Synthesis Essays: A Step-by-Step How-To Guide

A synthesis essay is generally a short essay which brings two or more sources (or perspectives) into conversation with each other.

The word “synthesis” confuses every student a little bit. Fortunately, this step-by-step how-to guide will see you through to success!

Here’s a step-by-step how-to guide, with examples, that will help you write yours.

Before drafting your essay:

After reading the sources and before writing your essay, ask yourself these questions:

- What is the debate or issue that concerns all of the writers? In other words, what is the question they are trying to answer?

- On what points do they agree?

- On what points do they disagree?

- If they were having a verbal discussion, how would writer number one respond to the arguments of writer number two?

In a way, writing a synthesis essay is similar to composing a summary. But a synthesis essay requires you to read more than one source and to identify the way the writers’ ideas and points of view are related.

Sometimes several sources will reach the same conclusion even though each source approaches the subject from a different point of view.

Other times, sources will discuss the same aspects of the problem/issue/debate but will reach different conclusions.

And sometimes, sources will simply repeat ideas you have read in other sources; however, this is unlikely in a high school or AP situation.

To better organize your thoughts about what you’ve read, do this:

- Identify each writer’s thesis/claim/main idea

- List the writers supporting ideas (think topic sentences or substantiating ideas)

- List the types of support used by the writers that seem important. For example, if the writer uses a lot of statistics to support a claim, note this. If a writer uses historical facts, note this.

There’s one more thing to do before writing: You need to articulate for yourself the relationships and connections among these ideas.

Sometimes the relationships are easy to find. For example, after reading several articles about censorship in newspapers, you may notice that most of the writers refer to or in some way use the First Amendment to help support their arguments and help persuade readers. In this case, you would want to describe the different ways the writers use the First Amendment in their arguments. To do this, ask yourself, “How does this writer exploit the value of the First Amendment/use the First Amendment to help persuade or manipulate the readers into thinking that she is right?

Sometimes articulating the relationships between ideas is not as easy. If you have trouble articulating clear relationships among the shared ideas you have noted, ask yourself these questions:

- Do the ideas of one writer support the ideas of another? If so, how?

- Do the writers who reach the same conclusion use the same ideas in their writing? If not, is there a different persuasive value to the ideas used by one writer than by the other?

- Do the writers who disagree discuss similar points or did they approach the subject from a completely different angle and therefore use different points and different kinds of evidence to support their arguments?

- Review your list of ideas. Are any of the ideas you have listed actually the same idea, just written in different words?

- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

In philosophy, the triad of thesis, antithesis, synthesis (German: These, Antithese, Synthese; originally: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis) is a progression of three ideas or propositions. The first idea, the thesis, is a formal statement illustrating a point; it is followed by the second idea, the antithesis, that contradicts or negates the first; and lastly, the third idea, the synthesis, resolves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis. It is often used to explain the dialectical method of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, but Hegel never used the terms himself; instead his triad was concrete, abstract, absolute. The thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad actually originated with Johann Fichte.

1. History of the Idea

Thomas McFarland (2002), in his Prolegomena to Coleridge's Opus Maximum , [ 1 ] identifies Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) as the genesis of the thesis/antithesis dyad. Kant concretises his ideas into:

- Thesis: "The world has a beginning in time, and is limited with regard to space."

- Antithesis: "The world has no beginning and no limits in space, but is infinite, in respect to both time and space."

Inasmuch as conjectures like these can be said to be resolvable, Fichte's Grundlage der gesamten Wissenschaftslehre ( Foundations of the Science of Knowledge , 1794) resolved Kant's dyad by synthesis, posing the question thus: [ 1 ]

- No synthesis is possible without a preceding antithesis. As little as antithesis without synthesis, or synthesis without antithesis, is possible; just as little possible are both without thesis.

Fichte employed the triadic idea "thesis–antithesis–synthesis" as a formula for the explanation of change. [ 2 ] Fichte was the first to use the trilogy of words together, [ 3 ] in his Grundriss des Eigentümlichen der Wissenschaftslehre, in Rücksicht auf das theoretische Vermögen (1795, Outline of the Distinctive Character of the Wissenschaftslehre with respect to the Theoretical Faculty ): "Die jetzt aufgezeigte Handlung ist thetisch, antithetisch und synthetisch zugleich." ["The action here described is simultaneously thetic, antithetic, and synthetic." [ 4 ] ]

Still according to McFarland, Schelling then, in his Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie (1795), arranged the terms schematically in pyramidal form.

According to Walter Kaufmann (1966), although the triad is often thought to form part of an analysis of historical and philosophical progress called the Hegelian dialectic, the assumption is erroneous: [ 5 ]

Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel's Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. ... But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge.

Gustav E. Mueller (1958) concurs that Hegel was not a proponent of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and clarifies what the concept of dialectic might have meant in Hegel's thought. [ 6 ]

"Dialectic" does not for Hegel mean "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." Dialectic means that any "ism" – which has a polar opposite, or is a special viewpoint leaving "the rest" to itself – must be criticized by the logic of philosophical thought, whose problem is reality as such, the "World-itself".

According to Mueller, the attribution of this tripartite dialectic to Hegel is the result of "inept reading" and simplistic translations which do not take into account the genesis of Hegel's terms:

Hegel's greatness is as indisputable as his obscurity. The matter is due to his peculiar terminology and style; they are undoubtedly involved and complicated, and seem excessively abstract. These linguistic troubles, in turn, have given rise to legends which are like perverse and magic spectacles – once you wear them, the text simply vanishes. Theodor Haering's monumental and standard work has for the first time cleared up the linguistic problem. By carefully analyzing every sentence from his early writings, which were published only in this century, he has shown how Hegel's terminology evolved – though it was complete when he began to publish. Hegel's contemporaries were immediately baffled, because what was clear to him was not clear to his readers, who were not initiated into the genesis of his terms. An example of how a legend can grow on inept reading is this: Translate "Begriff" by "concept," "Vernunft" by "reason" and "Wissenschaft" by "science" – and they are all good dictionary translations – and you have transformed the great critic of rationalism and irrationalism into a ridiculous champion of an absurd pan-logistic rationalism and scientism. The most vexing and devastating Hegel legend is that everything is thought in "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." [ 7 ]

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) adopted and extended the triad, especially in Marx's The Poverty of Philosophy (1847). Here, in Chapter 2, Marx is obsessed by the word "thesis"; [ 8 ] it forms an important part of the basis for the Marxist theory of history. [ 9 ]

2. Writing Pedagogy

In modern times, the dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis has been implemented across the world as a strategy for organizing expositional writing. For example, this technique is taught as a basic organizing principle in French schools: [ 10 ]

The French learn to value and practice eloquence from a young age. Almost from day one, students are taught to produce plans for their compositions, and are graded on them. The structures change with fashions. Youngsters were once taught to express a progression of ideas. Now they follow a dialectic model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. If you listen carefully to the French arguing about any topic they all follow this model closely: they present an idea, explain possible objections to it, and then sum up their conclusions. ... This analytical mode of reasoning is integrated into the entire school corpus.

Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis has also been used as a basic scheme to organize writing in the English language. For example, the website WikiPreMed.com advocates the use of this scheme in writing timed essays for the MCAT standardized test: [ 11 ]

For the purposes of writing MCAT essays, the dialectic describes the progression of ideas in a critical thought process that is the force driving your argument. A good dialectical progression propels your arguments in a way that is satisfying to the reader. The thesis is an intellectual proposition. The antithesis is a critical perspective on the thesis. The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths, and forming a new proposition.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Opus Maximum. Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 89.

- Harry Ritter, Dictionary of Concepts in History. Greenwood Publishing Group (1986), p.114

- Williams, Robert R. (1992). Recognition: Fichte and Hegel on the Other. SUNY Press. p. 46, note 37.

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb; Breazeale, Daniel (1993). Fichte: Early Philosophical Writings. Cornell University Press. p. 249.

- Walter Kaufmann (1966). "§ 37". Hegel: A Reinterpretation. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-268-01068-3. OCLC 3168016. https://archive.org/details/hegelreinterpret00kauf.

- Mueller, Gustav (1958). "The Hegel Legend of "Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis"". Journal of the History of Ideas 19 (4): 411–414. doi:10.2307/2708045. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2708045

- Mueller 1958, p. 411.

- marxists.org: Chapter 2 of "The Poverty of Philosophy", by Karl Marx https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/ch02.htm

- Shrimp, Kaleb (2009). "The Validity of Karl Marx's Theory of Historical Materialism". Major Themes in Economics 11 (1): 35–56. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/mtie/vol11/iss1/5/. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Nadeau, Jean-Benoit; Barlow, Julie (2003). Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong: Why We Love France But Not The French. Sourcebooks, Inc.. p. 62. https://archive.org/details/sixtymillionfren00nade_041.

- "The MCAT writing assignment.". Wisebridge Learning Systems, LLC. http://www.wikipremed.com/mcat_essay.php. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Advisory Board

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

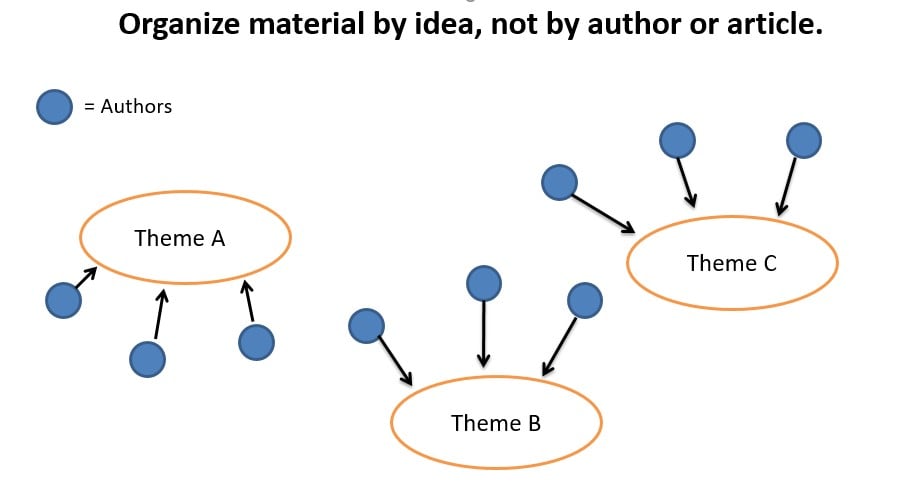

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

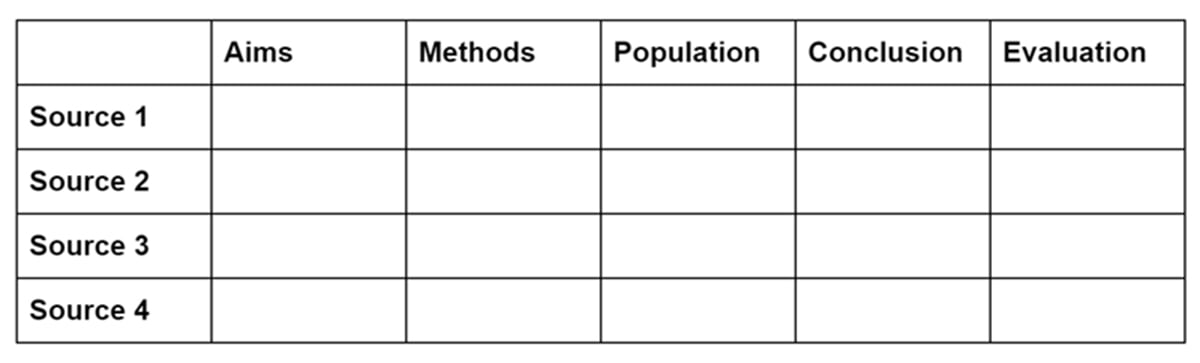

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

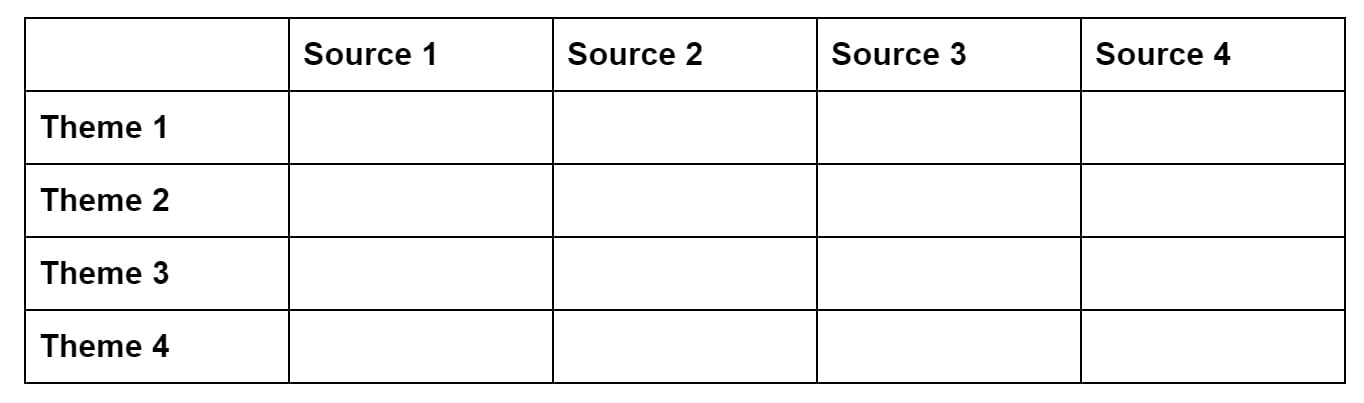

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

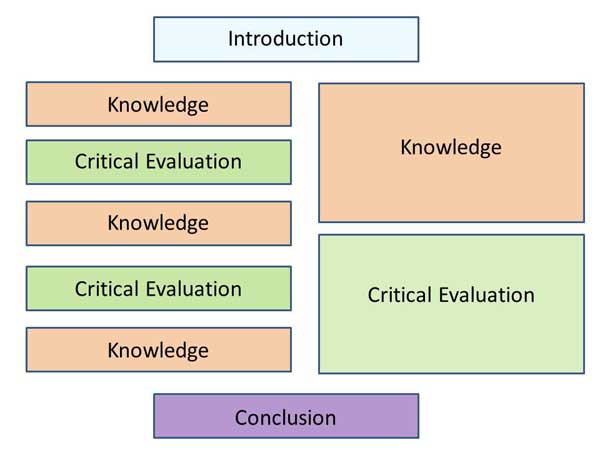

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

How to write a synthesis essay

- January 1, 2024

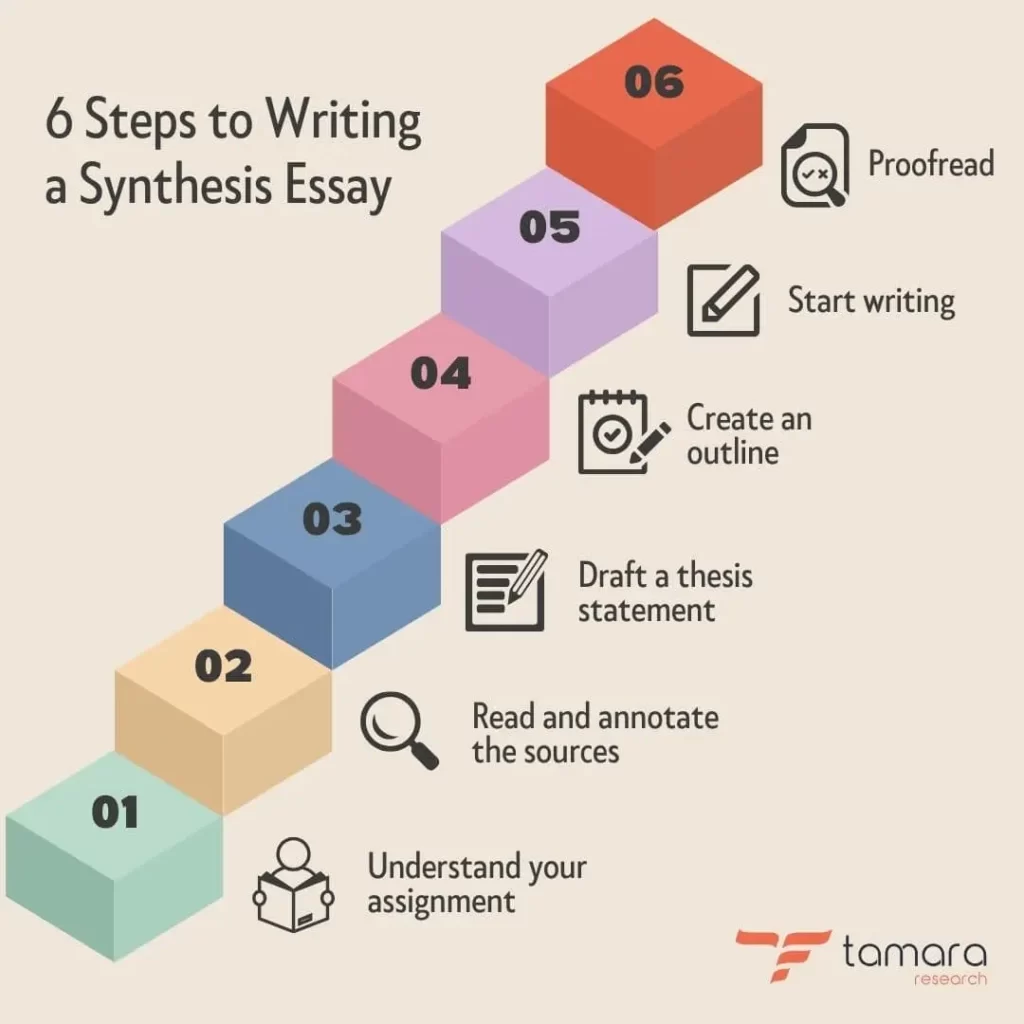

Synthesis essay is a challenging form of academic writing in which you combine multiple sources into a coherent and persuasive argument.

When writing one, better follow a series of basic steps that we will explain in the next paragraphs to write a great essay.

So let’s quickly start learning how to write a great synthesis essay.

Quick summary

- Take the time to understand the essay prompt to grasp the requirements of the assignment.

- Engage in extensive research and gather information from a variety of reputable sources.

- Develop a strong thesis statement and outline.

- Start writing your introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Make sure to include smooth transitions between these paragraphs.

- Use the proper citation or formatting (APA, MLA, etc.) and make sure you proofread your essay.

Synthesis essay definition

What is a synthesis essay?

Your primary goal with a synthesis essay is to provide a unique perspective, supported by evidence. For example, suppose you have two distinct essays or research papers on “excessive social media usage” and “the effects of social media on psychology.”

In your synthesis essay, you can blend these two sources into a cohesive argument like “the psychological impacts of excessive social media usage on individuals.”

Synthesis essay introduction

The introduction is the opening paragraph of a synthesis essay, where you present the topic and provide background information. Like a usual introduction , it should not be more than 10% of your essay.

- It should include a clear and concise thesis statement that states the main argument or viewpoint of the essay.

- It should reflect the synthesis of information from multiple sources.

Now let’s have a look at the introduction example below.

Synthesis essay introduction example

Introduction, body paragraphs.

The body paragraphs form the core of the synthesis essay. Each paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of the argument and present evidence and analysis from the sources to support the thesis statement. When writing body paragraphs:

- Use topic sentences to introduce the main idea of each paragraph

- Make use of transition words to create a smooth flow between paragraphs.

Let’s have a look at a body paragraph example.

Synthesis essay body paragraph example

Synthesis essay conclusion.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay. A compelling conclusion leaves a lasting impact on the reader, reinforcing the essay’s main message.

- Restate the thesis statement slightly different.

- Summarize the main points discussed in the body paragraphs and emphasize the significance of the overall synthesis

Let’s have a look at the components of a conclusion paragraph below.

Synthesis essay conclusion example

Now that we’ve seen a short example of synthesis essay, let’s continue with the steps to write a great one.

Steps on writing a synthesis essay

In this section, we’ll guide you through the writing process with each steps explained in detail and examples.

Step 1 - Understand your assignment

- Depending on your field of study, you may need to adhere to standard formatting styles such as MLA , APA , or Chicago.

- Consider that formatting expectations may be different. Pay attention to certain guidelines provided by your instructor.

Example of a synthesis essay assignment

- Investigate the impact of artificial intelligence on the job market and society.

- Synthesize at least three different sources, including academic articles, news reports, and opinion pieces, to discuss the benefits and challenges posed by AI's integration into various industries.

- Consider the ethical implications, potential job displacement, and the role of policymakers in addressing these changes.

- Use correct APA 7 citation format and make sure the essay is at least 1000 words.

So you see an example above, take some time to carefully review the prompt, and give particular attention to the formatting requirements.

Step 2 - Read and annotate the sources

After finding relevant sources, read each one critically by highlighting key ideas and arguments. Annotating sources with concise summaries and evaluative comments helps in later stages of the essay writing process.

- Academic Journals and Research Papers: These are scholarly articles written by experts in a particular field.

- Books: Books: written by reputable authors and published by well-known publishers can be valuable sources of information.

- Government Publications: Reports, statistics, and studies published by government agencies can be reliable sources of data.

- Newspapers and Magazines: Articles from reputable newspapers and magazines can offer current and relevant information on various topics.

Step 3 - Draft a thesis statement

A well-crafted thesis statement forms the basis of any synthesis paper. It serves as the central argument, summarizing the synthesis of information gathered from selected sources.

A compelling thesis statement should be clear, concise, and debatable as it sets the tone for the entire paper.

Synthesis essay thesis statement example

....(introduction starts) ....(introduction continues) ....(introduction continues) The pursuit of space exploration has had profound effects on scientific advancement, global cooperation, and technological innovation, and has also raised ethical considerations. Thesis statement, which is usually the last sentence of your introduction

Step 4 - Create an outline

Creating an outline helps to organize the structure of the essay systematically. Using a formal approach with Roman numerals allows for an orderly arrangement of topics and supporting details.

With an outline , you can use subcategories to cite specific points and integrate references to various sources. Or simply structure your whole essay before you start.

Synthesis essay outline example

Outline sample

- Hook sentence

- Background information

- Thesis statement (Your argument & claim)

- Topic sentene

- Supporting detail 1

- Supporting detail 2

- Supporting evidence

- Topic sentence

- Counterpoint

- Restatement of thesis

- Summarize main points

- Closing sentence

Step 5 - Start writing your essay

With the outline, structure your essay into introduction , body paragraphs , and conclusion .

First draft won’t be perfect, no worries. Here you simply start writing your essay from intro to the conclusion.

Refer to our Introduction-Body-Conclusion examples above to complete this step!

Step 6 - Proofread your essay

- Make sure your grammar is accurate and clear. If possible, use tools like Grammarly .

- Read aloud your essay to notice details and mistakes.

- Let your essay sit for a couple days and make someone else read it. They may notice the mistakes you've overseen.

- Utilize an AI paraphrasing tool to check for any potential improvements in sentence structure and wording.

5-Paragraph Synthesis Essay Example

So now that you’ve seen all steps of writing a synthesis essay, it’s time to analyze a 5-paragraph example to have practical information. Simply see the essay example below and analyze how each sentence contributes to overall structure of essay.

The Rise of Telecommuting: A Blessing or a Curse?

And that’s all for today. If you want to keep learning more about academic writing, feel free to visit our extensive Learning Center or YouTube Channel .

Recently on Tamara Blog

How to write a discussion essay (with steps & examples), writing a great poetry essay (steps & examples), how to write a process essay (steps & examples), writing a common app essay (steps & examples), how to write a synthesis essay (steps & examples), how to write a horror story.

- Essay Editor

Synthesis Essay Examples

A synthesis essay is another piece of academic discourse that students often find difficult to write. This assignment indeed requires a more nuanced approach to writing and performing research. It’s particularly relevant to students taking an AP English Language and Composition exam, so learning how to write a synthesis essay is crucial to getting a high score.

This article will explore the definition of a synthesis essay, its functions, and objectives, and provide a tutorial on how to write a synthesis essay.

What is a synthesis essay?

To understand how to write a synthesis essay, we first need to figure out why it is called this way.

The word “synthesis” comes from the Greek language where it means “composition” or “collection.” This means that a synthesis essay can be interpreted as a piece of writing that combines something together. But what?

The Advanced Placement (AP) Program known for developing complex courses for high-school students includes a synthesis essay as one of its Language and Composition exam questions. In it, the AP Program asks students to analyze several sources of information and write an essay that “synthesizes” (or incorporates) evidence from some of the sources.

Thus, a synthesis essay is a written text that explores a certain issue using perspectives derived from multiple different sources.

Synthesis essay: format and objectives

Unlike other types of academic analysis, synthesis questions do not aim to evaluate the overall persuasiveness of your arguments. As a writer, you should aim to analyze, evaluate, and integrate diverse ideas into a coherent whole. Here are some of the skills students need to demonstrate in their synthesis essays:

- Analyzing sources . Before you learn how to start a synthesis essay, your task is to read and analyze the sources presented to you and understand what they’re about.

- Assessing the arguments . After familiarizing yourself with the available sources, you are supposed to evaluate if the arguments they support are strong or weak, which will help you determine the course of your essay.

- Identifying common positions . The next skill you must demonstrate is identifying common positions across the sources. By comparing and contrasting different viewpoints, the writer should be able to detect repeating ideas that contribute to a deeper understanding of the topic.

- Integrating sources . Your main task in a synthesis essay is combining ideas from different authors to create a cohesive argument. This will help you show how well you can extract information from various sources.

As you see, the chief goal of synthesis questions is to show how well you can analyze sources and derive information from them.

How to start a synthesis essay: tutorial

During an AP examination, you don’t have a lot of time to write the text. It can be stressful, and it’s not rare for students to panic and forget what to do. Don’t worry, with these simple steps, you’ll be able to create a great synthesis essay and ace your exam.

1. Scan the given sources

At first, you will be handed six sources that you’re supposed to briefly examine. These can include academic and newspaper articles, graphs, schedules, prompts, and other documents that can be used to support your future thesis statement.

Remember that you don’t have a lot of time, so take a quick look at the documents and leave short remarks that can help you remember which source supports or argues a certain opinion.

2. Develop your stance

After you’ve studied the sources, it’s time to come up with your stance and thesis statement. Note that, unlike other essays, the stance you must take in your synthesis essay might not correlate with your actual opinion.

Your task is to choose a position that you can support with the sources provided to you. This will showcase your ability to draw an unbiased and logical conclusion from a wide range of references. However, your stance should express an original idea and cannot paraphrase the points given in the source texts.

3. Write your essay

Your essay should start with a two or three-sentence-long introduction that gives background to the topic you’re going to be writing about. It should also include your thesis – the idea based on the evidence you’ve gathered that you’re going to defend in the next part of your essay. Don’t use personal pronouns as a synthesis essay provides an overview of facts instead of your opinion

The body of your synthesis essay should be built of several arguments. Each argument should refer to a specific part of your thesis and provide evidence to support the claims. Use the sources provided to you as evidence to validate your arguments. You should use at least three sources, but the more you incorporate in your text, the better. You can draw arguments and evidence from your background knowledge or include counter-arguments from the remaining sources. When you refer to the original documents, make sure to include the number of the source in brackets at the end of a sentence.

In your conclusion, restate your original thesis and summarize what you stated before. Don’t repeat the same thoughts. Instead, include a new idea you haven’t mentioned before or a call to action to finish your essay properly.

Synthesis essay: examples

The list of sources provided as part of the examination:

- A New York Times article about the relevance of blue-collar workers;

- A Washington Post article about the uselessness of art degrees;

- The Economist’s article about the decreasing wages of college graduates;

- A New Your Times article proving that college does pay off;

- An article about a businessman giving money to teens to start businesses instead of going to college

- A survey on whether college education is worth it

Is college worth it?

In the current era of shifting economic landscapes and evolving societal expectations, the value of higher education has become a subject of intense scrutiny. While some decades ago, a college education was considered the only solution to a better life, nowadays this sentiment is no longer relevant. Higher education can no longer guarantee high salaries and employment, not to mention the unbearable strain it puts on a future graduate’s finances.

The modern world of employment has shifted. While decades ago society needed information-centric professionals, now the situation is different. With the Internet, employers can now find new hires from all over the world with much cheaper salary expectations, leaving local college graduates with no choice but to agree to a lower pay than they expected[3]. This demonstrates the new trend of decreasing rewards for higher education that is very likely to continue in the future.

Another issue is the lack of employment in certain areas. It is no secret that Art and Humanities graduates have a tough time finding positions with adequate pay in the field they studied[2]. Many of them have to search for employment in other fields that have nothing to do with their degrees, which further proves that higher education does not provide job security.

Furthermore, the cost of higher education in America has been the subject of many debates. Even with scholarships and financial aid, many students still find themselves facing daunting loan repayments upon graduation[6]. This financial pressure can delay important milestones such as buying a home, starting a family, or saving for retirement. Additionally, the job market may not always align with graduates' expectations, making it challenging to secure well-paying positions to effectively manage their debt. As a result, the financial impact of college can be felt long after receiving a diploma, shaping the economic landscape of young professionals for years to come.

In conclusion, higher education no longer offers guaranteed employment and financial stability benefits, often leaving graduates with an exorbitant debt they can not afford. Because of this, the governments should reevaluate their current educational and economic policies and develop other areas of education like vocational schools to provide stability to future generations.

Conclusion: Writing a synthesis essay

A synthesis essay tests your ability to conduct objective analysis and derive facts from multiple different references. It helps you learn to put aside your personal bias and provide an objective overview of information even if it contradicts your opinion. To produce a high-scoring synthesis essay, work on your analytical skills and use them to find evidence to defend your position.

If answering synthesis questions gives you trouble, use essay generator Aithor to generate sample essays, learn how to derive main information from source texts, create a plan, and express your thoughts concisely and eloquently.

Related articles

Will i get caught using chat gpt.

ChatGPT has been around for a little over a year but already found popularity among all groups of users. School and college students have taken a particular liking to it. However, many students avoid using the chatbot for fear that their teacher might catch them. Read this article to learn more about ChatGPT, its features, and whether your teacher can actually find out if you use it for your homework. What is Chat GPT? ChatGPT was first introduced to the world in November 2022. At the time, ...

Create a Perfect Essay Structure

Hello Aithors! We're back again with another feature highlight. Today, we want to talk about a tool that can be a game-changer for your essay writing process - our Table of Contents tool. Writing an essay isn't just about getting your ideas down on paper. It's about presenting them in a clear, structured way that makes sense to your reader. However, figuring out the best structure for your essay can sometimes be a tough nut to crack. That's why we developed the Table of Contents feature. The b ...

How To Write Reflection Essays

How often do you contemplate how the tapestry of your experiences shapes your thoughts? A reflection paper lets you explore that. It's like deep diving into your life’s precious moments, examining how stories, books, events, or even lectures have influenced your views. This type of academic essay integrates a personal perspective, allowing you to openly express your opinions. In this guide, we will delve into the specifics of reflective writing, share some tips, and show some self-reflection es ...

Proposal Essay Examples: Convincing Ideas for Your Research Paper or Essay

Struggling to craft a captivating and well-built proposal essay? Many students find it challenging to compose a proposal-based essay and struggle to generate convincing ideas. If this sounds familiar, read on. In this comprehensive guide, we streamline the process of brainstorming and composing work, offering resources like suggestions on how to write a proposal essay, suggested steps when writing, useful examples, and efficient essay-crafting tips. Developed through several years of expertise ...

Ace Your Graduation Speech with Aithor

Hello, Aithors! Can you feel it? That's the buzz of graduation season in the air:) And while we're all about the caps flying and the proud smiles, we also know that being asked to write a graduation speech can feel a bit like being handed a mountain to climb. Crafting a graduation speech is all about capturing the spirit of the journey you've been on, from the triumphs to the trials, and everything in between. It's a reflection of where you've been, and a beacon of light pointing towards where ...

How to Write an Evaluation Essay That Engages and Persuades: Helpful Tips and Inspiring Examples

Are you feeling unsure about how to effectively evaluate a subject from your own perspective in an evaluation essay? If you're struggling to understand how to present a balanced assessment, don't worry! We're here to guide you through the process of writing an evaluation that showcases your critical thinking skills. What Is an Evaluation Essay? An evaluation essay is a type of writing in which the writer gives their opinion on a topic. You look at something carefully and think about how good ...

Literary Analysis Essay Example: Discover How to Analyze Literature and Improve Your Writing Skills

Creating a literary analysis essay is one of the most interesting assignments during college and high school studies. It needs both good text interpreting and analytical skills. The number of proper forms is great, including short stories and novels, poems and ballads, comedies and dramas. Any literary work may be analyzed. In brief, when writing this paper a student should give a summary of the text and a detailed review of the language, structure, and other stuff the author used to express hi ...

Biographical Essay: Tips and Tricks for Writing a Perfect Biography

Biographical essays are some of the most common texts you can find on the Internet. When you browse a Wiki article about your favorite singer, you are basically reading a biography paper. However, in academia, there are certain rules students need to follow to get perfect marks for their papers. In this article, we will explore what a biographical essay is, why it matters, and how to write an essay about a person. What is a biographical essay? A biographical essay is a paper that focuses on ...

How to Write a Synthesis Essay: Your Guide From Start to Finish

Today, we're swamped with information, like reading 174 newspapers every day. It comes from all over—news, social media, science, and more. This flood might make you feel overwhelmed and lost in a sea of facts and opinions. But being able to make sense of it all is crucial.

This guide isn't just about handling all that info; it's about using it to write awesome essays. We'll show you step by step how to pick a topic and organize your essay. Let's dive in and learn how to turn scattered facts into powerful essays that really stand out.

What Is a Synthesis Essay

The synthesis essay is a powerful tool in writing. It's not just about gathering facts but about connecting them to make a clear and strong argument.

Writing a synthesis essay allows you to dive deep into ideas. You have to find similarities between different sources—like articles, studies, or arguments—and use them to tell a convincing story.

In today's world, where we're bombarded with information, synthesis essays are more important than ever. They let us explore how different ideas fit together and help us express our thoughts on complex topics. Whether you're writing about literature, science, history, or current events, a synthesis essay shows off your ability to analyze and understand a topic from all angles. And if you're struggling with this task, just ask us to ' write paper for me ,' and we'll handle your assignment for you.

Explanatory vs. Argumentative Synthesis Essays

In synthesis writing, there are two main types: explanatory and argumentative. Understanding these categories is key because they shape how you approach your essay.

Explanatory:

An explanatory synthesis essay does just what it says—it explains. These essays aim to give a balanced view of a topic by gathering information from different sources and presenting it clearly. They don't try to persuade; instead, they focus on providing information and making things easier to understand. They're like comprehensive summaries, breaking down complex ideas for a broader audience. These essays rely heavily on facts and expert opinions, avoiding personal bias.

Argumentative:

On the flip side, argumentative synthesis essays are all about persuasion. Their main goal is to take a stance on an issue and convince the reader. They gather information from various sources not only to present different views but also to build a strong argument. Argumentative essays aim to sway the reader's opinion by using gathered information as evidence. These essays express opinions and use rhetorical strategies to persuade.

And if you're keen on knowing how to write an informative essay , we've got you covered on that, too!

Synthesis Essay Structure

To craft a strong synthesis essay, you need a solid foundation. Here's a structured approach to help you nail it:

Introductory Paragraph:

- To kick things off, grab your reader's attention with a catchy hook or interesting fact. Give a bit of background info about your topic and the sources you'll be using, as it can help readers understand your topic better! Then, lay out your main argument in a clear thesis statement.

Body Paragraphs:

- Each paragraph should focus on a different aspect of your topic or source. Start with a topic sentence that links back to your thesis. Introduce the source you're discussing and highlight its main points. Also, using quotes, paraphrases, or summaries from your sources can make your arguments stronger.

Synthesis :

- This part is where your essay comes together. Look for common themes or differences among your sources. Use your analysis to build a strong argument. Don't forget to address any opposing viewpoints if they're relevant!

Conclusion :

- Wrap things up by restating your thesis and summarizing your main points. Explain why your argument is important and what it means in the bigger picture. End with a thought-provoking statement to leave a lasting impression.

References :

- Finally, don't forget to list all your sources properly using the right citation style, like MLA or APA. Do you know that different citation styles have different rules? So, make sure you follow the right one!

Choosing a Synthesis Essay Topic

Picking essay topics is just the beginning. To write a great synthesis essay, you need to carefully evaluate and connect different sources to build a strong argument or viewpoint. Here's a step-by-step infographic guide to help you choose the right synthesis essay topics wisely.

How to Write a Synthesis Essay with Easy Steps

Writing a synthesis essay is similar to a compare and contrast essay . It requires a methodical approach to blend information from different sources into a strong and persuasive argument. Here are some crucial steps and tips to help you along the way.

- Clarify Your Purpose: First, decide if you're writing an explanatory or argumentative synthesis essay. This choice will set the tone and direction for your essay.

- Source Selection and Analysis: Choose credible and relevant sources for your topic, balancing different types like articles, books, and websites. Analyze each source carefully, noting the main ideas and evidence presented.

- Formulate a Strong Thesis Statement: Create a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your essay. It should express your main argument or perspective.

- Structure Your Essay: Organize your essay with a clear synthesis essay outline, including an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a specific aspect of your topic.

- Employ Effective Transition Sentences: Use transition sentences to connect your ideas and paragraphs smoothly, ensuring a cohesive flow in your essay.

- Synthesize Information: Blend information from your sources within your paragraphs. Discuss how each source contributes to your thesis and highlight common themes or differences.

- Avoid Simple Summarization: Don't just summarize your sources—analyze them critically and use them to build your argument.

- Address Counterarguments (if applicable): Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counter them with well-supported arguments, showing a deep understanding of the topic.

- Craft a Resolute Conclusion: Summarize your main points and restate your thesis in the conclusion. Emphasize the importance of your argument or insights, and end with a thought-provoking statement or call to action.

- Revise and Proofread: Check your essay for clarity, coherence, and grammar mistakes. Ensure your citations are correct and follow the chosen citation style, like MLA or APA.

Ready to Transform Your Synthesis Essay from Bland to Grand?

Let's tap into the magic of our expert wordsmiths, who will create an essay that dances with ideas and dazzles with creativity!

Synthesis Essay Format

Choosing the right citation style can enhance the credibility and professionalism of your paper. The format of your synthesis paper depends on the specific guidelines given by your instructor. They usually fall into one of the popular styles: MLA, APA, or Chicago, each used in different academic fields.

1. MLA (Modern Language Association):

- Uses in-text citations with the author's last name and page number.

- Includes a 'Works Cited' page at the end listing all sources.

- Focuses on the author and publication date.

- Often used in humanities essays, research papers, and literary analyses.

2. APA (American Psychological Association):

- Uses in-text citations with the author's last name and publication date in parentheses.

- Includes a 'References' page listing all sources alphabetically.

- Emphasizes the publication date and scientific precision.

- Commonly used in research papers, scholarly articles, and scientific studies.

3. Chicago Style:

- Offers two documentation styles: Notes-Bibliography and Author-Date.

- Notes-Bibliography uses footnotes or endnotes for citations, while Author-Date uses in-text citations with a reference list.

- Suitable for various academic writing, including research papers and historical studies.

- Provides flexibility in formatting and citation methods, making it adaptable to different disciplines.

Synthesis Essay Example

Here are two examples of synthesis essays that demonstrate how to apply the synthesis process in real life. They explore interesting topics and offer practical guidance for mastering the art of writing this type of paper.

Synthesis Essay Tips

Crafting a strong synthesis essay requires careful planning and effective techniques. Here are five essential tips to help you write your best paper:

- Diverse Source Selection : Choose a range of reliable sources that offer different viewpoints on your topic. Make sure they're recent and relevant to your subject.

- Seamless Source Integration : Avoid just summarizing your sources. Instead, blend them into your essay by analyzing and comparing their ideas. Show how they connect to build your argument.

- Balanced Tone : Maintain an impartial tone in your writing, even if you have personal opinions. Synthesis essays require objectivity, so they present different viewpoints without bias.

- Focus on Synthesis : Remember, synthesis essays are about linking ideas, not just summarizing sources. Explore how your sources relate to each other to create a cohesive argument.

- Address Counterarguments : Like in persuasive essays topics , acknowledge opposing viewpoints and explain why your perspective is stronger. This demonstrates your understanding of the topic and adds depth to your argument.

Concluding Thoughts

When writing a synthesis essay, it's essential to pick trustworthy sources, blend them effectively to build your argument and stay objective. Use smooth transitions, address counterarguments thoughtfully, and focus on analyzing rather than just summarizing. By following these steps, you'll create essays that inform, persuade, and engage your readers!

Want an Essay that Sings, Sparkles, and Stuns?

Fear not! Our expert wordsmiths are here to turn your thoughts into a symphony of ideas!

How Should You Conclude a Synthesis Essay?

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

Related Articles

.webp)

Capstone Form and Style

Evidence-based arguments: synthesis, paraphrasing and synthesis.

Synthesis is important in scholarly writing as it is the combination of ideas on a given topic or subject area. Synthesis is different from summary. Summary consists of a brief description of one idea, piece of text, etc. Synthesis involves combining ideas together.

Summary: Overview of important general information in your own words and sentence structure. Paraphrase: Articulation of a specific passage or idea in your own words and sentence structure. Synthesis: New interpretation of summarized or paraphrased details in your own words and sentence structure.

In the capstone, writers should aim for synthesis in all areas of the document, especially the literature review. Synthesis combines paraphrased information, where the writer presents information from multiple sources. Synthesis demonstrates scholarship; it demonstrates an understanding of the literature and information, as well as the writer’s ability to connect ideas and develop an argument.

Example Paraphrase

From allan and zed (2012, p. 195).

Supervision, one practice in transactional leadership theory, is especially effective for small business owners. Improved retention not only contributes to an efficient workplace, but it promotes local commercial stability and cultural unity. Other management styles informed by transactional theory can also benefit communities.

Sample Paraphrase

Allan and Zed (2012) noted that supervision and other transactional leadership strategies provide advantages for small business owners and their surrounding communities.

This paraphrase DOES:

- include the main idea,

- summarize the key information using fewer words than the original text, and

- include a citation to credit the source.

Synthesis Language

Synthesis is achieved by comparing and contrasting paraphrased information on a given topic. Discussions of the literature should be focused not on study-by-study summaries (see the Creating a Literature Review Outline SMRTguide). Writers should begin by using comparison language (indicated in bold and highlighted text in the examples below) to combine ideas on a given topic:

- Keller (2012) found that X occurred. Likewise, Daal (2013) found that X occurred but also noted that the effects of X differed from those suggested by Keller (2012).

- Schwester (2013) reported results consistent with findings in Hill’s (2011) and Yao’s (2012) studies.

- Although Mehmad (2012) suggested X, O’Donnell (2013) recommended a different approach.

Again, the focus of synthesis is to combine ideas on a given topic and for the writer to use that to review the existing literature or support an overall argument (i.e., in the problem statement, rationale and justification for the method, etc.).

For more information and examples on synthesis, paragraph structure, and the MEAL Plan strategy for writing review additional Form and Style resources:

- SMRTguide on Reverse Outlining and the MEAL Plan

- SMRTguide on Prioritizing Parenthetical Citations

- Reading to Write

- Previous Page: Quoting

- Next Page: MEAL Plan

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

57 Synthesis

Synthesis writing.

Although at its most basic level a synthesis involves combining two or more summaries, synthesis writing is more difficult than it might at first appear because this combining must be done in a meaningful way and the final essay must generally be thesis-driven. In composition courses, “synthesis” commonly refers to writing about printed texts, drawing together particular themes or traits that you observe in those texts and organizing the material from each text according to those themes or traits. Sometimes you may be asked to synthesize your own ideas, theory, or research with those of the texts you have been assigned. In your other college classes you’ll probably find yourself synthesizing information from graphs and tables, pieces of music, and art works as well. The key to any kind of synthesis is the same.

Synthesis in Every Day Life

Whenever you report to a friend the things several other friends have said about a film or CD you engage in synthesis. People synthesize information naturally to help other see the connections between things they learn; for example, you have probably stored up a mental data bank of the various things you’ve heard about particular professors. If your data bank contains several negative comments, you might synthesize that information and use it to help you decide not to take a class from that particular professor. Synthesis is related to but not the same as classification, division, or comparison and contrast. Instead of attending to categories or finding similarities and differences, synthesizing sources is a matter of pulling them together into some kind of harmony. Synthesis searches for links between materials for the purpose of constructing a thesis or theory.

Synthesis Writing Outside of College

The basic research report (described below as a background synthesis) is very common in the business world. Whether one is proposing to open a new store or expand a product line, the report that must inevitably be written will synthesize information and arrange it by topic rather than by source. Whether you want to present information on child rearing to a new mother, or details about your town to a new resident, you’ll find yourself synthesizing too. And just as in college, the quality and usefulness of your synthesis will depend on your accuracy and organization.

Key Features of a Synthesis

(1) It accurately reports information from the sources using different phrases and sentences; (2) It is organized in such a way that readers can immediately see where the information from the sources overlap;. (3) It makes sense of the sources and helps the reader understand them in greater depth.

The Background Synthesis

In the process of writing his or her background synthesis, the student explored the sources in a new way and become an expert on the topic. Only when one has reached this degree of expertise is one ready to formulate a thesis. Frequently writers of background synthesis papers develop a thesis before they have finished. In the previous example, the student might notice that no two colleges seem to agree on what constitutes “co-curricular,” and decide to research this question in more depth, perhaps examining trends in higher education and offering an argument about what this newest trend seems to reveal. [ More information on developing a research thesis .] The background synthesis requires that you bring together background information on a topic and organize it by topic rather than by source. Instructors often assign background syntheses at the early stages of the research process, before students have developed a thesis–and they can be helpful to students conducting large research projects even if they are not assigned. In a background synthesis of Internet information that could help prospective students select a college, for example, one paragraph might discuss residential life and synthesize brief descriptions of the kinds of things students might find out about living on campus (cited of course), another might discuss the academic program, again synthesizing information from the web sites of several colleges, while a third might synthesize information about co-curricular activities. The completed paper would be a wonderful introduction to internet college searching. It contains no thesis, but it does have a purpose: to present the information that is out there in a helpful and logical way.

[See also “ Preparing to Write the Synthesis Essay ,” “ Writing the Synthesis Essa y,” and “ Revision .”]

A Thesis-driven Synthesis

On the other hand, all research papers are also synthesis papers in that they combine the information you have found in ways that help readers to see that information and the topic in question in a new way. A research paper with a weak thesis (such as: “media images of women help to shape women’s sense of how they should look”) will organize its findings to show how this is so without having to spend much time discussing other arguments (in this case, other things that also help to shape women’s sense of how they should look). A paper with a strong thesis (such as “the media is the single most important factor in shaping women’s sense of how they should look”) will spend more time discussing arguments that it rejects (in this case, each paragraph will show how the media is more influential than other Sometimes there is very little obvious difference between a background synthesis and a thesis-driven synthesis, especially if the paper answers the question “what information must we know in order to understand this topic, and why?” The answer to that question forms the thesis of the resulting paper, but it may not be a particularly controversial thesis. There may be some debate about what background information is required, or about why, but in most cases the papers will still seem more like a report than an argument. The difference will be most visible in the topic sentences to each paragraph because instead of simply introducing the material for the paragraph that will follow, they will also link back to the thesis and assert that this information is essential because…

factors in that particular aspect of women’s sense of how they should look”).

[See also thesis-driven research papers .] [See also “ Preparing to Write the Synthesis Essay ,” “ Writing the Synthesis Essa y,” and “ Revision .”]

A Synthesis of the Literature

Because each discipline has specific rules and expectations, you should consult your professor or a guide book for that specific discipline if you are asked to write a review of the literature and aren’t sure how to do it. In many upper level social sciences classes you may be asked to begin research papers with a synthesis of the sources. This part of the paper which may be one paragraph or several pages depending on the length of the paper–is similar to the background synthesis . Your primary purpose is to show readers that you are familiar with the field and are thus qualified to offer your own opinions. But your larger purpose is to show that in spite of all this wonderful research, no one has addressed the problem in the way that you intend to in your paper. This gives your synthesis a purpose, and even a thesis of sorts.

Preparing to write your Synthesis Essay

Sometimes the wording of your assignment will direct you to what sorts of themes or traits you should look for in your synthesis. At other times, though, you may be assigned two or more sources and told to synthesize them. In such cases you need to formulate your own purpose, and develop your own perspectives and interpretations. A systematic preliminary comparison will help. Begin by summarizing briefly the points, themes, or traits that the texts have in common (you might find summary-outline notes useful here). Explore different ways to organize the information depending on what you find or what you want to demonstrate ( see above ). You might find it helpful to make several different outlines or plans before you decide which to use. As the most important aspect of a synthesis is its organization, you can’t spend too long on this aspect of your paper! Regardless of whether you are synthesizing information from prose sources, from laboratory data, or from tables and graphs, your preparation for the synthesis will very likely involve comparison . It may involve analysis , as well, along with classification, and division as you work on your organization.

Writing the Synthesis Essay

The introduction (usually one paragraph :

A synthesis essay should be organized so that others can understand the sources and evaluate your comprehension of them and their presentation of specific data, themes, etc. The following format works well:

- Contains a one-sentence statement that sums up the focus of your synthesis. 2. Also introduces the texts to be synthesized: (i) Gives the title of each source (following the citation guidelines of whatever style sheet you are using); (ii) Provides the name of each author; (ii) Sometimes also provides pertinent background information about the authors, about the texts to be summarized, or about the general topic from which the texts are drawn.

The body of a synthesis essay :

This should be organized by theme, point, similarity, or aspect of the topic. Your organization will be determined by the assignment or by the patterns you see in the material you are synthesizing. The organization is the most important part of a synthesis, so try out more than one format. Be sure that each paragraph : 1. Begins with a sentence or phrase that informs readers of the topic of the paragraph; 2. Includes information from more than one source; 3. Clearly indicates which material comes from which source using lead in phrases and in-text citations. [Beware of plagiarism: Accidental plagiarism most often occurs when students are synthesizing sources and do not indicate where the synthesis ends and their own comments begin or vice verse.] 4. Shows the similarities or differences between the different sources in ways that make the paper as informative as possible; 5. Represents the texts fairly–even if that seems to weaken the paper! Look upon yourself as a synthesizing machine; you are simply repeating what the source says, in fewer words and in your own words. But the fact that you are using your own words does not mean that you are in anyway changing what the source says.

Conclusion :

When you have finished your paper, write a conclusion reminding readers of the most significant themes you have found and the ways they connect to the overall topic. You may also want to suggest further research or comment on things that it was not possible for you to discuss in the paper. If you are writing a background synthesis, in some cases it may be appropriate for you to offer an interpretation of the material or take a position (thesis). Check this option with your instructor before you write the final draft of your paper.

Checking your own writing or that of your peers

Read a peer’s synthesis and then answer the questions below. The information provided will help the writer check that his or her paper does what he or she intended (for example, it is not necessarily wrong for a synthesis to include any of the writer’s opinions, indeed, in a thesis-driven paper this is essential; however, the reader must be able to identify which opinions originated with the writer of the paper and which came from the sources).

- What do you like best about your peer’s synthesis? (Why? How might he or she do more of it?);

- Is it clear what is being synthesized? (i.e.: Did your peer list the source(s), and cite it/them correctly?);

- Is it always clear which source your peer is talking about at any given moment? (Mark any places where it is not clear);

- Is the thesis of each original text clear in the synthesis? (Write out what you think each thesis is);

- did you identify the same theses as your peer? (If not, how do they differ?);

- did your peer miss any key points from his or her synthesis? (If so, what are they?);

- did your peer include any of his own opinions in his or her synthesis? (If so, what are they?);

- Where there any points in the synthesis where you were lost because a transition was missing or material seems to have been omitted? (If so, where and how might it be fixed?);

- What is the organizational structure of the synthesis essay? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram);

- Does this structure work? (If not, how might your peer revise it?);

- How is each paragraph structured? (It might help to draw a plan/diagram);

- Is this method effective? (If not, how should your peer revise?);

- Was there a mechanical, grammatical, or spelling error that annoyed you as you read the paper? (If so, how could the author fix it? Did you notice this error occurring more than once?) Do not comment on every typographical or other error you see. It is a waste of time to carefully edit a paper before it is revised!

- What other advice do you have for the author of this paper?

Write What Matters Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

Persuasive Writing In Three Steps: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

April 14, 2021 by Ryan Law in

Great writing persuades. It persuades the reader that your product is right for them, that your process achieves the outcome they desire, that your opinion supersedes all other opinions. But spend an hour clicking around the internet and you’ll quickly realise that most content is passive, presenting facts and ideas without context or structure. The reader must connect the dots and create a convincing argument from the raw material presented to them. They rarely do, and for good reason: It’s hard work. The onus of persuasion falls on the writer, not the reader. Persuasive communication is a timeless challenge with an ancient solution. Zeno of Elea cracked it in the 5th century B.C. Georg Hegel gave it a lick of paint in the 1800s. You can apply it to your writing in three simple steps: thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

Use Dialectic to Find Logical Bedrock