Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Latin American Research Review

- > Volume 36 Issue 1

- > Mexican Immigration to the United States: Continuities...

Article contents

Mexican immigration to the united states: continuities and changes.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

This research note examines continuities and changes in the profile of Mexican migration to the United States using data from Mexico's Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica, the U.S. Census, and the Mexican Migration Project. Our analysis generally yields a picture of stability over time. Mexico-U.S. migration continues to be dominated by the states of Western Mexico, particularly Guanajuato, Jalisco, and Michoacán, and it remains a movement principally of males of labor-force age. As Mexico has urbanized, however, out-migration has come to embrace urban as well as rural workers; and as migrant networks have expanded, the flow has become less selective with respect to education. Perhaps the most important change detected was an acceleration in the rate of return migration during the early 1990s, reflecting the massive legalization of the late 1980s.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

- Google Scholar

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 36, Issue 1

- Jorge Durand (a1) , Douglas S. Massey (a2) and René M. Zenteno (a3)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0023879100018859

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

- Mexican migration has changed America for the better

Remittances sent home have helped Mexico, too

Your browser does not support the <audio> element.

P EDRO MORALES , a 73-year-old retired farmer, sits at the table of his sparsely furnished house in Santa Rosa and flicks through faded pictures of José, one of his sons. In 1990 José, then just 19, left this small village two hours outside of Guadalajara, in the central Mexican state of Jalisco, where chickens still roam the streets. He crossed the border to the United States illegally, and has lived there ever since.

Some 3,000km (1,800 miles) away, José explains over breakfast in Los Angeles that he migrated north for “a better life and to help my parents”. It has been hard work, but he achieved both aims. With the money he earned through a series of construction jobs, he bought a house in California. He married Claudia, also an undocumented Mexican. Their 26-year-old daughter, Evelyn, is an American citizen.

José was not the only person from his family to make the journey. His brother Roberto lived in the United States for nine years until he was deported. One of Pedro’s grandsons, named after him, worked for four years legally in America before returning to Mexico at the start of the pandemic. Juan Carlos, another grandson, migrated north last year for six months on a visa for agricultural labourers.

One family, two countries—and a tangled web of legal statuses and experiences. The Morales family illustrates the vast and varied panorama of migration from Mexico to the United States, one of the largest movements of people from one country to another in the past 50 years. Since 1965 over 16m people have left Mexico to go north of the border.

Partly because so many Mexicans (and Central Americans) have moved illegally to the United States, immigration is an issue that haunts every American administration. President Joe Biden, for example, is under pressure to extend a policy known as Title 42, introduced under his predecessor Donald Trump. This policy, ostensibly adopted because of the pandemic, allows officials to turn away migrants at the border, including asylum-seekers, and is due to expire in May. But such squabbles over Mexican migration fail to capture its nuances. And they ignore how these migrants are shaping both their countries, mostly for the better.

The border between the two countries has always been porous. But the period of mass movement north dates to 1964, when the closure of the bracero seasonal work programme in the United States spurred many Mexicans to make the journey illegally. The number of migrants gathered pace in the 1980s and rocketed in the 1990s and early 2000s (see chart).

Las fronteras

Mexican migration is primarily driven by a demand for manual labour in the United States, says Jorge Durand of the University of Guadalajara. By one estimate 68% of California’s agricultural workers are Mexicans. “I knew there was work in the United States,” says José.

The first wave of migrants fitted squarely into this pattern. They were single young men from rural areas, according to Filiz Garip of Princeton University. They did not have documents and worked in agriculture. Later, however, they were joined by migrants from cities, who were richer and better educated than the average Mexican. Women started to make the journey. Migrants fanned out from California, Texas and Illinois to other parts of America. They stayed for longer, too.

The patterns of Mexican migration shifted again over the time that José was beginning to settle down in the United States. For a start, after a peak in 2007, fewer Mexicans have been making it over the border each year, not least as border security has been tightened by successive administrations. In the 2000s there were several years of negative net migration, because of a large number of deportations and a less buoyant jobs market caused by the Great Recession. The second trend is that since around 2017, there have been more legal than illegal Mexicans in the United States, estimates suggest.

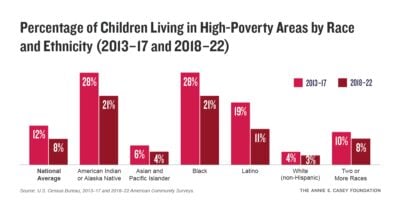

The overall fall in the number of migrants also correlates with Mexico’s shifting demography. An average Mexican woman had 6.6 children in her lifetime in 1970 but only 2.1 in 2020; the country’s median age rose from 15 to 28 over the same period. Mexican migrants, in turn, have changed the United States. The country is home to around 11m migrants born in Mexico. They constitute around a quarter of the foreign-born population, and are increasingly a political and an economic force. Hispanic migrants are younger and, until recently, tended to have more children. According to the Pew Research Centre, some 17% of American women who gave birth in 2018 were of Hispanic origin, up from 10% in 2000. But Mexican migrants to the United States are having far fewer children than they used to: in 2000 they accounted for 42% of all births to women born abroad. By 2018 their share was half that.

Hope accompanies them

The newcomers changed where they lived, too. Almost half of the population of Los Angeles is Hispanic. Most are of Mexican heritage. In the neighbourhood where the Morales live, there are “lavanderias” (laundries), “tiendas” (shops) and “taquerias” (taco shops), not unlike back in Mexico. Claudia says when Evelyn was small she would panic about not being able to speak English in a medical emergency. Now Spanish-speaking doctors are plentiful. Mexican-Americans are creating new traditions, too. “On the one hand I have a sense of lost identity, but on the other we are creating our own culture,” says Evelyn.

The presence of Mexican labourers willing to work for less pay than Americans can push down wages. Research by economists such as Gordon Hanson of Harvard University and Giovanni Peri of the University of California suggests this affects only a small proportion of Americans. Mexican migrants boost the purchasing power of far more people by providing cheap childcare and the like. “Anyone who has bought a house or eats fruit and vegetables” has benefited, says Mr Hanson. However, other economists, such as George Borjas at Harvard University, think the number of poorly paid American workers affected may be higher.

Either way, most economists agree that immigration is good for the receiving economy over the long run. A model built by Mr Hanson and colleagues found that reducing immigration from Latin America by half led to a small decline in average real income. The decline was larger in places with many Hispanic immigrants, such as Los Angeles.

Moving north also improves the lives of Mexican migrants. Mr Hanson calculates that the income of those who move goes up between two-and-a-half and five times, even after adjusting for the higher cost of living in America. Pepe Zárate, a 41-year-old undocumented Mexican, could have earned a decent living at home as a doctor but still left for the United States two decades ago. He now makes around $4,000 a month as a construction worker. In Mexico he would struggle to earn an equivalent wage even as a doctor.

Evaluating migration’s impact the other way, on Mexico’s economy, is trickier. Economists reckon remittances have helped keep the economy relatively stable. They boost spending and are a big source of foreign exchange. Pedro’s house in Santa Rosa is modest compared to his son’s in Los Angeles, but far more luxurious than others in the area. With the money José sent him, he installed a toilet which flushes, for instance.

During the pandemic remittances have been particularly important. They rose by 27% between 2020 and 2021, reaching a high of $52bn, equivalent to 4% of Mexico’s GDP . In contrast, the government under Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the fiscally conservative president, has spent only 0.7% of GDP on direct aid.

But Mexico has failed to make the most of its migrants, says Tonatiuh Guillén, a former head of Mexico’s National Institute for Migration. Those with fluent English could work in call centres, so boosting the country’s nascent service industry. Migrants could also be tapped for investment. Mr López Obrador ended a programme in which municipal, state and federal governments could match gifts or contributions from hometown clubs of migrants in the United States to pay for roads and the like.

Today is all they have

Lately the number of Mexicans making the journey north has been climbing again. Last year US border patrol agents caught 655,594 Mexicans trying to enter America illegally. Numbers this year are already up by 44%. That includes some double-counting, but it still seems likely that the number of people crossing is rising sharply.

Mexico’s economy is 3.8% smaller than in 2019, and is not expected to reach its former size again until next year. Gang violence has not previously spurred migration, but that appears to be changing, too, reckons Stephanie Leutert of the University of Texas at Austin.

The political backlash to this will make the lives of those Mexicans who are already settled in the United States harder. According to Doug Massey at Princeton University, most studies suggest that Mexican migrants are becoming more like Americans, both financially and socially. But as so many are undocumented, they do not have access to services that could help them integrate further. Many live in fear of being booted out; few dare leave as a result. American immigration policy “has never really recognised that historically Mexicans didn’t want to settle [in the United States],” argues Mr Massey, but to “circulate and keep their home in Mexico”.

José, for example, has only visited his father once in the two decades since moving away. He and Claudia would return to Mexico permanently if they knew they could go back to see Evelyn in the United States. “This country has given us so many opportunities,” he says. “But I would like to be able to hug my brother on his birthday or share a family meal.” ■

This article appeared in the The Americas section of the print edition under the headline “The United States of Mexico”

The Americas April 23rd 2022

- Can Venezuela help the West wean itself off Russian oil?

From the April 23rd 2022 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

More from The Americas

Javier Milei finally lugs key reforms through Argentina’s Senate

Markets celebrated the two bills’ passing, after protesters took to the streets of Buenos Aires

Latin America is the world’s trade pipsqueak

The world’s longest mountain range and largest tropical rainforest make commerce a challenge

Colombia’s leftist president is flailing

His attempts at reform are increasingly infuriating Colombians

A battle royal over deep-sea archaeology in the Caribbean

Colombia begins to explore one of the world’s most contested shipwrecks

Claudia Sheinbaum’s landslide victory is a danger for Mexico

She has huge power, but faces huge challenges

As seas rise, the relocation of Caribbean islanders has begun

The government-managed movement of 300 families from the island of Gardi Sugdub is a test case for “planned retreat” in Latin America

I study migrants traveling through Mexico to the US, and saw how they follow news of dangers – but are not deterred

Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University

Disclosure statement

Angel Alfonso Escamilla García does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

The world awoke one morning in late March 2023 to the news that at least 38 Central and South American migrants had died in a fire in a migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

A widely circulated video from the closed-circuit cameras inside the detention center showed the building burning, with migrants trapped inside trying to break the metal bars of their cells – and detention center officers allegedly leaving them there.

The Mexican government has said the migrants themselves started the fire after learning they would be deported from Mexico – which is increasingly a destination for migrants and asylum seekers – back to their home countries.

The video spread quickly across social media, and many Mexican migrant advocacy groups and activists decried the event.

Another group also paid close attention to this tragedy – migrants who are in transit through Mexico.

As a sociologist , I have studied the impacts of violence against Central American migrants in Mexico for nearly a decade. I have considered questions like how migrants who are on their way to the U.S. react to news of violence against other migrants, and whether such news alters their plans.

My research has shown that migrants pay close attention to any information that can give them clues about the dangers that lie between them and the U.S.

Migrants have shared with me that they highly value information about any dangers ahead as they move north, whether it relates to criminal groups or U.S. immigration policy changes. Migrants use this knowledge to implement a variety of strategies to avoid, or at least prepare for, any suffering – and it can lead them to take different routes to the U.S. border.

Understanding migrants in Mexico

Hundreds of thousands of migrants from around the world transit through Mexico every year on their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. In April 2023 alone, the U.S. detained more than 211,000 migrants along that border. That statistic coincides with an overall rise in global migration and rise in migrants trying to reach the U.S.

The majority of migrants crossing the U.S. border come from Latin American countries other than Mexico , including Central American countries, but also Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and Cuba.

Most of these migrants are single adults , though a number of them are also families and children. People migrate through Mexico for many reasons, including political instability, lack of work opportunities and violence in their own countries.

My interviews with migrants moving through Mexico show that they tend to widely circulate tragic news, such as news of the June 2022 news of migrants found dead locked in a tractor trailer in San Antonio. Videos and photos of this and other tragic instances, like the Ciudad Juárez fire, provide real, vivid images of what can happen if migrants decide to pursue the same pathway.

And for these migrants, the images and news stories aren’t secondhand information that they can question or doubt – images can be interpreted as unchangeable truths.

How migrants get their news

Migrants don’t receive news from New York Times alerts or nightly news.

Their information-sharing largely occurs in an underground informal information exchange that circulates news and stories among migrants heading toward the U.S. through Mexico.

That information is shared, discussed, interpreted and commented on through social media platforms, chat groups and word of mouth. Within 24 hours of the Ciudad Juárez fire, every single social media outlet and migrant chat that I follow as part of my research, comprised of thousands of transit migrants moving throughout Mexico and Guatemala in real time, had posted and reposted the video and news of the incident.

Some comments and replies in social media and chat groups about the incident prayed for mercy and peace for the dead and their loved ones.

Others asked for a list of names of the dead, or about their places of origin, as people desperately sought to find out whether their family members and friends were among the dead and injured. Still others asked for tips and discussed ways to avoid suffering the same fate, such as asking about alternate routes to the border, or sharing ways to avoid ending up in Mexican migrant detention centers.

A shared response

Common among migrants’ reactions to the March 2023 fire was a deep sense of grief. Migrants recognized how close they are to those who lost their lives and expressed a sense of “that could have been me.”

And yet, in my field work, I have found that these horrific events do not deter migrants’ desire to reach the U.S. What they do is reset migrants’ expectations going forward.

Through my field work, I have heard migrants repeatedly tell stories about the dire conditions in detention centers in Mexico .

They report that these poor conditions – rotten food, fleas, lack of clothing or blankets for the cold weather – have triggered hunger strikes and protests.

Broader effects

Another of my main findings is that violent and tragic incidents tend to prompt migrants to avoid any interactions with police or any other officials, even under the guise of help or support.

For example, my research suggests that stories and images of violence like the Ciudad Juárez tragedy will generate a further lack of trust in the Mexican government. I believe that the incident will create certain expectations about the perils of spending time near the border. If they can, I think that migrants will likely avoid Ciudad Juárez and other areas where they feel they may be detained.

I believe the fire will also leave a symbolic scar on migrants in Mexico, who will collectively remember this event and construct their journeys around it.

- Social media

- Immigration

- Human rights

- Latin America

- Human rights violations

Senior Research Fellow - Curtin Institute for Energy Transition (CIET)

Research Grants Officer

Laboratory Head - RNA Biology

Head of School, School of Arts & Social Sciences, Monash University Malaysia

Chief Operating Officer (COO)

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Consequences of Migration to the United States for Short-term Changes in the Health of Mexican Immigrants

Noreen goldman.

Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Wallace Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA

Anne R. Pebley

California Center for Population Research, University of California Los Angeles, CA. 90095, USA

Mathew J. Creighton

Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Departament de Ciències Polítiques i Socials, Barcelona, Spain

Graciela M. Teruel

Universidad Iberoamericana, AC and CAMBS, México D.F., México

Luis N. Rubalcava

Centro de Análisis y Medición del Bienestar Social, AC and CIDE, México D.F., México

Chang Chung

Although many studies have attempted to examine the consequences of Mexico-U.S. migration for Mexican immigrants’ health, few have had adequate data to generate the appropriate comparisons. In this article, we use data from two waves of the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) to compare the health of current migrants from Mexico with those of earlier migrants and nonmigrants. Because the longitudinal data permit us to examine short-term changes in health status subsequent to the baseline survey for current migrants and for Mexican residents, as well as to control for the potential health selectivity of migrants, the results provide a clearer picture of the consequences of immigration for Mexican migrant health than have previous studies. Our findings demonstrate that current migrants are more likely to experience recent changes in health status—both improvements and declines—than either earlier migrants or nonmigrants. The net effect, however, is a decline in health for current migrants: compared with never migrants, the health of current migrants is much more likely to have declined in the year or two since migration and not significantly more likely to have improved. Thus, it appears that the migration process itself and/or the experiences of the immediate post-migration period detrimentally affect Mexican immigrants’ health.

Introduction

Large-scale Mexican-U.S. migration has changed social, economic, and cultural life on both sides of the border. Migration to the United States can offer increased earnings and savings accumulation ( Gathmann 2008 ). However, it can also be a difficult experience for migrants because of the risks and costs of border crossing; poorly paying, irregular, and hazardous jobs; crowded housing; lengthy family separation; discrimination; and a politically hostile climate ( Hovey 2000 ; Massey and Sanchez 2010 ; Ullmann et al. 2011 ).

What are the consequences of the immigrant experience for immigrants’ health? The literature suggests that Mexican immigrants are positively selected for good health and healthy behaviors (the “healthy migrant effect”) but that living in the United States may lead to deterioration in both health and healthy behaviors of migrants ( Ceballos and Palloni 2010 ; Kaestner et al. 2009 ; Oza-Frank et al. 2011 ; Riosmena and Dennis 2012 ). However, the evidence for both parts of this scenario is often contradictory and limited by available data. A study based on Mexican longitudinal data found only weak evidence of positive health selection for migrants ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ). However, studies using binational cross-sectional data to compare Mexican immigrants in the United States with Mexican residents have argued more strongly in support of positive health selection ( Barquera et al. 2008 ; Crimmins et al. 2005 ).

Research on the effects of life in the United States on immigrant health is also problematic. Studies comparing immigrant duration cohorts cross-sectionally in the United States have generally suggested that immigrant health and health behaviors deteriorate with longer durations of residence ( Abraído-Lanza et al. 2005 ; Lara et al. 2005 ). In contrast, some studies indicate that health trajectories are not monotonically related to time spent in the United States ( Jasso et al. 2004 ; Teitler et al. 2012 ).

Many of the limitations characterizing previous research on immigrant health result from reliance on cross-sectional data. These studies did not have adequate information on premigration health, making it impossible to determine when health deterioration began. In addition, cross-sectional comparisons involve cohorts of immigrants with different characteristics that arrived in different time periods with distinct political and economic climates; comparisons are further biased by selective attrition of return migrants, who, on average, are less healthy than the stayers (i.e., the “salmon bias”; Riosmena et al. 2013 ). Moreover, cross-sectional studies cannot assess whether the observed health trajectories of immigrants differ from those of nonmigrants. Alternative strategies that compare U.S. emigrants who have returned to Mexico with those who remained in their home communities are also problematic because of potential health-selective return migration.

In this article, we use data from the two waves of the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) to explicitly examine short-term changes in health status for current migrants in the United States compared with return migrants and never migrants. Because the richness of data in the MxFLS permits extensive controls for the potential health selectivity of migrants, this article provides a significantly clearer picture of the consequences of immigration for Mexican migrant health than previous studies.

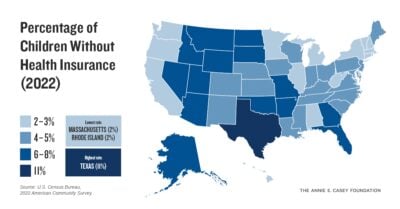

The literature suggests several reasons why immigrant health may deteriorate in the United States. The first is inadequate access to health care, particularly for undocumented migrants ( Nandi et al. 2008 ; Prentice et al. 2005 ; Vargas Bustamante et al. 2012 ). Having health insurance is a key predictor of access to health care, particularly for immigrants ( Siddiqi et al. 2009 ).

A second explanation is the detrimental effects of acculturation on health behaviors (i.e., poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, and substance abuse) through exposure to U.S. society. In recent years, the acculturation literature has been strongly criticized ( Carter-Pokras et al. 2008 ; Creighton et al. 2012 ; Hunt et al. 2004 ; Viruell-Fuentes 2007 ; Zambrana and Carter-Pokras 2010 ) for failing to take socioeconomic status seriously and for its limited theoretical grounding in the immigrant integration literature. A more nuanced interpretation of the acculturation hypothesis, drawn from the literature on segmented assimilation, suggests that Mexican immigrants may adopt the less healthy behaviors of lower-income Americans because many involuntarily join this social class upon entering the United States ( Abraído-Lanza et al. 2006 ).

Other hypotheses focus on social inequality as causes of declines in migrant health ( Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2012 ). For example, the acculturative stress hypothesis suggests that because U.S. society views Mexican-origin immigrants as low status, immigrants face discrimination and chronic stress ( Finch and Vega 2003 ). In addition, Mexican immigrants may live and work under unhealthy conditions that expose them to infectious disease, environmental toxins, injury, and other health risks ( Acevedo-Garcia 2001 ; Kandel and Donato 2009 ; Orrenius and Zavodny 2009 ).

A related stressor is the increasingly hostile political climate for recent immigrants in the United States, including stronger border enforcement, restriction of access to welfare and Medicaid, and state anti-immigrant efforts ( Cornelius 2001 ; Massey and Sanchez 2010 ). Discrimination, family cultural conflict and lengthy separation, a hostile political climate, loss of social support, and, after the 2008 economic crisis, fewer jobs are all likely to be stressful experiences, especially for undocumented immigrants, and are likely to have a more immediate impact on immigrants’ mental and physical health than poor access to health care or acculturation mechanisms.

Despite these findings, it is possible that emigration to the United States improves Mexican migrants’ health. Residence in the United States has a consistently positive effect on the wealth of middle-aged and older Mexican return migrants ( Wong et al. 2007 ), and income and wealth are strongly associated with better health ( Marmot and Bell 2012 ). Mexican migrants, particularly documented ones, may also experience better working and housing conditions than they would have in Mexico. Previous studies have found that health care use and self-perceptions of health may improve with duration in the United States ( Hummer et al. 2004 ; Lara et al. 2005 ) and that some health outcomes are better for immigrants who have resided in the United States for several years ( Riosmena et al. 2013 ; Teitler et al. 2012 ).

In this article, we examine whether the health of Mexican immigrants deteriorates or improves after migration to the United States. We explicitly compare changes in health status of recent immigrants with those of previous immigrants and with individuals who remained in Mexico. Because these three groups are likely to differ in initial health status (e.g., because of the healthy migrant effect and salmon bias), a critical part of this analysis is the introduction of extensive controls for baseline health status.

The Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) has several advantages for this analysis: it interviews respondents at closely spaced waves that permit assessment of short-term changes in health for migrants to the United States and individuals who remain in or return to Mexico; it collects objective and subjective health assessments that provide controls for potential health selectivity of migrants; and it obtains detailed migration histories that allow us to distinguish among recent, earlier, and never migrants. The baseline survey in 2002 (MxFLS-1) interviewed all adult members residing in more than 8,440 households in 147 localities of Mexico ( Rubalcava and Teruel 2006 ). Respondents in the baseline survey were reinterviewed in 2005–2006 (MxFLS-2) and 2009–2012 (MxFLS-3). MxFLS followed individuals who left their household of origin, irrespective of destination, including movers to the United States: of those sampled in MxFLS-1, more than 90% were located and interviewed again in MxFLS-2 ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ). This analysis is based on MxFLS-1 and MxFLS-2; MxFLS-3 is not yet available.

The sample includes respondents who are 20 years and older at baseline. Of the 19,132 age-appropriate respondents, one could not be matched to a municipality and was excluded. An additional 4,874 respondents did not report one or both of the health outcomes at follow-up. After exclusion of these respondents, the analytic sample comprises 14,257 adults.

In exploratory analyses, we estimated a logistic model of the probability that a respondent was missing either of the two health outcomes. The results indicate that individuals with no previous migration history, those with more education, men, and individuals in their 20s were more likely to be missing outcomes than others. However, with these variables in the model, there were no significant differences by self-reported health status at baseline.

Outcome Variables: Self-reported Health and Change in Health

Despite the frequent use of self-reports of overall health to compare the well-being of various immigrant and native-born groups (e.g., Finch and Vega 2003 ), comparisons may be biased by differences in choice of reference group, degree of acculturation, and language of interview ( Bzostek et al. 2007 ). Because this analysis examines changes in reported health for a given individual, such biases are likely to be substantially reduced. We consider two outcomes—self-rated health (SRH) and perceived change in health—each with five possible responses: “much better,” “better,” “the same,” “worse,” and “much worse.” The SRH question in MxFLS-2 for both Mexican residents and immigrants in the United States, is as follows:

If you compare yourself with people of the same age and sex, would you say that your health is (…)?

With controls for SRH at baseline, an analysis of SRH at follow-up implicitly examines change in the respondent’s health between interviews.

The second outcome is a direct assessment of change, based on different questions for respondents in the United States and in Mexico. Respondents in Mexico were asked:

Comparing your health to a year ago, would you say your health now is (…)?

Respondents interviewed in the United States were instead asked:

Comparing your health to just before you came to the United States, would you say your health now is (…)?

Calculations indicate that the average time since migration to the United States for current migrants is 1.6 years—only slightly longer than the explicit period of 1 year used in the Mexico interviews.

Because few respondents reported the extreme categories of “much better” or “much worse,” the five response categories were collapsed into three: “much better” and “better” were combined into a single category, as were “much worse” and “worse;” “same” health is the reference category.

Migrant Status

We categorize respondents as “current,” “return,” and “never” migrants. Current migrants migrated after the baseline survey and were interviewed in the United States in MxFLS-2. Return migrants were interviewed in Mexico at Wave 2 but had previous migration experience to the United States; they include long-term and temporary migrants as well as those who migrated to the United States between survey waves but returned to Mexico before the second interview. Never migrants reported no international migration experience by Wave 2.

Control Variables

To account for potential differences in the health status of migrants, return migrants, and nonmigrants at baseline that are not captured by SRH, we include four health variables in addition to SRH, all measured at Wave 1. Obesity, anemia, and hypertension are derived from assessments conducted in the home by a trained health worker. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 based on height and weight measurements ( WHO 2000 ). Individuals are classified as anemic for the following hemoglobin (Hb) levels: Hb<130 g/L for males or Hb<120 g/L for females ( WHO 2000 ). Individuals with elevated systolic (mmHg≥140) and/or diastolic (mmHg≥90) blood pressure are considered hypertensive ( WHO 2000 ). The final health measure reflects whether the respondent had been hospitalized in the past year.

Two measures of socioeconomic status provide additional controls for potential selectivity of migrants: (1) years of schooling, and (2) log per capita household expenditure. The latter measure has been used to assess household economic well-being in a broad range of contexts, including Mexico ( Contreras 2003 ; Rubalcava et al. 2009 ; Xu et al. 2009 ). All models also control for sex and age (linear and quadratic terms).

Municipal Controls

Because the literature suggests that migration decisions depend on place of origin ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ) and migration flows at the municipality level are likely to be related to unobserved characteristics (e.g., human capital) of residents, we include three variables at the municipality level. A municipality was coded as rural if there were fewer than 2,500 residents ( INEGI 2003 ). We also include two measures based on the 2000 Mexican Census: (1) a marginalization index derived from a factor analysis of municipal-level measures of education, housing, income, and schooling ( Luis-Ávila et al. 2001 ); and (2) a measure of migration intensity based on the number of return migrants, current migrants, and amount of remittances received by households ( Tuirán et al. 2002 ). Both measures are categorized as “low,” “medium,” and “high.”

As described earlier, we classify both health outcome variables (self-rated health at Wave 2 relative to someone of the same age and sex and perceived health change over the year prior to Wave 2) as better, same, or worse health. For each of the two health outcomes, we fit multinomial regression models, with “same” health as the reference category, to estimate relative risk ratios (RRRs) for worse relative to same health and RRRs for better relative to same health. We estimate a set of three models that sequentially includes (1) migrant status, baseline SRH, age and sex; (2) objective health measures; (3) socioeconomic status and municipal-level characteristics. The estimate of primary interest pertains to current migrants: that is, is health at follow-up or perceived change in health of current migrants better, worse, or the same as that of never or return migrants?

We use multiple imputation to estimate a response for explanatory variables with missing values (see Table 1 for the frequency of missing data). We create five imputed data sets. The imputation models include all covariates with complete information as well as a variable denoting household size (to improve overall model fit). The estimated RRRs in the results section are derived from average values of the coefficients across the five imputed data sets.

Description of the outcome and explanatory variables in the analytic sample

| Variable | Count | % | Mean | SD | % Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | |||||

| Self-rated health status relative to same age and sex (MxFLS-2) | 0.0 | ||||

| Worse | 1,183 | 8.3 | –– | –– | |

| Same | 8,676 | 60.9 | –– | –– | |

| Better | 4,398 | 30.9 | –– | –– | |

| Perceived change in health status (MxFLS-2) | 0.0 | ||||

| Worse | 1,735 | 12.2 | –– | –– | |

| Same | 9,385 | 65.8 | –– | –– | |

| Better | 3,137 | 22.0 | –– | –– | |

| Explanatory | |||||

| Migrant status (MxFLS-2) | 0.0 | ||||

| Never | 13,560 | 95.1 | –– | –– | |

| Return | 391 | 2.7 | –– | –– | |

| Current | 306 | 2.2 | –– | –– | |

| Self-rated health status relative to same age and sex (MxFLS-1) | 10.5 | ||||

| Worse | 1,008 | 7.9 | –– | –– | |

| Same | 7,461 | 58.4 | –– | –– | |

| Better | 4,298 | 33.7 | –– | –– | |

| Male | –– | –– | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.0 |

| Age (years) | –– | –– | 42.22 | 15.74 | 0.0 |

| Obese | –– | –– | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.0 |

| Anemic | –– | –– | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.0 |

| Hypertensive | –– | –– | 0.34 | 0.47 | 8.3 |

| Hospitalized in previous year | –– | –– | 0.06 | 0.23 | 10.5 |

| Marginalization Index | 0.0 | ||||

| Low | 9,520 | 66.8 | –– | –– | |

| Medium | 2,729 | 19.1 | –– | –– | |

| High | 2,008 | 14.1 | –– | –– | |

| Migration intensity index | 0.0 | ||||

| Low | 11,021 | 77.3 | –– | –– | |

| Medium | 1,376 | 9.7 | –– | –– | |

| High | 1,860 | 13.1 | –– | –– | |

| Rural | –– | –– | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.0 |

| Years of education | –– | –– | 6.31 | 4.40 | 1.2 |

| Log per capita expenditure | –– | –– | 6.88 | 1.08 | 3.5 |

| 14,257 |

The sample is clustered at two levels: 14,257 adults are drawn from 7,200 households and 136 municipalities. To account for the dependence of observations, we use robust standard errors clustered at the household level to calculate variances under multiple imputation. The estimates are computed in Stata 12 using the mlogit command ( StataCorp 2011 ).

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 . At each wave, about 60 % of respondents evaluate their overall health the same as someone of the same age and sex, and only about 8 % rate their health as worse. Almost twice as many respondents note an improvement as compared with a deterioration in health over the period. About 5 % of the respondents are current or return migrants.

The relative risk ratios (RRRs, or exponentiated coefficients) in Table 2 pertain to self-rated health at follow-up. Based on Model 3, the estimated RRR for current migrants is 1.7 ( p < .05) for worse compared with the same health and 1.3 ( p < .05) for better compared with the same health (relative to a never migrant). In other words, current migrants in the United States are less likely than never migrants to rate themselves as having the same health status as someone of their age and sex: they are more apt to rate their health both worse and better—but especially worse than their peers—at the second interview. The estimates for return migrants are not significantly different from those for never migrants. Estimates for the control variables generally conform to expectation.

Relative risk ratios (RRRs) and t statistics from multinomial logistic model of self-rated health status (SRH) relative to same age and sex at MxFLS-2

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | t | RRR | t | RRR | t | |

| Contrast: Worse (vs. same) | ||||||

| Migrant status (ref. = never) | ||||||

| Return | 0.861 | −0.72 | 0.851 | −0.78 | 0.858 | −0.73 |

| Current | 1.731 | 2.56 | 1.789 | 2.70 | 1.707 | 2.49 |

| Male | 0.688 | −5.76 | 0.732 | −4.70 | 0.760 | −4.08 |

| Age (years) | 1.604 | 11.00 | 1.621 | 10.79 | 1.402 | 6.70 |

| Age Squared SRH at MxFLS-1 (ref. = same) | 0.954 | −1.81 | 0.956 | −1.71 | 0.977 | −0.87 |

| Worse | 3.377 | 13.06 | 3.311 | 12.72 | 3.122 | 11.96 |

| Better | 0.944 | −0.62 | 0.944 | −0.62 | 0.984 | −0.17 |

| Obese | 1.245 | 3.22 | 1.264 | 3.42 | ||

| Anemic | 1.140 | 1.10 | 1.111 | 0.87 | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.890 | −1.64 | 0.887 | −1.70 | ||

| Hospitalized in previous year | 1.658 | 4.05 | 1.668 | 4.08 | ||

| Marginalization index (ref. = low) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.240 | 2.30 | ||||

| High | 1.006 | 0.06 | ||||

| Migration intensity index (ref. = low) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.216 | 1.72 | ||||

| High | 0.998 | −0.02 | ||||

| Rural | 0.903 | –1.31 | ||||

| Years of education | 0.939 | −5.71 | ||||

| Log per capita expenditure | 1.060 | 1.86 | ||||

| Contrast: Better (vs. same) | ||||||

| Migrant status (ref. = never) | ||||||

| Return | 0.937 | −0.57 | 0.934 | −0.60 | 0.940 | −0.53 |

| Current | 1.129 | 0.93 | 1.122 | 0.88 | 1.303 | 1.99 |

| Male | 1.033 | 0.91 | 1.033 | 0.88 | 1.001 | 0.03 |

| Age (years) | 0.994 | –0.26 | 1.004 | 0.17 | 1.091 | 3.32 |

| Age squared SRH at MxFLS-1 (ref. = same) | 0.979 | −1.21 | 0.977 | −1.33 | 0.977 | −1.31 |

| Worse | 0.938 | −0.76 | 0.937 | −0.78 | 0.970 | −0.36 |

| Better | 1.652 | 12.05 | 1.653 | 12.07 | 1.541 | 10.21 |

| Obese | 0.965 | −0.85 | 0.944 | −1.36 | ||

| Anemic | 0.880 | −1.52 | 0.920 | −0.98 | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.960 | −0.95 | 0.943 | −1.33 | ||

| Hospitalized in previous year | 1.137 | 1.46 | 1.053 | 0.58 | ||

| Marginalization index (ref. = low) | ||||||

| Medium | 0.925 | −1.23 | ||||

| High | 0.666 | −5.32 | ||||

| Migration intensity index (ref. = low) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.012 | 0.15 | ||||

| High | 0.722 | −4.26 | ||||

| Rural | 1.004 | 0.08 | ||||

| Years of education | 1.034 | 5.97 | ||||

| Log per capita expenditure | 1.093 | 4.44 | ||||

| 14,257 | ||||||

Notes: Based on five multiple imputations of missing values. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the household level.

Because RRRs are difficult to interpret, in upcoming Table 4 , we present predicted probabilities of worse, same, or better health at follow-up by migrant status. Each estimate was determined by setting all explanatory variables except migrant status at their observed values for each individual, setting migrant status to the same value for all individuals (never, return, or current migrant) and calculating the mean prediction from the model. The first panel, which shows predictions based on Model 3 in Table 2 , underscores the results noted earlier: at follow-up, current migrants are considerably more likely (by nearly 50 %) than never migrants to rate their health as worse than someone of the same age and sex and only slightly more likely (by about 13 %) to rate their health as better.

Average predicted probabilities of self-rated health status at Wave 2 a and perceived change in health status b by migrant status

| Outcome | Migrant Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Return | Current | |

| Self-rated Health Status (MxFLS-2) | |||

| Worse | .0826 | .0735 | .1199 |

| Same | .6096 | .6281 | .5316 |

| Better | .3078 | .2983 | .3485 |

| Total | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Perceived Change in Health Status | |||

| Worse | .1208 | .1072 | .1939 |

| Same | .6596 | .6668 | .5764 |

| Better | .2195 | .2259 | .2297 |

| Total | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

Notes: Predicted probabilities were determined by setting all explanatory variables except migrant status at their observed values for each individual, setting migrant status to the same value for all individuals (never, return, current migrants), and calculating the mean prediction from the model.

The RRRs in Table 3 are based on respondents’ assessments of the change in their health status. Consistent with the previous estimates, the RRRs for deteriorating health are large and significant for current migrants (1.9 in Model 3). In contrast, the RRRs for improving health are not significantly different from one for current migrants. As with SRH, the RRRs for return migrants are not significantly different from one for either deteriorating or improving health. The predicted probabilities in the second panel of Table 4 indicate that the health of current migrants is about 60 % more likely than that of never migrants to have worsened in the recent past and only very slightly (and insignificantly) more likely to have improved.

Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs) and t-statistics from Multinomial Model of Perceived Change in Health Status Relative to Previous Year or Prior to Migration

| Models | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| RRR | t | RRR | t | RRR | t | |

| Contrast: ( ) | ||||||

| Migrant Status (ref=Never) | ||||||

| Return | 0.961 | -0.25 | 0.955 | -0.29 | 0.870 | -0.85 |

| Current | 2.202 | 4.28 | 2.227 | 4.33 | 1.909 | 3.46 |

| Male | 0.631 | -8.59 | 0.649 | -7.93 | 0.673 | -7.16 |

| Age (Years) | 1.774 | 15.89 | 1.787 | 15.54 | 1.609 | 11.73 |

| Age Squared | 0.927 | -3.43 | 0.928 | -3.38 | 0.937 | -2.92 |

| SRH at MxFLS-1 (ref=Same) | ||||||

| Worse | 2.416 | 10.34 | 2.393 | 10.15 | 2.241 | 9.22 |

| Better | 1.126 | 1.89 | 1.127 | 1.90 | 1.188 | 2.72 |

| Obese | 1.098 | 1.60 | 1.130 | 2.09 | ||

| Anemic | 1.049 | 0.44 | 1.060 | 0.52 | ||

| Hypertensive | 0.929 | -1.18 | 0.937 | -1.04 | ||

| Hospitalized in Previous Year | 1.293 | 2.22 | 1.296 | 2.22 | ||

| Marginalization Index (ref=Low) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.055 | 0.69 | ||||

| High | 0.975 | -0.27 | ||||

| Migration Intensity Index (ref=Low) | ||||||

| Medium | 1.402 | 3.63 | ||||

| High | 1.535 | 5.10 | ||||

| Rural | 0.895 | -1.65 | ||||

| Years of Education | 0.958 | -5.14 | ||||

| Log Per Capita Expenditure | 1.034 | 1.25 | ||||

| Contrast: ( ) | ||||||

| Migrant Status (ref=Never) | ||||||

| Return | 0.972 | -0.22 | 0.970 | -0.24 | 1.020 | 0.15 |

| Current | 1.048 | 0.31 | 1.055 | 0.36 | 1.192 | 1.16 |

| Male | 0.855 | -3.85 | 0.862 | -3.49 | 0.856 | -3.63 |

| Age (Years) | 0.834 | -7.56 | 0.830 | -7.52 | 0.830 | -6.59 |

| Age Squared | 1.038 | 1.90 | 1.038 | 1.86 | 1.042 | 2.06 |

| SRH at MxFLS-1 (ref=Same) | ||||||

| Worse | 1.153 | 1.58 | 1.136 | 1.41 | 1.144 | 1.48 |

| Better | 1.285 | 5.49 | 1.286 | 5.51 | 1.243 | 4.73 |

| Obese | 1.016 | 0.35 | 1.001 | 0.02 | ||

| Anemic | 1.000 | 0.00 | 1.016 | 0.17 | ||

| Hypertensive | 1.057 | 1.12 | 1.041 | 0.81 | ||

| Hospitalized in Previous Year | 1.362 | 3.44 | 1.309 | 2.97 | ||

| Marginalization Index (ref=Low) | ||||||

| Medium | 0.836 | -2.62 | ||||

| High | 0.776 | -3.27 | ||||

| Migration Intensity Index (ref=Low) | ||||||

| Medium | 0.832 | -2.20 | ||||

| High | 0.734 | -3.78 | ||||

| Rural | 1.043 | 0.77 | ||||

| Years of Education | 0.996 | -0.60 | ||||

| Log Per Capita Expenditure | 1.056 | 2.43 | ||||

| N | 14257 | |||||

Note: Based on five multiple imputations of missing values. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the household level.

The central question of this analysis has been whether migrants from Mexico to the United States experience changes in their health after they move. This simple question has not been adequately answered by prior research because of the dearth of appropriate data. However, through data collection efforts in Mexico and the United States at the second wave, and extensive baseline information on variables potentially related to the health selectivity of migrants, the MxFLS permits us to address this issue in a methodologically appropriate way.

Two outcome variables—SRH at the second wave and self-assessment of recent change in health status—provide insights into the changing health status of current migrants relative to others. Both measures indicate that current migrants are more likely to have experienced recent changes in health status—both improvements and declines—than either earlier migrants or nonmigrants. This is perhaps not surprising because migration to the United States is associated with changes in many of the determinants of health status, including access to health care, exposure to stressful experiences and health risks, and lifestyle. Moreover, the fact that some migrants report better health while others report worse health is consistent with the notion of multiple acculturative processes that ultimately lead to distinct mental and physical health outcomes ( Castro 2013 ).

An important question concerns the net change in health status: compared with residents in Mexico, was improvement in health as prevalent as deterioration in health among current migrants? Because migrants may use a different reference group to evaluate their health status in the United States than they used three years earlier in Mexico ( Bzostek et al. 2007 ), respondents’ direct assessments of changes in their recent health status may be more informative. Our results demonstrate that the net change across the sample of current migrants is a decline in their overall health relative to the other groups.

Although this finding is consistent with the large literature on deteriorating migrant health with length of residence in the United States, our study is the first (to our knowledge) to demonstrate that declines in self-assessed health appear quickly after migrants’ arrival in the United States. Most previous studies suggest that recent Mexican immigrants in the United States are in better health compared with longer-term migrants and the U.S.-born population. However, comparisons based only on U.S. residents miss an important part of the picture: they ignore changes in individual immigrant health in the year or so after migration (compared with migrants’ own health before migration and that of nonmigrants). Our results suggest that the migration process itself and/or the experiences of the immediate post-migration period detrimentally affect Mexican immigrants’ health.

The speed with which declines occur suggests that the process of acculturation, which tends to unfold over numerous years ( Antecol and Bedard 2006 ; Creighton et al. 2012 ), is unlikely to account for most of the decline in migrant health status. Instead, we speculate that the process of border crossing for undocumented immigrants—now more costly and dangerous than in the past ( Gathmann 2008 ; US GAO 2006 ) —combined with the physical and psychological costs of finding work and lodging in the United States, lack of health care, and the stress of undocumented status can cause rapid deterioration in immigrants’ physical and mental well-being and hence perceptions of their own health. Regardless of documentation status, many immigrants face extreme poverty, isolation from families, and harsh work conditions after arrival that may affect their health assessment.

Unfortunately, given the limited set of health questions asked of migrants at the second wave, we cannot provide a more nuanced analysis of how physical and mental well-being change. Moreover, the sample size of individuals who migrated between MxFLS-1 and MxFLS-2 is not sufficiently large to consider how working and housing conditions, diet, social interactions, lack of access to health care, financial stress, and other factors moderate the relationship between migration and health.

With the availability of the third wave of MxFLS, collected in 2009–2012, many such questions can be addressed in the future. Objective markers of health status collected in the third wave for migrants and nonmigrants alike will yield a more precise description of the ways in which health status has evolved. In addition, the inclusion of migrants between the second and third waves will not only yield a larger sample of migrants but will also permit an analysis of whether migrants who came to the United States during the past few years—a period with an especially hostile political climate and an economic recession—experienced even worse health outcomes than the migrants analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this project from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD051764, R24HD047879, R03HD040906, and R01HD047522) and from CONACYT-SEDESOL (2004-01). We would like to thank Germán Rodríguez for statistical advice and Erika Arenas for assistance in data collection and preparation of the data set for this analysis.

Contributor Information

Noreen Goldman, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Wallace Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA.

Anne R. Pebley, California Center for Population Research, University of California Los Angeles, CA. 90095, USA.

Mathew J. Creighton, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Departament de Ciències Polítiques i Socials, Barcelona, Spain.

Graciela M. Teruel, Universidad Iberoamericana, AC and CAMBS, México D.F., México.

Luis N. Rubalcava, Centro de Análisis y Medición del Bienestar Social, AC and CIDE, México D.F., México.

Chang Chung, Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Wallace Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA.

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Flórez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006; 96 :1342–1346. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Flórez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science & Medicine. 2005; 61 :1243–1255. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Acevedo-Garcia D. Zip code–level risk factors for tuberculosis: Neighborhood environment and residential segregation in New Jersey, 1985–1992. American Journal of Public Health. 2001; 91 :734–741. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: Why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography. 2006; 43 :337–360. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barquera S, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Luke A, Cao G, Cooper RS. Hypertension in Mexico and among Mexican Americans: Prevalence and treatment patterns. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2008; 22 :617–626. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bzostek S, Goldman N, Pebley A. Why do Hispanics in the USA report poor health? Social Science & Medicine. 2007; 65 :990–1003. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carter-Pokras O, Zambrana RE, Yankelvich G, Estrada M, Castillo-Salgado C, Ortega AN. Health status of Mexican-origin persons: Do proxy measures of acculturation advance our understanding of health disparities? Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2008; 10 :475–488. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Castro FG. Emerging Hispanic health paradoxes. American Journal of Public Health. 2013; 103 :1541–1541. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ceballos M, Palloni A. Maternal and infant health of Mexican immigrants in the USA: The effects of acculturation, duration, and selective return migration. Ethnicity & Health. 2010; 15 :377–396. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Contreras D. Poverty and inequality in a rapid growth economy: Chile 1990–96. Journal of Development Studies. 2003; 39 :181–200. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cornelius WA. Death at the border: Efficacy and unintended consequences of US Immigration Control Policy. Population and Development Review. 2001; 27 :661–685. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creighton MJ, Goldman N, Pebley AR, Chung CY. Durational and generational differences in Mexican immigrant obesity: Is acculturation the explanation? Social Science & Medicine. 2012; 75 :300–310. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crimmins E, Soldo BJ, Kim JK, Alley DE. Using anthropometric indicators for Mexicans in the United States and Mexico to understand the selection of migrants and the “Hispanic paradox” Social Biology. 2005; 52 :164–177. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Finch BK, Vega W. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003; 5 :109–117. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gathmann C. Effects of enforcement on illegal markets: Evidence from migrant smuggling along the southwestern border. Journal of Public Economics. 2008; 92 :1926–1941. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hovey JD. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2000; 6 :134–151. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hummer RA, Benjamins M, Rogers R. Racial and ethnic disparities in health and mortality among the US elderly population. In: Bulatao R, Anderson N, editors. Understanding racial and ethnic differences in health in late life: A research agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 53–94. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunt LM, Schneider D, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on U.S. Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine. 2004; 59 :973–986. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- INEGI. Methodological synthesis from the population censuses. Síntesis metodológica de los Censos de Población y Vivienda. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/espanol/metodologias/censos/sm_economicos.pdf .

- Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig MR, Smith JP. Immigrant health: Selectivity and acculturation. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 227–266. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaestner R, Pearson JA, Keene D, Geronimus AT. Stress, allostatic load, and health of Mexican immigrants. Social Science Quarterly. 2009; 90 :1089–1111. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kandel WA, Donato KM. Does unauthorized status reduce exposure to pesticides? Work and Occupations. 2009; 36 :367–399. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales L, Bautista D. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: A review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005; 26 :367–397. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luis-Ávila J, Fuentes C, Tuirán R. Índices de marginación, 2000 [Marginalization indexes] Del. Benito Juárez, Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO); Mexico: 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health. 2012; 126 :S4–S10. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Massey DS, Sanchez M. Broken boundaries: Creating immigrant identity in anti-immigrant times. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nandi A, Galea S, Lopez G, Nandi V, Strongarone S, Ompad DC. Access to and use of health services among undocumented Mexican immigrants in a US urban area. American Journal of Public Health. 2008; 98 :2011–2020. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orrenius P, Zavodny M. Do immigrants work in riskier jobs? Demography. 2009; 46 :535–551. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oza-Frank R, Stephenson R, Venkat Narayan KM. Diabetes prevalence by length of residence among US immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2011; 13 :1–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prentice JC, Pebley AR, Sastry N. Immigration status and health insurance coverage: Who gains? Who loses? American Journal of Public Health. 2005; 95 :109–116. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riosmena F, Dennis JA. A tale of three paradoxes: The weak socioeconomic gradients in health among Hispanic immigrants and their relation to the Hispanic health paradox and negative acculturation. In: Angel JL, Torres-Gil F, Markides K, editors. Health and health care policy challenges for aging Latinos: The Mexican-origin population. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2012. pp. 95–110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Riosmena F, Wong R, Palloni A. Migration selection, protection, and acculturation in health: A binational perspective on older adults. Demography. 2013; 50 :1039–1064. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubalcava L, Teruel G. User’s guide for the Mexican Family Life Survey First Wave. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.ennvih-mxfls.org .

- Rubalcava L, Teruel G, Thomas D. Investments, time preferences, and public transfers paid to women. Economic Development & Cultural Change. 2009; 57 :507–538. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubalcava L, Teruel G, Thomas D, Goldman N. The healthy migrant effect: New findings from the Mexican Family Life Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2008; 98 :78–84. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Siddiqi A, Zuberi D, Nguyen QC. The role of health insurance in explaining immigrant versus non-immigrant disparities in access to health care: Comparing the United States to Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2009; 69 :1452–1459. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Teitler JO, Hutto N, Reichman NE. Birthweight of children of immigrants by maternal duration of residence in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2012; 75 :459–468. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tuirán R, Fuentes C, Ávila JL. Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos, 2000. Del. Benito Juárez, Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO); Mexico: 2002. Intensity of Mexico-US migration indexes. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ullmann SH, Goldman N, Massey DS. Healthier before they migrate, less healthy when they return? The health of returned migrants in Mexico. Social Science & Medicine. 2011; 73 :421–428. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) Illegal immigration: Border-crossing deaths have doubled since 1995; Border Patrol’s efforts to prevent deaths have not been fully evaluated (Report) Washington, DC: U.S. GAO; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vargas Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, Carter-Pokras O, Wallace S, Rizzo J, Ortega A. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: The role of documentation status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2012; 14 :146–155. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007; 65 :1524–1535. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science & Medicine. 2012; 75 :2099–2106. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2000. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong R, Palloni A, Soldo BJ. Wealth in middle and old age in Mexico: The role of international migration. International Migration Review. 2007; 41 :127–151. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu K, Ravndal F, Evans DB, Carrin G. Assessing the reliability of household expenditure data: Results of the World Health Survey. Health Policy. 2009; 91 :297–305. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zambrana RE, Carter-Pokras O. The role of acculturation research in advancing science in reducing health care disparities among Latinos. American Journal of Public Health. 2010; 100 :18–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Geography AS Notes

Mexico to usa migration.

By Alex Jackson

Last updated on September 13, 2015

Hey, you're using a dangerously old browser. Although you'll be able to use this site, some things might not work or look quite right. Ideally, go and get a newer, more modern browser .

You seem to have disabled JavaScript. You should really enable it for this site but most things should work without it.

The content on this page is extremely old. Much has changed in the world since this article was written. While many of the concepts will still be relevant, figures and case studies are likely to be outdated at this point.

Migration from Mexico to the United States Of America primarily involves the movement of Mexicans from Mexico to the southern states of America which border Mexico. In order to gain access to America, Mexicans must cross the “Unites States-Mexico Border”, a border which spans four US states & six Mexican states. In America, it starts in California and ends in Texas (east to west). Due to their proximity to the border & the high availability of work in these states, the majority of Mexicans move to California followed by Texas. California currently houses 11,423,000 immigrants with Texas holding 7,951,000.

Many Mexicans from rural communities migrate to America, the majority being males who move to America and then send money back to their families in Mexico. Many of these immigrants enter the country illegally, which often requires them to cross a large desert that separates Mexico and America and the Rio Grande. These journeys are dangerous and many immigrants have died, or nearly died, trying to cross into America through these routes.

Reasons for Migration

Push factors.

There are incredibly high crime rates in Mexico, especially in the capital. Homicide rates come in at around 10-14 per 100,000 people (world average 10.9 per 100,000) and drug related crimes are a major concern. It is thought that in the past five years, 47,500 people have been killed in crimes relating to drugs. Many Mexicans will move out of fear for their lives and hope that America is a more stable place to live, with lower crime rates.

Unemployment and poverty is a major problem in Mexico and has risen exponentially in recent years. In 2000, unemployment rates in Mexico were at 2.2, however, in 2009, they rose by 34.43%, leaving them standing at 5.37 in 2010. A large portion of the Mexican population are farmers, living in rural areas where extreme temperatures and poor quality land make it difficult to actually farm. This is causing many Mexican families to struggle, with 47% of the population living under the poverty line. With these high unemployment and poverty rates, people are forced to move to America, where they have better prospects, in order to be able to support their families and maintain a reasonable standard of living.

The climate and natural hazards in Mexico could force people to move to America. Mexico is a very arid area which suffers from water shortages even in the more developed areas of Mexico. The country also suffers from natural disasters including volcanoes, earthquakes, hurricanes & tsunamis. Recent natural disasters could force people to migrate if their homes have been destroyed or made uninhabitable. People who live in danger zones could also migrate out of fear for their lives.

Pull Factors

There is a noticeable difference in the quality of life between America & Mexico. Poverty, as mentioned above, is a major issue in Mexico, with 6% of the population lacking access to “improved” drinking water. Mexico’s infrastructure is severely undeveloped when compared to America’s. Despite being the 11 th richest country in the World, Mexico also has the 10 th highest poverty. With America offering significantly better living standards and services, such as health care, people are enticed to move to America for a better life.

Existing migrant communities in states such as Texas and California help to pull people towards migration. Existing communities make it easier for people to settle once moved and family members & friends who have already moved can encourage others to move. People are also enticed to move in order to be with their families. Cousins and brothers will often move in with their relatives after they have lived in America for a while in order to be with their family.

86.1% of the Mexican population can read & write versus 99% of the population in America. In addition, the majority of students in Mexico finish school at the age of 14, versus 16 in America. These statistics show that there are significantly better academic opportunities in America than in Mexico, which can entice Mexicans to migrate for an improved education, either for themselves or, more likely, their future children, in order to give them more opportunities in the world and allow them to gain higher paying jobs.

Assimilation of Mexicans into American communities has been problematic. Many Mexicans can’t speak fluent English and studies show that their ability to speak English doesn’t improve drastically whilst they live in the US. This is largely due to them living in closed communities of other Mexican immigrants which reduces their need to assimilate with America. This can, in turn, create tension between migrants and locals which can, in extreme cases, lead to segregation, crime and violence.

There are concerns that immigrants are increasing crime rates in areas that they migrate to. Low income & poor education are factors which can lead to crime. In addition, as Mexico is a country associated with drug trafficking, there are concerns that Mexican migrants could be smuggling drugs into America, creating the problem of drug related crimes.

The introduction of Mexican cultural traditions to America, especially in states with large numbers of migrants, have helped to improve cultural aspects of those states. Mexican themed food has become incredibly popular in America with burrito and taco fast food shops opening up across the country. The new food & music has helped to improve the cultural diversity of America significantly.

With such a large number of Mexican migrants not speaking English fluently, it is now common for Spanish to be taught in American schools, widening the skill set of the younger population and improving the potential career opportunities that students may have. This also (slightly) helps ease social tensions caused by people speaking different languages which locals don’t understand.

With so many young people leaving Mexico, its developing an increasingly dependant population as the majority of people left are the elderly who can not work. Furthermore, the lack of young fertile couples is reducing the birth rate in Mexico, further increasing the dependency ratio as there is no workforce to pay taxes to support the elderly.

The majority of migrants leaving Mexico are males leaving a population with a high number of females. This is problematic as they are unable to find partners, get married and, in a mostly catholic country, have children (out of wedlock). This is, as mentioned above, reducing the birth rate and increasing the dependency ratio.

Mexican migrants often take low paying, menial jobs, which, while low paying, offer higher wages than what they’d earn in Mexico. This was, at first, advantageous, as many Americans did not want these low paying jobs but companies needed people to fill these jobs. Now, as unemployment rises in America, Americans want these menial jobs but many migrants already have taken the jobs. This can lead to increased social tension as Americans believe that their jobs are being taken.

Migrants work at incredibly low wages. Americans who are desperate for work are now often expected to work at these incredibly low wages too, which they can’t afford to do, leading to increased poverty in America. Many companies are now also replacing American labour with cheaper migrant labour, also increasing unemployment rates are people are forced out of their jobs.

While legal Mexican migrants are working & paying taxes, they often send money they earn back to their families in Mexico, rather than spending it in America, which can effect the country’s economy as there is less money being spent on products which are taxed in America. Conversely, the increased amount of money being sent back to Mexico is helping its economy greatly as people now have money to spend on goods and services.

As people move out of Mexico, pressure on land, social services and jobs is being relieved. Unemployment will fall and health services will no longer be over capacity as the population is reduced. The problem, however, arises when the young and skilled workforce leaves, resulting in a shortage of potential workers to fill these newly freed jobs and to work in these social services. A shortage of medically trained people, for example, could counteract the relieved health system.

Mexico’s population is very dependent on food grown in Mexico. Unfortunately, the majority of migrants come from rural areas, leaving a shortage of farmers and therefore the potential for food shortages in Mexico as the economically active people from rural areas leave.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Mexico’s tactic to cut immigration to the US: wear out migrants

Yeneska Garcia, a Venezuelan migrant, cries into her hands as she eats at the Peace Oasis of the Holy Spirit Amparito shelter in Villahermosa, Mexico, Friday, June 7, 2024. Since the 23-year-old fled Venezuela in January, she trekked days through the jungles of The Darien Gap, narrowly survived being kidnapped by Mexican cartels and waited months for an asylum appointment with the U.S. that never came through. (AP Photo/Felix Marquez)

Mexico is busing migrants back to its southern border. Driven by mounting pressure from the U.S. to block millions of vulnerable people headed north, but lacking the funds to deport them, Mexican authorities are wearing migrants out until they give up. (June 7-10) (AP/Felix Márquez)

- Copy Link copied