Phonics teaching in England needs to change – our new research points to a better approach

Professor of Education, UCL

Professor of Sociology of Education, UCL

Disclosure statement

Dominic Wyse receives funding from The Helen Hamlyn Trust; the Nuffield Foundation; the Leverhulme Trust; and The Monday Charitable Trust.

Alice Bradbury receives funding from the Helen Hamlyn Trust, Economic and Social Research Council, and the Monday Charitable Trust. She is a member of the Labour Party and has worked with the More than a Score campaign.

University College London provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Arguments about the best way to teach children to read can be intense – they’ve even been described as “ the reading wars ”. In England, as in many other countries, much of the debate has been over the use of phonics, which helps children understand how sounds – “phonemes” – are represented by letters.

The government requires teachers to use a particular type of phonics teaching called “ synthetic phonics ”, and the emphasis on this technique has become overwhelming in English primary schools.

Supporters of synthetic phonics teaching have argued that teaching of phonemes and letters should be first and foremost. On the other side have been supporters of whole language instruction, who think that reading whole texts – books for example – should come first and foremost.

Our new research shows that synthetic phonics alone is not the best way to teach children to read. We found that a more effective method is to combine phonics teaching with whole texts, meaning that children learn to read by using books as well as learning phonics.

Current synthetic phonics lessons typically have an exclusive focus on phonemes, and how these are represented by letters. For example in the word “dog” each letter stands for a different phoneme: /d/ /o/ /g/. In the word “teach” there are three phonemes: /t/ /ee/ /ch/. Phonemes can be represented by one letter or sometimes by more than one letter, like the /ee/ phoneme represented by the two letters “ea” in “teach”.

The teaching of synthetic phonics is done separately from other English teaching. Children read “decodable books”: books with a limited vocabulary of words designed to emphasise use of the letters and sounds taught in phonics lessons.

Our research included a survey of more than 2,000 primary school teachers. When asked a question about their approach to reading, 66% responded: “Synthetic phonics is emphasised first and foremost in my phonics teaching.”

The Department of Education enforces the policy of teaching synthetic phonics in various ways. It vets published teaching schemes, creating a list of approved synthetic phonics schemes. Ofsted, the government office responsible for educational standards, has a strong focus on synthetic phonics teaching in their inspections of schools.

Furthermore, children in year one (aged five to six) in England take a national statutory test, the phonics screening check . This is used to emphasise phonics teaching and hold teachers to account. This test includes the requirement for children to learn to read nonsense words, called “pseudo words”. These could include, for example, “meck”, “shig”, “blem” and “sut”.

It is clear from our research that the phonics screening check is narrowing teaching. For example, 237 teachers in our survey said that they were giving extra phonics lessons to help children pass the test. The word “pressure” appeared 97 times in teachers’ comments about the phonics screening check. One teacher felt that they had to “live and breathe phonics”.

Existing evidence

Our research also reviewed the best existing evidence on phonics teaching and reading. Previous research – a systematic review, which analyses the findings of a number of research papers – not only questioned an emphasis on synthetic phonics but also on other systematic phonics teaching. It found that there is no evidence that synthetic phonics teaching is better than other methods of teaching phonics and reading.

Other main methods of teaching reading include the “whole language” approach. In this approach, teaching reading with whole texts is the priority. Encouraging children’s motivation for reading is another main aim of whole language teaching. In the whole-language approach phonics is not taught systematically.

Another main method of teaching reading is “balanced instruction”. With this approach the importance of comprehending the meaning of written language is carefully balanced with the acquisition of a range of skills and knowledge. Balanced instruction combines systematic teaching of whole texts and other linguistic aspects such as sentences and words.

Another systematic review found that integrating phonics teaching with comprehension teaching resulted in the best impact on children’s reading.

As part of our research we carried out a new analysis of all 55 research papers that were part of this systematic review. In summary, it was clear that in effective teaching approaches phonics teaching was connected with whole texts in every lesson.

One study, carried out in Canada, was particularly compelling because the tests of children’s reading comprehension showed that the approach had been effective four years after the intervention had ended. The effective approach was driven by helping children to make sense of reading using whole texts.

A different approach

We found that England’s emphasis on synthetic phonics is different compared to high performing English language countries in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests. None of these other countries mandate synthetic phonics.

Canada has consistently performed the best of English language dominant nations in the PISA tests. Canada’s approach at national and state level is very different from England’s because it emphasises whole texts, and phonics is not emphasised as much.

The approach to teaching reading in England means that children in England are unlikely to be learning to read as effectively as they should be. Teachers, children, and their parents need a more balanced approach to the teaching of reading.

- Primary school

- Phonics screening test

Research Fellow – Magnetic Refrigeration

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Social Media Producer

Dean (Head of School), Indigenous Knowledges

Advertisement

Reconsidering the Evidence That Systematic Phonics Is More Effective Than Alternative Methods of Reading Instruction

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 January 2020

- Volume 32 , pages 681–705, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jeffrey S. Bowers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9558-5010 1

116k Accesses

44 Citations

328 Altmetric

11 Mentions

Explore all metrics

There is a widespread consensus in the research community that reading instruction in English should first focus on teaching letter (grapheme) to sound (phoneme) correspondences rather than adopt meaning-based reading approaches such as whole language instruction. That is, initial reading instruction should emphasize systematic phonics. In this systematic review, I show that this conclusion is not justified based on (a) an exhaustive review of 12 meta-analyses that have assessed the efficacy of systematic phonics and (b) summarizing the outcomes of teaching systematic phonics in all state schools in England since 2007. The failure to obtain evidence in support of systematic phonics should not be taken as an argument in support of whole language and related methods, but rather, it highlights the need to explore alternative approaches to reading instruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

The simple view of reading and its broad types of reading difficulties

The impact of multisensory instruction on learning letter names and sounds, word reading, and spelling.

Does Spelling Still Matter—and If So, How Should It Be Taught? Perspectives from Contemporary and Historical Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is a widespread consensus in the research community that early reading instruction in English should emphasize systematic phonics. That is, initial reading instruction should explicitly and systematically teach letter (grapheme) to sound (phoneme) correspondences. This contrasts with the main alternative method called whole language in which children are encouraged to focus on the meanings of words embedded in meaningful text, and where letter-sound correspondences are only taught incidentally when needed (Moats 2000 ). Within the psychological research community, the “Reading Wars” (Pearson 2004 ) that pitted whole language and phonics is largely settled—systematic phonics is claimed to be more effective. Indeed, it is widely claimed that systematic phonics is an essential part of initial reading instruction.

The evidence for this conclusion comes from various sources, including government panels that assessed the effectiveness of different approaches to reading instruction in the USA (National Reading Panel 2000 ), the UK (the Rose Review; Rose 2006 ), and Australia (Rowe 2005 ), 12 meta-analyses of experimental research, as well as nonexperimental studies that have tracked progress of students in England since the requirement to teach systematic phonics in state schools since 2007. The results are claimed to be clear-cut. For example, in his review for the English government, Sir Jim Rose writes

“Having considered a wide range of evidence, the review has concluded that the case for systematic phonic work is overwhelming …” (Rose 2006 , p. 20).

Similarly, in a recent influential review of reading acquisition that calls for an end to the reading wars (in support of systematic phonics), Castles, Nation, and Rastle ( 2018 ) write

It will be clear from our review so far that there is strong scientific consensus on the effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction during the initial periods of reading instruction.

Countless quotes to this effect could be provided.

Importantly, this strong consensus has resulted in important policy changes in England and USA. Based on Rose ( 2006 ), systematic phonics became a legal requirement in state-funded primary schools in England since 2007, and to ensure compliance, all children (ages 5–6) complete a phonics screening check (PSC) since 2012 that measures how well they can sound out a set of regular words and meaningless pseudowords. Similarly, based on the recommendations of the National Reading Panel (NRP 2000 ), systematic phonics instruction was included in the Common Core State Standards Initiative in the USA (http:// www.corestandards.org/ ). The Thomas Fordham Foundation concluded that the NRP document is the third most influential policy work in US education history (Swanson and Barlage 2006 ).

Nevertheless, despite this strong consensus, I will show that there is little or no evidence that systematic phonics is better than the main alternative methods used in schools, including whole language and balanced literacy. This should not be taken as an argument in support of these alternative methods, but rather, it should be taken as evidence that the current methods used in schools are far from idea. Once this is understood, my hope is that researchers and politicians will be more motivated to consider alternative methods.

Structure of Paper

The remainder of the paper is organized in three main sections. First, I review the most common methods of reading instruction. There are some points of overlap between the alternative methods, but a commitment to systematic phonics entails some specific claims about what constitutes effective early reading instruction. Second, I explore the experimental evidence taken to support of systematic phonics by providing a detailed and exhaustive review of all meta-analyses that have assessed the efficacy of systematic phonics. The conclusion from this review is simple: There is little or no evidence that systematic phonics is better than the most common alternative methods used in schools. The problem is that (a) the findings are often mischaracterized by the authors of the reports, and these mischaracterizations are passed on and exaggerated by many others citing the work and (b) that the designs of the meta-analyses often do not even test the hypothesis that systematic phonics is more effective than whole language and other common methods. Third, I review the outcomes of a large naturalist experiment, namely, the impact of requiring systematic phonics in all English state schools since 2007. Again, the findings provide little or no evidence that systematic phonics has improved reading. Together, this should motivate researchers to consider alternative teaching methods.

What Is Systematic Phonics and What Are the Common Alternatives?

All forms of reading instruction are motivated by one or more of the following facts: (1) Written words have pronunciations; (2) written words have a meaning; (3) words are composed of parts, including letters and morphemes; (4) written words tend to occur in meaningful text; and (5) the ultimate goal of reading is to extract meaning from text. Different forms of instruction emphasize some of these points and downplay or ignore others, but there is nevertheless some overlap between different methods, and this complicates the task of comparing methods. For example, whole language instruction focuses on understanding words in the context of text, but it also includes some degree of phonics (e.g., Moats 2000 ; NPR, 2000), and this has implications for how the meta-analyses described below can be interpreted. A further complication is that it is widely claimed that systematic phonics should be embedded in a broader literacy curriculum. For instance, the NRP (2000) emphasizes that systematic phonics should be integrated with other forms of instruction, including phonemic awareness, fluency, and comprehension strategies, and again, this makes it more difficult to make claims regarding systematic phonics per se. Because of these complexities, it is important to review systematic phonics and its relation to alternative methods in some detail so that the claims regarding the importance of systematic phonics can be evaluated.

As noted above, systematic phonics explicitly teaches children grapheme-phoneme correspondences prior to emphasizing the meanings of written words in text (as in whole language or balanced literacy instruction) or the meaning of written words in isolation (as in morphological instruction). That is, systematic phonics is committed to the “phonology first” hypothesis (Bowers and Bowers 2018a ). It is called systematic because it teaches grapheme-phoneme correspondences in an organized sequence as opposed to incidentally or on a “when-needed” basis. Several versions of systematic phonics exist (most notably synthetic and analytic), but they all adopt the phonology first hypothesis.

The main alternative to phonics is whole language that primarily focuses on the meaning of words presented in text. Teachers are expected to provide a literacy-rich environment for their students and to combine speaking, listening, reading, and writing. Students are taught to use critical thinking strategies and to use context to guess words that they do not recognize. Importantly, whole language typically includes some phonics, but the phonics instruction is not systematically taught (e.g., children are taught to sound out words when they cannot guess the word from context). For example, the authors of the NRP (2000) report write

Whole language teachers typically provide some instruction in phonics, usually as part of invented spelling activities or through the use of graphophonemic prompts during reading (Routman, 1996 ). However, their approach is to teach it unsystematically and incidentally in context as the need arises. The whole language approach regards letter-sound correspondences, referred to as graphophonemics, as just one of three cueing systems (the others being semantic/meaning cues and syntactic/language cues) that are used to read and write text. Whole language teachers believe that phonics instruction should be integrated into meaningful reading, writing, listening, and speaking activities and taught incidentally when they perceive it is needed. As children attempt to use written language for communication, they will discover naturally that they need to know about letter-sound relationships and how letters function in reading and writing. When this need becomes evident, teachers are expected to respond by providing the instruction.

The fact that whole language (and related methods) includes nonsystematic phonics turns out to be critical to the evaluations of the meta-analyses that follow.

Another approach to reading instruction called balanced literacy is designed to combine whole language with its focus on reading for meaning with systematic phonics. However, it is often claimed that balanced literacy is effectively just another name for whole language given that the phonics in balanced literacy is not taught first, not given enough emphasis, nor is it taught systematically (e.g., Moats 2000 ).

Another teaching method is called whole word or sight word training in which children are taught to identify individual words (out of context) without breaking down the words into phonemes or other sublexical parts. For instance, in order to improve word naming, children might be given a list of written words and then one of the words is read aloud. The child’s task is to select the corresponding written word, with the goal of improving their ability to read the word later (McArthur et al. 2013 , 2015 ). Similarly, the look-say-cover-write method is commonly used in whole word instruction to teach children the spelling of words. In this method, a child looks at a word, reads it aloud, covers the word up, and then attempts to spell the word (for review, see Browder and Xin 1998 ). Although whole word and whole language methods are different in many ways (most notably in whether some or no phonics is included), the two methods are often treated equivalently in the meta-analyses described below, and this has important implications for how the meta-analyses can be interpreted.

Morphological instruction, like whole language or balanced instruction, emphasizes the importance of attaching meaning to words, but it also teaches children to break down words into their meaningful parts (prefixes, bases, and suffixes). For review of this method, see Carlisle ( 2000 ). Related to this, structured word inquiry (SWI) teaches children the interrelation between all the sublexical components of written words (phonology, morphology, and etymology) in order to make sense of word spellings with the aim of improving all aspects of literacy, including reading, spelling, vocabulary, and comprehension (Bowers and Kirby 2010 ). Like systematic phonics, this approach explicitly teaches children the mappings between graphemes and phonemes, but children are taught how these mappings are organized within morphemes from the start (Bowers and Bowers 2017 , 2018a , 2018b , 2018c ).

The overlap between methods and the claim that systematic phonics should be embedded with other methods makes the task of assessing the efficacy of systematic phonics per se more difficult. Nevertheless, proponents of systematic phonics are committed to two specific claims about what does and does not constitute good instruction, meaning that this approach can be evaluated.

First, it is claimed that systematic phonics should be taught before meaning-based approaches that focus on the meaning of written words in the context of sentences or focus on the meaningful sublexical structure of words (e.g., morphological instruction). For example, Castles, Rastle, and Nation ( 2018 ) write

…morphological instruction… may detract from vital time spent learning spelling-sound relationships. Instead, we would predict that the benefits of explicit morphological instruction are more likely to be observed somewhat later in reading development…

The claim that grapheme-phoneme correspondences should be taught prior to any morphological instruction is widespread (e.g., Adams 1994 ; Ehri and McCormick 1998 ; Henry 1989 ; Larkin and Snowling 2008 ; Taylor et al. 2017 ).

Second, it is claimed that grapheme-phoneme correspondences should be taught systematically (as the name suggests). That is, there should be a program of instruction in which all the relevant grapheme-phoneme mappings are taught explicitly in an ordered manner. This is not possible when teaching the grapheme-phoneme correspondences of words embedded in meaningful texts as typical with whole language (given that order of grapheme-phonemes in meaningful texts is too variable). The main justification for systematic phonics is empirical, namely, the widespread claim that studies support systematic phonics over alternative methods, as summarized in multiple meta-analyses detailed below.

To summarize, there are a number of different forms of reading instruction, some of which emphasize letter-sound mappings before other properties of words (e.g., systematic phonics), others that emphasize meaning from the start (e.g., whole language), and others that claim that the phonology and meaning of word spellings should be the focus of instruction from the beginning (structured word inquiry). There is no disagreement that reading instruction needs to ultimately incorporate both meaning and phonology, but the widespread consensus in the research community is that instruction needs to systematically teach children the grapheme-phoneme correspondences before meaning-based strategies are emphasized. Accordingly, almost all researchers today claim that systematic phonics is better than whole language, balanced literacy, and all forms of instruction that consider morphology from the beginning. The evidence for this claim is considered below and found wanting.

A Critical Examination of the Meta-Analyses Taken to Support Systematic Phonics

A total of 12 meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy of systematic phonics for individuals of different ages and abilities. In most cases (although not all), the meta-analyses are taken to support the conclusion that systematic phonics is an essential component of initial reading instruction and more effective than common alternatives such as whole language. As detailed below, this conclusion is not justified by any of the meta-analyses. The results have been mischaracterized by the authors themselves (summarizing the results in ways that mislead the reader), and in most cases, the design of the meta-analyses was not even designed to test the conclusions that were drawn by the authors.

National Reading Panel ( 2000 ) and Ehri et al. ( 2001 ) Meta-Analyses

The seminal report most often taken to support the efficacy of systematic phonics compared with alternative methods was a government document produced by the National Reading Panel (NRP, 2000), with the findings later published in peer review form (Ehri et al. 2001 ). The authors carried out the first meta-analysis evaluating the effects of systematic phonics compared with forms of instruction that include unsystematic or no phonics across a range of reading measures, including word naming, nonword naming, and text comprehension tasks. The meta-analysis included 66 treatment-control comparisons taken from 38 experiments, and the main findings can be seen in Table 1 . Based on these findings, Ehri et al. ( 2001 ) concluded in the abstract:

“Systematic phonics instruction helped children learn to read better than all forms of control group instruction, including whole language. In sum, systematic phonics instruction proved effective and should be implemented as part of literacy programs to teach beginning reading as well as to prevent and remediate reading difficulties.”

The NRP report has been cited over 24,000 times and continues to be used in support of systematic phonics, with over 1000 citations in 2019. In addition, the Ehri et al. ( 2001 ) article has been cited over 1000 times. However, a careful look at the results undermines these strong conclusions.

The most important limitation is that systematic phonics did not help children labeled “low achieving” poor readers ( d = 0.15, not significant). These were children above first grade who were below average readers and whose cognitive level was below average or not assessed. By contrast, children labeled “reading disabled” who were below grade level in reading but at least average cognitively and were above first grade in most cases did benefit ( d = 0.32). Note, by definition, half the population of children above grade 1 will have an IQ below average, and it is likely that more than 50% of struggling readers above grade 1 will fall into this category given the comorbidity of developmental disorders (Gooch et al. 2014 ). Of course, additional research may show that systematic phonics does benefit low achieving poor readers (the NRP only included eight comparison groups in this condition), but there is no evidence for this from the NRP meta-analysis.

Second, based on the finding that effect sizes were greater when phonics instruction began by first grade ( d = 0.55) rather than after first grade ( d = 0.27), the authors of the NRP wrote in the executive summary “Phonics instruction taught early proved much more effective than phonics instruction introduced after first grade” (pp. 2–93). But in the body of the text, it becomes clear that findings do not support this strong conclusion. One problem is that the majority of older students (78%) in the various studies included in the NRP analysis were either low achieving readers or students with reading disability, and as noted above, systematic phonics was less effective with both these populations (especially the former group). With regard to the normally developing older readers, the NRP meta-analysis only included seven comparison groups, and four of them used the Orton-Gillingham method that was developed for younger students. As noted by Ehri et al. ( 2001 ):

“The conclusion that phonics instruction is less effective when introduced beyond first grade may be premature… Other types of phonics programs might prove more effective for older readers without any reading problems.” (p. 428)

This is straightforwardly at odds with the above executive summary and explains why so many authors cite the NRP as providing evidence that early phonics instruction is important.

Third, although the authors of the NRP emphasized that the systematic phonics had long-term impact, the effect size declined from d = 0.41 when children were tested immediately following the intervention to d = 0.27 following a 4 to 12-month delay. However, the authors did not assess whether the long-term benefits extended to spelling, reading texts, or reading comprehension. Given that the short-term effects on spelling, reading texts, or reading comprehension was much reduced compared with the overall short-term effect (Table 1 ), there is no reason to assume these effects persisted.

Fourth, the evidence that that systematic phonics is more effective than whole language is weaker still. This claim is not based on the overall effect size of d = 0.41, but rather, on a subanalysis that specifically compared systematic phonics to whole language. This analysis was based on 12 rather than 38 studies, and not one of these 12 studies used a randomized control trial (RCT) design. This analysis showed a reduced overall effect of d = 0.31 (still significant), with the largest effect obtained for decoding (mean of the reported effect sizes was d = 0.55) and smallest effect on comprehension (mean of the reported effect sizes was d = 0.19), with only two studies assessing performance following a delay. And although the NRP is often taken to support the efficacy of synthetic systematic phonics (the version of phonics legally mandated in the UK), the NRP meta-analysis only included four studies relevant for this comparison (of 12 studies that compared systematic phonics with whole language, only four assessed synthetic phonics). The effect sizes in order of magnitude were d = 0.91 and d = 0.12 in two studies that assessed grade 1 and 2 students, respectively (Foorman et al. 1998 ); d = 0.07 in a study that asses grade 1 students (Traweek & Berninger, 1997 ); and d = − 0.47 in a study carried out on grade 2 students (Wilson & Norman, 1998 ).

In sum, rather than the strong conclusions emphasized the executive summary of the NRP ( 2000 ) and the abstract of Ehri et al. ( 2001 ), the appropriate conclusion from this meta-analysis should be something like this:

Systematic phonics provides a small short-term benefit to spelling, reading text, and comprehension, with no evidence that these effects persist following a delay of 4–12 months (the effects were not reported nor assessed). It is unclear whether there is an advantage of introducing phonics early, and there are no short- or long-term benefit for majority of struggling readers above grade 1 (children with below average intelligence). Systematic phonics did provide a moderate short-term benefit to regular word and pseudoword naming, with overall benefits significant but reduced by a third following 4–12 months.

And even these weak conclusions in support of systematic phonics are not justified given subsequent work by Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) and Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) who reanalyzed the studies (or a subset of studies) included in the NRP, as described next.

Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 )

Camilli et al. ( 2003 ) identified a number of flaws in the NRP meta-analysis, but here I emphasize one, namely, it was not designed to assess whether there is any benefit in teaching phonics systematically. Similar design choices were made by all subsequent meta-analyses taken to support systematic phonics, and this has led to unwarranted conclusions from these meta-analyses as I detail below.

As noted above, the headline figure from the NRP analysis is that systematic phonics showed an overall immediate effect size of d = 0.41. What needs to be emphasized is that this figure is the product of comparing systematic phonics with a heterogeneous control condition that included (1) intervention studies that used unsystematic phonics and (2) intervention studies that used no phonics. As elementary point of logic, if you compare systematic phonics to a mixture of different methods, some of which use unsystematic phonics and other that use no phonics, then it is not possible to conclude that systematic phonics is more effective than unsystematic phonics. In order to assess whether the “systematic” in systematic phonics is important, it is necessary to compare systematic phonics to studies that included unsystematic phonics, something that the NRP ( 2000 ) did not do.

The reason why this is important is that unsystematic phonics is standard in common alternatives to systematic phonics. Indeed, in addition to the widespread use of unsystematic phonics in the USA prior to the NPR ( 2000 ) report (as shown above in a quote from NRP), Her Majesty’s Inspectorate ( 1990 ) reported that unsystematic phonics was also common in the UK prior to the legal requirement to teach systematic synthetic phonics in England in 2007, writing

“...phonic skills were taught almost universally and usually to beneficial effect” (p. 2) and that “Successful teachers of reading and the majority of schools used a mix of methods each reinforcing the other as the children’s reading developed” (p. 15).

Accordingly, the important question is whether systematic phonics is more effective than the unsystematic phonics that is used in alternative teaching methods.

In order to assess the importance of teaching phonics systematically, Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) coded the studies included in the NRP as having no phonics, unsystematic phonics, or systematic phonics. In addition, the authors also noted that some moderator variables were ignored by the NRP analysis that may have contributed to the outcomes. Accordingly, the authors also coded whether or not the intervention studies included language-based reading activities such as shared writing, shared reading, or guided reading, whether treatments were carried out in the regular class or involved tutoring outside the class, and whether basal readers were used (if known). Both the experimental and control groups were coded with regard to these moderator variables. It should also be noted that the Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) analyses were carried out on a slightly modified dataset given problems with some of the studies and conditions included in the NRP report. For example, the authors dropped one study (Vickery et al., 1987 ) that did not include a control condition (an exclusion condition according to the NRP) and included three studies that were incorrectly excluded (the studies did fulfill the NRP inclusion criterion), resulting in a total of 40 rather than 38 studies. The interested reader can find out more details regarding the slightly modified dataset in Camilli et al. ( 2003 ), but in any case, the different datasets produce the same outcome as discussed below.

The Camilli et al. ( 2003 ) analysis showed that effect size of systematic phonics compared with nonsystematic phonics was significant, but roughly half the size of the effect of systematic phonics reported in the NRP report ( d = 0.24 vs. d = 0.41). Interesting, the analysis also found significant and numerically larger effects of systematic language activities ( d = 0.29) and tutoring ( d = 0.40). The subsequent analysis by Camilli et al. ( 2006 ) was carried out on the same dataset but used a new method of analysis (a multilevel modeling approach) and included three rather than two levels of language-based reading activities as a moderator variable (none vs., some, vs. high levels of language-based activities). This analysis revealed an even smaller effect of systematic phonics ( d = 0.12) that was no longer significant. Camilli et al. ( 2006 ) took these findings to challenge the strong conclusion drawn by the authors of the NRP.

These analyses were subsequently supported by Stuebing et al. ( 2008 ) who reanalyzed the Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) dataset and showed that the different outcomes were not the consequence of the slightly different studies included in the Camilli and the NPR meta-analyses. However, Stuebing et al. ( 2008 ) drew a different conclusion, writing

The NRP question is analogous to asking about the value of receiving the intervention versus not receiving the intervention. The Camilli et al. ( 2003 ) report is analogous to asking what is the value of receiving a strong form of the intervention compared to a receiving weaker forms of the intervention and relative to factors that moderate the outcomes. From our view, both questions are reasonable for intervention studies.

But the two questions are not equally relevant to teaching policy. The relevant question is whether systematic phonics is better than preexisting practices. Given that unsystematic phonics was standard practice, and given the Camilli et al. ( 2006 ) analysis failed to show an advantage of systematic over unsystematic phonics, Camilli et al. analysis challenges the main conclusion that schools should introduce systematic phonics.

To avoid any conclusion, it is important to highlight that the Camilli et al. ( 2006 ) reanalysis of the NRP dataset does not suggest that grapheme-phoneme knowledge is unimportant. Indeed, their reanalysis suggests that systematic phonics is significantly better than a nonphonics control condition. Rather, their key finding is that systematic phonics was no better than nonsystematic phonics as commonly used in schools.

Torgerson et al. ( 2006 )

The Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) meta-analysis was primarily motivated by another key limitation of the NRP report not touched on thus far, namely, the fact that the NRP included studies that employed both randomized and nonrandomized designs. Given the methodological problems with nonrandomized studies, Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) carried out a new meta-analysis that was limited to randomized control trials (RCTs). But it is worth noting two additional limitations of the NRP report that motivated this analysis.

First, the authors were concerned that bias played a role in 13 RCT studies included in the original NRP report given that the NRP report only considered published studies (studies that obtained null effects may have been more difficult to publish). Indeed, the authors carried out a funnel plot analysis on these 13 studies and concluded that the results provided: “…prima facie evidence for publication bias, since it seems highly unlikely that no RCT has ever returned a null or negative result in this field.” Accordingly, Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) searched for unpublished studies that met their inclusion criteria. They found one additional study that reported an effect size of − 0.17 that they included in their analyses. Note that this bias would have inflated the small effects reported in the NRP ( 2000 ) and the Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) meta-analyses. Second, Torgerson et al. removed two studies that should have been excluded from the NRP analyses (Gittelman and Feingold 1983 , because it did not include a phonics instruction intervention group; Manzticopoulos et al., 1992 , because the children in the control condition did not receive a reading intervention, and the attrition rate of the studies was extreme, with 437 children randomized and only 168 children tested). This led to 12 studies that compared systematic phonics to a control condition that included unsystematic phonics or no phonics instruction control. The key positive result was with regard to word reading accuracy with an effect size estimated to between 0.27 and 0.38 (depending on assumptions built into the analyses). By contrast, no significant effects were obtained for comprehension ( d estimates ranging between 0.24 and 0.35), or spelling ( d = 0.09).

There are, however, reasons to question the significant word reading accuracy results. This result was largely due to one outlier study (Umbach et al. 1989 ) that obtained a massive effect on word reading accuracy ( d = 2.69). Footnote 1 In this study, the control group was taught by two regular teachers with help from two university supervised practicum students, whereas the experimental group was taught by four Masters’ degree students who were participating in a practicum at a nearby university. Accordingly, there is a clear confound in the design of the study. Torgerson et al. themselves reanalyzed the results when this study was excluded and found that the word reading accuracy result was reduced ( d estimates between 0.20 and 0.21) with the effect just reaching significance one analysis ( p = 0.03) and nonsignificant on another ( p = 0.09). For summary of findings, see Table 1 . And even these findings likely overestimate the efficacy of systematic phonics given the evidence that bias may have inflated the estimate of effect sizes in this study. As Torgerson et al. wrote

In addition, the strong possibility of publication bias affecting the results cannot be excluded. This is based on results of the funnel plot... It seems clear that a cautious approach is justified (p. 48).

The conclusions one can draw are further weakened by the quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis, with the authors writing

…none of the 14 trials reported method of random allocation or sample size justification, and only two reported blinded assessment of outcome… all were lacking in their reporting of some issues that are important for methodological rigor. Quality of reporting is a good but not perfect indicator of design quality. Therefore due to the limitations in the quality of reporting the overall quality of the trials was judged to be “variable” but limited.

Nevertheless, despite all the above issues, the authors concluded

Systematic phonics instruction within a broad literacy curriculum appears to have a greater effect on childrens progress in reading than whole language or whole word approaches. The effect size is moderate but still important.

This quote not only greatly exaggerates the strength of the findings (which helps explain why the meta-analysis has been cited over 250 times in support of systematic phonics), but it again reveals a misunderstanding regarding the conclusions one can draw from the design of the meta-analysis. The study continued to use the design of the NRP ( 2000 ) meta-analysis that compared systematic phonics to a control condition that combined (1) nonsystematic phonics and (2) no phonics. Accordingly, it is not possible to conclude that systematic phonics is more effective than whole word instruction that uses unsystematic phonics. That would require a direct comparison between conditions that was not carried out.

To summarize thus far, a careful review of the NPR ( 2000 ) findings show that that the benefits of systematic phonics for reading text, spelling, and comprehension are weak and short-lived, with reduced or no benefits for struggling readers beyond grade 1. The subsequent Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 ) and Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) reanalyses further weakens these conclusions. Indeed, Camilli et al. ( 2006 ) found no overall benefit of systematic phonics over nonsystematic phonics, and Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) did not find any benefit of systematic phonics in the subset of RCT studies included in the NRP for word reading accuracy, comprehension, or spelling (when one outlier study was excluded). The null effects in the Torgerson et al. ( 2006 ) meta-analysis were obtained despite evidence for publication bias and flawed design that combined unsystematic and no phonics studies into a control condition (with both of these factors serving to inflate the benefits of systematic phonics).

McArthur et al. ( 2012 )

This meta-analysis was designed to assess the efficacy of systematic phonics with children, adolescents, and adults with reading difficulties. The authors included studies that use randomization, quasi-randomization, or minimization (that minimizes differences between groups for one or more factors) to assign participants to either a systematic phonics intervention group or a control group that received no training or alternative training that did not involve any reading activity (e.g., math training). That is, the control group received no phonics at all. Based on these criteria, the authors identified 11 studies that assessed a range of reading outcomes, although some outcome measures were only assessed in a few studies. Critically, the authors found a significant effect of word reading accuracy ( d = 0.47, p = 0.03) and nonword reading accuracy ( d = 0.76, p < 0.01), whereas no significant effects were obtained in word reading fluency ( d = − 0.51; expected direction), reading comprehension ( d = 0.14), spelling ( d = 0.36), and nonword reading fluency ( d = 0.38, the unexpected direction). Based on the results, the authors concluded that systematic phonics improved performance, but they were also cautious in their conclusion, writing

…there is a widely held belief that phonics training is the best way to treat poor reading. Given this belief, we were surprised to find that of 6632 records, we found only 11 studies that examined the effect of a relatively pure phonics training programme in poor readers. While the outcomes of these studies generally support the belief in phonics, many more randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are needed before we can be confident about the strength and extent of the effects of phonics training per se in English-speaking poor word readers.

But there are reasons to question even these modest conclusions. One notable feature of the word reading accuracy results is that they were largely driven by two studies (Levy and Lysynchuk 1997 ; Levy et al. 1999 ) with effect sizes of d = 1.12 and d = 1.80, respectively. The remaining eight studies that assessed reading word accuracy reported a mean effect size of 0.16 (see Appendix 1.1, page 63). This is problematic given that the children in the Levy studies were trained on one set of words, and then, reading accuracy was assessed on another set of words that shared either onsets or rhymes with the trained items (e.g., a child might have been trained on the word beak and later be tested on the word peak ; the stimuli were not presented in either paper). Accordingly, the large benefits observed in the phonics conditions compared with a nontrained control group only shows that training generalized to highly similar words rather than word reading accuracy more generally (the claim of the meta-analysis). In addition, both Levy et al. studies taught systematic phonics using one-on-one tutoring. Although McArthur et al. reported that group size did not have an overall impact on performance, one-on-one training studies with a tutor showed an average effect size of d = 0.93 (over three studies). Accordingly, the large effect size for word reading accuracy may be more the product of one-on-one training with a tutor rather than any benefits of phonics per se, consistent with the findings of Camilli et al. ( 2003 ). In the absence of the two studies by levy and colleagues, there is no evidence from the McArthur et al. ( 2012 ) meta-analysis that systematic phonics condition improved word reading accuracy, word reading fluency, reading comprehension, spelling, or nonword reading fluency, leaving only a benefit for nonword reading accuracy.

But even putting these concerns aside, the most important point to note is that this meta-analysis compared systematic phonics to no extra training at all, or to training on nonreading tasks. Accordingly, it is not appropriate to attribute any benefits to systematic phonics. Any form of extra instruction may have mediated the (extremely limited) gains. So once again, this analysis should not be used to make any claims that systematic phonics is better than standard alternative methods, such as whole language that do include unsystematic phonics.

Galuschka et al. ( 2014 )

Galuschka et al. carried out a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies that focused on children and adolescents with reading difficulties. The authors identified 22 trials with a total of 49 comparisons of experimental and control groups that tested a wide range of interventions, including five trials evaluating reading fluency trainings, three phonemic awareness instructions, three reading comprehension trainings, 29 phonics instructions, three auditory trainings, two medical treatments, and four interventions with colored overlays or lenses. Outcomes were divided into reading and spelling measures.

The authors noted that only phonics produced a significant effect, with an overall effect size of g ′ = 0.32, and concluded

This finding is consistent with those reported in previous meta-analyses... At the current state of knowledge, it is adequate to conclude that the systematic instruction of letter-sound correspondences and decoding strategies, and the application of these skills in reading and writing activities, is the most effective method for improving literacy skills of children and adolescents with reading disabilities

However, there are serious problems with this conclusion. Most notably, the overall effect sizes observed for phonics ( g ′ = 0.32) was similar to the outcomes with phonemic awareness instruction ( g ′ = 0.28), reading fluency training ( g ′ = 0.30), auditory training ( g ′ = 0.39), and color overlays ( g ′ = 0.32), with only reading comprehension training ( g ′ = 0.18) and medical treatment ( g ′ = 0.12) producing numerically reduced effects. The reason significant results were only obtained for phonics is that there were many more phonics interventions. In order to support their conclusion that phonics is more effective, the authors need to show an interaction between the phonics condition and the alternative methods. They did not report this analysis, and given the similar effect sizes across conditions (with small sample sizes), this analysis would not be significant. Of course, future research might support the author conclusion, but this meta-analysis does not support it.

To further compromise the authors’ conclusion, Galuschka et al. reported evidence that the published phonics studies were biased using a funnel plot analysis. Using a method called Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill they measured the extent of publication bias and estimated an unbiased effect size for systematic phonics to be greatly reduced, although still significant, g ′ = 0.198. And yet again, the design of the meta-analysis did not assess whether systematic phonics was more effective than unsystematic phonics (let alone show that systematic phonics is more effective than the alternative methods they did investigate). Nevertheless, the meta-analysis is frequently cited as evidence in support of systematic phonics over whole language (e.g., Lim and Oei 2015 ; Treiman 2018 ; Van der Kleij et al. 2017 ).

Suggate ( 2010 , 2016 )

Suggate ( 2010 ) carried out a meta-analysis to investigate the relative advantages of systematic phonics, phonological awareness, and comprehension-based interventions with children at-risk of reading problems. The central question was whether different forms of interventions were more effective with different age groups of children who varied from preschool to grade 7.

The meta-analysis included peer-reviewed randomized and quasi-experimental studies, with control groups receiving either typical instruction or an alternative “in-house” school reading intervention. They identified 85 studies with 116 interventions: 13 were classified as phonological awareness, 36 as phonics, 37 as comprehension based, and 30 as mixed. Twelve studies were conducted with participants who did not speak English. A range of dependent measures were assessed, from prereading (e.g., letter knowledge, phonemic/sound awareness), reading, and comprehension measures.

Averaging over age, similar overall effects were for phonological awareness ( d = 0.47), phonics ( d = 0.50), meaning based ( d = 0.58), and mixed ( d = 0.43). The critical novel finding, however, was that there was a significant interaction between method of instruction and age of child, such that phonics was most useful in kindergarten for reading measures, but alternative interventions were more effective for older children. As Suggate ( 2010 ) writes

If reading skills per se are targeted, then there is a clear advantage for phonics interventions early and—taking into account sample sizes and available data—comprehension or mixed interventions later.

However, this is not a safe conclusion. First, the difference in effect size in phonics compared with alternative methods was approximately d = 0.10 in kindergarten and 0.05 in grade 1 (as estimated from Figure 1 in Suggate 2010 ). This is not a strong basis for arguing the importance of early systematic phonics. It is also important to note that 10% of the studies included in the meta-analysis were carried out on non-English children. Although the overall difference between non-English ( d = 0.61) and English ( d = 0.48) studies was reported as nonsignificant, the difference approached significance ( p = 0.06). Indeed, the phonics intervention that reported the very largest effect size ( d = 1.37) was carried out in Hebrew speakers (Aram & Biron, 2004 ), and this study contributed to the estimate of the phonics effect size in prekindergarten. Accordingly, the small advantage of phonics (the main novel finding in this report) is inflatedwhen applied to English. And once again, the treatments were compared with a control condition that combined a range of teaching conditions, and accordingly, it is again unclear whether there was a difference between systematic vs. unsystematic phonics during early instruction.

But the most critical limitation is that Suggate’s ( 2010 ) conclusion regarding the benefits of early phonics instruction is contradicted in a subsequent Suggate ( 2016 ) meta-analysis. This meta-analysis included 71 experimental and quasi-experimental reading interventions that assessed the short- and long-term impacts of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and comprehension interventions on prereading, reading, reading comprehension, and spelling measures. The analysis revealed an overall short-term effect ( d = 0.37) that decreased in a follow-up test ( d = 0.22; with mean delay of 11.17 months) with phonics producing the most short-lived benefits. Specifically, the long-term effects were phonics, d = 0.07; fluency, d = 0.28; comprehension d = 46; and phonemic awareness, d = 0.36.

As with the other meta-analyses, there are additional issues that should be raised. For example, a funnel plot observed evidence for publication bias, especially in the long-term condition, and once again, the study does not compare systematic to unsystematic phonics. It is striking that long-term benefits of systematic phonics are so small despite these factors that should be expected to inflate effect sizes.

Other Meta-Analyses and a Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses

There are a number of additional relevant meta-analyses and reviews of meta-analyses that should be mentioned briefly as well.

Hammill and Swanson ( 2006 )

These authors took a different approach to Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 , 2008 ) in criticizing the NRP ( 2000 ) report. Rather than challenging the logic and analyses themselves, they noted that the effect sizes reported in the NRP were small and questioned their significance.

The NRP reported that systematic phonics instruction was effective across a variety of conditions, with 94% of the d ’s supporting the superiority of phonics instruction over other approaches. However, as noted by Hammill and Swanson, the standard convention in evaluating the magnitude of d sizes ( d = 0.2 is small, d = 0.5 medium, and d = 0.9 large) reveals that 65% of the significant d ’s were small. In order to get a better intuitive understanding of the practical significance of the results, the authors converted all these d ’s values to r -type statistics. They noted that the overall effect of 0.44 corresponds to an r 2 value of 0.04. That is, 96% of the variance in reading achievement can be attributed to factors other than the systematic phonics instruction. Footnote 2 The r 2 value for the follow-up analysis (4–12 months later) was 0.02.

What Hammill and Swanson do not acknowledge, however, is that these small effect sizes translate into real benefits when considering an entire population of children. The real problem is not with the size of the effects; it is that many of the critical contrasts were not significant or not assessed, that the small effects that were significant were inflated for the reasons noted above, and perhaps most importantly, the main meta-analysis did not even test the critical hypothesis of whether systematic phonics is better than unsystematic phonics that is used in alternative methods such as whole language.

Han ( 2010 ) and Adesope, Lavin, Tompson, and Ungerleider (2011)

These authors reported meta-analyses that assessed the efficacy of phonics for non-native English speakers learning English. Han ( 2010 ) included five different intervention conditions and dependent measures and reported the overall effect sizes as 0.33 for phonics, 0.41 for phonemic awareness, 0.38 for fluency, 0.34 for vocabulary, and 0.32 for comprehension. In the case of Adesope et al. ( 2011 ), the authors found that systematic phonics instruction improved performance ( g = + 0.40), but they also found that an intervention they called collaborative reading produced a larger effect ( g = + 0.48) as did a condition called writing (structured and diary) that produced an effect of g = + 0.54. Accordingly, ignoring all other potential issues discussed above, these studies do not provide any evidence that phonics is the most effective strategy for reading acquisition.

Sherman ( 2007 )

Sherman compared phonemic awareness and phonics instruction with students in grades 5 through 12 who read significantly below grade-level expectations. Neither method was found to provide a significant benefit.

Torgerson et al. ( 2018 )

Finally, Torgerson et al. carried out a systematic review of all meta-analyses that assessed the efficacy of systematic phonics (unlike the papers discussed above, this is not a meta-analysis itself). They identified 12 meta-analyses, all of which were considered above. The authors raised several concerns regarding design and publication bias of studies included in these meta-analyses and argued that more data (in the form of large randomized controlled studies) are needed before strong conclusions can be made. Nevertheless, the authors still conclude the evidence support systematic phonics, writing

Given the evidence from this tertiary review, what are the implications for teaching, policy and research? It would seem sensible for teaching to include systematic phonics instruction for younger readers – but the evidence is not clear enough to decide which phonics approach is best.

Despite their modest conclusions, the authors are still far too positive regarding the benefits of systematic phonics. In part, this is due to the way the authors summarize the findings they do report. But more importantly it is the consequence of ignoring many of key limitations of the meta-analyses discussed above.

With regard to their own summary of the meta-analyses, they stated that 10 the 12 meta-analyses showed that there were significant benefits of systematic phonics on at least one reading measure, with effect sizes ranging from small to moderate effects (Ehri et al. 2001 ; Camilli et al. 2003 ; Torgerson et al. 2006 ; Sherman 2007 ; Han 2010 ; Suggate 2010 ; Adesope et al. 2011 ; McArthur et al. 2012 ; Galuschka et al. 2014 ; Suggate 2016 ). Furthermore, they note that positive effects were found in the remaining nonsignificant meta-analyses (Camilli et al. 2006 ; Hammill and Swanson 2006 ). They take this to support the conclusion that teaching should include systematic phonics.

One problem with this description of the results is that it does not indicate which measures tended to be significant over the meta-analyses. In fact, as discussed above, most meta-analyses failed to obtain significant effects for the measure we should care about most. For example, only 1 of 12 studies reported significant effects in comprehension, and there is no evidence that this effect survived a delay (NRP 2000 ). And this characterization of the findings obscures the fact that the benefits did not always extend to the children who are below average in their cognitive capacities (NRP 2000 ).

This summary also does not highlight the fact that many of 12 meta-analyses observed larger effect sizes for non-phonics interventions. For example, from Table 3 of Torgerson et al. ( 2018 ), you find out that systematic phonics did not produce the largest effect in 5 of the 12 meta-analyses (Adesope et al. 2011 ; Camilli et al. 2003 ; Camilli et al. 2006 ; Han 2010 ; Suggate 2016 ). And this table does not include the Galuschka et al. ( 2014 ) meta-analysis that reported similar-sized effect sizes for phonics, phonemic awareness instruction, reading fluency training, and auditory training, with the largest numerical effect obtained with color overlays.

In addition, when claiming that 10 of the 12 meta-analyses reported significant benefits of systematic phonics, this included the Suggate ( 2010 ) meta-analysis that was challenged by a subsequent Suggate ( 2016 ) meta-analysis that failed to obtain long-term benefits of systematic phonics. Furthermore, the claim that 10 of the 12 meta-analyses reported a significant benefit for systematic phonics does not incorporate a key point highlighted by Torgerson et al. ( 2018 ) elsewhere in their review, namely, the evidence that publication and method bias have inflated these effect sizes in at least some of these meta-analyses.

The conclusion that systematic phonics is better than alternative methods is further compromised by additional factors not considered by Torgerson et al. ( 2018 ). As detailed above, there were multiple examples of methodological errors in the meta-analyses (e.g., excluding studies that should have been included given the inclusion criteria; Camilli et al. 2003 ; and including studies that should have been excluded given the exclusion criteria, Camilli et al. 2003 ; Torgerson et al. 2006 ), examples of including flawed studies that strongly biased the findings in support of systematic phonics (e.g., the Umbach et al. 1989 ; Levy and Lysynchuk 1997 , Levy et al. 1999 ), including non-English studies that biased the results in support of systematic phonics (Suggate 2010 ), amongst others. These errors consistently biased the estimates of systematic phonics upwards.

Most importantly, however, Torgerson et al. ( 2018 ) did not address the key point identified by Camilli et al. ( 2003 , 2006 , 2008 ) that compromises all meta-analyses used in support of systematic phonics, namely, systematic phonics was compared with a control condition that included both nonsystematic phonics and nonphonics conditions (or only included a nonphonics condition in the case of McArthur et al. 2012 ). Accordingly, these meta-analyses did not even test the hypothesis that systematic phonics is more effective than unsystematic phonics as used in whole language and other methods. For all these reasons, Torgerson et al.’s are unwarranted in their conclusion that systematic phonics is effective for young children.

Summary of Meta-Analyses

In sum, the above research provides little or no evidence that systematic phonics is better than standard alternative methods used in schools. The findings do not challenge the importance of learning grapheme-phoneme correspondences, but they do undermine the claim that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods that include unsystematic phonics (such as whole language) or that teach grapheme-phoneme correspondences along with meaning-based constraints on spellings (morphological instruction or structured word inquiry). There can be few areas in psychology in which the research community so consistently reaches a conclusion that is so at odds with available evidence.

The Systematic Phonics Experiment in England

One possible response to the many null results is to note that many of the studies included in these meta-analyses were flawed. On this view, the null results can be attributed to a limitation of the studies rather than any problems with systematic phonics per se. This is hard to reconcile with the fact that these meta-analyses have been cited thousands of times in support of systematic phonics. Nevertheless, the quality of the studies included in the meta-analyses has been repeatedly questioned (e.g., McArthur et al. 2012 ; Torgerson et al. 2006 , 2018 ), and accordingly, it is possible that systematic phonics is effective, but the meta-analyses are simply not picking his up. Another possible response is to note that systematic phonics needs to be taught in combination with many other skills, and the fact that phonics by itself does not improve reading outcomes is not surprising. Again, this is hard to reconcile with the claims that are drawn from the meta-analyses, but these concerns raise the question as to whether there are other sources of data that can be used to assess the benefits of systematic phonics when embedded in a broader literacy environment?

There is. In 2006, Sir Jim Rose wrote a UK government report concerned with the teaching of reading in primary schools in England where he concluded that “... the case for systematic phonic work is overwhelming …” (Rose 2006 , p. 20). Although this conclusion is unwarranted (see above), the report led to the legal requirement to teach synthetic systematic phonics in English state schools since 2007. And since 2012, a PSC was introduced in order to encourage better teaching of systematic phonics and to assess how well children decode regular words and pseudowords. Over 650,000 children took the PSC in 2018 alone. This constitutes a massive naturalistic experiment that can be used to assess the efficacy of systematic phonics, and indeed, it is widely claimed that the experiment has been a success with systematic phonics improving literacy. But once again, a careful look into the findings shows that the data do not support this conclusion. I summarize the findings next.

Machin et al.’s ( 2018 ) Analysis of Standard Assessment Test Results in England Provides Little or No Evidence in Support of Systematic Phonics

The authors took advantage of the fact that systematic phonics instruction was phased in slowly in different local authorities in England, and accordingly, it was possible to compare how children who were part of the systematic phonics trial compared with children who received standard instruction on various standardized language measures. In 2005, the “ Early Reading Development Pilot ” (ERDp) that involved 18 local authorities and 172 schools began with each school receiving funding for a dedicated learning consultant who trained teachers in systematic phonics (typically for 1 year). Then in 2006, the “ Communication, Language and Literacy Development Programme ” (CLLD) that included a further 32 local authorities began, again with each school receiving 1-year funding for a dedicated learning consultant.

In order to assess the immediate efficacy of introducing systematic phonics, scores from the communication, language, and literacy components of foundation stage assessment were collected (when children completed year 1 at age 5). And in order to assess the long-term effects of this intervention, reading scores from SATs key stage 1 (when children were 7 years of age) and reading scores from stage 2 test (when children were 11) were collected. These are standardized tests given to all students in state schools, with teachers providing the assessment in the foundation stage and key stage 1, and the tests externally marked in key stage 2. Various statistical methods were used to control for the differences between the schools included in the trials and those not included, and moderator variables included the impact of language background (native English or not) and economic background (operationalized as children receiving or not receiving a free school lunch).

For the ERDp sample, the authors reported highly significant effect of systematic phonics on the foundation stage assessment immediately after the intervention (0.298), but the effect dissipated on key stage 1 tests (0.075), and was eliminated on the key stage 2 tests (− 0.018). Similarly, with the CLLD treatment, an initially robust effect (0.217) was reduced on the key stage 1 tests (0.017), and then was lost on the key stage 2 tests (0.019). So much like the Suggate ( 2016 ) meta-analyses, the overall systematic phonics intervention effect did not persist. However, Machin et al. ( 2018 ) highlighted that the effects did persist in the key stage 2 tests in the CLLD treatment condition for non-native speakers (0.068) and economically disadvantaged children as measured by their receipt of free school meals (0.062), with both effects significant at the p < 0.05 levels. They took these small effects to show that phonics does provide long-term benefits for children who are in the most need for literacy interventions, writing

Without a doubt it is high enough to justify the fixed cost of a year’s intensive training support to teachers. Furthermore, it contributes to closing gaps based on disadvantage and (initial) language proficiency by family background.

However, there are both statistical and methodological problems with using these findings to support the efficacy of systematic phonics. With regard to the statistics, apart from the fact that there were no overall long-term effects in either sample, it is important to note that the ERDp sample of children did not show significant advantage for non-native speakers (.045) or for economically disadvantaged children (.050) on the key stage 2 tests. Indeed, for the ERDp sample, there was a tendency for more economically advantaged native English children (not in receipt of free school meals) to read more poorly in the phonics condition in the key stage 2 test (− 0.061), p < 0.1. As the authors write: “It is difficult to know what to make of this estimate” (p. 22). Note, the long-term negative outcome economically advantaged native English children in the ERDp sample was of a similar magnitude to the long-term benefits enjoyed non-native speakers (.068) and economically disadvantaged children (.062) in the CLLD treatment condition, and accordingly, is difficult to brush this finding aside.

More importantly, this study did not include the appropriate control condition. The advantages in foundation and key stage 1 were the product of intensive training support in systematic phonics to teachers in year 1, but it is possible that similar outcomes would result if intensive training support was given to teachers in whole language instruction, or any other method. As was the case with most of the above meta-analyses, the conclusion the authors made was not even tested.

The Recent Success of English Children on PIRLS Provides Little or No Evidence for Systematic Phonics

A great deal of attention in the mainstream and social media has been given to the recent success of English children in the “Progress in International Reading Literacy Study” (PIRLS) carried out in 2016. PIRLS assesses reading comprehension in fourth graders across a wide range of countries every 5 years: 35 countries participated in 2001, 38 in 2006, 48 in 2011, and 50 in 2016. Many supporters of systematic phonics have noted how far up the league table England has moved since 2006 given that systematic phonics was mandated in English state schools in 2007, and phonics check was introduced in 2012. Specifically, England was in 15th position in 2006 (with a score of 539), joint 11th position in 2011 (score 552), and joint 8th in 2016 (score 559).

In response to the most recent results, Mr. Gibbs, the Minister of State at the Department for Education, said

The details of these findings are particularly interesting. I hope they ring in the ears of opponents of phonics whose alternative proposals would do so much to damage reading instruction in this country and around the world.

A Department for Education report for the UK (December, 2016) reported

The present PIRLS findings provide additional support for the efficacy of phonics approaches, and in particular, the utility of the phonics check for flagging pupils’ potential for lower reading performance in their future schooling.

Sir Jim Rose, author of the Rose ( 2006 ) report, used “the spectacular success of England shown in the latest PIRLS data” as further evidence in support of systematic synthetic phonics (Rose 2017 ).

However, once again, these conclusions are unjustified. One important fact ignored in the above story is that English children did well in 2001, ranking third (scoring 553). Of the six countries that completed all the PIRLS tests from the beginning (England, New Zealand, Russian Federation, Singapore, Sweden, and USA), England has gone from second to third position. If the introduction of systematic phonics is used to explain the improved performance from 2006 to 2016, how is the excellent performance in 2001 explained? In addition, the results of the 2016 PIRLS were based on combing the performance of state and private schools (private schools were not required to implement systematic phonics or use the phonics check). When only state schools are considered, performance dropped to 11th (rather than joint 8th), same as the 2011 PIRLS rating (Solity 2018 ). Note that one of the common criticisms of systematic phonics is that the focus on phonology makes instruction less engaging. The PIRLS 2016 also ranked English children’s enjoyment of reading at 34th, the lowest of any English-speaking country (Solity 2018 ).

It is also interesting to note that Northern Ireland participated in the last two PIRLS, and they did better than England, ranking fifth and sixth in 2011 and 2016, respectively. This is relevant as the reading guidance for key stage 1 published by the “Northern Ireland Education & Library Boards” does not include the words “systematic phonics,” nor do children complete a phonics screening check that was introduced in the UK to improve the administration of phonics in English schools. Of course, reading instruction in Northern Ireland does teach children letter-sound correspondences, but this is carried out along with a range of methods that encourage children to encode the meaning of words and passages. For instance, according to the reading guidance for key stage 1, when children encounter an unknown word, various strategies for naming the word are encouraged, including phonics, using knowledge of context (semantics), and using knowledge of grammar (syntax). This is similar to National Literacy Strategy in place in England from 1998 to 2006 that recommended phonics as one of four “searchlights” for learning to read, along with knowledge of context, grammatical knowledge, word recognition and graphic knowledge. If the introduction of systematic phonics is used to explain the strong performance of England in 2016, how is the even better performance of Northern Ireland explained?

A final point worth emphasizing is that the PIRLS test assesses reading comprehension, and as noted above, only 1 of the 12 meta-analyses reported a benefit for comprehension (NRP 2000 ), and only at a short delay (ignoring the problems of this meta-analysis that question robustness of the short-term effect as well). Attributing any PIRLS gains to phonics is hard to reconcile with existing experimental research.

The Improving Performance on the Phonics Screening Check in England Provides Little or No Evidence that Systematic Phonics Improves Literacy

Since 2012, the UK government has required all children in state schools in England to complete a PSC in year 1 in order “to confirm that all children have learned phonic decoding to an age-appropriate standard” (Department for Education, 2012; p. 4). The phonics screening check is composed of one- and two-syllable real words (e.g., day, grit, shin) and 20 pseudowords that can only be read on the basis of learned grapheme-phoneme correspondences (e.g., fape, blan, geck). Children near the end of year 1 are asked to read the words and pseudowords aloud, with each item marked correct or incorrect. A child who correctly names aloud 32 items (80% of all items) is said the “meet the standard,” whereas a child who misses the standard is to be given further support to improve their phonics knowledge (and complete the phonics check again in year 2).

Strikingly, the performance on the task has improved from 58% students meeting the standard in 2012 to 82% in 2018. This is taken to show that the PSC has improved the teaching of systematic phonics, and this in turn has improved decoding skills. The critical question is whether this has translated into better reading.

The obvious way to test whether the improved decoding skills translate to better reading is to compare the PSC results to the SATs carried out at key stages 1 and 2 during the years 2012–2017. These are the same tests analyzed by Machin et al. ( 2018 ) above (although they analyzed data from before 2012). And in fact, there have been some claims that improved performance on the phonics screening check is associated with improved performance on the SATS. For instance, Buckingham ( 2016 ) writes

There has also been an improvement in Key Stage 1 (Year 2) reading and writing results since the introduction of the Phonics Screening Check. The proportion of students achieving at or above the target reading level hovered around 85% from 2005 to 2011 but steadily increased to 90% in 2015. There was an even greater improvement in writing in the same period—a seven percentage point increase. (p. 16)

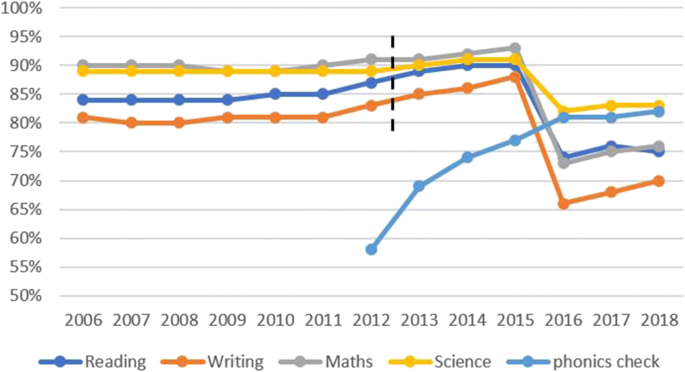

The results of the phonics check and the key stage 1 SAT scores are displayed in Fig. 1 .

Results on key stage 1 SAT tests in reading, writing, maths, and science from 2006 to 2018 as well as the results of the phonics screening check from 2012 to 2018. SAT scores to the left of vertical dashed line were achieved without having completed the phonics screening check in year 1, and SAT scores to the right of the vertical dashed lined were achieved after having completed the phonics check in year 1. Accordingly, the improved SAT results on reading and writing between 2011 and 2012 cannot be attributed to the improved administration of phonics

But this characterization of the findings is inconsistent with a report from the Department for Education (Walker, Sainsbury, Worth, Bamforth, & Betts, 2015 ). The authors analyzed the reading and writing scores for the KS1 for the 2 years preceding and following the introduction of the screening check and concluded:

The evidence offered by these analyses is therefore inconclusive in identifying any impact of the [phonics screening check] on literacy performance at KS1 or on progress in literacy between ages five and seven.

Why the different conclusions? One key point to note is that although the SAT scores did start slowly increasing in 2012 (consistent with Buckingham 2016 ), it is not possible to attribute these gains to the phonics screening check because these children completed year 1 in 2011, and accordingly, were never given the PSC. As noted by Walker et al. ( 2015 ):

These analyses of national data therefore indicate small improvements in attainment at KS1, which were a feature before the introduction of the check and continued at a similar pace following the introduction of the check.

In addition, as can be seen from Fig. 1 , there is little evidence that SAT scores for reading and writing improved more than SAT scores for maths or science between 2013 and 2015 or between 2016 and 2018. Footnote 3