Validity In Psychology Research: Types & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

In psychology research, validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement tool accurately measures what it’s intended to measure. It ensures that the research findings are genuine and not due to extraneous factors.

Validity can be categorized into different types based on internal and external validity .

The concept of validity was formulated by Kelly (1927, p. 14), who stated that a test is valid if it measures what it claims to measure. For example, a test of intelligence should measure intelligence and not something else (such as memory).

Internal and External Validity In Research

Internal validity refers to whether the effects observed in a study are due to the manipulation of the independent variable and not some other confounding factor.

In other words, there is a causal relationship between the independent and dependent variables .

Internal validity can be improved by controlling extraneous variables, using standardized instructions, counterbalancing, and eliminating demand characteristics and investigator effects.

External validity refers to the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other settings (ecological validity), other people (population validity), and over time (historical validity).

External validity can be improved by setting experiments more naturally and using random sampling to select participants.

Types of Validity In Psychology

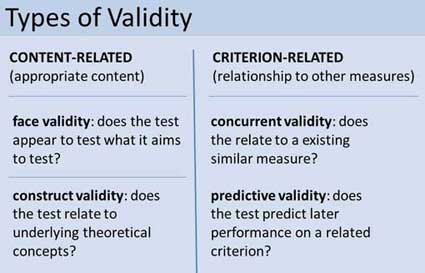

Two main categories of validity are used to assess the validity of the test (i.e., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.): Content and criterion.

- Content validity refers to the extent to which a test or measurement represents all aspects of the intended content domain. It assesses whether the test items adequately cover the topic or concept.

- Criterion validity assesses the performance of a test based on its correlation with a known external criterion or outcome. It can be further divided into concurrent (measured at the same time) and predictive (measuring future performance) validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is simply whether the test appears (at face value) to measure what it claims to. This is the least sophisticated measure of content-related validity, and is a superficial and subjective assessment based on appearance.

Tests wherein the purpose is clear, even to naïve respondents, are said to have high face validity. Accordingly, tests wherein the purpose is unclear have low face validity (Nevo, 1985).

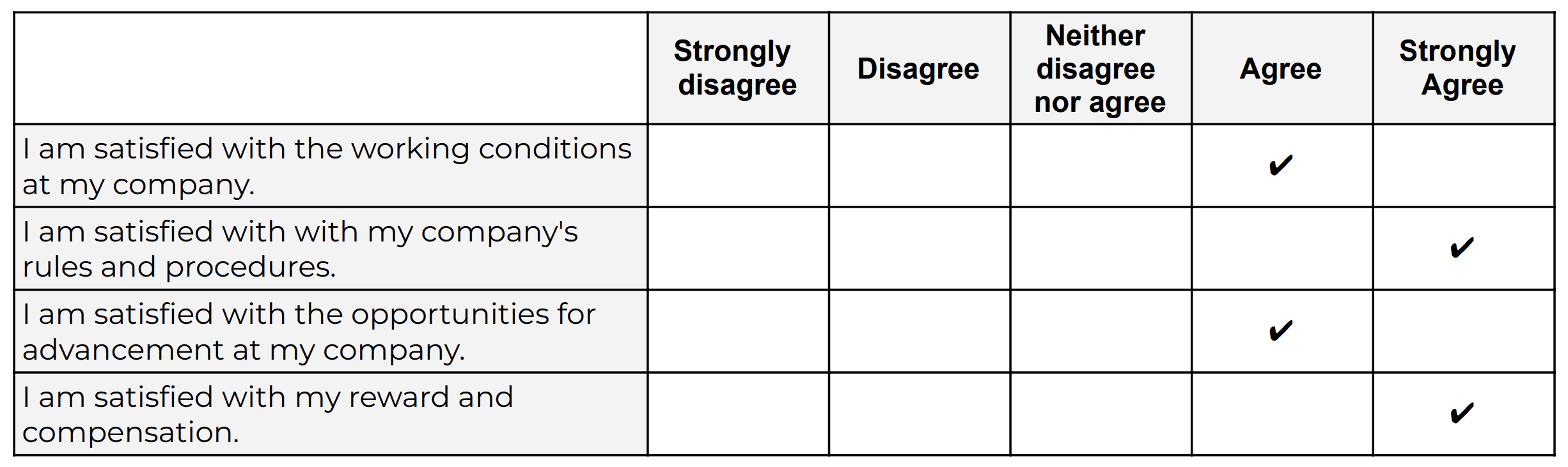

A direct measurement of face validity is obtained by asking people to rate the validity of a test as it appears to them. This rater could use a Likert scale to assess face validity.

For example:

- The test is extremely suitable for a given purpose

- The test is very suitable for that purpose;

- The test is adequate

- The test is inadequate

- The test is irrelevant and, therefore, unsuitable

It is important to select suitable people to rate a test (e.g., questionnaire, interview, IQ test, etc.). For example, individuals who actually take the test would be well placed to judge its face validity.

Also, people who work with the test could offer their opinion (e.g., employers, university administrators, employers). Finally, the researcher could use members of the general public with an interest in the test (e.g., parents of testees, politicians, teachers, etc.).

The face validity of a test can be considered a robust construct only if a reasonable level of agreement exists among raters.

It should be noted that the term face validity should be avoided when the rating is done by an “expert,” as content validity is more appropriate.

Having face validity does not mean that a test really measures what the researcher intends to measure, but only in the judgment of raters that it appears to do so. Consequently, it is a crude and basic measure of validity.

A test item such as “ I have recently thought of killing myself ” has obvious face validity as an item measuring suicidal cognitions and may be useful when measuring symptoms of depression.

However, the implication of items on tests with clear face validity is that they are more vulnerable to social desirability bias. Individuals may manipulate their responses to deny or hide problems or exaggerate behaviors to present a positive image of themselves.

It is possible for a test item to lack face validity but still have general validity and measure what it claims to measure. This is good because it reduces demand characteristics and makes it harder for respondents to manipulate their answers.

For example, the test item “ I believe in the second coming of Christ ” would lack face validity as a measure of depression (as the purpose of the item is unclear).

This item appeared on the first version of The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and loaded on the depression scale.

Because most of the original normative sample of the MMPI were good Christians, only a depressed Christian would think Christ is not coming back. Thus, for this particular religious sample, the item does have general validity but not face validity.

Construct Validity

Construct validity assesses how well a test or measure represents and captures an abstract theoretical concept, known as a construct. It indicates the degree to which the test accurately reflects the construct it intends to measure, often evaluated through relationships with other variables and measures theoretically connected to the construct.

Construct validity was invented by Cronbach and Meehl (1955). This type of content-related validity refers to the extent to which a test captures a specific theoretical construct or trait, and it overlaps with some of the other aspects of validity

Construct validity does not concern the simple, factual question of whether a test measures an attribute.

Instead, it is about the complex question of whether test score interpretations are consistent with a nomological network involving theoretical and observational terms (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955).

To test for construct validity, it must be demonstrated that the phenomenon being measured actually exists. So, the construct validity of a test for intelligence, for example, depends on a model or theory of intelligence .

Construct validity entails demonstrating the power of such a construct to explain a network of research findings and to predict further relationships.

The more evidence a researcher can demonstrate for a test’s construct validity, the better. However, there is no single method of determining the construct validity of a test.

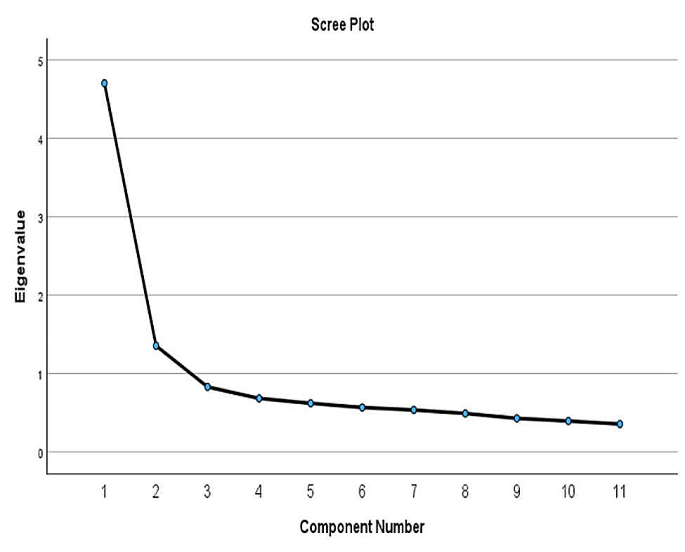

Instead, different methods and approaches are combined to present the overall construct validity of a test. For example, factor analysis and correlational methods can be used.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is a subtype of construct validity. It assesses the degree to which two measures that theoretically should be related are related.

It demonstrates that measures of similar constructs are highly correlated. It helps confirm that a test accurately measures the intended construct by showing its alignment with other tests designed to measure the same or similar constructs.

For example, suppose there are two different scales used to measure self-esteem:

Scale A and Scale B. If both scales effectively measure self-esteem, then individuals who score high on Scale A should also score high on Scale B, and those who score low on Scale A should score similarly low on Scale B.

If the scores from these two scales show a strong positive correlation, then this provides evidence for convergent validity because it indicates that both scales seem to measure the same underlying construct of self-esteem.

Concurrent Validity (i.e., occurring at the same time)

Concurrent validity evaluates how well a test’s results correlate with the results of a previously established and accepted measure, when both are administered at the same time.

It helps in determining whether a new measure is a good reflection of an established one without waiting to observe outcomes in the future.

If the new test is validated by comparison with a currently existing criterion, we have concurrent validity.

Very often, a new IQ or personality test might be compared with an older but similar test known to have good validity already.

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity assesses how well a test predicts a criterion that will occur in the future. It measures the test’s ability to foresee the performance of an individual on a related criterion measured at a later point in time. It gauges the test’s effectiveness in predicting subsequent real-world outcomes or results.

For example, a prediction may be made on the basis of a new intelligence test that high scorers at age 12 will be more likely to obtain university degrees several years later. If the prediction is born out, then the test has predictive validity.

Cronbach, L. J., and Meehl, P. E. (1955) Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin , 52, 281-302.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). Manual for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory . New York: Psychological Corporation.

Kelley, T. L. (1927). Interpretation of educational measurements. New York : Macmillan.

Nevo, B. (1985). Face validity revisited . Journal of Educational Measurement , 22(4), 287-293.

What is the Significance of Validity in Research?

Introduction

- What is validity in simple terms?

Internal validity vs. external validity in research

Uncovering different types of research validity, factors that improve research validity.

In qualitative research , validity refers to an evaluation metric for the trustworthiness of study findings. Within the expansive landscape of research methodologies , the qualitative approach, with its rich, narrative-driven investigations, demands unique criteria for ensuring validity.

Unlike its quantitative counterpart, which often leans on numerical robustness and statistical veracity, the essence of validity in qualitative research delves deep into the realms of credibility, dependability, and the richness of the data .

The importance of validity in qualitative research cannot be overstated. Establishing validity refers to ensuring that the research findings genuinely reflect the phenomena they are intended to represent. It reinforces the researcher's responsibility to present an authentic representation of study participants' experiences and insights.

This article will examine validity in qualitative research, exploring its characteristics, techniques to bolster it, and the challenges that researchers might face in establishing validity.

At its core, validity in research speaks to the degree to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure or understand. It's about ensuring that the study investigates what it purports to investigate. While this seems like a straightforward idea, the way validity is approached can vary greatly between qualitative and quantitative research .

Quantitative research often hinges on numerical, measurable data. In this paradigm, validity might refer to whether a specific tool or method measures the correct variable, without interference from other variables. It's about numbers, scales, and objective measurements. For instance, if one is studying personalities by administering surveys, a valid instrument could be a survey that has been rigorously developed and tested to verify that the survey questions are referring to personality characteristics and not other similar concepts, such as moods, opinions, or social norms.

Conversely, qualitative research is more concerned with understanding human behavior and the reasons that govern such behavior. It's less about measuring in the strictest sense and more about interpreting the phenomenon that is being studied. The questions become: "Are these interpretations true representations of the human experience being studied?" and "Do they authentically convey participants' perspectives and contexts?"

Differentiating between qualitative and quantitative validity is crucial because the research methods to ensure validity differ between these research paradigms. In quantitative realms, validity might involve test-retest reliability or examining the internal consistency of a test.

In the qualitative sphere, however, the focus shifts to ensuring that the researcher's interpretations align with the actual experiences and perspectives of their subjects.

This distinction is fundamental because it impacts how researchers engage in research design , gather data , and draw conclusions . Ensuring validity in qualitative research is like weaving a tapestry: every strand of data must be carefully interwoven with the interpretive threads of the researcher, creating a cohesive and faithful representation of the studied experience.

While often terms associated more closely with quantitative research, internal and external validity can still be relevant concepts to understand within the context of qualitative inquiries. Grasping these notions can help qualitative researchers better navigate the challenges of ensuring their findings are both credible and applicable in wider contexts.

Internal validity

Internal validity refers to the authenticity and truthfulness of the findings within the study itself. In qualitative research , this might involve asking: Do the conclusions drawn genuinely reflect the perspectives and experiences of the study's participants?

Internal validity revolves around the depth of understanding, ensuring that the researcher's interpretations are grounded in participants' realities. Techniques like member checking , where participants review and verify the researcher's interpretations , can bolster internal validity.

External validity

External validity refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be generalized or applied to other settings or groups. For qualitative researchers, the emphasis isn't on statistical generalizability, as often seen in quantitative studies. Instead, it's about transferability.

It becomes a matter of determining how and where the insights gathered might be relevant in other contexts. This doesn't mean that every qualitative study's findings will apply universally, but qualitative researchers should provide enough detail (through rich, thick descriptions) to allow readers or other researchers to determine the potential for transfer to other contexts.

Try out a free trial of ATLAS.ti today

See how you can turn your data into critical research findings with our intuitive interface.

Looking deeper into the realm of validity, it's crucial to recognize and understand its various types. Each type offers distinct criteria and methods of evaluation, ensuring that research remains robust and genuine. Here's an exploration of some of these types.

Construct validity

Construct validity is a cornerstone in research methodology . It pertains to ensuring that the tools or methods used in a research study genuinely capture the intended theoretical constructs.

In qualitative research , the challenge lies in the abstract nature of many constructs. For example, if one were to investigate "emotional intelligence" or "social cohesion," the definitions might vary, making them hard to pin down.

To bolster construct validity, it is important to clearly and transparently define the concepts being studied. In addition, researchers may triangulate data from multiple sources , ensuring that different viewpoints converge towards a shared understanding of the construct. Furthermore, they might delve into iterative rounds of data collection, refining their methods with each cycle to better align with the conceptual essence of their focus.

Content validity

Content validity's emphasis is on the breadth and depth of the content being assessed. In other words, content validity refers to capturing all relevant facets of the phenomenon being studied. Within qualitative paradigms, ensuring comprehensive representation is paramount. If, for instance, a researcher is using interview protocols to understand community perceptions of a local policy, it's crucial that the questions encompass all relevant aspects of that policy. This could range from its implementation and impact to public awareness and opinion variations across demographic groups.

Enhancing content validity can involve expert reviews where subject matter experts evaluate tools or methods for comprehensiveness. Another strategy might involve pilot studies , where preliminary data collection reveals gaps or overlooked aspects that can be addressed in the main study.

Ecological validity

Ecological validity refers to the genuine reflection of real-world situations in research findings. For qualitative researchers, this means their observations , interpretations , and conclusions should resonate with the participants and context being studied.

If a study explores classroom dynamics, for example, studying students and teachers in a controlled research setting would have lower ecological validity than studying real classroom settings. Ecological validity is important to consider because it helps ensure the research is relevant to the people being studied. Individuals might behave entirely different in a controlled environment as opposed to their everyday natural settings.

Ecological validity tends to be stronger in qualitative research compared to quantitative research , because qualitative researchers are typically immersed in their study context and explore participants' subjective perceptions and experiences. Quantitative research, in contrast, can sometimes be more artificial if behavior is being observed in a lab or participants have to choose from predetermined options to answer survey questions.

Qualitative researchers can further bolster ecological validity through immersive fieldwork, where researchers spend extended periods in the studied environment. This immersion helps them capture the nuances and intricacies that might be missed in brief or superficial engagements.

Face validity

Face validity, while seemingly straightforward, holds significant weight in the preliminary stages of research. It serves as a litmus test, gauging the apparent appropriateness and relevance of a tool or method. If a researcher is developing a new interview guide to gauge employee satisfaction, for instance, a quick assessment from colleagues or a focus group can reveal if the questions intuitively seem fit for the purpose.

While face validity is more subjective and lacks the depth of other validity types, it's a crucial initial step, ensuring that the research starts on the right foot.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity evaluates how well the results obtained from one method correlate with those from another, more established method. In many research scenarios, establishing high criterion validity involves using statistical methods to measure validity. For instance, a researcher might utilize the appropriate statistical tests to determine the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two sets of data.

If a new measurement tool or method is being introduced, its validity might be established by statistically correlating its outcomes with those of a gold standard or previously validated tool. Correlational statistics can estimate the strength of the relationship between the new instrument and the previously established instrument, and regression analyses can also be useful to predict outcomes based on established criteria.

While these methods are traditionally aligned with quantitative research, qualitative researchers, particularly those using mixed methods , may also find value in these statistical approaches, especially when wanting to quantify certain aspects of their data for comparative purposes. More broadly, qualitative researchers could compare their operationalizations and findings to other similar qualitative studies to assess that they are indeed examining what they intend to study.

In the realm of qualitative research , the role of the researcher is not just that of an observer but often as an active participant in the meaning-making process. This unique positioning means the researcher's perspectives and interactions can significantly influence the data collected and its interpretation . Here's a deep dive into the researcher's pivotal role in upholding validity.

Reflexivity

A key concept in qualitative research, reflexivity requires researchers to continually reflect on their worldviews, beliefs, and potential influence on the data. By maintaining a reflexive journal or engaging in regular introspection, researchers can identify and address their own biases , ensuring a more genuine interpretation of participant narratives.

Building rapport

The depth and authenticity of information shared by participants often hinge on the rapport and trust established with the researcher. By cultivating genuine, non-judgmental, and empathetic relationships with participants, researchers can enhance the validity of the data collected.

Positionality

Every researcher brings to the study their own background, including their culture, education, socioeconomic status, and more. Recognizing how this positionality might influence interpretations and interactions is crucial. By acknowledging and transparently sharing their positionality, researchers can offer context to their findings and interpretations.

Active listening

The ability to listen without imposing one's own judgments or interpretations is vital. Active listening ensures that researchers capture the participants' experiences and emotions without distortion, enhancing the validity of the findings.

Transparency in methods

To ensure validity, researchers should be transparent about every step of their process. From how participants were selected to how data was analyzed , a clear documentation offers others a chance to understand and evaluate the research's authenticity and rigor .

Member checking

Once data is collected and interpreted, revisiting participants to confirm the researcher's interpretations can be invaluable. This process, known as member checking , ensures that the researcher's understanding aligns with the participants' intended meanings, bolstering validity.

Embracing ambiguity

Qualitative data can be complex and sometimes contradictory. Instead of trying to fit data into preconceived notions or frameworks, researchers must embrace ambiguity, acknowledging areas of uncertainty or multiple interpretations.

Make the most of your research study with ATLAS.ti

From study design to data analysis, let ATLAS.ti guide you through the research process. Download a free trial today.

Validity in research: a guide to measuring the right things

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Validity is necessary for all types of studies ranging from market validation of a business or product idea to the effectiveness of medical trials and procedures. So, how can you determine whether your research is valid? This guide can help you understand what validity is, the types of validity in research, and the factors that affect research validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is validity?

In the most basic sense, validity is the quality of being based on truth or reason. Valid research strives to eliminate the effects of unrelated information and the circumstances under which evidence is collected.

Validity in research is the ability to conduct an accurate study with the right tools and conditions to yield acceptable and reliable data that can be reproduced. Researchers rely on carefully calibrated tools for precise measurements. However, collecting accurate information can be more of a challenge.

Studies must be conducted in environments that don't sway the results to achieve and maintain validity. They can be compromised by asking the wrong questions or relying on limited data.

Why is validity important in research?

Research is used to improve life for humans. Every product and discovery, from innovative medical breakthroughs to advanced new products, depends on accurate research to be dependable. Without it, the results couldn't be trusted, and products would likely fail. Businesses would lose money, and patients couldn't rely on medical treatments.

While wasting money on a lousy product is a concern, lack of validity paints a much grimmer picture in the medical field or producing automobiles and airplanes, for example. Whether you're launching an exciting new product or conducting scientific research, validity can determine success and failure.

- What is reliability?

Reliability is the ability of a method to yield consistency. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same method to measure something, the measurement method is said to be reliable. For example, a thermometer that shows the same temperatures each time in a controlled environment is reliable.

While high reliability is a part of measuring validity, it's only part of the puzzle. If the reliable thermometer hasn't been properly calibrated and reliably measures temperatures two degrees too high, it doesn't provide a valid (accurate) measure of temperature.

Similarly, if a researcher uses a thermometer to measure weight, the results won't be accurate because it's the wrong tool for the job.

- How are reliability and validity assessed?

While measuring reliability is a part of measuring validity, there are distinct ways to assess both measurements for accuracy.

How is reliability measured?

These measures of consistency and stability help assess reliability, including:

Consistency and stability of the same measure when repeated multiple times and conditions

Consistency and stability of the measure across different test subjects

Consistency and stability of results from different parts of a test designed to measure the same thing

How is validity measured?

Since validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure, it can be difficult to assess the accuracy. Validity can be estimated by comparing research results to other relevant data or theories.

The adherence of a measure to existing knowledge of how the concept is measured

The ability to cover all aspects of the concept being measured

The relation of the result in comparison with other valid measures of the same concept

- What are the types of validity in a research design?

Research validity is broadly gathered into two groups: internal and external. Yet, this grouping doesn't clearly define the different types of validity. Research validity can be divided into seven distinct groups.

Face validity : A test that appears valid simply because of the appropriateness or relativity of the testing method, included information, or tools used.

Content validity : The determination that the measure used in research covers the full domain of the content.

Construct validity : The assessment of the suitability of the measurement tool to measure the activity being studied.

Internal validity : The assessment of how your research environment affects measurement results. This is where other factors can’t explain the extent of an observed cause-and-effect response.

External validity : The extent to which the study will be accurate beyond the sample and the level to which it can be generalized in other settings, populations, and measures.

Statistical conclusion validity: The determination of whether a relationship exists between procedures and outcomes (appropriate sampling and measuring procedures along with appropriate statistical tests).

Criterion-related validity : A measurement of the quality of your testing methods against a criterion measure (like a “gold standard” test) that is measured at the same time.

- Examples of validity

Like different types of research and the various ways to measure validity, examples of validity can vary widely. These include:

A questionnaire may be considered valid because each question addresses specific and relevant aspects of the study subject.

In a brand assessment study, researchers can use comparison testing to verify the results of an initial study. For example, the results from a focus group response about brand perception are considered more valid when the results match that of a questionnaire answered by current and potential customers.

A test to measure a class of students' understanding of the English language contains reading, writing, listening, and speaking components to cover the full scope of how language is used.

- Factors that affect research validity

Certain factors can affect research validity in both positive and negative ways. By understanding the factors that improve validity and those that threaten it, you can enhance the validity of your study. These include:

Random selection of participants vs. the selection of participants that are representative of your study criteria

Blinding with interventions the participants are unaware of (like the use of placebos)

Manipulating the experiment by inserting a variable that will change the results

Randomly assigning participants to treatment and control groups to avoid bias

Following specific procedures during the study to avoid unintended effects

Conducting a study in the field instead of a laboratory for more accurate results

Replicating the study with different factors or settings to compare results

Using statistical methods to adjust for inconclusive data

What are the common validity threats in research, and how can their effects be minimized or nullified?

Research validity can be difficult to achieve because of internal and external threats that produce inaccurate results. These factors can jeopardize validity.

History: Events that occur between an early and later measurement

Maturation: The passage of time in a study can include data on actions that would have naturally occurred outside of the settings of the study

Repeated testing: The outcome of repeated tests can change the outcome of followed tests

Selection of subjects: Unconscious bias which can result in the selection of uniform comparison groups

Statistical regression: Choosing subjects based on extremes doesn't yield an accurate outcome for the majority of individuals

Attrition: When the sample group is diminished significantly during the course of the study

Maturation: When subjects mature during the study, and natural maturation is awarded to the effects of the study

While some validity threats can be minimized or wholly nullified, removing all threats from a study is impossible. For example, random selection can remove unconscious bias and statistical regression.

Researchers can even hope to avoid attrition by using smaller study groups. Yet, smaller study groups could potentially affect the research in other ways. The best practice for researchers to prevent validity threats is through careful environmental planning and t reliable data-gathering methods.

- How to ensure validity in your research

Researchers should be mindful of the importance of validity in the early planning stages of any study to avoid inaccurate results. Researchers must take the time to consider tools and methods as well as how the testing environment matches closely with the natural environment in which results will be used.

The following steps can be used to ensure validity in research:

Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Use appropriate sampling to choose test subjects

Create an accurate testing environment

How do you maintain validity in research?

Accurate research is usually conducted over a period of time with different test subjects. To maintain validity across an entire study, you must take specific steps to ensure that gathered data has the same levels of accuracy.

Consistency is crucial for maintaining validity in research. When researchers apply methods consistently and standardize the circumstances under which data is collected, validity can be maintained across the entire study.

Is there a need for validation of the research instrument before its implementation?

An essential part of validity is choosing the right research instrument or method for accurate results. Consider the thermometer that is reliable but still produces inaccurate results. You're unlikely to achieve research validity without activities like calibration, content, and construct validity.

- Understanding research validity for more accurate results

Without validity, research can't provide the accuracy necessary to deliver a useful study. By getting a clear understanding of validity in research, you can take steps to improve your research skills and achieve more accurate results.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

In quantitative research , you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid. There are four main types of validity:

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

- Content validity : Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure?

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

Note that this article deals with types of test validity, which determine the accuracy of the actual components of a measure. If you are doing experimental research, you also need to consider internal and external validity , which deal with the experimental design and the generalisability of results.

Table of contents

Construct validity, content validity, face validity, criterion validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether a measurement tool really represents the thing we are interested in measuring. It’s central to establishing the overall validity of a method.

What is a construct?

A construct refers to a concept or characteristic that can’t be directly observed but can be measured by observing other indicators that are associated with it.

Constructs can be characteristics of individuals, such as intelligence, obesity, job satisfaction, or depression; they can also be broader concepts applied to organisations or social groups, such as gender equality, corporate social responsibility, or freedom of speech.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity is about ensuring that the method of measurement matches the construct you want to measure. If you develop a questionnaire to diagnose depression, you need to know: does the questionnaire really measure the construct of depression? Or is it actually measuring the respondent’s mood, self-esteem, or some other construct?

To achieve construct validity, you have to ensure that your indicators and measurements are carefully developed based on relevant existing knowledge. The questionnaire must include only relevant questions that measure known indicators of depression.

The other types of validity described below can all be considered as forms of evidence for construct validity.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Content validity assesses whether a test is representative of all aspects of the construct.

To produce valid results, the content of a test, survey, or measurement method must cover all relevant parts of the subject it aims to measure. If some aspects are missing from the measurement (or if irrelevant aspects are included), the validity is threatened.

Face validity considers how suitable the content of a test seems to be on the surface. It’s similar to content validity, but face validity is a more informal and subjective assessment.

As face validity is a subjective measure, it’s often considered the weakest form of validity. However, it can be useful in the initial stages of developing a method.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test can predict a concrete outcome, or how well the results of your test approximate the results of another test.

What is a criterion variable?

A criterion variable is an established and effective measurement that is widely considered valid, sometimes referred to as a ‘gold standard’ measurement. Criterion variables can be very difficult to find.

What is criterion validity?

To evaluate criterion validity, you calculate the correlation between the results of your measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. If there is a high correlation, this gives a good indication that your test is measuring what it intends to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 8 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/validity-types/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples.

Validity & Reliability In Research

A Plain-Language Explanation (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | September 2023

Validity and reliability are two related but distinctly different concepts within research. Understanding what they are and how to achieve them is critically important to any research project. In this post, we’ll unpack these two concepts as simply as possible.

This post is based on our popular online course, Research Methodology Bootcamp . In the course, we unpack the basics of methodology using straightfoward language and loads of examples. If you’re new to academic research, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Validity & Reliability

- The big picture

- Validity 101

- Reliability 101

- Key takeaways

First, The Basics…

First, let’s start with a big-picture view and then we can zoom in to the finer details.

Validity and reliability are two incredibly important concepts in research, especially within the social sciences. Both validity and reliability have to do with the measurement of variables and/or constructs – for example, job satisfaction, intelligence, productivity, etc. When undertaking research, you’ll often want to measure these types of constructs and variables and, at the simplest level, validity and reliability are about ensuring the quality and accuracy of those measurements .

As you can probably imagine, if your measurements aren’t accurate or there are quality issues at play when you’re collecting your data, your entire study will be at risk. Therefore, validity and reliability are very important concepts to understand (and to get right). So, let’s unpack each of them.

What Is Validity?

In simple terms, validity (also called “construct validity”) is all about whether a research instrument accurately measures what it’s supposed to measure .

For example, let’s say you have a set of Likert scales that are supposed to quantify someone’s level of overall job satisfaction. If this set of scales focused purely on only one dimension of job satisfaction, say pay satisfaction, this would not be a valid measurement, as it only captures one aspect of the multidimensional construct. In other words, pay satisfaction alone is only one contributing factor toward overall job satisfaction, and therefore it’s not a valid way to measure someone’s job satisfaction.

Oftentimes in quantitative studies, the way in which the researcher or survey designer interprets a question or statement can differ from how the study participants interpret it . Given that respondents don’t have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions when taking a survey, it’s easy for these sorts of misunderstandings to crop up. Naturally, if the respondents are interpreting the question in the wrong way, the data they provide will be pretty useless . Therefore, ensuring that a study’s measurement instruments are valid – in other words, that they are measuring what they intend to measure – is incredibly important.

There are various types of validity and we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole in this post, but it’s worth quickly highlighting the importance of making sure that your research instrument is tightly aligned with the theoretical construct you’re trying to measure . In other words, you need to pay careful attention to how the key theories within your study define the thing you’re trying to measure – and then make sure that your survey presents it in the same way.

For example, sticking with the “job satisfaction” construct we looked at earlier, you’d need to clearly define what you mean by job satisfaction within your study (and this definition would of course need to be underpinned by the relevant theory). You’d then need to make sure that your chosen definition is reflected in the types of questions or scales you’re using in your survey . Simply put, you need to make sure that your survey respondents are perceiving your key constructs in the same way you are. Or, even if they’re not, that your measurement instrument is capturing the necessary information that reflects your definition of the construct at hand.

If all of this talk about constructs sounds a bit fluffy, be sure to check out Research Methodology Bootcamp , which will provide you with a rock-solid foundational understanding of all things methodology-related. Remember, you can take advantage of our 60% discount offer using this link.

Need a helping hand?

What Is Reliability?

As with validity, reliability is an attribute of a measurement instrument – for example, a survey, a weight scale or even a blood pressure monitor. But while validity is concerned with whether the instrument is measuring the “thing” it’s supposed to be measuring, reliability is concerned with consistency and stability . In other words, reliability reflects the degree to which a measurement instrument produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to the same phenomenon , under the same conditions .

As you can probably imagine, a measurement instrument that achieves a high level of consistency is naturally more dependable (or reliable) than one that doesn’t – in other words, it can be trusted to provide consistent measurements . And that, of course, is what you want when undertaking empirical research. If you think about it within a more domestic context, just imagine if you found that your bathroom scale gave you a different number every time you hopped on and off of it – you wouldn’t feel too confident in its ability to measure the variable that is your body weight 🙂

It’s worth mentioning that reliability also extends to the person using the measurement instrument . For example, if two researchers use the same instrument (let’s say a measuring tape) and they get different measurements, there’s likely an issue in terms of how one (or both) of them are using the measuring tape. So, when you think about reliability, consider both the instrument and the researcher as part of the equation.

As with validity, there are various types of reliability and various tests that can be used to assess the reliability of an instrument. A popular one that you’ll likely come across for survey instruments is Cronbach’s alpha , which is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree to which items within an instrument (for example, a set of Likert scales) measure the same underlying construct . In other words, Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely related the items are and whether they consistently capture the same concept .

Recap: Key Takeaways

Alright, let’s quickly recap to cement your understanding of validity and reliability:

- Validity is concerned with whether an instrument (e.g., a set of Likert scales) is measuring what it’s supposed to measure

- Reliability is concerned with whether that measurement is consistent and stable when measuring the same phenomenon under the same conditions.

In short, validity and reliability are both essential to ensuring that your data collection efforts deliver high-quality, accurate data that help you answer your research questions . So, be sure to always pay careful attention to the validity and reliability of your measurement instruments when collecting and analysing data. As the adage goes, “rubbish in, rubbish out” – make sure that your data inputs are rock-solid.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Methodology Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS.

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS AND I HAVE GREATLY BENEFITED FROM THE CONTENT.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- How it works

Reliability and Validity – Definitions, Types & Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

A researcher must test the collected data before making any conclusion. Every research design needs to be concerned with reliability and validity to measure the quality of the research.

What is Reliability?

Reliability refers to the consistency of the measurement. Reliability shows how trustworthy is the score of the test. If the collected data shows the same results after being tested using various methods and sample groups, the information is reliable. If your method has reliability, the results will be valid.

Example: If you weigh yourself on a weighing scale throughout the day, you’ll get the same results. These are considered reliable results obtained through repeated measures.

Example: If a teacher conducts the same math test of students and repeats it next week with the same questions. If she gets the same score, then the reliability of the test is high.

What is the Validity?

Validity refers to the accuracy of the measurement. Validity shows how a specific test is suitable for a particular situation. If the results are accurate according to the researcher’s situation, explanation, and prediction, then the research is valid.

If the method of measuring is accurate, then it’ll produce accurate results. If a method is reliable, then it’s valid. In contrast, if a method is not reliable, it’s not valid.

Example: Your weighing scale shows different results each time you weigh yourself within a day even after handling it carefully, and weighing before and after meals. Your weighing machine might be malfunctioning. It means your method had low reliability. Hence you are getting inaccurate or inconsistent results that are not valid.

Example: Suppose a questionnaire is distributed among a group of people to check the quality of a skincare product and repeated the same questionnaire with many groups. If you get the same response from various participants, it means the validity of the questionnaire and product is high as it has high reliability.

Most of the time, validity is difficult to measure even though the process of measurement is reliable. It isn’t easy to interpret the real situation.

Example: If the weighing scale shows the same result, let’s say 70 kg each time, even if your actual weight is 55 kg, then it means the weighing scale is malfunctioning. However, it was showing consistent results, but it cannot be considered as reliable. It means the method has low reliability.

Internal Vs. External Validity

One of the key features of randomised designs is that they have significantly high internal and external validity.

Internal validity is the ability to draw a causal link between your treatment and the dependent variable of interest. It means the observed changes should be due to the experiment conducted, and any external factor should not influence the variables .

Example: age, level, height, and grade.

External validity is the ability to identify and generalise your study outcomes to the population at large. The relationship between the study’s situation and the situations outside the study is considered external validity.

Also, read about Inductive vs Deductive reasoning in this article.

Looking for reliable dissertation support?

We hear you.

- Whether you want a full dissertation written or need help forming a dissertation proposal, we can help you with both.

- Get different dissertation services at ResearchProspect and score amazing grades!

Threats to Interval Validity

| Threat | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Confounding factors | Unexpected events during the experiment that are not a part of treatment. | If you feel the increased weight of your experiment participants is due to lack of physical activity, but it was actually due to the consumption of coffee with sugar. |

| Maturation | The influence on the independent variable due to passage of time. | During a long-term experiment, subjects may feel tired, bored, and hungry. |

| Testing | The results of one test affect the results of another test. | Participants of the first experiment may react differently during the second experiment. |

| Instrumentation | Changes in the instrument’s collaboration | Change in the may give different results instead of the expected results. |

| Statistical regression | Groups selected depending on the extreme scores are not as extreme on subsequent testing. | Students who failed in the pre-final exam are likely to get passed in the final exams; they might be more confident and conscious than earlier. |

| Selection bias | Choosing comparison groups without randomisation. | A group of trained and efficient teachers is selected to teach children communication skills instead of randomly selecting them. |

| Experimental mortality | Due to the extension of the time of the experiment, participants may leave the experiment. | Due to multi-tasking and various competition levels, the participants may leave the competition because they are dissatisfied with the time-extension even if they were doing well. |

Threats of External Validity

| Threat | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reactive/interactive effects of testing | The participants of the pre-test may get awareness about the next experiment. The treatment may not be effective without the pre-test. | Students who got failed in the pre-final exam are likely to get passed in the final exams; they might be more confident and conscious than earlier. |

| Selection of participants | A group of participants selected with specific characteristics and the treatment of the experiment may work only on the participants possessing those characteristics | If an experiment is conducted specifically on the health issues of pregnant women, the same treatment cannot be given to male participants. |

How to Assess Reliability and Validity?

Reliability can be measured by comparing the consistency of the procedure and its results. There are various methods to measure validity and reliability. Reliability can be measured through various statistical methods depending on the types of validity, as explained below:

Types of Reliability

| Type of reliability | What does it measure? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Test-Retests | It measures the consistency of the results at different points of time. It identifies whether the results are the same after repeated measures. | Suppose a questionnaire is distributed among a group of people to check the quality of a skincare product and repeated the same questionnaire with many groups. If you get the same response from a various group of participants, it means the validity of the questionnaire and product is high as it has high test-retest reliability. |

| Inter-Rater | It measures the consistency of the results at the same time by different raters (researchers) | Suppose five researchers measure the academic performance of the same student by incorporating various questions from all the academic subjects and submit various results. It shows that the questionnaire has low inter-rater reliability. |

| Parallel Forms | It measures Equivalence. It includes different forms of the same test performed on the same participants. | Suppose the same researcher conducts the two different forms of tests on the same topic and the same students. The tests could be written and oral tests on the same topic. If results are the same, then the parallel-forms reliability of the test is high; otherwise, it’ll be low if the results are different. |

| Inter-Term | It measures the consistency of the measurement. | The results of the same tests are split into two halves and compared with each other. If there is a lot of difference in results, then the inter-term reliability of the test is low. |

Types of Validity

As we discussed above, the reliability of the measurement alone cannot determine its validity. Validity is difficult to be measured even if the method is reliable. The following type of tests is conducted for measuring validity.

| Type of reliability | What does it measure? | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Content validity | It shows whether all the aspects of the test/measurement are covered. | A language test is designed to measure the writing and reading skills, listening, and speaking skills. It indicates that a test has high content validity. |

| Face validity | It is about the validity of the appearance of a test or procedure of the test. | The type of included in the question paper, time, and marks allotted. The number of questions and their categories. Is it a good question paper to measure the academic performance of students? |

| Construct validity | It shows whether the test is measuring the correct construct (ability/attribute, trait, skill) | Is the test conducted to measure communication skills is actually measuring communication skills? |

| Criterion validity | It shows whether the test scores obtained are similar to other measures of the same concept. | The results obtained from a prefinal exam of graduate accurately predict the results of the later final exam. It shows that the test has high criterion validity. |

Does your Research Methodology Have the Following?

- Great Research/Sources

- Perfect Language

- Accurate Sources

If not, we can help. Our panel of experts makes sure to keep the 3 pillars of Research Methodology strong.

How to Increase Reliability?

- Use an appropriate questionnaire to measure the competency level.

- Ensure a consistent environment for participants

- Make the participants familiar with the criteria of assessment.

- Train the participants appropriately.

- Analyse the research items regularly to avoid poor performance.

How to Increase Validity?

Ensuring Validity is also not an easy job. A proper functioning method to ensure validity is given below:

- The reactivity should be minimised at the first concern.

- The Hawthorne effect should be reduced.

- The respondents should be motivated.

- The intervals between the pre-test and post-test should not be lengthy.

- Dropout rates should be avoided.

- The inter-rater reliability should be ensured.

- Control and experimental groups should be matched with each other.

How to Implement Reliability and Validity in your Thesis?

According to the experts, it is helpful if to implement the concept of reliability and Validity. Especially, in the thesis and the dissertation, these concepts are adopted much. The method for implementation given below:

| Segments | Explanation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All the planning about reliability and validity will be discussed here, including the chosen samples and size and the techniques used to measure reliability and validity. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Please talk about the level of reliability and validity of your results and their influence on values. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat is reliability and validity in research. Reliability in research refers to the consistency and stability of measurements or findings. Validity relates to the accuracy and truthfulness of results, measuring what the study intends to. Both are crucial for trustworthy and credible research outcomes. What is validity?Validity in research refers to the extent to which a study accurately measures what it intends to measure. It ensures that the results are truly representative of the phenomena under investigation. Without validity, research findings may be irrelevant, misleading, or incorrect, limiting their applicability and credibility. What is reliability?Reliability in research refers to the consistency and stability of measurements over time. If a study is reliable, repeating the experiment or test under the same conditions should produce similar results. Without reliability, findings become unpredictable and lack dependability, potentially undermining the study’s credibility and generalisability. What is reliability in psychology?In psychology, reliability refers to the consistency of a measurement tool or test. A reliable psychological assessment produces stable and consistent results across different times, situations, or raters. It ensures that an instrument’s scores are not due to random error, making the findings dependable and reproducible in similar conditions. What is test retest reliability?Test-retest reliability assesses the consistency of measurements taken by a test over time. It involves administering the same test to the same participants at two different points in time and comparing the results. A high correlation between the scores indicates that the test produces stable and consistent results over time. How to improve reliability of an experiment?

What is the difference between reliability and validity?Reliability refers to the consistency and repeatability of measurements, ensuring results are stable over time. Validity indicates how well an instrument measures what it’s intended to measure, ensuring accuracy and relevance. While a test can be reliable without being valid, a valid test must inherently be reliable. Both are essential for credible research. Are interviews reliable and valid?Interviews can be both reliable and valid, but they are susceptible to biases. The reliability and validity depend on the design, structure, and execution of the interview. Structured interviews with standardised questions improve reliability. Validity is enhanced when questions accurately capture the intended construct and when interviewer biases are minimised. Are IQ tests valid and reliable?IQ tests are generally considered reliable, producing consistent scores over time. Their validity, however, is a subject of debate. While they effectively measure certain cognitive skills, whether they capture the entirety of “intelligence” or predict success in all life areas is contested. Cultural bias and over-reliance on tests are also concerns. Are questionnaires reliable and valid?Questionnaires can be both reliable and valid if well-designed. Reliability is achieved when they produce consistent results over time or across similar populations. Validity is ensured when questions accurately measure the intended construct. However, factors like poorly phrased questions, respondent bias, and lack of standardisation can compromise their reliability and validity. You May Also LikeThe authenticity of dissertation is largely influenced by the research method employed. Here we present the most notable research methods for dissertation. This post provides the key disadvantages of secondary research so you know the limitations of secondary research before making a decision. This article presents the key advantages and disadvantages of secondary research so you can select the most appropriate research approach for your study. USEFUL LINKS LEARNING RESOURCES  COMPANY DETAILS

Home Market Research Reliability vs. Validity in Research: Types & Examples When it comes to research, getting things right is crucial. That’s where the concepts of “Reliability vs Validity in Research” come in. Imagine it like a balancing act – making sure your measurements are consistent and accurate at the same time. This is where test-retest reliability, having different researchers check things, and keeping things consistent within your research plays a big role. As we dive into this topic, we’ll uncover the differences between reliability and validity, see how they work together, and learn how to use them effectively. Understanding Reliability vs. Validity in ResearchWhen it comes to collecting data and conducting research, two crucial concepts stand out: reliability and validity. These pillars uphold the integrity of research findings, ensuring that the data collected and the conclusions drawn are both meaningful and trustworthy. Let’s dive into the heart of the concepts, reliability, and validity, to comprehend their significance in the realm of research truly. What is reliability?Reliability refers to the consistency and dependability of the data collection process. It’s like having a steady hand that produces the same result each time it reaches for a task. In the research context, reliability is all about ensuring that if you were to repeat the same study using the same reliable measurement technique, you’d end up with the same results. It’s like having multiple researchers independently conduct the same experiment and getting outcomes that align perfectly. Imagine you’re using a thermometer to measure the temperature of the water. You have a reliable measurement if you dip the thermometer into the water multiple times and get the same reading each time. This tells you that your method and measurement technique consistently produce the same results, whether it’s you or another researcher performing the measurement. What is validity?On the other hand, validity refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of your data. It’s like ensuring that the puzzle pieces you’re putting together actually form the intended picture. When you have validity, you know that your method and measurement technique are consistent and capable of producing results aligned with reality. Think of it this way; Imagine you’re conducting a test that claims to measure a specific trait, like problem-solving ability. If the test consistently produces results that accurately reflect participants’ problem-solving skills, then the test has high validity. In this case, the test produces accurate results that truly correspond to the trait it aims to measure. In essence, while reliability assures you that your data collection process is like a well-oiled machine producing the same results, validity steps in to ensure that these results are not only consistent but also relevantly accurate. Together, these concepts provide researchers with the tools to conduct research that stands on a solid foundation of dependable methods and meaningful insights. Types of ReliabilityLet’s explore the various types of reliability that researchers consider to ensure their work stands on solid ground. High test-retest reliabilityTest-retest reliability involves assessing the consistency of measurements over time. It’s like taking the same measurement or test twice – once and then again after a certain period. If the results align closely, it indicates that the measurement is reliable over time. Think of it as capturing the essence of stability. Inter-rater reliabilityWhen multiple researchers or observers are part of the equation, interrater reliability comes into play. This type of reliability assesses the level of agreement between different observers when evaluating the same phenomenon. It’s like ensuring that different pairs of eyes perceive things in a similar way. Internal reliabilityInternal consistency dives into the harmony among different items within a measurement tool aiming to assess the same concept. This often comes into play in surveys or questionnaires, where participants respond to various items related to a single construct. If the responses to these items consistently reflect the same underlying concept, the measurement is said to have high internal consistency. Types of validityLet’s explore the various types of validity that researchers consider to ensure their work stands on solid ground. Content validityIt delves into whether a measurement truly captures all dimensions of the concept it intends to measure. It’s about making sure your measurement tool covers all relevant aspects comprehensively. Imagine designing a test to assess students’ understanding of a history chapter. It exhibits high content validity if the test includes questions about key events, dates, and causes. However, if it focuses solely on dates and omits causation, its content validity might be questionable. Construct validityIt assesses how well a measurement aligns with established theories and concepts. It’s like ensuring that your measurement is a true representation of the abstract construct you’re trying to capture. Criterion validityCriterion validity examines how well your measurement corresponds to other established measurements of the same concept. It’s about making sure your measurement accurately predicts or correlates with external criteria. Differences between reliability and validity in researchLet’s delve into the differences between reliability and validity in research.

While both reliability and validity contribute to trustworthy research, they address distinct aspects. Reliability ensures consistent results, while validity ensures accurate and relevant results that reflect the true nature of the measured concept. Example of Reliability and Validity in ResearchIn this section, we’ll explore instances that highlight the differences between reliability and validity and how they play a crucial role in ensuring the credibility of research findings. Example of reliabilityImagine you are studying the reliability of a smartphone’s battery life measurement. To collect data, you fully charge the phone and measure the battery life three times in the same controlled environment—same apps running, same brightness level, and same usage patterns. If the measurements consistently show a similar battery life duration each time you repeat the test, it indicates that your measurement method is reliable. The consistent results under the same conditions assure you that the battery life measurement can be trusted to provide dependable information about the phone’s performance. Example of validityResearchers collect data from a group of participants in a study aiming to assess the validity of a newly developed stress questionnaire. To ensure validity, they compare the scores obtained from the stress questionnaire with the participants’ actual stress levels measured using physiological indicators such as heart rate variability and cortisol levels. If participants’ scores correlate strongly with their physiological stress levels, the questionnaire is valid. This means the questionnaire accurately measures participants’ stress levels, and its results correspond to real variations in their physiological responses to stress. Validity assessed through the correlation between questionnaire scores and physiological measures ensures that the questionnaire is effectively measuring what it claims to measure participants’ stress levels. In the world of research, differentiating between reliability and validity is crucial. Reliability ensures consistent results, while validity confirms accurate measurements. Using tools like QuestionPro enhances data collection for both reliability and validity. For instance, measuring self-esteem over time showcases reliability, and aligning questions with theories demonstrates validity. QuestionPro empowers researchers to achieve reliable and valid results through its robust features, facilitating credible research outcomes. Contact QuestionPro to create a free account or learn more! LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL MORE LIKE THIS Customer Marketing: The Best Kept Secret of Big BrandsJul 8, 2024  Positive Correlation: What It Is, Importance & How It WorksJul 5, 2024  Exit Interviews: Transforming Departures into Growth OpportunitiesJul 4, 2024  Techathon by QuestionPro: An Amazing Showcase of Tech BrillianceJul 3, 2024 Other categories

An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .