , Kirundi , Kisi , Kongo , Konjo , Koti , Kukuya , Kunda , Kuria , Lambya , Lingala , Loma , Lozi , Luba-Katanga , Luchazi , Lunda , Luvale , Makaa , Makonde , Makhuwa , Mandekan , Maore , Masaaba , Mbunda , Mende , Mongo , Mushungulu , Mwani , Nambya , Nande , Nkore , North Teke , Northern Ndebele (South Africa) , Northern Ndebele (Zimbabwe) , Northern Sotho , Nyamwezi , Nyakyusa , Nyemba , Nyole , Nyungwe , Nzadi , Oroko , OshiWambo , Pagibete , Punu , Ronga , Sena , Sengele , Shona , Soga , Songe , Southern Ndebele , Southern Sotho , Sukuma , Swahili , Swati , Tanga , Tembo , Tonga , Tshiluba , Tsonga , Tswa , Tswana , Tumbuka , Umbundu , Venda , Xhosa , Yao , Yasa , Zigula , Zinza , Zulu

Languages written with the Latin alphabet

Page last modified: 17.08.22

728x90 (Best VPN)

Why not share this page:

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways . Omniglot is how I make my living.

Get a 30-day Free Trial of Amazon Prime (UK)

- Learn languages quickly

- One-to-one Chinese lessons

- Learn languages with Varsity Tutors

- Green Web Hosting

- Daily bite-size stories in Mandarin

- EnglishScore Tutors

- English Like a Native

- Learn French Online

- Learn languages with MosaLingua

- Learn languages with Ling

- Find Visa information for all countries

- Writing systems

- Con-scripts

- Useful phrases

- Language learning

- Multilingual pages

- Advertising

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Examples >

- Essay Topics

Essays on Xhosa

1 sample on this topic

The array of written assignments you might get while studying Xhosa is stunning. If some are too challenging, an expertly crafted sample Xhosa piece on a related topic might lead you out of a deadlock. This is when you will definitely praise WowEssays.com ever-expanding collection of Xhosa essay samples meant to ignite your writing enthusiasm.

Our directory of free college paper samples showcases the most striking instances of excellent writing on Xhosa and relevant topics. Not only can they help you develop an interesting and fresh topic, but also exhibit the effective use of the best Xhosa writing practices and content structuring techniques. Also, keep in mind that you can use them as a trove of authoritative sources and factual or statistical information processed by real masters of their craft with solid academic backgrounds in the Xhosa area.

Alternatively, you can take advantage of effective write my essay assistance, when our writers provide a unique example essay on Xhosa tailored to your individual requirements!

The role of Xhosa traditional circumcision in constructing masculinity

- November 2016

- South African Journal of Psychology 47(3)

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- University of the Western Cape

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Gregorius Abanit Asa

- Anthony Brown

- Dostin Lakika

- Thanduxolo N.

- Moeketsi Letseka

- Azwihangwisi H. Mavhandu-Mudzusi

- Ian Burkitt

- Vivien Burr

- Kenneth J. Gergen

- Michael Gilsenan

- V. W. Turner

- Katharine Wood

- Rachel Jewkes

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- Environment

- Information Science

- Social Issues

- Argumentative

- Cause and Effect

- Classification

- Compare and Contrast

- Descriptive

- Exemplification

- Informative

- Controversial

- Exploratory

- What Is an Essay

- Length of an Essay

- Generate Ideas

- Types of Essays

- Structuring an Essay

- Outline For Essay

- Essay Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Body of an Essay

- Writing a Conclusion

- Essay Writing Tips

- Drafting an Essay

- Revision Process

- Fix a Broken Essay

- Format of an Essay

- Essay Examples

- Essay Checklist

- Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Write My Essay

- Custom Essay Writing Service

- Admission Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Essay

- Academic Ghostwriting

- Write My Book Report

- Case Study Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Do My Assignment

- Buy College Papers

- Capstone Project Writing Service

- Buy Research Paper

- Custom Essays for Sale

Can’t find a perfect paper?

- Free Essay Samples

Xhosa people

Updated 24 April 2021

Subject Identity , Myself

Downloads 106

Category Life , Sociology

Topic Generation , Minority , Values

From generation to generation, the moral, religious and political values of a culture are handed on.

Economic activity, works cited.

Deadline is approaching?

Wait no more. Let us write you an essay from scratch

Related Essays

Related topics.

Find Out the Cost of Your Paper

Type your email

By clicking “Submit”, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy policy. Sometimes you will receive account related emails.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

Xhosa and Ndebele People

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Xhosa and Ndebele People. (2020, May 06). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay

"Xhosa and Ndebele People." StudyMoose , 6 May 2020, https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay

StudyMoose. (2020). Xhosa and Ndebele People . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay [Accessed: 17 Jul. 2024]

"Xhosa and Ndebele People." StudyMoose, May 06, 2020. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay

"Xhosa and Ndebele People," StudyMoose , 06-May-2020. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay. [Accessed: 17-Jul-2024]

StudyMoose. (2020). Xhosa and Ndebele People . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/xhosa-and-ndebele-people-essay [Accessed: 17-Jul-2024]

- Do Guns Kill People or Do People Kill People Pages: 5 (1417 words)

- Communities shape the way people think about themselves and the people around Pages: 6 (1568 words)

- Democracy Is Created by the People and for the People Pages: 5 (1399 words)

- "Neat People vs Sloppy People" analysis Pages: 3 (825 words)

- Rich People From Poor People English Language Pages: 18 (5400 words)

- Equality Of People In Society Or Keeping People Under Control Pages: 7 (1906 words)

- Organization Need People or People Need Organization Pages: 4 (928 words)

- People should try to help other people that is why they have Pages: 2 (500 words)

- Hurt People Hurt People: An Exploration of the Cycle of Hurt Pages: 2 (486 words)

- Sloppy People vs Neat People: An Exploration of Morality Pages: 3 (618 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

Thesis Statement for Personal Essay

Thesis statement generator for personal essay.

Personal essays are intimate reflections, weaving together narratives and insights to deliver profound messages. Central to these essays is the thesis statement — a guiding beacon that directs the narrative and offers clarity to readers. Crafting a resonant thesis for a personal essay requires introspection and a deep understanding of one’s own journey. This guide will illuminate the path to writing compelling thesis statements for personal essays, complete with examples and expert tips.

What is a Personal Essay Thesis Statement? – Definition:

A personal essay thesis statement is a concise expression of the central theme or primary insight of the essay. Unlike thesis statements in more formal academic papers, a personal essay’s thesis often captures an emotion, lesson learned, or a core truth about the writer’s experience. It provides readers with a glimpse into the essence of the writer’s story and sets the stage for the unfolding narrative.

What is the Best Thesis Statement Example for Personal Essay?

While the “best” thesis statement for a personal essay would depend on the specific topic and the individual’s experience, here’s a general example:

“Through the winding journey of self-discovery amidst challenges, I realized that embracing vulnerability is not a sign of weakness, but rather a testament to the strength of the human spirit.”

This final thesis statement encapsulates a personal insight while hinting at a narrative of challenges and self-discovery, drawing readers into the essay’s deeper exploration of the topic.

100 Thesis Statement Examples for Personal Essay

Size: 201 KB

Personal essays are windows into the author’s soul, glimpses of moments, lessons, and reflections that have shaped their journey. The good thesis statement in these essays is more than just a mere statement; it’s the heartbeat of the narrative, encapsulating the essence of the tale and the wisdom gleaned from it. Let’s explore a collection of thesis statements, each weaving its unique tapestry of human experience.

- “The echoes of my grandmother’s stories taught me the power of legacy and the importance of preserving memory.”

- “Navigating the turbulent waters of adolescence, I discovered the anchoring power of self-acceptance.”

- “In the silent corridors of grief, I unearthed the profound strength that lies in vulnerability.”

- “The tapestry of my multicultural upbringing illustrated the beauty of diversity and the bridges it can build.”

- “Amid the cacophony of urban life, the serenity of nature became my sanctuary and muse.”

- “Love, in its many shades, revealed to me that it is more about giving than receiving.”

- “Facing the monolith of failure, I realized it’s but a stepping stone to success.”

- “The journey from solitude to loneliness taught me the invaluable nature of genuine connections.”

- “Chasing dreams on the canvas of a starlit sky, I learned that ambition has its roots in passion, not just success.”

- “The silent conversations with my reflection taught me the transformative power of self-love.”

- “In the crossroads of life’s decisions, I discovered that intuition often holds the compass to our true north.”

- “The rhythms of dance became my language, translating emotions words often couldn’t capture.”

- “Wandering through foreign lands, I understood that home isn’t a place but a feeling.”

- “The unraveling of old beliefs led me to the mosaic of perspectives that color the world.”

- “In the realm of dreams, I grasped the significance of perseverance and the magic of belief.”

- “As seasons changed, so did my understanding of the impermanence of life and the beauty it holds.”

- “The melodies of my mother’s lullabies became the soundtrack of my resilience and hope.”

- “In the pages of forgotten diaries, I retraced the evolution of my thoughts and the depth of my growth.”

- “The culinary adventures in my grandmother’s kitchen were lessons in love, tradition, and the art of giving.”

- “Amidst life’s cacophony, the whispering pages of books became my escape and my anchor.”

- “Through the lens of my camera, I captured the transient nature of moments and the eternity they hold.”

- “The mosaic of friendships over the years showcased the fluidity of human connections and their timeless essence.”

- “Under the shade of ancient trees, I learned patience, growth, and the cycles of life.”

- “The footprints on sandy shores traced my journey of introspection and the tides of change.”

- “In the embrace of twilight, I unraveled the beauty of endings and the promises they carry.”

- “From handwritten letters, I unearthed the magic of words and the bridges they create across distances.”

- “The undulating paths of mountain hikes mirrored life’s ups and downs, teaching me resilience and wonder.”

- “Within the hallowed halls of museums, I discovered humanity’s quest for expression and the stories etched in time.”

- “The serendipities of chance encounters taught me the universe’s uncanny ability to weave tales of connection.”

- “In the garden’s bloom and wither, I saw life’s ephemeral nature and the rebirth that follows decay”

- “The tapestry of city sounds became my symphony, teaching me to find harmony in chaos.”

- “Between the pages of my journal, I discovered the transformative power of reflection and the stories we tell ourselves.”

- “In the heartbeats of quiet moments, I recognized the profound value of stillness in a world constantly in motion.”

- “Through the myriad hues of sunsets, I learned that endings can be beautiful beginnings in disguise.”

- “The labyrinth of memories illuminated the idea that our past shapes us, but doesn’t define us.”

- “The first brush strokes on a blank canvas taught me the courage to start and the potential of the unknown.”

- “In the aroma of rain-kissed earth, I found the connection between nature’s simplicity and life’s profound moments.”

- “The gentle tug of ocean waves mirrored the ebb and flow of emotions and the healing power of letting go.”

- “Amidst the ruins of ancient civilizations, I grasped the timeless human desire to leave a mark and be remembered.”

- “The resonance of old songs brought back memories, revealing how art transcends time, reminding us of who we were.”

- “In the mirror of my parents’ aging faces, I saw the passage of time and the stories etched in every wrinkle.”

- “The spontaneity of impromptu road trips unveiled the joy of unplanned adventures and the paths less traveled.”

- “The aroma of childhood meals evoked memories, teaching me that senses can be portals to the past.”

- “From the heights of skydiving, I felt the exhilarating blend of fear, freedom, and the joy of being alive.”

- “In the cadence of poetry, I learned the power of words to heal, inspire, and transport to different realms.”

- “The play of shadows and light during an eclipse taught me about life’s dualities and the balance they bring.”

- “The laughter and tears shared with friends showcased the depth of human connection and the shared threads of our stories.”

- “Amidst the solitude of silent retreats, I discovered the voice within and the wisdom it holds.”

- “Through the changing vistas of train journeys, I realized life is less about destinations and more about the journey.”

- “The cycles of the moon became my reflection on the phases of life and the beauty in its transitions.

- “In the silent flight of a butterfly, I witnessed the delicate dance of change and the beauty of metamorphosis.”

- “The melodies of street musicians became my muse, illustrating the universal language of passion and art.”

- “Within the pages of fairy tales, I unraveled deeper truths about hope, bravery, and the magic within us all.”

- “The fragility of a snowflake mirrored the fleeting moments of life, urging me to cherish each one.”

- “Through the lens of history, I understood the cyclical nature of time and the lessons it persistently offers.”

- “Amid the vastness of deserts, I felt the weight of solitude and the freedom it silently gifts.”

- “In the embrace of night’s silence, I learned to listen to my inner voice, undistracted by the day’s clamor.”

- “The ritual of morning coffee became a meditation, teaching me to find joy in simple routines and moments.”

- “The constellation of stars in the night sky showed me the beauty of small lights in vast darkness.”

- “In the hustle of marketplaces, I perceived the intricate dance of life, commerce, and shared human experience.”

- “The whispers of old trees carried tales of time, resilience, and the secrets of unwavering growth.”

- “From the peaks of mountains, I felt the world’s vastness and my tiny yet significant place within it.”

- “The riddles of childhood games taught me the joys of curiosity and the journey of seeking answers.”

- “The seasons’ rhythmic dance became my muse, reflecting life’s constant change and the beauty in every phase.”

- “In the flicker of candle flames, I felt the warmth of hope and the luminescence of undying spirit.”

- “The ever-expanding universe became a metaphor for boundless possibilities and the mysteries yet to be unraveled.”

- “The resonance of church bells reminded me of the call to introspect and find solace within.”

- “The chorus of chirping birds at dawn became an ode to new beginnings and the melodies of nature.”

- “In the winding paths of forests, I discovered life’s unexpected turns and the revelations they bring.”

- “The myriad hues of a painter’s palette echoed the diversity of human emotions and the art of expressing them.

- “Beneath the veil of city lights, I discerned the contrast between loneliness in crowds and solace in solitude.”

- “In the ripples of a serene pond, I realized that even the smallest of actions can have far-reaching effects.”

- “The ballet of autumn leaves taught me about graceful endings and the promise of rebirth.”

- “From the labyrinths of ancient libraries, I uncovered the timelessness of knowledge and human quest for understanding.”

- “Through the whispers of midnight winds, I felt the comforting presence of the unseen and the mysteries of the night.”

- “In the patchwork quilt passed down generations, I recognized the warmth of stories and the fabric of shared memories.”

- “The ascent and descent of tides taught me about life’s cyclical nature and the inevitability of change.”

- “Amidst the aroma of old bookstores, I discovered portals to different worlds and the eternal allure of stories.”

- “In the footprints on a snowy path, I saw the transient nature of moments and the lasting impressions they leave.”

- “The harmonies of a choir became an emblem of unity, diversity, and the beauty of voices coming together.”

- “The transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly illuminated the wonders of change and the potential within us all.”

- “From the symphony of city streets, I deduced that every individual has a story, waiting to be told.”

- “The unfurling of a rosebud spoke of patience, time, and the elegance in gradual blooming.”

- “In the dance of shadows during twilight, I grasped the interplay between light and dark in our lives.”

- “The handwritten notes in the margins of used books unveiled strangers’ thoughts and the universality of human reflections.”

- “Amidst the patterns of falling rain, I perceived nature’s rhythm and the cleansing it offers.”