- UNO Criss Library

Social Work Research Guide

What is a research journal.

- Find Articles

- Find E-Books and Books

Reading an Academic Article

- Free Online Resources

- Reference and Writing

- Citation Help This link opens in a new window

Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

TIP: When possible, keep your research question(s) in mind when reading scholarly articles. It will help you to focus your reading.

Title : Generally are straightforward and describe what the article is about. Titles often include relevant key words.

Abstract : A summary of the author(s)'s research findings and tells what to expect when you read the full article. It is often a good idea to read the abstract first, in order to determine if you should even bother reading the whole article.

Discussion and Conclusion : Read these after the Abstract (even though they come at the end of the article). These sections can help you see if this article will meet your research needs. If you don’t think that it will, set it aside.

Introduction : Describes the topic or problem researched. The authors will present the thesis of their argument or the goal of their research.

Literature Review : May be included in the introduction or as its own separate section. Here you see where the author(s) enter the conversation on this topic. That is to say, what related research has come before, and how do they hope to advance the discussion with their current research?

Methods : This section explains how the study worked. In this section, you often learn who and how many participated in the study and what they were asked to do. You will need to think critically about the methods and whether or not they make sense given the research question.

Results : Here you will often find numbers and tables. If you aren't an expert at statistics this section may be difficult to grasp. However you should attempt to understand if the results seem reasonable given the methods.

Works Cited (also be called References or Bibliography ): This section comprises the author(s)’s sources. Always be sure to scroll through them. Good research usually cites many different kinds of sources (books, journal articles, etc.). As you read the Works Cited page, be sure to look for sources that look like they will help you to answer your own research question.

Adapted from http://library.hunter.cuny.edu/research-toolkit/how-do-i-read-stuff/anatomy-of-a-scholarly-article

A research journal is a periodical that contains articles written by experts in a particular field of study who report the results of research in that field. The articles are intended to be read by other experts or students of the field, and they are typically much more sophisticated and advanced than the articles found in general magazines. This guide offers some tips to help distinguish scholarly journals from other periodicals.

CHARACTERISTICS OF RESEARCH JOURNALS

PURPOSE : Research journals communicate the results of research in the field of study covered by the journal. Research articles reflect a systematic and thorough study of a single topic, often involving experiments or surveys. Research journals may also publish review articles and book reviews that summarize the current state of knowledge on a topic.

APPEARANCE : Research journals lack the slick advertising, classified ads, coupons, etc., found in popular magazines. Articles are often printed one column to a page, as in books, and there are often graphs, tables, or charts referring to specific points in the articles.

AUTHORITY : Research articles are written by the person(s) who did the research being reported. When more than two authors are listed for a single article, the first author listed is often the primary researcher who coordinated or supervised the work done by the other authors. The most highly‑regarded scholarly journals are typically those sponsored by professional associations, such as the American Psychological Association or the American Chemical Society.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY : Articles submitted to research journals are evaluated by an editorial board and other experts before they are accepted for publication. This evaluation, called peer review, is designed to ensure that the articles published are based on solid research that meets the normal standards of the field of study covered by the journal. Professors sometimes use the term "refereed" to describe peer-reviewed journals.

WRITING STYLE : Articles in research journals usually contain an advanced vocabulary, since the authors use the technical language or jargon of their field of study. The authors assume that the reader already possesses a basic understanding of the field of study.

REFERENCES : The authors of research articles always indicate the sources of their information. These references are usually listed at the end of an article, but they may appear in the form of footnotes, endnotes, or a bibliography.

PERIODICALS THAT ARE NOT RESEARCH JOURNALS

POPULAR MAGAZINES : These are periodicals that one typically finds at grocery stores, airport newsstands, or bookstores at a shopping mall. Popular magazines are designed to appeal to a broad audience, and they usually contain relatively brief articles written in a readable, non‑technical language.

Examples include: Car and Driver , Cosmopolitan , Esquire , Essence , Gourmet , Life , People Weekly , Readers' Digest , Rolling Stone , Sports Illustrated , Vanity Fair , and Vogue .

NEWS MAGAZINES : These periodicals, which are usually issued weekly, provide information on topics of current interest, but their articles seldom have the depth or authority of scholarly articles.

Examples include: Newsweek , Time , U.S. News and World Report .

OPINION MAGAZINES : These periodicals contain articles aimed at an educated audience interested in keeping up with current events or ideas, especially those pertaining to topical issues. Very often their articles are written from a particular political, economic, or social point of view.

Examples include: Catholic World , Christianity Today , Commentary , Ms. , The Militant , Mother Jones , The Nation , National Review , The New Republic , The Progressive , and World Marxist Review .

TRADE MAGAZINES : People who need to keep up with developments in a particular industry or occupation read these magazines. Many trade magazines publish one or more special issues each year that focus on industry statistics, directory lists, or new product announcements.

Examples include: Beverage World , Progressive Grocer , Quick Frozen Foods International , Rubber World , Sales and Marketing Management , Skiing Trade News , and Stores .

Literature Reviews

- Literature Review Guide General information on how to organize and write a literature review.

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It Contains two sets of questions to help students review articles, and to review their own literature reviews.

- << Previous: Find E-Books and Books

- Next: Statistics >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 11:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unomaha.edu/social_work

- Library Catalogue

What is a journal article? (What is an article?)

Definitions.

Journal articles are shorter than books and written about very specific topics.

A journal is a collection of articles (like a magazine) that is published regularly throughout the year. Journals present the most recent research, and journal articles are written by experts, for experts. They may be published in print or online formats, or both.

Sample images

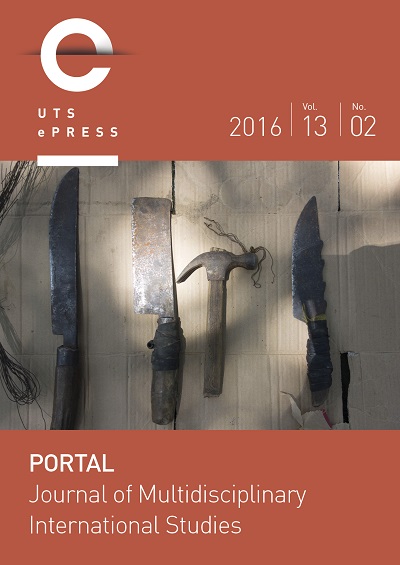

The front cover of a sample academic journal ( PORTAL: Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies ). Note that it includes a year, as well as "Vol." (for "Volume") and "No." (for "Number"). Because journals are published regularly, this information identifies different issues (like month and year on a popular magazine).

A sample table of contents from the same academic journal, listing the articles that appear in this issue. (Note: When accessing journals online, articles are usually available as separate PDF documents.)

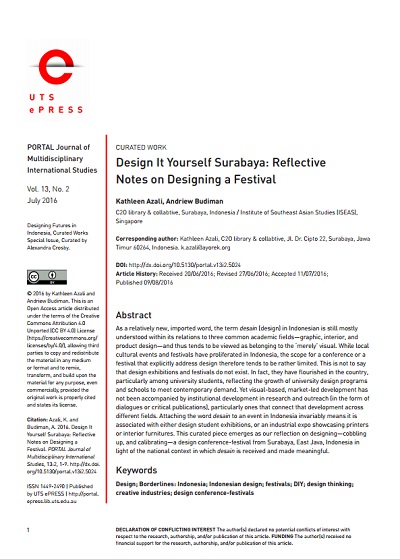

A sample article (first page) from the same academic journal:

More information

Finding academic or scholarly journal articles Tips for searching for journal articles in the Library.

What is a scholarly (or peer-reviewed) journal ? For the differences between scholarly journals, magazines, and trade publications -- and when to use them.

Finding and evaluating sources Searching for and evaluating sources on the open web, with tips for evaluating all sources, including journals and journal articles.

What is peer review? What is a peer-reviewed journal? What peer review means and how to tell if a journal is peer-reviewed.

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

What is a Research Journal? A Complete Guide to Publishing in Research Journal

Introduction

Characteristics of reputable research journals, types of research journals, why publish in research journals, selecting the right research journal, navigating the peer-review process of research journal, ethics in research journal publishing, open access journals, research journal examples.

Research journals are the cornerstone of academic communication and play a vital role in the advancement of research fields. They serve as a platform for researchers to share their findings, exchange ideas, and contribute to the collective knowledge of the academic community. Research journals facilitate the dissemination of new knowledge, promote critical thinking, and foster academic discourse.

For example, in the field of medicine, prestigious journals like The New England Journal of Medicine , The Lancet, and JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) publish groundbreaking research that has a significant impact on clinical practice and patient care. Research published in these journals can influence guidelines, policies, and treatment protocols, shaping the field of medicine and improving healthcare outcomes.

Similarly, in the field of computer science, journals such as IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence , ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction , and Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research publish cutting-edge research on artificial intelligence, machine learning, and human-computer interaction. Research published in these journals can shape the development of new technologies, algorithms, and applications, driving advancements in the field of computer science.

The article will provide an overview of research journals and their significance for research scholars, highlighting the importance of publishing in reputable journals to contribute to the academic community, gain recognition, and advance their careers. It will also discuss various aspects of research journals, including the peer-review process, ethical considerations, and the growing trend of open-access journals, to help research scholars make informed decisions when choosing where to publish their research.

What are Research Journals?

Research journals are periodical publications that publish original research articles, reviews, and other scholarly content related to a specific academic discipline or interdisciplinary field. They serve as a platform for researchers to communicate their findings and share their work with the broader academic community.

- Peer-review process: Reputable research journals typically employ a rigorous peer-review process, where submitted manuscripts are reviewed by experts in the field before they are accepted for publication. Peer review helps ensure the quality, accuracy, and validity of the research published in the journal.

For example, journals like Nature, Science, and Cell are well-known for their stringent peer-review process, where manuscripts undergo thorough evaluation by a panel of experts in the respective fields before they are accepted for publication.

- Editorial board: Reputable research journals have an editorial board comprising experts in the field who oversee the journal’s operations, provide guidance on its direction, and ensure the quality and integrity of the published content. The editorial board may include editors-in-chief, associate editors, and editorial reviewers who collectively make decisions on manuscript submissions.

For example, journals like Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Finance, and Journal of Biological Chemistry have distinguished editorial boards comprised of leading scholars and researchers in their respective fields.

- Indexing: Reputable research journals are often indexed in well-known databases and indexing services, which enhance their visibility and accessibility to the academic community. Indexing services, such as PubMed , Scopus , and Web of Science , ensure that research published in these journals is easily discoverable and citable.

For example, journals like Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, and Journal of Materials Science are indexed in popular databases, making them widely recognized and cited within their respective fields.

- Disciplinary journals: These journals focus on specific academic disciplines, such as physics, chemistry, sociology, or psychology, and publish research articles and content within that particular discipline.

For example, journals like Journal of Neuroscience, Journal of Marketing, and Journal of Political Economy are disciplinary journals that cater to specific fields of study.

- Interdisciplinary journals: These journals publish research articles and content that span across multiple disciplines, bringing together research from different fields and encouraging interdisciplinary collaborations.

For example, journals like Science Advances, PLOS ONE, and Frontiers in Psychology are interdisciplinary journals that cover a wide range of topics and attract research from multiple disciplines.

- Open access journals: These journals make research articles freely available to readers without any paywalls or subscription fees, ensuring that research is accessible to a wider audience.

For example, journals like PLOS Biology, BioMed Central, and eLife are open access journals that provide unrestricted access to research content, promoting knowledge dissemination and democratizing access to scholarly information.

Understanding the different types of research journals and their characteristics can help research scholars choose the most appropriate journal for publishing their research, considering the scope, readership, and impact of their work.

Publishing research in reputable journals offers numerous benefits to research scholars, including:

- Academic recognition: Publishing in reputable research journals can enhance the visibility and recognition of researchers’ work within the academic community. Research articles published in well-established journals are often considered as valuable contributions to the field, which can lead to increased credibility and recognition among peers.

For example, publishing a research article in a prestigious journal like Nature or Science can significantly boost the academic reputation of the researcher and may lead to invitations for collaborations, speaking engagements, and other opportunities.

- Credibility: Publishing in reputable research journals adds credibility to the research findings. The peer-review process followed by reputable journals ensures that the research articles are rigorously evaluated by experts in the field, validating the quality and reliability of the research.

For example, research published in journals like The Lancet, Journal of the American Chemical Society, or IEEE Transactions on Information Theory is considered to be of high quality and reliable, which can strengthen the credibility of the research findings.

- Visibility: Publishing in reputable research journals increases the visibility of research work among the wider academic community. Many reputable journals have a large readership and broad reach, which can help researchers disseminate their findings to a larger audience.

For example, research articles published in journals like Nature Communications, Journal of Applied Physics, or Journal of Marketing Research are often widely read and cited by researchers, which can enhance the visibility and impact of the research.

- Career advancement: Publishing in reputable research journals can contribute to career advancement for research scholars. Publications in well-established journals are often considered important for securing academic positions, promotions, and research grants.

For example, having a strong publication record in reputable journals can be a significant factor in obtaining tenure or promotion in academia, securing funding from funding agencies, and advancing the career trajectory of a researcher.

- Building academic networks: Publishing in research journals can facilitate networking opportunities with fellow researchers, experts, and scholars in the field. It can lead to collaborations, discussions, and interactions that can foster the growth of research scholars’ academic networks.

For example, researchers who publish in reputable journals often receive invitations to conferences, workshops, and other academic events, providing opportunities to connect with other researchers, exchange ideas, and collaborate on future research projects.

- Promoting scientific rigor and integrity: Research journals play a crucial role in promoting scientific rigor and integrity through the peer-review process. The peer-review process helps ensure that research articles published in reputable journals are based on robust methodology, reliable data, and valid conclusions.

For example, the peer-review process followed by journals like Journal of Clinical Investigation, Journal of Experimental Medicine, or Psychological Bulletin ensures that the research articles are thoroughly evaluated by experts in the respective fields, maintaining the standards of scientific rigor and integrity.

Selecting the appropriate research journal for publishing research is a critical step that can impact the visibility, credibility, and impact of the research. Here are some tips for researchers to consider when selecting a research journal:

- Scope, readership, and impact factor: It’s essential to carefully evaluate the scope and readership of a research journal to ensure that it aligns with the research topic and target audience. Researchers should also consider the journal’s impact factor, which is a measure of the journal’s influence and citation rate in the field.

For example, if a researcher is conducting research in the field of environmental science, a journal like Environmental Science & Technology or Environmental Research would be more appropriate compared to a general science journal like Science or Nature.

- Publishing policies, submission guidelines, and copyright policies: Researchers should thoroughly review the publishing policies, submission guidelines, and copyright policies of research journals before submitting their research. This includes understanding the journal’s requirements for formatting, word count, referencing style, and other submission guidelines.

For example, some journals may have specific requirements for data sharing, ethical considerations, or authorship, which researchers need to be aware of and adhere to during the submission process.

- Predatory journals: It’s crucial to avoid predatory journals, which are low-quality or fraudulent journals that lack proper peer-review processes and editorial standards. Publishing in predatory journals can have negative consequences on the credibility and impact of the research.

For example, researchers should be cautious of journals that spam their email inbox with solicitation emails, promise rapid publication with minimal peer review, or charge exorbitant publication fees without providing proper editorial services.

I have written an article on Avoiding Predatory Conferences and Journals: A Step by Step Guide for Researchers . This article will help you in avoiding predatory conferences and journals.

Publishing in reputable journals with high editorial standards and a rigorous peer-review process ensures that the research undergoes a thorough evaluation and maintains the integrity and quality of the research. Researchers should aim to publish in journals that are indexed in reputable databases, recognized by their peers, and have a good reputation in their respective fields.

By selecting the right research journal, understanding the publishing policies and submission guidelines, and avoiding predatory journals, researchers can enhance the visibility, credibility, and impact of their research publications.

The peer-review process is a crucial step in the publication process of research journals. It involves the evaluation of research papers by experts in the field to ensure the quality, validity, and rigor of the research. Here’s what researchers need to know about navigating the peer-review process:

- Peer-review process and its significance: Researchers should explain the peer-review process and emphasize its significance in ensuring the quality and validity of research. Peer-review helps to identify and rectify any potential flaws, errors, or biases in the research, and ensures that only high-quality research is published in reputable journals.

For example, the peer-review process typically involves submission of the research paper to the journal, followed by evaluation by experts in the field who review the research for its originality, methodology, results, and conclusions. Reviewers provide feedback, suggestions, and comments to the authors, which help in improving the research before final publication.

- Types of peer-review: Researchers should discuss the different types of peer-review, such as single-blind, double-blind, and open peer-review. In single-blind peer-review, the reviewer’s identity is concealed from the authors, while in double-blind peer-review, the identities of both reviewers and authors are concealed. In open peer-review, the identities of both reviewers and authors are disclosed.

For example, in single-blind peer-review, the reviewer remains anonymous, which can help reduce biases, while in double-blind peer-review, both the reviewer and author remain anonymous, which can further reduce potential biases. Open peer-review promotes transparency and accountability, as the identities of both reviewers and authors are disclosed, allowing for a more collaborative and constructive feedback process.

- Responding to reviewer comments and revising research papers: Researchers should provide tips on how to respond to reviewer comments and revise research papers accordingly. It’s important to carefully consider and address all reviewer comments in a respectful and professional manner. Researchers should revise the research paper based on the feedback received, provide clarifications, and make necessary changes to improve the quality and validity of the research.

For example, researchers should avoid being defensive or dismissive of reviewer comments and instead view them as opportunities for improvement. It’s important to provide well-justified responses to reviewer comments and revise the research paper accordingly to address any concerns or suggestions raised by the reviewers.

Navigating the peer-review process can be challenging, but it is a crucial step in ensuring the quality and validity of research publications. By understanding the peer-review process, familiarizing oneself with different types of peer-review, and responding to reviewer comments in a constructive manner, researchers can enhance the chances of their research being accepted and published in reputable research journals.

I have written an article on Expert Tips for Responding to Reviewers’ Comments on Your Research Paper . This article will help you in replying to reviewer’s comments effectively.

Ethical considerations in publishing research are critical to ensure the integrity, credibility, and transparency of the scientific literature. Researchers should discuss the following ethical aspects of publishing research:

- Plagiarism: Researchers should emphasize the importance of avoiding plagiarism, which involves presenting someone else’s work, ideas, or words as one’s own without proper attribution. Plagiarism can result in serious consequences, including retraction of published papers, loss of credibility, and damage to reputation.

For example, researchers should highlight the need to properly cite and reference all sources used in their research, including text, figures, tables, and other scholarly works. They should also be aware of different types of plagiarism, such as verbatim copying, paraphrasing without proper attribution, and self-plagiarism, and take steps to avoid them.

Read my article on The Consequences of Plagiarism: What You Need to Know? . This article will help you to understand the consequences of plagiarism.

- Authorship: Researchers should discuss the principles of authorship and highlight the importance of giving proper credit to all individuals who have made substantial contributions to the research. Authorship should be based on meaningful intellectual contributions to the research, and all authors should be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the published work.

For example, researchers should explain the criteria for authorship, such as conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting and revising the manuscript. They should also discuss the need for obtaining consent from all authors before submitting the research paper for publication.

Please refer my blog post on Does Author Position in a Research Paper Matter? . This blog will help you in deciding the authorship and giving proper credit to the contributors of the research work in research paper.

- Conflicts of interest: Researchers should highlight the need to disclose any conflicts of interest that could potentially bias the research findings or its interpretation. Conflicts of interest can arise from financial, personal, or professional relationships that may influence the research design, conduct, analysis, or reporting.

For example, researchers should disclose any funding sources, affiliations, or relationships that may have influenced the research. They should also explain how they have addressed or managed any conflicts of interest to ensure the integrity and transparency of the research.

- Data integrity: Researchers should emphasize the importance of maintaining data integrity throughout the research process, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and reporting. Data should be accurate, complete, and transparent, and any manipulation, fabrication, or falsification of data is unacceptable.

For example, researchers should explain the need for proper data management, including data storage, backup, and documentation. They should also highlight the importance of data sharing and reproducibility to promote transparency and rigor in scientific research.

- Ethical guidelines: Researchers should highlight the importance of adhering to ethical guidelines set by reputable organizations, such as the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) . These guidelines provide standards and best practices for authors, editors, and reviewers in publishing research.

For example, researchers should familiarize themselves with the ethical guidelines provided by COPE and ICMJE , which cover various aspects of research publication, including authorship, conflicts of interest, data integrity, and plagiarism. Adhering to these guidelines helps ensure the ethical conduct of research and enhances the credibility and integrity of published research.

Adhering to ethical considerations in publishing research is essential to maintain the integrity, credibility, and transparency of the scientific literature. By avoiding plagiarism, giving proper credit to authors, disclosing conflicts of interest, maintaining data integrity, and following ethical guidelines, researchers can contribute to responsible and ethical research publishing practices.

Open access journals are a type of research journal that provides free and unrestricted access to research articles online, without the need for a subscription or paywall. Here are some points to consider when discussing open-access journals:

- Concept of open access journals: Open access journals aim to make research findings widely accessible to the global community, removing barriers to accessing scholarly knowledge. This means that anyone, regardless of their institutional affiliation or financial resources, can freely access, read, download, and share research articles published in open-access journals.

For example, researchers should discuss the importance of open-access journals in democratizing access to scientific knowledge, particularly for researchers and readers from developing countries or institutions with limited access to subscription-based journals. Open-access journals provide an opportunity for broader dissemination of research findings, leading to increased visibility and potential impact.

- Types of open access models: Open access journals can operate under different models, including gold, green, and hybrid open access.

- Gold open access: In the gold open access model, the research articles are published in open-access journals that make articles freely available to readers immediately upon publication. In this model, the costs of publication are typically covered by article processing charges (APCs), which are paid by the authors or their institutions.

- Green open access: In the green open access model, researchers self-archive or deposit their accepted manuscripts in a repository or an institutional repository after publication in a subscription-based journal. These manuscripts are made freely accessible to readers after an embargo period or without any embargo, depending on the publisher’s policies.

- Hybrid open access: In the hybrid open access model, a journal may offer both open-access and subscription-based options. In this model, authors can choose to pay APCs to make their individual articles freely available while other articles remain behind a subscription paywall.

For example, researchers should explain the differences between these open-access models and how they affect the availability, visibility, and cost of accessing research articles. They should also discuss the implications of each model for researchers, institutions, and readers, including the potential benefits and limitations.

- Potential challenges and criticisms of open-access journals: Despite the advantages of open-access journals, there are also potential challenges and criticisms associated with them.

- Funding and sustainability: One challenge of open-access journals is the need to cover the costs of publication, typically through APCs. This can be a barrier for researchers or institutions with limited funding resources, leading to concerns about the sustainability of open-access journals.

- Quality and credibility: Another criticism of open-access journals is the perception that they may have lower quality or less rigorous peer-review processes compared to subscription-based journals. This can raise concerns about the credibility and reliability of research published in open-access journals.

- Predatory publishing: Open-access journals have also been associated with the rise of predatory publishing, where unethical publishers charge high APCs but provide little or no peer review or editorial oversight. This can result in low-quality or even fraudulent research being published in open-access journals.

Open-access journals offer advantages in terms of wider accessibility and visibility of research findings, but they also come with potential challenges and criticisms. Researchers should be aware of different open-access models, discuss the advantages and limitations of open-access journals, and carefully consider the quality and credibility of the journals they choose to publish their research in.

Visit my article on Open Access Journals: What do you Need to Know as a Researcher? . This article will help you in understanding the way in which open-access journals function.

One more article I have written about Avoiding Predatory Conferences and Journals: A Step by Step Guide for Researchers . This artcle will help you in avoiding predatory journal publications.

Here’s the list of open access and subscription-based journal examples.

- Open Access Journals: These journals provide free, unrestricted access to their content online. They typically do not charge readers or institutions for access and allow users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles.

- Subscription-Based Journals: These journals require a subscription or payment to access their content. Readers or institutions must pay for access, either through individual subscriptions, institutional licenses, or pay-per-view options.

Publishing in research journals is a crucial step for research scholars to share their findings, establish their reputation, and contribute to the scholarly community. Carefully selecting reputable research journals, navigating the peer-review process, adhering to ethical considerations, and understanding open access options are important aspects of publishing research. By following best practices and contributing to reputable research journals, research scholars can make meaningful contributions to the advancement of knowledge in their fields and contribute to the scholarly community.

Upcoming Events

- Visit the Upcoming International Conferences at Exotic Travel Destinations with Travel Plan

- Visit for Research Internships Worldwide

Recent Posts

- These Institutes Offer Remote Research/Academic Internships

- How to Include Your Journal in the UGC-CARE List? A Guide for Publishers

- Understanding UGC CARE Journals: A Comprehensive Guide

- Top 10 AI-Based Research Paper Abstract Generators

- EditPad Research Title Generator: Is It Helpful to Create a Title for Your Research?

- All Blog Posts

- Research Career

- Research Conference

- Research Internship

- Research Journal

- Research Tools

- Uncategorized

- Research Conferences

- Research Journals

- Research Grants

- Internships

- Research Internships

- Email Templates

- Conferences

- Blog Partners

- Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2024 Research Voyage

Design by ThemesDNA.com

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

What are Scholarly Journals?: Introduction

- Introduction

- Get Some Practice!

DEFINITION 1

Periodical: A generic term meaning any type of publication that is published more than once a year. Magazines, newspapers, newsletters, and journals are all periodicals.

- Cheetahs on the Edge This is an example of a popular magazine article.

DEFINITION 2

Scholarly Journal : A special type of periodical preferred by researchers. Your professor may use any of the terms below, but they all mean the same thing—scholarly journals!

- academic journals

- juried publications

- original research

- primary research

- refereed publications

- Large Carnivore Menus: Factors Affecting Hunting Decisions by Cheetahs in the Serengeti This is an example of a scholarly journal article.

WHAT MAKES SCHOLARLY JOURNALS SPECIAL?

- S cholarly journals exist in order to make results of original research done by scholars readily available to other scholars and researchers.

- O nly the person or people who actually did the research can submit an article for publication (no second-hand information).

- E ach article submitted is carefully examined by several reviewers who are experts and researchers in the relevant field, the peers of the author (peer-review process), before being accepted by a board of editors for publication.

Therefore, the quality of the information contained in scholarly journals is more reliable and of higher quality than the information in ordinary magazines. It also is more complete. While an ordinary magazine may have an article that talks about the researchers interested in starfish and what they have been doing, you will not get the full details of the experiments or research conducted. A scholarly journal article written by the starfish researchers will tell you everything.

- When the Last Star Goes Out This is an example of a popular magazine article.

- Up in Arms: Immune and Nervous System Response to Sea Star Wasting Disease This is an example of a scholarly journal article.

HOW CAN I RECOGNIZE THEM?

- No advertisements

- Articles are lengthy

- Articles have abstracts/summaries at the beginning

- The language used is more complex than magazine articles

- Articles have bibliographies/references at the end

HOW DO I GET THEM?

M ost of the library's databases allow you to limit your search results to scholarly journals one way or another.

Look for a box to click on the search screen or a menu option to the side of your list of results.

Ask a librarian for assistance!

- Library Research Assistance In person - walk ins In person - scheduled appointments By phone By live chat By email By text By 24/7 live chat

FURTHER HELP ONLINE

View our short video tutorials:

- What are Scholarly Journals?

- Popular and Scholarly Sources: The Information Cycle

- Peer Review

- Next: Get Some Practice! >>

- Last Updated: Apr 6, 2023 8:16 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csusb.edu/scholarlyjournals

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

Guide to Scholarly Articles

Getting started, what makes an article scholarly, why does this matter.

- Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

- Types of Scholarly Articles

- Anatomy of Scholarly Articles

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarship is a conversation.

That conversation is often found in the form of published materials such as books, essays, and articles. Here, we will focus on scholarly articles because scholarly articles often contain the most current scholarly conversation.

After reading through this guide on scholarly articles you will be able to identify and describe different types of scholarly articles. This will allow you to navigate the scholarly conversation more effectively which in turn will make your research more productive.

The distinguishing feature of a scholarly article is not that it is without errors; rather, a scholarly article is distinguished by a few characteristics which reduce the likelihood of errors. For our purposes, those characteristics are expert authors , peer-review , and citations .

- Expert Authors - Authority is constructed and contextual. In other words it is built through academic credentialing and lived experience. Scholarly articles are written by experts in their respective fields rather than generalists. Expertise often comes in the form of academic credentials. For example, an article about the spread of various diseases should be written by someone with credentials and experience in immunology or public health.

- Peer-review - Peer-review is the process whereby scholarly articles are vetted and improved. In this process an author submits an article to a journal for publication. However, before publication, an editor of the journal will send the article to other experts in the field to solicit their informed and professional opinions of it. These reviewers (sometimes called referees) will give the editor feedback regarding the quality of the article. Based on this process, articles may be published as is, published after specific changes are made, or not published at all.

- Citations - One of the key differences between scholarly articles and other kinds of articles is that the former contain citations and bibliographies. These citations allow the reader to follow up on the author's sources to verify or dispute the author's claim.

There is a well-known axiom that says "Garbage in, garbage out." In the context of research this means that the quality of your research output is dependent on the information sources that go into you own research. Generally speaking, the information found in scholarly articles is more reliable than information found elsewhere. It is important to identify scholarly articles and prioritize them in your own research.

- Next: Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 8:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/scholarly-articles

_Biology: What is a Journal Article?

- About this Guide

- Research Process

- Choosing a Research Topic

- Brainstorm for Ideas

- Why Databases?

- Biology Resources

- Keyword Development

- Reviewing Search Strategies

- Evaluating Information

- What is a Journal Article?

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Finding Books

- Interlibrary Loan

- Finding Streaming Videos

- Citing Sources

- Getting Research Help

What are Journal Articles?

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

Academic journal articles are reports of an expert's original research, analysis, or review of the research available on a topic . These specialized reports are published in journals, which are publications aimed at professionals and scholars.

Here is a link to a tutorial developed by North Carolina State University Libraries that shows which parts make up a journal article, such as the title, author, abstract, introduction, publication information, charts and graphs, conclusion, and references.

In general, journal articles usually have the following parts:

- Introduction

- Tables and/or figures

What are Periodical Articles?

A periodical is a collection of articles and images about diverse topics of popular interest and current events, or diverse interests and current events in a subject, like science or history. There are many types of periodicals.

Popular magazines and newspapers contain articles that usually are written by journalists and are geared toward the average adult . Use these to stay updated on current news in your area and as a tool to give you ideas for topics to research for an academic paper.

Academic or scholarly journals contain articles that are written by scholars and are geared toward specialists or experts in a specific field. Use these to research deeply into specific areas. These are often used for academic papers and may require you to use a dictionary. Here is a tutorial about how to read these very specific articles: http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/scholarly-articles/

Journal Article Search Tips

LImit your results to articles that are peer-reviewed and from the last five years , unless you need research for historical purposes.

Read the abstract, or summary, of a journal article to help you decide if it's an article you'd like to pursue. Look for important words the author uses in the summary for ideas for keywords . Sometimes there is also a list of keywords underneath an abstract.

Journals are not always found freely online . As a Merced College student, however, you have free access to academic journals through the library databases or Interlibrary Loan.

Because these are professional sources of information, journal articles are not the best resources to use for basic or background information . While experts do use statistics in their reports, if you need specific statistics there are more direct resources you can use, rather than digging through the database. These statistics are often available for free online or in library reference books.

How to Read a Journal Article Result

- How to Read a Journal Article Citation

Use this handout to help you figure out the parts of a journal article record. This will help you when you need to put your works cited page together.

- How to "Pre-Read" an academic article This video will help you to "pre-read" or put an article in context so you are able to read it more easily. It's a learned skill!

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Reading Scholarly Articles >>

- Last Updated: Feb 12, 2024 12:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mccd.edu/_Biology

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Article Types: What's the Difference Between Newspapers, Magazines, and Journals?

- Definitions

What Does it Mean?

- Choosing What's Best

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Trade Magazine/Journal Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Newsletter Articles

Article : Much shorter than a book, an article can be as short as a paragraph or two or as long as several dozen pages. Articles can address any topic that the author decides to explore and can reflect opinion, news, research, reviews, instruction, nearly any focus. Articles appear in newspapers, magazines, trade publication, journals, and even in books. Because of their relative brevity, articles typically are used to provide up-to-date information on a wide variety of topics.

Book Review : A usually brief article that provides an evaluation and appreciation of a book. A review might assess the importance of a book's contributions to a particular field of study or might make recommendations to potential readers of the book. Reviews of fiction will usually comment on originality, style, and readability. While an important tool for helping a researcher assess the value of a book to his or her research topic, a book review, by itself, is usually not sufficient for use as a source in a research project.

Issue : A single, regular publication of a journal, magazine, newspaper, newsletter, or trade publication. A magazine or journal that publishes monthly will have twelve issues in a year. News magazines like Time and Newsweek publish weekly and will have 52 issues in a year. Newspapers might publish daily or weekly. A daily will have 365 issues in a year. Issues are usually numbered, so a journal that publishes twelve issues in a year starting with January will number each issue sequentially (issue 1, January; issue 2, February; issue 3, March; etc.).

Journal : A regularly published collection of articles that focus on topics specific to a particular academic discipline or profession. Journals might be published monthly, bi-monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, or even annually. Probably the most common publication frequency is monthly and quarterly. Journal articles are typically of substantial length (often more than 10 pages) and usually reflect research, whether it be surveys of existing research or discussions of original research. Most journal articles will be prefaced with an abstract and will include extensive documentation within the article or at the end of the article. Most research begins with a survey of existing literature on a topic and proceeds with the development of new ideas or new research into a topic. Articles are usually written by experts in their fields, although journals might also publish letters from their readership commenting on articles that have been published in previous issues. Journals might also include opinion articles or editorials. Examples of journals include Journal of the American Medical Association, American Sociological Review, Psychological Reports, Publications of the Modern Language Association, Educational Research Quarterly, and Evolutionary Biology.

Literature Review : An important part of nearly any research project, a literature review consists of a survey of previously published or non-published materials that focus on a particular subject under investigation. For example, a researcher looking into whether there is a relationship between musical aptitude and academic achievement in elementary age students would begin by looking for articles, books, and other materials that reflected previous research into this topic. The function of the review is to identify what is already known about the topic and to provide a knowledge foundation for the current study.

Magazine : A regularly published collection of articles that might focus on any topic in general or on topics of interest to a specific group, such as sports fans or music fans or home decorators. Magazines might be published weekly, monthly, semi-monthly or only several times a year. More commonly, magazines are published weekly or monthly. Articles in magazines are typically written for the general reading public and don't reflect in-depth research (an exception might be an investigative report written in a news magazine that involved weeks or months of research and interviews to complete). Most magazine articles do not list references and are written by the magazine's own staff writers. In general, magazine articles are easy to read, are fairly brief in length, and may include illustrations or photographs. Magazines also rely heavily on advertisements targeted to consumers as a source of revenue. Examples of magazines include Time, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Popular Mechanics, Car and Driver, Interview, Good Housekeeping, Elle, GQ, and Sports Illustrated.

Newsletter : A regularly published collection of brief news articles of interest to members of a particular community. Professional associations might issue newsletters to keep their membership up to date. Businesses and schools might issue newsletters to keep their constituents up to date. Nearly any type of organization or society might have its own newsletter. Articles in newsletters are typically brief, and the entire newsletter itself might be only half a dozen pages in length. These are usually internal publications that have interest mainly to people who participate in the activities of the issuing body. They are frequently used to inform members of an organization of upcoming events. Examples of newsletters include 401(k) Advisor, Adult Day Services Letter, Black History News & Notes, Credit Card Weekly, Education Business Weekly, Music Critics Association Newsletter, and Student Aid News.

Newspaper : A regularly published collection of fairly brief articles that provide updates on current events and interests. Newspapers are generally published daily, weekly, and bi-weekly, although they may have less regular publication schedules. Most major newspapers publish daily, with expanded coverage on the weekends. Newspapers can be national or international in focus or might be targeted strictly to a particular community or locality. Newspaper articles are written largely by newspaper staff and editors and often do not provide authors' names. Many of the articles appearing in national, international, and regional papers are written by various wire service writers and are nationally or internationally syndicated. Examples of wire services are Reuters and the Associated Press. Newspapers rely on advertising for a part of their income and might also include photographs and even full color illustrations of photos. A common feature of most newspapers is its editorial page, where the editors express opinions on timely topics and invite their readers to submit their opinions. Examples of newspapers include New York Times, Times of London, Florida Times-Union, Tampa Tribune, Denver Post, Guardian, and USA Today.

Peer Reviewed/Refereed Journal : Most academic/scholarly journals use subject experts or "peers" to review articles being considered for publication. Reviewers will carefully examine articles to ensure that they meet journal criteria for subject matter and style. The process ensures that articles are appropriate to a particular journal and that they are of the highest quality.

Trade Journal : A regularly published collection of articles that address topics of interest to members of a particular profession, such as law enforcement or advertising or banking. Articles tend to be brief and often report on developments and news within a field and might summarize current research being done in a particular area. Trade journals might also include editorials, letters to the editor, photo essays, and advertisements that target members of the profession. While trade journal articles might include references, the reference lists tend to be brief and don't reflect thorough reviews of the literature. Articles are usually written with the particular profession in mind, but are generally pretty accessible so that a person wishing to learn more about the profession would still be able to understand the articles. Examples of trade journals include Police Chief, Education Digest, Energy Weekly News, Aviation Week and Space Technology, Engineering News Record, Design News, and Traffic World.

Volume : Most journals and many magazines, newsletters, newspapers, and trade publications assign volume numbers to a year's worth or half a year's worth of issues. For example, a journal that publishes four times a year (quarterly) might assign each yearly collection of four issues a volume number to help identify which issues of the journal were published during a particular year. Publications that publish more frequently than monthly might also assign volume numbers, but they might change volume numbers mid year, so that there may be two volumes in any one publishing year.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Choosing What's Best >>

- Last Updated: Apr 19, 2021 9:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/articletypes

What Is Research, and Why Do People Do It?

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 December 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- James Hiebert 6 ,

- Jinfa Cai 7 ,

- Stephen Hwang 7 ,

- Anne K Morris 6 &

- Charles Hohensee 6

Part of the book series: Research in Mathematics Education ((RME))

18k Accesses

Abstractspiepr Abs1

Every day people do research as they gather information to learn about something of interest. In the scientific world, however, research means something different than simply gathering information. Scientific research is characterized by its careful planning and observing, by its relentless efforts to understand and explain, and by its commitment to learn from everyone else seriously engaged in research. We call this kind of research scientific inquiry and define it as “formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses.” By “hypotheses” we do not mean the hypotheses you encounter in statistics courses. We mean predictions about what you expect to find and rationales for why you made these predictions. Throughout this and the remaining chapters we make clear that the process of scientific inquiry applies to all kinds of research studies and data, both qualitative and quantitative.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Part I. What Is Research?

Have you ever studied something carefully because you wanted to know more about it? Maybe you wanted to know more about your grandmother’s life when she was younger so you asked her to tell you stories from her childhood, or maybe you wanted to know more about a fertilizer you were about to use in your garden so you read the ingredients on the package and looked them up online. According to the dictionary definition, you were doing research.

Recall your high school assignments asking you to “research” a topic. The assignment likely included consulting a variety of sources that discussed the topic, perhaps including some “original” sources. Often, the teacher referred to your product as a “research paper.”

Were you conducting research when you interviewed your grandmother or wrote high school papers reviewing a particular topic? Our view is that you were engaged in part of the research process, but only a small part. In this book, we reserve the word “research” for what it means in the scientific world, that is, for scientific research or, more pointedly, for scientific inquiry .

Exercise 1.1

Before you read any further, write a definition of what you think scientific inquiry is. Keep it short—Two to three sentences. You will periodically update this definition as you read this chapter and the remainder of the book.

This book is about scientific inquiry—what it is and how to do it. For starters, scientific inquiry is a process, a particular way of finding out about something that involves a number of phases. Each phase of the process constitutes one aspect of scientific inquiry. You are doing scientific inquiry as you engage in each phase, but you have not done scientific inquiry until you complete the full process. Each phase is necessary but not sufficient.

In this chapter, we set the stage by defining scientific inquiry—describing what it is and what it is not—and by discussing what it is good for and why people do it. The remaining chapters build directly on the ideas presented in this chapter.

A first thing to know is that scientific inquiry is not all or nothing. “Scientificness” is a continuum. Inquiries can be more scientific or less scientific. What makes an inquiry more scientific? You might be surprised there is no universally agreed upon answer to this question. None of the descriptors we know of are sufficient by themselves to define scientific inquiry. But all of them give you a way of thinking about some aspects of the process of scientific inquiry. Each one gives you different insights.

Exercise 1.2

As you read about each descriptor below, think about what would make an inquiry more or less scientific. If you think a descriptor is important, use it to revise your definition of scientific inquiry.

Creating an Image of Scientific Inquiry

We will present three descriptors of scientific inquiry. Each provides a different perspective and emphasizes a different aspect of scientific inquiry. We will draw on all three descriptors to compose our definition of scientific inquiry.

Descriptor 1. Experience Carefully Planned in Advance

Sir Ronald Fisher, often called the father of modern statistical design, once referred to research as “experience carefully planned in advance” (1935, p. 8). He said that humans are always learning from experience, from interacting with the world around them. Usually, this learning is haphazard rather than the result of a deliberate process carried out over an extended period of time. Research, Fisher said, was learning from experience, but experience carefully planned in advance.

This phrase can be fully appreciated by looking at each word. The fact that scientific inquiry is based on experience means that it is based on interacting with the world. These interactions could be thought of as the stuff of scientific inquiry. In addition, it is not just any experience that counts. The experience must be carefully planned . The interactions with the world must be conducted with an explicit, describable purpose, and steps must be taken to make the intended learning as likely as possible. This planning is an integral part of scientific inquiry; it is not just a preparation phase. It is one of the things that distinguishes scientific inquiry from many everyday learning experiences. Finally, these steps must be taken beforehand and the purpose of the inquiry must be articulated in advance of the experience. Clearly, scientific inquiry does not happen by accident, by just stumbling into something. Stumbling into something unexpected and interesting can happen while engaged in scientific inquiry, but learning does not depend on it and serendipity does not make the inquiry scientific.

Descriptor 2. Observing Something and Trying to Explain Why It Is the Way It Is

When we were writing this chapter and googled “scientific inquiry,” the first entry was: “Scientific inquiry refers to the diverse ways in which scientists study the natural world and propose explanations based on the evidence derived from their work.” The emphasis is on studying, or observing, and then explaining . This descriptor takes the image of scientific inquiry beyond carefully planned experience and includes explaining what was experienced.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, “explain” means “(a) to make known, (b) to make plain or understandable, (c) to give the reason or cause of, and (d) to show the logical development or relations of” (Merriam-Webster, n.d. ). We will use all these definitions. Taken together, they suggest that to explain an observation means to understand it by finding reasons (or causes) for why it is as it is. In this sense of scientific inquiry, the following are synonyms: explaining why, understanding why, and reasoning about causes and effects. Our image of scientific inquiry now includes planning, observing, and explaining why.

We need to add a final note about this descriptor. We have phrased it in a way that suggests “observing something” means you are observing something in real time—observing the way things are or the way things are changing. This is often true. But, observing could mean observing data that already have been collected, maybe by someone else making the original observations (e.g., secondary analysis of NAEP data or analysis of existing video recordings of classroom instruction). We will address secondary analyses more fully in Chap. 4 . For now, what is important is that the process requires explaining why the data look like they do.

We must note that for us, the term “data” is not limited to numerical or quantitative data such as test scores. Data can also take many nonquantitative forms, including written survey responses, interview transcripts, journal entries, video recordings of students, teachers, and classrooms, text messages, and so forth.

Exercise 1.3

What are the implications of the statement that just “observing” is not enough to count as scientific inquiry? Does this mean that a detailed description of a phenomenon is not scientific inquiry?

Find sources that define research in education that differ with our position, that say description alone, without explanation, counts as scientific research. Identify the precise points where the opinions differ. What are the best arguments for each of the positions? Which do you prefer? Why?

Descriptor 3. Updating Everyone’s Thinking in Response to More and Better Information

This descriptor focuses on a third aspect of scientific inquiry: updating and advancing the field’s understanding of phenomena that are investigated. This descriptor foregrounds a powerful characteristic of scientific inquiry: the reliability (or trustworthiness) of what is learned and the ultimate inevitability of this learning to advance human understanding of phenomena. Humans might choose not to learn from scientific inquiry, but history suggests that scientific inquiry always has the potential to advance understanding and that, eventually, humans take advantage of these new understandings.

Before exploring these bold claims a bit further, note that this descriptor uses “information” in the same way the previous two descriptors used “experience” and “observations.” These are the stuff of scientific inquiry and we will use them often, sometimes interchangeably. Frequently, we will use the term “data” to stand for all these terms.

An overriding goal of scientific inquiry is for everyone to learn from what one scientist does. Much of this book is about the methods you need to use so others have faith in what you report and can learn the same things you learned. This aspect of scientific inquiry has many implications.

One implication is that scientific inquiry is not a private practice. It is a public practice available for others to see and learn from. Notice how different this is from everyday learning. When you happen to learn something from your everyday experience, often only you gain from the experience. The fact that research is a public practice means it is also a social one. It is best conducted by interacting with others along the way: soliciting feedback at each phase, taking opportunities to present work-in-progress, and benefitting from the advice of others.

A second implication is that you, as the researcher, must be committed to sharing what you are doing and what you are learning in an open and transparent way. This allows all phases of your work to be scrutinized and critiqued. This is what gives your work credibility. The reliability or trustworthiness of your findings depends on your colleagues recognizing that you have used all appropriate methods to maximize the chances that your claims are justified by the data.

A third implication of viewing scientific inquiry as a collective enterprise is the reverse of the second—you must be committed to receiving comments from others. You must treat your colleagues as fair and honest critics even though it might sometimes feel otherwise. You must appreciate their job, which is to remain skeptical while scrutinizing what you have done in considerable detail. To provide the best help to you, they must remain skeptical about your conclusions (when, for example, the data are difficult for them to interpret) until you offer a convincing logical argument based on the information you share. A rather harsh but good-to-remember statement of the role of your friendly critics was voiced by Karl Popper, a well-known twentieth century philosopher of science: “. . . if you are interested in the problem which I tried to solve by my tentative assertion, you may help me by criticizing it as severely as you can” (Popper, 1968, p. 27).

A final implication of this third descriptor is that, as someone engaged in scientific inquiry, you have no choice but to update your thinking when the data support a different conclusion. This applies to your own data as well as to those of others. When data clearly point to a specific claim, even one that is quite different than you expected, you must reconsider your position. If the outcome is replicated multiple times, you need to adjust your thinking accordingly. Scientific inquiry does not let you pick and choose which data to believe; it mandates that everyone update their thinking when the data warrant an update.

Doing Scientific Inquiry

We define scientific inquiry in an operational sense—what does it mean to do scientific inquiry? What kind of process would satisfy all three descriptors: carefully planning an experience in advance; observing and trying to explain what you see; and, contributing to updating everyone’s thinking about an important phenomenon?

We define scientific inquiry as formulating , testing , and revising hypotheses about phenomena of interest.

Of course, we are not the only ones who define it in this way. The definition for the scientific method posted by the editors of Britannica is: “a researcher develops a hypothesis, tests it through various means, and then modifies the hypothesis on the basis of the outcome of the tests and experiments” (Britannica, n.d. ).

Notice how defining scientific inquiry this way satisfies each of the descriptors. “Carefully planning an experience in advance” is exactly what happens when formulating a hypothesis about a phenomenon of interest and thinking about how to test it. “ Observing a phenomenon” occurs when testing a hypothesis, and “ explaining ” what is found is required when revising a hypothesis based on the data. Finally, “updating everyone’s thinking” comes from comparing publicly the original with the revised hypothesis.

Doing scientific inquiry, as we have defined it, underscores the value of accumulating knowledge rather than generating random bits of knowledge. Formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses is an ongoing process, with each revised hypothesis begging for another test, whether by the same researcher or by new researchers. The editors of Britannica signaled this cyclic process by adding the following phrase to their definition of the scientific method: “The modified hypothesis is then retested, further modified, and tested again.” Scientific inquiry creates a process that encourages each study to build on the studies that have gone before. Through collective engagement in this process of building study on top of study, the scientific community works together to update its thinking.

Before exploring more fully the meaning of “formulating, testing, and revising hypotheses,” we need to acknowledge that this is not the only way researchers define research. Some researchers prefer a less formal definition, one that includes more serendipity, less planning, less explanation. You might have come across more open definitions such as “research is finding out about something.” We prefer the tighter hypothesis formulation, testing, and revision definition because we believe it provides a single, coherent map for conducting research that addresses many of the thorny problems educational researchers encounter. We believe it is the most useful orientation toward research and the most helpful to learn as a beginning researcher.

A final clarification of our definition is that it applies equally to qualitative and quantitative research. This is a familiar distinction in education that has generated much discussion. You might think our definition favors quantitative methods over qualitative methods because the language of hypothesis formulation and testing is often associated with quantitative methods. In fact, we do not favor one method over another. In Chap. 4 , we will illustrate how our definition fits research using a range of quantitative and qualitative methods.

Exercise 1.4

Look for ways to extend what the field knows in an area that has already received attention by other researchers. Specifically, you can search for a program of research carried out by more experienced researchers that has some revised hypotheses that remain untested. Identify a revised hypothesis that you might like to test.

Unpacking the Terms Formulating, Testing, and Revising Hypotheses

To get a full sense of the definition of scientific inquiry we will use throughout this book, it is helpful to spend a little time with each of the key terms.

We first want to make clear that we use the term “hypothesis” as it is defined in most dictionaries and as it used in many scientific fields rather than as it is usually defined in educational statistics courses. By “hypothesis,” we do not mean a null hypothesis that is accepted or rejected by statistical analysis. Rather, we use “hypothesis” in the sense conveyed by the following definitions: “An idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved” (Cambridge University Press, n.d. ), and “An unproved theory, proposition, or supposition, tentatively accepted to explain certain facts and to provide a basis for further investigation or argument” (Agnes & Guralnik, 2008 ).

We distinguish two parts to “hypotheses.” Hypotheses consist of predictions and rationales . Predictions are statements about what you expect to find when you inquire about something. Rationales are explanations for why you made the predictions you did, why you believe your predictions are correct. So, for us “formulating hypotheses” means making explicit predictions and developing rationales for the predictions.

“Testing hypotheses” means making observations that allow you to assess in what ways your predictions were correct and in what ways they were incorrect. In education research, it is rarely useful to think of your predictions as either right or wrong. Because of the complexity of most issues you will investigate, most predictions will be right in some ways and wrong in others.

By studying the observations you make (data you collect) to test your hypotheses, you can revise your hypotheses to better align with the observations. This means revising your predictions plus revising your rationales to justify your adjusted predictions. Even though you might not run another test, formulating revised hypotheses is an essential part of conducting a research study. Comparing your original and revised hypotheses informs everyone of what you learned by conducting your study. In addition, a revised hypothesis sets the stage for you or someone else to extend your study and accumulate more knowledge of the phenomenon.

We should note that not everyone makes a clear distinction between predictions and rationales as two aspects of hypotheses. In fact, common, non-scientific uses of the word “hypothesis” may limit it to only a prediction or only an explanation (or rationale). We choose to explicitly include both prediction and rationale in our definition of hypothesis, not because we assert this should be the universal definition, but because we want to foreground the importance of both parts acting in concert. Using “hypothesis” to represent both prediction and rationale could hide the two aspects, but we make them explicit because they provide different kinds of information. It is usually easier to make predictions than develop rationales because predictions can be guesses, hunches, or gut feelings about which you have little confidence. Developing a compelling rationale requires careful thought plus reading what other researchers have found plus talking with your colleagues. Often, while you are developing your rationale you will find good reasons to change your predictions. Developing good rationales is the engine that drives scientific inquiry. Rationales are essentially descriptions of how much you know about the phenomenon you are studying. Throughout this guide, we will elaborate on how developing good rationales drives scientific inquiry. For now, we simply note that it can sharpen your predictions and help you to interpret your data as you test your hypotheses.

Hypotheses in education research take a variety of forms or types. This is because there are a variety of phenomena that can be investigated. Investigating educational phenomena is sometimes best done using qualitative methods, sometimes using quantitative methods, and most often using mixed methods (e.g., Hay, 2016 ; Weis et al. 2019a ; Weisner, 2005 ). This means that, given our definition, hypotheses are equally applicable to qualitative and quantitative investigations.

Hypotheses take different forms when they are used to investigate different kinds of phenomena. Two very different activities in education could be labeled conducting experiments and descriptions. In an experiment, a hypothesis makes a prediction about anticipated changes, say the changes that occur when a treatment or intervention is applied. You might investigate how students’ thinking changes during a particular kind of instruction.

A second type of hypothesis, relevant for descriptive research, makes a prediction about what you will find when you investigate and describe the nature of a situation. The goal is to understand a situation as it exists rather than to understand a change from one situation to another. In this case, your prediction is what you expect to observe. Your rationale is the set of reasons for making this prediction; it is your current explanation for why the situation will look like it does.