Biography of Kate Chopin, American Author and Protofeminist

Missouri Historical Society / public domain

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ThoughtCo_Amanda_Prahl_webOG-48e27b9254914b25a6c16c65da71a460.jpg)

- M.F.A, Dramatic Writing, Arizona State University

- B.A., English Literature, Arizona State University

- B.A., Political Science, Arizona State University

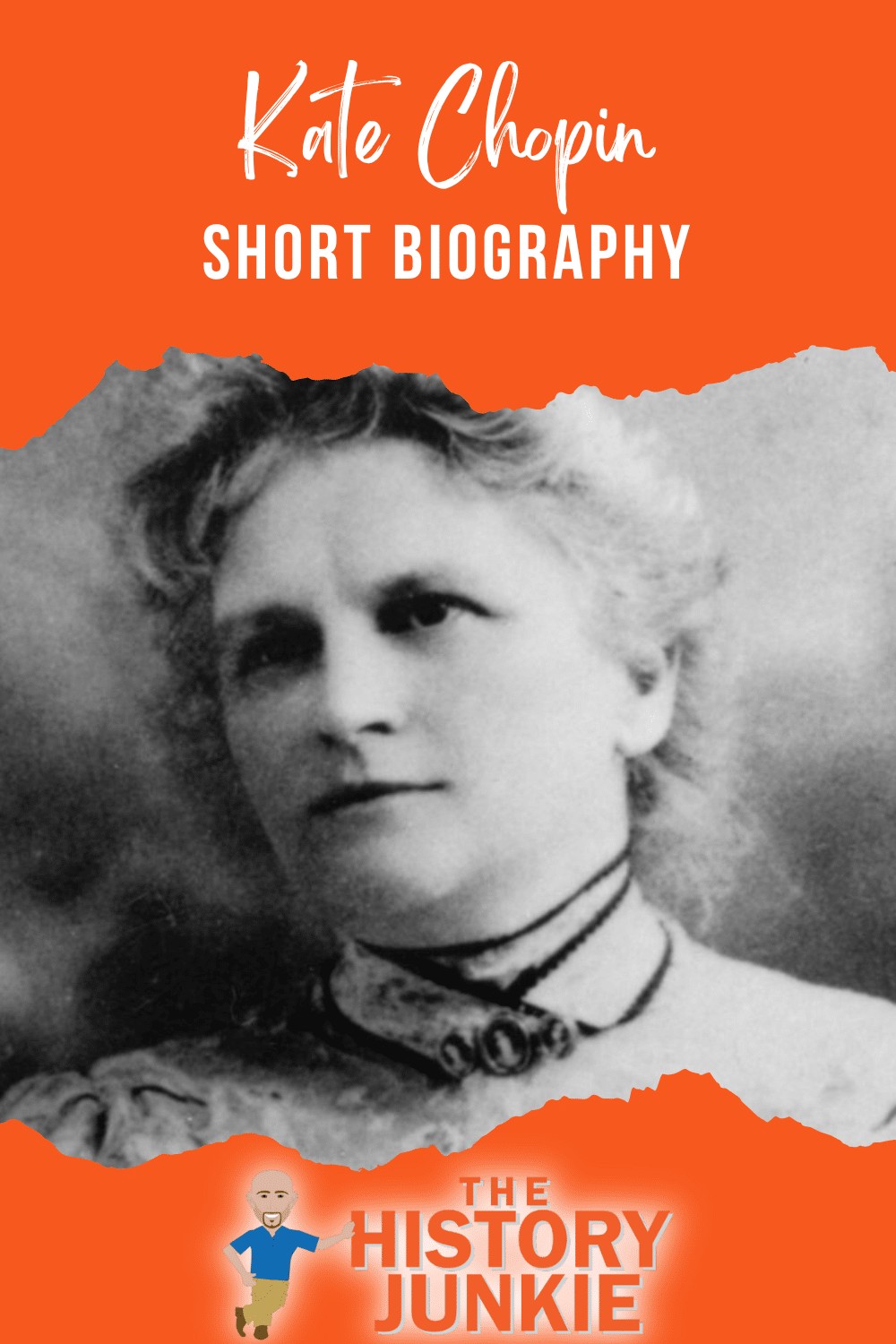

Kate Chopin (born Katherine O'Flaherty; February 8, 1850–August 22, 1904) was an American author whose short stories and novels explored pre- and post-war Southern life. Today, she is considered a pioneer of early feminist literature. She is best known for her novel The Awakening , a depiction of a woman's struggle for selfhood that was immensely controversial during Chopin's lifetime.

Fast Facts: Kate Chopin

- Known For : American author of novels and short stories

- Born : February 8, 1850 in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.

- Parents: Thomas O'Flaherty and Eliza Faris O'Flaherty

- Died : August 22, 1904 in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.

- Education : Sacred Heart Academy (from ages 5-18)

- Selected Works : "Désirée's Baby" (1893), "The Story of an Hour" (1894), "The Storm" (1898), The Awakening (1899)

- Spouse: Oscar Chopin (m. 1870, died 1882)

- Children: Jean Baptiste, Oscar Charles, George Francis, Frederick, Felix Andrew, Lélia

- Notable Quote : “To be an artist includes much; one must possess many gifts—absolute gifts—which have not been acquired by one’s own effort. And, moreover, to succeed, the artist much possess the courageous soul … the brave soul. The soul that dares and defies.”

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Kate Chopin was the third of five children born to Thomas O’Flaherty, a successful businessman who had immigrated from Ireland, and his second wife Eliza Faris, a woman of Creole and French-Canadian descent. Kate had siblings and half-siblings (from her father’s first marriage), but she was the family's only surviving child; her sisters died in infancy and her half-brothers died as young adults.

Raised Roman Catholic, Kate attended Sacred Heart Academy, an institution run by nuns, from age five to her graduation at age eighteen. In 1855, her schooling was interrupted by the death of her father, who was killed in a railway accident when a bridge collapsed. Kate returned home for two years to live with her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, all of whom were widows. Kate was tutored by her great-grandmother, Victoria Verdon Charleville. Charleville was a significant figure in her own right: she was a businesswoman and the first woman in St. Louis to legally separate from her husband .

After two years, Kate was allowed to return to school, where she had the support of her best friend, Kitty Garesche, and her mentor, Mary O’Meara. However, after the Civil War , Garesche and her family were forced to leave St. Louis because they had supported the Confederacy ; this loss left Kate in a state of loneliness.

In June 1870, at age 20, Kate married Oscar Chopin, a cotton merchant five years her senior. The couple moved to New Orleans, a location that influenced much of her late writing. In eight years, between 1871 and 1879, the couple had six children: five sons (Jean Baptiste, Oscar Charles, George Francis, Frederick, and Felix Andrew) and one daughter, Lélia. Their marriage was, by all accounts, a happy one, and Oscar apparently admired his wife’s intelligence and capability.

Widowhood and Depression

By 1879, the family had moved to the rural community of Cloutierville, following the failure of Oscar Chopin’s cotton business . Oscar died of swamp fever three years later, leaving his wife with significant debts of over $42,000 (the equivalent of approximately $1 million today).

Left to support herself and their children, Chopin took over the business. She was rumored to flirt with local businessmen, and allegedly had an affair with a married farmer. Ultimately, she could not salvage the plantation or the general store, and in 1884, she sold the businesses and moved back to St. Louis with some financial help from her mother.

Soon after Chopin settled back in St. Louis, her mother died suddenly. Chopin fell into a depression. Her obstetrician and family friend, Dr. Frederick Kolbenheyer, was the one to suggest writing as a form of therapy, as well as a possible source of income. By 1889, Chopin had taken the suggestion and thus began her writing career.

Scribe of Short Stories (1890-1899)

- "Beyond the Bayou" (1891)

- "A No-Account Creole" (1891)

- "At the 'Cadian Ball" (1892)

- Bayou Folk (1894)

- "The Locket" (1894)

- "The Story of an Hour" (1894)

- "Lilacs" (1894)

- "A Respectable Woman" (1894)

- "Madame Celestin's Divorce" (1894)

- "Désirée's Baby" (1895)

- "Athenaise" (1896)

- A Night in Acadie (1897)

- "A Pair of Silk Stockings" (1897)

- "The Storm" (1898)

Chopin’s first published work was a short story printed in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch . Her early novel, At Fault , was rejected by an editor, so Chopin printed copies privately at her own expense. In her early work, Chopin addressed themes and experiences with which she was familiar: the North American 19-century Black activist movement, the complexities of the Civil War, the stirrings of feminism, and more.

Chopin's short stories included successes such as "A Point at Issue!", "A No-Account Creole", and "Beyond the Bayou.” Her work was published both in local publications and, eventually, national periodicals including the New York Times , The Atlantic , and Vogue . She also wrote non-fiction articles for local and national publications, but her focus remained on works of fiction.

During this era, “local color” pieces—works that featured folk tales, Southern dialect, and regional experiences—were gaining popularity. Chopin’s short stories were typically considered part of that movement rather than evaluated on their literary merits.

"Désirée's Baby,” published in 1893, explored the topics of racial injustice and interracial relationships (called "miscegenation" at the time) in French Creole Louisiana. The story highlighted the racism of the era, when possessing any African ancestry meant facing discrimination and danger from law and society. At the time Chopin was writing, this topic was generally kept out of public discourse; the story is an early example of her unflinching depictions of controversial topics of her day.

Thirteen stories, including “Madame Celestin’s Divorce,” were published in 1893. The following year, “ The Story of an Hour ,” about a newly widowed woman’s emotions, was first published in Vogue ; it went on to become one of Chopin's most famous short stories. Later that year, Bayou Folk , a collection of 23 short stories, was published. Chopin’s short stories, of which there were around a hundred, were generally well-received during her lifetime, especially when compared with her novels.

The Awakening and Critical Frustrations (1899-1904)

- The Awakening (1899)

- "The Gentleman from New Orleans" (1900)

- "A Vocation and a Voice" (1902)

In 1899, Chopin published the novel The Awakening , which would become her best-known work. The novel explores the struggle to formulate an independent identity as a woman in the late 19th century.

At the time of its publication, The Awakening was widely criticized and even censored for its exploration of female sexuality and questioning of restrictive gender norms. The St. Louis Republic called the novel "poison." Other critics praised the writing but condemned the novel on moral grounds, such as The Nation , which suggested that Chopin had wasted her talents and disappointed readers by writing about such “unpleasantness."

Following The Awakening ’s critical trouncing, Chopin’s next novel was canceled, and she returned to writing short stories. Chopin was discouraged by the negative reviews and never entirely recovered. The novel itself faded into obscurity and eventually went out of print. (Decades later, the very qualities that offended so many 19th century readers made The Awakening a feminist classic when it was rediscovered in the 1970s.)

Following The Awakening , Chopin continued to publish a few more short stories, but they were not entirely successful. She lived off of her investments and the inheritance left to her by her mother. Her publication of The Awakening damaged her social standing, and she found herself quite lonely once again.

Literary Styles and Themes

Chopin was raised in a largely female environment during an era of great change in America. These influences were evident in her works. Chopin did not identify as a feminist or suffragist, but her work is considered "protofeminist" because it took individual women seriously as human beings and complex, three-dimensional characters. In her time, women were often portrayed as two-dimensional figures with few (if any) desires outside of marriage and motherhood. Chopin's depictions of women struggling for independence and self-realization were unusual and groundbreaking.

Over time, Chopin’s work demonstrated different forms of female resistance to patriarchal myths , taking on different angles as themes in her work. Scholar Martha Cutter, for instance, traces the evolution of her characters’ resistance and the reactions they get from others within the world of the story. In some of Chopin’s earlier short stories, she presents the reader with women who overly resist patriarchal structures and are disbelieved or dismissed as crazy. In later stories, Chopin’s characters evolve: they adapt quieter, covert resistance strategies to achieve feminist ends without being immediately noticed and dismissed.

Race also played a major thematic role in Chopin’s works. Growing up in the era of enslavement and the Civil War, Chopin observed the role of race and the consequences of that institution and racism. Topics like miscegenation were often kept out of public discourse, but Chopin put her observations of racial inequality in her stories, such as "Désirée's Baby."

Chopin wrote in a naturalistic style and cited the influence of French writer Guy de Maupassant . Her stories were not exactly autobiographical, but they were drawn from her sharp observations of the people, places, and ideas that surrounded her. Because of the immense influence of her surroundings on her work—especially her observations of pre- and post-war Southern society—Chopin was sometimes pigeonholed as a regional writer.

On August 20, 1904, Chopin suffered a brain hemorrhage and collapsed during a trip to the St. Louis World’s Fair. She died two days later on August 22, at the age of 54. Chopin was buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, where her grave is marked with a simple stone with her name and dates of birth and death.

Although Chopin was criticized during her lifetime, she eventually became recognized as a leading early feminist writer. Her work was rediscovered during the 1970s , when scholars evaluated her work from a feminist perspective, noting Chopin's characters' resistance to patriarchal structures.

Chopin is also occasionally categorized alongside Emily Dickinson and Louisa May Alcott, who also wrote complex stories of women attempting to achieve fulfillment and self-understanding while pushing back against societal expectations. These characterizations of women who sought independence were uncommon at the time and thus represented a new frontier of women's writing.

Today, Chopin's work—particularly The Awakening —is frequently taught in American literature classes. The Awakening was also loosely adapted into a 1991 film called Grand Isle. In 1999, a documentary called Kate Chopin: A Reawakening told the story of Chopin's life and work. Chopin herself been featured less frequently in mainstream culture than other authors of her era, but her influence on the history of literature is undeniable. Her groundbreaking work paved the way for future feminist authors to explore topics of women's selfhood, oppression, and inner lives.

- Cutter, Martha. "Losing the Battle but Winning the War: Resistance to Patriarchal Discourse in Kate Chopin's Short Fiction". Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers . 68.

- Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State UP, 1985.

- Toth, Emily. Kate Chopin . William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1990.

- Walker, Nancy. Kate Chopin: A Literary Life . Palgrave Publishers, 2001.

- “$42,000 in 1879 → 2019 | Inflation Calculator.” U.S. Official Inflation Data, Alioth Finance, 13 Sep. 2019, https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1879?amount=42000.

- Kate Chopin's 'The Storm': Quick Summary and Analysis

- Famous Fictional Heroines

- Outstanding Women Writers of the 20th Century

- Frances Dana Gage

- Kate Chopin's 'The Awakening' of Edna Pontellier

- Biography of George Sand

- Biography of Valerie Solanas, Radical Feminist Author

- Banned Books by African-American Authors

- "The Story of an Hour" Characters

- Biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Poet and Activist

- Analysis of "The Story of an Hour" by Kate Chopin

- 'The Story of an Hour' Questions for Study and Discussion

- Biography of Djuna Barnes, American Artist, Journalist, and Author

- 'The Awakening' Quotes

- Analysis of 'The Yellow Wallpaper' by C. Perkins Gilman

- Biography of Marge Piercy, Feminist Novelist and Poet

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Kate Chopin

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Official Site of The Kate Chopin International Society

- Kate Chopin - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Kate Chopin (born Feb. 8, 1851, St. Louis, Mo., U.S.—died Aug. 22, 1904, St. Louis) was an American novelist and short-story writer known as an interpreter of New Orleans culture . There was a revival of interest in Chopin in the late 20th century because her concerns about the freedom of women foreshadowed later feminist literary themes.

Born to a prominent St. Louis family, Katherine O’Flaherty read widely as a girl. In June 1870 she married Oscar Chopin, with whom she lived in his native New Orleans, Louisiana , and later on a plantation near Cloutiersville, Louisiana, until his death in 1882. After he died she began to write about the Creole and Cajun people she had observed in the South. Her first novel , At Fault (1890), was undistinguished, but she was later acclaimed for her finely crafted short stories, of which she wrote more than 100. Two of these stories, “Désirée’s Baby” and “Madame Celestin’s Divorce,” continue to be widely anthologized.

In 1899 Chopin published The Awakening , a realistic novel about the sexual and artistic awakening of a young wife and mother who abandons her family and eventually commits suicide. This work was roundly condemned in its time because of its sexual frankness and its portrayal of an interracial marriage and went out of print for more than 50 years. When it was rediscovered in the 1950s, critics marveled at the beauty of its writing and its modern sensibility.

Chopin’s work has been categorized within the “ local colour ” genre . Her stories were collected in Bayou Folk (1894) and A Night in Acadie (1897). The Complete Works of Kate Chopin , edited by Per Seyersted, appeared in 1969.

Kate Chopin

(1850-1904)

Kate Chopin was born on February 8, 1850, in St. Louis, Missouri. She began to write after her husband's death. Among her more than 100 short stories are "Désirée's Baby" and "Madame Celestin's Divorce." The Awakening (1899), a realistic novel about the sexual and artistic awakening of a young mother who abandons her family, was initially condemned for its sexual frankness but was later acclaimed. Chopin died in St. Louis, Missouri, on August 22, 1904.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Kate Chopin

- Birth Year: 1850

- Birth date: February 8, 1850

- Birth State: Missouri

- Birth City: St. Louis

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Female

- Best Known For: Short-story writer and novelist Kate Chopin wrote The Awakening, a novel about a young mother who abandons her family, initially condemned but later acclaimed.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Aquarius

- Occupations

- Death Year: 1904

- Death date: August 22, 1904

- Death State: Missouri

- Death City: St. Louis

- Death Country: United States

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Kate Chopin Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/kate-chopin

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 16, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous Authors & Writers

Alice Munro

Agatha Christie

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

9 Surprising Facts About Truman Capote

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Meet Stand-Up Comedy Pioneer Charles Farrar Browne

Francis Scott Key

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

|

was inspired by a true story of a New Orleans woman who was infamous in the French Quarter. , was published in 1890, followed by two collections of her short stories, in 1894 and in 1897. was published in 1899, and by then she was well known as both a local colorist and a woman writer, and had published over one hundred stories, essays, and sketches in literary magazines. . The content and message of caused an uproar and Chopin was denied admission into the St. Louis Fine Art Club based on its publication. She was terribly hurt by the reaction to the book and in the remaining five years of her life she wrote only a few short stories, and only a small number of those were published. Like Edna, she paid the price for defying societal rules, and as Lazar Ziff explains, she "learned that her society would not tolerate her questionings. Her tortured silence as the new century arrived was a loss to American letters of the order of the untimely deaths of Crane and Norris. She was alive when the twentieth century began, but she had been struck mute by a society fearful in the face of an uncertain dawn" ( ). remember that it is a , "a tale of a young woman who struggles to realize herself - and her artistic ability" and remember that Chopin, as well as Edna, was on a quest for artistic acceptance. That quest ended in an abrupt and frustrated manner when she died of a cerebral hemorrhage on August 22 1904. by Emily Toth, by Mary Papke, and by Per Seyersted. Below is a chronology of her life and work taken from , xii-xv)

and his daughter Kate, becomes a talented artist.

in the depiction of Mrs. Highcamp's daughter. in 1893. Publishes more stories in and . ) in January, introducing the character of Gouvernail, who reappears in Houghton Mifflin publishes in March, and Chopin becomes nationaly known as a short story writer. , a second volume of short stories is published by Way and Williams of Chicago. . published by Herbert S. Stone and Company on April 22.

] site.

|

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

- Time Periods

Kate Chopin (1850–1904)

![Kate Chopin, circa 1890s. [Prints and Photographs Collection, N11858, Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis] Kate Chopin portrait](https://missouriencyclopedia.org/sites/default/files/styles/article_header_image/public/2020-02/KateChopin_photo.jpg?itok=re7hROWz)

Kate Chopin began and ended her life in St. Louis, with an interlude as a young wife and mother in New Orleans and rural Louisiana. Her stories of Creole life in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, established her as a talented local-color writer in the southern tradition. Some of her lesser-known stories explored the complexities of the emerging urban culture of the late nineteenth century. The Awakening , her second novel, won her a place in history, both as a writer and as a critic of women’s roles in the family and the community. Her early life and her mature experience in St. Louis influenced her perception of the human condition. A community of writers and intellectuals in St. Louis supported and shaped her literary life. Louisiana provided the setting for much of her fiction, but St. Louis provided the environment in which she created an important body of work.

Biographer Emily Toth has convincingly argued that Catherine O’Flaherty was born on February 8, 1850, not 1851, as previous biographers believed. Her father, Thomas O’Flaherty, was a successful Irish-born businessman with a son from a previous marriage. Her mother, Eliza Faris O’Flaherty, was the daughter of a French family with a history dating back to the founding of St. Louis. A great-grandmother, Victoire Verdun Charleville, shared stories of Kate’s Creole ancestors, which influenced Chopin’s later Creole tales. The O’Flaherty family owned slaves and occupied a handsome Greek Revival–style home. A neighbor, Kitty Garesche, became a schoolmate and lifelong friend. Kitty and Kate attended Sacred Heart Academy, a convent school. Kate left school for two years after her father’s death in November 1855 in the railroad disaster on the Gasconade Bridge that killed thirty prominent St. Louis citizens. Kate’s half brother, George, and her beloved great-grandmother both passed away in 1863. While St. Louis seethed with divisions during the Civil War period, Kate O’ Flaherty returned to school and graduated from the Sacred Heart Academy in 1868. As a student she read widely and began writing diary entries, poems, and short stories.

After her marriage to Oscar Chopin in 1870, Kate Chopin left St. Louis and began raising a family in Louisiana. Apparently, the couple spent several years in New Orleans before settling in Cloutierville, in Natchitoches Parish, where Oscar Chopin’s family had long owned a plantation. There they lived in a spacious timber-frame home with front and rear verandas. The landscape and the people of central Louisiana deeply impressed Kate Chopin and inspired many of her later published stories. Her Creole ancestry helped her to understand and sympathize with her Louisiana neighbors. Scholars have speculated about the extent to which the author’s own married life resembled the sad marriage in The Awakening , but there is no definitive answer to this question. Unlike the book’s character Leonce Pontellier, Oscar Chopin suffered recurrent fevers, probably aggravated by the moist climate and lack of medical services in rural Louisiana. In December 1882 he died.

A widow and the mother of six children, Kate Chopin returned to St. Louis in 1884 and there began her writing career. In 1889 the Chicago magazine America introduced her to the public by printing her poem “If It Might Be.” A local editor accepted her first published story that same year for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch . Other local journals, including William Marion Reedy ’s St. Louis Mirror and the St. Louis Criterion , carried her stories and essays. At her own expense she published her first novel, At Fault , in 1890. National magazines, including Vogue and Atlantic , carried her stories in the 1890s. Critics warmly praised the collection of Creole tales published as Bayou Folk in 1894. The stories in Bayou Folk and A Night in Acadie , published in 1897, established Chopin as a local-color writer with a gift for characterization.

Chopin’s Creole stories found a ready audience, partly because they did not challenge accepted images of southern life. In the bayou landscape of these stories, husbands could be cruel and wives could lead complex emotional lives, but they remained within social bonds defined by custom. Racial and class divisions limited interaction. In her famous story “Desiree’s Baby,” Chopin confronted the difficult issue of race, but failed to transcend common fears and stereotypes. Armand Aubigny accuses his wife, Desiree, of being black and bearing him a black child. Desiree, distraught, runs away through fields where black workers picked cotton. Unable to live with his rejection, she disappears, presumably ending her own life. Armand then discovers that his forebears, not Desiree’s, were black. Chopin presented the story as tragic irony, but did not clearly reject the racial ideology that caused Desiree’s death.

At Fault , Chopin’s first novel, took a more critical look at American life in the nineteenth century. Fanny Hosmer, an unattractive female character, exemplifies the alienation and futility of some middleclass women’s existence. Fanny is bored, shallow, and hopelessly alcoholic. Her husband, David, flees from her and her troubles to the world of Thérèse La Firme, a Creole widow in rural Louisiana. In contrast to the hard reality of St. Louis, the world of the bayou seems dreamlike, idyllic. Fanny, who represents the complexities of the modern city, simplifies matters for David and Thérèse by drowning in a flood. The bayou romance softens the novel. Nevertheless, the book offers a gritty portrait of an indolent middle-class woman, adrift in the city. Publishers showed no interest. Critics generally disliked or dismissed the self-published book.

Chopin spent her most creative years in the heart of a modern industrial city. In 1886, the year after her mother’s death, Chopin moved to a house on Morgan Street (now Delmar). Her neighbors included artists, musicians, tradesmen, and managers—people on the way up or down in a whirl of capitalistic enterprise. The David and Fanny Hosmers of the world passed by her doorstep. Robert E. Lee Gibson, a poet and the head clerk of the St. Louis Insane Asylum, became her ardent admirer. Logan Uriah Reavis , who wrote books promoting St. Louis as the future capital of the United States, wandered the streets in baggy clothes and dirty shirts. Chopin could ride the streetcar to every corner of her city or sit by her window and almost literally watch the city grow.

In stories with St. Louis settings, the author revealed a keen understanding of urban pretensions and reality. The central character in “A Pair of Silk Stockings” suddenly finds fifteen dollars and squanders it on all the temptations of St. Louis in the 1890s: shopping in a department store, dining in a restaurant, attending a matinee, and riding a cable car for miles. She enjoys her guilty pleasures, but her life seems purposeless. The title character in ‘‘The Blind Man” ambles through the city selling pencils. As he turns a corner, a speeding streetcar screeches to a halt. A prominent businessman who fails to see the car coming from the other direction dies under its wheels. The blind man wanders on, like the city itself, unaffected by the tragedy.

In “Miss McEnders,” an affluent woman does charity work among poor factory laborers, but responds coldly to her dressmaker, who reveals that she had an illegitimate child. McEnders suffers a crisis of conscience when she learns some hard truths about the questionable source of her father’s wealth. In these stories with urban settings, Chopin questions the materialism and moral blindness of modern society.

Chopin’s second novel, The Awakening , published in 1899, portrays the inner life of a woman who rejects her role as a businessman’s ornamental wife, but fails to define a place for herself in a cruelly judgmental community. Edna Pontellier’s closest friend is a woman who glories in motherhood, devoting all her energies to raising her children. Another woman friend lives the solitary life of a dedicated musician, rejecting companionship and pouring all her emotions into her art. Edna admires each of these women, but she cannot be like them. Leonce, her husband, regards her as a part of his household, one of his possessions, but not as a woman at the center of his life. Robert, the man she had loved, draws away from her out of fear and conventionality. A third man, who becomes her lover, offers her no fulfillment. A physician in the novel hints that he has dealt with other troubled, rebellious women like Edna. But Edna fails to connect with any of these possibly sympathetic souls. She possesses the courage to defy society’s rules, but she is unable to find a way to live in opposition to them. Feeling completely alone and finding no other path to liberation, Edna commits suicide. The novel challenged conventional values and shocked many critics.

Scathing reviews, condemning the novel as immoral, gave The Awakening the aura of a banned book. In fact, the book may never have been banned. Historians perpetuated the story, based on oral testimony, that the St. Louis Mercantile Library removed The Awakening from circulation. But Per Seyersted, an important Chopin biographer, questioned the story of the book’s banning. In twenty years of research, he found no documentation of the incident. Frequent retelling of the book-banning anecdote created an image of Chopin as a lonely iconoclast, rejected by her St. Louis neighbors—an image that distorted the truth.

Although she challenged accepted mores, Chopin was never as lonely as her heroine Edna Pontellier. Throughout her life she had numerous friends and supporters in her native city. Her connections with her mother’s family, her girlhood associates, and her own children remained strong throughout her life. Dr. Frederick Kohlbenheyer, her personal physician and intellectual companion, read many of her manuscripts. Kohlbenheyer had connections to the St. Louis literary establishment through an association with publisher Joseph Pulitzer . John A. Dillon , editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch , supported women’s rights and encouraged Chopin’s literary efforts. William Marion Reedy, the eccentric editor of the St. Louis Mirror , befriended the author and publicly praised her talent. The Mirror ’s reviewer vilified The Awakening , but a circle of close friends remained her champions to the end of her life. Sue V. Moore, a local editor, staunchly rebuffed the critics and came to the author’s defense. Local editors continued to accept her writings. Kate Chopin became a charter member of the Wednesday Club in 1890 and continued to associate with the intelligent and affluent women who made up its membership. She read “Ti Demon,” a Creole story, at a club meeting in November 1899, months after critics expressed shock at the content of The Awakening .

Sympathetic scholars have portrayed Kate Chopin in her final years as a tragic figure who failed to draw parallels between herself and Edna Pontellier, who chose death over life in a society that refused to let her grow. While Chopin produced no book-length work after The Awakening , she continued writing, publishing, and participating in the social life of her home city. The St. Louis Mirror , the St. Louis Post-Dispatch , and the St. Louis Republic published several of her stories and articles between 1899 and 1904. National magazines such as Vogue and Youth’s Companion continued to print her work.

Chopin’s death coincided with a celebration of progress, the St. Louis World’s Fair . By all accounts, she had great enthusiasm for the fair, more properly known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. She bought a season ticket and traveled the short distance from her home to the fairgrounds nearly every day. The fair offered a spectacle of electric lights, fantastic inventions, and artificial waterways. Bands played ragtime , a new music that challenged traditional rhythms and echoed the rapid cadence of city life. On August 20, 1904, a particularly hot day, Chopin returned from the fair and later suffered a hemorrhage of the brain. Two days later, with her children at her bedside, she died.

In the year of her death, St. Louisan Alexander De Menil praised Bayou Folk , slighted her novels, and defined Chopin as a Creole writer. For several decades this assessment of her work prevailed. In 1923 Fred Lewis Pattee identified her as a master of the American short story. Daniel Rankin, who published a full-length biography of Chopin in 1932, unearthed important information about her early life. Scholarly interest remained limited until the 1960s, when Larzer Ziff defined Chopin as an American realist with the stature of Theodore Dreiser. The Norwegian scholar Per Seyersted collected and published The Complete Works of Kate Chopin in 1969. His important biography of the author appeared in the same year. By the 1970s students of women’s history, as well as American literary history, flocked to libraries to study Chopin’s fiction. Dissertations and articles proliferated as the focus of critical attention shifted from her short stories to her 1899 novel. In the 1980s and 1990s, The Awakening became a popular text in college literature, women’s studies, and American studies classes.

Chopin ultimately gained fame as a realist rather than a local-color writer, a novelist rather than a short-story writer, a modernist rather than a teller of sentimental tales. She often chose rural settings for her fiction, but she lived in the city most of her life. The troubles of Edna Pontellier in The Awakening were the troubles of an affluent urban woman who spent her vacations on Grand Isle but lived in New Orleans. Her empty life resulted partially from traditional definitions of women’s roles, but mostly from the fact that those definitions no longer had meaning in urban America at the end of the nineteenth century. Chopin observed this emerging society in St. Louis in the 1880s and 1890s, the most creative years of her life. St. Louis influenced her thinking and nurtured her talent, while local editors, publishers, mentors, and friends encouraged her efforts.

Bonnie Stepenoff

Bonnie Stepenoff is professor emerita of history at Southeast Missouri State University.

Dictionary of Missouri Biography

- Further Reading

Chopin, Kate. The Complete Works of Kate Chopin . 2 vols. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Koloski, Bernard, ed. Awakenings: The Story of the Kate Chopin Revival . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Rankin, Daniel. Kate Chopin and Her Creole Stories . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1932.

Seyersted, Per. Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1969.

Skaggs, Peggy. Kate Chopin . Boston: G. K. Hall, 1985.

Toth, Emily. Kate Chopin . New York: William Morrow, 1990.

Walker, Nancy H. Kate Chopin: A Literary Life . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

Ziff, Larzer. The American 1890s: Life and Times of a Lost Generation . New York: Viking, 1966.

Published September 6, 2018; Last updated December 22, 2023

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

- News and Announcements

- Events, Workshops, and Public Programs

- Publications and Scholarship

- National History Day in Missouri

Copyright © 2020–2021 State Historical Society of Missouri. All rights reserved.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Native Americans

- Age of Exploration

- Revolutionary War

- Mexican-American War

- War of 1812

- World War 1

- World War 2

- Family Trees

- Explorers and Pirates

Kate Chopin's Short Biography

Published: Aug 31, 2023 · Modified: Oct 19, 2023 by Russell Yost · This post may contain affiliate links ·

Kate Chopin was an American author of short stories and novels. She is best known for her stories about the lives of women in the American South, which often challenged the conventions of the time.

Chopin was born in St. Louis, Missouri, to Oscar Chopin, a successful businessman, and Eliza Faris Chopin. She was the eldest of six children. Chopin's family was of French descent, and she grew up speaking French as her first language.

Chopin was educated at the Sacred Heart Academy in St. Louis. She then attended the St. Louis Female Academy, where she studied music and art. In 1869, she married Oscar Chopin, a cotton planter from New Orleans. The couple had six children together.

In 1879, Oscar Chopin died suddenly, leaving Kate Chopin a widow with six young children to support. She moved back to St. Louis with her children and began writing short stories. Her first story, "Athenais," was published in 1890.

Chopin's stories were often about the lives of women in the American South. She wrote about their struggles with poverty, loneliness, and unfulfilled dreams. Her stories were also known for their frankness about sexuality.

Chopin's most famous story is "The Story of an Hour" (1894). The story tells the tale of a woman who is overjoyed to learn of her husband's death, only to die of a heart attack shortly after. The story was considered controversial at the time for its exploration of female desire and independence.

Chopin published two novels, The Awakening (1899) and The Storm (1900). The Awakening is considered her masterpiece. The novel tells the story of a woman who rebels against the conventions of her time and pursues her own happiness.

Chopin's work was not well-received by critics at the time. They accused her of being too daring and too honest about the lives of women.

However, her work has since been rediscovered and appreciated by modern critics. She is now considered one of the most important American authors of the late 19th century.

Chopin died of breast cancer in 1904 at the age of 53. She is buried in St. Louis, Missouri.

Kate Chopin

A short biography of kate chopin, kate chopin’s writing style.

She made stylistic and thematic experiments in her works. Her difference from Maupassant lies in her objective psychological realism. Her focus is more on the character instead of the plot.

Tradition and Female Talent: Solitary Thoughts

Social fiction.

In her fictional work, Kate Chopin has encompassed nineteenth-century South and contemporary life there. She represents a period of transmogrification. There is a shift from slavery to industrialization and economic assimilation. This newly transformed society was based on a class system, and in every class, women had subordinate roles. Kate has addressed the myths of nostalgia and progress.

Semiotic Subversion

Desire and the descent of man.

She has resisted the struggle between men for the possession of women and the passive, modest role of women. She has also challenged the superiority of men over women. She has depicted women in her works who are not submissive; they select according to their own choice. They select those whom they desire and on the basis of other reasons.

Ironist of Realism

Works of kate chopin, short stories.

Analysis Pages

- Character Analysis

- Foreshadowing

- Historical Context

- Literary Devices

- Quote Analysis

Kate Chopin Biography

Kate Chopin was born Katherine O’Flaherty on February 8, 1851, in St. Louis, Missouri, into a socially prominent family with roots in the French past of both St. Louis and New Orleans. Her father, Thomas O’Flaherty, an immigrant from Ireland, had lived in New York and Illinois before settling in St. Louis, where he prospered as the owner of a commission house. In 1839, he married into a well-known Creole family, members of the city’s social elite, but his wife died in childbirth only a year later. In 1844, he married Eliza Faris, merely fifteen years old but, according to French custom, eligible for marriage. Faris was the daughter of a Huguenot man who had migrated from Virginia and a woman who was descended from the Charlevilles, among the earliest French settlers in America.

Kate was one of three children born to her parents and the only one to live to mature years. In 1855, tragedy struck the O’Flaherty family when her father, now a director of the Pacific Railroad, was killed in a train wreck; thereafter, Kate lived in a house of many widows—her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother Charleville. In 1860, she entered the St. Louis Academy of the Sacred Heart, a Catholic institution where French history, language, and culture were stressed—as they were, also, in her own household. Such an early absorption in French culture would eventually influence Chopin’s own writing, an adaptation in some ways of French forms to American themes.

Chopin graduated from the Academy of the Sacred Heart in 1868, and two years later she was introduced to St. Louis society, becoming one of its ornaments, a vivacious and attractive girl known for her cleverness and talents as a storyteller. The following year, she made a trip to New Orleans, and it was there that she met Oscar Chopin, whom she married in 1871. After a three-month honeymoon in Germany, Switzerland, and France, the couple moved to New Orleans, where Chopin’s husband was a cotton factor (a businessman who financed the raising of cotton and transacted its sale). Oscar Chopin prospered at first, but in 1878 and 1879, the period of the great “Yellow Jack” epidemic and of disastrously poor harvests, he suffered reverses. The Chopin family then went to live in rural Louisiana, where, at Cloutierville, Oscar Chopin managed some small plantations he owned.

By all accounts, the Chopin marriage was an unusually happy one, and in time Kate became the mother of six children. This period in her life ended, however, in 1883 with the sudden death, from swamp fever, of her husband. A widow at thirty, Chopin remained at Cloutierville for a year, overseeing her husband’s property, and then moved to St. Louis, where she remained for the rest of her life. She began to write in 1888, while still rearing her children, and in the following year she made her first appearance in print. As her writing shows, her marriage to Oscar Chopin proved to be much more than an “episode” in her life, for it is from this period in New Orleans and Natchitoches Parish that she drew her best literary material and her strongest inspiration. She knew this area personally, and yet as an “outsider” she was also able to observe it with the freshness of detachment.

Considering the fact that she had only begun to have her stories published in 1889, it is remarkable that Chopin should already have written and published her first novel, At Fault , by 1890. The novel is apprenticeship work and was published by a St. Louis company at her own expense, but it does show a sense of form. She then wrote a second novel, “Young Dr. Gosse,” which in 1891 she sent out to a number of publishers, all of whom refused it, and which she later destroyed. After finishing this second novel, she concentrated on the shorter forms of fiction, writing forty stories, sketches, and vignettes during the next three years. By 1894, her stories began to find a reception in eastern magazines, notably in Vogue , The Atlantic...

(The entire page is 1,202 words.)

Owl Eyes subscribers get unlimited access to our expert annotations, analyses, and study guides on your favorite texts. Master the classics for less than $5/month!

🔒 Become a member to unlock this study guide »

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Kate Chopin : a critical biography

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Reprint of the ed. published (1969) by Universitetsforlaget, Oslo, and Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, in the series: Publications of the American Institute, University of Oslo. "...no changes have been made in this reprint of my 1969 book."--P. [7] Includes bibliography (p. [230]-237) and index.

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

945 Previews

15 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Tracey.Gutierres on October 19, 2011

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

KateChopin.org

The kate chopin international society, frequently asked questions about kate chopin, many of the questions and answers on this page also appear at other places on this site. you can follow links to those places, where you’ll find related information..

By the Editors of KateChopin.org

Questions about Chopin’s personal life About Chopin’s reputation and popularity About Chopin’s French connections and expressions Chopin’s attitude toward race and death Chopin’s style, influences, and translations Copyright protection of Chopin’s work A biographical question with a recent answer New Questions about this website

Questions about The Awakening , At Fault , and Kate Chopin’s short stories

Questions about Chopin’s personal life:

Q: What was Kate Chopin’s name before she was married?

A: She was baptized Catherine O’Flaherty, although everyone called her Kate. Her father was Irish.

Q: How do you pronounce “Chopin”?

A: In the French way, like that of the composer, Frédéric Chopin–in English, something like SHOW-PAN. As written in the International Phonetic Alphabet: / ˈ ʃ oʊ p æ n /.

Q: An American literature professor I met told me that Chopin Anglicized her name and it should be pronounced “CHOP-in,” rather than like the French composer. I haven’t been able to confirm this. Is that professor right?

A; No. Kate Chopin’s fiction is read today around the world in English and in translations into twenty-some other languages, so “Chopin” and the names of the characters in her stories are no doubt pronounced in lots of different ways. But claiming that Kate Chopin herself Anglicized her name is a different matter. Here is what some Chopin scholars and Chopin’s descendants have to say.

Emily Toth , Kate Chopin’s biographer: “I would defer to the family on this one for the final word. I’ve never heard any pronunciation other than SHOW-PAN—except from a few English professors (a devilish breed! :)) who somehow think they know better. But Dave Chopin [Kate Chopin’s grandson] for one, assured me that it is/was SHOW-PAN.

“There would be no incentive for Chopin to Anglicize her name, as she lived among French speakers (in Louisiana) and many people who were French or of French descent in St. Louis. Besides, who would choose a ridiculous pronunciation that sounds like chopping wood, when you’ve got a beautiful, flowing French word?

“I would add—Trust primary sources, and don’t trust random English professors.”

Barbara Ewell , Kate Chopin scholar: “I’m with Emily on this: SHOW-PAN remains the pronunciation of the name whenever I’ve encountered it in New Orleans. But the family should have the last say.”

Gerri Chopin Wendel , one of Kate Chopin’s great-granddaughters (a daughter of David Chopin ): “I can’t imagine it ever being pronounced any way other than SHOW-PAN, which we have always known. The thought of it being Anglicized is horrifying!”

Annette Chopin Lare , another of Kate Chopin’s great-granddaughters (also a daughter of David Chopin ): “Emily is correct. The name has always been pronounced in the French way. It’s pronounced SHOW-PAN. We grew up hearing our parents constantly correct people and have spent the better part of our lives doing the same. That said, anyone familiar with classical music always got it right. This wasn’t just in our immediate family. Aunts, uncles, cousins always pronounced it in the French way.”

Tom Bonner , Kate Chopin scholar: “I’m with Emily and the family. Perhaps the English professor has a hearing issue.”

Finally, Susie Chopin , still another of Kate Chopin’s great-granddaughters (and also a daughter of David Chopin ): “When anyone asks about the pronunciation of my name, my standard answer is ‘It looks like CHOP-IN, but it’s pronounced SHOW-PAN.’ Yet our name has been mispronounced all our lives and you have to learn not to sweat the small stuff.

“Call me CHOP-IN, call me CHO-PIN, call me SHOW-PIN. But never, ever tell me that my own name is really not pronounced SHOW-PAN. Thems be fightin’ words, folks.”

Q: Was Kate Chopin French?

No, she was American. But her mother’s family was of French descent. And she married a man whose father was French.

Q: When was Kate Chopin born? Some internet sites say 1851 and others 1850.

A: Her tombstone says 1851, but thirty years ago a French scholar revealed that the United States census and her baptismal certificate (no birth certificate exists) show that Chopin was born on February 8, 1850. The United States Library of Congress in September, 2009, accepted the corrected date, but some printed sources and web sites still give her birth date as 1851.

Q: Was Kate born a Chopin or is that her married name?

A: She was born Catherine O’Flaherty. You can read a brief description of her life on our Biography page .

Q: The Kate Chopin biography I’m reading spells Catherine with a “K.” Why is there this difference?

A: There’s not much of a difference. “Catherine” and “Katherine” would likely be pronounced the same in English, but “Kate” is what Chopin was called by her family and friends. It’s common in the States and other English-speaking places for a woman named Catherine to be referred to with the one-syllable Kate rather than the longer Catherine. Because “Cate” would be puzzling to most English readers, we have “Kate” — and therefore, in the longer form, “Katherine.”

Q: Was Kate Chopin’s husband related, however distantly, to Frédéric Chopin the composer?

A: Apparently not. Kate Chopin has had three biographers, but none of them has discovered a family connection, and a French scholar in Paris has not found a link.

Q: I was wondering where in Missouri Kate Chopin was born and where in Missouri she lived while she wrote her fiction.

A: According to Emily Toth in her biography Unveiling Kate Chopin , Catherine O’Flaherty was born in 1850 in St. Louis on Eight Street between Chouteau and Gratiot. The family in 1865 moved to 1118 St. Ange Avenue in St. Louis.

When Kate returned to St. Louis in 1884 after her years in Louisiana, she lived first at 1125 St. Ange Avenue and then at 1122 St. Ange Avenue. In 1886 she moved to 3317 Morgan Street, which in now Delmar. In 1903 she moved to 4232 McPherson Avenue (the house is still there), where she died in 1904.

Kate Chopin’s home at 4232 McPherson Avenue in St Louis as it looks today.

Q: I understand that Chopin had several children. What are their names?

A: Between 1871 and 1879 Kate Chopin gave birth to five sons and a daughter — in order of birth, Jean Baptiste, Oscar Charles, George Francis, Frederick, Felix Andrew, and Lélia (baptized Marie Laïza).

Q: Did Kate Chopin speak French as well as English?

A: Yes. Her mother’s family was of French stock, and Kate grew up bilingual.

Q. My literature anthology says that Kate Chopin’s mother was Creole. Does that mean that Chopin has African-American roots?

A. No. In American English, the word “Creole” (the noun form of the word) carries several different meanings. For Kate Chopin, the following definition applies (it’s from the Merriam Webster online dictionary): “a white person descended from early French or Spanish settlers of the United States Gulf states and preserving their speech and culture.”

Q: I believe Kate Chopin visited Paris in 1870 but did not stay very long. Do you have more details about her visit?

A: According to Chopin’s Commonplace Book , as published in Kate Chopin’s Private Papers (Indiana University Press, 1998), Chopin and her husband arrived in Paris sometime between the 27th of August and the 4th of September, 1870, while France was at war with Prussia. They left the city on the 10th of September of that year. So Chopin was in Paris somewhere between one week and two weeks. She did not visit Europe again.

Q: I’m reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and I’ve just met Simon Legree. I’ve read somewhere that Simon Legree was modeled after the father of Oscar Chopin, Kate Chopin’s husband. Do you know if this is true or just rumor?

A: Here is what Emily Toth says in her 1990 biography of Kate Chopin: “Local folklore confused [Dr. Chopin, Oscar Chopin’s father] with Robert McAlpin, who had owned the land before him and who was sometimes said to be the model for Simon Legree in Uncle Tom’s Cabin .” So the connection between Oscar Chopin’s father and Simon Legree is rumor, not fact.

You may want to read Chopin’s early novel, At Fault . It includes a chapter in which two characters visit Robert McAlpin’s grave.

Q: Is Chopin, the unincorporated community in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, named after Kate Chopin?

A: Emily Toth, Kate Chopin’s biographer writes, “Ha! I’ve got the answer. Chopin, Louisiana, was named by and for Lamy Chopin, the brother of Oscar Chopin, Kate Chopin’s husband. Lamy (pronounced LAH-mee) was the landowner and major person in the area, and so he named the spot (which was just a post office) after himself.

“Lamy had an entrepreneurial streak. He’s also the one who got an old cabin on his land exhibited at the 1893 World Fair’s as ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin.’

“Gossip, but not necessary to answer this question: Lamy’s widow Fannie was the major source for Daniel Rankin [Kate Chopin’s first biographer], even though she’d barely known Kate and was a little Alzheimerish by the time she met Rankin [in the late 1920s or early 1930s]. Some of Lamy’s descendants are in and around Baton Rouge. One is or was an Episcopal priest.”

Questions about Chopin’s reputation and popularity:

Q: Was Kate Chopin’s The Awakening forgotten until her literary revival in the 1970s?

A: Yes, in general it was forgotten, although a few people in Europe and the United States were familiar with the book throughout the first half of the twentieth century. Some of Chopin’s short stories, however, were not forgotten. Several of those stories appeared in an anthology within five years after her death, others were reprinted over the years, and scholars began writing about her fiction a decade or so before it caught fire with the appearance of her Complete Works in 1969.

Q: I am writing my capstone project about Kate Chopin and I am trying to establish the relevance of her works to the contemporary reader. Do you have any idea of the number of copies of Chopin’s novel The Awakenin g purchased last year? I have done several Internet searches to no avail. I would like to reference the number as evidence that readers are still buying and discussing this powerful novel.

A: We’re sorry, but we have no way to tell how many copies of The Awakening were purchased last year. Part of the difficulty is that there are so many editions of the novel available, both as an individual book and as part of an anthology, both as a novel alone and as a novel along with short stories or supplements, both in print and in electronic form (some electronic editions can be downloaded for free), both in English in the United States and other English-speaking countries (Canada, the UK, India . . .) and in translations into twenty-some other languages sold in countries around the world. Bookstores and websites list at least a hundred editions.

So we cannot count how many copies are sold. And even if we could count purchases for an individual year, we would not know precisely how widely people are reading and discussing the book, because many books that are purchased—by libraries, for example — are passed from one person to another and read many times over a period of years, and, of course, some books that are purchased or downloaded are not read at all.

However, there are other ways to get a sense of whether readers are still discussing Kate Chopin’s novel.

This website usually averages about a thousand visits a day during the academic year from people in dozens of countries — from students like you, but also from teachers, scholars, librarians, journalists, playwrights, filmmakers, translators, book club members, bloggers, and others. We assume those visitors are reading and discussing The Awakening , in part because they send us all sorts of questions about it and about short stories that Chopin wrote, questions like those on this page and on other pages of this site.

Also, it’s possible to judge the popularity of a book by the extent to which it is transformed into other media — into plays, films, music, etc. We seek to keep track of some transformations.

Still another way is to see if books and articles about the book and the book’s author are being published and if graduate students are writing PhD dissertations about the book and its author. We include on our site nine pages that list books, articles, and PhD dissertations in English, German, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Finally, it may be helpful for you to know that according to scholars at Columbia University who examined over eight million university syllabi, The Awakening is among the most often taught American novel in English courses.

In brief, although we do not have data to show how many copies of the novel were sold last year, we think it would be accurate for you to say in your capstone report that, over a hundred years after The Awakening appeared, “readers are still buying and discussing” it.

Q: Was Kate Chopin involved in the women’s suffrage movement, in the progressive movements for educational reform, health care reform, or sanitation improvement? Was she involved in any other historically significant happenings of her time?

A: Kate Chopin was an artist, a writer of fiction, and like many artists — in the nineteenth century and today — she considered that her primary responsibility to people was showing them the truth about life as she understood it.

So if you’re asking if Kate Chopin was involved in social activism as political scientists today would understand that term, the answer is no. She was not a social reformer. Her goal was not to change the world but to describe it accurately, to show people the truth about the lives of women and men in the nineteenth-century America she knew.

If, however, you’re asking if Chopin was involved in “historically significant happenings” as many artists would understand those words, then the answer is yes. She was among the first American authors to write truthfully about women’s hidden lives, about women’s sexuality, and about some of the complexities and contradictions in women’s relationships with their husbands.

As the critic Per Seyersted phrases it, Kate Chopin “broke new ground in American literature. She was the first woman writer in her country to accept passion as a legitimate subject for serious, outspoken fiction. Revolting against tradition and authority; with a daring which we can hardy fathom today; with an uncompromising honesty and no trace of sensationalism, she undertook to give the unsparing truth about woman’s submerged life. She was something of a pioneer in the amoral treatment of sexuality, of divorce, and of woman’s urge for an existential authenticity. She is in many respects a modern writer, particularly in her awareness of the complexities of truth and the complications of freedom.”

Artists like Kate Chopin see the truth and help others to see it. Once people are able to recognize the truth, then they can create social reform movements and set out to correct wrongs and injustices.

Q: So does that mean that what I read on a blog is true, that Kate Chopin “was an integral part of the evolution of feminism, providing early 20th century readers with feminist literature that is still highly respected and studied today”?

A: No, it’s almost certainly not true, simply because, from everything we can tell, little of what many readers today consider Chopin’s feminist literature was read in the early years of the twentieth century — The Awakening , for example, or “The Story of an Hour,” or, certainly, “The Storm.” You might argue that after the 1960s or 1970s Chopin became “an integral part of the evolution of feminism,” but she probably had little or no influence on early 20th-century readers.

Q: Did Kate Chopin influence other writers or artists? Does she influence any today?

A: After the 1970s, when a remarkable literary revival made her work famous around the world, Chopin became an inspiration for artists of all kinds—women and men—as well as for translators working in twenty-some other languages.

You can see some of the influence she has had on our News page, our Popular Culture page (dealing with dance, theatre, opera, graphic fiction), our Films page, pages for The Awakening and some short stories (like “The Story of an Hour” ), and our page for Translations .

And there is Eliza Waite , a 2016 novel. Ashley E Sweeney, the novel’s author, tells us that “Eliza Waite reads/internalizes Chopin’s thoughts; Eliza refers to short stories and other works of Chopin’s, including The Awakening , which plays a significant role in her life as the novel progresses. Early feminism and enlightenment during nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century America are strong themes of the novel, let alone survival in a man’s world on the far reaches of the continent.”

Questions about Chopin’s use of French connections, expressions, and dialects:

Q: Why are there French expressions in Chopin’s novels and stories?

A: Most of the characters in Kate Chopin’s short stories and in her two novels, The Awakening , and At Fault , speak French, Spanish, Creole, or all three, in addition to English. Many people with French and Spanish roots lived in Louisiana, where most of Chopin’s works are set, and some of them spoke more than one language. Like Mark Twain and other writers of her time, Chopin, who spoke both French and English herself, was determined to be accurate in the way she recorded the speech of the people she focused on in her fiction. Some editions of her works include translations of French expressions, and Chopin usually subtly glosses such expressions in the text. Missing the meaning of a French expression is not likely to lead to a mistake in understanding a story or novel.

The Awakening " href="https://www.katechopin.org/the-awakening/#frenchquestion">Also check the question about this as it applies to The Awakening .

Q: What about the Creole or other dialectal expressions? I love Kate Chopin, but at places in the short stories, I really struggle with understanding what her characters are saying. How do I deal with that?

A: You might try reading the stories aloud — or you might find a native speaker of English who can read them aloud with feeling. Chopin is capturing what her characters sound like as they speak, so it may be helpful to hear the story, rather than read it.

For example, here’s a passage from an early Chopin story in which a caretaker at a plantation is talking to a visitor. The caretaker says that he himself would not be complaining about how run down the place has become:

“If it would been me myse’f, I would nevair grumb’. W’en a chimbly breck, I take one, two de boys; we patch ‘im up bes’ we know how. We keep on men’ de fence’, firs’ one place, anudder. . . .”

If you could hear that read aloud, you might understand better. In today’s standard English, the character would be saying something like:

“If it would [have] been me myself, I would never grumble. When a chimney breaks, I take one or two [of] the boys; we patch it up [the] best we know how. We keep on mending the fences, first [at] one place [and then at] another. . . .”

New Q: Has anyone written about Kate Chopin and her relationship to Haiti? I understand she is of French Creole ancestry but do any of those ties relate to Creoles from Haiti?

A: Two Kate Chopin scholars respond.

Thomas Bonner, Jr. suggests checking Karen Kel Roop’s dissertation at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, 2011: “‘You done cheat Mose out o’ de job, anyways, we all know dat’: Faith Healing in the Fiction of Kate Chopin.” [Haiti is cited]

He also suggests checking the Annotated Bibliography of Voodooism in Haiti by Michelle Brown, online 10/23. [Chopin is cited]

And he adds: “Online there is a thesis by Kali Lauren Oldacre at Gardner-Webb University in 2016, which may deal with Haiti as it links Chopin, Hurston, and Danticat. Also there are some online blogs mentioning Chopin and Haiti, but there are questions of authority here. The Haitian revolution 1791 to 1804 brought many migrants to New Orleans, and by the time Kate moved to New Orleans in 1870, those migrants and their descendants were long established locals.”

John Staunton writes: “This same question just came up among some of my students earlier in the semester. It led us to what looks like a student website project (which by the way, is pretty well done. Kudos to the instructor guiding these curators).

“There we got a quick answer: No, the Creoles in The Awakening are not the same as those from Haiti. But I could tell that they were rather disappointed and unsatisfied by that instability of terms.

“It’s a really interesting interpretive phenomenon, and in part I think it comes out of their wondering about Edna’s displacement as a kind of racial (as well as ethnic) displacement.”

Questions about Chopin’s attitude toward race and her stories about death:

Q: I understand some critics fault Kate Chopin for her attitudes toward race. Where could I find discussions of that subject?

A: There’s been a good deal written about Chopin and race. You might start by reading articles by Anna Shannon Elfenbein, Helen Taylor, and Elizabeth Ammons in the Norton Critical Edition of The Awakening , and you might look at Bonnie James Shaker’s Coloring Locals . For a defense of Chopin you might start by checking Emily Toth’s Unveiling Kate Chopin and Bernard Koloski’s Kate Chopin: A Study of the Short Fiction , and on line you could read David Chopin’s and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese’s comments on the Kate Chopin: A Re-Awakening site. You can find information about these and other publications about Chopin and race at the bottom of the Awakening page and the Short Stories page of this site, as well as on pages devoted to individual stories, like “Désirée’s Baby.”

Q: I know that Chopin dealt with a lot of deaths to loved ones growing up. Do many of her writings involve the death of a character? Are these writings available?

A: In addition to famous stories like “The Story of an Hour” and “Désirée’s Baby” and the novels At Fault and The Awakening , here are fifteen short stories in which the subject of death comes up (listed in order of composition):

“For Marse Chouchoute” “The Maid of Saint Phillippe” “Doctor Chevalier’s Lie” “The Return of Alcibiade” “La Belle Zoraïde” “At Chênière Caminada” “A Sentimental Soul” “Her Letters” “Odalie Misses Mass” “Dead Men’s Shoes” “Madame Martel’s Christmas Eve” “Nég Créol” “Suzette” “The Locket” “The Godmother”

Yes, all of Kate Chopin’s works are available in the books listed near the bottom of most pages on this site; both her novels and many of her stories are posted on the web.

Questions about Chopin’s style, influences, publication dates, and translations:

Q: I find it difficult to find the right terms for describing Kate Chopin’s style, which I think has some romantic elements but also some realistic ones. In what ways was Chopin influenced by other writers, like Maupassant?

A: Chopin read widely and drew from many movements in nineteenth-century literatur — romanticism (she had read Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson), realism (she reviewed a book by Hamlin Garland) and local color (she places her characters in a geographical and historical moment and details their sometimes exotic speech patterns and cultural dispositions). She mentions German philosopher and playwright Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in her work as well as other European writers from Aeschylus to Ibsen. She was deeply influenced by French writers Guy de Maupassant (she loved his economy of detail) and Émile Zola (she was impressed by his determination to tell the truth), both of whom she read in their original French. She understood that Maupassant and Zola rejected sentimental fiction, but she was drawn to the work of the French writer George Sand who at times used sentimental elements to describe a woman trying to balance the well-being of others with her own freedom and integrity.

Q: Do you know if Chopin read Charles Baudelaire, and if so, whether she read Les Fleurs du Mal ? Did she own a copy of this book?

A: We’re aware of no direct evidence that Kate Chopin read Charles Baudelaire. Everything we know about what Chopin read is described by her three biographers. You’ll find titles of their biographies at the bottom of our Biography page. In searching for possible influences on Chopin, it’s best to start with the biographers. So far as we can tell, no additional primary material about Chopin (such as evidence about whom she read) has emerged in recent years.

Q : What about Alphonse Daudet? Did she read Daudet?

A: Yes, apparently she did. Her friend William Schuyler published an article about her in Writer in August, 1894, in which he says she read both Guy de Maupassant and Daudet. Chopin’s biographer Per Seyersted notes that in her fiction she resembles Daudet, who in his work “looked at least as much for goodness and happiness as for misery.”

“One reason why Daudet spoke to Mrs. Chopin,” Seyersted adds, “was his seductive style infused with the meridional warmth, the sunny, sensuous atmosphere of his Midi [Daudet loved his native Provence, in southern France]. She had herself responded to the luxurious southern fragrance of Louisiana and to the erotic ambiance of her Gauls.”

We don’t know when she might have read Daudet, but she had been reading French fiction since she was a child. She and her husband were in Europe in 1870, shortly after Daudet published his famous collection of stories Les Lettres de mon moulin [Letters from my Mill]. Some of those stores had been published earlier in French newspapers and magazines which were available in the States.

Chopin’s later biographer Emily Toth points out that in 1878 Daudet published Le Nabob , a novel “about a woman artist who believes herself to be monstrously different, because she defies the rules of traditional society.” The artist’s name, Toth notes, is Félicia Ruys, “an unpronounceable name too much like Reisz [Mademoiselle Reisz, the pianist in The Awakening ] to be an accident.”

Q; I am currently doing research on Kate Chopin to complete a thesis on one of her short stories. I have come across a few brief statements suggesting a connection between her and Edgar Degas. I have also noticed that a few of her characters share the same names as some of Degas’ family members. I was wondering if you might be able to assist me with more concrete evidence that would establish a link?

A: Two Chopin scholars respond:

Emily Toth : In my Unveiling Kate Chopin (chapter 5), I write about the Chopin-Degas connection. Oscar Chopin did work with Degas’s brother and uncle, and the plot of The Awakening reflects events in France that Degas knew about. The Awakening also reflects, clearly, a scandalous adulterous affair in the Degas family. There are similar names and circumstances, and it’s apparent that Chopin drew on Degas and his family for gossip and inspiration. Christopher Benfey’s work ( Degas in New Orleans: Encounters in the Creole World of Kate Chopin and George Washington Cable) is not accurate, and he misreports what I wrote. He’s a good writer, but no one should take him as a source for facts. He is often just plain wrong.

Thomas Bonner, Jr. : I agree with Emily. The real crux of the Chopin-Degas connection is a multitude of clues, including Chopin’s use of the term “Impressionist,” but no document or recorded observation has been discovered as yet. The term Impressionist as applied to artists and art did not have a reported use until 1874, after Degas had left New Orleans. Benfy bases his conclusions about Kate and Degas on conjecture. It would be helpful one day to discover a thank you note from Kate to Degas (or from Degas to Kate) for a fine dinner.

Q: Do you know if Kate Chopin read Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper”? I have not found evidence that she read it.

A: Chopin scholars David Wehner, Heather Ostman, and Kelli O’Brien write that they have found no evidence that Chopin had read Gilman.

Thomas Bonner, Jr.: “The story was published in the New England Magazine in 1892 and then in a book in 1899. The St. Louis Public Library had a limited collection until its expansion in 1901. The magazine was obviously regionally centered with a largely regional circulation, and the collected story did not get published prior to the writing of The Awakening . Given that data and the lack of documentation of Chopin’s reading the story or mentioning Gilman, it would be hard to demonstrate that Chopin read Gilman despite some thematic confluences in their writing.”

Barbara Ewell: “I don’t remember any evidence for this either: however, I do seem to recall that Gilman spoke in St. Louis when Chopin was there.”

Emily Toth: “Like the others, I’ve never seen any evidence that Chopin read Gilman. That doesn’t mean that she didn’t, but just that we have no evidence.”

Eulalia Piñero Gil: “Good question. I don’t have evidence that she read Gilman, as Emily says, but I perceive the literary dialogue or the spirit of the age that most female writers of the period show in their texts. In other words, we might suggest that as a voracious reader she might have read the short story, as Gilman was a famous lecturer of the period.”

Bonnie Shaker: “As one who studies periodicals, I have also wondered about this. Not only does ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ predate The Awakening , but it circulated in a periodical. However, as Eulalia suggests, there may be other ways to reconstruct a history of influence besides precise evidence of exposure to a singular text.”