| Word Tools | | Finders & Helpers | | Apps | | More | | Synonyms | | | | | | |

| | Copyright WordHippo © 2024 | Synonyms for Thesis1 128 other terms for thesis - words and phrases with similar meaning.   - Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Synonyms and antonyms of thesis in English Word of the Day thirst for something Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio to feel very strongly that you want and need a particular thing  Fakes and forgeries (Things that are not what they seem to be) Learn more with +Plus- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

To add ${headword} to a word list please sign up or log in. Add ${headword} to one of your lists below, or create a new one. {{message}} Something went wrong. There was a problem sending your report. How To Write A Strong Thesis StatementA thesis statement is the most important part of an essay. It’s the roadmap, telling the reader what they can expect to read in the rest of paper, setting the tone for the writing, and generally providing a sense of the main idea. Because it is so important, writing a good thesis statement can be tricky. Before we get into the specifics, let’s review the basics: what thesis statement means. Thesis is a fancy word for “the subject of an essay” or “a position in a debate.” And a statement , simply, is a sentence (or a couple of sentences). Taken together, a thesis statement explains your subject or position in a sentence (or a couple of sentences). Depending on the kind of essay you’re writing, you’ll need to make sure that your thesis statement states your subject or position clearly. While the phrase thesis statement can sound intimidating, the basic goal is to clearly state your topic or your argument . Easy peasy! The basic rules for writing a thesis statement are: - State the topic or present your argument.

- Summarize the main idea of each of your details and/or body paragraphs.

- Keep your statement to one to two sentences.

Now comes the good stuff: the breakdown of how to write a good thesis statement for an informational essay and then for an argumentative essay (Yes, there are different types of thesis statements: check them all out here ). While the approach is similar for each, they require slightly different statements. Informational essay thesis statementsThe objective of an informational essay is to inform your audience about a specific topic. Sometimes, your essay will be in response to a specific question. Other times, you will be given a subject to write about more generally. In an informational essay , you are not arguing for one side of an argument, you are just providing information. Essays that are responding to a questionOften, you will be provided with a question to respond to in informational essay form. For example: - Who is your hero and why?

- How do scientists research the effects of zero gravity on plants?

- What are the three branches of government, and what do each of them do?

If you are given a question or prompt, use it as a starting point for your thesis statement. Remember, the goal of a thesis statement in an informational essay is to state your topic. You can use some of the same vocabulary and structure from the questions to create a thesis statement. Drop the question words (like who , what , when , where , and why ). Then, use the keywords in the question or prompt to start your thesis statement. Be sure to include because if the question asks “why?” Check out the following example using the first prompt: Original question : Who is your hero and why? Drop the question words : Who is your hero and why? Answer the question using the key words : My hero is Amelia Earhart, because she was very brave, did things many women of her time did not do, and was a hard worker. If we were to write the rest of the essay based on this thesis statement, the outline would look something like this: Introduction : My hero is Amelia Earhart, because she was very brave, did things many women of her time did not do, and was a hard worker. Body paragraph 1 : Details about how Amelia Earhart was brave Body paragraph 2 : Details about how she did things many women of her time did not do Body paragraph 3 : Details about how she was a hard worker Conclusion: It is clear that Amelia Earhart was a brave woman who accomplished many things that women of her time did not do, and always worked hard. These are the reasons why she is my hero. These general guidelines work for other thesis statements, with some minor differences. Essays that are responding to a statement or given subjectIf you aren’t given a specific question to respond to, it can be a little more difficult to decide on a thesis statement. However, there are some tricks you can use to make it easier. Some examples of prompts that are not questions are: - Write about your favorite sports team.

- Describe how a motor works.

- Pick a famous scientist and write about their life.

- Compare and contrast the themes of a poem and a short story.

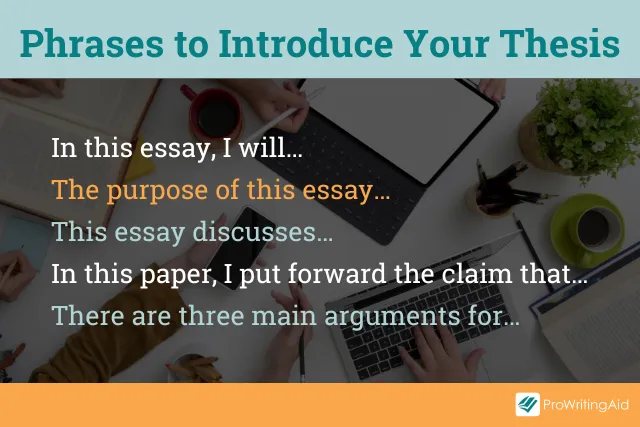

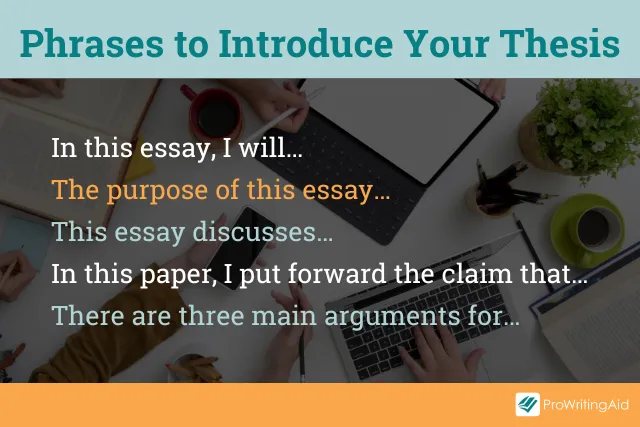

For these, we recommend using one of the following sentence starters to write your thesis with: - In this essay, I will …

- [Subject] is interesting/relevant/my favorite because …

- Through my research, I learned that …

As an example of how to use these sentence starters, we’ve put together some examples using the first prompt: Write about your favorite sports team. - In this essay, I will describe the history and cultural importance of the Pittsburgh Steelers, my favorite sports team.

- The Pittsburgh Steelers are my favorite because they have had a lasting impact on the history and culture of the city.

- Through my research, I learned that the Pittsburgh Steelers have had a lot of influence on the history and culture of Pittsburgh.

Any one of these thesis statements (or all three!) could be used for an informational essay about the Pittsburgh Steelers football team and their impact on the history and culture of Pittsburgh. Make Your Writing Shine! - By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Argumentative essay thesis statementsThe basic building blocks of an informational essay also apply when it comes to an argumentative essay . However, an argumentative essay requires that you take a position on an issue or prompt. You then have to attempt to persuade your reader that your argument is the best. That means that your argumentative thesis statement needs to do two things: - State your position on the issue.

- Summarize the evidence you will be using to defend your position.

Some examples of argumentative essay prompts are: - Should high school students be required to do volunteer work? Why or why not?

- What is the best way to cook a turkey?

- Some argue that video games are bad for society. Do you agree? Why or why not?

In order to create a good thesis statement for an argumentative essay, you have to be as specific as possible about your position and your evidence. Let’s take a look at the first prompt as an example: Prompt 1: Should high school students be required to do volunteer work? Why or why not? Bad thesis statement: No, I don’t think high school students should be required to do volunteer work because it’s boring. Good thesis statement: I think high school students should not be required to do volunteer work because it takes time away from their studies, provides more barriers to graduation, and does not encourage meaningful volunteer work. Let’s look at a couple other examples: Prompt 2: What is the best way to cook a turkey? Bad thesis statement: The best way to cook a turkey is the way my grandma does it. Good thesis statement: The best way to cook a turkey is using my grandmother’s recipe: brining the turkey beforehand, using a dry rub, and cooking at a low temperature. Prompt 3: Some argue that video games are bad for society. Do you agree? Why or why not? Bad thesis statement: Video games aren’t bad for society, because they’re super fun. Good thesis statement: Video games aren’t bad for society because they encourage cooperation, teach problem-solving skills, and provide hours of cheap entertainment. Do you notice the difference between the good thesis statements and the bad thesis statements? The bad statements are general, not specific. They also use very casual language. The good statements clearly lay out exactly what aspects of the argument your essay will focus on, in a professional manner. By the way, this same principle can also be applied to informational essay thesis statements. Take a look at this example for an idea: Prompt: What are the three branches of government, and what do each of them do? Bad thesis statement: There are many branches of government that do many different things. Good thesis statement: Each of the three branches of government—the executive, the legislative, and the judicial—have different primary responsibilities. However, these roles frequently overlap. In addition to being more specific than the bad thesis statement, the good thesis statement here is an example of how sometimes your thesis statement may require two sentences. Final thoughtsA thesis statement is the foundation of your essay. However, sometimes as you’re writing, you find that you’ve deviated from your original statement. Once you’ve finished writing your essay, go back and read your thesis statement. Ask yourself: - Does my thesis statement state the topic and/or my position?

- Does my thesis statement refer to the evidence or details I refer to in my essay?

- Is my thesis statement clear and easy to understand?

Don’t hesitate to edit your thesis statement if it doesn’t meet all three of these criteria. If it does, great! You’ve crafted a solid thesis statement that effectively guides the reader through your work. Now on to the rest of the essay!  Ways To Say Synonym of the dayLast places remaining for June 30th, July 14th and July 28th courses . Enrol now and join students from 175 countries for the summer of a lifetime  - 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered. Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them. It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills. If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership. General explainingLet’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points. 1. In order toUsage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.” 2. In other wordsUsage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.” 3. To put it another wayUsage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.” 4. That is to sayUsage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.” 5. To that endUsage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.” Adding additional information to support a pointStudents often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this. 6. MoreoverUsage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…” 7. FurthermoreUsage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…” 8. What’s moreUsage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.” 9. LikewiseUsage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.” 10. SimilarlyUsage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.” 11. Another key thing to rememberUsage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.” 12. As well asUsage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.” 13. Not only… but alsoUsage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.” 14. Coupled withUsage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…” 15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z. 16. Not to mention/to say nothing ofUsage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.” Words and phrases for demonstrating contrastWhen you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting. 17. HoweverUsage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.” 18. On the other handUsage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.” 19. Having said thatUsage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.” 20. By contrast/in comparisonUsage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.” 21. Then againUsage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.” 22. That saidUsage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.” Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.” Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservationsSometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so. 24. Despite thisUsage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.” 25. With this in mindUsage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.” 26. Provided thatUsage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.” 27. In view of/in light ofUsage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…” 28. NonethelessUsage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.” 29. NeverthelessUsage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.” 30. NotwithstandingUsage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.” Giving examplesGood essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing. 31. For instanceExample: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…” 32. To give an illustrationExample: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…” Signifying importanceWhen you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such. 33. SignificantlyUsage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.” 34. NotablyUsage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.” 35. ImportantlyUsage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.” SummarisingYou’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you. 36. In conclusionUsage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.” 37. Above allUsage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…” 38. PersuasiveUsage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.” 39. CompellingUsage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.” 40. All things consideredUsage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…” How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays. At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering . Comments are closed.  - UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

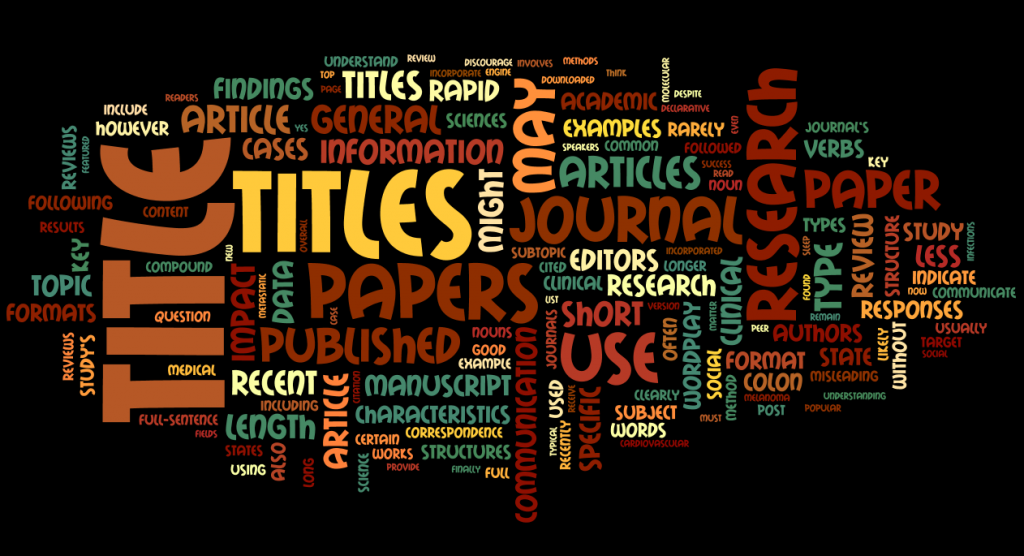

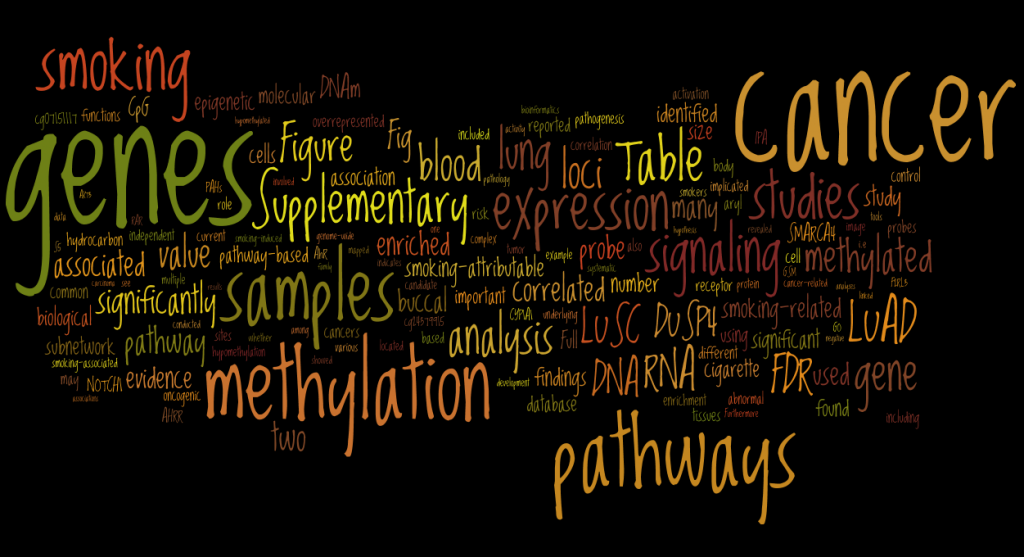

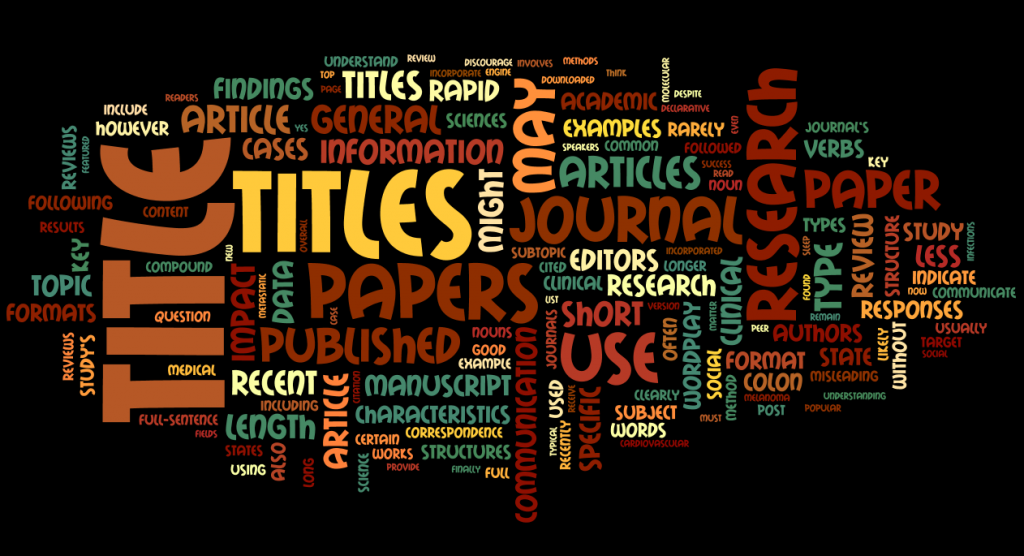

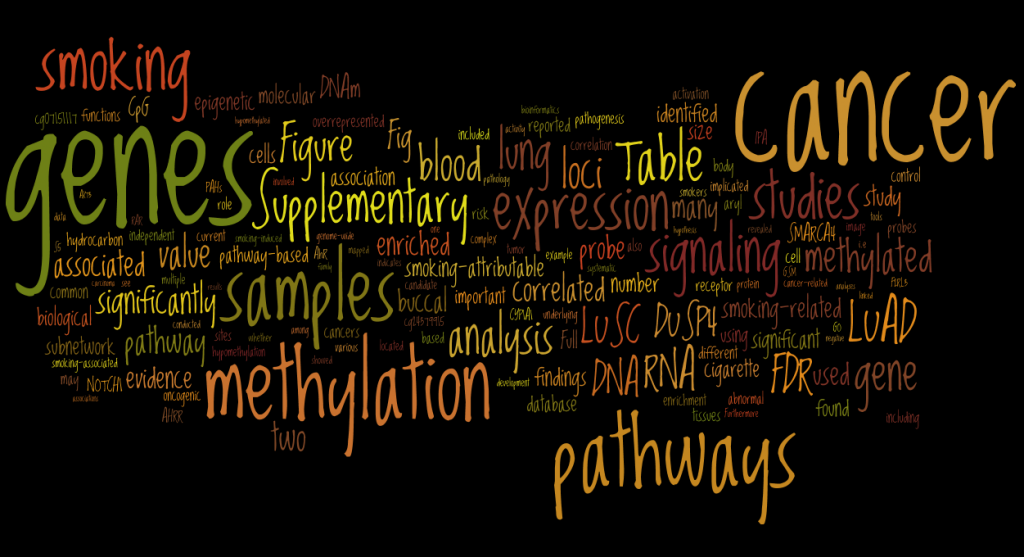

100+ Research Vocabulary Words & Phrases The academic community can be conservative when it comes to enforcing academic writing style , but your writing shouldn’t be so boring that people lose interest midway through the first paragraph! Given that competition is at an all-time high for academics looking to publish their papers, we know you must be anxious about what you can do to improve your publishing odds. To be sure, your research must be sound, your paper must be structured logically, and the different manuscript sections must contain the appropriate information. But your research must also be clearly explained. Clarity obviously depends on the correct use of English, and there are many common mistakes that you should watch out for, for example when it comes to articles , prepositions , word choice , and even punctuation . But even if you are on top of your grammar and sentence structure, you can still make your writing more compelling (or more boring) by using powerful verbs and phrases (vs the same weaker ones over and over). So, how do you go about achieving the latter? Below are a few ways to breathe life into your writing. 1. Analyze Vocabulary Using Word CloudsHave you heard of “Wordles”? A Wordle is a visual representation of words, with the size of each word being proportional to the number of times it appears in the text it is based on. The original company website seems to have gone out of business, but there are a number of free word cloud generation sites that allow you to copy and paste your draft manuscript into a text box to quickly discover how repetitive your writing is and which verbs you might want to replace to improve your manuscript. Seeing a visual word cloud of your work might also help you assess the key themes and points readers will glean from your paper. If the Wordle result displays words you hadn’t intended to emphasize, then that’s a sign you should revise your paper to make sure readers will focus on the right information. As an example, below is a Wordle of our article entitled, “ How to Choose the Best title for Your Journal Manuscript .” You can see how frequently certain terms appear in that post, based on the font size of the text. The keywords, “titles,” “journal,” “research,” and “papers,” were all the intended focus of our blog post.  2. Study Language Patterns of Similarly Published WorksStudy the language pattern found in the most downloaded and cited articles published by your target journal. Understanding the journal’s editorial preferences will help you write in a style that appeals to the publication’s readership. Another way to analyze the language of a target journal’s papers is to use Wordle (see above). If you copy and paste the text of an article related to your research topic into the applet, you can discover the common phrases and terms the paper’s authors used. For example, if you were writing a paper on links between smoking and cancer , you might look for a recent review on the topic, preferably published by your target journal. Copy and paste the text into Wordle and examine the key phrases to see if you’ve included similar wording in your own draft. The Wordle result might look like the following, based on the example linked above.  If you are not sure yet where to publish and just want some generally good examples of descriptive verbs, analytical verbs, and reporting verbs that are commonly used in academic writing, then have a look at this list of useful phrases for research papers . 3. Use More Active and Precise VerbsHave you heard of synonyms? Of course you have. But have you looked beyond single-word replacements and rephrased entire clauses with stronger, more vivid ones? You’ll find this task is easier to do if you use the active voice more often than the passive voice . Even if you keep your original sentence structure, you can eliminate weak verbs like “be” from your draft and choose more vivid and precise action verbs. As always, however, be careful about using only a thesaurus to identify synonyms. Make sure the substitutes fit the context in which you need a more interesting or “perfect” word. Online dictionaries such as the Merriam-Webster and the Cambridge Dictionary are good sources to check entire phrases in context in case you are unsure whether a synonym is a good match for a word you want to replace. To help you build a strong arsenal of commonly used phrases in academic papers, we’ve compiled a list of synonyms you might want to consider when drafting or editing your research paper . While we do not suggest that the phrases in the “Original Word/Phrase” column should be completely avoided, we do recommend interspersing these with the more dynamic terms found under “Recommended Substitutes.” A. Describing the scope of a current project or prior research| | | | To express the purpose of a paper or research | | This paper + [use the verb that originally followed “aims to”] or This paper + (any other verb listed above as a substitute for “explain”) + who/what/when/where/how X. For example: | | To introduce the topic of a project or paper | | | | To describe the analytical scope of a paper or study | | *Adjectives to describe degree can include: briefly, thoroughly, adequately, sufficiently, inadequately, insufficiently, only partially, partially, etc. | | To preview other sections of a paper | | [any of the verbs suggested as replacements for “explain,” “analyze,” and “consider” above] |

B. Outlining a topic’s background| | | | | To discuss the historical significance of a topic | | Topic significantly/considerably + + who/what/when/where/how… *In other words, take the nominalized verb and make it the main verb of the sentence. | | To describe the historical popularity of a topic | | verb] verb] | | To describe the recent focus on a topic | | | | To identify the current majority opinion about a topic | | | | To discuss the findings of existing literature | | | | To express the breadth of our current knowledge-base, including gaps | | | | To segue into expressing your research question | | |

C. Describing the analytical elements of a paper| | | | | To express agreement between one finding and another | | | | To present contradictory findings | | | | To discuss limitations of a study | | |

D. Discussing results| | | | | To draw inferences from results | | | | To describe observations | | |

E. Discussing methods| | | | | To discuss methods | | | | To describe simulations | | This study/ research… + “X environment/ condition to..” + [any of the verbs suggested as replacements for “analyze” above] |

F. Explaining the impact of new research| | | | | To explain the impact of a paper’s findings | | | | To highlight a paper’s conclusion | | | | To explain how research contributes to the existing knowledge-base | | |

Wordvice Writing ResourcesFor additional information on how to tighten your sentences (e.g., eliminate wordiness and use active voice to greater effect), you can try Wordvice’s FREE APA Citation Generator and learn more about how to proofread and edit your paper to ensure your work is free of errors. Before submitting your manuscript to academic journals, be sure to use our free AI Proofreader to catch errors in grammar, spelling, and mechanics. And use our English editing services from Wordvice, including academic editing services , cover letter editing , manuscript editing , and research paper editing services to make sure your work is up to a high academic level. We also have a collection of other useful articles for you, for example on how to strengthen your writing style , how to avoid fillers to write more powerful sentences , and how to eliminate prepositions and avoid nominalizations . Additionally, get advice on all the other important aspects of writing a research paper on our academic resources pages .  50 Useful Academic Words & Phrases for ResearchLike all good writing, writing an academic paper takes a certain level of skill to express your ideas and arguments in a way that is natural and that meets a level of academic sophistication. The terms, expressions, and phrases you use in your research paper must be of an appropriate level to be submitted to academic journals. Therefore, authors need to know which verbs , nouns , and phrases to apply to create a paper that is not only easy to understand, but which conveys an understanding of academic conventions. Using the correct terminology and usage shows journal editors and fellow researchers that you are a competent writer and thinker, while using non-academic language might make them question your writing ability, as well as your critical reasoning skills. What are academic words and phrases?One way to understand what constitutes good academic writing is to read a lot of published research to find patterns of usage in different contexts. However, it may take an author countless hours of reading and might not be the most helpful advice when faced with an upcoming deadline on a manuscript draft. Briefly, “academic” language includes terms, phrases, expressions, transitions, and sometimes symbols and abbreviations that help the pieces of an academic text fit together. When writing an academic text–whether it is a book report, annotated bibliography, research paper, research poster, lab report, research proposal, thesis, or manuscript for publication–authors must follow academic writing conventions. You can often find handy academic writing tips and guidelines by consulting the style manual of the text you are writing (i.e., APA Style , MLA Style , or Chicago Style ). However, sometimes it can be helpful to have a list of academic words and expressions like the ones in this article to use as a “cheat sheet” for substituting the better term in a given context. How to Choose the Best Academic TermsYou can think of writing “academically” as writing in a way that conveys one’s meaning effectively but concisely. For instance, while the term “take a look at” is a perfectly fine way to express an action in everyday English, a term like “analyze” would certainly be more suitable in most academic contexts. It takes up fewer words on the page and is used much more often in published academic papers. You can use one handy guideline when choosing the most academic term: When faced with a choice between two different terms, use the Latinate version of the term. Here is a brief list of common verbs versus their academic counterparts: | ) | | | add up | calculate | | carry out | execute | | find out | discover | | pass out | distribute | | ask questions about | interrogate | | make sense of | interpret | | pass on | distribute | Although this can be a useful tip to help academic authors, it can be difficult to memorize dozens of Latinate verbs. Using an AI paraphrasing tool or proofreading tool can help you instantly find more appropriate academic terms, so consider using such revision tools while you draft to improve your writing. Top 50 Words and Phrases for Different Sections in a Research PaperThe “Latinate verb rule” is just one tool in your arsenal of academic writing, and there are many more out there. But to make the process of finding academic language a bit easier for you, we have compiled a list of 50 vital academic words and phrases, divided into specific categories and use cases, each with an explanation and contextual example. Best Words and Phrases to use in an Introduction section1. historically. An adverb used to indicate a time perspective, especially when describing the background of a given topic. 2. In recent yearsA temporal marker emphasizing recent developments, often used at the very beginning of your Introduction section. 3. It is widely acknowledged thatA “form phrase” indicating a broad consensus among researchers and/or the general public. Often used in the literature review section to build upon a foundation of established scientific knowledge. 4. There has been growing interest inHighlights increasing attention to a topic and tells the reader why your study might be important to this field of research. 5. Preliminary observations indicateShares early insights or findings while hedging on making any definitive conclusions. Modal verbs like may , might , and could are often used with this expression. 6. This study aims toDescribes the goal of the research and is a form phrase very often used in the research objective or even the hypothesis of a research paper . 7. Despite its significanceHighlights the importance of a matter that might be overlooked. It is also frequently used in the rationale of the study section to show how your study’s aim and scope build on previous studies. 8. While numerous studies have focused onIndicates the existing body of work on a topic while pointing to the shortcomings of certain aspects of that research. Helps focus the reader on the question, “What is missing from our knowledge of this topic?” This is often used alongside the statement of the problem in research papers. 9. The purpose of this research isA form phrase that directly states the aim of the study. 10. The question arises (about/whether)Poses a query or research problem statement for the reader to acknowledge. Best Words and Phrases for Clarifying Information11. in other words. Introduces a synopsis or the rephrasing of a statement for clarity. This is often used in the Discussion section statement to explain the implications of the study . 12. That is to sayProvides clarification, similar to “in other words.” 13. To put it simplySimplifies a complex idea, often for a more general readership. 14. To clarifySpecifically indicates to the reader a direct elaboration of a previous point. 15. More specificallyNarrows down a general statement from a broader one. Often used in the Discussion section to clarify the meaning of a specific result. 16. To elaborateExpands on a point made previously. 17. In detailIndicates a deeper dive into information. Points out specifics. Similar meaning to “specifically” or “especially.” 19. This means thatExplains implications and/or interprets the meaning of the Results section . 20. MoreoverExpands a prior point to a broader one that shows the greater context or wider argument. Best Words and Phrases for Giving Examples21. for instance. Provides a specific case that fits into the point being made. 22. As an illustrationDemonstrates a point in full or in part. 23. To illustrateShows a clear picture of the point being made. 24. For examplePresents a particular instance. Same meaning as “for instance.” 25. Such asLists specifics that comprise a broader category or assertion being made. 26. IncludingOffers examples as part of a larger list. 27. NotablyAdverb highlighting an important example. Similar meaning to “especially.” 28. EspeciallyAdverb that emphasizes a significant instance. 29. In particularDraws attention to a specific point. 30. To name a fewIndicates examples than previously mentioned are about to be named. Best Words and Phrases for Comparing and Contrasting31. however. Introduces a contrasting idea. 32. On the other handHighlights an alternative view or fact. 33. ConverselyIndicates an opposing or reversed idea to the one just mentioned.  34. SimilarlyShows likeness or parallels between two ideas, objects, or situations. 35. LikewiseIndicates agreement with a previous point. 36. In contrastDraws a distinction between two points. 37. NeverthelessIntroduces a contrasting point, despite what has been said. 38. WhereasCompares two distinct entities or ideas. Indicates a contrast between two points. Signals an unexpected contrast. Best Words and Phrases to use in a Conclusion section41. in conclusion. Signifies the beginning of the closing argument. 42. To sum upOffers a brief summary. 43. In summarySignals a concise recap. 44. UltimatelyReflects the final or main point. 45. OverallGives a general concluding statement. Indicates a resulting conclusion. Demonstrates a logical conclusion. 48. ThereforeConnects a cause and its effect. 49. It can be concluded thatClearly states a conclusion derived from the data. 50. Taking everything into considerationReflects on all the discussed points before concluding. Edit Your Research Terms and Phrases Before SubmissionUsing these phrases in the proper places in your research papers can enhance the clarity, flow, and persuasiveness of your writing, especially in the Introduction section and Discussion section, which together make up the majority of your paper’s text in most academic domains. However, it's vital to ensure each phrase is contextually appropriate to avoid redundancy or misinterpretation. As mentioned at the top of this article, the best way to do this is to 1) use an AI text editor , free AI paraphrasing tool or AI proofreading tool while you draft to enhance your writing, and 2) consult a professional proofreading service like Wordvice, which has human editors well versed in the terminology and conventions of the specific subject area of your academic documents. For more detailed information on using AI tools to write a research paper and the best AI tools for research , check out the Wordvice AI Blog . - Find a Teacher

- Currency ( RUB )

- Site Language

- 50 linking words to use in academic writing

Fiona Oates - Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

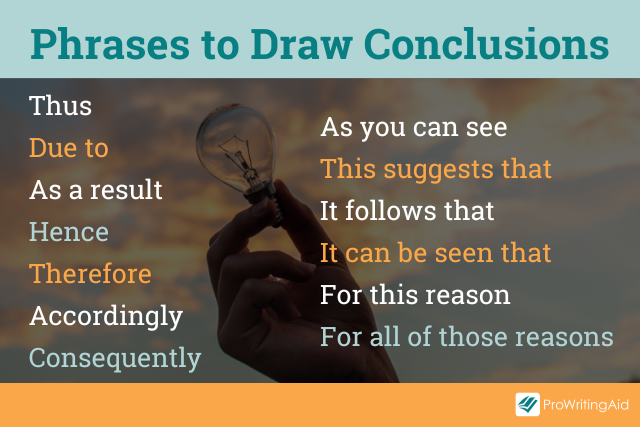

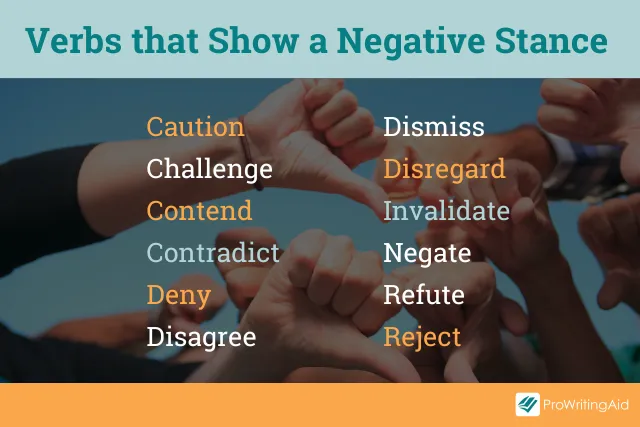

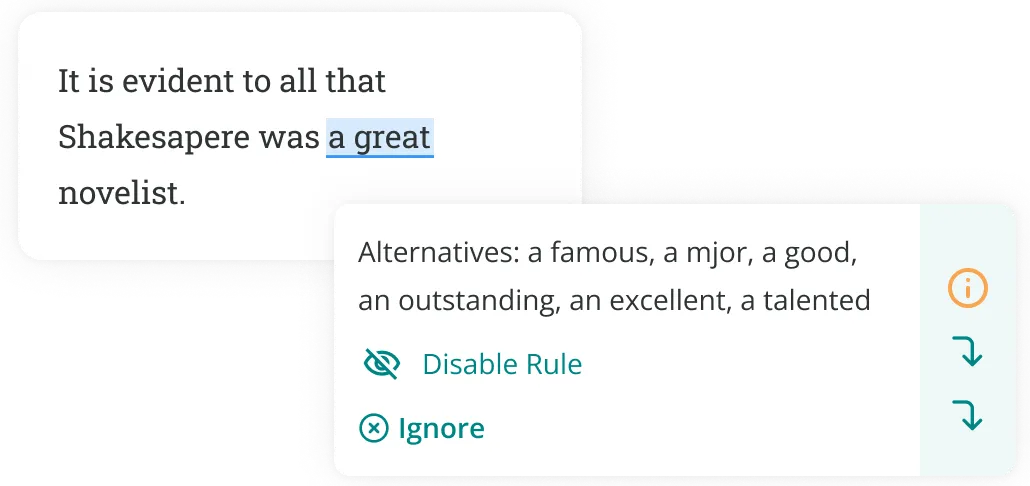

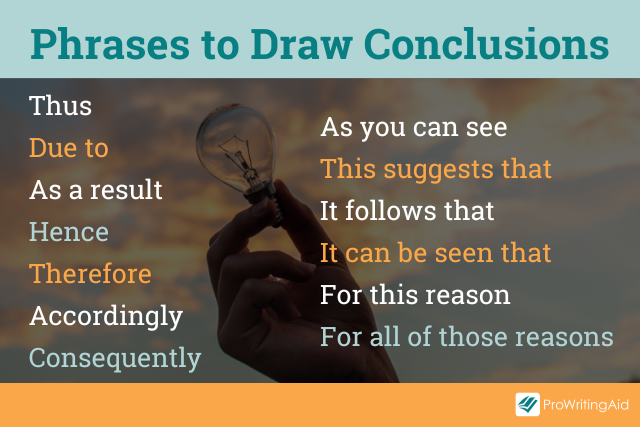

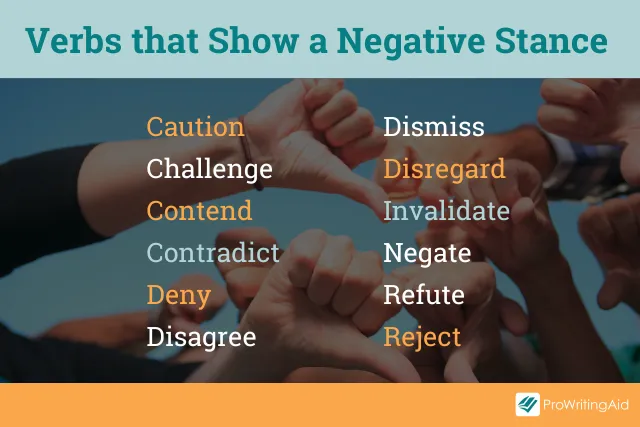

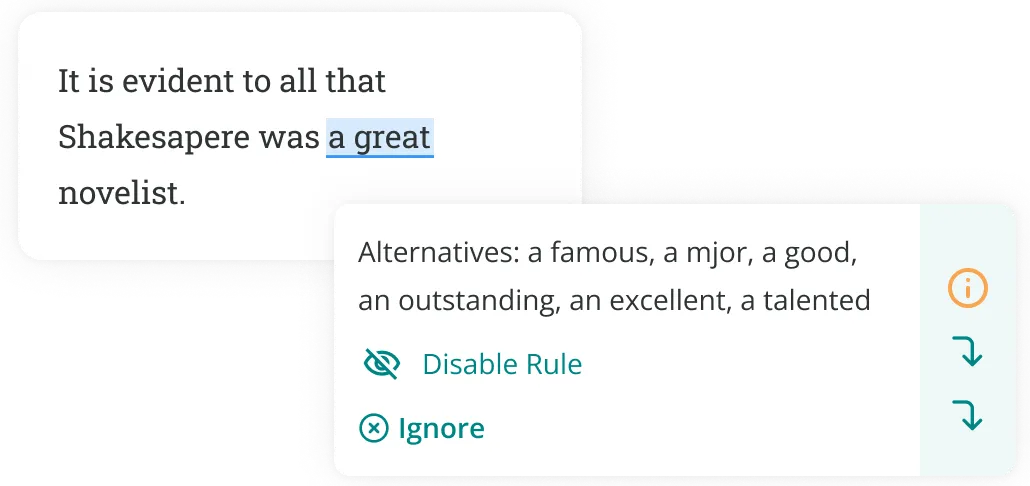

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words Hannah Yang Table of ContentsWords to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary. It’s not easy to write an academic essay . Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way. To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life. If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place! In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay. The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write. You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay. That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay. Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay. When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases: To use the words of X According to X As X states Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.” Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper. If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases: In this essay, I will… The purpose of this essay… This essay discusses… In this paper, I put forward the claim that… There are three main arguments for…  Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students. After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea. When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words: First and foremost First of all To begin with Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers. All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on. The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence. It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research. Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence. Transition Words and PhrasesTransitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay. It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random. Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional. The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea: Additionally In addition Furthermore Another key thing to remember In the same way Correspondingly Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces. Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words: In other words To put it another way That is to say To put it more simply Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.” Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words: For instance To give an illustration of To exemplify To demonstrate As evidence Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward. Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said. When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words: As a result Accordingly As you can see This suggests that It follows that It can be seen that For this reason For all of those reasons Consequently Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”  When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words: What’s more Not only…but also Not to mention To say nothing of Another key point Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct. Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words: On the one hand / on the other hand Alternatively In contrast to On the contrary By contrast In comparison Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived. Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases: Having said that Differing from In spite of With this in mind Provided that Nevertheless Nonetheless Notwithstanding Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century. Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay. Strong Verbs for Academic WritingVerbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb. You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb. For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail. Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine. Verbs that show change: Accommodate Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something: Verbs that show increase: Verbs that show decrease: Deteriorate Verbs that relate to parts of a whole: Comprises of Is composed of Constitutes Encompasses Incorporates Verbs that show a negative stance: Misconstrue  Verbs that show a positive stance: Substantiate Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence: Corroborate Demonstrate Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis: Contemplate Hypothesize Investigate Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format: Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic EssaysYou should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences. However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay. Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis: Significant Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis: Controversial Insignificant Questionable Unnecessary Unrealistic Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays: Comprehensively Exhaustively Extensively Respectively Surprisingly Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion. The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis. In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words: In conclusion To summarize In a nutshell Given the above As described All things considered Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever. In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought. To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words: Unquestionably Undoubtedly Particularly Importantly Conclusively It should be noted On the whole Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure. These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way. There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics. If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature. So how do you improve your vocabulary skills? The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words. One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading. Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays. You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay. Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible. Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.  There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!  Good writing = better gradesProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments. Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates. Get started with ProWritingAidDrop us a line or let's stay in touch via : Recent Posts- How to Hook Your Readers with a Compelling Topic Sentence

- Is a Thesis Writing Format Easy? A Comprehensive Guide to Thesis Writing

- The Complete Guide to Copy Editing: Roles, Rates, Skills, and Process

How to Write a Paragraph: Successful Essay Writing Strategies- Everything You Should Know About Academic Writing: Types, Importance, and Structure

- Concise Writing: Tips, Importance, and Exercises for a Clear Writing Style

- How to Write a PhD Thesis: A Step-by-Step Guide for Success

- How to Use AI in Essay Writing: Tips, Tools, and FAQs

- Copy Editing Vs Proofreading: What’s The Difference?

- How Much Does It Cost To Write A Thesis? Get Complete Process & Tips

- Academic News

- Custom Essays

- Dissertation Writing

- Essay Marking

- Essay Writing

- Essay Writing Companies

- Model Essays

- Model Exam Answers

- Oxbridge Essays Updates

- PhD Writing

- Significant Academics

- Student News

- Study Skills

- University Applications

- University Essays

- University Life

- Writing Tips

17 academic words and phrases to use in your essay(Last updated: 20 October 2022) Since 2006, Oxbridge Essays has been the UK’s leading paid essay-writing and dissertation serviceWe have helped 10,000s of undergraduate, Masters and PhD students to maximise their grades in essays, dissertations, model-exam answers, applications and other materials. If you would like a free chat about your project with one of our UK staff, then please just reach out on one of the methods below. For the vast majority of students, essay writing doesn't always come easily. Writing at academic level is an acquired skill that can literally take years to master – indeed, many students find they only start to feel really confident writing essays just as their undergraduate course comes to an end! If this is you, and you've come here looking for words and phrases to use in your essay, you're in the right place. We’ve pulled together a list of essential academic words you can use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essays . Whilst your ideas and arguments should always be your own, borrowing some of the words and phrases listed below is a great way to articulate your ideas more effectively, and ensure that you keep your reader’s attention from start to finish. It goes without saying (but we'll say it anyway) that there's a certain formality that comes with academic writing. Casual and conversational phrases have no place. Obviously, there are no LOLs, LMFAOs, and OMGs. But formal academic writing can be much more subtle than this, and as we've mentioned above, requires great skill. So, to get you started on polishing your own essay writing ability, try using the words in this list as an inspirational starting point. Words to use in your introductionThe trickiest part of academic writing often comes right at the start, with your introduction. Of course, once you’ve done your plan and have your arguments laid out, you need to actually put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard) and begin your essay. You need to consider that your reader doesn’t have a clue about your topic or arguments, so your first sentence must summarise these. Explain what your essay is going to talk about as though you were explaining it to a five year old – without losing the formality of your academic writing, of course! To do this, use any of the below words or phrases to help keep you on track. 1. Firstly, secondly, thirdlyEven though it sounds obvious, your argument will be clearer if you deliver the ideas in the right order. These words can help you to offer clarity and structure to the way you expose your ideas. This is an extremely effective method of presenting the facts clearly. Don’t be too rigid and feel you have to number each point, but using this system can be a good way to get an argument off the ground, and link arguments together. 2. In view of; in light of; consideringThese essay phrases are useful to begin your essay. They help you pose your argument based on what other authors have said or a general concern about your research. They can also both be used when a piece of evidence sheds new light on an argument. Here’s an example: The result of the American invasion has severely impaired American interests in the Middle East, exponentially increasing popular hostility to the United States throughout the region, a factor which has proved to be a powerful recruitment tool for extremist terrorist groups (Isakhan, 2015). Considering [or In light of / In view of] the perceived resulting threat to American interests, it could be argued that the Bush administration failed to fully consider the impact of their actions before pushing forward with the war. 3. According to X; X stated that; referring to the views of XIntroducing the views of an author who has a comprehensive knowledge of your particular area of study is a crucial part of essay writing. Including a quote that fits naturally into your work can be a bit of a struggle, but these academic phrases provide a great way in. Even though it’s fine to reference a quote in your introduction, we don’t recommend you start your essay with a direct quote. Use your own words to sum up the views you’re mentioning, for example: As Einstein often reiterated, experiments can prove theories, but experiments don’t give birth to theories. Rather than: “A theory can be proved by experiment, but no path leads from experiment to the birth of a theory.” {Albert Einstein, 1954, Einstein: A Biography}. See the difference? And be sure to reference correctly too, when using quotes or paraphrasing someone else's words.  Adding information and flowThe flow of your essay is extremely important. You don’t want your reader to be confused by the rhythm of your writing and get distracted away from your argument, do you? No! So, we recommend using some of the following ‘flow’ words, which are guaranteed to help you articulate your ideas and arguments in a chronological and structured order. 4. Moreover; furthermore; in addition; what’s moreThese types of academic phrases are perfect for expanding or adding to a point you’ve already made without interrupting the flow altogether. “Moreover”, “furthermore” and “in addition” are also great linking phrases to begin a new paragraph. Here are some examples: The dissociation of tau protein from microtubules destabilises the latter resulting in changes to cell structure, and neuronal transport. Moreover, mitochondrial dysfunction leads to further oxidative stress causing increased levels of nitrous oxide, hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxidases. On the data of this trial, no treatment recommendations should be made. The patients are suspected, but not confirmed, to suffer from pneumonia. Furthermore, five days is too short a follow up time to confirm clinical cure. 5. In order to; to that end; to this endThese are helpful academic phrases to introduce an explanation or state your aim. Oftentimes your essay will have to prove how you intend to achieve your goals. By using these sentences you can easily expand on points that will add clarity to the reader. For example: My research entailed hours of listening and recording the sound of whales in order to understand how they communicate. Dutch tech companies offer support in the fight against the virus. To this end, an online meeting took place on Wednesday... Even though we recommend the use of these phrases, DO NOT use them too often. You may think you sound like a real academic but it can be a sign of overwriting! 6. In other words; to put it another way; that is; to put it more simplyComplement complex ideas with simple descriptions by using these sentences. These are excellent academic phrases to improve the continuity of your essay writing. They should be used to explain a point you’ve already made in a slightly different way. Don’t use them to repeat yourself, but rather to elaborate on a certain point that needs further explanation. Or, to succinctly round up what just came before. For example: A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between phenomena. In other words, there is no treatment effect. Nothing could come to be in this pre-world time, “because no part of such a time possesses, as compared with any other, a distinguishing condition of existence rather than non-existence.” That is, nothing exists in this pre-world time, and so there can be nothing that causes the world to come into existence. 7. Similarly; likewise; another key fact to remember; as well as; an equally significant aspect ofThese essay words are a good choice to add a piece of information that agrees with an argument or fact you just mentioned. In academic writing, it is very relevant to include points of view that concur with your opinion. This will help you to situate your research within a research context. Also , academic words and phrases like the above are also especially useful so as not to repeat the word ‘also’ too many times. (We did that on purpose to prove our point!) Your reader will be put off by the repetitive use of simple conjunctions. The quality of your essay will drastically improve just by using academic phrases and words such as ‘similarly’, ‘as well as’, etc. Here, let us show you what we mean: In 1996, then-transport minister Steve Norris enthused about quadrupling cycling trips by 2012. Similarly, former prime minister David Cameron promised a “cycling revolution” in 2013… Or Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI) aims to bridge the gap of access to electricity across the continent (...). Another key fact to remember is that it must expand cost-efficient access to electricity to nearly 1 billion people. The wording “not only… but also” is a useful way to elaborate on a similarity in your arguments but in a more striking way.  Comparing and contrasting informationAcademic essays often include opposite opinions or information in order to prove a point. It is important to show all the aspects that are relevant to your research. Include facts and researchers’ views that disagree with a point of your essay to show your knowledge of your particular field of study. Below are a few words and ways of introducing alternative arguments. 8. Conversely; however; alternatively; on the contrary; on the other hand; whereasFinding a seamless method to present an alternative perspective or theory can be hard work, but these terms and phrases can help you introduce the other side of the argument. Let's look at some examples: 89% of respondents living in joint families reported feeling financially secure. Conversely, only 64% of those who lived in nuclear families said they felt financially secure. The first protagonist has a social role to fill in being a father to those around him, whereas the second protagonist relies on the security and knowledge offered to him by Chaplin. “On the other hand” can also be used to make comparisons when worded together with “on the one hand.” 9. By contrast; in comparison; then again; that said; yetThese essay phrases show contrast, compare facts, and present uncertainty regarding a point in your research. “That said” and “yet” in particular will demonstrate your expertise on a topic by showing the conditions or limitations of your research area. For example: All the tests were positive. That said, we must also consider the fact that some of them had inconclusive results. 10. Despite this; provided that; nonethelessUse these phrases and essay words to demonstrate a positive aspect of your subject-matter regardless of lack of evidence, logic, coherence, or criticism. Again, this kind of information adds clarity and expertise to your academic writing. A good example is: Despite the criticism received by X, the popularity of X remains undiminished. 11. Importantly; significantly; notably; another key pointAnother way to add contrast is by highlighting the relevance of a fact or opinion in the context of your research. These academic words help to introduce a sentence or paragraph that contains a very meaningful point in your essay. Giving examplesA good piece of academic writing will always include examples. Illustrating your essay with examples will make your arguments stronger. Most of the time, examples are a way to clarify an explanation; they usually offer an image that the reader can recognise. The most common way to introduce an illustration is “for example.” However, in order not to repeat yourself here are a few other options. 12. For instance; to give an illustration of; to exemplify; to demonstrate; as evidence; to elucidateThe academic essays that are receiving top marks are the ones that back up every single point made. These academic phrases are a useful way to introduce an example. If you have a lot of examples, avoid repeating the same phrase to facilitate the readability of your essay. Here’s an example: ‘High involvement shopping’, an experiential process described by Wu et al. (2015, p. 299) relies upon the development of an identity-based alliance between the customer and the brand. Celebrity status at Prada, for example, has created an alliance between the brand and a new generation of millennial customers.  Concluding your essayConcluding words for essays are necessary to wrap up your argument. Your conclusion must include a brief summary of the ideas that you just exposed without being redundant. The way these ideas are expressed should lead to the final statement and core point you have arrived at in your present research. 13. In conclusion; to conclude; to summarise; in sum; in the final analysis; on close analysisThese are phrases for essays that will introduce your concluding paragraph. You can use them at the beginning of a sentence. They will show the reader that your essay is coming to an end: On close analysis and appraisal, we see that the study by Cortis lacks essential features of the highest quality quantitative research. 14. Persuasive; compellingEssay words like these ones can help you emphasize the most relevant arguments of your paper. Both are used in the same way: “the most persuasive/compelling argument is…”. 15. Therefore; this suggests that; it can be seen that; the consequence isWhen you’re explaining the significance of the results of a piece of research, these phrases provide the perfect lead up to your explanation. 16. Above all; chiefly; especially; most significantly; it should be notedYour summary should include the most relevant information or research factor that guided you to your conclusion. Contrary to words such as “persuasive” or “compelling”, these essay words are helpful to draw attention to an important point. For example: The feasibility and effectiveness of my research has been proven chiefly in the last round of laboratory tests. Film noir is, and will continue to be, highly debatable, controversial, and unmarketable – but above all, for audience members past, present and to come, extremely enjoyable as a form of screen media entertainment. 17. All things consideredThis essay phrase is meant to articulate how you give reasons to your conclusions. It means that after you considered all the aspects related to your study, you have arrived to the conclusion you are demonstrating. After mastering the use of these academic words and phrases, we guarantee you will see an immediate change in the quality of your essays. The structure will be easier to follow, and the reader’s experience will improve. You’ll also feel more confident articulating your ideas and using facts and examples. So jot them all down, and watch your essays go from ‘good’ to ‘great’!  Essay exams: how to answer ‘To what extent…’ How to write a master’s essay - academic writing

- writing a good essay

- writing essays

- writing tips

Writing Services- Essay Plans

- Critical Reviews

- Literature Reviews

- Presentations

- Dissertation Title Creation

- Dissertation Proposals

- Dissertation Chapters

- PhD Proposals

- Journal Publication

- CV Writing Service

- Business Proofreading Services

Editing Services- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- Academic Editing Service

Additional Services- Marking Services

- Consultation Calls

- Personal Statements

- Tutoring Services

Our Company- Frequently Asked Questions

- Become a Writer

Terms & Policies- Fair Use Policy

- Policy for Students in England

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- [email protected]

- Contact Form

Payment MethodsCryptocurrency payments.  Word ChoiceWhat this handout is about. This handout can help you revise your papers for word-level clarity, eliminate wordiness and avoid clichés, find the words that best express your ideas, and choose words that suit an academic audience. IntroductionWriting is a series of choices. As you work on a paper, you choose your topic, your approach, your sources, and your thesis; when it’s time to write, you have to choose the words you will use to express your ideas and decide how you will arrange those words into sentences and paragraphs. As you revise your draft, you make more choices. You might ask yourself, “Is this really what I mean?” or “Will readers understand this?” or “Does this sound good?” Finding words that capture your meaning and convey that meaning to your readers is challenging. When your instructors write things like “awkward,” “vague,” or “wordy” on your draft, they are letting you know that they want you to work on word choice. This handout will explain some common issues related to word choice and give you strategies for choosing the best words as you revise your drafts. As you read further into the handout, keep in mind that it can sometimes take more time to “save” words from your original sentence than to write a brand new sentence to convey the same meaning or idea. Don’t be too attached to what you’ve already written; if you are willing to start a sentence fresh, you may be able to choose words with greater clarity. For tips on making more substantial revisions, take a look at our handouts on reorganizing drafts and revising drafts . “Awkward,” “vague,” and “unclear” word choiceSo: you write a paper that makes perfect sense to you, but it comes back with “awkward” scribbled throughout the margins. Why, you wonder, are instructors so fond of terms like “awkward”? Most instructors use terms like this to draw your attention to sentences they had trouble understanding and to encourage you to rewrite those sentences more clearly. Difficulties with word choice aren’t the only cause of awkwardness, vagueness, or other problems with clarity. Sometimes a sentence is hard to follow because there is a grammatical problem with it or because of the syntax (the way the words and phrases are put together). Here’s an example: “Having finished with studying, the pizza was quickly eaten.” This sentence isn’t hard to understand because of the words I chose—everybody knows what studying, pizza, and eating are. The problem here is that readers will naturally assume that first bit of the sentence “(Having finished with studying”) goes with the next noun that follows it—which, in this case, is “the pizza”! It doesn’t make a lot of sense to imply that the pizza was studying. What I was actually trying to express was something more like this: “Having finished with studying, the students quickly ate the pizza.” If you have a sentence that has been marked “awkward,” “vague,” or “unclear,” try to think about it from a reader’s point of view—see if you can tell where it changes direction or leaves out important information. Sometimes, though, problems with clarity are a matter of word choice. See if you recognize any of these issues: - Misused words —the word doesn’t actually mean what the writer thinks it does. Example : Cree Indians were a monotonous culture until French and British settlers arrived. Revision: Cree Indians were a homogenous culture.

- Words with unwanted connotations or meanings. Example : I sprayed the ants in their private places. Revision: I sprayed the ants in their hiding places.

- Using a pronoun when readers can’t tell whom/what it refers to. Example : My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though he didn’t like him very much. Revision: My cousin Jake hugged my brother Trey, even though Jake doesn’t like Trey very much.

- Jargon or technical terms that make readers work unnecessarily hard. Maybe you need to use some of these words because they are important terms in your field, but don’t throw them in just to “sound smart.” Example : The dialectical interface between neo-Platonists and anti-disestablishment Catholics offers an algorithm for deontological thought. Revision : The dialogue between neo-Platonists and certain Catholic thinkers is a model for deontological thought.

- Loaded language. Sometimes we as writers know what we mean by a certain word, but we haven’t ever spelled that out for readers. We rely too heavily on that word, perhaps repeating it often, without clarifying what we are talking about. Example : Society teaches young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change society. Revision : Contemporary American popular media, like magazines and movies, teach young girls that beauty is their most important quality. In order to prevent eating disorders and other health problems, we must change the images and role models girls are offered.