A Step-by-Step Plan for Teaching Narrative Writing

July 29, 2018

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Peergrade and Microsoft Class Notebook

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

“Those who tell the stories rule the world.” This proverb, attributed to the Hopi Indians, is one I wish I’d known a long time ago, because I would have used it when teaching my students the craft of storytelling. With a well-told story we can help a person see things in an entirely new way. We can forge new relationships and strengthen the ones we already have. We can change a law, inspire a movement, make people care fiercely about things they’d never given a passing thought.

But when we study storytelling with our students, we forget all that. Or at least I did. When my students asked why we read novels and stories, and why we wrote personal narratives and fiction, my defense was pretty lame: I probably said something about the importance of having a shared body of knowledge, or about the enjoyment of losing yourself in a book, or about the benefits of having writing skills in general.

I forgot to talk about the power of story. I didn’t bother to tell them that the ability to tell a captivating story is one of the things that makes human beings extraordinary. It’s how we connect to each other. It’s something to celebrate, to study, to perfect. If we’re going to talk about how to teach students to write stories, we should start by thinking about why we tell stories at all . If we can pass that on to our students, then we will be going beyond a school assignment; we will be doing something transcendent.

Now. How do we get them to write those stories? I’m going to share the process I used for teaching narrative writing. I used this process with middle school students, but it would work with most age groups.

A Note About Form: Personal Narrative or Short Story?

When teaching narrative writing, many teachers separate personal narratives from short stories. In my own classroom, I tended to avoid having my students write short stories because personal narratives were more accessible. I could usually get students to write about something that really happened, while it was more challenging to get them to make something up from scratch.

In the “real” world of writers, though, the main thing that separates memoir from fiction is labeling: A writer might base a novel heavily on personal experiences, but write it all in third person and change the names of characters to protect the identities of people in real life. Another writer might create a short story in first person that reads like a personal narrative, but is entirely fictional. Just last weekend my husband and I watched the movie Lion and were glued to the screen the whole time, knowing it was based on a true story. James Frey’s book A Million Little Pieces sold millions of copies as a memoir but was later found to contain more than a little bit of fiction. Then there are unique books like Curtis Sittenfeld’s brilliant novel American Wife , based heavily on the early life of Laura Bush but written in first person, with fictional names and settings, and labeled as a work of fiction. The line between fact and fiction has always been really, really blurry, but the common thread running through all of it is good storytelling.

With that in mind, the process for teaching narrative writing can be exactly the same for writing personal narratives or short stories; it’s the same skill set. So if you think your students can handle the freedom, you might decide to let them choose personal narrative or fiction for a narrative writing assignment, or simply tell them that whether the story is true doesn’t matter, as long as they are telling a good story and they are not trying to pass off a fictional story as fact.

Here are some examples of what that kind of flexibility could allow:

- A student might tell a true story from their own experience, but write it as if it were a fiction piece, with fictional characters, in third person.

- A student might create a completely fictional story, but tell it in first person, which would give it the same feel as a personal narrative.

- A student might tell a true story that happened to someone else, but write it in first person, as if they were that person. For example, I could write about my grandmother’s experience of getting lost as a child, but I might write it in her voice.

If we aren’t too restrictive about what we call these pieces, and we talk about different possibilities with our students, we can end up with lots of interesting outcomes. Meanwhile, we’re still teaching students the craft of narrative writing.

A Note About Process: Write With Your Students

One of the most powerful techniques I used as a writing teacher was to do my students’ writing assignments with them. I would start my own draft at the same time as they did, composing “live” on the classroom projector, and doing a lot of thinking out loud so they could see all the decisions a writer has to make.

The most helpful parts for them to observe were the early drafting stage, where I just scratched out whatever came to me in messy, run-on sentences, and the revision stage, where I crossed things out, rearranged, and made tons of notes on my writing. I have seen over and over again how witnessing that process can really help to unlock a student’s understanding of how writing actually gets made.

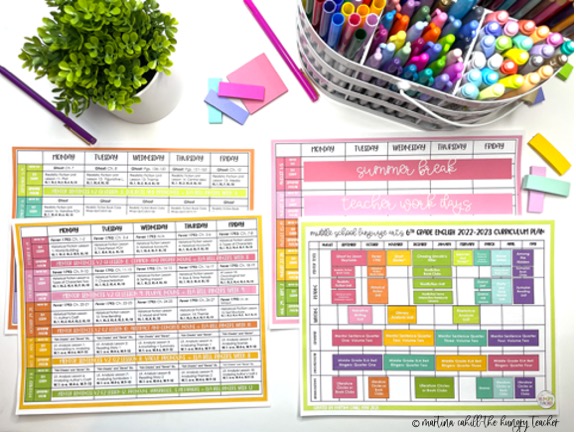

A Narrative Writing Unit Plan

Before I get into these steps, I should note that there is no one right way to teach narrative writing, and plenty of accomplished teachers are doing it differently and getting great results. This just happens to be a process that has worked for me.

Step 1: Show Students That Stories Are Everywhere

Getting our students to tell stories should be easy. They hear and tell stories all the time. But when they actually have to put words on paper, they forget their storytelling abilities: They can’t think of a topic. They omit relevant details, but go on and on about irrelevant ones. Their dialogue is bland. They can’t figure out how to start. They can’t figure out how to end.

So the first step in getting good narrative writing from students is to help them see that they are already telling stories every day . They gather at lockers to talk about that thing that happened over the weekend. They sit at lunch and describe an argument they had with a sibling. Without even thinking about it, they begin sentences with “This one time…” and launch into stories about their earlier childhood experiences. Students are natural storytellers; learning how to do it well on paper is simply a matter of studying good models, then imitating what those writers do.

So start off the unit by getting students to tell their stories. In journal quick-writes, think-pair-shares, or by playing a game like Concentric Circles , prompt them to tell some of their own brief stories: A time they were embarrassed. A time they lost something. A time they didn’t get to do something they really wanted to do. By telling their own short anecdotes, they will grow more comfortable and confident in their storytelling abilities. They will also be generating a list of topic ideas. And by listening to the stories of their classmates, they will be adding onto that list and remembering more of their own stories.

And remember to tell some of your own. Besides being a good way to bond with students, sharing your stories will help them see more possibilities for the ones they can tell.

Step 2: Study the Structure of a Story

Now that students have a good library of their own personal stories pulled into short-term memory, shift your focus to a more formal study of what a story looks like.

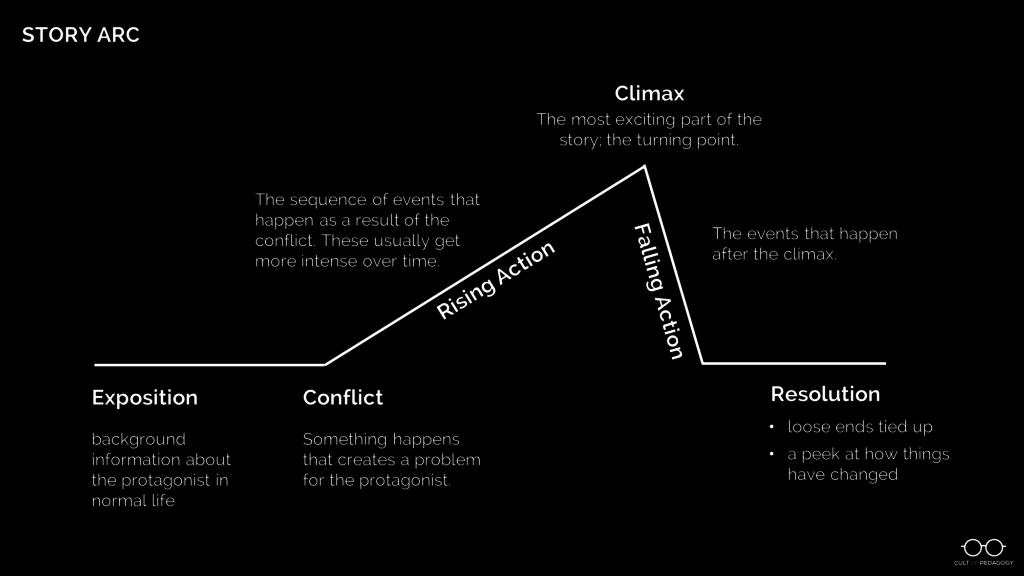

Use a diagram to show students a typical story arc like the one below. Then, using a simple story (try a video like The Present or Room ), fill out the story arc with the components from that story. Once students have seen this story mapped out, have them try it with another one, like a story you’ve read in class, a whole novel, or another short video.

Step 3: Introduce the Assignment

Up to this point, students have been immersed in storytelling. Now give them specific instructions for what they are going to do. Share your assignment rubric so they understand the criteria that will be used to evaluate them; it should be ready and transparent right from the beginning of the unit. As always, I recommend using a single point rubric for this.

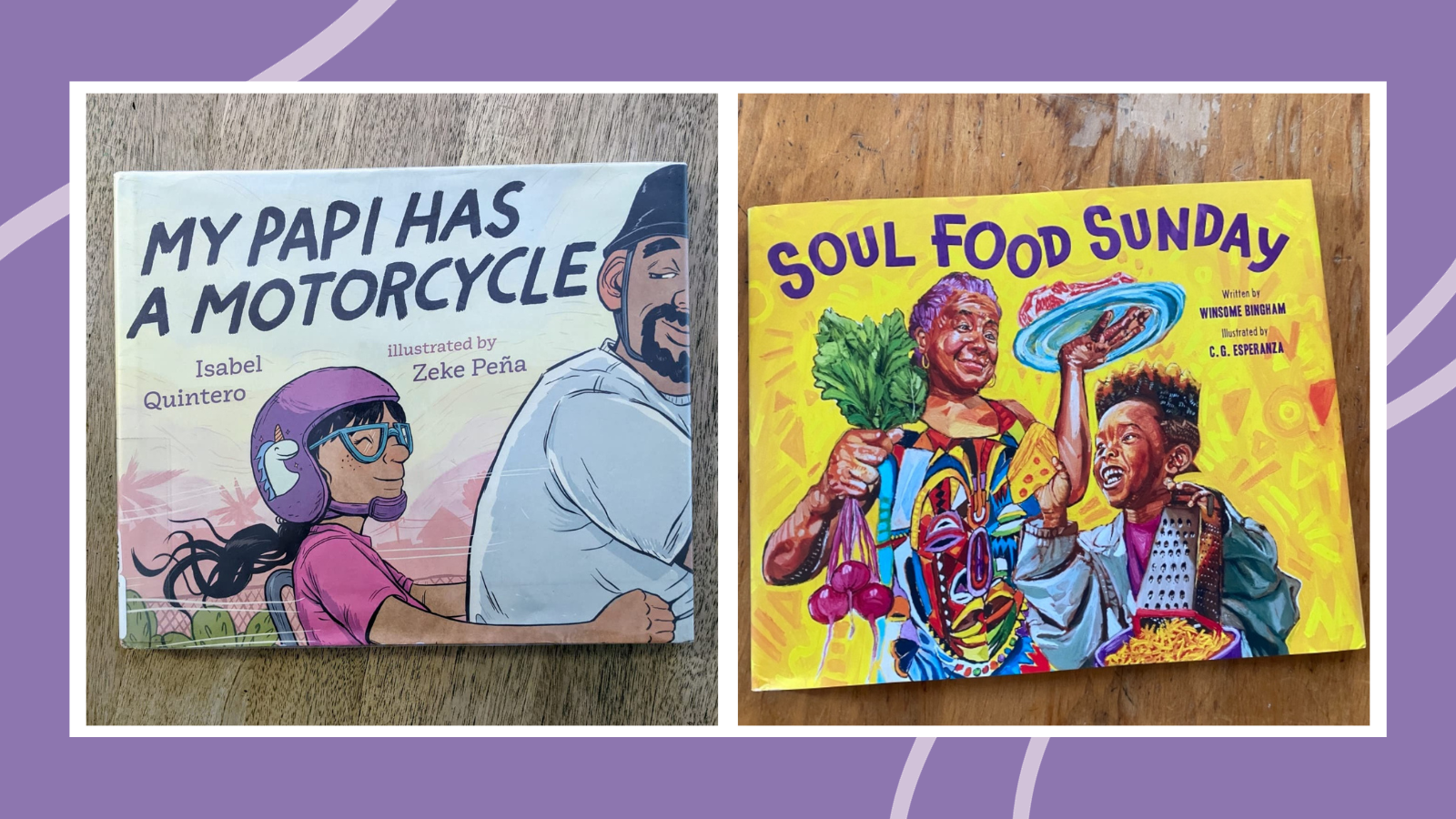

Step 4: Read Models

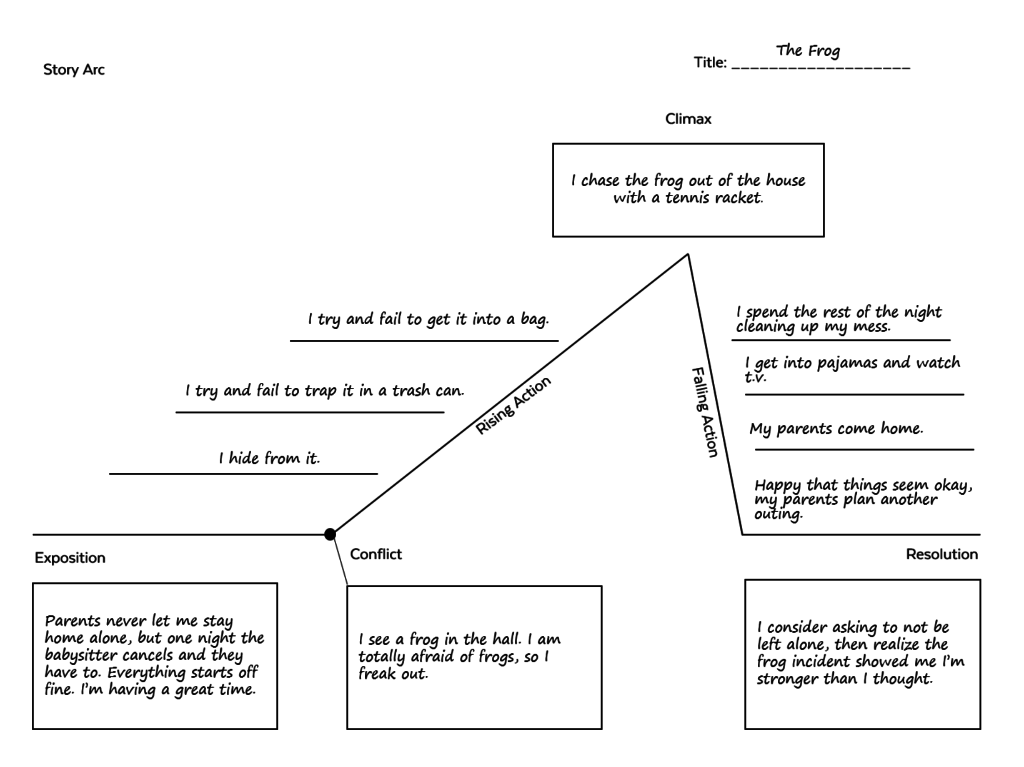

Once the parameters of the assignment have been explained, have students read at least one model story, a mentor text that exemplifies the qualities you’re looking for. This should be a story on a topic your students can kind of relate to, something they could see themselves writing. For my narrative writing unit (see the end of this post), I wrote a story called “Frog” about a 13-year-old girl who finally gets to stay home alone, then finds a frog in her house and gets completely freaked out, which basically ruins the fun she was planning for the night.

They will be reading this model as writers, looking at how the author shaped the text for a purpose, so that they can use those same strategies in their own writing. Have them look at your rubric and find places in the model that illustrate the qualities listed in the rubric. Then have them complete a story arc for the model so they can see the underlying structure.

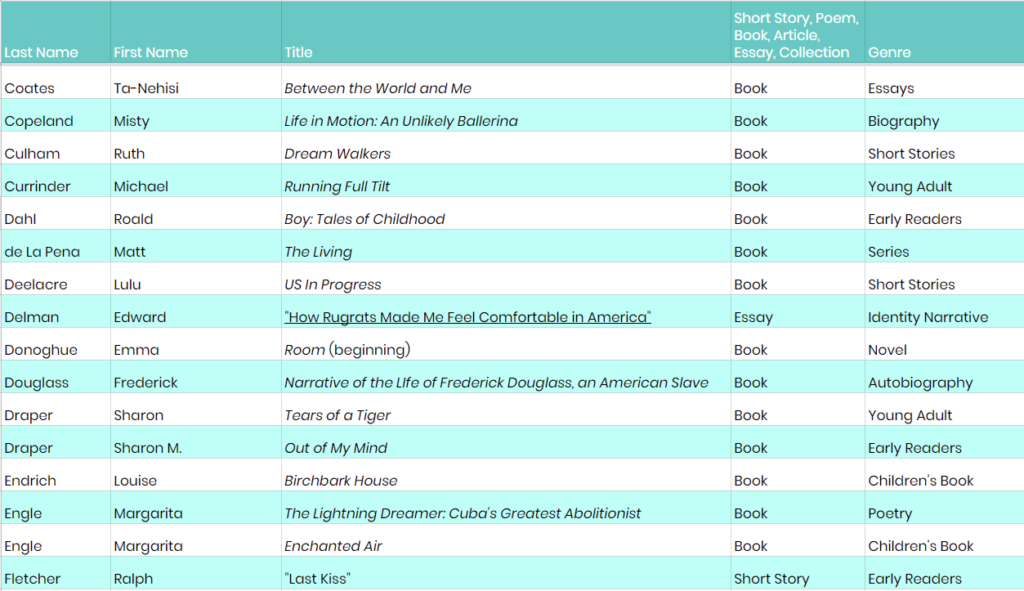

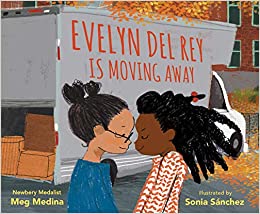

Ideally, your students will have already read lots of different stories to look to as models. If that isn’t the case, this list of narrative texts recommended by Cult of Pedagogy followers on Twitter would be a good place to browse for titles that might be right for your students. Keep in mind that we have not read most of these stories, so be sure to read them first before adopting them for classroom use.

Step 5: Story Mapping

At this point, students will need to decide what they are going to write about. If they are stuck for a topic, have them just pick something they can write about, even if it’s not the most captivating story in the world. A skilled writer could tell a great story about deciding what to have for lunch. If they are using the skills of narrative writing, the topic isn’t as important as the execution.

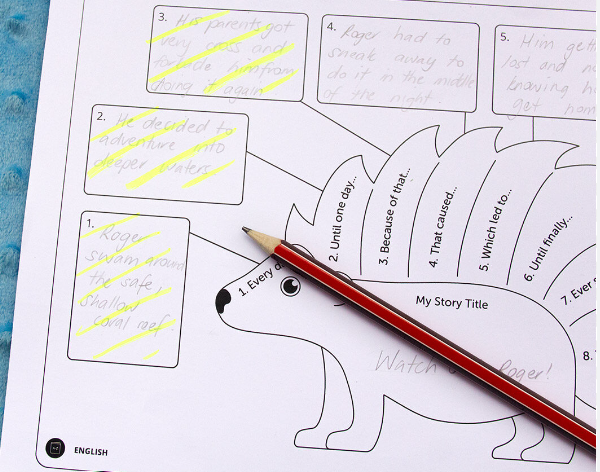

Have students complete a basic story arc for their chosen topic using a diagram like the one below. This will help them make sure that they actually have a story to tell, with an identifiable problem, a sequence of events that build to a climax, and some kind of resolution, where something is different by the end. Again, if you are writing with your students, this would be an important step to model for them with your own story-in-progress.

Step 6: Quick Drafts

Now, have students get their chosen story down on paper as quickly as possible: This could be basically a long paragraph that would read almost like a summary, but it would contain all the major parts of the story. Model this step with your own story, so they can see that you are not shooting for perfection in any way. What you want is a working draft, a starting point, something to build on for later, rather than a blank page (or screen) to stare at.

Step 7: Plan the Pacing

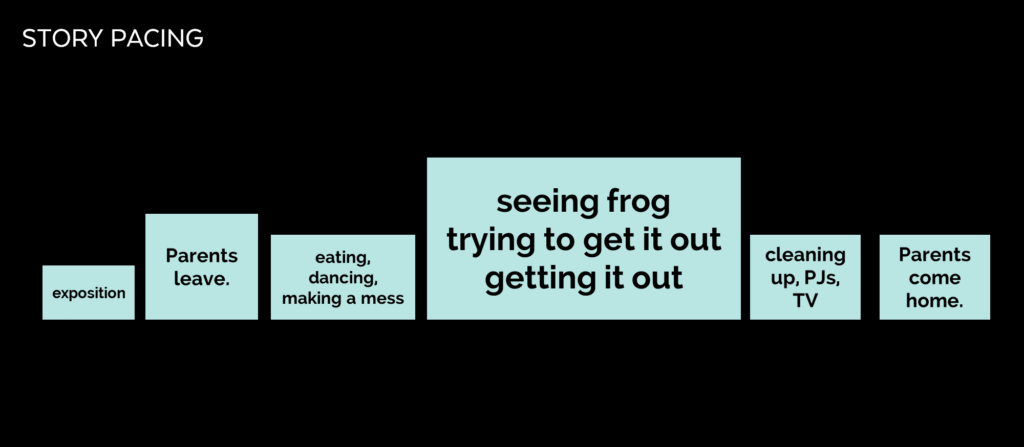

Now that the story has been born in raw form, students can begin to shape it. This would be a good time for a lesson on pacing, where students look at how writers expand some moments to create drama and shrink other moments so that the story doesn’t drag. Creating a diagram like the one below forces a writer to decide how much space to devote to all of the events in the story.

Step 8: Long Drafts

With a good plan in hand, students can now slow down and write a proper draft, expanding the sections of their story that they plan to really draw out and adding in more of the details that they left out in the quick draft.

Step 9: Workshop

Once students have a decent rough draft—something that has a basic beginning, middle, and end, with some discernible rising action, a climax of some kind, and a resolution, you’re ready to shift into full-on workshop mode. I would do this for at least a week: Start class with a short mini-lesson on some aspect of narrative writing craft, then give students the rest of the period to write, conference with you, and collaborate with their peers. During that time, they should focus some of their attention on applying the skill they learned in the mini-lesson to their drafts, so they will improve a little bit every day.

Topics for mini-lessons can include:

- How to weave exposition into your story so you don’t give readers an “information dump”

- How to carefully select dialogue to create good scenes, rather than quoting everything in a conversation

- How to punctuate and format dialogue so that it imitates the natural flow of a conversation

- How to describe things using sensory details and figurative language; also, what to describe…students too often give lots of irrelevant detail

- How to choose precise nouns and vivid verbs, use a variety of sentence lengths and structures, and add transitional words, phrases, and features to help the reader follow along

- How to start, end, and title a story

Step 10: Final Revisions and Edits

As the unit nears its end, students should be shifting away from revision , in which they alter the content of a piece, toward editing , where they make smaller changes to the mechanics of the writing. Make sure students understand the difference between the two: They should not be correcting each other’s spelling and punctuation in the early stages of this process, when the focus should be on shaping a better story.

One of the most effective strategies for revision and editing is to have students read their stories out loud. In the early stages, this will reveal places where information is missing or things get confusing. Later, more read-alouds will help them immediately find missing words, unintentional repetitions, and sentences that just “sound weird.” So get your students to read their work out loud frequently. It also helps to print stories on paper: For some reason, seeing the words in print helps us notice things we didn’t see on the screen.

To get the most from peer review, where students read and comment on each other’s work, more modeling from you is essential: Pull up a sample piece of writing and show students how to give specific feedback that helps, rather than simply writing “good detail” or “needs more detail,” the two comments I saw exchanged most often on students’ peer-reviewed papers.

Step 11: Final Copies and Publication

Once revision and peer review are done, students will hand in their final copies. If you don’t want to get stuck with 100-plus papers to grade, consider using Catlin Tucker’s station rotation model , which keeps all the grading in class. And when you do return stories with your own feedback, try using Kristy Louden’s delayed grade strategy , where students don’t see their final grade until they have read your written feedback.

Beyond the standard hand-in-for-a-grade, consider other ways to have students publish their stories. Here are some options:

- Stories could be published as individual pages on a collaborative website or blog.

- Students could create illustrated e-books out of their stories.

- Students could create a slideshow to accompany their stories and record them as digital storytelling videos. This could be done with a tool like Screencastify or Screencast-O-Matic .

So this is what worked for me. If you’ve struggled to get good stories from your students, try some or all of these techniques next time. I think you’ll find that all of your students have some pretty interesting stories to tell. Helping them tell their stories well is a gift that will serve them for many years after they leave your classroom. ♦

Want this unit ready-made?

If you’re a writing teacher in grades 7-12 and you’d like a classroom-ready unit like the one described above, including slideshow mini-lessons on 14 areas of narrative craft, a sample narrative piece, editable rubrics, and other supplemental materials to guide students through every stage of the process, take a look at my Narrative Writing unit . Just click on the image below and you’ll be taken to a page where you can read more and see a detailed preview of what’s included.

What to Read Next

Categories: Instruction , Podcast

Tags: English language arts , Grades 6-8 , Grades 9-12 , teaching strategies

52 Comments

Wow, this is a wonderful guide! If my English teachers had taught this way, I’m sure I would have enjoyed narrative writing instead of dreading it. I’ll be able to use many of these suggestions when writing my blog! BrP

Lst year I was so discouraged because the short stories looked like the quick drafts described in this article. I thought I had totally failed until I read this and realized I did not fai,l I just needed to complete the process. Thank you!

I feel like you jumped in my head and connected my thoughts. I appreciate the time you took to stop and look closely at form. I really believe that student-writers should see all dimensions of narrative writing and be able to live in whichever style and voice they want for their work.

Can’t thank you enough for this. So well curated that one can just follow it blindly and ace at teaching it. Thanks again!

Great post! I especially liked your comments about reminding kids about the power of storytelling. My favourite podcasts and posts from you are always about how to do things in the classroom and I appreciate the research you do.

On a side note, the ice breakers are really handy. My kids know each other really well (rural community), and can tune out pretty quickly if there is nothing new to learn about their peers, but they like the games (and can remember where we stopped last time weeks later). I’ve started changing them up with ‘life questions’, so the editable version is great!

I love writing with my students and loved this podcast! A fun extension to this narrative is to challenge students to write another story about the same event, but use the perspective of another “character” from the story. Books like Wonder (R.J. Palacio) and Wanderer (Sharon Creech) can model the concept for students.

Thank you for your great efforts to reveal the practical writing strategies in layered details. As English is not my first language, I need listen to your podcast and read the text repeatedly so to fully understand. It’s worthy of the time for some great post like yours. I love sharing so I send the link to my English practice group that it can benefit more. I hope I could be able to give you some feedback later on.

Thank you for helping me get to know better especially the techniques in writing narrative text. Im an English teacher for 5years but have little knowledge on writing. I hope you could feature techniques in writing news and fearute story. God bless and more power!

Thank you for this! I am very interested in teaching a unit on personal narrative and this was an extremely helpful breakdown. As a current student teacher I am still unsure how to approach breaking down the structures of different genres of writing in a way that is helpful for me students but not too restrictive. The story mapping tools you provided really allowed me to think about this in a new way. Writing is such a powerful way to experience the world and more than anything I want my students to realize its power. Stories are how we make sense of the world and as an English teacher I feel obligated to give my students access to this particular skill.

The power of story is unfathomable. There’s this NGO in India doing some great work in harnessing the power of storytelling and plots to brighten children’s lives and enlighten them with true knowledge. Check out Katha India here: http://bit.ly/KathaIndia

Thank you so much for this. I did not go to college to become a writing professor, but due to restructuring in my department, I indeed am! This is a wonderful guide that I will use when teaching the narrative essay. I wonder if you have a similar guide for other modes such as descriptive, process, argument, etc.?

Hey Melanie, Jenn does have another guide on writing! Check out A Step-by-Step Plan for Teaching Argumentative Writing .

Hi, I am also wondering if there is a similar guide for descriptive writing in particular?

Hey Melanie, unfortunately Jenn doesn’t currently have a guide for descriptive writing. She’s always working on projects though, so she may get around to writing a unit like this in the future. You can always check her Teachers Pay Teachers page for an up-to-date list of materials she has available. Thanks!

I want to write about the new character in my area

That’s great! Let us know if you need any supports during your writing process!

I absolutely adore this unit plan. I teach freshmen English at a low-income high school and wanted to find something to help my students find their voice. It is not often that I borrow material, but I borrowed and adapted all of it in the order that it is presented! It is cohesive, understandable, and fun. Thank you!!

So glad to hear this, Nicole!

Thanks sharing this post. My students often get confused between personal narratives and short stories. Whenever I ask them to write a short story, she share their own experiences and add a bit of fiction in it to make it interesting.

Thank you! My students have loved this so far. I do have a question as to where the “Frog” story mentioned in Step 4 is. I could really use it! Thanks again.

This is great to hear, Emily! In Step 4, Jenn mentions that she wrote the “Frog” story for her narrative writing unit . Just scroll down the bottom of the post and you’ll see a link to the unit.

I also cannot find the link to the short story “Frog”– any chance someone can send it or we can repost it?

This story was written for Jenn’s narrative writing unit. You can find a link to this unit in Step 4 or at the bottom of the article. Hope this helps.

I cannot find the frog story mentioned. Could you please send the link.? Thank you

Hi Michelle,

The Frog story was written for Jenn’s narrative writing unit. There’s a link to this unit in Step 4 and at the bottom of the article.

Debbie- thanks for you reply… but there is no link to the story in step 4 or at the bottom of the page….

Hey Shawn, the frog story is part of Jenn’s narrative writing unit, which is available on her Teachers Pay Teachers site. The link Debbie is referring to at the bottom of this post will take you to her narrative writing unit and you would have to purchase that to gain access to the frog story. I hope this clears things up.

Thank you so much for this resource! I’m a high school English teacher, and am currently teaching creative writing for the first time. I really do value your blog, podcast, and other resources, so I’m excited to use this unit. I’m a cyber school teacher, so clear, organized layout is important; and I spend a lot of time making sure my content is visually accessible for my students to process. Thanks for creating resources that are easy for us teachers to process and use.

Do you have a lesson for Informative writing?

Hey Cari, Jenn has another unit on argumentative writing , but doesn’t have one yet on informative writing. She may develop one in the future so check back in sometime.

I had the same question. Informational writing is so difficult to have a good strong unit in when you have so many different text structures to meet and need text-dependent writing tasks.

Creating an informational writing unit is still on Jenn’s long list of projects to get to, but in the meantime, if you haven’t already, check out When We All Teach Text Structures, Everyone Wins . It might help you out!

This is a great lesson! It would be helpful to see a finished draft of the frog narrative arc. Students’ greatest challenge is transferring their ideas from the planner to a full draft. To see a full sample of how this arc was transformed into a complete narrative draft would be a powerful learning tool.

Hi Stacey! Jenn goes into more depth with the “Frog” lesson in her narrative writing unit – this is where you can find a sample of what a completed story arc might look. Also included is a draft of the narrative. If interested in checking out the unit and seeing a preview, just scroll down to the bottom of the post and click on the image. Hope this helps!

Helped me learn for an entrance exam thanks very much

Is the narrative writing lesson you talk about in https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/narrative-writing/

Also doable for elementary students you think, and if to what levels?

Love your work, Sincerely, Zanyar

Hey Zanyar,

It’s possible the unit would work with 4th and 5th graders, but Jenn definitely wouldn’t recommend going any younger. The main reason for this is that some of the mini-lessons in the unit could be challenging for students who are still concrete thinkers. You’d likely need to do some adjusting and scaffolding which could extend the unit beyond the 3 weeks. Having said that, I taught 1st grade and found the steps of the writing process, as described in the post, to be very similar. Of course learning targets/standards were different, but the process itself can be applied to any grade level (modeling writing, using mentor texts to study how stories work, planning the structure of the story, drafting, elaborating, etc.) Hope this helps!

This has made my life so much easier. After teaching in different schools systems, from the American, to British to IB, one needs to identify the anchor standards and concepts, that are common between all these systems, to build well balanced thematic units. Just reading these steps gave me the guidance I needed to satisfy both the conceptual framework the schools ask for and the standards-based practice. Thank you Thank you.

Would this work for teaching a first grader about narrative writing? I am also looking for a great book to use as a model for narrative writing. Veggie Monster is being used by his teacher and he isn’t connecting with this book in the least bit, so it isn’t having a positive impact. My fear is he will associate this with writing and I don’t want a negative association connected to such a beautiful process and experience. Any suggestions would be helpful.

Thank you for any information you can provide!

Although I think the materials in the actual narrative writing unit are really too advanced for a first grader, the general process that’s described in the blog post can still work really well.

I’m sorry your child isn’t connecting with The Night of the Veggie Monster. Try to keep in mind that the main reason this is used as a mentor text is because it models how a small moment story can be told in a big way. It’s filled with all kinds of wonderful text features that impact the meaning of the story – dialogue, description, bold text, speech bubbles, changes in text size, ellipses, zoomed in images, text placement, text shape, etc. All of these things will become mini-lessons throughout the unit. But there are lots of other wonderful mentor texts that your child might enjoy. My suggestion for an early writer, is to look for a small moment text, similar in structure, that zooms in on a problem that a first grader can relate to. In addition to the mentor texts that I found in this article , you might also want to check out Knuffle Bunny, Kitten’s First Full Moon, When Sophie Gets Angry Really Really Angry, and Whistle for Willie. Hope this helps!

I saw this on Pinterest the other day while searching for examples of narritives units/lessons. I clicked on it because I always click on C.o.P stuff 🙂 And I wasn’t disapointed. I was intrigued by the connection of narratives to humanity–even if a student doesn’t identify as a writer, he/she certainly is human, right? I really liked this. THIS clicked with me.

A few days after I read the P.o.C post, I ventured on to YouTube for more ideas to help guide me with my 8th graders’ narrative writing this coming spring. And there was a TEDx video titled, “The Power of Personal Narrative” by J. Christan Jensen. I immediately remembered the line from the article above that associated storytelling with “power” and how it sets humans apart and if introduced and taught as such, it can be “extraordinary.”

I watched the video and to the suprise of my expectations, it was FANTASTIC. Between Jennifer’s post and the TEDx video ignited within me some major motivation and excitement to begin this unit.

Thanks for sharing this with us! So glad that Jenn’s post paired with another text gave you some motivation and excitement. I’ll be sure to pass this on to Jenn!

Thank you very much for this really helpful post! I really love the idea of helping our students understand that storytelling is powerful and then go on to teach them how to harness that power. That is the essence of teaching literature or writing at any level. However, I’m a little worried about telling students that whether a piece of writing is fact or fiction does not matter. It in fact matters a lot precisely because storytelling is powerful. Narratives can shape people’s views and get their emotions involved which would, in turn, motivate them to act on a certain matter, whether for good or for bad. A fictional narrative that is passed as factual could cause a lot of damage in the real world. I believe we should. I can see how helping students focus on writing the story rather than the truth of it all could help refine the needed skills without distractions. Nevertheless, would it not be prudent to teach our students to not just harness the power of storytelling but refrain from misusing it by pushing false narratives as factual? It is true that in reality, memoirs pass as factual while novels do as fictional while the opposite may be true for both cases. I am not too worried about novels passing as fictional. On the other hand, fictional narratives masquerading as factual are disconcerting and part of a phenomenon that needs to be fought against, not enhanced or condoned in education. This is especially true because memoirs are often used by powerful people to write/re-write history. I would really like to hear your opinion on this. Thanks a lot for a great post and a lot of helpful resources!

Thank you so much for this. Jenn and I had a chance to chat and we can see where you’re coming from. Jenn never meant to suggest that a person should pass off a piece of fictional writing as a true story. Good stories can be true, completely fictional, or based on a true story that’s mixed with some fiction – that part doesn’t really matter. However, what does matter is how a student labels their story. We think that could have been stated more clearly in the post , so Jenn decided to add a bit about this at the end of the 3rd paragraph in the section “A Note About Form: Personal Narrative or Short Story?” Thanks again for bringing this to our attention!

You have no idea how much your page has helped me in so many ways. I am currently in my teaching credential program and there are times that I feel lost due to a lack of experience in the classroom. I’m so glad I came across your page! Thank you for sharing!

Thanks so much for letting us know-this means a whole lot!

No, we’re sorry. Jenn actually gets this question fairly often. It’s something she considered doing at one point, but because she has so many other projects she’s working on, she’s just not gotten to it.

I couldn’t find the story

Hi, Duraiya. The “Frog” story is part of Jenn’s narrative writing unit, which is available on her Teachers Pay Teachers site. The link at the bottom of this post will take you to her narrative writing unit, which you can purchase to gain access to the story. I hope this helps!

I am using this step-by-step plan to help me teach personal narrative story writing. I wanted to show the Coca-Cola story, but the link says the video is not available. Do you have a new link or can you tell me the name of the story so I can find it?

Thank you for putting this together.

Hi Corri, sorry about that. The Coca-Cola commercial disappeared, so Jenn just updated the post with links to two videos with good stories. Hope this helps!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Writing Curriculum

Teach Narrative Writing With The New York Times

This teaching guide, part of our eight-unit writing curriculum, includes daily writing prompts, lessons based on selected mentor texts, and an invitation for students to participate in our 100-word personal narrative contest.

By The Learning Network

Stories can thrill, wound, delight, uplift and teach. Telling a story vividly and powerfully is a vital skill that is deeply valued across all cultures, past and present — and narrative writing is, of course, a key genre for literacy instruction at every level.

When your students think “New York Times,” they probably think of our 172-year history of award-winning journalism, and may not even realize that The Times today is full of personal narratives — on love and family , but also on how we relate to animals , live with disabilities or navigate anxiety . If you flip or scroll through sections of the paper, you’ll see that personal writing is everywhere, and often ranks among the most popular pieces The Times publishes each week.

At The Learning Network, we’ve been posting writing prompts every school day for over a decade now, and many of them invite personal narrative. Inspired by Times articles of all kinds, the prompts ask students to tell us about their passions and their regrets, their most embarrassing moments and their greatest achievements. Thousands of students around the world respond each month, and each week during the school year we call out our favorite responses .

In this unit we’re taking it a step further and turning our narrative-writing opportunities into a contest that invites students to tell their own stories. Below, you’ll find plenty of ideas and resources to get your students reading, writing and thinking about their own stories, including:

✔ New narrative-writing prompts every week.

✔ Daily opportunities for students to have an authentic audience for their writing via posting comments to our forums.

✔ Guided practice with mentor texts that include writing exercises.

✔ A clear, achievable end-product (our contest) modeled on real-world writing.

✔ The chance for students to have their work published in The New York Times.

Here’s how it works.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Teach Starter, part of Tes Teach Starter, part of Tes

Search everything in all resources

32 Tips for Teaching Narrative Writing

Written by Alison Smith

Teaching narrative writing and inspiring young writers can be easy. One of our most important jobs is to create a passionate writing culture in our classrooms.

In my experience, the majority of so-called reluctant writers are hesitant and disinclined to engage in writing tasks because they are fearful of getting it wrong. It is our job to take away the fear and to create a learning environment in which students feel confident to express themselves through writing in a variety of ways.

I’m going to share tips, tricks and teaching resources that will make your epic job so much easier and raise the standard of writing in your classroom.

Set Up a Writing Station

Take the fear out of writing and set up a free writing station. Provide your students with paper, blank comic strips , blank postcards, greeting cards , envelopes, pens, pencils, sticky notes or whatever else inspires your students to put pencil to paper.

Acknowledge and praise all writing as a masterpiece! Try to avoid correcting the spelling, punctuation and the grammar used in free writing tasks. Make time for your students to use the writing station. Avoid making it a fast finisher activity, as the students who need it most are likely to miss out!

Use a Writer’s Notebook

Encourage your students to keep a Writer’s Notebook to jot down new ideas for narrative writing. The wonderful Deb Sukarna has told us to…

Be wide awake! Notice events, people, objects in the world around you.

How to Set Up a Writer’s Notebook Daily Routine

Each student needs their own notebook. If you can, let them choose if they’d prefer a lined notebook, or a blank visual diary style book like we’ve used in our photos. Allow students to create a cover for their notebook, or you can provide them with this Writer’s Notebook Cover Page which they can decorate. Introduce the concept to your class, ensuring they understand the notebook will not be graded, but will instead be used daily as a place for them to play with ideas and words. This wonderful Writer’s Notebook Poem by Ralph Fletcher is great to stick in the front of their notebooks as a reminder of the book’s purpose. Provide students with Writer’s Notebook Writing Prompt Cards (these are optional) Dedicate at least 5 minutes every day to your students’ Writer’s Notebooks, providing specific activities (see suggestions below!) or allowing free writing time.

Create a Writer’s Prop Table

Picture a small table in your classroom, scattered with a collection of objects such as a key, a padlock, a candle, a map or a train ticket, and your imagination will be popping with ideas for a narrative. Before you know it, your students will be looking for objects to add to the collection and planting seeds for their next narrative.

Direct Instruction

Research shows that students need direct instruction that includes the I do (teacher modelling), we do ( guided practice) and you do (independent practice). Teaching narrative writing is no exception to this rule and it’s critical to include a balance of modelled, guided and independent writing.

A big part of direct teaching instruction is making the lesson objectives clear. Narrative writing is a complex task and so it is important to focus on one thing at a time and to make the success criteria clear. For example, if your lesson focus is narrative structure, don’t stress about the spelling.

Our unit plans follow this direct instruction model. They have been created with love and care to make your life easier and to help your students to experience success. Look no further than our Developing Narrative Writing Skills Unit Plan – Year 3 and Year 4 . This comprehensive unit includes 15 lessons that cover it all and is a must-have.

Slow Down and Break It Up!

For incredible writing outcomes, break down the main parts of a narrative text type. Spend a significant amount of time, (one or two weeks), on each structural element. Think of it as laying one brick at a time. Ask your students to write a complete narrative only when they have secure knowledge, understanding and experience of writing an orientation , complication , resolution and an ending .

[resource:9825][resource:891][resource:788][resource:24296]

A great way to teach the structure of narrative writing is to deconstruct a text by cutting it up and sticking it back together! Given that it’s not ideal to cut up books, we have created a sorting task to reinforce the structural features of a narrative text.

If you haven’t already, check out Seven Steps to Writing Success , for a brilliant approach to teaching narrative writing. The seven steps are:

- Plan for success

Sizzling Starts

- Tightening Tensions

- Dynamic Dialogue

- Show, Don’t Tell

- Ban the Boring

- Exciting Endings.

Do your students fall into the trap of writing orientations that begin with One day…, On Monday, Once upon a time…? If your mission is to change this, believe me when I say that students need to see it to believe it. Try showing the opening scene of a great movie to inspire your budding writers and to demonstrate that a sizzling start is critical to engaging the audience. The opening scene of INCREDIBLES 2 Movie Clip – Opening Scene (2018), which takes just four minutes to view, is a great example.

Read amazing story openings ! The more the better! I love the sizzling start to How to Bee by Bren MacDibble…

Today! It’s here! Bright and real and waiting. The knowing of it bursts into my head so big and sudden, like a crack of morning sun bursting through the gap at the top of the door…

Once you’ve given your students the opportunity to read, watch and experience the impact of amazing sizzling starts, show your students our Narrative Plot Structure Diagram to demonstrate how a great narrative often starts with action!

Need more? Download our Seven Sensational Story Starters PowerPoint . One of the most effective ways to begin a narrative is to create a ‘hook’ to capture the reader’s attention. This PowerPoint presentation includes seven sensational methods that your students can use to begin their stories in an exciting and interesting way.

Shared Writing

Shared writing is a crucial part of teaching narrative writing. This effective teaching strategy (whereby the teacher models writing while being given ideas and direction from the students), is ideal to use with the whole class or in a small group.

Try our Visual Writing Prompts Widget as a stimulus for shared writing. Each image comes with writing prompts ideas, Five Ws and One H questions and suggested activities.

Tips for leading shared writing sessions

- Focus your shared writing session on one or two elements of narrative writing. For example, focus on text structure, ideas, characters and setting or vocabulary.

- Keep it short. This will depend on the year level of your class. 10 -15 minutes is an awesome effort. As a general rule, as soon as you notice that your students are disengaged, call it a day, until tomorrow!

- Model how to write a narrative using a plan. In fact, model how to write a plan! Show your students the art of referring to the plan on a regular basis.

- Use Think, Pair, Share and Elbow Partners , to encourage ideas and discussion.

- Inspire your students and stimulate ideas through the use of visual prompts, props and feely bags.

- Make it fun and do it often.

For more useful ideas on how to use writing prompts in the classroom, don’t miss our blog 5 Ways to Spark Imagination in the Classroom Using Writing Prompts .

Are Your Students Struggling to Come Up With Ideas?

If it’s ideas that you are struggling with, we have created a Narrative Writing Visual Prompts Presentation that could be your new bestie. Students respond to beautifully illustrated visual prompts by answering a series of inference and prediction questions. The answers to these questions are then used to generate ideas for planning and writing a narrative.

Graphic Organisers and Check Lists

Do your students struggle to sequence their ideas and follow the text structure of a narrative? My guess is that they haven’t spent enough time on the planning stage.

Help your students to plan their narrative writing by using one of our Narrative Plot Structure Templates or another graphic organiser from our collection.

Encourage your students to monitor and assess their own success by asking them to complete a Narrative Writing Checklist . This is a simple, effective way to keep your students on track!

There are many different ways to teach narrative writing. It’s likely that your school has its own unique approach. Nevertheless, I hope some of these ideas and resources will take the pressure off as you guide your students to experience success with the art of narrative writing.

Whatever teaching strategies you choose to use, keep in mind that your major goal is to nurture a love of writing.

[resource:52218][resource:51552][resource:52454][resource:47925]

[resource:50874][resource:49715][resource:49242][resource:50215]

It would make my day to see a photo of your new writer’s prop table!

Use #teachstarter to share your photos on instagram..

30 Buzzing Facts About Bees to Excite Kids About Nature

Everyone benefits from the busyness of bees which is why these bee facts will help inspire your students to appreciate and protect them!

6 Inclusive Mother's Day and Father's Day Ideas for the Primary Classroom

Use these ideas to make Mother's Day gifts and Father's Day classroom celebrations more inclusive for your students.

70 Best Books for Year 1 to Add to Your Classroom Reading Corner

Wondering which books for year 1 you should add to your classroom reading corner? Look no further! We have a list of 70 that are teacher (and student) approved!

28 Fun Facts About Australia to Explore With Your Primary Students

Share these fun facts about Australia with your primary school students and explore our teacher team's tips to use the facts in your lesson plans.

12 Easy Halloween Drawings for Kids to Try in Your Classroom This Holiday

Explore easy Halloween drawings for kids that are perfect for the classroom. Take a peek at this teacher-created list for plenty of fresh ideas!

20 Fun Facts About Mars to Get Kids Excited About Your Space Lessons

Add these fun facts about Mars to your lesson plans — plus see our teacher team's favourite ways to use them in classroom activities.

Get more inspiration delivered to your inbox!

Sign up for a free membership and receive tips, news and resources directly to your email!

9 Tips for Teaching Narrative Writing in Secondary ELA

Narrative writing can be a struggle for many secondary students, making it a challenging genre to teach. After reading this post, you can say goodbye to hearing moans and groans and grading disjointed stories! Steal my favorite tips, strategies, and activities to make your next narrative writing unit more enjoyable for all.

While most people associate secondary ELA with writing essays, they often forget one of the vital writing genres—narrative writing.

With expository and persuasive writing often taking center stage in the secondary classroom, narrative writing can be a bit of a bumpy ride for students. Students might have the classic five-paragraph essay structure memorized, but crafting a compelling narrative is another story (pun 100% intended).

Successful narrative writing requires creativity, organization, and a deep understanding of storytelling elements. Many students find this challenging as they need help structuring their ideas, developing characters, and maintaining a cohesive plot.

But don’t fret; this post is all about equipping you with tried and true tips and engaging activities to help you guide students through this process with more ease and enjoyment for all.

Why Is Narrative Writing Challenging for Students?

Before delving into strategies, it’s essential to understand the common roadblocks students face with narrative writing. Often, students struggle with:

They struggle to get started and brainstorm any “good” ideas worth writing about. As a result, they feel overwhelmed by the task.

Organization

Crafting a well-structured narrative requires a clear beginning, middle, and end. Students may grapple with sequencing events logically.

Character Development

Bringing characters to life is a skill students often witness others do while reading. Students might find it challenging to create realistic and dynamic characters.

Plot Development

Maintaining a cohesive and captivating plot can be tricky for developing writers. Students might face difficulties effectively introducing conflict, building tension, and resolving the story.

Descriptive Language

Painting a vivid picture with words is a vital component of narrative writing. Some students may struggle with using figurative and descriptive language to create a compelling story.

The Writing Process

Many students view the writing process as a one-and-done task, especially when writing the same type of essay again and again. They may be reluctant to the revision and editing process.

Understanding what aspect(s) of narrative writing your students struggle with will help you tailor the rest of your narrative writing unit to their needs. Consider the tips and activities below to help you teach narrative writing with more ease, effectiveness, and enjoyment.

9 Tips for Teaching Narrative Writing

Follow these practical tips and teaching strategies to make narrative writing an engaging and rewarding classroom experience.

1. Ask the Right Questions

Encourage students to develop well-rounded narratives by guiding them through a series of thoughtful questions, such as:

- Who are the main characters?

- What is the central conflict or problem?

- When does the story take place?

- Where is the setting of the narrative?

- Why are these events happening?

- How do the characters navigate through challenges?

This “5ws + 1H” questioning technique not only helps students organize their thoughts and articulate their ideas more clearly. Additionally, it inspires critical thinking while guiding students through creating a well-rounded and comprehensive narrative.

2. Scaffold with Picture Books

Read picture books with your students to reinforce narrative elements in a fun and engaging way. After reading, engage students in discussions about how the author effectively used these elements and encourage them to apply similar techniques in their own writing. Take it one step further by having students complete a plot diagram for the narrative arc. This visual and interactive approach helps make the more abstract concepts of narrative writing, like character and conflict, feel more tangible.

3. Showcase Strong Mentor Texts

Selecting powerful mentor texts exposes students to the successful implementation of the narrative techniques you want them to emulate in their own writing. Therefore, strive to choose mentor texts where narrative elements are clear and accessible for your students. By studying these texts, students can learn firsthand from accomplished authors, honing their skills and gaining inspiration for their own narratives.

4. Utilize Short Stories

Speaking of strong mentor texts, I highly recommend utilizing short stories during your narrative writing unit. These condensed narratives provide students with examples of compelling narratives while giving them the opportunity to analyze structure, character development, and plot dynamics in a more digestible format. Students will benefit from this exposure before attempting to go off and write their own narrative piece.

5. Incorporate Pop Culture

Don’t be afraid to stray from written stories when looking for strong examples of narrative elements. Turn to pop culture and look for popular movie trailers, video clips, or TV episodes that can make these elements more relatable and engaging for students. This approach connects the writing process to their interests, sparking creativity and making the learning experience more enjoyable.

6. Teach Writing Skills

Sure, your students may have written plenty of essays in the past, but those writing foundations don’t necessarily translate over to narrative writing. Ensure a strong foundation by explicitly teaching writing skills relevant to narrative writing, including dialogue construction, figurative language, strong verbs, narrative hooks, and descriptive writing. While there are several skills you can cover, don’t feel the need to overload students with everything at once. Indeed, focus on a key element or two in each lesson and give them time to practice with a low-stakes activity.

7. Start with Story Mapping

Many students need help with two main components of narrative writing: developing a cohesive story and getting started writing it out. Story mapping kills both of those birds with one stone. Encourage students to map out their narratives before diving into writing. Use graphic organizers or storyboards to help them visualize the structure, characters, and key events, providing a narrative roadmap throughout the writing process.

8. Save Time for Revisions

Don’t forget to allocate dedicated class time for the crucial revision and editing process. While students may be used to taking a one-and-done approach with their essays, emphasize the importance of refining their narratives, checking for flow, and refining language to craft compelling plots that captivate readers. When you emphasize the importance of revision throughout the unit, students will learn that crafting an exceptional narrative often involves multiple iterations and improvements.

9. Have Fun!

Lastly, let’s not forget that storytelling can be fun ! Use this as an opportunity to encourage creativity and alleviate the potential stress (and dread) associated with writing. When students find joy in the process, they are more likely to invest themselves fully in crafting compelling narratives, and that, my friend, is a win for you and them.

Give These 5 Engaging Activities a Try

The following activities are perfect for tackling the aspects of narrative writing students struggle with most in an effective way. Not only will they make narrative writing more engaging but will also deepen students’ understanding of vital storytelling elements.

1. Writing Stations

Set up different interactive writing stations with specific tasks related to narrative elements such as character development, setting description, dialogue construction, and conflict resolution. Students can rotate through these stations, working on each aspect of their narrative at a time. This approach not only breaks down the writing process into manageable chunks but also caters to diverse learning styles, keeping students actively engaged in the creative process.

2. Classroom Conflict Brainstorm

After reviewing the different types of conflict, work as a class to create one-line story summaries of potential plots for each conflict type. Save this list and allow students to pull from it when they write a narrative! This activity not only sparks creativity and initiates brainstorming but also emphasizes the importance of conflict as a driving force in storytelling. Classic conflict types include:

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

3. The Story Behind the Photo

They say a picture is worth a thousand words and this activity asks your students to physically write them down. The best part? It requires very little prep on your part. Simply distribute random photographs around the room (Google images will work just fine). Then, challenge students to craft a narrative inspired by the image. Ask them to think about the story behind the photograph. What happened right before the picture was taken? Right after? What is occurring outside of the frame? This activity engages students in creative narrative expiration by providing a visual cue to initiate the brainstorming.

4. Can You Feel It? Writing Challenge

Challenge students to focus on conveying a specific emotion within a short scene. Give students an emotion or tone, such as happiness, sorrow, fear, or suspense. Then, give them a setting, such as a train station, birthday party, or park. Challenge students to take those two pieces of information and craft a scene to evoke an emotional response from the reader. Give them the opportunity to share their pieces aloud to gauge audience response!

5. Rewrite an Existing Scene in Dialogue

Writing purposeful and engaging dialogue doesn’t always come naturally to students. That’s where this activity comes into play. Select a scene from a well-known story or have students bring in their favorite passages. Then, challenge them to rewrite the scene entirely (or at least, mostly ) in dialogue form, focusing on maintaining the essence of the narrative prose. Remind them of the importance of strong verbs and engaging and descriptive dialogue tags. This activity sharpens dialogue-writing skills and encourages students to consider how characters express themselves through speech and how dialogue influences the pacing of a narrative.

Looking for strong examples of dialogue? Check out these short stories.

It’s Teaching Time!

If you’ve struggled to get your students to engage in the narrative writing process and produce strong stories in the past, I promise you are not alone. Navigating the challenges of narrative writing in secondary ELA is not easy to do on the fly. Instead, it requires a combination of strategic teaching and engaging activities. Once you nail that combo down, you will be on your way to unlocking next-level storytelling skills for your students.

Once you understand what areas your students struggle with in narrative writing, you can plan effective and engaging lessons that bring this genre to life. And who knows, you may be on your way to inspiring one of this generation’s next greatest storytellers! At the very least, you will provide a foundational understanding and foster an appreciation of what makes a story one worth telling.

For a step-by-step guide to teaching narrative writing, read this.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

Teaching Narrative Writing: 14 Activities to Help Your Students Learn to Love It

Teaching narrative writing can ignite a student’s imagination and nurture a love for storytelling. It is a craft that not only improves writing skills but also enhances cognitive and emotional development. Here are 14 imaginative activities to invigorate your students’ interest and proficiency in narrative writing:

1. Story Starters: Provide intriguing first sentences or paragraphs to kick off a story and let students’ creativity flow.

2. Character Creation: Encourage students to develop detailed profiles for their characters, including backstories and personality traits.

3. Setting the Scene: Have students create vivid settings using sensory details that transport their readers into the story.

4. Show, Don’t Tell: Teach students to express emotions and actions through descriptive writing rather than direct statements.

5. Dialogue Workshops: Practice writing dialogues that reveal character and move the plot forward without overtly stating facts.

6. Plot Twisting: Offer plot points on cards, have students pick randomly, and incorporate them into their stories to create unexpected turns.

7. Perspective Shifts: Challenge students to rewrite their stories from another character’s point of view.

8. Visual Inspiration: Use photographs or artwork to prompt story ideas, focusing on creating narratives that align with the visual elements.

9. Mapping the Plot: Help students visually plan their story arcs with plot diagrams mapping out exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

10. Peer Review Circles: Organize peer editing sessions where students give constructive feedback about each other’s narratives.

11. Incorporating Vocabulary: Provide a list of new words each week that students must include in their writing, expanding their linguistic arsenal.

12. Tech Integration: Use digital storytelling tools like blogging or e-book creation software to engage tech-savvy writers.

13. Writing Prompts Jar: Fill a jar with random writing prompts for quick inspiration during free writing sessions.

14. Role-Playing Recesses: Have students act out scenes from their narratives, which can inform their understanding of character motivation and dialogue rhythm.

By integrating these engaging activities into your lesson plans, you’re certain to witness an increase in your students’ enthusiasm for narrative writing while honing their storytelling abilities.

Related Articles

The art of informative writing is a fundamental component of educational curriculum…

As parents, educators, and mentors, it’s essential to introduce children to the…

Editing can often be the less glamorous side of writing for students,…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Teach Narrative Writing

Last Updated: July 6, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 32,192 times.

Narrative writing is fun to teach, but it can also be a challenge! Whether you need to teach college or grade school students, there are lots of great options for lessons. Start by getting your students familiar with the genre, then use in-class activities to help them practice creating their own narratives. Once your students understand how narratives work, assign a narrative essay for students to demonstrate and hone their skills.

Introducing the Genre

- A specific point-of-view on the events of the story

- Vivid details that incorporate all 5 senses (sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste)

- A reflection on what the experience meant

- Have your students read narrative essays, such as "My Indian Education" by Sherman Alexie, "Shooting an Elephant" by George Orwell, "Learning to Read" by Malcolm X, or "Fish Cheeks" by Amy Tan.

- Show your students a movie, such as Moana or Frozen and then plot out the structure of the story with your students.

- Have your students listen to a podcast or radio segment that features a short narrative, such as the Modern Love podcast or NPR's "This I Believe" series.

If you want to show a film but you are short on time, show a short film or sketch comedy clip , such as something from a channel you like on Youtube. Choose something that will grab your students' attention!

- Who are the characters in this story? What are they like? How can you tell?

- Who is telling the story?

- What happens to the characters?

- How do they work towards a solution to the problem?

- Where and when does the story take place?

- What is the mood of the story?

- For example, start by looking at the action and characters in the introduction. How does the author introduce the story? The characters?

- Then, move to the body paragraphs to identify how the story develops. What happens? Who does it happen to? How do the characters respond?

- Finish your map by looking at the conclusion to the story. How is the conflict resolved? What effect does this resolution have on the characters in the story?

Using In-Class Activities

- For example, you might start the story by saying “Once,” which another student might follow with “upon,” another with “a,” and another with “time,” and so on.

- You might also give the story more structure by giving your students a model to follow. For example, you might require them to follow a format, such as this one: "The-adjective-noun-adverb-verb-the-adjective-noun." Post the format where all of the students can follow along as they tell their story.

- To build a story sentence by sentence, you might start with “Once upon a time, there was a princess named Jezebel.” And then the next student might add, “She was betrothed to a foreign prince, but she did not want to get married.” And another might add, “One her wedding day, she fled the country.”

- Allow each student about 7 to 10 minutes to write their paragraph.

- Return the stories to the student who wrote the opening paragraph so they can see how other people continued their story.

- Ask students to share how their story progressed after they passed it to their neighbor.

- For example, if the author of a story writes, “Sally was so angry,” then they are telling. However, the author would be showing by writing, “Sally slammed the car door shut and stomped off towards her house. Before she went inside, she turned, shot me a furious look, and shouted, 'I never want to see you again!'”

- The first example tells readers that Sally is angry, while the second example shows readers that Sally is angry using her actions and words.

- A great way to practice this concept is to give students a plot point or have them create their own. Then, have the students work on showing the plot point using only dialogue.

- What does the character look like? Hair/eye/skin color? Height/weight/age? Clothing? Other distinguishing features?

- What mannerisms does the person have? Any nervous ticks? How does their voice sound?

- What is their personality like? Is the person an optimist or pessimist?

- What are their likes/dislikes? Hobbies? Profession?

- The diner was empty, except for me, the waitress, the cook, and a lone gunman.

- I was lost in a strange city with no money, no phone, and no way to contact anyone.

- The creature disappeared as suddenly and unexpectedly as it had arrived.

- Invite students to share what happened on their islands at the end of the 5 days.

- Display the island drawings and descriptions on the wall of your classroom.

Make it your goal to do 1 activity in class each day ! This will help to ensure that your students are getting lots of exposure to what a narrative is and how it works before they write their own narratives.

Assigning a Narrative Essay

- Tell your students if you are using a theme or focus. For example, if you want students to write their narrative on an experience with reading or writing, then you might provide examples, such as the first novel they read and fell in love with, or the time they had to totally rewrite a paper for an English class.

- Also, include details in the rubric on the required length of the essay, special features you expect to see, and any formatting requirements.

- Make sure to provide students with feedback on their pre-write activities. Encourage them on what sounds like it has the most potential and steer them away from topics that seem too broad or that would not hold up well as narratives.

- For example, if a student submits a freewrite in which they discuss wanting to write about all of the English teachers they have ever had, this would be too broad and you would want to encourage them to narrow their topic, such as by writing about 1 teacher only.

- For example, if the paper is due on April 1st, then students ought to start drafting at least 1 week in advance, or sooner if possible. This will help to ensure that they will have plenty of time to revise their work.

- Does the story seem complete? What else could be added?

- Is the topic too narrow or too broad? Does the paper maintain its focus or is it disorganized?

- Are the introduction and conclusion effective? How might they be improved?

For a creative way to showcase your students' stories, have them to transform their essays into a different format and share it with the class! For example, your students could turn their essay into a podcast, short film, or drawing.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/narrative_essays.html

- ↑ https://www.edutopia.org/article/systematic-approach-teaching-narrative-writing/

- ↑ https://intensiveintervention.org/sites/default/files/Narrative-Text-Structures-508.pdf

- ↑ https://lewisu.edu/writingcenter/pdf/narrative-elements-1.pdf

- ↑ https://cdn.ncte.org/nctefiles/resources/books/sample/00465chap07.pdf

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/narrative-writing/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

About this article

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

How to Master Narrative Writing in a Single Week

Mastering narrative writing in one week is a big ask. A very BIG ask! But you can teach the core elements of how to craft a well-told tale in this tight timeframe. Mastery will come through diligent practice on the part of the student and thoughtful feedback on the teacher’s part.

How do you teach students narratives?

In this article, we’ll take a look at how you can take your students from zero to hero, in narrative writing terms, in just one lesson per day during the school week and a little extra effort over the weekend.

Come the following Monday morning, and your desk should be positively heaving under the weight of your students’ freshly composed masterpieces.

Though we’re in the game of narrative fiction here, let’s try to bring our aspirations into the realm of the possible. We won’t get a novel out of our students in a mere seven days, not without working their fingers and to the bone. However, the short story format will perfectly serve our ambitions.

So, let’s get started by exploring these five narrative lesson plans – By Zeus’s breath! We’ve still set ourselves a task of Herculean proportions!

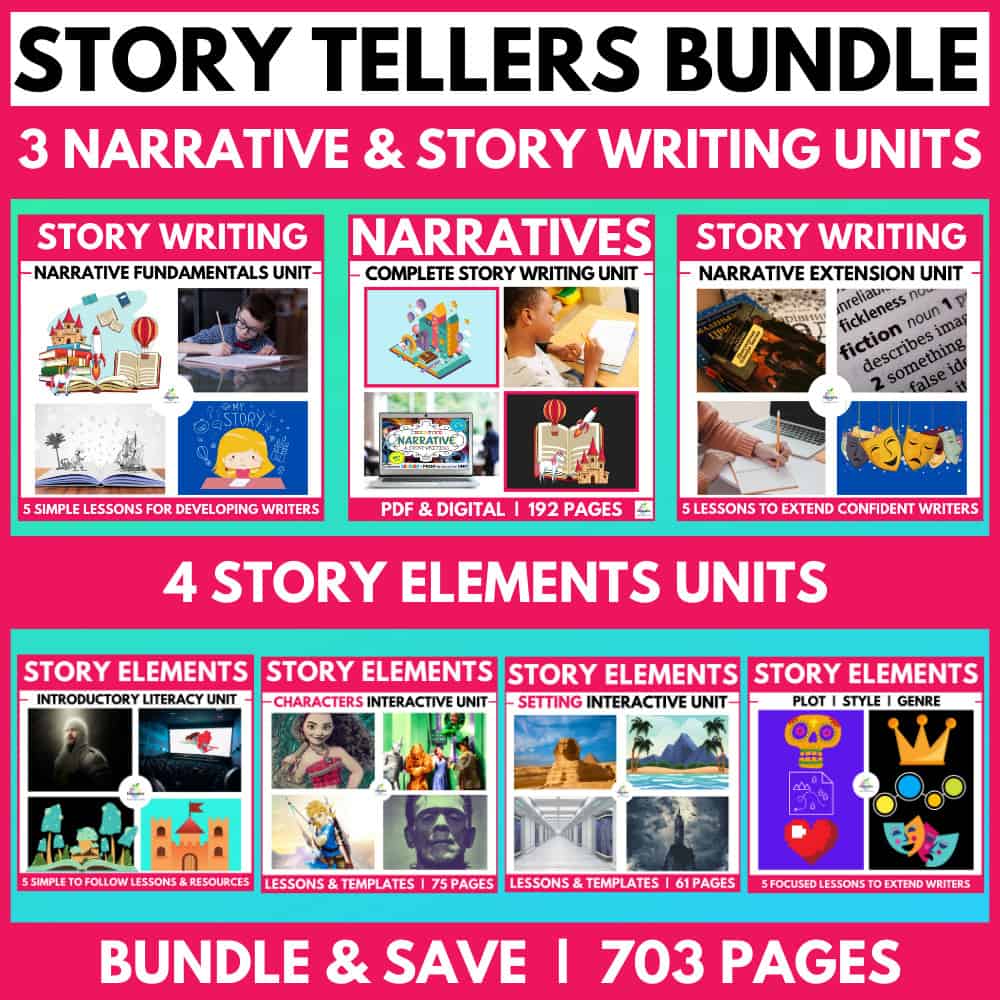

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

Lesson 1: Generate One Good Story Idea

There’s a lot of ground to cover, so you’ll need to get your students off to an energetic start if they’re to reach the finish line of a completed story by the end of the week.

They’ll need to come up with an idea for a story so engaging that they’ll be chomping at the bit to get their pens galloping over the page.

Try one of these two activities to kickstart your students’ creativity:

- Spin Story Gold from Your Spam

Open up your email and go into your Spam folder. This is a repository of some of the highest-flying fiction in the modern age. It’s peopled with fanciful characters from far-flung lands such as generous princes, dying businessmen searching for heirs, devious diplomats, not to mention desperate widows.

Cut and paste a few of these that are student-suitable, print them, and distribute the results to your class.

If your students can’t make a story from this raw material, you may already have a lost cause on your hands!

- What Ever Happened to So-and-So?

We’ve all had friends and acquaintances we’ve lost touch with over the years. This is true of our students too – young as they are!

Ask your students to think of someone they used to know. Maybe a classmate from kindergarten who went on to a different school, or a neighbor who moved to another city. Anyone they used to know, but since they have since lost contact with will do.

Now, ask them to imagine what happened to this person. What twists and turns have their life taken since you last saw them? Have they fallen into a life of crime or been abducted by aliens? Maybe they moved to a distant, exotic country and have started life anew. Encourage your students to let their imaginations run wild!

And, needless to say, have your students change their names to protect the innocent!

Once the students have come up with their rough story idea , it’s time to nail down some things in more detail and decide on a few crucial elements of their story.

Students must decide who the characters in their story are and what point of view they will tell the story. Will it be told from the first person POV, from the main character’s perspective, or from the omniscient third-person viewpoint? Can students sketch quick character bios to help them later in writing?

How about the setting? Where does the action take place? Will the story be static, or will locations change throughout the story?

Decisions, decisions!

The more questions students generate and answer, the easier tomorrow will be.

Failing all of that, if you need some creative juice, be sure to check out our writing prompts here .

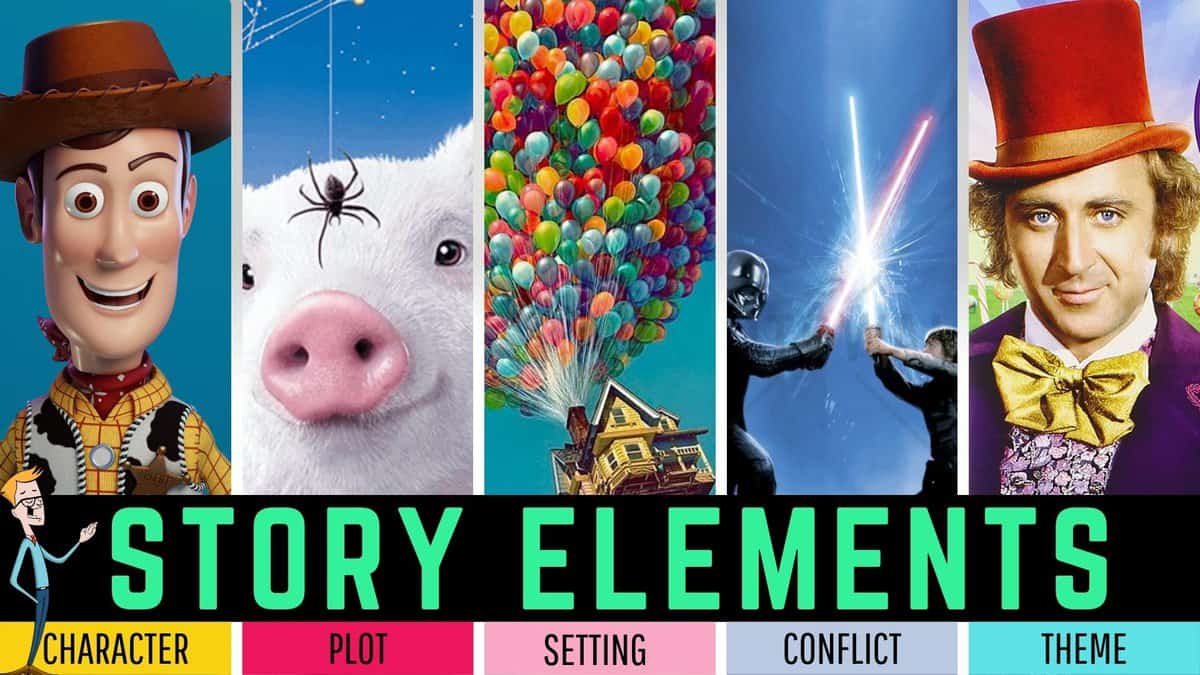

STORY ELEMENTS FOR KIDS TUTORIAL VIDEO

Lesson 2: Outline

Day 2, and it’s time for students to outline their story. You can help this process significantly by giving your students a clear structure to follow. Graphic organizers offer an efficient way to lay things out easily to follow manner, helping students get their story written in an organized fashion.

But, whether they use graphic organizers or sketch their outline by hand, their story outline should contain the following elements (or similar variations):

● Exposition – include characters & setting details from yesterday.

● Conflict – this will usually emerge from the initial story idea.

● Rising Action – a related series of events that escalates the story’s drama

● Climax – the dramatic highpoint where the conflict comes to a head

● Falling Action – the dramatic tension of the story decreases, and things move toward the conclusion.

● Resolution – loose ends are tied up, and the story draws to a close.

Sometimes it can be beneficial to allow students to form small discussion groups to offer each other feedback and constructive criticism on their ideas.

Remind students that the more detail they go into in their outlines, the easier writing their stories will be.

Lesson: 3: Write the First Act

By now, your students have laid all the necessary groundwork, and the writing begins in earnest.

From our early school days, everyone knows that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. This is the basic three-act story structure, a structure that is ideal for your students to follow when writing their short stories .

The purpose of today’s lesson will be for your students to complete the first act of their story. A well-written first act will provide great momentum to help the students through the remaining two acts.

In the first act, students should aim to:

● Introduce the important characters

● Establish the setting and tone of their story

● Reveal the story’s central conflict

● Begin the process of ramping up the drama through the rising action.

If the purpose of the first act is to grab the reader’s attention so that they simply have to read to the end, then your students will need to employ a hook right from the first scene of their tale.

The purpose of this hook is to intrigue the reader and entice them to continue reading. But, not only does the hook need to gain the reader’s interest, it needs to serve the needs of the plot too.

A well-used hook should:

● Introduce the main character

● Give an insight into that character’s daily life

● Show them dealing with some problem or conflict to reveal their character

Showing the main character in action dealing with a problem or conflict begins the story’s movement forward – even if the problem is minor.

Moving on from the hook, your students must work to keep the reader engaged throughout the story. There are two main ways to do this, either make the characters interesting or make the events compelling.

And, of course, there is a third option – do both!

The Inciting Incident

The inciting incident is the event that sets the ball rolling in terms of the story’s action. Often, this is when something happens to flip the main character’s world upside-down or begin a process that causes the pattern of their daily life to be altered significantly, often forever.

Here are two common options to help students create an inciting incident:

● The Deliberate Choice – Here, the main character makes a decision or a choice that sets all in motion the rest of the events of the story.

● The Coincidence – The merging of time, place, and characters. Think ‘right person in the right place at the right time.’ You could, of course, substitute ‘wrong’ for ‘right’ here!

From here on out, a sequence of events unfolds, leading us into and through Act 2…

Lesson 4: Write Right to the End

By finishing the first act of their story, your students have pushed the ball to the top of the hill. All that remains is to tip it over the other side and let it roll all the way to the end.

Act 2 will see the dramatic tension build over a series of cause-and-effect events. This is very important for students to grasp. While writing about fictional characters in a fictional world, their stories must still contain a sense of logical consistency or they will frustrate their readers.