Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Understanding Scholarly/Academic Research

- What is Scholarly/Academic Research?

- Peer Review & Relevance

- Research Methodology

- Evaluating Online Sources

- What are Seminal Works?

- Impact Metrics

Librarian Team

Scholarly research articles or journals share these characteristics:

- scholarly works are considered unbiased within their discipline and are backed up with evidence

- are published in academic, scholarly, scientific or empirical journals

- reports on original research in a specific academic fields

- results are generalizable across populations

- use a research methodology that is replicable

- their authors are most often experts in the field and have their credentials listed

The structure of a scholarly article includes:

- a hypothesis: a proposed question

- a methods section

- conclusions

- suggestions for further research

- a citation reference list

All content in the library is credible, but not all of it is scholarly

These content formats are NOT scholarly

| editorials or book reviews | popular journals (e.g. non-expert author) |

| expert opinion articles | quality improvement research (QI) |

| trade or professional journal articles (e.g. applied science for the general public or professionals) | case studies that inform |

| site specific research (e.g. hospital based) | case studies resulting from evidence based practice or research |

- Next: Peer Review & Relevance >>

|

|

|

|

|

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 10:36 PM

- URL: https://libguides.americansentinel.edu/c.php?g=963648

- Brandeis Library

- Research Guides

- Evaluating Online Information

- Scholarly Works

Introduction

Things to consider, is it "scholarly", peer review, searching for peer reviewed articles, tips and tricks.

- Websites and Social Media

You're probably doing most of your academic research online, in library databases or on the open web. (Even if not, the tips on this page should still be useful to you.) That's great! But you still need to be careful that you're getting good sources, especially if you're on the open web. Luckily, the internet also makes it easier to evaluate the sources you find. Read on for some specific pointers...

- How current should a scholarly resource be? Use what you already know about your field and topic. Is it a rapidly changing field, like many sciences? Have there been major advances or shifts since the resource was published?

- Credentials aren't everything, but they're a good clue that an author is qualified to write/speak on a topic. Sometimes articles include a brief profile of the author; sometimes you have to look them up yourself.

- If it's peer reviewed, you already know that experts in the field gave their seal of approval. (See below for more on peer review.) But even experts can get things wrong! If the resource makes a surprising or extreme claim, it's good to check for reviews or rebuttals.

- Evaluating Articles

- Evaluating Books

What does "scholarly" mean? It generally refers to work that's the result of formal research, written by scholars in the field for other scholars. Scholarly works are usually peer-reviewed (see the box below), although the process works a little differently for books than for articles in journals. Scholarly works cite their sources thoroughly and can include bibliographies or lists of works cited, depending on the citation style used.

Magazines and scholarly journals are different , although they sometimes cover similar ground. The main differences: peer review and citing sources! This chart from NC State University Libraries will help you distinguish among them.

"Grey literature" refers to literature produced by government, academia, business, and industry outside of the commercial publishing process - things like government agency reports, NGO whitepapers, dissertations, and corporate annual reports. It can involve meticulous research, but doesn't go through the same editing and peer review process that, say, journal articles do. You can still evaluate it like other sources, though! If after evaluating a piece of grey lit, you'd like to use it in your work, (1) ask your professor if they consider it an acceptable source and/or (2) check the citations for leads on other resources.

What's peer review? In a nutshell, experts in a field check an article that's been submitted for publication to see if it meets scholarly standards. Watch this video for a 3-minute explanation of how it works. (Video produced by NC State University Libraries .)

[ Audio Transcript ]

View the slideshow below for tips on searching for peer-reviewed articles in OneSearch and in other major databases. (Click on the arrow on the side to get to the next slide.)

In OneSearch, run your search then click on the "Peer-Reviewed Journals" link on the left side to see only results from peer-reviewed journals.

EBSCO Databases

In an EBSCOhost database like Academic Search Premier, check the box on the left labeled "Scholarly (Peer-Reviewed) Journals".

Proquest Databases (before searching)

In a ProQuest database, you can check the box marked "Peer reviewed" before you run your search to get only peer reviewed resources back.

Proquest Databases (after searching)

Another option when searching ProQuest databases: run your search first, then use the "Peer reviewed" link on the side to filter for peer reviewed articles.

To find out more about a journal: If you're in one of the library's databases, you can usually click on the journal's name when you're viewing an article to learn more, including whether it's peer reviewed. For more, look through our research guide on Evaluating Journals .

To find out more about what other scholars think of a book: If you're looking at a book, chances are it's been reviewed. You can use the Book Review Index Plus database to locate reviews - search for the title and/or author, then click "GET IT" under the result(s) you're interested in to get the full text of the review.

...or an article: With an article, looking at other works that have cited it can be helpful. Try searching for your article's title in OneSearch , then clicking on "Cited by" in the lower right corner of the result. You can skim the resources that come up or Ctrl-F within them for your article's name to see if they're citing your article approvingly or negatively. If your article doesn't come up in OneSearch, try that process on Google Scholar instead.

When looking for peer reviewed articles , remember that they're also sometimes called "peer refereed" or just "scholarly" as synonyms.

- << Previous: Evaluating Online Information

- Next: News >>

- Last Updated: Aug 31, 2023 11:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.brandeis.edu/evaluatinginfo

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

A Scholar's Guide to Google

- Google Scholar

- Google Books

Using Google Scholar

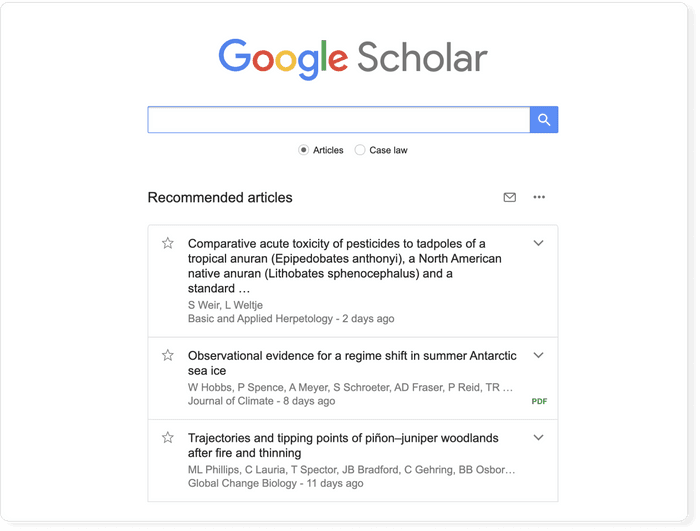

Google Scholar is a special version of Google specially designed for searching scholarly literature. It covers peer-reviewed papers, theses, books, preprints, abstracts and technical reports from all broad areas of research.

A Harvard ID and PIN are required for Google Scholar in order to access the full text of books, journal articles, etc. provided by licensed resources to which Harvard subscribes. Indviduals outside of Harvard may access Google Scholar directly at http://scholar.google.com/ , but they will not have access to the full text of articles provided by Harvard Library E-Resources .

Browsing Search Results

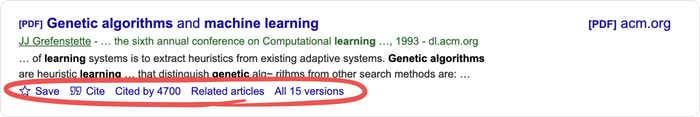

The following screenshots illustrate some of the features that accompany individual records in Google Scholar's results lists.

Find It@Harvard – Locates an electronic version of the work (when available) through Harvard's subscription library resources. If no electronic full text is available, a link to the appropriate HOLLIS Catalog record is provided for alternative formats.

Group of – Finds other articles included in this group of scholarly works, possibly preliminary, which you may be able to access. Examples include preprints, abstracts, conference papers or other adaptations.

Cited By – Identifies other papers that have cited articles in the group.

Related Articles - The list of related articles is ranked primarily by how similar these articles are to the original result, but also takes into account the relevance of each paper. Finding sets of related papers and books is often a great way for novices to get acquainted with a topic.

Cached - The "Cached" link is the snapshot that Google took of the page when they crawled the web. The page may have changed since that time and the cached page may reference images which are no longer available.

Web Search – Searches for information on the Web about this work using the Google search engine.

BL Direct – Purchase the full text of the article through the British Library. Once transferred into BL Direct, users can also link to the full collection of The British Library document supply content. Prices for the service are expressed in British pounds. Abstracts for some documents are provided.

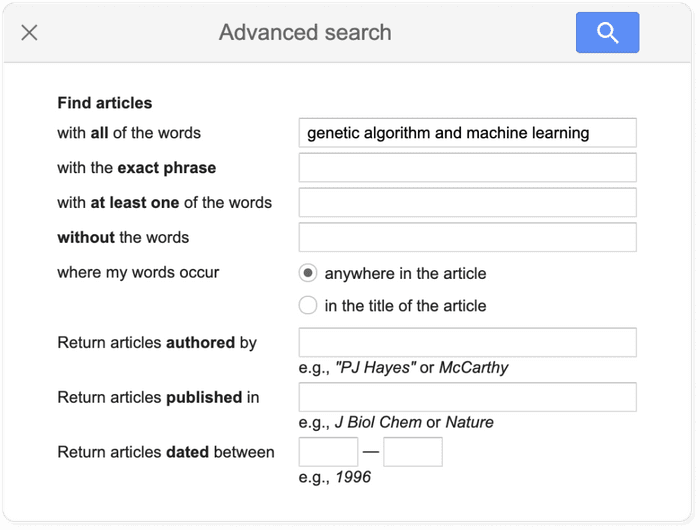

The Advanced Search feature in Google Scholar allows researchers to limit their query to particular authors, publications, dates, and subject areas.

Page Last Reviewed: February 25, 2008

- << Previous: Google Books

- Last Updated: Jun 8, 2017 1:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/googleguide

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Corrections

Search Help

Get the most out of Google Scholar with some helpful tips on searches, email alerts, citation export, and more.

Finding recent papers

Your search results are normally sorted by relevance, not by date. To find newer articles, try the following options in the left sidebar:

- click "Since Year" to show only recently published papers, sorted by relevance;

- click "Sort by date" to show just the new additions, sorted by date;

- click the envelope icon to have new results periodically delivered by email.

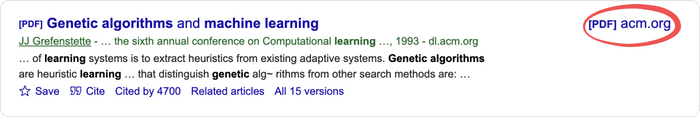

Locating the full text of an article

Abstracts are freely available for most of the articles. Alas, reading the entire article may require a subscription. Here're a few things to try:

- click a library link, e.g., "FindIt@Harvard", to the right of the search result;

- click a link labeled [PDF] to the right of the search result;

- click "All versions" under the search result and check out the alternative sources;

- click "Related articles" or "Cited by" under the search result to explore similar articles.

If you're affiliated with a university, but don't see links such as "FindIt@Harvard", please check with your local library about the best way to access their online subscriptions. You may need to do search from a computer on campus, or to configure your browser to use a library proxy.

Getting better answers

If you're new to the subject, it may be helpful to pick up the terminology from secondary sources. E.g., a Wikipedia article for "overweight" might suggest a Scholar search for "pediatric hyperalimentation".

If the search results are too specific for your needs, check out what they're citing in their "References" sections. Referenced works are often more general in nature.

Similarly, if the search results are too basic for you, click "Cited by" to see newer papers that referenced them. These newer papers will often be more specific.

Explore! There's rarely a single answer to a research question. Click "Related articles" or "Cited by" to see closely related work, or search for author's name and see what else they have written.

Searching Google Scholar

Use the "author:" operator, e.g., author:"d knuth" or author:"donald e knuth".

Put the paper's title in quotations: "A History of the China Sea".

You'll often get better results if you search only recent articles, but still sort them by relevance, not by date. E.g., click "Since 2018" in the left sidebar of the search results page.

To see the absolutely newest articles first, click "Sort by date" in the sidebar. If you use this feature a lot, you may also find it useful to setup email alerts to have new results automatically sent to you.

Note: On smaller screens that don't show the sidebar, these options are available in the dropdown menu labelled "Year" right below the search button.

Select the "Case law" option on the homepage or in the side drawer on the search results page.

It finds documents similar to the given search result.

It's in the side drawer. The advanced search window lets you search in the author, title, and publication fields, as well as limit your search results by date.

Select the "Case law" option and do a keyword search over all jurisdictions. Then, click the "Select courts" link in the left sidebar on the search results page.

Tip: To quickly search a frequently used selection of courts, bookmark a search results page with the desired selection.

Access to articles

For each Scholar search result, we try to find a version of the article that you can read. These access links are labelled [PDF] or [HTML] and appear to the right of the search result. For example:

A paper that you need to read

Access links cover a wide variety of ways in which articles may be available to you - articles that your library subscribes to, open access articles, free-to-read articles from publishers, preprints, articles in repositories, etc.

When you are on a campus network, access links automatically include your library subscriptions and direct you to subscribed versions of articles. On-campus access links cover subscriptions from primary publishers as well as aggregators.

Off-campus access

Off-campus access links let you take your library subscriptions with you when you are at home or traveling. You can read subscribed articles when you are off-campus just as easily as when you are on-campus. Off-campus access links work by recording your subscriptions when you visit Scholar while on-campus, and looking up the recorded subscriptions later when you are off-campus.

We use the recorded subscriptions to provide you with the same subscribed access links as you see on campus. We also indicate your subscription access to participating publishers so that they can allow you to read the full-text of these articles without logging in or using a proxy. The recorded subscription information expires after 30 days and is automatically deleted.

In addition to Google Scholar search results, off-campus access links can also appear on articles from publishers participating in the off-campus subscription access program. Look for links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] on the right hand side of article pages.

Anne Author , John Doe , Jane Smith , Someone Else

In this fascinating paper, we investigate various topics that would be of interest to you. We also describe new methods relevant to your project, and attempt to address several questions which you would also like to know the answer to. Lastly, we analyze …

You can disable off-campus access links on the Scholar settings page . Disabling off-campus access links will turn off recording of your library subscriptions. It will also turn off indicating subscription access to participating publishers. Once off-campus access links are disabled, you may need to identify and configure an alternate mechanism (e.g., an institutional proxy or VPN) to access your library subscriptions while off-campus.

Email Alerts

Do a search for the topic of interest, e.g., "M Theory"; click the envelope icon in the sidebar of the search results page; enter your email address, and click "Create alert". We'll then periodically email you newly published papers that match your search criteria.

No, you can enter any email address of your choice. If the email address isn't a Google account or doesn't match your Google account, then we'll email you a verification link, which you'll need to click to start receiving alerts.

This works best if you create a public profile , which is free and quick to do. Once you get to the homepage with your photo, click "Follow" next to your name, select "New citations to my articles", and click "Done". We will then email you when we find new articles that cite yours.

Search for the title of your paper, e.g., "Anti de Sitter space and holography"; click on the "Cited by" link at the bottom of the search result; and then click on the envelope icon in the left sidebar of the search results page.

First, do a search for your colleague's name, and see if they have a Scholar profile. If they do, click on it, click the "Follow" button next to their name, select "New articles by this author", and click "Done".

If they don't have a profile, do a search by author, e.g., [author:s-hawking], and click on the mighty envelope in the left sidebar of the search results page. If you find that several different people share the same name, you may need to add co-author names or topical keywords to limit results to the author you wish to follow.

We send the alerts right after we add new papers to Google Scholar. This usually happens several times a week, except that our search robots meticulously observe holidays.

There's a link to cancel the alert at the bottom of every notification email.

If you created alerts using a Google account, you can manage them all here . If you're not using a Google account, you'll need to unsubscribe from the individual alerts and subscribe to the new ones.

Google Scholar library

Google Scholar library is your personal collection of articles. You can save articles right off the search page, organize them by adding labels, and use the power of Scholar search to quickly find just the one you want - at any time and from anywhere. You decide what goes into your library, and we’ll keep the links up to date.

You get all the goodies that come with Scholar search results - links to PDF and to your university's subscriptions, formatted citations, citing articles, and more!

Library help

Find the article you want to add in Google Scholar and click the “Save” button under the search result.

Click “My library” at the top of the page or in the side drawer to view all articles in your library. To search the full text of these articles, enter your query as usual in the search box.

Find the article you want to remove, and then click the “Delete” button under it.

- To add a label to an article, find the article in your library, click the “Label” button under it, select the label you want to apply, and click “Done”.

- To view all the articles with a specific label, click the label name in the left sidebar of your library page.

- To remove a label from an article, click the “Label” button under it, deselect the label you want to remove, and click “Done”.

- To add, edit, or delete labels, click “Manage labels” in the left column of your library page.

Only you can see the articles in your library. If you create a Scholar profile and make it public, then the articles in your public profile (and only those articles) will be visible to everyone.

Your profile contains all the articles you have written yourself. It’s a way to present your work to others, as well as to keep track of citations to it. Your library is a way to organize the articles that you’d like to read or cite, not necessarily the ones you’ve written.

Citation Export

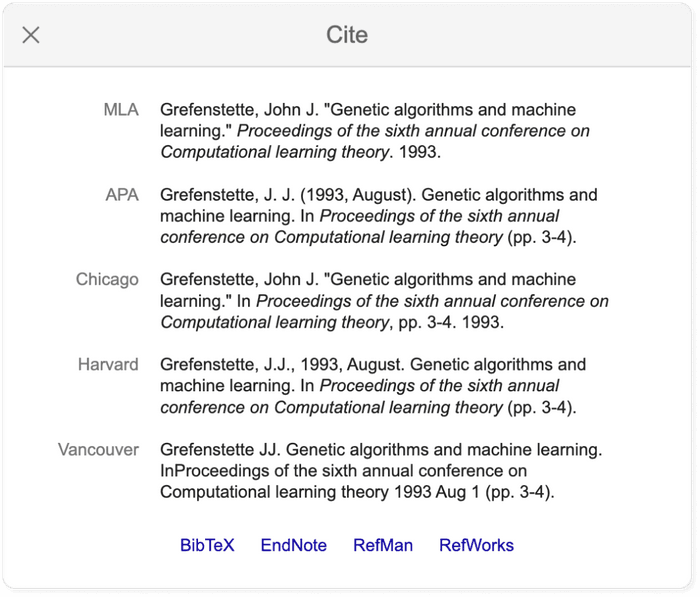

Click the "Cite" button under the search result and then select your bibliography manager at the bottom of the popup. We currently support BibTeX, EndNote, RefMan, and RefWorks.

Err, no, please respect our robots.txt when you access Google Scholar using automated software. As the wearers of crawler's shoes and webmaster's hat, we cannot recommend adherence to web standards highly enough.

Sorry, we're unable to provide bulk access. You'll need to make an arrangement directly with the source of the data you're interested in. Keep in mind that a lot of the records in Google Scholar come from commercial subscription services.

Sorry, we can only show up to 1,000 results for any particular search query. Try a different query to get more results.

Content Coverage

Google Scholar includes journal and conference papers, theses and dissertations, academic books, pre-prints, abstracts, technical reports and other scholarly literature from all broad areas of research. You'll find works from a wide variety of academic publishers, professional societies and university repositories, as well as scholarly articles available anywhere across the web. Google Scholar also includes court opinions and patents.

We index research articles and abstracts from most major academic publishers and repositories worldwide, including both free and subscription sources. To check current coverage of a specific source in Google Scholar, search for a sample of their article titles in quotes.

While we try to be comprehensive, it isn't possible to guarantee uninterrupted coverage of any particular source. We index articles from sources all over the web and link to these websites in our search results. If one of these websites becomes unavailable to our search robots or to a large number of web users, we have to remove it from Google Scholar until it becomes available again.

Our meticulous search robots generally try to index every paper from every website they visit, including most major sources and also many lesser known ones.

That said, Google Scholar is primarily a search of academic papers. Shorter articles, such as book reviews, news sections, editorials, announcements and letters, may or may not be included. Untitled documents and documents without authors are usually not included. Website URLs that aren't available to our search robots or to the majority of web users are, obviously, not included either. Nor do we include websites that require you to sign up for an account, install a browser plugin, watch four colorful ads, and turn around three times and say coo-coo before you can read the listing of titles scanned at 10 DPI... You get the idea, we cover academic papers from sensible websites.

That's usually because we index many of these papers from other websites, such as the websites of their primary publishers. The "site:" operator currently only searches the primary version of each paper.

It could also be that the papers are located on examplejournals.gov, not on example.gov. Please make sure you're searching for the "right" website.

That said, the best way to check coverage of a specific source is to search for a sample of their papers using the title of the paper.

Ahem, we index papers, not journals. You should also ask about our coverage of universities, research groups, proteins, seminal breakthroughs, and other dimensions that are of interest to users. All such questions are best answered by searching for a statistical sample of papers that has the property of interest - journal, author, protein, etc. Many coverage comparisons are available if you search for [allintitle:"google scholar"], but some of them are more statistically valid than others.

Currently, Google Scholar allows you to search and read published opinions of US state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950, US federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy courts since 1923 and US Supreme Court cases since 1791. In addition, it includes citations for cases cited by indexed opinions or journal articles which allows you to find influential cases (usually older or international) which are not yet online or publicly available.

Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

We normally add new papers several times a week. However, updates to existing records take 6-9 months to a year or longer, because in order to update our records, we need to first recrawl them from the source website. For many larger websites, the speed at which we can update their records is limited by the crawl rate that they allow.

Inclusion and Corrections

We apologize, and we assure you the error was unintentional. Automated extraction of information from articles in diverse fields can be tricky, so an error sometimes sneaks through.

Please write to the owner of the website where the erroneous search result is coming from, and encourage them to provide correct bibliographic data to us, as described in the technical guidelines . Once the data is corrected on their website, it usually takes 6-9 months to a year or longer for it to be updated in Google Scholar. We appreciate your help and your patience.

If you can't find your papers when you search for them by title and by author, please refer your publisher to our technical guidelines .

You can also deposit your papers into your institutional repository or put their PDF versions on your personal website, but please follow your publisher's requirements when you do so. See our technical guidelines for more details on the inclusion process.

We normally add new papers several times a week; however, it might take us some time to crawl larger websites, and corrections to already included papers can take 6-9 months to a year or longer.

Google Scholar generally reflects the state of the web as it is currently visible to our search robots and to the majority of users. When you're searching for relevant papers to read, you wouldn't want it any other way!

If your citation counts have gone down, chances are that either your paper or papers that cite it have either disappeared from the web entirely, or have become unavailable to our search robots, or, perhaps, have been reformatted in a way that made it difficult for our automated software to identify their bibliographic data and references. If you wish to correct this, you'll need to identify the specific documents with indexing problems and ask your publisher to fix them. Please refer to the technical guidelines .

Please do let us know . Please include the URL for the opinion, the corrected information and a source where we can verify the correction.

We're only able to make corrections to court opinions that are hosted on our own website. For corrections to academic papers, books, dissertations and other third-party material, click on the search result in question and contact the owner of the website where the document came from. For corrections to books from Google Book Search, click on the book's title and locate the link to provide feedback at the bottom of the book's page.

General Questions

These are articles which other scholarly articles have referred to, but which we haven't found online. To exclude them from your search results, uncheck the "include citations" box on the left sidebar.

First, click on links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] to the right of the search result's title. Also, check out the "All versions" link at the bottom of the search result.

Second, if you're affiliated with a university, using a computer on campus will often let you access your library's online subscriptions. Look for links labeled with your library's name to the right of the search result's title. Also, see if there's a link to the full text on the publisher's page with the abstract.

Keep in mind that final published versions are often only available to subscribers, and that some articles are not available online at all. Good luck!

Technically, your web browser remembers your settings in a "cookie" on your computer's disk, and sends this cookie to our website along with every search. Check that your browser isn't configured to discard our cookies. Also, check if disabling various proxies or overly helpful privacy settings does the trick. Either way, your settings are stored on your computer, not on our servers, so a long hard look at your browser's preferences or internet options should help cure the machine's forgetfulness.

Not even close. That phrase is our acknowledgement that much of scholarly research involves building on what others have already discovered. It's taken from Sir Isaac Newton's famous quote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

- Privacy & Terms

18 Google Scholar tips all students should know

Dec 13, 2022

[[read-time]] min read

Think of this guide as your personal research assistant.

“It’s hard to pick your favorite kid,” Anurag Acharya says when I ask him to talk about a favorite Google Scholar feature he’s worked on. “I work on product, engineering, operations, partnerships,” he says. He’s been doing it for 18 years, which as of this month, happens to be how long Google Scholar has been around.

Google Scholar is also one of Google’s longest-running services. The comprehensive database of research papers, legal cases and other scholarly publications was the fourth Search service Google launched, Anurag says. In honor of this very important tool’s 18th anniversary, I asked Anurag to share 18 things you can do in Google Scholar that you might have missed.

1. Copy article citations in the style of your choice.

With a simple click of the cite button (which sits below an article entry), Google Scholar will give you a ready-to-use citation for the article in five styles, including APA, MLA and Chicago. You can select and copy the one you prefer.

2. Dig deeper with related searches.

Google Scholar’s related searches can help you pinpoint your research; you’ll see them show up on a page in between article results. Anurag describes it like this: You start with a big topic — like “cancer” — and follow up with a related search like “lung cancer” or “colon cancer” to explore specific kinds of cancer.

Related searches can help you find what you’re looking for.

3. And don’t miss the related articles.

This is another great way to find more papers similar to one you found helpful — you can find this link right below an entry.

4. Read the papers you find.

Scholarly articles have long been available only by subscription. To keep you from having to log in every time you see a paper you’re interested in, Scholar works with libraries and publishers worldwide to integrate their subscriptions directly into its search results. Look for a link marked [PDF] or [HTML]. This also includes preprints and other free-to-read versions of papers.

5. Access Google Scholar tools from anywhere on the web with the Scholar Button browser extension.

The Scholar Button browser extension is sort of like a mini version of Scholar that can move around the web with you. If you’re searching for something, hitting the extension icon will show you studies about that topic, and if you’re reading a study, you can hit that same button to find a version you read, create a citation or to save it to your Scholar library.

Install the Scholar Button Chrome browser extension to access Google Scholar from anywhere on the web.

6. Learn more about authors through Scholar profiles.

There are many times when you’ll want to know more about the researchers behind the ideas you’re looking into. You can do this by clicking on an author’s name when it’s hyperlinked in a search result. You’ll find all of their work as well as co-authors, articles they’re cited in and so on. You can also follow authors from their Scholar profile to get email updates about their work, or about when and where their work is cited.

7. Easily find topic experts.

One last thing about author profiles: If there are topics listed below an author’s name on their profile, you can click on these areas of expertise and you’ll see a page of more authors who are researching and publishing on these topics, too.

8. Search for court opinions with the “Case law” button.

Scholar is the largest free database of U.S. court opinions. When you search for something using Google Scholar, you can select the “Case law” button below the search box to see legal cases your keywords are referenced in. You can read the opinions and a summary of what they established.

9. See how those court opinions have been cited.

If you want to better understand the impact of a particular piece of case law, you can select “How Cited,” which is below an entry, to see how and where the document has been cited. For example, here is the How Cited page for Marbury v. Madison , a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that established that courts can strike down unconstitutional laws or statutes.

10. Understand how a legal opinion depends on another.

When you’re looking at how case laws are cited within Google Scholar, click on “Cited by” and check out the horizontal bars next to the different results. They indicate how relevant the cited opinion is in the court decision it’s cited within. You will see zero, one, two or three bars before each result. Those bars indicate the extent to which the new opinion depends on and refers to the cited case.

In the Cited by page for New York Times Company v. Sullivan, court cases with three bars next to their name heavily reference the original case. One bar indicates less reliance.

11. Sign up for Google Scholar alerts.

Want to stay up to date on a specific topic? Create an alert for a Google Scholar search for your topics and you’ll get email updates similar to Google Search alerts. Another way to keep up with research in your area is to follow new articles by leading researchers. Go to their profiles and click “Follow.” If you’re a junior grad student, you may consider following articles related to your advisor’s research topics, for instance.

12. Save interesting articles to your library.

It’s easy to go down fascinating rabbit hole after rabbit hole in Google Scholar. Don’t lose track of your research and use the save option that pops up under search results so articles will be in your library for later reading.

13. Keep your library organized with labels.

Labels aren’t only for Gmail! You can create labels within your Google Scholar library so you can keep your research organized. Click on “My library,” and then the “Manage labels…” option to create a new label.

14. If you’re a researcher, share your research with all your colleagues.

Many research funding agencies around the world now mandate that funded articles should become publicly free to read within a year of publication — or sooner. Scholar profiles list such articles to help researchers keep track of them and open up access to ones that are still locked down. That means you can immediately see what is currently available from researchers you’re interested in and how many of their papers will soon be publicly free to read.

15. Look through Scholar’s annual top publications and papers.

Every year, Google Scholar releases the top publications based on the most-cited papers. That list (available in 11 languages) will also take you to each publication’s top papers — this takes into account the “h index,” which measures how much impact an article has had. It’s an excellent place to start a research journey as well as get an idea about the ideas and discoveries researchers are currently focused on.

16. Get even more specific with Advanced Search.

Click on the hamburger icon on the upper left-hand corner and select Advanced Search to fine-tune your queries. For example, articles with exact words or a particular phrase in the title or articles from a particular journal and so on.

17. Find extra help on Google Scholar’s help page.

It might sound obvious, but there’s a wealth of useful information to be found here — like how often the database is updated, tips on formatting searches and how you can use your library subscriptions when you’re off-campus (looking at you, college students!). Oh, and you’ll even learn the origin of that quote on Google Scholar’s home page.

18. Keep up with Google Scholar news.

Don’t forget to check out the Google Scholar blog for updates on new features and tips for using this tool even better.

Related stories

4 Google updates coming to Samsung devices

Maisie from Washington, D.C. is our 2024 Doodle for Google winner

4 ways to find great prices on Google during summer sales

Use these 5 AI-powered tools to plan your summer travel

Check out this year’s 5 Doodle for Google finalists

Ai overviews: about last week.

Here’s what happened with AI Overviews, the feedback we've received, and the steps we’ve taken.

Let’s stay in touch. Get the latest news from Google in your inbox.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Google Scholar: the ultimate guide

What is Google Scholar?

Why is google scholar better than google for finding research papers, the google scholar search results page, the first two lines: core bibliographic information, quick full text-access options, "cited by" count and other useful links, tips for searching google scholar, 1. google scholar searches are not case sensitive, 2. use keywords instead of full sentences, 3. use quotes to search for an exact match, 3. add the year to the search phrase to get articles published in a particular year, 4. use the side bar controls to adjust your search result, 5. use boolean operator to better control your searches, google scholar advanced search interface, customizing search preferences and options, using the "my library" feature in google scholar, the scope and limitations of google scholar, alternatives to google scholar, country-specific google scholar sites, frequently asked questions about google scholar, related articles.

Google Scholar (GS) is a free academic search engine that can be thought of as the academic version of Google. Rather than searching all of the indexed information on the web, it searches repositories of:

- universities

- scholarly websites

This is generally a smaller subset of the pool that Google searches. It's all done automatically, but most of the search results tend to be reliable scholarly sources.

However, Google is typically less careful about what it includes in search results than more curated, subscription-based academic databases like Scopus and Web of Science . As a result, it is important to take some time to assess the credibility of the resources linked through Google Scholar.

➡️ Take a look at our guide on the best academic databases .

One advantage of using Google Scholar is that the interface is comforting and familiar to anyone who uses Google. This lowers the learning curve of finding scholarly information .

There are a number of useful differences from a regular Google search. Google Scholar allows you to:

- copy a formatted citation in different styles including MLA and APA

- export bibliographic data (BibTeX, RIS) to use with reference management software

- explore other works have cited the listed work

- easily find full text versions of the article

Although it is free to search in Google Scholar, most of the content is not freely available. Google does its best to find copies of restricted articles in public repositories. If you are at an academic or research institution, you can also set up a library connection that allows you to see items that are available through your institution.

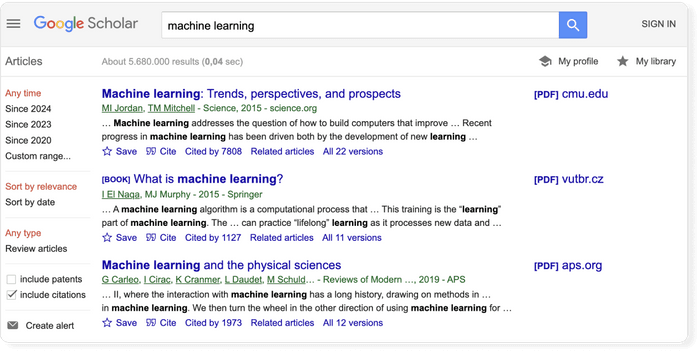

The Google Scholar results page differs from the Google results page in a few key ways. The search result page is, however, different and it is worth being familiar with the different pieces of information that are shown. Let's have a look at the results for the search term "machine learning.”

- The first line of each result provides the title of the document (e.g. of an article, book, chapter, or report).

- The second line provides the bibliographic information about the document, in order: the author(s), the journal or book it appears in, the year of publication, and the publisher.

Clicking on the title link will bring you to the publisher’s page where you may be able to access more information about the document. This includes the abstract and options to download the PDF.

To the far right of the entry are more direct options for obtaining the full text of the document. In this example, Google has also located a publicly available PDF of the document hosted at umich.edu . Note, that it's not guaranteed that it is the version of the article that was finally published in the journal.

Below the text snippet/abstract you can find a number of useful links.

- Cited by : the cited by link will show other articles that have cited this resource. That is a super useful feature that can help you in many ways. First, it is a good way to track the more recent research that has referenced this article, and second the fact that other researches cited this document lends greater credibility to it. But be aware that there is a lag in publication type. Therefore, an article published in 2017 will not have an extensive number of cited by results. It takes a minimum of 6 months for most articles to get published, so even if an article was using the source, the more recent article has not been published yet.

- Versions : this link will display other versions of the article or other databases where the article may be found, some of which may offer free access to the article.

- Quotation mark icon : this will display a popup with commonly used citation formats such as MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard, and Vancouver that may be copied and pasted. Note, however, that the Google Scholar citation data is sometimes incomplete and so it is often a good idea to check this data at the source. The "cite" popup also includes links for exporting the citation data as BibTeX or RIS files that any major reference manager can import.

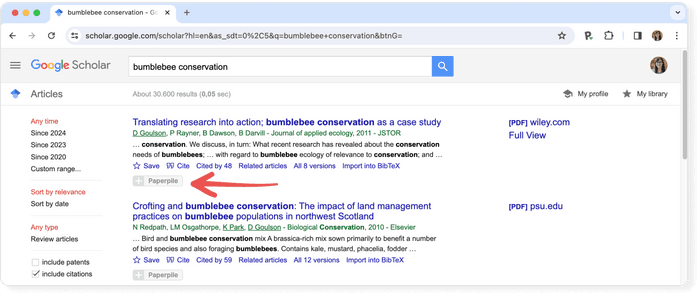

Pro tip: Use a reference manager like Paperpile to keep track of all your sources. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular academic research engines and databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons and later cite them in thousands of citation styles:

Although Google Scholar limits each search to a maximum of 1,000 results , it's still too much to explore, and you need an effective way of locating the relevant articles. Here’s a list of pro tips that will help you save time and search more effectively.

You don’t need to worry about case sensitivity when you’re using Google scholar. In other words, a search for "Machine Learning" will produce the same results as a search for "machine learning.”

Let's say your research topic is about self driving cars. For a regular Google search we might enter something like " what is the current state of the technology used for self driving cars ". In Google Scholar, you will see less than ideal results for this query .

The trick is to build a list of keywords and perform searches for them like self-driving cars, autonomous vehicles, or driverless cars. Google Scholar will assist you on that: if you start typing in the search field you will see related queries suggested by Scholar!

If you put your search phrase into quotes you can search for exact matches of that phrase in the title and the body text of the document. Without quotes, Google Scholar will treat each word separately.

This means that if you search national parks , the words will not necessarily appear together. Grouped words and exact phrases should be enclosed in quotation marks.

A search using “self-driving cars 2015,” for example, will return articles or books published in 2015.

Using the options in the left hand panel you can further restrict the search results by limiting the years covered by the search, the inclusion or exclude of patents, and you can sort the results by relevance or by date.

Searches are not case sensitive, however, there are a number of Boolean operators you can use to control the search and these must be capitalized.

- AND requires both of the words or phrases on either side to be somewhere in the record.

- NOT can be placed in front of a word or phrases to exclude results which include them.

- OR will give equal weight to results which match just one of the words or phrases on either side.

➡️ Read more about how to efficiently search online databases for academic research .

In case you got overwhelmed by the above options, here’s some illustrative examples:

| Example queries | When to use and what will it do? |

|---|---|

"alternative medicine" | Multiword concepts like are best searched as an exact phrase match. Otherwise, Google Scholar will display results that contain and/or . |

"The wisdom of the hive: the social physiology of honey bee colonies" | If you are looking for a particular article and know the title, it is best to put it into quotes to look for an exact match. |

author:"Jane Goodall" | A query for a particular author, e.g., Jane Goodall. "J Goodall" or "Goodall" will also work, but will be less restrictive. |

"self-driving cars" AND "autonomous vehicles" | Only results will be shown that contain both the phrases "self-driving cars" and "autonomous vehicles" |

dinosaur 2014 | Limits search results about dinosaurs to articles that were published in 2014 |

Tip: Use the advanced search features in Google Scholar to narrow down your search results.

You can gain even more fine-grained control over your search by using the advanced search feature. This feature is available by clicking on the hamburger menu in the upper left and selecting the "Advanced search" menu item.

Adjusting the Google Scholar settings is not necessary for getting good results, but offers some additional customization, including the ability to enable the above-mentioned library integrations.

The settings menu is found in the hamburger menu located in the top left of the Google Scholar page. The settings are divided into five sections:

- Collections to search: by default Google scholar searches articles and includes patents, but this default can be changed if you are not interested in patents or if you wish to search case law instead.

- Bibliographic manager: you can export relevant citation data via the “Bibliography manager” subsection.

- Languages: if you wish for results to return only articles written in a specific subset of languages, you can define that here.

- Library links: as noted, Google Scholar allows you to get the Full Text of articles through your institution’s subscriptions, where available. Search for, and add, your institution here to have the relevant link included in your search results.

- Button: the Scholar Button is a Chrome extension which adds a dropdown search box to your toolbar. This allows you to search Google Scholar from any website. Moreover, if you have any text selected on the page and then click the button it will display results from a search on those words when clicked.

When signed in, Google Scholar adds some simple tools for keeping track of and organizing the articles you find. These can be useful if you are not using a full academic reference manager.

All the search results include a “save” button at the end of the bottom row of links, clicking this will add it to your "My Library".

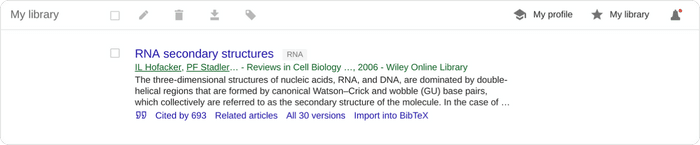

To help you provide some structure, you can create and apply labels to the items in your library. Appended labels will appear at the end of the article titles. For example, the following article has been assigned a “RNA” label:

Within your Google Scholar library, you can also edit the metadata associated with titles. This will often be necessary as Google Scholar citation data is often faulty.

There is no official statement about how big the Scholar search index is, but unofficial estimates are in the range of about 160 million , and it is supposed to continue to grow by several million each year.

Yet, Google Scholar does not return all resources that you may get in search at you local library catalog. For example, a library database could return podcasts, videos, articles, statistics, or special collections. For now, Google Scholar has only the following publication types:

- Journal articles : articles published in journals. It's a mixture of articles from peer reviewed journals, predatory journals and pre-print archives.

- Books : links to the Google limited version of the text, when possible.

- Book chapters : chapters within a book, sometimes they are also electronically available.

- Book reviews : reviews of books, but it is not always apparent that it is a review from the search result.

- Conference proceedings : papers written as part of a conference, typically used as part of presentation at the conference.

- Court opinions .

- Patents : Google Scholar only searches patents if the option is selected in the search settings described above.

The information in Google Scholar is not cataloged by professionals. The quality of the metadata will depend heavily on the source that Google Scholar is pulling the information from. This is a much different process to how information is collected and indexed in scholarly databases such as Scopus or Web of Science .

➡️ Visit our list of the best academic databases .

Google Scholar is by far the most frequently used academic search engine , but it is not the only one. Other academic search engines include:

- Science.gov

- Semantic Scholar

- scholar.google.fr : Sur les épaules d'un géant

- scholar.google.es (Google Académico): A hombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.pt (Google Académico): Sobre os ombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.de : Auf den Schultern von Riesen

➡️ Once you’ve found some research, it’s time to read it. Take a look at our guide on how to read a scientific paper .

No. Google Scholar is a bibliographic search engine rather than a bibliographic database. In order to qualify as a database Google Scholar would need to have stable identifiers for its records.

No. Google Scholar is an academic search engine, but the records found in Google Scholar are scholarly sources.

No. Google Scholar collects research papers from all over the web, including grey literature and non-peer reviewed papers and reports.

Google Scholar does not provide any full text content itself, but links to the full text article on the publisher page, which can either be open access or paywalled content. Google Scholar tries to provide links to free versions, when possible.

The easiest way to access Google scholar is by using The Google Scholar Button. This is a browser extension that allows you easily access Google Scholar from any web page. You can install it from the Chrome Webstore .

Research Basics: an open academic research skills course

- Lesson 1: Using Library Tools

- Lesson 2: Smart searching

- Lesson 3: Managing information overload

- Assessment - Module 1

- Lesson 1: The ABCs of scholarly sources

- Lesson 2: Additional ways of identifying scholarly sources

- Lesson 3: Verifying online sources

- Assessment - Module 2

- Lesson 1: Creating citations

- Lesson 2: Citing and paraphrasing

- Lesson 3: Works cited, bibliographies, and notes

- Assessment - Module 3

- - For Librarians and Teachers -

- Acknowledgements

- Other free resources from JSTOR

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students.

Learn more about JSTOR

Get Help with JSTOR

JSTOR Website & Technical Support

Email: [email protected] Text: (734)-887-7001 Call Toll Free in the U.S.: (888)-388-3574 Call Local and International: (734)-887-7001

Hours of operation: Mon - Fri, 8:30 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. EDT (GMT -4:00)

Welcome to the ever-expanding universe of scholarly research!

There's a lot of digital content out there, and we want to help you get a handle on it. Where do you start? What do you do? How do you use it? Don’t worry, this course has you covered.

This introductory program was created by JSTOR to help you get familiar with basic research concepts needed for success in school. The course contains three modules, each made up of three short lessons and three sets of practice quizzes. The topics covered are subjects that will help you prepare for college-level research. Each module ends with an assessment to test your knowledge.

The JSTOR librarians who helped create the course hope you learn from the experience and feel ready to research when you’ve finished this program. Select Module 1: Effective Searching to begin the course. Good luck!

- Next: Module 1: Effective searching >>

- Last Updated: Apr 24, 2024 6:38 AM

- URL: https://guides.jstor.org/researchbasics

JSTOR is part of ITHAKA , a not-for-profit organization helping the academic community use digital technologies to preserve the scholarly record and to advance research and teaching in sustainable ways.

©2000-2024 ITHAKA. All Rights Reserved. JSTOR®, the JSTOR logo, JPASS®, Artstor® and ITHAKA® are registered trademarks of ITHAKA.

JSTOR.org Terms and Conditions Privacy Policy Cookie Policy Cookie settings Accessibility

The National Weather Service has issued an alert. Visit the KatSafe site for details.

COVID-19 Community Level: Low

- SHSU Online

- Academic Affairs

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Community Engagement (ACE)

- Academic Planning and Program Development

- Academic Success Center

- Accepted Students and Bearkat Orientation

- Admissions (Undergraduate)

- Admissions (Graduate)

- Admission Requirements

- Advising (SAM Center)

- Agricultural Sciences

- Alumni Association

- American Association of University Professors

- Analytical Laboratory

- Application for Admission

- Army ROTC - Military Science

- Arts & Media

- Auxiliary Services

- Bearkat Bundle

- Bearkat Camp

- Bearkat EduNav (BEN)

- Bearkat Express Payment

- Bearkat Kickoff

- Bearkat Marching Band

- Bearkat OneCard

- Bearkat Transfer Scholarship

- Blinn College Transfers

- Budget Office

- Business Administration

- Campus Activities & Traditions

- Campus Recreation

- Career Success Center

- Cashier's Office

- Charter School

- Class Schedule

- Computer Account Creation

- Computer Labs

- Continuing Education

- Controller's Office

- Counseling Center

- Criminal Justice

- Current Students

- Data Analytics and Decision Support

- Dean of Students' Office

- Departments

- Department of Dance

- Dining Services

- Disbursements Services

- Educator Preparation Services

- Emergency Management

- Employee Services Center

- Employment Opportunities

- Engineering Technology

- Enrollment Success

- Enrollment Marketing and Communication

- Enrollment Services - TWC

- Exchange Mail

- Facilities Management

- Faculty Senate

- Faculty/Staff Directory

- Final Exam Schedule

- Finance and Operations

- Financial Aid

- Food & Housing Access Network

- First-Generation Center

- First-Year Experience

- Free Speech & Expressive Activity

- General Information

- Garrett Center

- Global Engagement

- Golf Course

- Graduate Admissions

- The Graduate School

- Great Names

- Health Sciences

- Honors College

- Human Resources

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- IT@Sam Service Desk

- Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC)

- Internal Grant Program

- Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Integrated Marketing & Communications

- Internal Audit

- Joint Admission Students

- Jr. Bearkats

- Leadership Academy

- Leadership Initiatives

- LEAP Center

- Library (NGL)

- Lone Star College Transfers

- Lowman Student Center

- Mail Services

- Map - Campus

- Marketing & Communications

- McNair Program

- Military Science

- Music Choir

- MyGartner Portal

- National Student Exchange

- Office of the President

- Ombuds Office

- Online Information Request

- Organization Chart

- Orientation - New Student

- Osteopathic Medicine

- Parent & Family Relations

- Payroll Office

- PGA Golf Management

- Pre-Health Professional Student Services

- Procurement and Business Services

- Procurement Opportunities

- Program Analytics

- Prospective Students

- Quality Enhancement Plan

- Reading Center

- Registration

- Registrar's Office

- Research Administration (Post-Award)

- Research and Sponsored Programs

- Residence Life

- SACSCOC Reaffirmation

- Sam Houston Memorial Museum

- Services for Students with Disabilities

- Schedule of Classes

- Scholarships

- SHSU MarketPlace

- Spirit Programs

- Smith-Hutson Endowed Chair of Banking

- Smith-Hutson Scholarship Program

- Staff Senate

- Student Affairs

- Student Government Association

- Student Health Center

- Student Legal Services

- Student Money Management Center

- Student Success Technologies

- Study Abroad

- Summer Camps

- Supplemental Instruction

- Technology Tutorials

- Testing Center

- Theatre and Musical Theatre

- Title IX (Sexual Misconduct)

- Tour the University

- Transcripts

- Transfer Equivalency Guide

- Transfer Students (Articulation)

- Travel Services

- Undergraduate Research Symposium

- University Advancement

- University Hotel

- University Police Department

- Visitor Services

- The Woodlands Center

What is Google Scholar and how do I use it?

- Google Scholar

A Quick Look at Google Scholar

What is google scholar.

Google Scholar is a Web search engine that specifically searches scholarly literature and academic resources.

But my teacher said not to use Google! How is "Google Scholar" different from "Google"?

Google searches public Web content. Your teacher says "Don't use Google," meaning that you should not use the public Web content.

Google Scholar is different. It searches the same kinds of scholarly books, articles, and documents that you search in the Library's catalog and databases. The scholarly, authoritative focus of Google Scholar distinguishes it from ordinary Google.

So how is Google Scholar related to (and different from) the Library's databases?

There is overlap between the content in Google Scholar and the Library's individual databases. Also, many citations in Google Scholar will link to full text in the Library's databases or in publicly available databases. But Google Scholar will not contain everything that is in the Library's databases.

Google Scholar can be a convenient starting place, but it is not a comprehensive "one-stop shop." For more precise searching, more search features, and more content, use the Library's individual databases .

How do I search and view items in Google Scholar?

Searching is as easy as searching in regular Google. Start from the Library's Homepage to search SHSU's Google Scholar. Click on the Articles & More tab and locate the Google Scholar search box at the very bottom. Enter a search term or phrase, such as "bird flu."

Like regular Google, Google Scholar returns the most relevant results first, based on an item's full text, author, source, and the number of times it has been cited in other sources. Some actions are a little different from regular Google: clicking on a title may only take you to a citation or description, rather than to the full document itself. Google Scholar will not necessarily get you to the full text of every search result.

How do I find the full-text documents in my search results?

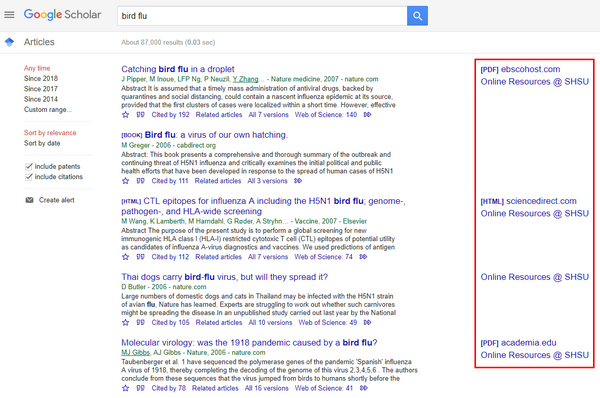

To find the full document, look for (1) a PDF or HTML link to the right of the article title, or (2) an Online Resources @ SHSU link. These links will help you find the full text of the document, either in a publicly available place or in one of the online databases offered by SHSU.

If you don't see these links or they don't take you to the full text, you can contact the Library Service Desk for help in finding the article. Some documents will be unavailable online, but they may be available in the library building or through Interlibrary Loan .

A final word of wisdom...

Keep in mind that Google Scholar is not perfect . For more precise searching, more search features, and more content, check out the Library's individual databases and online catalog .

- Library databases

- Library website

Google Scholar: Search Google Scholar

Search tips for google scholar.

Google Scholar is very similar to Google; you can use many of the same search options.

- Google Scholar automatically places AND between words:

nurse stress retention

- Place quotation marks around phrases or titles:

"social learning theory"

"On the Origin of Species"

- Search for alternate terms using OR, with the terms enclosed in parentheses:

("first grade" OR "second grade")

(theory OR model)

You can also use the advanced Google Scholar search to create your search string. Creating a complex Google Scholar search can be difficult.

A good Google Scholar strategy is to try multiple searches, adjusting your keywords with each search.

- Learn more about Google Scholars advanced search.

Cited By feature in Google Scholar

Use the Cited by link to find articles and books that cite a specific article.

The cited by feature is a great way to find more recent articles and to trace an idea from its original source up to the present.

- Start by locating a single item in Google Scholar.

- Click the Cited by link to see a list of the items that cite your original item. Older and more influential items will have a higher number of Cited by results.

Advanced search options

For more complex searches, try Google Scholar's Advanced Search page.

- To access the advanced search option, click on the three line icon in the upper left corner of the Google Scholar search page.

The advanced search allows you to search more precisely.

- Use the articles dated between option to limit to specific years.

- Try the authored by search box to see resources by a specific author

- Explore the other search options to see what's most effective for your search, such as searching in specific journals, searching for exact phrases, and using different keyword strategies.

Watch a search

- Watch a search for a complicated topic using the advanced search feature.

See how the search differs between a library database and Google Scholar.

- Watch a search for a specific article by title.

Video: Google Scholar Advanced Search

(1 min 18 sec) Recorded January 2018 Transcript

Video: Find an article by title in Google Scholar

(2 min 38 sec) Recorded January 2018 Transcript

- Previous Page: Home

- Next Page: Google Scholar Results & Full Text

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Google Scholar and How to Use it for Research?

Finding scholarly and peer-reviewed articles for academic research on search engines can feel like searching for a needle in a haystack. Enter Google Scholar, a beacon for researchers, academics, and scholars. Unlike traditional Google searches that return a mix of results from various sources, Google Scholar specializes in providing access to scholarly literature. If you’re using Google Scholar for research, this article offers some great tips that will help you optimize your usage of Google Scholar for research and get access to relevant and better results.

Table of Contents

What is Google Scholar?

Google Scholar is a freely available academic search engine developed by Google. It indexes scholarly articles, books, and academic and conference papers by searching repositories of scholarly websites, universities, and publishers across various academic disciplines. For students and researchers, and those in academia, Google Scholar offers quick and easy access to a vast repository of academic content from multiple disciplines that can be useful when writing scholarly manuscripts and citations.

How is Google Scholar different from a regular Google search?

Regular Google search engines are ideal for finding information on general topics, news, and non-academic information as they scan the entire web for information. On the other hand, searches conducted using Google Scholar are more focused on specific subsets of academic and scientific data. However, when searching Google Scholar, students, and researchers need to verify available links and resources, as search results may not always be as reliable and authoritative as those presented by Scopus or Web of Science .

10 Tips to Use Google Scholar for Research

Students and researchers often use Google Scholar for research to access high-quality, credible sources for their work, facilitating a deeper understanding of their research topic. To harness the full potential of Google Scholar, consider these tips:

- Keywords are essential: While using Google Scholar for research, refrain from typing the entire topic of your research; instead, build and utilize a list of keywords. This will make your search more valuable and efficient.

- Use of quotation marks: It is essential to specify the keywords in quotation marks for Google Scholar to provide you with the most relevant results. Quotation marks help establish the fact that you need results that are an exact match to your keywords. On the other hand, if quotation marks are not used, Google Scholar will deal with each keyword separately. This will lead to losing a considerable amount of time in searching for the most suitable articles.

- Search by author’s name: If you want to search for articles and information written by a particular author related to your specific area of study, it is best to search by author name or click on the specific author’s name as it appears in any article produced through the search results.

- Mention details if available: If you know the correct title of the article you are searching for, mention it in quotes in the search bar. This will throw up results with an exact match. Additionally, stating the year of publication of the articles or books you are searching for will get you better results.

- Researcher profiles: Google Scholar offers academics the option of creating their researcher profile, which can help them highlight their work, publications, and citations. This profile can be used as a digital CV and can help in networking and collaboration.

- Integration with universities: Some universities and libraries integrate Google Scholar into their search systems, providing seamless access to academic content through institutional accounts.

- Viewing full-text papers: Undertaking searches on Google Scholar will allow you to view the full text of a document by clicking on the link found on the right of the article title. These are usually presented in either PDF or HTML format. You can also view the full text by using Google Scholar through your institution’s web page in cases where it is accessible by the institution.

- Advanced Search Options: Use the advanced search feature to narrow down results by author, publication, and date. This precision can help you quickly find specific documents.

- Accessing Full-Text Papers: Look for links to PDFs or HTML formats on the right side of the search results page. If your institution has access, you might also find links to full text through your library’s subscriptions.

- Easy Citation: Google Scholar simplifies the citation process by providing citations in various formats (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago) for each article, which can be easily copied and pasted into your work. The citation feature can be used to reference the article you want to use. However, it is always helpful to cross-check the references to see if all the information is included in it.

- Use of My Library: In order to save the information and articles you choose from the search results and structure and organize them, it is always helpful to make use of the “my library” feature in Google Scholar. You can create a library where you will be able to save the needed documents.

How does R Discovery optimize your research reading process?

Keeping up with the latest research in your field and related areas is challenging. Every year, millions of papers are published, making it difficult to stay informed. Imagine how much simpler it would be if you could receive recommendations for research tailored to your interests. While Google Scholar is a powerful tool, R Discovery uses its tech capabilities around AI, ML, and NLP to solve the problem of recurring searches for research for researchers.

For example, if you search for COVID-19 on Google Scholar and log out, you’ll have to ask Google Scholar (in every session) to show you content about COVID-19. This process becomes repetitive and consumes most of your time. Moreover, Google Scholar finds content that has been properly optimized for search. This means if a paper was not very famous or was not correctly tagged on the internet, you may never discover it.

R Discovery’s targeted research reading with Literature Recommendations makes this process easier. R Discovery sifts through over 100 million scholarly articles across more than 9.5 million topics, quickly curates a list of research papers that match your interests, and offers personalized reading recommendations, saving you time. R Discovery saves your search queries and topics against your profile and will find relevant papers for you without any search every time you come to the app.

With R Discovery, get access to the most extensive collection of open-access journals, including over 39 million open-access papers and more than 2 million preprints, all in one convenient location. If you’re new to R Discovery, now’s the perfect opportunity to get relevant research recommendations and simplify your research discovery. Click to install the free R Discovery app now!

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

How to Make a Graphical Abstract for Your Research Paper (with Examples)

Simple Random Sampling: Definition, Methods, and Examples

28 Best Academic Search Engines That make your research easier

If you’re a researcher or scholar, you know that conducting effective online research is a critical part of your job. And if you’re like most people, you’re always on the lookout for new and better ways to do it.

This article aims to give you an edge over researchers that rely mainly on Google for their entire research process.

Table of Contents

#1. Google Scholar

Google Scholar is an academic search engine that indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines.

Great for academic research, you can use Google Scholar to find articles from academic journals, conference proceedings, theses, and dissertations. The results returned by Google Scholar are typically more relevant and reliable than those from regular search engines like Google.

#2. ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

ERIC (short for educational resources information center) is a great academic search engine that focuses on education-related literature. It is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education and produced by the Institute of Education Sciences.

ERIC indexes over a million articles, reports, conference papers, and other resources on all aspects of education from early childhood to higher education. So, search results are more relevant to Education on ERIC.

ERIC is a free online database of education-related literature.

#3. Wolfram Alpha

Wolfram Alpha is a “computational knowledge engine” that can answer factual questions posed in natural language. It can be a useful search tool.

Wolfram Alpha can also be used to find academic articles. Just type in your keywords and Wolfram Alpha will generate a list of academic articles that match your query.

#4. iSEEK Education

iSEEK is a search engine targeting students, teachers, administrators, and caregiver. It’s designed to be safe with editor-reviewed content.

iSEEK Education is free to use.

#5. BASE (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine)

CORE is an academic search engine that focuses on open access research papers. A link to the full text PDF or complete text web page is supplied for each search result. It’s academic search engine dedicated to open access research papers.

You might also like:

#7. Science.gov

#8. semantic scholar, #9. refseek.

This is one of the free search engines that feels like Yahoo with a massive directory. It could be good when you are just looking for research ideas from unexpected angles. It could lead you to some other database that you might not know such as the CIA The World Factbook, which is a great reference tool.

#10. ResearchGate

A mixture of social networking site + forum + content databases where researchers can build their profile, share research papers, and interact with one another.

#11. DataONE Search (formerly CiteULike)

#12. dataelixir , #13. lazyscholar – browser extension, #14. citeseerx – digital library from penstate, #15. the lens – patents search , #16. fatcat – wiki for bibliographic catalog , #17. lexis web – legal database, #18. infotopia – part of the vlrc family, #19. virtual learning resources center, #21. worldwidescience.

Over 70 countries’ databases are used on the website. When a user enters a query, it contacts databases from all across the world and shows results in both English and translated journals and academic resources.

#22. Google Books

A user can browse thousands of books on Google Books, from popular titles to old titles, to find pages that include their search terms. You can look through pages, read online reviews, and find out where to buy a hard copy once you find the book you are interested in.

#23. DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals)

#24. baidu scholar, #25. pubmed central, #26. medline®.

MEDLINE® is a paid subscription database for life sciences and biomedicine that includes more than 28 million citations to journal articles. For finding reliable, carefully chosen health information, Medline Plus provides a powerful search tool and even a dictionary.