English Heritage

- https://www.facebook.com/englishheritage

- https://twitter.com/englishheritage

- https://www.youtube.com/user/EnglishHeritageFilm

- https://instagram.com/englishheritage

Research on Stonehenge

Stonehenge has been the subject of speculation, theory and research since the Middle Ages. Our understanding of the monument is still changing as excavations and modern archaeological techniques yield more information. Yet there are many questions that we have still to answer.

Here we take a look at 400 years of research on Stonehenge, from the first known excavation to the very latest discoveries.

Discover the latest research

Antiquarian interest

The first known excavation at Stonehenge, in the centre of the monument, was undertaken in the 1620s by the Duke of Buckingham, prompted by a visit by King James I. [1] The king subsequently commissioned the architect Inigo Jones to conduct a survey and study of the monument. Jones argued that Stonehenge was built by the Romans. [2]

The antiquary John Aubrey surveyed Stonehenge in the late 17th century, and was the first to record the ring of pits later named after him, the Aubrey Holes. [3] His studies of stone circles in other parts of Britain led him to conclude that they were built by the native inhabitants, rather than Romans or Danes as others had proposed. As the Druids were the only prehistoric British priests mentioned in the classical texts, he attributed Stonehenge to the Druids.

Aubrey’s idea was expanded by the 18th-century antiquary William Stukeley, who surveyed Stonehenge and was the first to record the Avenue and the nearby Cursus. Among Stukeley’s theories about Stonehenge, he too thought it was a Druid monument. [4]

Early excavations and survey

In 1874 and 1877 Sir William Flinders Petrie surveyed Stonehenge in detail, and devised the numbering system for the stones that is still in use today. [5]

Concerns about the stability of the stones (especially after one of the sarsen stones and its lintel had fallen down) led to the straightening of a large leaning trilithon in 1901. Professor William Gowland directed excavations around the base of the stone, and based on the finds, he proposed a late Neolithic or early Bronze Age date for Stonehenge. [6]

A further programme of restoration and excavation, led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley, was carried out between 1919 and 1926, [7] when most of the south-eastern half of the monument was excavated. [8]

Restoration and research

Between 1950 and 1964 Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott and JFS Stone undertook a new campaign of excavations, partly to resolve some unanswered questions left by Hawley and partly in response to a large programme of stabilisation and re-erection works at the monument. [9] Atkinson proposed a three-stage chronology for Stonehenge. [10] No detailed archaeological report was completed but the excavations were published in 1995. [11]

Excavations in 1966–7 in advance of new visitor facilities led to the discovery of Mesolithic pits or postholes in the car park. [12] The ‘Stonehenge Archer’ burial was found in the ditch in 1978, [13] and a trench dug alongside the old A344 revealed a new stone hole, a possible partner to the Heel Stone. [14]

In the wider landscape, survey work was undertaken by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments (England), [15] and a programme of fieldwalking and excavation, the Stonehenge Environs Project, was completed. [16]

A decade of digging

From 2002 there was renewed interest in investigating the Stonehenge landscape, particularly on the eastern side of the World Heritage Site. Excavations in 2002 to the south of Amesbury, 3 miles (5km) from Stonehenge, led to the discovery of the Amesbury Archer. He had lived in Continental Europe before being buried in the earliest Bronze Age with gold objects, the earliest ever found in Britain. [17] Many other important burials and a late Neolithic pit or post circle were also found.

Much excavation took place in the Stonehenge landscape as part of the Stonehenge Riverside Project (2003–9), a major study led by Professor Mike Parker Pearson. This aimed to test the hypothesis that Stonehenge was linked to the ceremonial timber and earth complex at Durrington Walls via the river Avon.

The archaeologists found a roadway or avenue linking the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls to the river, as well as several small houses and structures built of timber and chalk. Analysis of the animal bones and pottery from this settlement has provided new insights into the feasting , rituals and movement of the people who built and used Stonehenge. [18]

The project also investigated the Greater Cursus, Amesbury 42 long barrow, Cuckoo Stone and Stonehenge Avenue. [19]

As part of the project, excavation took place in 2008 at Stonehenge to retrieve cremation burials which had been re-interred within Aubrey Hole 7. Analysis of the remains has shown that they represent more than 50 people, both male and female and of various ages. These people were buried at Stonehenge between about 3000 and 2800 BC. [20] Studies of their bones showed that not all had been living within the local area during the last ten years of their lives, suggesting that people may have brought their cremated dead to Stonehenge from some distance away. [21]

In the same year (2008), as part of the SPACES project (Strumble-Preseli Ancient Communities and Environmental Study), Professor Tim Darvill and the late Geoffrey Wainwright opened a small trench within the stone circle. [22] This revealed surprising evidence for Roman activity at Stonehenge – the Romans had dug a large pit or shaft there. The SPACES project also uncovered further details of the previous settings of the bluestones.

Landscape and laser survey

Between 2009 and 2013, research teams at English Heritage (now Historic England) undertook detailed analytical earthwork surveys of all the major monuments in the World Heritage Site, including Stonehenge. All their research reports are available to download . These surveys revealed much new information about the form and phasing of sites and were accompanied by new historical aerial photography and geophysical surveys.

Part of this project included a laser survey of Stonehenge, which revealed more Bronze Age carvings on the stones, and new information about the way the stones had been shaped. [23] Parchmarks spotted in the grass during a hot spell in the summer of 2013 led to renewed debate about whether the sarsen stone circle was completed. [24]

Also in 2013 the old A344 road bed was removed, revealing traces of the Avenue ditches and a small part of the Heel Stone ditch.

Within the wider landscape, two large-scale geophysical surveys uncovered details of both known monuments and new sites, including round barrows, small henges and two large pits within the Greater Cursus. [25]

Recent research

The last few years have brought exciting discoveries. In 2017 a new causewayed enclosure – an early Neolithic monument comprising circuits of segmented ditches – was uncovered at Larkhill, to the north of Stonehenge, during excavations before the building of new army housing.

Then in 2020 the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project announced the discovery of a large circuit of shafts, possibly natural sinkholes or artificial pits, surrounding the henge monument at Durrington Walls. [26] Later in the year, researchers using a novel geochemical approach analysed a core extracted from Stonehenge to pinpoint the probable origin of the giant sarsen stones as West Woods, 15 miles (25km) north, on the edge of the Marlborough Downs. [27]

More recently, a new bluestone monument arc or circle at Waun Mawn in the Preseli Hills has been discovered. [28] Its similarities to Stonehenge are intriguing. They include the shape and size of the unspotted dolerite stones, the potential alignment of the ‘gunsight’ entrance on midsummer solstice and the overall diameter of the monument. Empty stoneholes suggest that at least six bluestones were removed from this site at some point in prehistory, and it seems likely that at least the three existing known unspotted dolerites at Stonehenge were brought from here.

Finally, researchers examining the DNA of early Bronze Age people buried in the Stonehenge area have found close genetic relations between people buried in cemeteries at Porton Down, Wilsford and Amesbury Down. [29] These appear to be groups of related people who came over from continental Europe and continued to inter-marry among themselves, separately from the local Neolithic population.

Future research questions

Stonehenge and its surrounding landscape are a continuing focus for intense archaeological research, both by academic teams and in advance of commercial development. There are many questions about Stonehenge that we have yet to answer. A set of research questions for the monument and the wider World Heritage Site is set out in the Stonehenge WHS Archaeological Research Framework .

An air of mystery and intrigue will always surround Stonehenge. Over the last 20 years, however, our understanding has moved on dramatically – each new piece of evidence has brought answers and established further questions. The story of Stonehenge continues to evolve and change.

Find out more

History of Stonehenge

Read a full history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, from its origins about 5,000 years ago to the 21st century.

Building Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a masterpiece of engineering. How did Neolithic people build it using only the simple tools and technologies available to them?

100 years of care

In 1918, Cecil and Mary Chubb gifted Stonehenge to the nation. Our series of blog posts traces the conservation and care of Stonehenge over 100 years.

Archaeologists of Stonehenge

We take a look at some of the archaeologists who have contributed to our understanding of Stonehenge, from the 17th century to the present day.

The Stonehenge World Heritage Site Landscape

Explore this interactive map created by Historic England to find out about the latest in-depth research into the Stonehenge World Heritage Site landscape.

Why Does Stonehenge Matter?

Stonehenge is a unique prehistoric monument, lying at the centre of an outstandingly rich archaeological landscape. It is an extraordinary source for the study of prehistory.

Virtual Tour of Stonehenge

Take an interactive tour of Stonehenge with this 360 degree view from inside the stones, which explores the monument’s key features.

Explore the Stonehenge Landscape

Use these interactive images to discover what the landscape around Stonehenge has looked like from before the monument was built to the present day.

Plan of Stonehenge

Download this PDF plan to see the phases of the building of Stonehenge, from the first earthwork to the arrangement of the bluestones.

More histories

Delve into our history pages to discover more about our sites, how they have changed over time, and who made them what they are today.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Researching Stonehenge: Theories Past and Present

Archaeology International

Related Papers

Rebecca Nicole Reeves

Herb Spencer

This book begins with a reappraisal of over 250 years of fieldwork, excavation and speculation, including John Wood's highly accurate but often overlooked survey of 1740, which is the most important record of Stonehenge ever made, and the only reliable plan of the monument, before the fall of several major stones and their later re-erection in the twentieth century. The prehistoric engineering skills involved in the construction of Stonehenge have long been recognized, but the book presents, for the first time, tangible evidence to show that locked within the symmetry of the stones are precise formulae that determined their numbers, spacing, and relationships. The author explains how the Neolithic surveyors set out the fifty-six Aubrey Holes, four Station Stones, and the thirty stones in the Sarsen Circle plus the significance of the horseshoe arrangement of 5 massive trilithons at the heart of the monument. The implications are far reaching, demonstrating that the original people who designed Stonehenge in all its phases of construction, spanning over 1,500 years, employed simple and elegant geometric rules. Elaborate sightline theories, alignments and astronomical computations are questioned, allowing the rationale behind Stonehenge and other prehistoric sites, some of which conformed to the same model, to be reassessed. The purpose of this book is to review the implications of the design of the monument. It is the actual placing of the stones in their exact positions that is more puzzling than how they were brought there. The complexity is far more than might be needed as an astronomical observatory.

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society

Neil Linford

Non-invasive survey in the Stonehenge ‘Triangle’, Amesbury, Wiltshire, has highlighted a number of features that have a significant bearing on the interpretation of the site. Geophysical anomalies may signal the position of buried stones adding to the possibility of former stone arrangements, while laser scanning has provided detail on the manner in which the stones have been dressed; some subsequently carved with axe and dagger symbols. The probability that a lintelled bluestone trilithon formed an entrance in the north-east is signposted. This work has added detail that allows discussion on the question of whether the sarsen circle was a completed structure, although it is by no means conclusive in this respect. Instead, it is suggested that it was built as a façade, with other parts of the circuit added and with an entrance in the south.

Martyn Barber

Non-invasive survey in the Stonehenge 'Triangle', Amesbury, Wiltshire, has highlighted a number of features that have a significant bearing on the interpretation of the site. Geophysical anomalies may signal the position of buried stones adding to the possibility of former stone arrangements, while laser scanning has provided detail on the manner in which the stones have been dressed; some subsequently carved with dagger and axe symbols. The probability that a lintelled bluestone trilithon formed an entrance in the north-east is highlighted. This work has added detail that allows discussion on whether the sarsen circle was a completed structure, although it is by no means conclusive in this respect. Instead, it is suggested that it was built as a facade, with other parts of the circuit added and with an entrance in the south.

Didier Laroche

Interpretation of Stonehenge as a burial tumulus

Emilia Hawthorne

Joshua Pollard

Paper read to the 5th International Conference European Society for the History of Science, Athens, Greece, Nov

Vance Tiede

mike parker pearson

Stonehenge is one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments, built 4,500–5,000 years ago during the Neolithic in a time long before written history. The recent dramatic discovery of a dismantled stone circle near the sources of some of Stonehenge’s stones in southwest Wales raises the fascinating possibility that an ancient story about Stonehenge’s origin, written down 900 years ago and subsequently dismissed as pure invention, might contain a grain of truth. This article explores the pros and cons of comparing the legend with the archaeological evidence.

Timothy Darvill

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Anastasia Hassiotis

Lionel Sims

Paul Burley

The International Journal of Critical Cultural Studies

Tessa Morrison

Queensland Archaeological Research

Graham KNUCKEY

[email protected] W MacKie

Mike Parker Pearson

Robert Ixer

Peter Topping , Hugo Anderson-Whymark , Caroline Hardie

Roy Loveday

Christie Willis

David Roberts , Fay Worley , Andy Valdez-Tullett , Barry Bishop

Janet Montgomery

Journal of Material Culture 11 (1-2)

Umberto Albarella

Golden Meteorite Press

Austin A Mardon

Julian Thomas

Harry Sivertsen

The Purpose of Stonehenge

Michael Goormachtigh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Stonehenge : making sense of a Prehistoric mystery

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

3 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station54.cebu on November 2, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Stonehenge and its Landscape

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2014

- pp 1223–1238

- Cite this reference work entry

- Clive L. N. Ruggles 2

1001 Accesses

2 Altmetric

In the 1960s and 1970s, Stonehenge polarized academic opinion between those (mainly astronomers) who claimed it demonstrated great astronomical sophistication and those (mainly archaeologists) who denied it had anything to do with astronomy apart from the solstitial alignment of its main axis. Now, several decades later, links to the annual passage of the sun are generally recognized as an essential part of the function and meaning not only of Stonehenge but also of several other nearby monuments, giving us important insights into beliefs and actions relating to the seasonal cycle by the prehistoric communities who populated this chalkland landscape in the third millennium BC Links to the moon remain more debatable.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Land- and Skyscapes of Hegra: An Archaeoastronomical Analysis of the Nabataean Necropoleis

Goethe’s Italian Journey and the Geological Landscape

Lawrence Durrell’s Mediterranean Shores: Tropisms of a Receding Line

Abbott M, Anderson-Whymark H, with Aspden D, Badcock A, Davies T, Felter M, Ixer R, Parker Pearson M, Richards C (2012) Stonehenge laser scan: archaeological analysis report. English Heritage, Swindon. http://services.english-heritage.org.uk/ResearchReportsPdfs/032_2012web.pdf . Accessed 10 Oct 2012

Albarella U, Serjeantson D (2002) A passion for pork: meat consumption at the British Late Neolithic site of Durrington Walls. In: Miracle P, Milner N (eds) Consuming passions and patterns of consumption. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, pp 33–49

Google Scholar

Allen MJ (1995) Mesolithic features in the car park. In: Cleal RMJ, Walker KE, Montage R (eds) Stonehenge in its landscape: twentieth-century excavations. English Heritage, London, pp 43–47

Atkinson RJC (1956) Stonehenge. Hamish Hamilton, London

Atkinson RJC (1966) Moonshine on Stonehenge. Antiquity 40:212–216

Burl HAW (1987) The Stonehenge people. Dent, London

Burl HAW (1994) Stonehenge: slaughter, sacrifice and sunshine. Wilts Archaeol Nat Hist Mag 87:85–95

Chippindale C (1983) Stonehenge complete. Thames and Hudson, London

Cleal RMJ, Walker KE, Montage R (1995) Stonehenge in its landscape: twentieth-century excavations. English Heritage, London

Cunnington ME (1929) Woodhenge. George Simpson, Devizes

Darvill T (2005) Stonehenge world heritage site: an archaeological research framework. English Heritage and Bournemouth University, London/Bournemouth

Darvill T, Wainwright G (2009) Stonehenge excavations 2008. Antiq J 89:1–19

Article Google Scholar

Darvill T, Marshall P, Parker Pearson M, Wainwright G (2012) Stonehenge remodelled. Antiquity 86:1021–1040

French C, Scaife R, Allen MJ (2012) Durrington walls to west Amesbury by way of Stonehenge: a major transformation of the Holocene landscape. Antiq J 92:1–36

Gaffney C, Gaffney V, Neubauer W, Baldwin E, Chapman H, Garwood P, Moulden H, Sparrow T, Bates R, Löcker K, Hinterleitner A, Trinks I, Nau E, Zitz T, Floery S, Verhoeven G, Doneus M (2012) The Stonehenge hidden landscapes project. Archaeological Prospection 19(2):147–155

Hawkins GS, White JB (1965) Stonehenge decoded. Doubleday, New York

Heggie DC (1981) Megalithic science: ancient mathematics and astronomy in northwest Europe. Thames and Hudson, London

Hoskin MA (2001) Tombs, temples and their orientations. Ocarina Books, Bognor Regis

Hoyle F (1966) Speculations on Stonehenge. Antiquity 40:262–276

Parker Pearson M (2005) English Heritage book of Bronze Age Britain, revised edn. Batsford/English Heritage, London

Parker Pearson M (2012) Stonehenge: exploring the greatest Stone Age mystery. Simon and Schuster, London

Parker Pearson M, Ramilisonina (1998) Stonehenge for the ancestors: the stones pass on the message. Antiquity 72:308–326

Parker Pearson M, Pollard J, Tilley C, Thomas J, Richards C, Welham K (2005) The Stonehenge Riverside project: interim report. http://www.shef.ac.uk/content/1/c6/02/21/27/PDF-Interim-Report-2005.pdf . Accessed 28 Jan 2013

Parker Pearson M, Pollard J, Richards C, Thomas J, Tilley C, Welham K, Albarella U (2006) Materializing Stonehenge: the Stonehenge Riverside Project and new discoveries. Journal of Material Culture 11:227–261

Parker Pearson M, Cleal RMJ, Marshall P, Needham S, Pollard J, Richards C, Ruggles CLN, Sheridan S, Thomas J, Tilley C, Welham K, Chamberlain A, Chenery C, Evans J, Knüsel C, Linford N, Martin L, Montgomery J, Payne A, Richards M (2007) The age of Stonehenge. Antiquity 81:617–639

Parker Pearson M, Pollard J, Thomas J, Welham K (2010) Newhenge. Br Archaeol 110. http://www.archaeologyuk.org/ba/ba110/feat1.shtml . Accessed 2 Jan 2013

Pásztor E, Juhász A, Dombi M, Roslund C (2000) Computer Simulation of Stonehenge. In: Barceló JA, Forte M, Sanders DH (eds) Virtual reality in archaeology. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 111–113, BAR International Series 843

Pitts MW (1981) The discovery of a new stone at Stonehenge. Archaeoastronomy Bull Center Archaeoastronomy 4(2):16–21

Pollard J (1995) The Durrington 68 timber circle: a forgotten Late Neolithic monument. Wilts Archaeol Nat Hist Mag 88:122–125

Pollard J, Ruggles CLN (2001) Shifting perceptions: spatial order, cosmology, and patterns of deposition at Stonehenge. Camb Archaeol J 11(1):69–90

Pollard J, Robinson D, Wickstead H (2007) South of Woodhenge: an interim report on the 2007 excavations. Art Archaeol. http://www.artistsinarchaeology.org/assets/publications/Pollard_et_al_2007.pdf . Accessed 2 Jan 2013

RCHME (1979) Stonehenge and its environs. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Richards JC (1991) English Heritage book of Stonehenge. Batsford/English Heritage, London

Richards JC, Whitby M (1997) The engineering of Stonehenge. In: Cunliffe BW, Renfrew AC (eds) Science and Stonehenge. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 231–256

Ruggles CLN (1997) Astronomy and Stonehenge. In: Cunliffe BW, Renfrew AC (eds) Science and Stonehenge. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 203–229

Ruggles CLN (1999) Astronomy in prehistoric Britain and Ireland. Yale University Press, New Haven

Ruggles CLN (2006) Interpreting solstitial alignments in Late Neolithic Wessex. Archaeoastronomy J Astron Culture 20:1–27

Ruggles CLN (2014a) The orientation of the Stonehenge avenue and its implications. In: Parker Pearson M (ed) The Stonehenge Riverside Project, vol 1. Research papers series. Prehistoric Society, London (in press)

Ruggles CLN (2014b) The orientation and astronomical potential of the timber monuments at Durrington Walls and south of Woodhenge. In: Parker Pearson M (ed) The Stonehenge Riverside Project, vol 2. Research papers series. Prehistoric Society, London (in press)

Souden D (1997) Stonehenge: mysteries of the stones and landscape. English Heritage, London

Thom A, Thom AS, Thom A (1975) Stonehenge as a possible lunar observatory. J Hist Astron 6:19–30

ADS Google Scholar

Wainwright GJ, Longworth IH (1971) Durrington Walls: excavations 1966–1968. Society of Antiquaries, London

Young C, Chadburn A, Bedu I (2009) Stonehenge world heritage site management plan 2009. English Heritage, London

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK

Clive L. N. Ruggles

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Clive L. N. Ruggles .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Archaeology & Ancient History, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

Clive L.N. Ruggles

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Ruggles, C.L.N. (2015). Stonehenge and its Landscape. In: Ruggles, C. (eds) Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_118

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_118

Published : 07 July 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-6140-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-6141-8

eBook Packages : Physics and Astronomy Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Chemistry, Materials and Physics

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Solving the mysteries surrounding Stonehenge

- Culture and Communication

We’ve helped re-write the history of one of the world’s most famous prehistoric monuments – Stonehenge.

For centuries scientists and historians have argued over the meaning and purpose of Stonehenge.

Now a research team, which included staff from our Departments of Archaeology and Chemistry, believes it has finally solved many of the mysteries surrounding Stonehenge.

The team of experts has overturned the accepted view on what happened when Stonehenge was built, and why it was constructed.

Uniting Britain

The findings provide compelling evidence that Stonehenge once united the people of Britain.

They research revealed that the first stones at Stonehenge were put up 500 years earlier than previously thought at around 3000 BC and that the monument we see today was not the original Stonehenge.

The team has also come up with an explanation for the choice of site on Salisbury Plain and proved that Stonehenge was once the site of vast communal feasts attended by some 4,000 people - a substantial proportion of the British population at the time.

Pottery analysis

Researchers from York played a key role in analysing pottery from the site to support the idea of vast communal feasting to celebrate the solstice.

Dr Oliver Craig, from our Department of Archaeology, said: “Our role was to undertake chemical analysis of the pottery vessels scattered across the site of Durrington Walls to determine their contents. It was the largest study of its kind performed at a single site and was principally carried out by Dr Lisa Marie Shillito at our BioArCh facility in York but also involved members of the Department of Chemistry.

“We were able to reconcile different uses of pottery across the site to investigate culinary and consumption activities associated with the use of the public (monumental) and domestic (household) spaces. The results support the broader picture of widespread possible seasonal feasting - largely meat based- at this site.”

The research was led by Professor Mike Parker Pearson from University College London and involved researchers from universities across the UK.

Posted on 6 January 2015

The text of this article is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence . You're free to republish it, as long as you link back to this page and credit us.

Our results support a picture of widespread seasonal feasting - largely meat-based.” Dr Oliver Craig Director of the BioArCh in the Department of Archaeology

Featured researcher

Oliver Craig

Reader in Archaeological Science and Director of BioArCh

With a first degree in Biochemistry and Genetics from Nottingham, and an MSc in Osteology, Palaeopathology and Funerary Archaeology (Sheffield), he took a PhD with the Ancient Biomolecules group at Newcastle.

View profile

Discover the details

Find out more in the York Research Database and beyond

Visit the departments

- Archaeology

- BioArCh facility

Related stories

- Treespotting

- The future of teacher selection?

- Material gains

- All that jazz

Explore more research

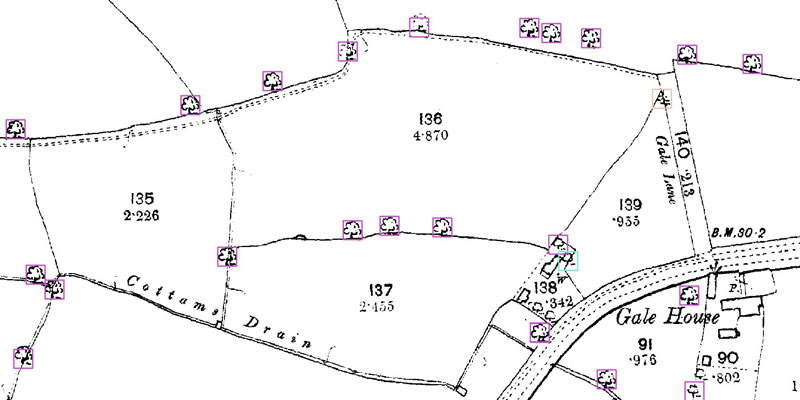

Treespotting: past, present and future

A research project needed to spot trees on historic ordnance survey maps, so colleagues in computer science found a solution.

Posted on 4 April 2024

Could TeachQuest! Be the future of teacher selection?

We’re using gaming technology to ensure prospective teachers are fully prepared for their careers.

Posted on 19 July 2023

Healthcare comes home

A low cost, high-accuracy device, could play a large part in the NHS's 'virtual wards'.

Posted on 13 June 2023

York science at the heart of ambitious fusion energy bid

York scientists are at the centre of an ambitious bid to bring low carbon fusion energy to Yorkshire.

Posted on 2 February 2022

Knowledge Exchange

Find out how we share our research knowledge.

York Research Database

Search for research and explore connections.

Research events

We showcase our research and encourage debate.

Home » Introduction

Introduction

Management plans and research frameworks, review of the existing frameworks, recent research, the new research framework, aims and objectives, consultation, geographical scope, resource assessment, research agenda and research strategy, research agenda, research strategy.

- The New Research Framework’s ...

Radiocarbon Dates

by Matt Leivers, Andrew B. Powell, Melanie Pomeroy-Kellinger and Sarah Simmonds

The Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site comprises two areas of Wessex chalkland, 40 km apart, surrounding Stonehenge and Avebury (Fig. 1), that are renowned for their distinctive complexes of Neolithic and Bronze Age sites. These sites have played a central role in the understanding of Britain’s prehistoric past and – together with their surrounding landscapes – have international significance, as recognised by the inscription of the World Heritage Site in 1986 on UNESCO’s World Heritage List for its Outstanding Universal Value .

Over the centuries, research into these sites and the landscapes they occupy has taken many forms and reached many and diverse conclusions: about the people who used them and about how, when and why they were constructed. Some of that research contributed to the degrading of the archaeological remains and it is the awareness that this finite resource needs to be effectively conserved which makes a framework for the facilitation and direction of sustainable research central to the management of the World Heritage Site (UNESCO 1972, Article 5).

UNESCO stresses the need for ‘serial’ World Heritage Sites comprising more than one area (such as Stonehenge and Avebury) to have ‘a management system or mechanisms for ensuring the co-ordinated management of the separate components’ (UNESCO 2013, para. 114). Although arguments have been advanced for the separation of Stonehenge and Avebury into separate World Heritage Sites, this possibility was ruled out in December 2007 when the Government announced that there would be no re- nomination of the World Heritage Site. The individual management plans – the Stonehenge World Heritage Site Management Plan 2009 (Young et al. 2009), and the Avebury World Heritage Site Management Plan (Pomeroy-Kellinger 2005) – have recently been replaced by a joint management plan for the whole World Heritage Site ( Stonehenge and Avebur y World Heritage Site Management Plan : Simmonds and Thomas 2015).

The two areas were also the subjects of separate research frameworks – Archaeological Research Agenda fo r the Avebury World Heritage Site (Avebury Archaeological and Historical Research Group 2001) and Stonehenge World Heritage Site: An Archaeological Research Framework (Darvill 2005).

The Avebury Research Agenda, published in 2001, was highly influential, being the first such document produced for any World Heritage Site. It was produced by the Avebury Archaeological and Historical Research Group (AAHRG), a group of professional curators, academics and freelance researchers who met to encourage, co-ordinate and disseminate research in the Avebury part of the World Heritage Site. A chronological and thematic approach was adopted in compiling the document, which consisted of individually-authored papers written by period and subject specialists.

The Stonehenge Research Framework published four years later, was a significantly different document, reflecting the rapidly evolving thinking about the role, format and content of archaeological research frameworks. It, too, was based on the contributions of individual specialists, but it was compiled and edited by a single hand giving it a greater consistency of style and content; it also benefited from the availability of considerably greater resources for mapping and illustration.

Both research frameworks followed the tripartite structure recommended in Frameworks For Our Past (Olivier 1996), a strategic review of research policies undertaken for English Heritage. Each comprised a period-based resource assessment describing the current state of knowledge about the archaeological resource in their respective areas, a research agenda pointing out areas of research which could help fill gaps in that knowledge, and a research strategy formulating proposals and priorities for carrying out such research. Despite their shared overall structure, the organisation and presentation of these three main sections differed considerably between the two documents. Nonetheless, both shared a strong emphasis on archaeology rather than the wider historic environment.

by Melanie Pomeroy-Kellinger

Research frameworks are temporary documents, providing a point-in-time view of the state of knowledge, priorities and strategies for research as envisaged at their compilation. In the introduction to the original Avebury agenda it was stated that the document would be updated on a regular basis as research was conducted and new discoveries made, and as research priorities evolved (AAHRG 2001, 4). Similarly, the need for reflexivity and revision was made explicit in the Stonehenge framework (Darvill 2005, 32) which was anticipated as being a statement of research issues and priorities for approximately a decade ( ibid ., 4).

Attempting to assess the relative success or failure of archaeological research frameworks is quite a challenging task. There are no agreed criteria for such an analysis, or a consensus on their value. There is a range of indicators which could be measured, such as how many research projects were undertaken, how many research questions were addressed, or how many new sites have been added to the Historic Environment Record (HER), but none of these are meaningful in isolation. In many ways it is easier to focus on what would constitute failure. In the case of the earlier documents for Avebury (AAHRG 2001) and Stonehenge (Darvill 2005), failure would mean that the documents were ignored and not used, which clearly has not been the case. The fact that there is presently a consensus that they need to be revised (and that funding has been obtained to undertake this process) can be seen as indicating a level of success.

The aims of both of the earlier documents were clearly set out (Avebury, section 1.3; Stonehenge section 1), and were similar: to actively encourage research into all periods, to improve understanding, to better inform other researchers, and to allow informed management to take place. Looking at the wide range of research and management projects undertaken since 2001 across both parts of the World Heritage Site, there is a good indication that many of these earlier aims have been addressed. There have been at least 10 major archaeological projects, and many other smaller ones, including the Silbury Hill project, SPACES, Negotiating Avebury, and others. These include both academic research and development-led projects, and both intrusive and non-intrusive fieldwork, and their results are outlined in the various sections of this document. It is apparent that the research frameworks have been referred to in fieldwork project designs, and indeed in bids for funding.

To what extent these projects would have been undertaken anyway, without the existence of the research frameworks, is difficult to assess; this was a subject of lively debate during a Research Agenda Workshop held in Devizes in June 2011. What is clear, however, is the large number of new discoveries, leading to the development of new theories and interpretations, which have resulted from these projects. In many ways they have led to a wider focus on the prehistoric landscapes surrounding the two iconic stone circles. With the media attention that has come with some of the discoveries, there is now a greater public appreciation of the complexity and significance of these landscapes. While many of these fieldwork projects have been published, it is anticipated that in the next few years a wealth of new information will become available.

Despite this, we know that the landscapes of Stonehenge and Avebury have not yet given up all of their secrets. However, what has been discovered in the last 10 years will help us to ask more detailed and complex questions in the future, and within the aims and objectives of this new, combined research framework. The discussions, debate and communication within the archaeological community resulting from the publication of the earlier documents and this revised version, will continue to be hugely beneficial to our understanding and management of these internationally significant landscapes.

Since 2001 major research has been undertaken in both parts of the World Heritage Site. This included survey, excavation and synthesis at Avebury and its surrounding monuments (Fig. 2), by a team from the Universities of Bristol, Leicester and Southampton (the Longstones and Negotiating Avebury projects) which had notable results, such as the discovery of the Beckhampton Avenue (Gillings et al. 2008). At Silbury Hill, English Heritage undertook con- servation, repair and excavation, and the Romano- British settlement was examined. The on-going Between the Monuments Project (a collaborative effort by the Universities of Southampton and Leicester and the National Trust) has been investigating the character of human settlement in the Avebury landscape during the 4th to mid-2nd millennia cal BC, and its relationship to changing environmental and social conditions.

At Stonehenge (Fig. 3) excavation was carried out in 2008 by the SPACES Project, while several well- known prehistoric monuments close to Stonehenge were investigated by the Stonehenge Riverside Project, which also discovered the West Amesbury Henge at the end of the Stonehenge Avenue on the bank of the River Avon as well as investigating Aubrey Hole 7 within Stonehenge itself. The Stonehenge World Heritage Site Landscape Project (English Heritage) involved non-invasive survey of the Stonehenge environs alongside documentary and archive research (Field et al. 2014a and b; Bowden et al. 2015). The Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes project (by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute, Birmingham University and international partners) has produced digital mapping of the Stonehenge landscape, revealing a wealth of previously-unknown sites via remote sensing and geophysical survey (Baldwin 2010; Gaffney et al. 2012).

Work on museum collections includes the Early Bronze Age Grave Goods Project by Birmingham University, and the Beaker People Project by the Universities of Sheffield, Durham and Bradford. Chronological modelling of the Stonehenge sequence has been revised (Marshall et al. 2012). Parch-marks observed during the dry summer of 2013 revealed the locations of missing sarsens 17–20 (Banton et al. 2014).

Practice-based research includes the publication of the surveys for the Highways Agency in advance of the proposed A303 road improvements (Leivers and Moore 2008), and further work associated with the new Stonehenge Visitor Centre, including the closure of the A344 and excavations on the line of the Avenue beneath it (Wessex Archaeology 2015).

The landscape of the entire World Heritage Site and its wider environs has now been mapped wice as part of the National Mapping Programme (NMP): in 1997–8 from all accessible aerial photographs, while in 2010–11 that mapping was further enhanced via the analysis of more recent reconnaissance photographs and of lidar data (Crutchley 2002; Bewley et al. 2005; Barber 2016, Avebury Resource Assessment).

by Sarah Simmonds

The path to the production of the Stonehenge and Avebury Research Framework has been a complex one. During the period of review and update of the Avebury Research Agenda (AAHRG 2001), which began in 2008, a number of key changes occurred in the management context. These led to the decision to combining the Avebury document with the more recently-produced Stonehenge Research Framework (Darvill 2005) in order to create a joint Stonehenge and Avebury Research Framework. The decision to produce a three-volume framework was influenced by a number of factors, particularly the challenge of combining two very differently-produced resource assessments. This continuing difference in approach to the two halves of the World Heritage Site was in part a result of the funding criteria in place during the development of the joint framework.

A fundamental change in the management context was triggered by the governance review of the World Heritage Site in 2012. The review recommended a more joined-up approach to the management of the two halves of the World Heritage Site, and this had a significant influence on the decision to produce the first joint World Heritage Site Management Plan for Stonehenge and Avebury, published in 2015 (Simmons and Thomas 2015). Reflecting the move to closer working across the World Heritage Site the Avebury Archaeological and Historical Research Group (AAHRG) was expanded in 2014 to include Stonehenge and become the Avebury and Stonehenge Archaeological and Historical Research Group (ASAHRG). The decision to produce a joint research framework for Stonehenge and Avebury is part of this movement towards a more integrated approach to the single World Heritage Site.

Funding criteria for the production of research frameworks over this period also influenced the three-part publication format. The process of updating the Avebury Research Agenda began in 2008 following a period of peer review and an online survey circulated widely among the academic community. A project outline was submitted to English Heritage on behalf of AAHRG based on the needs identified in the review and Wessex Archaeology was contracted to put together a detailed project design. Funding was agreed for new graphics and mapping and project management.

No funding was available for the production of the new Resource Assessment, which consequently led to this section again being produced by individuals on a voluntary basis. This approach provided the engagement of the academic community and in-kind contribution required by funders. An editorial committee made up of members of AAHRG was established at the end of 2009. The process of inviting contributors to update the resource assessment began in 2010.

The decision to produce a joint research framework for Stonehenge and Avebury – although very much in line with its recommendations – did in fact precede the outcomes of the World Heritage Site governance review. In mid-2010, revised English Heritage funding criteria meant that support was no longer available for updates to existing research frameworks and it appeared that the update of the Avebury Research Agenda could no longer be supported. The idea of producing a combined Stonehenge and Avebury Framework was suggested. In addition to producing a consistent approach to the single World Heritage Site this would also constitute a new publication that would be eligible for funding. Funding was secured for the production of a new joint agenda and strategy but it was decided that the resource assessments for the two halves would still be considered updates. The Avebury Resource Assessment therefore maintained the approach of securing updates from individual contributors, while a brief update of the relatively recent Stonehenge Framework would be produced by the single author (Tim Darvill) who had produced the 2005 Stonehenge Research Framework (Pl. 1). This approach was agreed by AAHRG who recognised both the necessity and the challenge of combining the two very different formats of resource assessment in a single joint framework.

Following completion of the Framework the project board decided to publish the Stonehenge and Avebury Research Framework in three parts to reflect the very different approach to production of the two resource assessments. The joint agenda and strategy section has been published as the third part of the Framework.

The new Framework is intended to cover the whole World Heritage Site, revising and updating the earlier documents. It is the result of consultation across the research community (in its broadest definition) and is intended to guide and inform future research activities in the historic environment and, in turn, its management and interpretation. The intention is that it will be underpinned by data-management systems that can be actively maintained as project-specific tools into the future. This new framework, therefore, fulfils a number of objectives:

- it provides revisions (redrafting and updating) of the existing Avebury and Stonehenge resource assessments, incorporating the 2008 boundary changes to the World Heritage Site, and explicitly expanding the focus from archaeology to the wider historic environment;

- it starts the process of harmonising and integrating the earlier separate research documents with the production for the first time of a single, combined research agenda and strategy for the whole World Heritage Site; and

- it develops a method to facilitate future review and revision. In future, this task will be undertaken by the Avebury and Stonehenge Archaeological and Historical Research Group (ASAHRG), which replaces AAHRG to promote and disseminate historical and archaeological research in the World Heritage Site as a whole.

Since the revised framework was first proposed, various forms of consultation have been undertaken as to its form and content. Named authors were invited to produce resource assessments and technical summaries; workshops and meetings guided the initial drafts of the Research Agenda; ASAHRG provided criticism of both. Drafts of these sections were presented for public consultation and comment via the internet, prior to further revision and comment by ASAHRG and Historic England. Following their finalisation, the Research Strategy was formulated based on their content, and the whole circulated for further comment. The entire process was guided by a Project Board.

In consequence, the new Research Framework offers a guide that reflects the priorities and encompasses the views of the widest possible community. It is in every sense a collaborative document, produced by and for the constituency of researchers working within the World Heritage Site.

One problem raised by the ‘serial’ nature of the World Heritage Site, comprising two relatively small areas of landscape separated by a distance of some 40 km, is that of determining the appropriate geographical scope for its research framework (Fig. 1). The boundaries of the two areas are largely arbitrary, although the development in them of notable complexes of monuments does distinguish them from much of the intervening (and surrounding) landscape. Nonetheless, the density of archaeological sites and monuments more widely across Salisbury Plain, the Vale of Pewsey (Pl. 2) and the downland around Avebury does mean that research into the World Heritage Site cannot be undertaken in isolation. Indeed, the presence of a henge at Marden of comparable size to those at Avebury and Durrington Walls (and approximately midway between them, Pl. 3), and of a mound at Marlborough comparable to Silbury Hill, as well as other monument complexes at a greater distance, such as in the Thames Valley and on Cranborne Chase, indicates that many of the questions which can be asked about the World Heritage Site can only be answered if consideration is given to a much wider area.

However, the World Heritage Site lies within, and close to the eastern edge of, the area covered by the South West Archaeological Research Framework (SWARF, Webster 2008), which is bordered to the east by that covered by the Solent Thames Research Framework (STRF, Hey and Hind 2014). Together these two frameworks cover all the Wessex chalkland, which defines the wider landscape occupied by the World Heritage Site. Although they encompass much larger areas than the present research framework, they articulate many of the broader research issues, of all periods, which are also of general relevance to the World Heritage Site. They also cover some specific issues relating to the Stonehenge and Avebury monumental landscapes, and the other monument complexes in their respective regions.

For these reasons, it has not been considered necessary to impose another arbitrarily defined ‘study area’ around the two areas of the World Heritage Site. Instead, this research framework keeps a close focus on the World Heritage Site, while recognising variable wider contexts as appropriate.

Although the new Research Framework covers the whole of the World Heritage Site, only its agenda and strategy sections have been fully integrated. Because the levels of revision considered appropriate for the two resource assessments differed so markedly, their integration was not considered possible at this stage. This framework therefore comprises a number of component parts.

Not only is there at present no overall resource assessment for the whole of the World Heritage Site, there also remain significant differences in the organisation and presentation of the current resource assessments for the Avebury and Stonehenge areas, as brought together here.

The 2005 resource assessment remains current, but it is supplemented by an update on research undertaken since then, Recent Research in the Stonehenge Landscape 2005–2012 , by the same author. This consists of summaries of development-prompted research and problem-orientated research, followed by a section looking at recently changed and changing aspects of research: dating, long-distance connections, landscape structure, and the relevance of other monuments.

This update is available on-line via this link

Avebury

The Avebury Resource Assessment has, for the most part, been completely re-written and expanded, and the new version replaces that contained in the 2001 document. As with the original Avebury Resource Assessment, individual authors provided papers on a voluntary basis, and not all conformed to the same template. In consequence, two (Romano-British and mid–late Saxon) are updates similar to that produced for Stonehenge, rather than full reassessments. In those instances, the original 2001 assessments have been included here for the sake of completeness. Most of the resource assessments were produced in 2011 and 2012, except for the sections covering environmental archaeology, GIS, the Iron Age, and modern Avebury, which date from 2013, the post- medieval and modern resource assessment, which dates from 2014, and the assessment of built heritage, which dates to 2015.

The resource assessment is split into two parts. The first, Methods of Research , provides cross-period assessments of the resource based on a number of specific research methods, old and new, which have been used to develop our understanding of the archaeology in the Avebury area. Descriptions of some of these methods, and in some cases assessments of the resource as revealed by them, were provided in Part 5: Methods and Techniques of the 2001 framework, as well as in a chapter on Palaeo- Environmental Evidence at the end of the original resource assessment.

The second part, Period-Based Assessments , represents to a large extent the complete replacement of the 2001 resource assessment. It now includes, however, papers on the Post-Medieval period, Built Heritage , and Modern Avebury , as well as separating the Middle and Late Bronze Age.

The new Research Agenda and Strategy cover for the first time both parts of the World Heritage Site. In the tripartite structure recommended by Olivier (1996), as followed by the earlier Avebury and Stonehenge frameworks, these two sections appear to have quite distinct roles, the agenda describing the gaps in our knowledge and the strategy proposing ways of filling those gaps. There is, however, a degree of overlap between them, since some research questions cannot be realistically addressed until others have been answered. Finding answers to some questions, therefore, becomes part of the strategy for answering other questions.

There have been a number of guiding principles in the compiling of the agenda and strategy. First, an attempt had been made to make the document recognisable, as far as possible, as a progression from the two earlier versions, despite their evident differences in approach, combining both thematic and period-based components. Secondly, consideration has been given to the need for it to be in a form suitable for future combined revision. Thirdly, as the agenda is intended to be a working document of use to a wide range of audiences, the objective has been to give it a relatively straightforward and transparent structure; what it may lack in theoretical and philosophical sophistication, it is hoped that it gains in clarity and usability.

The purpose of the agenda is to articulate the significant gaps in our understanding, by posing some of the outstanding questions in a form that is relevant to a number of chronological periods and major thematic subjects of relevance to the unique character of the World Heritage Site. The first part of the agenda outlines the themes which underlie the period-based questions described in the second. These questions are those generated during the process of workshops, consultation and comment outlined above.

There were significant differences in the structure and content of the two previous strategies. The Research Strategies in the original Avebury agenda comprised largely specific methodologies for answering specific questions, while the Research Strateg y in the Stonehenge document consisted more of an overarching plan, made up of a series of objectives under a number of broad thematic headings.

The new research strategy has a number of aims:

- to set out a framework of principles under which research should be carried out in the World Heritage Site; and

- to identify practical means by which such programmes of investigation can be facilitated, coordinated, resourced, sustained and communicated, and by which the research framework can be reviewed and updated.

After considerable discussion, it remained of particular concern to the Project Board and authors that the Research Strategy was not prescriptive. Consequently, it is a deliberate move away from a document which prioritises particular pieces of research, instead offering guidance designed to encourage innovative research which exceeds the requirements of ‘best practice’.

The New Research Framework’s Components

Although the individual parts of this present Research Framework document collectively cover the whole of the World Heritage Site, it remains an intermediate stage in the production of a fully integrated framework and is on its own a necessarily incomplete document. It needs to be read in conjunction with the 2005 Stonehenge framework particularly and, to a lesser degree, with the 2001 Avebury agenda. Although some elements of the original Avebury agenda have been completely re-written, the cumulative nature of archaeological research and the re-iterative nature of research frameworks mean that these superseded components still have a degree of currency and value. All relevant components of the past and present frameworks, therefore, will be accessible online at a single location on the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site website (http://www.stonehengeand aveburywhs.org/management-of-whs/stonehenge-ave bury-research-framework/).

The new Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites World Heritage Site Research Framework comprises the following main component parts:

Avebury Resource Assessment (Leivers and Powell 2016)

Stonehenge Resource Assessment (Section 2: Darvill 2005)

Stonehenge Update (on-line)

Avebury Resource Assessment (Part 1: AAHRG 2001) Research Agenda

Stonehenge and Avebury Research Agenda Avebury Research Agenda (Part 2: AAHRG 2001)

Stonehenge Research Agenda (Section 3: Darvill 2005)

Stonehenge and Avebury Research Strategy Avebury Research Strategy (Part 3: AAHRG 2001)

Stonehenge Research Strategy (Section 4: Darvill 2005)

Calibrated date ranges were calculated by the maximum intercept method (Stuiver and Reimer 1986), using the program OxCal v4.1 (Bronk Ramsey 1995; 1998; 2009) and the INTCAL09 dataset (Reimer et al. 2009). Ranges are rounded out to the nearest 10 years.

The lifecycle of this document is likely to be between five and ten years, parallel to the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site Management Plan and depending on the pace of research in the World Heritage Site. The progress of research will be monitored by ASAHRG, who will determine when a further revision is necessary. The next version of the Research Framework should fully integrate both parts of the World Heritage Site into a single document.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Speculation and excavation

- First stage: 3000–2935 bce

- Second stage: 2640–2480 bce

- Third stage: 2470–2280 bce

- Fourth, fifth, and sixth stages: 2280–1520 bce

- Stonehenge in the 21st century

Who built Stonehenge?

Was stonehenge built by aliens.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Smart History - Stonehenge

- English Heritage - History of Stonehenge

- World History Encyclopedia - Stonehenge, England, United Kingdom

- LiveScience - Where is Stonehenge, who built the prehistoric monument, and how?

- Humanities LibreTexts - Stonehenge

- Khan Academy - Stonehenge

- Stetson University - Neolithic Studies - Stonehenge stone circle, near Amesbury, Wiltshire, England

- Social Studies for Kids - Stonehenge is Still a Mystery

- Stonehenge - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Stonehenge - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

It is not clear who built Stonehenge. The site on Salisbury Plain in England has been used for ceremonial purposes and modified by many different groups of people at different times. Archaeological evidence suggests that the first modification of the site was made by early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers . DNA analysis of bodies buried near Stonehenge suggests that some of its builders may have come from places outside of England, such as Wales or the Mediterranean .

When was Stonehenge built?

The monument called Stonehenge was built in six stages between 3000 and 1520 BCE. The site was used for ceremonial purposes beginning about 8000–7000 BCE.

What is Stonehenge made of?

Stonehenge is constructed from sarsen stones, a type of silicified sandstone found in England, and bluestones , a dolomite variation extracted from western Wales.

What was Stonehenge used for?

There is debate surrounding the original purpose of Stonehenge. Previously thought to be a Druid temple, Stonehenge may instead be, according to researchers and others, a burial monument, a meeting place between chiefdoms, or even an astronomical “computer.”

Stonehenge was not built by aliens. The claim gained popularity by way of the book Chariots of the Gods? , published in 1968, in which its author, Erich von Däniken, claimed that many monuments, including Stonehenge, may have been built by extraterrestrials . Von Däniken’s claims and others like them have been debunked by scientists and other researchers.

Recent News

Stonehenge , prehistoric stone circle monument, cemetery, and archaeological site located on Salisbury Plain , about 8 miles (13 km) north of Salisbury , Wiltshire , England . Though there is no definite evidence as to the intended purpose of Stonehenge, it was presumably a religious site and an expression of the power and wealth of the chieftains, aristocrats , and priests who had it built—many of whom were buried in the numerous barrows close by. It was aligned on the Sun and possibly used for observing the Sun and Moon and working out the farming calendar. Or perhaps the site was dedicated to the world of the ancestors, separated from the world of the living, or was a healing centre. Whether it was used by the Druids ( Celtic priests) is doubtful, but present-day Druids gather there every year to hail the midsummer sunrise. Looking toward the sunrise, the entrance in the northeast points over a big pillar, now leaning at an angle, called the Heel Stone. Looking the other way, it points to the midwinter sunset. The summer solstice is also celebrated there by huge crowds of visitors.

Stonehenge was built in six stages between 3000 and 1520 bce , during the transition from the Neolithic Period (New Stone Age) to the Bronze Age . As a prehistoric stone circle, it is unique because of its artificially shaped sarsen stones (blocks of Cenozoic silcrete), arranged in post-and-lintel formation , and because of the remote origin of its smaller bluestones ( igneous and other rocks) from 100–150 miles (160–240 km) away, in South Wales. The name of the monument probably derives from the Saxon stan-hengen , meaning “stone hanging” or “gallows.” Along with more than 350 nearby monuments and henges (ancient earthworks consisting of a circular bank and ditch), including the kindred temple complex at Avebury , Stonehenge was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1986.

Stonehenge has long been the subject of historical speculation , and ideas about the meaning and significance of the structure continued to develop in the 21st century. English antiquarian John Aubrey in the 17th century and his compatriot archaeologist William Stukeley in the 18th century both believed the structure to be a Druid temple. This idea has been rejected by more-recent scholars, however, as Stonehenge is now understood to have predated by some 2,000 years the Druids recorded by Julius Caesar .

In 1963 American astronomer Gerald Hawkins proposed that Stonehenge had been constructed as a “computer” to predict lunar and solar eclipses; other scientists also attributed astronomical capabilities to the monument. Most of these speculations, too, have been rejected by experts. In 1973 English archaeologist Colin Renfrew hypothesized that Stonehenge was the centre of a confederation of Bronze Age chiefdoms. Other archaeologists, however, have since come to view this part of Salisbury Plain as a point of intersection between adjacent prehistoric territories, serving as a seasonal gathering place during the 4th and 3rd millennia bce for groups living in the lowlands to the east and west. In 1998 Malagasy archaeologist Ramilisonina proposed that Stonehenge was built as a monument to the ancestral dead, the permanence of its stones representing the eternal afterlife.

In 2008 British archaeologists Tim Darvill and Geoffrey Wainwright suggested—on the basis of the Amesbury Archer, an Early Bronze Age skeleton with a knee injury, excavated 3 miles (5 km) from Stonehenge—that Stonehenge was used in prehistory as a place of healing. However, analysis of human remains from around and within the monument shows no difference from other parts of Britain in terms of the population’s health.

The Stonehenge that is visible today is incomplete, many of its original sarsens and bluestones having been broken up and taken away, probably during Britain’s Roman and medieval periods. The ground within the monument also has been severely disturbed, not only by the removal of the stones but also by digging—to various degrees and ends—since the 16th century, when historian and antiquarian William Camden noted that “ashes and pieces of burnt bone” were found. A large, deep hole was dug within the stone circle in 1620 by George Villiers, 1st duke of Buckingham , who was looking for treasure . A century later William Stukeley surveyed Stonehenge and its surrounding monuments, but it was not until 1874–77 that Flinders Petrie made the first accurate plan of the stones. In 1877 Charles Darwin dug two holes in Stonehenge to investigate the earth-moving capabilities of earthworms . The first proper archaeological excavation was conducted in 1901 by William Gowland.

About half of Stonehenge (mostly on its eastern side) was excavated in the 20th century by the archaeologists William Hawley, in 1919–26, and Richard Atkinson, in 1950–78. The results of their work were not fully published until 1995, however, when the chronology of Stonehenge was revised extensively by means of carbon-14 dating . Major investigations in the early 21st century by the research team of the Stonehenge Riverside Project led to further revisions of the context and sequence of Stonehenge. Timothy Darvill and Geoffrey Wainwright ’s 2008 excavation was smaller but nonetheless important.

Stages of Stonehenge

Stonehenge was built within an area that was already special to Mesolithic and Neolithic people. About 8000–7000 bce , early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers dug pits and erected pine posts within 650 feet (200 metres) of Stonehenge’s future location. It was unusual for prehistoric hunter-gatherers to build monuments, and there are no comparable structures from this era in northwestern Europe. Within a 3-mile (5-km) radius of Stonehenge there remain from the Neolithic Period at least 17 long barrows (burial mounds) and two cursus monuments (long enclosures), all dating to the 4th millennium bce . Between 2200 and 1700 bce , during the Bronze Age, the Stonehenge-Durrington stretch of the River Avon was at the centre of a concentration of more than 1,000 round barrows on this part of Salisbury Plain.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

A New Story for Stonehenge

In the summer of 2019, I walked up a hillside in west Wales with Richard Bevins, a researcher who specializes in petrology, the study of the origins, compositions, and structures of rocks. We climbed through a landscape tufted with reeds. A drystone wall ran on our right. The territory opened into grassland, reaching up to a ridgeline etched against the sky. Our destination, Carn Goedog, jutted out above us. In Welsh, “carn” refers to a mound of rocks; “goedog” means full of trees. At close quarters, we could see that the rocks of Carn Goedog were dappled with lichen. I looked in vain for the feature that gave them their geologic name—spotted dolerite. “To see the spots, you have to get inside,” Bevins said.

Bevins and his collaborators believe that Carn Goedog is the source for a slew of the “bluestones” used to build the prehistoric monument Stonehenge, in southern England. Picture Stonehenge and you may first envision its huge standing stones, or sarsens. The bluestones are smaller; the biggest is a little less than ten feet tall, and weighs more than three tons. Around three dozen bluestones stand among the sarsens—there are different ways of counting—with more buried underground.

The rocks used for monuments like Stonehenge typically come from no more than a dozen miles away. Most of the sarsens have been traced to a part of the Marlborough Downs, fifteen miles from Stonehenge. But the distance between Stonehenge and Carn Goedog is a hundred and forty miles—roughly three and a half hours by car. If Bevins and his colleagues are right, then the bluestones had been transported much farther than any other material used for stone circles in Europe.

The mystery of the bluestones dates back to at least the seventeen-twenties. The antiquarian William Stukeley, an early authority on Stonehenge, wrote that, compared with the sarsens, the bluestones were “of a different sort,” and harder to place. The “provenancing” of the bluestones—the identification of their geographic source—began in earnest in 1923, when the geologist Herbert Henry Thomas posited that they had come originally from west Wales. Thomas had examined the light shown through thin slices of bluestone under a microscope and analyzed them alongside samples of rocks gathered in the field; he identified a number of outcroppings in the Preseli Hills, an area of rolling uplands close to the coast, as likely sources. In particular, Carn Alw, which is just under three-quarters of a mile from Carn Goedog, struck him as a particularly promising location. Until relatively recently, Thomas’s theory was regarded as canonical.

The revision began with a kind of social coincidence. In 2008, Bevins received an e-mail from a retired geologist named Rob Ixer, with whom he’d once provenanced a collection of axe-heads. Ixer was convinced that he’d stumbled upon a more accurate way to provenance the bluestones. Earlier that year, two archeologists, Tim Darvill and Geoff Wainwright, had conducted the first excavations inside Stonehenge in more than forty years, and asked Ixer to examine some of the thousands of stone fragments brought up to the surface. Around that time, Ixer happened to be speaking with another archeologist, Mike Parker Pearson, who’d mentioned that he had a shoebox full of similar bluestone fragments, which had been gathered in 1947. “He told me he had the shoebox under his desk and at his feet,” Ixer recalled. Parker Pearson sent the box—which had been lent to him by the Salisbury Museum, and essentially forgotten following a few studies a half century earlier—to Ixer. Inside were twelve fragments, the largest about four or five inches across. One was thought to be from a stone tool, made of sarsen rock; the others were bluestones that could not be traced to individual parts of the monument but which had clearly been brought to the Stonehenge site from somewhere else.

The work of provenancing has changed since Thomas’s time. Many petrologists have come to focus on the chemical analysis of rock fragments, comparing the mix of elements found within them. In their axe-heads paper, from 2004, Ixer and Bevins had argued for a more multifaceted approach. They maintained that, in addition to performing chemical analyses, petrologists should examine a rock’s appearance under a microscope, using both light shining through the rock—Thomas’s technique—and light reflecting off the opaque minerals on its surface. Ixer, therefore, had the shoebox fragments cut into sections thirty microns wide—thin enough for light to pass through. He reviewed them under a microscope, using both penetrating and reflective light.

Ixer was unable to make a connection between the shoebox fragments and any specific rocks in Wales. So he decided to e-mail Bevins. When Bevins examined the thin rock sections under a microscope, something in the way the light looked reminded him of samples that he had collected decades earlier, while doing his Ph.D. field work, in the nineteen-seventies. Back then, he’d collected a sample from Craig Rhos-y-felin, an outcropping at the foot of the Preseli Hills, a little north of where Thomas had thought the Stonehenge bluestones had come from. Bevins unearthed his old samples and had them sectioned, too. He found that those from Craig Rhos-y-felin matched five of the shoebox fragments.

It was “one of those eureka moments,” Bevins told me. The findings suggested that Thomas had identified the right general area but the wrong specific outcropping as the source of the bluestones. The fragments in the box, at least, had come not from Carn Alw but from Craig Rhos-y-felin. Thanks to new techniques, the question of the origins of the bluestones had been reopened.

Our understanding of Stonehenge has evolved with time. In the seventeenth century, the antiquarian John Aubrey linked the monument to pre-Roman Druids. In the eighteenth century, Stukeley recognized a relationship between the alignment of Stonehenge and the solstice, and attempted to demonstrate that the monument could not have been built by the Romans by taking a series of measurements which proved not to correspond to Roman units. More sophisticated investigations began in 1901, after William Gowland, a metallurgist and archeologist, was appointed to oversee excavations at the site. These uncovered no metal artifacts in the relevant layers of soil, confirming that Stonehenge was a Neolithic monument, built by early farmers in the last period of the Stone Age and the transition to the use of metal tools beginning in the Copper Age.