When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

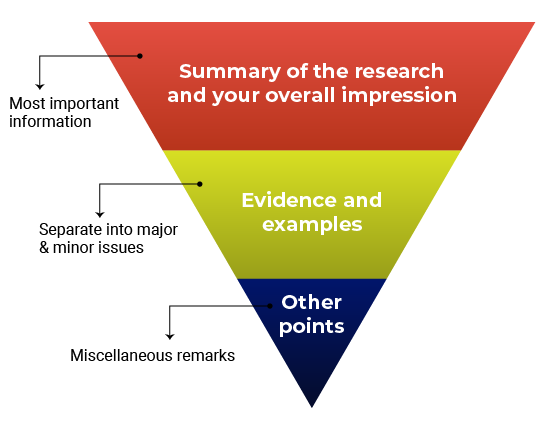

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

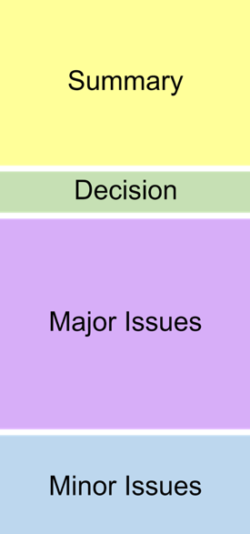

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

University Writing Program

- Peer Review

- Collaborative Writing

- Writing for Metacognition

- Supporting Multilingual Writers

- Alternatives to Grading

- Making Feedback Matter

- Responding to Multilingual Writers’ Texts

- Model Library

Written by Rebecca Wilbanks

Peer review is a workhorse of the writing classroom, for good reason. Students receive feedback from each other without the need for the instructor to comment on every submission. In commenting on each other’s work, they develop critical judgment that they can bring to bear on their own writing. Working peer review into the schedule requires students to complete a draft ahead of the final deadline and sets the expectation that they will revise. Students benefit from seeing how others executed similar writing tasks. Finally, the skills that students practice during peer review—soliciting, providing, receiving, and responding to feedback—are essential to success in both scholarly and professional contexts.

While students often report that they found peer review to be valuable, students and faculty sometimes worry that peer feedback may be inaccurate or unhelpful. These concerns are valid: for peer review to be successful, students must receive clear instructions about what aspects of the text to focus on and training in how to formulate responses to peer drafts. The class must develop a shared sense of standards and a language to articulate them. The good news is that when peer review is supported in these ways, substantial evidence supports peer review’s benefits. With appropriate preparation, Melzer and Bean report that three or more students collectively produce feedback analogous to that of an instructor. Some classes even use a rigorous peer review system to generate grades for assignments .

It’s best to put the guidelines for your peer review in writing. These guidelines could take the form of a set of questions for students to respond to, a rubric to fill out (usually the same rubric that will be used to grade the assignment), or instructions for writing a response letter to the writer. Students will also benefit from seeing examples of helpful (and less helpful) feedback comments. You can use these sample comments to push students to provide greater specificity in their feedback (Less helpful: “Nice work. You did a really good job on this assignment.” More helpful: “I really like how you responded to the claims of Author X.”)

What to Ask of Student Reviewers

As you design the peer review, consider how you will balance these different options:

- Asking students to identify elements in the text. This approach allows students to check that expected elements of the text are present and legible to the audience. E.g.: Highlight the sentence(s) where the author states their thesis; or, identify the part of the text where the author explains the significance of their findings. In doing so, students practice recognizing the expected components of the genre they are working in, the different forms these components may take, and they help each other spot when a component is missing or underdeveloped.

- Asking students to record their reactions as a reader. This option harnesses the power of peer review to provide a real audience. Here are some examples of reader-response comments: “Oh, now I see why you brought up [x]; it seems like your point is [y]”; “I’m having trouble with this sentence; I had to go back and read it a couple times”; “I understand this paragraph to be saying [x]…”; “This is a really neat point; I hadn’t thought of making that connection before.” This approach is based on the idea that understanding how one’s writing is coming across to readers and making changes accordingly is an essential part of the revision process.

- Asking students to make judgments and/ or give advice. Students may evaluate the work with a rubric or be asked to summarize what is working well and what the student should prioritize for revision. This approach requires more training and practice with models to ensure that students and faculty have a shared understanding of how to apply the assessment criteria, and will be more successful as students gain more exposure to the genre they are working in. In these peer review guidelines from an upper-level writing course, you can see how I incorporated identification, reader-response, and evaluation.

How to Structure a Peer Review Session

- A workshop with the entire class or section. In this case, everyone reads and comments on the same draft(s), often ahead of time. This format allows the instructor to guide the conversation and may be particularly helpful at the beginning of the semester. You may use the workshop format to review a sample assignment from a previous semester as practice before students review each other’s work.

- As an alternative to having each student read and comment on each draft individually, Melzer and Bean suggest having groups exchange papers with other groups, and collaboratively write responses to each paper.

- Asynchronous and online. By using the peer review function on Canvas, or online platforms such as Peerceptiv, CPR, or Eli review, instructors can assign peer review as a homework assignment and avoid taking up class time. Applications designed expressly for peer review include features that encourage high quality review; for example, CPR requires students to pass a “calibration test” (in which they give feedback on models that have already been graded by the instructor), while Peerceptiv allows students to rate the quality of peer reviews during the revision process in an anonymous system that awards points for helpful feedback.

How to Get the Most out of Peer Review

Here are a few other suggestions to make peer review as effective as possible:

- Give students feedback on their feedback. If students are working in class, you can circulate through the different groups, reinforce insightful comments, and ask follow-up questions to get them to add depth or consider new aspects. You can also spot-check peer reviews and highlight examples of good feedback or ways to improve comments in class. Finally, you might ask students what feedback was most helpful during the revision process and recognize reviewers who do especially good work.

- Be aware that some students may put their energy into editing the paper, focusing on grammar and sentence structure rather than higher-level issues. This is especially likely when English is not the first language of the author being reviewed. Make sure to emphasize that the goal of peer review is to focus on higher-level concerns, and recurring issues of expression that affect readability—not to line-edit. The Sweetland Center for Writing at the University of Michigan has guidelines and evaluation criteria for peer reviews tailored for situations involving multilingual students.

- To encourage students to make use of the feedback, consider giving students time in class after the peer review to start working on their revisions or make notes about how they will begin.

Cited and Recommended Sources

- Corbett, Steven J., et al., editors. Peer Pressure, Peer Power: Theory and Practice in Peer Review and Response for the Writing Classroom . First edition, Fountainhead Press, 2014.

- Corbett, Steven J., and Michelle LaFrance, editors. Student Peer Review and Response: A Critical Sourcebook . Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2018.

- Double, Kit S., et al. “The Impact of Peer Assessment on Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Control Group Studies.” Educational Psychology Review , vol. 32, no. 2, June 2020, pp. 481–509. Springer Link , https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09510-3 .

- Huisman, Bart, et al. “Peer Feedback on Academic Writing: Undergraduate Students’ Peer Feedback Role, Peer Feedback Perceptions and Essay Performance.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education , vol. 43, no. 6, Aug. 2018, pp. 955–68. Taylor and Francis+NEJM , https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1424318 .

- Lundstrom, Kristi, and Wendy Baker. “To Give Is Better than to Receive: The Benefits of Peer Review to the Reviewer’s Own Writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing , vol. 18, no. 1, Mar. 2009, pp. 30–43. ScienceDirect , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002 .

- Melzer, Dan, and John C. Bean. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . 3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, 2021, https://www.amazon.com/Engaging-Ideas-Professors-Integrating-Classroom/dp/1119705401 .

- Price, Edward, et al. “Validity of Peer Grading Using Calibrated Peer Review in a Guided-Inquiry, Conceptual Physics Course.” Physical Review Physics Education Research , vol. 12, no. 2, Dec. 2016, p. 020145. APS , https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020145 .

- Rahimi, Mohammad. “Is Training Student Reviewers Worth Its While? A Study of How Training Influences the Quality of Students’ Feedback and Writing.” Language Teaching Research , vol. 17, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 67–89. SAGE Journals , https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168812459151 .

- Using Peer Review to Improve Student Writing. University of Michigan Sweetland Center for Writing. Accessed 15 Jan. 2023.

- van den Berg, Ineke, et al. “Designing Student Peer Assessment in Higher Education: Analysis of Written and Oral Peer Feedback.” Teaching in Higher Education , vol. 11, no. 2, Apr. 2006, pp. 135–47. srhe.tandfonline.com (Atypon) , https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527685 .

Peer Reviews

Use the guidelines below to learn how best to conduct a peer draft review.

For further information see our handout on How to Proofread.

Before you read and while you read the paper

- Find out what the writer is intending to do in the paper (purpose) and what the intended audience is.

- Find out what the writer wants from a reader at this stage.

- Read (or listen) to the entire draft before commenting.

What to include in your critique

- Praise what works well in the draft; point to specific passages.

- Comment on large issues first (Does the draft respond to the assignment? Are important and interesting ideas presented? Is the main point clear and interesting? Is there a clear focus? Is the draft effectively organized? Is the sequence of points logical? Are ideas adequately developed? If appropriate, is the draft convincing in its argument? Is evidence used properly?). Go on to smaller issues later (awkward or confusing sentences, style, grammar, word choice, proofreading).

- Time is limited (for your response and for the author’s revision), so concentrate on the most important ways the draft could be improved.

- Comment on whether the introduction clearly announces the topic and suggests the approach that will be taken; on whether ideas are clear and understandable.

- Be specific in your response (explain where you get stuck, what you don’t understand) and in your suggestions for revision. And as much as you can, explain why you’re making particular suggestions.

- Try describing what you see (or hear) in the paper–what you see as the main point, what you see as the organizational pattern.

- Identify what’s missing, what needs to be explained more fully. Also identify what can be cut.

How to criticize appropriately

- Be honest (but polite and constructive) in your response

- Don’t argue with the author or with other respondents.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

- Peer Review Checklist

Each essay is made up of multiple parts. In order to have a strong essay each part must be logical and effective. In many cases essays will be written with a strong thesis, but the rest of the paper will be lacking; making the paper ineffective. An essay is only as strong as its weakest point.

Using a checklist to complete your review will allow you to rate each of the parts in the paper according to their strength. There are many different peer review checklists, but the one below should be helpful for your assignment.

- Is the thesis clear?

- Does the author use his or her own ideas in the thesis and argument?

- Is the significance of the problem in the paper explained? Is the significance compelling?

- Are the ideas developed logically and thoroughly?

- Does the author use ethos effectively?

- Does the author use pathos effectively?

- Are different viewpoints acknowledged?

- Are objections effectively handled?

- Does the author give adequate explanations about sources used?

- Are the sources well-integrated into the paper, or do they seem to be added in just for the sake of adding sources?

- Is the word choice specific, concrete and interesting?

- Are the sentences clear?

- Is the overall organization of the argument effective?

- Are the transitions between paragraphs smooth?

- Are there any grammatical errors?

Based on the rubric found at: Grading Rubric Template (Word)

- Authored by : J. Indigo Eriksen. Provided by : Blue Ridge Community College. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of checklist. Authored by : Jurgen Appelo. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/hykfe7 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Peer Review Checklist. Authored by : Robin Parent. Provided by : Utah State University English Department. Project : USU Open CourseWare Initiative. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Table of Contents

Instructor Resources (Access Requires Login)

- Overview of Instructor Resources

An Overview of the Writing Process

- Introduction to the Writing Process

- Introduction to Writing

- Your Role as a Learner

- What is an Essay?

- Reading to Write

- Defining the Writing Process

- Videos: Prewriting Techniques

- Thesis Statements

- Organizing an Essay

- Creating Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Editing and Proofreading

- Matters of Grammar, Mechanics, and Style

- Comparative Chart of Writing Strategies

Using Sources

- Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Formatting the Works Cited Page (MLA)

- Citing Paraphrases and Summaries (APA)

- APA Citation Style, 6th edition: General Style Guidelines

Definition Essay

- Definitional Argument Essay

- How to Write a Definition Essay

- Critical Thinking

- Video: Thesis Explained

- Effective Thesis Statements

- Student Sample: Definition Essay

Narrative Essay

- Introduction to Narrative Essay

- Student Sample: Narrative Essay

- "Shooting an Elephant" by George Orwell

- "Sixty-nine Cents" by Gary Shteyngart

- Video: The Danger of a Single Story

- How to Write an Annotation

- How to Write a Summary

- Writing for Success: Narration

Illustration/Example Essay

- Introduction to Illustration/Example Essay

- "She's Your Basic L.O.L. in N.A.D" by Perri Klass

- "April & Paris" by David Sedaris

- Writing for Success: Illustration/Example

- Student Sample: Illustration/Example Essay

Compare/Contrast Essay

- Introduction to Compare/Contrast Essay

- "Disability" by Nancy Mairs

- "Friending, Ancient or Otherwise" by Alex Wright

- "A South African Storm" by Allison Howard

- Writing for Success: Compare/Contrast

- Student Sample: Compare/Contrast Essay

Cause-and-Effect Essay

- Introduction to Cause-and-Effect Essay

- "Cultural Baggage" by Barbara Ehrenreich

- "Women in Science" by K.C. Cole

- Writing for Success: Cause and Effect

- Student Sample: Cause-and-Effect Essay

Argument Essay

- Introduction to Argument Essay

- Rogerian Argument

- "The Case Against Torture," by Alisa Soloman

- "The Case for Torture" by Michael Levin

- How to Write a Summary by Paraphrasing Source Material

- Writing for Success: Argument

- Student Sample: Argument Essay

- Grammar/Mechanics Mini-lessons

- Mini-lesson: Subjects and Verbs, Irregular Verbs, Subject Verb Agreement

- Mini-lesson: Sentence Types

- Mini-lesson: Fragments I

- Mini-lesson: Run-ons and Comma Splices I

- Mini-lesson: Comma Usage

- Mini-lesson: Parallelism

- Mini-lesson: The Apostrophe

- Mini-lesson: Capital Letters

- Grammar Practice - Interactive Quizzes

- De Copia - Demonstration of the Variety of Language

- Style Exercise: Voice

Use of cookies

Lund University uses cookies to ensure that the website functions properly and to improve your experience.

Read more in our cookie policy

- AWELU contents

- Writing at university

- Different kinds of student texts

- Understanding instructions and stylesheets

- Understanding essay/exam questions

- Peer review instructions

- Dealing with feedback

- Checklist for writers

- Research writing resources

- Administrative writing resources

- LU language policy

- Introduction

- What characterises academic writing?

- The heterogeneity of academic writing

- Three-part essays

- IMRaD essays

- How to get started on your response paper

- Student literature review

- Annotated bibliography

- Three versions of the RA

- Examples of specificity within disciplines

- Reviews (review articles and book reviews)

- Popular science writing

- Research posters

- Grant proposals

- Writing for Publication

- Salutations

- Structuring your email

- Direct and indirect approaches

- Useful email phrases

- Language tips for email writers

- Writing memos

- Meeting terminology

- The writing process

- Identifying your audience

- Using invention techniques

- Research question

- Thesis statement

- Developing reading strategies

- Taking notes

- Identifying language resources

- Choosing a writing tool

- Framing the text: Title and reference list

- Structure of the whole text

- Structuring the argument

- Structure of introductions

- Structure within sections of the text

- Structure within paragraphs

- Signposting the structure

- Using sources

- What needs to be revised?

- How to revise

- Many vs. much

- Other quantifiers

- Quantifiers in a table

- Miscellaneous quantifiers

- Adjectives and adverbs

- Capitalisation

- Sentence fragment

- Run-on sentences

- What or which?

- Singular noun phrases connected by "or"

- Singular noun phrases connected by "either/or"

- Connected singular and plural noun phrases

- Noun phrases conjoined by "and"

- Subjects containing "along with", "as well as", and "besides"

- Indefinite pronouns and agreement

- Sums of money and periods of time

- Words that indicate portions

- Uncountable nouns

- Dependent clauses and agreement

- Agreement with the right noun phrase

- Some important exceptions and words of advice

- Atypical nouns

- The major word classes

- The morphology of the major word classes

- Words and phrases

- Elements in the noun phrase

- Classes of nouns

- Determiners

- Elements in the verb phrase

- Classes of main verbs

- Auxiliary verbs

- Primary auxiliary verbs

- Modal auxiliary verbs

- Meanings of modal auxiliaries

- Marginal auxiliary verbs

- Time and tense

- Simple and progressive forms

- The perfect

- Active and passive voice

- Adjective phrases

- Adverb phrases

- Personal pronouns

- Dummy pronouns

- Possessive pronouns

- Interrogative pronouns

- Indefinite pronouns

- Quantifiers

- Prepositions and prepositional phrases

- More on adverbials

- The order of subjects and verbs

- Subject-Verb agreement

- Hyphen and dash

- English spelling rules

- Commonly confused words

- Differences between British and American spelling

- Vocabulary awareness

- Useful words and phrases

- Using abbreviations

- Register types

- Formal vs. informal

- DOs & DON'Ts

- General information on dictionary use

- Online dictionary resources

- What is a corpus?

- Examples of the usefulness of a corpus

- Using the World Wide Web as a corpus

- Online corpus resources

- Different kinds of sources

- The functions of references

- Paraphrasing

- Summarising

- Reference accuracy

- Reference management tools

- Different kinds of reference styles

- Style format

- Elements of the reference list

- Documentary note style

- Writing acknowledgements

- What is academic integrity?

- Academic integrity and writing

- Academic integrity at LU

- Different kinds of plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- About Awelu

- Start here AWELU contents Student writing resources Research writing resources Administrative writing resources LU language policy

- Genres Introduction The Nature of Academic Writing Student writing genres Writing in Academic Genres Writing for Publication Writing for Administrative Purposes

- Writing The writing process Pre-writing stage Writing stage Rewriting stage

- Language Introduction Common problems and how to avoid them Selective mini grammar Coherence Punctuation Spelling Focus on vocabulary Register and style Dictionaries Corpora - resources for writer autonomy References

- Referencing Introduction Different kinds of sources The functions of references How to give references Reference accuracy Reference management tools Using a reference style Quick guides to reference styles Writing acknowledgements

- Academic integrity What is academic integrity? Academic integrity and writing Academic integrity at LU Plagiarism

Peer review

What is peer review.

Peer review is a common activity at university, both among students and among senior researchers. In many undergraduate courses, peer reviewing forms part of the learning process, and papers and chapters by PhD students are scrutinised in departmental research seminars. Although writers might feel intimidated by the idea of submitting their (unfinished) texts to other people, texts usually improve as a result of being questioned and commented on. The task of the peer reviewer is to help the writer sharpen his or her argument and improve his or her texts. Importantly, by reviewing other writers’ texts, peer reviewers also train their own analytical abilities.

Although the principle is the same, peer review among students looks slightly different from the peer-review process carried out before scholarly texts are published in journals, for instance.

Student peer review

Students are often asked to peer review other students' writing. Here, the word peer means another student, usually in the same course, who can be expected to have a similar level of understanding of the general topic dealt with in the text (although the writer will probably have more expert knowledge of the particular aspect dealt with in their text).

- Further down on this page we provide information and tips for student peer reviewers.

Scholarly peer review

When an author has submitted a text to a journal, it will be reviewed by other scholars within the field. Depending on the assessment and comments provided by the peer reviewers, the manuscript will then be either accepted or rejected by the publisher / editor. Articles that are accepted for publication usually have to go through minor or major revisions before being published.

Peer reviewers of scholarly work receive instructions from the publisher outlining what to comment on and how to assess the text. Such instructions usually cover both general aspects of research and presentation and more detailed, journal-specific, preferences.

Reading someone else's text: Student peer reviewing

Student peers reviewing during the writing process can take different forms. In some courses, students work in peer groups and review each other's work-in-progress, for instance, and papers and chapters by PhD students are often scrutinised in departmental research seminars or read and commented upon by assigned readers. Although writers might feel intimidated by the idea of submitting their (unfinished) texts to someone else, texts usually improve as a result of being questioned and commented on.

The task of peer reviewers is to help writers sharpen their arguments and improve their texts. By reviewing other writers’ texts, peer reviewers thereby also train their own analytical abilities. Encountering different ways of structuring a paper, or of presenting facts and arguments, gives the peer reviewer an increased understanding of writing.

The video below presents some fundamental aspects of peer review work at university:

Instructional video from the free online MOOC "Writing in English at University" which was developed at Lund University in 2016.

AWELU peer review guidelines for students

Note that our guidelines are of a general kind and that your teachers may have set instructions covering other aspects:

When you receive feedback from your peers, it is important that you make use of it in a way that helps you develop your text. See here for some advice:

- Dealing with peer review feedback

You are using an outdated browser . Please upgrade your browser today !

What Is Peer Review and Why Is It Important?

It’s one of the major cornerstones of the academic process and critical to maintaining rigorous quality standards for research papers. Whichever side of the peer review process you’re on, we want to help you understand the steps involved.

This post is part of a series that provides practical information and resources for authors and editors.

Peer review – the evaluation of academic research by other experts in the same field – has been used by the scientific community as a method of ensuring novelty and quality of research for more than 300 years. It is a testament to the power of peer review that a scientific hypothesis or statement presented to the world is largely ignored by the scholarly community unless it is first published in a peer-reviewed journal.

It is also safe to say that peer review is a critical element of the scholarly publication process and one of the major cornerstones of the academic process. It acts as a filter, ensuring that research is properly verified before being published. And it arguably improves the quality of the research, as the rigorous review by like-minded experts helps to refine or emphasise key points and correct inadvertent errors.

Ideally, this process encourages authors to meet the accepted standards of their discipline and in turn reduces the dissemination of irrelevant findings, unwarranted claims, unacceptable interpretations, and personal views.

If you are a researcher, you will come across peer review many times in your career. But not every part of the process might be clear to you yet. So, let’s have a look together!

Types of Peer Review

Peer review comes in many different forms. With single-blind peer review , the names of the reviewers are hidden from the authors, while double-blind peer review , both reviewers and authors remain anonymous. Then, there is open peer review , a term which offers more than one interpretation nowadays.

Open peer review can simply mean that reviewer and author identities are revealed to each other. It can also mean that a journal makes the reviewers’ reports and author replies of published papers publicly available (anonymized or not). The “open” in open peer review can even be a call for participation, where fellow researchers are invited to proactively comment on a freely accessible pre-print article. The latter two options are not yet widely used, but the Open Science movement, which strives for more transparency in scientific publishing, has been giving them a strong push over the last years.

If you are unsure about what kind of peer review a specific journal conducts, check out its instructions for authors and/or their editorial policy on the journal’s home page.

Why Should I Even Review?

To answer that question, many reviewers would probably reply that it simply is their “academic duty” – a natural part of academia, an important mechanism to monitor the quality of published research in their field. This is of course why the peer-review system was developed in the first place – by academia rather than the publishers – but there are also benefits.

Are you looking for the right place to publish your paper? Find out here whether a De Gruyter journal might be the right fit.

Besides a general interest in the field, reviewing also helps researchers keep up-to-date with the latest developments. They get to know about new research before everyone else does. It might help with their own research and/or stimulate new ideas. On top of that, reviewing builds relationships with prestigious journals and journal editors.

Clearly, reviewing is also crucial for the development of a scientific career, especially in the early stages. Relatively new services like Publons and ORCID Reviewer Recognition can support reviewers in getting credit for their efforts and making their contributions more visible to the wider community.

The Fundamentals of Reviewing

You have received an invitation to review? Before agreeing to do so, there are three pertinent questions you should ask yourself:

- Does the article you are being asked to review match your expertise?

- Do you have time to review the paper?

- Are there any potential conflicts of interest (e.g. of financial or personal nature)?

If you feel like you cannot handle the review for whatever reason, it is okay to decline. If you can think of a colleague who would be well suited for the topic, even better – suggest them to the journal’s editorial office.

But let’s assume that you have accepted the request. Here are some general things to keep in mind:

Please be aware that reviewer reports provide advice for editors to assist them in reaching a decision on a submitted paper. The final decision concerning a manuscript does not lie with you, but ultimately with the editor. It’s your expert guidance that is being sought.

Reviewing also needs to be conducted confidentially . The article you have been asked to review, including supplementary material, must never be disclosed to a third party. In the traditional single- or double-blind peer review process, your own anonymity will also be strictly preserved. Therefore, you should not communicate directly with the authors.

When writing a review, it is important to keep the journal’s guidelines in mind and to work along the building blocks of a manuscript (typically: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, tables, figures).

After initial receipt of the manuscript, you will be asked to supply your feedback within a specified period (usually 2-4 weeks). If at some point you notice that you are running out of time, get in touch with the editorial office as soon as you can and ask whether an extension is possible.

Some More Advice from a Journal Editor

- Be critical and constructive. An editor will find it easier to overturn very critical, unconstructive comments than to overturn favourable comments.

- Justify and specify all criticisms. Make specific references to the text of the paper (use line numbers!) or to published literature. Vague criticisms are unhelpful.

- Don’t repeat information from the paper , for example, the title and authors names, as this information already appears elsewhere in the review form.

- Check the aims and scope. This will help ensure that your comments are in accordance with journal policy and can be found on its home page.

- Give a clear recommendation . Do not put “I will leave the decision to the editor” in your reply, unless you are genuinely unsure of your recommendation.

- Number your comments. This makes it easy for authors to easily refer to them.

- Be careful not to identify yourself. Check, for example, the file name of your report if you submit it as a Word file.

Sticking to these rules will make the author’s life and that of the editors much easier!

Explore new perspectives on peer review in this collection of blog posts published during Peer Review Week 2021

[Title image by AndreyPopov/iStock/Getty Images Plus

David Sleeman

David Sleeman worked as a Senior Journals Manager in the field of Physical Sciences at De Gruyter.

You might also be interested in

Academia & Publishing

Taking Libraries into the Future, Part 2: An Interview with Mike Jones and Tomasz Stompor

Embracing diversity, equity and inclusion: social justice and the modern university, taking libraries into the future, part 1: an interview with mark hughes, visit our shop.

De Gruyter publishes over 1,300 new book titles each year and more than 750 journals in the humanities, social sciences, medicine, mathematics, engineering, computer sciences, natural sciences, and law.

Pin It on Pinterest

How to perform a peer review

You’ve received or accepted an invitation to review an article. Now the work begins. Here are some guidelines and a step by step guide to help you conduct your peer review.

General and Ethical Guidelines

Step by Step Guide to Reviewing a Manuscript

Top Tips for Peer Reviewers

Working with Editors

Reviewing Revised Manuscripts

Tips for Reviewing a Clinical Manuscript

Reviewing Registered Reports

Tips for Reviewing Rich Media

Reviewing for Sound Science

Peer Review – Best Practices

“Peer review is broken. But let’s do it as effectively and as conscientiously as possible.” — Rosy Hosking, CommLab

“ A thoughtful, well-presented evaluation of a manuscript, with tangible suggestions for improvement and a recommendation that is supported by the comments, is the most valuable contribution that you can make as a reviewer, and such a review is greatly appreciated by both the authors of the manuscript and the editors of the journal. ” — ACS Reviewer Lab

Criteria for success

A successful peer review:

- Contains a brief summary of the entire manuscript. Show the editors and authors what you think the main claims of the paper are, and your assessment of its impact on the field. What did the authors try to show and what did they try to claim?

- Clearly directs the editor on the path forward. Should this paper be accepted, rejected, or revised?

- Identifies any major (internal inconsistencies, missing data, etc.) concerns, and clearly locates them within the document. Why do you think that the direction specified is correct? What were the issues you identified that led you to that decision?

- Lists (if appropriate — i.e. if you are suggesting revision or acceptance) minor concerns to help the authors make the paper watertight (typographical errors, grammatical errors, missing references, unclear explanations of methodology, etc.).

- Explain how the arguments can be better defended through analysis, experiments, etc.

- Is reasonable within the original manuscript scope ; does not suggest modifications that would require excessive time or expense, or that could instead be addressed by adjusting the manuscript’s claims .

Structure Diagram

A typical peer review is 1-2 pages long. You can divide your content roughly as follows:

Identify your purpose

The purpose of your pre-publication peer review is two-fold:

- Scientific integrity (which can be handled with editorial office assistance)

- Quality of data collection methods and data analysis

- Veracity of conclusions presented in the manuscript

- Determine match between the proposed submission and the journal scope (subject matter and potential impact). For example, a paper that holds significance only for a particular subfield of chemical engineering is not appropriate for a broad multidisciplinary journal. Determining match is usually done in partnership with the editor, who can answer questions of journal scope.

Analyze your audience

The audience for your peer review work is unusual compared to most other kinds of communication you will undertake as a scientist. Your primary audience is the journal editor, who will use your feedback to make a decision to accept or reject the manuscript. Your secondary audience is the author, who will use your suggestions to make improvements to the manuscript. Typically, you will be known to the journal editors, but anonymous to the authors of the manuscript. For this reason, it is important that you balance your review between these two parties.

The editors are most interested in hearing your critical feedback on the science that is presented, and whether there are any claims that need to be adjusted. The editors need to know:

- Your areas of expertise within the manuscript

- The paper’s significance to your particular field

To help you, most journals willhave guidelines for reviewers to follow, which can be found on the journal’s website (e.g., Cell Guidelines ).

The authors are interested in:

- Understanding what aspects of their logic are not easily understood

- Other layers of experimentation or discussion that would be necessary to support claims

- Any additional information they would need to convince you in their arguments

Format Your Document in a Standard Way

Peer review feedback is most easily digested and understood by both editors and authors when it arrives in a clear, logical format. Most commonly the format is (1) Summary, (2) Decision, (3) Major Concerns, and (4) Minor Concerns (see also Structure Diagram above).

There is also often a multiple choice form to “rate” the paper on a number of criteria. This numerical scoring guide may be used by editors to weigh the manuscript against other submissions; think of it mostly as a checklist of topics to cover in your review.

The summary grounds the remainder of your review. You need to demonstrate that you have read and understood the manuscript, which helps the authors understand what other readers are understanding to be the manuscript’s main claims. This is also an opportunity to demonstrate your own expertise and critical thinking, which makes a positive impression on the editors who often may be important people in your field.

It is helpful to use the following guidelines:

- Start with a one-sentence description of the paper’s main point, followed by several sentences summarizing specific important findings that lead to the paper’s logical conclusion.

- Then, highlight the significance of the important findings that were shown in the paper.

- Conclude with the reviewer’s overall opinion of what the manuscript does and does not do well.

Your decision must be clearly stated to aid the interpretation of the rest of your comments (see Criteria for Success). Do this either as part of the concluding sentence in the summary paragraph, or as a separate sentence after the summary. In general, you try to categorize within the following framework:

- Accept with no revisions

- Accept with minor revisions

- Accept with major revisions

Some journals will have specific rules or different wording, so make sure you understand what your options are.

Most reviews also contain the option to provide confidential comments to the editor, which can be used to provide the editor with more detail on the decision. In extreme cases, this can also be where concerns about plagiarism, data manipulation, or other ethical issues can be raised.

The Decision area is also where you can state which aspects of complex manuscripts you feel you have the expertise to comment on.

Major Concerns (where relevant)

Depending on the journal that you are reviewing for, there might be criteria for significance, novelty, industrial relevance, or other field-specific criteria that need to be accounted for in your major concerns. Major concerns, if they are serious, typically lead to decisions that are either “reject” or “accept with major revisions.”

Major concerns include…

- issues with the arguments presented in the paper that are not internally consistent,

- or present arguments that go against significant understanding in the field, without the necessary data to back it up .

- a lack of key experimental or computational data that are vital to justify the claims made in the paper.

- Examples: a study that reports the identity of an unexpected peak in a GC-MS spectrum without accounting for common interferences, or claims pertaining to human health when all the data presented is in a model organism or in vitro .

One of the most important aspects of providing a review with major concerns is your ability to cite resolutions. For example…

- If you think that someone’s argument is going against the laws of thermodynamics, what data would they need to show you to convince you otherwise?

- What types of new statistical analysis would you need to see to believe the claims being made about the clinical trials presented in this work?

- Are there additional control experiments that are needed to show that this catalyst is actually promoting the reaction along the pathway suggested?

Minor Concerns (optional)

Minor concerns are primarily issues that are raised that would improve the clarity of the message, but don’t impact the logic of the argument. Most commonly these are…

- Grammatical errors within the manuscript

- Typographical errors

- Missing references

- Insufficient background or methods information (e.g., an introduction section with only five references)

- Insufficient or possibly extraneous detail

- Unclear or poorly worded explanations (e.g., a paragraph in the discussion section that seems to contradict other parts of the paper)

- Possible options for improving the readability of any graphics (e.g., incorrect labels on a figure)

While minor concerns are not always present in the case of reviews with many major concerns, they are almost always included in the case of manuscripts where the decision is an accept or accept with minor revisions.

Offer revisions that are reasonable and in scope

Think about the feasibility of the experiments you suggest to address your concerns. Are you suggesting 3 years’ more work that could form the basis for a whole other publication? If you are suggesting vast amounts of animal work or sequencing, then are the experiments going to be prohibitively expensive? If the paper would stand without this next layer of experimentation, then think seriously about the real value of these additional experiments. One of the major issues with scientific publishing is the length of time taken to get to the finish line. Don’t muddy the water for fellow authors unnecessarily!

As an alternative to more experiments, does the author need to adjust their claims to fit the extent of their evidence rather than the other way round? If they did that, would this still be a good paper for the journal you are reviewing for?

Structure your comments in a way that makes sense to the audience

Formatting choices:

- Separate each of your concerns clearly with line breaks (or numbering) and organize them in the order they appear in the manuscript.

- Quote directly from the text and bold or italicize relevant phrases to illustrate your points

- Include page and line/paragraph numbers for easy reference.

Style/Concision:

- Keep your comments as brief as possible by simply stating the issue and your suggestion for fixing it in a few sentences or less.

Offer feedback that is constructive and professional

Be unbiased and professional.

Although the identities of the authors are sometimes kept anonymous during the review process (this is rare in chemical and biological research), research communities are typically small and you may try to “guess” who the author is based on the methodology used or the writing style. Regardless, it is important to remain unbiased and professional in your review. Do not assume anything about the paper based on your perception of, for example, the author’s status or the impact their results may have on your own research. If you feel that this might be an issue for you, you must inform the editor that there is a conflict of interest and you should not review this manuscript.

Be polite and diplomatic .

Receiving critical feedback, even when constructive, can be difficult and possibly emotional for the authors. Since you are not anonymous to the editors, being unnecessarily harsh in your feedback will reflect badly on you in the end. Use similar language to what you would use when discussing research at a conference, or when talking with your advisor in a meeting. Manuscript peer review is a good way to practice these “soft” skills which are important yet often neglected in the science community.

Additional resources about effective peer reviewing

- American Chemical Society Reviewer Lab

- Nature.com offers a peer review training course for purchase:

- https://masterclasses.nature.com/courses/205

- http://senseaboutscience.org/activities/peer-review-the-nuts-and-bolts/

- http://asapbio.org/six-essential-reads-on-peer-review

This article was written by Mike Orella (MIT Chem E Comm Lab); edited by Mica Smith (MIT Chem E Comm Lab) and Rosy Hosking (Broad Comm Lab)

- Majors & Minors

- About Southwestern

- Library & IT

- Develop Your Career

- Life at Southwestern

- Scholarships/Financial Aid

- Student Organizations

- Study Abroad

- Academic Advising

- Billing & Payments

- mySouthwestern

- Pirate Card

- Registrar & Records

- Resources & Tools

- Safety & Security

- Student Life

- Parents Homepage

- Parent Council

- Rankings & Recognition

- Tactical Plan

- Academic Affairs

- Business Office

- Facilities Management

- Human Resources

- Notable Achievements

- Alumni Home

- Alumni Achievement

- Alumni Calendar

- Alumni Directory

- Class Years

- Local Chapters

- Make a Gift

- SU Ambassadors

Southwestern University announces its 2021–2026 Tactical Plan.

Spurred by her affection for horses, Gabby Guinn ’25 gives back to the community as an intern at the Ride On Center for Kids (ROCK).

Generous gift kicks off fundraising efforts for new athletic complex that will help bring football back to campus for the first time since 1950.

Pirate Athletics launches a new way to elevate the student-athlete experience at Southwestern.

Southwestern’s liberal arts education, wide array of majors and minors, and prime geographic location set students up for future success in the tech industry.

A conversation with Assistant Professor of Sociology Adriana Ponce.

Natalie Davis ’26 awarded with runner-up honors in ASIANetwork’s nationwide essay contest.

Expansive transformation of Mabee Commons honored for outstanding renovation project in national competition.

Lila Milam-Kast ’25 has experienced healing through giving back to her community during an internship at Art Spark Texas.

The Southwestern community will have exclusive access to expanded job resources through Indeed, the world’s #1 job site.

A conversation with Assistant Professor of Chemistry Chelsea Massaro.

Sophia Trifilio ’25, Addison Gifford ’26, and Wafa Bhayani ’25 to continue their education around the world in 2024.

Nineteen students participate in seven thought-provoking projects funded by King Creativity Fund grants.

Jihan Schepmann ’24 will attend UT Southwestern this fall to begin organic chemistry Ph.D. program.

Relive moments from the commencement ceremony for the Southwestern University Class of 2024.

Recent political science graduate earns Critical Language Scholarship to study Russian in Kyrgyzstan and Fulbright grant to teach English in Spain.

Alumni couple challenge fellow Southwestern graduates and friends to match their $5 million commitment before the end of Thrive: The Campaign for Southwestern.

Andrea Abell ’26 and Fernando Cruz-Rivera ’26 each awarded $30,000 for their junior and senior years by The Sumners Foundation.

Alumnus debuts performance to complete masters of music composition program at Texas State University.

Peer Review

Benefits of peer review, how does devoting class time to peer review help student writing.

- Peer review builds student investment in writing and helps students understand the relationship between their writing and their coursework in ways that undergraduates sometimes overlook. It forces students to engage with writing and encourages the self-reflexivity that fosters critical thinking skills. Students become lifelong thinkers and writers who learn to question their own work, values, and engagement instead of simply responding well to a prompt.

- Making the writing process more collaborative through peer review gives students opportunities to learn from one another and to think carefully about the role of writing in the course at hand . The goals of the assignment are clarified. By assessing whether or not individual student examples meet the requirements, students are forced to focus on goals instead of getting distracted entirely by grammar and mechanics or by their own anxiety.

- Studies have shown that even strong writers benefit from the process of peer review : students report that they learn as much or more from identifying and articulating weaknesses in a peer’s paper as from incorporating peers’ feedback into their own work.

- Peer review provides students with contemporary models of disciplinary writing . Because students often learn writing skills in English class, at least in high school, their models for “good writing” might be entirely general or ill-suited to your class. Peer review gives them a communal space to explore writing in the disciplines.

- Peer review allows students to clarify their own ideas as they explain them to classmates and as they formulate questions about their classmates’ writing. This is helpful to writers at all skill levels, in all classes, and at all stages of the writing process.

- Peer review provides professional experience for students having their writing reviewed. Peer review is the process by which professionals in the field publish, it’s how managers and co-workers provide feedback in the workplace, and it’s a skill with practical application.

- Last but not least, peer review minimizes last minute drafting and may cut down on common lower-level writing errors.