5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

by Sarah Kliff

It is never easy to contemplate the end-of-life, whether its own our experience or that of a loved one.

This has made a recent swath of beautiful essays a surprise. In different publications over the past few weeks, I've stumbled upon writers who were contemplating final days. These are, no doubt, hard stories to read. I had to take breaks as I read about Paul Kalanithi's experience facing metastatic lung cancer while parenting a toddler, and was devastated as I followed Liz Lopatto's contemplations on how to give her ailing cat the best death possible. But I also learned so much from reading these essays, too, about what it means to have a good death versus a difficult endfrom those forced to grapple with the issue. These are four stories that have stood out to me recently, alongside one essay from a few years ago that sticks with me today.

My Own Life | Oliver Sacks

As recently as last month, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. In a beautiful op-ed , published in late February in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he'll face his final moments. What I liked about this essay is how Sacks describes how his world view shifts as he sees his time on earth getting shorter, and how he thinks about the value of his time.

Before I go | Paul Kalanithi

Kalanthi began noticing symptoms — "weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough" — during his sixth year of residency as a neurologist at Stanford. A CT scan revealed metastatic lung cancer. Kalanthi writes about his daughter, Cady and how he "probably won't live long enough for her to have a memory of me." Much of his essay focuses on an interesting discussion of time, how it's become a double-edged sword. Each day, he sees his daughter grow older, a joy. But every day is also one that brings him closer to his likely death from cancer.

As I lay dying | Laurie Becklund

Becklund's essay was published posthumonously after her death on February 8 of this year. One of the unique issues she grapples with is how to discuss her terminal diagnosis with others and the challenge of not becoming defined by a disease. "Who would ever sign another book contract with a dying woman?" she writes. "Or remember Laurie Becklund, valedictorian, Fulbright scholar, former Times staff writer who exposed the Salvadoran death squads and helped The Times win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the 1992 L.A. riots? More important, and more honest, who would ever again look at me just as Laurie?"

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat | Liz Lopatto

Dorothy Parker was Lopatto's cat, a stray adopted from a local vet. And Dorothy Parker, known mostly as Dottie, died peacefullywhen she passed away earlier this month. Lopatto's essay is, in part, about what she learned about end-of-life care for humans from her cat. But perhaps more than that, it's also about the limitations of how much her experience caring for a pet can transfer to caring for another person.

Yes, Lopatto's essay is about a cat rather than a human being. No, it does not make it any easier to read. She describes in searing detail about the experience of caring for another being at the end of life. "Dottie used to weigh almost 20 pounds; she now weighs six," Lopatto writes. "My vet is right about Dottie being close to death, that it’s probably a matter of weeks rather than months."

Letting Go | Atul Gawande

"Letting Go" is a beautiful, difficult true story of death. You know from the very first sentence — "Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die" — that it is going to be tragic. This story has long been one of my favorite pieces of health care journalism because it grapples so starkly with the difficult realities of end-of-life care.

In the story, Monopoli is diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, a surprise for a non-smoking young woman. It's a devastating death sentence: doctors know that lung cancer that advanced is terminal. Gawande knew this too — Monpoli was his patient. But actually discussing this fact with a young patient with a newborn baby seemed impossible.

"Having any sort of discussion where you begin to say, 'look you probably only have a few months to live. How do we make the best of that time without giving up on the options that you have?' That was a conversation I wasn't ready to have," Gawande recounts of the case in a new Frontline documentary .

What's tragic about Monopoli's case was, of course, her death at an early age, in her 30s. But the tragedy that Gawande hones in on — the type of tragedy we talk about much less — is how terribly Monopoli's last days played out.

Most Popular

Stop setting your thermostat at 72, web3 is the future, or a scam, or both, what do we do about alice munro now, is kamala harris a better candidate now than she was four years ago, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Politics

What the world can learn from Indian liberalism

The arguments for Biden 2024 keep getting worse

Is it undemocratic to replace Biden on the ticket?

France’s elections showed a polarized country

The real lesson for America in the French and British elections

Why I quit Spotify

Heat is deadly. Why does our culture push us to ignore it?

What American cities could do right now to save us from this unbearable heat

Why are so many female pop stars flopping?

How do you know it’s time to retire?

Iran’s new president can only change the country so much

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

115 Death Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Death is an inevitable part of life that has been contemplated and explored by humans throughout history. It is a subject that evokes a wide range of emotions and thoughts, from fear and sorrow to curiosity and acceptance. Writing an essay about death can be a profound and thought-provoking experience, allowing individuals to reflect on their own mortality and explore existential questions. To inspire your writing, here are 115 death essay topic ideas and examples.

- The concept of death in different cultures.

- The role of death in religious beliefs.

- The fear of death and its impact on human behavior.

- Death as a theme in literature and poetry.

- The portrayal of death in art and cinema.

- The psychology of grief and mourning.

- The stages of grief according to Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

- How to cope with the loss of a loved one.

- The impact of death on family dynamics.

- The connection between death and existentialism.

- Near-death experiences and their implications.

- The debate between the existence of an afterlife and oblivion.

- The significance of death rituals and funeral customs.

- The ethics of euthanasia and assisted suicide.

- The right to die: exploring the concept of death with dignity.

- The role of death in philosophical thought.

- Death as a catalyst for personal growth and transformation.

- The impact of death anxiety on mental health.

- Exploring the concept of a "good death."

- The portrayal of death in popular culture.

- Death and the meaning of life.

- The portrayal of death in ancient mythology.

- Death and the concept of time.

- The impact of death on medical ethics.

- The portrayal of death in children's literature.

- The intersection of death and technology.

- Death and the fear of the unknown.

- The impact of death on social media and digital legacies.

- The acceptance of death: exploring different perspectives.

- The role of humor in coping with death.

- Death and the concept of justice.

- The impact of death on religious beliefs and practices.

- The influence of death on artistic expression.

- Death and the concept of free will.

- The portrayal of death in different historical periods.

- Death and the concept of fate.

- The impact of death on the concept of identity.

- Death and the concept of soul.

- Death and the concept of pain.

- The impact of death on medical advancements.

- Death and the concept of forgiveness.

- The portrayal of death in video games.

- Death and the concept of sacrifice.

- The impact of death on cultural traditions.

- Death and the concept of legacy.

- Death and the concept of beauty.

- The portrayal of death in religious texts.

- Death and the concept of morality.

- The impact of death on social structures.

- Death and the concept of justice in different societies.

- The portrayal of death in different artistic mediums.

- Death and the concept of love.

- The impact of death on the concept of time.

- Death and the concept of truth.

- The portrayal of death in different musical genres.

- Death and the concept of suffering.

- The impact of death on the concept of freedom.

- Death and the concept of redemption.

- The portrayal of death in different dance forms.

- Death and the concept of rebirth.

- The impact of death on the concept of beauty.

- Death and the concept of forgiveness in different cultures.

- The portrayal of death in different architectural styles.

- Death and the concept of fate in different societies.

- The impact of death on the concept of identity in different periods.

- Death and the concept of pain in different cultures.

- The portrayal of death in different fashion trends.

- Death and the concept of sacrifice in different religions.

- The impact of death on the concept of legacy in different civilizations.

- Death and the concept of beauty in different art forms.

- The portrayal of death in different culinary traditions.

- Death and the concept of justice in different historical eras.

- The impact of death on the concept of morality in different societies.

- Death and the concept of love in different cultures.

- The portrayal of death in different sports.

- Death and the concept of suffering in different religions.

- The impact of death on the concept of freedom in different periods.

- Death and the concept of redemption in different belief systems.

- The portrayal of death in different circus acts.

- Death and the concept of rebirth in different mythologies.

- The impact of death on the concept of beauty in different civilizations.

- Death and the concept of forgiveness in different cultural practices.

- The portrayal of death in different gardening styles.

- Death and the concept of fate in different belief systems.

- The impact of death on the concept of identity in different societies.

- Death and the concept of pain in different historical periods.

- The portrayal of death in different interior design trends.

- Death and the concept of sacrifice in different cultural practices.

- Death and the concept of beauty in different fashion trends.

- The portrayal of death in different music genres.

- The impact of death on the concept of morality in different periods.

- The portrayal of death in different film genres.

- The impact of death on the concept of freedom in different societies.

- The portrayal of death in different theater styles.

- The portrayal of death in different dance styles.

- The portrayal of death in different visual art forms.

- Death and the concept of beauty in different architectural styles.

- The portrayal of death in different literary genres.

Whether you choose to explore the philosophical, cultural, psychological, or artistic aspects of death, these essay topic ideas provide a wide range of possibilities to delve into this profound subject. Remember to approach the topic with sensitivity and respect, as death is a deeply personal and meaningful experience for many individuals.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

- Death And Dying

8 Popular Essays About Death, Grief & the Afterlife

Updated 05/4/2022

Published 07/19/2021

Joe Oliveto, BA in English

Contributing writer

Cake values integrity and transparency. We follow a strict editorial process to provide you with the best content possible. We also may earn commission from purchases made through affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases. Learn more in our affiliate disclosure .

Death is a strange topic for many reasons, one of which is the simple fact that different people can have vastly different opinions about discussing it.

Jump ahead to these sections:

Essays or articles about the death of a loved one, essays or articles about dealing with grief, essays or articles about the afterlife or near-death experiences.

Some fear death so greatly they don’t want to talk about it at all. However, because death is a universal human experience, there are also those who believe firmly in addressing it directly. This may be more common now than ever before due to the rise of the death positive movement and mindset.

You might believe there’s something to be gained from talking and learning about death. If so, reading essays about death, grief, and even near-death experiences can potentially help you begin addressing your own death anxiety. This list of essays and articles is a good place to start. The essays here cover losing a loved one, dealing with grief, near-death experiences, and even what someone goes through when they know they’re dying.

Losing a close loved one is never an easy experience. However, these essays on the topic can help someone find some meaning or peace in their grief.

1. ‘I’m Sorry I Didn’t Respond to Your Email, My Husband Coughed to Death Two Years Ago’ by Rachel Ward

Rachel Ward’s essay about coping with the death of her husband isn’t like many essays about death. It’s very informal, packed with sarcastic humor, and uses an FAQ format. However, it earns a spot on this list due to the powerful way it describes the process of slowly finding joy in life again after losing a close loved one.

Ward’s experience is also interesting because in the years after her husband’s death, many new people came into her life unaware that she was a widow. Thus, she often had to tell these new people a story that’s painful but unavoidable. This is a common aspect of losing a loved one that not many discussions address.

2. ‘Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat’ by Elizabeth Lopatto

Not all great essays about death need to be about human deaths! In this essay, author Elizabeth Lopatto explains how watching her beloved cat slowly die of leukemia and coordinating with her vet throughout the process helped her better understand what a “good death” looks like.

For instance, she explains how her vet provided a degree of treatment but never gave her false hope (for instance, by claiming her cat was going to beat her illness). They also worked together to make sure her cat was as comfortable as possible during the last stages of her life instead of prolonging her suffering with unnecessary treatments.

Lopatto compares this to the experiences of many people near death. Sometimes they struggle with knowing how to accept death because well-meaning doctors have given them the impression that more treatments may prolong or even save their lives, when the likelihood of them being effective is slimmer than patients may realize.

Instead, Lopatto argues that it’s important for loved ones and doctors to have honest and open conversations about death when someone’s passing is likely near. This can make it easier to prioritize their final wishes instead of filling their last days with hospital visits, uncomfortable treatments, and limited opportunities to enjoy themselves.

3. ‘The terrorist inside my husband’s brain’ by Susan Schneider Williams

This article, which Susan Schneider Williams wrote after the death of her husband Robin Willians, covers many of the topics that numerous essays about the death of a loved one cover, such as coping with life when you no longer have support from someone who offered so much of it.

However, it discusses living with someone coping with a difficult illness that you don’t fully understand, as well. The article also explains that the best way to honor loved ones who pass away after a long struggle is to work towards better understanding the illnesses that affected them.

4. ‘Before I Go’ by Paul Kalanithi

“Before I Go” is a unique essay in that it’s about the death of a loved one, written by the dying loved one. Its author, Paul Kalanithi, writes about how a terminal cancer diagnosis has changed the meaning of time for him.

Kalanithi describes believing he will die when his daughter is so young that she will likely never have any memories of him. As such, each new day brings mixed feelings. On the one hand, each day gives him a new opportunity to see his daughter grow, which brings him joy. On the other hand, he must struggle with knowing that every new day brings him closer to the day when he’ll have to leave her life.

Coping with grief can be immensely challenging. That said, as the stories in these essays illustrate, it is possible to manage grief in a positive and optimistic way.

5. Untitled by Sheryl Sandberg

This piece by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s current CEO, isn’t a traditional essay or article. It’s actually a long Facebook post. However, many find it’s one of the best essays about death and grief anyone has published in recent years.

She posted it on the last day of sheloshim for her husband, a period of 30 days involving intense mourning in Judaism. In the post, Sandberg describes in very honest terms how much she learned from those 30 days of mourning, admitting that she sometimes still experiences hopelessness, but has resolved to move forward in life productively and with dignity.

She explains how she wanted her life to be “Option A,” the one she had planned with her husband. However, because that’s no longer an option, she’s decided the best way to honor her husband’s memory is to do her absolute best with “Option B.”

This metaphor actually became the title of her next book. Option B , which Sandberg co-authored with Adam Grant, a psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, is already one of the most beloved books about death , grief, and being resilient in the face of major life changes. It may strongly appeal to anyone who also appreciates essays about death as well.

6. ‘My Own Life’ by Oliver Sacks

Grief doesn’t merely involve grieving those we’ve lost. It can take the form of the grief someone feels when they know they’re going to die.

Renowned physician and author Oliver Sacks learned he had terminal cancer in 2015. In this essay, he openly admits that he fears his death. However, he also describes how knowing he is going to die soon provides a sense of clarity about what matters most. Instead of wallowing in his grief and fear, he writes about planning to make the very most of the limited time he still has.

Belief in (or at least hope for) an afterlife has been common throughout humanity for decades. Additionally, some people who have been clinically dead report actually having gone to the afterlife and experiencing it themselves.

Whether you want the comfort that comes from learning that the afterlife may indeed exist, or you simply find the topic of near-death experiences interesting, these are a couple of short articles worth checking out.

7. ‘My Experience in a Coma’ by Eben Alexander

“My Experience in a Coma” is a shortened version of the narrative Dr. Eben Alexander shared in his book, Proof of Heaven . Alexander’s near-death experience is unique, as he’s a medical doctor who believes that his experience is (as the name of his book suggests) proof that an afterlife exists. He explains how at the time he had this experience, he was clinically braindead, and therefore should not have been able to consciously experience anything.

Alexander describes the afterlife in much the same way many others who’ve had near-death experiences describe it. He describes starting out in an “unresponsive realm” before a spinning white light that brought with it a musical melody transported him to a valley of abundant plant life, crystal pools, and angelic choirs. He states he continued to move from one realm to another, each realm higher than the last, before reaching the realm where the infinite love of God (which he says is not the “god” of any particular religion) overwhelmed him.

8. “One Man's Tale of Dying—And Then Waking Up” by Paul Perry

The author of this essay recounts what he considers to be one of the strongest near-death experience stories he’s heard out of the many he’s researched and written about over the years. The story involves Dr. Rajiv Parti, who claims his near-death experience changed his views on life dramatically.

Parti was highly materialistic before his near-death experience. During it, he claims to have been given a new perspective, realizing that life is about more than what his wealth can purchase. He returned from the experience with a permanently changed outlook.

This is common among those who claim to have had near-death experiences. Often, these experiences leave them kinder, more understanding, more spiritual, and less materialistic.

This short article is a basic introduction to Parti’s story. He describes it himself in greater detail in the book Dying to Wake Up , which he co-wrote with Paul Perry, the author of the article.

Essays About Death: Discussing a Difficult Topic

It’s completely natural and understandable to have reservations about discussing death. However, because death is unavoidable, talking about it and reading essays and books about death instead of avoiding the topic altogether is something that benefits many people. Sometimes, the only way to cope with something frightening is to address it.

Categories:

- Coping With Grief

You may also like

What is a 'Good Death' in End-of-Life Care?

11 Popular Websites About Death and End of Life

18 Questions About Death to Get You Thinking About Mortality

15 Best Children’s Books About the Death of a Parent

Essays About Death: Top 5 Examples and 9 Essay Prompts

Death includes mixed emotions and endless possibilities. If you are writing essays about death, see our examples and prompts in this article.

Over 50 million people die yearly from different causes worldwide. It’s a fact we must face when the time comes. Although the subject has plenty of dire connotations, many are still fascinated by death, enough so that literary pieces about it never cease. Every author has a reason why they want to talk about death. Most use it to put their grievances on paper to help them heal from losing a loved one. Some find writing and reading about death moving, transformative, or cathartic.

To help you write a compelling essay about death, we prepared five examples to spark your imagination:

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. Essay on Death Penalty by Aliva Manjari

2. coping with death essay by writer cameron, 3. long essay on death by prasanna, 4. because i could not stop for death argumentative essay by writer annie, 5. an unforgettable experience in my life by anonymous on gradesfixer.com, 1. life after death, 2. death rituals and ceremonies, 3. smoking: just for fun or a shortcut to the grave, 4. the end is near, 5. how do people grieve, 6. mental disorders and death, 7. are you afraid of death, 8. death and incurable diseases, 9. if i can pick how i die.

“The death penalty is no doubt unconstitutional if imposed arbitrarily, capriciously, unreasonably, discriminatorily, freakishly or wantonly, but if it is administered rationally, objectively and judiciously, it will enhance people’s confidence in criminal justice system.”

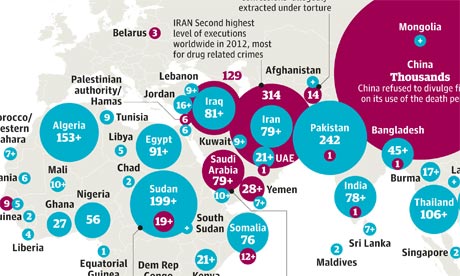

Manjari’s essay considers the death penalty as against the modern process of treating lawbreakers, where offenders have the chance to reform or defend themselves. Although the author is against the death penalty, she explains it’s not the right time to abolish it. Doing so will jeopardize social security. The essay also incorporates other relevant information, such as the countries that still have the death penalty and how they are gradually revising and looking for alternatives.

You might also be interested in our list of the best war books .

“How a person copes with grief is affected by the person’s cultural and religious background, coping skills, mental history, support systems, and the person’s social and financial status.”

Cameron defines coping and grief through sharing his personal experience. He remembers how their family and close friends went through various stages of coping when his Aunt Ann died during heart surgery. Later in his story, he mentions Ann’s last note, which she wrote before her surgery, in case something terrible happens. This note brought their family together again through shared tears and laughter. You can also check out these articles about cancer .

“Luckily or tragically, we are completely sentenced to death. But there is an interesting thing; we don’t have the knowledge of how the inevitable will strike to have a conversation.”

Prasanna states the obvious – all people die, but no one knows when. She also discusses the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Research also shows that when people die, the brain either shows a flashback of life or sees a ray of light.

Even if someone can predict the day of their death, it won’t change how the people who love them will react. Some will cry or be numb, but in the end, everyone will have to accept the inevitable. The essay ends with the philosophical belief that the soul never dies and is reborn in a new identity and body. You can also check out these elegy examples .

“People have busy lives, and don’t think of their own death, however, the speaker admits that she was willing to put aside her distractions and go with death. She seemed to find it pretty charming.”

The author focuses on how Emily Dickinson ’s “ Because I Could Not Stop for Death ” describes death. In the poem, the author portrays death as a gentle, handsome, and neat man who picks up a woman with a carriage to take her to the grave. The essay expounds on how Dickinson uses personification and imagery to illustrate death.

“The death of a loved one is one of the hardest things an individual can bring themselves to talk about; however, I will never forget that day in the chapter of my life, as while one story continued another’s ended.”

The essay delve’s into the author’s recollection of their grandmother’s passing. They recount the things engrained in their mind from that day – their sister’s loud cries, the pounding and sinking of their heart, and the first time they saw their father cry.

Looking for more? Check out these essays about losing a loved one .

9 Easy Writing Prompts on Essays About Death

Are you still struggling to choose a topic for your essay? Here are prompts you can use for your paper:

Your imagination is the limit when you pick this prompt for your essay. Because no one can confirm what happens to people after death, you can create an essay describing what kind of world exists after death. For instance, you can imagine yourself as a ghost that lingers on the Earth for a bit. Then, you can go to whichever place you desire and visit anyone you wish to say proper goodbyes to first before crossing to the afterlife.

Every country, religion, and culture has ways of honoring the dead. Choose a tribe, religion, or place, and discuss their death rituals and traditions regarding wakes and funerals. Include the reasons behind these activities. Conclude your essay with an opinion on these rituals and ceremonies but don’t forget to be respectful of everyone’s beliefs.

Smoking is still one of the most prevalent bad habits since tobacco’s creation in 1531 . Discuss your thoughts on individuals who believe there’s nothing wrong with this habit and inadvertently pass secondhand smoke to others. Include how to avoid chain-smokers and if we should let people kill themselves through excessive smoking. Add statistics and research to support your claims.

Collate people’s comments when they find out their death is near. Do this through interviews, and let your respondents list down what they’ll do first after hearing the simulated news. Then, add their reactions to your essay.

There is no proper way of grieving. People grieve in their way. Briefly discuss death and grieving at the start of your essay. Then, narrate a personal experience you’ve had with grieving to make your essay more relatable. Or you can compare how different people grieve. To give you an idea, you can mention that your father’s way of grieving is drowning himself in work while your mom openly cries and talk about her memories of the loved one who just passed away.

Explain how people suffering from mental illnesses view death. Then, measure it against how ordinary people see the end. Include research showing death rates caused by mental illnesses to prove your point. To make organizing information about the topic more manageable, you can also focus on one mental illness and relate it to death.

Check out our guide on how to write essays about depression .

Sometimes, seriously ill people say they are no longer afraid of death. For others, losing a loved one is even more terrifying than death itself. Share what you think of death and include factors that affected your perception of it.

People with incurable diseases are often ready to face death. For this prompt, write about individuals who faced their terminal illnesses head-on and didn’t let it define how they lived their lives. You can also review literary pieces that show these brave souls’ struggle and triumph. A great series to watch is “ My Last Days .”

You might also be interested in these epitaph examples .

No one knows how they’ll leave this world, but if you have the chance to choose how you part with your loved ones, what will it be? Probe into this imagined situation. For example, you can write: “I want to die at an old age, surrounded by family and friends who love me. I hope it’ll be a peaceful death after I’ve done everything I wanted in life.”

To make your essay more intriguing, put unexpected events in it. Check out these plot twist ideas .

May 3, 2023

Contemplating Mortality: Powerful Essays on Death and Inspiring Perspectives

The prospect of death may be unsettling, but it also holds a deep fascination for many of us. If you're curious to explore the many facets of mortality, from the scientific to the spiritual, our article is the perfect place to start. With expert guidance and a wealth of inspiration, we'll help you write an essay that engages and enlightens readers on one of life's most enduring mysteries!

Death is a universal human experience that we all must face at some point in our lives. While it can be difficult to contemplate mortality, reflecting on death and loss can offer inspiring perspectives on the nature of life and the importance of living in the present moment. In this collection of powerful essays about death, we explore profound writings that delve into the human experience of coping with death, grief, acceptance, and philosophical reflections on mortality.

Through these essays, readers can gain insight into different perspectives on death and how we can cope with it. From personal accounts of loss to philosophical reflections on the meaning of life, these essays offer a diverse range of perspectives that will inspire and challenge readers to contemplate their mortality.

The Inevitable: Coping with Mortality and Grief

Mortality is a reality that we all have to face, and it is something that we cannot avoid. While we may all wish to live forever, the truth is that we will all eventually pass away. In this article, we will explore different aspects of coping with mortality and grief, including understanding the grieving process, dealing with the fear of death, finding meaning in life, and seeking support.

Understanding the Grieving Process

Grief is a natural and normal response to loss. It is a process that we all go through when we lose someone or something important to us. The grieving process can be different for each person and can take different amounts of time. Some common stages of grief include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. It is important to remember that there is no right or wrong way to grieve and that it is a personal process.

Denial is often the first stage of grief. It is a natural response to shock and disbelief. During this stage, we may refuse to believe that our loved one has passed away or that we are facing our mortality.

Anger is a common stage of grief. It can manifest as feelings of frustration, resentment, and even rage. It is important to allow yourself to feel angry and to express your emotions healthily.

Bargaining is often the stage of grief where we try to make deals with a higher power or the universe in an attempt to avoid our grief or loss. We may make promises or ask for help in exchange for something else.

Depression is a natural response to loss. It is important to allow yourself to feel sad and to seek support from others.

Acceptance is often the final stage of grief. It is when we come to terms with our loss and begin to move forward with our lives.

Dealing with the Fear of Death

The fear of death is a natural response to the realization of our mortality. It is important to acknowledge and accept our fear of death but also to not let it control our lives. Here are some ways to deal with the fear of death:

Accepting Mortality

Accepting our mortality is an important step in dealing with the fear of death. We must understand that death is a natural part of life and that it is something that we cannot avoid.

Finding Meaning in Life

Finding meaning in life can help us cope with the fear of death. It is important to pursue activities and goals that are meaningful and fulfilling to us.

Seeking Support

Seeking support from friends, family, or a therapist can help us cope with the fear of death. Talking about our fears and feelings can help us process them and move forward.

Finding meaning in life is important in coping with mortality and grief. It can help us find purpose and fulfillment, even in difficult times. Here are some ways to find meaning in life:

Pursuing Passions

Pursuing our passions and interests can help us find meaning and purpose in life. It is important to do things that we enjoy and that give us a sense of accomplishment.

Helping Others

Helping others can give us a sense of purpose and fulfillment. It can also help us feel connected to others and make a positive impact on the world.

Making Connections

Making connections with others is important in finding meaning in life. It is important to build relationships and connections with people who share our values and interests.

Seeking support is crucial when coping with mortality and grief. Here are some ways to seek support:

Talking to Friends and Family

Talking to friends and family members can provide us with a sense of comfort and support. It is important to express our feelings and emotions to those we trust.

Joining a Support Group

Joining a support group can help us connect with others who are going through similar experiences. It can provide us with a safe space to share our feelings and find support.

Seeking Professional Help

Seeking help from a therapist or counselor can help cope with grief and mortality. A mental health professional can provide us with the tools and support we need to process our emotions and move forward.

Coping with mortality and grief is a natural part of life. It is important to understand that grief is a personal process that may take time to work through. Finding meaning in life, dealing with the fear of death, and seeking support are all important ways to cope with mortality and grief. Remember to take care of yourself, allow yourself to feel your emotions, and seek support when needed.

The Ethics of Death: A Philosophical Exploration

Death is an inevitable part of life, and it is something that we will all experience at some point. It is a topic that has fascinated philosophers for centuries, and it continues to be debated to this day. In this article, we will explore the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, considering questions such as what it means to die, the morality of assisted suicide, and the meaning of life in the face of death.

Death is a topic that elicits a wide range of emotions, from fear and sadness to acceptance and peace. Philosophers have long been interested in exploring the ethical implications of death, and in this article, we will delve into some of the most pressing questions in this field.

What does it mean to die?

The concept of death is a complex one, and there are many different ways to approach it from a philosophical perspective. One question that arises is what it means to die. Is death simply the cessation of bodily functions, or is there something more to it than that? Many philosophers argue that death represents the end of consciousness and the self, which raises questions about the nature of the soul and the afterlife.

The morality of assisted suicide

Assisted suicide is a controversial topic, and it raises several ethical concerns. On the one hand, some argue that individuals have the right to end their own lives if they are suffering from a terminal illness or unbearable pain. On the other hand, others argue that assisting someone in taking their own life is morally wrong and violates the sanctity of life. We will explore these arguments and consider the ethical implications of assisted suicide.

The meaning of life in the face of death

The inevitability of death raises important questions about the meaning of life. If our time on earth is finite, what is the purpose of our existence? Is there a higher meaning to life, or is it simply a product of biological processes? Many philosophers have grappled with these questions, and we will explore some of the most influential theories in this field.

The role of death in shaping our lives

While death is often seen as a negative force, it can also have a positive impact on our lives. The knowledge that our time on earth is limited can motivate us to live life to the fullest and to prioritize the things that truly matter. We will explore the role of death in shaping our values, goals, and priorities, and consider how we can use this knowledge to live more fulfilling lives.

The ethics of mourning

The process of mourning is an important part of the human experience, and it raises several ethical questions. How should we respond to the death of others, and what is our ethical responsibility to those who are grieving? We will explore these questions and consider how we can support those who are mourning while also respecting their autonomy and individual experiences.

The ethics of immortality

The idea of immortality has long been a fascination for humanity, but it raises important ethical questions. If we were able to live forever, what would be the implications for our sense of self, our relationships with others, and our moral responsibilities? We will explore the ethical implications of immortality and consider how it might challenge our understanding of what it means to be human.

The ethics of death in different cultural contexts

Death is a universal human experience, but how it is understood and experienced varies across different cultures. We will explore how different cultures approach death, mourning, and the afterlife, and consider the ethical implications of these differences.

Death is a complex and multifaceted topic, and it raises important questions about the nature of life, morality, and human experience. By exploring the ethics of death from a philosophical perspective, we can gain a deeper understanding of these questions and how they shape our lives.

The Ripple Effect of Loss: How Death Impacts Relationships

Losing a loved one is one of the most challenging experiences one can go through in life. It is a universal experience that touches people of all ages, cultures, and backgrounds. The grief that follows the death of someone close can be overwhelming and can take a significant toll on an individual's mental and physical health. However, it is not only the individual who experiences the grief but also the people around them. In this article, we will discuss the ripple effect of loss and how death impacts relationships.

Understanding Grief and Loss

Grief is the natural response to loss, and it can manifest in many different ways. The process of grieving is unique to each individual and can be affected by many factors, such as culture, religion, and personal beliefs. Grief can be intense and can impact all areas of life, including relationships, work, and physical health.

The Impact of Loss on Relationships

Death can impact relationships in many ways, and the effects can be long-lasting. Below are some of how loss can affect relationships:

1. Changes in Roles and Responsibilities

When someone dies, the roles and responsibilities within a family or social circle can shift dramatically. For example, a spouse who has lost their partner may have to take on responsibilities they never had before, such as managing finances or taking care of children. This can be a difficult adjustment, and it can put a strain on the relationship.

2. Changes in Communication

Grief can make it challenging to communicate with others effectively. Some people may withdraw and isolate themselves, while others may become angry and lash out. It is essential to understand that everyone grieves differently, and there is no right or wrong way to do it. However, these changes in communication can impact relationships, and it may take time to adjust to new ways of interacting with others.

3. Changes in Emotional Connection

When someone dies, the emotional connection between individuals can change. For example, a parent who has lost a child may find it challenging to connect with other parents who still have their children. This can lead to feelings of isolation and disconnection, and it can strain relationships.

4. Changes in Social Support

Social support is critical when dealing with grief and loss. However, it is not uncommon for people to feel unsupported during this time. Friends and family may not know what to say or do, or they may simply be too overwhelmed with their grief to offer support. This lack of social support can impact relationships and make it challenging to cope with grief.

Coping with Loss and Its Impact on Relationships

Coping with grief and loss is a long and difficult process, but it is possible to find ways to manage the impact on relationships. Below are some strategies that can help:

1. Communication

Effective communication is essential when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to talk about how you feel and what you need from others. This can help to reduce misunderstandings and make it easier to navigate changes in relationships.

2. Seek Support

It is important to seek support from friends, family, or a professional if you are struggling to cope with grief and loss. Having someone to talk to can help to alleviate feelings of isolation and provide a safe space to process emotions.

3. Self-Care

Self-care is critical when dealing with grief and loss. It is essential to take care of your physical and emotional well-being. This can include things like exercise, eating well, and engaging in activities that you enjoy.

4. Allow for Flexibility

It is essential to allow for flexibility in relationships when dealing with grief and loss. People may not be able to provide the same level of support they once did or may need more support than they did before. Being open to changes in roles and responsibilities can help to reduce strain on relationships.

5. Find Meaning

Finding meaning in the loss can be a powerful way to cope with grief and loss. This can involve creating a memorial, participating in a support group, or volunteering for a cause that is meaningful to you.

The impact of loss is not limited to the individual who experiences it but extends to those around them as well. Relationships can be greatly impacted by the death of a loved one, and it is important to be aware of the changes that may occur. Coping with loss and its impact on relationships involves effective communication, seeking support, self-care, flexibility, and finding meaning.

What Lies Beyond Reflections on the Mystery of Death

Death is an inevitable part of life, and yet it remains one of the greatest mysteries that we face as humans. What happens when we die? Is there an afterlife? These are questions that have puzzled us for centuries, and they continue to do so today. In this article, we will explore the various perspectives on death and what lies beyond.

Understanding Death

Before we can delve into what lies beyond, we must first understand what death is. Death is defined as the permanent cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. This can occur as a result of illness, injury, or simply old age. Death is a natural process that occurs to all living things, but it is also a process that is often accompanied by fear and uncertainty.

The Physical Process of Death

When a person dies, their body undergoes several physical changes. The heart stops beating, and the body begins to cool and stiffen. This is known as rigor mortis, and it typically sets in within 2-6 hours after death. The body also begins to break down, and this can lead to a release of gases that cause bloating and discoloration.

The Psychological Experience of Death

In addition to the physical changes that occur during and after death, there is also a psychological experience that accompanies it. Many people report feeling a sense of detachment from their physical body, as well as a sense of peace and calm. Others report seeing bright lights or visions of loved ones who have already passed on.

Perspectives on What Lies Beyond

There are many different perspectives on what lies beyond death. Some people believe in an afterlife, while others believe in reincarnation or simply that death is the end of consciousness. Let's explore some of these perspectives in more detail.

One of the most common beliefs about what lies beyond death is the idea of an afterlife. This can take many forms, depending on one's religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, many Christians believe in heaven and hell, where people go after they die depending on their actions during life. Muslims believe in paradise and hellfire, while Hindus believe in reincarnation.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is the belief that after we die, our consciousness is reborn into a new body. This can be based on karma, meaning that the quality of one's past actions will determine the quality of their next life. Some people believe that we can choose the circumstances of our next life based on our desires and attachments in this life.

End of Consciousness

The idea that death is simply the end of consciousness is a common belief among atheists and materialists. This view holds that the brain is responsible for creating consciousness, and when the brain dies, consciousness ceases to exist. While this view may be comforting to some, others find it unsettling.

Death is a complex and mysterious phenomenon that continues to fascinate us. While we may never fully understand what lies beyond death, it's important to remember that everyone has their own beliefs and perspectives on the matter. Whether you believe in an afterlife, reincarnation, or simply the end of consciousness, it's important to find ways to cope with the loss of a loved one and to find peace with your mortality.

Final Words

In conclusion, these powerful essays on death offer inspiring perspectives and deep insights into the human experience of coping with mortality, grief, and loss. From personal accounts to philosophical reflections, these essays provide a diverse range of perspectives that encourage readers to contemplate their mortality and the meaning of life.

By reading and reflecting on these essays, readers can gain a better understanding of how death shapes our lives and relationships, and how we can learn to accept and cope with this inevitable part of the human experience.

If you're looking for a tool to help you write articles, essays, product descriptions, and more, Jenni.ai could be just what you need. With its AI-powered features, Jenni can help you write faster and more efficiently, saving you time and effort. Whether you're a student writing an essay or a professional writer crafting a blog post, Jenni's autocomplete feature, customized styles, and in-text citations can help you produce high-quality content in no time. Don't miss out on the opportunity to supercharge your next research paper or writing project – sign up for Jenni.ai today and start writing with confidence!

Try Jenni for free today

Create your first piece of content with Jenni today and never look back

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — The Fault in Our Stars — The Theme of Death, Loss, and Grief

The Theme of Death, Loss, and Grief

- Categories: The Fault in Our Stars

About this sample

Words: 512 |

Published: Jan 29, 2024

Words: 512 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Interpretation of death as a theme, exploration of loss as a theme, discussion of grief as a theme, analysis of the relationship between death, loss, and grief, comparison of different perspectives and cultural interpretations.

- Shakespeare, William. "Hamlet."

- Green, John. "The Fault in Our Stars."

- Morrison, Ton"Beloved."

- Garcia Marquez, Gabriel. "One Hundred Years of Solitude."

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1249 words

6 pages / 2729 words

3.5 pages / 1498 words

4 pages / 1725 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on The Fault in Our Stars

John Green’s novel “Looking for Alaska” tells the story of Miles “Pudge” Halter, a young man who is seeking a deeper understanding of life and its meaning. Throughout the novel, Pudge is preoccupied with the idea of the “Great [...]

The Fault in Our Stars, written by John Green, is a novel that tackles the difficult topic of terminal illness and the impact it has on the lives of the main characters, Hazel Grace Lancaster and Augustus Waters. The novel [...]

In the book The Fault In Our Stars by John Green, the main character, Hazel Grace, is introduced as a teen. However, she’s not your average teen, she is suffering from thyroid (lung) cancer. She’s described as a sixteen-year-old [...]

John Green's novel, "The Fault in Our Stars," tells the poignant tale of two teenagers who fall in love amidst the looming shadow of cancer. Unlike typical teenage romance narratives, this story is marked by an unresolvable [...]

In psychology, conflict refers to anytime when people have opposing or incompatible actions, objectives, or ideas. The psychologists define conflict to be a state of opposition and disagreement between two or more people, which [...]

In John Green's novel "The Fault in Our Stars," Hazel Grace Lancaster emerges as the central character and protagonist, grappling with the challenges of a terminal cancer diagnosis. The story unfolds as Hazel navigates her [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

This article considers several questions concerning the philosophy of death.

First , it discusses what it is to be alive. This topic arises because to die is roughly to lose one’s life.

The second topic is the nature of death, and how it bears on the persistence of organisms and persons.

The third topic is the harm thesis , the claim that death can harm the individual who dies. Perhaps the most influential case against the harm thesis was made by Epicurus. His argument is discussed, as is a contemporary response, the deprivationist defense of the harm thesis.

The fourth topic is a question that seems to confront proponents of the harm thesis, especially those who offer some version of the deprivationist defense: if a person is harmed by her death, at what time does her death make her worse off than she otherwise would be? Some answers are considered.

Fifth is further issues that may lead us to doubt the harm thesis. One is a further question about deprivationism: we are not always harmed by what deprives us of things; what makes some of these worrisome and not others? Next is a question concerning the fact that there are two different directions in which our lives could be extended: into the past (our lives could have been longer if they began earlier), or into the future (they could have been longer if they ended later). Assuming the former does not matter to us, why should the latter?

The sixth topic concerns events that occur after a person has died: is it possible for these events to harm her?

Seventh is a controversy concerning whether extreme long life, even immortality, would be good for us. Of particular interest here is a dispute between Thomas Nagel, who says that death is an evil whenever it comes, and Bernard Williams, who argues that, while premature death is a misfortune, it is a good thing that we are not immortal, since we cannot continue to have our current characters and remain meaningfully attached to life forever.

A final controversy concerns whether or not the harmfulness of death can be reduced. It may be that, by adjusting our conception of our well-being, and by altering our attitudes, we can reduce or eliminate the threat death poses us. But there is a case to be made that such efforts backfire if taken to extremes.

1.1 Life as a Substance

1.2 life as an event, 1.3 life as a property, 2.1 life and death, 2.2 death and suspended vitality, 2.3 being dead, 2.4 resurrection, 2.5 death and what we are, 2.6 death and existence, 2.7 criteria for death, 3.1 the epicurean case, 3.2 the deprivationist defense, 4.1 concurrentism, 4.2 priorism, 4.3 subsequentism, 4.4 indefinitism, 4.5 atemporalism, 5.1 harmless preclusion.

- 5.2 Lucretius and the Symmetry Argument

6.1 Doubts About Posthumous Harm

6.2 retroactive harm, 7.1 never dying would be good, 7.2 never dying would be a misfortune, 8. can death’s harmfulness be reduced, other internet resources, related entries.

To die is to cease to be alive. To clarify death further, then, we will need to say a bit about the nature of life.

Some theorists have said that life is a substance of some sort. A more plausible view is that life is a property of some sort, but we should also consider the possibility that lives are events. If we say that lives are events, we will want to know something about how to distinguish them from other events, and how they are related to the individuals that are alive. It would also be useful to know the persistence conditions for a life. If instead we conclude that life (or alive ) is a property, we will want to clarify it, and identify what sorts of things bear it. Let us briefly discuss each of these views—that life is a substance, a property, or an event.

We can deal quickly with the view called ‘vitalism’ (defended by Hans Driesch, 1908 and 1914, among others), which holds that being alive consists in containing some special substance called ‘life.’ Vitalism is a nonstarter since it is unclear what sort of stuff vitalists take life to be, and because no likely candidates—no special stuff found in all and only in living things—have been detected. Moreover, vitalism faces a further difficulty, which Fred Feldman calls ‘the Jonah Problem’: a dead thing, such as a whale, may have a living thing, say Jonah, inside it; if Jonah has ‘life’ inside him, then so does the whale, but by hypothesis the whale is not alive. Of course, in this example Jonah is in the whale’s stomach, not in its cells, but the difficulty cannot be solved by saying that an object is alive if and only if it has ‘life’ in its cells, as an infectious agent (organisms with ‘life’ in them) could survive, for a time, within the dead cells of a dead whale.

As Jay Rosenberg noted (1983, p. 22, 103), sometimes when we speak of a life we mean to refer to the events that make up something’s history—the things that it did and the things that happened to it. (For example, the publication of The Problems of Philosophy was one of the events that made up one life, namely Bertrand Russell’s.) Yet a rock and a corpse have histories, and neither has a life. Presumably, then, ‘a life,’ in the sense we are discussing, refers to the history of something that is alive. In that case what we are really looking for is clarification of a property, not an event. We want clarification of what it is to be alive.

According to a second theorist, Peter van Inwagen, while a life is indeed an event, it is not the history of something. “‘Russell’s life,’” van Inwagen writes (1990, p. 83), “denotes a purely biological event, an event which took place entirely inside Russell’s skin and which went on for ninety-seven years.” Russell’s life included the oxygenation of his hemoglobin molecules but not the publication of his books.

If lives are biological events, it would be useful to know more about what they are, how they are individuated, and what their persistence conditions are. Van Inwagen declines to provide these details (1990, p. 145). He assumes that (the events he calls) lives are familiar enough to us that we can pick them out. But he does make the useful comment that each such event is constituted by certain self-organizing activities in which some molecules engage, and that it is analogous to a parade, which is an event constituted by certain marching-related activities of some people. Having taken the notion of a life for granted, he draws upon it in his account of organisms. On his view (1990, p. 90), some things compose an organism if and only if their activity constitutes a life.

Many theorists have defended the view that life, or (being) alive, is a property, but there is considerable disagreement among them about what precisely that property is. The main views on offer are life-functionalist accounts and accounts that analyze life in terms of DNA or genetic information or evolution by natural selection.

Life-functionalism, a view introduced by Aristotle, analyzes the property alive in terms of one or more salient functions that living things typically are able to perform. The salient functions Aristotle listed were nutrition, reproduction, sensation, autonomous motion, and thought. However, life-functionists disagree about how to formulate their account and about which functions are salient. Take Aristotle’s list. Obviously, it would be a mistake to say that something is alive if and only if it can perform all of the functions on the list. Might we say that, for something to be alive, it suffices that it be capable of one or more of the listed functions? Is being capable of one of these functions in particular necessary for something to be alive? As Fred Feldman points out, neither of the suggestions just mentioned is acceptable. Devices such as Roomba cleaning robots can do one of Aristotle’s functions, namely move themselves, but are not alive, so being able to do at least one listed function does not suffice for being alive. Nor is it plausible to say that any one on the list is necessary for being alive. Which on the list would this necessary function be? Perhaps nutrition? Adult silk moths are alive but lack a digestive system, so are incapable of nutrition. And, as many theorists have noticed, many living things cannot reproduce; examples include organisms whose reproductive organs are damaged and hybrid animals such as mules.

What, now, about accounts that analyze life in terms of genetic information? Feldman thinks that something like the Jonah problem arises for any account according which being alive consists in containing DNA or other genetic information, as dead organisms contain DNA. A further problem for such views is that it is conceivable there are or could be life forms (say on other planets) that are not based on genetic information. This latter difficulty can be avoided if we say that being alive consists in having the ability to evolve, to engage in Darwinian evolution, assuming that evolution by natural selection is possible for living things that lack nucleic acid. We might adopt NASA’s definition, according to which life is “a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.” However, accounts like NASA’s are implausible for a further reason: while the ability to evolve by natural selection is something that collections of organisms—species—may or may not have, it is not a feature an individual organism may have. Later members of a species come to have features earlier members lacked; some of these new features may make survival more or less likely, and the less ‘fit’ are weeded out of existence. An individual organism, such as a particular dog, cannot undergo this process. Yet individuals may be alive.

Because he has encountered no successful account of life, no account exempt from counterexamples, Feldman concludes that “life is a mystery” (p. 55). Despite his skepticism, however, there is a good case to be made for saying that what distinguishes objects that are alive from objects that are not is that the latter have a distinctive sort of control over what composes them, which the former lack. Let us see if we can make this claim clearer.

Consider ordinary composite material objects that are not alive. We can assume that, at a given time, these are made up of, or composed of, more simple things, such as molecules, by virtue of the fact that the latter meet various conditions. Among the conditions is the requirement that (in some sense in need of clarification) they be bonded together . Take the boulder near my front porch. Among the things that compose it now will be a few molecules, say four molecules near the center of the boulder, that are bonded together, in that each is bonded to the others, directly or indirectly (a molecule, A, is in directly bonded to another molecule, B, if A is directly bonded to a molecule C that is directly bonded to B, or if A is bonded to a molecule that is indirectly bonded to B). The things that make up the boulder are not limited to these four molecules, but they are limited to molecules that are bonded to them. Nor is the boulder unique in this way; something similar seems true of any composite material object. A composite material object is composed of some things at a time only if those things are bonded together at that time.

What sort of bonding relationship holds among the things that compose material objects? Any answer to this question will be controversial. Let us set it aside, and move on to some further assumptions about the composition of nonliving composite material objects, namely that a great many of them persist for a while (some persist for a very long time) and that what composes them at one time normally differs from what composes them at other times. Exactly how this works is a complicated matter, but among the conditions that such objects must meet if they are to persist is that any change in their composition be incremental. (Even this condition is controversial. For more on material objects, see the article Material Constitution and Ordinary objects.) Consider the boulder again. Suppose that at one time, t 0 , it is composed of some molecules, and that all or most of these molecules remain bonded to each other until a later time t 1 . Suppose, too, that no or few (few as compared to the number of molecules that composed the boulder at t 0 ) molecules come to be newly bonded to these by the time that t 1 rolls around. Under these conditions the boulder undergoes an incremental change in composition, and it seems plausible to say that the boulder remains in existence over the interval t 0 – t 1 , and, at t 1 , is composed of the molecules that remain bonded together with the molecules that are newly attached to them. Presumably, it will also survive a series of such incremental changes in composition. But it will not survive drastic and sudden changes. It would stop existing, for example, if the molecules that compose it were suddenly dispersed.

Enough said about composite material objects that are not alive. Now let us see if we can shed some light on what makes living objects special. What is it that distinguishes an object that is alive from an object that is not?

The answer seems to be that, normally, a live object has a distinctive sort of control over whether things come to be, or cease to be, part of it. The control in question is made possible by activities its constituents themselves are capable of. Contrast objects that are not alive, say automobiles. What an ordinary car is composed of is settled for the car by the mechanics who repair it (detaching some parts and affixing others), by whether it is involved in an accident and loses some parts, and so forth. Imagine a car that is not passive in this way. Imagine that its parts were somehow capable of replacing some of themselves with fresh parts, without assistance from outside, so that the activities of the parts that compose the car today were responsible for its being composed of certain parts tomorrow. That would make it quite lifelike.

Let us describe, in a bit more detail, what the molecules that compose living objects can do:

- Working together, these molecules can engage in activities that are integrated in conformity with (under the control of) the information that some of them carry (information that is comparable to blueprints and instructions), much as soldiers that make up an army can engage in activities that are integrated in conformity with battle plans and instructions issued by the commanding officers that are among them.

- Deploying these activities, the molecules can self-modify, in the sense that they can bond new (perhaps recently ingested) molecules to themselves, or prune (and excrete) some away, combining themselves in various ways (e.g., constructing cells), thereby giving way to a slightly different assembly of molecules at a later time, and fueling their activities by drawing upon external energy sources or stored reserves.

- The molecules can also pass along their ability to self-modify, enabling the molecules to which they give way to continue these activities, thus allowing the object they compose to sustain a given form (or forms) over time (say that of a dog) despite the fact that what composes that object at one time differs from what composes it at another time.

The view on offer—we might call it the compositional account of life—is that an object is composed of things that are capable of the activities just described if and only if it is alive.

This account of life needs refinement, but it avoids at least most of the worries mentioned earlier. It implies that an object may be alive even though it is sterile (as in the case of mules), even though it survives on stored energy (as in the case of a silk moth), and conceivably even if it lacks nucleic acid (yet is still composed of things that engage in activities integrated in conformity with information they carry). In fact, it implies that being capable of none of the items on Aristotle’s list is necessary nor sufficient for being alive. What is more, the compositional account just sketched implies that being alive is a property an individual, say the last remaining dodo, may bear on its own, which suggests that it may be alive without being capable of Darwinian evolution. At the same time, it explains how collections of live individuals may evolve. Individual objects are alive only if their composition is under the control of some of their parts (e.g., nucleic acid molecules) that carry information. The mechanisms by which such information is carried tend to be modified over time, altering the information they carry, and thus the features of the organisms they help shape, introducing mutations that may or may not facilitate survival. (For more on the nature of life, see Bedau 2014 and the entry on Life.)

The previous section discussed the nature of life, thereby clarifying what it is that death ends. This section discusses the nature of death and how death is related to the persistence of organisms and persons. (For an excellent discussion of views of death outside of the analytic tradition, see Schumacher 2010.)

According to the compositional account of life discussed in the previous section, objects that are alive have a distinctive capacity to control what they are composed of, fixing these constituents together in various ways, by virtue of the fact that their constituents can engage in various self-modifying activities that are integrated in conformity with information they carry. Let us call these vital activities .

It is one thing to have the capacity to engage in vital activities and another actually to engage in them, just as there is a difference between having the ability to run and actually running. Being alive seems to involve the former. It consists in having the relevant capacity. To die is to lose this capacity. We can call this the loss of life account of death .

The event by which the capacity to engage in vital activities is lost is one thing, and the state of affairs of its having been lost it is another. ‘Death’ can refer to either. However, the capacity to engage in vital activities may be lost gradually, rather than all at once, so it is reasonable to speak of a process of dying. In some cases that process is especially complicated, because the self-modifying activities of some organisms result in the construction of complex physiological systems that must remain largely intact for the self-modifying activities of these organisms to remain integrated. In defining death, some theorists focus on these systems, and claim that an organism’s life ends when that organism’s physiological systems can no longer function as an integrated whole, or when this loss becomes irreversible (Christopher Belshaw 2009; David DeGrazia 2014).

The loss of life account of death has been challenged by theorists who claim that things whose vital activities are suspended are not alive (Feldman 1992, Christopher Belsaw 2009, Cody Gilmore 2013, and David DeGrazia 2014). When zygotes and embryos are frozen for later use in the in vitro fertilization procedure, their vital activities are brought to a stop, or very nearly so. The same goes for water bears that are dehydrated, and for seeds and spores. It seems clear that the zygotes and water bears are not dead, since their vital activities can easily be restarted—by warming the zygote or by wetting the water bear. They are not dead, but are they alive? If we deny that they are alive, presumably we would do so on the grounds that their vital activities are halted. If something’s life can be ended by suspending its vital activities without its dying, then we must reject the loss of life account of death.

However, the loss of life account is thoroughly established in ordinary usage, and is easily reconciled with the possibility of suspended vitality. In denying that frozen embryos are dead, it is clear that we mean to emphasize that they have not lost the capacity to deploy their vital activities. When we say that something is dead, we mean to emphasize that this capacity has been lost. Having used ‘dead’ to signal this loss, why would we want to use the word ‘alive’ to signal the fact that something is making active use of its vital activities? Our best option is to use a pair of contrasting terms. We can use ‘viable’ to indicate that something has the capacity to deploy vital activities and ‘unviable’ to indicate that it has lost this capacity. When instead we are concerned about whether or not something is engaging its vital activities, we can use different contrasting terms, say ‘vital’ and ‘nonvital’, the former to characterize something that is employing its capacity for vital activities and the latter to characterize something that is not making use of its capacity for vital activities. What seems relatively uncontroversial is that being dead consists in unviability. To retain the loss of life account, we have only to add that being alive consists in viability. We can then say that a frozen embryo is viable and hence alive despite its lack of vitality, and it will die if its life ends (it will die if it ceases to be viable). Of course, if we are willing to abandon the loss of life account, we could instead use ‘alive’ to characterize something that is both viable and vital. We would then say that a frozen embryo is not alive (since it lacks vitality) but also that it is not dead (since it remains viable).

People often speak of being dead as a ‘state’ or ‘condition’ as opposed to an event or process. They say an organism comes to be in this state once it dies. This way of speaking can be puzzling on the assumption that what dies ceases to exist. (This assumption is discussed below.) If the assumption is true, then an organism that dies stops existing but simultaneously comes to be in the state of death. Mustn’t something exist at a time if it is (literally) in some state at that time? But of course it would be absurd to deny that something can truly be dead on the grounds that death is a state and what does not exist at a time cannot be in any state at that time.

Why not solve the problem by saying that upon dying an organism leaves a corpse, and it is the corpse that is in the state of being dead? There are several problems with this suggestion. Some organisms do not leave corpses. What corpses are left eventually disintegrate. Whether an organism leaves a corpse or not, and whether its corpse exists or not, if that organism dies at time t and does not regain life then it is dead after t .

The difficulty can be avoided if we say, with Jay Rosenberg 1983, p. 42), that dead is a relation between an organism, the time it died, and a subsequent time, and that when someone asserts, at some given time t , ‘Socrates is dead,’ what is asserted (ignoring the possibility of restored life, discussed in the next section) is roughly that Socrates died before t .

As is mentioned below, some theorists deny that an object that is at one time an organism may continue its existence as a corpse. Such theorists will say that organisms and their corpses are two different objects. They may conclude that ‘dead’ is ambiguous—that it means one thing as applied to organisms, and another thing as attributed to the corpses organisms leave. In any case, they will need to deny that, as concerns corpses, being dead implies having died, as corpses are never alive, according to them. If, on the other hand, an object that is an organism may continue its existence as a corpse, then, at any time t after that object dies, ‘dead’ applies univocally to it at time t , and means roughly died before t .